Abstract

Rare particle enrichment plays a pivotal role in advancing numerous scientific research areas and industrial processes. Traditional enrichment methods encounter obstacles such as low efficiency, high cost, and complexity. Acoustic focusing, optical fiber detection, and electrical manipulation have shown potential in microfluidics for particle manipulation and analysis. This study pioneers the integration of the acoustic, optical, and electrical units to overcome the traditional limitations. The cooperative dynamics of acoustic and flow focusing are explored. The optical fibers with an enhanced detection algorithm greatly boost optical detection sensitivity. Furthermore, the droplet charging to enhance the tip charging phenomenon is complemented and validated. The detection and sorting accuracy of enriching large-size H22 cells reached 99.8% and 99.3%, respectively, with the target cell concentration increased by nearly 86-fold. Our work significantly enhances detection sensitivity and particle manipulation accuracy, ultimately offering a robust and reliable solution for generating droplets to enrich rare particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rare particles enrichment is an important part of various scientific and industrial applications, ranging from biosciences to environmental monitoring1,2,3. In biomedical diagnostics, the enrichment of circulating tumor cells is critical for early cancer detection4,5,6. On the other hand, the enrichment of microplastic particles in the oceans allows for better analysis of their distribution and sources to develop relevant management strategies7,8,9. Traditional methods for particle enrichment face challenges such as low efficiency, high cost, and complex procedures10,11. For example, microfiltration and inertial separation are considered the most basic techniques, but these methods only separate cells with different sizes and may influence the viability with ordinary accuracy12,13,14. Centrifugation is one of the most widely used inertial separation methods due to its simplicity and ability to separate particles based on density differences. However, this method often requires significant processing time, may cause shear-induced damage to delicate particles or cells, and is not suitable for continuous processing15,16. Magnetic separation can obtain higher enrichment accuracy by bonding magnetic labels with target cells, but the high reagents cost and the complex operation of bonding and removing the labels are undesirable17,18,19,20. In response to these challenges, the advent of microfluidic technology offers a transformative solution. Compared to the traditional methods, the microfluidic approach provides continuous processing, reduced equipment size, lower risk of particle damage, and the ability to handle particles or cells with minimal differences in size or density21,22, showing great potential in various fields23,24,25.

Acoustic, optical, and electrical methods have garnered significant attention for realizing microfluidics26,27. For example, surface acoustic waves (SAW) play a vital role in particle washing and manipulation28,29. Acoustic-based microfluidic chips can precisely align particles into a single streamline30,31,32,33,34. Further, there have also been many studies focused on enhancing manipulation effects for better cellular imaging or sorting using surface acoustic waves35,36,37,38. For instance, Ning et al.39 developed a microfluidic chip with a serpentine channel enabling high-throughput cell separation using SAW, demonstrating efficient particle focusing and separation. Similarly, Collins et al.40 utilized highly focused high-frequency traveling SAW for rapid single-particle sorting, achieving high-resolution manipulation at the microscale. The reliability of acoustic focusing and flow focusing has been verified41, but there is still a lack of research on their synergy and impacts on subsequent detection and sorting functions. Optical detection is the central step for sorting particles. There are two main methods for optical detection on microfluidic chips: free-space detection and optofluidic detection26. The former uses a conventional optical configuration, where the detection units are all separated from the chip platform, and the lasers propagate through the air before and after interacting with the chip. The latter simplifies and miniaturizes optical detection by integrating micro-optical components such as lenses, prisms, and optical fibers42,43,44,45. Here optical fibers are widely used due to their low cost, small size, and easy integration46. Gupta et al.47 developed a microfluidic platform integrating flow cytometry principles to accomplish cell analysis using optical fibers to detect multiple-path optical signals. Zhao et al.48 integrated micro-lenses into the end of optical fibers to improve the detection sensitivity. Optical fibers can also be modified in various ways to enhance detection performance49. The tapered optical fibers, obtained by heating and stretching, can efficiently focus the laser beam and correspond to individual cells or tiny particles50. A similar effect can be achieved by reducing the fiber diameter through erosion, offering a simpler manufacturing process51. However, the modification remains potential processing errors and failure odds because the fiber dimensions are difficult to control accurately. As a vital nexus between particle focusing and sorting, the optical detection structure requires more stability and reliability. The precise enrichment sorting is usually carried out at the droplet microscale52,53, and a well-designed electrode structure is competent for droplet manipulation54,55. Tirapu-Azpiroz et al.56 placed the inclined electrodes and rectangular grounded electrodes parallel to the top and bottom of the microfluidic channel, reducing particle position dependence and micromachining-complexity with a dielectrophoresis-based modular electrode design. Zhang et al.57 introduced a non-dielectrophoresis (nDEP) sorting device with 3D electrodes and a fluid structure integrated with silver-polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) composite materials. The two-layer electrode forms a non-uniform electric field, which is convenient for capturing target cells. Luo et al.58 demonstrated conductive agarose gel electrodes in microfluidic dielectrophoretic sorting, with PDMS bonded to a glass surface and gold traces for electrical connections. Yao et al.59 used copper wire as the charging electrode and phosphate-buffered saline as the deflection electrodes for electrostatic droplet charging and sorting. All these electrodes achieve accurate sorting, but most are demanding for the manufacturing process, leading to higher production failure rates, personnel skill requirements, and costs. Another common problem is that electrolyte solutions or gels inevitably undergo electrolytic reactions. Altogether, many researchers have focused on innovative breakthroughs in a single technology, such as acoustic, optical, or electronic manipulation, but individual technology brings to the overall system is often limited. While some previous studies have integrated acoustic methods with optical detection60 or electrical sensing61,62, the interactions among multiple technology units have not been thoroughly explored.

In this study, we have meticulously designed each unit (acoustic, optical, and electrical) to not only function effectively on their own but also to complement and enhance one another, establishing an interdependent system. The cooperative relationship of acoustic and flow focusing is explored, and an innovative manufacturing process and algorithm that integrates optical fibers and laser windows into the microfluidic chip design are presented, increasing the optical detection sensitivity. Additionally, we use low-temperature phase change alloys to cast deflector electrodes. The proposed system has great improvements in both chip design and algorithm, offering a robust solution for high-accuracy particle manipulation and enrichment.

