Abstract

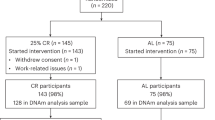

Caloric restriction (CR) slows biological aging and prolongs healthy lifespan in model organisms. Findings from the CALERIE randomized, controlled trial of long-term CR in healthy, nonobese humans broadly supports a similar pattern of effects in humans. To expand our understanding of the molecular pathways and biological processes underpinning CR effects in humans, we generated a series of genomic datasets from stored biospecimens collected from n = 218 participants during the trial. These data constitute a genomic data resource for a randomized controlled trial of an intervention targeting the biology of aging. Datasets include whole-genome single-nucleotide polymorphism genotypes, and three-timepoint-longitudinal DNA methylation, mRNA and small RNA datasets generated from blood, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue samples (total sample n = 2,327). The CALERIE Genomic Data Resource described in this article is available from the Aging Research Biobank. This multi-tissue, multi-omics, longitudinal data resource has great potential to advance translational geroscience. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT00427193.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Processed data can be accessed through the Aging Research Biobank (https://agingresearchbiobank.nia.nih.gov/studies/calerie/). Data use is restricted to noncommercial use in studies to determine factors that affect age-related conditions. Applications for data access include a brief summary of the research question and intended analysis and proof of IRB approval for the project. Summary tables of data can be found at Dryad via https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pzgmsbcxh (ref. 89). Original raw data may be obtained from the laboratory of D.W.B. (cac_geroscience@cumc.columbia.edu).

Code availability

Code used in the production of summary data and figures is available on Dryad via https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pzgmsbcxh (ref. 89) and GitHub via https://github.com/CPRyan/CALERIE_Genomic_Data_Resource/.

References

Bales, C. W. & Kraus, W. E. Caloric restriction: implications for human cardiometabolic health. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 33, 201–208 (2013).

Speakman, J. R. & Mitchell, S. E. Caloric restriction. Mol. Aspect. Med. 32, 159–221 (2011).

Fontana, L., Meyer, T. E., Klein, S. & Holloszy, J. O. Long-term calorie restriction is highly effective in reducing the risk for atherosclerosis in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6659–6663 (2004).

Meyer, T. E. et al. Long-term caloric restriction ameliorates the decline in diastolic function in humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 398–402 (2006).

Heilbronn, L. K. et al. Effect of 6-month calorie restriction on biomarkers of longevity, metabolic adaptation, and oxidative stress in overweight individualsa randomized controlled trial. JAMA 295, 1539–1548 (2006).

Walford, R. L., Harris, S. B. & Gunion, M. W. The calorically restricted low-fat nutrient-dense diet in Biosphere 2 significantly lowers blood glucose, total leukocyte count, cholesterol, and blood pressure in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 11533–11537 (1992).

Flanagan, E. W., Most, J., Mey, J. T. & Redman, L. M. Calorie restriction and aging in humans. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 40, 105–133 (2020).

Ravussin, E. et al. A 2-year randomized controlled trial of human caloric restriction: feasibility and effects on predictors of health span and longevity. J. Gerontol. Series A 70, 1097–1104 (2015).

Kraus, W. E. et al. 2 years of calorie restriction and cardiometabolic risk (CALERIE): exploratory outcomes of a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7, 673–683 (2019).

Belsky, D. W., Huffman, K. M., Pieper, C. F., Shalev, I. & Kraus, W. E. Change in the rate of biological aging in response to caloric restriction: CALERIE biobank analysis. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73, 4–10 (2018).

Kwon, D. & Belsky, D. W. A toolkit for quantification of biological age from blood chemistry and organ function test data: BioAge. Geroscience 43, 2795–2808 (2021).

Racette, S. B. et al. One year of caloric restriction in humans: feasibility and effects on body composition and abdominal adipose tissue. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61, 943–950 (2006).

Rochon, J. et al. Design and conduct of the CALERIE study: comprehensive assessment of the long-term effects of reducing intake of energy. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 66, 97–108 (2011).

