Abstract

Accurate segmentation and detection of pulmonary nodules from computed tomography (CT) scans are critical for early lung cancer diagnosis but are hindered by the high diversity of nodule characteristics and the limitations of existing deep learning models. Conventional convolutional neural networks struggle with long-range context, while Transformers can neglect fine local details. We present GLANCE (Continuous Global-Local Exchange with Consensus Fusion), a novel dual-stream architecture designed to overcome these limitations. GLANCE features two parallel, co-evolving branches: a global context transformer to model long-range dependencies and a multi-receptive grouped atrous mixer to capture fine-grained local details. The core innovation is the cross-scale consensus fusion mechanism, which continuously integrates these complementary feature streams at every hierarchical scale, preventing representational clashes and promoting synergistic learning. A dual-head pyramid refinement decoder leverages these fused features to perform simultaneous nodule segmentation and center heatmap detection. Validated on four public benchmarks (LIDC-IDRI, LNDb, LUNA16, and Tianchi), GLANCE establishes a new state-of-the-art in both segmentation and detection. An extensive ablation study confirms that each architectural component, particularly the continuous fusion strategy, is critical to its superior performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

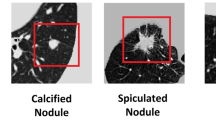

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, and early diagnosis through low-dose computed tomography (CT) significantly improves patient outcomes1. Pulmonary nodules, which are small focal lesions in the lung parenchyma, are often the earliest radiographic sign of lung cancer. Accurate segmentation of these nodules in CT scans is thus critical for early lung cancer screening and intervention. However, automated nodule segmentation remains a challenging task due to several technical factors. First, nodules exhibit high diversity in size, shape, and texture—they can range from tiny ground glass opacities to larger solid masses, and may appear in different anatomical locations, including morphologies that are subtle or obscured by surrounding structures2. Such variability means a segmentation model must capture both fine details and broad context. Additionally, many nodules have low contrast or ambiguous boundaries, making them difficult to distinguish from normal lung anatomy. Small nodules in particular can closely resemble blood vessels or other tissues, so reliable identification often requires contextual reasoning over a larger region3.

Another major challenge is class imbalance and scale disparity: nodules typically occupy only a minute fraction of the CT volume, whereas the vast majority of voxels belong to background lung tissue. This imbalance can bias learning and cause standard models to miss the tiny nodular targets. Moreover, the small physical size of many nodules (often just a few millimeters in diameter) demands extremely precise boundary localization4. In summary, an effective pulmonary nodule segmentation approach must achieve robust multi-scale representation—capturing subtle edge details while also incorporating global contextual information—and must handle the inherent data imbalance and noise in clinical CT scans.

Convolutional neural network (CNN) based architectures (such as U-Net and its variants) have become the de facto standard for medical image segmentation, including lung nodule segmentation, due to their ability to learn rich feature hierarchies. Yet, conventional CNN encoders have limitations in this application. Their intrinsic receptive field is finite, which can hinder the modeling of long-range dependencies needed to discern nodules from surrounding tissue. Consequently, pure CNN models may struggle with very small or highly subtle nodules that require integration of global cues. On the other hand, transformer-based architectures have recently been explored to overcome the locality bias of CNNs by leveraging self-attention for global context capture. Transformers can inherently model long-range relationships without the receptive field constraints of CNNs, but they introduce other drawbacks: their high computational cost and need for large training datasets can be prohibitive, and naive transformer models may over-emphasize global structure at the expense of fine local detail3. In practice, neither pure CNN nor pure transformer solutions alone have fully solved the nodule segmentation problem, especially under limited data and the requirement for both precision and contextual awareness.

Many existing hybrid models employ sequential or late-stage fusion strategies, where features from convolutional and transformer blocks are either alternated or combined only deep within the network.5 This approach can create a “representational clash" by forcing the fusion of disparate feature types that have been learned independently. Such abrupt integration can disrupt the stable propagation of information, leading to optimization difficulties and degraded performance. The central problem is not merely the inclusion of both global and local feature extractors, but the development of a principled framework through which these two complementary representations can harmoniously and continuously inform one another throughout the feature extraction hierarchy.

Recent years have seen a proliferation of deep learning models for lung nodule segmentation, with many efforts devoted to improving the U-Net style encoder-decoder backbone. A central theme is enhancing multi-scale representation and feature fusion to cope with nodules of varying sizes and appearances. For example, Selvadass et al. introduced SAtUNet, which applies a series of atrous (dilated) convolution modules at multiple encoder stages to capture multi-scale context, yielding improved performance on small nodules6,7,8. Other works have proposed deeper and more recursive architectures to enrich feature fusion across scales—one such approach is to employ nested UNet structures with residual connections, as in the channel residual UNet model reported by Wu et al., which better preserves fine details through iterative feature refinement9. In addition to purely convolutional designs, some researchers have explored multi-branch and multi-encoder networks. Xu et al. presented a dual encoding fusion model to handle atypical nodules, wherein two parallel encoders extract complementary features that are later merged for segmentation10. Similarly, incorporating external knowledge or alternate feature streams has shown benefits: Jiang et al.2 developed a dual-branch architecture that integrates a prior feature extraction branch (infusing radiological prior knowledge) alongside a standard image-based branch, significantly improving segmentation of subtle, adherent, or otherwise challenging nodules. These strategies highlight the importance of multi-scale and multi-modal feature learning in advancing pulmonary nodule segmentation beyond the basic U-Net.

The use of attention techniques has become widespread in medical segmentation to focus on critical regions and features. In the context of lung nodules, attention-based modules help the model discriminate nodules from complex backgrounds. Early examples include attention gates that learn to emphasize salient node regions while suppressing irrelevant features11. More recent architectures integrate channel-wise and spatial attention to refine feature maps. Yang et al. proposed an uncertainty-guided segmentation model that incorporates a Squeeze and Excitation attention block to adaptively highlight informative feature channels, guided by model uncertainty to target ambiguous nodules12. Ma et al. likewise improved the V-Net architecture by adding a pixel threshold separation module (to enhance features under different intensity ranges) together with 3D channel and spatial attention modules, which encouraged the network to focus on important nodule regions and boundaries4. Beyond these, novel attention blocks such as Coordinate Attention13 have been adopted in nodule segmentation models to better capture long-range dependencies while preserving positional information. By embedding attention mechanisms at various layers (e.g., in skip connections or decoder blocks), these methods boost sensitivity to small or low contrast nodules and improve the precision of nodule boundaries.

Motivated by the success of Vision Transformers, several works have investigated hybrid encoders that combine CNN and self-attention mechanisms for nodule segmentation. The rationale is to leverage CNNs for local detail extraction and transformers for global context understanding. One notable example is the Swin-UNet model by Ma et al., which fuses a sliding window transformer block (based on the Swin Transformer) into the U-Net framework14. This hybrid design allows the network to capture long-range contextual relationships in the CT while maintaining strong localization ability. Similarly, other studies have inserted transformer modules at specific stages of a convolutional network to enhance its receptive field. For instance, inserting a self-attention block at the encoder bottleneck can propagate global information through the network, improving segmentation in complex cases15. Overall, CNN-Transformer hybrids represent a promising direction, although they must be carefully designed to balance computational cost with segmentation accuracy.

