Abstract

Agriculture faces increasing climate, financial, environmental, and social challenges, which bring into question its ability to withstand shocks and pressures. Strengthening agricultural resilience can effectively address these issues. Reasonably evaluating agricultural resilience and improving it based on climate-smart agriculture practices is particularly important to agricultural sustainability. This research utilized the cloud model and the dynamic fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis approach to evaluate agricultural resilience levels, grounded in the Drive-Pressure-State-Impact-Response framework, across 30 Chinese provinces from 2011 to 2022. It seeks paths to achieve high resilience from CSA technology, climatic productive potential, digitization, and agricultural fiscal expenditure, and analyzes path selection under different grain production areas and levels of digital inclusive finance. Key findings include: (1) Agricultural resilience has shown a gradual upward trend, transitioning from low levels (2011–2014) to moderate (2015–2018) and medium-high (2019–2022) resilience. (2) Three driving pathways for agricultural resilience were identified: the digitalization-technology linkage, digitalization-technology-financial support enhancement, and digitalization-technology-climate resource hybrid approach. (3) Digitization and CSA technologies serve as core pillars, with their integration alongside fiscal spending or climate production potential further boosting agricultural resilience. (4) From the perspective of major grain-producing areas, CSA practices should be customized based on their unique natural conditions and socio-economic environments to enhance agricultural resilience. The path to agricultural resilience also varies under different levels of DIF. The importance of agricultural fiscal expenditure gradually weakens at higher levels of DIF, while digitalization and CSA technologies become key factors at moderate levels of DIF. At lower levels of DIF, digitization, climate production potential, and agricultural fiscal expenditure become strong supports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global agriculture faces converging stresses—from climate change, water scarcity, soil degradation, trade frictions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia–Ukraine conflict—that have raised production costs, pushed up food prices, and heightened food insecurity (Timmer 2022). They also jeopardize current and future food security and sustainable agricultural development (Tendall, Joerin et al. 2015; Seekell, Carr et al. 2017; Andersen, Alston et al. 2018; Birthal and Hazrana, 2019; Dardonville, Bockstaller et al. 2022), with downstream effects on human well-being (Reyers, Moore et al. 2022). As a foundation of national economies, resilient agricultural development and secure food supplies are therefore strategic priorities (Bhatnagar, Chaudhary et al. 2024). In response to these challenges, governments and international organizations have launched initiatives to reduce systemic risks. In 2019, the European Union adopted the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy, the EU Soil Strategy for 2030, and the Farm to Fork Strategy (Zawita-Niedzwiecki 2021). The OECD (2020) synthesized lessons on Strengthening Agricultural Resilience in the Face of Multiple Risks; and the FAO (2021) underscored how climate change, conflict, and macroeconomic downturns intensify food insecurity (Li, Guo et al. 2024). Despite these initiatives, significant uncertainties remain at both global and regional levels. Thus, strengthening the stability, health, and sustainability of agricultural systems has become a global imperative (Hansen, Ingram et al. 2020).

Uncertainty amplifies volatility and vulnerability across farming systems. Coupled with rising expectations for farmer income and uneven educational attainment (Popescu, Popescu et al. 2022), building resilient agricultural systems remains difficult. Some regions have mitigated risks through targeted measures (Yao, Ma et al. 2024), whereas others have stagnated or declined. Following Holling’s introduction of “resilience” in ecology (Holling 2001), the concept has been widely used to characterize an agricultural system’s capacity to absorb shocks, adapt, and transform (Saifi and Drake 2008; Folke, Carpenter et al. 2010; Folke 2016; Bullock, Dhanjal-Adams et al. 2017). However, to translate this theoretical framework effectively into policies and practices, rigorous assessment of agricultural resilience is indispensable (Yang, Zhang et al. 2023). This raises key research questions: How can agricultural resilience be scientifically assessed? What are the dynamics of resilience development? How can weaknesses in resilience be identified? These questions demand further exploration and call for analytical approaches that consider multiple, interacting dimensions of agricultural systems. One promising approach lies within the climate-smart agriculture (CSA) paradigm, where interventions that raise productivity and incomes, bolster adaptive capacity, and reduce emissions can improve resilience (Lipper, Thornton et al. 2014). Yet CSA outcomes hinge on interacting conditions—including climate, technology, digitalization, and public finance (Supit, van Diepen et al. 2010; Patle, Kumar et al. 2019; Cordovil, Bittman et al. 2020; Liu, Wang et al. 2022; Ma and Rahut 2024; Sun, Xia et al. 2024; Vishnoi and Goel 2024). This underscores the importance of examining resilience not only as an outcome, but also as a dynamic process shaped by conjunctural factors. Such a perspective is particularly relevant for understanding how agricultural nations navigate complex trade-offs and pursue pathways toward sustainable development.

China provides a compelling case: as a major agricultural nation facing the dual imperatives of greener and more modern agriculture, its experience has implications for global risk mitigation and adaptive governance (Zhou, Chen et al. 2023). Evaluating China’s agricultural resilience to climate change is therefore both crucial and necessary. Against this backdrop, this study evaluates agricultural resilience in China across 30 provinces from 2011 to 2022 and probes the pathways through which CSA-related conditions shape resilience outcomes.

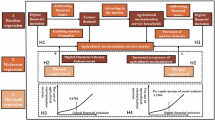

To address these questions, we integrate three complementary methodological approaches. First, the DPSIR framework is adopted to construct a systematic indicator system that captures the full causal chain from socio-economic drivers and environmental pressures to policy responses, offering a holistic lens for operationalizing agricultural resilience. Second, the cloud model is applied to translate diverse indicators into a comparable resilience index, and addressing the fuzziness and randomness in agricultural data. Third, dynamic fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) is employed to identify equifinal configurations of CSA-related conditions—such as digitalization, CSA technologies, climate productivity, and fiscal support—associated with high or low resilience. Together, these approaches provide a comprehensive framework for studying agricultural resilience. Therefore, this study contributes in three ways: First, it introduces the DPSIR framework to agricultural resilience evaluation, creating a comprehensive indicator system. This aims to provide a systematic analytical framework for understanding the response mechanisms of global agricultural systems under climate change and external shocks. Second, it applies the cloud model for more scientifically rigorous and robust resilience measurement. Third, it uses dynamic fsQCA to analyze the impact of multi-factor synergy on agricultural resilience and reveal multiple pathways for resilience enhancement under different development scenarios.

Literature Review

Agricultural resilience

Agricultural resilience is essential for ensuring food security and fostering stable economic growth (Yao, Ma et al. 2024), and has attracted significant scholarly attention. Enhancing agricultural resilience is crucial for ensuring the safety of agricultural production and modernization (Qiao, Chen et al. 2024). Scholarly research has focused on the conceptualization, measurement, and improvement of agricultural resilience. The term “resilience” originated in the natural sciences, such as physics and engineering, referring to an object’s ability to return to its original state after deformation. Holling (1973) first introduced resilience to ecology, and it has been applied in various fields, including social sciences and economics (Bakker, de Koning et al. 2019; Lomboy, Belinario et al. 2019). In economics, Comfort integrated resilience with economic studies, positing that an economic resilience system demonstrates its capacity for self-repair and renewal only after being affected by external shocks, and that this process is non-linear (Zhou, Chen et al. 2023). Since then, the concept has been widely adopted in regional economics (Di Pietro, Lecca et al. 2021) and industrial development (Canello and Vidoli 2020; Grabner and Modica 2022). Agricultural production, similarly influenced by a range of natural, economic, and social factors, often faces issues such as reduced crop yields and environmental degradation. Consequently, research on agricultural resilience has garnered attention (Dardonville, Bockstaller et al. 2022).

