Abstract

The contributions of climate change and human activities to runoff variation have been examined in multiple individual catchments, but upstream-downstream interaction relationships remain underexplored. Here, we propose a three-tiered attribution framework to investigate the spatiotemporal patterns, underlying drivers, and upstream-downstream relationships of runoff variations in the Yellow River Basin (1952–2021). The results indicate that the longitudinal cumulative effects of climatic (ranging from −8.6% upstream to 7.1% downstream relative to the whole basin) and anthropogenic disturbance (15.2%-92.9%) factors lead to higher risks of runoff variations in downstream regions, with more pronounced seasonal fluctuations (particularly in reservoir-regulated reaches). Glaciers, lakes, and reservoirs’ storage capacities cause lagged effects of climate change and human activities on runoff variations, while simultaneously serving as critical drivers for inter-basin water resource regulation. Integrating comprehensive understanding of multi-scale hydrological variability drivers and spatial interaction mechanisms is essential for advancing adaptive river basin management and sustainable water resources allocation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large rivers, serving as critical conduits connecting upstream and downstream regions within their basins, are essential lifelines for maintaining regional water resources and ecological balance1,2,3,4. They supply more than half of the world’s drinking water5. However, over the past few decades, climate change and human activities have profoundly altered the flow of more than two-thirds of larger river systems, posing serious threats to human livelihoods and the fate of global river corridors6,7,8. With ongoing global warming, rapid population growth, and increasing water demands across regions and sectors, it is anticipated that global river runoff variability will become even more drastic in the coming decades9,10. An increasing number of river networks are expected to experience seasonal cessation of flow, posing greater risks to regional water resources, food security, and ecosystem stability11,12,13. The combined impacts of climate change and human activities on basin-scale hydrological processes and water resources have emerged as a critical challenge for achieving sustainable socioeconomic and eco-environmental development worldwide14.

The variability of river flow is a crucial “indicator” for monitoring the potential impacts of climatic and anthropogenic factors on water resources15. Consequently, numerous studies have decomposed and quantified the relative contributions of climate change and human activities to river runoff variations across different periods based on abrupt streamflow changes16,17,18,19. Among these, the Budyko water-energy balance curve approach20,21,22, with its distinct physical significance, has been widely applied in attribution analysis of runoff variations in basins with precipitation gradients of 35–2,980 mm and drainage areas of 1–6 million square kilometers23,24. Furthermore, scholars have explored the impacts of land-surface modifications, glacial melt, and agricultural irrigation on runoff by analyzing deviations from the Budyko curve in representative catchments25,26,27, combined with the Peter-Clark Momentary Conditional Independence Plus (PCMCI + ) causal discovery algorithm28,29,30. Most of these studies focused on the contribution of regional or overall annual runoff changes in individual unit catchment areas31,32,33,34, and a small number addressed seasonal runoff trends35,36,37. However, none of these studies have compared the relative contributions and driving mechanisms of climate change and human interference to upstream and downstream runoff variations among different catchment areas within a basin.

Recent studies have shown that the river flow distribution across approximately 29% of the global terrestrial surface has significantly shifted from downstream to upstream regions, exacerbating water scarcity in 7.4–16.5% of downstream areas38,39. An increasing trend may lead to greater reliance on upstream “water tower” runoff by nearly half of the world’s downstream areas40. The interdependence of upstream and downstream water resources will complicate regional water resource sustainability management under the influence of climate change and human activities, potentially leading to regional water conflicts38,41. These findings highlight the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of river flow changes and underscore the importance of studying the relationships between upstream and downstream runoff39,42. Therefore, there is an urgent need for in-depth research into the interaction mechanisms and key driving factors of the variation characteristics and spatiotemporal distribution patterns of river runoff between different regions within a basin under the backdrop of climate change and human activities. This will be key to formulating optimal regional or cross-regional water resource management strategies.

Given the observations in recent years of many iconic rivers that were once perennial becoming intermittent43,44, it is imperative to conduct an in-depth attribution analysis of runoff changes in large river basins45, particularly for the Yellow River, the world’s fifth-largest river46. According to statistics, the measured runoff volume in the Yellow River Basin has decreased by more than 40% from 1956 to 201647,48, among which the lower reaches of the Yellow River cumulatively dried up for 1050 days between 1972 and 199849,50. Due to the impact of climate change and human activities, zero flow events frequently occur in the lower reaches of the Yellow River, with longer durations of dryness and the continuously extending interruption sections upstream51,52. The entire basin has become a “disaster area” for runoff changes and water resource shortages under the pressure of climate change and human activities53,54,55. Meanwhile, it is also a typical “demonstration area” for conducting research on the evolution characteristics of large river runoff under the background of climate change and human activities56,57,58. Although numerous studies have evaluated the impact characteristics and contribution rates of climate change and human activities on runoff changes in different catchment areas of the basin at different times59,60,61,62, the interactive relationship and key driving factors between climatic and anthropogenic disturbances and the upstream and downstream runoff changes in the basin are still unclear.

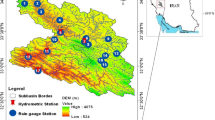

Therefore, this study focuses on the Yellow River Basin and twenty sub-catchments delineated based on the main stem and major tributaries (Fig. 1). Using monthly flow data from hydrological stations along the mainstem and two major tributaries (1952–2021), basin-wide meteorological data, population density and land-use datasets, we employ a constructed three-tiered attribution analysis framework to study the trends, differences, attributions, correlations, and driving factors of upstream and downstream runoff changes within the basin. Specifically, we aim to: (1) analyze the annual and seasonal runoff trend characteristics (1952–2021) across upstream and downstream regions of the Yellow River basin; (2) quantify the relative contributions of climate change and human activities to runoff variations in each sub-catchment; and (3) reveal the interaction mechanisms and key driving factors of runoff variations between upstream and downstream areas within the basin under the impacts of climate change and human activities.

a Spatial locations of hydrological stations, large reservoirs, and sub-catchments. The red triangles mark 20 hydrological stations. Black and white circles mark the position of six major reservoirs. Irregular frame areas are the range of divided sub-catchment areas. Inset highlights the location of the Yellow River basin. b Areas of each sub-catchment.

Results

Trends in annual and monthly mean streamflow

We employ linear regression and multi-year average differentiation analysis (based on change-point-segmented periods; Supplementary Fig. 4) to reveal the spatiotemporal discharge patterns in the Yellow River’s main channel and its two major tributaries (Fen River and Wei River) from 1952 to 2021 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 9). We observe that, except for the upstream H1 hydrological station which exhibits a statistically non-significant increasing trend, discharge at all other monitoring stations shows declining trends. Notably, a significant decreasing trend (P < 0.05) occurs at 13 downstream sites (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, the slopes of the flow at each station along the Yellow River mainstream and Wei River tributary decrease gradually from upstream (H1: 0.45 m³ s–1 yr–1) to downstream (H20: –16.93 m³ s–1 yr–1), with increasing significance. This indicates that the intensity of runoff changes rises from upstream to downstream, and the risk of runoff decline grows progressively.

a The annual variation trend in the deviation values of flow volumes at each hydrological station. Asterisks denote significance levels (* for p ≤ 0.05, ** for p ≤ 0.01, *** for p ≤ 0.001). b The distribution characteristics of the annual average flow volumes at each hydrological station for the years 1952–2021, as well as the multi-year average variation trends during different periods. c The monthly and annual variation amounts of the multi-year average flow volumes at each hydrological station during different periods.

