Abstract

The use of weak, inexpensive bases in the assembly of late-transition metal NHC complexes represents a most promising synthetic strategy. We now disclose the use of gaseous and aqueous ammonia as bases for the continuous-flow synthesis of these complexes with Au, Pd, and Cu metal centers. The fully homogeneous system enables reactions to proceed under milder, faster, and more concentrated conditions than state-of-the-art methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past three decades, the introduction of N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands has led to significant advances in organometallic chemistry, rapidly becoming a “privileged ligand family” in catalytic chemistry1,2. Originally regarded as phosphine mimics, NHC ligands have since distinguished themselves through their unique combination of substantial steric influence, structural flexibility, and exceptional σ-electron-donating properties, allowing very strong NHC-metal bonds in the resulting NHC-metal complexes3. The broad utilization of these exceptional ligands has driven innovation in sustainable, efficient, and operationally simple synthetic routes enabling access to metal-NHC complexes4. In transition metal mediated catalysis, catalyst accessibility remains a pivotal parameter governing the practicality and efficiency of any given catalytic system.

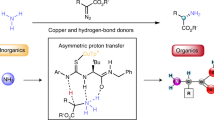

Transition metal NHC complexes have historically been synthesized via one of three routes (Scheme 1)5. The first and most prevalent method, originating from Arduengo’s seminal discovery of the first stable NHC6, employs free carbenes, either pre-isolated or generated in-situ (Scheme 1a, “Free carbene route”)7,8. Even though this method allowed the subsequent studies of NHC coordination on various metal centers, the two-step approach involves the addition of a strong base (e.g., KOtBu, NaH) to an azolium salt to generate a free-carbene and the subsequent introduction of a metal source under an inert atmosphere, using strictly anhydrous conditions. The second approach is called the “transmetalation route” (Scheme 1b)9,10. In this two-step approach, an azolium salt is first reacted with silver or copper oxide to form the corresponding Ag- or Cu-NHC complexes. These intermediates then transfer the NHC ligands to the targeted metal, yielding the desired NHC-metal complex. Despite advantages such as the use of air-stable starting materials, this method suffers from several drawbacks, including high reaction temperatures, the requirement of toxic solvents, and significant waste generation.

The last and most recent method—the “weak base route”—was developed by the groups of Nolan and Gimeno independently in 2013 (Scheme 1c)11,12. These pioneering studies and subsequent investigation showed that this weak-base route can offer significant advantages, including tolerance to air, greener solvents (acetone, ethyl acetate), and the use of less toxic, cost-efficient weak bases (e.g., K2CO3, NaOAc13, aqueous ammonia (NH3 (aq.))14,15,16,17,18) to prepare a wide range of NHC-metal complexes in high yields and purity. Among weak bases, aqueous ammonia stands out in terms of its economical advantage (only ~0.26 cents per mmol, based on current Sigma-Aldrich pricing). This has motivated its use in the synthesis of metal-NHC complexes in batch processes, as pioneered by the Cisnetti team15,16 and further developed by our group14,17,18 (Table 1). Notably, despite its weaker basicity than K2CO314, the ammonia route has, in some cases, outperformed the standard K₂CO₃ method; for instance, in the synthesis of [Pd(IPr)(η³-cin)Cl], it offered superior yield, reaction time, temperature, and E-factor17. Thus, these promising batch results present a clear opportunity to explore the use of aqueous ammonia in alternative synthetic formats, such as continuous flow, for the preparation of metal-NHC complexes.

Investigating more efficient access to NHC-metal complexes has been one of the interests of our research team. In this regard, the feasibility of translating existing batch procedures to alternative setups has been investigated (Scheme 1c). Among many processes, the continuous-flow system is a markedly appealing option. This technology has significantly impacted numerous scientific disciplines.

