Abstract

The Qianlong edition of the Tao Ye Tu (Ceramic Production Illustrations) serves as an essential visual resource for understanding the porcelain production of the Qing dynasty. This study positions this album within the broader contexts of woodblock prints, imperial court paintings, and export albums to affirm the Qianlong court version as the most reliable foundation for spatial analysis. By examining the album as both a technical document and a cultural artifact, this paper links its visual rhetoric to broader debates in the fields of visual culture studies and global production network theory. Building on this framework, our analysis deciphers the interaction mechanisms between ceramic production and the spatial environment in Jingdezhen, examining how these relationships were shaped by the specific socio-economic conditions of the Qianlong reign, including imperial patronage systems, technological exchanges facilitated through cross-cultural contact, and the expanding global trade networks that characterized the period. Through meticulous image analysis, the production scenes are categorized into three spatial types: rural, courtyard, and ritual. This classification reveals an advanced integration of ecological adaptation, process aggregation, economic efficiency, and human-centric design. The analysis also accentuates the artists’ employment of spatiotemporal integration and separation, the balance between realism and idealization, and the dynamics between physical and metaphorical space. This study not only deepens our understanding of the spatial organization of ceramic production during the Qing dynasty but also articulates how visual materials were employed to construct an idealized representation of the industry, one that reflected the prevailing social structure and distinct aesthetic principles of the time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historical images, as records of social, economic, cultural, and human habitats during distinct historical periods, provide crucial evidence for the reconstruction of historical truths. Some concepts, especially in ancient texts, are difficult to convey clearly through words alone. Thus, images are often used as supplements to more intuitively express an author’s intent. Georgius Agricola’s De Re Metallica offers a detailed description of European mining and metallurgical techniques in the 16th century, and it is accompanied by numerous illustrations that depict the tools and processes of the time. Jacob Leupold’s Theatrum Machinarum describes various mechanical devices and their applications, particularly power transmission systems, with detailed illustrations that display the mechanical inventions and technologies of the era. China’s earliest technical literature on handicrafts, the Kaogongji (Record of Examination of Crafts, 考工记) from the Spring and Autumn periods (770–476 BC), also includes illustrations of various tools. The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) scientist Song Yingxing (宋应星) also enriched his work, Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature, 天工开物), with abundant illustrations that vividly demonstrate the handicraft technologies of the Ming dynasty, covering areas such as textile production, ceramic manufacturing, and metal processing. Another type of document has emerged, and it uses multiple images to continuously depict the development of a story or event as complemented by corresponding text to disseminate knowledge. Notable examples of this type of document include the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)’s Geng Zhi Tu (Pictures of Tilling and Weaving, 耕织图), the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368)’s Ao Bo Tu (Pictures of Boiling Waves, 熬波图) depicting salt production, the early Qing dynasty (1271–1368)’s Qiong Li Feng Su Tu (Pictures of the Customs of the Li People in Hainan, 琼黎风俗图) introducing the life of the Li people (黎族) in Hainan, among others.

These images can help us interpret or verify the records sourced in literary classics and contracts and provide greater possibilities for field investigations, specialized studies, and comprehensive interdisciplinary research (Chen, 2013). Scholars have extensively researched these image-based historical materials. Francisco Javier Trujillo analysed the illustrations in Georgius Agricola’s important work, De Re Metallica, with a focus on the ergonomic analysis of the mine pumps depicted in images, to reveal the early ergonomic principles embodied in visual materials (Javier Trujillo et al., 2021). W.G. Lockett explored Jacob Leupold’s analysis of overshot waterwheels in Theatrum Machinarum, examining Leupold’s methods of analyzing these waterwheels (Lockett, 2001). Wang Yipeng analysed Geng Zhi Tu (Pictures of Tilling and Weaving) produced during the Kangxi period (1661–1722), deducing and summarizing the landscape language structure types that had been shaped by agricultural production in the Jiangnan region (Wang, 2024). These studies show that image-based historical materials not only serve as essential tools for understanding history but also provide unique perspectives and methods for modern urban planning, cultural heritage preservation, and interdisciplinary research.

The Qianlong-era (1735–1796) Tao Ye Tu (Ceramic Production Illustrations, 陶冶图) is a quintessential example of historical visual material. This study not only documents the technical aspects of ceramic craftsmanship but also provides crucial insights into the spatial environment of ceramic production in historical Jingdezhen. This edition, particularly the text written by Tang Ying (Superintendent of Ceramics during the Qianlong Era, 唐英), which was known as the Commentary on Tao Ye Tu, has been examined by many scholars. This work is recognized for its significant contributions to the fields of technology, folklore, art, and philosophy (Chen and Zhang, 2014; Wu, 2020). While researchers have acknowledged the historical value of visual elements in the Qianlong edition of the Tao Ye Tu (Zong, 2018), there have been few analyzes conducted on the images themselves.

Thus, building on existing research, this paper aims to deepen the study of images in the Qianlong-era Tao Ye Tu by applying of image analysis methods. It will employ image analysis as its primary method, supported by historical documentation and field surveys, to interpret the production scenes and spatial environments depicted in the illustrations. The research seeks to explore the dynamic interactions between Jingdezhen’s ceramic production and its spatial setting, aiming to reveal the underlying logic governing these relationships—including principles of environmental adaptation, resource utilization, and customary practices. Through this approach, the study intends to provide new perspectives for understanding the historical development of Jingdezhen’s ceramic industry.

Overview of the Tao Ye Tu

Categories of ceramic production illustrations

Depictions of ceramic production processes can be broadly categorized into three types, each with distinct purposes and characteristics that determine their value for spatial and technical analysis.

The first category consists of woodblock print illustrations in scientific and technical (classics), which serve as auxiliary interpretations of the text. Limited by the production characteristics of woodblock printing, these images are simple, and practical, and they accurately depict porcelain-making processes and tools. For instance, the Taoyan (陶埏) volume of Song Yingxing’s Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature) from the late Ming Dynasty contains 13 illustrations. These illustrations were drawn on the basis of the author’s field investigations and onsite observations in Jingdezhen. For example, the bottom structure of the “potter’s wheel” is clearly depicted in Fig. 1. Similarly, the Jingdezhen Taolu (Records of Jingdezhen Ceramics, 景德镇陶录), which was compiled by Lan Pu (蓝浦), supplemented by Zheng Tinggui (郑廷桂), and published in the 20th year of the Jiaqing era (1815), includes Tushuo (Illustrated Descriptions, 图说) in volume one. These also faithfully depict the imperial kiln complex and ceramic production processes in use during the Qianlong-Jiaqing periods (1735–1820). There are sixteen illustrations, with each spanning two pages to form a horizontal scroll (Fig. 2). While these woodblock prints were intended for the general public and provide accurate renderings of tools and workflows, their schematic and simplified nature limits their utility for in-depth spatial analysis.

The second category consists of export painting albums for ceramic production. One set can have as few as ten or as many as fifty leaves. Each album is typically divided into two parts: the upper part illustrates the production process—such as the mining and processing of raw ceramic materials, body forming, painting blue-and-white painting, glazing, kiln firing, overglaze enameling, bundling with straw and packing into barrels, and the worship of deities (Lin, 2023). The lower part depicts scenes outside of Jingdezhen, such as those of placing orders, hosting banquets, engaging in price negotiations, urging delivery, land and water transportation, and warehouses in Guangzhou, checking and receiving of goods, adding of family rose decorations, boxing, and sales. This category functioned like postcard souvenirs, and examples were exported overseas to satisfy Western curiosity about China and to play a positive role in the Sino-Western ceramic industrial and technological exchange. Their painting style is a fusion of Chinese and Western techniques, but they do possess a shortcoming in the fabrication of certain processes and kiln tools. For example, in the album held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Fig. 3), the buildings depicted for ceramic production exhibit the architectural style of the Lingnan region rather than that of the Jingdezhen area. The kilns also differ from the typical “egg-shaped kiln” of Jingdezhen, which “resembles a half egg lying on the ground, high and wide at the front, gradually contracting towards the kiln tail, which has an independent chimney whose height is equal to the length of the kiln.” Such geographic and technical discrepancies make these albums unreliable as sources for precise spatial reconstruction.

