Abstract

Maritime activity in the Arctic is increasing, and climate change projections suggest that commercial vessels may soon have seasonal access to high-latitude waters. Accurate assessments of Arctic marine access are essential, yet the ability of climate models to reproduce historical navigability remains underassessed. Here, we show that the multi-model mean of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) underestimates overall Arctic navigability, despite capturing historical changes in summer navigable areas. Since the early 21st century, the multi-model mean underestimates the length of the shipping season in many regions of the Arctic Ocean, following a dipole-like pattern for moderately ice-strengthened vessels, with underestimates in the East Siberian and Laptev Seas, and overestimates in the Kara and Barents Seas. Moreover, inaccurate ice thickness simulations hinder the identification of trans-Arctic routes through the Northwest Passage. Improved simulation of ice concentration has a greater impact on assessing the length of the shipping season for ordinary ships, while improvements in ice thickness substantially improve the assessments for ice-strengthened ships. Better simulation of ice thickness is critical for accurately identifying trans-Arctic routes for both types of vessels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Arctic is warming at nearly three to four times the global average1,2, resulting in significant reductions in sea ice area and volume in recent decades3,4,5. A regime shift in ice thickness occurred in 20076, further increasing the navigability of Arctic waters (see Supplementary Figs. 1–3 and Supplementary Note 1). The Northeast Passage (NEP) and the Northwest Passage (NWP) have emerged as geographic shortcuts between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, offering potential alternatives to traditional shipping routes7,8. The economic benefits, together with governance frameworks such as Article 234 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), have influenced the expansion of Arctic shipping activity9,10,11,12. For example, the cargo transiting the NEP has increased from 7.5 million tons in 2016 to 31.5 million tons in 201910, while the distance traveled by ships in the Canadian Arctic almost tripled between 1990 and 20159.

The latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC - Sixth Assessment Report (AR6)) states that the Arctic Ocean is likely to become ice-free in summer before 205013, with recent projections suggesting that this could occur earlier, even under low-emission scenarios14,15,16. In addition, the ice-free season may extend into autumn, driven by the thermodynamic response of seasonal ice to the warming14,17. These projections highlight a significant extension of the open-water periods in the Arctic by the end of this century18,19, which has attracted the interest of policymakers, stakeholders, and the scientific community20,21.

Assessments of Arctic shipping potential have often relied on projections from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phases 5 and 6 (CMIP5/6). In the NEP, NWP, and Transpolar Sea Route, transit times are expected to decrease, especially for Open Water (OW, without hull ice-strengthening) vessels, as sea ice area and volume continue to decrease22,23,24. Under the extreme greenhouse gas (GHG) emission scenario SSP5-8.5, Polar Class 6 (PC6, medium ice-strengthened) ships are projected to achieve year-round navigation by the 2070s, even without icebreaker support23,25. Under the lower-emission scenario SSP1-2.6, ordinary ships could begin navigating the central Arctic Ocean in the 2040s23,26. In addition, the increased usability of the Transpolar Sea Route is expected to divert traffic from the coastal Northern Sea Route, resulting in shorter voyages and lower shipping costs26,27.

Although the inter-model variability is reduced in the CMIP6 projections28,29,30, uncertainties remain in the simulation of Arctic sea ice, especially with respect to thickness31,32. This raises an important question: how well do CMIP6 models reproduce historical changes in Arctic navigability? Answering this question is crucial for refining future projections and supporting Arctic shipping route planning. To this end, we assess the performance of CMIP6-based navigability estimates against reference data (REF), using sea ice thickness data from the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS)33 and remotely sensed sea ice concentration data processed by the Ocean and Sea Ice Satellite Application Facility (OSI SAF)34.

Results

Reproduction of summer shipping areas by CMIP6

Analysis of Arctic shipping activity indicates that the majority of operations occur during the summer months, July to October10,11,35. Accordingly, the navigable area during this period is used as a proxy to assess the feasible operating areas for vessels of the class PC6 (Fig. 1a–d) and OW (Fig. 1e–h). As shown in Fig. 1, the navigable areas derived from the CMIP6 multi-model mean (MMM) agree well with those derived from the REF. This agreement is particularly pronounced for OW ships, highlighting the ability of the CMIP6 MMM to capture broad navigable area trends. Several individual CMIP6 models, such as CESM2-WACCM, E3SM-1-1-ECA, EC-Earth-AerChem, GFDL-CM4, and HadGEM3-GC31-LL, also closely match the REF results (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5). However, there are considerable inter-model differences, especially for PC6 ships, for which some models (e.g., CNRM-ESM2-1, CNRM-CM6-1-HR, and NorCPM1; see Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 2 for detailed comparison) substantially over- or underestimate navigability. This highlights the challenges climate models face in accurately simulating sea ice thickness (SIT), a key factor in estimating navigable areas for ice-strengthened ships such as PC6 ships, which have moderate ice-breaking capabilities (SIT < 120 cm). The marked decline in sea ice thickness since 2007 has further accentuated the differences between MMM- and REF-derived navigable areas, especially for PC6 ships. The MMM struggles to reproduce this abrupt thinning, resulting in underestimates of navigable areas during key shipping months. For example, after 2007, the average navigable areas for PC6 ships in July, August, September, and October are approximately 8.76 × 106 km2 (64.4% of the Arctic Ocean), 10.71 × 106 km2 (78.7%), 10.99 × 106 km2 (80.8%), and 10.69 × 106 km2 (78.5%), respectively. In contrast, the MMM estimates are only 7.65 × 106 (56.2%) km2, 9.98 × 106 km2 (73.3%), 10.35 × 106 km2 (76.1%), and 9.44 × 106 km2 (69.3%), respectively.