It is important to differentiate this architectural challenge from the concurrent challenge of data scarcity. While architectural design seeks to optimize feature representation (as we address), orthogonal approaches like semi-supervised learning (SSL) aim to improve data efficiency by leveraging unlabeled scans, often through techniques like knowledge distillation16. Such learning paradigms are complementary to model design; an effective architecture should, in principle, perform well in a fully-supervised setting while also serving as a robust backbone for data-efficient training. This study, therefore, focuses on the fundamental architectural problem: establishing a principled framework for global-local feature exchange. We posit that solving this representational bottleneck is a prerequisite for, and will ultimately enhance, future investigations into data-efficient learning strategies.

We propose GLANCE (Continuous Global-Local Exchange with Consensus Fusion), a framework designed to create synergy between global and local features. Our model features parallel global and local branches that continuously exchange information at multiple scales, guided by a consensus fusion mechanism that leverages their complementary strengths. We validate our approach on four public benchmarks (LIDC-IDRI, LNDb, LUNA16, and Tianchi), where GLANCE establishes a new state-of-the-art in both segmentation and detection. The results demonstrate a powerful synergy over single-task baselines, and an ablation study confirms the critical contribution of each architectural component. The following sections detail the related work, methodology, and present the full empirical evidence supporting GLANCE’s superior performance.

Results

This section presents a comprehensive empirical validation of the proposed GLANCE architecture. The quantitative evaluation is designed to rigorously assess two central hypotheses: first, that the multi-task learning framework for joint detection and segmentation yields synergistic performance benefits over specialized single-task models; and second, that the GLANCE model establishes a new state-of-the-art (SOTA) benchmark for both lung nodule segmentation and detection across multiple public datasets. The evidence supporting these claims is detailed in the subsequent subsections, with Table 1 providing a direct comparison against single-task baselines, and Table 2 and Table 3 offering an exhaustive comparison against recent SOTA methods. These results provide definitive validation of GLANCE’s novel design principles, particularly its dual-stream context encoder and continuous cross-scale consensus fusion (CSCF), demonstrating their efficacy in addressing the challenges of automated pulmonary nodule analysis.

Overall detection and segmentation performance

To isolate and quantify the benefits of our multi-task learning strategy, we first compared the performance of the unified GLANCE model against two specialized baselines: a Detection Only model and a Segmentation-Only model. The results, summarized in Table 1, provide unequivocal evidence that the joint optimization of both tasks leads to significant improvements in each domain, highlighting a powerful synergistic relationship.

The most profound advantage of the multi-task approach is observed in the detection performance, particularly in the high specificity regime. The Detection-Only baseline achieves a sensitivity of 80.2% at a stringent operating point of 1 false positive per scan (FP/s). In stark contrast, our multi-task GLANCE model reaches a sensitivity of 95.7% at the same 1 FP/s threshold, marking a remarkable absolute improvement of 15.5 percentage points. This substantial gain underscores the model’s enhanced ability to identify true nodules with high confidence. The operating point of 1 FP/s is clinically critical and technically demanding, as it requires the model to assign higher confidence scores to true positive nodules than to nearly all other structures in an entire CT volume. A standard detection model often struggles with ambiguous findings, such as vessel cross sections or pleural attachments, which can be mistaken for nodules. By incorporating a segmentation objective, the shared feature encoder is compelled to learn not only localization cues but also rich morphological features related to nodule shape, texture, and boundary definition. These segmentation-aware features provide the detection head with a more discriminative representation, enabling it to better differentiate true, well-defined nodules from morphologically inconsistent mimics. This reduces ambiguity and boosts the confidence scores for true positives, leading directly to the dramatic increase in sensitivity at low false positive rates. While the improvement at 4 FP/s is more modest (from 92.5% to 94.8%), the overall enhancement is captured by the competition performance metric (CPM), which improves from 90.1 to 92.1, confirming a holistically superior detection capability.

Simultaneously, the segmentation accuracy also benefits from the multi-task framework. The Segmentation-Only baseline achieves a strong Dice coefficient of 95.2%. Our unified GLANCE model surpasses this, attaining a Dice score of 96.4%. Although the absolute increase of 1.2 points is numerically smaller than the gains seen in detection, it represents a significant improvement in a high-performance domain where further gains are notoriously difficult to achieve. This enhancement can be attributed to the detection task acting as a potent spatial regularizer. As detailed in the methodology, the detection head is trained to predict a center heatmap, which explicitly forces the network to learn the concept of a nodule’s centroid. This localization objective imposes a strong spatial constraint on the segmentation output, penalizing masks that are diffuse or deviate significantly from the lesion’s core. Consequently, the model is encouraged to produce more compact, topologically sound segmentations that are accurately centered on the nodule. This “focusing" effect improves adherence to true nodule boundaries and minimizes pixel-level inaccuracies, particularly for lesions with indistinct margins, culminating in a higher Dice score.

SOTA comparison for lung nodule segmentation and detection

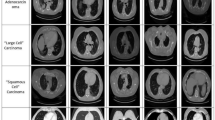

To establish the performance of GLANCE relative to the current state-of-the-art, we conducted an extensive comparative analysis against a wide range of recently published models on four standard public benchmarks. The evaluation was performed separately for segmentation (on LIDC-IDRI and LNDb) and detection (on LUNA16 and Tianchi), with the comprehensive results presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Fig. 1 displays our model along with visual segmentation and detection results from recent SOTA models. The findings from this benchmarking exercise consistently position GLANCE as a new leading method in both domains.

For each case, we show the original image, ground truth, ours, and a series of baselines arranged left-to-right in progressively worse visual quality relative to (c)(k)ours. Detection baselines: (d)LN-DETR, (e)NDLA, (f)AWEU-Net, (g)CSE-GAN, (h)EHO-Deep CNN, segmentation baselines: (l)UnetTransCNN, (m)BRAU-Net++, (n)CT-UFormer, (o)UNETR++, (p)Improved V-Net; Our method yields sharper boundaries and fewer false positives/negatives, with competing methods exhibiting increasing boundary erosion, missed lesions, and spurious responses to the right.

SOTA Segmentation Performance: The segmentation capabilities of GLANCE were benchmarked on the LIDC-IDRI and LNDb datasets, with results detailed in Table 2. On the widely used LIDC-IDRI dataset, GLANCE achieves a Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) of 95.5%, an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 91.4%, a sensitivity of 96.0%, and a 95% Hausdorff Distance (HD95) of 0.7 mm. This performance represents a new state-of-the-art, outperforming all other listed methods across all four evaluation metrics. While the model shows a clear lead in overlap-based metrics over strong competitors like CT-UFormer17 (94.0% DSC) and Wavelet U-Net++18 (93.7% DSC), its most significant advantage lies in the boundary-based HD95 metric. The HD 95 score is particularly sensitive to major boundary discrepancies and serves as a crucial indicator of a model’s ability to accurately delineate complex shapes. GLANCE’s HD95 of 0.7 mm constitutes a 30% reduction in maximum boundary error compared to the next best models, which achieve 1.0 mm. This substantial improvement in boundary fidelity is a direct consequence of GLANCE’s core architectural innovations. The Multi-Receptive Grouped Atrous Mixer (MRGAM) is specifically designed to capture fine-scale boundary and texture details, while the Global Context Transformer (GCT) provides the long-range contextual information necessary to distinguish the nodule from adjacent structures like vessels or the pleura. The continuous integration of these complementary feature streams via the cross-scale consensus fusion (CSCF) mechanism ensures that this dual understanding of local detail and global context is maintained throughout the network, resulting in exceptionally precise boundary localization.