Methods

Particle detection and sorting

The working schematic of the chip is illustrated in Fig. S24. Particles focused by the sheath fluid and SAW, flow through the optical detection part. When the particles pass through, pulse signals are triggered. These signals cause the charging electrodes to charge the droplets. The droplets that encapsulate the target particles are then charged. This process enables the droplets to be sorted. A low-temperature phase-change metal material was used to fabricate barrier structures for the laser window. By incorporating barrier structures, the laser beam is partially blocked, resulting in a narrower laser spot width, which enhances detection sensitivity. The barrier structures reduce the laser spot width from 60 μm to 20 μm. As particles pass through the narrower laser spot, the percentage of spot area blocked increases, resulting in a lager change in light intensity detected by the receiver. The amplification of this signal change effectively increases the sensitivity of the detection.

Chip manufacturing process

The chip fabrication process begins with the preparation of PDMS microfluidic channels using soft lithography63. Next, SAW electrodes are created through the lift-off technique64. The electron-beam method is then used to prepare deflection electrode pins65. Finally, the PDMS microfluidic channels, SAW electrodes, and deflection electrode pins are integrated. The integration of the optical fibers and the casting of the deflection electrodes and laser windows are also finalized in this step. More details for the chip fabrication processes are provided in Supplementary Information Section 1.

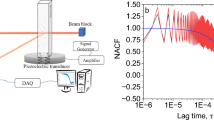

Microfluidic test system

Figure S25a provides the physical diagram of the chip completed using the above process. As illustrated in Fig. S25b, our microfluidic test system comprises a microscope-based chip experiment platform and various devices. Figure S25c shows the microscopic imaging of the optical detection part on the microfluidic channel template. Figure S25d shows the laser window molded by the described casting method for single-color detection. Figure S25e shows the multicolor detection structure considered in our design and demonstrates the narrowing effect on the laser beam.

Real-time optical signal processing

The optical signal was first analyzed with a silicon photodiode to be converted into an analog voltage signal. The data acquisition card acquires signals at 512,000 Hz. A higher sampling frequency brings a higher upper limit of detection speed and ensures that the signal will not be distorted or missed.

Analog voltage signals are analyzed in Python, which consists of the following steps: (1) When a particle passes through the detection area, a signal pulse is generated. Q is the number of sampling points of the rising edge in the signal pulse and is set based on the data volume of the queue.

U1 is the dispersed-phase flow rate, h and w are the height and width dimensions of the microfluidic channel, Do is the width of the optical detection window, and fs indicates the sampling frequency of the data acquisition. (2) In the first step, a delay of half a pulse length is generated and the data in the queue is differenced, summed, and then taken to its absolute value. The detailed calculation formula is as follows:

We call this process as difference, summation, and absolute valorization (DSA) operation. Rk indicates the DSA-processed data value, and Xk denotes the elements in the queue. (3) After analyzing the bottom noise N, the detection threshold is determined as 3N. The processed real-time signal R and the threshold are compared to trigger the pulse charging. The detailed flow of the algorithm is shown in Fig. S26.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results and Discussion

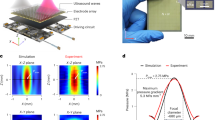

Acoustic and flow focusing technique

For acoustic focusing, the SAW fork finger electrodes operating at specific frequencies can cause substrate vibration, which generates a stabilized SAW standing wave. As shown in Fig. 1a, the sound pressure is inversely correlated with the speed of the molecules motion: when the molecules vibrate at zero speed (at the standing wave crests and bellies), the sound pressure is zero; when the molecules are at their fastest speed at the wave knots, the sound pressure reaches its maximum value. The acoustic contrast factor Φ determines whether particles will be attracted to pressure nodes or antinodes in an acoustic field. Particles with a positive contrast factor are attracted to pressure nodes, while those with a negative contrast factor move toward pressure antinodes66,67. In our study, all particles involved in 1X phosphate-buffered saline presented positive acoustic contrast factors, moving towards the pressure node in both simulations and experiments. Previous studies disclosed that Polystyrene (PS) microspheres and most living mammalian cells usually show positive acoustic contrast factors in aqueous fluids, which is consistent with our findings68,69. The calculation of the acoustic contrast factors is provided in Section 2 of the Supplementary Information.

a Sound field simulation of the microfluidic cross-section. b Correlation between sound pressure and substrate amplitude in the width direction. c SAW focusing effect from the top view. d Particle distribution simulation in microfluidic cross-section under the influence of SAW and flow focusing, the warmer particle colors represent areas with higher particle overlapping density. More information on this simulation study is provided in the Supplementary Information Section 3.

Figure 1b, c visualize the substrate amplitude and sound pressure from the top view and the cross-section view. This simulation clearly shows the sites with zero sound pressure, where the particles end up. Furthermore, in the simulation of particle motion (Fig. 1d), we find that acoustic focusing produces edge effects, the same as other studies70. The edge effect, also known as the corner effect, is primarily caused by low flow rates and acoustic wave leakage at the microfluidic channel walls and corners71,72. Flow focusing is designed to eliminate the negative impacts of the edge effects. The sample stream is wrapped by the sheath fluid in a laminar state, reducing the particles at the corners of the microfluidic channel. Some studies on SAW-based particle focusing using standing waves report no observable edge or corner effects73. We hypothesize that such effects may depend on various factors including microchannel design, acoustic wave parameters, and fluid properties. Related research supports this hypothesis, showing that viscoelastic fluids combined with cylindrical channels can eliminate this effect74. However, rectangular channels led to acoustic wave leakage at the channel walls and corners, causing the formation of standing waves and resulting in non-uniform acoustic radiation forces. The particles at the edges and corners not to experience the normal acoustic radiation forces, leading to their entrapment in these regions. Thus, the edge effect arises. This intriguing phenomenon warrants further exploration in future research: delving deeper into the influence of these factors to better understand the conditions under which edge and corner effects arise.

Our practical experiment results are consistent with the simulation in focusing, and the acoustic and flow focusing makes the particles congregate on the zero sound field plane. In the SAW and Flow Focusing images of Fig. 2a, due to the fixed focal position of the microscope, some particles appear clear while others appear blurry. This indicates that there are still particles present on the upper and lower sides of the microchannel. Two more sheath fluid streams can be introduced at the upper and lower sides, creating a four-way focusing, and this method is often used to concentrate cells in flow cytometry75,76. As seen in the lateral view (Fig. 2b), this method leads to good results.

a Particle distribution in the chip microfluidic channel from top view. b Particle distribution in the chip microfluidic channel from lateral view. The images taken 0.2 milliseconds apart are subtracted to highlight the motion of the particles. The effect of flow rate on focusing is provided in Supplementary Information Section 6.1.

