Abstract

Quantum dots (QDs) function as photon sensitizers in photoelectrocatalysis (PEC), enhancing the ability of bulk materials to harness a broad spectrum of photon energy. Through precise engineering, QDs facilitate the development of advanced strategies to synthesize high-performance photoelectrodes that improve the efficiency of light-driven technologies. This review highlights valuable insights in integrating QDs into PEC systems, focusing on heterojunction-mediated charge transfer. We explore their unique optoelectronic properties, the enhancement of conventional photoanodes and photocathodes, and strategies to optimize interfacial charge transfer dynamics for efficient photon-to-energy conversion. Finally, we discuss the advantages, limitations, and future prospects of QD-based PEC technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-quality semiconducting nanocrystals, commonly referred to as quantum dots (QDs), represent a relatively new class of nanomaterials with unique properties. Owing to their nanoscale dimensions—less than 10 nm—their electronic and optical behavior is governed by quantum mechanical effects1,2. When electrons in these materials are confined within a space smaller than the Bohr diameter, their wavefunctions are spatially restricted, which limits their mobility and allows them to store more energy3,4,5. Upon absorbing energy of certain wavelengths, the confined electrons in QDs can hop to discrete energy levels beyond the continuous electronic bands characteristic of bulk photocatalysts. Subsequent recombination or relaxation results in higher energy release compared to that in bulk materials, often as a release of heat—this phenomenon is known as the quantum confinement effect4 (Fig. 1a). A striking feature of this effect is shown in Fig. 1b. When irradiated with UV light, QDs in solution emit fluorescence in a size-dependent manner (as the electron is confined by particle size); smaller QDs emit blue light, whereas larger QDs emit red light1,6,7. This variable photoluminescence, solely due to particle size, has driven widespread interest in QDs for applications in nanostructured materials science and beyond4,5,8,9,10.

a Band structure of a quantum dot (QD). Unlike bulk semiconductors, nanocrystals exhibit discrete energy levels within their bands. When photons excite charge carriers from the lowest energy levels (valence band) to higher energy levels (conduction band), relaxation can result in photoluminescence or charge trapping at surface states. Adapted from ref. 1. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. b Schematic illustration of the quantum confinement effect on the photoluminescence of QDs of different sizes. When a solution of free QDs is exposed to UV light, the emission color depends on nanocrystal size; larger QDs emit red light and smaller QDs blue light.

Since the discovery of QDs in the 1980s by Nobel Laureates A. Ekimov11 and L. Brus12, semiconducting nanocrystals have attracted considerable research attention aimed at synthesizing new structures, understanding their properties, and expanding their application in light-driven technologies. Generally, QD synthesis strategies are categorized as either “top–down” or “bottom–up”. In the top–down approach, bulk materials are broken down into smaller fragments through physical methods, such as exfoliation or ablation, or chemical methods, such as oxidation by strong agents13,14. This route has yielded various carbon-based QDs, including those derived from organic waste15,16. Conversely, bottom–up methods13,17 rely on single-molecule precursors that undergo reaction and growth to form nanocrystals, either homogeneously distributed as a colloidal system freely in solution or precipitated as nanopowders8,18,19,20,21. By strictly controlling reaction conditions and simply adjusting their size to a few hundred atoms, it is possible to obtain QDs with diverse optoelectronic properties, without altering their chemical composition20. Regardless of the synthesis method, high-quality QDs can be obtained with large surface-to-volume ratios, pristine surfaces, tunable absorption and emission edges, and tailored band gaps (Eg).

These physicochemical properties make QDs highly versatile for numerous applications22,23,24,25. Light-driven catalytic technologies are prominent areas where QDs play an important role. Thanks to their tunable band edges, QDs exhibit enhanced charge transfer dynamics in catalytic systems. Acting as light sensitizers—alongside dyes or individual nanoclusters—QDs can absorb a broad spectrum of light, ranging from visible to near-infrared wavelengths. This light harvesting generates high populations of charge carriers in the discrete energy levels of QDs, which can then be transferred across solid interfaces in heterojunction-based systems or used to drive photoredox reactions with species in solution. Photocatalytic applications greatly benefit from the sensitization effects of QDs, enabling a variety of reactions26,27. However, several challenges still need to be addressed, particularly regarding efficient charge separation and transfer. In this sense, photoelectrocatalysis (PEC) has emerged as a promising strategy to overcome some of the limitations of traditional heterogeneous photocatalysis—especially the short lifetime of charge carriers due to rapid recombination. By applying an external bias in PEC systems, the band structures of the involved photocatalysts can be modified, and charge carriers’ recombination is reduced by directing them through an external circuit. Incorporating QDs into bulk photocatalysts has already demonstrated improved light-driven activity. For instance, semiconducting perovskite QDs in solar cells have shown high photoluminescence quantum yields and limited recombination crystal defects28,29,30. Nevertheless, integrating QDs into PEC electrodes presents additional challenges, and their specific roles and behaviors within PEC systems remain subjects of ongoing research.

This review highlights the critical role of QDs in PEC systems, focusing on their photoelectrochemical behavior and its impact on overall performance. Additionally, we examine how QDs facilitate the design of next-generation photoelectrodes with superior light-harvesting ability and efficient charge transfer at solid–liquid interfaces.

QD-based photoelectrodes

A photoelectrode is a light-responsive semiconducting material capable of generating high populations of charge carriers—namely, electron–hole pairs—and limiting their recombination by extracting or injecting them through a circuit under applied external bias. In PEC systems, the photoelectrode plays a central role. Engineering efficient QD-based photoelectrodes requires balancing QD size, shape, and composition with the conductive substrate—and, in certain cases, with layers of bulk photocatalysts—to form solid–solid junctions that facilitate more efficient charge transfer kinetics than simply bulk photocatalysts31,32.

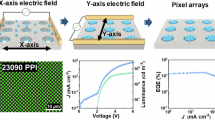

Synthesizing QDs in solution requires rigorous control over reaction conditions and, when necessary, the pursuit of high-performance purification strategies33. However, in PEC applications, freely dispersed QDs are not utilized; instead, they must be integrated onto conductive substrates or incorporated into bulk photoelectrodes (Fig. 2a). The fabrication of these light-active anodes and cathodes is equally as challenging as the synthesis of QDs themselves. Numerous methods for constructing high-performance photoanodes and photocathodes are available in the literature (see refs. 34,35,36), some of which are illustrated in Fig. 2b–d.

a Solution-assisted direct assembly of colloidally synthesized QDs onto a conductive substrate. Reproduced with permission from ref. 5. Copyright 2021, Science. b In situ ligand-stabilized spin-coating deposition of QDs for thin-film photoelectrode fabrication. Reproduced with permission from ref. 29. Copyright 2025, Springer US Nature. c Uniform deposition of monodispersed CsPbBr3-QDs directly on a substrate. Reproduced with permission from ref. 123. Copyright 2022, Springer US Nature. d Common solution-based techniques for preparing high-quality thin-film photoelectrodes. Reproduced with permission from ref. 69. Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

Cadmium chalcogenide QDs (CdE-QDs, E = S, Se, Te) were first synthesized with precise control by Nobel Laureate M. G. Bawendi and coworkers via the hot-injection method20. These nanocrystals can be engineered into core–shell type heterostructures to prevent photocorrosion and increase their lifetimes in both electronic devices and light-assisted technologies1,19,37. CdE-QDs-based photoelectrodes are often prepared using soft chemical solution-assisted techniques, such as the successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) method32,38 (Fig. 2d). In this process, a bare electrode or pre-synthesized photoelectrode is repeatedly dipped into cadmium and chalcogenide precursor solutions, with intermediate rinsing steps in short-chain alcohols to remove excess material after each cycle. This creates a stable layer structure only a few nanometers thick34. These QDs enhance light-harvesting capabilities in photoanodes, facilitating high photocurrents at low overpotentials38. CdS- and CdSe-QDs are commonly used as sensitizers in photoanodes, and transparent conductive substrates allow for straightforward double-sided modifications that improve photon upconversion efficiency. Wang et al.39 demonstrated the co-sensitization of CdS- and CdSe-QDs on a ZnO nanoarray-modified ITO electrode in a tandem-like configuration, modifying both sides to improve light harvesting and achieving up to 45% incident-photon-to-current efficiency (IPCE) at 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl. They demonstrate the advantages of glass-made photoelectrodes, which are easily modified and leverage their transparency to support diverse PEC configurations.

