Abstract

The mycobacterial caseinolytic protease (Clp) system has been recognized as a promising therapeutic target. In this study, we identify two novel ilamycin analogs, ilamycin E (ILE) and ilamycin F (ILF), both targeting the ClpC1 component of the ClpC1P1P2 proteasome. ILE potently disrupts ClpC1P1P2-mediated proteolysis, leading to delayed bactericidal activity, while ILF also binds ClpC1, albeit with lower affinity. Notably, we discover and validate a unique mutation in clpX and a novel insertion in clpC1 both conferring resistance to ILE and ILF in mycobacterium by gene editing. Furthermore, ILE can also inhibit the proteolytic activity of ClpXP1P2 in a manner dependent on the substrate’s tag sequence and adaptor. This first demonstration of clpX- and clpC1-mediated ilamycins resistance underscores the potential of ilamycins to target multiple components of the Clp protease system, offering a novel dual-target strategy for combating mycobacterial infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobactrium tuberculosis (Mtb) continues to pose a significant global public health threat, with the situation being exacerbated by the emergence of drug-resistant Mtb strains1,2. Additionally, infections caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), such as Mycobacterium abscessus (Mab), are on the rise due to intrinsic resistance to almost all the existing antibiotics. In several countries, the incidence of NTM infections has surpassed that of TB3,4. This highlights an urgent need for new drugs with novel mechanisms of action to manage drug-resistant mycobacterial diseases effectively.

The caseinolytic protease (Clp) proteolytic system has recently emerged as a promising therapeutic target in mycobacteria5,6,7,8. This system is pivotal not only for maintaining intracellular protein quality but also for modulating responses to environmental stressors and contributing to the pathogenicity of virulent strains6,9. It comprises multi-subunit protein complexes that facilitate intracellular protein degradation. In mycobacteria, the core complex of the hetero-tetradecamer Clp protease assumes a barrel-shaped structure, constructed from two rings, each composed of seven ClpP1 and seven ClpP2 peptidase subunits. The entry of substrates into the ClpP1P2 complex is stringently regulated and reliant on ATP-dependent AAA+ unfoldases (ClpX or ClpC1), which act as adapters to facilitate substrate entry into the protease chamber through ATP hydrolysis8,10,11. Both the Clp protease genes and the ATPase adapter genes clpX and clpC1 have been found essential for mycobacterial survival8,12.

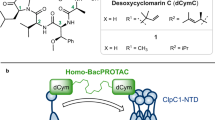

Many non-ribosomal natural cyclic peptides, such as ilamycins (also known as rufomycins), cyclomarin A (CYMA), and ecumicin (ECU), have shown antitubercular activities by targeting the ClpC1 component of the ClpC1P1P2 proteasome13. However, aside from the mutations identified in the clpC1 gene from spontaneous resistant mutants, robust genetic evidence is lacking. Although these compounds all disrupt protein metabolism through the Clp system, their mechanisms of action (MOAs) differ. For example, rufomycin I (RUFI) inhibits the proteolytic activity of the ClpP1P2 complexes by binding to ClpC1, interfering with its binding to ClpP1P2, while CYMA stimulates ClpC1’s ATPase and promotes proteolysis by the ClpC1P1P2 proteasome14,15. On the other hand, ECU stimulates the ATPase activity of ClpC1 but inhibits the proteolysis by ClpC1P1P216. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reported anti-Mtb compounds targeting ClpX.

We previously reported that ilamycin E (ILE) and ilamycin F (ILF), synthesized by Streptomyces atratus SCSIO ZH16 isolated from the South China Sea, exhibited activities against Mtb17. Particularly, ILE demonstrated superior activity against Mtb compared to other ilamycin components and the aforementioned compounds13,17,18. However, their MOAs, activities against NTM and other non-mycobacterial pathogenic bacteria, and potential drug interactions remain to be elucidated. In this study, we discovered that ilamycins target ClpC1 and inhibit the proteolytic activity of the ClpC1P1P2 protease. Additionally, ILE can also impair the proteolytic activity of the ClpXP1P2 protease depending on the tag sequences of the substrate and adapter-mediated recognition. These findings highlight the potential of Clp complexes as viable therapeutic targets, particularly when employing a dual-targeting approach.

Results

ILE and ILF exhibit selective and potent antimycobacterial activities in vitro and ex vivo

The antimicrobial activities of ILE and ILF were evaluated against Mtb and 3 different NTM, including Mab, Mycobacterium marinum (Mmr), and Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm). These mycobacteria were chosen due to their clinical relevance and growth characteristics. Mab, a rapidly growing mycobacterium, is frequently associated with severe human infections and known for its intrinsic antibiotic-resistant nature19,20. Mmr, a slowly growing mycobacterium, is closely related to Mtb but less virulent and serves as a model organism for Mtb studies21,22. Msm is also utilized widely as a model organism due to its rapid growth, non-virulence and the availability of genetic tools22.

ILE and ILF demonstrated significant inhibitory activities against autoluminescent Mtb H37Ra (AlRa)23, Msm (AlMsm)23, and Mmr (AlMmr)24 with varying potencies (Table 1). Notably, ILE exhibited potent activity against autoluminescent Mab (AlMab)25 at a concentration of 1 µg mL−1, whereas ILF only showed weak activity at 20 µg mL−1, though they both showed highly bactericidal activities against Mtb. Compared to RIF, ILE and ILF exhibited delayed antimicrobial activities, initially displaying minor bacteriostatic effects on AlRa, with bactericidal activity emerging after 6 days of incubation (Fig. 1). Similar killing dynamics were observed for AlMsm, AlMab, and AlMmr (Supplementary Fig. 1). Consistent bactericidal activity of ILE was also confirmed against autoluminescent H37Rv (AlRv), addressing concerns regarding the slower growth of H37Ra (Supplementary Fig. 2)26,27. The classical colony-forming unit (CFU) enumeration was also performed to evaluate the antimicrobial activities of ILE and ILF. Consistent with the luminescence inhibition data, ILE and ILF exhibited concentration- and time-dependent bactericidal activities against AlRa, as demonstrated by the substantial reduction in CFU counts after 15 days of incubation (Fig. 1). Specifically, based on CFU enumeration in AlRa, the minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined to be 0.05 μg mL−1 for ILE and 1.25 μg mL−1 for ILF.

Chemical structures, time-kill curves based on relative light units (RLUs), and colony-forming unit (CFU) counts at day 15 against AlRa of ILE (a) and ILF (b). DMSO, solvent control; RIF, positive control. Numbers following the drug names indicate the working concentrations (µg mL−1). The MIClux was defined as the lowest concentration that can inhibit >90% RLUs compared with that from the untreated controls. RLU and CFU data were obtained from independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three technical replicates (n = 3). ****P < 0.0001.

The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of ILE against clinically isolated drug-resistant Mtb strains ranged from 0.01 to 0.05 µg mL−1, which align with the laboratory standard Mtb H37Rv strain (Table 1). Synergistic effects were observed when combining ILE with rifampicin (RIF) or the novel anti-TB drug TB4728, and when combining ILF with isoniazid (INH) or TB47. Partial synergy was noted when ILE was combinedpaired with INH, ethambutol (EMB), clofazimine (CFZ), or bedaquiline (BDQ), and when ILF was combined with CFZ. Additive effects were observed when ILE was combined with streptomycin (STR), and when ILF combined with EMB, STR or BDQ. No antagonism was detected between any of the selected drugs and either ILE or ILF. In murine RAW264.7 macrophages, ILE effectively inhibited AlRv with an MIC of 0.2 μg mL−1, while ILF showed activity at 5 μg mL−1. Cytotoxicity testing of ILE in RAW264.7 cells revealed a 50% toxic concentration (TC50) of 28.24 μg mL−1, suggesting a favorable selectivity index (TC50/MIC = 141.2) relative to its anti-Mtb activity. However, neither ILE nor ILF exhibited activity against common non-mycobacterial clinical pathogens, with MICs exceeding 128 µg mL−1 (Table 1).