To enhance reproducibility and system robustness, we conducted a series of parametric studies. The ratio between the sheath stream and the sample stream, as well as the power and frequency of the SAW, significantly influence the particle focusing.

As shown in Fig. 3a, the microfluidic channel with an actual width of 60 µm, is divided into 20 scales to measure the particle distribution. In the experiment of each parameter part (fan-shaped areas), the deviation degree of the particles to the neutral axis is arranged in a clockwise order, from large to small. The bar height indicates the percentage of particles at each deviation value. In Fig. 3b, our results demonstrated that particle focusing improves as the sheath flow ratio increases. The difference between 3:1 and 4:1 ratio is minor, with over 50% of particles focused on the centerline. A further finding is that edge effects are mitigated at ratios above 1:2, suggesting that the 1:1 or 2:1 ratio is superior for synergizing with acoustic focusing. From Fig. 3c, it is clear that the SAW power influences the width of the focusing area. Initially, increased SAW power correlates with better results. Until the power reaches 1 dBm, the particles are focused to the 6 μm center region with nearly 90% percentage. This is the upper limit of the focusing effect we achieve, and it no longer gets better with higher power. As illustrated in Fig. 3d, another interesting finding is that the particle distribution shows two different appearances when the SAW frequency changes. If the SAW frequency is between 19.70 MHz and 19.90 MHz, the particles only show slight upward and downward deviation. With further frequency variations, the particles begin to offset from the centerline and eventually turn to a mess state. We compare related studies on SAW devices to explain this phenomenon. Koigerov et al.77 found that the SAW power loss is lowest at the optimal resonant frequency. This means that our small adjustments of the frequency may weaken the SAW power and make it more difficult to gather on the centerline. Another study showed that frequency changes affect acoustic force generation due to the positional offset of peaks and nodes of the fundamental standing wave, likely the same reason for the deviations in our experiments78. For the mess status, a popular explanation is that these erroneous frequencies do not effectively cause fundamental resonance70. The confusion or absence of the standing waves leads to the device failing. Standard SAW devices typically operate within the “3 dB” bandwidth. Our simulations and experiments have consistently confirmed this operating range. Notably, through our frequency experimentation, the optimal operating frequency at 19.8 MHz is pinpointed. This finding underscores the precision and efficacy of our approach in optimizing the performance of SAW devices. The relationships between standing wave formation, input voltages, frequencies, and microchannel geometry with the sound field are provided in Section 4 of the Supplementary Information.

a Quantitative rule of the particle deviation level in the microfluidic channel. b Impact of different sheath and medullary fluid flow rate ratios on particles focusing without acoustic focusing, and the total flow rate in the control focusing flow channel is 10 μL/min. c Impact of different SAW powers with the frequency of 19.80 MHz and the flow rate ratio is 1:1. d Impact of different SAW frequencies on particles focusing with the SAW power of 0 dBm and the flow rate ratio is 1:1.

Surface acoustic wave devices are often used to simply drive particles or fluids to a target direction in a high flow rate60, while acoustic tweezers in previous studies greatly achieved independent and reconfigurable manipulation of particles and cells in the resting state79,80. The advantages of both are taken into account in our experiments. By fine-tuning the resonance frequency, our synergistic focusing approach makes it possible to manipulate micrometer-scale motion at high flow rates. Moreover, the parametric study tests the extreme operating range of the flow focusing and SAW device, determining the optimal parametric conditions for enhanced performance. This synergistic integration offers benefits over simple hydrodynamic focusing or inertial ordering. By utilizing a lower sheath fluid flow rate, our method significantly reduces the stringent requirements for optical detection and electrical sorting, such as the need for higher frequency sensors and the complications arising from unstable droplet generation. Combining acoustic waves with hydrodynamic focusing provides a more stable focusing effect, as evidenced by clearer detection signals, which illustrates the effectiveness of acoustic waves in improving focusing performance. The effects of synergistic focusing are also discussed further in the next section.

Microspheres optical detection with focusing and laser window

In the previous section, the synergistic effects of acoustic and flow focusing yields promising results. Here, we present the focusing effect on the optical detection unit. The acoustic and flow focusing significantly enhances the optical detection due to the particles being focused on the center plane. This reduces the particle overlap, standardizing the distance between the particles and the fiber. The result in Fig. 4a provides evidence for this point. After applying acoustic and flow focusing, the detected particulate pulse signals become more uniform, achieving the highest signal-to-noise ratio, with no target signals lost in noise. As shown in Fig. 4b, we integrate the optical fiber into the microfluidic chip, effectively capturing particles using fiber optics detection, and producing similar results to others47. For the selection of the laser window dimensions, the results indicate that the 20 μm laser window further optimizes the acquired signals (Fig. 4biii), the 30 μm laser window does not improve sensitivity (Fig. 4bii), and the 10 μm laser window reduces the direct current (DC) component of the signal, leading to increased signal noise (Fig. 4biv). Figure 4c captures the moment a particle passes through the detection area and is illuminated by the laser. Compared to previous studies, Kumar et al. and Fu et al.50,51 achieved higher accuracy using tapered fibers or reduced-diameter fibers. We match their accuracy while avoiding the detections missing caused by the smaller detection point in the optical path due to fiber modification. Overall, our method was the one that obtained the most robust results.

a Effect of SAW and flow focusing on signals. bi The detection unit and its signals without the laser window. bii The detection unit and its signals with a 30 μm laser window. biii The detection unit and its signals with a 20 μm laser window. biv The detection unit and its signals with a 10 μm laser window. ci Microspheres are detected in the laser detection area. cii Microspheres passed through the laser detection area. The light-colored areas in (a, c) represent the noise band and the dark-colored areas represent the signal band. The calculated signal-to-noise ratio values are listed on the right side of each figure.

A video of forward laser particle detection is provided in the Supplementary Materials (see Video 1 in Supplementary Materials).