It is particularly evident in synthetic chemistry, where the exponential growth in flow chemistry publications has yielded an extensive library of demonstrated applications19. Flow technology offers several key advantages, including improved mass and heat transfer that enables rapid mixing, precise control over critical reaction parameters (time, temperature, and pressure), along with the safe handling of hazardous reagents due to the reactors’ smaller volumes20,21. Moreover, unlike batch processes, it is possible to perform continuous in-line analysis/purification due to the modulability of the system22,23. To the best of our knowledge, there are only a few examples of continuous flow synthesis of metal-NHC complexes (Scheme 2). The first example of the continuous flow synthesis of metal-NHC complexes was investigated by McQuade and co-workers in 201324. In this study, Cu-NHC complexes ([Cu(NHC)Cl] type) were prepared via the “transmetalation route” by passing an imidazolium salt solution through a solid Cu₂O-packed bed reactor (Scheme 2a). However, this solid-phase flow approach suffers from several limitations: (1) requirement of environmentally hazardous solvent mixtures (5% MeOH/80% CH₂Cl₂/15% toluene); (2) elevated reaction temperatures (110 °C) necessary to achieve high conversion; and (3) rapid reactor deactivation, with significant efficiency loss occurring within 10 min of operation. The subsequent work from our research team significantly improved the reaction efficiency by successfully translating the batch process weak-base route into a flow regime (Scheme 2b)25. However, despite its efficient output (for example, 2 min residence time, 92% yield for [Cu(IPr)Cl]), this method also suffered from issues related to the packed bed setup (insoluble K2CO3), namely (1) the solid reagent is consumed over time and replacement is needed between each experimental run, hence it is not suitable for a fully continuous operation (2) the solid-phase reactor is prone to poisoning and clogging which significantly compromise reactor performance. (3) A diluted system is needed to avoid clogging. To address these issues, Harvie and co-workers proposed a biphasic flow system consisting of an aqueous K2CO3 stream and dichloromethane (DCM) solution containing NHC salts and gold metal source (Scheme 2c)26. The authors could successfully avoid the issues related to the solid-phase reactors by dissolving the inorganic base in water, and also showed the applicability of the method to NHC-Au(III) complexes. However, extended residence time was required, probably due to a less efficient mixing of the biphasic system (DCM and water), and the applicability to other metals than gold-NHC complexes remains unclear. To overcome these limitations, particularly those associated with solid-phase flow reactors, we propose the use of fluidic weak bases (gaseous or liquid) for the continuous flow synthesis of metal-NHC complexes. Building on our recent findings, which demonstrated the efficacy of aqueous ammonia as an economical and effective weak base in the synthesis of gold and palladium NHC complexes via the weak base route14,17,18, we were motivated to investigate the potential of gaseous and aqueous ammonia as fluidic weak bases in such systems. This study reports the continuous flow synthesis of palladium, gold, and copper heteroleptic chloro N,N-diaryl NHC complexes. Our initial focus is on complexes bearing the 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene (IPr) ligand, as it is the most prevalent NHC in homogeneous catalysis25. Moreover, the methodology is also successfully extended to other N,N-diaryl substituted NHC structures for the palladium complexes.

Previous and current studies in the synthesis of metal-NHC complexes in flow. This scheme summarizes the evolution of continuous-flow synthesis for metal-NHC complexes in chronological order: the Macquade method (a), the solid/weak base route (b), the liquid/weak base route (c) and the aqueous ammonia route reported here (d).

Result and discussion

Firstly, we examined the use of gaseous ammonia as a fluidic weak base with a so-called “tube-in-tube” reactor. In this system, a novel flow chemistry strategy demonstrated by the Ley group for conducting gas-liquid reactions was employed27. This two-layered tubular system consists of an inner tube made of a highly gas-permiable amorphous fluoropolymer membrane (Teflon AF-2400 membrane) covered by a normal PTFE tubing. In this way, gaseous reagents dissolve into the liquid reaction mixture by permeating through the membrane. This system not only allows for the safe handling of (toxic) gases due to the absence of the headspace in reactors and its closed system, but also avoids the inherent limitations of conventional batch reactors, such as less efficient mass and heat transfer rates28. The reactor system was constructed following the previous study conducted by Ley and co-workers29. It employed a tube-in-tube reactor (1 mL), with ammonia gas (3.5 bar) saturating the space between inner and outer tubings, while a liquid reaction mixture flowed through the inner tubing. Under these conditions, the ammonia gas permeated through the membrane and was continuously supplied to the reaction mixture (see Methods and Supplementary Information for the details). Swagelok T-pieces were used to connect the gas and liquid feeds. Following ammonia transfer into the liquid phase in the tube-in-tube reactor, the stream proceeded through an additional reaction coil (5 mL) in a water bath at the desired temperature (Temp. B) and subsequently went through a back-pressure regulator, which ensured the gas remained dissolved under pressure. To promote ammonia permeation into the reaction mixture stream, the tube-in-tube reactor was maintained at 0 °C (Temp. A) in an ice bath (Scheme 3, see Supplementary Information for the photos of the reactor, Fig. S1).