To assess the model’s generalization capabilities, we evaluated its performance on the LNDb dataset, which originates from a different clinical environment with distinct scanners and acquisition protocols. As shown in Table 2, many competing models exhibit a discernible drop in performance when transitioning from LIDC-IDRI to LNDb. For example, UnetTransCNN19 sees its DSC fall from 92.6% to 90.7%, and Improved V-Net4 drops from 85.7% to 81.1%. In contrast, GLANCE demonstrates remarkable robustness, with its DSC remaining exceptionally stable at 95.3% (compared to 95.5% on LIDC-IDRI). This consistency indicates that our model has learned more fundamental and invariant representations of pulmonary nodules, rather than overfitting to the specific characteristics of a single dataset. The global context provided by the GCT likely contributes to this robustness by making the model less sensitive to variations in image contrast and noise levels. This proven ability to generalize across diverse data sources is a critical attribute for any model intended for real-world clinical deployment.

SOTA Detection Performance: The detection performance of GLANCE was rigorously evaluated on the LUNA16 and Tianchi datasets, with comparative results presented in Table 3. On the LUNA16 benchmark, GLANCE achieves a precision of 92.3%, a recall of 94.1%, and an F1-score of 93.2. While its F1-score is closely matched by models such as NDLA20 (91.3) and Santone et al.21 (91.3), a deeper analysis of the underlying metrics reveals a superior clinical profile. GLANCE’s recall of 94.1% is the highest among all competing methods, significantly surpassing that of other top-performing models like NDLA (90.7%). In the context of cancer screening, maximizing recall (sensitivity) is paramount to ensure that no potentially malignant lesions are missed. Critically, GLANCE achieves this best-in-class recall without compromising precision, which remains highly competitive. This ability to break the typical trade-off between recall and precision stems from its multi-task design. The concurrently trained segmentation head implicitly acts as a powerful filter; a detection candidate is not only evaluated based on localization signals but also on its ability to be segmented into a morphologically plausible nodule. This helps the model reject anatomically inconsistent false positives, thereby maintaining high precision while identifying more true nodules than any other model.

The superior performance and generalization of GLANCE are further confirmed on the Tianchi dataset, a large-scale dataset created for a competitive challenge. On this benchmark, GLANCE’s dominance is even more pronounced. It achieves a precision of 95.0%, a recall of 93.6%, and an F1-score of 94.3. This F1-score is more than two full points higher than the next best competitor, NDLA20, at 90.8. The widening performance gap on this more heterogeneous dataset reinforces the conclusions drawn from the segmentation analysis on LNDb. GLANCE’s robust architecture, which effectively integrates global anatomical context with fine-grained local analysis, proves to be highly adaptable to variations in data sources and annotation protocols. This decisive victory on a second, distinct detection benchmark provides strong evidence that the model’s high performance is not an artifact of a single dataset but a reflection of a fundamentally more powerful and generalizable approach to nodule detection.

Ablation study

To quantify the contribution of each component in GLANCE, we ablated the Global Context Transformer (GCT), the multi-receptive grouped atrous mixer (MRGAM), and the CSCF on LIDC-IDRI. Table 4 summarizes the results.

We start from a baseline U-Net without any of the three modules (w/o GCT & w/o MRGAM & w/o CSCF), which reaches 79.0% Dice and 65.3% IoU. Removing the GCT from the full model yields the largest single module drop-down to 80.0% Dice (−15.2 points vs. 95.2%) and 66.7% IoU, highlighting the importance of long-range context for disambiguating nodules from vessels and airways. Ablating MRGAM reduces performance to 82.5% Dice (−12.7 points) and 70.2% IoU, confirming the role of multi-receptive atrous mixing in capturing fine boundaries and textures. Disabling CSCF (no cross-scale fusion) similarly degrades accuracy to 82.0% Dice (−13.2 points) and 69.5% IoU, showing that continuous cross-scale integration is crucial rather than deferring fusion to the decoder.

CSCF is most effective when fusing complementary signals. With two local streams but no GCT (w/o GCT, w/ CSCF), performance is only 80.4% Dice/67.2% IoU, a marginal +1.4 Dice over the baseline, indicating limited benefit from fusing redundant features. Single-stream variants without CSCF also underperform: MRGAM only (w/o GCT & w/o CSCF) achieves 80.3% Dice/67.1% IoU, and GCT only (w/o MRGAM & w/o CSCF) reaches 81.0%/68.1%; both are better than the baseline but far from the full model. Simply doubling plain encoders (w/o GCT & w/o MRGAM) gives 79.5% Dice/66.0% IoU, showing that gains do not come from model width alone.

Overall, the full GLANCE integrating global context (GCT) and local detail (MRGAM) through continuous crossscale fusion (CSCF), achieves 95.2% Dice and 90.8% IoU, substantially outperforming all ablations and evidencing strong component complementarity.

To test whether component synergies generalize beyond LIDC-IDRI segmentation, we replicated the key ablations on detection for LUNA16 and Tianchi (Table 5). Removing GCT, MRGAM, or CSCF reduces F1 from 93.2%/94.3% to 83.7%/84.4% (−9.5/−9.9), 88.0%/86.8% (−5.2/−7.5), and 86.7%/85.3% (−6.5/−9.0), respectively; single-stream controls plateau near 82% F1, confirming that continuous fusion of complementary global and local cues is essential across tasks and datasets.

We further compared branch-weighting mechanisms inside MRGAM (Table 6): our Global+Local softmax gate achieved the best F1 (93.2%/94.3%), outperforming uniform mixing (90.9%/92.5%), Local-SE only (91.3%/93.0%), learned static scalars (91.1%/92.8%), 1 × 1-conv mixing (91.2%/92.9%), and a scaled dot-product attention-based weighting (91.2%/93.0%). These results demonstrate that the claimed GCT-MRGAM-CSCF synergy and our lightweight gating choice are robust on two external detection benchmarks.

Computational complexity and efficiency

We analyze parameter count, FLOPs, and memory for the main components of GLANCE—the Global Context Transformer (GCT), the Multi-Receptive Grouped Atrous Mixer (MRGAM), and CSCF—within the staged encoder-decoder used in this work (input H × W = 512 × 512, stride-2 downsampling per stage). Architectural details are as introduced in Section 4 and Figs. 3 and 4 (DiSCo, CSCF, PRD).