Decorating bulk photocatalysts with pristine QDs is a common strategy to fabricate high-quality photoelectrodes based on semiconductor junctions. Carbon QDs (C-QDs), for example, are often used to decorate TiO2-based photoelectrodes40. These C-QDs are typically synthesized separately and purified to isolate particles of specific sizes and polarities, ensuring they remain stably dispersed in solution and uncontaminated by common fluorophores21,33,41,42. A controlled concentration of C-QDs is mixed with crystalline TiO2 and subjected to thermal treatment to facilitate bonding between both semiconductors. The resulting powder is dispersed in a suitable solvent to create an ink-like suspension, which is then deposited onto clean substrates using techniques like spin-coating (Fig. 2b–c), dip-coating, or electrophoretic deposition to produce the final photoelectrode40 (Fig. 2d). In other cases, QDs grow directly onto nanoarrays of TiO2 synthesized in situ on Ti substrates, forming efficient heterojunctions that enhance charge transport. For instance, Ye et al.43 developed a photocathode comprising TiO2 nanoarrays assembled in a heterojunction with Pd-QDs to efficiently facilitate charge transport from TiO2 to Pd-QDs, which served as catalytic sites for the hydrogen evolution reaction.

Preparing QDs-based photoelectrodes requires extensive investigation into the interfacial surface chemistry of both the QDs material and the substrate. The protective surface chemistries that ensure QDs stability in solution must be effectively reconfigured into robust solid-solid junctions at the electrode–QDs interface. These nanointerfaces dictate charge carrier dynamics, photostability, and interfacial redox processes, collectively defining the reactive matrix in which photoelectrochemical transformations occur. A detailed understanding of such interfaces provides critical insights into charge-transfer pathways, offers opportunities to systematically tailor optical responses, and improves the efficiencies of PEC applications44,45.

QD surface engineering

Colloidally dispersed QDs possess a hybrid interface consisting of charged ionic lattice terminations of the QDs cores, coordinated with organic or inorganic ligands44,46. These ligand species confer QDs stability in diverse solvent environments, impart hydrophilic or hydrophobic characteristics, induce steric and electrostatic repulsion of charges to prevent aggregation, passivate core defects to minimize charge trapping, and ultimately protect the QDs from photocorrosion and oxidation46,47. The capped ligands play a decisive role in tuning the optoelectronic properties of QDs, as they can actively participate in photoinduced transformations48. These heterogeneous surface structures can modulate the band-edge potentials of QDs, thereby enabling reactivity beyond the charge transfer mechanisms required in photochemical processes49. However, QDs surface chemistries in light-driven technologies can also be detrimental, since ligands that passivate lattice defects may hinder efficient charge transfer across interfaces, confining carriers within the cores and diminishing dynamic efficiency49,50. Thus, ligand engineering and the rational design of QDs–ligand interfaces are pivotal for understanding and optimizing their optoelectronic properties.

QD surface ligands can be classified according to several criteria (Fig. 3). Organic ligands are typically divided based on chain length; short-chain molecules, such as thiols or carboxylic groups (e.g., 3-mercaptopropionic acid, MPA), generally impart hydrophilic properties to QDs, whereas long alkyl chains, such as oleic acid (OA), confer hydrophobicity50. Organic ligands can also be categorized based on their denticity. The most common are monodentate ligands, such as OA, oleylamine (OLA), or 1-dodecanethiol (DDT), and bidentate ligands, such as MPA. Depending on the functional group, neutral organic ligands may act as electron donors through the lone pairs of heteroatoms, as observed in amines (RNH2) or phosphines (PR3)46,50. Inorganic ligands, on the other hand, are ions or neutral species whose binding behavior relies on their interactions with the QDs surface. Simple anions such as Cl−, −OH, and S2− can donate electrons to metallic centers of the QD core, forming strong coordination bonds50. Neutral inorganic species, such as CdCl2 or Pb(SCN)2, act as electron acceptors that interact with the electronic structure of the QD core or the protective shell lattice50. Both organic and inorganic capping ligands can establish weaker or stronger interactions with QD surfaces, depending on whether they bind through indirect physical interactions or through direct coordination bonds. For instance, bidentate organic ligands containing polar groups such as—SH or –OH often form relatively weak interactions with QDs surfaces51. This occurs because the two binding sites within a single ligand molecule may not simultaneously achieve effective coordination, resulting in unstable attachments or insufficiently robust junctions, particularly under specific conditions.

Organic capping ligands (top) are categorized according to their denticity pattern with the QD surface and the length of their molecular chain. Examples include monodentate ligands such as DDT, bidentate ligands such as MPA, and long-chain ligands such as OA. Inorganic capping ligands (bottom) are categorized based on their electronic interactions with the QD surfaces.

QDs–photoelectrode interface

Ligands are fundamental in defining the surface chemistry of QDs, governing physicochemical processes that directly influence photoinduced transformations46,48,50,52,53. In PEC systems, where QDs are integrated into bulk photoelectrodes, capping ligands function as anchoring groups that dictate QDs attachment to the electrode surface. This QDs–photoelectrode interface mediates charge transfer phenomena through interfacial electronic coupling and modulation of surface states. Anchor molecules provide a tunneling bridge for charge transfer; short-chain ligands create tight interfaces only a few nanometers thick, enabling efficient charge delocalization and injection into the external circuit. Enhanced performance can also be achieved with long-chain ligands containing conjugated bonds, which facilitate charge transport37. Alternatively, polar lattice terminations of some oxide photocatalysts left during synthesis can serve as anchoring sites, such as surface –NH2 groups on TiO2 that link Bi2S3 QDs in the S-scheme charge transfer mechanism54,55. Rational ligand and anchoring group design not only facilitates efficient charge dynamics across interfaces but also tunes surface-site potentials, thereby regulating redox reactions56.

Chalcopyrite I-III-VI2 QDs are advantageous, eco-friendly sensitizers for PEC systems due to their non-toxicity, high stability, and facile synthesis57,58. Cai et al.51 investigated the influence of organic capping ligands on Zn-doped CuInS2 (ZCIS) QDs-sensitizing BiVO4 photoanodes and Cu2O photocathodes in a tandem-like PEC configuration (Fig. 4a). Accordingly, they examined MPA, DDT, and OLA as organic ligands anchoring ZCIS QDs onto BiVO4 and Cu2O bulk photoelectrodes, each exhibiting distinct contacts and interfacial behaviors. Among these, DDT—a short-chain ligand—proved most effective. The direct contact and effective loading of ZCIS QDs onto both BiVO4 and Cu2O surfaces arose from uncoordinated surface metal atoms of the QDs binding directly to oxygen atoms in the oxide photoelectrodes. Meanwhile, the polar –SH groups of DDT coordinated with the QD surface, preventing agglomeration during the thin-film electrophoretic deposition. Interfacial characterization by UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and UV photoelectron spectroscopy revealed an Eg of 2.27 eV and confirmed the formation of a type-II heterojunction between ZCIS QD and BiVO4, as well as a p–n heterojunction between ZCIS QDs and Cu2O (Fig. 4b). These results demonstrate favorable band alignment and the establishment of a built-in and electric field at the interface. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations further supported these findings, showing that electron accumulation occurs on BiVO4 while depletion occurs on ZCIS QDs, favoring electron transfer from QDs to BiVO4. Conversely, in Cu2O, charge depletion takes place at the oxide, while electron accumulation on ZCIs QDs promotes transfer into the QDs surface. According to the direct contact of ZCIS QDs onto coupled photoelectrodes. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements corroborated these interfacial properties, with Nyquist plots (Fig. 4c) showing that ZCIS QDs capped with DDT exhibited the lowest charge transfer resistance compared to those capped with MPA, OLA, or mixed DDT/OLA ligands.