The annotated details highlight the incongruous Lingnan-style architecture and the misrepresented “egg-shaped” kiln, underscoring the album’s nature as a commercial visual product rather than a faithful technical document. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on an original source reproduced in Lin YQ. Research on Qing Dynasty Porcelain Manufacturing Illustrations. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2023;51(4):139–157.

The third category consists of yuanhua (imperial court paintings, 院画), which refer to works created by painters affiliated with the imperial painting academy—an institution that flourished in China especially from the Song dynasty onward. During the Qing dynasty, under the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors, court painting reached a peak, characterized by a lavish and refined style. Influenced by European painting techniques introduced by Jesuit missionaries, it emphasized realism, spatial perspective, and chiaroscuro to depict material texture and three-dimensional space. In this tradition, several versions of the Tao Ye Tu were commissioned by the Qing court to systematically record and promote porcelain production.

The main versions attributed to the Qing court, arranged chronologically, include: the Overseas version (Kangxi-Yongzheng period, 1661–1735); the Beijing Palace Museum version (Yongzheng period, 1723–1735); the Chonghua Palace version (Qianlong period, dated 1743); and the Taipei Palace Museum version (post-Jiaqing era, after 1796) (Fig. 4).

The four primary Qing court versions are arranged along a timeline. For each version, a representative scene is displayed alongside key metadata. Sources (L to R): Redrawn by the authors based on sources reproduced in: Li ZW. Examination of the Court Painting Edition of the ‘Tao Ye Tu’. Cultural Relics World. 2024(1):18–24; and Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

These imperial editions are defined not only by their magnificent composition and superior brushwork but also by their accurate depiction of production processes and tools, offering a reliable visual basis for the study of ceramic technology and workshop space.

When assessed for the purpose of spatial and technical analysis, the potential inaccuracies in export albums and the visual simplifications in woodblock prints render them less suitable for detailed study. In contrast, the imperial court versions of the Tao Ye Tu combine esthetic refinement with documentary precision, making them the most reliable and informative visual sources for analyzing the spatial organization and technical details of ceramic production.

Analysis of the Tao Ye Tu versions

As outlined above, four major imperial versions of the Tao Ye Tu have been identified, spanning the Kangxi, Yongzheng, Qianlong and Jiaqing reigns. Among these, the Chonghua Palace version from the Qianlong period has been selected for detailed analysis in this study.

This particular scroll, which is a colored silk manuscript divided into twenty sections, measures 29 cm in length and 25 cm in width. It first appeared at Christie’s Hong Kong Spring Auction in 1996 as item number 0065 in the “Imperial Chinese Art” auction. A member of the Qingwan Club in Taipei purchased it and has served as its custodian ever since (Huang, 2022). The scholars Li Ziwei from the Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum and Lin Yiqiang from the Chinese University of Hong Kong have conducted detailed comparisons of these versions. They concluded that the Chonghua Palace version was officially designated during the Qianlong period, with accompanying text authored by Tang Ying, the imperial kiln supervisor (Lin, 2023; Li, 2024).

The four selected versions are not fully identical in their depicted scenes. To facilitate a clearer comparison of painting techniques, the scenes of “Repairing Moulds for Round Wares” (圆器修模) and “Throwing Round Wares on Wheel” (圆器拉坯) are used for analysis. As shown in Fig. 4, all four depictions share similarities in portraying the spatial arrangement for round ware production: ceramic artisans working inside buildings dedicated to throwing or mould repair, with courtyards outside containing drying racks, greenware bodies, and clay storage tubs. Among them, the two versions predating the Qianlong period are considered by some experts as potential prototypes for the Qianlong edition (Zong, 2018). The very creation and refinement of these multiple versions across the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong reigns were deeply embedded in a period of exceptional economic prosperity and state support for the arts, often termed the “High Qing” era. This flourishing provided the necessary resources—imperial patronage, a stable of highly skilled court painters, and a mature, technically advanced ceramic industry at its zenith—which together created the ideal conditions for producing such detailed and authoritative visual records. In terms of artistic execution, while these earlier versions exhibit fine brushwork and influence from Western techniques in the depiction of landscapes and objects, the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version demonstrates even greater refinement, a testament to the peak of artistic and technical achievement under these optimal conditions. Its composition is more cohesive, and the figures are rendered with superior detail, particularly in the precise and clear depiction of ceramic tools.

Following the Qianlong era, Qing court painting gradually declined. The version housed in the Taipei National Palace Museum, produced after the Jiaqing period, is of lower artistic quality, featuring loose composition and crude figures, though the representations of processes and tools remain relatively accurate.

In summary, when compared to the woodblock-printed book illustrations and the export painting albums, the imperial court versions (yuanhua) of the Tao Ye Tu provide a more accurate record of Jingdezhen’s ceramic production techniques. Among these court versions, the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace edition stands out for its exceptional detail and clarity, making it the most suitable version for scholarly research into the spatial and technical aspects of porcelain production.

The creative process of the Tao Ye Tu

The creation of the Qianlong-era Tao Ye Tu was a meticulous and multi-stage undertaking, which firmly establishes the exceptional documentary value of the Chonghua Palace version. This edition is distinguished from others not only by its detailed documentation in court archives but also by the direct involvement of Tang Ying (唐英), the renowned Superintendent of the Imperial Kiln. His authoritative, first-hand commentary provides crucial textual explanation for the techniques depicted in the illustrations.

The process was initiated in the third year of Qianlong’s reign (1738), when Emperor Gaozong (高宗) commissioned the Ruyi Pavilion—a specialized painting academy founded in 1736 under the Imperial Household Department—to produce a new set of twenty paintings based on existing Tao Ye Tu prototypes. The initial division of artistic labor was specified as follows: Tang Dai (唐岱) was assigned to paint trees and rocks, Sun Hu (孙祜) was responsible for architectural drawings, and Ding Guanpeng (丁观鹏) was tasked with rendering the figures.

Records from the Qing Dynasty’s Inner Court Workshop Archives indicate that on April 8, 1743, the supervising eunuchs reported the delivery of the twenty paintings. A subsequent imperial decree entrusted these works to Tang Ying, instructing him to compose detailed descriptions of the techniques illustrated in each scene. These descriptions were to include the specific sources of clay, raw materials, and process water. Furthermore, he was explicitly tasked with arranging the twenty paintings into the correct technical sequence of porcelain manufacturing, thereby establishing the definitive process flow. This direct commission resulted in the celebrated Commentary on the Tao Ye Tu (《陶冶图说》), which serves as an unparalleled textual counterpart to the visual narrative.

The final collaborative framework of the project is corroborated by the National Academy Painting Record (1816), which identifies Sun Hu, Zhou Kun (周鲲), and Ding Guanpeng as the painters of the definitive twenty-scene album. The inscription on the final page, “Respectfully painted by Ministers Sun Hu, Zhou Kun, and Ding Guanpeng,” accompanied by text attributed to Dai Lin (戴临) and the preface “Respectfully compiled by Minister Tang Ying,” corresponds precisely with the composition of the Chonghua Palace version. This correspondence, confirmed by the presence of imperial collection seals, solidly authenticates it as the official record (Lin, 2023).

