Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping modern medicine and offers huge potential in hepatology, where late presentation and limited treatments are major challenges. However, real-world adoption remains limited, hindered by regulatory uncertainty, technical hurdles, and ethical considerations. This review examines recent advances, persistent obstacles, and the potential of AI to redefine the future of liver care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global burden of liver disease

Chronic liver disease (CLD) is an escalating global health crisis, causing ~2 million deaths annually, rising disproportionately in working-age populations with far-reaching socio-economic impacts1. Increasing prevalence is largely driven by steatotic liver diseases (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, MASLD; alcohol-related liver disease, ALD; and metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-related liver disease, MetALD). Chronic hepatitis B and C virus (HBV/HCV) remain major global contributors, while autoimmune and cholestatic disorders (such as autoimmune hepatitis, AIH; primary biliary cholangitis, PBC; and primary sclerosing cholangitis, PSC), although less common, cause significant chronic liver injury. Across these diverse aetiologies, disease progression converges on major adverse liver outcomes such as compensated/decompensated cirrhosis, primary liver cancers (hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC; intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, iCCA), and liver-related death.

Most patients first present with advanced CLD in emergency settings2, reflecting the silent nature of early disease, lack of systematic community screening, and inequalities in access to timely care. Late presentation undermines opportunities for prevention and contributes to rising healthcare expenditure3. Addressing these challenges requires more effective risk stratification to target surveillance and treatment resources, individualise care pathways, and develop therapies for advanced disease. Artificial intelligence (AI), harnessing multidimensional data, predicting risk, and optimising clinical decision-making, may be transformative and usher in a new era in hepatology.

AI taxonomy

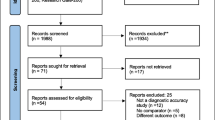

Large-scale patient data and AI are catalysing advances in translational liver research. AI is an umbrella term referring to computational methods performing complex tasks, supporting or enhancing human perception, reasoning, learning, and decision-making. Machine learning (ML) is a subset of AI that recognises patterns in complex data through supervised (input-output mapping) or unsupervised (discovering hidden structures) learning. Deep Learning (DL), using neural networks (NNs), detects features in images and videos via computer vision (CV) or speech and text via natural language processing (NLP)4,5 [Fig. 1]. Table 1 summarises key algorithms most frequently referenced in this review. Overall, the development of AI/ML models relies on extensive data preparation and processing for training and robust evaluation, before potential clinical adoption [Fig. 2]. AI promises a paradigm shift toward proactive, personalised, and equitable management.

Conceptual overview illustrating the relationships between Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and Neural Networks (NN). AI refers to a wide range of algorithms to simulate human-like reasoning and perform complex data handling tasks, while ML is one of the fundamental machineries. Framework highlights core ML learning strategies (e.g., supervised, unsupervised, semi-supervised, reinforcement, self-supervised, transfer) and representative algorithms. DL is a significant and popular subset of ML, which uses NN for a variety of tasks, such as computer vision (CV) and natural language processing (NLP). Generative AI and Agentic AI are advanced NLP and/or CV-based large AI models which can handle user interaction, including media of text, image, audio, and even video. NOTE: Some algorithms may span multiple categories depending on the nature of the data, task formulation, or implementation context (i.e., supervised or unsupervised). The hierarchical ordering and clustering shown in this figure are illustrative rather than prescriptive. The example algorithms listed are non-exhaustive and reflect a rapidly evolving field in which models are continuously emerging, refined, or replaced over time.

Data preparation begins with privacy safeguards (anonymisation/pseudonymisation), systematic cleaning, standardisation and cross-site harmonisation to mitigate batch effects. These steps are challenging due to heterogenous data sources of variable quality, which can introduce bias or limit generalisability. Metadata tagging enables auditability, while imputation and imaging-specific pre-processing (e.g., resizing, patching) reduce bias and variance; though improper handling may distort signals. Data processing includes image segmentation and ROI selection (radiology/pathology), data augmentation, dimensionality reduction, and feature ranking (‘omics) to enhance model learning. Biological knowledge is incorporated via label definitions, feature engineering, and model constraints to ensure biological plausibility and clinical relevance. Model evaluation involves appropriate algorithm selection, robust internal/external validation (ideally multi-centre), interpretability, and bias/fairness analyses across sex, ethnicity, age, or sociodemographics. Evaluation may be limited by small or unrepresentative datasets, risking hidden bias. Performance metrics include AUC/AUROC (discrimination), C-index (survival prediction), F1-score (class imbalance), and Dice coefficient (imaging accuracy). Clinical adoption requires more than accuracy: transparency, end user training, usability, cost management, post-deployment monitoring (e.g., model drift and recalibration), and regulatory compliance are essential. Poor monitoring or usability can impede clinical adoption despite strong performance. Together, these stages define an evidence-based pathway from raw data to clinically dependable AI tools, aligned with emerging best-practice guidelines and expert consensus.

This narrative review focuses on recent advances (2023–2025), highlighting emerging diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic applications for AI in hepatology and examining challenges that must be addressed for implementation in clinical practice.

Data sources

AI depends on large, diverse “Big Data” to generate clinically meaningful insights, although each data type presents unique challenges.

Health record systems

Electronic health records (EHRs) contain longitudinal patient information, including sociodemographic details, diagnostic and procedural codes, laboratory results, imaging reports, medications, and administrative data. Structured data (e.g., laboratory results, codes) are generally more standardised, whereas unstructured data (e.g., free-text clinical notes) exhibit greater variability and pose additional challenges for AI integration. EHRs are now near universal in the US and EU, enabling large-scale studies. However, missing information, data entry errors, and inconsistencies between records are common. Patient-generated health data from smartphones, wearables, or applications offers the potential to integrate granular lifestyle insights with EHRs, but a lack of standardisation and accuracy concerns are barriers to immediate utilisation.

Imaging data

Expert evaluation remains the reference standard for assessing histopathological features. However, biopsies are invasive, limited by sampling error, and susceptible to inter-/intra-observer variability inherent in subjective assessment. In contrast, non-invasive imaging modalities such as ultrasounds, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologies allow quantitative whole-liver assessment. Digitalised histology whole-slide images (WSIs) also produce structured, high-resolution datasets for AI analyses. ML enables objective and reproducible scoring of features while reducing interpretative variability. Nevertheless, heterogeneity in acquisition protocols and image reconstruction parameters limits standardisation. Additional variability can also arise from differences between instrument manufacturers, although contemporary AI models often incorporate normalisation or domain adaptation strategies to mitigate such effects.

Multiomics

As ‘omics data proliferate (Supplementary Table 1), their integration is delivering system-level insights to identify candidate biomarkers and therapeutic targets. AI/ML is essential to manage these complex datasets, although high heterogeneity, dimensionality, and processing variability challenge reproducibility and clinical translation.

