Abstract

Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum (SR/ER) Ca2+ ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) mediates Ca2+ reuptake into the SR in cardiomyocytes. The inactivation or downregulation of SERCA2a leads to reduced contractility in the failing heart. Here we show that SERCA2a is regulated by p22phox, a heterodimeric partner of NADPH oxidases. Endogenous p22phox was upregulated by pressure overload, but cardiac-specific p22phox knockout (cKO) in mice exacerbated heart failure, enhanced the downregulation of SERCA2a and increased oxidative stress in the SR. We show that p22phox interacts with SERCA2a, preventing its oxidation at Cys498 and subsequent degradation by the Smurf1 and Hrd1 E3 ubiquitin ligases. The exacerbation of SERCA2a downregulation and cardiac dysfunction following pressure overload in p22phox cKO mice was alleviated when these mice were crossed with SERCA2a-C498S knock-in mice, in which the oxidation-susceptible and degradation-promoting cysteine residue is mutated. Future molecular interventions to prevent the oxidation of SERCA2a at Cys498 may prevent its downregulation during heart failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

One of the major causes of reduced contractility in the failing heart is impaired Ca2+ cycling between the sarcoplasm and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The increased leakiness of ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2), potentiated activity of phospholamban (PLN)1 and downregulation of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum (SR/ER) Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a)2 are major drivers of heart failure progression. SERCA2a mediates Ca2+ reuptake into the SR/ER Ca2+ store from which Ca2+ is released through RyR2 for contraction, thereby having fundamental roles in controlling both cardiac relaxation and contraction. Thus, restoration of SERCA2a activity has been an important goal for preventing heart failure progression3. Importantly, however, rescue of SERCA2a downregulation by adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9)-mediated delivery of SERCA2a, although effective in animals, does not appear to be effective in humans. Complex posttranslational modifications of SERCA2a, including oxidation, SUMOylation and acetylation, may prevent effective restoration of SERCA2a function with the current strategy4.

Elevation of oxidative stress caused by increased electron leakage from damaged mitochondria, elevated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) from enzymatic sources such as NADPH oxidases and downregulation of antioxidants is a major mechanism driving the progression of heart failure5. Under oxidative stress, proteins in the heart undergo posttranslational modification on cysteine residues that can modify functions crucial for cardiomyocyte (CM) survival and homeostasis6. We have shown that the function of key signaling proteins, including HDAC4 (ref. 7), AMPK (ref. 8), mTOR (ref. 9) and Atg7 (ref. 10), in the heart is modulated by oxidation of cysteine residues, which in turn regulates various functions in the heart, including hypertrophy, survival, mitochondrial function and autophagy (reviewed in ref. 6). Cardiac stress disrupts the quality control mechanism of the SR/ER and induces accumulation of mis- and unfolded–damaged proteins, termed ER stress, which is often accompanied by elevated oxidative stress11. Together with electron leakage from mitochondria located nearby, elevated oxidative stress, in turn, effectively causes cysteine oxidation of SR/ER proteins, including SERCA2a. Although previous studies have shown that cysteine oxidation affects either the activity or the stability SERCA2a (refs. 12,13), the involvement of cysteine oxidation in SERCA2a downregulation during heart failure and the precise underlying mechanism through which oxidation of SERCA2a cysteine is regulated are poorly understood.

We report that p22phox, known as a component of the NADPH oxidase (Nox), regulates cysteine oxidation and degradation of SERCA2a during heart failure. Mice with cardiac-specific deletion of p22phox are more susceptible to heart failure during pressure overload even though the bulk production of ROS is attenuated. Unexpectedly, the knockdown of p22phox leads to increased ER-specific ROS production and oxidation of SERCA2a. On the other hand, p22phox directly binds to SERCA2a, protects it from oxidation of cysteine residues and prevents proteasome-mediated degradation of SERCA2a during oxidative stress. These results suggest that p22phox has a previously unrecognized role in regulating (protecting) the function of SERCA2a through direct interaction. Thus, the goals of this study were to clarify how p22phox affects cysteine oxidation and the function of SERCA2a in the heart and to reveal the molecular mechanism through which cysteine oxidation and the function of SERCA2a are regulated in the heart during heart failure caused by pressure overload.

Results

p22phox is upregulated in the failing human heart and in cardiomyocytes in response to pressure overload

The level of p22phox was evaluated in heart samples obtained from patients with dilated or ischemic cardiomyopathy and from donors with normal hearts. The level of p22phox was significantly higher in the patients’ hearts than in the control hearts (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Table 1).

a,b, Human heart LV samples obtained from healthy donor hearts and from patients with DCM or ICM were analyzed for p22phox protein expression levels (n = 8). a, The protein levels of p22phox, analyzed by western blotting with GAPDH as a loading control, in normal, DCM and ICM human heart LV lysates. b, Relative p22phox protein levels. c–e, Mice were subjected to TAC (1 week (1W) or 4 weeks (4W)) or sham operation, and the pressure gradient was assessed by Doppler on day 2 to confirm that appropriate levels of constriction were applied. After TAC, the heart LV tissues were analyzed for mRNA and protein expression. c, Relative p22phox mRNA levels (Sham and TAC 1W n = 7 and TAC 4W n = 8). d, The protein levels of p22phox were analyzed from whole heart tissue by western blotting with tubulin as loading control. e, The relative p22phox protein levels (n = 6). f–h, Following TAC 1W or sham operation, cardiomyocytes were isolated from adult mouse heart LV tissue and analyzed for protein and mRNA expression. f, The p22phox mRNA levels (Sham n = 8 and TAC 1W n = 7). g, The protein levels of p22phox, analyzed by western blotting with tubulin as loading control. h, The relative p22phox protein levels (n = 6). All bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey test (b, c and e) and unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) (e, f and h).

To assess the effects of pressure overload, we subjected mice to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) or sham surgery. p22phox expression in the heart was significantly elevated at both mRNA and protein levels after 1 week and 4 weeks of TAC (Fig. 1c–e). p22phox was also upregulated at the mRNA (Fig. 1f) and protein (Fig. 1g,h) levels in cardiomyocytes isolated from wild-type (WT) mice after 1 week of TAC, suggesting that p22phox is produced and upregulated in cardiomyocytes in response to pressure overload.

p22phox cKO mice developed exacerbated heart failure in response to pressure overload

To investigate the role of endogenous p22phox in the heart, we generated cardiomyocyte-specific p22phox knockout (p22phox cKO) mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). As p22phox is also expressed in non-myocytes, residual protein was still detectable in whole hearts (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d). However, the p22phox mRNA was significantly reduced in isolated cardiomyocytes from p22phox cKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 1e), and TAC-induced upregulation of p22phox observed in control mice was absent in p22phox cKO cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1f), confirming successful gene deletion. At baseline, p22phox cKO mice showed normal cardiac structure and function (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). However, following 1 week or 4 weeks of TAC, p22phox cKO mice developed more severe left ventricle (LV) dilation (increased LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) and LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD)) and greater LV dysfunction (reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF)) than control mice (Fig. 2a–e). In addition, lung congestion and LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) were significantly increased after 4 weeks of TAC in p22phox cKO mice (Fig. 2f,g), and aortic pressure gradients were reduced (Fig. 2h), consistent with impaired contractility. These mice also showed a blunted inotropic response to dobutamine (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d), indicating reduced cardiac reserve. Histological analyses show that the cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (CSA) was comparable between groups after TAC (Fig. 2i,j), but fibrosis was significantly exacerbated in p22phox cKO hearts (Fig. 2k,l). Importantly, survival after TAC was markedly lower in p22phox cKO mice (Fig. 2m). Collectively, these findings show that although p22phox is dispensable at baseline, its absence impairs the heart’s ability to compensate under pressure overload, leading to worsened LV dysfunction, enhanced fibrosis and increased mortality.

a–h, Control mice and p22phox cKO (homozygous) mice were subjected to sham operation or TAC (1W or 4W), and the pressure gradient was assessed by Doppler on day 2 to confirm that appropriate levels of constriction were applied. The mice were then analyzed for hypertrophic response and cardiac function by echocardiography. a, The hearts were collected, and the LVW (in mg) was measured and divided by the TL (in mm). The relative LV weight to tibia length (LVW/TL) ratio was plotted to compare the hypertrophic response (control: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 6, TAC 4W n = 10; p22phox cKO: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 10, TAC 4W n = 12). b, Representative echocardiographs from control and p22phox cKO mice subjected to sham operation or TAC (1W or 4W). c, LVEDD analyzed by echocardiography (control: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 9, TAC 4W n = 11; p22phox cKO: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 13, TAC 4W n = 13). d, LVESD analyzed by echocardiography (control: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 8, TAC 4W n = 10; p22phox cKO: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 12, TAC 4W n = 12). e, LVEF analyzed by echocardiography (control: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 9, TAC 4W n = 11; p22phox cKO: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 13, TAC 4W n = 13). f, The LungW (in mg) was measured and divided by the TL (in mm). The relative lung W/TL ratio was plotted to compare the extent of lung congestion (control: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 7, TAC 4W n = 9; p22phox cKO: sham n = 6, TAC 1W n = 11, TAC 4W n = 12). g,h, Hemodynamic measurements were obtained by catheterization from control and p22phox cKO (homozygous) mice that were subjected to sham operation or TAC (4W). g, LVEDP (control: sham n = 6, TAC 4W n = 7; p22phox cKO: sham n = 6, TAC 4W n = 6). h, Pressure gradient (n = 6). i–l, Histological evaluation of hypertrophy and fibrosis in control mice and p22phox cKO (homozygous) mice subjected to sham operation or TAC (4W). i, Wheat germ agglutinin staining showing cell size. j, Relative cell size (control: sham n = 6, TAC 4W n = 7; p22phox cKO: sham n = 6, TAC 4W n = 6). k, Picrosirius red staining. l, Relative fibrotic area fold change (control: sham n = 6, TAC 4W n = 6; p22phox cKO: sham n = 7, TAC 4W n = 7). m, Percentage survival in days after TAC surgery by Kaplan–Meier analysis with log rank test. All bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey test (a, c, d and j), one-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple-comparison test (e–g and l) and unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) (h).