Let \(X\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{h\times w\times C}\) be the feature at a given stage, n = hw tokens, and d the token width. Grouped atrousk × k conv (MRGAM). FLOPs \(\approx 2\,h\,w\,\frac{{k}^{2}{C}_{in}{C}_{out}}{g}\), params \(=\frac{{k}^{2}{C}_{in}{C}_{out}}{g}\). With N parallel dilation branches {di} and context gating (SE), cost adds linearly in N plus a negligible SE MLP term \(\approx \frac{2{C}^{2}}{r}\) params/FLOPs per spatial location (reduction ratio r = 16 used in practice). Self-attention (GCT). For full attention at resolution (h, w): FLOPs ≈ 4nd2 + 2n2d (QKV projections and attention product) plus MLP ≈ 2nd2. To control cost, we (i) restrict full global attention to mid/low resolutions and (ii) use local windows or token downsampling at high resolutions (Sec. 4.2), yielding O(nM2d) with \(M\ll \sqrt{n}\). Consensus fusion (CSCF). One 1 × 1 convolution and a channel SE gate: FLOPs ≈ 2hwC2 (for 1 × 1) \(+\,\frac{2hw{C}^{2}}{r}\); params \(\approx {C}^{2}+\frac{2{C}^{2}}{r}\). CSCF is thus O(hwC2) with a small constant and adds < 3 − 5% FLOPs per stage in practice. Decoder (PRD). Two 3 × 3 convs per level with skip concat; standard UNet-style cost O(hwk2C2) dominated by early decoder stages.

(i) Early, high-resolution stages rely on MRGAM (linear in hw) instead of attention; (ii) full global attention is deferred to lower resolutions with fewer tokens; (iii) CSCF uses only 1 × 1 + SE gating; (iv) grouped atrous mixing keeps k2C2 small at high h, w by using groups g > 1. Together, these yield a dual-stream encoder whose cost is close to a single strong CNN/UNet++ backbone, while retaining global context.

Let FC denote the FLOPs of a single CNN-style stream at a stage, \({F}_{A}^{hi}\) the (windowed) attention FLOPs at high resolution (omitted in GLANCE), and \({F}_{A}^{low}\) the attention FLOPs at lower resolutions (kept). Then a naïve two-stream sum would be \({F}_{C}+{F}_{A}^{hi}+{F}_{A}^{low}\). Our design replaces \({F}_{A}^{hi}\) by an MRGAM mixer with cost \({\widetilde{F}}_{C}\ll {F}_{A}^{hi}\), so the dual-stream ratio is

Because \({F}_{A}^{low}\) is computed at \(\frac{1}{4}-\frac{1}{16}\) the resolution of the input and FCSCF is 1 × 1, the empirical overhead remains modest while conferring global context at the right scales.

To validate our choice of λdet in Equation (9), we performed a sensitivity analysis by varying its value within the previously mentioned [0.2, 0.5] range, while holding λseg constant at 1.0. The performance was evaluated on our validation set, with key results summarized in Table 7.

Discussion

The empirical results presented herein provide compelling evidence for the efficacy of the GLANCE architecture, establishing a new SOTA for both lung nodule segmentation and detection. Our central hypothesis that continuous, multi-scale fusion of complementary global and local features yields synergistic benefits is strongly supported by the ablation study. The full GLANCE model reached 95.2% Dice, whereas the removal of the GCT caused the most significant performance degradation, with the Dice score plummeting by 15.2 points to 80.0%, underscoring the critical role of long-range contextual information in disambiguating nodules from complex surrounding anatomy. Similarly, disabling the CSCF resulted in a sharp drop to 82.0% Dice, confirming that it is not merely the presence of dual feature streams, but their continuous, hierarchical exchange that unlocks the architecture’s full potential. The model’s superior boundary delineation, evidenced by a state-of-the-art 95% Hausdorff Distance of 0.7 mm on LIDC-IDRI, a 30% reduction in boundary error over the next-best competitor, can be directly attributed to the synergy between the GCT’s contextual awareness and the MRGAM’s proficiency in capturing fine-grained texture. Furthermore, the multi-task learning framework demonstrated a clear symbiotic relationship between segmentation and detection. The inclusion of a segmentation objective dramatically improved detection sensitivity at a clinically critical threshold of 1 false positive per scan, increasing it from 80.2% to 95.7%. This suggests the segmentation task acts as a potent morphological regularizer, compelling the shared encoder to learn features that help reject anatomically implausible false positives. Conversely, the detection task’s center-heatmap prediction provides a strong spatial prior that refines segmentation boundaries, boosting the Dice score from 95.2% to 96.4%. This synergy, combined with the model’s demonstrated robustness across datasets with different scanners and annotation protocols, maintaining a stable Dice score of 95.5% on LIDC-IDRI and 95.3% on LNDb, underscores the potential of the GLANCE framework as a generalizable and clinically relevant tool for automated pulmonary nodule analysis.

Methods

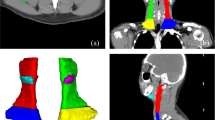

GLANCE (Continuous Global-Local Exchange with Consensus Fusion), shown in Fig. 2 is a sophisticated, hybrid encoder-decoder architecture meticulously engineered for high fidelity, arbitrary-oriented object detection. This architecture is conceived as a direct response to the inherent limitations of prevailing computer vision paradigms. While traditional CNNs excel at extracting rich, localized feature hierarchies, their effectiveness is constrained by a fundamentally local receptive field, which impedes the modeling of long-range spatial dependencies. Conversely, Vision Transformers (ViTs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in capturing global context through self-attention mechanisms, yet standard implementations can suffer from a loss of fine-grained local detail and encounter training instabilities, particularly in very deep configurations.

GLANCE is founded upon a set of core principles designed to synergize the strengths of both approaches while mitigating their respective weaknesses. The architectural philosophy is rooted in a modular, problem-driven composition, where each component is selected to address a specific challenge within the complex object detection pipeline. The foundational principles are as follows: Dual-Stream Context Encoder (DiSCo): two co-evolving streams process the image at matched resolutions:(i) a Global Context Transformer (GCT) that models long-range dependencies; (ii) a Multi-Receptive Grouped Atrous Mixer (MRGAM) that captures fine-scale texture and boundaries over multiple receptive fields. Cross-Scale Consensus Fusion (CSCF): a lightweight integrator that fuses the global and local streams at every scale, ensuring uninterrupted propagation and exchange of global and local evidence throughout the network. Pyramid Refinement Decoder (PRD): an upsampling pathway with attention-gated skips from CSCF outputs, followed by a dual head that produces (i) a nodule probability map and (ii) a center heatmap for detection.

The dual-stream design with continuous global-local exchange addresses the instability observed when convolutional and transformer features are forced to alternate or to act on mismatched inputs; prior work shows that alternating stacks can disrupt the stable transmission of global and local cues, degrade training, and reduce accuracy. Our fusion before each downsampling strategy explicitly avoids that pitfall by making the two streams mutually conditioning and continuously fused across scales.

Notation and preprocessing

Let a lung CT slice be \(I\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W}\). We apply lung windowing ([−1000, 400]HU). This Hounsfield Unit (HU) range is a standard in clinical radiology, selected to optimize the visual contrast of lung parenchyma (approx. −700 HU) and soft-tissue nodules (approx. −100 to +100 HU) while clipping signals from dense bone (>400 HU) and external air (<−1000 HU) that are irrelevant to this task. We clamp intensities to this interval and linearly rescale to [0, 1].

To increase the proportion of informative pixels and stabilize learning by removing large, feature-sparse regions, we optionally extract a coarse lung mask and crop to its bounding box. Slices are then resized to a fixed working resolution (H = W = 512). This 512 × 512 resolution is selected as a standard, empirically-validated trade-off: it preserves sufficient spatial detail to resolve small micronodules while remaining computationally tractable for deep learning on modern GPU hardware, balancing fidelity with memory constraints. During training, we sample full slices or patches that include at least one positive nodule mask when available (hard-example mining).