a Tandem-like PEC cell composed of BiVO4 photoanode decorated with Zn-doped CuInS2 (ZCIS) QDs and a Cu2O photocathode decorated with ZCIS QDs. b Schematic illustration of type-II and p–n heterojunctions formed in BiVO₄–ZCIS QDs and Cu₂O–ZCIS QDs photoelectrodes, respectively. c Nyquist plots of ZCIS QDs capped with different organic ligands (ZCISLigand). d, e Photoluminescence spectra of ZCIS QDs capped with d DDT and e MPA, each measured both in solution and as thin-film electrodes. Figures reproduced with permission from ref. 51 Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

In PEC systems, photoluminescence is generally considered a relaxation pathway that competes with charge transport and is therefore undesirable. Efficient PEC performance requires photogenerated carriers to migrate through QD lattices, anchoring groups, and interfaces with merely recombination. While surface ligands mitigate photocorrosion and passivate QD surface traps, the applied bias or self-biased PEC cells suppress radiative recombination, leading to diminished photoluminescence intensity59,60. Consistently, ZCIS QD-based BiVO4 and Cu2O photoelectrodes exhibited markedly reduced photoluminescence signals compared with colloidal ZCIS QDs capped with both DDT and MPA (Fig. 4d, e), indicating that radiative recombination is suppressed and charge transfer becomes the dominant process.

Photosensitizing effect of QDs

Photosensitization refers to the light-induced electronic activation of semiconductors, enabling efficient photon harvesting through tunable Eg. In contrast, non-sensitized photoelectrodes are limited in their light-harvesting capability by the intrinsic Eg of the bulk photocatalyst and may further suffer from suboptimal performance due to carrier trapping in surface defects on poorly pristine semiconductor surfaces61. QDs, along with dyes, metallic nanoclusters, conductive polymers, and inorganic noble-metal complexes, serve as effective photosensitizers62,63. Their primary role is to overcome the inherent limitations of most photoanodes and photocathodes, which typically exhibit poor absorption in the visible light region. By extending the light-harvesting range, these sensitizers enable the advancement of PEC technology toward more efficient solar-driven applications5,8,28,63. A comprehensive review article comparing the performance, advantages, and drawbacks of diverse photon sensitizers are available63.

Due to quantum confinement, QDs are particularly attractive as photosensitizers, as their photoelectronic properties can be precisely tuned through surface chemistry and carrier dynamics. This tunability facilitates efficient charge separation and transfer within photoelectrodes, enabling effective redox reactions62,64,65. Upon light irradiation, QDs absorb photons across a broad spectrum—from visible to near-infrared—resulting in the generation of electron–hole pairs66. Positioned on the outermost surface of the photoelectrode, QDs are ideally exposed to incident light, which maximizes their photoexcitation efficiency67,68. These photogenerated carriers are then injected into adjacent photoelectrode materials and migrate through the layered structure under an applied bias, ultimately reaching an external circuit to the counter electrode. At the solid–solid interface between the photoelectrode and the QD, an internal electric field drives the equilibration of these carriers, enhancing their separation and transport8,67,68,69. When this photosensitized photoelectrode aligns with the electrolyte Fermi level, a new equilibrium is established, further improving carrier diffusion through the lattice and supporting sustained charge transport67,68.

In the case of photoanodes, photoexcited electrons into the QD LUMO can be transferred to the conduction band of the semiconductor substrate (n-type or heterojunction-based) and then transported to the external circuit, while remaining holes in the QD HOMO drive oxidation reactions at the interface with the electrolyte (Fig. 5a)70,71,72. Conversely, in photocathodes, the process is reversed, photogenerated holes can be injected into the valence band of the underlying p-type semiconductor, while the photoexcited electrons in the QD LUMO are retained at the interface, where they reduce target species in the media. Band bending and alignment due to applied polarization play a critical role in both configurations, and tandem-like, as favorable energetic offsets are required to support efficient charge injections and minimize recombination, enhancing photocurrent and photovoltage generation73,74.

a Electronic band diagram illustrating QD sensitization. QDs absorb light that is not efficiently utilized by the bulk photocatalyst, injecting carriers into its electronic bands based on their energy level alignment. This process leaves holes in the photoanode’s valence band or electrons in the photocathode’s conduction band. b PbS-QDs-sensitized TiO2 nanotube photoanode under UV–Vis illumination. PbS harvests a broader range of energy than pure TiO2, facilitating electron transfer through the lattice and extracting them under applied bias. Adapted from ref. 75. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. c Rainbow-like CdSe-QD-sensitized NiO photocathode for PEC hydrogen evolution. Smaller CdSe-QDs (blue) have larger band gaps, while larger CdSe-QDs (red) display smaller band gaps due to the quantum confinement effect. Adapted from ref. 82.

Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain QD-based photosensitization, many of which rely on heterojunction-based processes71. These processes involve carrier injection, trapping defects, edge defects, band bending, and recombination dynamics72,75,76,77. The synergistic interplay between the semiconducting substrate, bulk photocatalyst, and sensitizer QDs is critical to maximizing photon upconversion efficiency. Sensitized photoanodes are typically composed of n-type metal oxides, such as TiO2, decorated with a range of QDs, including carbon dots78, chalcogenides40,75,77,79, or, in some cases, all inorganic perovskites80. Figure 5b shows a typical band diagram of the carrier mechanism for a TiO2 photoanode sensitized with PbS-QDs in a p–n heterojunction75,81. In this configuration, photoexcited electrons in the QDs are transferred to the conduction band of TiO2, while the resulting holes in the valence band of the PbS-QDs diffuse toward energy levels suitable for oxidizing reduced species. This arrangement extends carrier lifetimes and enhances reaction efficiency. Conversely, sensitized photocathodes are designed to facilitate electron injection. In this regard, Lv et al.82 developed a “rainbow-like” photocathode composed of NiO decorated with CdSe-QDs of different sizes. In this configuration, smaller QDs with larger band gaps are positioned closer to the NiO photocathode, while larger QDs are near the outer surface. Such an arrangement enables a stepwise electron transfer process, proceeding in alignment with the conduction band energetics of the successive QD layers (Fig. 5c)82.

Photoelectrochemistry of QDs

Photoelectrochemical properties of QDs are critically determined by their optoelectronic band edges during photoinduced transformations. Investigating these properties is essential for a comprehensive understanding of their role in PEC systems. Traditional electrochemical techniques provide straightforward approaches to probe the band structure of QDs and to evaluate their response under both dark and illuminated conditions83,84,85. Among these, cyclic voltammetry (CV) is a versatile method for analyzing chemical transformations of QDs86,87, as well as their photosensitizing effects in solution84. This approach leverages electrocatalytic interactions between charge donors, acceptors, and redox probes at the illumination-assisted interface. For example, Homer et al.84 analyzed CV profiles to investigate charge transfer from photoexcited CdS-QDs (QD*) to various molecular charge acceptors. The process follows a simple two-step mechanism involving an electrochemically reversible reaction coupled with an irreversible chemical transformation. At the bare electrode surface, different redox probes undergo oxidation (M ⇄ M+ + e−), while the photoexcited QD (QD + hν → QD*) donates an electron to a molecular charge acceptor (QD* + M+ \(\to\) M + QD), thereby regenerating the QD ground state. Notably, the photoexcited QD* behaves as a long-lived electron donor, consisting of conduction band electrons and/or trapped electrons on the surface states of Cd atoms. This excited state acts as a homogeneous photosensitizer, catalyzing electrochemical transformations at rates on the order of 0.1 s−1, leading to characteristic deformations in CV profiles of redox probes. Such distortions correspond to kinetic zones outlined in previous work by Rountree et al.88.