Over its 6-year creation period, the painting team evolved, ultimately culminating in the collaborative work of the three named ministers. Their combined expertise enabled the accurate depiction of landscapes, architecture, figures, and tools. The preeminent status of the Chonghua Palace version is founded upon a tripartite foundation: the superb artistry of the court painters, the clear imperial endorsement and curation process, and, most significantly, the authoritative technical commentary and sequencing provided by the era’s most famous kiln supervisor. This unique synergy between image and text creates a mutually verifying chain of evidence, establishing this version as the most reliable source for any subsequent spatial and technical analysis of Qing ceramic production.

Spatial classifications in the Tao Ye Tu

The Qianlong Era’s Tao Ye Tu (hereafter referred to as Tao Ye Tu), which was commissioned by Emperor Qianlong and annotated by Tang Ying, vividly depicts the twenty main procedures used for porcelain-making in Jingdezhen through twenty illustrations. The spaces supporting the porcelain-making process are divided into rural spaces, courtyard spaces, and ritual spaces according to their physical characteristics and functional use (Fig. 5). Rural spaces reflect the provision of raw materials and power by the natural environment, courtyard spaces show the practical operations and organizational processes of porcelain-making, and ritual spaces highlight the cultural and religious significance of porcelain-making activities. The scenes entitled “Mining Stone and Preparing Clay (采石制泥)”, “Ash Preparation and Glaze Mixing (炼灰配釉)” and “Collecting Cobalt Blue Pigment (采取青料)” belong to the rural space, providing raw materials for subsequent processes. The process depicted in the image “Washing and Refining Clay (淘练泥土)” involves processing clay on the basis of quarrying and making clay; subsequently, round wares were shaped through “Repairing Moulds for Round Wares (圆器修模)” and “Throwing Round Wares on Wheel (圆器拉坯)”, whereas sculpted wares were shaped through “Building Sculpted Wares by Hand (琢器造坯)”. After shaping, roundware bodies underwent “Decorating Round Wares with Blue-and-White (圆器青花)”, whereas sculpted bodies underwent “Decorating and Painting Sculpted Wares (制画琢器)”. The pigments used in these two processes were selected through “Selecting Cobalt Blue Pigment (拣选青料)” and ground from blue material in the “Moulding the Paste and Grinding the Colors (印坯乳料)” process. Round and sculpted bodies were either glazed directly or painted before glazing to form underglaze colors. They were glazed through “Dipping and Spraying Glaze (蘸釉吹釉)”. The glazes were made in the process depicted in “Refining Ash and Preparing Glaze (炼灰配釉)”. After glazing, round and sculpted bodies underwent “Trimming and Carving Foot (旋坯挖足)” before entering the prefiring stage. Kiln shelves (saggars) were prepared beforehand through “Making Saggars (制造匣钵)” for loading “Loading Greenware into Kiln (成坯入窑)”. After “Firing and Unloading Kiln (烧坯开窑)”, the wares were finished round and sculpted porcelain. If further decoration was desired, these wares underwent “Decorating Round and Sculpted Wares with Overglaze Enamels (圆琢洋彩)” and then low-temperature firing in the process depicted in “Performing Bright and Reduction Firing (明炉暗炉)”. Finally, the finished porcelain was protected by “Bundling with Straw and Packing into Barrels (束草装桶)” for shipment worldwide. Finally, people expressed gratitude to the deities through “Offering Sacrifices and Fulfilling Vows to Gods (祀神酬愿)” to protect the complex and variable porcelain-making process, ensuring its safety and smooth completion.

A schematic mapping the twenty procedures onto three spatial types (rural, courtyard, ritual), illustrating their functional sequence and interdependence. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

Rural spaces

There are three process diagrams depicting rural spaces: “Mining Stone and Preparing Clay”, “Refining Ash and Preparing Glaze” and “Collecting Cobalt Blue Pigment”. Mountains form the skeleton, water forms the veins, and settlements dot the landscape (Fig. 6). This space reflects the utilization and transformation of natural resources in the porcelain-making process and highlights the wisdom of traditional porcelain-making techniques being kept in harmony with the environment.

Extraction and analysis of rural production scenes from the Tao Ye Tu, showing the relationship between mining, raw material processing, and the natural environment. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

Mountains

Mountains are integral planar elements in rural landscapes, and serve the backbone and backdrop of the region. The illustrations depict undulating mid-to-low mountains with V-shaped valleys and small basins between them. Mining scenes represented on mountain tops and in valleys accurately capture the topography of Jingdezhen and its surroundings. This area lies within the residual ranges of Mount Huangshan(黄山) and the Huaiyu Mountains (怀玉山), formed from an older and geologically unstable hilly region. Over time, extensive geological changes have enriched this area with mineral deposits (Committee, 2020). Tang Ying described the three types of minerals used in ceramic production:

White stone came from Pingli(坪里) and Gukou(谷口) in Qimen County(祁门县), Anhui Province, which was located ~200 miles from the kiln site.

Porcelain stone was sourced from Gaoling(高岭), Yuhong(玉红), and Jian Tan(箭滩).

Bluish-white stone came from Le Ping County(乐平县), which was ~140 miles south of Jingdezhen.

These minerals are critical raw materials for ceramics, serving as the muscles, bones, and skin of the craft. The mining scenes illustrate open-pit methods, which indicates the abundance of mineral resources during this period. In contrast, the blue material procurement scenes depict mountain ranges in Zhejiang’s Shaoxing(绍兴) and Jinhua (金华) regions, which differ significantly from the mountain trends shown in the quarrying, clay-making, ash-refining, and glaze-preparation illustrations.

Water

Water is a linear spatial element in rural landscapes and is critical not only for depicting natural beauty but also for powering and transporting materials in ceramic production. Streams depicted in the processes of quarrying, making clay, refining ash, and preparing glaze originate from densely forested mountains, and wind their way through valleys in accordance with the terrain. Sections with rapids feature water-powered mills used to crush magnetic stones. According to Porcelain Narration, there are three types of water mills (Zhu, 2022):

Large wheel mills built beside major rivers and tributaries.

Medium-sized lower dragon mills located along large ditches.

Small drum mills located by small streams.

The largest wheel mill in the illustration is ~5 m high and provides a powerful crushing force. This estimation is derived from a proportional analysis based on architectural elements depicted in the same scene: the wheel mill’s height closely aligns with that of the workshop buildings that are depicted alongside it. Historical evidence and field studies indicate that such traditional porcelain workshops, which were measured from the ground to the ridge of their gabled roofs, typically stood ~5 m tall. Water not only powered the production process but also served as a vital transport route for porcelain materials. Jingdezhen possesses a complex and complete river network that is formed from the Chang River (昌江) and its tributaries. These rivers have preserved traces of ancient porcelain industries along their banks, thereby exhibiting valuable linear cultural heritage. Historically, when water transport served as the dominant mode of conveyance, Jingdezhen’s porcelain exports relied heavily on the Chang River.

Departing from the Chang River, the external transporting of Jingdezhen ceramics was primarily divided into an official northern route, which was used to supply the imperial court, and a southern network, which was aimed at global trade (Li, 2018)(Fig. 7). The northern route was primarily responsible for the tributary mission of wares from the Imperial Kilns (御窑厂). Ceramics were shipped via the Chang River into Poyang Lake(鄱阳湖), entered the Yangtze River (长江), and then proceeded northwards via the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal (京杭大运河), ultimately reaching imperial consumption centers such as Beijing and Tianjin.