LC–MS/MS identified binding of p22phox and SERCA2a

To uncover how p22phox loss contributes to cardiac dysfunction under pressure overload, we searched for p22phox-binding proteins. Lysates from adult mouse cardiomyocytes were incubated with or without Flag-tagged p22phox, followed by anti-Flag immunoprecipitation. Interacting proteins were identified using liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) with spectral counting. We identified 555 proteins by LC–MS/MS, of which 231 proteins bound well to Flag–p22phox (ratio > 1.5) with respect to the control group (Supplementary Table 4). The LC–MS/MS analysis showed that SERCA2a was the protein that bound most abundantly to Flag–p22phox in the mouse heart.

p22phox binds directly to SERCA2a

To further validate the interaction between p22phox and SERCA2a, co-immunoprecipitation revealed that SERCA2a was specifically detected in anti-p22phox immunoprecipitates, but not when a nonspecific control antibody was used (Fig. 3a). Conversely, p22phox was detected in the immunoprecipitate with anti-SERCA2a antibody (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that p22phox and SERCA2a physically interact with one another. A direct interaction between SERCA2a and p22phox was confirmed by in vitro binding assays using recombinant proteins (Fig. 3c). This interaction was further validated in cells using a proximity ligation assay (PLA), which revealed robust signals in the perinuclear region of cardiomyocytes when both anti-p22phox and anti-SERCA2a antibodies were applied, consistent with the complex formation in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 3d). To map the interaction domain, a series of SERCA2a deletion mutants were tested. p22phox bound to full-length SERCA2a, as well as SERCA2a 1–666, 334–666 and 334–998 constructs, but not to SERCA2a 1–333, identifying the 334–666 amino acid region as necessary for binding (Fig. 3e).

a,b, Immunoprecipitation (IP) of p22phox and SERCA2a from mouse whole heart tissue lysates using specific antibodies and with respective IgG control. Immunoprecipitates were loaded along with a 10% input fraction and immunoblotted (IB) for SERCA2a and p22phox protein. a, Immunoprecipitation of p22phox with co-immunoprecipitation of SERCA2a (performed at least three times independently). b, Immunoprecipitation of SERCA2a with co-immunoprecipitation of p22phox (performed at least three times independently). c, In vitro binding assay. Recombinant SERCA2a (rSERCA2a) and recombinant Flag-tagged p22phox (rFlag-p22phox) were incubated in IP cell lysis buffer and immunoprecipitated. The Flag-tagged p22phox, along with IgG control and the immunoprecipitated complexes, was washed and immunoblotted for SERCA2a and p22phox. The blots show binding of recombinant Flag-tagged p22phox (rFlag-p22phox) with rSERCA2a (performed at least three times independently). d, PLA performed in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiomyocytes were incubated with antibody diluent alone, rabbit anti-p22phox antibody alone, mouse anti-SERCA2a alone, and anti-p22phox and anti-SERCA2a antibodies for 2 h at 37 °C. Five random images per well were acquired using DAPI (blue nuclei) and Cy5 filters (red Cy5 PLA fluorescence signals are a result of the secondary antibody-conjugated PLA probe ligation and amplification only in the presence of antibodies against both p22phox and SERCA2a, indicating close proximity (<40 nm)) (performed at least three times independently). e, Top: in vitro binding of different fragments of recombinant His-tagged SERCA2a (rHis-SERCA2a) with Flag-tagged p22phox (rFlag-p22phox). SERCA2a His-tagged serial truncations were individually incubated with rFlag-p22phox, then pulled down with anti-Flag M2 beads and immunoblotted with anti-His antibody. The red rectangles indicate the different lengths of recombinant His-tagged SERCA2a (rHis-SERCA2a), seen in the input fraction and the immunoprecipitated lanes that bound to recombinant Flag-tagged p22phox (rFlag-p22phox) (performed at least three times independently). The green rectangles indicate absence of immunoprecipitated bands. Bottom: a schematic representation of the SERCA2a domain structure (three cytoplasmic domains (boxes): the actuator domain (A-domain), the nucleotide binding domain (N-domain) and the phosphorylation domain (P-domain), and transmembrane domains (lines)).

p22phox cKO mice showed abnormal Ca2+ handling

As SERCA2a transports cytosolic Ca2+ into the SR, Ca2+ transients were measured in isolated cardiomyocytes. At baseline, p22phox cKO cardiomyocytes showed a significantly reduced peak amplitude compared with the control (Fig. 4a,b). The peak amplitude of the Ca2+ transient after caffeine administration, indicating the total SR Ca2+ content, was then evaluated. At baseline, a rapid caffeine spike emptying the intracellular Ca2+ store in single cardiomyocytes revealed a significantly reduced SR Ca2+ content in the p22phox cKO mouse cardiomyocytes compared with in the control mouse cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4c). There was no significant difference in the percentage of fractional Ca2+ release between control and p22phox cKO cardiomyocytes at baseline (Fig. 4d). The decay constant of the Ca2+ transient (tau) was significantly greater in cardiomyocytes isolated from p22phox cKO mice than in those from control mice at baseline (Fig. 4e). The Ca2+ transients were also assessed in isolated cardiomyocytes after 1 week of pressure overload (TAC). The peak amplitude and the total SR Ca2+ content were significantly lower in the p22phox cKO mouse cardiomyocytes than in the control mouse cardiomyocytes after 1 week of TAC (Fig. 4a–c). There was no significant difference in the percentage of fractional Ca2+ release between control and p22phox cKO cardiomyocytes after 1 week of TAC (Fig. 4d). The tau was significantly greater in cardiomyocytes isolated from p22phox cKO mice than in those from control mice after TAC (Fig. 4e). These results are consistent with the notion that the activity of SERCA2a is reduced in p22phox cKO cardiomyocytes both at baseline and after TAC. On the other hand, the tau for the decay of Ca2+ transient after caffeine administration, reflecting the activity of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX)14, was not significant between control and p22phox cKO mice at baseline and after TAC (Fig. 4f), although it was significantly smaller after TAC compared with the sham operation in p22phox cKO mice, suggesting compensatory activation of NCX.

a–f, Ca2+ transient and SR Ca2+ content in p22phox cKO myocytes at baseline and after 1-week TAC. Adult cardiomyocytes were isolated from control and p22phox cKO mice using the Langendorff perfusion method. The cardiomyocytes were loaded with Fluo-4 AM. Ca2+ fluorescence intensity was recorded as the ratio of the fluorescence (F) over the basal diastolic fluorescence (F0). a, Twitch Ca2+ transient and SR Ca2+ content measured as the height of the caffeine (10 mM)-induced Ca2+ transient in representative ventricular myocytes from control and p22phox cKO mice at baseline and 1 week after TAC. Ca2+ fluorescence intensity was recorded as the ratio F/F0 of the fluorescence (F) over the basal diastolic fluorescence (F0). b–f, Summarized data for twitch representing the mean ± s.e. from three mice per condition and specified number of cells per mouse Ca2+ transient amplitude (WT: sham—6, 6, 9, TAC—7, 9, 9; p22phox cKO: sham—8, 8, 8, TAC—8, 7, 7) (b), SR Ca2+ content (WT: sham—7, 7, 8, TAC—7, 7, 10; p22phox cKO: sham—7, 7, 8, TAC—7, 7, 8) (c), fractional SR Ca2+ release (WT: sham—7, 7, 8, TAC—7, 7, 10; p22phox cKO: sham—7, 7, 8, TAC—7, 7, 8) (d), decay constant (tau) (WT: sham—6, 6, 7, TAC—7, 9, 11; p22phox cKO: sham—8, 7, 7, TAC—6, 6, 10) (e) and caffeine peak decay constant (tau) (WT: sham—8, 8, 8, TAC—8, 6, 10; p22phox cKO: sham—8, 3, 9, TAC—8, 6, 10) (f) in control and p22phox cKO ventricular myocytes at baseline and after 1-week TAC. The individual data points from cells of each mouse are represented by dots (filled black and blue dots and black empty dots). The statistical analysis was conducted using the nested t-test (two tailed) (c and f), nested one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test (b and e), and nested one-way ANOVA and Šidák’s multiple-comparison test (d). Hierarchical clustering dendrogram analysis was performed, and the dendrogram is provided in the source data.

