Abstract

Cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAP) is emerging as a clinically relevant therapy for dermatological conditions such as actinic keratosis, warts, and chronic wounds. However, these therapies lack strategies to monitor CAP delivery in situ and to ensure delivery of an effective CAP dose without unwanted toxicity. CAP acts as a therapeutic agent in these biomedical applications primarily (but not solely) through reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) generated at transiently high local concentrations. Here we demonstrate the use of bio-electrochemical sensors capable of real-time measurements of key CAP RONS: hydrogen peroxide and oxidation-reduction-potential (ORP). In in vitro scratch assays and in vivo murine wound models, we used these sensors to establish dose-response relationships that link CAP exposure with wound (scratch) closure dynamics, cell proliferation, oxidative stress response, and scar reduction. Our results demonstrate that CAP treatment can be continuously monitored and actively controlled in situ, providing a framework for precision plasma medicine and safer, more effective clinical translation of CAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAP) is a promising therapeutic tool with applications in decontamination, oncology, and wound healing1. Clinical trials with approved CAP devices have demonstrated efficacy in treating chronic wounds and diabetic ulcers2. The biological effects of CAP in these applications are primarily (but not solely) mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS)3, including H₂O₂, OH., O2-, NO, and related derivatives. These RONS play critical roles in tissue repair4 and are thought be integral to the role of CAP as a safe therapeutic tool used for wound healing5.

In biomedical applications of CAP, however, delivery of the appropriate CAP dose remains a major challenge. As with many therapeutic agents, such as small molecule drugs or radiation, dose control is necessary to strike an appropriate balance between therapeutic effectiveness and unwanted side effects or toxicity. In biomedical applications of CAP, the major challenge is precise dosing of CAP to achieve therapeutic benefits without CAP-associated toxicity, including oxidative damage. We propose that this challenge can be addressed through real-time RONS detection and closed-loop CAP control6.

While regulated delivery of plasma is routinely achieved for non-biological applications, translation of this control to biomedical uses of CAP presents multiple challenges. In semiconductor processing, plasma delivery is controlled in real time7,8 through electrical feedback9, optical emission spectroscopy10,11, and material analysis12. These methods, however, are not suitable for biological applications. Diagnostic systems required for comprehensive plasma monitoring are often impractical in clinical settings. While measurements of physical plasma parameters, such as those measured by optical emission spectroscopy13 or thermal profiles14,15, are good indicators of potential damage, they offer little predictive power for biological outcomes. Indeed, they were recently shown to be insufficient for determining therapeutic dose16. In addition, these methods have limited effectiveness and utility in biological applications in which RONS are principal effectors.

Continuous monitoring of CAP-generated RONS during treatment offers a direct path toward clinically relevant therapeutic protocols. However, most existing RONS detection methods can only be used post-treatment and require bulky equipment or large fluid volumes17, making them unsuitable for in situ measurements in vitro and in vivo. The use of RONS for feedback control is also complicated by interactions between RONS and heterogeneous biological tissues that limit the scope and accessibility of parameters for characterizing CAP treatments18. Finally, the transitory nature of elevated RONS concentrations after CAP exposure limits the window of time available for detection.

Advances in sensor design have changed landscape of detection. New assembly methods19,20 and materials21,22 have enabled the development of miniaturized (bio-)electrochemical sensors for real-time measurements in small scale biological environments23. Such sensors are already used for continuous monitoring of biological markers, such as glucose24. Compact potentiostat microcontrollers can be embedded within the biochemical environment to interpret amperometric25 or potentiometric26 signals, correlating current or voltage changes with analyte concentrations within a test sample27. These approaches have recently been adapted to detect hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂)28,29 and oxidation-reduction-potential (ORP)30,31.

Both H₂O₂ and ORP are critical in wound healing and highly relevant for CAP therapy32. H₂O₂ serves as a key signaling molecule in regulated cascades that activate various metabolic processes involved in wound healing33. Many processes driven by growth factors and chemokines involve transient intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) spikes34. Because CAP strongly increases oxidative stress, monitoring H₂O₂ is essential. However, H2O2 alone cannot capture the full spectrum of CAP effects35. ORP, defined as the balance between oxidants (e.g., OH., O2-, H₂O₂, NO) and reductants (antioxidants such as electrons, H), reflects overall redox status36. Importantly, wound healing requires dynamic redox regulation. Early phases of wound healing use high ROS levels to promote bacterial killing and inflammation, whereas later stages are characterized by lower ROS levels that support collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and epithelialization5. Thus, ORP complements H₂O₂ measurement as an integrated marker of oxidative stress and, by extension, a complementary measure of CAP dosing.

This work demonstrates the feasibility of a control system for CAP treatment that uses real-time feedback from bio-electrochemical sensors. In the following studies, we used an in vitro wound model (scratch assay) and a murine wound healing model to correlate CAP exposure (as measured by H₂O₂ and ORP sensors) with subsequent biological responses. Measured biological outcomes included changes in oxidative stress, viability, and proliferation in CAP-exposed cells, and altered wound healing outcomes in mice. Because precise cause-and-effect relationships between CAP effectors and cellular mechanisms can be challenging to determine, this study was instead conducted to establish correlations between real-time analyte measurements and long-term biological outcomes (i.e., wound healing) indicative of an effective CAP dose. We then developed a CAP control scheme with sensor-based endpoint detection and setpoints correlated to wound healing outcomes. Applying this scheme to CAP treatment, a CAP device and an associated controller were successfully used in vivo to demonstrate closed loop control of CAP delivery.

Results

Establishing CAP dose in vivo and in vitro

Initial experiments were conducted to establish in vitro and in vivo CAP doses that covered a full spectrum of effects. The in vitro dose definition was based on cell viability and scratch closure assays following CAP exposures of 5, 10, and 15 s (Fig. 1f, g). A 5 s exposure of HaCaT cells to CAP did not affect viability or scratch closure compared to the untreated controls. After 10 s, insignificant loss of viability was observed with marginally improved scratch closure (Fig. 1c–e). In contrast, 15 s of CAP exposure reduced viable cell counts and compromised scratch closure. From these observations we defined 5 s as suboptimal, 10 s as optimal, and 15 s as excessive for in vitro experiments. Exposures longer than 15 s were excluded from in vitro exposures, as they consistently caused extensive cell death and loss of the cell monolayer, preventing meaningful assessment of scratch closure or viability.

a Illustration of scratch-wounded HaCaT keratinocytes plated in a 24-well plate prior to CAP exposure. b Experimental setup for CAP exposure of HaCaT cells to determine an acceptable in vitro dose definition. c Representative brightfield image (4×) of the 10 s CAP exposure group pre-treatment (0 h). d Preprocessed image from panel c with object mask placement for wound-width analysis. e Preprocessed brightfield image with object mask placement for analysis at 24 h after a 10 s CAP exposure. f HaCaT cell viability 24 h after CAP exposure for 5 s, 10 s, or 15 s (9 data points from 3 biological replicates). g Percent decrease in wound width after CAP treatment times (15 data points from 5 biological replicates). f, g Data points (black, diamond) for each exposure time, with the statistical mean (clear, squares), median (black, line in the center of box plot), interquartile ranges (box range: 25–75th percentile of data set), and outer legs of each box (lower 5th percentile and upper 95th percentile of data set) are showcased. Outliers were shown above or below the outer legs. Statistical differences between 0 s and exposure groups are identified by: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05. Exact p values can be found in supplemental data 1. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used. Together, these formed the basis for in vitro suboptimal (5 s), optimal (10 s), and excessive (15 s) dose definition compared to no CAP exposure (0 s).