Mutations in clpC1 and clpX were identified in ILE/ILF-resistant mutants

To identify target(s) of ILE and ILF, spontaneous mutants of different mycobacterium species were screened. The spontaneous mutation rate for producing ILE-resistant Mtb was ~2.5 ×10−9, which is similar to that of RUFI15 and lower than that of ECU16, lassomycin18, and RIF29.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of 7 ILE-resistant Mtb strains from 4 independent screens revealed no mutation in ClpC1 or its flanking regions, but 5 strains carried a ClpX P30H mutation. Further Sanger sequencing of 17 ILE-resistant Mtb strains identified ClpX (P30H) mutation in 8 strains (47%) and ClpC1 (F80V/C/I) mutations in 11 strains (61%), with 2 strains harboring both mutations (ClpX P30H and ClpC1 F80V/I) (Table 2, Supplementary Data 1). Similarly, WGS of 8 ILE-resistant Mab strains revealed 4 strains with ClpC1 mutations (F2L, Q17R, H77D), one with ClpX P30H, and three without mutation in either genes. Sanger sequencing of the clpX and clpC1 genes from other ILE-resistant Mab strains revealed that there were also ClpC1 (M1-FERF-F2, L88R) mutations (Table 2, Supplementary Data 2). In addition, a small subset of ILE-resistant Mtb or Mab strains did not carry mutation in either clpX nor clpC1, suggesting the potential involvement of alternative resistance mechanisms. In these strains, WGS identified sporadic mutations in genes unrelated to the Clp proteases, such as Rv1572c, MAB_2872c (hisS), or MAB_2670c (hisD) (Supplementary Data 1 and 2), though their relevance to resistance remains to be validated.

However, all examined ILE-resistant Mmr strains and ILF-resistant Msm strains carried mutations exclusively in ClpC1 without any mutation in ClpX (Table 2). Cross-resistance between ILE and ILF was observed in all ILE- or ILF-resistant NTM mutants. These findings suggest that ILE and ILF may both target ClpX and ClpC1, especially in Mtb and Mab.

Docking predicts ILE and ILF bind the N-terminal domain (NTD) of ClpC1 and ClpX

To investigate the interactions of ILE and ILF with ClpC1 and ClpX, we performed molecular docking simulations. Since all mutation sites of ILE and ILF-resistant bacteria are located in ClpC1-NTD (residues 1–145) or ClpX-NTD (residues 1–112), we employed AutoDock to dock ILE into the reported structure of the MtbClpC1-NTD (Fig. 2a)30,31,32 and the AlphaFold2-predicted structure of the MtbClpX-NTD (Fig. 2b), respectively. The docking results indicated that ILE binds to MtbClpC1-NTD and MtbClpX-NTD with predicted binding energies of –7.9 kcal mol−1 and –6.7 kcal mol−1, and corresponding root mean square deviations of 3.5 Å and 2.1 Å, respectively, confirming acceptable docking accuracy. Key residues involved in ILE binding include the known mutation sites Q17, H77, F80, and L88 in MtbClpC1-NTD, and P30 in MtbClpX-NTD (Table 2). Given the structural similarity between ILE and ILF, along with the observed cross-resistance, it is likely that ILF interacts with ClpC1 and ClpX at similar binding sites. Notably, H77 and F80 are also critical for CYMA and RUFI binding, while RUFI additionally involves M1, F2, V13, and E89, and ECU interacts with L92 and L96, indicating a partially conserved binding interface across cyclopeptides30.

Mutations in clpC1 and clpX confer resistance to ILE and ILF in mycobacteria

To validate the role of ClpC1 and ClpX in relation to ILE and ILF, we initially constructed a series of overexpression strains. The wild-type (wt) genes clpXwt and clpC1wt, along with their mutant (mt) variants clpXmt and clpC1mt, were inserted into two extrachromosomal plasmids, p60A33 or pMVA34. These genes were under the robust hsp60 promoter to facilitate overexpression in AlMab, AlMsm, and AlMmr. Among these strains, only the AlMmr strain overexpressing ClpC1L88R demonstrated resistance to both ILE and ILF when compared to the parent strain, exhibiting an 8-fold increase in MIC (Supplementary Table 1). However, the overexpression of ClpC1wt/mt or ClpXwt/mt, as well as the concurrent overexpression of genes encoding the ClpC1P1P2 or ClpXP1P2 proteases in AlMab and AlMsm, did not alter their susceptibility to ILE or ILF. These findings are consistent with previous observations, suggesting that the overexpression of clpC1mt does not necessarily confer resistance to ClpC1-targeting compounds, and that efficacy varies across different mycobacterial species35.

In order to further determine the roles of mutations in clpC1 and clpX in ILE and ILF resistance directly, we aimed to obtain gene-edited strains. Given the slower growth rate of Mtb compared to rapidly-growing mycobacteria such as Msm and Mab, we initially utilized these two NTM36. Utilizing the newly developed CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated gene editing techniques, we introduced specific clpC1 and clpX mutations into Mab and Msm, generating two Mab mutants (ClpC1wt to ClpC1F2L, ClpXwt to ClpXP30H) and three Msm mutants (ClpC1wt to ClpC1F2C, ClpC1wt to ClpC1M1-L-F2, and ClpC1wt to ClpC1I197N)37,38. These genetically modified strains displayed varying levels of resistance as summarized in Table 3. Notably, the ClpXP30H mutation in Mab conferred the highest level of resistance, with MICs exceeding 128 µg mL−1 for both ILE and ILF. The ClpC1F2L mutation in Mab led to a more modest increase in resistance, elevating the MIC for ILE by eight times relative to the parent strain. The mutations ClpC1F2C and ClpC1M1-L-F2 in Msm both resulted in a greater than 4-fold increase in the MICs of ILE and ILF, compared to the parent strain. A comparative analysis of spontaneous mutants and gene-edited strains revealed that mutations at the F2 of ClpC1 in both Mab and Msm confer relatively low-level resistance to ILE and ILF, whereas the P30H mutation in Mab ClpX is associated with high-level resistance, underscoring its crucial role. It is noteworthy that the lack of impact of the Msm ClpC1I197N mutation on ILE and ILF resistance may be attributed to its location outside ClpC1-NTD, suggesting that resistance is primarily driven by alterations within the NTD. Furthermore, the spontaneous mutant strain harboring clpC1I197N also possessed clpC1F2S (Table 2) which may be the principal factor contributing to ILE and ILF resistance.

ILE and ILF alter Msm cell morphology and enhance activity in clpC1 and clpX knockdown strains

To elucidate the bactericidal mechanisms of ILE and ILF, we examined the effect of ILE or ILF treatment on the morphology of Msm cells. Msm was cultured with 0.125 µg mL−1 of ILE or 5 µg mL−1 of ILF for 15 hours (h). As a control, Msm was also treated with 1 µg mL−1 clarithromycin (CLR), a macrolide antibiotic that inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by specifically targeting the 50S subunit of the ribosome. The lengths of CLR-treated cells showed only a modest increase, from 2.07 ± 0.48 μm to 2.64 ± 0.80 μm (Fig. 3a, b). Notably, the cell lengths of Msm increased to 5.95 ± 2.16 μm and 9.41 ± 2.40 μm following ILE and ILF treatment, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). In comparison to untreated and CLR-treated Msm, ILE and ILF both induced a pronounced inhibition of cell division, as evidenced by the formation of division septa (Fig. 3c, d). This observation is consistent with the phenotype observed in Msm upon clpX gene silencing, and the established role of ClpX in regulating FtsZ assembly and Z-ring formation which are crucial processes for cell division in Mtb39,40.

a The cell morphology of Msm without any drug treatment. b The cell morphology of Msm treated with a concentration of 1 µg mL−1 CLR. c The cell morphology of Msm treated with a concentration of 0.125 µg mL−1 ILE. d The cell morphology of Msm treated with a concentration of 5 µg mL−1 ILF. The white arrows highlight the division septa.