Opportunities of AI

As the volume of multimodal data expands, so does the potential for identifying novel diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic tools. Large-scale data commons (e.g., UK Biobank, NHANES) and focused liver-specific initiatives (e.g., SteatoSITE6) support both conventional hypothesis-driven and data-driven, hypothesis-free analyses to uncover patterns beyond conventional clinical paradigms.

Diagnostic opportunities

Current diagnostic pipelines combine patient history with isolated serological, radiological, and histological assessments. Applied to non-invasive tests (NITs), AI/ML approaches could uncover more subtle, multimodal signatures preceding symptoms, enabling earlier diagnosis, scalable screening, and more informed clinical decision-making. A comprehensive overview of diagnostic applications of AI in hepatology is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Image-based feature detection

AI/ML is being widely applied to radiological assessments of liver health. For example, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) pipelines applied to CT images accurately segmented whole livers7 and detected malignancies8, offering a potential tool for rapid triage. Similar approaches on ultrasounds9 and MRIs10 delivered accurate fibrosis staging. Assigning histological features of disease activity, such as steatosis grading from CT images11 or predicting hepatocyte ballooning scores from ultrasounds12, has also been possible. Other CNN-based models have characterised features such as vasculature13, ascites14, and body fat15.

Histology remains the gold standard for some disease assessment. Multiple AI/ML computational histopathology pipelines were developed to provide reproducible, granular, and interpretable feature quantification from biopsies. Ercan et al16. developed a CNN-based tool for AIH diagnosis using Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Sirius Red-stained WSIs, successfully classifying biopsies with 88.2% accuracy. Similar models were able to detect other features, such as portal tracts17 and microvascular invasion (MVI)18. Digital histopathology for MASLD is extensively reviewed elsewhere19.

Disease signatures and stratification

AI/ML approaches allow identification of latent disease-associated patterns within EHR datasets. Addressing diagnostic delays presented by chronic HCV’s asymptomatic onset, Sharma et al.20 stacked ML models to detect HCV infection from standard biochemistry laboratory tests, suggesting a path toward scalable, low-cost screening. In MASLD, a 17-variable Random Forest (RF) classification model outperformed standard NITs for biopsy-defined staging across four US centres21. Other DL models identified increased steatosis risk from unstructured data sources using NLP22, showcasing the potential of text mining for case identification at population scale.

Some diseases may benefit from nuanced spatial and systemic molecular assessment for earlier diagnosis and finer stratification. Oh et al.23 analysed MASLD biopsy-anchored multiomic data via Support Vector Machine-based feature selection and used a generalised linear regression model to derive a six-gene signature which generalised across independent cohorts. The model distinguished healthy from MASLD, and simple steatosis from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), identifying a blood signal in cell-free RNA suggesting non-invasive translation. Other studies implicated cell death24, oxidative stress25, inflammation26, and metabolic27 gene signatures as potential biomarkers for MASLD. Tavaglione et al.28 applied a Feedforward NN to data from over ~218,000 participants, finding that individuals with hypertriglyceridemia exhibited a 3-to-4-fold increased prevalence of MASLD and MASH, whereas hypercholesterolemia conferred only marginal risk, underscoring lipid profiling as a robust clinical signal to prompt targeted screening. AI/ML applied to urinary proteomics29, MRI-based fat content30, and circulatory extracellular vesicle (EV)31-based biomarkers have also shown promise.

Although HCC diagnosis remains radiological, AI/ML-driven transcriptomic32, cell-free DNA methylation33, serum metabolomics34, and oral/gut microbiome assays35 are emerging as credible molecular complements. Notably, Li et al.36 isolated fucosylated EVs from serum and trained a Logistic Regression (LR) model on five EV-miRNAs for HCC detection, rescuing >80% of previously misclassified cases.

Differential diagnosis

Liver diseases often present with non-specific features, making the challenges of diagnosis and accurate management amenable to assistance by AI/ML. Huang et al.37 developed a gut-microbiome-based strategy to distinguish simple steatosis from MASH, mapping pathway shifts in glucose metabolism and flavonoid biosynthesis. A similar approach differentiated ALD from MASLD metagenomically38, suggesting stool-based signatures as non-invasive diagnostic options. Using routine laboratory parameters, Wang et al.39 validated a Gradient-Boosted Decision Tree to differentiate idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (DILI) from AIH. Similarly, AI/ML supported the differentiation of PBC and AIH from saliva proteomics40 and histology41.

For patients with combined HCC-iCCA, Calderaro et al.42 developed a self-supervised CNN to re-classify tumours as HCC-like or iCCA-like, with attention maps showing that iCCA-like areas drove discrimination. Similar work used multiparametric MRI radiomics to classify HCC-iCCA43 and inflammatory pseudotumours44 pre-operatively. Wei et al.45 created LilNet, an automated detection system for hepatic lesions from multiphased-enhanced CT, successfully distinguishing focal nodular hyperplasia, haemangiomas, and cysts with 88.6% accuracy and highlighting AI/ML potential as a clinically deployable tool in radiological resource-limited settings.

Prognostic opportunities

Prognostication in MASLD largely depends on fibrosis severity. Existing non-invasive tests (such as Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4), Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, and vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE)) assess fibrosis, but their performance in population-level screening remains suboptimal46. Improved risk stratification may be achieved through earlier recognition of anthropometric, genetic, and metabolic risk factors, as opportunities for intervention diminish once significant fibrosis is established. A comprehensive overview of prognostic applications of AI in hepatology is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Risk prediction

Using routine EHR data, AI/ML models can deliver high-throughput, individualised risk estimates for liver disease across the general population. In MASLD, multiple large cohort studies have identified optimal predictors of CLD incidence and progression47,48,49. Yu et al.50 constructed a model using a RF with recursive feature exclusion from ten routine clinical variables, outperforming traditional risk indicators with body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, triglycerides, and fasting glucose among the top predictors, all potentially actionable via weight loss and glycaemic control. Njei et al.51 developed an Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) classifier to identify MASLD individuals at high risk of MASH based on alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), platelets, waist circumference, and age, surpassing NITs and demonstrating an approach to triage without FibroScanÒ. Complementing phenome-derived findings, transcriptomics52, metabolomics53, and proteomics54 studies support ML-based risk prediction and stratification of MASLD, often demonstrating lipid-centred signatures as dominant risk signals.

HCC risk stratification, prognosis, and recurrence

HCC annual incidence rate in patients with cirrhosis is ~2–3%55, but risk is heterogeneous. Guo et al.56 developed a metabolomic risk model of end-stage cirrhosis (including HCC) from UK Biobank participants. Based on eight serum metabolites, the model outperformed polygenic risk scores and, when integrated with routine clinical variables, accurately predicted 10-year outcomes. In a different cohort, CNN modelling predicted HCC occurrence from tumour-free baseline WSIs with ~82% accuracy in validation; saliency maps highlighting nuclear atypia, high hepatocellular nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, immune cell infiltrates, and lack of large fat droplets as predictive histopathological signals beyond fibrosis57. Further AI/ML prognostic studies identified liver fibrosis58, angiogenesis59, and glycosylation mechanisms60 as important features for risk stratification, but mainly in already diagnosed HCC patients. AI/ML also enhanced HCC surveillance in viral hepatitis. In chronic HBV, Wu et al61. trained an Artificial NN that accurately estimated 10-year risk in antiviral therapy (AVT)-treated patients, while in cured HCV, Nakahara et al62. applied Random Survival Forests to routine laboratory tests to define four 5-year risk strata. Strikingly, many events fell outside guideline cut-offs, underscoring AI’s value in calibrating surveillance.

