Abstract

Psychological characteristics are associated with varying dementia risk and protective factors. To determine whether these characteristics aggregate into psychological profiles and whether these profiles differentially relate to aging health, we conducted a cross-sectional investigation in two independent middle-aged (51.4 ± 7.0 years (mean ± s.d.); N = 750) and older adult (71.1 ± 5.9 years; N = 282) cohorts, supplemented by longitudinal analyses in the former. Using a person-centered approach, three profiles emerged in both cohorts: those with low protective characteristics (profile 1), high risk characteristics (profile 2) and well-balanced characteristics (profile 3). Profile 1 showed the worst objective cognition in older age and middle age (at follow-up), and most rapid cortical thinning. Profile 2 exhibited the worst mental health symptomology and lowest sleep quality in both older age and middle age. We identified profile-dependent divergent patterns of associations that may suggest two distinct paths for mental, cognitive and brain health, emphasizing the need for comprehensive psychological assessments in dementia prevention research to identify groups for more personalized behavior-change strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The rapid growth of the aged population poses a substantial global social and economic challenge. Mental, cognitive and brain health are affected in aging, with over 20% of adults aged 60+ years living with a psychiatric or neurological disorder, including dementia1. Indeed, the prevalence of dementia is predicted to more than double over the next 20 years2. In this context, promoting healthy life years, which includes maintaining mental health and preventing age-related cognitive decline, is critical. Research urgently needs to identify modifiable factors that impact healthy aging and dementia risk, and the mechanisms through which they act, to advance early interventions for prevention. Targeting mid-to-older adults, before the extensive accumulation of neuropathology and impairment, is vital3.

The Lancet Commission on dementia prevention identified 14 potentially modifiable factors that affect dementia risk3. While eliminating these risk factors (for example, smoking, physical inactivity, social isolation) could theoretically prevent or delay up to 45% of dementias, deepening the search for factors underpinning some of these largely physical and behavioral risks will generate greater opportunity for dementia risk reduction and healthier aging.

Recent research has begun to identify psychological characteristics that are associated with increased risk of, or protection from, cognitive decline, neurodegeneration and clinical dementia4. Repetitive negative thinking5,6,7, proneness to experience distress8 (also known as neuroticism) and perceived stress9 are associated with increased risk, whereas protective characteristics include having a sense of life-purpose10 or coherence11, self-reflection12 and dispositional mindfulness13.

Up to now, psychological risk and protective factors have almost exclusively been examined independently. This approach is limiting, because psychological characteristics do not exist in isolation. It is important to understand whether psychological characteristics aggregate into different profiles and how these aggregations relate to markers of aging and dementia risk, as this knowledge could aid in the development of targeted interventions and preventive strategies. For example, are high levels of psychological risk factors more strongly associated with age-related brain and cognitive measures than lower levels of protective psychological features?

This research requires the use of person-centered approaches to identify the latent psychological profiles of individuals14. This approach contrasts with the more widely used variable-centered approach, which examines the relationships between two or more variables in a given sample. Although useful to help understand how these variables relate to each other, variable-centered approaches are unable to holistically account for interacting characteristics that may influence outcomes15. Person-centered approaches create groups of individuals (persons) based on the similarity of their responses to the variables, so that people with similar characteristics are grouped together into a profile. These profiles can then be used to examine their relationships with different outcome measures.

Our study uses a person-centered approach using latent profile analysis (LPA) to uncover hidden patterns of psychological characteristics within individuals. By identifying distinct psychological profiles and examining their associations with multimodal markers of dementia risk, we aim to elucidate how various combinations of psychological characteristics relate to mental, cognitive and brain health. This methodology allows us to move beyond traditional variable-centered approaches, offering a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between psychological characteristics and aging-related outcomes.

The objectives of the present study were twofold: (1) to use LPA to investigate whether individual psychological characteristics associated with dementia risk or protection aggregate into similar psychological profiles in two independent cohorts of cognitively unimpaired middle-aged and older adults, and (2) to examine the associations of such putative profiles with mental health, cognition, brain integrity measured via cortical thickness, and engagement in other lifestyle-related behaviors associated with dementia risk, as well as with measures of cognitive change and brain atrophy over time.

Results

Participant characteristics

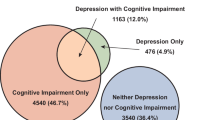

A total of 823 cognitively unimpaired participants from the Barcelona Brain Health Initiative (BBHI; including n = 750 with baseline mental, cognitive and/or brain health data and n = 533 with both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cognitive data at follow-up) and 282 cognitively unimpaired participants from the Medit-Ageing study were included. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each cohort are provided in Table 1. The BBHI cohort were younger (51.4 ± 7.0 versus 71.1. ± 5.9 years (mean ± s.d.); W = 10,331, P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) and included a larger proportion of men (48.5% versus 36.9%; χ2 = 11.60, P < 0.001, chi-squared test) than the Medit-Ageing cohort.

Latent profile identification

The model fit statistics for the LPA, conducted separately in BBHI and Medit-Ageing, are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The Vuong–Lo–Medell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR-LRT) became non-significant for the four-profile solution in both samples, indicating that a three-profile solution was the best fitting. Increasing the number of profiles resulted in small class sizes (<5% of the total sample), alongside poorer fit in many of the other metrics, supporting three profiles as the most robust solution.

As shown in Fig. 1, we found three distinct profiles in both cohorts that demonstrated comparable aggregations of psychological characteristics. Compared to the other profiles, profile 1 was characterized by lower levels of positive or protective psychological characteristics, profile 2 by higher negative or psychological risk characteristics, and profile 3 by moderately high protective and moderately low risk characteristics. We labeled the three profiles as follows: ‘low protective’ (profile 1: BBHI, n = 196, 26.1%; Medit-Ageing, n = 59, 20.9%), ‘high risk’ (profile 2: BBHI, n = 149, 19.9%; Medit-Ageing, n = 64, 22.7%) and ‘well-balanced’ (profile 3: BBHI, n = 405, 54.0%; Medit-Ageing, n = 159, 56.4%). Descriptive statistics for each profile, in both cohorts, are presented in Table 1.

BBHI and Medit-Ageing cross-sectional analyses

The results from linear regression models examining the cross-sectional associations between psychological profile membership and mental health, cognition, lifestyle and cortical thickness after adjusting for covariates (age, sex, education and (in Medit-Ageing) study) are described below, presented in Supplementary Table 2 and displayed in Figs. 2–4.

