Abstract

Paclitaxel (PTX) is a first-line drug for ovarian cancer (OC) treatment. However, the regulatory mechanism of STUB1 on ferroptosis and PTX resistance in OC remains unclear. Genes and proteins levels were evaluated by RT-qPCR, western blot and IHC. Cell viability and proliferation were measured by CCK-8 and clone formation. The changes of mitochondrial morphology were observed under a transmission electron microscope (TEM). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), iron, malondialdehyde (MDA) and glutathione (GSH) were measured using suitable kits. The interactions among STUB1, HOXB3 and PARK7 were validated using Co-IP, and dual luciferase reporter assay. Our study found that STUB1 was decreased and PARK7 was increased in tumor tissue, especially from chemotherapy resistant ovarian cancer tissue and resistant OC cells. STUB1 overexpression or PARK7 silencing suppressed cell growth and promoted ferroptosis in PTX-resistant OC cells, which was reversed by HOXB3 overexpression. Mechanistically, STUB1 mediated ubiquitination of HOXB3 to inhibit HOXB3 expression, and HOXB3 promoted the transcription of PARK7 by binding to the promoter region of PARK7. Furthermore, STUB1 overexpression or PARK7 silencing suppressed tumor formation in nude mice. In short, STUB1 promoted ferroptosis through regulating HOXB3/PARK7 axis, thereby suppressing chemotherapy resistance in OC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is a fatal gynecologic malignant tumor. In 2020, according to the global data recorded in an authoritative paper, the number of newly diagnosed OC was 313,959, and the number of deaths from OC was 207,2521. The high mortality of OC patients is closely related to multi-aspects, such as chemotherapy resistance2. Paclitaxel (PTX) is recommended as the first-line chemotherapy drug for many cancers, including OC. However, the emergence of drug resistance limits its wide use in clinic3,4. Therefore, improving the sensitivity of OC to PTX and the clinical efficacy of PTX is an urgent problem.

Ferroptosis, a new type of death mode, which is different from autophagy, cell apoptosis, and cell necrosis, is induced by excess iron-dependent lipid peroxide, eventually leading to cell death5. Growing evidences determined that ferroptosis was implicated in mediating drug resistance and tumor progression6,7. However, the underlying mechanism remains indistinct.

Ubiquitination, mediated by E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, widely participates in various biochemical processes, which is a crucial posttranslational modification for numerous proteins8. STIP1 homology and U-box containing protein 1 (STUB1), a E3 enzyme, which affects the substrate specificity of ubiquitination, was identified as a tumor suppressor due to degradation of oncogenic proteins such as p53, SRC‐3 through ubiquitination9,10. A previous study revealed STUB1 was lowly expressed in OC and STUB1 served as a suppressor for OC progression11. However, whether STUB1 participates in PTX resistance and affects ferroptosis and what the molecular regulatory mechanism behind it needs further exploration.

PARK7, also known as DJ-1, was extensively reported in cancers. Accumulating studies have demonstrated the oncogenic role in multi-cancers such as hepatocellular carcinoma and OC12,13. Furthermore, PARK7 was documented to have far-reaching influences on malignant phenotypes of cancer cells, such as, proliferation, migration, invasion, as well as chemotherapy resistance14,15. As previously reported, PARK7 knockdown overcome platinum resistance in OC to some extent16. However, whether PARK7 inhibits PTX resistance in OC is unclear. Therefore, here, we focused on studying the influences of PARK7 on PTX resistance in OC and its underlying mechanism. Homeobox (HOX) gene family could encode a series of proteins as transcription factors, which regulate crucial genes’ expression to participate in tumor progression17. Homeobox B3 (HOXB3) established strong relationship with different tumor types, including acute myeloid leukemia, colon cancer, and OC18,19,20. Particularly, some studies documented that HOXB3 could regulate chemoresistance in tumors21. However, there is little research on whether HOXB3 is involved in PTX resistance in OC.

In addition, we predicted that HOXB3 may be a potential ubiquitination substrate for STUB1 and that HOXB3 may bind to the promoter region of PARK7 via bioinformatics websites. Therefore, we speculated that STUB1 might mediate HOXB3 ubiquitination to promote ferroptosis through inhibiting PARK7 expression, thereby inhibiting PTX resistance in OC, which might provide a new approach for enhancing the sensitivity of PTX to OC.

Results

STUB1 was abnormally low expressed in chemotherapy resistant OC tissues and cells

Firstly, the expression of STUB1 in OC was analyzed through the TCGA_GTEx database, and the results showed that STUB1 had lower expression in tumor tissues from OC patients (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Then, we collected the tumor samples and para-carcinoma samples from chemotherapy OC patients. As presented in Fig. 1a, STUB1 was evidently lower expression in tumor samples than in para-carcinoma samples. Further analysis exhibited that compared to that in tumor samples from PTX/CBP chemotherapy sensitive OC patients, STUB1 expression was apparently declined in tumor samples from PTX/CBP chemotherapy resistant OC patients (Fig. 1b). Extensive data analysis indicated the positive relationship between STUB1 expression and PTX sensitivity in OC (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Kaplan–Meier revealed low expression of STUB1 had a positive relationship with poor prognosis of OC patients (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Subsequently, we detected IC50 value of PTX using CCK-8 assay and the results exhibited that IC50 value of PTX in SKOV3/R cells was about 79.8 nM, and in A2780/R cells was about 61.3 nM, which values were higher than their parental cells, respectively (Fig. 1c). In addition, STUB1 expression was dramatically reduced in PTX-resistant cells compared to PTX-sensitive cells (Fig. 1d). Taken together, STUB1 expression was abnormally reduced in chemotherapy resistant OC tissues and cells, suggesting STUB1 might be engaged in chemotherapy resistant OC.