To establish a safe CAP dose range for in vivo experiments, depilated murine dorsum skin was exposed to increasing CAP exposure durations (60–300 s) and monitored daily for 7 days (Fig. 2). After a 60 s exposure, no visible effects were observed on exposed skin. Transient damage appeared after 180 s of CAP treatment but was resolved within 1–2 days. After a 300 s exposure, skin damage was immediately visible but was spontaneously healed by day 7 (Fig. 2c). In parallel histological analyses, skin tissue samples were collected immediately, 24 h, and 7 days post-treatment and assessed (Fig. 2d) No evidence of tissue damage was seen after the 60 s and 180 s CAP exposures. Migration of inflammatory cells into the CAP-treated area on post-exposure day 1 was observed after 180 s CAP exposure, but not in mice that received the 60 s CAP exposure. In contrast, histological damage was evident in skin samples collected following a 300 s CAP exposure. These findings informed the selection of 60 s as suboptimal, 180 s as optimal, and 300 s as excessive doses for the in vivo sensor studies.

a Experimental setup for in vivo dose definition study. b CAP streamers (pink triangle) during exposure (10 mm diameter electrode) ~1 mm above the skin. c Representative images of CAP-treated areas (60 s, 180 s, and 300 s exposures) in different tested groups over 1 week. Scale bar = 10 mm (dotted circle). Red triangles indicate the grossly visible damage area immediately after CAP treatment (300 s, Day 0) and scar area on days 2, 3, and 7. Exposure location is denoted by white triangles. d Representative H&E-stained histological images of normal tissue skin, CAP-treated (300 s group only) immediately after CAP, and day 1 and day 7 post-treatment. Day 1 shows tissue damage and related inflammation (blue arrows). Day 7 images show completely healed skin with a regenerative epidermis. Yellow arrows denote the epidermis, dermis, muscle, and hair follicles for the normal skin tissue.

Measurement of H₂O₂ and ORP in CAP treated PBS using bio-electrochemical sensors

To establish the feasibility of H₂O₂ and ORP sensor measurements, 500 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was exposed to CAP in a 24-well plate (Fig. 3a). Sensor measurements were taken before and immediately after each treatment, with validation of readings being conducted via colorimetric assay (Supplementary Fig. 1). The treatment times corresponded to those chosen for in vitro (5, 10, 15 s) and in vivo studies (60, 180, 300 s). A discernable, yet statistically insignificant, change in H₂O₂ concentration was seen in the PBS solution after 10 and 15 s of CAP treatment when compared to the untreated PBS (Fig. 3b). Upon treatment of 60, 180, and 300 s, a dose-dependent increase was observed with the largest rise in the mean H₂O₂ (16 µM) between 180 s and 300 s (Fig. 3c). ORP followed a similar dose-dependent increase, with higher intra-sample variability (Fig. 3d). ORP readings after 5 s of CAP treatment trended lower than baseline readings (0 s), potentially due to the produced RONS reducing the concentration of dissolved oxygen37 or other oxidizing species in the PBS. This is reinforced by our observation that treatment times longer than 15 s reduced the variability in the data (Fig. 3e). Single bar plots for each well are provided exemplarily for the 180 s treatment in Supplementary Fig. 2a for H2O2 and 2c for ORP.

a Experimental setup for CAP treated PBS (blue) in a 24-well plate. All measurements were performed in 500 µL PBS. Nine data points are plotted (black, diamond) for each treatment time in (b, c, e), and four data points in (d), with the statistical mean (clear, squares), median (black, line in the center of box plot), interquartile ranges (box range: 25–75th percentile of data set), and outer legs of each box (lower 5th percentile and upper 95th percentile of data set) being showcased. Outliers appear above or below the outer legs. b, d Concentration values of H2O2 and voltage readings for ORP corresponding to no CAP treatment (0 s), suboptimal (5 s), optimal (10 s), and excessive (15 s) doses used in in vitro cell line studies. c, e Concentrations of H2O2 and voltage readings for ORP corresponding to no CAP treatment (0 s), suboptimal (60 s), optimal (180 s), and excessive (300 s) doses for in vivo wound studies. Statistical differences between 0 s and treatment groups are identified by: ns not significant; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. Exact p values can be found in supplemental data 1. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used.

In vitro sensor measurements and correlation to cellular markers

To establish that sensor measurements were possible in the presence of cells, H2O2 and ORP were measured before and immediately after CAP exposure of HaCaT keratinocytes in 500 µL PBS (Fig. 4a). Consistent with our previous observations38,39, ~5.6 µM H2O2 was detected in the PBS over the unscratched HaCaT monolayer as a likely byproduct of mitochondrial respiration. H2O2 increased to 10 µM after scratching (Fig. 4b). However, further increases in H2O2 concentration were not noted after a 5 s CAP treatment. In contrast, a dose-dependent increase was observed after 10 s and 15 s CAP treatment times. In ORP measurements, the presence of cells decreased the baseline ORP (Fig. 4c) by ~70 mV. As was the case in the H2O2 measurements, the scratch creation increased ORP by ~20 mV, suggesting cellular stress responses to the scratch. The increases in ORP did not differ significantly over the range of treatment durations. Nonetheless, the trends observed demonstrated the feasibility of using bio-electrochemical sensors to measure analytes in the presence of living cells.

a Experimental setup for CAP treated cells (pink) in a 24-well plate. All measurements were performed in 500 µL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). All data points are plotted (black, diamond) for each treatment time, with the statistical mean (clear, squares), median (black, line in the center of box plot), interquartile ranges (box range: 25–75th percentile of data set), and outer legs of each box (lower 5th percentile and upper 95th percentile of data set) being showcased. Outliers are shown above or below the outer legs. b, c H2O2 sensor (n = 12; n = 11 for 5 and 15 s, 4 biological replicates) and oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) voltage readings (n = 9, 3 biological replicates) were taken before (Before scratch) and immediately after a scratch (0 s) of the cell monolayer. Cells were then treated with suboptimal (5 s), optimal (10 s), and excessive (15 s) CAP doses. d, e MitoSOX+ (n = 8, 3 biological replicates) and Ki67+cells (n = 9, 3 biological replicates) were enumerated after no CAP (0 s) or treatment with suboptimal (5 s), optimal (10 s), and excessive (15 s) CAP doses to measure oxidative stress responses and cell proliferation, respectively. Statistical differences between 0 s and treatment groups are identified by: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Exact p values can be found in Supplemental Data 1. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used.

CAP-exposed cells were also evaluated for changes in oxidative stress. Because mitochondria serve as a major source of cellular RONS, superoxides (as measured by MitoSOX) can be used as a marker for oxidative stress. As shown in cancer cell lines after CAP exposure38,40, MitoSOX is upregulated by CAP. In these experiments, mitochondrial superoxide (MitoSOX) production increased in a dose-dependent manner immediately after CAP exposure for all treatment times (Fig. 4d). MitoSOX was highest after the 15 s CAP dose (p < 0.05). This significant increase in oxidative stress at 15 s exposure duration correlated with greater cell loss and a significant decrease in viability (Fig. 1f).

To build a foundation for establishing correlations between sensor readings and cellular responses relevant to scratch closure, expression of Ki67, a nuclear protein and cell proliferation marker commonly upregulated by CAP41, was measured. Although the suboptimal CAP treatment resulted in an apparent increase compared to the control, changes were statistically insignificant. A significant increase in Ki67 expression was observed for the optimal (10 s) CAP treatment (Fig. 4e) (p < 0.0001). Exposure to the excessive CAP duration led to reduced Ki67 expression, suggesting cell damage or compromised proliferation mechanisms (Fig. 1g). The correlation between optimal CAP dose and Ki67 levels may reflect changes in H2O2 concentration or total redox state as measured by ORP. These results suggest that real-time measurements of CAP-generated species could serve as an indirect indicator of therapeutic CAP dose.