Raw data distributions of depression and anxiety by profile, with the white circles representing the estimated marginal means following adjustment for covariates (age, sex and years of education, as well as study group (for Medit-Ageing data)). The 95% confidence intervals are displayed as vertical black lines. Higher scores across all measures represent greater levels of depression and anxiety. Two-tailed linear regressions were performed to test for the effect of psychological profile group membership on depression (BBHI, N = 749, F2,746 = 63.6, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, N = 282, F2,275 = 24.6, P < 0.001) and anxiety (BBHI, N = 749, F2,746 = 131.8, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, N = 281, F2,274 = 71.9, P < 0.001). A significant main effect of psychological profile is represented by a bold horizontal line at the top of the graph, with pairwise differences displayed by thinner horizontal lines below. Precise P values for pairwise comparisons are reported in Supplementary Table 2. There were no corrections for multiple comparisons. DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 items; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; STAI-B, State and Trait Anxiety Inventory–Scale B; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Raw data distributions of objective cognition and subjective cognitive complaints by profile, with the white circles representing the estimated marginal means following adjustment for covariates (age, sex and years of education, and study group (for Medit-Ageing data)). The 95% confidence intervals are displayed as vertical black lines. Higher scores across all measures represent better objective cognition and greater levels of subjective cognitive complaints (the scores for the latter are inversed for visualization purposes). Two-tailed linear regressions were performed to test for the effect of psychological profile group membership on objective cognition (BBHI, N = 729, F2,723 = 7.2, P < 0.00; Medit-Ageing, N = 280, F2,273 = 8.0, P < 0.001) and subjective cognitive complaints (BBHI, N = 738, F2,732 = 60.1, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, N = 276, F2,269 = 21.0, P < 0.001). A significant main effect of psychological profile is represented by a bold horizontal line at the top of the graph, with pairwise differences displayed by thinner horizontal lines below. Precise P values for pairwise comparisons are reported in Supplementary Table 2. There were no corrections for multiple comparisons. For visualization purposes, scores of subjective cognitive complaints for the BBHI sample were inverted from those utilized in the statistical analyses, so that higher scores reflect more subjective cognitive complaints. McNair CDS, McNair Cognitive Difficulties Scale; Neuro-QoL, Quality of Life in Neuroradiological Disorders; PACC5Abridged, Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite 5 Abridged; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Raw data distributions of subjective sleep problems, loneliness, social network engagement and LIBRA scores by profile, with the white circles representing the estimated marginal means following adjustment for covariates (age, sex and years of education, and study group (for Medit-Ageing data)). The 95% confidence intervals are displayed as vertical black lines. Higher scores across all measures represent greater levels of subjective sleep problems and higher levels of loneliness; and higher social network and LIBRA scores indicate a larger social network and a greater dementia risk, respectively. Two-tailed linear regressions were performed to test for the effect of psychological profile group membership on subjective sleep problems (BBHI, N = 735, F2,697 = 42.1, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, N = 277, F2,270 = 15.4, P < 0.001), loneliness (BBHI, N = 703, F2,697 = 76.0, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, N = 277, F2,270 = 20.6, P < 0.001), social network engagement (BBHI, N = 738, F2,697 = 41.1, P < 0.001) and LIBRA scores (BBHI, N = 704, F2,698 = 15.7, P < 0.001). A significant main effect of psychological profile is represented by a bold horizontal line at the top of the graph, with pairwise differences displayed as thinner horizontal lines below. Precise P values for pairwise comparisons are reported in Supplementary Table 2. There were no corrections for multiple comparisons. Jenkins, Jenkins Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire; LIBRA, Lifestyle for BRAin health; LSNS, Lubben Social Network Scale; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; UCLA, University of California Loneliness Scale; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Mental health

In both BBHI and Medit-Ageing, psychological profile membership was associated with anxiety (BBHI, F2,746 = 63.6, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, F2,274 = 71.9, P < 0.001) and depressive (BBHI, F2,746 = 131.8, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, F2,275 = 24.6, P < 0.001) symptoms. Planned pairwise comparisons revealed that individuals in profile 2 exhibited significantly elevated levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms in comparison to those in profiles 1 and 3, in both cohorts. Furthermore, participants in Profile 1 had higher anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to those in profile 3 in both cohorts.

Cognition

Psychological profile membership was associated with a global cognitive composite sensitive to detecting and tracking preclinical Alzheimer’s disease-related decline (that is, the four-item ‘abridged’ Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite 5 (PACC5abridged)) in both BBHI (F2,723 = 8.0, P < 0.001) and Medit-Ageing (F2,273 = 12.7, P < 0.001). Although no statistically significant differences emerged in planned pairwise comparisons in BBHI, the pattern of findings closely resembled that of Medit-Ageing. In Medit-Ageing, individuals in profile 1 had significantly worse global cognitive function (that is, lower PACC5abridged scores) compared to those in profiles 2 and 3.

In addition to associations with objective cognition, psychological profile membership was related to subjective cognition in both BBHI (F2,732 = 60.1, P < 0.001) and Medit-Ageing (F2,269 = 21.0, P < 0.001). Individuals in profile 2 reported greater perceived subjective memory concerns compared to profile 3 individuals in both cohorts. Additionally, in BBHI, individuals in profile 2 reported more memory concerns than individuals in profile 1, while profile 1 individuals reported greater concerns than those in profile 3.

Following additional adjustment for anxiety and depressive symptoms in sensitivity analyses, objective and subjective cognition results remained largely unchanged (Supplementary Table 3).

Health and lifestyle

In BBHI, psychological profile membership was associated with health and lifestyle factors related to dementia risk, as captured by the late-life ‘Lifestyle for Brain Health’ composite (LIBRA; F2,698 = 15.7, P < 0.001). Planned pairwise comparisons revealed that individuals in profiles 1 and 2 had poorer health and lifestyles (that is, higher LIBRA scores) compared to those in profile 3.

Exploratory analyses revealed associations between psychological profile membership and the LIBRA constituent measures of cognitive activity, hypercholesterolemia, adherence to the Mediterranean diet and smoking. No pairwise differences were observed in relation to hypercholesterolemia and smoking; however, individuals in profiles 1 and 2 reported lower levels of cognitive activity and less adherence to the Mediterranean diet than individuals in profile 3 (Supplementary Table 4).