Schematic of the tube-in-tube gas-liquid flow reactor (top), and the results of NHC-metal complex synthesis (bottom). Flow rate was set to 1.0 mL/min, making residence time RT1 = 1 min (1 mL) and RT2 = 5 min (5 mL). Temp. A was kept at 0 °C in an ice bath. Temp. B was kept at 40 °C in a water bath. [M] is a metal source.

With a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and a reaction coil temperature at 40 °C, the reaction mixture stream containing IPr·HCl and metal sources in acetone was pushed through the reactors. With the metal source of [Pd(η³-cin)(μ-Cl)]₂, [Pd(IPr)(η3-cin)Cl] (1a) was obtained with a promising 1H NMR conversion of 76%. Encouraged by this result, we tested the synthesis of [Au(IPr)Cl] (2a) with [Au(DMS)Cl] (DMS = dimethylsulfide) as the metal source, which resulted in a 100% conversion (See Supplementary information for detailed experimental procedures). However, despite these positive outcomes and simple operation, we soon encountered some issues: (1) Insoluble solid formation (NH4Cl) was inevitable as a by-product even though there are no solid starting materials. (2) The tube-in-tube membrane became fragile under this condition over time and was not suitable for continuous operation with an extended time period. Although the operation remained “acceptable” without severe clogging, the formation of solid NH₄Cl in the tubing could affect reaction reproducibility by raising pressure in the tubing or slowing the streams. To address this, we identified the critical role of water in maintaining a solid-free regime. Consequently, aqueous ammonia (NH3 aq.) was employed as a weak base. This reagent has previously shown promising results in batch syntheses of various metal NHC complexes (metal = Cu15, Ag16, Au14, and Pd17,18). Furthermore, more importantly, its aqueous nature was expected to support the formation of a homogeneous, solid-free system. We first designed the reactor as follows: the reaction mixture containing metal sources and NHC·HCl in an organic solvent, and aqueous ammonia solution were separately injected at the same flow rate by different syringe pumps. After combining these streams at the T-shaped mixer, the mixture went through a reaction coil (2 mL), which was submerged in a water bath at the desired temperatures (Scheme 4).

Schematic of the flow reactor with aqueous ammonia solution as a weak base. This diagram depicts the liquid-liquid flow reactor setup where a stream of NHC·HCl and metal source in an organic solvent and a separate stream of aqueous ammonia are combined via a T-mixer and passed through a temperature-controlled reaction coil.

With this setup, we initiated the study by examining the feasibility of synthesizing [Pd(IPr)(η3-cin)Cl] (1a) at room temperature. For optimization, some parameters were evaluated: the concentrations of the reaction mixture stream (X1), the concentration of aqueous ammonia solution (X2), and residence time RT which is directly related to the flow rate (Table 2).

In the initial experiment, a promising 62% conversion was achieved when using a three-times more concentrated aqueous ammonia solution than the reaction mixture stream (Table 2, Entry 1,). Both increasing the residence time and further concentrating the aqueous ammonia solution improved conversion (Table 2, entries 2 and 3), with concentration increase having a slightly greater impact. This observation prompted the simultaneous concentration of both streams, ultimately leading to full conversion (Table 2, entry 4). Notably, even at a shorter residence time of just 1 min, full conversion was maintained, corresponding to an efficiency of 53 g/day (Table 2, entry 5). It is worth mentioning that throughout these experiments, unlike the tube-in-tube setup (Scheme 3), no solid formation was observed in the entire system, despite operating at a higher concentration (0.06 M) than the current benchmark protocol (0.03 M in acetone), underscoring the efficiency and greener nature of this method25. These initial results encouraged us to examine the reaction condition for a few more variations of [Pd(NHC)(η3-R-allyl)Cl] complexes with different NHC structures, namely the less bulky IMes (IMes = 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene) and bulkier IPr* (IPr* = 1,3-bis(2,6-bis(diphenylmethyl)-4-methylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene) ligands, and a different type of throw-away ligand η3-allyl, instead of η3-cinnamyl.