Along the Yellow River’s main channel, the multi-year average flow first increases (H5) and then decreases (H9) from the source (H1) to the middle reaches. Further downstream, it shows another increase (H19) followed by decrease (H20), with flow distribution becoming more dispersed (Fig. 2b). For the latter 35 years (PII: 1987–2021), all sites show decreased multi-year average flow compared to the initial 35 years (PI: 1952–1986), with reductions of 24.62–733.05 m³ s–1. Notably, when subdivided into four periods, Period 4 (P4: 2004–2021) shows increased discharge at all sites compared to Period 3 (P3: 1987–2003) (Supplementary Fig. 9), revealing finer-scale flow variations than the two-period division. Additionally, the flow reduction (or increase) in the change period compared to the reference period is mostly concentrated in summer (June-August) and autumn (September-November). In contrast, spring (March-May) and winter (December-February) exhibit opposite trends, particularly at middle and upper reach stations (Fig. 2c). Here, the magnitude of reduction in multi-year average flow at downstream sites during different periods is substantially higher than at upstream sites, indicating higher vulnerability of downstream areas to runoff variability. These localized spatiotemporal differences in upstream-downstream runoff trends carry substantial implications for both basin-wide and local water resource management, though often overlooked in large-scale analyses.

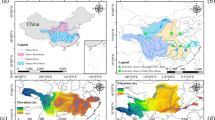

Trends and spatial differences of climatic changes

We investigate the climate change trends and spatial distribution differences in the Yellow River Basin over 1952–2021 using nearly 70 years of annual and monthly data on air temperature, precipitation, and potential evapotranspiration, which substantially impact water balance (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 10–13). The regional distribution of air temperature (Fig. 3a) and potential evapotranspiration (Fig. 3c) across the basin shows a general west-to-east increasing gradient, while precipitation displays a southeast-to-northwest decreasing trend (Fig. 3b). The 70-year average air temperatures (−2.86 to 13.85 °C) and potential evapotranspiration (652.76–1170.23 mm) across various sub-catchments show consistent upward trends from the upstream S1 to the downstream S20 (Supplementary Fig. 10a and c). Precipitation shows an initial fluctuating decrease from the headwater S1 (545.16 mm) to S8 (195.31 mm), followed by an overall fluctuating increase towards the downstream S20 (677.57 mm) (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The high evapotranspiration and low precipitation in northwest areas (S6–S9) contribute substantially to runoff reduction between H5 and H9 hydrological stations.

a–c Spatial distribution of annual means of air temperature, precipitation, and potential evapotranspiration (1952–2021), alongside their annual variation trends of each sub-catchment. The inset illustrates the similarities and differences in interannual variability of these climate factors across sub-catchments. d–f Annual trends (1952–2021) of these climatic factors in the whole basin, along with their multi-year mean shifts during distinct periods. g–i The annual variation trends (1952–2021) of the deviation values of air temperature, precipitation, and potential evapotranspiration in each sub-catchment; and the corresponding variation trends of the multi-year average values across different periods. j–l The variations in monthly and annual average values of these climatic factors between different periods for the whole basin and each sub-catchment area.

Trend analysis shows statistically significant annual mean air temperature increases (P < 0.01), throughout the basin and sub-catchments (0.008–0.035 °C yr–1) (Fig. 3d, g and Supplementary Fig. 11). This warming trend remains particularly pronounced since 1986, with spring and winter increases exceeding those in summer and autumn (Fig. 3j). The annual mean potential evapotranspiration shows an increasing trend throughout the basin (Fig. 3f) and other sub-catchments (0.013–0.695 mm yr–1), with significant trends noted in the central S8–S13 watersheds (P < 0.05; Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 13). Only the headwater S1 and downstream S20 exhibit decreasing trends. From Period 1 to 4, multi-year average potential evapotranspiration across the basin and sub-catchments shows an initial decrease followed by an increase. These reductions predominantly occur in summer and autumn months, while increases are more pronounced in spring and winter (Fig. 3l).

The annual mean precipitation (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Fig. 12) in the upstream S1–S5 and S8–S9 sub-catchments exhibits increasing trends (0.06–1.19 mm yr–1), with significant trends observed in the S1–S3 and S5 sub-catchments (P < 0.05). The whole basin (Fig. 3e) and other sub-catchments show non-significant decreases (ranging from –0.715 to –0.027 mm yr–1). From Period 1 to Period 3, except for a slight increase in the multi-year average precipitation at the headwater S1, the entire basin and other sub-catchments experience a decrease, particularly downstream. From Period 3 to Period 4, multi-year average precipitation increases basin-wide, with particularly strong gains in upstream S1–S5 and downstream S20 (42.33–61.89 mm). Moderate increases occur in midstream S11–S19 (26.87–42.6 mm), while upstream S6–S10 show minimal changes (2.76–13.63 mm). Changes in the multi-year average precipitation are primarily concentrated in the summer and autumn months, while spring and winter trends are opposite (Fig. 3k). Moreover, the trend of annual average precipitation in each sub-catchment during different periods is basically consistent with the corresponding station runoff trends. This indicates that precipitation is the dominant climatic factor affecting runoff changes.

Spatiotemporal variation characteristics of human activities

We characterize the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of human activities in the Yellow River Basin through population density and the transfer and change volumes of various land use types (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 14–16). The entire basin is dominated by grassland and arable land (74.47%), followed by forest land and unused land (21.38%), and finally by construction land and water area (4.15%) (Fig. 4b). Population density, along with the proportions of arable land and construction land use types, gradually increases from upstream to downstream. This spatial pattern reflects that human activity intensity is highest in downstream areas. As a result, these regions require greater domestic water, agricultural irrigation water, and socio-economic water demands per unit area compared to upstream counterparts.

a The population density distribution and changes for the years 1964, 1982, 2000, and 2010. b The proportions of the average areas of different land use types in each watershed for the periods around 1980, 1990, 2005, and 2015. c The total land use changes that occurred in each sub-catchment during the periods 1980–1990, 1990–2005, and 2005–2015. The transfer volumes of each land use type in the whole basin during the periods 1980–1990 (d), 1990–2005 (f), and 2005–2015 (h). The proportions of different land use type changes to the total change in each sub-catchment during the periods 1980–1990 (e), 1990–2005 (g), and 2005–2015 (i).

During 1980–1990 (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 14), the basin shows a 70.43% arable land expansion alongside 57.2% water area reduction and 11.55% forest loss. Within the water category, reservoirs and ponds increase by 7.34% (Fig. 4e). Additionally, permanent glacier melt and forest loss are concentrated in the upstream S1 and S5, whereas reservoir expansion (71.29%) predominantly occurs in S2 (Fig. 4e). These patterns indicate that dominant human activities during this period include agricultural production, domestic water use, and reservoir construction.

Between 1990–2005 (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 15) and 2005–2015 (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 16), the “Grain for Green” project and social development lead to substantial changes in land use across the basin. Construction land area increases by 42.9% and 87.11%, respectively, while forest cover expands by 36.47% and 6.80%. Conversely, arable land area decreases by 34.79% and 42.2%, and grassland area declines by 54.59% and 27.81%, respectively. Although the total water area remains relatively stable, reservoirs and ponds increase by 7.91% and 4.94% (Fig. 4g, i). Notably, from 1990 to 2005, the expansion of reservoirs and ponds in the S2 and S18 regions accounts for 42.11% and 106.1%, respectively. Construction land area grows in all sub-catchments (23.08–100%), while approximately 75% of sub-catchments experience a reduction in arable land. This trend reflects declining agricultural water use but growing social development demands. Furthermore, recent decades show a shift in water storage from natural systems (e.g., lakes, wetlands, and glaciers) to artificial ones (e.g., reservoirs and ponds), accompanied by a marked reduction in water storage capacity.

Connection of inter-regional water resources contribution and runoff variation

By quantifying the contribution of each sub-catchment to the runoff variation (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 17), we find that the upstream S1–S5 and midstream S10–S19 positively contribute to the main river runoff. This suggests these sub-catchments have relatively abundant water resources, enabling them to meet local demands while providing additional water resources for downstream areas. Conversely, upstream S6–S9 and downstream S20 show negative contributions (Figs. 5a, b), indicating water scarcity in these regions, requiring supplementary water sources from upstream or external inputs. Additionally, due to the operation of large reservoirs, the impact of the upstream S2–S3 and midstream S17–S18 sub-catchments on river runoff exhibits fluctuations between positive and negative contributions (Fig. 5c). Trend analysis reveals increasing runoff contributions in only three sub-catchments (S1, S5, S18). By contrast, the entire basin and majority of sub-catchments show significant declines (P < 0.05). The rate of decline in annual runoff contribution is more pronounced in downstream areas. These findings indicate that the overall contribution of the basin and its sub-catchments to the main river runoff is diminishing, particularly in downstream regions.

a The annual variation trend of runoff contribution volumes in each sub-catchment, as well as the multi-year average variation trends during different periods. b The distribution characteristics of the annual average runoff contribution volumes at each sub-catchment for the years 1952–2021, with an inset illustrating changes in the distribution characteristics of the annual average runoff contributions over different periods. c The monthly and annual variation amounts of the multi-year average runoff contribution volumes in each sub-catchment during different periods.