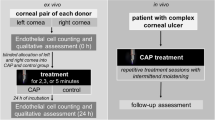

In vivo sensor measurements and wound healing

Experiments involving sensors were then extended to the murine model of wound healing. Full-thickness excisional wounds (10 mm) were created on the backs of mice to evaluate sensor performance in a wound environment. Baseline sensor measurements of H2O2 and ORP were taken in situ on the wound bed immediately after wounding (day 0). Wounds were then treated with suboptimal (60 s), optimal (180 s), or excessive (300 s) durations of CAP (Fig. 5a), followed by immediate post-treatment sensor readings (Fig. 5c, e). Representative current (Fig. 5b H2O2) and voltage (Fig. 5d ORP) profiles for each treatment duration with the sampling window around 20 s are shown. The H2O2 current signal (Fig. 5b) showed an initial spike followed by a decay to a stable level. A dose-dependent increase in current, and thus H2O2 concentration (as derived from the measured current), was observed. The baseline levels of ~10 µM H2O2 in PBS on fresh wounds were higher than in cell-free PBS (Fig. 3b) and in vitro cell culture (Fig. 4b). After 60 s of CAP treatment, H2O2 concentrations increased modestly by ~5 µM. Longer CAP treatment led to a statistically significant dose-dependent increase in H2O2: ~40 µM between 60 s and 180 s, and an additional ~11 µM between 180 s and 300 s. All in vivo H2O2 concentrations exceeded those in cell-free PBS (75 µM at 300 s vs. 32 µM in PBS).

a Experimental setup for cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) treated murine wounds. b, d Current response curves produced for H2O2 and voltage response curves produced for oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) measurements, respectively. Sensor readings were obtained from wire sensors within the wounds of mice prior to (0 s) and directly after CAP treatment for the established suboptimal (60 s), optimal (180 s), and excessive (300 s) doses. Sampling time for each response curve is indicated by the gray region centered at 20 s. c, e H2O2 concentrations and ORP values derived from the current and voltage response curves, respectively, are displayed for each treatment group. Both figures show data points (black, diamond) for each group, with the statistical mean (clear, squares), median (black, line in the center of box plot), interquartile ranges (box range: 25–75th percentile of data set), and outer legs of each box (lower 5th percentile and upper 95th percentile of data set) being showcased. Outliers are shown above or below the outer legs (black, diamond). 27 data points are shown in c for 0 s, n = 9 for all treatment times. 12 data points are shown in e for 0 s, n = 3 for 60 and 180 s, n = 6 for 300 s. Statistical differences between 0 s and treatment groups are identified by: *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001. Exact p values can be found in supplemental data 1. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used.

Baseline ORP measurements (0 s) in PBS applied to the fresh wound showed a mean value ~40 mV lower than those observed in in vitro cell culture (Fig. 4c), with a relatively large data spread (Fig. 5e). Despite this variability, a dose-dependent increase in ORP was observed following CAP treatment. In the voltage response curves (Fig. 5d), the untreated wounds showed a continuous decline without reaching steady state. In contrast, all CAP-treated groups reached a plateau, with the plateau level rising proportionally to treatment duration. This trend indicates an accumulation of oxidative species in the wound with increasing CAP exposure. A slight but statistically insignificant increase in ORP was seen after 60 s of treatment. Significant, dose-dependent increases in ORP followed the 180 s (p < 0.05) and the 300 s (p < 0.001) treatments. These increases in ORP are consistent with previously reported CAP effects on treated liquids42,43,44. Longer CAP treatments (180 and 300 s) displayed a more stable and sustained ORP increase with reduced variability across replicates. Single bar plots for each animal are provided exemplarily for the 180 s treatment in Supplementary Fig. 2b for H2O2 and 2d for ORP.

Next, correlations between CAP dose-dependent analyte levels and wound healing outcomes were evaluated. Mice received varied CAP doses immediately after excisional wounding (day 0) and were monitored for healing over 21 days (Fig. 6a). All groups reached 100% wound closure by day 21, but significant differences were observed on days 7 and 10 post-wounding (Fig. 6b). The 300 s CAP group showed delayed healing with significantly lower wound closure on days 7 (p < 0.05, 300 s vs. 0 s; p < 0.01, 180 s vs. 60 s; p < 0.0001, 300 s vs. 60 s) and 10 (p < 0.0001; 300 s vs. all groups). However, this delay was transient; all animals had fully closed wounds by day 21.

Defined doses of no CAP treatment (0 s), suboptimal (60 s), optimal (180 s), and excessive (300 s) were used to measure wound healing efficacy for in vivo murine wounds. a Representative images of skin wounds (10 mm) in different groups of mice over the period of 21 days. Scale bar = 1 cm. b Quantified wound images showing the fraction of wound closure as a function of time for CAP treatment durations of 0 s (circle), 60 s (pointed down triangle), 180 s (triangle), and 300 s (square). Plotted is the mean ± s.e.m., with error bars indicating the s.e.m. n = 9 for 0 s and 300 s, and n = 8 for 60 s and 180 s. Statistical significance was performed by two-way ANOVA, followed by post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test for results. Statistical difference between treatment groups was identified by: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001. Exact p values can be found in Supplementary Data 1. All data points corresponding to the figure can be found as box and whisker plots in Supplementary Fig. 4a–d. c, d Representative histology of healed wound skin (H&E stain) showing epidermis, dermis (double arrow), hair follicles, and wound edges (two green lines) for each treatment time group. Scale bar = 1 mm. e–g The impacts of varied CAP dose on indicators of wound healing were assessed by quantification of scar area (n = 9 for 0 s and 300 s, n = 8 for 60 and 180 s), wound width (n = 9), and Ki67+ cells (n = 9 for 0 s and 300 s, n = 8 for 60 and 180 s) for each treatment group of mice at day 21. Wound width was based on histology images (Fig. 6c, d). Quantification of Ki67+ cells was performed to evaluate cell proliferation and regrowth. Data points are plotted (black, diamond) with the groups statistical mean (clear, squares), median (black, line in the center of box plot), interquartile ranges (box range: 25–75th percentile of data set), and outer legs (lower 5th percentile and upper 95th percentile of data set) being showcased. Outliers of the dataset are shown above or below the outer legs (black, diamond). Statistical differences between 0 s and treatment groups are identified by: ns not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Exact p values can be found in Supplementary Data 1.

Wound tissues were harvested for histopathological analysis on day 21 (the termination of the study). Scar area was reduced significantly in the 60 and 180 s CAP treatment groups compared to the 0 and 300 s treatment groups (p < 0.05, 0 s vs. 60 s; p < 0.01, 0 s vs. 180 s; p < 0.001, 300 s vs. 60 s/180 s) (Fig. 6e), with the 180 s group showing the highest reduction. Consistent with this observation, healed wound width (distance measured between wound edges demarcated by loss of hair follicles) was significantly smaller (p < 0.05) in the 180 s group compared to all others (Fig. 6c, d, f). To evaluate cell proliferation within the newly formed tissue, Ki67+ cells were quantified (Fig. 6g). Although not statistically significant, Ki67+ cell counts showed a trend toward higher values at the optimal CAP dose. Similarly, epidermal and dermal thickness increased with treatment duration, but the changes did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Angiogenesis (CD31, α-SMA) and collagen deposition (Supplementary Fig. 3c–e) were also assessed to examine tissue quality under different CAP doses. While all parameters showed favorable trends in the 180 s group, none of the differences between groups were statistically significant.