For the η3-cinnamyl complexes with different NHC ligands, the corresponding Pd complexes (1b and 1c) were obtained with complete conversions and excellent yields (Scheme 5, for detailed reaction conditions, see the Supplementary information). It should be noted that this study represents the first report of preparing these complexes under flow conditions. Moreover, it is important to mention that while the poor solubility of IPr*·HCl in acetone necessitated the use of 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) as the solvent, this choice enabled the application of a membrane-based in-line extractor (Zaiput technology)30,31,32, allowing seamless separation of the product from the aqueous stream and significantly simplifying the workup. For the complex featuring a different throw-away ligand, η3-allyl (1d), complete conversion could not be achieved despite screening various conditions (see Supplementary information, Table S1 for the screening). Considering the importance of [Pd(NHC)(η3-R-allyl)Cl] species as a powerful catalyst (for instance, catalyst loading as low as 0.5 mol% of [Pd(IPr)(η3-cin)Cl] (1a) is often sufficient for simple Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions between (hetero)arylhalides and (hetero)arylboronic acids)18,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, and to examine the robustness of this reactor setting, an experiment with an extended operation time (60 min) was performed for a gram-scale preparation of [Pd(IPr)(η3-cin)Cl] catalyst (1a) under the condition of Entry 4 in Table 2. As expected from the appearance of the reaction stream (a yellow solution) and the absence of a solid component, the current setup maintained a complete conversion for at least 60 min, affording 1 g of catalyst 1a (90% isolated yield), a quantity sufficient for approximately 600 standard Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling runs at a 0.5 mol% catalyst loading (0.5 mmol scale). Thus, a single-hour of operation is sufficient to produce a multi-year supply of the catalyst for most research laboratories with our setup.

These results further encouraged us to examine other metals for the synthesis of [M(NHC)Cl] complexes, namely M = Au and Cu. The continuous-flow synthesis of [Au(NHC)Cl] (2a) is particularly challenging due to the tendency of the gold species to form insoluble nanoparticles, which can cause clogging or damage to the system, especially when solid base plugs are employed25,26. For the synthesis of [Au(IPr)Cl], we began by applying the optimized condition established for [Pd(IPr)(η³-cin)Cl] synthesis (Table 2, entry 5). Under these conditions, a promising but incomplete 70% conversion was obtained (Table 3, entry 1). Unlike the palladium system, increasing the residence time had minimal impact on conversion (70% vs 73%; Table 3, entries 1 and 2). In contrast, increasing the concentration of both streams significantly improved the outcome. Eventually, complete conversion was achieved when the reaction mixture concentration was raised from 0.12 to 0.20 M (Table 3, entries 3–5), with the efficiency under these conditions of entry 5 reaching 161 g/day. Notably, this concentration matches the one typically used in batch syntheses of [Au(NHC)Cl]¹² complexes and is substantially higher than that employed in the current benchmark flow protocol (0.01 M in acetone), representing a 20-fold increase25. Furthermore, no precipitation of NH₄Cl salt or formation of Au nanoparticles was observed throughout the system, underscoring the robustness and practicality of the methodology.

Subsequently, the continuous-flow synthesis of [Cu(IPr)Cl] (3a) was examined (Table 4). Being the same as the gold and palladium cases, copper source, CuCl, and IPr·HCl were mixed in acetone before injection to form the cuprate species, which is the operating starting material in the reaction5,25. However, initially, the insolubility of CuCl in acetone led to the incomplete formation of the cuprate complex with some CuCl remaining undissolved in the reaction mixture. This required a diluted system compared to the gold and palladium systems, and resulted in a significantly lower conversion (Table 4, entry 1). It should be noted that although the operation was acceptable, the stream was partially blocked and had a slower flow rate due to the insoluble CuCl in the system. To address this issue, we envisioned the use of a copper source that would be more soluble in organic solvents, namely, [Cu(DMS)Cl]. We were inspired by the significantly more concentrated condition of the gold system and suspected that it could be realized by the use of an acetone-soluble metal source. To the best of our knowledge, there is no example of the use of [Cu(DMS)Cl] for the synthesis of [Cu(NHC)Cl] complexes at this time. To our satisfaction, the solubility test revealed that a mixture of IPr·HCl and [Cu(DMS)Cl] in acetone formed a clear yellow solution with significantly higher concentration compared to the CuCl system (0.03 M vs 0.20 M, Table 4, entries 1 and 2). Utilizing this concentrated solution led to a markedly higher conversion of 84% (Table 4, entry 2). Increasing or decreasing the concentration of aqueous ammonia solution led to a lower conversion (Table 4, entries 3 and 4). The lower conversion of entry 4 in Table 4 could be attributed to the formation of characteristic blue-colored CuII-ammine complexes due to the increased concentration of aqueous ammonia solution, resulting in the depletion of the Cu source15. Eventually, the condition of entry 2 in Table 4 was identified as an optimized condition, and the product [Cu(IPr)Cl] (3a) was obtained with an isolated yield of 75%.