p22phox posttranscriptionally regulates SERCA2a protein levels

Given altered calcium handling in p22phox cKO mice, we examined how endogenous p22phox regulates key cardiac calcium handling genes at baseline and 1 week after pressure overload. The relative mRNA levels of SERCA2a, PLN, NCX and ryanodine receptor (RyR) were not significantly different between control and p22phox cKO mice at baseline (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 2e,f). Although the levels of SERCA2a, PLN and RyR mRNA expression were significantly decreased in both p22phox cKO and control mice after 1 week of pressure overload, there was no significant difference between p22phox cKO and control mice (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 2f). As p22phox interacts with SERCA2a, we examined SERCA2a protein levels. Despite there being no change in the mRNA, the SERCA2a protein was significantly reduced in p22phox cKO mice compared with controls, both at baseline and after pressure overload (Fig. 5c,d). Similarly, in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes with small interfering RNA-mediated p22phox knockdown, SERCA2a mRNA levels were unaltered but the protein level of SERCA2a was significantly smaller after p22phox knockdown (Fig. 5e–g). These results suggest that p22phox may control the SERCA2a protein level through posttranscriptional mechanisms. PLN inhibits SERCA2a, but this inhibition is relieved upon phosphorylation by protein kinase A (ref. 15). In p22phox cKO mice, phosphorylated phospholamban protein levels were significantly higher than in controls, suggesting a compensatory response to reduced SERCA2a (Fig. 5h,i). Relative ATPase activity in isolated SR fractions from control and p22phox cKO mice showed no significant difference when normalized to SERCA2a levels (Fig. 5j).

a–d, Mouse heart tissues from control and p22phox cKO mice after sham operation or 1-week TAC were analyzed for mRNA by quantitative PCR and protein expression by immunoblotting. a, Relative SERCA2a mRNA expression in the hearts of control and p22phox cKO mice (sham: WT—10, p22phox cKO—11; TAC 1W: WT—8, p22phox cKO—7). b, Relative PLN mRNA expression in the hearts of control and p22phox cKO mice (sham: WT—10, p22phox cKO—11; TAC 1W: WT—8, p22phox cKO—7). c, Representative immunoblots from the heart LV tissue lysates of control and p22phox cKO mice after sham and 1-week and 4-week TAC surgery showing changes in SERCA2a protein levels. d, Relative SERCA2a protein expression expressed as the ratio of SERCA2a to GAPDH (sham: WT—8, p22phox cKO—8; TAC 1W: WT—8, p22phox cKO—8; TAC 4W: WT—8, p22phox cKO—8). e, Relative SERCA2a mRNA expression analyzed by quantitative PCR in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes that were transfected with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA (n = 9). f, Representative immunoblots of SERCA2a from rat neonatal cardiomyocyte lysates that were transfected with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA. g, Relative SERCA2a protein levels after normalization to GAPDH (n = 7). h, Representative immunoblots of T-PLN and phosphorylated (serine 16/17)-PLN (P-PLN (Ser 16/17) from the heart LV tissue lysates of control and p22phox cKO mice under the sham condition. i, Relative phosphorylated to total phospholamban levels in the heart tissue lysates of control and p22phox cKO mice under the sham condition (n = 6). j, The SR fraction was isolated from control and p22phox cKO (homozygous knockout) mouse hearts, and the specific SERCA2a ATPase activity of the fraction was assessed and normalized to the SERCa2a level in the SR fraction. The graph shows relative ATPase activity (normalized to SERCA2a levels) in the control and p22phox cKO SR fraction (n = 8). All bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey test (a, b and d) and unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) (e, g, i and j).

SERCA2a overexpression attenuated pressure overload-induced LV dysfunction in p22phox cKO mice

To show the role of SERCA2a downregulation in cardiac dysfunction in p22phox cKO mice under pressure overload, we performed rescue experiments using cardiomyocyte-specific SERCA2a expression via AAV9–cTnT–SERCA2a. Injection of AAV9–cTnT–SERCA2a increased cardiac SERCA2a expression in both control and p22phox cKO mice in both the sham and TAC groups (Extended Data Fig. 1a–d). No significant difference in LV tissue weight (LVW)/tibia length (TL) was observed in the presence of SERCA2a overexpression either after the sham operation or 4 weeks after TAC compared with in an eGFP overexpression group (control) (Extended Data Fig. 1e). The increase in lung weight observed after 4 weeks of TAC in p22phox cKO mice was attenuated in p22phox cKO mice injected with AAV9–cTnT–SERCA2a (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Moreover, LVEF after 4 weeks of TAC was significantly reduced in p22phox cKO mice, but not in p22phox cKO mice injected with AAV9–cTnT–SERCA2a (Extended Data Fig. 1g). These data suggest that supplementation of SERCA2a levels in cardiomyocytes rescues cardiac dysfunction associated with a lack of p22phox. Thus, SERCA2a downregulation has an important role in mediating cardiac dysfunction in p22phox cKO mice.

p22phox protected SERCA2a against oxidation and degradation

We investigated how p22phox regulates SERCA2a protein expression, given that SERCA2a is sensitive to oxidative modification, which can promote its degradation or reduce its activity in a context-dependent manner16. As p22phox interacts with SERCA2a, and its loss reduces SERCA2a protein levels, we hypothesized that p22phox modulates SERCA2a oxidation.

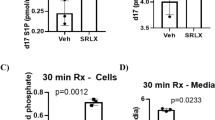

To assess oxidative stress, we measured total dityrosinated proteins and tissue-released H2O2 in p22phox cKO mice. While both markers increased after pressure overload in control and p22phox cKO mouse hearts, their levels were significantly lower in p22phox cKO mice (Fig. 6a–c). However, ER-localized HyPer fluorescence revealed higher H2O2 signals in p22phox knockdown cardiomyocytes compared with controls (Fig. 6d,e and Extended Data Fig. 2a,b), indicating that p22phox loss increases local oxidative stress in the ER, despite lower total cardiac oxidative stress.

a, Mouse heart tissues from control and p22phox cKO mice after the sham operation or 4-week TAC were analyzed for dityrosine levels (a marker of oxidative stress on tyrosine residues of proteins) by immunoblotting. The figure shows a representative immunoblot for dityrosine levels with GAPDH as loading control. b, Quantification of dityrosine protein levels as the ratio of relative dityrosine to GAPDH (n = 6). c, Mouse heart tissues from control and p22phox cKO mice after the sham operation or 1-week TAC were analyzed for levels of H2O2 released using Amplex red reagent by comparison against known H2O2 standards. The graph shows H2O2 levels in the tissue normalized to the weight of the tissue in mg (n = 6). d, Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were transduced with adenoviruses expressing ER-HyPer (ER-targeting ratiometric fluorescence sensor protein that detects H2O2 levels) and co-transfected with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA. The images shown are representative of the fluorescence ratiometric (excitation peak at 500 nm to excitation peak at 420 nm) images from cells with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA (the color scale indicates low to high ROS levels) (performed at least three times independently). e, Quantification of the number of high ratio cells to total cells per field from control siRNA or p22phox siRNA-treated cells, expressed as a percentage (n = 5). f, Left ventricular homogenates from control and p22phox cKO mice were incubated with BIAM and pulled down with avidin resin. The pull-down fractions and whole cell lysates (WCL) were immunoblotted for SERCA2a. The figure shows a representative immunoblot of SERCA2a labeled with BIAM from control and p22phox cKO mouse LV lysates. g, Quantification of BIAM–SERCA2a normalized by total SERCA2a in control and p22phox cKO mouse LV lysates (data from six mice per group). h, The overlay extract ion chromatograms of peptide SMoxSVYC498-biotinTPNKPSR in control and KO. The PEO-iodoacetyl-LC-biotin modification on cysteine represents the reduced form of cysteine. The dramatic decrease in the amount of the reduced form of cysteine at C498 in the KO indicates that the KO has more oxidized C498. i–m, Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were transduced with Ad–Flag–SERCA2a WT or Ad–Flag–SERCA2a-C498S mutant in the presence or absence of p22phox siRNA. i, Representative immunoblots of BIAM-labeled Flag-SERCA2a obtained from NRVMs that were transfected with Ad–Flag–SERCA2a WT or Ad–Flag–SERCA2a-C498S mutant in the presence or absence of p22phox siRNA. SE, short exposure; LE, long exposure. j, Quantification analyses of BIAM–Flag–SERCA2a normalized by total Flag–SERCA2a in l (n = 6). k, Representative immunoblots of Flag–SERCA2a in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes transfected with Ad–Flag–SERCA2a WT or Ad–Flag–SERCA2a-C498S mutant in the presence or absence of p22phox siRNA. l, Quantification of the Flag–SERCA2a WT protein expression levels in k (n = 12). m, Quantification of the Flag–SERCA2a-C498S mutant protein expression in k (n = 12). All bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey test (b, c and j) and unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) (e, g, l and m).