a STUB1 expression was measured in tumor tissues and adjacent tissues from OC patients using RT-qPCR. b STUB1 expression was examined in chemotherapy resistant and chemotherapy sensitive samples from OC patients using RT-qPCR. c IC50 value of PTX in SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells was detected by CCK-8. d STUB1 expression was examined in PTX-resistant or sensitive OC cells by RT-qPCR. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

STUB1 overexpression attenuated chemotherapy resistance in OC by suppressing cell proliferation and promoting ferroptosis

To further probe whether STUB1 is implicated in regulating PTX-resistant OC cells, SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were transfected with oe-STUB1, and STUB1 expression was notably enhanced (Fig. 2a, b). Besides, we found that PTX treatment or STUB1 overexpression could suppress cell viability and cell proliferation of PTX-resistant cells, and its combination achieved stronger inhibition of cell viability and cell proliferation (Fig. 2c, d). As expected, we observed STUB1 overexpression evidently elevated cell apoptosis in PTX-treated OC cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). Ferroptosis, as a common cell death mode, is usually accompanied by morphological changes and dysfunction of cellular mitochondria22. Growing studies have shown that ferroptosis was involved in the progression of OC23. In addition, STUB1 was reported to promote ferroptosis in tumor24. Afterwards, mitochondrial morphology was observed using a TEM. PTX treatment resulted in mitochondrial atrophy, reduced mitochondrial ridges, and increased membrane density in PTX-resistant cells. However, co-processing with PTX and oe-STUB1 caused greater damage to mitochondria, while Fer-1, a ferroptosis inhibitor, reversed the destructive effect of PTX treatment and STUB1 overexpression on mitochondria (Fig. 2e). For cell viability, the results revealed that STUB1 overexpression resulted in decreased cell viability in PTX-treated OC cells, however, Fer-1 treatment compromised this effect (Fig. 2f). In addition, we observed an increase in ROS, iron, and MDA production and a decrease in GSH and GPX4 level in PTX-treated SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells, while these alterations were enhanced PTX treatment in combination with STUB1 overexpression. However, Fer-1 treatment abolished the promoting effect of PTX and STUB1 combination treatment on ferroptosis (Fig. 2g, j). These results revealed that STUB1 was related to ferroptosis in chemotherapy resistant OC. PARK7 was reported to be implicated in ferroptosis and platinum-resistant OC16,25. What’s more, ferroptosis occurs with a decrease in GPX4, the regulatory core enzyme of the antioxidant system (the glutathione system)26. Here, we found PARK7 and GPX4 expression was declined evidently by PTX treatment, and this change was strengthened in PTX-treated, and STUB1 overexpressed, while Fer-1 treatment restored this impact (Fig. 2k), suggesting that in chemotherapy resistant OC, PARK7 might play an essential role in STUB1-mediated ferroptosis.

a, b STUB1 expression was examined in oe-STUB1-transfected PTX-resistant OC cells by RT-qPCR and western blot. SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were transfected with oe-STUB1 upon PTX treatment. c Cells viability was examined using CCK-8. d Cells proliferation was evaluated using clone formation assay. SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were transfected with oe-STUB1 upon PTX and Fer-1 treatments. e Mitochondrial morphology was monitored using a TEM. (f ) Cell viability was detected using CCK-8. g–j ROS, iron, MDA, and GSH were detected using suitable kits. k PARK7 and GPX4 levels were determined using western blot. N = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

STUB1 inhibited HOXB3 expression through ubiquitinating HOXB3

As previously described, HOXB3 mediated tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer21. Here, in oe-STUB1-transfected PTX-resistant OC cells, STUB1 expression was observably elevated and HOXB3 expression was markedly declined (Fig. 3a). The interaction between STUB1 and HOXB3 was validated by Co-IP (Fig. 3b). Additionally, STUB1 overexpression-mediated downregulation of HOXB3 expression was attenuated by MG132 (a proteasome inhibitor) treatment, indicating STUB1 might regulate HOXB3 expression through ubiquitination of HOXB3 (Fig. 3c). Further analysis revealed that STUB1 overexpression weakened the stability of HOXB3 after CHX treatment (Fig. 3d). Moreover, HOXB3 ubiquitination was promoted by STUB1 overexpression (Fig. 3e). These results revealed that STUB1-mediated promotion of HOXB3 ubiquitination in PTX-resistant OC cells.

a STUB1 and HOXB3 levels were determined in oe-STUB1-transfected SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells using western blot. b The interaction between STUB1 and HOXB3 was validated by Co-IP. c HOXB3 level was determined in oe-STUB1-transfected PTX-resistant OC cells upon MG132 treatment using western blot. d The degradation of HOXB3 protein was detected in oe-STUB1-transfected SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells upon CHX treatment using western blot. e HOXB3 ubiquitination was examined in oe-STUB1-transfected PTX-resistant OC cells using western blot. N = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

STUB1 suppressed cell proliferation and induced ferroptosis of PTX-resistant OC cells by downregulating HOXB3 expression