Challenging the controller in situ for real-time endpoint detection

After demonstrating that H2O2 and ORP could be accurately detected in vitro and in vivo, the sensors were tested in situ as part of a proof of concept for real-time monitoring (Fig. 7a). To this end, a microcontroller equipped to perform continuous chronoamperometry was used as a feedback CAP control system that would automatically terminate CAP treatment once a predefined H2O2 concentration or ORP value was reached. To test the functionality of the device, a 20 s baseline measurement in PBS confirmed no detectable H2O2 prior to CAP treatment (Fig. 7b). Once CAP treatment began, a large and sudden increase in H2O2 concentration (~25 µM at 5 µM s−1) was observed. As has been reported by others28, this increase reflects a transient rise in the concentration readings due to the sudden oxidant flux at the electrode surface under continuous chronoamperometry measurement. The initial artifact stabilizes into a diffusion-limited steady state but does not accurately represent bulk peroxide accumulation during CAP ignition. To minimize this effect and other signal-to-noise ratio interferences from the CAP treatment, we implemented pulsed chronoamperometry (Fig. 8c) for all other H₂O₂ experiments in vivo. This approach refreshes the electrode surface and diffusion layer with each pulse and yields smoother, more linear responses that better capture the in situ H₂O₂ dynamics.

a Experimental setup for testing cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) real-time endpoint detection. The sensor was submerged horizontally in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) evenly distributed on a glass slide. This positioning was used to minimize direct CAP interaction with the sensor. b Live H2O2 wire sensor measurements during plasma treatment of a 500 µL PBS solution with voltage held constant. Concentration data (solid line) is displayed during CAP treatment at 20 kV, until the targeted concentration level (dashed line) is reached. c The time at which the plasma device is activated (1) and deactivated (0) is tracked over the course of the treatment protocol. The microcontroller actively evaluates every 20 s whether the previous result sampled is at or above 40 µM, at which point the CAP pulsed signal is automatically halted until a new concentration level is selected for a following treatment cycle.

a Experimental setup for implementing CAP real-time endpoint detection. b Live open circuit potentiometry for oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) value determination during CAP treatment of mice. c Live pulsed chronoamperometry in situ during treatment of mice for H2O2 concentration determination. Sampled data points on the response curve for three mice were used to determine the actual concentration at the given timestamp on the wound of mice 1–3 for in situ endpoint detection. d–f H2O2 concentration detected in each mouse, derived from the current curves depicted in panel (c). CAP endpoint detection sampled data points and trend line were used as guides for the eye (solid line) during treatment until threshold concentration value (based on baseline) was reached (dashed line) for mice 1–3. g–i PWM signal corresponding to the treatments. The CAP device stays ON (1) until the set threshold is reached during treatment time. Once the threshold value is reached, the CAP device turns OFF (0).

During CAP exposure, the sharp increase in concentration was followed by a slower, steady increase (~5 µM min−1) until the arbitrarily chosen 40 μM target concentration was reached at 270 s. Reaching the target concentration resulted in treatment termination, as shown by the pulse-width modulation (PWM) signal (Fig. 7c) indicating device activated (1) or deactivated (0). Because these real-time measurements differed from the static endpoint readings in PBS in a 24-well plate (Fig. 3b, c), they provided a more accurate representation of H2O2 diffusion dynamics during real-time in situ application. Reaching a concentration of ~40 µM in the well-plate experiments (Fig. 3c) was also shown to require ~300 s of treatment time, supporting the accuracy of this CAP endpoint detection approach.

Finally, the controller was tested for real-time, in situ operation and endpoint detection of CAP treatment in vivo (Fig. 8a). Figure 8b shows in situ real-time measurements of ORP during CAP treatment of excisional wounds in mice. ORP increased linearly with treatment time in a consistent and reproducible manner. H2O2 was detected using pulsed chronoamperometry to increase the signal-to-noise ratio for live measurements (Fig. 8c). The system was programmed to terminate CAP exposure based on H2O2 concentrations corresponding to the optimal therapeutic dose associated with smallest observed wound width and scar area. Due to variability in baseline and static endpoint H2O2 concentrations across animals (Fig. 5c), the setpoint was conservatively chosen from the lower quartile to avoid overexposure. The controller was configured to stop treatment once an increase of 25 µM was detected. In all cases, the system successfully terminated CAP treatment when the threshold was reached (Fig. 8d–i), demonstrating dose-based control in lieu of fixed treatment times. Specifically, the 25 µM increase was reached at 186.8 s for mouse 1 (Fig. 8d), 189.8 s for mouse 2 (Fig. 8e), and 151.8 s for mouse 3 (Fig. 8f). This adaptive approach helps account for inter-animal variability, environmental factors (e.g., humidity), and minor inconsistencies in CAP delivery (e.g., slight differences in treatment distance or wound topography). We expect that real-time, closed loop control of CAP delivery will facilitate safer, more effective, and precisely controlled CAP administration.

Discussion

We report in situ real-time detection and quantification of H2O2 and ORP during CAP treatment in vivo, followed by the successful implementation of a closed-loop feedback control system for endpoint detection. This work demonstrates the feasibility of using bio-electrochemical sensing as a means to guide and control CAP treatment in biomedical applications.

Defining a safe and effective CAP dose remains challenging because short treatment durations (seconds) lead to biological outcomes that may not be apparent until hours to days after the treatment. To address this, we developed a bio-electrochemical sensing platform with an integrated controller for real-time monitoring of H2O2 and ORP. The system enabled automated endpoint detection based on H2O2 changes. This system was validated in PBS, an in vitro scratch assay, and an in vivo murine wound model. While H2O2 is not the only effector produced by CAP, correlations between H2O2 measurements in situ and biological outcomes assessed hours to days later can serve as a framework to enable safe and effective CAP treatment.

Pre- and post-treatment measurements confirmed sensor suitability in all test beds. Real-time monitoring was applied in PBS and murine wounds but not in vitro, as CAP exposure times were shorter than sensor response time. As expected, CAP increased H2O2 and ORP in all systems in a dose-dependent manner45. Baseline H₂O₂ values were consistently higher in PBS containing HaCaT cells compared to cell-free PBS, likely due to endogenous H2O2 production41. This observation is consistent with previous work in Jurkat38 and Vero cells39. PBS on wound tissue showed higher baseline H2O2 concentrations than cell culture, reflecting greater cell density and cellular heterogeneity46. CAP application further upregulated mitochondrial H2O2, suggesting that post-treatment levels reflect a combination of CAP- and cell-generated H2O2. Notably, in vivo H2O2 increases exceeded those in PBS (40 µM vs. 10 µM between 60 and 180 s), likely due to tissue-specific oxidative responses and feedback between CAP and the treated biomaterial47.

ORP measurements captured the system’s net redox balance, integrating contributions from cells and extracellular fluids. Baseline ORP was lowest in the presence of cells or tissue. However, CAP-induced increases were greater in these conditions, indicating that CAP creates an increasingly more oxidative environment. These findings highlight the influence of the substrate (PBS, cells, or wound bed) on CAP-generated species and align with earlier studies in simpler liquid systems48,49. They also emphasize the importance of baseline measurements and data interpretation relative to the biomaterial treated under the exact same conditions.

While ORP sensors provided continuous data, H2O2 sensors were limited by interval-based response times due to physical absorption of the analyte. Response times were sufficient to enable real-time measurements in vivo, but improvements in sensor design could yield faster kinetics and longer-term operation. Although no stability or reusability issues were observed, extensive use of H2O2 sensors may degrade the Nafion permselective coating, reducing sensitivity. Similarly, Ag/AgCl reference electrodes may show stability loss with prolonged use. Addressing these limitations will be important for clinical translation.

Our in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that no single marker can fully define an optimal CAP dose. In vitro, MitoSox levels scaled with H2O2 and ORP, while cell counts and viability decreased at higher doses. Ki67 expression peaked at 10 s, corresponding to the most effective scratch closure, but showed similar values at 5 and 15 s, albeit from fewer cells in the 15 s samples. The insignificant difference in H2O2 between 10 and 15 s suggests that additional factors limit proliferation and overwhelm cellular repair mechanisms.

In vivo, CAP elicited a biphasic response. A 60 s treatment reduced scar area without affecting wound width, 180 s reduced both, and 300 s delayed healing transiently and showed no improvement, indicating possible tissue damage. Ki67 expression showed a weak dose-dependent upward trend, possibly because Ki67 expression was evaluated after wound closure when cells were no longer in the proliferative phase of healing. The 180 s dose emerged as optimal, corresponding to in vivo H2O2 and ORP values of ~60 µM and ~100 mV, respectively. These values may serve as reference points for future control algorithms.