Contributions of climate change and human activities to runoff variation

The impacts of climate change and human activities on annual and monthly runoff contributions vary spatially across sub-catchments and temporally across periods (Fig. 6). From Period I to Period II, the multi-year average runoff reduction along the Yellow River’s mainstem hydrological stations increases from upstream H1 (47.92 m3 s–1) to downstream H20 (733.05 m3 s–1). Notably, 90% of sub-catchments (except S5 and S18) exhibiting negative contributions (Fig. 6a). Additionally, the percentage of climate change’s contribution to runoff reduction at each hydrological station, compared to the total reduction (i.e., the runoff reduction at the H20 station), ranges from –8.6 to 7.1%. In contrast, the impact of human activities ranges from 15.2 to 92.9%. These results indicate that anthropogenic interference dominates the changes in the Yellow River’s runoff. Notably, the increased precipitation in headwater catchments reduces the impact of climate change on runoff decline across the entire watershed.

The multi-year average annual scale runoff contribution volume changes (bubble chart) for upstream and downstream sub-catchments from period I to period II (a), period 1 to period 2 (b), period 2 to period 3 (c), and period 3 to period 4 (d), the percentage contributions (%) of climate change and human activities to the changes in runoff contribution volumes (bar chart and scatter plot), and the flow volume changes at the corresponding hydrological stations at the outlets of each sub-catchment (center points of bubbles). The multi-year average monthly scale runoff contribution volume changes (shape and size of points) for upstream and downstream sub-catchments from period I to period II (e), period 1 to period 2 (f), period 2 to period 3 (g), and period 3 to period 4 (h), and the proportion of the contribution of climate change to the total changes in runoff contribution volume (color of points).

When divided into four sub-periods, from Period 1 to Period 2 and then to Period 3, the runoff contribution for the entire basin decreases by 538.19 m3 s–1 and 586.35 m3 s–1. Climate change and human disturbances account for 18.9% versus 81.1% of the first decrease, and 30% versus 70% of the second decrease, respectively. Notably, 80% of the sub-catchments experience reductions (Figs. 6b, c). From Period 3 to Period 4, the runoff contribution for the entire basin increases by 252.94 m3 s–1, but 50% of sub-catchments show a decrease in runoff contribution (Fig. 6d). Climate change and human disturbances account for 138.7% and –38.7%, respectively. This indicates that the overall increase in runoff contribution results solely from climate change.

Monthly analysis (Figs. 6e–h) reveals that runoff contribution changes during the change period are generally more pronounced in summer and autumn than in spring and winter for most sub-catchments. Additionally, climate change predominantly drives runoff contribution variations during summer and autumn across most sub-catchments. In contrast, spring and winter changes are largely governed by human disturbances. However, sub-catchments regulated by large reservoirs exhibit pronounced monthly variations (Fig. 6b), which are predominantly driven by human regulation.

Dominant drivers of changes in runoff

Based on the characteristics of climate change and human activities in different sub-catchments across various periods, we employ correlation analysis and PCMCI+ causal network analysis to identify the key driving factors behind river runoff changes within the basin. The correlation analysis reveals that the catchment’s runoff contribution exhibits a highly significant positive correlation with precipitation (P < 0.001). In contrast, human disturbances’ contribution to runoff shows a significant negative correlation with cultivated land area, construction land area, and reservoir/pond area (Fig. 7). Additionally, the area of permanent glaciers and snow cover is significantly negatively correlated with temperature and potential evapotranspiration, while being significantly positively correlated with runoff contribution. The correlation analysis indicates that precipitation, glacier melt, agricultural production, reservoir construction, and socio-economic development are strongly associated with runoff changes in the Yellow River Basin.

We further employ the PCMCI+ algorithm to assess the strength of causal relationships between runoff contribution in each sub-catchment and the main components of the Budyko water-energy balance (precipitation and potential evapotranspiration), as shown in Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 18. The MCI test results demonstrate that sub-catchments at the headwaters of the mainstem (S1) or major tributaries (S5, S13–S15, and S19) display the strongest positive connections (highest MCI values: ranging from 0.46 to 0.77) between runoff contribution and precipitation. These same sub-catchments simultaneously show the strongest negative relationships (lowest MCI values: ranging from –0.49 to –0.19) with potential evapotranspiration. This indicates that precipitation and potential evapotranspiration are the dominant factors influencing runoff contribution in these sub-catchments. In contrast, in water-scarce regions with intensive human activities (S6–S12 and S20) and large reservoir-controlled areas (S2–S4 and S17–S18), the MCI values between runoff contribution and concurrent precipitation are either small or non-existent at the 0.05 significance level. Moreover, during Period II (1952–1986), when anthropogenic disturbances are stronger (Fig. 8b), the MCI values between runoff contribution and precipitation in the sub-catchments are lower than those in Period I (1987–2021) (Fig. 8c). This suggests that the influence of precipitation on runoff contribution in these catchments diminishes under human impacts, making anthropogenic interference a key driver of runoff changes. Additionally, strong causal links exist between runoff at upstream and downstream hydrological stations, with all MCI values being positive and relatively large (Figs. 8d–f). This indicates mutual influences on runoff variations between upstream sub-catchments and downstream regions.

Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) respectively present the MCI causal association strength between runoff contributions of each sub-catchment and contemporaneous precipitation/potential evapotranspiration during (a) 1952–2021, (b) 1952–1986, and (c) 1987–2021, with missing values indicating non-significant causal association at the 0.05 significance level; Subfigures (d), (e) and (f) show the MCI causal association strength between contemporaneous streamflows of upstream and downstream hydrological stations for the same three periods, respectively.

Ultimately, by integrating the relationships between runoff change contributions in each sub-catchment and climate change/human activities (Supplementary Tables 2–5), we identify distinct patterns. For the less disturbed headwater sub-catchment S1, the observed increase in runoff is primarily driven by ice and snow melt. However, subsequent reductions in glacial meltwater, coupled with intensified human activities, lead to a marked decrease in runoff during the change period compared to the reference period. In the middle and lower reaches experiencing stronger human interferences, reservoir storage emerges as the primary driver of runoff reduction in sub-catchments S2–S4 and S17–S18. Furthermore, reservoir operations in these areas induce pronounced seasonal flow fluctuations. Additionally, the “Grain for Green” project reduces agricultural irrigation water use in most sub-catchments. However, these water savings are offset by increasing socio-economic demands, resulting in minimal net gains or even negative changes in runoff contributions. In summary, the analysis demonstrates that runoff changes across the Yellow River Basin result from the combined effects of multiple factors. Key drivers include precipitation variability, declining glacial meltwater, reservoir construction, agricultural production, and socio-economic development.