As presented in Supplementary Fig. 1d, the bioinformatics analysis showed HOXB3 expression was upregulated in OC tissues. Kaplan-Meier suggested high expression of HOXB3 had a positive relationship with poor prognosis of OC patients (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Additionally, we also observed the correlation between STUB1 and HOXB3 expression in OC patients, and there is no significant correlation between STUB1 and HOXB3 (Supplementary Fig. 1h). This may be due to the downward trend of STUB1, but it is not significant. Firstly, HOXB3 expression was knocked down in SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells (Fig. 4a, b). To explore whether HOXB3 was implicated in STUB1-mediated influences on cell proliferation and ferroptosis in PTX-resistant OC cells, sh-STUB1 was transfected into HOXB3 downregulation PTX-treated SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells. HOXB3 downregulation-mediated suppression of PTX-resistant OC cell viability and proliferation upon PTX treatment was reversed by STUB1 suppression (Fig. 4c, d). HOXB3 knockdown contributed to destructive impact on PTX-resistant OC cell mitochondria upon PTX treatment, while STUB1 silencing abolished this phenomenon (Fig. 4e). Moreover, STUB1 knockdown attenuated HOXB3 downregulation-mediated elevation of ROS, iron and MDA and downregulation of GSH and GPX4 levels in SKOV3/R and A2780/R upon PTX treatment (Fig. 4f–j). Of note, PARK7 expression was inhibited by HOXB3 silencing, which was restored by STUB1 downregulation (Fig. 4j). All in all, STUB1-mediated suppression of cell proliferation and promotion of ferroptosis in PTX-resistant OC cells by regulating HOXB3.

a, b HOXB3 expression was examined in sh-HOXB3-transfected SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells by RT-qPCR and western blot. sh-STUB1 with/without sh-HOXB3 was transfected into SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells upon PTX treatment. c Cells viability was examined using CCK-8. d Cells proliferation was evaluated using clone formation assay. e Mitochondrial morphology was monitored using a TEM. f–i ROS, iron, MDA and GSH were detected using suitable kits. j PARK7 and GPX4 levels were determined using western blot. N = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

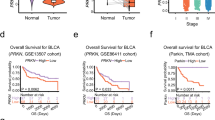

HOXB3 elevated PARK7 expression by activating PARK7 transcription

As presented in Fig. 2j and Fig. 4j, PARK7 expression was regulated by STUB1 and HOXB3, we explored the role of the HOXB3/PARK7 axis in OC progression. Firstly, we found PARK7 level was elevated in tumor tissues compared to para-carcinoma tissue, and also enhanced in chemotherapy resistant OC tissues compared to chemotherapy sensitive OC tissues (Fig. 5a–c). Of note, STUB1 expression had no relationship with PARK7 expression in tumor tissues from OC patients (Supplementary Fig. 1i). In addition, HOXB3 is a transcription factor. JASPAR database predicted that there was a binding site between HOXB3 and PARK7 promoter (Fig. 5d). HOXB3 overexpression apparently increased luciferase activity in PARK7-WT group, but hardly impacted in PARK7-MUT, validating the interaction between HOXB3 and PARK7 promoter (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, HOXB3 overexpression contributed to elevation of HOXB3 and PARK7 expression at mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5f, g). The above results indicated that PARK7 expression was abnormally elevated in chemotherapy resistant OC and was regulated by HOXB3.

a, c PARK7 expression was measured in samples from OC patients using RT-qPCR and western blot. b PARK7 expression was examined in tumor samples from chemotherapy resistant and chemotherapy sensitive OC patients using RT-qPCR. d The binding site between HOXB3 and PARK7 promoter was predicted using JASPAR database. e The interaction between HOXB3 and PARK7 promoter was validated by luciferase activity assay. f, g HOXB3 and PARK7 expression were measured in oe-HOXB3-transfected PTX-resistant OC cells by RT-qPCR and western blot. N = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

STUB1 suppressed proliferation and promoted ferroptosis of PTX-resistant OC cells by mediating the HOXB3/PARK7 axis

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1f, PARK7 expression was increased in tumor tissues from OC patients. High expression of PARK7 had a positive relationship with poor prognosis of OC patients (Supplementary Fig. 1g). In PTX-resistant OC cells, PARK7 expression was evidently silenced by sh-PARK7 transfection (Fig. 6a, b). In addition, the expression of STUB1 was reduced after transfection with sh-STUB1 (Supplementary Fig. 3). To investigate the role of the STUB1/HOXB3/PARK7 axis in PTX-resistant OC cells, sh-PARK7 with/without oe-HOXB3 or sh-STUB1 was transfected into PTX-resistant OC cells and followed by PTX treatment. PARK7 silencing in combination with PTX treatment significantly inhibited cell viability and proliferation, whereas co-transfection with oe-HOXB3 or sh-STUB1 abolished PARK7 silencing-mediated inhibition of cell viability and proliferation of PTX-treated SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells (Fig. 6c, d). In addition, mitochondrial morphology was damaged by PTX treatment, which was aggravated by co-transfecting with PARK7 silencing and PTX treatment. However, HOXB3 overexpression or STUB1 downregulation alleviated changes of mitochondrial morphology of PTX-treated SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells from PARK7 silencing-mediated destructive influence (Fig. 6e). Additionally, silencing of PARK7 induced the upregulation of ROS, iron, and MDA and reduction of GSH in PTX-treated SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells, whereas HOXB3 overexpression or STUB1 downregulation reversed these effects (Fig. 6f–i). Moreover, GPX4 and PARK7 levels were decreased by PARK7 silencing in PTX-treated OC cells, whereas HOXB3 overexpression or STUB1 downregulation compromised these alterations. (Fig. 6j). To sum up, STUB1 promoted ferroptosis in PTX-resistant OC cells by HOXB3/PARK7 axis.