For QD-sensitized photoelectrodes, accurate determination of band structure parameters is essential to ensure proper optical requirements for PEC devices. While spectroscopic and theoretical methods89 are commonly used for investigating band edges, CV is also useful for assessing the electronic band structure of QDs in both high-quality thin-film electrodes and solution-phase media86,90. Several studies have employed CV to analyze how QD features90,91,92,93,94—including their chemical composition80, size-dependent band structure90, and lattice engineering95,96—affect band edges, aiming to optimize QD quality and photoelectrode performance97. A typical CV response—an I-E curve—shows oxidation and reduction currents that correspond to charge transfer phenomena (Fig. 6a). QD composition, including doping, capping, and structural engineering, influences the complexity of waveforms due to the presence of multiple charge transfer processes. In QD-based photoelectrodes, the quantum confinement effect influences these currents, where oxidation corresponds to hole injection (or electron extraction) and reduction to electron injection (or hole extraction)90. The potential at which these peak currents occur is correlated with the valence band maxima (HOMO) and the conduction band minima (LUMO) of the QDs80. The peak-to-peak difference defines the quasiparticle Eg80,90, which often correlates with the optical Eg calculated from spectroscopic data97.

a Schematic CV profile of an irreversible redox system. Oxidation and reduction peaks correspond to the valence band maximum (HOMO) and conduction band minimum (LUMO), respectively. The energy difference between these peaks represents the quasiparticle bandgap of the QDs. Reproduced with permission from ref. 90. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. b CV profiles of all-inorganic perovskite QDs (CsPb1−x’Snx’X3; X = I, Br). Variations in halogen atom stoichiometry result in distinct redox currents in the CV waveforms. c Quasiparticle bandgap energies of all-inorganic perovskite QDs derived from the CV method. b, c Reproduced with permission from ref. 80. Published under an ACS AuthorChoice license. d Schematic representation of inefficient hole injection from a molecular probe superficially bound to CdSe-QDs, highlighting the need for precise interfacial engineering for proper band alignment to ensure efficient carrier injection or extraction. Reproduced with permission from ref. 95. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. e Light-chopped photocurrent response of a CdS-sensitized NiO photocathode, with a maximum photocurrent of 0.13 mA cm−2 at 0 V vs Ag/AgCl. f Light-chopped photocurrent response of a CdSe-sensitized TiO2 photoanode, showing a peak photocurrent of 0.30 mA cm−2 at 0 V vs Ag/AgCl. e, f Reproduced with permission from ref. 99. Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society.

For example, Cardenas-Morcoso et al.80 synthesized a series of non-stoichiometric all-inorganic perovskite QDs (CsPb1−x’Snx’X3; X = I, Br) and analyzed their band structures using CV responses in an organic medium (Fig. 6b). The CV profiles revealed distinct oxidation and reduction currents across the entire potential window, indicating chemical transformations in the perovskite QDs. They determined quasiparticle band gaps ranging from 1.4 eV to 2.4 eV (Fig. 6c). Such insights are crucial for assessing whether a QD can function as an effective photosensitizer for driving specific charge transfer processes. In other words, it helps determine whether charge carriers possess sufficient energy to react effectively with species in the medium, as required for a given PEC system.

Despite its versatility, CV also presents challenges. One limitation is its reliance on precise electrochemical conditions, including the solvent, electrolyte, and substrate. Since QDs must remain stable in solution and are often synthesized with organic agents that protect their core structure, ensuring compatibility with the medium is essential47. Additionally, peak potentials are highly scan rate-dependent, and current maxima may overlap with other charge transfer phenomena90. Therefore, experimental optimization and complementary spectroscopic techniques are necessary to obtain reliable quasiparticle Eg and achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the band energetics of QD-based systems.

In some cases, surface engineering of QDs can be detrimental to specific applications. Figure 6d illustrates a thermodynamically unfavorable hole injection from the PPh3 surface-bound to CdSe-QDs in organic transformations95. This occurs because the redox potential of PPh3 lies below the valence band maximum of CdSe-QDs, preventing efficient charge transfer. However, when organic probes are free in solution, their redox potentials fall within the QD Eg, facilitating both electron and hole injection. This bias-free photocatalytic system relies solely on favorable band alignment95. While interfacial engineering is essential for enhancing carrier dynamics and increasing the density of catalytic sites, inappropriate surface modifications can hinder charge transfer and ultimately diminish catalytic efficiency in most oxide-based photocatalyst98.

A key characteristic of well-sensitized photoelectrodes is their ability to generate photocurrents at lower overpotentials. This performance is achieved through the efficient excitation of a high density of charge carriers in QDs by a broad range of photon energies. These carriers then transfer through the photocatalyst interface, where they either facilitate charge release from low-energy molecular states or are driven into the external circuit under applied bias. For instance, Yang et al.99 fabricated photoanodes and photocathodes sensitized with CdE-QDs for PEC water splitting, observing a maximum photocurrent of approximately 0.13 mA/cm2 for a CdSe/NiO photocathode (Fig. 6e) and 0.30 mA cm−2 for a CdS/TiO2 photoanode (Fig. 6f), both measured at 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl under 1 sun visible-light illumination. These tandem-like PEC systems extend beyond conventional bulk photoelectrodes for visible light harvesting, effectively enhancing solar energy upconversion and resulting in higher energy conversion efficiency. In this study, the system achieved an upconversion efficiency of 0.17% for spontaneous water splitting, highlighting it as a platform for the exploration of new PEC applications.

Catalytic performance of QD-based PEC systems

Most PEC research efforts have focused on exploiting solar-to-energy conversion processes, whose efficiency has been limited in traditional heterogeneous photocatalysis due to its intrinsic drawbacks100. Key review articles focused on operando parameters, ligand engineering, stability, and photoinduced transformations in QD-based PEC systems, while also highlighting current challenges and emerging design trends (refs. 50,57,101,102,103,104).

Among these processes, solar-to-hydrogen (STH) conversion has attracted the greatest attention, given its significance as a clean energy source (ΔH0 = −284 kJ mol−1) with zero carbon emissions during both production and consumption105. Nevertheless, the design of efficient PEC systems remains a considerable challenge, particularly in controlling operando parameters to maximize catalytic performance. Although QD-based photoelectrodes can enhance photon-to-energy conversion efficiency to some extent, a comprehensive understanding of their behavior within PEC systems is still essential106.

Extensive research has therefore investigated diverse system configurations and charge transfer strategies55,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115. In this sense, Ijaz et al.116 synthesized a plasmonic junction-like photocathode comprising Ag gratings coated with CdSe QDs, reporting a sophisticated PEC setup for hydrogen generation. The plasmonic effect enhanced the photocurrent response of CdSe QDs because the plasmonic cavities concentrated photons in the nearby field. These concentrated photons can decay and transfer energy to nearby CdSe QDs, creating new active sites with a high population of charge carriers. Consequently, there is a combined contribution from the photoactivity of QDs, and the thermal activation of hot carriers generated plasmonically. In other words, this represents a synergistic interaction between two nanostructured materials that enables efficient upconversion of light energy.