Correspondingly, we performed knockdown of clpX and clpC1 in Mab and Msm41. The knockdown of clpX or clpC1 in Mab and Msm strains resulted in heightened sensitivity to ILE and ILF (Fig. 4a, b). Upon induction with anhydrotetracycline (aTc) in the absence of ILE or ILF, growth inhibition was observed in both the clpX or clpC1 knockdown strains of Msm and Mab, highlighting the crucial role of these proteins in cellular proliferation. Additionally, we examined ILE’s intracellular activities against clpC1 and clpX knockdown strains of Mab in murine RAW264.7 macrophages (Fig. 4c). Upon infection and drug treatment, ILE exhibited potent intracellular activity, with significantly enhanced efficacy against clpX and clpC1 knockdown strains compared to the vector control. Conclusively, ILE and ILF may disrupt essential cellular processes regulated by ClpX and ClpC1, leading to bactericidal effects.

a In vitro susceptibility of Mab to ILE or ILF upon aTc-induced gene suppression. b In vitro susceptibility of Msm to ILE or ILF upon aTc-induced gene suppression. The concentrations of ILE and ILF are in μg mL−1. *, Mab strains contained varying plasmids: vector, a vector control with the empty plasmid pLJR962; clpC1, pLJR962-clpC1 for inducible inhibition of the clpC1 gene; clpX, pLJR962-clpX for inducible inhibition of the clpX gene. #, Similarly, Msm strains were differentiated by the plasmids they harbored as that in Mab. c Intracellular susceptibility of Mab to ILE upon gene suppression in RAW264.7 macrophages. Survival rates were calculated as (CFU of ILE-treated group/CFU of untreated group) × 100%. Numbers following the drug names indicate the working concentrations (µg mL−1). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three technical replicates (n = 3). **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001.

ILE and ILF selectively bind to ClpC1-NTD and their binding is disrupted by resistance mutations

Since all mutations occurred within ClpC1-NTD or ClpX-NTD across Mtb, Mab, Msm, and Mmr, and their ClpC1-NTD or the first 64 amino acids of the ClpX-NTD sequences are identical (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), we specifically expressed and purified the MtbClpC1-NTDwt/mt and MtbClpX-NTDwt/mt. Our goal was to investigate whether there is any interaction between these proteins and ILE or ILF. The interactions between the MtbClpC1-NTDwt/mt or MtbClpX-NTDwt/mt with ILE or ILF were examined by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF)42. We discovered that ILE increased the melting temperature (Tm) of MtbClpC1-NTDwt from 68.5°C to 77.5°C (Fig. 5a), indicating a significant enhancement in thermal stability (∆Tm = 9°C). Conversely, ILF altered the thermal stability of the MtbClpC1-NTDwt by only 0.5°C (Fig. 5a) compared to ILE. The stronger affinity of ILE over ILF correlates with its lower MIC. These findings suggest potential interactions of ILE and ILF with MtbClpC1-NTD. To further test whether these interactions are specific and mutation-dependent, we performed DSF assays using a panel of MtbClpC1-NTDmt harboring the acquired mutations from Mtb resistant strains (F80I/L/V/C). Notably, all four mutations markedly reduced the thermal shift induced by ILE (Fig. 5b–e), indicating that these residues are critical for compound binding. The loss of thermal stabilization strongly supports that resistance arises via disruption of drug-target interaction. Notably, DSF assays of MtbClpX-NTDwt/mt failed to produce typical sigmoidal melting curves, likely due to the small size and compact nature of the domain (residues 1–112), which may limit the exposure of hydrophobic surfaces upon unfolding. As a result, we could not reliably assess ligand binding to MtbClpX-NTD using this method.

ILE significantly impedes the proteolytic function of the ClpC1P1P2 and ClpXP1P2 proteases

Considering the stronger interactions observed between MtbClpC1-NTD and ILE compared to ILF, we focused our subsequent biochemical assays on evaluating ILE. We observed that ILE inhibited the proteolysis of the model substrate, fluorescein isothiocyanate-casein (FITC-casein), by ClpC1wtP1P2 complex compared to the control group (Fig. 6a). However, the proteolytic activities of multiple mutant ClpC1P1P2 proteases remain unaffected at 10 µg mL−1 ILE compared to the control, with only partial inhibition noted at 20 µg mL−1 ILE (Fig. 6b–e).

Degradation of FITC-casein by a ClpC1wtP1P2, b ClpC1F80IP1P2, c ClpC1F80LP1P2, d ClpC1F80VP1P2, and e ClpC1F80CP1P2 proteases in the presence or absence of ILE. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three technical replicates (n = 3). f Degradation of GFP-DAS+4 by ClpXwtP1P2 proteases in the presence or absence of ILE. Panel (f) shows data from a representative experiment without error bars. Numbers following the drug names indicate the working concentrations (µg mL−1). DMSO was added as control. The D-value of fluorescence intensity represents the change in fluorescence intensity by subtracting the initial fluorescence intensity from the fluorescence intensity of subsequent detections. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0001; ****P < 0.00001; ns no significant difference, where P ≥ 0.05.

For the ClpXP1P2 proteasome, we first used ssrA tagged green florescent protein (GFP-ssrA) as the substrate. The results showed that even when the concentrations of ILE or ILF reached as high as 2000 µg mL−1, no inhibition of ClpXP1P2-mediated proteolytic activity was observed (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Previous studies have demonstrated that the adapter protein SspB from Escherichia coli (E. coli) is required for efficient degradation of proteins tagged with a mutated form of the ssrA tag DAS+4 by ClpXP1P2 in both E. coli and Msm43,44. Therefore, we expressed GFP tagged with DAS+4 (GFP-DAS+4) as the substrate and SspB as the adapter. Importantly, when using DAS+4-tagged substrates, protein degradation could only be observed in the presence of the adapter SspB (Supplementary Fig. 5c). A significant inhibition of the proteolytic activity of the ClpXwtP1P2 complex was observed during the hydrolysis of GFP-DAS+4 in the presence of SspB when ILE is added (Fig. 6 f). However, we discovered that the mutant ClpXP30HP1P2 complex was incapable of degrading GFP-DAS+ 4 (Supplementary Fig. 5d).

Additionally, we noted that ILE did not impact the ATP-dependent enzymatic activities of ClpC1 and ClpX, as no significant differences in ATPase activities were detected across varying ILE concentrations compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 6).

ILE disrupts protein homeostasis with accumulation of ribosomal components and toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems

To elucidate the adaptive responses of Mtb to ILE and gain insight into its MOAs, we performed quantitative proteomic analysis of Mtb cells treated with ILE (Supplementary Data 3). Compared to untreated controls, a total of 773 proteins were upregulated and 280 proteins were downregulated (Fig. 7a), indicating a global increase in protein abundance.

Notably, ribosomal proteins—including components of the 50S and 30S subunits (e.g., RpsG, RpsS)—were broadly upregulated, with 21 out of 23 ribosomal proteins showing increased abundance. RplR and RpsC were the only ribosomal proteins found to be downregulated.

All differentially expressed TA system proteins were upregulated, including proteins from VapBC (27 proteins), MazEF (11 proteins), ParDE/RelBE (7 proteins), HigBA (3 proteins) and mt-PemIK (1 protein) families. Additionally, the reported ClpP1P2 substrates PanD (fold change (FC) = 2.67, P < 0.05) and CarD (FC = 5.99, P < 0.001) were also significantly upregulated45,46. Proteins associated with cell division, such as FtsZ and FtsE, were upregulated approximately two-fold (P < 0.001), consistent with scanning electron microscopy observations.

To visualize changes in proteins functionally related to the Clp protease system, key components including ClpX, ClpS, and ClgR were highlighted in the volcano plot (Fig. 7b). ClpX was downregulated (FC = 0.41, P < 0.05), whereas ClpS and ClgR were highly upregulated (FC = 187.26 and 8.53, respectively; both P < 0.01). Other components such as ClpC1, ClpC2, ClpP1, and ClpP2 showed no significant changes and were therefore not highlighted.

Discussion

The study of natural cyclic peptides has emerged as a focal point in the current research on anti-Mtb drugs. Our results demonstrate that ILE exhibits superior activity against Mtb compared to reported cycloheptapeptides, achieving an MIC of 48 nM (0.05 µg mL−1) by day 15 (Fig. 1a), which is lower than those of RUFI (60 nM), CYMA (100 nM), ECU (160 nM), and lassomycin (410 nM)13,18,47. While these compounds exhibit activities against NTM, only RUFI and ILE showed appreciable efficacy against Mab, indicating their potential as therapeutic agents for diseases caused by Mab15. The observed divergence in efficacy, particularly between ILE and its structurally related analog ILF, may reflect differences in compound structure as well as species variations in cell wall permeability48,49.