While the MMM tends to slightly underestimate navigable areas, our results indicate that state-of-the-art CMIP6 models are generally able to capture long-term trends in navigable areas, one of the key navigation metrics. This underestimation may be due to the higher values observed in the REF, which includes both internal climate variability and the GHG-induced climate trend5,36,37. The internal variability in the different CMIP6 simulations is model-dependent and can, therefore, be assumed to be uncorrelated over time, leading the MMM to filter out this intrinsic variability. However, the difference between the REF and the MMM seems to have ceased for the last years of the CMIP6 historical run, as can be seen in all panels of Fig. 1. This suggests that fully coupled climate models can reproduce long-term changes in the navigable area. However, additional key metrics such as the length of the shipping season, planning for the fastest trans-Arctic routes, and quantification of transit times still require further evaluation for Arctic marine operations. Accordingly, we expand our assessment to include these metrics, comparing Arctic navigability derived from REF and MMM. This comparison leverages the MMM’s strong ability to reproduce summer navigable areas from REF, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 4, 5. The MMM is therefore treated as a proxy for CMIP6 models’ representation of Arctic marine access in response to anthropogenic forcing (see Supplementary Note 2 for a detailed discussion).

Underestimation of the Arctic shipping season by MMM

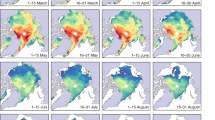

Analysis of shipping season lengths for PC6 and OW vessels over three time periods − 1979 to 1989, 1990 to 1999, and 2000 to 2014 - shows a clear spatial pattern of underestimation and overestimation by the CMIP6 MMM (Fig. 2). Positive (\({R}_{{PD}}\)) and negative (\({R}_{{ND}}\)) ratios were used to quantify the differences relative to the total area of the Arctic Ocean (see Materials and Methods for exact definitions). For PC6 ships (Fig. 2a–c), underestimates (\({R}_{{ND}}\)) occur mainly in the Greenland Sea, the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, and near the New Siberian Islands. In contrast, the MMM tends to overestimate (\({R}_{{PD}}\)) the shipping season in the Kara and Barents Seas, especially in the earlier periods (1979 to 1989, and 1990 to 1999). In the NEP, a clear dipole pattern emerges: underestimations are concentrated in the East Siberian and Laptev Seas, while overestimations are prominent in the Kara and Barents Seas (Fig. 2a–c). Over time, the extent of underestimation has increased substantially, from –24.9% in 1979–1989 and –29.2% in 1990–1999 to –40.8% in 2000–2014. In the most recent period, the area of underestimation was about three times larger than the area of overestimation.

a–c show differences for Polar Class 6 (PC6) ships, and d–f for Open Water (OW) ships. \({R}_{{PD}}\) and \({R}_{{ND}}\) represent the ratios of areas with positive and negative differences, respectively, relative to the total Arctic Ocean area north of the Arctic Circle (at 66°34’ marked as a dashed circle in a). Numbers in orange in a denote analyzed regions: 1—Beaufort Sea, 2—Chukchi Sea, 3—East Siberian Sea, 4—Laptev Sea, 5—Kara Sea, 6—Barents Sea, 7—Greenland Sea, 8—Baffin Bay, 9—Canadian Arctic Archipelago, and 10—Central Arctic. The black star indicates the North Pole.

A similar pattern is observed for OW vessels (Fig. 2d–f), where the \({R}_{{ND}}\) area exceeds the \({R}_{{PD}}\). However, a key difference is present in the Barents Sea, where the MMM underestimates the navigable season for OW vessels while overestimating it for PC6 vessels. In addition, the magnitude of both underestimation and overestimation across the Arctic is generally less pronounced for OW than for PC6 vessels. Our analysis indicates that the MMM has difficulty capturing changes in shipping season length, leading to an overall underestimation of Arctic marine access. While this tendency may also appear in future scenario projections—particularly under lower emission scenarios (see Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 2 for a detailed discussion)—we advise caution in applying these results to the present-day Arctic, due to uncertainties related to the temporal limitations of CMIP6 historical simulations, which end in 2014.

Efficient trans-Arctic shipping routes derived from MMM and REF

The fastest available trans-Arctic shipping routes and their associated transit times are critical metrics for Arctic navigation. Both REF- and MMM-derived results indicate that August and September provide the most favorable conditions for shipping (Fig. 3), consistent with observed peaks in Arctic shipping activity during these months10,11,12. Conversely, July exhibits the lowest navigability, with few REF-derived and no MMM-derived trans-Arctic routes identified for OW vessels (Fig. 3e). For both types of vessels, MMM-derived trans-Arctic routes are completely absent in the NWP throughout the summer season, in contrast to the presence of REF-derived routes. This gap is likely due to limitations of the CMIP6 models in simulating localized sea ice thinning, especially in narrow straits where multi-year ice tends to accumulate38. In the NEP, MMM-derived routes are southward biased, clustering near the East Siberian and Laptev Seas, while REF-derived routes are more widely distributed, reflecting interannual sea ice variability. This suggests that the MMM-based analysis tends to underestimate the increasing navigability of marginal Arctic seas.

Furthermore, statistical analysis of transit times (Fig. 4) shows that values derived from the MMM are generally longer than those based on REF. This overestimation is more pronounced for OW vessels than for PC6 vessels (see Supplementary Table 6 for a detailed comparison). For example, in September, the median MMM-derived transit time for PC6 vessels transiting the NEP is 17.7 days, while the REF-derived median is 17.1 days. However, for OW ships, the MMM-derived transit times are markedly longer (23.9 days), compared to 17.8 days REF-derived. Similarly, in the NWP, where MMM-derived routes require detours through the NEP, transit times for PC6 ships are extended to 21.3 days, compared to REF-derived 15.8 days. For OW vessels, the MMM-derived median transit time exceeds the REF-derived time by approximately 11 days.

a–d show results for Polar Class 6 (PC6) ships; e–h for Open Water (OW) ships. Violin plots represent transit times (days) for routes between St. John’s and the Bering Strait (left subplot) and between Rotterdam and the Bering Strait (right subplot), based on both the multi-model mean (MMM) and the reference dataset (REF). In each violin plot, the black solid line indicates the median, and black dashed lines denote the quartiles.

Improving Arctic navigability assessments

Accurate assessments of Arctic Ocean accessibility are essential for strategic planning of future maritime operations. Given the central role of sea ice concentration and thickness in accessibility models (e.g., ATAM and POLARIS), we conducted two targeted experiments (Opt_SIC and Opt_SIT; see Supplementary Table 7) to refine these key variables and identify ways to improve assessment accuracy. In Opt_SIC, we improved sea ice concentration using satellite observations, while maintaining the MMM sea ice thickness. Conversely, in Opt_SIT, we refined sea ice thickness using PIOMAS data, while maintaining sea ice concentration at the MMM values. These experiments allowed us to evaluate how improvements in these variables can contribute to more reliable assessments of Arctic navigability.