Core-shell QDs provide a systematic platform to study electron confinement and to gain a comprehensive understanding of their impact on PEC reactions101. Liu J. and coworkers117 studied the size-dependent behavior of InP/ZnSe core-shell QD photoanodes deposited on mesoporous TiO2 films. In this work, the InP core size was fixed at 3.2 nm in diameter, while the ZnSe shell thickness varied from 0.9 to 2.8 nm (Fig. 7a). As the shell thickness increased, the photocurrent rose, reaching a maximum of 6.2 mA cm−2 at a shell thickness of 1.6 nm. Beyond this size, electron-hole dynamics overlap and photocurrent density diminishes (Fig. 7b). The role of the shell lies in passivating surface defects and trap states on InP cores, while simultaneously enhancing carrier dynamics across the core–shell interface. This is achieved through reduced band edge energy and the formation of type-II band alignment, which facilitates charge delocalization and transport to the TiO2 acceptor film, where carriers are available for redox reactions.

a InP/ZnSe core-shell QDs with a constant InP core radius (R) and varying ZnSe shell thickness (H). b Photocurrent density as a function of ZnSe shell thickness for InP cores at 1.0 V vs. RHE. a, b Reproduced with permission from ref. 117. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. c Hydrogen photocatalytic production using wurtzite InP QDs of different sizes and mixed-size systems. d Effective quantum yield of InP QDs under filtered and unfiltered solar irradiation. c, d Reproduced with permission from ref. 118. Published under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Furthermore, the tunable size-dependence of InP QDs allows solar harvesting to be extended across a broader range of the solar spectrum. In this regard, Stone D. and colleagues118, synthesized wurtzite-phase InP QDs of varying sizes for hydrogen photocatalytic production. They demonstrated that combining QDs of different sizes can create a tailored catalytic system capable of harvesting a wider portion of the solar spectrum, including red-shifted photons. When mixtures of InP QDs were used, the hydrogen generation rate increased because charge carriers became more effective (Fig. 7c). Notably, quantum yield was maximized under red-filtered light across all QD sizes, with a peak efficiency of 3% observed for 4.5 nm InP QDs (Fig. 7d). This proof of concept showed that although larger particle sizes reduce absorption efficiency due to decreased band gap energy and edges sharpness, mixed-size systems can successfully broaden spectral utilization, and tailored mixed size system can harvest a broad spectrum.

Engineering InP QDs thus represents an eco-friendly alternative to toxic Cd- and Pb-based QDs, owing to their intrinsic non-toxicity and facile synthesis. Their tunable optical and electronic properties open new avenues for structural design and functional optimization. Moreover, advanced core engineering—such as introducing dopant impurities to form tailored shells—offers further opportunities to boost optoelectronic performance by enhancing light absorption and charge carrier dynamics for redox reactions.

PEC systems represent a promising strategy for water decontamination, enabling the chemical transformation of a wide range of organic pollutants119. Among the reactive species involved, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a powerful oxidant capable of degrading organic contaminants in aqueous media. Thermodynamically, the electrochemical production of H2O2 proceeds via a two-electron pathway with a standard redox potential of 1.760 V vs. SHE, which competes with the four-electron water oxidation of the oxygen evolution reaction120. QD-based PEC systems for H2O2 generation offer a means to address selectivity limitations and improve catalytic performance. In this regard, Zhao et al.121 prepared Se-doped ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) photoanodes decorated with triple-structured InP/GaP/ZnSe QDs (ZIS-Se/QDs) for H2O2 generation. The ZIS-Se/QDs photoanode exhibited higher IPCE across 400–650 nm compared to bare ZIS and ZIS-Se (Fig. 8a), consistent with its superior integrated photocurrent density of 4.0 mA cm−2. The corresponding faradaic efficiency (FE) for H2O2 generation, calculated within 0.65–1.85 V vs. (Reference Hydrogen Electrode, RHE), reached an outstanding 86%, which is 1.3 times higher than that of ZIS-Se photoanode (Fig. 8b). This enhancement arises from the synergistic effect of Se dopants and the mixed-QD heterostructure, which effectively regulates the competition between the two- and four-electron reactions by tuning band-edge bending and the redox potential of active holes for H2O2 production. DFT calculations further confirmed that the two-electron pathway is favored on ZIS-Se/QDs surface, exhibiting the lowest Gibbs free energy for *OH intermediates, while the oxidation of *OH into *O and *OOH toward oxygen evolution proceeds via a thermodynamically less favorable route, as depicted in the free energy diagram in Fig. 8c.

a IPCE spectra for Se-doped ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) photoanode decorated with triple-structured InP/GaP/ZnSe QDs (ZIS-Se/QDs), compared with ZIS-Se and bare ZIS, along with their integrated photocurrent density at 1.23 V vs. RHE. b FE for H2O2 production. c Free energy diagram for water oxidation pathways. Figures reproduced with permission from ref. 121. Copyright 2024, Elsevier.

In brief, Table 1 summarizes key original studies on water pollutant degradation using QD-based PEC systems. Despite substantial progress in water decontamination technologies, further efforts are needed to optimize light-driven processes, deepen the understanding of quantum material properties, and harness these properties for solar-driven energy and chemical transformations.

Conclusions and future prospects

QDs are emerging materials with significant potential owing to their unique optoelectronic properties. In this review, their pivotal role in PEC technology has been examined, with emphasis on key attributes that enhance charge transfer processes during catalysis and on strategies for engineering innovative QD surfaces and QD–photoelectrode interfaces. Reactions driven by QD sensitization—particularly under applied external bias—have demonstrated improved efficiency in photon-mediated processes, including energy upconversion, chemical synthesis, and sustainable energy production. While QDs have significantly advanced the performance of both photoanodes and photocathodes, thereby contributing to system-wide synergy, achieving high PEC efficiency has remained contingent upon precise control of operando parameters.

The development of stable, high-performance, and reproducible QD-based photoelectrodes requires stringent control over synthesis. Achieving optimal interfacial compatibility among the electrode, photocatalyst, sensitizer, capping ligands, and electrolyte remains a major challenge. When QDs are integrated into bulk photoelectrodes, the complexity further increases, necessitating effective anchoring to bulk photocatalysts, conductive substrates, and the overall architecture. Rational design and precise control of colloidal QD surfaces, as well as their anchoring to photoelectrodes, are therefore essential to achieve efficient charge transfer dynamics. Considerable research efforts have focused on ligand engineering, particularly ligand exchange during synthesis, which can mitigate electronic trap states and otherwise reduce carrier lifetimes and hinder redox transformations. However, only limited attention has been devoted to the mechanistic role of anchoring molecules that bridge QDs and electrodes, facilitating charge delocalization and enabling effective energy-level alignment for external bias conduction or redox processes. A comprehensive understanding of how linkers and anchoring strategies modulate QD–photoelectrode interfaces under applied potential is still required.

Recent advances in materials engineering have led to a new generation of nanostructured materials with tunable properties. Research is increasingly focused on refining their structural, compositional, optical, and electronic characteristics to enhance efficiency and stability. The integration of artificial intelligence-assisted synthesis tools is opening up new frontiers, enabling the design of nanocatalysts with physicochemical properties that surpass current limitations122. These tools allow for precise control over architecture, synthesis methodologies, reagent consumption, reaction times, and ultimately, the properties of the final material. Such innovations not only extend traditional PEC applications in energy and the environment but also open the door to cutting-edge fields such as neurobiological PEC devices.