Previous research had not explored the combination effects of cycloheptapeptides with anti-TB drugs, leaving their potential as adjuvants to current TB therapies unresolved14,15,16,18. Notably, our findings on combinatorial activity suggest that ILE has the potential to enhance the efficacy of existing anti-TB drugs, including RIF, INH, EMB, and TB47. Proteomic analysis provided mechanistic insights into these interactions, revealing that ILE treatment modulated the expression of multiple proteins involved in pathways targeted by these drugs. As for RIF, ILE induced downregulation of Rho and NusA, two key transcriptional regulators that interact with RNA polymerase. Given that Rho suppression causes widespread transcriptional disruption and rapid cell death, and that NusA modulates transcriptional pausing and termination, their downregulation may sensitize Mtb to RIF-induced RNA polymerase inhibition50,51. In the case of INH, four proteins—SigL, Ndh, FadE24, and Glf—were differentially expressed in response to ILE. Specifically, SigL and Ndh were significantly upregulated, whereas FadE24 and Glf were downregulated. SigL has been reported to regulate the expression of KatG, which is crucial for the activation of INH, and Ndh has been discovered influencing the NADH/NAD+ ratio, affecting INH-NAD formation52,53,54. INH-resistant Mtb has been found to carry mutations in FadE2455. Upregulation of Glf was hypothesized to contribute to INH resistance in Mtb either by binding to a modified form of INH or by sequestering a factor such as NAD+ required for INH activity56. For EMB, ILE downregulated UbiA, a key enzyme in the decaprenylphosphoryl-D-arabinose biosynthesis pathway required for cell wall assembly. Given that UbiA overexpression has been associated with EMB resistance, its suppression by ILE may underlie the observed partial synergy57. Additionally, synergy with TB47—a cytochrome bc1 complex (QcrB) inhibitor—can be explained by ILE-mediated suppression of several electron transport chain components, including QcrA, QcrC, and CydD24,58. As the Qcr and Cyt-bd branches of the electron transport chain are functionally redundant, simultaneous inhibition by TB47 and ILE likely causes a collapse in respiratory function, resulting in pronounced synergistic killing24.

Although ILE and ILF have demonstrated potent activity against Mtb, their MOAs have remained elusive17. Previous studies had identified ClpC1 as the primary target of several cyclic peptides30. Consistent with this, we found that mutations in ClpC1—particularly in its NTD—confer resistance to ILE and ILF across multiple mycobacterial species, with the exception of unique insertion mutations discovered between M1 and F2 in both Mab and Msm15,16,18,35. Previous studies indirectly validated these mutations via overexpression35, but using advanced mycobacterial gene-editing tools, we now directly confirm that specific mutations (e.g., Mab-F2L, Msm-F2C, and a novel Msm insertion) confer ILE/ILF resistance. Additionally, WGS of 2 ILE-resistant Mtb mutants revealed identical large insertions in Rv1572, a conserved hypothetical protein whose role remains to be explored. Moreover, 3 ILE-resistant Mab mutants were found to carry mutations in hisS or hisD, which encode histidyl-tRNA synthetase and histidinol dehydrogenase, respectively. Although overexpression of mutated versions of these genes did not restore drug sensitivity, gene editing-based validation is planned to confirm their potential role in resistance.

Interestingly, no ClpX mutations had been reported in mutants resistant to these compounds15,16,18. However, our findings indicate that ILE-resistant mutants harboring ClpX mutations also exhibit cross-resistance to ILF, suggesting a shared resistance mechanism. Moreover, gene editing confirmed that ClpX mutations can directly confer high-level resistance to both ILE and ILF, revealing ClpX as a novel contributor to cyclic peptide resistance. These findings also shed light on possible limitations of previous resistance screening approaches. Whether the ClpX mutation can lead to resistance in mycobacteria to other ClpC1-targeting cyclic peptides—such as RUFI, ECU, and lassomycin—remains to be determined. Given RUFI’s close structural similarity to ILE/ILF and strong activity against Mab, this is particularly worth investigating15,59. Molecular docking and gene editing techniques provide effective strategies to explore this possibility.

The MOA of ILE differs from ECU and lassomycin, which stimulate ClpC1 ATPase activity but hinder substrate degradation, as well as CYMA, which activates both ATPase and proteolytic functions16,18,35. In this study, we demonstrated that ILE and ILF inhibited the proteolytic activity of both ClpC1P1P2 and ClpXP1P2 proteases without affecting ATPase activity, which is similar to RUFI’s mechanism15. Notably, a higher concentration of ILE is required to inhibit ClpXP1P2 than ClpC1P1P2, aligning with the higher resistance levels associated with ClpX mutation. These observations highlight ClpX mutation as a previously unrecognized resistance mechanism in mycobacteria, warranting further investigation.

Proteomic analysis further revealed a broad upregulation of proteins in response to ILE treatment, consistent with a disruption of proteostasis resulting from ClpC1 and ClpX inhibition. Impaired protease activity would prevent normal turnover of these proteins, resulting in their accumulation. This may explain the observed increase in ribosomal protein levels as a compensatory response to maintain translational capacity. Notably, multiple TA systems—including VapBC, MazEF, ParDE/RelBE, HigBA, and mt-PemIK families—were strongly upregulated, aligning with their known degradation by ClpC1P1P2 or ClpXP1P29,60. Given their roles in growth modulation, dormancy, and virulence, such dysregulation could contribute to the antibacterial effects of ILE treatment61. Additionally, accumulation of PanD and CarD, two validated ClpP1P2 substrates, further supports protease inhibition45,46. ClpX was downregulated, potentially relieving repression of FtsZ and explaining its upregulation39. This is consistent with previous reports that ClpX knockdown leads to filamentous cell morphology due to disrupted FtsZ regulation in mycobacteria40, and may explain the elongated cells we observed under SEM in ILE/ILF-treated strains. ClpS was dramatically induced, likely to compensate for impaired substrate recognition60. The transcriptional activator ClgR was upregulated, consistent with proteostasis stress responses observed under proteasome inhibition62. These findings indicate a coordinated regulatory response aimed at restoring protein homeostasis under Clp protease dysfunction.

However, we discovered that the mutant ClpXP30HP1P2 complex was incapable of degrading GFP-DAS+4. This may be due to the requirement of an intact zinc binding domain (ZBD) in ClpX (residues 1–60) for SspB to enhance ClpXP1P2 degradation63. A mutation in P30, which is located on the hydrophobic surface of ZBD, may suppress the binding of SspB to ClpX, thereby preventing the delivery of the tagged protein to ClpXP1P2 complexes for degradation. Although SspB homologs have not been identified in mycobacterium, it is possible that native adapter-like mechanisms exist, and disruption of such interactions may contribute to ILE resistance. Notably, despite the presence of ClpC1wt, the ClpXP30H mutation confers resistance, suggesting that it may compensate for ClpC1 dysfunction by altering substrate specificity or proteostasis regulation. Additionally, the roles of some clpC1 mutation sites in ILE and ILF resistance remain unproven because the corresponding gene-edited strains could not be obtained. Therefore, further studies are needed to identify native ClpX substrates or adapters in mycobacteria, assess ClpX mutant proteolytic activity in more physiological contexts, and to obtain the remaining clpC1-edited strains to confirm their roles in ILE and ILF resistance.

While ClpX is not currently considered the target of ilamycins in Mtb, its presence in humans—unlike ClpC1—raises concerns about potential off-target effects. Therefore, we performed sequence analysis, which shows low similarity (36% identity) and no conservation at resistance-related residues between human and Mtb-ClpX-NTD, suggesting minimal risk. However, further validation is warranted to fully exclude off-target interactions.