Lastly, the possibility of the functionalization of [Cu(IPr)Cl] complex was investigated. In this context, carbene-metal-amido (CMA) complexes of coinage metals (Cu, Ag, and Au) stand out among numerous derivatives for their promising catalytic, biological, and photophysical behavior40,41,42. The continuous flow synthesis of [Cu(IPr)CBZ] (CBZ = carbazolyl) (3b) was chosen to test the applicability of this set-up (Table 5). The initial trial (Table 5, entry 1) showed a promising 67% conversion. However, it was found that the low solubility of the product under these conditions caused clogging and a stoppage of the stream. To address this, a 1:1 mixture of acetone and ethyl acetate was employed as a solvent, which successfully dissolved all reaction participants, including the product. This adjustment enabled the use of a higher reaction concentration and improved the conversion to 76% (Table 5, entry 2). Further modifications, including increasing the residence time, the concentration of the aqueous ammonia stream, or the equivalents of carbazole (Table 5, entries 3–5), had little effect on the overall conversion. The influence of reaction temperature was then investigated across the range of room temperature to 50 °C (Table 4, entries 2, 6 and 7). An optimal temperature of 40 °C was identified, delivering an excellent 92% conversion (Table 5, entry 6). In contrast, a decreased conversion of 78% was obtained at 50 °C (Table 5, entry 7) was likely due to reduced solubility of ammonia at elevated temperature.

Conclusions

In summary, a liquid-liquid flow reactor employing the economical weak base aqueous ammonia overcomes the limitations of solid-phase flow systems and enables a more efficient synthesis of a wide range of metal-NHC complexes. It is important to note that this aqueous weak base is not only economical, but the aqueous nature of the reagent also maintains the homogeneous property of the reaction stream by dissolving the by-product salt. This approach allowed for the preparation of both established complexes and several new ones not previously accessible in flow. Notably, the same reactions in batch require significantly harsher conditions (refluxing acetone, 1–24 h). Especially, in the case of the [Au(IPr)Cl] synthesis, the milder conditions not only prevented gold nanoparticle formation but also enabled a reaction system 20 times more concentrated than the previous solid-phase flow system, further highlighting the greener and more sustainable nature of this method. We believe that this study further enhances the attractiveness and accessibility of flow-based synthesis of metal-NHC complexes for both industrial and academic researchers, thereby facilitating the exploration of their broad spectrum of applications and the discovery of new reactivity horizons.

Methods

General procedure for the synthesis of metal NHC complexes with gaseous NH3

As shown in Scheme 3, the tube-in-tube reactor (1 mL) was immersed in an ice bath, while the additional reaction coil (5 mL) was placed in a water bath maintained at 40 °C. Ammonia gas (3.5 bar) was introduced into the space between the inner and outer tubings of the tube-in-tube reactor, allowing it to permeate through the membrane and be continuously supplied to the liquid reaction mixture flowing through the inner tubing. After passing through the additional reaction coil, the reaction stream was collected and concentrated under reduced pressure. After being dissolved in DCM, the mixture was filtered through a pad of silica gel, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was washed with pentane, and the desired product was obtained after drying under high vacuum.

General procedure for the synthesis of metal NHC complexes with aqueous NH3

As shown in Scheme 4, the flow reactor coil was dipped in a water bath to maintain the temperature of 25 °C. A solution of NHC·HCl and metal source in acetone and an aqueous ammonia solution were introduced to the reactor by syringe pumps at desired flow rate (See Supplementary information for the concentrations of each stream and flow rates). After capturing the crude mixture, it was concentrated under reduced pressure. Subsequently, the mixture was transferred to a separation funnel and extracted with EtOAc. The collected organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The desired metal NHC product was obtained after drying under high vacuum.

Data availability

All data produced during this study, including detailed experimental procedure, condition optimization, and NMR spectra are contained in this article and Supplementary Information.

References

Díez-González, S., Marion, N. & Nolan, S. P. N-heterocyclic carbenes in late transition metal catalysis. Chem. Rev. 109, 3612–3676 (2009).