The southern routes, which were central to foreign trade, branched into three main pathways: The first led from Jingdezhen along the Chang River to Poyang Lake, up the Xin River (信江), and then overland across the Wuyi Mountains (武夷山) into the Min River (闽江) Basin, finally arriving at Fuzhou (福州) for the export of wares. The second also went travelled the Chang River and Poyang Lake into the Xin River, reached Hekou town (河口镇) in Yanshan County (铅山县), and then proceeded overland through Quzhou (衢州) and Jinhua (金华), before connecting to the Fuchun River (富春江) to access the port of Ningbo (宁波). The third route followed the Chang River and Poyang Lake into the Gan River (赣江), proceeded southwards, crossed the Meiling Pass (梅关) to enter the North River (北江) system, and ultimately reached the port of Guangzhou (广州) (Peng, 2011).

This water-based transport system effectively supported both the domestic supply and international exporting of Jingdezhen ceramics. The southern routes, in particular, served as crucial corridors that connected to global trade networks, ultimately facilitating the international dissemination of ceramic culture and the exchange of Chinese porcelain manufacturing techniques.

Settlements

Settlements are point-like spatial elements in rural landscapes that serve as hubs for human activity and play crucial roles in ceramic production processes. The illustrations depict the overall spatial image and details of settlements. From a distance, these settlements were distributed in relatively open basins among mountains and were built facing water and backed by hills, and they had volumes. Miners extract white stones from mountaintops and transport them down valleys to small settlements for transshipment and storage.

In close-up views, the processing of porcelain stone, the washing of porcelain soil, the making of white clay, the preparing of ash, and the mixing of glazes, as well as the “Chuandou Structure(穿斗)” (a traditional Chinese wooden architectural structure in which columns directly supported the roof truss, and the purlins were connected by tie beams) framing pounding sheds, spreading sheds, and processing equipment, can be seen in detail. The scene also shows farmers working with hoes and interacting with tea vendors on a bridge over a stream after finishing their work, which highlights the multifunctional role of settlements in meeting production needs while still maintaining daily life and economic exchanges.

Courtyard spaces

In addition to rural and ceremonial spaces, courtyard spaces were mainly used for core porcelain-making processes, which including 16 steps.

Early porcelain production in Jingdezhen was dispersed across “Si Xiang Ba Wu (四乡八坞) ” (which was a model of dispersed porcelain production in the rural areas of early Jingdezhen, where “Si Xiang” refers to four village regions and “Ba Wu” refers to eight valleys or settlements), which were primarily family-based in settlements near waterways (Xiao and Chen, 2018). Through the successive establishment of the Fuliang Porcelain Bureau (浮梁磁局) in the Yuan Dynasty, the Imperial Ware Factory (御器厂) in the Ming Dynasty, and the Imperial Kiln Factory (御窑厂) in the Qing Dynasty, Jingdezhen gradually evolved into an urbanized center of porcelain production that was focused around imperial kilns (Zhu and Zhu, 2020).

Three historical images reveal the urban landscape of Jingdezhen and the Imperial Kiln Factory during this period. As synthesized in Fig. 8, these include: the “Map of Jingdezhen” (景德镇图) from the 1682 (Kangxi 21) edition of the Fuliang County Gazetteer (浮梁县志); the “Illustration of the Imperial Kiln Factory” (御窑厂图) from the 1815 (Jiaqing 20) edition of the Jingdezhen Tao Lu (景德镇陶录); and the “Blue-and-White Porcelain Tabletop Depicting the Imperial Kiln Factory” (青花御窑场图圆桌面) housed in the Capital Museum. Together, these three sources progressively illustrate the location, layout, and architectural details of the Imperial Kiln Factory in Jingdezhen.

This composite figure synthesizes three key historical sources to progressively illustrate the Imperial Kiln Factory’s urban context, formal layout, and internal activity: a The ‘Map of Jingdezhen’ (1682) locates the Imperial Kiln Factory (highlighted in red) in the urban center, aligned with the Chang River; b Architectural Plan: The ‘Illustration of the Imperial Kiln Factory’ (1815) details its south-facing, axially symmetrical layout with a central paved pathway; c Panoramic Detail: The “Blue-and-White Porcelain Tabletop” depicts the compound from above, with the inner courtyard(outlined in red) inside the ceremonial gate flanked by east and west subsidiary courtyards that housed the bustling porcelain production workshops. Sources: a Fuliang County Gazetteer (1682), public domain; b Jingdezhen Tao Lu (1815), public domain; c Reprinted from Xing P. Discussion on the Qing Dynasty Blue and White Imperial Kiln Factory Diagrams on Round Porcelain Plates. Museum. 2018(6):53–59.

The Imperial Kiln Factory was situated in the center of Jingdezhen, oriented southwards, with nearly parallel alignment with the Chang River (昌江). The structures within were south-facing and symmetrically arranged along a central north‒south axis. A paved pathway (甬道) ran along the central axis, and the buildings on both sides opened towards it. Inside the ceremonial gate (仪门) lay an inner courtyard. Subsidiary courtyards were positioned to the east and west, and they housed various porcelain production workshops—including those for body turning, painting, glazing, and firing—presenting a scene of bustling activity (Xing, 2018).

Furthermore, archaeological excavations conducted at the Imperial Kiln Factory site in 2014 by the Jingdezhen Institute of Ceramic Archaeology and the School of Archaeology and Museology of Peking University, among other institutions, provided material evidence that strongly supports the depictions in these historical images. The excavations uncovered remains of workshops for low-temperature colored glaze decoration, overglaze painting, and vessel throwing and shaping, as well as kilns for firing, and the Shizhu Temple (师主庙) for ritual offerings (Zhong et al., 2020).

The spatial organization revealed by this historical and archaeological evidence—functional subsidiary courtyards, and specific workshop allocations—directly corresponds to and validates the courtyard spaces depicted in the Tao Ye Tu. This correlation confirms that the album’s illustrations are grounded in the physical reality of the Qing Imperial Kiln Factory, providing a reliable basis for further spatial analysis.

Courtyard spaces consisted of building spaces and courtyard spaces. The former included various functional workrooms, and the latter provided ventilation, lighting, and process connectivity.

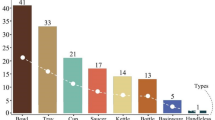

Courtyard spaces can be categorized into forming workshops, decorating workshops, and firing workshops (Fig. 9). The forming workshops were used for making and refining porcelain bodies, the decorating workshops for glazing and decoration, and the firing workshops for firing ceramics. This functional division reflects the different stages and specialized operations involved in the porcelain-making process and provides a rational spatial layout for efficient production.

Analytical diagrams derived from the Tao Ye Tu categorizing workshops into forming, decorating, and firing spaces. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

The forming workshop

Forming workshops, which were named after unfired porcelain bodies, were workshops for porcelain production. The eight scenes in the Tao Ye Tu—“Washing and Refining Clay”, “Manufacturing Saggars”, “Repairing Moulds for Round Wares”, “Throwing Round Wares on Wheel”, “Building Sculpted Wares by Hand”, “Moulding the Paste and Grinding the Colors”, “Dipping and Spraying Glaze”, “Trimming and Carving Foot”—depict similar courtyard spaces that housed forming workshops. The forming workshops use a “Chuandou Structure”. The foundation is constructed with stone masonry and positioned one step higher than the courtyard to prevent dampness. The main body of the building was composed of wooden structures, which retained their natural curves and rough textures to enhance its rustic and simple style. The roof had a gable design covered with blue‒grey tiles and a reasonable slope for rapid drainage. The ridge height was ~4 m, the depth was ~3–5 m, and the width was ~3 m. Most buildings had no walls on three sides, with only wooden boards enclosing the rear, thereby creating an open layout. This design ensured good ventilation and lighting and was suitable for porcelain-making processes. The construction principles of clay workshops for producing carved and round vessels are similar, with only minor dimensional differences. Brick walls were used for historical clay workshops in the Jingdezhen Ancient Kiln Folklore Expo area to increase durability and fire resistance (Fig. 10). Local timber resources such as fir and miscellaneous wood for framing were used in the design, revealing an adaptation to local conditions. The single-process workshops depicted in the illustration were mostly two bays wide. The current large workshops in Jingdezhen generally have 12, 10, 8, or 6 bays (Yao and Cai, 2015). Forming workshop construction emphasizes handicraft production functions, and it deviates from the traditional odd-numbered bay format of residential buildings.