Dual-Stream Context Encoder (DiSCo)

DiSCo shown in Fig. 3 produces scale-aligned feature pyramids \(\{{F}^{(1)},\ldots ,{F}^{(L)}\}\) for both global and local streams. Each stage downsamples by a factor of 2 (spatial) and increases channels.

Global Context Transformer (GCT): Overlapping patch embedding: Overlapping patch embedding. We embed I via a shallow convolution E (kernel 4 × 4, stride 4) to produce \({X}^{(1)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{\frac{H}{4}\times \frac{W}{4}\times {C}_{1}}\). Overlapping convolutional embeddings preserve local structure and stabilize early tokenization while serving the transformer with context-rich tokens, a practice shown to be effective in hybrid biomedical segmentation.

Self-attention block: At a generic stage k, flatten X(k) to nk tokens of width dk. Multi-head self-attention (MHSA) is

A position embedding is added at the first transformer stage to retain spatial relations. After MHA, we apply a two-layer MLP with GeLU, with pre-norm and residual connections. To respect computational economy at high resolutions, we restrict full global attention to moderate/low-resolution stages and use local windows or token-downsampling early; replacing early global attention with a specialized convolutional mixer is both effective and efficient when token counts are large. GCT outputs a pyramid \({\{{F}_{g}^{(k)}\}}_{k=1}^{L}\) (global stream).

Multi-Receptive Grouped Atrous Mixer (MRGAM):

Motivation and design: Grouped atrous (dilated) 3 × 3 convolutions at different dilation rates capture multi-scale context while keeping parameters and FLOPs modest. Using multiple grouped atrous branches in parallel has been shown to fuse complementary receptive fields effectively and to reduce computational burden compared with dense convolutions or attention at the same resolution.

Given \({X}^{(k)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{h\times w\times C}\), MRGAM applies N parallel grouped atrous convolutions \({\{{{\mathcal{C}}}_{{d}_{i},g}\}}_{i=1}^{N}\) with dilation \(\{{d}_{i}\}\) and group size g, followed by a residual blend:

where σ is ReLU, and αi are adaptive branch weights computed by a context gate that conditions on both streams (details below). A practical triplet is \(\{{d}_{i}\}=\{1,3,5\}\) with moderate grouping, balancing detail and context.

Complexity. For feature size h × w and kernel k × k, the attention cost grows as \({\mathcal{O}}({(hw)}^{2})\) in token length, whereas grouped atrous mixing costs \({\mathcal{O}}(\frac{hw{k}^{2}{C}^{2}}{g})\) and scales linearly in spatial size; at early stages (large hw), this makes MRGAM a principled mixer.

Context-gated weighting. To let global evidence steer local receptive field selection, we obtain αi via a squeeze excite gate:

with global average pooling (GAP), concatenation ∥, MLP \(({W}_{1},{W}_{2})\), and ϕ = ReLU. Intuitively, when the global stream indicates vessel-like linearity, the gate can upweight larger dilations to better encompass elongated context; for isolated spherical patterns, it prefers d = 1. MRGAM produces \({\{{F}_{\ell }^{(k)}\}}_{k=1}^{L}\) (local stream).

Algorithm 1

Global Context Transformer (GCT) Stage

1: procedure GCT-StageFin, k, PE

2: Input:Fin (Input feature map from previous stage, or image I for k = 1).

3: Input:k (Current stage index).

4: Input: PE (Positional Embedding, used only for k = 1).

5: Output:\({F}_{g}^{(k)}\) (Global context feature map for stage k).

6: ⊳ Overlapping patch embedding and downsampling

7: X(k) ← ConvEmbedk(Fin) ⊳ e.g., Conv(kernel=4, stride=4) for k = 1

8: if k = 1 then

9: X(k) ← X(k) + PE ⊳ Add positional embedding at the first stage

10: end if

11: ⊳ Flatten feature map to a sequence of tokens

12: T ← Flatten(X(k))

13: ⊳ Transformer Block with Pre-Norm

14: \(T{\prime} \leftarrow LayerNorm(T)\)

15: \(T{\prime} \leftarrow MHSA(T{\prime} )\) ⊳ Multi-Head Self-Attention as in Eq. (1)

16: \(T\leftarrow T+T{\prime} \) ⊳ First residual connection

17: \(T{\prime} \leftarrow LayerNorm(T)\)

18: \(T{\prime} \leftarrow {MLP}_{GeLU}(T{\prime} )\) ⊳ Two-layer MLP with GeLU activation

19: \(T\leftarrow T+T{\prime} \) ⊳ Second residual connection

20: ⊳ Reshape tokens back to spatial feature map

21: \({F}_{g}^{(k)}\leftarrow ReshapeAs(T,{X}^{(k)})\)

22: return \({F}_{g}^{(k)}\)

23: end procedure

Cross-scale consensus fusion

At each scale k, CSCF shown in Fig. 4 synthesizes the two streams into a single consensus map \({F}_{c}^{(k)}\) and feeds it back as the input to the next stage mixers in both streams. This preserves continuous global-local transmission and avoids the alternate stacking contradiction highlighted in prior analyses of hybrid encoder-decoders.

We implement CSCF as a residual, channel aware fusion:

where \({\gamma }^{(k)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{C}\) is a channel gate from a squeeze excite on Z(k), and ⊙ denotes channel wise multiplication. The fused \({F}_{c}^{(k)}\) is shared as input to both the next GCT and MRGAM blocks, ensuring that each subsequent block operates on already fused features rather than being forced to extract global (resp. local) information from a purely local (resp. global) input. This parallel then fuse pattern matches empirical observations that continuous exchange and multi-scale fusion yield stable training and superior boundary accuracy in biomedical segmentation.

Algorithm 2

Multi-Receptive Grouped Atrous Mixer (MRGAM) Stage 1: procedure MRGAM-Stage\({X}^{(k)},{F}_{g}^{(k)},{\{{d}_{i}\}}_{i=1}^{N},g\)

2: Input:X(k) (Input local feature map for stage k).

3: Input:\({F}_{g}^{(k)}\) (Global context feature map from GCT at the same stagek).

4: Input:\({\{{d}_{i}\}}_{i=1}^{N}\) (Set of dilation rates, e.g., {1, 3, 5}).

5: Input:g (Group size for convolutions).

6: Output:\({F}_{\ell }^{(k)}\) (Local context feature map for stage k).