It was not possible to compute the LIBRA in Medit-Ageing. Instead, exploratory analyses were performed to examine the association between psychological profile membership and LIBRA components. Specifically, we focused on the components that were associated with psychological profile membership in BBHI and were also available in Medit-Ageing (that is, cognitive activity, adherence to the Mediterranean diet and smoking). Partially aligning with the findings from BBHI, psychological profile membership was associated with cognitive activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet, but not smoking. No pairwise differences were observed in relation to cognitive activity; however, individuals in profile 1 reported greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet than individuals in profiles 2 and 3.

The relationship between psychological profile membership and subjective sleep quality, loneliness and social network engagement—health and lifestyle factors associated with dementia risk but not captured by the LIBRA—were also examined. In both cohorts, analyses revealed associations between psychological profile membership and subjective sleep quality (BBHI, F2,697 = 42.1, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, F2,270 = 15.4, P < 0.001) and loneliness (BBHI, F2,697 = 76.0, P < 0.001; Medit-Ageing, F2,270 = 20.6, P < 0.001). Planned pairwise comparisons revealed that individuals in profile 2 had worse perceived sleep quality and higher levels of loneliness compared to those in profiles 1 and 3, in both cohorts. Furthermore, in BBHI, individuals in profile 1 also reported worse sleep quality and greater loneliness than those in profile 3. In BBHI, where social network engagement was also assessed, an association was observed with psychological profile membership (F2,697 = 41.1, P < 0.001), with planned pairwise comparisons indicating that participants in profiles 1 and 2 had smaller social network engagement in comparison to those in profile 3.

Following additional adjustment for anxiety and depressive symptoms in sensitivity analyses, all results remained largely unchanged (Supplementary Table 3).

Cortical thickness

In the BBHI sample, where MRI baseline data were available for 716 participants, psychological profile membership was not associated with differences in cortical thickness (as revealed by a vertex-wise general linear model conducted on FreeSurfer).

BBHI longitudinal analyses subsample

Both cognition and MRI data were obtained for 533 BBHI participants at a follow-up assessment (profile 1, n = 139, 26.1%; profile 2, n = 101, 18.9%; profile 3, n = 293, 55.0%). Over an average follow-up period of 2.3 years (range, 0.7 to 3.4 years), there were no differences in attrition rates across psychological profiles (χ2 = 1.2, P = 0.540). Compared to the total BBHI sample, individuals with longitudinal data were on average older (T381 = 2.2, P = 0.029, t-test), but did not differ in relation to the proportion of women (χ2 = 0.1, P = 0.765) or education level (T342 = 0.4, P = 0.726).

As a sensitivity check, all baseline cross-sectional analyses were re-conducted in the BBHI subsample with longitudinal data (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). The results mirrored those for the entire sample, showing baseline associations between psychological profile membership and mental health, cognition and lifestyle factors. Planned pairwise comparisons within the BBHI subsample remained largely consistent with the full sample, revealing that profile 1 membership was associated with the lowest levels of objective cognition, poorest health and lifestyle as measured by the LIBRA, and the smallest social network. Also, individuals in profile 2 exhibited the highest levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness, subjective cognitive concerns and the worst perceived sleep quality (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). In addition, we did not observe differences in cortical thickness.

Longitudinal findings

Cognition

During the 2.3-year follow-up period, no change in global cognitive function (that is, PACC5abridged scores) was observed from baseline to follow-up (β = −0.0, P = 0.787) when analyzing longitudinal data in an adjusted linear mixed-effects model. In a separate mixed-effects model, a group-by-time interaction revealed no differences in PACC5abridged score changes according to psychological profile (F2,519 = 0.7, P = 0.519). However, although psychological profile membership was not associated with changes in PACC5abridged scores, analyses revealed stability in the association between psychological profile membership and global cognitive function. Specifically, psychological profile membership was associated with PACC5abridged scores at follow-up (F2,512 = 6.5, P = 0.002) when fitting a linear regression model. Planned pairwise comparisons revealed that individuals in profile 1 demonstrated worse global cognitive function compared to those in profile 3 (β = −0.2, P = 0.011). Following additional adjustment for anxiety and depressive symptoms in sensitivity analyses, the results remained largely unchanged.

Cortical thickness

Vertex-wise general linear models were fitted using FreeSurfer to investigate longitudinal changes in cortical thickness. During the follow-up period, cortical thinning was observed, spanning the lateral and medial parts of the frontal cortex (that is, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate and orbital cortices), the inferior parietal lobule and the precuneus/posterior cingulate region, as well as the lateral, middle and anterior parts of the temporal lobe. Other regions, such as the primary visual and motor cortices, were less affected (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Psychological profile membership was associated with change in cortical thickness from baseline to an average of 2.3 years of follow-up. Specifically, planned pairwise comparisons revealed that, compared to profile 3, individuals in profile 1 exhibited the greatest cortical thinning in the inferior and middle temporal regions and the fusiform gyri bilaterally, as well as in the lateral occipital and pericalcarine area (spanning the lingual gyrus and cuneus) in the left hemisphere. These differences were maintained after adjusting for anxiety and depressive symptoms, and in this adjusted model, differences were also observed between profiles 1 and 2 in the thinning of the inferior temporal lobe region where the former group exhibited accelerated brain atrophy (Fig. 5). In sensitivity analyses that included additional adjustments for cognitive change, differences between profiles 1 and 3 were still observed in the inferior temporal and lateral occipital regions in the primary model. In the adjusted analyses, significant differences were only observed in the inferior temporal region.

a,b, Vertex-wise symmetrized percent change maps of significant clusters surviving family-wise error multiple comparison correction in 533 participants from BBHI, for the primary model (adjusted for age, sex and education; a) and the adjusted model (further adjusted for depression and anxiety symptoms; b). Blue to light blue reflects higher cortical thickness loss for profile 1 in comparison to profile 3 (in a and upper row of b) and profile 2 (lower row of b). In a, final cluster-wise P values are <0.001 for the cluster around the right lateral occipital area, 0.034 for the cluster around the right fusiform area and <0.001 around the left inferior temporal area. In b, when comparing profile 1 versus profile 3, final cluster-wise P values are <0.001 for the cluster around the right lateral occipital area and <0.001 for the cluster around the left inferior temporal area. When comparing profile 1 versus profile 2, the final cluster-wise P value is 0.004 for the cluster around the left inferior temporal area. All analyses were performed with vertex-wise one-factor/two-level general linear models, as provided by FreeSurfer.