Since the MMM adequately reproduces historical navigable areas (Fig. 1), we shift our focus to other critical navigation metrics. Results for the shipping season length are shown in Fig. 5a, b and summarized in Table 1. In OPT_SIC, refinement of sea ice concentration led to moderate improvements in the shipping season length for PC6 vessels, while more substantial improvements were observed for OW vessels. For instance, during 2000–2014, the positive (\({R}_{{PD}}\)) and negative (\({R}_{{ND}}\)) MMM ratios for OW vessels were reduced from +10.9% and –32.0% to +0.4% and –10.3% in OPT_SIC (Table 1). In OPT_SIT, these ratios remained at +12.3% and –13.4%. However, the changes in sea ice thickness in OPT_SIT substantially improved the accuracy of the length of the shipping season, especially for PC6 vessels. During the same time period, for PC6 vessels, \({R}_{{PD}}\) and \({R}_{{ND}}\) were reduced from +15.5% and –40.8% (MMM) to +5.6% and –1.1% in OPT_SIT, while these ratios remained relatively unchanged at +12.7% and –39.3% in OPT_SIC.

a and b present the ratios of positive (\({R}_{{PD}}\)) and negative (\({R}_{{ND}}\)) differences for Polar Class 6 (PC6) and Open Water (OW) ships. These ratios are calculated against the reference dataset (REF). A ratio of 0 suggests the experiment closely matches REF results. c–f illustrate improvements in estimating the fastest trans-Arctic shipping routes in October, derived from optimizing sea ice concentration (Opt_SIC) and thickness (Opt_SIT), respectively. The black pentagram shows the location of the North Pole.

Further improvements were observed in the estimation of the fastest trans-Arctic shipping routes (Fig. 5c–f). While the changes in sea ice concentration in OPT_SIC led to better route estimation in August and September, especially in the NWP, the routes derived from OPT_SIT showed stronger agreement with the REF-derived estimates, especially for PC6 and OW ships in October in the NWP (see Fig. 5e, f, and Supplementary Fig. 8). These results suggest that improvements in sea ice thickness play a more critical role in accurately estimating trans-Arctic shipping routes than improvements in sea ice concentration alone.

Potential to improve sea ice simulations

High-resolution (HR) simulations have the potential to improve the representation of Arctic sea ice thickness and concentration, especially in narrow passages, and to improve the horizontal heat advection from the Atlantic to the Arctic due to better resolved eddy transport39. Given the critical role of sea ice for Arctic shipping (Fig. 5), we assess the impact of model resolution using results from the High-Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP) within CMIP6. The analysis focuses on mean sea ice thickness and concentration for September, the peak season for Arctic shipping, over the period 1979–2014 (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 7).

a and b show the differences in mean sea ice thickness (SIT) between the HR simulations and PIOMAS, and between the LR simulations and PIOMAS, respectively. c illustrates the changes in SIT bias with higher model resolution, where negative values indicate improvement (Impv). d–f present analogous analyses to (a–c), focusing on sea ice concentration (SIC) instead of SIT.

The results show that HR configurations improve the representation of mean sea ice thickness in the central Arctic, Laptev Sea, and Kara Sea compared to low-resolution (LR) configurations. However, these improvements are geographically limited and not evident in the Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, East Siberian Sea, and Canadian Arctic Archipelago, where HR simulations are less accurate than LR configurations (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 7). Additionally, both HR and LR simulations overestimate the mean sea ice thickness in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago compared to PIOMAS (Fig. 6a and b), which contributes to the absence of trans-Arctic routes through the NWP in the MMM assessment (Fig. 3). For sea ice concentration, HR simulations show notable improvements in the marginal seas along the NEP, particularly in the representation of the sea-ice edge (Fig. 6f), which is critical for OW vessels. This improvement is likely related to more accurate meridional heat transport in the HR models39. However, consistent improvements are not seen in other regions of the Arctic Ocean, with both HR and LR simulations underestimating mean sea ice concentration over much of the Arctic (Fig. 6d, e). Further comparison of individual HR and LR simulations with reference datasets suggests that LR configurations generally provide a more accurate representation of Arctic sea ice characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 7), with the exception of the HadGEM3-GC31-HM model, which likely provides a more accurate representation than its LR counterpart, HadGEM3-GC31-LL. These results are in agreement with previous studies39,40.

Our results indicate that increasing model resolution alone does not consistently improve Arctic sea ice simulations for marine access assessments. To improve model performance, efforts should focus on advancing sea ice physics and parameterizations40. In addition, observationally derived insights into the coupled interactions among the ocean, sea ice, and atmosphere are essential for improving simulations of Arctic climate and enhancing their reliability.

Discussion

The continued reduction of sea ice and the projected prolongation of Arctic shipping seasons under climate change are expected to increase maritime traffic in the region (see Supplementary Figs. 1–3 and Supplementary Note 1)20,22,26,27. However, assessments of Arctic shipping potential have largely relied on the outputs of climate models, with only limited assessment of the accuracy of these models in representing historical navigability. This study evaluates Arctic navigability derived from 41 CMIP6 models and their MMM, benchmarked against REF-based Arctic navigability. While the reference data includes widely used and validated PIOMAS sea ice thickness and satellite-derived sea ice concentration datasets, some uncertainty remains in the REF-based assessments. For example, PIOMAS tends to overestimate the thickness of thin ice33,41, which may result in a slight underestimation of the shipping season for both OW and PC6 vessels42. Despite these uncertainties, PIOMAS remains among the longest and most reliable sea ice thickness datasets available for long-term analyses. Moreover, inconsistencies in sea ice coverage within the marginal ice zone between the OSISAF and PIOMAS datasets may contribute slightly to the overall uncertainty.