As the field of light-driven technologies advances, significant efforts have been devoted toward STH conversion, recognized as a promising strategy for producing green fuels and enabling large-scale energy storage. Hydrogen, in particular, represents a sustainable alternative to environmentally detrimental carbon-based fuels. However, despite rapid progress, current catalytic systems and operando devices remain far from meeting the minimum STH efficiency threshold of 10% required for commercial purposes. At the laboratory scale, achieving this benchmark demands innovative approaches that address challenges across multiple levels of system design. These include the development of QD-based catalytic architectures, integration of tandem cells, and optimized device configurations. Furthermore, reliable and reproducible pathways for pollutant upconversion must be established to broaden the functional scope of these systems. Collectively, such strategies are essential to pave the way for scalable, sustainable, and high-impact PEC technologies.

Data availability

No primary research results, software, or code have been included, and no new data were generated or analyzed as part of this review.

References

Efros, A. L. & Brus, L. E. Nanocrystal quantum dots: from discovery to modern development. ACS Nano 15, 6192–6210 (2021).

Parak, W. J., Manna, L. & Nann, T. Fundamental principles of quantum dots. In Nanotechnology: Principles and Fundamentals Vol. 1, 73–96 (WILEY-VCH, Verlag, 2008).

Efros, A. L. & Nesbitt, D. J. Origin and control of blinking in quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 661–671 (2016).

Manna, L. The bright and enlightening science of quantum dots. Nano Lett. 23, 9673–9676 (2023).

García de Arquer, F. P. et al. Semiconductor quantum dots: technological progress and future challenges. Science 373, 1–14 (2021). This review provides a comprehensive analysis of quantum dot technology, accompanied by an accurate explanation of the fundamentals of quantum dot properties.

Park, Y. S., Roh, J., Diroll, B. T., Schaller, R. D. & Klimov, V. I. Colloidal quantum dot lasers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 382–401 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Full-color fluorescent carbon quantum dots. Sci. Adv. 6, 1–9 (2020).

Zhao, H. & Rosei, F. Colloidal quantum dots for solar technologies. Chem 3, 229–258 (2017).

Wang, X., Sun, G., Li, N. & Chen, P. Quantum dots derived from two-dimensional materials and their applications for catalysis and energy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2239–2262 (2016).

Kovalenko, M. V. et al. Prospects of nanoscience with nanocrystals. ACS Nano 9, 1012–1057 (2015).

Ekimov, A. I. & Onushchenko, A. A. Quantum size effect in three-dimensional microscopic semiconductor crystals. JETP Lett. 118, S15–S17 (1981). This work serves as a primer on the discovery of quantum dots and the study of their optoelectronic properties.

Brus, L. Electronic wave functions in semiconductor clusters: experiment and theory. J. Phys. Chem. 90, 2555–2560 (1986). This work paves the way for quantum dot research by explaining the quantum theory underlying the optical and electronic properties of these nanocrystals.

Sumanth Kumar, D., Jai Kumar, B. & Mahesh, H. M. Quantum nanostructures (QDs): an overview. In Synthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials: Advances and Key Technologies 59–88 (Elsevier Ltd., 2018); https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-101975-7.00003-8.

Neikov, O. D. & Yefimov, N. A. Nanopowders. Handbook of Non-Ferrous Metal Powders (Elsevier Ltd., 2019); https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-100543-9.00009-9.

Zeng, Z., Chen, S., Tan, T. T. Y. & Xiao, F. X. Graphene quantum dots (GQDs) and its derivatives for multifarious photocatalysis and photoelectrocatalysis. Catal. Today 315, 171–183 (2018).

Ahirwar, S., Mallick, S. & Bahadur, D. Electrochemical method to prepare graphene quantum dots and graphene oxide quantum dots. ACS Omega 2, 8343–8353 (2017).

Hsu, J. C. et al. Nanomaterial-based contrast agents. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 3, 30 (2023).

Pu, Y., Cai, F., Wang, D., Wang, J. X. & Chen, J. F. Colloidal synthesis of semiconductor quantum dots toward large-scale production: a review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 1790–1802 (2018).

Owen, J. & Brus, L. Chemical synthesis and luminescence applications of colloidal semiconductor quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10939–10943 (2017).

Murray, C. B., Norris, D. J. & Bawendi, M. G. Synthesis and characterization of nearly monodisperse CdE (E = S, Se, Te) semiconductor nanocrystallites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 8706–8715 (1993). This work introduces, for the first time, a chemical method to produce quantum dots with controlled size, tailored optoelectronic properties, and nearly pristine surfaces.

Loiudice, A. & Buonsanti, R. Reaction intermediates in the synthesis of colloidal nanocrystals. Nat. Synth. 1, 344–351 (2022).

Levy, M., Chowdhury, P. P. & Nagpal, P. Quantum dot therapeutics: a new class of radical therapies. J. Biol. Eng. 13, 1–12 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Ultrasmall BiOI quantum dots with efficient renal clearance for enhanced radiotherapy of cancer. Adv. Sci. 7, 1902561 (2020).

Gu, L. et al. Colloidal quantum dots-based photoelectrochemical-type optoelectronic synapse. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2415178 (2025).

Prather, K. V., Stoffel, J. T. & Tsui, E. Y. Redox reactions at colloidal semiconductor nanocrystal surfaces. Chem. Mater. 35, 3386–3403 (2023).

Abu Shmeis, R. M. Nanotechnology in wastewater treatment. Compr. Anal. Chem. 99, 105–134 (2022).

Sun, P., Xing, Z., Li, Z. & Zhou, W. Recent advances in quantum dots photocatalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 458, 141399 (2023).

Yuan, J. et al. Metal halide perovskites in quantum dot solar cells: progress and prospects. Joule 4, 1160–1185 (2020).

Han, J. et al. Perovskite solar cells. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 5, 0123456789 (2025).

Liang, J. et al. Recent progress and development in inorganic halide perovskite quantum dots for photoelectrochemical applications. Small 16, 1–20 (2020).

Nellist, M. R., Laskowski, F. A. L., Lin, F., Mills, T. J. & Boettcher, S. W. Semiconductor-electrocatalyst interfaces: theory, experiment, and applications in photoelectrochemical water splitting. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 733–740 (2016).

Wu, Z. et al. A semiconductor-electrocatalyst nano interface constructed for successive photoelectrochemical water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–9 (2023).

Ullal, N., Mehta, R. & Sunil, D. Separation and purification of fluorescent carbon dots – an unmet challenge. Analyst 149, 1680–1700 (2024).

Kashyap, A., Singh, N. K., Soni, M. & Soni, A. Deposition of Thin Films by Chemical Solution-Assisted Techniques. Chemical Solution Synthesis for Materials Design and Thin Film Device Applications (Elsevier Inc., 2021); https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819718-9.00014-5.

Altomare, M., Nguyen, N. T., Naldoni, A. & Marschall, R. Structure, materials, and preparation of photoelectrodes. Photoelectrocatalysis Fundam. Appl. 92, 83–174 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823989-6.00005-9 (2023).

Wu, H., Zhang, D., Lei, B. X. & Liu, Z. Q. Metal oxide based photoelectrodes in photoelectrocatalysis: advances and challenges. Chempluschem 87, e202200097 (2022).

Tao, C. L. et al. Scalable synthesis of high-quality core/shell quantum dots with suppressed blinking. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 1–10 (2023).

Kumar, M., Meena, B., Subramanyam, P., Suryakala, D. & Subrahmanyam, C. Recent trends in photoelectrochemical water splitting: the role of cocatalysts. NPG Asia Mater. 14, 88 (2022).

Wang, G., Yang, X., Qian, F., Zhang, J. Z. & Li, Y. Double-sided CdS and CdSe quantum dot co-sensitized ZnO nanowire arrays for photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation. Nano Lett. 10, 1088–1092 (2010).

Xu, J., Olvera-Vargas, H., Ou, G. H. X., Randriamahazaka, H. & Lefebvre, O. Hybrid TiO2/Carbon quantum dots heterojunction photoanodes for solar photoelectrocatalytic wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 341, 140077 (2023).