Because baseline values varied with biomaterial, control systems must account for both initial conditions and substrate properties. We therefore implemented a feedback controller that terminated CAP treatment once H2O2 increased by 25 µM above baseline, simulating a consistent plasma dose across conditions. This adaptive approach addressed biological variability more effectively than fixed exposure times. Alternatively, absolute thresholds could be applied to define safe exposure. Together, these strategies provide a path towards standardized, feedback-controlled CAP therapies.

Translation of this novel method to clinical applications will require addressing patient safety, sterilization, and long-term stability. Plasma applications like this will need to comply with IEC 60601-150, which specifies safety limits for allowable patient leakage currents (<100 µA under normal conditions, and <500 µA in single-fault conditions) or with DIN SPEC 9131551 which outlines requirements for reproducible plasma dose delivery and long-term device stability to avoid patient harm. Compliance with these values and guidelines is essential to demonstrate electrical and biological safety, facilitate regulatory approval, and ensure clinical adoption of this new methodology. In addition, incorporating microcontrollers and sensors requires further safety testing. Sterilization strategies will be critical, as autoclaving or chemical disinfection may damage the sensors. Studies regarding the long-term stability of the sensors within the reactive CAP environment need to be conducted to determine limitations. Alternatively, single-use sensors could be used to bypass the need for electrode sterilization and long-term durability. However, single-use sensors would likely increase the cost of each treatment.

In conclusion, this research establishes a path toward the development of standardized, adaptive, and personalized CAP therapies. Real-time monitoring of RONS during treatment will enhance safety, optimize efficacy, and increase reproducibility of CAP-based therapies. While these studies were focused on the use of CAP for wound healing, they also indicate the considerable potential for extending sensor-based CAP control into CAP therapies for other conditions, such as cancer and virus infections.

Methods

CAP device and controller design

A controlled CAP device was developed for real-time analyte monitoring during CAP treatments under both in vitro and in vivo conditions. An overview of the experimental setup is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. CAP was generated using a volume dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) electrode consisting of a 7.5 mm diameter copper rod encased in a 2 mm aluminum oxide (Al2O3) dielectric (Kyocera 201-11010-0150, OD: 10 mm, ID: 8 mm, length: 15 mm). The electrode was driven by a custom-built, microsecond-pulsed power supply based on prior designs52,53, operating at 20 kVpp, 20 mApp, with a fixed 300 Hz repetition frequency. The device delivered ~0.6 W per pulse.

Power was supplied via an external DC power supply (Keithley 2260B-800-1, 600 VDC, 360 W). Voltage/current measurements were captured using a high-voltage probe (Tektronix P6015A) and a current transformer (Pearson 6585), interpreted through an oscilloscope (Tektronix MSO64). An arbitrary function generator (Tektronix AFG3052C, 50 MHz, 2 Channel, 1 GS/s) initially served as the pulsing input for the power supply. As the device was refined, a Texas Instruments microcontroller (MSP-EXP430FR2355) was designed and implemented to serve as a pulsing input and a detection and control platform for real-time detection of CAP-generated reactive species. Twin setups were used across test sites (NCSU and DU) for reproducibility.

Data acquisition and microcontroller integration

Sensor data were acquired using either an Anapot EIS potentiostat (Zimmer & Peacock, ZP1000080, Norway), PalmSens potentiostat (PalmSens4, the Netherlands), or a custom designed 16-bit Texas Instruments MSP-430FR2355 microcontroller unit (MCU). The MCU featured 12-bit analog-to-digital converters (ADC), low-pass filters (cutoff: 159.15 Hz), onboard pulse width modulation (PWM) control, and universal asynchronous receiver/transmitter (UART) serial logging via Termite 3.9 (CompuPhase, the Netherlands). Data export and analysis were facilitated using custom Python scripts for the MCU and PSTrace 5.9 (PalmSens BV, the Netherlands) for the Anapot EIS, and PalmSens potentiostats. Programming of the MCU was performed in C and Assembly and was compiled via Code Composer Studio.

Analyte detection and bio-electrochemical wire sensors

Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and oxidation reduction potential (ORP) were measured using commercially available non-enzymic wire sensors (Zimmer & Peacock ZPS WIR-000-00163, Norway). Each sensor’s working electrode (WE) consisted of an inert metal alloy of 70% platinum and 30% iridium so that repeatable measurements could be achieved without loss of catalytic properties when exposed to an abundance of CAP generated species. Each WE measured 2.0 ± 0.50 mm in length, and 0.5 ± 0.05 mm in width. The H₂O₂ sensor was covered with a layer of silicone and an analyte-selective layer of Nafion to ensure the selectivity of H₂O₂. Nafion’s unique characteristic as a cation-ion exchange polymer provided the membrane with the ability to selectively filter larger molecules and charged species, like redox-active ions, which could otherwise interfere with the H₂O₂ measurement.

The ORP wire sensors remained non-functionalized, since measurements could be made without a selective membrane layer on the WE. The reference electrode (RE) for each sensor was comprised of a copper wire with a layer of Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) paste to facilitate reproducibility and help maintain a stable reference voltage. Each RE measured 5.0 ± 1.00 mm in length, and 0.67 ± 0.20 mm in width. Both electrodes were separated by an insulative layer of polyolefin-based tubing which enclosed the RE. A final layer of heat shrink insulation covered the Ag/AgCl sealed RE and WE connection. The RE remained shielded by the Ag/AgCl layer with 5 mm exposed, and 2 mm of the WE left exposed to directly react with the targeted analyte. The sensors rely on electrochemical redox reactions through physical absorption of a liquid sample. In these studies, CAP treatments were conducted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Corning Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA), cell cultures, and animal wounds, supplemented with 500 µL and 50 µL of PBS, respectively. H₂O₂ and ORP readings were interpreted as chronoamperometric (Supplementary Fig. 6a) and potentiometric response curves (Supplementary Fig. 6c), respectively, reaching equilibrium within 20 ± 10 s.

Static sensor measurements

Two independent experiments were performed for each sensor type (H₂O₂, ORP). H₂O₂ and ORP sensors were submerged in 500 µL of PBS without calcium and magnesium (21-040-CV, Corning) within 24-well plates before and after CAP treatment. Readings were collected for 120 s and performed in triplicate. Sensors were removed from the solution, rinsed with biosensor rinse solution (ZPCH 900-000-00455), and then dried thoroughly before beginning the next treatment. Following drying of the sensors, a 60 s interval was consistently observed to ensure any ROS byproducts from the previous tests would not impede readings. Electrical interference testing was conducted to ensure the operating voltages between two sensors would not have electrical interference when operated simultaneously within the same bulk solution. No discernable change or offset in voltage or current readings were detected during CAP treatment or without it.

In vitro: Following the scratch procedure on HaCaT keratinocyte monolayers, the plate was washed twice and supplemented with 500 µL PBS. The sensors were submerged directly into the well, and baseline levels of H₂O₂ or ORP were recorded. The cells were then exposed to CAP, and the second measurement was taken immediately afterwards.

In vivo: Following wounding of the mice, a silicone wound splint with suture sites was placed on the wound bed to house and position the electrochemical wire sensors directly on the wound tissue. PBS (50 µL) was then applied to the wound with sensors submerged horizontally into the PBS solution. Baseline levels of H₂O₂ and ORP were recorded. The mice were then treated with CAP and the second measurement was taken immediately afterwards. Sensors were removed immediately after treatment and measurement.