We find that improving the simulation of sea ice thickness substantially increases the accuracy of navigability assessments. Therefore, advances in sea ice physics and the component interactions in coupled climate models are critical, especially for better simulation of sea ice thickness40,43. To reduce uncertainties in the simulation of Arctic sea ice thickness and its impact on navigability assessments, previous studies have applied statistical corrections to climate model output using PIOMAS data25,44,45, or used an optimized selection of model projections23,26,46. Despite these efforts, uncertainties remain. For example, PIOMAS may overestimate thin sea ice41, leading to inaccuracies in model-corrected outputs and underestimating the accessibility of Arctic seas. This suggests that the opening of the trans-Arctic sea route may occur earlier than previously predicted (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, reliance on a limited selection of models may bias the projections of Arctic navigability23,26,46, highlighting the importance of using a broader selection of models to avoid overly deterministic results in future studies. With advances in artificial intelligence47 and the availability of year-round sea ice thickness records from CryoSat-248, there are opportunities to better constrain climate model simulations, thereby improving the reliability of future projections of Arctic shipping potential.

The MMM-based assessment generally provides a reasonable representation of trends in Arctic navigable areas and captures the long-term impacts of climate change. However, the filtering effect of the MMM reduces inter-annual to decadal variability and obscures inter-model differences26,37,49, that are essential for a comprehensive risk assessment. Future assessments should account for these uncertainties. For example, Black–Scholes analysis offers a promising method to quantify the financial risks associated with interannual sea ice variability26,50, thereby could increase the robustness of accessibility projections and their relevance to Arctic navigation planning.

In addition, accurate subseasonal-to-seasonal sea ice forecasts are crucial for Arctic maritime activities51, especially for vessels with varying ice-strengthened capabilities (Fig. 5 and Table 1). These forecasts optimize navigational strategies and mitigate risks. For OW vessels, accurate forecasts of sea ice concentration are critical, as they operate primarily in ice-free regions and are sensitive to the sea ice edge. In contrast, for ice-strengthened vessels, forecasts of sea ice thickness are equally important, as these ships navigate thicker ice, where thickness directly affects navigational performance. Data assimilation has been shown to be effective in improving sea ice concentration and thickness forecasts by reducing errors in initial conditions52,53,54. For example, assimilation of sea ice observations has improved the forecast accuracy in models such as the AWI Coupled Prediction System55 and the Norwegian Climate Prediction Model56. Using PIOMAS’s sea ice thickness has also improved forecasts of Arctic summer sea ice extent and edge57,58. Multi-model ensemble approaches have further improved forecast accuracy, with ensemble mean forecasts showing the highest skill at lead times of up to four weeks52. These improvements aid the navigation of OW vessels in ice-bound regions. For ice-strengthened vessels, advances in sea ice thickness forecasts are particularly important. Recent developments, such as the assimilation of pan-Arctic CryoSat-2 summer sea ice thickness observations, have improved thickness estimates59 and forecasts of sea ice volume anomalies and edge positions60,61. These advances provide essential guidance for regions with complex ice dynamics and thick ice cover, thereby improving the safety and efficiency of ice-strengthened vessels in Arctic maritime operations on tactical time-scales (up to a season).

The reduction of sea ice has improved access to the Arctic Ocean by reducing the likelihood of encountering ice-related hazards (Supplementary Figs. 1–3)11,12,35. However, as sea ice continues to decline, other environmental factors will play an increasingly important role in Arctic shipping operations. Factors such as ocean waves, sea fog, underwater topography, channel width, and sea ice motion are all critical to safe and efficient navigation22,46,62 and should be considered in future navigability studies63,64. For example, shallow waters restrict the movement of deep-draft ships, while narrow channels are also more prone to ice blockage65. Sea fog, which commonly occurs in certain Arctic regions, affects the navigational conditions for both PC6 and OW vessels62,66. Although PC6 vessels are designed for thicker ice, extreme weather conditions, such as dense fog, can reduce visibility and increase shipping times by 23%–27% along the NEP and 4%–11% along the Northern Sea Route62. In addition, high winds increase risks by increasing spray icing and causing unpredictable shifts in sea ice, further challenging the structural integrity of ships11,67. OW vessels, optimized for open-water navigation, are particularly vulnerable to thick ice and extreme weather conditions. Strong winds and dense fog can reduce speeds, increase collision risks, and cause operational delays. Given that these phenomena occur at spatial scales far finer than those resolved by CMIP6 models, further advancements in numerical modeling are needed.

As shown in Fig. 7, sea ice motion reduces navigational indices and sailing speeds, especially in regions with high ice speeds, such as the Chukchi Sea and Greenland Sea. However, it generally does not change the classification of areas as navigable or non-navigable, with boundaries defined by the Ice Numeral (IN; blue line) and Comprehensive IN (COMIN; red line) remaining largely unchanged. Current formulations of COMIN and the Comprehensive Risk Index Value (COMRIV)46 do not take into account ship-specific icebreaking capabilities or the angular relationship between sea ice motion and a vessel’s heading. These limitations are discussed in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 10 and highlight the uncertainties in navigability assessments based on COMIN and COMRIV. Future research should explore these interactions in more detail, with particular attention to ship-specific characteristics (such as icebreaking ability) and the alignment between sea ice motion and vessel headings.

a shows results for Polar Class 6 (PC6) ships, while b shows results for Open Water (OW) ships. The blue line marks the boundary between navigable and non-navigable areas based on IN, which excludes sea ice motion. The red line represents the navigability boundary derived using COMIN, which incorporates sea ice motion. Note, that the blue line largely overlaps with the red line, i.e., the red line is hardly visible. The white region indicates areas with excessive navigational risk, deemed non-navigable. Shaded regions show the difference between COMIN and IN, with all shaded areas considered navigable. Black arrows indicate sea ice motion within the navigable region.

From an operational perspective, the feasibility of Arctic sea routes is also influenced by a complex interplay of factors beyond sea ice, including economic, geopolitical, and operational considerations26,27,68,69,70. Vessel capabilities, such as Polar Class certification and ice-strengthened hulls, are crucial for safe navigation and have a considerable impact on route viability46,71,72. The limited seasonal accessibility of the Northern Sea Route has led to its predominant use by cargo ships, particularly bulk carriers and tankers that are commonly employed under such conditions69,73. Economic factors, including higher insurance premiums due to Arctic navigation risks, also influence route selection and feasibility70,74,75. Regulatory frameworks, such as Article 234 of the UNCLOS and the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code, provide guidelines to enhance safety and minimize environmental risks in ice-infested waters27,76,77,78. Geopolitical considerations, such as overlapping jurisdictional claims and differing national regulations, further affect Arctic marine access and route viability20,69,79,80. Operational risks, including limited emergency response capabilities and limited port access, present additional challenges that increase safety concerns and complicate logistics69,70,79,81,82. The projected increase in Arctic shipping activity also raises concerns about environmental impacts, particularly increased vessel emissions and their effects on the fragile Arctic ecosystems69,83,84.