In summary, the potent and broad antimycobacterial activities of ILE and ILF underscore their potential for further development as effective agents against mycobacteria, especially drug-resistant strains. Our findings not only reinforce the critical role of the ClpC1P1P2 protease as a validated target, but also uncover ClpX—via mutation—as a previously unrecognized mechanism of resistance15,16,18,35. This discovery significantly expands the current understanding of resistance pathways beyond clpC1, and suggests that ClpXP1P2 itself represents a promising and underexplored target for antimycobacterial therapy. A dual-targeting strategy that affects both Clp complexes simultaneously is a rational approach, providing a new avenue for developing treatments against mycobacterial infections.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Mtb, Mab, Mmr, Msm, and derived strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (BD, USA) or 7H10 agar (BD) or 7H11 agar (Acmec, China) supplemented with OADC (comprising 0.005% oleic acid, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% dextrose, 0.085% catalase). Mtb, Msm, and Mab were grown at 37°C. Mmr was grown at 30°C. For E. coli, Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C. Antibiotics were supplemented as required at the appropriate screening concentrations for distinct bacterial species. Specifically, for E. coli and Msm, the antibiotics added were kanamycin (KAN, 50 µg mL−1, Solarbio, China), apramycin (APR, 50 µg mL−1, MeilunBio, China), and Zeocin (ZEO, 30 µg mL−1, InvivoGen, France). For Mmr, only APR (50 µg mL−1) was utilized. Meanwhile, for Mab, KAN was used at a higher concentration of 100 µg mL−1, along with ZEO (30 µg mL−1) and an increased concentration of APR (230 µg mL−1).

Determination of MICs and MBC against mycobacteria in vitro and ex vivo

The MICs of ILE and ILF were determined using a cost-effective luminescence-based in vitro assay against selectable marker-free strains AlRa, AlRv, AlMab, AlMsm and AlMmr23,24,25,26. Briefly, strains were cultured in 7H9 medium to mid-log phase, diluted to ~105 RLUs mL−1, and exposed to serial dilutions of ILE or ILF in 96-well plates. After incubation (temperature and time depending on species), RLUs were measured using EnVision multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer, USA). The MIClux is defined as the lowest concentration that could inhibit > 90% RLUs compared with that from the untreated controls23,24,25,26.

For Mtb H37Ra, H37Rv, and nine clinical Mtb isolates collected from TB patients at Guangzhou Chest Hospital, MICs of ILE were determined by a well-established microplate alamar blue assay (MABA)28. In brief, strains were cultured in 7H9 medium to mid-log phase, diluted to ~105 CFU mL−1. The diluted bacteria were then exposed to serial dilutions of ILE in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 12 days. After incubation, 32.5 µL of a freshly prepared alamar blue detection reagent (a mixture of 20 µL Alamar Blue dye (Bio-Rad, USA) and 12.5 µL of 20% Tween 80) was added to each well and incubated for an additional 24 h. The MIC, as determined by the MABA method, is defined as the lowest concentration that prevents the color change from blue to pink, as observed with the naked eye.

MBC is defined as the minimum concentration resulting in ≥ 99.9% reduction in CFUs compared to the bacterial load before drug addition. For CFU enumeration, mycobacterial cultures treated with different concentrations of compounds or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Xilong Chemical, China) were collected before or after incubation, with the incubation time varying depending on species. Bacterial suspensions were serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, GENOM, China), plated onto 7H10 agar plates, and incubated at 37°C until visible colonies appeared. The number of visible colonies was counted, and CFUs were calculated to evaluate bacterial viability.

The intracellular survival assay was performed as previously reported64. RAW264.7 macrophages were seeded at 5 × 10⁴ cells per well in 12-well plates and infected with different Mab strains at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 for 4 h. After removing extracellular bacteria with 250 µg mL−1 amikacin (MeilunBio, China) for 2 h, infected cells were cultured with or without ilamycins and 200 ng mL−1 aTc (Macklin, China). At 72 h post-infection, macrophages were lysed, and intracellular bacteria were quantified by CFU enumeration on 7H10 agar. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Determination of MICs against non-mycobacteria

The MICs of ILE or ILF against Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were determined using the broth microdilution method in LB broth65,66,67. After 16 h of incubation at 37°C, MICs were defined as the lowest concentration that prevents visible turbidity compared to the untreated control cultures.

Evaluation of in vitro combined activity of ILE or ILF with other compounds

The combined activity of ILE or ILF with other compounds, including INH (MeilunBio, China), RIF (MeilunBio, China), EMB (MeilunBio, China), STR (MeilunBio, China), CFZ (MeilunBio, China), or BDQ (biochempartner, China), and TB47 (BojiMed, China), were evaluated in vitro using the checkerboard method68,69. Briefly, serial twofold dilutions of ILE or ILF were prepared along one axis of the plate, while serial dilutions of the partner drug were prepared along the other axis. After inoculation with bacterial suspensions (final concentration ~105 RLUs mL−1) and incubation at 37°C for 12 days, MICs of both drugs were assessed by luminescence measurement. The FICI was calculated as follows: FICI = FICₐ + FICb, where FICₐ = MIC of drug A in combination/MIC of drug A alone, and FICb = MIC of drug B in combination/MIC of drug B alone. Interactions are interpreted as follows: synergistic (FICI ≤ 0.5), partially synergistic (0.5 < FICI < 1.0), additive (FICI = 1.0), indifferent (1.0 < FICI ≤ 4.0), and antagonistic (FICI > 4.0).

Determination of MICs and TC50 in macrophage culture

The cell density of murine macrophages RAW264.7 was adjusted to 5 × 105 cells mL−1. 100 μL of cell suspension was added per well and cultured overnight for adherence. The AlRv concentration was adjusted to 3 × 106 RLU mL−1, and 100 μL of AlRv was added to each well. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 6 h. The cells were washed three times with DMEM (Gibco, USA) to remove non-phagocytosed AlRv and treated with DMEM containing 100 µg mL−1 amikacin for 2 h to eliminate the extracellular bacteria. The cells were washed twice with DMEM to remove residual amikacin. A total of 195 μL of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 5 μL of the two-fold dilutions of various ILE concentrations were added to the cells. The mixture was incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2, and the RLUs were measured on days 1–5 or 7 of incubation. RIF (1 µg mL−1) and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

The TC50 of ILE was assessed in murine RAW264.7 macrophages using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, MeilunBio, China). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and allowed to adhere overnight. Serial dilutions of ILE were added and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. CCK-8 reagent was then added according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The TC50 value was calculated from dose–response curves using GraphPad Prism version 8.3.0.

Screening of ILE- or ILF-resistant mutants

Broth cultures of AlRa, AlRv, AlMab, and AlMmr, with OD600 of 0.6–1.3, were plated on 7H11 plates containing ILE at 0.1, 0.5, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20 μg mL−1. Broth cultures of AlMsm (OD600 of 0.6–1.3) were plated on 7H11 plates containing ILF at 10, 20 or 40 µg mL−1. The bacterial colonies from the ILE- or ILF-containing plates were selected and cultured in liquid culture for drug susceptibility testing to confirm the drug resistance phenotype.

WGS analysis

WGS analysis was conducted on the parent strains of Mtb, Mab, and a subset of the confirmed ILE-resistant mutants. The sequencing was performed by the Beijing Genomics Institute in China. Subsequently, the obtained reads were aligned with the reference genome sequence and compared to that of the parent strain. Mutations identified through WGS in the drug-resistant mutants were validated by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of clpX and clpC1 genes. Additionally, the clpX and clpC1 genes from other ILE- or ILF-resistant mutants, including Mtb, Mab, Msm, and Mmr, were PCR amplified and sequenced by Sanger sequencing (primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 3).

Molecular docking analysis

To evaluate the binding affinities and interaction modes of ILE with MtbClpC1-NTD and MtbClpX-NTD, we employed Autodock Vina 1.2.2, a computational protein-ligand docking software previously reported31. The structure of ILE was obtained from PubChem32. The 3D coordinates of MtbClpC1-NTD were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with PDB code 6CN8 and a resolution of 1.4 Å, while the structure of MtbClpX-NTD was predicted using AlphaFold2.

For the docking analysis, all protein and ligand files were converted to the PDBQT format; water molecules were excluded, and polar hydrogen atoms were supplemented. A grid box was positioned to envelop the domain of each protein, facilitating unrestricted molecular movement. The dimensions of the grid box were set to 30 Å × 30 Å × 30 Å, with a grid point spacing of 0.05 nm. The molecular docking experiments were executed using Autodock Vina 1.2.2, which is available at http://autodock.scripps.edu/.