As multiple cysteine residues are subjected to oxidative modifications17,18, the extent of cysteine oxidation in SERCA2a was evaluated by blocking free reactive cysteine thiols with biotinylated iodoacetamide (BIAM) labeling and pull-down. There was significantly less BIAM-labeled SERCA2a in the heart in p22phox cKO mice than in control mice (Fig. 6f,g), indicating that the SERCA2a cysteine residues are more oxidized in p22phox cKO mice than in control mice.

We then evaluated redox-sensitive cysteines in p22phox cKO and control mouse hearts. Reduced free cysteines in the heart at the time of collection were irreversibly labeled with BIAM, whereas oxidized cysteines were first reduced with dithiothreitol (DTT) and then labeled with biotin-free IAM. LC–MS/MS showed that BIAM labeling of 7 cysteines (Cys344/349, Cys447, Cys471, Cys498, Cys560 and Cys669) was reduced by 30% or more in p22phox cKO mouse hearts compared with in control hearts, excluding low-label-efficiency (<1%) cysteines. Although several cysteines in SERCA2a were more oxidized in p22phox cKO mice than in control mice, Cys498 was oxidized to the greatest extent (Fig. 6h). To evaluate the functional significance of Cys498 oxidation, we generated adenoviruses harboring SERCA2a-C498S (Ad–Flag–SERCA2a-C498S) and studied how the Cys498 oxidation resistant mutation affects the overall oxidation status of SERCA2a. Cardiomyocytes transduced with Ad–Flag–SERCA2a-C498S showed significantly less BIAM labeling of Flag–SERCA2a than those transduced with Ad–Flag–SERCA2a WT (Fig. 6i,j). Furthermore, cardiomyocytes transduced with Ad–Flag–SERCA2a-C498S showed no further reduction in the amount of BIAM-labeled Flag–SERCA2a in the absence of p22phox compared with in the presence of p22phox. These results indicate that Cys498 is a major site of cysteine oxidation in SERCA2a in the absence of p22phox. In addition, the decrease in the SERCA2a level in the absence of p22phox was significantly alleviated in the presence of SERCA2a-C498S in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6k–m). These results suggest that the absence of p22phox results in the oxidation of SERCA2a at Cys498 and negatively affects the protein level of SERCA2a.

To identify the source of H2O2 in the ER in the absence of p22phox, we evaluated whether the increased ER-localized oxidative stress is mediated by Nox4, a partner of p22phox in the ER. We have shown previously that a lack of anti-apoptotic HS-1-associated protein X-1 (HAX-1), a regulator of ER-mediated cell survival, leads to increased oxidative stress in the ER through a Nox4-dependent mechanism12. The ER-localized HyPer fluorescence ratio was not affected by Nox4 downregulation in either the presence or absence of p22phox knockdown (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). Although the knockdown of p22phox decreased the protein levels of both Nox4 and SERCA2a, the knockdown of Nox4 did not decrease SERCA2a levels (Extended Data Fig. 2c–e). p22phox downregulation also decreased Nox2 protein levels (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). These data suggest that upregulation of H2O2 and downregulation of SERCA2a in response to p22phox downregulation are independent of Nox4 or Nox2. Furthermore, knockdown of p22phox did not alter the mitochondria-localized Mito-HyPer fluorescence ratio compared with the control (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f), excluding mitochondria-derived oxidative stress in the p22phox-deficient condition. Interestingly, the ER-localized HyPer fluorescence ratio was high when SERCA2a was downregulated (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f). Thus, increased oxidative stress in the ER in response to downregulation of p22phox is associated with SERCA2a downregulation.

SERCA2a undergoes ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in the absence of p22phox

As the protein level of SERCA2a was downregulated in the absence of p22phox, the possibility of SERCA2a ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome was investigated. Flag-tagged WT SERCA2a was immunoprecipitated from neonatal rat cardiomyocytes transduced with adenoviruses harboring LacZ or p22phox short hairpin RNA and administered epoxomicin, an irreversible selective proteasome inhibitor. SERCA2a was more highly ubiquitinated (K48-linked ubiquitination) in the presence of p22phox downregulation (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Cycloheximide chase assays were conducted in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes expressing either Flag-tagged wild-type SERCA2a or C498S SERCA2a in the presence of either LacZ or p22phox shRNA and epoxomicin. Although WT SERCA2a was susceptible to proteasomal degradation in the absence of p22phox, C498S SERCA2a was more stable than WT SERCA2a even in the absence of p22phox (Extended Data Fig. 4a–d). Moreover, siRNA-mediated knockdown of proteasome subunit alpha type-3 (PSMA3), a subunit of the 20S proteasome core and a part of the 26S proteasome, rescued the SERCA2a levels downregulated in the presence of p22phox knockdown (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f), suggesting that SERCA2a undergoes proteasomal degradation in the absence of p22phox.

Inhibition of the endogenous interaction between SERCA2a and p22phox leads to SERCA2a oxidation and degradation

We next examined how p22phox–SERCA2a interaction influences SERCA2a stability. We expressed a small fragment of SERCA2a encompassing the p22phox–SERCA2a interaction domain as a minigene in cardiomyocytes to block endogenous p22phox–SERCA2a interaction in vitro. Adenoviruses harboring SERCA2a (334–666) from rat SERCA2a with an N-terminal HA tag was transduced into rat neonatal cardiomyocytes, and the level of SERCA2a was determined by western blotting. Expression of the SERCA2a (334–666)–HA protein resulted in downregulation of endogenous SERCA2a levels in a dose-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). As observed earlier in this study, immunoprecipitation of the SERCA2a (334–666)–HA protein co-immunoprecipitated endogenous p22phox (Extended Data Fig. 5c), and, as expected, the interaction between endogenous full-length SERCA2a and p22phox was diminished in the presence of SERCA2a (334–666)–HA (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Proteasome inhibition with MG132 partially rescued the lowered SERCA2a protein level in the presence of SERCA2a (334–666)-HA (Extended Data Fig. 5). To evaluate how the presence of the minigene affects the oxidation status of SERCA2a, BIAM pull-down assays were conducted with cardiomyocytes transduced with either Ad–LacZ or Ad–SERCA2a (334–666)-HA in the presence of MG132. Cardiomyocytes treated with H2O2 served as positive control. BIAM–SERCA2a pull-down was lower in the presence of SERCA2a (334–666)-HA than in the presence of LacZ (Extended Data Fig. 5g,h). Furthermore, WT mice injected with AAV9–cTnT–mSERCA2a (333–666)–Flag (minigene) showed lower endogenous SERCA2a levels than those injected with AAV9–cTnT–eGFP (Extended Data Fig. 5i,j). These data suggest that SERCA2a (334–666) binds and sequesters endogenous p22phox, thereby leading to increased oxidation and degradation of endogenous SERCA2a protein.

SERCA2a interacts with Smurf1 and Hrd1 E3 ubiquitin ligases under oxidative stress and undergoes proteasomal degradation

In the absence of p22phox, SERCA2a undergoes ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Therefore, the E3 ubiquitin ligase targeting SERCA2a under oxidative stress was investigated. Smad ubiquitination regulatory factor 1 (Smurf1), a member of the HECT family of E3 ligases, is involved in activin type II receptor-induced degradation of SERCA2a during aging and heart failure19. Co-immunoprecipitation with SERCA2a antibody showed that SERCA2a interacts with Smurf1 at baseline, and this interaction is enhanced under H2O2-induced oxidative stress (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Interestingly, immunoprecipitation of HA-tagged ubiquitin also showed enhanced Smurf1 association with SERCA2a under oxidative stress (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The results also show that Smurf1 is more highly ubiquitinated under oxidative stress (Supplementary Fig. 4a), probably owing to autoubiquitination, which is known to take place in HECT type E3 ubiquitin ligases20. Knockdown of Smurf1 using siRNA partially rescued the H2O2-mediated downregulation of SERCA2a (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c).

SERCA2 undergoes ER-associated degradation (ERAD)21. Therefore, the involvement of HMG-CoA reductase degradation protein 1 (Hrd1), an ERAD-specific RING family E3 ubiquitin ligase22, in the degradation of SERCA2a was also investigated in this study. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that SERCA2a interacts with Hrd1 and that this interaction is also enhanced in the presence of H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Knockdown of Hrd1 alleviated H2O2-induced downregulation of SERCA2a (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f).