a, b PARK7 expression was examined in sh-PARK7-transfected SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells by RT-qPCR and western blot. sh-PARK7 with/without oe-HOXB3 or sh-STUB1 was transfected into PTX-resistant OC cells upon PTX treatment. c Cells viability was examined using CCK-8. d Cells proliferation was evaluated using clone formation assay. e Mitochondrial morphology was monitored using a TEM. f–i ROS, iron, MDA, and GSH were detected using suitable kits. j PARK7 and GPX4 levels were determined using western blot. N = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

STUB1 suppressed PTX-resistant OC in vivo by regulating HOXB3/PARK7 axis

To explore STUB1/HOXB3/PARK7 axis in PTX-resistant OC in vivo, mice were injected subcutaneously with SKOV3/R cells which were subjected to oe-STUB1 or sh-PARK7 transfection and treated with PTX. After 5 weeks, the tumor tissues were isolated. We found PTX treatment inhibited tumor size and weight, whose effects were further reinforced by STUB1 overexpression or PARK7 silencing (Fig. 7a–c). Furthermore, PTX treatment elevated STUB1 expression and decreased PARK7 and GPX4 expression, which influences were intensified by STUB1 overexpression (Fig. 7d, e). As shown in Fig. 7d, compared with the control, overexpression of STUB1 or knockdown of PARK7 increased survival rate. Of note, PTX-mediated reduction of PARK7 expression was further strengthened by PARK7 silencing, but PARK7 silencing had no influence on STUB1 expression, which was determined using western blot (Fig. 7e). As expected, the results of IHC also revealed that PTX inhibited PARK7 and GPX4 expression in tumor tissues of mice and STUB1 overexpression or PARK7 silencing further suppress PARK7 and GPX4 expression in presence of PTX treatment (Fig. 7f). Taken together, STUB1 overexpression and PARK7 silencing suppressed tumor formation on PTX-resistant OC.

SKOV3/R cells with oe-STUB1 or sh-PARK7 transfection were subcutaneously injected into mice in the presence of PTX. a The images of tumors. b Tumor sizes. c Tumor weight. d Survival rate analysis. e STUB1 and PARK7 levels were determined using a western blot. f GPX4 and PARK7 expression was evaluated by IHC. N = 6. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

PTX, as a frontline therapeutic agent, has been widely used for OC27. The emergence of PTX resistance leads to the significantly reduced or even ineffective effect of PTX in OC patients28. Currently, the mechanism underlying PTX resistance in OC remains ambiguous. Ferroptosis was identified as a crucial event in the chemoresistance of tumors29. For instance, Propofol promoted the reversal of cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer through accelerating ferroptosis30. Qin et al. pointed out that ferroptosis inhibited by circRNA circSnx12/miR-194-5p/SLC7A11 axis was involved in cisplatin chemoresistance to OC31. In this study, we found that STUB1 inhibited PTX resistance in OC by regulating HOXB3/PARK7 axis (Fig. 8).

As an E3 ligase of great concern in ubiquitination process, STUB1, was widely explored in a variety of diseases, especially in multi-cancers32,33,34. As previously documented, STUB1 promoted VEZF1 ubiquitination and destabilized VEZF1 protein, suppressing cell growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma35. Of note, a prior research revealed STUB1 was apparently inhibited in OC and STUB1 upregulation suppressed cell growth and tumor formation of OC11, suggesting STUB1 probably play a vital role in OC progression. Here, we also determined that STUB1 was lowly expressed in tissues from OC patients. In addition, several published papers reported STUB1 could promote reversal of drug resistance such as mitomycin C, cisplatin, and etoposide in gastric cancer, enzalutamide in prostate cancer36,37. Herein, our findings unveiled STUB1 was reduced in tissues from PTX/CBP chemotherapy-resistant patients and PTX-resistant OC cells. STUB1 overexpression suppressed cell proliferation promoted ferroptosis of PTX-resistant OC cells and restrained tumor formation in mice that were inoculated with PTX-resistant OC cells. In short, we provided experimental evidence about STUB1 involving the regulation of PTX resistance in OC cells through promoting ferroptosis.

According to STUB1 possessing the capability of inhibiting PTX resistance in OC by facilitating ferroptosis, what is the molecular regulatory mechanism behind it? In this study, HOXB3 was found to be involved in PTX resistance as a substrate for STUB1. A series of experiments confirmed that STUB1 interacted with HOXB3, and STUB1 reduced the stability of HOXB3 and inhibited HOXB3 expression through mediating ubiquitination of HOXB3. Depending on previously reported, HOXB3 has been identified as a carcinogenic molecule in a variety of cancers. For example, upregulation of HOXB3 expression contributed to poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma38. In OC, higher HOXB3 expression resulted in unfavorable prognosis20, indicating HOXB3 might play a crucial role in OC. Moreover, HOXB3 was reported to have a positively relationship with cisplatin resistance in OC20. Here, we further verified that HOXB3 regulated by STUB1-mediated ubiquitination of HOXB3 was engaged in chemotherapy resistant OC. Rescue experiments exhibited that HOXB3 upregulation compromised STUB1-mediated suppression of cell viability and proliferation and promotion of ferroptosis in PTX-resistant OC cells. Based on the abovementioned evidence, we confirmed STUB1-mediated ubiquitination degradation of HOXB3 to accelerate ferroptosis in PTX-resistant OC cells.