7: ⊳ Context-gated weighting based on both streams

8: vℓ ← GlobalAveragePooling(X(k)) ⊳ Squeeze local features

9: \({v}_{g}\leftarrow GlobalAveragePooling({F}_{g}^{(k)})\) ⊳ Squeeze global features

10: v ← Concatenate(vℓ, vg)

11: \(\alpha \leftarrow Softmax(MLP(v))\) ⊳ Compute adaptive branch weights as in Eq. (4)

12: ⊳ Apply parallel grouped atrous convolutions

13: Fmix ← 0

14: for i = 1 to N do

15: \({U}_{i}\leftarrow ReLU({{\mathcal{C}}}_{{d}_{i},g}({X}^{(k)}))\) ⊳ \({{\mathcal{C}}}_{{d}_{i},g}\) is a grouped conv with dilation di

16: Fmix ← Fmix + αiUi ⊳ Aggregate features with adaptive weights

17: end for

18: ⊳ Residual blend to produce the final local feature map

19: \({F}_{\ell }^{(k)}\leftarrow {X}^{(k)}+{F}_{mix}\) ⊳ As in Eq. (3)

20: return \({F}_{\ell }^{(k)}\)

21: end procedure

Pyramid refinement decoder (PRD) and dual heads

Starting from the bottleneck \({F}_{c}^{(L)}\), PRD shown in Fig. 4 upsamples (and detailed in Algorithm 3) by a factor of 2 per stage. At decoder stage k we concatenate the upsampled feature with the encoder’s consensus skip \({F}_{c}^{(k)}\), then refine via a residual block:

where \({\mathcal{R}}\) is two 3 × 3 conv-BN-ReLU units with a residual shortcut. Skips carry both global and local signals (already fused), a design that has been linked to improved contour fidelity in biomedical segmentation.

Segmentation head. A 1 × 1 convolution maps D(1) to logits \({\mathcal{S}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W};\widehat{Y}=\sigma ({\mathcal{S}})\in {[0,1]}^{H\times W}\) is the nodule probability.

Detection head. In parallel, a center heatmap head predicts \(\widehat{H}\in {[0,1]}^{H\times W}\) with peaks at nodule centroids. Ground truth heatmaps H are generated by placing a Gaussian of radius proportional to the nodule diameter at each annotated centroid. During inference, non-maximum suppression on \(\widehat{H}\) yields candidate detections, optionally filtered by the segmentation mask to suppress vascular false positives.

Algorithm 3

Pyramid Refinement Decoder (PRD) and Dual Heads

1: procedure PRD-Decode\({\{{F}_{c}^{(k)}\}}_{k=1}^{L}\)

2: Input:\({\{{F}_{c}^{(k)}\}}_{k=1}^{L}\) (Pyramid of fused encoder features from CSCF).

3: Output:\(\widehat{Y}\) (Nodule probability map), \(\widehat{H}\) (Center heatmap).

4: Define:\({\mathcal{R}}(\cdot )\) (Residual refinement block, e.g., 2x 3 × 3 Conv-BN-ReLU).

5: Define: Up( ⋅ ) (Upsampling operation, e.g., Transposed Conv or Bilinear).

6: Define:σ( ⋅ ) (Sigmoid activation function).

7: ⊳ Initialize decoder bottleneck

8: \({D}^{(L)}\leftarrow {F}_{c}^{(L)}\)

9: ⊳ Iterative upsampling and refinement loop

10: for k = L − 1 down to 1 do

11: Dup ← Up(D(k+1)) ⊳ Upsample previous decoder stage

12: \({S}_{k}\leftarrow {F}_{c}^{(k)}\) ⊳ Get encoder skip-connection at scale k

13: Dconcat ← Concatenate(Dup, Sk) ⊳ As in Eq. (6)

14: \({D}^{(k)}\leftarrow {\mathcal{R}}({D}_{concat})\) ⊳ Refine fused features

15: end for

16: ⊳ Final dual-head prediction from the highest resolution D(1)

17: \({\mathcal{S}}\leftarrow {Conv}_{1\times 1}({D}^{(1)})\) ⊳ Segmentation logits

18: \(\widehat{Y}\leftarrow \sigma ({\mathcal{S}})\) ⊳ Nodule probability map

19: \({{\mathcal{H}}}_{logits}\leftarrow {Conv}_{1\times 1}({D}^{(1)})\) ⊳ Detection logits (separate 1 × 1 conv)

20: \(\widehat{H}\leftarrow \sigma ({{\mathcal{H}}}_{logits})\) ⊳ Center heatmap

21: return \(\widehat{Y},\widehat{H}\)

22: end procedure

Pulmonary CT-specific adaptations

Small, variable-sized nodules and their frequent adjacency to vessels or pleura put conflicting demands on context and detail. GLANCE addresses these by design: Scale diversity. MRGAM’s parallel dilations {1, 3, 5} cover micronodules through larger lesions in one operation, with grouped kernels reducing parameter/FLOP growth at high spatial resolutions. Context disambiguation. GCT supplies long-range cues (lung position, vessel trajectories). Fusing streams before each downsampling preserves this context as features coarsen, combating the global/local alternation issue reported in hybrid stacks. Boundary precision. Decoder skips bring high-resolution consensus features into PRD, improving boundary accuracy of juxta-pleural nodules without sacrificing robustness.

Implementation and training details

All models were implemented using PyTorch and trained on NVIDIA A100 GPUs. We specify our hyperparameters as follows: we used the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-4, a weight decay of 0.05, and a batch size of 8. The learning rate was managed by a Cosine Annealing with Warm Restarts schedule with an initial cycle length (T0) of 20 epochs. To enhance model robustness and prevent overfitting, we applied standard data augmentations, including random rotations (±15 degrees), random scaling (±10%), and minor elastic deformations.

Given ground-truth mask Y ∈ {0, 1}H×W and center heatmap H ∈ [0, 1]H×W, we optimize a compound loss

Based on the sensitivity analysis detailed in Table 7, the weights for all reported results were finalized at λseg = 1.0 and λdet = 0.3.

Pairing Dice with BCE is a strong baseline in biomedical segmentation under class imbalance and is widely adopted in unified benchmarking.

Cosine Annealing with Warm Restarts Learning Rate Schedule: To guide the optimization process, a dynamic learning rate schedule known as Cosine Annealing with Warm Restarts is employed. This schedule has two key components: Cosine Annealing: Within a given cycle of epochs (e.g., T0 epochs), the learning rate starts at an initial maximum value and is smoothly decayed to a minimum value (often close to zero) following the shape of a cosine curve. This gradual, non-linear decay allows the optimizer to make large exploratory steps early in the cycle and then slowly fine tune the parameters as it approaches a minimum in the loss landscape. This smooth descent helps the model converge into broad, stable minima, which are associated with better generalization. Warm Restarts: At the end of each cycle (after T0 epochs), the learning rate is abruptly reset to its initial maximum value. The length of the subsequent cycle, Ti, can be kept the same or progressively increased (Ti = Ti−1 × Tmult These periodic “restarts" provide a mechanism for the optimizer to escape from sharp, suboptimal local minima that it may have converged to during the annealing phase. The sudden increase in the learning rate propels the optimizer to a different region of the loss landscape, allowing it to continue its search for a more globally optimal solution. Deep supervision: Auxiliary segmentation heads on intermediate decoder stages are supervised with downsampled masks using a reduced weight ( × 0.3), accelerating convergence and improving small object recall.

Datasets and annotations

The availability of high-quality annotated chest CT datasets has been crucial for advancing computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) of pulmonary nodules. In particular, three public datasets have become widely used benchmarks for lung nodule detection and analysis: the LIDC-IDRI dataset22, the LNDb dataset23, and the Tianchi lung nodule dataset24. Each of these datasets provides a different scope and annotation protocol, offering complementary resources for developing and validating nodule detection algorithms. We provide here a description of each dataset and a comparative summary of their characteristics (Table 8).