Co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that SERCA2a interacts with both Smurf1 and Hrd1, with these interactions markedly enhanced in p22phox knockdown cells treated with epoxomicin (Fig. 7a). Knockdown of Smurf1 or Hrd1 independently led to a partial rescue of SERCA2a levels in p22phox-deficient cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7b–e). Immunofluorescence showed increased colocalization of SERCA2a and Hrd1 under p22phox knockdown conditions (Fig. 7f,g). In addition, colocalization of SERCA2a, Hrd1 and the 20S proteasome subunit PSMA3 was elevated in the absence of p22phox (Fig. 7h,i). These findings indicate that Smurf1 and Hrd1 mediate proteasomal degradation of SERCA2a in the absence of p22phox.

a, NRVMs were transfected with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA for 48 h and treated with MG132 for 3 h. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either SERCA2a antibody or IgG control antibody and checked by immunoblotting for interaction with Smurf1 or Hrd1 E3 ubiquitin ligases. The immunoblots show enhanced binding of both Smurf1 and Hrd1 E3 ubiquitin ligases with SERCA2a in the absence of p22phox. Epoxomicin treatment at baseline also showed SERCA2a interaction with Hrd1 and Smurf1 (performed at least three times independently). b–e, NRVMs were transfected with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA together with Smurf1 or Hrd1 siRNA as indicated for 48 h. Cell lysates were collected and analyzed for protein levels of SERCA2a by immunoblotting. b, Representative immunoblots of SERCA2a with GAPDH as loading control. Knockdown of Smurf1 and p22phox is also validated. c, Relative SERCA2a protein levels in b (n = 6). d, Representative immunoblots of SERCA2a with GAPDH as loading control. Knockdown of Hrd1 and p22phox is also validated. e, Relative SERCA2a protein levels in c (n = 6). f–h, NRVMs were transfected with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA for 48 h and stained by immunofluorescence. Images were acquired by confocal microscopy. The blue color indicates DAPI (nucleus), green is SERCA2a, red is Hrd1 and yellow is the colocalization channel. f, Representative all-channel confocal microscopy images showing colocalization of SERCA2a and Hrd1. g, Three-dimensional (3D) fluorescence reconstructed image using IMARIS software after confocal microscopic image acquisition with z-stacks. h, The quantification of colocalization was calculated as the ratio of the volume of colocalization to the volume of SERCA2a in each cell following IMARIS software analysis (n = 6). i, Representative immunofluorescence images from control siRNA or p22phox siRNA-treated NRVMs stained with DAPI (white: pseudo color), SERCA2a (red), Hrd1 (blue) and PSMA3 (green). Individual channels are shown separately, and the merge channel is shown enlarged. The purple arrows indicate colocalization of SERCA2a with Hrd1, and the white arrows indicate triple colocalization of SERCA2a, Hrd1 and PSMA3. j, The quantification of triple colocalization was calculated as the ratio of the volume of triple colocalization to the volume of SERCA2a in each cell following IMARIS software analysis (n = 5). All bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey test (c and e) and unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) (h and j).

SERCA2a-C498S knock-in mice show cardioprotection under pressure overload

To evaluate the role of SERCA2a Cys498 oxidation in vivo, we generated SERCA2a-C498S knock-in (KI) mice (Supplementary Fig. 5). Calcium transients in cardiomyocytes from WT and SERCA2a-C498S KI mice (heterozygous and homozygous) revealed no significant differences in amplitude (F/F0), SR calcium content or tau, indicating preserved calcium handling at baseline (Supplementary Fig. 6). Echocardiography confirmed that SERCA2a-C498S KI (homozygous) mice show normal baseline cardiac function and intact cardiac reserve in response to dobutamine (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Following 3 weeks of TAC or sham surgery, both heterozygous and homozygous KI mice showed preserved ejection fraction (Supplementary Fig. 7b,c), reduced hypertrophy (LVW/TL) (Supplementary Fig. 7d), less lung congestion (lung tissue weight (LungW)/TL) (Supplementary Fig. 7e), smaller cardiomyocyte size (Supplementary Fig. 7f,g) and less interstitial fibrosis (Supplementary Fig. 7h,i) compared with WT mice. TAC reduced RyR2, NCX1 and SERCA2a mRNA levels across all groups (Supplementary Fig. 7j–l,o), but SERCA2a-C498S KI mice tended to show lower NCX1 and SERCA2a expression than WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 7k,o). TAC-induced increases in the P-PLN/total PLN (T-PLN) ratio were blunted in SERCA2a-C498S KI mice (Supplementary Fig. 7m,n). Notably, SERCA2a protein levels were preserved in both heterozygous and homozygous SERCA2a-C498S KI mice after TAC, suggesting increased protein stability (Supplementary Fig. 7p,q). Co-immunoprecipitation assays showed reduced interaction between SERCA2a and Smurf1/Hrd1 in SERCA2a-C498S KI mice (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In BIAM pull-down assays, TAC reduced BIAM labeling of SERCA2a in WT mice, consistent with oxidation of cysteine thiols, while labeling remained unchanged in SERCA2a-C498S KI mice, indicating protection from Cys498 oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c). Together, these findings show that oxidation of SERCA2a at Cys498 during pressure overload promotes its degradation, contributing to cardiac dysfunction, and that the C498S mutation confers protective effects by maintaining SERCA2a levels and cardiac function.

p22phox cKO mice with SERCA2a-C498S KI are protected against progression to heart failure under pressure overload

To assess the functional importance of SERCA2a Cys498 oxidation, we crossed SERCA2a-C498S KI mice with p22phox cKO mice, followed by 3 weeks of TAC or sham surgery. Consistent with the aforementioned findings, the cross with SERCA2a-C498S KI mice rescued cardiac dysfunction and preserved SERCA2a levels in p22phox cKO mice during pressure overload (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 9). The cross with heterozygous SERCA2a-C498S KI mice restored LVEF, reduced the LVW/TL and lung W/TL ratios (Fig. 8a–d) and mitigated fibrosis and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Supplementary Fig. 9a–d) in p22phox cKO mice. SERCA2a protein levels were significantly higher in p22phox cKO plus SERCA2a-C498S KI mice compared with p22phox cKO alone mice in both sham and TAC conditions (Fig. 8e,f). Importantly, the interaction of SERCA2a with Smurf1 and Hrd1, elevated in p22phox cKO mice, was suppressed in the presence of the C498S KI mutation (Supplementary Fig. 9e). Cardiomyocyte contractility was not significantly altered by SERCA2a-C498S KI compared with the control. However, the reduced contractility in p22phox cKO mice was fully restored by their cross with SERCA2a-C498S KI mice both at baseline and during isoproterenol stimulation (Fig. 8g,h). Similarly, calcium transient defects (reduced amplitude and prolonged tau), seen in p22phox cKO cardiomyocytes, were normalized in the presence of SERCA2a-C498S KI, achieving values comparable to those of the wild type (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). Despite these functional improvements, SERCA2a ATPase activity remained unchanged in WT, p22phox cKO, SERCA2a-C498S KI and double-mutant groups (Supplementary Fig. 9f), suggesting that the protein level, not enzymatic function, is the critical determinant of dysfunction in p22phox-deficient hearts. Collectively, these findings identify Cys498 oxidation as a key regulatory site mediating SERCA2a degradation and cardiac dysfunction in the absence of p22phox.

Control (wild type +/+ MHC cre+ or p22phox flox/flox/+ cre−), p22phox cKO (flox/flox MHC cre+), SERCA2a-C498S heterozygous knock-in (C498S het KI) and p22phox cKO with SERCA2a-C498S heterozygous knock-in were subjected to sham surgery or transverse aortic constriction (TAC 3W). The mice were then analyzed for hypertrophic response and cardiac function by echocardiography. The heart LV tissues were collected for the indicated analyses. a, Representative echocardiographs from control, p22phox cKO, SERCA2a-C498S heterozygous knock-in and p22phox cKO with SERCA2a-C498S heterozygous knock-in mice after sham surgery or TAC 3W. b, LVEF (%) (sham: n = 6, 7, 9, 7; TAC: n = 7, 6, 7, 7). c, LVW/TL ratio (sham: n = 7, 5, 8, 5; TAC: n = 5, 7, 7, 7). d, Lung W/TL ratio (n = 7). e, The heart LV tissue of the mice that were subjected to sham or TAC 3W was analyzed by western blotting for protein levels of SERCA2a, with GAPDH as loading control. The figure shows representative immunoblots of SERCA2a with GAPDH as loading control from control and p22phox cKO mice with wild type or C498S mutant SERCA2a. f, Quantification of SERCA2a levels with respect to GAPDH in e (n = 6). g,h, Cardiomyocyte contractility was assessed in isolated cardiomyocytes from the indicated groups under NT solution and isoproterenol (1 µM) (Iso)-stimulated conditions. For each group, four mice and the specified number of cells per mouse were recorded and summarized. g, Representative cell shortening calculated as a percentage with electrical stimulation (3 s duration) indicated with arrows. h, Quantification graph of the percentage cardiomyocyte shortening in g (from left to right, n = 6, 6, 4, 6; n = 5, 5, 4, 6; n = 6, 4, 5, 11; n = 9, 7, 6, 5; n = 6, 6, 3, 3; n = 5, 6, 3, 4; n = 7, 8, 8, 5; n = 7, 7, 8, 8). The data points from cells of each mouse are represented by colored dots (black, blue, brown and black empty). All bar graphs represent the mean ± s.e. Statistical significance was determined with one-way ANOVA with Tukey test (b–d and f). Statistical analysis was conducted using the nested t-test (two tailed) (h) and hierarchical clustering analysis and the dendrogram is provided in the source data.