A more integrated approach that considers economic, geopolitical, operational, and environmental factors is essential for a comprehensive assessment of Arctic shipping potential. Developing such a framework could provide valuable insights into the long-term sustainability of Arctic shipping and support marine spatial planning85,86, thereby contributing to balancing development opportunities with the challenges of a rapidly changing Arctic environment.

Materials and Methods

Sea ice simulations

Monthly mean sea ice thickness and concentration simulations for the period 1979–2014 were obtained from the CMIP6 historical experiments. The complete list of the models available at the time this study was conducted and used in our analysis is provided in Supplementary Tables 3–5. Most of the 41 simulations used the r1i1p1f1 realization of the CMIP6 models. However, alternative realizations, such as CNRM-CM6-1-HR (r1i1p1f2), CNRM-ESM2-1 (r1i1p1f2), HadGEM3-GC31-LL (r1i1p1f3), HadGEM3-GC31-MM (r1i1p1f3), MIROC-ES2L (r1i1p1f2), and UKESM1-0-LL (r1i1p1f2), were used when the first realizations were not available. In addition, monthly mean sea ice projections under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5) scenario (Supplementary Table 4) are used to compare changes in Arctic navigability under the high-emission scenario with reference data from the overlapping period (2015–2023). To assess the impact of model resolution on Arctic marine access estimates, we analyzed models from the same institutes that provided the historical simulations and participated in the High-Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP), a CMIP6-endorsed initiative offering both low- and high-resolution configurations. In particular, HighResMIP experiments follow the standard CMIP6 resolution configuration40. Detailed information on the HighResMIP models can be found in Supplementary Table 5.

Reference data

To assess the ability of the CMIP6 models to reproduce historical Arctic navigability, we utilized a reference dataset (REF) that consists of sea ice thickness and concentration data. Sea ice thickness data were obtained from the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS), a well-established dataset33. Sea ice concentration observations were obtained from the newly released OSI-450-a dataset34, provided by the Ocean and Sea Ice Satellite Application Facility (OSI SAF). To assess the potential impact of dynamic sea ice changes on accessibility, we also evaluated the influence of sea ice motion in addition to the effects of sea ice thickness and concentration, following the methodology of Zhao et al.46. The sea ice motion data used here, which combine satellite and buoy observations, were provided by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC)87.

Methods for deriving the fastest trans-Arctic routes

Building on previous studies23,42,88,89,90, we interpolate sea ice thickness and concentration from both REF and CMIP6 to a 25×25 km equal-area grid using nearest-neighbor interpolation to match the spatial resolution of the sea ice concentration observations. The Arctic Transportation Accessibility Model (ATAM) was then applied using interpolated sea ice thickness and concentration from the individual CMIP6 models, the CMIP6 multi-model mean (MMM), and REF, respectively. (Differences between ATAM and the Polar Operational Limit Assessment Risk Indexing System, POLARIS, are discussed in the Supplementary Methods).

While ships with higher ice classes offer improved navigation capability in ice-covered waters, their construction costs are notably higher. The Arctic shipping industry is, therefore, expected to strike a balance between operational feasibility and economic efficiency. In this context, we have calculated different Ice Multipliers (IM) for two representative vessel types: Polar Class 6 (PC6, medium ice-strengthened hull) and Open Water (OW, no ice-strengthened hull)88. Specifically, we use IM to differentiate the sailing hazard induced by sea ice thickness (SIT, unit: cm). The variational IMs for OW and PC6 vessels are calculated as follows:

Then the Ice Numeral (\({{IN}}_{{Type}}\)) which quantifies the navigability in icy waters for these vessel types is calculated:

where \({{\mbox{SIC}}}_{{\mbox{i}}}\) represents the sea ice concentration (in tenths) for ice type i, and \({{\mbox{IM}}}_{({\mbox{Type}},\,{\mbox{i}})}\) is the ice multiplier for the corresponding ship type in ice-covered waters categorized by ice type i. A non-negative IN value indicates that the area is navigable, while a negative IN value indicates unsafe conditions. The total navigable area is derived by summing all regions with non-negative IN within the Arctic Circle (66°34’). The length of the shipping season (in months) is defined as the length of time that IN remains non-negative in a given region each year. Once IN is determined, the corresponding Ship-safe Speed (SS) for Arctic navigation is calculated based on the IN-SS relationship (Supplementary Table 2)91. Then, the Dijkstra shortest path algorithm92 is used to calculate the fastest trans-Arctic route, minimizing the total travel time between St. John’s (47°33′42′′ N, 52°37′54′′ W) in North America or Rotterdam (51°55′ N, 4°30′ E) in Europe, and the Bering Strait (65°38′36′′ N, 169°11′42′′ W). These routes are referred to as the Northwest Passage (NWP) and the Northeast Passage (NEP), respectively. Finally, the transit time is defined as the time required to travel the estimated trans-Arctic route.

Impact of sea ice motion on accessibility

To evaluate the potential influence of sea ice motion on Arctic navigability, we developed the Comprehensive IN (COMIN) framework, which integrates sea ice motion with sea ice concentration and thickness, following Zhao et al. 46. COMIN is formulated by:

Here, \({W}_{{IN}}\), and \({W}_{{SIM}}\) represent the accessibility index weights, set to 0.75 and 0.25, respectively. \({x}_{{IN}}\) is the normalized IN value, ranging from −1 to 1, with the sign of the original values preserved during normalization. \({x}_{{SIM}}\) is the normalized sea ice motion (SIM), ranging from 0 to 1, with slower ice motion ( ≤ 0.15 m/s) corresponding to higher \({x}_{{SIM}}\) values. A grid cell with a non-negative COMIN is considered as navigable.