Rickman, A. D. et al. The CALERIE study: design and methods of an innovative 25% caloric restriction intervention. Contemp. Clin. Trials 32, 874–881 (2011).

Ramaker, M. E. et al. Epigenome-wide association study analysis of calorie restriction in humans, CALERIE trial analysis. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glac168 (2022).

Lehne, B. et al. A coherent approach for analysis of the Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip improves data quality and performance in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome Biol. 16, 37 (2015).

Waziry, R. et al. Effect of long-term caloric restriction on DNA methylation measures of biological aging in healthy adults from the CALERIE trial. Nat. Aging https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00357-y (2023).

Salas, L. A. et al. Enhanced cell deconvolution of peripheral blood using DNA methylation for high-resolution immune profiling. Nat. Commun. 13, 761 (2022).

Belsky, D. W. et al. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. eLife 11, e73420 (2022).

Belsky, D. W. & Baccarelli, A. A. To promote healthy aging, focus on the environment. Nat Aging 3, 1334–1344 (2023).

Das, J. K. et al. Calorie restriction modulates the transcription of genes related to stress response and longevity in human muscle: the CALERIE study. Aging Cell 22, e13963 (2023).

Spadaro, O. et al. Caloric restriction in humans reveals immunometabolic regulators of health span. Science 375, 671–677 (2022).

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Moqri, M. et al. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell 186, 3758–3775 (2023).

Fiorito, G. et al. DNA methylation-based biomarkers of aging were slowed down in a two-year diet and physical activity intervention trial: the DAMA study. Aging Cell 20, e13439 (2021).

Fitzgerald, K. N., Campbell, T., Makarem, S. & Hodges, R. Potential reversal of biological age in women following an 8-week methylation-supportive diet and lifestyle program: a case series. Aging 15, 1833–1839 (2023).

Fitzgerald, K. N. et al. Potential reversal of epigenetic age using a diet and lifestyle intervention: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Aging 13, 9419–9432 (2021).

McEwen, L. M. et al. DNA methylation signatures in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a lifestyle intervention for women at midlife: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 43, 233–239 (2018).

Chen, L. et al. Effects of vitamin D3 supplementation on epigenetic aging in overweight and obese african americans with suboptimal vitamin D status: a randomized clinical trial. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 91–98 (2019).

Yi, L. et al. The efficacy and safety of β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) supplementation in healthy middle-aged adults: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-dependent clinical trial. GeroScience 45, 29–43 (2023).

Lee, E. et al. Exploring the effects of dasatinib, quercetin, and fisetin on DNA methylation clocks: a longitudinal study on senolytic interventions. Aging 16, 3088–3106 (2024).

Armenise, C. et al. Transcriptome profiling from adipose tissue during a low-calorie diet reveals predictors of weight and glycemic outcomes in obese, nondiabetic subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106, 736–746 (2017).

Benton, M. C. et al. An analysis of DNA methylation in human adipose tissue reveals differential modification of obesity genes before and after gastric bypass and weight loss. Genome Biol. 16, 8 (2015).

Castañer, O. et al. In vivo transcriptomic profile after a Mediterranean diet in high–cardiovascular risk patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 845–853 (2013).

McFarland, A. J., Ray, P. R., Bhai, S., Levine, B. D. & Price, T. J. RNA sequencing on muscle biopsy from a 5-week bed rest study reveals the effect of exercise and potential interactions with dorsal root ganglion neurons. Physiol. Rep. 10, e15176 (2022).

Pheiffer, C. et al. Changes in subcutaneous adipose tissue microRNA expression in response to exercise training in African women with obesity. Sci. Rep. 12, 18408 (2022).

Rönn, T. et al. A six months exercise intervention influences the Genome-wide DNA methylation pattern in human adipose tissue. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003572 (2013).

Maegawa, S. et al. Caloric restriction delays age-related methylation drift. Nat. Commun. 8, 539 (2017).