Essner, J. B., Kist, J. A., Polo-Parada, L. & Baker, G. A. Artifacts and errors associated with the ubiquitous presence of fluorescent impurities in carbon nanodots. Chem. Mater. 30, 1878–1887 (2018).

Kaur, I. et al. Chemical- and green-precursor-derived carbon dots for photocatalytic degradation of dyes. iScience 27, 108920 (2024).

Ye, M., Gong, J., Lai, Y., Lin, C. & Lin, Z. High-efficiency photoelectrocatalytic hydrogen generation enabled by palladium quantum dots-sensitized TiO 2 nanotube arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15720–15723 (2012).

Tsui, E. Y. Surface considerations in colloidal semiconductor nanocrystal photocatalysis: a mini review. Energy Fuels 39, 7182–7195 (2025). This work highlights the key aspects of quantum dot surface behavior in light-driven technologies.

Herrera, F. C. et al. Chemical design of efficient photoelectrodes by heterogeneous nucleation of carbon dots in mesoporous ordered titania films. Chem. Mater. 35, 8009–8019 (2023).

De Roo, J. The surface chemistry of colloidal nanocrystals capped by organic ligands. Chem. Mater. 35, 3781–3792 (2023).

Dou, F. Y. et al. Pathways of CdS quantum dot degradation during photocatalysis: implications for enhancing stability and efficiency for organic synthesis. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 15781–15785 (2024).

Ye, C., Zhang, D. S., Chen, B., Tung, C. H. & Wu, L. Z. Interfacial charge transfer regulates photoredox catalysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 10, 529–542 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Charge transfer from quantum-confined 0D, 1D, and 2D nanocrystals. Chem. Rev. 124, 5695–5763 (2024).

Chen, Y., Yu, S., Fan, X. B., Wu, L. Z. & Zhou, Y. Mechanistic insights into the influence of surface ligands on quantum dots for photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 8497–8514 (2023).

Cai, M. et al. Ligand-Engineered Quantum Dots Decorated Heterojunction Photoelectrodes For Self-biased Solar Water Splitting. Small 18, 1–11 (2022).

Peter, C. Y. M. et al. Modulating hole transfer from CdSe quantum dots by manipulating the surface ligand density. Nano Lett. 25, 8993–8998 (2025).

Harvey, S. M. et al. Ligand desorption and fragmentation in oleate-capped CdSe nanocrystals under high-intensity photoexcitation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3732–3741 (2024).

Xing, B., Wang, T., Han, X., Zhang, K. & Li, B. Anchoring Bi2S3 quantum dots on flower-like TiO2 nanostructures to boost photoredox coupling of H2 evolution and oxidative organic transformation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 650, 1862–1870 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Novel Bi2Sn2O7 quantum dots/TiO2 nanotube arrays S-scheme heterojunction for enhanced photoelectrocatalytic degradation of sulfamethazine. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 321, 122053 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Wang, W., Rao, H., Pan, Z. & Zhong, X. Improving the efficiency of quantum dot-sensitized solar cells by increasing the QD loading amount. Chem. Sci. 15, 5482–5495 (2024).

Du, Z. & Ma, D. Recent progress in I-III-VI colloidal quantum dots-integrated solar cells. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 75, 101890 (2025).

Ikram, A., Zulfequar, M. & Satsangi, V. R. Role and prospects of green quantum dots in photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation: a review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 11472–11491 (2022).

Liu, Q., Fu, Z., Wang, Z., Chen, J. & Cai, X. Rapid and selective oxidation of refractory sulfur-containing micropollutants in water using Fe-TAML/H2O2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 315, 121535 (2022).

Su, P., Li, S. & Xiao, F. X. PrecisE Layer-by-layer Assembly Of Dual Quantum Dots Artificial Photosystems Enabling Solar Water Oxidation. Small 20, 1–12 (2024).

Pastor, E. et al. Electronic defects in metal oxide photocatalysts. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 503–521 (2022).

Abbas, M. A., Jeon, M. & Bang, J. H. Understanding the photoelectrochemical behavior of metal nanoclusters: a perspective. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 16928–16942 (2022).

Khalkhali, F. S. et al. A review on the photosensitizers used for enhancing the photoelectrochemical performance of hydrogen production with emphasis on a novel toxicity assessment framework. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 51, 990–1022 (2024). This review comprehensively compares various light sensitizers in photoelectrocatalytic systems, discussing their main advantages and disadvantages, as well as providing a toxicity assessment.

Khan, Z. U. et al. Colloidal quantum dots as an emerging vast platform and versatile sensitizer for singlet molecular oxygen generation. ACS Omega 8, 34328–34353 (2023).

Li, X. B., Tung, C. H. & Wu, L. Z. Semiconducting quantum dots for artificial photosynthesis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 160–173 (2018).

Kim, T. Y. et al. Interfacial engineering at quantum dot-sensitized TiO2photoelectrodes for ultrahigh photocurrent generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 6208–6218 (2021).

Nozik, A. J. Quantum dot solar cells. Phys. E Low.-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 14, 115–120 (2002).

Miller, R. J. D. & Memming, R. Fundamentals in photoelectrochemistry. In Nanostructured and Photoelectrochemical Systems for Solar Photon Conversion (ed. Nozik, A. J.) Vol. 3, 39–145 (2008).

Kamat, P. V. Quantum dot solar cells. The next big thing in photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 908–918 (2013).

Sivula, K. & Van De Krol, R. Semiconducting materials for photoelectrochemical energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 15010 (2016).

Jun, H. K., Careem, M. A. & Arof, A. K. Quantum dot-sensitized solar cells-perspective and recent developments: A review of Cd chalcogenide quantum dots as sensitizers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 22, 148–167 (2013).

Yang, Y., Li, Y., Gong, W., Guo, H. & Niu, X. Cobalt-doped CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots for photoelectrocatalytic hydrogen production via efficient charge transport. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 663, 131083 (2023).

Su, Y. et al. Single-nanowire photoelectrochemistry. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 609–612 (2016).

Grätzel, M. Photoelectrochemical cells. Nature 414, 338–344 (2001).

Mazierski, P. et al. Ti/TiO2 nanotubes sensitized PbS quantum dots as photoelectrodes applied for decomposition of anticancer drugs under simulated solar energy. J. Hazard. Mater. 421, 126751 (2022).

Bi, Q. et al. Preparation of a direct Z-scheme thin-film electrode based on CdS QD-sensitized BiOI/WO3 and its photoelectrocatalytic performance. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 599, 124849 (2020).

Kumar, S. et al. Fabrication of TiO2/CdS/Ag2S nano-heterostructured photoanode for enhancing photoelectrochemical and photocatalytic activity under visible light. ChemistrySelect 1, 4891–4900 (2016).

Shi, R. et al. Effect of nitrogen doping level on the performance of N-doped carbon quantum Dot/TiO2 composites for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. ChemSusChem 10, 4650–4656 (2017).

Li, S., Liu, C., Chen, P., Lv, W. & Liu, G. In-situ stabilizing surface oxygen vacancies of TiO2 nanowire array photoelectrode by N-doped carbon dots for enhanced photoelectrocatalytic activities under visible light. J. Catal. 382, 212–227 (2020).

Cardenas-Morcoso, D. et al. Photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical degradation of organic compounds with all-inorganic metal halide perovskite quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 630–636 (2019).

Kim, T. Y. et al. Interfacial engineering at quantum dot-sensitized TiO2 photoelectrodes for ultrahigh photocurrent generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 6208–6218 (2021).

Lv, H. et al. Semiconductor quantum dot-sensitized rainbow photocathode for effective photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11297–11302 (2017).