Agricultural resilience refers to the ability of agricultural systems to resist, recover, and adapt after exposure to shocks (Meuwissen, Feindt et al. 2019). Research has expanded to agricultural communities (Bowles, Mooshammer et al. 2020; Hasnain, Munir et al. 2023), ecosystems (Anderegg, Konings et al. 2018; Zhao, Fang et al. 2021), and economies (Berry, Vigani et al. 2022). The measurement of agricultural resilience lacks a unified set of indicators. From the agricultural system itself, the core includes the agricultural economy, production, and ecosystems, relying on internal mechanisms to mitigate risks and prevent hazards, thereby advancing high-quality agricultural development. Its measurement often examines aspects such as the agricultural economy, production, and ecosystems (Volkov, Žičkienė et al. 2021; Berry, Vigani et al. 2022; Yang, Zhang et al. 2022). It also evaluates resilience dimensions like resistance and adaptability (Luo, Nie et al. 2024), or uses indicator frameworks like the PSR (Pressure-State-Response) (Jatav and Naik, 2023; Yao, Ma et al. 2024).

Measurement methods include qualitative tools like case studies (Berry, Vigani et al. 2022) and quantitative approaches such as AI (Karanth, Benefo et al. 2023), entropy weight-TOPSIS (Qiao, Chen et al. 2024), and spatial economic geography analysis (Huang and Ling, 2018). Factors influencing resilience include climate change (Burchfield and Poterie, 2018), urbanization (Wang, Shao et al. 2019; Wang, Bai et al. 2021), agricultural inputs (Tao, Ma et al. 2023), and uncertainties (Adhikari, Timsina et al. 2021). Therefore, prioritizing agricultural risk management (Meza, Eyshi Rezaei et al. 2021), increasing agricultural specialization, and enhancing resilience are critical (Vroegindewey and Hodbod, 2018). Enhancing resilience requires diversified agricultural structures (Birthal and Hazrana 2019), insurance (Xie, Zhang et al. 2024), and technological innovations like AI, biochar, and remote sensing (Jung, Maeda et al. 2021; Hasnain, Munir et al. 2023). Fiscal support, efficient water storage, and improved land-use efficiency all play key roles (Smith and Edwards 2021).

Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA)

Climate extremes, such as droughts and floods, pose significant threats to agricultural development (Anderson, Bayer et al. 2020). CSA aims to address these challenges by combining climate adaptation with advanced technologies to improve food production in extreme conditions (Lipper, Thornton et al. 2014; Patra and Babu 2022; Walsh, Renn et al. 2024). CSA is widely recognized as a transformative and sustainable approach that enhances agricultural productivity while addressing climate change (Adesipo, Fadeyi et al. 2020). Its core goal is to achieve climate change adaptation, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and improve resource efficiency through innovative technologies, management practices, and policy support. This paves the way for a modern agricultural development path that meets both environmental protection requirements and economic feasibility. Research highlights CSA’s positive impact on agricultural development, including increased crop yields, higher incomes (Amadu, McNamara et al. 2020), improved food security (Belay, Mirzabaev et al. 2024; Santalucia and Sibhatu, 2024), reduced farmer vulnerabilities (Martinez-Baron, Alarcón de Antón et al. 2024), and lower agricultural greenhouse gas emissions (McNunn, Karlen et al. 2020). These factors collectively contribute to greater resilience (Taylor, 2018).

Based on this consensus, governments, international organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are actively promoting the adoption of CSA. Small-scale farmers worldwide are implementing various CSA practices and technologies, such as reduced tillage, water and nutrient management, crop diversification, and improved pest and disease control (Zakaria, Azumah et al. 2020; Vatsa,Ma et al. 2023). In India, the Climate-Smart Villages initiative has encouraged farmers to adopt CSA practices (Hariharan, Mittal et al. 2020). Similarly, agricultural training programs in Ghana have been used to increase farmers’ knowledge of CSA and promote the adoption of these technologies (Martey,Etwire et al. 2021). It is estimated that by 2030, 500 million farmers worldwide will have adopted CSA technologies (Komarek, Thurlow et al. 2019).

CSA requires more than just technological adoption; it calls for multi-sector partnerships involving farmers, researchers, the private sector, and policymakers to enhance resilience and resource efficiency (Makate, Makate et al. 2019; Zerssa, Feyssa et al. 2021). By fostering community resilience, knowledge sharing, and collective bargaining, CSA empowers smallholders to sustain environmentally friendly practices (Zhou, Ma et al. 2024). Additionally, CSA promotes sustainable land use and ecosystem services through digital technologies (Lajoie-O’Malley, Bronson et al. 2020). However, there is a gap in research exploring the combined effects of climate resources, rural digitalization, and financial support on agricultural resilience. Given the influence of climate resources on crop yields (Chen, Park et al. 2019; Hasanuzzaman, Bhuyan et al. 2020), and the emerging role of digital technologies in food safety and climate adaptation (Cesco, Sambo et al. 2023; Ojo, Kassem et al. 2023), it is crucial to evaluate how these factors work together to optimize CSA interventions.

Evaluation and contribution

Firstly, existing research recognizes the importance of agricultural resilience in modernization. However, current agricultural resilience indicator systems often focus on economic, production, and ecological dimensions, or on the PSR framework, neither of which fully capture the level of resilience. This study develops an evaluation system based on the resistance, recovery, and adaptability of agricultural resilience, using the DPSIR framework. A cloud model is employed to measure resilience values from panel data, addressing gaps in previous assessments. Secondly, CSA emphasizes improving productivity, adapting to climate change, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions—key components of agricultural resilience. However, agricultural production is complex and influenced by economic, social, and natural factors, making a one-size-fits-all approach impractical. Given the limited integration of climate resources, digital technologies, and financial support in CSA research, this study develops region-specific CSA practice combinations to leverage synergies among multiple factors and enhance resilience. It considers CSA technologies, rural digitalization, climate resources, and agricultural finance, using dynamic fsQCA to identify tailored resilience improvement paths within the CSA framework, contributing to high-quality agriculture. Finally, the implementation of CSA varies by region, particularly in major grain-producing areas and those at different stages of digital inclusive finance development. The study rigorously discusses these varying scenarios.

The main innovations of this study are: (1) Methodological Innovation: A cloud model is used to measure agricultural resilience, addressing the fuzziness in indicator dimension selection. The study expands the research scale from cross-sectional data to panel data, applying dynamic panel fsQCA to identify multi-factor combinations that enhance resilience, overcoming the limitations of single-factor analyses. (2) Innovation in Indicator Framework: The study constructs a resilience indicator system based on the DPSIR framework, broadening existing evaluation systems. (3) Enrichment of Research Perspectives: The study explores how CSA practice combinations impact resilience, highlighting differences in CSA paths between major grain-producing regions and areas with varying levels of digital inclusive finance development. This approach offers valuable insights for future research and supports the enhancement of agricultural resilience against external risks. Figure 1 shows the research framework.

The structure of the article is as follows: Section "Materials and Methodologies" details the research methods, data, and sources, including the cloud model and dynamic fsQCA; Section "Results" presents the empirical results; Section "Discussion" discusses the findings; Section "Conclusion and Policy Implications" summarizes the article and offers policy suggestions.

Materials and Methodologies

Methodologies

Cloud model evaluation method

The cloud model, originally proposed by Li Deyi, is a mathematical tool designed to bridge qualitative concepts with quantitative representations under conditions of uncertainty (Li, Liu et al. 2009). Given that the cloud model can overcome the limitations of probability theory and fuzzy mathematics in handling uncertainty, fuzziness, randomness, and correlations, it can effectively address the issues of randomness and fuzziness in agricultural resilience assessment. Therefore, this paper uses the cloud model to evaluate the agricultural resilience level in China. The evaluation follows four main steps:

(1) Compute the expectation (Ex).

We partition the study object—characterized by n evaluation indicators (j = 1, 2, …, n)—into m ordered levels (i = 1, 2, …, m). For indicator j at level i, the level cloud is modeled as two connected one-sided clouds that meet at the expectation Exi, which serves as the boundary between the left and right sub-clouds. Let Lmini and Lmaxi denote the lower and upper bounds of level i, respectively (see Equation 1).

(2) Compute the entropy (En)

The second step is to calculate the entropy value Eni of the connected cloud, as shown in Equation 2.