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationships between psychological profiles, mental and cognitive health, lifestyle and brain integrity. We identified three distinct profiles based on responses to questionnaires that measured nine psychological characteristics. These characteristics were selected based on previous literature reporting their relative risk of or protection from cognitive decline and dementia. The observed psychological profiles included a first group characterized by lower scores on positive or protective psychological characteristics, a second group with high negative or psychological risk characteristics, and a third group with moderately high protective and moderately low risk characteristics. These profiles were independently observed in a middle-aged cohort and an older adult cohort, suggesting that the selected psychological characteristics appear to aggregate in a robust and reproducible manner, even in populations that differ not only in age but also in gender distribution. They were also primarily based in different countries.

In both cohorts, profile 1 comprised individuals with lower scores in questionnaires capturing psychological domains that may confer protection from dementia10,16,17, reduced expression of clinical symptoms in the face of pathology18, and better cognitive status and higher brain resilience11,19. In the older adult cohort (Medit-Ageing), individuals in profile 1, compared to those in profiles 2 and 3, exhibited worse performance on the global cognitive composite score sensitive to Alzheimer’s disease-related decline. Regarding mental health, in both cohorts, participants in profile 1 showed an intermediate level of depression and anxiety symptoms, fewer than profile 2 and generally more than profile 3. In relation to modifiable health and lifestyle factors, profile 1 participants also exhibited higher LIBRA scores (indicating greater dementia risk) and lower engagement in cognitively stimulating activities compared to profile 3 in the middle-aged cohort (that is, BBHI). Notably, while some core psychological factors characterizing this group, such as purpose in life, have been previously associated with depression and anxiety20, the majority of our findings were maintained after adjusting for these symptoms.

Previous studies have shown that some personality characteristics, such as conscientiousness and openness to experience, may confer relative protection from dementia incidence17 and that they may be related to individual variability in Alzheimer’s disease biomarker expression8. Compared to positive affect, measures of eudaimonic well-being, such as purpose and meaning in life, have also been associated with reduced dementia risk10, and both clinicopathological and brain imaging studies have indicated that individuals with high purpose in life possess greater resilience to brain pathology regarding its impact on cognitive function19,21. Building on these previous observations, the present findings further indicate that individuals with lower protective factors (profile 1) exhibit accelerated atrophy compared to the well-balanced group (profile 3). These areas included posterior temporo-occipital cortical regions previously shown to reflect age-related changes but also partially included within the cortical thinning signature of Alzheimer’s disease22,23. In summary, profile 1 showed the worst cognition in Alzheimer’s disease-sensitive domains, and greater cortical thinning including non-Alzheimer’s and Alzheimer’s-sensitive regions. In addition, compared to profile 3, this group also had a higher LIBRA risk score among middle-aged individuals as well as lower engagement in specific modifiable lifestyles (that is, lower cognitive and social activity) previously associated with relative protection against dementia3.

In our study, participants in profile 2 comprised individuals with greater proneness to distress and negative thinking styles, with high loads in brooding, worry and neuroticism. Brooding and worry are core components of repetitive negative thinking, a negative style of thinking previously proposed to be central to the accumulation of cognitive debt24 and associated with accelerated cognitive decline among older adults5. Neuroticism has also been related to higher risk of dementia17,25. Our findings revealed that, in both cohorts, profile 2 individuals exhibited the greatest symptoms of depression, anxiety and loneliness, and worst sleep quality compared with the other profiles. They also had higher memory complaints compared to profile 3. In the middle-aged cohort, profile 2 also had higher overall risk for dementia (LIBRA) compared to profile 3, and lower engagement in cognitively stimulating activities. Hence, factors involving strong subjective and emotional components, all of which have previously been associated with dementia risk3,26,27,28,29,30, appear to be central features of this group. Interestingly, no consistent differences emerged in objective measures of age-related health (for example, cognition, cortical thickness) in this group when compared to individuals within the ‘well-balanced’ profile (profile 3).

Previous studies have investigated the relevance of aggregated psychological factors for cognitive decline and dementia risk through a variable-centered approach, for example to identify the most robust subscales or traits that contribute to latent variables defining a given psychological construct, and have shown associations with cognitive status or brain pathology13,31. Our approach differs in that we used a person-centered approach. This approach could be beneficial to help identify groups of individuals who may be at greater risk of age-related decline. First, our findings reveal that having a ‘well-balanced’ psychological profile (profile 3), with moderately high protective and moderately low risk factors is related to better cognitive and mental health across all measured indicators. These associations were observed in middle-aged and older adults, which reinforces the relevance of considering the equilibrium of a broad range of psychological aspects as determinants of mental, cognitive and brain health in adulthood and advanced age.

Second, although it is increasingly acknowledged that high distress and depressive symptoms, as well as cognitive or sleep complaints (which are more characteristic of our profile 2), may indicate higher risk for future decline or dementia, evaluations in the clinical context rarely include assessments of protective factors (for example, high purpose in life). However, although individuals that resemble our profile 1 participants may not present with high anxiety/stress-related symptoms or cognitive complaints, they appear to be the closest to having ‘classical dementia risk’ (that is, lower cognitive performance, lower engagement in beneficial lifestyles and greater cortical atrophy). Combined, these findings highlight the importance of conducting comprehensive psychological evaluations, including both assessment of ‘risk’ as well as ‘protective’ factors, when aiming to estimate an individual’s risk profile. The above observations may also have implications for future interventions designed to prevent cognitive impairment and dementia. First, they provide new pathways for more personalized interventions based on the psychological profile of individuals. For example, individuals with profiles compatible with our profile 1 could benefit most from psychological therapies that include (re)-identification of valued behavior and life purposes such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)32, whereas others (for example, meeting criteria for profile 2) may have a better response to therapies directed at reducing distress-related symptoms, which have also recently shown to entail potential benefit33,34.

Finally, our findings highlight that psychological profiles are differentially associated with engagement in other modifiable factors and lifestyles previously related to risk or protection for dementia. While accumulating evidence suggests that multidomain interventions that target modifiable factors and lifestyles show greatest promise for prevention35,36, lack of adherence and personalization are still important challenges faced by these approaches. Our findings could enhance preventative intervention initiatives by (1) offering psychological components as potentially modifiable intervention targets, and (2) guiding and deepening personalized interventions tailored for specific groups. From a mechanistic perspective, exploring whether modifying psychological profiles can drive lifestyle change, hence acting as potential intervention enhancers, would be a promising line of investigation.