DSA algorithm in real-time signals

Unlike the enclosed optical path structure in flow cytometry, our microfluidic platform operates as a real-time imaging system. Natural light on the microfluidic platform inevitably introduces noise interference to the optical detection signals. In Fig. 5a, our experimental results show that the change in the lens aperture interferes with the DC component of the detection signal. This interference complicates the determination of the detection threshold, affecting subsequent sorting and analysis. Real-time first-order differencing is a traditional method for removing the DC component and sharpening the pulse peaks of the signals, as shown in Fig. 5b. This autocorrelation noise reduction method is commonly used, but it does not achieve our desired result at high sampling rates. The other real-time pulse detection methods using dynamic windows to calculate the standard deviation of the signal over a sequence of periods81,82, yield great processing results with minimal delays (a few times the length of the pulse). Our DSA method, as illustrated in Fig. 5c, controls shorter delays (half pulse length) in the pulse, effectively eliminating the undesirable changes of the DC component, and retaining the pulse peak features closely approximating the original signal. This simple method produces more excellent results, as detailed in Fig. 5d–f.

a Original signals with unstable DC components. b Differential processed signals. c DSA algorithm processed signals. d Original signal pulse segments. e Differential processed pulse segments. f DSA processed pulse segments. DSA segments have a phase difference of half a pulse length from the original signal segment on the time series. The dark-colored regions in (d–f) represent the triggering window for this signal, and the light-colored regions represent the non-triggering window for this signal.

Electrostatic induction for droplet charging and deflection

At the droplet generation area, the dispersed-phase fluid will be sheared into a tip by the continuous-phase fluid. As an excellent conductor of electricity, the continuous-phase fluid tends to converge surface electric charges at the tip site. Based on the electrostatic induction, the charging electrodes are placed at the droplet generation area to enhance this charge aggregation phenomenon. The multi-physics field coupled simulation model is developed to analyze the above droplet generation and charging process. Figure 6a confirms that the polarization and ionization have no interference with the surface electric charge movement, as this electric field is negligible. Similarly, the supplementary acoustic field force model in Fig. 6b represents that the acoustic field force does not cause serious interference with droplet generation. The simulation details on the characterization of droplet generation under acoustic-electric field coupling are provided in Section 5 of the Supplementary Information. Figure 6c, d visualize the distribution of electric charges on the surface of the dispersed-phase using the current density model, providing crucial theoretical evidence for understanding the described charging process. These results support the feasibility of using this method for droplet charging. The influence of dielectric constants on the electric charge distribution of the droplet surface is described in Fig. 6d, e. The results show that the larger dielectric constants (whether it is continuous or dispersed phase), lead to more electric charges accumulating.

a Polarization and ionization of the dispersed phase in the electric field. b Acoustic field pressure model of the droplet generation process. c Electric charges density in the centerline of the microfluidic channel during droplet generation and positively charged. d Current density model of the droplet generation process. e Effect of dispersed-phase dielectric constant on droplet electric charges, the dielectric constant ranges from 80 to 60 in steps of 2. f Effect of continuous-phase dielectric constant on droplet electric charges, the dielectric constant ranges from 4.2 to 1.8 in steps of 0.2.

In conjunction with our simulation of droplet generation and charging processes, we verified the practical results using continuous-phase of three different viscosities, as shown in Fig. 7a–c. Specifically, Fig. 7a demonstrates droplet generation in the jetting mode, Fig. 7b shows the dripping mode, and Fig. 7c illustrates the squeezing mode. Our experiments have reconfirmed that under jetting conditions, the droplet frequency and size often fluctuate, resulting in polydisperse droplets83,84. The details are provided in Supplementary Information Section 7. The results demonstrate that the droplet diameter decreases as the viscosity of the continuous-phase increases. Another finding is that as the flow rate increases, the droplet diameter decreases and the frequency increases (Fig. 7d–i). Planned comparisons of three continuous-phases reveal that silicone oil achieves more stable droplet generation at higher flow rates, meeting our needs. These conclusions align well with previous studies85,86,87 and are supported by more extensive parametric studies.

Real-time images of (a) vegetable oil, (b) silicone oil, and (c) mineral oil generating droplets at the same flow rate ratio. Impact of different dispersed and continuous phase flow rates on the diameter of the droplets generated in (d) vegetable oil, (e) silicone oil, and (f) mineral oil. Impact of different dispersed and continuous phase flow rates on the frequency of the droplets generated in (g) vegetable oil, (h) silicone oil, and (i) mineral oil. U1: dispersed-phase flow rate; U2: continuous-phase flow rate. U2/U1 value ranges from small to large in each setup. The set of experiments was terminated when the flow rate increased to the point where the dispersed phase assumed the jet state with no droplets.

After the droplet is successfully charged and generated, the positively charged droplets acquire more positive charges and are attracted to the negative deflection electrode, as shown in Fig. 8a. Figure 8b illustrates that the electric charges accumulated on the droplet surface increase with the charging voltage rising. The time-series simulation results in Fig. 8c give a better understanding of the deformations of the electrically charged droplets in deflection. Under the control of the deflection electrodes, the combined electric field force drives the droplet towards the negative electrode, as the positive electric charges are more in the electrically charged droplet (Fig. 8d–f). The practical experiment results in Fig. 8g show that the deflection between the staggered charged droplets becomes more pronounced with increasing charging voltage, which results from the increased charge accumulation on the droplet surface. After adopting the suitable charging voltage (500 V), the neighboring droplets do not interfere with each other, and droplet fusion is minimal. The effect of flow rate on deflection is provided in Supplementary Information Section 6.2.

a Schematic simulation of droplet deflection. b Surface electric charge of generated droplets at different charging voltages. The different colored lines represent the droplet’s surface current density along central axis 2 under different charging voltage conditions. From top to bottom, each line corresponds to a specific charging voltage, ranging from 500 V to −500 V in increments of 100 V. c Dispersed phase volume model. d Electric field force on the droplet in the y-direction. e Volume force on the droplet. f Electric potential distribution in the deflection region. g Real-time images of droplet deflection at different AC voltages, the charging signal is a rectangular wave AC signal with the frequency one-half of the droplet frequency.

Here we compare the results with the past studies. Ahn et al.85 first used electrostatic induction for on-demand droplet charging, conducting sufficient experiments to validate its robustness. This approach is used in our experiment to enhance the tip charging of continuous-phase fluids, achieving droplet charging at higher flow rates. Yao et al.59 simulated the theory of droplet deflection after electrostatic inductive charging and verified the feasibility of electrostatic sorting. We not only optimize their droplet charging structure but supplement the simulation about more hydrodynamic, electrical, and acoustic disturbances. Our contribution may advance this droplet charging method from an uncontrollable to a controllable process.