LIDC-IDRI dataset: The Lung Image Database Consortium and Image Database Resource Initiative (LIDC-IDRI) dataset is a landmark collection of thoracic CT scans with comprehensive lesion annotations22. It contains 1018 CT scans from ~1010 patients, acquired from a multi-institutional effort primarily in the United States. Each scan was independently reviewed by four experienced radiologists in a two-round reading process: first, each radiologist marked lesions in a blinded fashion; then, in a second unblinded round, they reviewed each other’s marks to finalize their own annotations (without forced consensus). All pulmonary nodules ≥3 mm in diameter were annotated with detailed segmentations and were given subjective ratings on nine characteristics (such as subtlety, spiculation, malignancy likelihood). Nodules smaller than 3 mm were also noted (as “non-measured” nodules) but not segmented or characterized in detail. The LIDC-IDRI provides a rich reference standard with multi-observer annotations, encompassing over 2600 distinct nodules in total across the dataset.

LNDb dataset: The Lung Nodule Database (LNDb) is a more recent dataset designed to complement LIDC-IDRI by providing an external validation cohort with a focus on radiologist variability and local clinical practice23. LNDb consists of 294 chest CT scans collected from a single hospital (CHUSJ in Porto, Portugal) between 2016 and 2018. The inclusion criteria and annotation protocol for LNDb closely followed those of LIDC-IDRI: radiologists annotated all nodules ≥3 mm with manual segmentations and recorded the same set of nine nodule attributes used in LIDC-IDRI. They also marked smaller nodules (<3 mm) and certain non-nodule radiographic findings that could be mistaken for nodules, providing a more exhaustive labeling of potential findings in each scan. Five radiologists (each with at least 4 years of experience) participated in the LNDb annotations. Each scan was read by at least one radiologist, and a subset of scans received multiple independent readings (90 scans were annotated by three different radiologists, 145 scans by two radiologists, and the remaining by a single reader). This yielded a total of 1429 annotated findings (including all nodules and non-nodule lesions) in the database, reflecting the presence of up to a few nodules per scan on average. Notably, LNDb also includes eye-tracking data recorded during the radiologists’ reading sessions, which can facilitate studies of observer attention and human-AI interaction, although these gaze data are supplementary to the core CT images and annotations.

Tianchi dataset: The Tianchi lung nodule dataset (named after the Alibaba Tianchi competition platform) was released as part of an international challenge for automated pulmonary nodule detection. It comprises 1000 low-dose chest CT scans (with 600 used for training and 400 for testing in the original challenge) with a total of 1244 labeled nodules24. For each nodule, the dataset provides the lesion’s center coordinates and diameter (approximate size) as the ground truth annotation. No segmentation masks or radiologist subjective ratings are included in this dataset; the annotations are limited to nodule locations and sizes, reflecting its primary use for detection algorithms. The annotated nodules range from ~3 mm up to 30 mm in diameter (with only one nodule slightly below 3 mm), which is a size range comparable to the inclusion criteria of LIDC-IDRI and LNDb. Because the Tianchi data were prepared for competitive benchmarking, the available labels are confined to the training portion (with the test set labels withheld for challenge evaluation), and the emphasis is on providing a large quantity of scans for algorithm development. This dataset offers a valuable independent testbed from a different population (Chinese screening cases) but lacks the multi-rater and richly characterized annotations present in LIDC-IDRI and LNDb.

Comparative summary: Table 8 summarizes key attributes of the LIDC-IDRI, LNDb, and Tianchi datasets. LIDC-IDRI remains the largest public collection with detailed, multi-radiologist annotations, making it a standard reference for training and internal validation of nodule analysis methods. LNDb is smaller in scale but provides a highly curated set of scans from a different clinical setting, useful for external validation and for studying inter-observer variability (given its multiple readings and eye tracking information). The Tianchi dataset approaches LIDC-IDRI in scale and is valuable for testing generalization of algorithms on an external cohort; however, its annotations are limited to nodule locations (without segmentations or radiologist feature ratings). In combination, these three datasets provide complementary resources: researchers can develop algorithms on the extensive and richly annotated LIDC-IDRI set, validate robustness and calibration using LNDb (which simulates a different clinical population and reading process), and evaluate detection performance on a large held-out set via the Tianchi challenge data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This study relied exclusively on fully de-identified, publicly available datasets (LIDC-IDRI, LNDb, Tianchi, LUNA16) obtained under their respective data-use policies. No interaction with human participants or access to identifiable private information occurred; therefore, institutional review board (IRB) approval and informed consent were not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. This work exclusively utilizes de-identified datasets available from public repositories.

Materials availability

Not applicable. No new biological specimens, cell lines, or other unique materials were generated or used in this work beyond publicly available datasets.

Data Availability

All datasets used in this study are publicly accessible:- LIDC-IDRI: https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/collection/lidc-idri/- LNDb: https://lndb.grand-challenge.org/Data/- Tianchi: https://tianchi.aliyun.com/competition/entrance/231601/information- LUNA16: https://luna16.grand-challenge.org/.

Code availability

Custom scripts for data preprocessing, model training, and evaluation used in this study will be released on GitHub upon publication. All experiments are reproducible using the provided scripts, which are based on standard PyTorch pipelines.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Jiang, W., Zhi, L., Zhang, S. & Zhou, T. A dual-branch framework with prior knowledge for precise segmentation of lung nodules in challenging ct scans. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 28, 1540–1551 (2024).

Hu, T. et al. A lung nodule segmentation model based on the transformer with multiple thresholds and coordinate attention. Sci. Rep. 14, 31743 (2024).

Ma, X., Song, H., Jia, X. & Wang, Z. An improved v-net lung nodule segmentation model based on pixel threshold separation and attention mechanism. Sci. Rep. 14, 4743 (2024).

Tang, Y.-X. et al. Automated abnormality classification of chest radiographs using deep convolutional neural networks. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 70 (2020).

Selvadass, S., Bruntha, P. M., Sagayam, K. M. & Günerhan, H. Satunet: series atrous convolution enhanced u-net for lung nodule segmentation. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 34, e22964 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. An ensemble deep learning model for risk stratification of invasive lung adenocarcinoma using thin-slice CT. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 119 (2023).

Yu, P. et al. Spatial resolution enhancement using deep learning improves chest disease diagnosis based on thick slice CT. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 335 (2024).

Wu-jun, J., Li-jia, Z., Shao-min, Z. & Tao, Z. Ct image segmentation of lung nodules based on channel residual nested u structure. J. Graph. 44, 879 (2023).

Xu, W., Xing, Y., Lu, Y., Lin, J. & Zhang, X. Dual encoding fusion for atypical lung nodule segmentation. In 2022 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1–5 (IEEE, 2022).

Schlemper, J. et al. Attention gated networks: Learning to leverage salient regions in medical images. Med. image Anal. 53, 197–207 (2019).

Yang, H., Shen, L., Zhang, M. & Wang, Q. Uncertainty-guided lung nodule segmentation with feature-aware attention. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 44–54 (Springer, 2022).

Hou, Q., Zhou, D. & Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 13713–13722 (2021).

Ma, J., Yuan, G., Guo, C., Gang, X. & Zheng, M. Sw-unet: a u-net fusing sliding window transformer block with cnn for segmentation of lung nodules. Front. Med. 10, 1273441 (2023).