SERCA2a levels negatively correlate with increased Smurf1 and Hrd1 levels in human heart failure samples

The molecules associated with the degradation of SERCA2a identified in this study were evaluated in human LV samples from donor (healthy) and recipient (dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) or ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM)) samples. Immunostaining of human heart samples showed that the level of SERCA2a in the myocardium was significantly lower in failing hearts than in non-failing hearts (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Immunoblotting also showed that SERCA2a protein levels were downregulated in cardiomyopathic hearts compared with healthy hearts (Extended Data Fig. 7c,d). In addition, the levels of Smurf1 and Hrd1 were upregulated in cardiomyopathic hearts compared with control hearts (Extended Data Fig. 7e,f).

Discussion

Downregulation and inactivation of SERCA2a are major mechanisms of heart failure2. AAV-vector-mediated supplementation of SERCA2a is insufficient for improving cardiac dysfunction in patients23, suggesting the presence of complex posttranslational mechanisms regulating both the stability and activity of SERCA2a (refs. 4,24). Unexpectedly, our results show that endogenous p22phox protects SERCA2a from oxidation at Cys498, thereby preventing the downregulation of SERCA2a through ubiquitin proteasome-dependent mechanisms without affecting its ATPase activity. Interventions to prevent the oxidation of SERCA2a at Cys498 should prevent the downregulation of SERCA2a during cardiac stress, thereby maintaining cardiac function.

p22phox has four transmembrane helices and is located primarily on the ER membrane25. p22phox forms heterodimeric complexes with Nox isoforms and has an essential role in mediating the production of O2 and H2O2 (refs. 26,27). Studies of the effects of loss of p22phox function reported thus far have suggested that all known functions of p22phox are attributed to its ability to form complexes with Nox isoforms28. Our unbiased protein–protein interaction analyses showed, however, that p22phox can interact with many proteins, and SERCA2a, a transmembrane protein on the ER membrane, was identified as the most enriched binding partner of p22phox. Furthermore, as SERCA2a rescue alleviated the cardiac dysfunction in p22phox cKO mice, among the multiple p22phox-interacting proteins, SERCA2a appears to have a significant role in mediating the function of p22phox in the heart during pressure overload. Functional analyses have shown that p22phox protects SERCA2a from oxidation and stabilizes it against proteasome degradation. Although the current study highlights the importance of SERCA2a as a binding partner of p22phox during pressure overload, p22phox may also act as a chaperone to stabilize other transmembrane proteins on the ER, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of diseases through Nox-independent mechanisms. The tissue-specific p22phox KO mice we generated may be useful for identifying additional functionally relevant partners of p22phox in pathophysiological contexts.

p22phox physically interacted with the intracellular N domain of SERCA2a. As the inhibition of the physical interaction between p22phox and SERCA2a by the minigene harboring SERCA2a (334–666) promoted SERCA2a downregulation, mimicking the effect of the loss of p22phox function, we speculate that the physical interaction between p22phox and SERCA2a protects SERCA2a from degradation. As Cys498 is located in the region of SERCA2a that interacts with p22phox, we speculate that the interaction inhibits SERCA2a oxidation at Cys498 either by physically protecting Cys498 from oxidative stress or by recruiting molecules that inhibit oxidation of SERCA2a.

The SERCA2a N-domain is involved in nucleotide binding and enzyme activity29, and thus, we initially speculated that oxidation of Cys498, located in the middle of the N-domain, may affect the ATPase activity of SERCA2a. However, as the specific ATPase activity of SERCA2a in p22phox cKO mice does not appear to be decreased, oxidation of SERCA2a at Cys498 may not negatively affect the ATPase activity of SERCA2a. The property of SERCA2a oxidation at Cys498 is distinct from that at Cys674, another major cysteine oxidation site, where the activity of SERCA2a is positively affected by glutathionylation16. Our results suggest that SERCA2a oxidation at Cys498 promotes the interaction between SERCA2a and E3 ubiquitin ligases, including Smurf1 and Hrd1, which in turn promotes degradation of SERCA2a. The binding between E3 ligases and substrates is often regulated by posttranslational modification of the substrates, including phosphorylation, hydroxylation, acetylation, glycosylation and SUMOylation30,31. Our results show that the mutation of SERCA2a at Cys498 to serine negatively regulates the interaction between E3 ligases and SERCA2a in the presence of oxidative stress, thereby stimulating SERCA2a downregulation. Although further experimentation, including an in vitro direct protein–protein interaction assay with recombinant proteins, needs to be conducted, our results strongly suggest that cysteine oxidation of the substrate regulates the interaction between E3 ligases and the substrate. It has been shown that cysteine oxidation of either E3 ligases or scaffolding proteins affects ubiquitin proteasome protein degradation32,33. However, to our knowledge, the SERCA2a–E3 ligase interaction is unique in that cysteine oxidation on the substrate side controls the interaction.

Among the ubiquitin E3 ligases whose interaction with SERCA2a is increased by Cys498 oxidation, Hrd1 belongs to E3 ligases involved in the ERAD, the process mediating the proteasome-dependent degradation of ER proteins34. The ERAD machinery facilitates the efficient degradation of ER proteins in the presence of stress, and thus, the ERAD often has an adaptive and physiological role34. Thus, the fact that SERCA2a uses ERAD for its degradation and that it may negatively impact cardiac function during stress are interesting. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the functional significance of the Hrd1-mediated degradation of SERCA2a. Smurf1, another E3 ligase, also has an important role in mediating the degradation of SERCA2a (ref. 19). Whether Hrd1 and Smurf1 have redundant roles or mediate distinct stress-specific roles remains to be elucidated.

p22phox inhibits SERCA2a oxidation at Cys498. This was unexpected in that p22phox is involved in the Nox-mediated production of ROS25 and that the bulk level of oxidative stress in the heart homogenate in p22phox cKO mice was lower than in WT mice in the presence of pressure overload, consistent with the involvement of the Nox–p22phox complex in mediating oxidative stress during pressure overload. Interestingly, p22phox cKO mice showed increases in H2O2 in the ER, as evaluated with ER-targeted Hyper. Thus, p22phox protects SERCA2a from oxidative stress in the local compartment of the ER. We have shown previously that a lack of HAX-1, an ER/SR-associated protein, also increases oxidative stress in an ER-specific manner12. Thus, it is possible that ER-associated proteins have an intrinsic ability to suppress oxidative stress in the ER. We speculate that a lack of endogenous ER proteins, such as p22phox, induces ER stress and protein misfolding, which is often accompanied by oxidative stress35. It is also possible that p22phox may recruit antioxidants, such as thioredoxin-like molecules, to the proximity of the ER proteins to alleviate oxidation. Further investigation is required to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms.

The level of p22phox is increased in response to pressure overload and in some forms of cardiomyopathy. As genetic downregulation of p22phox exacerbates heart failure during pressure overload, upregulation of p22phox during pressure overload appears to be an adaptive mechanism. As the upregulation of p22phox is attenuated during the chronic phase of pressure overload and the upregulation is not observed in some forms of heart failure in humans, it is possible that the decline in p22phox may contribute to the inhibition of SERCA2a in the failing heart. It has been shown that p22phox is downregulated during hypoxia, in which downregulation of SERCA2a is also observed36. Currently, the molecular mechanisms through which expression of p22phox is controlled during stress are unknown. An investigation of the mechanisms controlling the level of p22phox may lead to the discovery of interventions allowing the stabilization of SERCA2a during heart failure.

Although the function of SERCA2a is consistently inhibited in human failing hearts, how SERCA2a is inhibited appears complex and context dependent. Whether or not SERCA2a is downregulated at the protein level is controversial37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. Furthermore, posttranslational modifications of SERCA2a also affect the activity of SERCA2a (refs. 4,24). Thus, to effectively restore the function of SERCA2a during heart failure, it is important to know how the level and the activity of SERCA2a are modified and identify the underlying mechanisms. Our results suggest that oxidation of SERCA2a at C498 increases proteasomal degradation of SERCA2a without inhibiting its ATPase activity. Thus, interventions to alleviate C498 oxidation and block Smurf1- or Hrd1-mediated degradation of SERCA2a may be of value in preventing SERCA2a downregulation during heart failure. Identification of other mechanisms regulating the activity of SERCA2a should further contribute to achieving more efficient rescue of SERCA2a downregulation during heart failure.

Some experimental limitations are noted. First, the downregulation of p22phox increased oxidation of SERCA2a at multiple cysteines. We focused on oxidation of Cys498 as it is oxidized most efficiently in vitro. The functional significance of SERCA2a oxidation at other cysteines needs to be clarified. Second, the molecular mechanism through which SERCA2a is oxidized at Cys498 remains unexplored. In particular, we are investigating the molecular mechanisms through which oxidative stress is regulated in the ER/SR and how p22phox interacts with these mechanisms. Third, during muscle contraction, mouse muscle cells typically release approximately 90% of their SR calcium stores, whereas human muscle cells release about 70% (ref. 45). Thus, the extent to which SERCA2a oxidation at Cys498 affects overall excitation–contraction (EC) coupling may differ between mice and humans. Fourth, regulation of oxidative stress in the heart is greatly affected by the genetic background. For example, oxidative stress is generally higher in C57BL/6N mice than in the C57BL/6J mice used in this study46. Thus, whether the p22phox-mediated local regulation of oxidative stress in the ER also differs among mouse strains remains to be tested.