While COMIN provides a practical approach to assessing Arctic accessibility, it remains an empirical framework that may contain uncertainties, as discussed in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 10.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the differences in shipping season lengths for MMM, Opt_SIC, and Opt_SIT relative to REF-based assessments for both PC6 and OW ships. To quantify these differences, we introduced two metrics, \({R}_{{PD}}\) and \({R}_{{ND}}\), representing the ratios of accumulated areas with positive (\({A}_{{PD}}\)) and negative (\({A}_{{ND}}\)) differences, respectively, relative to the total area (\({A}_{{total}}\)) of the Arctic Ocean north of the Arctic Circle. These metrics are defined by:

To evaluate whether higher-resolution configurations in fully coupled models improve sea ice simulations, we adopted the method described in Min et al.59 and Hou et al.43. Improvements or degradations in higher-resolution configurations relative to lower-resolution configurations from HighResMIP were quantified using:

where \({\mbox{HR}}\) and \({\mbox{LR}}\) denote higher- and lower-resolution configurations, respectively, and \({{{\rm{Ref}}}}\) denotes the reference datasets, which are either PIOMAS sea ice thickness or satellite-observed sea ice concentration. Negative values of \({\mbox{Impv}}\) indicate an improvement (i.e., reduced bias), while positive values denote degradation (i.e., increased bias).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in this study are all freely available and can be accessed via the links below. The CMIP6 historical simulations (see Supplementary Table 3), projections under the SSP5-8.5 scenario (see Supplementary Table 4), and HighResMIP simulations (see Supplementary Table 5) used in this study are available at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/ (last accessed: December 20, 2024). The monthly mean sea ice thickness data from PIOMAS can be downloaded from http://psc.apl.uw.edu/research/projects/arctic-sea-ice-volume-anomaly/data/model_grid (last accessed: December 20, 2024). The sea ice concentration observations provided by EUMETSAT’s OSI SAF are available at https://osi-saf.eumetsat.int/products/osi-450-a (last accessed: December 20, 2024). The sea ice motion vectors data provided by NSIDC are available at https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0116/versions/4 (last accessed: December 29, 2024).

Code availability

The Python3 ‘shortest path algorithm’ of Dijkstra used to estimate trans-Arctic shipping routes is provided by NetworkX (https://networkx.org/documentation/latest/reference/algorithms/shortest_paths.html). The code used to perform the analysis is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Chylek, P. et al. Annual Mean Arctic Amplification 1970–2020: observed and simulated by CMIP6 Climate Models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099371 (2022).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

Kwok, R. Arctic sea ice thickness, volume, and multiyear ice coverage: losses and coupled variability (1958–2018). Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 105005 (2018).

Shokr, M. & Ye, Y. Why Does Arctic Sea ice respond more evidently than antarctic sea ice to climate change?. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2, 0006 (2023).

Stroeve, J. & Notz, D. Changing state of Arctic sea ice across all seasons. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 103001 (2018).

Sumata, H., de Steur, L., Divine, D. V., Granskog, M. A. & Gerland, S. Regime shift in Arctic Ocean sea ice thickness. Nature 615, 443–449 (2023).

Bekkers, E., Francois, J. F. & Rojas-Romagosa, H. Melting ice Caps and the Economic Impact of Opening the Northern Sea Route. Econ. J. 128, 1095–1127 (2018).

Schøyen, H. & Bråthen, S. The Northern Sea Route versus the Suez Canal: cases from bulk shipping. J. Transp. Geogr. 19, 977–983 (2011).

Dawson, J., Pizzolato, L., Howell, S. E. L., Copland, L. & Johnston, M. E. Temporal and spatial patterns of ship traffic in the Canadian Arctic from 1990 to 2015. Arctic 71, 15–26 (2018).

Gunnarsson, B. Recent ship traffic and developing shipping trends on the Northern Sea Route—Policy implications for future arctic shipping. Mar. Policy 124, 104369 (2021).

Müller, M., Knol-Kauffman, M., Jeuring, J. & Palerme, C. Arctic shipping trends during hazardous weather and sea-ice conditions and the Polar Code’s effectiveness. npj Ocean Sustain.2, 12 (2023).

Rodríguez, J. P., Klemm, K., Duarte, C. M. & Eguíluz, V. M. Shipping traffic through the Arctic Ocean: Spatial distribution, seasonal variation, and its dependence on the sea ice extent. iScience 27, 110236 (2024).

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 3−32 (Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2021).

Jahn, A., Holland, M. M. & Kay, J. E. Projections of an ice-free Arctic Ocean. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 164–176 (2024).

Kim, Y.-H., Min, S.-K., Gillett, N. P., Notz, D. & Malinina, E. Observationally-constrained projections of an ice-free Arctic even under a low emission scenario. Nat. Commun. 14, 3139 (2023).

Shen, Z., Zhou, W., Li, J. & Chan, J. C. L. A frequent ice-free Arctic is likely to occur before the mid-21st century. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 103 (2023).

Lebrun, M., Vancoppenolle, M., Madec, G. & Massonnet, F. Arctic sea-ice-free season projected to extend into autumn. Cryosphere 13, 79–96 (2019).

Årthun, M., Onarheim, I. H., Dörr, J. & Eldevik, T. The Seasonal and Regional Transition to an Ice-Free Arctic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090825 (2021).

Crawford, A., Stroeve, J., Smith, A. & Jahn, A. Arctic open-water periods are projected to lengthen dramatically by 2100. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 109 (2021).

Bennett, M. M., Stephenson, S. R., Yang, K., Bravo, M. T. & De Jonghe, B. The opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, geopolitical, environmental, and socioeconomic impacts. Mar. Policy 121, 104178 (2020).

Moe, A. & Stokke, O. S. Asian Countries and Arctic Shipping Policies, Interests and Footprints on Governance. Arct. Rev. Law Polit.10, 24–52 (2019).

Henke, M. T. et al. Evolving Arctic maritime hazards: Declining sea ice and rising waves in the Northwest Passage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2400355121 (2024).

Min, C. et al. The Emerging Arctic Shipping Corridors. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099157 (2022).

Mudryk, L. R. et al. Impact of 1, 2 and 4 °C of global warming on ship navigation in the Canadian Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 673–679 (2021).

Wei, T., Yan, Q., Qi, W., Ding, M. & Wang, C. Projections of Arctic sea ice conditions and shipping routes in the twenty-first century using CMIP6 forcing scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104079 (2020).