Studies of HCC recurrence after transplant63, ablation64, or immunotherapy65 have also supported the use of AI/ML-derived risk scores to guide surgical decision-making. For example, single-cell mapping of primary and early-relapse HCC revealed rewired tumour-immune crosstalk dominated by MIF-CD74/CXCR4 signalling and malignant CD8⁺ T-cells, yielding a LASSO/Cox-derived 7-gene relapse score that outperformed clinical covariates and identified high-risk tumours66. MVI67, elevated alpha-fetoprotein63, peritumoural radiomic64 and pathomic68 features were additional predictors of recurrence.

Other complications

Accurate prognostication is also important in predicting decompensation and liver failure. In PSC, Singh et al. trained CNNs on portal-venous phase CTs to predict decompensation. Half-volume experiments69 and body composition quantification70 suggested diffuse signal contribution, supporting whole-organ phenotyping as a biomarker of deterioration. In MASLD, ML models showed that a combination of routine laboratory tests with some imaging modalities dominated decompensation prediction71,72. In HBV-related cirrhosis, a RF combining GP73 and α1-microglobulin with age, aspartate aminotransferase, ALT, and platelets best predicted decompensation. Interaction analyses showed that non-linear ML models captured transition risk better than linear indices like FIB-473. In surgical settings, multimodal DL models accurately predicted pre-operative post-hepatectomy liver failure74 while peri-operative EHR-based monitoring enabled early post-operative detection75, collectively supporting AI/ML’s value across the surgical timeline. Models predicting non-liver outcomes have also been developed. Veldhuizen et al.76 used a self-supervised Transformer NN to predict major cardiovascular events from liver MRI. Saliency maps implicated hepatic veins, inferior vena cava, and abdominal aorta health as key predictive features. MASLD also predisposes to renal complications. Sun et al.77 used ML-driven qFibrosis® digital histopathology quantification to track collagen remodelling around pericentral/central veins, which predicted estimated glomerular filtration rate and outperformed conventional histology.

Liver transplantation

AI/ML may help improve outcomes following liver transplantation (LT) by predicting graft survival and guiding clinical management. Sharma et al.78 developed GraftIQ, a clinician-informed multi-class NN integrating clinicopathological data from the 30 days pre-biopsy to accurately classify graft injury aetiologies. Using t-SNE unsupervised clustering, Chichelnitskiy et al.79 profiled soluble immune mediators from a prospective paediatric cohort, identifying a high CD56bright NK-cell plasma signature detectable two weeks post-LT associated with higher rejection-free survival, suggesting actionable, non-invasive markers to guide immunosuppression. Further immune80 and metabolome81-based AI/ML approaches have assessed drivers of LT dysfunction/rejection and their potential prognostic value.

Mortality

Mortality risk in CLD has long relied on the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, but AI/ML may allow greater discrimination. To predict HCC-related mortality, multiple studies integrated CNN auto-segmentation and regression-driven feature selection of pre-treatment CT scans combined with clinical variables, and most models outperformed traditional prognostic risk scores, emphasising image-derived features as powerful predictors of overall survival (OS)82,83. Complementing radiomics, Sun et al.84 derived a 3-gene epithelial-mesenchymal transition immune risk score that stratified OS prediction over 5 years. Generalisable HCC prognostic modelling from clinical registries has also been shown to accurately predict OS85,86.

In MASLD, Drozdov et al.87 used a Transformer NN to predict all-cause mortality at 12–36 months, with age, type-2 diabetes, and prolonged prior hospitalisation among key predictive factors. Huang et al.53 built a metabolome-derived score that accurately identified patients with biopsy-proven MASH and predicted liver-related mortality more accurately than clinical covariates.

AI/ML also improved prognosis prediction in acute settings. In ALD, interpretable ML outperformed legacy scores for short-term mortality, from intensive care unit parameter-based models in alcoholic cirrhosis88 to the global ALCHAIN ensemble in alcohol-associated hepatitis89, providing explainable risk factors and a bedside web tool that can inform steroid triage.

Therapeutic opportunities

Clinical outcomes in hepatology remain unpredictable with current management, with some patients progressing to end-stage liver disease despite removal of the underlying cause and others showing heterogeneous treatment responses90. A comprehensive overview of therapeutic and other applications of AI in hepatology is provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Drug discovery and repurposing

AI/ML is enabling the discovery of therapeutic targets across the CLD spectrum. Combining Cox Regression with Gradient Boosted Machine, Wen et al.91 generated a multiomic Consensus AI-derived Prognostic Signature (CAIPS) from HCCs. When integrated with pharmacological databases, the model recommended irinotecan and the PLK1 inhibitor BI-2536 for high-CAIPS profiles, subsequently validated in vitro. In MASLD-related HCC, Sun et al.92 derived metabolic dysfunction scores from public genomic databases and identified CACNB1 as a putative druggable target, with molecular docking analysis highlighting calcium-channel agents as testable inhibitors. Similarly, Venhorst et al.93 fused phenotypic and transcriptomic profiling to propose an EP300/CBP bromodomain inhibitor, inobrodib, as an anti-fibrotic strategy in MASH. Finally, through proteomic profiling of serum samples associated with PSC progression to cirrhosis, Snir et al.94 described a CCL24-defined druggable chemokine axis; a clinical trial for anti-CCL24/CM-101 immunotherapy is ongoing, with positive Phase 2 signals (NCT04595825)95.

AI tools are also becoming embedded within therapeutic pipelines. Ren et al.96 integrated an AI-based platform for therapeutic target prioritisation (PandaOmics) with generative chemistry (Chemistry42) to investigate CDK20 inhibition in HCC, discovering a nanomolar hit in just 30 days using an AI-driven protein-structure prediction system (AlphaFold), later confirmed in vivo.

Treatment response

AI/ML supports a response-adaptive therapeutic approach, guiding drug choice for optimised personalised care whilst preventing toxicity. Using images of human liver organoids, Tan et al.97 created a spatiotemporal DL model which performed ternary DILI grading, identifying toxic compounds that standard spheroid assays miss. Other models were developed to anticipate hepatotoxicity98, differentiate animal-only toxicities99, prioritise synergistic drug combinations100, or assess treatment efficacy in population subsets in silico. For example, clinical benefits of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (AB) immune checkpoint inhibitors have been observed in patients with unresectable HCC101. Zeng et al.102 used H&E pathomics to derive an immune AB response signature and identify patients with longer progression-free survival, while Vithayathil et al.83 externally validated a model incorporating pre-treatment CT radiomics and clinical features predicting 12-month mortality risk on AB, successfully stratifying response rates and outperforming traditional risk scores.