The composite figure demonstrates the key characteristics described in the text: (from left to right) the courtyard setting and elevated stone foundation for damp prevention; the open-sided Chuandou Structure with a gable roof for rapid drainage; the well-ventilated and lit interior workspace for handicraft production. Source: All photographs were taken by the authors at the Jingdezhen Ancient Kiln Folklore Expo Area.

The internal space of the building exhibited functional differentiation through the arrangement of production equipment and tools specific to each process. For example, in the shaping, trimming, and foot-cutting of round vessels, the interior space primarily housed the potter’s wheels. The diameter of these wheels varied according to the size of the pieces being produced, typically ranging from 120 to 160 cm. The wheel pit was circular and well-like, with a trapezoidal frame installed above it on which craftsmen sat to operate (Zhu, 2022). As the potter’s wheel was a fixed installation, the interior layout incorporated areas for the operators’ movement as well as for the storage and transportation of pieces. Vertical space within the building was fully utilized by positioning connecting beams at varying heights between columns to form drying racks for the clay pieces (Yao and Cai, 2015). These racks, predominantly constructed from fir wood, measured ~2.7 m in length, 9 cm in width, and 1.8 cm in thickness (Zhan, 2014). They were arranged with a slight incline to facilitate insertion and removal by workers during operations, thereby supporting the large-scale turnover and transfer of pieces between processes.

The courtyard space of the forming workshop was enclosed by buildings and walls, forming an irregular enclosed area. The walls, which stood ~2.4 m high, ensured privacy and helped protect proprietary techniques during production. Common equipment and tools within the courtyard included mud-washing buckets, mud-storage vats, drying racks, glaze tanks, and saggars, indicating that its primary functions were drying, storage, transportation, and serving as a transitional zone between various processes. This arrangement underscored the courtyard’s multifunctional role and efficiency as a shared operational area. The buildings opened onto the courtyard, with level ground and unobstructed overhead space ensuring ample sunlight and effective air circulation for the drying racks. This layout streamlined the handling of materials and reduced the risk of damage to kiln pieces. Additionally, water wells were commonly present, being particularly essential for clay-washing and glazing procedures—a feature that further emphasized their integral role in production. The excavation of water wells in historical workshops across different periods confirms that these were not merely decorative but fundamental to the production process.

The decorating workshop

The decorating workshops were primarily used for glazing and decoration processes. Unlike forming workshops, decorating workshops need excellent lighting and ventilation conditions to meet complex decoration requirements. The decorating workshop depicted in the painting of carved porcelain and round carved foreign colors had a “Chuandou structure”. The wooden columns were finely processed, and the wall enclosure was made of brick and stone and painted with white lime. This not only improved the building’s rain and moisture resistance but also enhanced its indoor brightness, thereby improving the working environment. Unlike forming workshops, which emphasize open space and smooth process connections, decorating workshops highlighted stability and esthetics through the use of brick and stone walls and decorative details.

The interior space design of a decorating workshop combined flexibility with functionality. It featured movable furniture such as tables, chairs, and racks to accommodate various processes. For example, in the round sculpting with foreign colors process, a large workbench measuring ~2 m wide and 3 m long was used for applying glazes and colors to large ceramics, enabling workers to efficiently collaborate around the table and maximizing the indoor space by providing only necessary walkways. This layout enhanced space utilization and facilitated collaboration among craftsmen. The indoor and outdoor garden spaces interpenetrated one another, demonstrating the integration of traditional Chinese architecture with the natural environment. A large, latticed window on the inner wall, enhanced with wooden boards and benches below, created a restful area for artisans. Bamboo groves outside the window introduced natural landscapes into the room through framed views, fostering a serene working atmosphere.

The courtyard of decorating workshop depicted the unique atmosphere and cultural significance of different stages in Jingdezhen’s ceramic production through detailed and rich courtyard spaces (Fig. 11). In the painting of “Decorating Round Wares with Blue and White”, the courtyard presented an ornamental space distinct from the earlier processing and production courtyards. Enclosed by high walls and buildings, the courtyard formed an irregular polygon with distinct garden scenery. Climbing plants, such as roses, covered trellises, creating a vibrant floral hedge wall. This design not only beautified the environment but also provided a tranquil and poetic workspace for the painters, inspiring them to capture the beauty of nature in their blue-and-white porcelain work. The courtyard in “Decorating and Painting Sculpted Wares” featured rockeries and bamboo, enriching the spatial hierarchy and showcasing the craftsmen’s appreciation for traditional culture and natural beauty. Rockeries, an essential element of classical Chinese gardens, symbolized the grandeur of Mount Huashan(华山), while bamboo was admired for its elegant character in literature. The courtyard in “Decorating Round and Sculpted Wares with Overglaze Enamels” was even more exquisite and artistically charming, with carefully pruned bonsai placed on long stone slabs, embodying the esthetics preferred by Chinese literati painters. The overglaze enameling technique depicted here, known in China as yangcai (foreign colors, 洋彩), itself represents a profound technological exchange. Its development was significantly influenced by knowledge of European enamel pigments and techniques, introduced to the Qing court through channels such as Jesuit missionaries. A central pond, accompanied by rockeries and graceful trees, creates a miniature garden landscape. This setting not only offered visual respite for artisans engaged in detailed painting and dyeing but also fostered creativity through an elegant ambiance, fulfilling their esthetic needs. Artisans working in these ornamental courtyards clearly possess high levels of cultural literacy and artistic appreciation, resonating with Tang Ying’s emphasis on elegance in imitation and innovation rooted in tradition, reflecting strict procedural requirements and craftsmanship, as well as craftsmen’s cultural literacy.

Analytical diagram of a decorating workshop scene, showing the integration of work space with natural and ornamental elements like bamboo and rockeries. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

The firing workshop

The firing workshop depicted in the Tao Ye Tu is elongated and oval, like an inverted pot, and measures ~10 feet in height and width, with double the depth, to facilitate uniform heat distribution and improve firing efficiency. It is covered by a large, tiled roof called a kiln shed, which protects the kiln from weather and helps control the internal temperature. Although Tang Ying’s commentary is focused primarily on ceramic-making techniques, his detailed description of the kiln house underscores its critical role in the firing process.

The design and layout of this key venue directly impacted the firing results and quality. Jingdezhen kilns evolved from rudimentary to advanced states over many years, transforming from earthen dome kilns in the Dynasties (907–960) to dragon kilns in the Song and Yuan dynasties (960–1368), then to horseshoe and gourd kilns in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), and finally to egg-shaped kilns in the Qing dynasty (1368–1644). Each transformation of the kiln structure promoted advancements in ceramic firing techniques. A comparison of with the kiln houses illustrated in the Tao Ye Tu and the National Key Cultural Relics Protection Unit Ancient Kiln displayed in the Jingdezhen Ceramic Folk Culture Expo Area reveals that the latter has a larger wooden framework covering nearly 1000 m2. The kiln house evolved from partial to full coverage, with a thin ~21-m high chimney at the rear, which occupies approximately one-fourth of the kiln house area, and an additional floor was added for storing pine wood (Yao and Cai, 2015) (Fig. 12).