Mattison, J. A. et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature 489, 318–321 (2012).

Weindruch, R., Kayo, T., Lee, C. -K. & Prolla, T. A. Microarray profiling of gene expression in aging and its alteration by caloric restriction in mice. J. Nutr. 131, 918S–923S (2001).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 11, 303–327 (2019).

Bareja, A. et al. Liver-derived plasminogen mediates muscle stem cell expansion during caloric restriction through the plasminogen receptor Plg-RKT. Cell Rep. 43, 113881 (2024).

Domcke, S., Sinha, R., Levine, D. A., Sander, C. & Schultz, N. Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles. Nat. Commun. 4, 2126 (2013).

Oh, J. H. & Cho, J.-Y. Comparative oncology: overcoming human cancer through companion animal studies. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 725–734 (2023).

Redman, L. M. et al. Metabolic slowing and reduced oxidative damage with sustained caloric restriction support the rate of living and oxidative damage theories of aging. Cell Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.019 (2018).

Chen, Q. et al. OMICmAge: an integrative multi-omics approach to quantify biological age with electronic medical records. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.16.562114 (2023).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge version 2. Aging 14, 9484–9549 (2022).

Sehgal, R. et al. Systems Age: a single blood methylation test to quantify aging heterogeneity across 11 physiological systems. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.13.548904 (2023).

Ying, K. et al. Causality-enriched epigenetic age uncouples damage and adaptation. Nat. Aging https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00557-0 (2024).

Fong, S. et al. Principal component-based clinical aging clocks identify signatures of healthy aging and targets for clinical intervention. Nat. Aging 4, 1137–1152 (2024).

Rohart, F., Gautier, B., Singh, A. & Cao, K. -A. L. mixOmics: an R package for ‘omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005752 (2017).

Wang, B. et al. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat. Methods 11, 333–337 (2014).

Krassowski, M., Das, V., Sahu, S. K. & Misra, B. B. State of the field in multi-omics research: from computational needs to data mining and sharing. Front. Genet. 11, 610798 (2020).

Subramanian, I., Verma, S., Kumar, S., Jere, A. & Anamika, K. Multi-omics data integration, interpretation, and its application. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 14, 1177932219899051 (2020).

Das, S. K. et al. Body-composition changes in the Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (CALERIE)-2 study: a 2-y randomized controlled trial of calorie restriction in nonobese humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 105, 913–927 (2017).

Shen, W. et al. Effect of 2-year caloric restriction on organ and tissue size in nonobese 21- to 50-year-old adults in a randomized clinical trial: the CALERIE study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 114, 1295–1303 (2021).

Bergström, J. Percutaneous needle biopsy of skeletal muscle in physiological and clinical research. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 35, 609–616 (1975).

Sherry, S. T. et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 308–311 (2001).

Howie, B., Marchini, J. & Stephens, M. Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3 1, 457–470 (2011).

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Davis, S., Bilke, S., Triche Jr, T. & Bootwalla, M. methylumi: Handle Illumina methylation data. R package version 2.52.0 https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/methylumi.html (2024).

Huber, W. et al. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat. Methods 12, 115–121 (2015).

Aryee, M. J. et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics 30, 1363–1369 (2014).

Salas, L. A. et al. An optimized library for reference-based deconvolution of whole-blood biospecimens assayed using the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC BeadArray. Genome Biol. 19, 64 (2018).

Zheng, S. C. et al. A novel cell-type deconvolution algorithm reveals substantial contamination by immune cells in saliva, buccal and cervix. Epigenomics 10, 925–940 (2018).

Higgins-Chen, A. T. et al. A computational solution for bolstering reliability of epigenetic clocks: implications for clinical trials and longitudinal tracking. Nat. Aging 2, 644–661 (2022).

Daley, T. & Smith, A. D. Predicting the molecular complexity of sequencing libraries. Nat. Methods 10, 325–327 (2013).

Wang, L., Wang, S. & Li, W. RSeQC: quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 2184–2185 (2012).