Hopkinson, M. N., Richter, C., Schedler, M. & Glorius, F. An overview of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Nature 510, 485–496 (2014).

Cauwenbergh, T. et al. Continuous flow synthesis of NHC-coinage metal amido and thiolato complexes: a mechanism-based process development. Chem. Methods 2, e202100098 (2022).

Scattolin, T. & Nolan, S. P. Synthetic routes to late transition metal–NHC complexes. Trends in Chemistry 2, 721–736 (2020).

Martynova, E. A., Tzouras, N. V., Pisanò, G., Cazin, C. S. J. & Nolan, S. P. The “weak base route” leading to transition metal–N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Chem. Commun. 57, 3836–3856 (2021).

Arduengo, A. J., Harlow, R. L. & Kline, M. A stable crystalline carbene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 361–363 (1991).

De Frémont, P., Scott, N. M., Stevens, E. D. & Nolan, S. P. Synthesis and structural characterization of N-heterocyclic carbene Gold(I) complexes. Organometallics 24, 2411–2418 (2005).

Chartoire, A. et al. Recyclable NHC catalyst for the development of a generalized approach to continuous Buchwald–Hartwig reaction and workup. Org. Process Res. Dev. 20, 551–557 (2016).

Lin, I. J. B. & Vasam, C. S. Preparation and application of N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of Ag(I). Coord. Chem. Rev. 251, 642–670 (2007).

Furst, M. R. L. & Cazin, C. S. J. Copper N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) complexes as carbene transfer reagents. Chem. Commun. 46, 6924 (2010).

Visbal, R., Laguna, A. & Gimeno, M. C. Simple and efficient synthesis of [MCI(NHC)] (M = Au, Ag) complexes. Chem. Commun. 49, 5642 (2013).

Collado, A., Gómez-Suárez, A., Martin, A. R., Slawin, A. M. Z. & Nolan, S. P. Straightforward synthesis of [Au(NHC)X] (NHC = N-heterocyclic carbene, X = Cl, Br, I) complexes. Chem. Commun. 49, 5541 (2013).

Scattolin, T., Tzouras, N. V., Falivene, L., Cavallo, L. & Nolan, S. P. Using sodium acetate for the synthesis of [Au(NHC)X] complexes. Dalton Trans. 49, 9694–9700 (2020).

Saito, R. et al. Simple synthesis of [Au(NHC)X] complexes utilizing aqueous ammonia: revisiting the weak base route mechanism. Dalton Trans. 54, 59–64 (2025).

Gibard, C., Ibrahim, H., Gautier, A. & Cisnetti, F. Simplified preparation of Copper(I) NHCs using aqueous ammonia. Organometallics 32, 4279–4283 (2013).

Gibard, C. et al. Access to silver-NHC complexes from soluble silver species in aqueous or ethanolic ammonia. J. Organomet. Chem. 840, 70–74 (2017).

Saito, R. et al. Facile and green synthesis of [Pd(NHC)(η3 -R-allyl)Cl] complexes and their anticancer activity. Dalton Trans. 54, 11720–11724 (2025).

Carì, G. et al. Well-defined [Pd(NHC)(η3-methylnaphthyl)Br] complexes in cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 31, e202501967 (2025).

Plutschack, M. B., Pieber, B., Gilmore, K. & Seeberger, P. H. The Hitchhiker’s guide to flow chemistry. Chem. Rev. 117, 11796–11893 (2017).

Movsisyan, M. et al. Taming hazardous chemistry by continuous flow technology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 4892–4928 (2016).

Seghers, S. et al. Design of a mesoscale continuous-flow route toward lithiated methoxyallene. ChemSusChem 11, 2248–2254 (2018).

Giraudeau, P. & Felpin, F.-X. Flow reactors integrated with in-line monitoring using benchtop NMR spectroscopy. React. Chem. Eng. 3, 399–413 (2018).

Annunziata, F., Guaglio, A., Conti, P., Tamborini, L. & Gandolfi, R. Continuous-flow stereoselective reduction of prochiral ketones in a whole cell bioreactor with natural deep eutectic solvents. Green Chem. 24, 950–956 (2022).

Opalka, S. M., Park, J. K., Longstreet, A. R. & McQuade, D. T. Continuous synthesis and use of N -N-heterocyclic carbene Copper(I) complexes from insoluble Cu2 O. Org. Lett. 15, 996–999 (2013).