Overexpression of clpX or clpC1 in Mab, Mmr or Msm

The clpC1wt, clpC1mt, clpXwt and clpXmt from Mtb, Mab, Mmr and Msm were amplified using primers detailed in Supplementary Table 3 and subsequently cloned into the multi-copy plasmid p60A33 or pMVA34 under the control of the hsp60 promoter. The plasmids were then transformed into AlMab, AlMmr, and AlMsm. Additionally, the clpP1, clpP2 and either clpX or clpC1 of Mab were amplified from the genome of Mabwt and inserted into the plasmid pMVA under the control of the hsp70 or hsp60 promoters to enable the simultaneous expression of ClpXP1P2 or ClpC1P1P2. The MICs of ILE or ILF against recombinant strains were determined using the aforementioned protocols.

Silencing clpX or clpC1 genes in Mab or Msm

The CRISPR-Cas9 system was employed for targeted gene silencing of clpX and clpC141. Small guide RNAs (sgRNAs) of 20 nucleotides were designed to target the coding regions of clpX and clpC1 on their sense strands. The oligonucleotides were annealed and then ligated with linearized pLJR96241. Plasmids harboring sgRNAs against clpX or clpC1, along with the empty vector pLJR962 as a control, were transformed into Mab and Msm cells via electroporation (Supplementary Table 4).

Tenfold serial dilutions of Mabwt or Msmwt, the control strain carrying the empty vector, and the gene-silenced strains were prepared after reaching an OD600 of approximately 0.9. For Mab, 1 μL of each dilution was spotted on plates containing 0.25, 0.5, and 1 µg mL−1 ILE or 5, 10, and 20 µg mL−1 ILF with varying concentrations of aTc (0, 100, 200 and 400 ng mL−1). For Msm, 1 μL of each dilution was spotted on plates containing 0.004, 0.008, and 0.01625 µg mL−1 ILE or 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 µg mL−1 ILF with varying concentrations of aTc (0, 12.5, 25 and 50 ng mL−1). Control plates were spotted with 1 μL of each dilution with aTc alone. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 days. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

CRISPR/Cpf1-mediated gene editing of clpX and clpC1 genes in Mab and Msm

CRISPR/Cpf1-associated recombination has been previously employed for gene editing in both Mab and Msm recently37,38. Initially, the pJV53-Cpf1 plasmid was electroporated into Mabwt and Msmwt strains, resulting in the Mab::pJV53-Cpf1 and Msm::pJV53-Cpf1, respectively. Subsequently, crRNAs were designed to target specific 25-nucleotide sequences adjacent to the 5’-YTN-3’ motif on the template strand of the target genes (Supplementary Table 4). Oligonucleotides for crRNA expression were ligated into the pCR-zeo vector. These constructed vectors were then electroporated into acetamide-induced cells of Mab::pJV53-Cpf1 or Msm::pJV53-Cpf1, respectively. To induce Cpf1 expression, aTc (200 ng mL−1) was added to 7H11 agar plates. These plates were cultured at 30°C for 3–5 days. Individual colonies were picked and sequenced by Sanger sequencing to confirm successful editing at the target gene site (primers listed in Supplementary Table 3). The MICs of ILE and ILF against edited strains were determined using the methods described earlier.

Expression and purification of proteins

The Mtb ClpP1 (residues 7–200) with a C-terminal Strep-II tag and ClpP2 (residues 13–214) with a C-terminal His6-tag were expressed and purified. Briefly, clpP1 and clpP2 genes were inserted into the pETDute-1 vector and expressed in E. coli BL21 (λDE3) in LB broth at 25°C, following induction with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Macklin, China) for ~16 h. Cells were resuspended and lysed. The target protein was subsequently purified via nickel affinity chromatography and eluted with the same buffer supplemented with 200 mM imidazole. Eluted fractions containing the target protein were loaded onto a Strep-II column. The target protein was eluted with the strep buffer containing 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM d-Desthiobiotin and 10% glycerol (v/v), before a final gel filtration using a SuperoseTM 6 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) in SEC buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2).

The sequence of clpXwt or clpXP30H was inserted into the pGEX-6P-1 vector, which had a His6-tag at the C terminus and an HRV 3C protease cleavage site. After induction for 18 h at 16°C, the cells were collected by centrifugation. The pellet was then resuspended and lysed. After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto a GST column and eluted. The eluent underwent digestion at 4°C for 26 h with sufficient HRV 3C protease. The fractions containing the target protein were then pooled, concentrated to 1 mL, and purified with a SuperoseTM 6 increase 10/300 GL column.

The sequence of clpC1wt, its mutants (F80I/V/L/C), the genes encoding gfp-ssrA (AADSHQRDYALAA), gfp-DAS+4 (AANDENYSENYADAS) or E. coli sspB were inserted into the pET-28a vector that had an N-terminal His6-tag. The recombinant strains were cultured in LB broth at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. After 18 h of induction with 0.5 mM IPTG at 18°C, the pellet was resuspended and lysed. Following the loading of the supernatant onto a Ni-NTA column, the proteins were washed and then eluted. The fractions were then pooled and loaded onto a SuperoseTM 6 increase 10/300 GL column.

The gene encoding MtbClpC1-NTDwt/mt or MtbClpX-NTDwt/mt was inserted into the pET-28a vector with a C-terminal His6-tag and an HRV 3C protease cleavage site. The expression and purification methods of MtbClpC1-NTD and MtbClpX-NTD were consistent with the methods described above.

DSF

The binding of ILE or ILF to the MtbClpC1-NTD and MtbClpX-NTD was detected using DSF, following established protocols42,70. A 5 µM solution of either MtbClpXwt/mt-NTD or MtbClpC1wt/mt-NTD was incubated with varying concentrations of ILE or ILF (ranging from 10 to 400 µM), as well as DMSO for 30 minutes (min), subsequently mixed with Sypro Orange fluorescent dye (Invitrogen, USA). Fluorescence measurements were recorded using the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-rad, USA), using 8-tube PCR strips heated from 25°C to 95°C at a constant rate of 0.4°C per min. The excitation and emission wavelengths were set at 460 nm and 510 nm, respectively. Data collection was facilitated by the CFX Manager software, with analysis performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.3.0. To ensure accuracy, all measurements were performed in triplicate.

Proteolytic activity assays of ClpC1P1P2 and ClpXP1P2

The proteolytic activities of ClpC1wt/mtP1P2 and ClpXwt/mtP1P2 were measured at 37°C in black 96-well plates using a Multimode Plate Reader. For the ClpC1P1P2 proteolytic activity experiments, ILE was added at final concentrations of 0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 20 μg mL−1 in each well. A 100 µL reaction mixture was prepared with 2 µM ClpP1P2, 1 µM ClpC1wt/mt, 2 mM ATP, and 2.5 µM FITC-casein (AAT Bioquest, USA).

For the ClpXP1P2 proteolytic activity experiments, two different ssrA-tagged GFP substrates were used: GFP-ssrA and the mutated ssrA-tagged GFP (GFP-DAS+4). For the GFP-ssrA substrate, the reaction mixture (100 µL) contained 0.2 µM ClpP1P2, 0.7 µM ClpX, 2 mM ATP, 1 µM GFP-ssrA, and 7 µM bortezomib (AbMole, USA) as an activator71. For the DAS+4-tagged substrate, GFP-ssrA was replaced with 1 µM GFP-DAS+4, and 2 µM SspB adapter protein was added.

The hydrolysis of FITC-casein, GFP-ssrA, and GFP-DAS+4 was continuously monitored at 535 nm (with excitation at 485 nm). Measurements were performed in triplicate.