Bushnell, B., Rood, J. & Singer, E. BBMerge–accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLoS ONE 12, e0185056 (2017).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. The Subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e108 (2013).

Torgerson, W. S. Multidimensional scaling: I. Theory and method. Psychometrika 17, 401–419 (1952).

Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M. & Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis (Wiley, 2011).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucl. Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015).

Warnes, M. G. R. et al. gplots: various R programming tools for plotting data. R package version 2 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gplots/ (2016).

Tibshirani, R., Walther, G. & Hastie, T. Estimating the number of clusters in a data set via the gap statistic. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 63, 411–423 (2001).

Charrad, M., Ghazzali, N., Boiteau, V. & Niknafs, A. NbClust: an R package for determining the relevant number of clusters in a data set. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v061.i06 (2014).

Robinson, M. D. & Oshlack, A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 11, R25 (2010).

Law, C. W., Chen, Y., Shi, W. & Smyth, G. K. voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 15, R29 (2014).

Liu, R. et al. Why weight? Modelling sample and observational level variability improves power in RNA-seq analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e97 (2015).

Law, C. W. et al. A guide to creating design matrices for gene expression experiments. F1000Res 9, 1444 (2020).

Smyth, G. K., Michaud, J. & Scott, H. S. Use of within-array replicate spots for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Bioinformatics 21, 2067–2075 (2005).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Korotkevich, G. et al. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/060012 (2021).

Luo, W., Friedman, M. S., Shedden, K., Hankenson, K. D. & Woolf, P. J. GAGE: generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 161 (2009).

Ryan, C. P. et al. CALERIE trial molecular data summary: DNA methylation, mRNA, smRNA for blood, adipose, and muscle. Dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pzgmsbcxh (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research received support from US National Institute on Aging Grants R01AG061378 (to D.W.B.), R33AG070455 (to K.H. and W.E.K.), R01AG054840 (to V.B.K.) and U01AG060908 (to S.H.) and from US National Cancer Institute Grant 5P30CA013696 (to A.F.). D.W.B. is a Fellow of the CIFAR CBD Network. This research utilized the FlowSorted.BloodExtended.EPIC software packages developed at Dartmouth College, which are governed by the licensing terms provided by Dartmouth Technology Transfer (https://github.com/immunomethylomics/FlowSorted.BloodExtended.EPIC/blob/main/SoftwareLicense.FlowSorted.BloodExtended.EPIC%20to%20sign.pdf). Figs. 1 and 2 and Extended Data Fig. 1 include images created in BioRender in the Columbia Aging Center Geroscience Computational Core. CALERIE is a registered trademark.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W.B., K.M.H., V.B.K., L.F. and S.H. designed the research; C.P.R., D.L.C., N.B., C.E.I., A.F., R.F., M.S.K., V.B.K., W.E.K., J.L.M., M.C.O., C.F.P., J.P.W., L.F., S.H., K.M.H. and D.W.B. conducted the research; C.P.R., D.L.C., N.B., R.F., J.M. and M.C.O. prepared the datasets; C.P.R. and R.F. analyzed the data; C.P.R. and D.W.B. wrote the paper; all authors contributed to critical review of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.W.B. and D.L.C. are listed as inventors of the Duke University and University of Otago invention DunedinPACE, which is licensed to TruDiagnostic. D.W.B. is consulting CSO and SAB chair of BellSant and serves on the SAB of the Hooke Clinic. The Regents of the University of California are the sole owner of patents and patent applications directed at epigenetic biomarkers for which S.H. is a named inventor; S.H. is a founder and paid consultant of the non-profit Epigenetic Clock Development Foundation that licenses these patents. S.H. is a Principal Investigator at the Altos Labs, Cambridge Institute of Science, a biomedical company that works on rejuvenation. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Aging thanks Jan Gruber and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Upset plot of samples for baseline and at least one follow-up.