Ritual space

Ritual spaces were primarily used for rituals and ceremonies related to porcelain, which reflects the cultural and religious background of the craft. Depicting a ceremony that was typically held in dedicated ceremonial or public spaces, the “Offering Sacrifices and Fulfilling Vows to Gods” scene shows a building situated on a platform of ~1 m high, surrounded by railings that form a walkway around it. The structure, which was built with brick and wood, has a classical hip-and-gable roof and exuded solemnity and grandeur. The interior likely featured a raised beam framework, providing both durability and room for rich decorations. The exterior was painted with vibrant colors and auspicious symbols, symbolizing reverence and prayers to the deities. With three bays wide, the building appears dignified and spacious, revealing statues and altars through the columns. The surrounding courtyard offered ample space for gatherings. A central open area allowed for temporary stage setups for performance.

During important festivals, townspeople watched performances that were presented on these stages, which were typically constructed from wood and adorned with silk and paper lanterns to create a festive atmosphere.

As the national center for the ceramics industry during the Ming and Qing dynasties, Jingdezhen had a diverse pantheon of deities who were worshipped in the ceramics sector, Master Zhao Kai (赵慨), the Wind-Fire Immortal Tong Bin (童宾), the Five Kings Hua Guang (华光), the Heavenly Consort Lin Mo (林默), Marshal Qian Da (钱大), and the Gaoling Kaolin Clay God (高岭瓷土神), among others (Xiao and Chen, 2018). These deities, each of whom had their own responsibilities, were devoutly worshipped by ceramic artisans. The courtyards dedicated to these deities served as public spaces that were open to all townspeople, becoming important venues for communal worship, prayers for industry prosperity, and prayers for favorable weather conditions.

Analysis of the spatial drawing techniques in the Tao Ye Tu

Compared with textual records, images offer distinct advantages in terms of intuitiveness, vividness, and richness of detail (Gou, 2018). The painting style of the Tao Ye Tu reflects the characteristics of the imperial painting academy during the Qianlong period, which was marked by its ornate and refined esthetics. One notable artistic feature of this work is its significant incorporation of Western painting techniques, and the influence of by European art. Since their initial introduction in the late Ming dynasty, Western painting methods had gained considerable influence in the imperial court during the Kangxi to Qianlong periods, as led by missionary painters such as the Italian Giuseppe Castiglione (郎世宁, 1688–1766) and the French Jean Denis Attiret (王致诚, 1702–1768). Many elements in the Tao Ye Tu, including architecture, ceramic tools, and trees, adhere to Western perspective principles, with objects appearing larger in the foreground and smaller in the distance. Architectural features such as columns, window lattices, and tiles—rich in geometric detail—are rendered with light and shade to enhance three-dimensionality. However, in depicting the most critical spatial areas of the composition, the Western emphasis on light effects and strong chiaroscuro is not adopted. Instead, spatial depth is conveyed through the arrangement, overlap, and relative scaling of numerous pictorial elements (Xie and Wang, 2013). At the same time, the Tao Ye Tu exhibits the archaizing style typical of court paintings. The figures are depicted wearing ancient attire, similar to works such as Jiao Bingzhen (焦秉贞)’s Ploughing and Weaving Pictures from the Kangxi period. It is thus evident that the Tao Ye Tu, with its “Sino-Western fusion” style, reflects the open yet discerning attitude of Qianlong-era court painters toward foreign art—embracing external influences without entirely abandoning established conventions.

As an important visual historical document, the Tao Ye Tu objectively records Jingdezhen’s porcelain-making procedures through accurate perspective, rigorous composition, and the clearly detailed depictions of tools. However, images should not be simplistically equated with reality. The painter likely infused their personal artistic style, to introduce subjective expression into the objective representation, which can affect the interpretation of actual spatial layouts. By analyzing these spatial rendering techniques, we can achieve a more accurate understanding and reconstruction of the porcelain production environment and processes of that time.

Combining of temporal–spatial integration and separation

In the Tao Ye Tu, the painter skilfully combines temporal–spatial integration and separation, organically presenting different time and space elements in a single image. This method is used to not only highlight the complex process of ceramic production but to also demonstrates the sophistication of the composition.

The painter used the technique of temporal–spatial integration to depict mining, transportation, and pounding, which occur at different times, in a single image (Fig. 13). In actual porcelain production, these tasks take place during different seasons; specifically, mining typically begins after autumn harvests and ends before the Lunar New Year, as farmers have ample time after the harvest, as the rainy seasons are unfavorable for mining, especially regarding open-pit mines. Transportation and pounding mostly occur in spring and summer when the river levels are high, to facilitate boat transport and water-powered pounding.

Schematic diagram illustrating how processes occurring in different seasons are integrated into a single, continuous production flow within the visual narrative. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

This provides greater momentum. In the image, these processes are integrated into a continuous production flow, emphasizing the overall and continuous nature of ceramic production.

Moreover, the painter also employed the method of temporal–spatial separation, separately presenting some relatively independent procedures to more precisely show the details for each step (Fig. 14). For example, although the scenes for “Dipping and Spraying Glaze” are shown separately, elements such as water wells, mud-washing tubs, mud-resting tubs, drying racks, pottery wheels and saggars can be seen in the background, which indicates that these processes occurred within the same courtyard space as other tasks, such as “Washing and Refining Clay” and “Repairing Moulds for Round Wares”. By independently displaying each process while displaying connections through its background and details, the painting simultaneously highlights both the independence and interdependence of these processes. In the folk exhibition area of Jingdezhen’s ceramic workshops, various procedures were orderly arranged within a quadrangle courtyard, resulting in the formation of a complete production system.

Schematic diagram showing how independent procedures are presented separately to highlight operational details, while background elements indicate their spatial coexistence. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

The combination of temporal–spatial integration and separation in the Tao Ye Tu enhances the depth and narrative quality of the images, enabling viewers to better understand and appreciate a comprehensive view of Jingdezhen’s ceramic production.

Unity of realistic depiction and human settlement ideals

The Tao Ye Tu accurately reflects the procedures for porcelain making. The tools, equipment, and buildings depicted in the images closely resemble existing porcelain-making tools, thereby demonstrating the rigor of technical historical materials. For example, the description of the tool used for kneading clay matches Tang Ying’s detailed account: it includes a bench with vertical wood, a board across it, perforated holes to hold the handle of the mallet, and people sitting on the bench holding the mallet to knead the clay. This shows a high degree of consistency between the text and the image. There is even a scene depicting one person kneading two basins until the second watch of the night, doubling the labor cost, is depicted. Therefore, the documentary nature of the Tao Ye Tu has high credibility. Although whether the three painters ever visited Jingdezhen cannot be verified, the detailed depiction suggests that the images are well researched and realistically depict porcelain production in Jingdezhen.

Additionally, the Tao Ye Tu meticulously portrays courtyard spaces in the scenes of “Decorating Round Wares with Blue and White”, “Decorating and Painting Sculpted Wares”, and “Decorating Round and Sculpted Wares with Overglaze Enamels”, successfully depicting the beauty of garden landscapes. However, whether these garden scenes truly existed or were merely the artistic expressions of the court painters Sun Hu, Zhou Kun, Ding Guanpeng, and others during the Qianlong period remains difficult to verify from the existing ceramic workshops and Tang Ying’s descriptions. Since the painters were familiar with the work scenes that they depicted, they might have incorporated their own experiences and expectations into the portrayal of ornamental courtyards. Therefore, the depiction of ornamental courtyard landscapes may be an embellishment of the ceramic production environment and an expression of the artists’ ideal living environment. This creative approach not only reflects the painters’ recognition and respect for the identity of the porcelain craftsmen but also conveys their self-worth and their aspirations for an ideal work environment.