Accumulating studied have determined that PARK7 contributed to chemoresistance in various cancers. A previous study suggested that PARK7 silencing enhanced erlotinib sensitivity in pancreatic cancer39. Qiu and co-workers reported that PARK7 had a positive correlation with resistance of adriamycin, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and vincristine in gastric cancer40. In platinum-resistant OC, Schumann et al. exhibited that PARK7 knockdown could attenuate platinum resistance16. These papers supported the viewpoint that PARK7 was implicated in chemoresistance in cancers, including OC. At present, few reports mention the role of PARK7 in PTX-resistant OC. Our experimental results revealed PARK7 was abnormally higher expression in tissues from OC patients, especially from PTX/CBP chemotherapy-resistant OC patients. PARK7 silencing suppressed cell growth and promoted ferroptosis in PTX-resistant OC cells. Moreover, PARK7 silencing observably reduced tumor sizes in mice that were inoculated with PTX-resistant OC cells. In addition, PARK7 promoter had a binding site for HOXB3, which is an important transcription factor, for example, HOXB3 transactivate CDCA3 expression through binding to CDCA3 promoter in prostate cancer41, indicating PARK7 expression might be regulated by HOXB3. In the current study, we validated the interaction between HOXB3 and PARK7 promoter. HOXB3 overexpression led to higher PARK7 expression. Moreover, HOXB3 overexpression reversed PARK7 silencing-mediated influences on cell growth and ferroptosis.

In conclusion, we summarized that STUB1 promoted ferroptosis to inhibit PTX resistance in OC through mediating HOXB3 ubiquitination to reduce PARK7 expression. Our findings might provide a novel mechanism for PTX-resistant OC. However, there are some limitations in our research, especially in the experimental methods. For instance, ROS could be determined by C11-BODIPY fluorescent probe. The concentration of iron ions in the cells could be labeled using probes or fluorescent dyes. The interaction between protein and ubiquitin could be analyzed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. In our research, we will consider more experimental methods to explore our research purpose in the future.

Materials and methods

Tissue collection from OC patients

All samples (30 cases) were taken from the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. All patients were diagnosed as OC and received chemotherapy (PTX/carboplatin) after surgery. Among these cases, 18 cases of resistance and 12 cases of sensitivity. Of note, chemotherapy sensitivity refers to patients undergoing biopsy for pathological analysis and CT scan analysis of surrounding changes approximately after about three months of chemotherapy with PTX/carboplatin. If there was no further malignant development, it meant that patients were sensitive to chemotherapy; otherwise, it was chemotherapy resistance. All patients were informed of consent forms. The experimental protocol was authorized by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (No. 20230313). And the study methodologies conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell culture and treatment

SKOV3 and A2780 cell lines were purchased from ATCC (USA). PTX‐resistant cells (SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells) were generated according to a previous study42. SKOV3 and SKOV3/R cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). In short, SKOV3 and A2780 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing PTX (Shenyang Sinopharm Group, China) at a concentration of 0.1 nM for 24 h. Then, the surviving cells were selected for the next survival selection step using a higher PTX concentration (increase the original PTX concentration by 0.5 nM). Thus, cells that survived the intervention of 10 nM PTX were considered to be PTX-resistant cells. A2780 and A2780/R cells were cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). These two kinds of medium were supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% antibiotics (Beyotime, China) and cells were cultured under the condition of 5% CO2 and 37°C.

1 µM Fer-1 (MedChemExpress) was added into SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells for 1 h to detect ferroptosis-related indicators.

Cell transfection

The short hairpin RNA targeting PARK7 (sh-PARK7), STUB1 (sh-STUB1), and HOXB3 (sh-HOXB3), overexpression vector of STUB1 (oe-STUB1) or HOXB3 (oe-HOXB3) as well as their negative control group (sh-NC, oe-NC) were purchased from GenePharma (China). SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were implanted into 6-well plates at the density of 2 × 105 cells/well and continued to grow ~80% confluent. Cells were transfected with the above plasmids for 48 h using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Invitrogen, USA) following the instruction. The transfection efficiency was confirmed through RT-qPCR and Western blot. The transfected SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were used for the subsequent experiments. The sequences of sh-PARK7, sh-HOXB3, and sh-STUB1 are listed in Table S1.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells and tissues using TRIzol reagent (Beyotime). Subsequently, RNA concentration and purity were evaluated through NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (USA). When the ratio of absorbance at 260 nm to 280 nm was greater than 1.9 and less than 2.1, the extracted RNA had good purity and could be used for RT-qPCR. 1 μg RNA was used to synthesize cDNA synthesis using Script Reverse Transcription Reagent Kit (TaKaRa, China). qPCR process was implemented by SYBR Premix Ex Taq II Kit (TaKaRa). The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s. GAPDH as reference gene, and 2−ΔΔCt method was used to calculate the relative expression of targeted genes. The primer sequences were as follows (5’-3’):

STUB1 (F): TACCTCTCCAGGCTCATTGC,

STUB1 (R): TCTTGCCACACAGGTAGTCG;

HOXB3 (F): GGCAAACGTCCAAGCTGAA,

HOXB3 (R): CTCCAGCTCCACCAGCTGCG;

PARK7 (F): CCGTGATGTGGTCATTTGTC,

PARK7 (R): TTCATGAGCCAACAGAGCAG;

GAPDH (F): CCAGGTGGTCTCCTCTGA,

GAPDH (R): GCTGTAGCCAAATCGTTGT.