CAP endpoint detection

Endpoint detection was performed using H₂O₂ sensors submerged in 500 μL PBS on a microscope slide during CAP treatment. The sensor was suspended inside the PBS solution horizontally by minimally disrupting the surface tension of the liquid on the slide. A target Η2O2 concentration (40 μΜ) was set via the graphical user interface (GUI) of the MCU. Baseline readings were taken for 20 s. CAP treatment started autonomously and continued until the desired concentration level was reached. Onboard diagnostics processed current readings into concentration values within 10 ms, with updates every 20 s, in agreement with the diffusion-limited response time of the sensors. Electrical interference testing was again performed to ensure electrical interference would not occur when the operating voltage was supplied by the MCU rather than a commercial testing platform. No change or offset was detected when operated by the MCU for either voltage or current during CAP treatment or without it, in comparison to sensors readings with a single sensor.

In vivo: Following wounding of the mice, a silicone wound splint with suture sites was placed on the wound bed to house and position the electrochemical wire sensors directly on the wound tissue. PBS (50 µL) was then applied to the wound with sensors submerged horizontally into the PBS solution. Baseline levels of H₂O₂ and ORP were recorded. CAP treatment started autonomously and continued until the desired concentration level was reached. On board diagnostics processed current readings into concentration values within 10 ms with updates every 20 s in agreement with the diffusion-limited response time of the sensors.

Electrochemical techniques

Chronoamperometry

H₂O₂ wire sensors (Zimmer & Peacock ZPS-HPE-003-00260, Norway) were operated at 0.65 V (Edc), with 1 s sampling rate, and a 10 nA to 1 μA detection range. H₂O₂ was oxidized at a Pt/Ir working electrode, where the reaction:

occurred and caused a current signal due to the transfer of electrons. Data points were sampled within the 20 s sampling interval following insertion of the sensor into the solution. The limit of detection (LOD) for the H₂O₂ wire sensors was 0.5 µM in PBS. The sensors’ available working electrode surface area and thickness of the Nafion diffusion barrier limited flux at low concentrations but improved sensor stability and selectivity under repeated plasma exposures. Baseline noise was ~1 nA. The measured sensitivity from calibration curves was 12 nA µM−1. Based on this noise-to-slope ratio, the effective resolution was ~0.1 µM. The calibration curve was linear from 0.5 to 200 µM, above which responses deviated from linearity.

Pulsed chronoamperometry

Pulsed chronoamperometry, a variation of chronoamperometry, was used for in situ endpoint detection-based experiments to improve signal-to-noise ratio and re-initiate redox reactions. Power to the sensors was pulsed at intervals matching the diffusion-limited sensor response time (~20 s)54,55.

Open circuit potentiometry

ORP wire sensors (Zimmer & Peacock ZPS-ORP-003-00258, Norway) measured the potential difference between a Pt/Ir working electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode under open-circuit conditions. A sampling rate of 1 s was used. Data points were collected within a 20 s sampling interval following insertion of the sensor into solution. The ORP sensor performance was defined by millivolt resolution and stability rather than a concentration-based LOD. The sensors exhibited a resolution of ~1 mV and a dynamic range of –500 to +500 mV. Calibration in ferri/ferrocyanide standards produced step changes consistent with a Nernstian response of 59 mV per decade concentration change.

Cyclic voltammetry

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed to establish the standard operating voltage (Edc) required for the electrochemical and redox reactions needed for measurement of H₂O₂ in PBS. CV analysis found that the sensor most effectively operated at 0.65 V by evaluating the oxidation peak of the cyclic voltammogram produced. CV analysis also ensured the selected operating voltage was conducive to exclusively measuring H₂O₂ by selecting a voltage range low enough to avoid higher-voltage regions where other plasma-generated reactive species (e.g., nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrie) could be detected.

Sensor calibration

H₂O₂ sensors were calibrated with serial dilutions (0–10 μM) in PBS from a 30% stock solution of H₂O₂, producing a stepwise current curve (Supplementary Fig. 6a). A linear standard curve was then produced for the defined concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 6b). ORP sensors were calibrated using ferrocyanide (Fe²⁺) (Zimmer & Peacock ORP calibration kit ZP1001687) dilutions (0–10 mM), creating a decreasing step-function response curve (Supplementary Fig. 6c). The redox reaction of ferrocyanide/ferricyanide, [Fe(CN)6]3− + e− ↔ [Fe(CN)6]4−, was used as the calibration reaction for defining each step in the voltage response curve. A linear standard curve (Supplementary Fig. 6d) was then produced for the defined concentrations. Using the Nernst equation (Eq. (2)), voltage response was correlated to redox status:

Sensor maintenance and calibration checks

Each sensor type was calibrated in PBS before and after testing (static and endpoint detection), as well as before and after each experiment (in vitro and in vivo). Calibration checks were performed to ensure accurate concentration values (H₂O₂) and potential stability (ORP) following repeated CAP exposures across treatments. All calibration results were consistently within similar or acceptable tolerances relative to established standard curves. The H₂O₂ sensors demonstrated reproducibility within 5% relative standard deviation (RSD) across calibration checks, while ORP sensors exhibited 2% RSD, corresponding to baseline variability of only a few millivolts.

To prevent photodegradation of the Nafion selective membrane coating and Ag/AgCl reference electrodes, sensors were stored at 3–5 °C and 30–50% relative humidity in a light-restricted environment between and after experiments. Following each test, sensors were rinsed with DI water, gently dried with Kimtech wipes for 30 s, and then allowed to air-dry for 60 s to minimize Nafion aging or viscosity related changes that could impact sensitivity.

Cell culture and scratch assay

HaCaT human keratinocytes (AddexBio Technologies, San Diego, CA)56 were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Corning Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (DMEM10). Cells were incubated at 37 °C and in 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) with 95% relative humidity and passaged every 3–4 days.

HaCaT keratinocytes were seeded into 24-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well in 500 µL DMEM10 and grown to confluency (48 h). 24 h prior to scratch assay and CAP application, confluent monolayers were washed with PBS and incubated in FBS-free DMEM at 37 °C and 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) with 95% relative humidity.

HaCaT monolayers were washed twice and supplemented with PBS prior to the scratch assay. The Agilent Autoscratch (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to produce identical scratches across the center of the well. Cells were washed once with PBS and exposed to CAP using one of three doses: suboptimal (5 s), optimal (10 s), or excessive (15 s). Immediately after CAP exposure, 500 µL of FBS-free DMEM was added to each well, and images of the cells were taken at 4× magnification using high contrast brightfield channels on Agilent Cytation 5 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The plate was incubated at 37 °C and 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) with 95% relative humidity for 24 h to allow for scratch closure. After 24 h, the plate was washed and re-imaged at 4× magnification.

Scratch closure was automatically calculated by BioTek Gen5 analysis software (version 3.11) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using the following formula:

where Wt is the average wound width in μm, over time; Ia is the total area of the 4× image; Object sum area (OSAt) is the area covered by cells at each time point, and Ih is the height of the 4× image.

Viability assay

At 24 h post-CAP exposure, HaCaT keratinocytes were stained with 1 mg mL−1 Propidium Iodide (PI) (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) in PBS. Images were taken at 4× magnification using the brightfield and PI channels on Agilent Cytation 5. The Gen5 program (version 3.11) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to quantify the total cells and cells positive for PI to calculate percent viability.

Cellular oxidative stress assay

Live HaCaT keratinocytes were pre-stained with 5 mM MitoSOX red superoxide indicator (Thermofisher Scientific, Philadelphia, PA) for 20 min in the dark at room temperature. Stained cells were exposed to CAP and immediately imaged using 4× magnification on the Agilent Cytation 5 using brightfield and PI channels. The Gen5 program (version 3.11) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to quantify total cells and cells positive for MitoSOX, via PI channel, to calculate the percentage of MitoSOX positive cells.

Cellular proliferation assay

HaCaT keratinocytes were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde 24 h post-CAP exposure and permeabilized with 90% methanol. They were then stained with Alexa Fluor 488 anti-human Ki67 antibody (1:500) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) and Hoechst 33342 (1:2000) nuclear acid stain (Thermofisher Scientific, Philadelphia, PA). The center of each well was imaged at 4× magnification on the Agilent Cytation 5 using brightfield, GFP (Ki67), and DAPI (Hoechst 33342) channels. The Gen5 program (version 3.11) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to quantify total cells and the number of cells positive for Ki67 expression to calculate percent Ki67+ cells.