Li, X. & Lynch, A. H. New insights into projected Arctic sea road: operational risks, economic values, and policy implications. Clim. Change 176, 30 (2023).

Lynch, A. H., Norchi, C. H. & Li, X. The interaction of ice and law in Arctic marine accessibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2202720119 (2022).

Davy, R. & Outten, S. The Arctic Surface Climate in CMIP6: Status and developments since CMIP5. J. Clim. 33, 8047–8068 (2020).

Notz, D. & Community, S. Arctic Sea Ice in CMIP6. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086749 (2020).

Shu, Q. et al. Assessment of Sea Ice Extent in CMIP6 With Comparison to Observations and CMIP5. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087965 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. The Arctic Sea ice thickness change in CMIP6’s historical simulations. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 2331–2343 (2023).

Watts, M., Maslowski, W., Lee, Y. J., Kinney, J. C. & Osinski, R. A spatial evaluation of Arctic Sea ice and regional limitations in CMIP6 Historical Simulations. J. Clim. 34, 6399–6420 (2021).

Zhang, J. & Rothrock, D. A. Modeling Global sea ice with a thickness and enthalpy distribution model in generalized curvilinear coordinates. Month. Weather Rev. 131, 845–861 (2003).

OSISAF Global Sea Ice Concentration Climate Data Record v3.0 - Multimission. EUMETSAT SAF Ocean Sea Ice. https://doi.org/10.15770/EUM_SAF_OSI_0013 (2022).

Liu, Y., Luo, H., Min, C., Chen, Q. & Yang, Q. Changes in the Arctic traffic occupancy and their connection to sea ice conditions from 2015 to 2020. Remote Sens. 16, 1157 (2024).

Dörr, J. S., Bonan, D. B., Årthun, M., Svendsen, L. & Wills, R. C. J. Forced and internal components of observed Arctic sea-ice changes. Cryosphere 17, 4133–4153 (2023).

Swart, N. C., Fyfe, J. C., Hawkins, E., Kay, J. E. & Jahn, A. Influence of internal variability on Arctic sea-ice trends. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 86–89 (2015).

Cook, A. J., Dawson, J., Howell, S. E. L., Holloway, J. E. & Brady, M. Sea ice choke points reduce the length of the shipping season in the Northwest Passage. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 362 (2024).

Docquier, D. et al. Impact of model resolution on Arctic sea ice and North Atlantic Ocean heat transport. Clim. Dyn. 53, 4989–5017 (2019).

Selivanova, J., Iovino, D. & Cocetta, F. Past and future of the Arctic sea ice in High-Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP) climate models. Cryosphere 18, 2739–2763 (2024).

Schweiger, A. et al. Uncertainty in modeled Arctic sea ice volume. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 116, C00D06 (2011).

Min, C. et al. Toward quantifying the increasing accessibility of the Arctic Northeast passage in the past four decades. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 2378–2390 (2023).

Hou, Y. et al. Evaluation of Antarctic sea ice thickness and volume during 2003–2014 in CMIP6 using Envisat and CryoSat-2 observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 014067 (2024).

Chen, J., Kang, S., You, Q., Zhang, Y. & Du, W. Projected changes in sea ice and the navigability of the Arctic Passages under global warming of 2 °C and 3 °C. Anthropocene 40, 100349 (2022).

Melia, N., Haines, K. & Hawkins, E. Sea ice decline and 21st century trans-Arctic shipping routes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 9720–9728 (2016).

Zhao, P., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Ships are projected to navigate whole year-round along the North Sea route by 2100. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 407 (2024).

Eayrs, C. et al. Advances in Machine Learning Techniques Can Assist Across a Variety of Stages in Sea Ice Applications. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 105, E527–E531 (2024).

Landy, J. C. et al. A year-round satellite sea-ice thickness record from CryoSat-2. Nature 609, 517–522 (2022).

Mioduszewski, J. R., Vavrus, S., Wang, M., Holland, M. & Landrum, L. Past and future interannual variability in Arctic sea ice in coupled climate models. Cryosphere 13, 113–124 (2019).

Sturm, M., Goldstein, M. A., Huntington, H. & Douglas, T. A. Using an option pricing approach to evaluate strategic decisions in a rapidly changing climate: Black–Scholes and climate change. Clim. Change 140, 437–449 (2017).

Jung, T. et al. Advancing polar prediction capabilities on daily to seasonal time scales. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 1631–1647 (2016).

Wayand, N. E., Bitz, C. M. & Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, E. A year-round subseasonal-to-seasonal sea ice prediction portal. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 3298–3307 (2019).

Xiu, Y. et al. The Challenge of Arctic Sea Ice Thickness Prediction by ECMWF on Subseasonal Time Scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097476 (2022).

Zampieri, L., Goessling, H. F. & Jung, T. Bright prospects for Arctic Sea Ice prediction on subseasonal time scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 9731–9738 (2018).

Mu, L. et al. Sea-ice forecasts with an upgraded AWI coupled prediction system. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2022MS003176 (2022).

Kimmritz, M. et al. Impact of ocean and sea ice initialisation on seasonal prediction skill in the Arctic. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 4147–4166 (2019).

Collow, T. W., Wang, W., Kumar, A. & Zhang, J. Improving Arctic sea ice prediction using PIOMAS initial sea ice thickness in a coupled ocean–atmosphere model. Month. Weather Rev. 143, 4618–4630 (2015).

Shu, Q. et al. Arctic sea ice concentration and thickness data assimilation in the FIO-ESM climate forecast system. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 40, 65–75 (2021).

Min, C. et al. Improving Arctic sea-ice thickness estimates with the assimilation of CryoSat-2 summer observations. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2, 0025 (2023).

Song, R., Mu, L., Loza, S. N., Kauker, F. & Chen, X. Assimilating Summer Sea-Ice Thickness Observations Improves Arctic Sea-Ice Forecast. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110405 (2024).

Zhang, Y.-F. et al. Improvements in September Arctic Sea Ice Predictions Via Assimilation of Summer CryoSat-2 Sea Ice Thickness Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105672 (2023).

Song, S. et al. Adapting to a foggy future along trans-Arctic shipping routes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102395 (2023).