Kelm, J. E., Bredar, A. R. C., Rountree, K. J. & Dempsey, J. L. The relationship between surface defectivity of CdSe quantum dots and interfacial charge transfer studied by cyclic voltammetry. J. Phys. Chem. C. 129, 10601–10612 (2025).

Homer, M. K., Kuo, D. Y., Dou, F. Y. & Cossairt, B. M. Photoinduced charge transfer from quantum dots measured by cyclic voltammetry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14226–14234 (2022).

Homer, M. K. et al. Extremely long-lived charge donor states formed by visible irradiation of quantum dots. ACS Nano 18, 24591–24602 (2024).

Osipovich, N. P., Poznyak, S. K., Lesnyak, V. & Gaponik, N. Cyclic voltammetry as a sensitive method for in situ probing of chemical transformations in quantum dots. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 10355–10361 (2016).

Lim, C. S., Hola, K., Ambrosi, A., Zboril, R. & Pumera, M. Graphene and carbon quantum dots electrochemistry. Electrochem. commun. 52, 75–79 (2015).

Rountree, E. S., McCarthy, B. D., Eisenhart, T. T. & Dempsey, J. L. Evaluation of homogeneous electrocatalysts by cyclic voltammetry. Inorg. Chem. 53, 9983–10002 (2014).

Buerkle, M., Lozac’h, M., Mariotti, D. & Švrček, V. Quasi-band structure of quantum-confined nanocrystals. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–7 (2023).

Xian, L., Zhang, X. & Li, X. Voltammetric determination of electronic structure of quantum dots. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 34, 101022 (2022).

Inamdar, S. N., Ingole, P. P. & Haram, S. K. Determination of band structure parameters and the quasi-particle gap of CdSe quantum dots by cyclic voltammetry. ChemPhysChem 9, 2574–2579 (2008).

Haram, S. K. et al. Quantum confinement in CdTe quantum dots: Investigation through cyclic voltammetry supported by density functional theory (DFT). J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 6243–6249 (2011).

Sabah, A. et al. Investigation of band parameters and electrochemical analysis of multi core-shell CdSe/CdS/ZnS quantum dots. Opt. Mater. 142, 114065 (2023).

Xian, L. et al. Electrochemically determining electronic structure of ZnO quantum dots with different surface ligands. Chemistry 28, e202201682 (2022).

Chakraborty, I. N., Roy, P. & Pillai, P. P. Visible light-mediated quantum dot photocatalysis enables olefination reactions at room temperature. ACS Catal. 13, 7331–7338 (2023).

Efrati, A. et al. Electrochemical switching of photoelectrochemical processes at CdS QDs and photosystem I-modified electrodes. ACS Nano 6, 9258–9266 (2012).

Ingole, P. P. A consolidated account of electrochemical determination of band structure parameters in II–VI semiconductor quantum dots: A tutorial review. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 4695–4716 (2019).

Liu, Y. & Zhang, W. Symbiotic oxides in catalysts. Nat. Catal. 6, 985–986 (2023).

Yang, H. B. et al. Stable quantum dot photoelectrolysis cell for unassisted visible light solar water splitting. ACS Nano 8, 10403–10413 (2014).

Gao, Y. J. et al. Site- and spatial-selective integration of non-noble metal ions into quantum dots for robust hydrogen photogeneration. Matter 3, 571–585 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Stability of photoelectrochemical cells based on colloidal quantum dots. Chem. Soc. Rev. 54, 3513–3534 (2025).

Cao, Q., Feng, J., Chang, K. T., Liang, W. & Lu, H. Emerging opportunities of colloidal quantum dots for photocatalytic organic transformations. Adv. Mater. 37, 2409096 (2025).

Salunkhe, T. T. et al. Exploring photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical applications of g-C3N4/metal sulfide quantum dots nanocomposites: a review of recent trends and innovations. J. Chem. 2025, 8849437 (2025).

Su, H. et al. Recent advances in quantum dot catalysts for hydrogen evolution: Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic application. Carbon Energy 5, 1–37 (2023).

Nishioka, S., Osterloh, F. E., Wang, X., Mallouk, T. E. & Maeda, K. Photocatalytic water splitting. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 3, 1–15 (2023).

Ansari, S. A. Quantum dots assisted light-driven water splitting towards hydrogen production: a review. Fuel 404, 136252 (2026).

Yuan, Z. et al. All-solid-state WO3/TQDs/In2S3 Z-scheme heterojunctions bridged by Ti3C2 quantum dots for efficient removal of hexavalent chromium and bisphenol A. J. Hazard. Mater. 409, 125027 (2021).

Wu, H. et al. B-doping mediated formation of oxygen vacancies in Bi2Sn2O7 quantum dots with a unique electronic structure for efficient and stable photoelectrocatalytic sulfamethazine degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 456, 131696 (2023).

Ibrahim, I. et al. Cadmium sulfide nanoparticles decorated with Au quantum dots as ultrasensitive photoelectrochemical sensor for selective detection of copper(II) ions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 22202–22214 (2016).

Su, Y. et al. Carbon quantum dots-decorated TiO2/g-C3N4 film electrode as a photoanode with improved photoelectrocatalytic performance for 1,4-dioxane degradation. Chemosphere 251, 126381 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Lin, S., Li, X., Li, H. & Cui, W. Metal free and efficient photoelectrocatalytic removal of organic contaminants over g-C3N4 nanosheet films decorated with carbon quantum dots. RSC Adv. 7, 56335–56343 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. CQDs improved the photoelectrocatalytic performance of plasma assembled WO3/TiO2-NRs for bisphenol A degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 443, 130250 (2023).

Wu, C. et al. Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3 quantum dots-sensitized rutile TiO2 nanorod arrays for enhanced solar photoelectrocatalysis in azo dye degradation. J. Phys. Energy 3, 014003 (2020).

Jin, L., Zhao, H., Wang, Z. M. & Rosei, F. Quantum dots-based photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution from water splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 1–28 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. MXene quantum dots-Co(OH)2 heterojunction stimulated Co2+δ sites for boosted alkaline hydrogen evolution. Acta Mater. 283, 120507 (2025).

Ijaz, M. et al. Plasmonically coupled semiconductor quantum dots for efficient hydrogen photoelectrocatalysis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 053901 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Efficient photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation using eco-friendly ‘giant’ InP/ZnSe core/shell quantum dots. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 34797–34808 (2023).

Stone, D., Gigi, S., Naor, T., Li, X. & Banin, U. Size-dependent photocatalysis by wurtzite InP quantum dots utilizing the red spectral region. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 5907–5913 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Basic comprehension and recent trends in photoelectrocatalytic systems. Green Chem. 26, 1682–1708 (2024). This work presents a comprehensive overview of photoelectrocatalysis and its main environmental applications.

Perry, S. C. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and oxygen. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 442–458 (2019).

Zhao, H. et al. Synergistic selenium doping and colloidal quantum dots decoration over ZnIn2S4 enabling high-efficiency photoelectrochemical hydrogen peroxide production. Chem. Eng. J. 491, 151925 (2024).

Tao, H. et al. Nanoparticle synthesis assisted by machine learning. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 701–716 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Synthesis-on-substrate of quantum dot solids. Nature 612, 679–684 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.X.C.-C.: conceptualized the study, conducted the literature review, wrote the initial draft, performed data visualization, and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. S.V.-Z.: contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. P.J.E.-M.: conceptualized the study, performed data visualization, contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript, conceived, designed, and supervised the project, acquired.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castillo-Cabrera, G.X., Vélez-Zambrano, S. & Espinoza-Montero, P.J. Role of quantum dots in photoelectrocatalytic technology. Commun Chem 8, 394 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01775-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01775-w