Beyond cancer, Fan et al.103 developed a novel tool for AVTs assessment by turning longitudinal serum quantitative HBV surface antigen trajectories into individualised antigen-loss probabilities, identifying ~8–10% of patients with high probability of viral clearance. External validation in clinical trials confirmed that “favourable” patients had markedly higher treatment response104. Finally, Yang et al.105 constructed a multiomic model predicting suboptimal biochemical response in PBC/AIH variant syndrome, highlighting dysregulated lipid metabolism and immune (e.g., IL-4/IL-22) pathways as key pathogenic factors, enabling timely escalation in likely non-responders.

Lifestyle interventions

AI/ML has the potential to identify effective and actionable lifestyle changes. While an independent audit of ChatGPT meal plans for MASLD found plausible weight loss advice but frequent mistakes and guideline omissions106, Joshi et al.107 showed in a 1-year randomised trial that an AI “digital twin” delivering personalised nutrition, physical activity, and sleep schedule recommendations improved MASLD liver-fat and fibrosis scores more than standard care.

Other opportunities

AI is increasingly integrated into routine healthcare workflows, often functioning as a support tool or “co-pilot” for clinicians or patients (Fig. 3), thereby maintaining human oversight.

Conceptual flowchart illustrating where patients and clinicians interface with Artificial Intelligence (AI) across the care continuum, from pre-visit planning and triage, through admission, consults and interventions, to at-home support, applied biomedical research and clinical trials, and finally communication. Throughout the journey, clinician-directed co-intelligence intakes all or selected inputs, executes routine or targeted tasks, and returns outputs to care teams or patients under clinical oversight, thus supporting, not supplanting, clinical judgement. SDoH social determinants of health, EHRs electronic health records (EHRs), Q&A question and answer.

Clinical co-pilots

LiVersa, a liver-specific large language model (LLM) built from ~30 AASLD guidance documents, correctly answered a trainee HBV/HCC knowledge set, generating more specific outputs than ChatGPT108. Related, LiVersa could also accurately extract structured elements from HCC imaging reports in a head-to-head comparison with manual reviewers109. A more generalist domain-specific vision language model for pathology, PathChat, was also recently introduced110. Beyond text extraction, Xu et al.111 demonstrated that LLMs (GPT-4, Gemini) achieved near-expert accuracy in predicting immunotherapy response for unresectable HCC. Parallel work developed a radiomics-DL-LLM agent for personalised HCC treatment planning112. In the operating room, LiverColor, a smartphone app using CNN architecture for colour and texture analysis, could classify steatosis in liver grafts in <5 s, outperforming surgeons for >15% steatosis, although performance at >30% remained limited by sample size113.

Clinical trials

AI/ML is also helping to reshape clinical trials. NASHmap, an EHR-based XGBoost model using 14 routine variables, accurately predicted biopsy-confirmed MASH and, when applied to ~2.9 million at-risk adults, identified 31% as probable MASH, representing a pragmatic pre-screening recruitment tool114. Within digital histopathology, AIM-MASH automated eligibility and endpoint scoring with agreement comparable to expert consensus, also detecting a greater proportion of treatment responders than central readers115. In February 2025, the European Medicines Agency issued a Qualification Opinion allowing AIM-MASH as an aid to single central pathologists for Phase 2/3 enrolment and histology-based endpoint evaluation116. Across ~1400 biopsies from four trials, AI-assisted pathologists outperformed independent manual readers for key histological components while remaining non-inferior for steatosis and fibrosis117.

Social determinants of health

AI/ML is increasingly able to capture social determinants of health (SDoH) from clinical notes, helping identify access gaps, support model fairness, and build more diverse cohorts. In MASLD, factors such as education, food insecurity, and marital status are linked to higher disease burden48,118,119,120, underscoring the need for equity-aware study design. For example, Wang et al.121 showed that Black-White performance gaps in 1-year mortality prediction across chronic diseases (including CLD) disappeared once SDoH were balanced. In LT, Robitschek et al.122 used a LLM to extract 23 psychological/SDoH factors from evaluation notes, improving prediction of listing outcomes and elucidating drivers of transplant decisions.

Challenges of AI

Despite promising results for the use of AI/ML to improve care in hepatology, there are limitations to address before real-world clinical adoption.

Technical challenges

Most AI models in hepatology are built on retrospective, single-centre cohorts or public registries with narrow demographics and limited follow-up, making them prone to overfitting, with poor generalisability and limited transparency123.

Data quality remains a major bottleneck, as label noise (e.g., biopsy sampling errors, inter-observer variability) and inconsistent preprocessing pipelines (e.g., imaging protocols, EHR completeness) undermine reliability and standardisation124. Furthermore, the addition of high heterogeneity of real-world hepatology populations (i.e., variable aetiologies, disease prevalence, demographics), evolving clinical practice guidelines, and limited adherence to evaluation and reporting standards (e.g., TRIPOD + AI125, CONSORT-AI126, DECIDE-AI127) all complicate model reproducibility. Additional challenges are posed by dataset and concept shifts, where differences between training datasets and real-world populations may degrade model performance128. Multi-centre validation and continuous post-deployment monitoring for calibration drift (the gradual loss of accuracy in measurements or predictions over time) are therefore essential to maintain long-lasting clinical reliability.

Clinical credibility of AI depends on rigorous evaluation and transparency. Where possible, prospective or “AI-in-the-loop” randomised trials comparing AI-assisted and standard care are essential to determine true clinical benefit. Such studies have been piloted in liver imaging but remain uncommon. Assessing model interpretability and explainability helps explain which features drive predictions and whether models rely on spurious or biased patterns. For example, outputs may be influenced more by fibrosis stage or demographic factors than by disease biology itself. Techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) or Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) provide post hoc insight into model reasoning, while attention or saliency maps visually highlight image regions most influencing a prediction129.

Overall, when data are limited, simpler models may outperform deep networks, which often sacrifice transparency for marginal accuracy gains5. Beyond architecture, reliable AI deployment requires quantifying uncertainty and the ability to “abstain” in low-confidence cases, a critical safeguard for clinical integration130. No single modelling approach is universally superior. Robust feature selection, transfer or self-supervised learning, and systematic sensitivity analyses are essential for producing interpretable and reproducible biomarkers131. Equally, LLMs introduce additional risks, including hallucinations, prompt sensitivity, and over-confident errors132, underscoring the need for task-specific evaluation, transparent data sourcing, and human oversight.

Regulatory complexity

Regulation of medical AI is progressing but remains uneven across regions. In the EU, the AI Act introduces rules in stages, with bans on unacceptable uses and AI literacy measures from 2024, general-purpose AI rules from 2025, and “high-risk” medical device standards phased in through 2026–2027133. In the US, the FDA’s Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCPs) allow pre-authorised post-market model updates for AI-enabled software, supporting safer iteration and adaptation134. In the UK, MHRA’s “Software and AI as a Medical Device” framework defines expectations for development and post-market monitoring135.