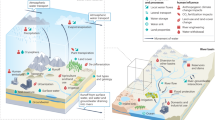

Upstream-downstream interaction mechanism of runoff changes

Figure 9 illustrates the upstream-downstream interactions in runoff changes of major rivers under the influence of climate change and human activities. The causal relationship analysis between runoff at upstream and downstream hydrological stations further confirms mutual influences in runoff variations between upstream and downstream catchments. Moreover, the causal linkages between adjacent stations are stronger, while the strength of upstream-downstream causal relationships gradually weakens with increasing distance between stations (Figs. 8d–f). Intuitively, the changes in downstream river flow are the cumulative sum of contributions from all upstream sub-catchments, potentially even reflecting the combined effects of climatic changes and human activities within each of these upper basins (Fig. 6). This indicates that climate change and human activities in the upper catchment exert an influence on the variation of river runoff downstream, encompassing all reaches below the catchment point. Notably, the cumulative effect means that when both climate change and human activities in these upper sub-catchments contribute uniformly (positive or negative), downstream areas may face a higher risk of runoff fluctuations.

a The impacts and contribution characteristics of climatic changes and human activities on runoff variations in the upstream and downstream watersheds are described separately, along with the interactive relationship of water resource regulation between the upstream and downstream sub-catchments. b The human activities within the upstream and downstream sub-catchments of the basin and their contribution characteristics to river runoff variations are highlighted. Overall, the demand for water resources from human activities in each sub-catchment from the upstream to the downstream within the basin gradually increases. The combined effects of climate change and human activities along the way result in higher risks of runoff variation in the downstream areas. At the same time, the demand for water resources by human societies in the downstream regions will promote the regulation of water resources between the upstream and downstream sub-catchments within the basin, thereby affecting the runoff variations in both the upstream and downstream areas.

Additionally, we find that the causal strength of runoff volumes among hydrological stations during the change period (Fig. 8f) changes substantially compared to the reference period (Fig. 8e). Notably, the causal linkage strength between runoff at the downstream H20 station and upstream stations (from H5 to H7 in water-scarce regions) becomes even higher than that between closer stations (from H9 to H12). This suggests that water resource demands caused by human activities in downstream areas can influence runoff contributions from upstream sub-basins, thereby affecting runoff variations in upstream regions. This bottom-up feedback of human water demand specifically manifests as upstream sub-catchment areas (including even the water-scarce S5–S12 regions) increasing their contribution to runoff through human activities such as reducing local water usage (e.g., “Grain for Green”) or enhancing local water supply (e.g., reducing surface areas of lakes, reservoirs, or glaciers). These measures collectively support downstream water resource needs for social development (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 9). Evidently, human water demand and the catchment’s water storage capacity (reflected in underlying surface characteristics and water surface area changes, etc.) emerge as key drivers in realizing the process of upstream-downstream interaction. Notably, changes in basin water storage result from climatic changes and human activities in the preceding period and influence the runoff changes in the current or future periods. Furthermore, causal relationships between the runoff contribution quantities of the sub-watersheds and precipitation in lagged months exist at the 0.05 significance level. Some lagged-month causal linkage strengths (MCI) even exceed those of concurrent-month precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 18). This indicates that the impacts of climate change and human activities on runoff variation exhibit a lagged effect due to the water storage function of the catchment36, such as the reduction in permanent glacier area affecting runoff variations.

Discussion

Trend analysis reveals that the reduction in runoff within the Yellow River Basin gradually intensifies from upstream to downstream over the past 70 years (1952–2021), with pronounced seasonal variations37 in flow at different hydrological stations (Fig. 2). Consequently, we develop a three-tiered framework for attribution analysis of runoff changes to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and key driving factors behind the spatiotemporal differences in upstream and downstream runoff variations. Our findings indicate that precipitation, reservoir construction, glacier and snowmelt, agricultural production, and socioeconomic development correlate strongly with changes in runoff contribution from upstream and downstream sub-catchments (Fig. 7). Moreover, human activities have gradually dominated the impact on runoff, altering the causal relationship between precipitation and runoff (Fig. 8a–c)33,38,63,64. The reduction in precipitation decreases the water resource allocation in the catchment area22,30, while the intensification of anthropogenic disturbances and evapotranspiration exacerbates water loss35,65. These factors collectively reduce the runoff generation capacity of the catchment, leading to decreased streamflow at hydrological stations49. The impacts are particularly pronounced in downstream regions, where both climate change and human activities exert stronger influences38,39,40. As is well known, sufficient water resources remain an important factor supporting societal development, which also explains why downstream regions with wider catchment areas develop faster economically and socially than upstream regions38. However, with the enhancement of climate change and human activities throughout the entire basin, the runoff contribution from each sub-watershed decreases. The cumulative effects of these drivers along the upstream and downstream catchments amplify runoff variation risks in downstream river reaches, directly impacting the socio-economic development of these areas66,67. Therefore, over the past decade or so, the basin has implemented a series of proactive measures14, such as the “Grain for Green” policy55,68, to mitigate the negative impacts of water scarcity. However, the effectiveness remains limited under the combined influence of climate change and rapid socio-economic development69.

Through the PCMCI+ causal analysis algorithm, we discover that a substantial mutual causal relationship exists between upstream and downstream river runoff (Fig. 8d–f). Water-rich upstream catchments supply essential water resources to downstream water-scarce regions. This dependence has intensified with recent rapid downstream development, increasing both demand and reliance on upstream sources38,39. The impacts of climate change and human activities on runoff water resources in each sub-catchment accumulate and transmit through river connections, thereby leading to changes in downstream runoff70. Simultaneously, downstream areas can also feedback their water resource demands to upstream areas43. In response, the upstream areas can influence the variation in river runoff from downstream to upstream by altering human activities or utilizing reserved water resources (reduction in water body area). Although we do not quantitatively separate the contributions of catchment storage variable changes to runoff, the variations in water body area, such as glaciers, lakes, and reservoirs, indicate that storage variables play a key role in runoff changes21. Additionally, the water storage function of the watershed (change in water surface area) leads to a lag effect in the impact of climate change and human activities on runoff variation36. Therefore, expanding regional water storage (reservoir construction) and strengthening water resource management can address the increasingly severe extreme climate events and the uneven spatial and temporal distribution of water resources14. In summary, our study emphasizes the causal relationship between climate change/human activities and runoff variation, as well as the interconnected nature of runoff changes and water scarcity between upstream and downstream regions (Fig. 9). This may help provide references for promoting cross-regional water resource regulation and mitigating the occurrence of water resource conflict events71.

The three-tiered runoff change attribution analysis framework we construct compares the evolutionary characteristics of climate change and human activities across different spatial scales (entire basin vs. sub-basins), temporal scopes (two vs. four change periods), and temporal resolutions (annual vs. monthly) alongside their impacts on runoff variation. This multi-dimensional analysis reveals more hidden information about runoff variation drivers35. For instance, in the source region S1, climate warming during the reference period leads to glacier melt, thereby increasing early runoff; however, as meltwater diminishes, streamflow declines substantially despite increased precipitation during the change period5,72. The primary anthropogenic factors influencing runoff in sub-catchments S2–S4 and S17–S18 are reservoir construction and operation, while the remaining mid-lower sub-catchments are mainly associated with agricultural activities and socio-economic development. From 2004 to 2021 (P4), increased precipitation in nearly all sub-basins partially relieves basin-wide water scarcity pressures. However, 50% of sub-catchments still show negative runoff contributions relative to the reference period (P3), reflecting heightened human influence on runoff (Fig. 6). Notably, the severely water-stressed sub-catchment S20 experiences positive human-induced impacts on runoff changes during this period, likely due to arable land shifts and the influence of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project73. Additionally, marked seasonal differences in the impact of climate change and human activities on river runoff exist, particularly in reservoir-regulated sections26,38. These conclusions hold considerable theoretical and practical importance for formulating adaptive strategies to climate change and evaluating the effectiveness of water resource management policies.

Notably, our research assumes that water resources are transported between sub-basins solely through the main river channel73. Thus, the interactions between sub-basins may be more complex and interconnected. Additionally, the catchment range of each region does not remain fixed over the past 70 years1. The attribution decomposition method for runoff variation neither accounts for the differences in surface characteristics across distinct sub-watersheds nor considers the intricate effects of upstream inflow reception and utilization on the actual evapotranspiration in mid-lower sub-basin regions17,19,22,25,30. To clarify the interactions between sub-catchments, we unify the variation periods of meteorological and hydrological time series data74. These factors increase the uncertainty in decomposing the contributions of climate change and human activities, but do not affect the key conclusions in this study. Furthermore, due to the lack of continuous data on population density, land use, and groundwater resource changes at the third level of attribution analysis, our study does not accurately quantify the contributions of different types of human activities to runoff changes.