Western blot

Total protein was extracted from cells and tissues using RIPA buffer (Beyotime) containing Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime). Through a standard curve obtained by preparing a series of standard concentrations of protein, the protein concentrations of samples were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime). Then, equal amount of protein (30 μg) was loaded in loading hole of SDS-PAGE and then separated through electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the separated proteins were further transferred onto PVDF membranes at 80 V voltage for 1.5 h under ice bath conditions. Subsequently, PVDF membranes were blocked using 5% BSA, the PVDF membranes were incubated with primary antibodies including STUB1 (ab134064, 1:20000, Abcam, Britain), HOXB3 (PA5-103890, 1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific), PARK7 (ab76008, 1:5000, Abcam), GPX4 (ab125066, 1:5000, Abcam), Ubiquitin (ab134953, 1:5000, Abcam) and GAPDH (ab8245, 1:5000, Abcam) overnight at 4 °C. Then, Tris-buffered saline tween solution was used for washing PVDF membranes three times. The HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was used to incubate PVDF membrane for 1 h. A ECL kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was applied to react with proteins on membranes. The densitometry analysis was estimated by Image J.

Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

CCK-8 (Dojindo, Japan) assay was applied to determine IC50 value of PTX and cell viability. For determination of IC50 value, SKOV3, SKOV3/R, A2780, A2780/R cells were seeded into 96-well plates at the density of 1 × 103 cells/well and then were treated with PTX at different concentrations (10−2, 10−1, 100, 101, 102, 103 nM). For evaluation of cell viability, SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were subjected to indicated treatments and implanted onto 96-well plates at the density of 1 × 103 cells/well and cultured for 24 h. Subsequently, 10 μL CCK-8 solution from a commercial kit (Beyotime) was added to each well. After 2 h incubation, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm by a spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, USA). The absorbance of every well was used to calculate IC50 values and cell viability.

Clone formation assay

SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were implanted onto six-well plates at the density of 1 × 103 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C. Two weeks later, methanol was applied for the fixation of cells, and 0.1% crystalized violet (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used for staining for 30 min. The cloned cells were observed and calculated under an optical microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed to detect cell apoptosis. In short, ~2 × 106 cells were collected, and the cells were fixed by pre-cooled ethanol, then cells were cultured with 1 mL PI (Beyotime) stain in the dark. After incubation for 30 min, samples were immediately analyzed using flow cytometry.

The observation of mitochondrial morphology

Cells were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde and then embedded in 1% osmium tetroxide. Subsequently, cells were immersed in acetone and embedding medium overnight after dehydration. Then, cells were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Finally, cell ultrastructures were observed using a TEM (Hitachi, Japan).

Quantification of MDA, GSH, and iron levels

SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were in the state of the logarithmic growth phase and then were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well. After being cultured for 24 h, the cells were collected by trypsin digestion and sonicated in an ice bath. Subsequently, according to manufacturer’s instructions, levels of MDA, GSH, iron in cells were evaluated using MDA and GSH activity assay kits (Beyotime), and iron assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China), respectively. Absorbances were obtained at 532 nm, 412 nm, and 510 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA). Using absorbances, the levels of MDA GSH and iron in cells were calculated.

Determination of ROS production

Intracellular ROS was determined for the ROS assay kit (Beyotime), which is a kit for the detection of ROS using fluorescent probe DCFH-DA. DCFH-DA itself had no fluorescence, and could be hydrolyzed into DCFH by intracellular esterase when entering the cell. DCFH could not permeate the cell membrane, allowing the probe to remain inside the cells. Under the action of ROS, the non-fluorescent DCFH was transformed into fluorescent DCF. The level of ROS was assessed by detecting fluorescence of DCF. In brief, SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at the density of 1 × 105 cell/well and cultured overnight. Subsequently, SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were stained with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 20 min at 37°C. Subsequently, the cells were washed three times with serum-free cell culture solution to fully remove DCFH-DA that had not entered the cells. Afterward, fluorescence was measured using flow cytometry. The flow cytometry data were analyzed by FlowJo_V10 software (Tree Star, USA).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

Cells were extracted with Co-IP buffer on ice for 1 h. Subsequently, the lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min. The lysates were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies including IgG (Abcam) or Flag antibody (HOXB3) conjugated to Protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). Afterwards, the proteins pulled down by the magnetic beads was eluted and then was detected by western blot.

Protein stability and degradation experiment

SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells were implanted 1 day before transfection in 12-well plates at 1.0 × 105 cells/well. When the cell density reached 70% confluency, oe-NC or oe-STUB1 plasmids were transfected into SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells. At 24 h post-transfection, 100 μg/mL CHX (MedChemExpress), an inhibitor of protein synthesis, was added into SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells with oe-NC or oe-STUB1 transfection for 0, 4, 8, 12 h, respectively. The decay of HOXB3 protein level was detected using western blot. Approximately 48 h after transfection, a proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μg/mL, MedChemExpress, China) was added into cells for 4 h to observe the alteration of HOXB3 protein level by western blot.