Simoens, A. et al. Continuous flow synthesis of metal–NHC complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 5653–5657 (2021).

Jónsson, H. F., Fiksdahl, A. & Harvie, A. J. Rapid and mild synthesis of Au–NHC complexes in a simple two-phase flow reactor. Dalton Trans. 50, 7969–7975 (2021).

Brzozowski, M., O’Brien, M., Ley, S. V. & Polyzos, A. Flow Chemistry: intelligent processing of gas–liquid transformations using a tube-in-tube reactor. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 349–362 (2015).

Han, S., Kashfipour, M. A., Ramezani, M. & Abolhasani, M. Accelerating gas–liquid chemical reactions in flow. Chem. Commun. 56, 10593–10606 (2020).

Cranwell, P. B. et al. Flow synthesis using gaseous ammonia in a Teflon AF-2400 tube-in-tube reactor: Paal–Knorr pyrrole formation and gas concentration measurement by inline flow titration. Org. Biomol. Chem. 10, 5774 (2012).

O’Hanlon, D., Davin, S., Glennon, B. & Baumann, M. Metal-free [2+2]-photocycloaddition of unactivated alkenes enabled by continuous flow processing. Chem. Commun. 61, 1403–1406 (2025).

Molnár, M. et al. Continuous flow for the photochemical synthesis of 3-substituted quinolines. Org. Process Res. Dev. 29, 1237–1247 (2025).

Allred, T. K. et al. Continuous preparation of trifluoromethyl diazomethane in flow using in-line membrane phase separation─application to the catalytic asymmetric cyclopropanation of substituted styrenes. Org. Process Res. Dev. 29, 716–722 (2025).

Zinser, C. M. et al. A simple synthetic entryway into palladium cross-coupling catalysis. Chem. Commun. 53, 7990–7993 (2017).

Izquierdo, F. et al. Insights into the catalytic activity of [Pd(NHC)(cin)Cl] (NHC=IPr, IPrCl, IPrBr) complexes in the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction. ChemCatChem 10, 601–611 (2018).

Chartoire, A. et al. [Pd(IPr*)(cinnamyl)Cl]: an efficient pre-catalyst for the preparation of tetra-ortho-substituted biaryls by Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 4517–4521 (2012).

Martin, A. R., Chartoire, A., Slawin, A. M. Z. & Nolan, S. P. Extending the utility of [Pd(NHC)(cinnamyl)Cl] precatalysts: direct arylation of heterocycles. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 8, 1637–1643 (2012).

Li, G. et al. Buchwald–Hartwig cross-coupling of amides (transamidation) by selective N–C(O) cleavage mediated by air- and moisture-stable [Pd(NHC)(allyl)Cl] precatalysts: catalyst evaluation and mechanism. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10, 710–716 (2020).

Lei, P. et al. Green solvent selection for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling of amides. ACS Sust. Chem. Eng. 9, 552–559 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of 2-Pyridyl trimethylammonium salts by N–C activation catalyzed by air- and moisture-stable Pd–NHC precatalysts: application to the discovery of agrochemicals. Org. Lett. 25, 2975–2980 (2023).

Ibni Hashim, I. et al. Synthesis of Carbene-Metal-Amido (CMA) complexes and their use as precatalysts for the activator-free, gold-catalyzed addition of carboxylic acids to alkynes. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202201224 (2022).

Tzouras, N. V. et al. A green synthesis of carbene-metal-amides (CMAs) and carboline-derived CMAs with potent in vitro and ex vivo anticancer activity. ChemMedChem 17, e202200135 (2022).

Ying, A. & Gong, S. A rising star: luminescent carbene-metal-amide complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202301885 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The FWO is gratefully acknowledged for support of this work (G0A6823N). Umicore AG is thanked for its continued support through generous gifts of materials. Ghent University is acknowledged for an assistant mandate to A.S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S. contributed to the conceptualization, the experimental part, organization, and writing of the manuscript. A.S. and C.V. assisted with the experimental part and writing of the manuscript. C.V.S. and S.P.N. contributed to the conceptualization, organization, and writing of the manuscript and secured funding for the implementation of this project. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, R., Simoens, A., Vandersteen, C. et al. Ammonia as a weak base for continuous-flow synthesis of Au, Pd, and Cu-NHC heteroleptic chloro complexes. Commun Chem 9, 56 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01862-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01862-y