Zheng, S. et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 6881–6890 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. A semisupervised knowledge distillation model for lung nodule segmentation. Sci. Rep. 15, 10562 (2025).

Shen, J., Hai, Y. & Lin, C. Ct-uformer: an improved hybrid decoder for image segmentation. Vis. Comput. 41, 5361–5371 (2025).

Agnes, S. A., Solomon, A. A. & Karthick, K. Wavelet u-net++ for accurate lung nodule segmentation in ct scans: improving early detection and diagnosis of lung cancer. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 87, 105509 (2024).

Shaker, A. et al. Unetr++: delving into efficient and accurate 3d medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 43, 3377–3390 (2024).

Kuppusamy, P., Kosalendra, E., Krishnamoorthi, K., Diwakaran, S. & Vijayakumari, P. Detection of lung nodule using novel deep learning algorithm based on computed tomographic images. In 2023 Eighth International Conference on Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (ICONSTEM), 1–7 (IEEE, 2023).

Santone, A., Mercaldo, F. & Brunese, L. A method for real-time lung nodule instance segmentation using deep learning. Life 14, 1192 (2024).

Armato III, S. G. et al. The lung image database consortium (lidc) and image database resource initiative (idri): a completed reference database of lung nodules on CT scans. Med. Phys. 38, 915–931 (2011).

Pedrosa, J. et al. Lndb: a lung nodule database on computed tomography https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.08434 1911.08434 (2019).

Tianchi, A. C. Tianchi medical AI competition [season 1]: Intelligent diagnosis of pulmonary nodules dataset https://tianchi.aliyun.com/competition/entrance/231601/information. Contains low-dose chest CT images for pulmonary nodule detection and intelligent diagnosis (2025).

Zhu, S. et al. A Multi-Resolution Hybrid CNN-Transformer Network With Scale-Guided Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 29, 8385–8394 (2005).

Alhajim, D., Ansari-Asl, K., Akbarizadeh, G. & Soorki, M. N. Improved lung nodule segmentation with a squeeze excitation dilated attention based residual unet. Sci. Rep. 15, 3770 (2025).

Banu, S. F., Sarker, M. M. K., Abdel-Nasser, M., Puig, D. & Raswan, H. A. Aweu-net: an attention-aware weight excitation u-net for lung nodule segmentation. Appl. Sci. 11, 10132 (2021).

Liu, J., Li, Y., Li, W., Li, Z. & Lan, Y. Multiscale lung nodule segmentation based on 3d coordinate attention and edge enhancement. Electron. Res. Arch. 32, 3016–3037(2024).

Abdullah, M. & Shaukat, F. Attention-resunet and efficientsasm-unet: Unet based frameworks for lung and nodule segmentation https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.17602 (2025).

Su, H., Lei, H., Guoliang, C. & Lei, B. Cross-graph interaction and diffusion probability models for lung nodule segmentation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 482–492 (Springer, 2024).

Niu, X., Zhang, J., Bai, Y., Gao, M. & Yang, X. Sam-guided accurate pulmonary nodule image segmentation. IEEE Access (2025).

Tang, T. & Zhang, R. A multi-task model for pulmonary nodule segmentation and classification. J. Imaging 10, 234 (2024).

Yadav, D. P., Sharma, B., Webber, J. L., Mehbodniya, A. & Chauhan, S. Edtnet: a spatial aware attention-based transformer for the pulmonary nodule segmentation. PloS One 19, e0311080 (2024).

Zhou, D., Xu, H., Liu, W. & Liu, F. Ln-detr: cross-scale feature fusion and re-weighting for lung nodule detection. Sci. Rep. 15, 15543 (2025).

Shah, A. A., Malik, H. A. M., Muhammad, A., Alourani, A. & Butt, Z. A. Deep learning ensemble 2d cnn approach towards the detection of lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 13, 2987 (2023).

Sui, M. et al. Deep learning-based channel squeeze u-structure for lung nodule detection and segmentation. In 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data & Artificial Intelligence & Software Engineering (ICBASE), 634–638 (IEEE, 2024).

UrRehman, Z. et al. Effective lung nodule detection using deep CNN with dual attention mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 14, 3934 (2024).

Moturi, S. et al. Enhanced lung cancer detection using deep learning ensemble approach. In 2024 First International Conference for Women in Computing (InCoWoCo), 1–7 (IEEE, 2024).

Shaukat, F. et al. Lung-cadex: fully automatic zero-shot detection and classification of lung nodules in thoracic CT images https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.02625 2407.02625 (2024).

Tyagi, S. & Talbar, S. N. Cse-gan: a 3d conditional generative adversarial network with concurrent squeeze-and-excitation blocks for lung nodule segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 147, 105781 (2022).

Kaulgud, R. V. & Patil, A. An effective accurate lung nodule detection of ct images using extensible hunt optimization based deep cnn. In Web Intelligence, vol. 23, 134–151 (SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 2025).

Sivakumar, A., Suganthy, M., Gunasundari, B., Sivamurugan, S. et al. A robust and novel hybrid deep learning based lung nodule identification on ct scan images. In 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Knowledge Discovery in Concurrent Engineering (ICECONF), 1–8 (IEEE, 2023).

Li, Y. & Fan, Y. Deepseed: 3d squeeze-and-excitation encoder-decoder convolutional neural networks for pulmonary nodule detection. In 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1866–1869 (IEEE, 2020).

Lin, C.-Y. et al. Development of a modified 3d region proposal network for lung nodule detection in computed tomography scans: a secondary analysis of lung nodule datasets. Cancer Imaging 24, 40 (2024).

Lu, X. et al. Multi-level 3d densenets for false-positive reduction in lung nodule detection based on chest computed tomography. Curr. Med. Imaging 16, 1004–1021 (2020).

Tang, H., Zhang, C. & Xie, X. Nodulenet: Decoupled false positive reduction for pulmonary nodule detection and segmentation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 266–274 (Springer, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chongqing medical scientific research project (Joint project of Chongqing Health Commission and Science and Technology Bureau, NO.2025MSXM125), the Chongqing University Central University Medical Integration Project (NO.2023CDJYGRH-ZD04), the Joint project of Chongqing Wanzhou Health Commission and Science and Technology Bureau (NO.wzwjw-kw2024026), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81974434), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou City (No. 202201020097), the Foundation of Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (No. 2020-YZ-01), Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (No. 320.6750.2023-19-9, No. 320.6750.2022-22-38), and Key Medical Disciplines Development Project of Guangzhou City.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M., F.W., and T.Z. contributed equally to this work, having full access to all study data and assuming responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the analyses (validation, formal analysis). R.M., Z.Y., and X.H. conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, and participated in securing research funding (conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition). F.W., S.H., and H.T. carried out data acquisition, curation, and investigation (investigation, data curation) and provided key resources, instruments, and technical support (resources, software). T.Z. and W.W. drafted the initial manuscript and generated visualizations (writing–original draft, visualization). J.D., H.L., and Y.Z. supervised the project, coordinated collaborations, and ensured administrative support (supervision, project administration). All authors contributed to reviewing and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content (writing–review & editing) and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ming, R., Wang, F., Zheng, T. et al. GLANCE: continuous global-local exchange with consensus fusion for robust nodule segmentation. npj Digit. Med. 9, 69 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02251-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02251-4