ATPase activity assays of ClpC1 and ClpX

The ATPase activities of Mtb ClpC1 and ClpX were assessed using Biomol Green phosphate detection assay (Enzo Life Sciences, USA). To each well, 5 μL of ILE at varying concentrations (0, 0.08, 0.16, 0.31, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 μg mL−1) was added. Subsequently, either ClpX or ClpC1 was diluted to a concentration of 0.1 μg mL−1 in the reaction mixture. 90 μL ClpC1 or ClpX were then added to a 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was initiated by adding 5 μL of 1 mM ATP to the reaction mixture, which was maintained at 37°C for 1 h. The final volume of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 100 µL. After the reaction, 100 μL of Biomol Green reagent was introduced to determine the amount of free phosphate. After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, the resulting reaction product was measured at 620 nm using a Multimode Plate Reader. The concentration of free phosphate liberated from ATP by ClpX and ClpC1 was calculated using a standard curve based on the known concentration of free phosphate. Measurements were performed in triplicate.

Microscopy of drug-treated Msm

Treatment of exponentially growing Msm was conducted using 0.125 μg mL−1 ILE, 5 μg mL−1 L ILF, or 1 μg mL−1 CLR (Meilunbio, China) for a duration of 15 h. The bacteria were fixed with a 4% glutaraldehyde solution, washed three times and resuspended with PBS. Bacterial suspensions were then applied to 5 mm cell slides, which were placed in a 24-well plate to dry naturally. Afterward, the cell slides underwent three additional PBS washes. The cell slides were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (70%, 80%, 90%, 100%) for 10 min each. Finally, the cell slides were dried using the critical point drying method, then coated with an electrically-conducting material. Observations of bacterial morphology were made using a GeminiSEM 300 ultra-high resolution field emission cryo-scanning electron microscope.

Proteomic analysis

The AlRa cells were treated with 0.0125 μg mL−1 of ILE for 5 days in triplicate for a 4D label-free phosphoproteomic analysis. To maintain comparable cell density, the untreated cells were diluted on the same day ILE was added, prior to sample collection. The cells were resuspended and boiled for 20 min. Subsequently, the samples were sent to APTBIO (Shanghai, China) for proteomic testing and analysis.

To compare the abundance of phosphopeptides between the control and treatment samples, label-free quantification was performed with a minimum FC of 2 to determine the differentially expressed phosphopeptides. Additionally, the Student’s t test was employed to detect significant differences between the control and treatment samples, with P < 0.05 indicating significance. Protein functional annotation was conducted using NCBI and Mycobrowser (https://mycobrowser.epfl.ch/). All differentially expressed proteins were listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.3.0). For comparisons between two groups, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests were used. For comparisons involving more than two groups, one-way or two-way ANOVA with appropriate post hoc tests (as indicated in figure legends) was applied. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All quantitative experiments were conducted with two or three technical replicates. Technical replicates refer to multiple wells or plates derived from the same biological sample processed in parallel. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of technical replicates. Each experiment was independently repeated at least twice to ensure reproducibility, and similar trends were observed. For experiments where statistical analyses were not applied, results were consistent across independent repetitions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Sequence Read Archive (SRA) for a subset of ILE-resistant Mab strains has been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject PRJNA1262689. Sanger sequencing results of clpC1 from ILE-resistant Mmr and ILF-resistant Msm spontaneous mutants have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PV937066–PV937076. Sequencing results of the target gene regions from CRISPR-edited Msm and Mab strains are available under GenBank accession numbers PV962123–PV962127. Original proteomics data are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD066355. Variant analysis results for the remaining samples, as provided by the sequencing company, are included in Supplementary Data 1 and 2. Processed proteomics data supporting the differential expression analysis of ILE-treated Mtb H37Ra are provided in Supplementary Data 3. Source data for all graphs are available in Supplementary Data 4. All other relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Miotto, P., Zhang, Y., Cirillo, D. M. & Yam, W. C. Drug resistance mechanisms and drug susceptibility testing for tuberculosis. Respirology 23, 1098–1113 (2018).

Dheda, K. et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 10, 22 (2024).

Fedrizzi, T. et al. Genomic characterization of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Sci. Rep. 7, 45258 (2017).

Wu, M.-L., Aziz, D. B., Dartois, V. & Dick, T. NTM drug discovery: status, gaps and the way forward. Drug Discov. Today 23, 1502–1519 (2018).

Lee, H. & Suh, J. W. Anti-tuberculosis lead molecules from natural products targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpC1. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 43, 205–212 (2016).

Lupoli, T. J., Vaubourgeix, J., Burns-Huang, K. & Gold, B. Targeting the proteostasis network for mycobacterial drug discovery. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 478–498 (2018).

Fraga, H. et al. Development of high throughput screening methods for inhibitors of ClpC1P1P2 from Mycobacteria tuberculosis. Anal. Biochem. 567, 30–37 (2019).

d’Andrea, F. B. et al. The essential M. tuberculosis Clp protease is functionally asymmetric in vivo. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn7943 (2022).

Texier, P. et al. ClpXP-mediated degradation of the TAC antitoxin is neutralized by the SecB-like chaperone in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 166815 (2021).

Akopian, T. et al. The active ClpP protease from M. tuberculosis is a complex composed of a heptameric ClpP1 and a ClpP2 ring. EMBO J. 31, 1529–1541 (2012).

Raju, R. M. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpP1 and ClpP2 function together in protein degradation and are required for viability in vitro and during infection. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002511 (2012).

Sassetti, C. M., Boyd, D. H. & Rubin, E. J. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 77–84 (2003).

Boshoff, H. I., Malhotra, N., Barry, C. E. III & Oh, S. The antitubercular activities of natural products with fused-nitrogen-containing heterocycles. Pharmaceuticals 17, 211 (2024).

Schmitt, E. K. et al. The natural product cyclomarin kills Mycobacterium tuberculosis by targeting the ClpC1 subunit of the caseinolytic protease. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 5889–5891 (2011).

Choules, M. P. et al. Rufomycin targets ClpC1 proteolysis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e02204–e02218 (2019).

Gao, W. et al. The cyclic peptide ecumicin targeting ClpC1 is active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 880–889 (2015).

Ma, J. et al. Biosynthesis of ilamycins featuring unusual building blocks and engineered production of enhanced anti-tuberculosis agents. Nat. Commun. 8, 391 (2017).

Gavrish, E. et al. Lassomycin, a ribosomally synthesized cyclic peptide, kills Mycobacterium tuberculosis by targeting the ATP-dependent protease ClpC1P1P2. Chem. Biol. 21, 509–518 (2014).

Victoria, L., Gupta, A., Gómez, J. L. & Robledo, J. Mycobacterium abscessus complex: a review of recent developments in an emerging pathogen. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 659997 (2021).

Luthra, S., Rominski, A. & Sander, P. The role of antibiotic-target-modifying and antibiotic-modifying enzymes in Mycobacterium abscessus drug resistance. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2179 (2018).

Stinear, T. P. et al. Insights from the complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium marinum on the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 18, 729–741 (2008).

Shiloh, M. U. & Champion, P. A. D. To catch a killer. What can mycobacterial models teach us about Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis?. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 86–92 (2010).

Yang, F. et al. Engineering more stable, selectable marker-free autoluminescent mycobacteria by one step. PLoS ONE 10, e0119341 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. The compound TB47 is highly bactericidal against Mycobacterium ulcerans in a Buruli ulcer mouse model. Nat. Commun. 10, 524 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Assessment of clofazimine and TB47 combination activity against Mycobacterium abscessus using a bioluminescent approach. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e01881–01819 (2020).

Zhang, T., Li, S. Y. & Nuermberger, E. L. Autoluminescent Mycobacterium tuberculosis for rapid, real-time, non-invasive assessment of drug and vaccine efficacy. PLoS ONE 7, e29774 (2012).

Zhang, M., Gong, J., Lin, Y. & Barnes, P. F. Growth of virulent and avirulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 66, 794–799 (1998).

Lu, X. Y. et al. Pyrazolo[1,5-]pyridine inhibitor of the respiratory cytochrome complex for the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 5, 239–249 (2019).

Bergval, I. et al. Pre-existing isoniazid resistance, but not the genotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drives rifampicin resistance codon preference in vitro. PLoS ONE 7, e29108 (2012).

Wolf, N. M. et al. High-resolution structure of ClpC1-rufomycin and ligand binding studies provide a framework to design and optimize anti-tuberculosis leads. ACS Infect. Dis. 5, 829–840 (2019).

Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 3891–3898 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Pubchem bioassay: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D955–D963 (2017).