Data privacy remains a major challenge for multi-centre research. Under the EU GDPR, secondary use of health data requires clear legal grounds. The European Health Data Space aims to streamline data sharing136, although coordination remains complex. Privacy-preserving approaches, such as federated learning, may help, particularly for rare and paediatric liver diseases where cohorts are small137. Despite these efforts, uncertainty persists about when AI/ML tools qualify as medical devices and how best to assess their safety, effectiveness, and fairness. Divergent regulations slow adoption and deter investment138.

Finally, data privacy and patient safety are closely linked. US and EU regulators now emphasise “secure-by-design” AI systems to counter growing cyber risks139,140. Demonstrations that manipulated medical images can mislead both clinicians and algorithms141, underscores the need for verification tools and secure data pipelines.

Ethical limitations

Without safeguards, AI/ML can amplify existing inequities in hepatology. Minority ethnic groups, women, and non-represented cohorts have been systematically disadvantaged by MELD-based LT prioritisation142, HCC risk modelling143, and other predictive tools. Bias mitigation requires diverse training across ethnicity, sex, and socioeconomic strata, subgroup calibration, transparent equity reporting, and post-deployment audits144.

Importantly, accountability for AI-driven decisions is still unclear. The EU AI Act assigns responsibilities to developers and users of high-risk medical AI145, but US PCCPs leave liability unresolved134, often defaulting to clinicians. Clearer rules on who is responsible are needed in governance and public communication.

AI also has an environmental impact. Data centres already account for ~1.5% of global electricity use, projected to more than double by 2030146. Training GPT3 alone was estimated to consume ~700,000 litres of cooling water147. With health systems like the NHS beginning to mandate disclosure of environmental costs148, sustainability must become integral to medical AI deployment.

Clinical integration

Two main barriers hinder clinical integration: an evidence gap (few large, prospective, multi-centre trials) and a deployment gap (limited integration of AI into workflows). Without transparency, clinicians often revert to familiar statistical tools or user-friendly chatbots valued for convenience over accuracy. A recent EASL consensus identified key requirements for adoption, including demonstrated clinical benefit, rigorous prospective validation, and benchmarking against best statistical baselines. Despite enthusiasm, only ~4% of EASL 2024 abstracts used AI/ML, reflecting early adoption in hepatology149. Ongoing concerns include clinician distrust, regulatory uncertainty, and poor system interoperability. Facilitators include interdisciplinary collaboration, shared data resources, sustainable funding, and improved AI literacy. Positioning AI as “assistive” rather than “autonomous” may also reduce workforce anxiety. However, lessons from EHR adoption warn that poorly integrated systems can add to clinician workload150.

Beyond these structural challenges lies a more subtle concern: preserving clinical expertise amid growing algorithmic support. Senior clinicians increasingly question how future specialists will develop skills if AI shortens traditional learning pathways. In a recent multi-centre study, continuous exposure to AI-assisted polyp detection led to reduced performance during subsequent unassisted colonoscopies151, suggesting early signs of deskilling. Mitigation requires deliberate integration strategies, embedding AI as a co-pilot rather than a replacement, maintaining unassisted practice, and ensuring ongoing skill calibration. Targeted education and hybrid training (with/without AI support) are essential to preserve sound clinical judgment.

Health economics

Cost-saving claims for AI/ML tools in hepatology remain largely speculative. Existing evaluations are scarce, methodologically inconsistent, and rarely patient-centred152. The potential system-level value lies in earlier detection, workflow automation (e.g., radiology/histopathology quantification), and risk-based triage using EHR data. Of note, while commercial models (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude) may incur licensing costs, the main financial burden of medical AI stems from infrastructure, integration, validation, and governance rather than model access itself.

Experts emphasise early involvement of health economists to design robust cost-effectiveness studies that capture true implementation costs, effects on clinician time and workflow, and downstream resource reallocation, while avoiding costs from misclassification. Such evidence is essential to establish both financial and clinical viability, particularly in resource-limited settings153.

Conclusion

Centred on the patient, the AI/ML lifecycle (spanning purpose, population, data, model development, validation, and deployment) offers a pragmatic framework for hepatology. Applied responsibly, multimodal data integration and assistive algorithms can enable earlier diagnosis, more accurate prognosis, and personalised therapy. Successful clinical translation will depend on generalisability, transparency, and longitudinal performance monitoring to detect drift, alongside robust privacy, security and equity safeguards, clear demonstration of health economic value, and workflow-embedded human oversight, to shift liver care from reactive to proactive.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Devarbhavi, H. et al. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 79, 516–537 (2023).

King, J. et al. Identifying emergency presentations of chronic liver disease using routinely collected administrative hospital data. JHEP Rep. 7, 101322 (2025).

Ma, C. et al. Trends in the economic burden of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis in the United States: 1996–2016. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 116, 2060–2067 (2021).

Kalapala, R., Rughwani, H. & Reddy, D. N. Artificial intelligence in hepatology- ready for the primetime. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 13, 149–161 (2023).

Schattenberg, J. M., Chalasani, N. & Alkhouri, N. Artificial intelligence applications in hepatology. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 2015–2025 (2023).

Kendall, T. J. et al. An integrated gene-to-outcome multimodal database for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Nat. Med. 29, 2939–2953 (2023).

Yashaswini, G. N. et al. Deep learning technique for automatic liver and liver tumor segmentation in CT images. J. Liver Transplant. 17, 100251 (2025).

N, Y. G. & R V, M. Automatic liver tumor classification using UNet70 a deep learning model. J. Liver Transplant. 18, 100260 (2025).

Ai, H., Huang, Y., Tai, D.-I., Tsui, P.-H. & Zhou, Z. Ultrasonic assessment of liver fibrosis using one-dimensional convolutional neural networks based on frequency spectra of radiofrequency signals with deep learning segmentation of liver regions in B-mode images: a feasibility study. Sensors 24, 5513 (2024).

Zha, J. et al. Fully automated hybrid approach on conventional MRI for triaging clinically significant liver fibrosis: a multi-center cohort study. J. Med. Virol. 96, e29882 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Diagnostic of fatty liver using radiomics and deep learning models on non-contrast abdominal CT. PLoS ONE 20, e0310938 (2025).

Alshagathrh, F. et al. Hybrid deep learning and machine learning for detecting hepatocyte ballooning in liver ultrasound images. Diagnostics 14, 2646 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Hepatic and portal vein segmentation with dual-stream deep neural network. Med. Phys. 51, 5441–5456 (2024).

Hou, B. et al. Deep learning segmentation of ascites on abdominal CT Scans for automatic volume quantification. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 6, e230601 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. MCAUnet: a deep learning framework for automated quantification of body composition in liver cirrhosis patients. BMC Med. Imaging 25, 215 (2025).