Entropy reflects the range of variation of the cloud droplets within the domain, that is, how widely the indicator values are dispersed around the expectation. Its computation depends on two constants, ai and ki, as defined in Equation 3. Here, ki denotes the order of the distribution density function corresponding to ai, and its value is influenced by both the length of the interval for level i and the associated half-interval length ai.

The calculation of ai differs depending on whether the evaluation indicator is positive (higher values imply greater resilience) or negative (higher values imply lower resilience):

For a positive indicator, the left and right half-interval lengths of level i are given by Equation 4.

For a negative indicator, the left and right half-interval lengths of level i are given by Equation 5.

Thus, entropy Eni captures the tolerance of indicator values around the expectation for each level, ensuring that both the directionality of indicators and their distribution characteristics are appropriately represented in the evaluation.

(3) Compute the hyper-entropy (He).

The third step is to calculate the hyper-entropy value He of the connected cloud, as shown in Equation 6. Hyper-entropy reflects the uncertainty of the entropy En, that is, the extent to which the cloud droplets deviate from an ideal normal distribution. In practical terms, it measures the stability of the cloud model: a smaller He indicates more concentrated cloud droplets and a more stable evaluation, while a larger He suggests greater fluctuation.

A constant α is introduced to represent the fuzzy threshold of cloud floating. This parameter controls the sensitivity of the model to deviations. Following the characteristics of the parameters and prior research (Zhang and Shang 2023), α is set to 0.01 in this study to ensure stability.

(4) Comprehensive evaluation using the forward cloud generator

Since agricultural resilience assessment requires the transformation from qualitative concepts to quantitative values, a forward normal cloud generator is employed to simulate cloud droplets (see Fig. 2). Based on the numerical characteristics of the cloud C [Ex, En, He] and the classification criteria of indicator level intervals, the generator takes the expectation (Ex), entropy (En), hyper-entropy (He), and the number of cloud droplets (N) as inputs, and outputs the distribution positions of N simulated droplets.

(a) Cloud droplet generation.

First, a normal random number En′ is generated with Ex as the mean and He as the standard deviation. Then, a second normal random number xj is drawn with Ex as the mean and En’ as the standard deviation. Each xj serves as a quantitative realization of the qualitative concept C. Its certainty degree μ(xj)—that is, the degree to which xj belongs to C—is then calculated Equation 7. The pair (xj, μ(xj)) fully captures the qualitative-to-quantitative transformation. Repeating this process iteratively yields N cloud droplets.

(b) Determination of evaluation levels.

Each indicator is assigned to one of L evaluation levels (L = L1, L2, …, Lm), where m is the total number of levels. The forward cloud generator is then used to produce the standard cloud model diagram, which represents the evaluation levels of each indicator.

(c) Calculation of comprehensive certainty.

For each indicator j at level m, the certainty degree μjm is obtained through the cloud generator. The probability of occurrence of each level is represented by these certainty values. The composite certainty degree Rm for each resilience level is then calculated by weighting the certainties with indicator weights (derived from the entropy weight method), as expressed in Equation 8:

where wj is the weight of indicator j, and μjm is the certainty degree of indicator j at level m.

(d) Final determination of resilience level.

Finally, the horizontal characteristic value method is applied to integrate the comprehensive certainties across all levels, yielding the overall agricultural resilience index R (Equation 9), where t denotes the number of levels.

Dynamic fsQCA

The fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) method combines fuzzy set theory with Boolean algebra, integrating both quantitative and qualitative approaches. By leveraging Boolean logic, fsQCA helps reduce variable omission bias and mitigate endogeneity issues that are common in traditional regression models (Wang, Zhang et al. 2023). This approach is particularly effective for uncovering the outcomes of multifactor interactions and identifying multiple pathways that may lead to the same result (Huang, Bu et al. 2023).

In fsQCA, causal relationships are expressed in two forms: necessary conditions and sufficient conditions (Dul 2016). A necessary condition implies that the outcome cannot occur without it, whereas a sufficient condition refers to a specific combination of factors that is adequate to generate the outcome. Within each causal pathway, the presence or absence of variables helps to distinguish between core variables, which show strong causal links to the outcome, and peripheral variables, which have weaker associations (Pappas and Woodside 2021). Different combinations of these variables can thus produce distinct pathways to the same outcome (Beynon, Jones et al. 2020).

Unlike conventional methods that focus on the net effect of single variables or on mediation and moderation effects, fsQCA emphasizes the interplay of causal combinations, thereby revealing the systemic and configurational nature of complex mechanisms (Kumar, Sahoo et al. 2022). However, traditional fsQCA has mainly been applied to cross-sectional data, which limits its ability to capture variations across time and space (Chang and Zhao 2024). To overcome this limitation, this study adopts dynamic fsQCA, which extends the method into the spatiotemporal dimension. This allows us to explore how combinations of conditions evolve over time and across regions, thereby providing deeper insights into the dynamic causal configurations that shape agricultural resilience.

Variables

Dependent variable

The outcome variable is agricultural resilience, a cornerstone of high-quality agricultural development. Agricultural systems comprise economic, social, production, and ecological subsystems (Volkov, Žičkienė et al. 2021; Berry, Vigani et al. 2022; Yang, Zhang et al. 2022). The DPSIR framework—an extension of the PSR framework developed by the European Environmental Agency (EEA)—captures resistance, recovery, and adaptability. This study applies the DPSIR framework to construct an evaluation system for agricultural resilience.

“Driving Force” (D) and “Pressure” (P) address the “why,” factors that influence agricultural resilience. Driving forces include economic development, food security, and higher farmer incomes, while pressures include population aging in rural areas, environmental pollution, and agricultural disasters.

“State” (S) and “Impact” (I) describe the “how” of the agricultural system after disturbances. State refers to the condition of the agricultural industry, household consumption, and rural labor; impact concerns shocks arising from agricultural pollution, population aging, and changes in farmers’ living standards associated with economic development.

“Response” (R) answers “what to do,” focusing on actions to mitigate disturbances, such as advancing agricultural technology, increasing mechanization, boosting research investment, expanding agricultural fixed assets, and implementing soil- and water-conservation measures.

A total of 24 indicators are selected to build the agricultural resilience evaluation system, guided by principles of scientific rigor, system coherence, representativeness, and feasibility (see Table 1).

Conditional variables

This study examines CSA technologies—water-saving irrigation, no-tillage planting, and straw incorporation—implemented at different stages of production (Sun, Xia et al. 2024). No-tillage reduces soil disturbance (Cordovil, Bittman et al. 2020), while water-saving irrigation enhances economic and ecological benefits via advanced techniques such as drip and pipeline irrigation (Patle, Kumar et al. 2019). Straw incorporation boosts soil fertility by decomposing straw into essential nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic matter (Liu, Wang et al. 2022). These technologies, which are widely used in China (Guo and Zhang 2023), are key to advancing CSA practices and strengthening agricultural resilience.

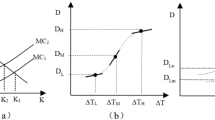

The effectiveness of CSA practices is influenced by factors such as climate conditions (Supit, van Diepen et al. 2010), digital development (Ma and Rahut 2024), and fiscal policies (Sun, Xia et al. 2024). Climatic potential productivity, which reflects the optimal biological yield achievable under ideal climate conditions, is crucial for effective CSA implementation, as favorable climates conditions can reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and increase yields (Lipper,Thornton et al. 2014). This study calculates regional climatic potential productivity using the Thomthwaite Memorial model, with the Equation 10, Equation 11 and Equation 12:

Where: PET denotes climate production potential (gm-2 a-1); ET denotes mean annual average evapotranspiration (mm); E0 denotes annual potential evapotranspiration (mm); R denotes annual precipitation (mm); and T denotes the mean annual temperature (°C). Equation 11 and Equation 12 apply if and only if R ≥ 0.316E0; when R < 0.316E0, set E0 = R.