In the foreseeable future, the impacts of climate change and human activities on river runoff variations will become more severe14,39,72. The importance of water resources for human survival and development increases daily, and the inter-regional connections of water resources between upstream and downstream regions, even across large basins, will become tighter38. The allocation and scheduling of water resources must place greater emphasis on regional interactions and refine the contributions of specific human disturbance factors to runoff changes as much as possible. Furthermore, future research should enhance analyses of correlations between land use remote sensing data and various human activity types. Specifically, studies need to quantify how changes in arable land, construction land, and reservoir areas relate to human water use intensity. Building upon our three-level runoff attribution framework, we will quantify how specific land-use types and human disturbance factors contribute to river channel runoff changes. These findings will directly inform government water resource management optimization strategies. Given the widespread availability of global meteorological, hydrological, and land-use datasets, the runoff change attribution approach employed in this study holds broad applicability across other river basins worldwide.

Methods

Study area

The Yellow River, located in northern China (31.5°-41.9° N, 94.6°-119.8° E), is one of the longest rivers in the world (Fig. 1). The main course of the Yellow River spans 5464 km, originating from the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau. It flows through the Inner Mongolia Plateau, the Loess Plateau, and the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, traversing nine provinces from west to east across China. Ultimately, it empties into the Bohai Sea through the Lijin hydrological station, which covers a catchment area of 751,869 km². The terrain of the Yellow River Basin is characterized by higher elevations in the west and lower in the east. The climate conditions within the basin exhibit marked regional variations: the northwestern part experiences an arid alpine climate, the central region has a semi-arid temperate continental climate, and the southeastern part features a semi-humid temperate monsoon climate. Within the basin, numerous water conservancy projects have been constructed, with a total reservoir capacity reaching 90 billion cubic meters, accounting for over 150% of the annual average flow volume62. Additionally, large-scale agricultural irrigation projects are distributed along the main course of the Yellow River and its two major tributaries, the Fen River and the Wei River. The arable land area accounts for 28.84% of the basin’s total area, making it a major grain-producing region in China58,75. The Yellow River provides essential water resources for 12% of the national population and supports 15% of the irrigated areas59. However, its average flow is only about 5% of that of the Yangtze River and 0.8% of the Amazon River, with approximately 60% of the river’s runoff originating from the upstream regions76.

Data sources and processing

This study utilizes monthly average air temperature77, precipitation78, and potential evapotranspiration79 data at a 1 km resolution from 1952 to 2021, as well as land use data80 at the same resolution for the years 1980, 1990, 2005, and 2015. These datasets originate from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home). The monthly average temperature and precipitation datasets are generated using the Delta spatial downscaling scheme based on the global 0.5° climate dataset released by CRU and the high-resolution global climate dataset published by WorldClim, and are validated using data from 496 independent meteorological observation points within China81. The monthly potential evapotranspiration dataset is calculated using the Hargreaves potential evapotranspiration formula. The land use datasets derive from Landsat TM/ETM remote sensing images through manual visual interpretation, offering high precision and have been widely used in remote sensing monitoring of land use in China. In this study, the land use types have been reclassified (Supplementary Table 1). The GIS population distribution dataset for the six national censuses in China is acquired from the Scientific Data Bank website (https://www.scidb.cn/en)82. Additionally, we obtain monthly runoff data (1952–2021) for 20 hydrological stations from the Hydrology Bureau of the Yellow River Conservancy Commission (http://www.yrcc.gov.cn/) and its published “Yellow River Hydrology Yearbook”. These stations comprise 17 along the Yellow River main channel, 2 on the Weihe River, and 1 on the Fenhe River.

Based on the geographical location information of hydrological stations (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2), and combined with the ASTER GDEM V3 digital elevation model (DEM) dataset at a 30 m resolution downloaded from the Geospatial Data Cloud website of the Computer Network Information Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.gscloud.cn), we utilize the hydrological analysis methods in ArcGIS 10.3 software (Supplementary Fig. 2) to divide the watershed areas along the main Yellow River and its two tributaries into twenty sub-catchments (Fig. 1). Subsequently, data processing tools are employed to extract and calculate the meteorological, land use, and population data (Eq. 1) for each sub-watershed during different periods.

where \({P}_{{Sub}}\) and \({P}_{i}\) are the population density of the sub-catchment and the counties intersecting with the sub-catchment (people km-2), respectively. \({S}_{{Sub}}\) and \({\Delta S}_{i}\) are the area of the sub-catchment and the counties intersecting with the sub-catchment (km2), respectively. \(n\) is the number of counties intersecting with the sub-catchment.

A three-tiered framework for attribution analysis of runoff change

Supplementary Fig. 3 presents the overall framework of the research process and the three-tiered attribution analysis method for streamflow variation. The whole idea of this framework is to progressively attribute the variation of basin runoff to upstream and downstream sub-catchment areas, climate change, and human activities in each sub-catchment area, as well as the main climatic and human activities factors. On this basis, through spatiotemporal difference comparative analysis, the interaction relationships among upstream and downstream sub-catchment areas causing river channel runoff changes under the background of climate change and human activities are clarified, along with their key driving factors (please refer to the relevant sections below for details).

Change point detection and trend analysis

To accurately analyze and quantify the variation patterns of climatic variables and river discharge, we initially employ five widely-used hydro-meteorological change point detection methods17,19,62,74 to identify the notable change points in climatic factors and hydrological station flows within each sub-catchment (Supplementary Methods). Since this study focuses on the impact of climatic variables on runoff and the interaction between upstream and downstream runoff changes, we uniformly select the most frequently occurring change point across the upstream and downstream runoff sequences to divide each watershed into a reference period (Period I: 1952–1986) and a change period (Period II: 1987–2021) (Supplementary Fig. 4). To minimize regional discrepancies in change points, we further conduct change point detection on the runoff data from each hydrological station during these two periods (Supplementary Fig. 5), resulting in four sub-periods: Period 1 (1952–1969), Period 2 (1970–1986); Period 3 (1987–2003), and Period 4 (2004–2021). Subsequently, we calculate the multi-year averages for each period to quantify the characteristics of variation in multi-year monthly/annual average meteorological and hydrological data within each sub-catchment before and after the change points.

Furthermore, we combine linear regression analysis with the least squares method83 to further investigate the temporal trends in annual average values of various meteorological and hydrological elements from 1952 to 2021. A trend is considered statistically significant if the slope of the fitting line is significantly different from zero (t-test: P < 0.05). Finally, we use hierarchical clustering analysis to explore the spatial distribution characteristics of climate change among different watersheds.

Quantify the contribution of each sub-catchment to runoff change

We quantify the contribution of each region to the overall flow of the Yellow River Basin by calculating the runoff contribution from each sub-catchment \({Q}_{{Sub}}\) (Eq. 2). In this study, we assume that the main channel connecting upstream and downstream watersheds is predominantly through the main river. If large-scale cross-regional water transfers or additional water resource connections are established during our study period, substantial changes in the runoff contributions of the watersheds would occur, which could be identified through data analysis. Small-scale water transfers would have minimal impact on the results of this study and can be disregarded.

where \({Q}_{{Sub}}\) is the runoff contribution of the sub-catchment. \({Q}_{{outlet}}\) and \({Q}_{{inlet}}\) are the discharge at the outlet and inlet of the control section of the sub-catchment, which are equivalent to the flow measured at the downstream and upstream hydrological station, respectively. When \({Q}_{{Sub}}\ge 0\), it indicates that the water resources in the watershed are self-sufficient and can provide water resources to downstream areas or other catchments. When \({Q}_{{Sub}} < 0\), it indicates a shortage of water resources in the watershed, where local sources cannot meet the water demands, requiring supplementation from upstream sources. The larger the positive or negative difference in runoff contributions between upstream and downstream watersheds, the greater the dependency of downstream areas on upstream water resources, which indicates a more interconnected interaction between different catchments.