This interplay between technical depiction and artistic representation in the Tao Ye Tu underscores its dual role as both a documentary source and a work of artistic conception. This synthesis reflects a broader cultural practice in imperial Chinese art, in which functional illustration coexists with humanistic expression. In the album, the rendering of production spaces and craftsmen’s activities not only records workshop layouts and tool usage but also conveys an esthetic ideal of orderly and harmonious labor. Through its nuanced representation of figures, architecture, and natural elements, the Tao Ye Tu goes beyond technical documentation to reveal a humanistic dimension that imbues the industrial process with cultural intentionality and esthetic refinement.

Complementarity of spatial entities and spatial metaphors

The features of the spatial environment depicted in the Tao Ye Tu complement each other through spatial entities and spatial metaphors, thereby revealing the relationship between ceramic production and the spatial environment. For example, although “Loading Greenware into Kiln” and “Firing and Unloading Kiln” are two separate processes, they both occur in kiln houses. Although the kiln house structures are identical, the external environments depicted in the two illustrations differ extensively. “Loading Greenware into Kiln” is depicted in urban areas, whereas “Firing and Unloading Kiln” is depicted in rural settings, suggesting that during the Qianlong period, although the ceramics industry was concentrated in the city, rural kilns continued to operate (Fig. 15).

The comparative diagrams contextualize the identical kiln structures within their distinct environments: (left) an urban setting with dense architecture and walled compounds; (right) a rural setting characterized by open fields and mountainous landscapes. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

Moreover, the illustrator used the background to metaphorically represent the spatial state beyond the ceramic production areas (Fig. 16). In the scene portrayed in “Selecting Cobalt Blue Pigment”, willows are planted outside of the walls, indicating the proximity to rivers. These details provide clues about the workshop’s location and reflect the use of natural resources at the time. The illustration titled “Refining Ash and Preparing Glaze” depicts craftsmen processing ash and preparing glaze materials. Additionally, it portrays a scene in which farmers with farming tools and a vendor selling snacks are interacting on a bridge over a stream, suggesting the multifunctional nature of rural settlements. In the scene entitled “Moulding the Paste and Grinding the Colors”, images of the streets and children playing in alleys further enrich the details of social life, implicitly revealing the layout of Jingdezhen beyond the ceramic workshops, particularly the distribution of lanes along the eastern bank of the Chang River, which reflects frequent and close community interactions. Through these detailed depictions, the Tao Ye Tu not only highlights the production environment and natural landscape but also reveals the complexity of socioeconomic activities and the diversity of people’s lives during the Qianlong period, successfully conveying a dynamic and layered picture of society at that time.

Analytical diagram using background landscape and social scenes to imply the workshop’s location within a broader settlement and natural context. Source: Redrawn and annotated by the authors based on the Qianlong-era Chonghua Palace version reproduced in Huang WC. Tang Ying’s Compilation of the ‘Ceramic Manufacturing Process’ in the Eighth Year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceramics. 2022(2):173–184.

Characteristics of the interaction mechanism between ceramic production and the spatial environment as reflected in the Tao Ye Tu

Ceramic production has a profound interaction mechanism with its spatial environment. This mechanism involves not only the physical space that supports and limits ceramic production but also the shaping and utilization of production activities by the spatial environment to achieve functional maximization and resource optimization. This mechanism has four characteristics: ecology, aggregation, economy, and humanism.

Ecology

Ceramic production relies on natural resources such as minerals, firewood, and water, and the acquisition and utilization of these resources are directly influenced by the spatial environment. In the rural spaces depicted in the Tao Ye Tu, settlements are closely integrated with ecological resources and are often located near mineral deposits and lush forests in flat valleys to ensure access to sufficient raw materials and firewood for porcelain stone processing. Streams either bypass or flow through settlements, providing natural power and water sources for mineral processing. Such a location and layout reduced transportation costs, ensured continuous production, and reflected the harmonious relationship between settlements and natural resources, demonstrating ecological characteristics (Fig. 17). Additionally, courtyard spaces embody the ecological philosophy of following natural paths, thereby showcasing adaptability to climate conditions. The city of Jingdezhen is situated in a hilly basin and characterized by hot summers, cold winters, rainy springs and summers, and dry autumns and winters, with prevailing south or southeast winds. A forming workshop typically faces south to promote clay moisture evaporation, and it contains no windows or doors on the north wall so that summer southeast winds can be utilized while winter northwest winds can be avoided. This layout also avoids intense western sunlight in summer and maximizes winter sunlight, thereby creating comfortable working conditions year-round (Fig. 18).

Aggregation

In traditional ceramic production, each process is closely linked and requires close cooperation among craftsmen of different trades. Of the 20 illustrations of porcelain production processes that are depicted in the Tao Ye Tu, 16 of them are set in courtyard spaces. In conjunction with the previously analyzed spatiotemporal separation technique that was used in both the illustrations and the existing workshop courtyards at the Ancient Kiln Folk Customs Expo Area in Jingdezhen, it can be inferred that multiple porcelain production processes were arranged within the same courtyard space.

Through clever design and arrangement, the aggregated courtyard layout not only simplified logistics and material flow but also promoted seamless integration and efficient collaboration between processes, thereby achieving a smooth and orderly production process (Fig. 19). Additionally, the quiet and private spaces formed by the aggregated courtyards provided security for technical confidentiality. In ceramic workshops, many techniques and formulas are considered valuable trade secrets, to ensure that these technologies were not easily obtained by outsiders when their production occurred in a relatively closed environment.

The economy

In the process of ceramic production, the vertical space design of clay workshops and courtyards fully embodies efficiency. In the scene entitled ‘Penetrating Rafter Frame’ (Chinese Timber Frame Structure with Penetrating Rafters), horizontal beams are set at heights that do not interfere with daily activities, creating multilayered storage spaces (Fig. 20). This design cleverly utilizes indoor vertical space, forming a three-dimensional storage system that allows clay bodies to naturally dry at different levels. This avoids congestion on the ground and ensures that the clay bodies remain unaffected by rainy weather during the drying process to improve production efficiency. Additionally, the courtyard drying racks are portrayed as multitiered, offering flexible placement and retrieval options on the basis of item size and drying requirements. Workers could choose appropriate heights for the drying of unfired clay bodies. Moreover, the space under the drying racks was utilized to store other production tools and materials, such as mud resting tubsmud resting tubs and glaze vats (Fig. 21). This multilevel design significantly improved courtyard usage efficiency, allowing a single courtyard to simultaneously meet multiple production needs.

Through these designs, ceramic production activities effectively reshaped the vertical space of buildings and courtyards, converting areas that were inconvenient for human activity into key storage and production zones, thus maximizing the limited physical space and optimizing the use of the spatial environment.

Human-centric design

The human-centric design of ceramic production equipment and furniture not only effectively reduced labor intensity but also significantly enhanced production efficiency and comfort. In the interior spaces depicted in “Decorating Round Wares with Blue and White”, all the furniture designs closely align with the practical needs of ceramic production. For example, the drawing table—with a lower shelf height of ~80 cm and a width of about 60 cm, and an upper shelf situated at around 150 cm—was specifically designed to suit the working height of painters, allowing them to easily access the upper level for white blanks or completed work while remaining seated. This design minimizes movement and demonstrates a thoughtful arrangement to visual and functional elements. Similarly, in the scene depicting “Decorating and Painting Sculpted Wares”, the table design features an umbrella-like structure with a round surface about 50 cm in diameter, standing around 80 cm high, suitable for placing large vases. The rotating function allowed artists to easily adjust the position of the vase, as with modern rotating dining tables, which greatly facilitated operations. The table’s included includes hidden support components to ensure stability and safety during rotation. Additionally, the design of the potter’s wheels shown in “Making Saggars”, “Repairing Moulds for Round Wares”, and “Throwing Round Wares on Wheel” embodies human-centric considerations. The wheel pit was designed as a round well with a depth of ~60 cm, which matches the diameter of the wheel plate. Part of the wheel post was buried in the pit, whereas the other part extended above ground and was surrounded by boards to prevent scattered clay from accumulating inside the pit. A trapezoidal wooden frame—about 90 cm long, with a front width of roughly 80 cm and a rear width of around 50 cm—was placed above the wheel, serving as a seated working platform for the potter. This design maintained a clean work environment and reduced the difficulty of cleaning clay slurries during operations (Fig. 22).