The figure shows an upset plot displaying overlap of available datasets across treatment group, tissues, molecular data type. This figure is analogous to Fig. 2a, here only samples with baseline and at least one follow-up (12- or 24-months) are counted. The left-hand side shows tissue type (blood, muscle, or adipose), type of molecular data type (SNPs, DNAm, smRNAs, or mRNA), set size for each tissue and data type combination in number of unique individuals, and group (CR or AL). The bottom right-hand side shows points and connecting lines indicating overlapping intersections across tissues and data types color coded by treatment group (CR = red, AL = navy). The top right hand side shows a barchart indicating sample sizes for the overlapping intersections of tissue and datatypes. Each tissue and molecular data type combination is linked to a corresponding color scheme as follows: genomic variation (purple DNA), blood DNA methylation (red DNA with lollipops), blood small RNAs (smRNAs; dark red RNA fragments), muscle DNA methylation (blue DNA with lollipops), muscle smRNAs (blue RNA fragments), muscle mRNA (blue single RNA strand), adipose DNA methylation (yellow DNA with lollipops), adipose smRNAs (yellow RNA fragments), adipose mRNA (yellow single RNA strand). Created with BioRender.com.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Estimated cell composition for blood, muscle, and adipose samples based on DNA methylation deconvolution.

The figure shows estimated adipose, epithelial, fibroblast, and immune cell proportions for blood (Panel A; n=594), muscle (Panel B; n=168), and adipose (Panel C; n=161) tissue samples. For each tissue type, individual points represent individual samples. Proportion of cell types are shown as box and whisker plots showing median (horizontal line), 25th quartile (bottom of the box), 75th quartile (top of the box), and minimum and maximum values within 1.5 × IQR (interquartile range; top and bottom segments, respectively). Adipose cell types are colored in gold, epithelial cells are colored in blue, fibroblasts are colored in seagreen, and immune cells are colored in coral. Estimated cell proportions are based on DNA methylation and the hierarchical EpiDISH deconvolution method described in Zheng et al.67.

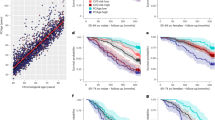

Extended Data Fig. 3 Associations of DNA methylation measures of aging with chronological age.

The figure shows DNA methylation measures of aging (Y-axis) against chronological age (X-axis) for n=212 men and women at pre-intervention baseline. The dashed colored line on each facet is the line of identity (intercept=0, slope=1), indicating where predicted epigenetic age or pace of aging would equal chronological age. Correlations with chronological age are as follows: Horvath Clock r=0.87, PC Horvath Clock r=0.84, Hannum Clock r=0.92, PC Hannum Clock r=0.88, Skin & Blood Clock r=0.94, PC Skin & Blood Clock r=0.80, PhenoAge Clock r=0.84, PC PhenoAge Clock r=0.85, GrimAge Clock r=0.93, PC GrimAge Clock r=0.92, DunedinPACE r=0.15.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Associations of age-residualized DNA methylation measures of aging with each other.

The figure shows correlations between age-residualized DNA methylation measures of aging for n=212 men and women at pre-intervention baseline with each other. The dashed red line on each facet is the fitted regression slopes. Pearson correlations between DNA methylation measures of aging are shown on the upper diagonal facets, with the shade of the facet indicating the strength of the correlation.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Signal intensity for blood DNA methylation.

Average intensity of methylated (x-axis) and unmethylated (y-axis) signals for DNAm from blood (n=594) relative to signal intensity of 10.5. Each sample is represented by a point, with samples from the Ad Libitum treatment group colored blue and samples from caloric restriction treatment group colored red.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Detection p-values for blood DNA methylation.

Average detection p-value for DNAm sampled from blood (n=594) relative to p-value of 0.05 (red dotted vertical line).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Signal intensity for muscle tissue DNA methylation.

Average intensity of methylated (x-axis) and unmethylated (y-axis) signals for DNAm from muscle tissue (n=168) relative to signal intensity of 10.5. Each sample is represented by a point, with samples from the Ad Libitum treatment group colored blue and samples from caloric restriction treatment group colored red.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Detection p-values for muscle tissue DNA methylation.