In summary, our study has identified a mechanism by which oxidation and degradation of SERCA2a are mediated in the heart. The knowledge obtained from our study should be useful for designing molecular interventions to maintain the function of SERCA2a during cardiac stress and heart failure.

Methods

Human samples

The samples from explanted hearts used in this study (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 7c) were obtained from donors and patients who had undergone heart transplantation at Taipei Veterans General Hospital (VGH), Taiwan (Supplementary Tables 1 and 6). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Taipei VGH, and all specimens were from the residual sample bank, Taipei VGH. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) number is Taipei VGH IRB number 2018-05-006BC. The human tissue immunofluorescence data in Extended Data Fig. 7a,b was collected at Nara Medical University, Japan (Supplementary Table 5). The study protocols were approved by the Nara Medical University Ethics Committee, G107, and followed the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Written informed consent to collect tissue, conduct research and publish results anonymously was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians before the collection.

Mouse models

We generated p22phox knockout (p22phoxcKO) mice using lox-P and homologous recombination strategies (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). These mice were backcrossed into a C57BL/6J background. Cardiac-specific deletion of p22phox was obtained by crossing the mice with α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) promoter-driven heterozygous Cre mice (a gift from M.D. Schneider). Age- and sex-matched mice without α-MHC Cre recombinase were used as littermate control mice (control mice). The mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment within a temperature range of 21–23 °C with 12-h light–dark cycles. All experiments involving animals were approved by the Rutgers New Jersey Medical School’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of KI mice

We generated SERCA2a-C498A knock-in mice using Crispr-Cas9 genome editing in the C57BL/6J background. Genotype was confirmed using genomic DNA sequencing and PCR analyses. For PCR analysis, the genomic DNA isolated from mice were PCR amplified for the exon 12 of SERCA2a (ATP2a2) using forward primer: AAGGTCTAATGCGTATCTGAGCAG and reverse primer: CTGTTTGACACCAGGAGTCATGG. The PCR condition for these primers are:

Initial denaturation: 94 °C, 3 min (94 °C, 15 s; 68 °C, 60 s) × 35 cycles, and then 4 °C, hold. The Taq polymerase used is Advantage-2 catalog number 639202 from Clontech. A total of 5 μl of the PCR is digested with ScaI restriction enzyme. The Atp2a2-C498S mutated fragment generates two fragments at 210 bp and 132 bp whereas the Atp2a2 wild-type fragment is not cut with ScaI and gives a 342-bp fragment. The knock-in mice were crossed with wild-type C57BL/6J mice five times.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Cardiomyocytes isolated from mouse hearts were lysed with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCL, 0.5% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors). The lysates were incubated with recombinant Flag–p22phox (10 μg) and anti-Flag-M2 beads (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4 °C for 4 h. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, and Flag–p22phox binding proteins were eluted with 3×FLAG peptide (Sigma). The elutant was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Each gel lane was excised and in-gel trypsin digestion was performed. The resulting peptides were analyzed by LC–MS/MS on a Q Exactive MS instrument (Thermo Scientific)47,48. The MS/MS spectra were searched against a Swissprot rat database using the Sequest search engine on the Proteome Discoverer platform (V.2.3). All proteins and peptides were identified with a false discovery rate of less than 1%. The protein relative abundance was calculated based on spectrum counting.

TAC

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Rutgers University Animal Care and Use Committee. The TAC model was used to assess the effect of pressure overload on the development of heart failure in mice. The methods used to impose pressure overload in mice have been described49. Male mice at 8–12 weeks of age and fed a normal chow diet were randomly divided into two groups, pressure overload with TAC or sham operation. We focused on male mice in this study. Age- and sex-matched mice were used for the control group. The background of all mice was C57BL/6J. Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60–70 mg kg−1) and mechanically ventilated. The left side of the chest was opened at the second intercostal space. Aortic constriction was performed by ligation of the transverse thoracic aorta between the innominate artery and left common carotid artery with a 27-gauge needle using a 7-0 prolene suture. Sham operation was performed without constricting the aorta. The number of animals used is described in each figure legend. There were no unexpected adverse events during the procedures. All operations and analyses were performed in a blinded manner with regard to the genotype of mice. To measure the aortic pressure gradient across the constriction, high-fidelity micromanometer catheters (1.4 French; Millar Instruments) were used.

Dobutamine stress test

Mice were anesthetized using 12 μl g−1 body weight of 2.5% avertin (Sigma-Aldrich) and prepared for cardiac catheterization50. The dobutamine infusion was administered via jugular vein cannulation with a PE-10 tube attached to an infusion pump (catalog number BTPE-10). Dobutamine infusion (10 ng µl−1) was set up for ramp infusion in a step-to-step format with an increase of 10 µl min−1 for each step, for 3 steps. The data were acquired using LabChartPro 7 software, and the ejection fraction was analyzed and expressed relative to wild-type mice at dobutamine infusion rates of 0, 4, 8 and 12 ng g−1 min−1.

Echocardiography

Mice were anesthetized using 12 μl g−1 body weight of 2.5% avertin (Sigma-Aldrich), and echocardiography was performed using ultrasound (Visualsonics Vevo 770). A 30-MHz linear ultrasound transducer was used. Two-dimensional guided M-mode measurements of LV internal diameter were obtained from at least three beats and then averaged. LV end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD) was measured at the time of the apparent maximal LV diastolic dimension, and LV end-systolic dimension (LVESD) was measured at the time of the most anterior systolic excursion of the posterior wall. LVEF was calculated as follows: ejection fraction = ((LVEDD)3 − (LVESD)3)/(LVEDD)3 × 100. For all mouse experiments, data analysis was conducted in a blinded manner.

Recombinant proteins

The bacterial expression vector for glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused p22phox-full-length was generated by insertion of mouse p22phox cDNA amplified by PCR into the pCold-GST-vector. The BL21 Escherichia coli strain was transformed with pCold-GST-p22phox-full length. The E. coli was cultured in 3 ml LB medium containing ampicillin overnight at 37 °C, and then transferred to 250 mL LB medium containing ampicillin. Protein expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropylthio-β-galactoside. After overnight culture at 15 °C, the E. coli were lysed in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM DTT in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) with sonication. The lysate was incubated with 0.5 ml glutathione-sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 4 °C. The sepharose was washed 3 times with 5 ml lysis buffer and then suspended with 1 ml cleavage buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 7); 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM DTT). Recombinant SERCA2a protein was purchased from Lifespan Biosciences (G27566).

Adenovirus constructs

Recombinant adenovirus vectors for overexpression were constructed, propagated and titered as previously described51. Briefly, pBHGlox∆E1,3 Cre plasmid (Microbix) was co-transfected with pDC316 shuttle vector (Microbix) harboring the gene of interest into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). An in-house-generated adenovirus harboring β-galactosidase (Ad–LacZ) was used as a control.

Primary culture of neonatal rat CMs

Primary cultures of CMs were prepared from 1-day-old Charles River Laboratories (Crl)/Wistar Institute (WI) BR-Wistar rats (both sexes) (Harlan Laboratories) and maintained in culture. A cardiomyocyte-rich fraction was obtained by centrifugation through a discontinuous Percoll gradient. CMs were cultured in complete medium containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F-12 supplemented with 5% horse serum, 4 mg ml−1 transferrin, 0.7 ng ml−1 sodium selenite, 2 g l−1 bovine serum albumin (fraction V), 3 mM pyruvate, 15 mM Hepes (pH 7.1), 100 mM ascorbate, 100 mg l−1 ampicillin, 5 mg l−1 linoleic acid and 100 mM 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (Sigma-Aldrich). Culture dishes were coated with 0.3% gelatin.

Isolation and culture of adult mouse CMs

Isolation and culture of adult mouse CMs were conducted according to the protocol previously described52.

Tissue-released H2O2 measurement

The tissue H2O2 was measured with the Amplex Red Hydrogen Peroxide/peroxidase Assay Kit (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen reference A22188). The heart tissue was freshly collected and sectioned on a matrix block with PBS-wetted fresh blades. Each section was immediately submerged into 200 µl of Amplex Red reagent (100 µM) and placed in a 24-well plate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min (protected from light). After incubation, 2 × 100 µl of the incubated reagent from the tissue section was taken for fluorescence readings measured at 530 nm excitation and 590 nm emission. The amount of H2O2 released from the tissue sections was estimated against known H2O2 standards, and the values were normalized with the weight of the section in mg. The values obtained from all the sections of one heart were averaged to represent one data point on the graph.