Ercan, C. et al. A deep-learning-based model for assessment of autoimmune hepatitis from histology: AI(H). Virchows Arch. 485, 1095–1105 (2024).

Cazzaniga, G. et al. Automating liver biopsy segmentation with a robust, open-source tool for pathology research: the HOTSPoT model. npj Digit. Med. 8, 455 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Deep learning-based accurate diagnosis and quantitative evaluation of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma on whole-slide histopathology images. Cancer Med. 13, e7104 (2024).

Ratziu, V. et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted digital pathology for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: current status and future directions. J. Hepatol. 80, 335–351 (2024).

Sharma, A., Khade, T. & Satapathy, S. M. A cross dataset meta-model for hepatitis C detection using multi-dimensional pre-clustering. Sci. Rep. 15, 7278 (2025).

Chang, D. et al. Machine learning models are superior to noninvasive tests in identifying clinically significant stages of NAFLD and NAFLD-related cirrhosis. Hepatology 77, 546–557 (2023).

Sherman, M. S. et al. A natural language processing algorithm accurately classifies steatotic liver disease pathology to estimate the risk of cirrhosis. Hepatol. Commun. 8, e0403 (2024).

Oh, S. et al. Identification of signature gene set as highly accurate determination of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease progression. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 30, 247–262 (2024).

Ouyang, G. et al. Identification and validation of potential diagnostic signature and immune cell infiltration for NAFLD based on cuproptosis-related genes by bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front. Immunol. 14, 1251750 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Integrative analysis identifies oxidative stress biomarkers in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via machine learning and weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Front. Immunol. 15, 1335112 (2024).

Cao, C. et al. Identification and validation of efferocytosis-related biomarkers for the diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis based on bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front. Immunol. 15, 1460431 (2024).

Xie, H., Wang, J. & Zhao, Q. Identification of potential metabolic biomarkers and immune cell infiltration for metabolic associated steatohepatitis by bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Sci. Rep. 15, 16596 (2025).

Tavaglione, F., Marafioti, G., Romeo, S. & Jamialahmadi, O. Machine learning reveals the contribution of lipoproteins to liver triglyceride content and inflammation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 110, 218–227 (2024).

Feng, G. et al. Novel urinary protein panels for the non-invasive diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and fibrosis stages. Liver Int. 43, 1234–1246 (2023).

Hou, M. et al. Innovative machine learning approach for liver fibrosis and disease severity evaluation in MAFLD patients using MRI fat content analysis. Clin. Exp. Med. 25, 275 (2025).

Trifylli, E. M. et al. Extracellular vesicles as biomarkers for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease staging using explainable artificial intelligence. World J. Gastroenterol. 31, 106937 (2025).

Zhang, Z.-M. et al. Development of machine learning-based predictors for early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 14, 5274 (2024).

Deng, Z. et al. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma via no end-repair enzymatic methylation sequencing of cell-free DNA and pre-trained neural network. Genome Med. 15, 93 (2023).

Sanchez, J. I. et al. Metabolomics biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma in a prospective cohort of patients with cirrhosis. JHEP Rep. 6, 101119 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. A distinct microbiota signature precedes the clinical diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut Microbes 15, 2201159 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Five miRNAs identified in fucosylated extracellular vesicles as non-invasive diagnostic signatures for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Rep. Med. 5, 101716 (2024).

Huang, F. et al. From gut to liver: unveiling the differences of intestinal microbiota in NAFL and NASH patients. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1366744 (2024).

Park, I. et al. Gut microbiota-based machine-learning signature for the diagnosis of alcohol-associated and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Sci. Rep. 14, 16122 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Development and validation of a novel model to discriminate idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury and autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 45, e16239 (2025).

Olianas, A. et al. Top-down proteomics detection of potential salivary biomarkers for autoimmune liver diseases classification. IJMS. 24, 959 (2023).

Gerussi, A. et al. Deep learning helps discriminate between autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cholangitis. JHEP Rep. 7, 101198 (2025).

Calderaro, J. et al. Deep learning-based phenotyping reclassifies combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 14, 8290 (2023).

Liu, N. et al. Differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma from intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma through MRI radiomics. Cancers 15, 5373 (2023).

Xie, P. et al. Preoperative ternary classification using DCE-MRI radiomics and machine learning for HCC, ICC, and HIPT. Insights Imaging 16, 178 (2025).

Wei, Y. et al. Focal liver lesion diagnosis with deep learning and multistage CT imaging. Nat. Commun. 15, 7040 (2024).

Rinella, M. E. et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 77, 1797–1835 (2023).

Zhu, G. et al. Machine learning models for predicting metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease prevalence using basic demographic and clinical characteristics. J. Transl. Med. 23, 381 (2025).

Hong, Y. et al. Machine learning prediction of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease risk in American adults using body composition: explainable analysis based on SHapley Additive exPlanations. Front. Nutr. 12, 1616229 (2025).

Liu, L. et al. Automated machine learning models for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease assessed by controlled attenuation parameter from the NHANES 2017–2020. Digit. Health 10, 20552076241272535 (2024).

Yu, Y., Yang, Y., Li, Q., Yuan, J. & Zha, Y. Predicting metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease using explainable machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 15, 12382 (2025).

Njei, B., Osta, E., Njei, N., Al-Ajlouni, Y. A. & Lim, J. K. An explainable machine learning model for prediction of high-risk nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci. Rep. 14, 8589 (2024).

Lu, H. et al. Identification of hub gene for the pathogenic mechanism and diagnosis of MASLD by enhanced bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. PLoS ONE 20, e0324972 (2025).

Huang, Q. et al. A metabolome-derived score predicts metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and mortality from liver disease. J. Hepatol. 82, 781–793 (2025).

Lai, M. et al. Serum protein risk stratification score for diagnostic evaluation of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis. Hepatol. Commun. 8, e0586 (2024).

Reddy, K. R. et al. Incidence and risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: the multicenter hepatocellular carcinoma early detection strategy (HEDS) study. Gastroenterology 165, 1053–1063.e6 (2023).

Guo, C. et al. Machine-learning–based plasma metabolomic profiles for predicting long-term complications of cirrhosis. Hepatology 81, 168–180 (2025).

Nakatsuka, T. et al. Deep learning and digital pathology powers prediction of HCC development in steatotic liver disease. Hepatology 81, 976–989 (2025).

Sarkar, S. et al. A machine learning model to predict risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Gastro Hep Adv. 3, 498–505 (2024).

Huang, X. et al. Machine learning–based pathomics model predicts angiopoietin-2 expression and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 195, 561–574 (2025).

Li, M. et al. Integrated multi-omics analysis and machine learning refine molecular subtypes and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma through O-linked glycosylation genes. Funct. Integr. Genom. 25, 162 (2025).

Wu, T. et al. Machine learning-based model used for predicting the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B. JHC 12, 659–670 (2025).