Average detection p-value for DNAm sampled from muscle (n=168) relative to p-value of 0.05 (red dotted vertical line).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Signal intensity for adipose tissue DNA methylation.

Average intensity of methylated (x-axis) and unmethylated (y-axis) signals for DNAm from adipose tissue (n=168) relative to signal intensity of 10.5. Each sample is represented by a point, with samples from the Ad Libitum treatment group colored blue and samples from caloric restriction treatment group colored red.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Detection p-values for adipose tissue DNA methylation.

Average detection p-value for DNAm sampled from adipose (n=161) relative to p-value of 0.05 (red dotted vertical line).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables 1–5

Supplementary Table 1. CALERIE Molecular Sample Availability Matrix. The table shows data availability for each CALERIE participant disaggregated by molecular data type (SNP-based genotype, DNA methylation, mRNA, smRNAs), tissue type (blood, plasma, muscle, adipose) and timepoint (baseline, 12-month follow-up, 24-month follow-up). Participant IDs and their corresponding treatment group are shown in columns 1 and 2. The presence of data for each molecular data type, tissue and timepoint for each participant are indicated by ‘1’. Absence of data for each molecular data type, tissue and timepoint for each participant are indicated by ‘0’. Supplementary Table 2. Adipose mRNA 12-month gene-set enrichment. Gene-set enrichment for differentially expressed genes in adipose tissue mRNA after comparing caloric restriction and AL treatment groups at 12-month follow-up relative to baseline. Enriched genes were filtered by FDR-corrected P value < 0.05 and ranked by absolute log2 fold change. Output includes the name of the pathway, enrichment nominal P value, enrichment Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery q value, enrichment score, normalized enrichment score, number of times a random gene set had a more extreme enrichment score value, size of the pathway after removing genes not present in the differential expression analysis and the direction of enrichment. Supplementary Table 3. Adipose mRNA 24-month gene-set enrichment. Gene-set enrichment for differentially expressed genes in adipose tissue mRNA when comparing caloric restriction and AL treatment groups at 24-month follow-up relative to baseline. Enriched genes were filtered by FDR-corrected P value < 0.05 and ranked by absolute log2 fold change. Output includes the name of the pathway, enrichment nominal P value, enrichment Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery q value, enrichment score, normalized enrichment score, number of times a random gene set had a more extreme enrichment score value, size of the pathway after removing genes not present in the differential expression analysis and the direction of enrichment. Supplementary Table 4. Differential expression for adipose mRNA by treatment group at 12-month follow-up. Results of two-sided different expression analysis of 19,755 genes with limma-voom with sample weighting to downweight the effect of sample outliers. Participant was modeled as a random effect using the duplicate correlation method. CR at 12-month follow-up was compared to AL at 12-month follow-up, relative to CR at baseline compared to AL at baseline (n = 34). Models included covariates for sex, age at baseline, BMI and RNA integrity number. Results show ENTREZID, gene symbol, log2 fold change, average expression level, the t-statistic, nominal P value, Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery q value and estimated beta value. Supplementary Table 5. Differential expression for adipose mRNA by treatment group at 24-month follow-up. Results of two-sided different expression analysis of 19,755 genes with limma-voom with sample weighting to downweight the effect of sample outliers. Participants were modeled as a random effect using the duplicate correlation method. CR at 24-month follow-up was compared to AL at 24-month follow-up, relative to CR at baseline compared to AL at baseline (n = 18). Models included covariates for sex, age at baseline, BMI and RNA integrity number. Results show ENTREZID, gene symbol, log2 fold change, average expression level, the t-statistic, nominal P value, Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery q value and estimated beta value.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryan, C.P., Corcoran, D.L., Banskota, N. et al. The CALERIE Genomic Data Resource. Nat Aging 5, 320–331 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00775-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00775-0