Our study has several limitations that should be considered in further research in the field. First although we included a middle-aged and an older adult sample and the overall results were independently replicated, we only explored longitudinal associations with cognition and brain changes in the former. Second, we did not apply multiple comparisons corrections to our planned pairwise comparisons, as our aim was to uncover potential patterns and relationships rather than validate definitive hypotheses. Although this approach may increase the risk of type I errors, it enables the identification of relationships that warrant further investigation. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further validate these initial findings. Third, despite reporting associations between psychological profiles and cortical atrophy, we did not include specific dementia (in particular, Alzheimer’s disease) biomarkers. Previous studies focusing on specific psychological characteristics have found associations in this regard5,8, so future prospective investigations should be undertaken to investigate whether psychological profiles also reflect these associations. We used domains that were available in both cohorts to generate the psychological profiles, so additional domains that have been reported as psychological risk (for example, pessimism37) or protective factors (for example, mindfulness13) were not captured. Finally, although our person-centered approach has some advantages as described above, it also reflected some apparent inconsistencies regarding the specific psychological feature of self-reflection. Individuals with profile 2 exhibited higher scores in self-reflection, which refers to the active evaluation of thoughts, feelings and behaviors, and has recently been associated with better global cognition and more preserved brain metabolism after adjusting for brooding12. However, self-reflection is also associated with high levels of brooding38, which may explain why in our study it aggregates in this ‘high negative’ profile and is lower in the ‘well-balanced’ one. Future work could examine the unique contribution of ‘self-reflection’ in the profiles.

In summary, the present study focusing on psychological profiling has identified two divergent patterns of associations that may suggest two distinct paths for cognitive impairment or dementia risk. A low positive profile, characterized by low purpose in life and lower levels of some personality characteristics (conscientiousness, openness to experience, extraversion and agreeableness), was related to worse cognition (more clearly observable in older adults), higher brain atrophy (already observable in middle age) and lower engagement in protective lifestyles. A high negative profile, characterized by greater proneness to distress and negative thinking styles, may increase the risk of cognitive impairment/dementia through a psycho-affective pathway, which includes expressing symptoms of depression and anxiety, cognitive complaints, loneliness and poor sleep health. Our findings highlight the need to consider both risk profile patterns when designing future, more personalized preventive strategies.

Methods

Participants

Data were utilized from participants enrolled in two European cohorts: BBHI (https://bbhi.cat/en) and Medit-Ageing (Silver Santé Study (public name): https://silversantestudy.eu/).

BBHI is an ongoing longitudinal cohort study that launched in 2017, with the primary aim of investigating the determinants of mental and brain health in healthy middle-aged and older adults. At study commencement, adults aged 40 to 65 years were eligible if they had no neurological or psychiatric disorders, unstable medical diagnoses, or cognitive impairment based on a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment39,40. For the current study, participants with data available on psychological characteristics that matched the ones administered in Medit-Ageing (see below) and who also completed cognitive, brain imaging, lifestyle and/or mental health assessments at baseline were included. BBHI was approved by the Unió Catalana d’Hospitals ethics committee (approval references CEIC 17/06 and CEI 18/07). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Medit-Ageing aims to explore the determinants of mental health and well-being in older adults. It comprises two randomized controlled trials, Age-Well and SCD-Well, with baseline data from these trials utilized in the present study41,42. All Age-Well participants were recruited from the general population, aged 65 years or older, native French speakers, retired for at least one year, and received at least seven years of education, with recruitment beginning in late 2016 and ending in May 201841. In SCD-Well, participants were recruited through memory clinics at four European centers (London, UK; Lyon, France; Cologne, Germany; Barcelona, Spain), met research criteria for subjective cognitive decline (that is, self-perceived decline in cognitive capacity but normal performance on standardized cognitive tests used to classify mild cognitive impairment or prodromal AD43), and were aged 60 or older, with recruitment occurring from March 2017 to January 201842. Participants in Age-Well and SCD-Well had no evidence of major neurological or psychiatric disorders and performed within normal ranges on standardized cognitive tests. Baseline data from both trials were combined to create a single cohort (that is, Medit-Ageing) for the present study. Both trials were approved by local ethics committees (Age-Well: CPP Nord-Ouest III, Caen; EudraCT: 2016-002441-36; IDRCB: 2016-A01767-44; SCD-Well: London, UK (Queen Square Research Ethics Committee: no. 17/LO/0056 and Health Research Authority IRAS project ID: 213008); Lyon, France (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est II Groupement Hospitalier Est: no. 2016-30-1 and Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé: IDRCB 2016-A01298-43); Cologne, Germany (Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln: no. 17-059); and Barcelona, Spain (Comité Etico de Investigacion Clinica del Hospital Clinic de Barcelona: no. HCB/2017/0062)) and were registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Age-Well, NCT02977819; SCD-Well, NCT03005652). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Measures

Psychological characteristics

In both BBHI and Medit-Ageing, the participants completed self-report questionnaires to assess a range of psychological characteristics. For the current study, the selection of psychological characteristics followed two criteria: first, their relevance was established based on existing evidence indicating their potential impact on cognition, Alzheimer’s disease pathology and/or dementia; second, they needed to be available in both cohorts. Following these criteria, brooding, worry and neuroticism were selected as psychological characteristics associated with heightened risk, whilst purpose in life, conscientiousness, openness to experience, extraversion, agreeableness and self-reflection were identified as protective psychological characteristics. Supplementary Table 7 provides details on the questionnaires used to measure these characteristics in both cohorts.

Mental health

Depression and anxiety symptoms were assessed in both cohorts. In BBHI, the ‘depression’ and ‘anxiety’ subscales of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress scale (DASS; possible range 0 to 21) were used44. In Medit-Ageing, depressive symptoms were assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; possible range 0 to 15)45, and anxiety symptoms examined via the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) trait sub-scale (possible range 20 to 80)46. Anxiety and depression are regarded as distal outcomes as they represent symptoms of clinical conditions, whereas the selected psychological characteristics act as proposed antecedents. For example, although worry is considered the cognitive component of anxiety, empirical evidence supports its distinction as an independent construct. Research suggests a unidirectional relationship between worry and anxiety, with a strong positive effect of worry on anxiety but no effect in the opposite direction47.