Ubiquitination assays

Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h and lysed with 80 μL of IP buffer and 10 μL of 10% SDS, then heated at 95°C for 15 min. After 10× dilution with cold buffer, the sample preparation was completed according to the above IP methods.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The wild‐type and mutant-type PARK7 promoter sequences were cloned into a pGL3 vector (Promega, Beijing, China) to construct reporter vectors PARK7-WT and PARK7-MUT. PARK7-WT/PARK7-MUT and oe-HOXB3 vectors were co-transfected into SKOV3/R and A2780/R cells using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (Invitrogen). Luciferase activity was evaluated using a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, China).

Tumor formation in nude mice

The BALB/c nude mice (female, 15–20 g, 5-6 weeks old) were purchased from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. SKOV3/R cells were stably transfected with oe-STUB1 or sh-PARK7. Transfected cells were subcutaneously injected into nude mice for tumor formation and followed by PTX treatment. The detailed groups were as follows: control, PTX, PTX+oe-NC, PTX+oe-STUB1, PTX+sh-NC, PTX+sh-PARK7. When the tumors reached a diameter of roughly 5 mm, PTX (10 mg/kg) was administered to mice through intraperitoneal injection. The tumor volume was measured every seven days for 5 consecutive weeks. After 5 weeks, tumor tissues were detached for subsequent experiments, including tumor weight detection, western blot, and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Animal experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the Guizhou Medical University (No.2305190).

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed to determine GPX4 and PARK7 protein expression in tumor tissues from mice. Briefly, transplanted tumor tissue underwent fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and embeddedness with paraffin. Afterward, roughly 5 μm sections were prepared. The paraffin sections were baked at 60 °C for 2 h and dewaxed in fresh xylene for 30 min. Subsequently, the sections were hydrated with gradient alcohol, followed by boiling them in a pressure cooker containing sodium citrate for 2 min to retrieve the antigens. After repairing the antigen, the sections were blocked with 1% BSA for 20 min. The sections were incubated with antibodies against GPX4 (ab125066, 1:200, Abcam), PARK7 (ab76008,1:1000, Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS buffer, the sections were then incubated with HRP-labeled antibody for 1 h. Then, the sections were counterstained with diaminobenzidine. The images were observed under an optical microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Statistics and reproducibility

All data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). GraphPad Prism 8 was applied to analyze data. Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance were used for comparison of groups. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was adopted to depict the correlations between crucial molecules and overall survival in OC patients. Pearson correlation analysis was used for the analysis of the correlations among STUB1, HOXB3, and PARK7 expression in OC patients. p < 0.05 was regarded as a statistically significant difference.

Change history

11 December 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07365-1

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Marchetti, C. et al. Chemotherapy resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer: mechanisms and emerging treatments. Semin. Cancer Biol. 77, 144–166 (2021).

Barbuti, A. M. & Chen, Z. S. Paclitaxel through the ages of anticancer therapy: exploring its role in chemoresistance and radiation therapy. Cancers (Basel) 7, 2360–2371 (2015).

Kuroki, L. & Guntupalli, S. R. Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Bmj 371, m3773 (2020).

Stockwell, B. R. et al. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell 171, 273–285 (2017).

Guo, J. et al. Ferroptosis: A Novel Anti-tumor Action for Cisplatin. Cancer Res. Treat. 50, 445–460 (2018).

Sun, X. et al. Metallothionein-1G facilitates sorafenib resistance through inhibition of ferroptosis. Hepatology 64, 488–500 (2016).

Zhao, B. et al. Protein engineering in the ubiquitin system: tools for discovery and beyond. Pharm. Rev. 72, 380–413 (2020).

Kajiro, M. et al. The ubiquitin ligase CHIP acts as an upstream regulator of oncogenic pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 312–319 (2009).

Muller, P., Hrstka, R., Coomber, D., Lane, D. P. & Vojtesek, B. Chaperone-dependent stabilization and degradation of p53 mutants. Oncogene 27, 3371–3383 (2008).

Shang, Y. et al. CHIP/Stub1 regulates the Warburg effect by promoting degradation of PKM2 in ovarian carcinoma. Oncogene 36, 4191–4200 (2017).

Chen, X. et al. DJ-1/FGFR-1 signaling pathway contributes to sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2543220 (2022).

Davidson, B. et al. Expression and clinical role of DJ-1, a negative regulator of PTEN, in ovarian carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 39, 87–95 (2008).

Chen, Y. et al. DJ-1, a novel biomarker and a selected target gene for overcoming chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. J. Cancer Res Clin. Oncol. 138, 1463–1474 (2012).

Liu, H. et al. Expression and role of DJ-1 in leukemia. Biochem. Biophys. Res Commun. 375, 477–483 (2008).

Schumann, C. et al. Mechanistic nanotherapeutic approach based on siRNA-mediated DJ-1 protein suppression for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Mol. Pharm. 13, 2070–2083 (2016).

Feng, Y. et al. Homeobox genes in cancers: from carcinogenesis to recent therapeutic intervention. Front Oncol. 11, 770428 (2021).

Bi, L. et al. A novel miR-375-HOXB3-CDCA3/DNMT3B regulatory circuitry contributes to leukemogenesis in acute myeloid leukemia. BMC Cancer 18, 182 (2018).

Cui, M. et al. LncRNA-UCA1 modulates progression of colon cancer through regulating the miR-28-5p/HOXB3 axis. J. Cell Biochem. 120, 6926–6936 (2019).