Inoue, J. Review of forecast skills for weather and sea ice in supporting Arctic navigation. Polar Sci. 27, 100523 (2021).

Wagner, P. M. et al. Sea-ice information and forecast needs for industry maritime stakeholders. Polar Geogr. 43, 160–187 (2020).

Li, F., Suominen, M. & Kujala, P. Ship performance in ice channels narrower than ship beam: Model test and numerical investigation. Ocean Eng. 240, 109922 (2021).

Wang, K., Zhang, Y., Chen, C., Song, S. & Chen, Y. Impacts of Arctic sea fog on the change of route planning and navigational efficiency in the Northeast Passage during the first two decades of the 21st Century. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 2149 (2023).

Ji, M., Liu, G., He, Y., Li, Y. & Li, T. Analysis of Sea Ice Timing and navigability along the Arctic Northeast Passage from 2000 to 2019. J. Marine Sci. Eng. 9, 728 (2021).

Goldstein, M. A., Lynch, A. H., Li, X. & Norchi, C. H. Sanctions or sea ice: Costs of closing the Northern Sea Route. Financ. Res. Lett. 50, 103257 (2022).

Huntington, H. P. et al. Effects of Arctic commercial shipping on environments and communities: context, governance, priorities. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 118, 103731 (2023).

Ng, A. K. Y., Andrews, J., Babb, D., Lin, Y. & Becker, A. Implications of climate change for shipping: Opening the Arctic seas. WIREs Clim. Change 9, e507 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Trans-Arctic shipping routes expanding faster than the model projections. Glob. Environ. Change 73, 102488 (2022).

Dawson, J., Cook, A., Holloway, J. & Copland, L. Analysis of changing levels of ice strengthening (Ice Class) among vessels operating in the Canadian Arctic over the past 30 years. Arctic 75, 413–430 (2022).

Lee, T. & Kim, H. J. Barriers of voyaging on the Northern Sea Route: A perspective from shipping Companies. Mar. Policy 62, 264–270 (2015).

Liu, M. & Kronbak, J. The potential economic viability of using the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as an alternative route between Asia and Europe. J. Transp. Geogr. 18, 434–444 (2010).

Theocharis, D., Pettit, S., Rodrigues, V. S. & Haider, J. Arctic shipping: A systematic literature review of comparative studies. J. Transp. Geogr. 69, 112–128 (2018).

Drewniak, M., Dalaklis, D., Kitada, M., Ölçer, A. & Ballini, F. Geopolitics of Arctic shipping: the state of icebreakers and future needs. Polar Geogr. 41, 107–125 (2018).

Engtrø, E. A discussion on the implementation of the Polar Code and the STCW Convention’s training requirements for ice navigation in polar waters. J. Transp. Secur.15, 41–67 (2022).

Fedi, L., Faury, O. & Gritsenko, D. The impact of the Polar Code on risk mitigation in Arctic waters: a “toolbox” for underwriters?. Marit. Policy Manag. 45, 478–494 (2018).

Buixadé Farré, A. et al. Commercial Arctic shipping through the Northeast Passage: routes, resources, governance, technology, and infrastructure. Polar Geogr. 37, 298–324 (2014).

Moe, A. A new Russian policy for the Northern sea route? State interests, key stakeholders and economic opportunities in changing times. Polar J. 10, 209–227 (2020).

Kum, S. & Sahin, B. A root cause analysis for Arctic Marine accidents from 1993 to 2011. Saf. Sci. 74, 206–220 (2015).

Makarova, I. et al. Arctic development in connection with the Northern sea route: a review of ecological risks and ways to avoid them. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 1415 (2022).

Cheaitou, A. et al. Impact of CO2 emission taxation and fuel types on Arctic shipping attractiveness. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 112, 103491 (2022).

Chen, J., Kang, S., Wu, A. & Chen, L. Projected emissions and climate impacts of Arctic shipping along the Northern Sea Route. Environ. Pollut. 341, 122848 (2024).

Santos, C. F. et al. Integrating climate change in ocean planning. Nat. Sustain.3, 505–516 (2020).

Santos, C. F. et al. Taking climate-smart governance to the high seas. Science 384, 734–737 (2024).

Tschudi, M., Meier, W. N., Stewart, J. S., Fowler, C. & Maslanik, J. Polar Pathfinder Daily 25 km EASE-Grid Sea Ice Motion Vectors. (NSIDC-0116, Version 4). 10.5067/INAWUWO7QH7B (2019).

Smith, L. C. & Stephenson, S. R. New Trans-Arctic shipping routes navigable by midcentury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, E1191–E1195 (2013).

Stephenson, S. R. & Smith, L. C. Influence of climate model variability on projected Arctic shipping futures. Earth’s. Future 3, 331–343 (2015).

Stephenson, S. R., Smith, L. C. & Agnew, J. A. Divergent long-term trajectories of human access to the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 156–160 (2011).

McCallum, J. Safe Speed in Ice: An Analysis of Transit Speed and Ice Decision Numerals. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Ship Safety Northern (AMNS) Transport Canada. ENFOTEC Technical Services Inc., GeoInfo Solutions Ltd. [Available online at http://www.geoinfosolutions.com/projects/Safeice.pdf.] (1999).

Dijkstra, E. W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math.1, 269–271 (1959).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42406253), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2025A1515011505), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2025T180246 and 2024M751283), the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (Nos. SML2022SP401 and SML2023SP207), the innovative research project of Beijing Globe MetRoute Technology Co., Ltd. (No. CY-2023ZDA01). F.K. was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme through the project Arctic PASSION under grant agreement No. 101003472. We acknowledge the computing resources provided by the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) and the National Supercomputer Center in Guangzhou. We also thank Yijun Yang, Yaqi Hou, and Yafei Nie of the School of Atmospheric Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, for providing information on the CMIP6 and HighResMIP models.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M. and Q.Y. designed the research. C.M. performed research and prepared figures. C.M., Q.Y., H.L., F.K., Q.S., X.W., J.L., and D.C. analyzed data and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kyung-Sook Yun and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Min, C., Yang, Q., Luo, H. et al. Optimizing sea ice parameters mitigates the underestimation of Arctic marine access in CMIP6 climate models. Commun Earth Environ 6, 716 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02705-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02705-3