Application studies & final results

Figure 9a depicts the sorting experiments of 10 μm fluorescent microspheres. A photomultiplier with a bandpass filter, set to a sampling frequency of 5120 Hz (maximum 6000 Hz), was used to acquire the green fluorescent signal (Fig. 9b). It excels in detecting fluorescent pulse peaks, but an apparent limitation is that the acquired fluorescence pulse peaks are unstable. We speculate that this may be due to the signal distortion caused by insufficient sampling frequency or the agglomeration of fluorescent particles resulting in too strong peaks. The PS microspheres experiment confirms the validity of our laser window, with uniform and stable signals and accurate sorting performance (Fig. 9c, d). The pulse signal peaks in magnetic bead experiments are more chaotic, although the magnetic beads can be detected (Fig. 9e, f). To explain this phenomenon, we perform the real-time images on the high-speed camera and compare them with the optical signals pulse at the same moment. It is confirmed that the excessive pulse peaks are caused by bead bonding. The above experimental results are accomplished through the optical structure as shown in Fig. 9g. This structure has been mentioned previously in Fig. S25e and supports forward detection and multicolor fluorescence detection for flow cytometry analysis. An optical fiber perpendicular to the microfluidic channel is used for forward laser detection. The other incident fiber angled at 45 degrees can replace with other color laser. The last fiber at the receiving end is equipped with multicolor bandpass filters. Only green fluorescence is detected in this experiment. The effect of flow rate on system detection and sorting is provided in Supplementary Information Section 6.1.

a 10 μm fluorescent microspheres sorting. b Photomultiplier tube samples signal for fluorescence detection. c 10 μm PS microspheres sorting. d Silicon photodiode samples signals for PS microspheres detection. e 10 μm magnetic beads sorting. f Silicon photodiode samples signals for magnetic detection. g Miniaturized optical path structure.

The experiments under ideal conditions such as using PS microspheres and magnetic beads cannot meet our practical needs. Only the actual biological application experiments will better highlight the value of the system. H22 cells are the commonly used mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Large-size H22 cells play unique roles in applications such as gene editing, cell fusion, and tumor microenvironment simulation. H22 cells in this study were obtained from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). As shown in Fig. 10a, the H22 cells with diameters exceeding 20 μm are sorted and collected. These large-sized cells are enriched in the collection chamber (Fig. 10b). Cell viability tests are performed after the enrichment is completed (Fig. 10c). Large-sized cells obscure a larger area of the laser beam when they pass through the laser detection area, exciting larger amplitude pulse (Fig. 10d). Based on this feature, the foreground analytical experiment can determine a sorting threshold (half the maximum pulse amplitude). This value excels in the overall enrichment experiments (Fig. 10e). At the droplet generation frequency of 1180 Hz, we set the charging pulse width of 3 ms to capture the target droplets. Considering single charging pulses as the minimum events can assess the detection ability. The results show 95.2% precision, 90.9% recall, and 99.8% accuracy. Considering individual droplets as minimum events can measure system sorting ability. On this basis, the droplet sorting demonstrates high precision and accuracy, but its recall is reduced due to the wide charging pulse causing empty-packet droplets. From this standpoint, future research can focus on optimizing the selection of charging pulse width to cope with different scenarios. Other results are satisfactory, with successfully sorted droplets enriched in the collection room. The post-enrichment cell viability is 94.3%, equal to or better than currently accepted results88. The concentration of enriched large-sized cells was increased by 86 times. To our knowledge, this represents the largest reported enrichment improvement on a marked microfluidic platform for high-purity enrichment of rare cells.

a Sorting H22 cells with a diameter greater than 20 μm. b Observation of collection chambers on the chip. c Cell viability assay. d Silicon photodiodes sampling signals for H22 cells. e Evaluation indicators of cell detection, droplets sorting, cell concentration, and cell viability. P precision, R Recall, Acc Accuracy.

The video of sorting different particles is provided in Supplementary Video 2. The video of sorting enrichment H22 cells is provided in Supplementary Video 3.

Cell sorting is a highly demanding task. Based on our experimental results, we calculated the newly introduced metrics in cell sorting and purification, comparing them with the existing high-throughput microfluidic sorting methods. The results are shown in Table 1. Centrifugation and magnetic separation remain the primary methods for large-amount cell sorting88,89. These two methods fulfill the need for high throughput, saving time and cost, but they struggle to break through limitations in accuracy and recovery efficiency. This seems to be the main problem with large-amount processing and persists in dielectrophoresis and cell stiffness sorting90,91. Using microelectromechanical systems to enable one-to-one cell analysis and manipulation is particularly meaningful. It is obvious from the results that the one-to-one sorting methods such as piezoelectric actuators and SAW sorting have shown improvement in recovery efficiency or sorting purity92,93. Hulspas et al.94 used multiplexed parallel sorters to achieve faster throughput, demonstrating that the throughput limitation can be overcome by adding parallel units. Although our well-designed microfluidic microelectromechanical systems chip is not pulled apart much in throughput, this breakthrough hints to us that throughput constraints no longer limit our approach. Our final enrichment results surpass most comparison methods in purity and recovery efficiency, with purity improvements reaching up to 1129.6%.

With the advent of the big data era and the rapid development of deep learning, image detection response speeds have reached the millisecond level. In the above statistics, the object detection model YOLOv1095 is employed for the detection and counting of single-cell droplets by converting high-speed camera images into a 30-frame video. This preliminarily verifies the feasibility of cell detection, classification, and counting using image detection. We believe that in the future, with the improvement of the algorithm response speed, we can combine optical signals with image information for machine learning, enabling real-time cell detection and sorting. Details can be found in Video 4 of the supplementary material.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the successful integration of acoustic, optical, and electrical methods in picoliter droplet microfluidics, significantly enhancing the enrichment of ultra-rare particles. Our innovative design, incorporating acoustic and flow focusing, optical fibers, laser windows, and low-temperature phase change deflector electrodes, has led to substantial improvements in detection sensitivity and manipulation accuracy. Experimental results show that the detection and sorting accuracy for large-size H22 cells reached 99.8% and 99.3%, respectively, with a nearly 86-fold increase in target cell concentration. Our work offers remarkable improvements in purity and recovery efficiency compared to existing high-throughput microfluidic sorting methods, achieving purity improvements up to 1129.6%. and providing a comprehensive solution for rare particles enrichment. This research is poised to advance real-time cell sorting detection, paving the way for broader applications in biomedical diagnostics or environmental monitoring.