Decompose the contributions of climate change and human activities

Budyko demonstrates that the evaporation ratio (\({AE}/P\)) of a basin is primarily governed by the ratio of potential evapotranspiration (\({PET}\)) to precipitation (\(P\)), which is denoted as the aridity index (\(\varphi ={PET}/P\)). He further proposes corresponding water-energy balance curve equations for basins84. However, other factors, such as vegetation, soil water storage, and rainfall seasonality, affect precipitation partitioning, resulting in scattered observations around the Budyko curve28,30. Consequently, researchers have proposed various forms of water-energy balance equations tailored to different watershed characteristics17,19,20. Furthermore, deviations between specific catchments and the Budyko curve have been used to evaluate the impact of basin attributes28,29. The broad applicability of Budyko water-energy balance framework has been extensively validated19,42. Building on this, we employ the detection of change points combined with the water-energy coupling equation to quantitatively assess the contribution of climate change and human activities to runoff variation in each sub-catchment. Given the substantial anthropogenic influences and regional heterogeneity among sub-catchments, changes in evapotranspiration due to altered basin properties may be closely linked to human activities42,53. We therefore apply four non-parametric Budyko curves (Eq.( 3)) to compare upstream and downstream sub-catchments84,85,86,87. These non-parametric curves exhibit strong robustness in eliminating uncertainties associated with parameterization and capturing complex hydrological responses across heterogeneous watersheds28,29.

where \({{AE}}^{{\prime} }/P\) is the theoretical evapotranspiration ratio on the Budyko curve corresponding to the aridity index. \(\varphi\) is the simple drought index, i.e., (\({PET}/P\)).

In this study, we employ a decomposition method to separate the impacts of climate change and human activities on runoff variation17,30,45, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6a. In this study, the impact of human activities on runoff excludes indirect effects induced by anthropogenic climate change45. Specifically, we hypothesize that combined human activities and climate change shift the relationship between aridity index and evaporation ratio in the catchment from Point A (\({{PET}}_{1}/{P}_{1}\), \({{AE}}_{1}/{P}_{1}\)) in the reference period to Point B (\({{PET}}_{2}/{P}_{2}\), \({{AE}}_{2}/{P}_{2}\)) in the changed period. Under the sole influence of climate change, the aridity index-evaporation ratio relationship would follow the Budyko curve, transitioning from Point A to Point C (\({{PET}}_{2}/{P}_{2}\), \({{AE}}_{2}^{{\prime} }/{P}_{2}\)), which shares the same aridity index as Point B. Direct human activities then drive the relationship from Point C to Point B. This reveals that climate change affects both horizontal and vertical components of runoff variation in the catchment, while direct human activities only induce vertical changes in runoff30,45. Under long-term average conditions, where soil water storage variations are negligible17, runoff can be expressed as a function of precipitation and the evaporation ratio:

Consequently, the contribution of human activities to runoff variation can be calculated as follows:

For a given region, differences in multi-year average streamflow (\({\Delta Q}_{{Sub}}\)) between the change period (\({Q}_{2}\)) and reference period (\({Q}_{1}\)) at hydrological stations result from the combined effects of climate change (\({\Delta Q}_{c}\)) and human activities (\({\Delta Q}_{h}\)):

Consequently, the impacts of climate change on runoff variation can be expressed as follows:

However, the focus of this study is to analyze the changes in runoff during the change period compared to the reference period, where the catchment area in the reference period is not in a pristine natural state. Therefore, many studies have reconstructed the Budyko curve equation based on the physical characteristics of the reference period catchment (Supplementary Fig. 6b), which may be a good practice for investigating the variations of individual catchments over different periods19,21,25. However, this study emphasizes the analysis of the interconnectedness between upstream and downstream catchments. Developing Budyko curve equations for each catchment would introduce greater uncertainties into subsequent analyses while compromising the comparability across catchments19. Consequently, this study adopts non-parametric curve equations to decompose the impacts of climate change and human activities on runoff variations. Additionally, multiple non-parametric water-energy balance curve equations are employed to ensure the reliability of the results.

In addition, the runoff during the reference period is also affected by anthropogenic disturbances18,88,89, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6c. Therefore, it is necessary to subtract the deviation between the reference period and the Budyko curve to reduce the discrepancies in anthropogenic impacts on runoff variation across different catchments22. Furthermore, the mid-to-downstream catchments in this study receive and utilize upstream external water resources. Under the assumption of long-term multi-year average conditions, the water loss through climatic evaporation or evapotranspiration from these external resources and reservoir regulation is negligible20. This portion of water represents an additional contribution to runoff changes due to human activities, distinct from the evapotranspiration losses caused by human activities17. Consequently, after subtracting this water volume, the actual evapotranspiration Point B’ in these catchments still adheres to the assumptions of the Budyko water-energy balance theory. The Budyko curve and decomposition method employed in this study remain applicable to these catchments. Thus, the shift in the relationship between aridity index and evaporation ratio from Point C to Point B still reflects the impact of human activities on runoff variation. The actual evapotranspiration Point B’ serves as an intermediate variable that cancels out when calculating the total contribution of human activities to runoff changes. Therefore, the upstream inflow recharge and reservoir regulation may cause the relationship between the drought index and evaporation ratio in the sub-catchment to deviate from the water supply control line of the Budyko framework, entering the blue-shaded region beyond this boundary (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 7, where \(1-{Q}_{{Sub}}/P > 1\)).

Therefore, based on the decomposition method illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6c, the formula for calculating the direct contribution of human activities to catchment runoff variation during the change period can be derived as follows:

where \({Q}_{1}\) and \({Q}_{2}\) respectively represent the multi-year averages of the runoff contributions from each sub-catchment during the reference period and change period. \({{AE}}_{1}^{{\prime} }/{P}_{1}\) and \({{AE}}_{2}^{{\prime} }/{P}_{2}\) respectively represent the theoretical evapotranspiration ratios corresponding to the aridity index for the reference period and the change period. Similarly, the contribution of climate change in the change period relative to the reference period to the runoff variation in the catchment area can be derived from Eq. (7). Then, the contribution rates of climate change and human activities to the variation in runoff of the sub-catchment can be calculated using the following formula:

where \({\omega }_{c}\) and \({\omega }_{h}\) are the percentage of the change in runoff contribution caused by climate change and human activities to the total change in runoff contribution of the sub-catchment, respectively; \({\omega }_{c} > 0\) (\({\omega }_{h} > 0\)) indicates a positive contribution from climate change (human activities), increasing the runoff contribution of the watershed30,45. Otherwise, it is a negative contribution, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6d.

Identify key climatic and human interference factors

Land use change directly reflects the alteration of the underlying surface conditions in watersheds and can also indirectly reflect changes in socio-economic water withdrawal and demand within the watershed, which has been widely used to represent the main factors of human activities causing natural runoff changes21,33,42. In this study, we define population density and various types of land use as different sources of human disturbance. Population density reflects domestic water demand, arable land indicates agricultural irrigation water use, construction land represents socio-economic water use, reservoirs and ponds indicate artificial water storage, while rivers, lakes, beaches, and permanent glaciers represent different types of natural water storage. Different land use types such as arable land, forest, and grassland also indicate the differences in surface runoff characteristics within the watershed.

In this study, we evaluate the correlation between the runoff contribution of each sub-catchment and various climatic and human interference factors using the Spearman correlation33 in OriginPro 2024 software:

where \(\rho\) represents the Spearman correlation coefficient, \({d}_{i}\) represents the difference in ranks for each pair of variables, and \(n\) is the sample size.

Causal discovery algorithm (PCMCI + )

We apply the Peter-Clark Momentary Conditional Independence Plus (PCMCI + ) causal discovery algorithm to further analyze causal relationships between the runoff contributions of each sub-catchment and the primary hydrological components (precipitation P and potential evapotranspiration PET) of the Budyko curve28,29,90. Additionally, we investigate potential dependencies among streamflow series at upstream and downstream hydrological stations. The causal discovery algorithm does not violate the mass conservation principle (\(Q=P-{PET}\))29. The PCMCI+ algorithm detects contemporaneous and lagged causal relationships in time series data through momentary conditional independence tests91. This method constructs a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) via a two-step process92: (1) a Markov set discovery algorithm (PC1) for conditional independence testing, and (2) the Momentary Conditional Independence (MCI) test for causal inference (Supplementary Fig. 8).