Conclusion

This investigation into the Qianlong edition of the Tao Ye Tu, by employing iconographic and spatial analysis alongside historical contextualization, uncovers significant insights into the spatial organization of Jingdezhen’s ceramic production. First, our methodical classification of the ceramic production illustrations into categories—woodblock prints, export albums, and imperial court paintings—strengthens our assertion that the Qianlong court version is an indispensable source for spatial analysis. This approach not only enhances the reliability of our source material but also addresses critical concerns about source credibility in the field of visual studies.

Second, our analysis elucidates a complex interaction between ceramic production and its surrounding spaces. The Tao Ye Tu reveals how production activities in Jingdezhen were intricately aligned with both natural and constructed environments: rural areas emphasize the integration with ecological resources; courtyard spaces showcase the optimization of production workflows; and ritual spaces highlight the cultural significance embedded in the production processes. This spatial and functional classification not only charts the distribution of activities but also unveils the operational logic underpinning these arrangements: ecological considerations influenced site and resource choices; efficient layouts facilitated collaborative production and materials management; vertical space utilization and ergonomic designs maximized the efficacy of constrained environments. Together, these elements formed a responsive and integrated production system aligned with the imperatives of imperial patronage and international trade.

Third, by situating the album within a broader spectrum of technical and cultural discourses, our study also interprets its representational tactics and connects its visual rhetoric to ongoing debates in visual culture studies and global production network theory. The analysis shows that court painters employed advanced representational techniques to create a balanced narrative between realistic depiction and idealization, using both physical and metaphorical spaces effectively. Additionally, the inclusion of Western artistic perspectives and the depiction of advanced enamel techniques signal the Qing court’s proactive role in the assimilation of global technological innovations, highlighting the dynamic interplay between local practices and international influences.

However, it is crucial to recognize the limitations of this study. While our source criticism supports the preferential use of the Chonghua Palace version for detailed visual analysis, a comprehensive, scene-by-scene comparison with other versions could further enhance our understanding and remains a promising avenue for future inquiry. Additionally, since the focus of the album is primarily on the imperial kiln operations, it does not encompass the broader scope of Jingdezhen’s ceramic industry, particularly the private kilns. Future studies incorporating archaeological findings or historical texts could provide a more holistic view of the ceramic production landscape in Jingdezhen.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates that the Tao Ye Tu serves not only as a factual account of ceramic production technologies but also as a strategic artistic endeavor that constructs an idealized vision of the industry, reflecting the intricate interweaving of state initiatives, technological advancements, and cultural identity during the mid-Qing dynasty. The spatial configurations and organizational strategies depicted in the illustrations exemplify the sophisticated operational acumen of Jingdezhen as a leading global center for ceramic production, offering valuable historical insights into the interrelations between traditional craft spaces and their socio-economic contexts.

Data availability

All data obtained/ generated has been provided. (Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files).

References

Chen L (2013) Interpretation of historical evidence through images. Southeast Acad (2):231–236

Javier Trujillo F, Claver J, Sevilla L, Sebastian MA (2021) De Re Metallica: an early ergonomics lesson applied to machine design in the renaissance. Sustainability 13(17):7–20

Lockett WG (2001) Jacob Leupold’s analysis of the overshot water-wheel. Proc Inst Civil Eng Water Marit Eng 148(4):211–218

Wang YP (2024) From image fragments to language system: study on the language structure of Jiangnan vernacular landscape based on the analysis on “the pictures of tilling and weaving”. Chin Landsc Archit 40(07):132–137

Chen N, Zhang JN (2014) Analysis of the content value of tang ying’s ‘illustrated explanation of ceramic manufacturing process. J Ceram 35(2):219–224

Wu Q (2020) The inevitability of the birth of the ‘compilation of ceramic manufacturing process. Jingdezhen Ceram 2020(3):20–23

Zong SZ (2018) Reflections on the imagery and historical value of the Qianlong ‘ceramic manufacturing process’. South Cult Relics (2):237–247

Lin YQ (2023) Research on Qing Dynasty porcelain manufacturing illustrations. Jingdezhen Ceram 51(4):139–157

Huang WC (2022) Tang Ying’s compilation of the ‘ceramic manufacturing process’ in the eighth year of Qianlong. Jingdezhen Ceram (2):173–184

Li ZW (2024) Examination of the court painting edition of the ‘Tao Ye Tu’. Cultural Relics World. (1):18–24

Committee JLCC (2020) Annals of Jingdezhen City (1986–2010). Beijing: Fangzhi Press

Zhu HQ (2022) Porcelain narratives of Jingdezhen. Beijing: Beijing Institute of Technology Press

Li SJ (2018) Waterways, trade routes, and the International Spread of Chinese Material Culture: A Case Study of Jingdezhen Porcelain. J Inner Mongolia Arts Univ 15(2):133–177

Peng MH (2011) Zheng He’s voyages to the west: new routes and the export of Jingdezhen Porcelain to Europe and America during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. South Cult Relics. (2):80–94

Xiao X, Chen ZM (2018) Research on the symbolic space of Jingdezhen Ceramic Cultural Landscapes. Nanchang: Jiangxi Fine Arts Publishing House

Zhu S, Zhu MZ (2020) An exploration of the layout and regulation of the imperial Kiln factory in Jingdezhen during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Jingdezhen Ceram (6):17–20

Xing P (2018) Discussion on the Qing dynasty blue and white imperial Kiln factory diagrams on round porcelain plates. Museum. (6):53–59

Zhong YD, Qin DS, Li H (2020) Discussion on the Layout of Porcelain Workshops in the Jingdezhen imperial ware factory during the mid-Ming dynasty—centered on the Archaeological Excavation Data from 2014. J Palace Museum 9:43–60

Yao T, Cai Q (2015) Ancient architecture in Jiangxi. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press

Zhan J (2014) Jingdezhen ceramic workshops — an ecological cultural landscape of harmony between humans and nature. China Cult Herit (3):47–53

Gou MY (2018) The pitfalls and value of image-based historical evidence. Art Observ (9):22

Xie KF, Wang TF (2013) Analysis of the Qing Dynasty Daoguang Imperial Kiln’s blue and white landscape and figures pattern tabletop. Chin Ceram 49(2):53–54

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Southeast University Professor Hu Mingxing for his invaluable guidance on the writing of technical terms in this research. This research was supported by the Jiangxi Provincial Social Science Foundation Project, grant number 21YS37D; the Jiangxi University Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project, grant number YS21103; Jingdezhen Ceramic University Graduate Innovation Fund Project, grant number JYC202506.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WXQ and YJF designed the study. WYT and OYQ created the illustrations. YJF critically revised the work. WXQ wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Yu, J., Wei, Y. et al. Spatial organization and interaction mechanisms in Jingdezhen ceramic production: visual analysis of the Qianlong-era Tao Ye Tu. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 2002 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06273-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06273-x