ER-HyPer and Mito-HyPer confocal imaging

Adenoviruses encoding the HyPer fluorescence H2O2 sensor with endoplasmic reticulum localization signal or mitochondria localization signal were expressed in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes as described53. Following transfection with control siRNA and p22phox siRNA, the cells were imaged live using confocal microscopy with excitation at 457 nm and emission at 514 nm. The ratiometric (514 nm/457 nm) images were generated with a 2-fold threshold. The scale of the ratiometric image ranges from 0 (low H2O2) to 2-fold (high H2O2), with default color indicators.

SERCA2a ATPase assays

The cardiac SR fraction was isolated as previously described54. Briefly, heart tissue is perfused with 0.9% saline containing 500 μM EDTA (the buffer should not contain phosphates). The fresh heart tissue or frozen heart tissue was homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer in 0.25 M sucrose (with protease inhibitors). The lysate is centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant is centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant is centrifuged at 30,000 g for 1.5 h at 4 °C. The pellet fraction is the SR fraction that is estimated for the protein amount and used for ATPase assay after dissolving the pellet in 0.25 M sucrose (with protease inhibitors).

SR-associated SERCA2a ATPase activity was determined using a colorimetric method55. The production of phosphate that is proportional to the SERCA activity was measured using an ATPase activity assay kit (MAK113, Sigma-Aldrich), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, SR protein (1 µg) after SR fractionation as above was incubated with calcium chloride (2 µM) with and without thapsigargin (75 µM) along with 1 mM ATP and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of the malachite green reagent provided in the kit, which forms a stable dark green color with free phosphate released by the reaction that can be colorimetrically measured at 620 nm. The SERCA2a ATPase activity of the SR fractions was calculated as the difference between values without and with thapsigargin. This value was again normalized to the SERCA2a levels in the respective SR fractions as determined by western blotting, and the relative activity was analyzed with respect to the wild-type SR fraction.

Antibodies and reagents

The primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: p22phox (Abcam: ab191512 and Invitrogen: PA5-75653), Flag (Sigma-Aldrich:1804), GAPDH (Cell Signaling: 2118), α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich: 6199), SERCA2a (Cell Signaling: 4388S for western blot, Abcam: 150435 for immunoprecipitation), T-PLN (Cell Signaling: 14562), phospho-PLN (Ser16/17) (Cell Signaling: 8496), Smurf1 (Sigma-Aldrich: WH0057154M1), Hrd1 (Proteintech: 67488-1), PSMA3 (Cell Signaling: 12446S for western blotting and Proteintech: 11887-1 for immunofluorescence), NOX2/gp91phox (abcam: 129068) and NOX4 (Proteintech: 14347-1-AP). The secondary antibodies used in this study were as follows: anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling: 7074) and anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling: 7076).

The siRNAs used in this study are as follows: rat p22phox siRNA (identifier (ID): s236253), rat Smurf1 siRNA (ID: s234756), rat Hrd1 siRNA (ID: s167862) rat Psma3 siRNA (ID: s131972), rat Nox4 siRNA(ID: 190243/190244/190245 and 55016) and rat ATP2A2 (SERCA2a) siRNA (ID: 160790) (Silencer Select siRNA from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Invitrogen). The Transfection reagent used is lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen: 13778075).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse hearts using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Total RNA was converted to cDNA using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara). The following oligonucleotide primers were used in this study: p22phox, sense (5′- GTATTTCGGCGCCTACTCTATC-3′) and antisense (5′-GTCAGGTACTTCTGTCCACATC-3′); 18S, sense (5′-AGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTACACA-3′) and antisense (5′-CGATCCGAGGGCCTCACTA-3′); SERCA2a, sense (5′-CATCAGTATGACGGGCTTGTAG-3′) and antisense (5′-CTCGGTAGCTTCTCCAACTTTC-3′); NCX, sense (5′-AGTCTCCCACCCAATGTTTC-3′) and antisense (5′-CTCCTGTTTCTGCCTCTGTATC-3′); PLN, sense (5′-TATCAGGAGAGCCTCCACTATT-3′) and antisense (5′-CAGATCAGCAGCAGACATATCA-3′); and RyR, sense (5′-CTTCTGTGAGGACACCATCTTT-3′) and antisense (5′-CCTCTCCTTCTCACTCTCTTCT-3′). Data were normalized with the RT-PCR result for GAPDH. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on the CFX 96 RealTime PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The Ct value determined using CFX Manager Software (version 2.0, Bio-Rad) for all samples was normalized to GAPDH, and the relative fold change was computed by the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method.

Immunoblot analysis

Heart homogenates and CM lysates were prepared in RIPA lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Equal amounts of samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The antibodies used were as described above. The regions containing proteins were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent, GE Healthcare). Densitometric analyses were performed with the ImageJ software.

Histological analysis

The heart tissue was washed with PBS, fixed with 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and cut into 10-µm-thick sections. Serial sections of the heart were stained with wheat germ agglutinin for analysis of the CM CSA and Picrosirius Red for analysis of myocardial fibrosis. CSA was obtained by tracing the outlines of 100–200 random CMs with a clear nuclear image from the LV. These analyses were performed in a blinded manner using a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse E800, Nikon) and ImageJ software (NIH).

Cardiomyocyte isolation

Left ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated from mouse hearts as previously described56. Briefly, mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane before hearts were removed and perfused in Langendorff fashion at 37 °C with Ca2+-free Tyrode’s solution (in mM: 136 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 0.2 mg ml−1 Liberase TL Research Grade (number 05401020001; Sigma-Aldrich, Roche) for 10–12 min. The enzyme solution was then washed out, and the hearts were transferred from the Langendorff apparatus to petri dishes. Left ventricles were gently teased apart with forceps. The Ca2+ concentration was gradually increased to 1.0 mM. Finally, the cell suspension was filtered through a 200-μm nylon mesh. Myocytes were stored at room temperature and used within 8 h after isolation for cell shortening assays or intracellular Ca2+ transient measurements.

Cardiomyocyte contraction or single-cell shortening assay

Adult mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated via retrograde Langendorff perfusion using enzymatic digestion as described above. Myocytes were placed in a heated chamber (37 °C) and superfused with normal Tyrode’s (NT) solution on an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE200) and were subjected to 1-Hz field-pacing using a stimulator (Grass Instruments). Changes in cell length were monitored by a video-based edge detection system (Crescent Electronics). Contraction traces were recorded and analyzed using commercially available pCLAMP10 software (Molecular Devices). Single-cell shortening was calculated as a percentage of shortening from the baseline cell length in the relaxed state. A minimum of five cells per mouse were recorded, and the median value of at least three consecutive contractions per cell was used for the analysis.

Intracellular Ca2+ transient measurement

This method has been described previously56. In brief, ventricular myocytes were incubated with 4 μm Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 40 min. After washing and de-esterification (30 min), the cells were transferred to a heated chamber (37 °C) on a Nikon Eclipse TE200 inverted microscope (Nikon) with a Fluor ×40 oil objective lens (numerical aperture 1.3). The fluorescence (excitation/emission: 485/530 nm) was recorded with a spatial resolution of 500 × 400 pixels at 50 frames per second by an iXon Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) camera (Andor Technology) operated with Imaging Workbench software (INDEC BioSystems). Ca2+ fluorescence intensity was expressed as the ratio F/F0 (fluorescence (F) over the baseline diastolic fluorescence (F0)). The amplitude of the 10 mmol l−1 caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient was used as a measure of total SR Ca2+ content. Fractional SR Ca2+ release was calculated by dividing the height of the last twitch transient by the height of the caffeine transient. The tau values were obtained by using the curve-fitting function (nonlinear exponential decay 1 function) of the Origin 2025 software after carefully selecting the decay phase fluorescence and time values of individual peaks.

PLA

PLA technology allows the detection of interactions between endogenous proteins, based on the detection of protein proximity. PLA was carried out with Duolink In Situ Detection Reagents (Sigma-Aldrich). In brief, myocytes were washed, blocked and then incubated with anti-p22phox and anti-SERCA2a primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. After they were washed, the myocytes were incubated with Duolink PLA MINUS and PLUS probes for 1 h at 37 °C. A Duolink in situ detection kit was used for ligation and amplification. DAPI was used to stain the nucleus. The images were captured using a microscope, and red spots indicate the interaction between p22phox and SERCA2a.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

NRCMs were plated on 1% gelatin-coated glass-bottom 35-mm dishes. The cells were transfected with control siRNA or p22phox siRNA for 48 h. After transfection, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The fixed cells were further washed with PBS three times, and the cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked with 5% BSA in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies (SERCA2a, Hrd1 and PSMA3 at dilution 1:200) were diluted in 5% BSA–0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After three PBS washes, the respective fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:1,000) were added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (in the dark). The cells were washed three times with PBS and mounted with Fluoromount-G containing DAPI. Slides were imaged using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope fitted with a ×63 oil-immersion lens, and images were analyzed with Imaris software (version 10.0.1).

Immunoprecipitation

CMs were lysed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton-X 100, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were incubated with anti-Flag agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for at least 2 h at 4 °C. After immunoprecipitation, the samples were washed with lysis buffer five times and eluted with 2× SDS sample buffer.