Digitalization underpins the implementation of CSA, boosting agricultural productivity (Vishnoi and Goel 2024). The extent of rural digitalization is measured by rural broadband access and digital inclusive finance (Zhao and Zhao 2024). Fiscal support helps mitigate the impacts of extreme weather and market fluctuations, ensuring food safety (Sun, Xia et al. 2024). The share of agricultural, forestry, and water expenditures in total fiscal spending reflects the level of fiscal support for agriculture, as shown in Table 2.

Research scope and data sources

This research analyzes agricultural resilience across 30 Chinese provinces from 2011 to 2022, covering the vast majority of the country’s agricultural areas and representing a wide spectrum of development levels—from highly developed coastal regions to less developed inland areas. This selection does not include Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan due to data limitations. For the purpose of path analysis, the provinces are categorized into 13 major grain-producing areas and 17 non-major grain-producing areas.

The data used in this study are drawn from authoritative national statistical sources to ensure reliability and comprehensiveness. Data on agricultural production, ecology, rural economy, and farmers’ livelihoods are obtained from the China Rural Statistical Yearbook. Agricultural R&D investment data are drawn from the China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, while agricultural patent data are obtained from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). Rural population data are sourced from the China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook, and data on rural broadband access and agricultural expenditures are obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook. The digital inclusive finance index, crucial for assessing rural digitalization, is provided by Peking University’s Digital Finance Research Center. Finally, data on CSA technologies are obtained from the China Agricultural Machinery Industry Yearbook.

Results

Evaluation of Agricultural Resilience Levels

Determining the evaluation criteria for agricultural resilience

According to relevant literature, agricultural resilience is divided into five evaluation levels: I, II, III, IV, and V—corresponding to very low, low, moderate, high, and very high resilience, respectively (Zhang and Shang 2023). Indicator intervals are defined using percentile-based cutoffs. To limit the influence of extreme values and following prior studies, we set the lower and upper cutoffs at the 10th and 90th percentiles, and evenly partition the middle range into three levels (Huang, Zhang et al. 2021; Zhang and Shang 2023). The resulting classification is: 0–10% (Level I), 10%–36% (Level II), 36%–62% (Level III), 62%–90% (Level IV), and 90%–100% (Level V).

Computing the digital characteristics of the cloud model

Based on the boundary values of the evaluation levels, the numerical characteristics of the cloud model are calculated using Equation 1 to Equation 6, and the results are summarized in Table 3. The three values in parentheses in Table 3 represent Ex, En, and He, respectively (Zhang and Shang 2023).

Establishing agricultural resilience evaluation criteria

Cloud models for the evaluation indicators were generated using the parameters Ex, En, and He, and the results were averaged across 2000 model runs to reduce randomness. For brevity, only six representative indicators are displayed in Fig. 3.

a Cloud model for Agricultural output value (C1), a positive indicator; b cloud model for Grain yield (C4), a positive indicator; c cloud model for Aging population (C5), a negative indicator; d cloud model for Agricultural carbon emissions (C15), a negative indicator; e cloud model for Agricultural research expenditure (C22), a positive indicator; f cloud model for Agricultural technological patents (C23), a positive indicator.

The legends of Fig. 3 indicate whether the indicators are positive or negative. When the initial cloud droplet, shown in red, appears at Level V, it denotes a negative indicator, where smaller values are more favorable for agricultural resilience. For example, Fig. 3d illustrates that agricultural carbon emission intensity is a negative indicator: higher emission intensity hinders the development of green agriculture, suppresses resilience, and correlates inversely with resilience levels. In contrast, Fig. 3f illustrates that agricultural patents are a positive indicator, with a higher number of patents reflecting greater technological advancement and resilience.

A wider value range for a resilience indicator at a given level increases the likelihood that cloud droplets fall within that level. For values near Level I or Level V, those below or above Ex are assumed to have a 100% probability of belonging to the respective level.

Agricultural resilience evaluation results

Based on the constructed evaluation system, the certainty for each agricultural resilience level was derived using the forward standard cloud generator. The comprehensive certainty for each level was then obtained through the entropy weight method (Lee and Chang 2018) and Equation 8. These results provide the basis for analyzing the spatiotemporal evolution of agricultural resilience in China.

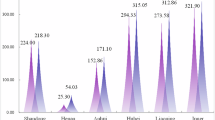

As shown in Fig. 4, the lengths of the bars, ranging from red for Grade I to green for Grade V, represent the membership degrees of agricultural resilience in Grades I to V, respectively. For each year on the horizontal axis, a longer bar in a higher-grade color indicates a greater probability that the agricultural resilience for that year is at a higher grade. China’s average agricultural resilience level increased from Grade II (2011–2014) to Grade III (2015–2018), and further to Grade IV (2019–2022), indicating significant progress and reaching an upper-middle level in recent years.

Based on the spatial and temporal evolution map of agricultural resilience levels across 30 provinces (municipalities) in China (Fig. 5), the study found that the agricultural resilience levels between regions exhibit significant spatial differentiation due to differences in industrial structure, policy responses, and resource endowments.

a Spatiotemporal distribution of the first resilience level (low resilience) from 2011 to 2022; b spatiotemporal distribution of the second resilience level (low-to-moderate resilience) from 2011 to 2022; c spatiotemporal distribution of the third resilience level (moderate resilience) from 2011 to 2022; d spatiotemporal distribution of the fourth resilience level (moderately high resilience) from 2011 to 2022; e spatiotemporal distribution of the fifth resilience level (high resilience) from 2011 to 2022; f spatiotemporal evolution of the comprehensive agricultural resilience index from 2011 to 2022.

Figure 5a shows the spatiotemporal distribution of the first resilience level (low resilience) from 2011 to 2022. The national average membership value rose from 0.081 in 2011 to 0.184 in 2022. At the provincial level, Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Xinjiang, Jilin, and Gansu recorded relatively high values, with Heilongjiang peaking at 0.472 in 2020. In contrast, provinces such as Hebei, Shanxi, Jiangxi, and Hunan consistently showed lower values, mostly below 0.1.

Figure 5b depicts the distribution of the second resilience level (low-to-moderate resilience). The national average membership value increased from 0.182 in 2011 to 0.322 in 2022. Provinces such as Sichuan, Hubei, Henan, Shandong, Anhui, Liaoning, and Hebei recorded relatively high values, while Heilongjiang and Gansu also showed an upward trend. In coastal provinces such as Zhejiang and Shanghai, values fluctuated considerably, whereas Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Jiangxi, and Qinghai exhibited smaller changes.

Figure 5c presents the distribution of the third resilience level (moderate resilience). The national average membership value increased slightly from 0.219 in 2011 to 0.259 in 2022. Provinces such as Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Jiangxi, and Henan displayed gradual increases, whereas Hebei, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Anhui, Shandong, Hubei, Hunan, and Sichuan declined. Non-grain-producing regions such as Tianjin, Shanxi, Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Gansu remained relatively stable.

Figure 5d reveals the distribution of the fourth resilience level (moderately high resilience). The national average membership value declined from 0.202 in 2011 to 0.075 in 2022. Provinces including Jiangsu, Shandong, Zhejiang, and Guangdong recorded increasing values, particularly after 2020, while Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, and Liaoning showed persistently low or declining values.

Figure 5e illustrates the fifth resilience level (high resilience). The national average membership value fell from 0.316 in 2011 to 0.159 in 2022. Except for Qinghai, where values increased slightly, most provinces showed a downward trend.

Figure 5f shows the comprehensive resilience index across 30 provinces. The national average increased from 2.624 in 2011 to 3.379 in 2022. Hubei recorded the largest increase (from 2.62 to 3.79), while Beijing had the smallest (from 2.55 to 2.84). In terms of annual growth rates, Beijing was the lowest (0.95%) and Guizhou the highest (3.60%). Spatial disparities are evident: Beijing, Shanghai, Qinghai, and Hainan consistently recorded lower values, while Heilongjiang, Shandong, and Sichuan remained higher. From 2016 to 2019, most provinces showed steady growth, followed by greater fluctuations after 2020.