Data availability

Data available on request from the authors.

Code availability

The code is available on request from the authors.

References

Ersoy, B., Beşirli, M. U., Topal, S., Sözer, B. S. & Burat, F. Descriptive Process Mineralogy to Evaluate Physical Enrichment Potential of Malatya/Kuluncak Rare Earth Ore through MLA. Minerals 13, 1197 (2023).

Ni, C., Zhu, Z., Zhou, Z. & Xiang, N. High-Throughput Separation and Enrichment of Rare Malignant Tumor Cells from Large-Volume Effusions by Inertial Microfluidics. In Microfluidic Systems for Cancer Diagnosis (Springer, New York, 2023).

Shen, F. et al. Vortex sorting of rare particles/cells in microcavities: A review. Biomicrofluidics 18, 021504 (2024).

Harouaka, R. A., Nisic, M. & Zheng, S.-Y. Circulating tumor cell enrichment based on physical properties. J. Lab. Autom. 18, 455–468 (2013).

Gabriel, M. T., Calleja, L. R., Chalopin, A., Ory, B. & Heymann, D. Circulating tumor cells: a review of non–EpCAM-based approaches for cell enrichment and isolation. Clin. Chem. 62, 571–581 (2016).

Arya, S. K., Lim, B. & Rahman, A. R. A. Enrichment, detection and clinical significance of circulating tumor cells. Lab a Chip 13, 1995–2027 (2013).

Wu, X. et al. Selective enrichment of bacterial pathogens by microplastic biofilm. Water Res. 165, 114979 (2019).

Chen, Z., Elektorowicz, M., An, C. & Tian, X. Entrainment and enrichment of microplastics in ice formation processes: implications for the transport of microplastics in cold regions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 3176–3186 (2023).

Gao, F. et al. Study on the capability and characteristics of heavy metals enriched on microplastics in marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 144, 61–67 (2019).

Hemmati, M., Rajabi, M. & Asghari, A. Magnetic nanoparticle based solid-phase extraction of heavy metal ions: a review on recent advances. Microchimica Acta 185, 1–32 (2018).

Nayak, A., Jena, M. & Mandre, N. Application of enhanced gravity separators for fine particle processing: An overview. J. Sustain. Metall. 7, 315–339 (2021).

Hildebrandt, L., Mitrano, D. M., Zimmermann, T. & Pröfrock, D. A nanoplastic sampling and enrichment approach by continuous flow centrifugation. Front. Environ. Sci. 8, 538933 (2020).

Kim, J., Tan, Z. & Lubman, D. M. Exosome enrichment of human serum using multiple cycles of centrifugation. Electrophoresis 36, 2017–2026 (2015).

Jiang, Y. et al. A multilayer lateral-flow microfluidic device for particle separation. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 22, 40 (2018).

Peterson, B. W., Sharma, P. K., van der Mei, H. C. & Busscher, H. J. Bacterial cell surface damage due to centrifugal compaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 120–125 (2012).

Urbina, A., Godoy-Silva, R., Hoyos, M. & Camacho, M. Acute hydrodynamic damage induced by SPLITT fractionation and centrifugation in red blood cells. J. Chromatogr. B 1020, 53–61 (2016).

He, S. et al. Combining rVAR2 and Anti-EpCAM to Increase the Capture Efficiency of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Cell Lines in the Flow Enrichment Target Capture Halbach (FETCH) Magnetic Separation System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 9816 (2024).

He, J., Huang, M., Wang, D., Zhang, Z. & Li, G. Magnetic separation techniques in sample preparation for biological analysis: a review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 101, 84–101 (2014).

Tang, Y. et al. Highly sensitive and rapid detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa based on magnetic enrichment and magnetic separation. Theranostics 3, 85 (2013).

Lee, J.-J. et al. Synthetic ligand-coated magnetic nanoparticles for microfluidic bacterial separation from blood. Nano Lett. 14, 1–5 (2014).

Sesen, M., Alan, T. & Neild, A. Droplet control technologies for microfluidic high throughput screening (μHTS). Lab a Chip 17, 2372–2394 (2017).

Kaminski, T. S. & Garstecki, P. Controlled droplet microfluidic systems for multistep chemical and biological assays. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 6210–6226 (2017).

Whitesides, G. M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 442, 368–373 (2006).

Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Onck, P. & den Toonder, J. A concise review of microfluidic particle manipulation methods. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 24, 24 (2020).

Gurkan, U. A. et al. Next generation microfluidics: fulfilling the promise of lab-on-a-chip technologies. Lab a Chip 24, 1867–1874 (2024).

Gai, H., Li, Y. & Yeung, E. S. Optical detection systems on microfluidic chips. Microfluidics: Technol. Appl. 304, 171–201 (2011).

Nsabimana, J. et al. An electrochemical method for a rapid and sensitive immunoassay on digital microfluidics with integrated indium tin oxide electrodes coated on a PET film. Analyst 146, 4473–4479 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Recent advances in acoustic microfluidics and its exemplary applications. Biomicrofluidics 16, 031502 (2022).

Park, J., Destgeer, G., Kim, H., Cho, Y. & Sung, H. J. In-droplet microparticle washing and enrichment using surface acoustic wave-driven acoustic radiation force. Lab a Chip 18, 2936–2945 (2018).

Shi, J., Mao, X., Ahmed, D., Colletti, A. & Huang, T. J. Focusing microparticles in a microfluidic channel with standing surface acoustic waves (SSAW). Lab a Chip 8, 221–223 (2008).

Xuan, X., Zhu, J. & Church, C. Particle focusing in microfluidic devices. Microfluidics nanofluidics 9, 1–16 (2010).

Fornell, A., Garofalo, F., Nilsson, J., Bruus, H. & Tenje, M. Intra-droplet acoustic particle focusing: simulations and experimental observations. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 22, 75 (2018).

Liu, G. et al. Multi-level separation of particles using acoustic radiation force and hydraulic force in a microfluidic chip. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 23, 1–10 (2019).

Fornell, A., Pohlit, H., Shi, Q. & Tenje, M. Acoustic focusing of beads and cells in hydrogel droplets. Sci. Rep. 11, 7479 (2021).