Nakahara, H. et al. Prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatitis c virus sustained virologic response using a random survival forest model. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. e2400108 https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.24.00108 (2024).

Tran, B. V. et al. Development and validation of a REcurrent Liver cAncer Prediction ScorE (RELAPSE) following liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of the US Multicenter HCC Transplant Consortium. Liver Transplant. 29, 683–697 (2023).

Li, Y.-H. et al. Preoperative model for predicting early recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients using radiomics and deep learning: a multicenter study. World J. Gastrointest Oncol. 17, 106608 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Denoised recurrence label-based deep learning for prediction of postoperative recurrence risk and sorafenib response in HCC. BMC Med. 23, 162 (2025).

Wu, W. et al. Exploration of heterogeneity and recurrence signatures in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 19, 2388–2411 (2025).

Wang, W. et al. A Transformer-Based microvascular invasion classifier enhances prognostic stratification in HCC following radiofrequency ablation. Liver Int. 44, 894–906 (2024).

Qu, W.-F. et al. Development of a deep pathomics score for predicting hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation. Hepatol. Int. 17, 927–941 (2023).

Singh, Y., Faghani, S., Eaton, J. E., Venkatesh, S. K. & Erickson, B. J. Deep learning–based prediction of hepatic decompensation in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis with computed tomography. Mayo Clin. Proc. Digit. Health 2, 470–476 (2024).

Singh, Y., Eaton, J. E., Venkatesh, S. K. & Erickson, B. J. Computed tomography-based radiomics and body composition model for predicting hepatic decompensation. Oncotarget 15, 809–813 (2024).

Kim, B. K. et al. Magnetic resonance elastography-based prediction model for hepatic decompensation in NAFLD: a multicenter cohort study. Hepatology 78, 1858–1866 (2023).

Kosick, H. M.-K. et al. Machine learning models using non-invasive tests & B-mode ultrasound to predict liver-related outcomes in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Sci. Rep. 15, 24579 (2025).

Du, M. et al. Enhancing diagnostic accuracy for HBV-related cirrhosis progression: predictive modeling using combined Golgi protein 73 and α1-microglobulin for the transition from nondecompensated to decompensated cirrhosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 37, 961–969 (2025).

Zhong, X. et al. Methodological explainability evaluation of an interpretable deep learning model for post-hepatectomy liver failure prediction incorporating counterfactual explanations and layerwise relevance propagation: a prospective in silico trial. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2408.03771 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Learning-based early detection of post-hepatectomy liver failure using temporal perioperative data: a nationwide multicenter retrospective study in China. eClinicalMedicine 83, 103220 (2025).

Veldhuizen, G. P. et al. Deep learning can predict cardiovascular events from liver imaging. JHEP Rep. 7, 101427 (2025).

Sun, D.-Q. et al. Liver fibrosis progression analyzed with AI predicts renal decline. JHEP Rep. 7, 101358 (2025).

Sharma, D. et al. GraftIQ: hybrid multi-class neural network integrating clinical insight for multi-outcome prediction in liver transplant recipients. Nat. Commun. 16, 4943 (2025).

Chichelnitskiy, E. et al. Plasma immune signatures can predict rejection-free survival in the first year after pediatric liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 81, 862–871 (2024).

Shao, W. et al. Key genes and immune pathways in T-cell mediated rejection post-liver transplantation identified via integrated RNA-seq and machine learning. Sci. Rep. 14, 24315 (2024).

Lin, Y. et al. An integrated proteomics and metabolomics approach to assess graft quality and predict early allograft dysfunction after liver transplantation: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 110, 3480–3494 (2024).

Xia, Y. et al. CT-based multimodal deep learning for non-invasive overall survival prediction in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with immunotherapy. Insights Imaging 15, 214 (2024).

Vithayathil, M. et al. Machine learning based radiomic models outperform clinical biomarkers in predicting outcomes after immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. S0168827825002442 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2025.04.017 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. Combining WGCNA and machine learning to construct immune-related EMT patterns to predict HCC prognosis and immune microenvironment. Aging 15, 7146–7160 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Deep learning models for predicting the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma based on a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 13232 (2024).

Lee, H.-H. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and risk of cardiovascular disease. Gut https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2023-331003 (2023).

Drozdov, I., Szubert, B., Rowe, I. A., Kendall, T. J. & Fallowfield, J. A. Accurate prediction of all-cause mortality in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease using electronic health records. Ann. Hepatol. 29, 101528 (2024).

Lei, C. et al. 28-day all-cause mortality in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: a machine learning prediction model based on the MIMIC-IV. Clin. Exp. Med. 25, 198 (2025).

Dunn, W. et al. An artificial intelligence-generated model predicts 90-day survival in alcohol-associated hepatitis: a global cohort study. Hepatology 80, 1196–1211 (2024).

Gao, J., Xu, C. & Zhu, J. Towards personalized medicine for chronic liver disease. JPM 13, 1432 (2023).

Wen, W. & Wang, R. Consensus artificial intelligence-driven prognostic signature for predicting the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-center and large-scale study. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 207 (2025).

Sun, J. et al. Identification of CACNB1 protein as an actionable therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma via metabolic dysfunction analysis in liver diseases: an integrated bioinformatics and machine learning approach for precise therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 308, 142315 (2025).

Venhorst, J. et al. Integrating text mining with network models for successful target identification: in vitro validation in MASH-induced liver fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1442752 (2024).

Snir, T. et al. Machine learning identifies key proteins in primary sclerosing cholangitis progression and links high CCL24 to cirrhosis. IJMS 25, 6042 (2024).

CM-101 in PSC patients-the SPRING study. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04595825 (2024).

Ren, F. et al. AlphaFold accelerates artificial intelligence powered drug discovery: efficient discovery of a novel CDK20 small molecule inhibitor. Chem. Sci. 14, 1443–1452 (2023).

Tan, S. et al. Development of an AI model for DILI-level prediction using liver organoid brightfield images. Commun. Biol. 8, 886 (2025).

Mostafa, F., Howle, V. & Chen, M. Machine learning to predict drug-induced liver injury and its validation on failed drug candidates in development. Toxics 12, 385 (2024).

Seal, S. et al. Improved detection of drug-induced liver injury by integrating predicted in vivo and in vitro data. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 37, 1290–1305 (2024).

Zhang, F., Zhao, X., Wei, J. & Wu, L. PathSynergy: a deep learning model for predicting drug synergy in liver cancer. Brief. Bioinform. 26, bbaf192 (2025).

Finn, R. S. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1894–1905 (2020).

Zeng, Q. et al. Artificial intelligence-based pathology as a biomarker of sensitivity to atezolizumab-bevacizumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 24, 1411–1422 (2023).

Fan, R. et al. High accuracy model for HBsAg loss based on longitudinal trajectories of serum qHBsAg throughout long-term antiviral therapy. Gut 73, 1725–1736 (2024).