Miller, K. R. et al. HOXA4/HOXB3 gene expression signature as a biomarker of recurrence in patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer following primary cytoreductive surgery and first-line adjuvant chemotherapy. Gynecol. Oncol. 149, 155–162 (2018).

Fu, H. et al. miR-375 inhibits cancer stem cell phenotype and tamoxifen resistance by degrading HOXB3 in human ER-positive breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 37, 1093–1099 (2017).

Gao, M. et al. Role of mitochondria in ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 73, 354–63.e3 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Frizzled-7 identifies platinum-tolerant ovarian cancer cells susceptible to ferroptosis. Cancer Res. 81, 384–399 (2021).

Sun, X. et al. Imatinib induces ferroptosis in gastrointestinal stromal tumors by promoting STUB1-mediated GPX4 ubiquitination. Cell Death Dis. 14, 839 (2023).

Cao, J. et al. DJ-1 suppresses ferroptosis through preserving the activity of S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase. Nat. Commun. 11, 1251 (2020).

Liang, D. et al. Ferroptosis surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by sex hormones. Cell 186, 2748–64.e22 (2023).

Vaidyanathan, A. et al. ABCB1 (MDR1) induction defines a common resistance mechanism in paclitaxel- and olaparib-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 115, 431–441 (2016).

Agarwal, R. & Kaye, S. B. Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 502–516 (2003).

Yang, R., Yi, M. & Xiang, B. Novel insights on lipid metabolism alterations in drug resistance in cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 875318 (2022).

Han, B., Liu, Y., Zhang, Q. & Liang, L. Propofol decreases cisplatin resistance of non-small cell lung cancer by inducing GPX4-mediated ferroptosis through the miR-744-5p/miR-615-3p axis. J. Proteomics 274, 104777 (2023).

Qin, K. et al. circRNA circSnx12 confers Cisplatin chemoresistance to ovarian cancer by inhibiting ferroptosis through a miR-194-5p/SLC7A11 axis. BMB Rep. 56, 184–189 (2023).

Sun, C. et al. Diverse roles of C-terminal Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) in tumorigenesis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 140, 189–197 (2014).

Zhan, S., Wang, T. & Ge, W. Multiple functions of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP in immunity. Int. Rev. Immunol. 36, 300–312 (2017).

Zhang, S., Hu, Z. W., Mao, C. Y., Shi, C. H. & Xu, Y. M. CHIP as a therapeutic target for neurological diseases. Cell Death Dis. 11, 727 (2020).

Shi, X., Zhao, P. & Zhao, G. VEZF1, destabilized by STUB1, affects cellular growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by transcriptionally regulating PAQR4. Cancer Gene Ther. 30, 256–266 (2023).

Tang, D. E. et al. STUB1 suppresseses tumorigenesis and chemoresistance through antagonizing YAP1 signaling. Cancer Sci. 110, 3145–3156 (2019).

Xu, P. et al. Allosteric inhibition of HSP70 in collaboration with STUB1 augments enzalutamide efficacy in antiandrogen resistant prostate tumor and patient-derived models. Pharm. Res. 189, 106692 (2023).

Yan, M., Yin, X., Zhang, L., Cui, Y. & Ma, X. High expression of HOXB3 predicts poor prognosis and correlates with tumor immunity in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49, 2607–2618 (2022).

He, X. et al. Knockdown of the DJ-1 (PARK7) gene sensitizes pancreatic cancer to erlotinib inhibition. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 20, 364–372 (2021).

Qiu, L. et al. DJ-1 is involved in the multidrug resistance of SGC7901 gastric cancer cells through PTEN/PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 52, 1202–1214 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. HoxB3 promotes prostate cancer cell progression by transactivating CDCA3. Cancer Lett. 330, 217–224 (2013).

Li, S. et al. ERp57‑small interfering RNA silencing can enhance the sensitivity of drug‑resistant human ovarian cancer cells to paclitaxel. Int. J. Oncol. 54, 249–260 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Thank you for the funding of this research from the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (qiankehejichu-ZK [2024] Key 452) and the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (qiankehejichu-ZK [2022]). This work was supported by the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (qiankehejichu-ZK [2024] Key 452) and the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (qiankehejichu-ZK [2022]) Science and Technology Fund project of Guizhou Provincial Health Commission (No. 2024GZWJKJXM1253) and Guizhou Provincial People's Hospital Fund (No. GZSYBSA[2021]01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z., H.Y., and D.Z. designed this study. Y.W., S.Y, Q.J., J.T., and X.Z. collected the materials and performed the experiments. L.Z., H.Y. and, D.Z. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. D.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients were informed consent forms. The experimental protocol was authorized by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (no. 20230313). The study methodologies conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. Animal experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the Guizhou Medical University (no. 2305190).

Consent for publication

The informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Yang Sun and Sagar Rayamajhi for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kaliya Georgieva.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Yang, H., Wang, Y. et al. STUB1 suppresses paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer through mediating HOXB3 ubiquitination to inhibit PARK7 expression. Commun Biol 7, 1439 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07127-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07127-z

This article is cited by

-

PDLIM4 drives gastric cancer malignant progression and cisplatin resistance by inhibiting HSP70 ubiquitination and degradation via competitive interaction with STUB1

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2025)

-

Doublecortin-like kinase 1, regulated by STIP1 homology and U-box containing protein 1 or Sp1 transcription factor, affects the malignant behaviors and drug sensitivity in adriamycin-resistant breast cancer cells

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2025)