Collins, D. J. et al. Self-aligned acoustofluidic particle focusing and patterning in microfluidic channels from channel-based acoustic waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 074502 (2018).

Ota, N. et al. Enhancement in acoustic focusing of micro and nanoparticles by thinning a microfluidic device. R. Soc. open Sci. 6, 181776 (2019).

Sambrano, J. Jr, Rodriguez, F., Martin, J. & Houston, J. P. Toward the development of an on-chip acoustic focusing fluorescence lifetime flow cytometer. Front. Phys. 9, 647985 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Single-cell sorting using integrated pneumatic valve droplet microfluidic chip. Talanta 253, 124044 (2023).

Ning, S. et al. A microfluidic chip with a serpentine channel enabling high-throughput cell separation using surface acoustic waves. Lab a Chip 21, 4608–4617 (2021).

Collins, D. J., Neild, A. & Ai, Y. Highly focused high-frequency travelling surface acoustic waves (SAW) for rapid single-particle sorting. Lab a Chip 16, 471–479 (2016).

Lashkaripour, A. et al. Machine learning enables design automation of microfluidic flow-focusing droplet generation. Nat. Commun. 12, 25 (2021).

Tang, S. K., Stan, C. A. & Whitesides, G. M. Dynamically reconfigurable liquid-core liquid-cladding lens in a microfluidic channel. Lab a Chip 8, 395–401 (2008).

Shivhare, P., Prabhakar, A. & Sen, A. Optofluidics based lab-on-chip device for in situ measurement of mean droplet size and droplet size distribution of an emulsion. J. Micromech. Microeng. 27, 035003 (2017).

Yang, H. & Gijs, M. A. Micro-optics for microfluidic analytical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 1391–1458 (2018).

Rosenauer, M., Buchegger, W., Finoulst, I., Verhaert, P. & Vellekoop, M. Miniaturized flow cytometer with 3D hydrodynamic particle focusing and integrated optical elements applying silicon photodiodes. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 10, 761–771 (2011).

Zhao, Y., Hu, X.-g, Hu, S. & Peng, Y. Applications of fiber-optic biochemical sensor in microfluidic chips: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 166, 112447 (2020).

Gupta, P. et al. Multiplexed fluorescence and scatter detection with single cell resolution using on-chip fiber optics for droplet microfluidic applications. Microsyst. Nanoengineering 10, 35 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Li, Q., Hu, X. & Lo, Y. Microfluidic cytometers with integrated on-chip optical systems for red blood cell and platelet counting. Biomicrofluidics 10, 064119 (2016).

Hengoju, S., Shvydkiv, O., Tovar, M., Roth, M. & Rosenbaum, M. A. Advantages of optical fibers for facile and enhanced detection in droplet microfluidics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 200, 113910 (2022).

Kumar, S. et al. LSPR-based cholesterol biosensor using a tapered optical fiber structure. Biomed. Opt. express 10, 2150–2160 (2019).

Fu, L.-M., Yang, R.-J., Lin, C.-H., Pan, Y.-J. & Lee, G.-B. Electrokinetically driven micro flow cytometers with integrated fiber optics for on-line cell/particle detection. Analytica Chim. Acta 507, 163–169 (2004).

Stephenson, W. High-throughput magnetic particle washing in nanoliter droplets using serial injection and splitting. Micro Nano Syst. Lett. 6, 1–10 (2018).

Qin, X., Wang, H. & Wei, X. Intra-droplet particle enrichment in a focused acoustic field. RSC Adv. 10, 11565–11572 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. From passive to active sorting in microfluidics: A review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 60, 313–324 (2021).

Huang, C., Jiang, Y., Li, Y. & Zhang, H. Droplet detection and sorting system in microfluidics: a review. Micromachines 14, 103 (2022).

Tirapu-Azpiroz, J., Temiz, Y. & Delamarche, E. Dielectrophoretic microbead sorting using modular electrode design and capillary-driven microfluidics. Biomed. Microdevices 19, 95 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Luo, Y., Nie, X., Yu, D. & Xing, X. A one-step molded microfluidic chip featuring a two-layer silver-PDMS microelectrode for dielectrophoretic cell separation. Analyst 145, 5603–5614 (2020).

Luo, J., Nelson, E. L., Li, G. & Bachman, M. Microfluidic dielectrophoretic sorter using gel vertical electrodes. Biomicrofluidics 8, 034105 (2014).

Yao, J. et al. A novel integrated microfluidic chip for on-demand electrostatic droplet charging and sorting. Bio-Des. Manuf. 7, 31–42 (2024).

Ma, Z., Zhou, Y., Collins, D. J. & Ai, Y. Fluorescence activated cell sorting via a focused traveling surface acoustic beam. Lab a Chip 17, 3176–3185 (2017).

Zhong, J., Liang, M., Tang, Q. & Ai, Y. Selectable encapsulated cell quantity in droplets via label-free electrical screening and impedance-activated sorting. Mater. Today Bio 19, 100594 (2023).

Sui, M. et al. Acoustofluidic Tweezers Integrated with Droplet Sensing Enable Multifunctional Closed‐Loop Droplet Manipulation. Adv. Sci. 12, 2409394 (2025).

Whitesides, G. M., Ostuni, E., Takayama, S., Jiang, X. & Ingber, D. E. Soft lithography in biology and biochemistry. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 3, 335–373 (2001).

Hsu, T.-H., Tsai, C.-H., Tung, S.-S. & Li, M.-H. Miniature LiNbO 3/SiO 2/Si SH-SAW resonators with near-spurious-free response. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 44, 1200–1203 (2023).

Osipovich, K. et al. Wire-feed electron beam additive manufacturing: A review. Metals 13, 279 (2023).

Olofsson, K., Hammarström, B. & Wiklund, M. Acoustic separation of living and dead cells using high density medium. Lab a chip 20, 1981–1990 (2020).

Shields, C. W. IV, Johnson, L. M., Gao, L. & López, G. P. Elastomeric negative acoustic contrast particles for capture, acoustophoretic transport, and confinement of cells in microfluidic systems. Langmuir 30, 3923–3927 (2014).

Ward, M., Turner, P., DeJohn, M. & Kaduchak, G. Fundamentals of acoustic cytometry. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 49, 1.22. 1–1.22. 12 (2009).

Harshbarger, C. L. et al. Measuring and simulating the biophysical basis of the acoustic contrast factor of biological cells. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.04061 (2023).