The PC1 algorithm initiates from a fully connected graph (Supplementary Fig. 8a). It progressively identifies conditional independence among variables by incrementally expanding the conditioning set and employing linear partial correlation tests93,94. This iterative process continues until it converges on a subset of fundamental links at a significance level of 0.05. The final output preserves only statistically significant causal relationships between variables (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Subsequently, building upon the estimated conditions identified by the PC1 algorithm, the second-stage MCI test assigns a partial correlation-based causal strength value (MCI) to each detected causal relationship (Supplementary Fig. 8c). The magnitude of the MCI quantifies the linkage intensity between variables90,95. The Python software for constructing a causal network is publicly available at https://tocsy.pik-potsdam.de/tigramite.php.

Ultimately, we conduct a comparative analysis to identify the key drivers behind runoff variations in each sub-catchment. Furthermore, we thoroughly investigate the interactive mechanisms between upstream and downstream watersheds under the combined influence of climate change and human activities.

Data availability

The precipitation dataset used in this study is publicly available from the National Tibetan Plateau Science Data Center (TPDC) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/faae7605-a0f2-4d18-b28f-5cee413766a2). The air temperature dataset is provided through TPDC. Potential evapotranspiration data are made available by TPDC. Land use data are provided by TPDC. Monthly runoff data are collected from the Hydrology Bureau of the Yellow River Conservancy Commission (http://www.yrcc.gov.cn/) and its published “Yellow River Hydrology Yearbook”. DEM data are downloaded from the Geospatial Data Cloud site of the Computer Network Information Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (http://www.gscloud.cn). Population distribution datasets are obtained from the Scientific Data Bank (https://www.scidb.cn/en/detail?dataSetId=849628989872930816). Data created in this study are openly available which can be found in Figshare repository with the https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28427867.

Code availability

The Python package for building causal networks is openly accessible at https://tocsy.pik-potsdam.de/tigramite.php.

References

Grill, G. et al. Mapping the world’s free-flowing rivers. Nature 569, 215–221 (2019).

Palmer, M. & Ruhi, A. Linkages between flow regime, biota, and ecosystem processes: Implications for river restoration. Science 365, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw2087 (2019).

Best, J. Anthropogenic stresses on the world’s big rivers. Nat. Geosci. 12, 7–21 (2018).

Jongman, B. et al. Declining vulnerability to river floods and the global benefits of adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414439112 (2015).

Barnett, T. P., Adam, J. C. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions. Nature 438, 303–309 (2005).

Vörösmarty, C. J. et al. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 467, 555–561 (2010).

Vörösmarty, C. J., Green, P., Salisbury, J. & Lammers, R. B. Global water resources: vulnerability from climate change and population growth. Science 289, 284–288 (2000).

Wu, Q. et al. Satellites reveal hotspots of global river extent change. Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37061-3 (2023).

Gudmundsson, L. et al. Globally observed trends in mean and extreme river flow attributed to climate change. Science 371, 1159 (2021).

Mazzoleni, M., Dottori, F., Cloke, H. L. & Di Baldassarre, G. Deciphering human influence on annual maximum flood extent at the global level. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00598-0 (2022).

Messager, M. L. et al. Global prevalence of non-perennial rivers and streams. Nature 594, 391–397 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Anthropogenic climate change has influenced global river flow seasonality. Science 383, 1009–1014 (2024).

Jaeger, K. L., Olden, J. D. & Pelland, N. A. Climate change poised to threaten hydrologic connectivity and endemic fishes in dryland streams. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 13894–13899 (2014).

Piao, S. et al. The impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in China. Nature 467, 43–51 (2010).

Milly, P. C. D., Dunne, K. A. & Vecchia, A. V. Global pattern of trends in streamflow and water availability in a changing climate. Nature 438, 347–350 (2005).

Yin, S. et al. Streamflow and sediment load changes from China’s large rivers: quantitative contributions of climate and human activity factors. Sci. Total Environ. 876, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162758 (2023).

Dey, P. & Mishra, A. Separating the impacts of climate change and human activities on streamflow: a review of methodologies and critical assumptions. J. Hydrol. 548, 278–290 (2017).

Sun, C. et al. Human activities have more impacts on the recent discharge reduction of the largest tributary of the Yellow River relative to last three centuries. Sci. Total Environ. 890, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164217 (2023).

Luan, J. et al. Evaluating the uncertainty of eight approaches for separating the impacts of climate change and human activities on streamflow. J. Hydrol. 601, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126605 (2021).

Luan, J. et al. Separating the impact of check dams on runoff from climate and vegetation changes. J. Hydrol. 614, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128565 (2022).

Wang, Y., Wang, S., Wang, C. & Zhao, W. Runoff sensitivity increases with land use/cover change contributing to runoff decline across the middle reaches of the Yellow River Basin. J. Hydrol. 600, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126536 (2021).

Zheng, H. et al. Responses of streamflow to climate and land surface change in the headwaters of the Yellow River Basin. Water Resources Res. 45, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007wr006665 (2009).

Zhao, Q. et al. Relative contribution of the Xiaolangdi dam to runoff changes in the Lower Yellow River. Land 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050521 (2021).

Yang, J., Wang, T., Yang, D. & Yang, Y. Insights into runoff changes in the source region of Yellow River under frozen ground degradation. J. Hydrol. 617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128892 (2023).

Wang, F., Ge, Q., Yu, Q., Wang, H. & Xu, X. Impacts of land-use and land-cover changes on river runoff in Yellow River Basin for period of 1956-2012. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 27, 13–24 (2017).

Hecht, J. S., Lacombe, G., Arias, M. E., Dang, T. D. & Piman, T. Hydropower dams of the Mekong River basin: a review of their hydrological impacts. J. Hydrol. 568, 285–300 (2019).

Wei, Y. et al. Spatial-temporal variation and periodic change in streamflow and suspended sediment discharge along the mainstream of the Yellow River during 1950-2013. Catena 140, 105–115 (2016).

Zaerpour, M. et al. Impacts of agriculture and snow dynamics on catchment water balance in the U.S. and Great Britain. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01891-w (2024).

Zaerpour, M. et al. Agriculture’s impact on water–energy balance varies across climates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2410521122 (2025).

Liu, J. & You, Y. The roles of catchment characteristics in precipitation partitioning within the Budyko framework. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 126, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021jd035168 (2021).

Guan, X. et al. Past variations and future projection of runoff in typical basins in 10 water zones, China. Sci. Total Environ. 798, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149277 (2021).

Ni, Y. et al. Intra-annual variation in the attribution of runoff evolution in the Yellow River source area. Catena 225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107032 (2023).

Bai, X. & Zhao, W. Impacts of climate change and anthropogenic stressors on runoff variations in major river basins in China since 1950. Sci. Total Environ. 898, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165349 (2023).

Yan, Z. et al. Ensemble projection of runoff in a large-scale basin: modeling with a global BMA approach. Water Resources Res. 56, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019wr026134 (2020).

Singh, N. K. & Basu, N. B. The human factor in seasonal streamflows across natural and managed watersheds of North America. Nat. Sustainability 5, 397–405 (2022).

Gu, H. et al. Seasonal catchment memory of high mountain rivers in the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38966-9 (2023).

Ji, G., Wu, L., Wang, L., Yan, D. & Lai, Z. Attribution analysis of seasonal runoff in the source region of the Yellow River using seasonal Budyko hypothesis. Land 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050542 (2021).

Veldkamp, T. I. E. et al. Water scarcity hotspots travel downstream due to human interventions in the 20th and 21st century. Nat. Commun. 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15697 (2017).

Feng, D. & Gleason, C. J. More flow upstream and less flow downstream: the changing form and function of global rivers. Science 386, 1305–1311 (2024).

Munia, H. et al. Water stress in global transboundary river basins: Significance of upstream water use on downstream stress. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/1/014002 (2016).

Giordano, M., Yoffe, S. B. & Wolf, A. T. International waters: Identifying basins at risk. Water Policy 5, 29–60 (2003).