Configuration analysis

Configural analysis focuses on how multiple antecedent conditions combine into distinct configurations that jointly explain the occurrence of an outcome, emphasizing conjunctural causation rather than the independent effect of single variables. Unlike traditional regression-based methods that assume linear and additive effects, this approach recognizes that different combinations of conditions may lead to the same outcome through alternative pathways. In the context of this study, agricultural resilience is not determined by a single factor but emerges from the complex interplay of technological, financial, digital, and climatic dimensions. Therefore, the dynamic fsQCA method is adopted to capture how these condition sets evolve over time and to identify multiple, time-sensitive pathways through which resilience can be enhanced under the framework of climate-smart agriculture (CSA). By integrating the temporal dimension, dynamic fsQCA provides a more nuanced understanding of how changing policy environments, technological adoption, and resource endowments shape resilience trajectories across regions.

Data calibration

Dynamic fsQCA requires calibrating raw measures into fuzzy sets and assigning membership scores to each province–year case on every condition and the outcome. Following established practice (Pappas and Woodside 2021), we applied direct three-anchor calibration. For each variable, full membership, the crossover, and full non-membership were set at the pooled 2011–2022 percentiles of 95%, 50%, and 5%, respectively, to ensure temporal comparability. Since all indicators in this study are defined as positive contributors to resilience, no reverse-coding was required. The resulting fuzzy-set scores μ ∈ [0,1] and the variable-specific anchors are reported in Table 4. Sensitivity to alternative anchors (e.g., 90%–50%–10%) is examined in Section “Robustness test”.

Necessity analysis

Before conducting the configural analysis, a necessity analysis of individual antecedent conditions is performed to determine whether any single condition is essential for the outcome. A condition is considered necessary if its presence is required for the outcome to occur, though its presence alone does not guarantee the outcome. According to relevant literature (Schneider and Wagemann 2012), a consistency score above 0.9 indicates that the condition is necessary for the outcome. However, as shown in Table 5, all conditions in this analysis have consistency scores below 0.9, meaning no single factor is sufficient on its own. This suggests that agricultural resilience, within the context of climate-smart agriculture (CSA), is influenced by a combination of factors rather than by any one condition.

Analysis of sufficient condition configurations

To identify different combinations of conditions that lead to the same outcome, sufficiency analysis of configurations is performed (Wang, Zhang et al. 2023). The sufficiency criterion requires a consistency level of 0.75 or higher (Schneider and Wagemann 2012). Based on previous studies (Wang, Zhang et al. 2023) and the specific context of this research, both the consistency and PRI thresholds were established at 0.85.

In the counterfactual analysis, no assumptions were made regarding the presence or absence of conditions in order to avoid subjective bias. Augmented intermediate and simplified solutions were applied to derive the configuration results, identifying core and peripheral conditions. These findings are presented in Table 6.

In Table 6, the consistency values for the six configurations of high agricultural resilience (H1–H3) are 0.983, 0.98, 0.983, 0.98, 0.981, and 0.986, all above 0.75, indicating that the explanatory power of the conditions is strong. Overall, the consistency across the six configurations is 0.975, meaning that 97.5% of the cases align with these paths, showing a significant contribution. The entire solution accounts for 56.0% of high resilience cases. The research results can be further summarized into the following pathways: “Digital-Technology Synergy” (H1), “Digital-Technology-Financial Support Enhancement” (H2a, H2b), and “Digital-Technology-Climate Resource Synergy” (H3a, H3b, H3c).

The “Digital-Technology Synergy” path (H1) includes core conditions of Water-Saving Irrigation, Straw Returning to the Field, and Digital Financial Inclusion Index, with No-Tillage Technology as a peripheral condition. This suggests that the promotion and use of rural digitalization provides a platform for smallholder farmers to access advanced agricultural technologies, management expertise, and inclusive finance. In addition, technologies such as Water-Saving Irrigation and Straw Returning to the Field enable agricultural production to rapidly adapt to climate change (Mango, Makate et al. 2018). By increasing farmers’ awareness and improving access to funding, the adoption of CSA (Climate-Smart Agriculture) technologies can be enhanced (Everest, 2021), promoting sustainable and high-quality agricultural development, thereby improving agricultural resilience. This path is particularly relevant for major grain-producing provinces such as Henan, Hebei, and Inner Mongolia. These regions have a relatively solid agricultural foundation, and although their Climate Productivity Potential is weak, as seen in extreme rainfall events in Henan in 2021 and Hebei in 2023, and dust storms in Inner Mongolia in 2022, the frequent natural disasters negatively impact agricultural production. However, through the Digital-Technology synergy, agricultural resilience can be effectively improved.

Another key pathway is the “Digital-Technology-Financial Support Enhancement” path (H2a, H2b). In the H2a path, No-Tillage Technology, Rural Digitalization, and Digital Financial Inclusion Index are core conditions, with Agricultural Fiscal Expenditure as a peripheral condition supporting agricultural resilience. In the H2b path, Water-Saving Irrigation, Straw Returning to the Field, and Digital Financial Inclusion Index are core conditions, while Rural Digitalization and Agricultural Fiscal Expenditure serve as peripheral conditions. Although these two sub-pathways (H2a and H2b) emphasize different configurations of core technologies and digital factors, they both highlight the importance of Digital Financial Inclusion as a core driving force. This force works effectively with different agricultural technologies (soil protection-focused in H2a vs. resource-circular in H2b), supported by Rural Digitalization and Agricultural Fiscal Expenditure, which provide flexible support to create stable and efficient resilience-enhancing solutions. The improvement of agricultural resilience does not rely on a single “optimal solution” but can be achieved through the “Digital-Technology-Financial” framework. Depending on the regional resource endowments and stages of development, a flexible configuration of technologies and policy tools can lead to resilience-building outcomes (Kabato, Getnet et al. 2025). This model is suitable for regions like Gansu and Xinjiang, which are arid and have weak climate productivity potential.

The “Digital-Technology-Climate Resource Synergy” path (H3a, H3b, H3c) emphasizes the impact of climate resources. In these three paths, Water-Saving Irrigation and Straw Returning to the Field, along with Digital Financial Inclusion Index, remain core conditions, while Climate Productivity Potential and Rural Digitalization provide peripheral support. This can be explained by the fact that, driven by rural digitalization, digital financial inclusion has made significant progress, providing farmers with the financial support needed to develop industries and adopt green technologies. Additionally, higher Climate Productivity Potential benefits the implementation of CSA technologies, which, in turn, promotes the development of green ecological agricultural models (Rong, Hong et al. 2023). These paths show that the improvement of agricultural resilience depends not only on core drivers that are universally applicable across different contexts but also on differentiated support strategies that align with local climate resource endowments. Therefore, in regions with different climate resource endowments, as long as the core foundation of resource-circulation technologies and digital financial support is solid, combined with matching digital services or climate adaptation management, high agricultural resilience can be achieved. Typical cases include agricultural resource-rich regions such as Hunan, Sichuan, and Jiangsu, which focus on agricultural technological innovation.

In contrast, the low agricultural resilience configurations (L1 and L2) reveal the reasons for insufficient resilience. In the L1 path, Climate Productivity Potential is the core condition, while the absence of No-Tillage Technology, Water-Saving Irrigation, Straw Returning to the Field, Rural Digitalization, and Digital Financial Inclusion Index leads to low agricultural resilience (Adegbite and Machethe 2020). This indicates that even with favorable natural conditions, if essential technologies and digital financial support are lacking, the system remains vulnerable. In the L2 path, although Agricultural Fiscal Expenditure is a core condition, the absence of other key conditions still results in low agricultural resilience. This suggests that fiscal expenditure alone, without a supporting technological system, resource management measures, and digital empowerment, cannot effectively translate into robust system resilience.

Regional analysis

CSA practices demonstrate varying levels of effectiveness between major and non-major grain-producing areas. Major grain-producing areas, characterized by favorable climatic conditions, fertile soils, and abundant water resources, play a key role in national food security. This study adopts the classification criteria outlined in the National Grain Security Medium- and Long-Term Planning Outline (2008–2020) to analyze configuration solutions for these regions separately, accounting for regional differences. The analysis results are shown in Table 7.