Fakhfouri, A. et al. Surface acoustic wave diffraction driven mechanisms in microfluidic systems. Lab a Chip 18, 2214–2224 (2018).

Zhu, J., Popovics, J. S. & Schubert, F. Leaky Rayleigh and Scholte waves at the fluid–solid interface subjected to transient point loading. J. Acoustical Soc. Am. 116, 2101–2110 (2004).

Li, S., Song, Y., Turner, J. A. & Li, X. Propagation of leaky Rayleigh waves along a curved fluid–solid interface. J. Acoustical Soc. Am. 150, 4395–4405 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. Three-dimensional continuous particle focusing in a microfluidic channel via standing surface acoustic waves (SSAW). Lab a Chip 11, 2319–2324 (2011).

Nam, J. et al. Microfluidic device for sheathless particle focusing and separation using a viscoelastic fluid. J. Chromatogr. A 1406, 244–250 (2015).

Fan, Y.-J. et al. Development of a parallel three-dimensional microfluidic device for high-throughput cytometry. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 320, 128255 (2020).

Chen, Y., Wu, T.-H., Kung, Y.-C., Teitell, M. A. & Chiou, P.-Y. 3D pulsed laser-triggered high-speed microfluidic fluorescence-activated cell sorter. Analyst 138, 7308–7315 (2013).

Koigerov, A. Surface Acoustic Wave Devices on Frequency Harmonics. Features of Calculating SAW Parameters by the Finite Element Method. Optics Spectrosc. 132, 54–63 (2024).

Pouya, C. et al. Frequency dependence of surface acoustic wave swimming. J. R. Soc. Interface 16, 20190113 (2019).

Shen, L. et al. Acousto-dielectric tweezers enable independent manipulation of multiple particles. Sci. Adv. 10, eado8992 (2024).

Tian, Z. et al. Wave number–spiral acoustic tweezers for dynamic and reconfigurable manipulation of particles and cells. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau6062 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. A real-time peak-detection approach for nuclear detection and its implementation on an FPGA. Radiat. Detection Technol. Methods 4, 161–173 (2020).

Gupta, A. et al. A-TSPD: autonomous-two stage algorithm for robust peak detection in online time series. Clust. Comput. 27, 4063–4076 (2024).

Zhu, P. & Wang, L. Passive and active droplet generation with microfluidics: a review. Lab a Chip 17, 34–75 (2017).

Utada, A. S., Fernandez-Nieves, A., Stone, H. A. & Weitz, D. A. Dripping to jetting transitions in coflowing liquid streams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 094502 (2007).

Ahn, B., Lee, K., Panchapakesan, R. & Oh, K. W. On-demand electrostatic droplet charging and sorting. Biomicrofluidics 5, 24113 (2011).

Hung, L.-H. et al. Alternating droplet generation and controlled dynamic droplet fusion in microfluidic device for CdS nanoparticle synthesis. Lab a Chip 6, 174–178 (2006).

Yao, J., Lin, F., Kim, H. S. & Park, J. The effect of oil viscosity on droplet generation rate and droplet size in a T-junction microfluidic droplet generator. Micromachines 10, 808 (2019).

Warkiani, M. E. et al. Slanted spiral microfluidics for the ultra-fast, label-free isolation of circulating tumor cells. Lab a Chip 14, 128–137 (2014).

Yu, Z. et al. ExoSD chips for high-purity immunomagnetic separation and high-sensitivity detection of gastric cancer cell-derived exosomes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 194, 113594 (2021).

Song, H. et al. Continuous-flow sorting of stem cells and differentiation products based on dielectrophoresis. Lab a Chip 15, 1320–1328 (2015).

Islam, M. et al. Microfluidic sorting of cells by viability based on differences in cell stiffness. Sci. Rep. 7, 1997 (2017).

Nawaz, A. A. et al. Acoustofluidic fluorescence activated cell sorter. Anal. Chem. 87, 12051–12058 (2015).

Cheng, Z., Wu, X., Cheng, J. & Liu, P. Microfluidic fluorescence-activated cell sorting (μFACS) chip with integrated piezoelectric actuators for low-cost mammalian cell enrichment. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 21, 1–11 (2017).

Hulspas, R. et al. Purification of regulatory T cells with the use of a fully enclosed high-speed microfluidic system. Cytotherapy 16, 1384–1389 (2014).

Wang, A., Chen, H., Liu, L., Chen, K., Lin, Z. & Han, J. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 107984–108011 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of HUST: 2024JYCXJJ031 and the Interdisciplinary Research Program of HUST: 2024JCYJ070. The authors would like to express great gratitude to the Analytical and Testing Center, Flexible Electronics Research Center, Measurement Laboratory of Collaborative Innovation Center, and Wuhan National Laboratory for Optoelectronics of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for the assistances in the processes of lithography, bonding, and characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Huasheng Zhuo: Jointly designed the experimental framework, including conceptualization and methodology. Performed all key experiments, analyzed raw datasets, curated data, and contributed to writing the original manuscript draft. Chunhua He: Equally contributed to designing the experimental framework, conducting essential experiments, performing data analysis and curation, and drafting the original manuscript. Canfeng Yang: Developed computational tools and software required for the study and validated experimental protocols. Xian Jiang: Conducted supplementary experiments and contributed to data interpretation and visualization. Fan Li: Provided essential reagents, cell lines, and technical resources necessary for the experiments. Xiangliang Yang: Performed statistical analyses and generated relevant figures for data representation. Hai Yang: Assisted in statistical analyses and figure generation to support experimental results. Tuying Yong: Managed experimental quality control and assessed reproducibility, ensuring validation and supervision of the study. Zhiyong Liu: Supervised the project, critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, and secured funding for the study. Yan Ma: Contributed to funding acquisition and coordinated institutional administrative support for the project. Lei Nie: Played a key role in securing funding and facilitating institutional coordination necessary for the research. Guanglan Liao: Provided project supervision, contributed to manuscript revision for intellectual content, and managed funding acquisition. Tielin Shi: Oversaw research infrastructure, supported cross-team collaborations, and provided critical resources for the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Caglar Elbuken and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Massimo Mastrangeli] and [Miranda Vinay and Rosamund Daw]. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, H., He, C., Yang, C. et al. Integration of acoustic, optical, and electrical methods in picoliter droplet microfluidics for rare particles enrichment. Commun Eng 4, 86 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00427-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00427-0