Ni, Y. et al. Spatial difference analysis of the runoff evolution attribution in the Yellow River Basin. J. Hydrol. 612, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128149 (2022).

Ficklin, D. L., Abatzoglou, J. T., Robeson, S. M., Null, S. E. & Knouft, J. H. Natural and managed watersheds show similar responses to recent climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 8553–8557 (2018).

Datry, T., Larned, S. T. & Tockner, K. Intermittent rivers: A challenge for freshwater ecology. BioScience 64, 229–235 (2014).

Wang, D. & Hejazi, M. Quantifying the relative contribution of the climate and direct human impacts on mean annual streamflow in the contiguous United States. Water Resources Res. 47, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010wr010283 (2011).

Feng, X. et al. Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1019–1022 (2016).

Shi, C., Zhou, Y., Fan, X. & Shao, W. A study on the annual runoff change and its relationship with water and soil conservation practices and climate change in the middle Yellow River basin. Catena 100, 31–41 (2013).

Hu, C., Zhang, L., Wu, Q., Soomro, S.-E.-H. & Jian, S. Response of LUCC on runoff generation process in Middle Yellow River Basin: The Gushanchuan Basin. Water 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/w12051237 (2020).

Mu, X. M., Zhang, L., McVicar, T. R., Chille, B. S. & Gau, P. Analysis of the impact of conservation measures on stream flow regime in catchments of the Loess Plateau, China. Hydrol. Process. 21, 2124–2134 (2007).

Zhai, P. M., Zhang, X. B., Wan, H. & Pan, X. H. Trends in total precipitation and frequency of daily precipitation extremes over China. J. Clim. 18, 1096–1108 (2005).

Fu, B. J. Soil-erosion and its control in the Loess Plateau of China. Soil Use Manag. 5, 76–82 (1989).

Fu, G., Chen, S., Liu, C. & Shepard, D. Hydro-climatic trends of the Yellow River Basin for the last 50 years. Clim. Change 65, 149–178 (2004).

Zhang, X., Zhang, L., Zhao, J., Rustomji, P. & Hairsine, P. Responses of streamflow to changes in climate and land use/cover in the Loess Plateau, China. Water Resources Res. 44, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007wr006711 (2008).

Ren, D., Xu, X., Hao, Y. & Huang, G. Modeling and assessing field irrigation water use in a canal system of Hetao, upper Yellow River basin: application to maize, sunflower and watermelon. J. Hydrol. 532, 122–139 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Reduced sediment transport in the Yellow River due to anthropogenic changes. Nat. Geosci. 9, 38–41 (2015).

Wang, H. & Sun, F. Variability of annual sediment load and runoff in the Yellow River for the last 100 years (1919–2018). Sci. Total Environ. 758, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143715 (2021).

Zhang, Q., Liu, J., Singh, V. P., Shi, P. & Sun, P. Hydrological responses to climatic changes in the Yellow River basin, China: Climatic elasticity and streamflow prediction. J. Hydrol. 554, 635–645 (2017).

Li, H., Zhang, Q., Singh, V. P., Shi, P. & Sun, P. Hydrological effects of cropland and climatic changes in arid and semi-arid river basins: A case study from the Yellow River basin, China. J. Hydrol. 549, 547–557 (2017).

Ji, G., Lai, Z., Xia, H., Liu, H. & Wang, Z. Future runoff variation and flood disaster prediction of the Yellow River Basin based on CA-Markov and SWAT. Land 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/land10040421 (2021).

Li, X., Tian, Y., Sun, J., Wei, Y. & Li, F. Evolutionary effect separation of watershed characteristics for the multi-source contributions to runoff changes in the Yellow River, China. Ecol. Indicators 143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109398 (2022).

Xie, M. et al. Evolution of the precipitation-stream runoff relationship in different precipitation scenarios in the Yellow River Basin. Urban Clim. 51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101609 (2023).

Wang, W., Zhang, Y. & Tang, Q. Impact assessment of climate change and human activities on streamflow signatures in the Yellow River Basin using the Budyko hypothesis and derived differential equation. J. Hydrol. 591, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2020.125460 (2020).

Cui, J. & Jian, S. Spatiotemporal variation of runoff and its influencing factors in the Yellow River Basin, China. Water 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/w15112058 (2023).

Su, X., Li, X., Niu, Z., Wang, N. A. & Liang, X. A new complexity-based three-stage method to comprehensively quantify positive/negative contribution rates of climate change and human activities to changes in runoff in the upper Yellow River. J. Cleaner Prod. 287, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125017 (2021).

Li, X., Zhang, Y., Ma, N., Li, C. & Luan, J. Contrasting effects of climate and LULC change on blue water resources at varying temporal and spatial scales. Sci. Total Environ. 786, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147488 (2021).

Tang, Q. Global change hydrology: Terrestrial water cycle and global change. Sci. China Earth Sci. 63, 459–462 (2019).

Abbott, B. W. et al. Human domination of the global water cycle absent from depictions and perceptions. Nat. Geosci. 12, 533–540 (2019).

Liu, J. G., Li, S. X., Ouyang, Z. Y., Tam, C. & Chen, X. D. Ecological and socioeconomic effects of China’s policies for ecosystem services. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9477–9482 (2008).

Wang, Z., Xu, M., Liu, X., Singh, D. K. & Fu, X. Quantifying the impact of climate change and anthropogenic activities on runoff and sediment load reduction in a typical Loess Plateau watershed. J. Hydrol.: Regl. Stud. 39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2022.100992 (2022).

Cui, T. et al. Non-monotonic changes in Asian Water Towers’ streamflow at increasing warming levels. Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36804-6 (2023).

Menz, M. H. M., Dixon, K. W. & Hobbs, R. J. Hurdles and opportunities for landscape-scale restoration. Science 339, 526–527 (2013).

Wang, T. et al. Pervasive permafrost thaw exacerbates future risk of water shortage across the Tibetan Plateau. Earth’s Fut. 11, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022ef003463 (2023).

Yan, H. et al. A review of the eco-environmental impacts of the South-to-North water diversion: implications for interbasin water transfers. Engineering 30, 161–169 (2023).

Xie, P., Gu, H., Sang, Y. F., Wu, Z. & Singh, V. P. Comparison of different methods for detecting change points in hydroclimatic time series. J. Hydrol. 577, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.123973 (2019).

Guo, Z. et al. Increasing precipitation deteriorates the progress of pesticide reduction policy in the vulnerable watershed. npj Clean Water 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-023-00290-6 (2023).

Yang, M. et al. Temporal and spatial changes of runoff regime in the Yellow River Basin from 1956 to 2017. Water 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13223298 (2021).

Peng, S. 1-km monthly mean temperature dataset for China (1901–2023). Natl. Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environ. Data Cent. https://doi.org/10.11888/Meteoro.tpdc.270961 (2024).

Peng, S. 1-km monthly precipitation dataset for China (1901–2023). Natl. Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environ. Data Cent. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3114194 (2024).

Peng, S. 1-km monthly potential evapotranspiration dataset for China (1901–2023). Natl. Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environ. Data Cent. https://doi.org/10.11866/db.loess.2021.001 (2024).

Chinese, A. Landuse dataset in China (1980–2015). National Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environment Data Center. https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/a75843b4-6591-4a69-a5e4-6f94099ddc2d (2019).

Peng, S. Z., Gang, C. C., Cao, Y. & Chen, Y. M. Assessment of climate change trends over the Loess Plateau in China from 1901 to 2100. Int J. Climatol. 38, 2250–2264 (2018).

Haoran, W. et al. A dataset of district/county-level population distribution of China’s six national censuses. (Science Data Bank, 2022).

Pearson, K. In Breakthroughs in Statistics: Methodology and Distribution (eds Samuel Kotz & Norman L. Johnson), 11-28 (Springer New York, 1992).

Budyko, M. I. Climate and Life, Vol 508 (Academic, 1974).

Schreiber, P. U. ¨ ber die Beziehungen zwischen dem Niederschlag und der Wasserfu¨ hrung der Flu¨ ße in Mitteleuropa. Z. Meteorol. 21, 441–452 (1904).