Animal studies and ethics

Animal studies were conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #201702583) at Rutgers University. Male 9-week-old mice (BALB/c, Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA, USA) were acclimated to standard laboratory conditions (5 mice/cage) for one week before performing the surgery in a standard controlled environment (72 ± 2 °F and 30–70% humidity). A 12:12 (light/dark) cycle was implemented, and mice were provided a standard diet (PMI Nutrition International, Brentwood, MP) and water ad libitum. Twenty-four hours prior to the surgery, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Henry Schein, USA) inhalation at 5% v/v for induction and maintained at 2.5% v/v thereafter. The dorsal region was shaved using an electric clipper, followed by the application of Nair™ cream to remove any residual hair. The mice were then returned to housing, but in individual cages, with continued access to food, water, and two standard forms of enrichment.

On the day of surgery, mice were anesthetized as described above. Artificial tear cream was applied to the corneas to prevent eye dehydration. Ethiqa XR (3.25 mg kg−1 once for 72 h) was subcutaneously injected for pre-emptive pain management. The wound site was sterilized by alternating applications of Betadine scrub and 70% ethanol three times. A full-thickness excisional wound was created on the dorsum of each mouse using a 10 mm diameter biopsy punch. For the acute sensor study, a silicone wound splint with suture sites (Grace Bio-Labs, OD: 14 mm, ID: 0.5 mm) was placed on the wound bed to house and suspend the electrochemical wire sensors directly atop the wound tissue. 50 µL of PBS was then applied to the wound bed to ensure the sensors were immersed in liquid. Sensor readings were recorded immediately pre- and post-CAP treatment (Fig. 5). Mice were randomly assigned (n = 3 mice pergroup) to receive CAP treatment durations of 60 s, 180 s, and 300 s, or no CAP treatment at all, to be used as control. Immediately after post-CAP treatment, the sensors and the wound stint were removed. Mice were then sacrificed immediately after sensor measurements.

For the wound healing study (n = 8–9 mice per group), mice were randomized into the same treatment groups as for the sensor studies. Immediately after treatment, 50 µl of PBS was applied to the wound site to prevent dehydration. The wounds were covered with Tegaderm™ (3 M) to protect the wound environment. Photographs of the wounds were taken on the day of surgery (day 0) and on days 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 post-wounding to monitor healing progress. The wound images were digitally analyzed to determine the percent wound closure at each time point, using the following formula:

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Twenty-one days post-wounding, mice were euthanized using carbon dioxide inhalation in accordance with AVMA guidelines on euthanasia. Skin wound samples, including the scar area, were harvested and fixed in 10% formalin shaking for >72 h. The skin samples were then processed for histological analysis at Rutgers Research Pathology Services. The collected tissue samples were paraffin-embedded and sectioned into 5 μm thick slices. The sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for general tissue morphology visualization and Masson’s Trichrome Stain to evaluate collagen deposition. Tissues were also stained by immunohistochemistry for Ki67 (a marker for proliferating cells, reflecting cell proliferation activity), CD31 (a marker for blood vessels that indicates angiogenesis), and α-SMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin; to assess myofibroblast activity, wound contraction, and tissue remodeling). Images were captured using a light microscope (ECHO). Epidermal and dermal thicknesses were measured using ImageJ software (NIH). A custom Python script segmented stained areas using red-channel intensity to quantify positive staining as a percentage of total tissue.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was performed in OriginPro 2025 (OriginLab Corporation, USA). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used, unless stated otherwise. p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001). All exact p values are provided in Supplementary Data 1. All experiments were conducted with at least 3 independent experiments. To assess reproducibility of the sensor measurements, single bar plots for each well are provided exemplarily for the 180 s treatment in Supplementary Fig. 2a for H2O2 and Supplementary Fig. 2c for ORP.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the results in this study are available within the paper and its supplemental material. The source data for graphs is provided in Supplementary data 1. The raw datasets generated during the study are available for research purposes from the corresponding author K.S. upon reasonable request.

References

Laroussi, M. et al. Low-temperature plasma for biology, hygiene, and medicine: perspective and roadmap. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 6, 127–157 (2022).

Stratmann, B. et al. Effect of cold atmospheric plasma therapy vs standard therapy placebo on wound healing in patients with diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 3, e2010411 (2020).

Von Woedtke, T., Laroussi, M. & Gherardi, M. Foundations of plasmas for medical applications. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 31, 054002 (2022).

Graves, D. B. The emerging role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in redox biology and some implications for plasma applications to medicine and biology. J. Phys. D 45, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/45/26/263001 (2012).

Sen, C. K. & Roy, S. Redox signals in wound healing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 1348–1361 (2008).

Dunnill, C. et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and wound healing: the functional role of ROS and emerging ROS-modulating technologies for augmentation of the healing process. Int. Wound J. 14, 89–96 (2017).

Lynn, S. A., MacGearailt, N. & Ringwood, J. V. Real-time virtual metrology and control for plasma etch. J. Process Control 22, 666–676 (2012).

Ma, L. et al. Cold Atmospheric Plasma for Burn Healing in Mice. In IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 1–1 (IEEE, 2025)

Woelfel, C. et al. Control-oriented plasma modeling and controller design for reactive sputtering. IFAC J. Syst. Control 16, 100142 (2021).

Goodlin, B. E., Boning, D. S. & Sawin, H. H. Quantitative analysis and comparison of endpoint detection based on multiple wavelength analysis. In Proc. 201st Meeting of the Electrochemical Society, International Symposium on Plasma Processing XIV, Abs Vol. 415 1–30 (2002).

Hirobe, K. & Tsuchimoto, T. End point detection in plasma etching by optical emission spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 127, 234 (1980)

Cho, K., Shao, K. & Mesbah, A. Run-indexed time-varying Bayesian optimization with positional encoding for auto-tuning of controllers: Application to a plasma-assisted deposition process with run-to-run drifts. Comput. Chem. Eng. 185, 108653 (2024).

Gidon, D., Pei, X., Bonzanini, A. D., Graves, D. B. & Mesbah, A. Machine learning for real-time diagnostics of cold atmospheric plasma sources. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 3, 597–605 (2019).

Gidon, D. et al. Data-driven LPV model predictive control of a cold atmospheric plasma jet for biomaterials processing. Control Eng. Pr. 109, 104725 (2021).

Bonzanini, A. D., Paulson, J. A., Graves, D. B. & Mesbah, A. Toward safe dose delivery in plasma medicine using projected neural network-based fast approximate NMPC. In IFAC-PapersOnLine vol. 53, 5279–5285 (Elsevier B.V., 2020).

Jablonowski, H. et al. Characterization and comparability study of a series of miniaturized neon plasma jets. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 57, 195202 (2024).

Copeland, A. & Lytle, D. A. Measuring the oxidation-reduction potential of important oxidants in drinking water. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 106, 10–20 (2014).

Ercan, U. K., Özdemir, G. D., Özdemir, M. A. & Güren, O. Plasma medicine: The era of artificial intelligence. Plasma Processes Polym. 20, e2300066 (2023).

Giannoudi, L., Piletska, E. V. & Piletsky, S. A. Development of biosensors for the detection of hydrogen peroxide. In Biotechnological Applications of Photosynthetic Proteins: Biochips, Biosensors and Biodevices 175–191 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 2006) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-36672-2_16.

Zamfir, L. G. et al. Non-enzymatic polyamic acid sensors for hydrogen peroxide detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 226, 525–533 (2016).

Parrilla, M., Cánovas, R. & Andrade, F. J. Enhanced potentiometric detection of hydrogen peroxide using a platinum electrode coated with nafion. Electroanalysis 29, 223–230 (2017).