Makafe, G. G. et al. Role of the Cys154Arg substitution in ribosomal protein L3 in Oxazolidinone resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 3202–3206 (2016).

Fang, C. et al. GrcC1 mediates low-level resistance to multiple drugs in M. marinum, M. abscessus, and M. smegmatis. Microbiol Spectr. 13, e0228924 (2025).

Vasudevan, D., Rao, S. P. & Noble, C. G. Structural basis of mycobacterial inhibition by cyclomarin A. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 30883–30891 (2013).

Chhotaray, C. et al. Advances in the development of molecular genetic tools for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Genet. Genom. 45, 281–297 (2018).

Yan, M. et al. CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted recombineering in bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e00947–00917 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Amino acid 17 in QRDR of Gyrase A plays a key role in fluoroquinolones susceptibility in mycobacteria. Microbiol Spectr. 11, e0280923 (2023).

Dziedzic, R. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpX interacts with FtsZ and interferes with FtsZ assembly. PLoS ONE 5, e11058 (2010).

Bai, J., Chi, M., Hu, Y., Hao, M. & Zhang, X. Construction and biological characteristics of ClpC and ClpX knock-down strains in Mycobacterium smegmatis. China Biotechnol. 41, 13–22 (2021).

Rock, J. M. et al. Programmable transcriptional repression in mycobacteria using an orthogonal CRISPR interference platform. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 1–9 (2017).

Vivoli, M., Novak, H. R., Littlechild, J. A. & Harmer, N. J. Determination of protein-ligand interactions using differential scanning fluorimetry. J. Vis. Exp. 13, e51809 (2014).

Kim, J. H. et al. Protein inactivation in mycobacteria by controlled proteolysis and its application to deplete the beta subunit of RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2210–2220 (2011).

McGinness, K. E., Baker, T. A. & Sauer, R. T. Engineering controllable protein degradation. Mol. Cell 22, 701–707 (2006).

Gopal, P. et al. Pyrazinamide triggers degradation of its target aspartate decarboxylase. Nat. Commun. 11, 1661 (2020).

Raju, R. M. et al. Post-translational regulation via Clp protease is critical for survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003994 (2014).

Shetye, G. S., Choi, K. B., Kim, C. Y., Franzblau, S. G. & Cho, S. In vitro profiling of antitubercular compounds by rapid, efficient, and nondestructive assays using autoluminescent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 65, e0028221 (2021).

Gutiérrez, A. V., Viljoen, A., Ghigo, E., Herrmann, J.-L. & Kremer, L. Glycopeptidolipids, a double-edged sword of the Mycobacterium abscessus complex. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1145 (2018).

Jankute, M., Grover, S., Birch, H. L. & Besra, G. S. Genetics of mycobacterial arabinogalactan and lipoarabinomannan assembly. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, MGM2–MGM2013 (2014).

Botella, L., Vaubourgeix, J., Livny, J. & Schnappinger, D. Depleting Mycobacterium tuberculosis of the transcription termination factor Rho causes pervasive transcription and rapid death. Nat. Commun. 8, 14731 (2017).

Jin, D. J. et al. Effects of rifampicin resistant rpoB mutations on antitermination and interaction with nusA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 204, 247–261 (1988).

Sklar, J. G., Makinoshima, H., Schneider, J. S. & Glickman, M. S. M. tuberculosis intramembrane protease Rip1 controls transcription through three anti-sigma factor substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 605–617 (2010).

Unissa, A. N., Subbian, S., Hanna, L. E. & Selvakumar, N. Overview on mechanisms of isoniazid action and resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 45, 474–492 (2016).

Hameed, H. A. et al. Molecular targets related drug resistance mechanisms in MDR-, XDR-, and TDR-Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 114 (2018).

Ramaswamy, S. V. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes associated with isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 1241–1250 (2003).

Chen, P. & Bishai, W. R. Novel selection for isoniazid (INH) resistance genes supports a role for NAD+-binding proteins in mycobacterial INH resistance. Infect. Immun. 66, 5099–5106 (1998).

He, L. et al. ubiA (Rv3806c) encoding DPPR synthase involved in cell wall synthesis is associated with ethambutol resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 95, 149–154 (2015).

Gao, Y. et al. Ultra-short-course and intermittent TB47-containing oral regimens produce stable cure against Buruli ulcer in a murine model and prevent the emergence of resistance for Mycobacterium ulcerans. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 11, 738–749 (2021).

Zhou, B. et al. Rufomycins or Ilamycins: naming clarifications and definitive structural assignments. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 2644–2663 (2021).

Ziemski, M., Leodolter, J., Taylor, G., Kerschenmeyer, A. & Weber-Ban, E. Genome-wide interaction screen for Mycobacterium tuberculosis ClpCP protease reveals toxin-antitoxin systems as a major substrate class. FEBS J. 288, 111–126 (2021).

Bordes, P. & Genevaux, P. Control of toxin-antitoxin systems by proteases in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 691399 (2021).

Yamada, Y. & Dick, T. Mycobacterial caseinolytic protease gene regulator ClgR is a substrate of caseinolytic protease. mSphere 2, e00338–00316 (2017).

Thibault, G. et al. Specificity in substrate and cofactor recognition by the N-terminal domain of the chaperone ClpX. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17724–17729 (2006).

Ju, Y. et al. The gene MAB_2362 is responsible for intrinsic resistance to various drugs and virulence in Mycobacterium abscessus by regulating cell division. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 69, e0043324 (2025).

Jiang, H. et al. One-step engineering of a stable, selectable marker-free autoluminescent Acinetobacter baumannii for rapid continuous assessment of drug activity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 29, 1488–1493 (2019).

Tian, X. et al. Rapid visualized assessment of drug efficacy in live mice with a selectable marker-free autoluminescent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biosens. Bioelectron. 177, 112919 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Rapid, serial, non-invasive quantification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in live mice with a selectable marker-free autoluminescent strain. Biosens. Bioelectron. 165, 112396 (2020).

Yu, W. et al. TB47 and clofazimine form a highly synergistic sterilizing block in a second-line regimen for tuberculosis in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 131, 110782 (2020).

Liu, P. et al. Design and synthesis of novel pyrimidine derivatives as potent antitubercular agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 163, 169–182 (2019).

Khadiullina, R. et al. Assessment of thermal stability of mutant p53 proteins via differential scanning fluorimetry. Life13, 31 (2022).

Zhou, B. et al. Structural insights into bortezomib-induced activation of the caseinolytic chaperone-protease system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 16, 3466 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the team of professor Yicheng Sun from the Institute of Pathogenic Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences for kindly sending the pJV53-Cpf1 and pCR-Zeo plasmids as the tool of gene editing. This work was supported by fundings from National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1300900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973372, 32300152, 82022067, 22037006), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M723164), Guangdong Provincial Basic and Applied Basic Research Fund (2022A1515110505, 2019B030302004), Grant of State Key Lab of Respiratory Disease (SKLRD-Z-202414, SKLRD-Z-202301), Open Program of Shenzhen Bay Laboratory (SZBL2021080601006) and Nansha District Science and Technology Plan Project (NSJL202102).The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z., J.J., and X.X. supervised the project; T.Z., Y.G., and C.F. designed the whole project and most of the experiments; J.M. and C.S. prepared and characterized the ilamycin E and ilamycin F; Y.G. and C.F. performed the susceptibility testing and resistant mutant screening; B.Z. and J.J. contributed to molecular docking simulation; C.F., X.T., and J.H. constructed overexpression and gene-editing strains and performed the susceptibility testing; C.F. and X.H. performed the gene-silencing experiments; Y.G. and B.Z. contributed to protein expression and mode of action experiments; C.F. and H.Z. contributed to the microscopy results; Y.G. performed the statistical analysis; Y.G., C.F., and T.Z. wrote the manuscript; H.M.A., J.L., J.M., X.C., N.Z., X.X., J.J., and T.Z. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ranjana Pathania and Mengtan Xing.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Fang, C., Zhou, B. et al. Mutations in ClpC1 or ClpX subunit of caseinolytic protease confer resistance to ilamycins in mycobacteria. Commun Biol 8, 1219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08646-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08646-z