As shown in Table 7, the configuration analysis for major grain-producing areas aligns closely with the “Digital-Technology Synergy”, “Digital-Technology-Fiscal Support Enhanced”, and “Digital-Technology-Climate Resource Synergy” models.

In G1, the core condition is the Digital Financial Inclusion Index, supported by peripheral conditions such as No-Tillage Technology, Water-Saving Irrigation, and Straw Returning to the Field, while Climate Productivity Potential is absent. This suggests that strong digital finance compensates for weaker natural advantages by reducing technology adoption costs and improving resource allocation. In G2, the core conditions are Water-Saving Irrigation, Straw Returning to the Field, and Agricultural Fiscal Expenditure, with No-Tillage Technology as a peripheral condition and Climate Productivity Potential absent, highlighting a policy focus on investing fiscal resources in resource-saving technologies under environmental pressures. G3 and G4 both center on the Digital Financial Inclusion Index but differ in their peripheral conditions: G3 includes Climate Productivity Potential, Water-Saving Irrigation, Straw Returning to the Field, and Rural Digitalization, while G4 emphasizes Climate Productivity Potential, Water-Saving Irrigation, and Rural Digitalization, with No-Tillage Technology absent. This shows that areas with better climate conditions benefit from combining digital finance with rural digital infrastructure. In G5, the core conditions are Climate Productivity Potential, No-Tillage Technology, and Rural Digitalization, supported by the peripheral conditions Water-Saving Irrigation and Straw Returning to the Field. This indicates that in regions with favorable natural conditions, conservation tillage and digitalization boost resilience, with water- and soil-management technologies enhancing but not driving resilience.

In non-grain-producing regions, N1 and N2 both feature Water-Saving Irrigation and Agricultural Fiscal Expenditure as core, but commonly lack Climate Productivity Potential or Straw Returning to the Field among the peripheral conditions. This pattern reveals a reliance on a narrow, fiscally supported technology set in the face of resource constraints, with insufficient ecological practices and limited multi-factor synergies to sustain resilience gains.

Different levels of inclusive finance

Digital financial inclusion enhances financial accessibility, driving rural industrial revitalization and supporting CSA practices. However, regions with varying levels of financial inclusion follow different CSA pathways. To assess this impact, the study uses the equal interval method to categorize financial inclusion into three groups—high, medium, and low (Tang, Li et al. 2020). Configuration solutions for each group are then analyzed to identify distinct CSA pathways, as shown in Table 8.

High DFI regions: As shown in Table 8, the Digital Financial Inclusion (DFI) Index is the core driver of agricultural resilience. In H1, H4, and H5, DFI combines with water-saving irrigation and rural digitalization to strengthen sustainability and adaptive capacity. Inclusive finance does more than widen credit access; paired with data-enabled services, it raises efficiency and improves factor allocation. By contrast, in H2, H3, and H6, DFI remains core but resilience gains are capped when complementary technologies or public spending are absent—for example, without agricultural fiscal expenditure or no-tillage technology, systems can stay fragile despite strong DFI. Finance alone is insufficient; it must be coupled with technology diffusion and public investment. Resource-constrained areas also have room to expand the coverage and effectiveness of financial services.

Medium DFI regions: Resilience can still rise through coordination among other conditions. In M1, M2, and M4, core technologies—no-tillage and straw returning—combined with peripheral supports (water-saving irrigation and agricultural fiscal expenditure) provide a workable path to upgrading resilience. This suggests that even where DFI is nascent, pairing technological innovation with fiscal inputs advances sustainable development. In M3, M5, and M6, however, the absence of climate productivity potential and water-saving irrigation limits improvements even when straw returning and DFI are core. Policymakers should integrate technology diffusion with financial services, avoiding reliance on a single lever and accounting for local resource constraints.

Low DFI regions: Scarce digital finance markedly constrains upgrading. Although technologies such as no-tillage and water-saving irrigation may be core, weak fiscal support and limited digital services make gains hard to sustain. In L1 and L2, these technologies are core, but weak agricultural fiscal expenditure and minimal rural digitalization blunt their impact, entrenching reliance on traditional techniques and ad hoc support. In L3, even with climate productivity potential and fiscal spending as core conditions, resilience is difficult to lift without reinforcing effects from DFI and rural digitalization. The structural bottleneck is clear: limited information and liquidity make resilience building especially challenging. Priorities should include strengthening rural financial systems, improving financial literacy, and expanding the reach and usability of digital finance so that technology adoption can be financed at scale and the sector can shift toward a more resilient, modern production paradigm.

Robustness test

Robustness tests on thresholds and anchors were conducted to confirm the results, as shown in Table 9. First, the consistency threshold was raised from 0.85 to a stricter 0.90. The results showed that the consistency of all high agricultural resilience paths (H1–H3) remained above 0.975, and the composition of all core conditions (such as digital inclusive finance, water-saving irrigation, etc.) did not change (as shown in Table 6). Next, we adjusted the calibration anchor points (setting the full membership, crossover point, and full non-membership points to the 90%, 50%, and 10% percentiles, respectively) to alter the distribution of set membership. Under this setting, although some marginal conditions changed and the overall coverage experienced only a slight fluctuation (from 0.560 to 0.542), the core condition combinations driving high resilience and theoretical paths (such as “digitalization-technology” synergy) remained stable. These checks indicate that the configuration analysis results are not sensitive to changes in parameter settings, and the core conclusions are robust.

Discussion

Evolutionary characteristics and enhancement pathways of agricultural resilience in China

This study analyzes the dynamic evolution of agricultural resilience in China at both the national and provincial levels from 2011 to 2022. At the national level, agricultural resilience shows expansion in the medium-low and medium levels, and contraction in the medium-high and high levels, indicating that while agricultural resilience in China has improved, it still faces structural challenges in transitioning from traditional production models to medium-high resilience systems. This may be due to the agricultural policy system focusing more on “engineering resilience”—the ability to restore agricultural facilities to their pre-shock state—while “evolutionary resilience”—the ability to adapt, learn, and transform—remains relatively weak. This is consistent with the views of Zhou et al. (Zhou, Han et al. 2021). Particularly after 2020, the combined impacts of the pandemic and climate change slowed the growth of agricultural resilience and increased volatility, further exposing weaknesses in adaptation and transformation mechanisms. At the provincial level, traditional agricultural provinces, such as Hebei, Liaoning, and Shandong, have experienced slow agricultural transformation due to their traditional production models, climate change pressures, and delayed policy responses. In contrast, non-traditional agricultural regions, such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, have achieved higher levels of resilience improvement through innovation-driven approaches, increased R&D investment, and policy guidance.

Digital inclusive finance plays a key role in several resilience-enhancing pathways, aligning with the “digital countryside” policy, which prioritizes financial technology channels and data infrastructure in core grain-producing areas (Yang, Ji et al. 2024). For instance, in pathways such as “digital-technology synergy”, the combination of water-saving irrigation and straw returning measures with digital inclusive finance has significantly enhanced agricultural resilience. Existing studies have shown (Liu, Liu et al. 2021) that digital finance not only helps expand agricultural production financing channels but also promotes the adoption of new agricultural production technologies by reducing transaction costs. In regions with lower climate productivity, digital finance can somewhat compensate for the adverse effects of climate shortcomings. In areas with more favorable climate conditions, digital finance can deeply integrate with rural digitalization, significantly amplifying the efficiency of precision services and market linkages, thereby enhancing the agricultural system’s ability to cope with risks. This finding reminds us that meaningful resilience improvements are unlikely to be achieved through just one or two factors. For example, climate adaptation strategies must be combined with technological promotion and fiscal support to effectively enhance resilience, which is consistent with previous research conclusions (Tran, Rañola et al. 2020).