Cognition

The PACC5 is a validated global cognitive composite sensitive to detecting and tracking preclinical Alzheimer’s disease-related decline48. It comprises two episodic memory measures and one measure of executive function, semantic memory and global cognition, and allows the flexibility to select specific tests within each domain48. In Medit-Ageing and BBHI, the four-item PACC5abridged was created49, as only one episodic memory measure was available in SCD-Well. PACC5abridged scores were computed separately in each cohort by averaging z-transformed cognitive test scores, with scores only calculable when data were available for all constituent measures. Higher PACC5abridged scores indicate better cognition. Supplementary Table 8 and the Supplementary Methods detail the specific neuropsychological tests included in PACC5abridged and the procedure used to calculate the composite in each cohort.

In addition to objective cognition, subjective perception of cognitive health was examined in BBHI and Medit-Ageing using the Neuro-QoL (possible range 12 to 60)50 and McNair Cognitive Difficulties Scale (CDS; possible range 0 to 156)51, respectively. Higher Neuro-QoL and lower McNair CDS scores indicate greater perceived cognitive difficulties.

Health and lifestyle

The late-life LIBRA is a poly-environmental risk score for cognitive functioning and dementia risk52. It typically comprises ten health and lifestyle factors (depression, coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, physical inactivity, renal disease, low-to-moderate alcohol use, high cognitive activity and healthy diet), which receive weights based on their relative risk52. As depressive symptoms are an outcome in the current study and are included as a covariate in sensitivity analyses, a nine-item LIBRA index was derived by removing the depression-weighted score12. To compute the nine-item LIBRA, the weights of the remaining nine factors were summed to yield LIBRA scores (possible range −5.9 to 7.4). Higher LIBRA scores indicate poorer health and lifestyle behaviors. The LIBRA was calculable only in BBHI, because 44.4% of the LIBRA components were assessed differently in the two studies (Age-Well and SCD-Well) comprising Medit-Ageing. This made it infeasible to compute a LIBRA score in Medit-Ageing that was comparable across participants. Supplementary Table 9 contains further details on the risk and protective factors included in the LIBRA in BBHI.

In addition to the health and lifestyle factors included in the LIBRA score, loneliness (measured with the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale; possible range 3 to 9)53 and perception of sleep quality (measured in BBHI using the Jenkins scale (possible range 4 to 24)54 and in Medit-Ageing using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (possible range 0 to 21)55) were assessed in both cohorts. In BBHI, social interaction engagement was also examined via the LUBBEN social network scale (LSNS; possible range 0 to 60)56.

MRI acquisition and analyses

For the BBHI cohort, MRI images were acquired in a 3T Siemens scanner (MAGNETOM Prisma) with a 32-channel head coil at the Unitat d’Imatge per Ressonància Magnètica IDIBAPS (Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer) at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. For all participants, a high-resolution T1-weighted (T1w) structural image was obtained with a magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo (MPRAGE) three-dimensional protocol (repetition time (TR) = 2,400 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.22 ms, inversion time = 1,000 ms, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm, 0.8-mm isotropic voxel). Additionally, a high-resolution three-dimensional SPACE T2-weighted (T2w) acquisition was taken (TR = 3,200 ms, TE = 563 ms, flip angle = 120°, 0.8-mm isotropic voxel, FOV = 256 mm). All acquisitions were examined by a senior neuroradiologist to detect any clinically significant pathology. All MRI data were then visually inspected before analysis to ensure that they did not contain artifacts or excessive motion.

Individual T1w images for each time point were automatically processed with FreeSurfer version 6.0 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) to obtain maps of cortical thickness, following a previously described procedure57. The processing stream was run with default parameters, except for the addition of the T2w images for the improvement of pial surfaces reconstruction. All images obtained a high Euler score (that is, 2), indicating that the reconstructions consisted of smooth surfaces, with no holes or handles detected in the pial or the white matter surfaces, at either time point. Next, within-subject template volumes and longitudinal files were created for each participant and time point through the longitudinal stream58. At each step, the results were visually inspected following gross quality-control measures, and no manual editing was performed. The symmetrized percentage change was used as a robust longitudinal measure of cortical thickness, computed as the percentage of change corrected for the average cortical thickness values at each time point. Before statistical analysis, cortical thickness maps were smoothed using a two-dimensional Gaussian kernel of 15-mm full-width at half-maximum. We carried out a vertex-wise one-factor/three-level general linear model provided by FreeSurfer to study profile differences regarding cortical thickness loss (that is, symmetrized percent change). The primary model was adjusted for baseline age, sex and education, with a subsequent model including additional adjustments for symptoms of anxiety and depression. Sensitivity analyses included cognitive change as an additional covariate. Additionally, we obtained longitudinal maps of atrophy for the whole sample. Multiple comparisons correction of whole-brain vertices was performed by computing P values for contiguous clusters of vertices based on Monte-Carlo Null-Z simulations and permutation (with 10,000 iterations per simulation). This method assigns a P value to each resulting cluster. Consequently, we used a cluster-forming threshold of P < 0.05 and a cluster significance threshold of P < 0.05 in all models.

Statistical analyses

LPA

In the initial analysis stage, LPA was conducted on the nine psychological characteristics, using data from nine questionnaires at baseline from all participants. Analyses were conducted separately for each cohort (BBHI and Medit-Ageing), enabling a comparative assessment and validation of the profile structures.

Various model fit statistics were considered to determine the optimal profile solution. The VLMR-LRT and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (B-LRT) were performed to identify the best fitting model. Because no prior hypotheses were made regarding the number of profiles that would arise, analyses were conducted starting with a two-profile model and increasing the number of profiles by one until the VLMR-LRT became non-significant. To confirm the K-1 model results, a parametric bootstrap procedure was employed using the B-LRT. This was further supplemented by the evaluation of common fit indices, including the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample size-adjusted BIC, and entropy values. The VLMR-LRT and B-LRT tests compare K (current model with K number of profiles) and K – 1 (model with one less profile) models, where a significant P value indicates that the K model provides a better fit compared to the model with one less profile. Conversely, P ≥ 0.05 indicates that the model with one less profile is preferred, as it provides a better fit for the data and is more parsimonious. Lower AIC and BIC values indicate a better fitting model, while higher entropy values suggest higher classification accuracy. In the scenario of multiple possible profile solutions, model interpretability and clinical/theoretical relevance were considered. Furthermore, as a profile-utility criterion, profiles needed to include at least 5% of the total sample. After determining the optimal profile solution within each cohort, participants were assigned to the profile for which they exhibited the highest probability of membership, for use in subsequent analyses.