Chen, X., Wu, G., Cai, Z., Oyama, M. & Chen, X. Advances in enzyme-free electrochemical sensors for hydrogen peroxide, glucose, and uric acid. Microchim. Acta 181, 689–705 (2014).

Shinwari, M. W. et al. Microfabricated reference electrodes and their biosensing applications. Sensors 10, 1679–1715 (2010).

Yonemori, Y., Takahashi, E., Ren, H., Hayashi, T. & Endo, H. Biosensor system for continuous glucose monitoring in fish. Anal. Chim. Acta 633, 90–96 (2009).

Pundir, C. S., Deswal, R. & Narwal, V. Quantitative analysis of hydrogen peroxide with special emphasis on biosensors. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 41, 313–329 (2018).

Grieshaber, D., Mackenzie, R., Vörös, J. & Reimhult, E. Electrochemical biosensors-sensor principles and architectures. Sensors 8, 1400–1458 (2008).

Søpstad, S. Flexible Electrochemical Sensor Platform. Dissertation, University of South-Eastern Norway, Horten, Norway (2019).

Girard-Sahun, F. et al. Reactive oxygen species generated by cold atmospheric plasmas in aqueous solution: successful electrochemical monitoring in situ under a high voltage system. Anal. Chem. 91, 8002–8007 (2019).

Khudaish, E. A. The Electrochemical Oxidation Of Hydrogen Peroxide On Platinum Electrodes At Phosphate Buffer Solutions. Dissertation, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand (1999).

Lee, Y. A., Lee, I., Kim, H. J. & Kim, H. W. Smart strategic management for the cold plasma process using orp monitoring and total organic carbon correlation. Processes 12, 471 (2024).

Ma, R. et al. Effect of non-thermal plasma-activated water on fruit decay and quality in Postharvest Chinese Bayberries. Food Bioproc. Tech. 9, 1825–1834 (2016).

Nasri, Z. et al. Development of an electrochemical sensor for in-situ monitoring of reactive species produced by cold physical plasma. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 326, 129007 (2021).

Atayik, M. C. & Çakatay, U. Redox signaling in impaired cascades of wound healing: promising approach. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 6927–6936 (2023).

Olekson, M. P., Faulknor, R. A., Hsia, H. C., Schmidt, A. M. & Berthiaume, F. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products improves stromal cell-derived factor-1 activity in model diabetic environments. Adv. Wound Care 5, 527–538 (2016).

Bekeschus, S., von Woedtke, T., Emmert, S. & Schmidt, A. Medical gas plasma-stimulated wound healing: Evidence and mechanisms: mechanisms of gas plasma-assisted wound healing. Redox Biol. 46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2021.102116 (2021).

Bjugstad, K. B. et al. Oxidation-reduction potential as a biomarker for severity and acute outcome in traumatic brain injury. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 6974257 (2016).

Taheri, D. et al. Realtime RONS monitoring of cold plasma-activated aqueous media based on time-resolved phosphorescence spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 14, 22403 (2024).

Mohamed, H. et al. Differential effect of non-thermal plasma rons on two human leukemic cell populations. Cancers 13, 2437 (2021).

Sutter, J. et al. Inclusion of biological targets in the analysis of electrical characteristics of non-thermal. Plasma Disch. Plasma 6, 577–591 (2023).

Sutter, J., Bruggeman, P. J., Wigdahl, B., Krebs, F. C. & Miller, V. Manipulation of oxidative stress responses by non-thermal plasma to treat herpes simplex virus type 1 infection and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054673 (2023).

Balzer, J. et al. Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) differently affects migration and differentiation of keratinocytes via hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide-related products. Clin. Plasma Med. 13, 1–8 (2019).

Sampaio, A. et al. Effect of the pH on the antibacterial potential and cytotoxicity of different plasma-activated liquids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 13893 (2022).

Saedi, Z. et al. Stable and efficient microbubble-enhanced cold plasma activation for treatment of flowing water. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 40, e00887 (2024).

Shen, J. et al. Bactericidal effects against S. aureus and physicochemical properties of plasma activated water stored at different temperatures. Sci. Rep. 6, 28505 (2016).

Yan, D. et al. The strong cell-based hydrogen peroxide generation triggered by cold atmospheric plasma. Sci. Rep. 7, 10831 (2017).

Van Der Vliet, A. & Janssen-Heininger, Y. M. W. Hydrogen peroxide as a damage signal in tissue injury and inflammation: murderer, mediator, or messenger? J. Cell Biochem. 115, 427–435 (2014).

Stapelmann, K., Gershman, S. & Miller, V. Plasma-liquid interactions in the presence of organic matter—a perspective. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 160901 (2024).

Ranieri, P. et al. GSH modification as a marker for plasma source and biological response comparison to plasma treatment. Appl. Sci. 10, 2025 (2020).

Stapelmann, K., Myers, B., Quesada, M. H., Lenker, E. & Ranieri, P. J. Following O and OH in He/O2 and He/H2O gas mixtures - from the gas phase through the liquid phase to modifications on a biological sample. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 54, 434003 (2021).

Commission, I. E. Medical electrical equipment-Part 1: general requirements for basic safety and essential performance. IEC 60601-1, 2005 (2005).

Hahn, V., Brandenburg, R. & von Woedtke, T. DIN SPEC 91315: a first attempt to implement mandatory test protocols for the characterization of plasma medical devices. In Comprehensive Clinical Plasma Medicine: Cold Physical Plasma for Medical Application (eds. Metelmann, H.-R., von Woedtke, T. & Weltmann, K.-D.) 511–516 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67627-2_35.

Rajasekaran, P. et al. Characterization of dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) on mouse and histological evaluation of the plasma-treated tissue. Plasma Process. Polym. 8, 246–255 (2011).

Rajasekaran, P. et al. Filamentary and homogeneous modes of dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) in air: Investigation through plasma characterization and simulation of surface irradiation. Plasma Process. Polym. 7, 665–675 (2010).

Komkova, M. A. et al. Pulse power generation chronoamperometry as an advanced readout for (bio)sensors: application for noninvasive diabetes monitoring. Anal. Chem. 95, 7528–7535 (2023).

de Oliveira, F. M., Da Silva, L. M. & dos Santos, W. T. P. Double-pulse chronoamperometry using short times for the kinetic study of simple quasi-reversible electrochemical reactions at low overpotentials. J. Electroanal. Chem. 848, 113291 (2019).

Boukamp, P. et al. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J. Cell Biol. 106, 761–771 (1988).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01EB029705. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank Zimmer & Peacock for their contributions to this paper regarding training and use of wire sensors, as well as calibration and data curating techniques for the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S., F.B., F.K., and V.M. designed and conceptualized the study. J.E.T. designed, constructed, and characterized the CAP device and the microcontroller with help from K.P. and J.R. V.M. and F.K. designed and conceptualized the in vitro studies. J.S. and G.K. performed in vitro experiments and helped with in vivo studies. F.B. and S.K. designed and conceptualized the in vivo experiments. S.K. was responsible for data curation for in vivo experiments with help from D.P. and S.M. G.K. and J.E.T. collected in vitro and in vivo sensor data. J.E.T. performed all sensor data analysis. Writing - Original draft was prepared by J.E.T and K.S. Review and editing was performed by V.M., F.B., S.K., F.K., G.K., J.E.T., and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Cecilia de Carvalho Castro Silva] and [Philip Coatsworth]. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, J.E., Kumar, S., Karkada, G. et al. Electrochemical sensors for in situ monitoring of reactive species during cold atmospheric plasma-based therapies. Commun Eng 5, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00560-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00560-w

This article is cited by

-

Electrochemical Detection of NO and Ca2+ during Cold Atmospheric Plasma Treatment of Acute Wounds: Sensor Selectivity and Stability in the Plasma-Bio-System

Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing (2026)