There are differences in the pathways for enhancing agricultural resilience between major grain-producing regions and non-grain-producing regions. In grain-producing areas, the combination of water-saving irrigation and straw returning frequently appears in the pathways, indicating that water resource management and soil improvement are key to agricultural resilience. Existing studies have shown that under the context of climate change, water-saving irrigation can improve water use efficiency (Guo and Zhang 2023; Xuan, Bai et al. 2025), and straw returning helps improve soil fertility and enhance crop resistance to stress (Zheng, Zhu et al. 2022), The widespread application of these technologies not only enhances agricultural sustainability but also strengthens the agricultural system’s ability to cope with climate change (Devkota, Devkota et al. 2022). In non-grain-producing regions, however, there is often a dual constraint: insufficient climate productivity and a lack of straw-returning technology, with water resource management and policy support being key factors for improving agricultural resilience (e.g., N1 and N2 pathways). Consistent with the views of Fang et al. (Fang and Zhu 2024), the combination of water-saving irrigation and fiscal support can help farmers better address technological shortcomings and enhance the agricultural system’s resilience to risks.

Theoretical contributions

High levels of agricultural resilience contribute to agricultural modernization and high-quality agricultural development (Qiao, Chen et al. 2024). Agricultural production is influenced by various factors, especially the challenges posed by the “dual carbon” goals, extreme climate change, and the instability of international affairs. The use of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) technologies can effectively mitigate carbon emissions, ensure food security, and promote sustainable agricultural development. The study of the combined impact of multiple factors on agricultural resilience in the context of climate-smart agriculture provides a new and interesting perspective. This research focuses on agricultural resilience and employs the dynamic fsQCA method to identify the impact of various factor combinations on agricultural resilience. The results show that different combinations of factors yield different effects (Guedes, da Conceição Gonçalves et al. 2016). The use of CSA technologies and digitalization is fundamental to achieving these pathways, further confirming the importance of digital development and climate-smart technologies in enhancing agricultural resilience, such as improving agricultural productivity and reducing carbon emissions in agriculture (Lipper, Thornton et al. 2014; McNunn, Karlen et al. 2020).

The theoretical contributions of this study are as follows: First, based on the DPSIR framework, an innovative evaluation index system for agricultural resilience is constructed, and the cloud model is used to assess the resilience levels and statuses of dynamic panel data, filling the gap in existing literature. Second, using the dynamic fsQCA method, the study identifies three pathways based on the context of climate-smart agriculture: the “digitalization + technology” interactive pathway, the “digitalization + technology + fiscal support” enhanced pathway, and the “digitalization + technology + climate resource support” mixed pathway. The study explores how various factor combinations, such as digital finance, technological innovation, fiscal support, and climate resources, interact to shape resilience outcomes. This nuanced understanding of the complementarity and substitutability of different elements adds depth to agricultural resilience theory, particularly in contexts influenced by climate change and technological transformation. In this way, the study provides a more comprehensive and dynamic theoretical framework that goes beyond traditional single-factor theories. Lastly, the proposed combination pathways are superior to traditional single-factor theories and establish a more comprehensive theoretical framework.

Practical Implications

In addition to theoretical contributions, this study holds significant practical value, particularly in promoting resilience in agricultural systems, formulating relevant policies, and implementing agricultural technology innovations. The key practical implications are as follows:

(1) The results of this study reveal the key factors required in different regions and resilience pathways, offering policymakers valuable insights into designing tailored agricultural resilience policies. For instance, in grain-producing areas, policies should focus on the integration of digital financial services and agricultural technology innovations, while in non-grain-producing areas, the focus should be on increasing fiscal support and promoting advanced agricultural technologies.

(2) For agricultural technology promotion systems, this research offers a clear “priority list” and “combination strategy” to address the common dilemma faced by agricultural extension services and farmers regarding which technologies to prioritize. Given the numerous CSA technologies available, this study identifies the core and auxiliary roles of various technologies in building agricultural resilience.

(3) Agricultural service enterprises can leverage the research to offer customized “resilience enhancement service packages” tailored to the specific needs of different regions. For instance, by providing a “G4 pathway full-service package” in a particular province, agricultural service providers can become specialized solution suppliers, offering comprehensive services that address both technological and financial needs. These service packages could include everything from technology adoption and training to ongoing financial and technical support, ultimately helping farmers strengthen their resilience against climate-related challenges.

International comparative value

This study offers a valuable international comparison framework for enhancing agricultural resilience globally. Its international comparative value is reflected in the following aspects:

(1) Comparing Resilience Pathways Across Countries

By comparing resilience pathways in major and non-major grain-producing regions, this study reveals both shared challenges and regional differences in enhancing agricultural resilience. For example, developed countries typically lead in digital finance and technological innovation, while developing countries face challenges related to technological gaps and limited financial resources. The study provides valuable reference points for countries to tailor their resilience-enhancing strategies based on their specific contexts.

(2) Global Perspective on Climate Change Adaptation

The study highlights the profound impact of climate change on agricultural resilience and explores how different regions are adapting to these challenges. The findings offer a basis for international knowledge sharing and collaboration on climate change adaptation strategies, particularly in areas such as water resource management and soil protection. Global cooperation in technology transfer and financial support is essential to help vulnerable regions increase resilience.

(3) Global Agricultural Digitalization and Fiscal Support Collaboration

The study demonstrates the pivotal role of digital finance and technological innovation in enhancing agricultural resilience. By comparing countries with different levels of digital finance inclusion, the study highlights the potential for cross-country cooperation. Developed countries can share their digital experiences and provide funding to help other regions accelerate digital transformation in agriculture. Such international cooperation will not only improve agricultural productivity but also strengthen global agricultural systems’ ability to adapt to climate change, ensuring the stability and sustainability of global agriculture.

Research limitations

This study makes significant contributions to the pathways for achieving agricultural resilience, but there are some limitations. First, it constructs the evolution trend of agricultural resilience using panel data from 2011 to 2022, but with increased uncertainty in agricultural systems due to climate change, policy iterations, and technological innovations, future research could incorporate higher-frequency data (e.g., quarterly or monthly) to capture resilience responses to short-term shocks. Second, while the study relies on macro-level statistical data, it has limitations in reflecting grassroots perceptions. Future studies could combine surveys and interviews with stakeholders, such as farmers and local policymakers, to provide more contextualized resilience narratives and highlight obstacles in technology promotion and policy implementation. Third, the study uses dynamic fsQCA to identify paths and drivers of agricultural resilience, and future research could combine these findings with predictive methods like machine learning or system dynamics to create an “Agricultural Resilience Scenario Simulation System” for optimizing resilience paths under various policy and climate scenarios.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

Conclusion

This study systematically examines the spatiotemporal evolution and formation mechanisms of agricultural resilience in China from 2011 to 2022, drawing the following key conclusions:

Although agricultural resilience in China has improved overall during the observation period, internal structural imbalances have become more pronounced. The national average resilience level has increased from Level II to Level IV. However, the narrowing of the medium-high and high resilience tiers, along with the expansion of the medium-low tiers, reveals a challenge in transitioning the system from “incremental growth” to “quality enhancement”. This structural dilemma is particularly evident across provinces: traditional agricultural provinces are constrained by path dependencies related to natural conditions and industrial structures, leading to slow resilience growth, while innovative eastern provinces have made significant progress by leveraging the synergy of technology and digitalization.

Agricultural resilience improves through multiple pathways rather than a single optimal model. Configuration analysis identifies three equally effective paths: “digitalization-technology” synergy, “digitalization-technology-financial support” enhancement, and “digitalization-technology-climate resources” synergy. These findings confirm that the construction of resilience depends on the alignment of core driving factors and regional endowments. Notably, digital inclusive finance plays a central role as a common core element across all paths, expanding financing channels and reducing the costs of technology adoption. Furthermore, there are significant path dependencies between grain-producing and non-grain-producing regions. The former relies on the deep integration of technology and digitalization to ensure production capacity, while the latter requires a combination of financial and technological support to overcome resource constraints.