Cross-sectional analyses

Differences in demographic characteristics (that is, age, sex, education, ethnicity and APOE ε4 genotype) were examined between cohorts and across profiles within cohorts. Of note, a direct comparison of educational attainment between cohorts was not possible due to differences in the assessment methods for education in BBHI and Medit-Ageing.

After identifying the optimal profile solution within each cohort, regression models were constructed to explore the cross-sectional associations between psychological profiles and mental, cognitive and brain health, along with other lifestyle-related behaviors linked to dementia risk. For the latter, the components included in the LIBRA composite were analyzed separately as continuous variables when available (instead of the dichotomized version that were used to calculate the composite). These analyses were conducted separately for each outcome and in each cohort independently. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex and education, and in Medit-Ageing, study (that is, Age-Well/SCD-Well) was also included as a covariate. In sensitivity analyses, anxiety and depressive symptoms were included as additional covariates. Associations between psychological profile membership and all outcomes were first evaluated using the anova command in R to determine whether psychological profile membership was related to the selected outcome. Following identification of an association, adjusted planned pairwise comparisons were performed using the emmeans function.

Longitudinal analyses

To assess cognitive changes across two time points, linear mixed-effects models were fitted, with PACC5abridged as the dependent variable. These models included random intercepts at the subject level and time coded as a dummy variable (that is, visit). Initially, a model was run to investigate general temporal change, representing the overall change in cognition over time regardless of profile group. Subsequently, a separate model was run, introducing a time-by-profile interaction to examine differences in cognitive change (that is, slopes) over time among the three latent profiles. All analyses were adjusted for age at baseline, sex, education and the number of months between the two visits. These analyses were restricted to a BBHI subsample comprising participants who underwent two neuropsychological evaluations.

All baseline cross-sectional analyses were conducted again using data from the BBHI subsample with longitudinal data to assess the comparability of findings with the total BBHI sample. Additionally, cross-sectional analyses (that is, regression models) using visit two data were performed, as described above, to explore whether the associations observed between psychological profiles and cognition at baseline were maintained at follow-up.

The LPA was performed in Mplus (version 8.3). R (version 4.3.1) was used to conduct all other analyses, including regressions using the lm function, and planned pairwise comparisons using the emmeans package. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this Article.

Data availability

For BBHI, the data are not publicly accessible. However, the authors welcome inquiries from interested researchers and will accommodate all reasonable and scientifically justified requests for data access, providing the raw data when needed. Queries should be addressed to D. Bartrés-Faz. For Age-Well and SCD-Well, the material can be mobilized on request following a formal data-sharing agreement and approval by the consortium and executive committee, under the conditions and modalities defined in the Medit-Ageing Charter by any research team belonging to an Academic, for carrying out a scientific research project relating to the scientific theme of mental health and well-being in older people. The material may also be mobilized by non-academic third parties, under conditions, in particular financial, which will be established by separate agreement between lnserm and the said third party. Information and access to the data request form can be found at https://silversantestudy.eu/2020/09/25/data-sharing.

References

Mental Health of Older Adults (World Health Organization, 2023); https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults

Prince, M. et al. World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2015).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 404, 572–628 (2024).

Bartrés-Faz, D., Solé-Padullés, C. & Marchant, N. L. Cognitive aging and dementia prevention: the time for psychology? Aging (Albany NY) 15, 889–891 (2023).

Marchant, N. L. et al. Repetitive negative thinking is associated with amyloid, tau and cognitive decline. Alzheimers Dement. 16, 1054–1064 (2020).

Schlosser, M., Demnitz-King, H., Whitfield, T., Wirth, M. & Marchant, N. L. Repetitive negative thinking is associated with subjective cognitive decline in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 20, 500 (2020).

Karim, H. T. et al. Aging faster: worry and rumination in late life are associated with greater brain age. Neurobiol. Aging 101, 13–21 (2021).

Terracciano, A. et al. Personality associations with amyloid and tau: results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging and Meta-Analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 359–369 (2022).

Nabe-Nielsen, K. et al. Perceived stress and dementia: results from the Copenhagen city heart study. Aging Ment. Health 24, 1828–1836 (2020).

Bell, G., Singham, T., Saunders, R., John, A. & Stott, J. Positive psychological constructs and association with reduced risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 77, 101594 (2022).

Bartrés-Faz, D., Cattaneo, G., Solana, J., Tormos, J. M. & Pascual-Leone, A. Meaning in life: resilience beyond reserve. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 10, 47 (2018).

Demnitz-King, H. et al. Association of self-reflection with cognition and brain health in cognitively unimpaired older adults. Neurology 99, e1422–e1431 (2022).

Strikwerda-Brown, C. et al. Trait mindfulness is associated with less amyloid, tau, and cognitive decline in individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 3, 130–138 (2022).

Kusurkar, R. A. et al. ‘One size does not fit all’: the value of person-centred analysis in health professions education research. Perspect. Med. Educ. 10, 245–251 (2021).

Bergman, L. R. & Magnusson, D. A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 9, 291–319 (1997).

Sutin, Dr. A. R. et al. Sense of meaning and purpose in life and risk of incident dementia: new data and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 105, 104847 (2023).

Aschwanden, D. et al. Is personality associated with dementia risk? A meta-analytic investigation. Ageing Res. Rev. 67, 101269 (2021).

Boyle, P. A. et al. Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 499–504 (2012).

Abellaneda-Pérez, K. et al. Purpose in life promotes resilience to age-related brain burden in middle-aged adults. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 49 (2023).

Boreham, I. D. & Schutte, N. S. The relationship between purpose in life and depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 79, 2736–2767 (2023).

Willroth, E. C. et al. Well-being and cognitive resilience to dementia-related neuropathology. Psychol. Sci. 34, 283–297 (2023).

Dickerson, B. C. et al. The cortical signature of Alzheimer’s disease: regionally specific cortical thinning relates to symptom severity in very mild to mild AD dementia and is detectable in asymptomatic amyloid-positive individuals. Cereb. Cortex 19, 497–510 (2009).

Storsve, A. B. et al. Differential longitudinal changes in cortical thickness, surface area and volume across the adult life span: regions of accelerating and decelerating change. J. Neurosci. 34, 8488–8498 (2014).

Marchant, N. L. & Howard, R. J. Cognitive debt and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 44, 755–770 (2015).

Terracciano, A. et al. Is neuroticism differentially associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and frontotemporal dementia? J. Psychiatric Res. 138, 34–40 (2021).