In conclusion, the key to shifting China’s agricultural resilience from “engineering resilience” to “evolutionary resilience” lies in constructing a policy system that can stimulate the synergy of multiple factors. Future efforts should focus on enhancing the inclusiveness and penetration of digital finance. In addition, regional governance strategies should be implemented to guide the optimal allocation of technology, capital, and digital platforms according to regional endowments, systematically fostering the adaptability, learning, and transformation capabilities of agriculture.

Policy implications

This study provides diverse solutions for improving agricultural resilience, with key policy implications:

(1) Focus on water resource management and soil improvement as the primary means to enhance resilience in major grain-producing regions. The research results show that multiple pathways in major grain-producing regions such as Shandong, Henan, and other provinces, repeatedly highlight the high-frequency combination of “water-saving irrigation + straw returning.” Specifically, during the construction of high-standard farmland, intelligent irrigation and soil health improvement plans should be implemented concurrently. The full “collect-transport-return-measure” chain for straw management should be improved, with integrated applications for field sensing, variable irrigation, and yield/moisture monitoring to stabilize output and income during climate shocks.

(2) Shift from “engineering resilience” to “evolutionary resilience” and accelerate the modernization transformation of traditional agriculture. The research results show that while medium-tier resilience expands, the medium-high/high tiers contract, with insufficient resilience improvement in traditional agricultural provinces such as Hebei, Liaoning, and Shandong. Policy combinations should support ecological agriculture, climate-resilient crops, agro-processing, cold chains, and resilient supply chains that combine orders and futures contracts. This should facilitate the transition from a single grain-dominated system to a diversified “grain—economy—feed—processing” model, enhancing the ability to adapt and reconstruct in response to complex shocks.

(3) Promote cross-regional knowledge sharing and flow of resources to reduce spatial imbalances. The research results show that regions with medium-high resilience, such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang, perform steadily, while many areas in the northeast and northwest fall into low or medium-low resilience tiers, showing significant spatial differentiation. Specifically, a national-level resilience technology demonstration corridor and an “East technology to West, South capital to North” cooperation mechanism should be established. Through “contract diffusion + outcome sharing,” leading enterprises and cooperatives should be encouraged to export technologies, management practices, and service models to low-resilience regions, while setting up replicable standardized operating packages to accelerate convergence.

(4) Promote the collaborative diffusion of “Digital Finance + Key CSA Technologies.” The research findings show that high-resilience pathways H1/H2/H3 are centered around digital financial inclusion, water-saving irrigation, and straw returning (with no-tillage technology as an important supplement), while the absence of these elements in L1/L2 leads to low resilience. Specifically, an integrated “tech-finance-service” package (including technology lists, interest-subsidized loans/financing leases, and doorstep services) should be established at the county level. This package should link equipment procurement, operation and maintenance, and digital agricultural service platforms, creating a closed-loop diffusion mechanism from financing, procurement, installation, to monitoring and evaluation.

(5) Shift fiscal spending from a “scattergun approach” to a “technology-finance” combination linked to performance outcomes. The research results show that fiscal support combined with key technologies (H2a/H2b and N1/N2) can significantly improve agricultural resilience, while L2 indicates that fiscal expenditure alone is insufficient to translate into resilience. Additionally, G2 reflects the dependency on fiscal support. Specifically, subsidies should be tied to performance indicators such as the “technology adoption rate, water-saving intensity, soil organic matter improvement, and emissions reduction.” A results-based payment (RBF) approach should be implemented with inter-provincial differentiated allocation, directing funds primarily to operators who adopt water-saving irrigation, straw returning, and no-tillage practices.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adegbite OO, Machethe CL (2020) Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria: An untapped potential for sustainable development. World Devel 127: 104755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104755

Adesipo A, Fadeyi O, Kuca K, Krejcar O, Maresova P, SelamatM A, Adenola (2020) Smart and Climate-Smart Agricultural Trends as Core Aspects of Smart Village Functions. Sensors 20:5977. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20215977

Adhikari J, Timsina J, Khadka SR, GhaleH Y, Ojha (2021) COVID-19 impacts on agriculture and food systems in Nepal: Implications for SDGs. Agric Syst 186: 102990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102990

Adonadaga MG, Ampadu B, AmpofoF S, Adiali (2022) Climate Change Adaptation Strategies Towards Reducing Vulnerability to Drought in Northern Ghana. Eur J Environ Earth Sci 3:1–6. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejgeo.2022.3.4.294

Amadu FO, McNamaraD PE, Miller C (2020) Yield effects of climate-smart agriculture aid investment in southern Malawi. Food Policy 92: 101869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101869

Anderegg WRL, Konings AG, Trugman AT, Yu K, Bowling DR, Gabbitas R, Karp DS, Pacala S, Sperry JS, SulmanN BN, Zenes (2018) Hydraulic diversity of forests regulates ecosystem resilience during drought. Nature 561:538–541. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0539-7

Andersen MA, Alston JM, Pardey PG, Smith A (2018) A Century of U.S. Farm Productivity Growth: A Surge Then a Slowdown. Am J Agric Econ 100:1072–1090. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aay023

Anderson R, BayerD PE, Edwards (2020) Climate change and the need for agricultural adaptation. Curr Opin Plant Biol 56:197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2019.12.006

Bakker YW, de KoningJ J, van Tatenhove (2019) Resilience and social capital: The engagement of fisheries communities in marine spatial planning. Mar Policy 99:132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.032

Belay A, Mirzabaev A, Recha JW, Oludhe C, Osano PM, Berhane Z, Olaka LA, Tegegne YT, Demissie T, MutsamiD C, Solomon (2024) Does climate-smart agriculture improve household income and food security? Evidence from Southern Ethiopia. Environ, Dev Sustain 26:16711–16738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03307-9

Berry R, ViganiJ M, Urquhart (2022) Economic resilience of agriculture in England and Wales: a spatial analysis. J Maps 18:70–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2022.2072242

Beynon MJ, JonesD P, Pickernell (2020) Country-level entrepreneurial attitudes and activity through the years: A panel data analysis using fsQCA. J Bus Res 115:443–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.021

Bhatnagar S, Chaudhary R, Sharma S, Janjhua Y, Thakur P, Sharma P, Keprate A (2024) Exploring the dynamics of climate-smart agricultural practices for sustainable resilience in a changing climate. Environ Sustainability Indic 24: 100535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2024.100535

Birthal PS, Hazrana J (2019) Crop diversification and resilience of agriculture to climatic shocks: Evidence from India. Agric Syst 173:345–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.03.005

Boehlje M (1999) Structural Changes in the Agricultural Industries: How Do We Measure, Analyze and Understand Them? Am J Agric Econ 81:1028–1041. https://doi.org/10.2307/1244080

Bowles TM, Mooshammer M, Socolar Y, Calderón F, Cavigelli MA, Culman SW, Deen W, Drury CF, Garcia y Garcia A, Gaudin ACM, Harkcom WS, Lehman RM, Osborne SL, Robertson GP, Salerno J, Schmer MR, StrockA J, Grandy S (2020) Long-Term Evidence Shows that Crop-Rotation Diversification Increases Agricultural Resilience to Adverse Growing Conditions in North America. One Earth 2:284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.02.007

Bullock JM, Dhanjal-Adams KL, Milne A, Oliver TH, Todman LC, WhitmoreR AP, Pywell F (2017) Resilience and food security: rethinking an ecological concept. J Ecol 105:880–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12791

Burchfield EK, de la Poterie AT (2018) Determinants of crop diversification in rice-dominated Sri Lankan agricultural systems. J Rural Stud 61:206–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.05.010

Canello JF, Vidoli (2020)Investigating space-time patterns of regional industrial resilience through a micro-level approach: An application to the Italian wine industry. J Reg Sci 60:653–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12480

Cao A, Guo L, Houjian L (2022) How does land renting-in affect chemical fertilizer use? The mediating role of land scale and land fragmentation. J Clean Prod 379: 134791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134791

Cesco S, Sambo P, Borin M, Basso B, Orzes G, Mazzetto F (2023) Smart agriculture and digital twins: Applications and challenges in a vision of sustainability. Eur J Agron 146: 126809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2023.126809