Pike, K. E., Cavuoto, M. G., Li, L., Wright, B. J. & Kinsella, G. J. Subjective cognitive decline: level of risk for future dementia and mild cognitive impairment, a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Neuropsychol. Rev. 32, 703–735 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Depression, depression treatments, and risk of incident dementia: a prospective cohort study of 354,313 participants. Biol. Psychiatry 93, 802–809 (2023).

Santabárbara, J. et al. Does anxiety increase the risk of all-cause dementia? An updated meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Clin. Med. 9, 1791 (2020).

Shi, L. et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 40, 4–16 (2018).

Qiao, L. et al. Association between loneliness and dementia risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 899814 (2022).

Pichet Binette, A. et al. Amyloid and tau pathology associations with personality traits, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and cognitive lifestyle in the preclinical phases of sporadic and autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 776–785 (2021).

Stenhoff, A., Steadman, L., Nevitt, S., Benson, L. & White, R. G. Acceptance and commitment therapy and subjective wellbeing: a systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials in adults. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 18, 256–272 (2020).

John, A. et al. Associations between psychological therapy outcomes for depression and incidence of dementia. Psychol. Med. 53, 4869–4879 (2023).

Stott, J. et al. Associations between psychological intervention for anxiety disorders and risk of dementia: a prospective cohort study using national health-care records data in England. Lancet Healthy Longev. 4, e12–e22 (2023).

Ngandu, T. et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 385, 2255–2263 (2015).

Kivipelto, M. et al. World-Wide FINGERS Network: a global approach to risk reduction and prevention of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 16, 1078–1094 (2020).

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y. & Terracciano, A. Psychological distress, self-beliefs, and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 65, 1041–1050 (2018).

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R. & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cogn. Ther. Res. 27, 247–259 (2003).

Cattaneo, G. et al. The Barcelona Brain Health Initiative: a cohort study to define and promote determinants of brain health. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 321 (2018).

Cattaneo, G. et al. ‘Guttmann Cognitest’®, preliminary validation of a digital solution to test cognitive performance. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 987891 (2022).

Poisnel, G. et al. The Age-Well randomized controlled trial of the Medit-Ageing European project: effect of meditation or foreign language training on brain and mental health in older adults. Alzheimers Dement. (N. Y.) 4, 714–723 (2018).

Marchant, N. L. et al. The SCD-Well randomized controlled trial: effects of a mindfulness-based intervention versus health education on mental health in patients with subjective cognitive decline (SCD). Alzheimers Dement (N. Y.) 4, 737–745 (2018).

Jessen, F. et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 10, 844–852 (2014).

Brown, T. A., Chorpita, B. F., Korotitsch, W. & Barlow, D. H. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav. Res. Ther. 35, 79–89 (1997).

Sheikh, J. I. & Yesavage, J. A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Ment. Health 5, 165–173 (1986).

Spielberger, C. D., Gonzalez-Reigosa, F., Martinez-Urrutia, A., Natalicio, L. F. & Natalicio, D. S. The state-trait anxiety inventory. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia/Interam. J. Psychol. 5, 145–158 (1971).

Gana, K., Martin, B. & Canouet, M. D. Worry and anxiety: is there a causal relationship? Psychopathology 34, 221–229 (2001).

Papp, K. V., Rentz, D. M., Orlovsky, I., Sperling, R. A. & Mormino, E. C. Optimizing the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite with semantic processing: the PACC5. Alzheimers Dement. (N. Y.) 3, 668–677 (2017).

Whitfield, T. et al. Effects of a mindfulness-based versus a health self-management intervention on objective cognitive performance in older adults with subjective cognitive decline (SCD): a secondary analysis of the SCD-Well randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14, 125 (2022).

Cella, D. et al. Neuro-QOL: brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology 78, 1860–1867 (2012).

McNair, D. & Kahn, R. Self-assessment of cognitive deficits. Assess. Geriatr. Psychopharmacol. 137, 143 (1983).

Deckers, K. et al. Long‐term dementia risk prediction by the LIBRA score: a 30‐year follow‐up of the CAIDE study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 35, 195–203 (2020).

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Res. Aging 26, 655–672 (2004).

Jenkins, C. D., Stanton, B.-A., Niemcryk, S. J. & Rose, R. M. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 41, 313–321 (1988).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Lubben, J. E. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam. Community Health 11, 42–52 (1988).

Fischl, B. & Dale, A. M. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11050–11055 (2000).

Reuter, M. & Fischl, B. Avoiding asymmetry-induced bias in longitudinal image processing. Neuroimage 57, 19–21 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from ‘la Caixa’ Foundation (grant no. LCF/PR/PR16/11110004), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program (grant no. 667696) and from Institut Guttmann and Fundació Abertis. D.B.-F. was funded by grant PID2022-137234OB-100 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ‘ERDF/EU’, a ‘Programa de Estancias de Movilidad en Centros Extrangeros’, a Research Stay Grant (PRX21/00690) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Universities, and an ICREA Academia 2019 research grant from the Catalan Government. C.G. and J.S.-S. are partially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2022-139298OA-C22). L.V.-A. was partially funded by a Margarita Salas Grant from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Government of Spain (Next Generation EU program) and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Sara Borrell Grant CD23/00235). J.G. was supported by a Young Researcher Grant 2019–2022 from the Fondation Alzheimer and Fondation de France. O.K. received funding from the Secrétariat d'État à la Formation, à la Recherche et à l’Innovation (SEFRI) under contract no. 15.0336 in the context of the European project ‘Medit-Ageing’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

N.L.M., H.D.-K. and D.B.-F. conceptualized the work and developed the methodology. H.D.-K., M.C.-T., R.S. and L.V.-A. carried out formal statistical analyses. N.L.M., D.B.-F., G. Chételat and A.P.-L. supervised the work. E.T., G. Cattaneo, J.G., O.K., N.B., J.S.-S. and J.M.T. contributed to data collection, writing or reviewing, and approving the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

O.K. has received honoraria for research, training and consulting related to meditation. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks Luca Cuffaro, Helmet T. Karim and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–9, figure and methods.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartrés-Faz, D., Demnitz-King, H., Cabello-Toscano, M. et al. Psychological profiles associated with mental, cognitive and brain health in middle-aged and older adults. Nat. Mental Health 3, 92–103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00361-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00361-8

This article is cited by

-

Associations of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Three Latent Multidimensional Health Patterns among Older Adults in China

Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma (2026)