Liao, X. et al. External validation of the GOLDEN model for predicting HBsAg loss in noncirrhotic chronic hepatitis B patients with interferon-alpha-based therapy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. S1542-3565(25)00524–5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2025.06.005 (2025).

Yang, F. et al. Multi-omics approaches for drug-response characterization in primary biliary cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis variant syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 22, 214 (2024).

Ozlu Karahan, T., Kenger, E. B. & Yilmaz, Y. Artificial intelligence-based diets: a role in the nutritional treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 38, e70033 (2025).

Joshi, S. et al. Digital twin-enabled personalized nutrition improves metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes: results of a 1-year randomized controlled study. Endocr. Pract. 29, 960–970 (2023).

Ge, J. et al. Development of a liver disease-specific large language model chat interface using retrieval-augmented generation. Hepatology 80, 1158–1168 (2024).

Ge, J., Li, M., Delk, M. B. & Lai, J. C. A comparison of a large language model vs manual chart review for the extraction of data elements from the electronic health record. Gastroenterology 166, 707–709.e3 (2024).

Lu, M. Y. et al. A multimodal generative AI copilot for human pathology. Nature 634, 466–473 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Predicting immunotherapy response in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparative study of large language models and human experts. J. Med. Syst. 49, 64 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. A multimodal LLM-agent framework for personalized clinical decision-making in hepatocellular carcinoma. Patterns 101364 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2025.101364 (2025).

Piella, G. et al. LiverColor: an artificial intelligence platform for liver graft assessment. Diagnostics 14, 1654 (2024).

Schattenberg, J. M. et al. NASHmap: clinical utility of a machine learning model to identify patients at risk of NASH in real-world settings. Sci. Rep. 13, 5573 (2023).

Iyer, J. S. et al. AI-based automation of enrollment criteria and endpoint assessment in clinical trials in liver diseases. Nat. Med. 30, 2914–2923 (2024).

EMA qualifies first artificial intelligence tool to diagnose inflammatory liver disease (MASH) in biopsy samples. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-qualifies-first-artificial-intelligence-tool-diagnose-inflammatory-liver-disease-mash-biopsy-samples (2025).

Pulaski, H. et al. Clinical validation of an AI-based pathology tool for scoring of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Nat. Med. 31, 315–322 (2025).

Singh, V., Cheng, S., Velazquez, A., Trivedi, H. D. & Kwan, A. C. The impact of Social Determinants of Health on Metabolically Dysfunctional-Associated Steatotic liver disease among adults in the United States. JCM 14, 5484 (2025).

Huang, L., Luo, Y., Zhang, L., Wu, M. & Hu, L. Machine learning-based disease risk stratification and prediction of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease using vibration-controlled transient elastography: result from NHANES 2021–2023. BMC Gastroenterol. 25, 255 (2025).

Unalp-Arida, A. & Ruhl, C. E. Prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and fibrosis defined by liver elastography in the United States using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-March 2020 and August 2021-August 2023 data. Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1097/HEP.0000000000001211 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Assessing fairness in machine learning models: a study of racial bias using matched counterparts in mortality prediction for patients with chronic diseases. J. Biomed. Inf. 156, 104677 (2024).

Robitschek, E. et al. A large language model-based approach to quantifying the effects of social determinants in liver transplant decisions. npj Digit. Med. 8, 665 (2025).

Zhang, J. et al. Moving towards vertically integrated artificial intelligence development. npj Digit. Med. 5, 143 (2022).

Wei, Y. et al. Deep learning with noisy labels in medical prediction problems: a scoping review. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 31, 1596–1607 (2024).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ e078378 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-078378 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. Nat. Med. 26, 1364–1374 (2020).

Vasey, B. et al. Reporting guideline for the early-stage clinical evaluation of decision support systems driven by artificial intelligence: DECIDE-AI. Nat. Med. 28, 924–933 (2022).

Sahiner, B., Chen, W., Samala, R. K. & Petrick, N. Data drift in medical machine learning: implications and potential remedies. Br. J. Radiol. 96, 20220878 (2023).

Hassija, V. et al. Interpreting black-box models: a review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 16, 45–74 (2024).

Kompa, B., Snoek, J. & Beam, A. L. Second opinion needed: communicating uncertainty in medical machine learning. npj Digit. Med. 4, 4 (2021).

Ghosh, S., Zhao, X., Alim, M., Brudno, M. & Bhat, M. Artificial intelligence applied to ’omics data in liver disease: towards a personalised approach for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Gut 74, 295–311 (2025).

Asgari, E. et al. A framework to assess clinical safety and hallucination rates of LLMs for medical text summarisation. npj Digit. Med. 8, 274 (2025).

AI Act. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai (2024).

Marketing submission recommendations for a predetermined change control plan for artificial intelligence-enabled device software functions. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/marketing-submission-recommendations-predetermined-change-control-plan-artificial-intelligence (2025).

Software and AI as a medical device change programme roadmap. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/software-and-ai-as-a-medical-device-change-programme/software-and-ai-as-a-medical-device-change-programme-roadmap (2023).

European Health Data Space Regulation (EHDS). https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/european-health-data-space-regulation-ehds_en (2025).

Balsano, C. et al. Artificial Intelligence and liver: opportunities and barriers. Digest. Liver Dis. 55, 1455–1461 (2023).

Malik, S., Das, R., Thongtan, T., Thompson, K. & Dbouk, N. AI in hepatology: revolutionizing the diagnosis and management of liver disease. J. Clin. Med. 13, 7833 (2024).

Cybersecurity in medical devices: quality system considerations and content of premarket submissions; guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff; Availability. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/06/27/2025-11669/cybersecurity-in-medical-devices-quality-system-considerations-and-content-of-premarket-submissions (2025).

MDCG 2019-16 Rev.1 Guidance on Cybersecurity for medical devices. https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/md_cybersecurity_en.pdf (2020).

Mirsky, Y., Mahler, T., Shelef, I. & Elovici, Y. CT-GAN malicious tampering of 3d medical imagery using deep learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1901.03597 (2019).

Walter Costa, M. B. et al. Revising the MELD score to address sex-bias in liver transplant prioritization for a German cohort. J. Pers. Med. 13, 963 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Developing deep learning-based strategies to predict the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease from electronic health records. J. Biomed. Inf. 152, 104626 (2024).

Clusmann, J. et al. The barriers for uptake of artificial intelligence in hepatology and how to overcome them. J. Hepatol. S0168827825023372 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2025.07.003 (2025).

REGULATION (EU) 2024/1689 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ%3AL_202401689&utm (2024).

Energy and AI: executive summary. https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai/executive-summary? (2025).

Li, P., Yang, J., Islam, M. A. & Ren, S. Making AI less ‘thirsty’: uncovering and addressing the secret water footprint of AI models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.03271 (2025).

Delivering a net zero NHS. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/a-net-zero-nhs/ (2022).

Žigutytė, L., Sorz-Nechay, T., Clusmann, J. & Kather, J. N. Use of artificial intelligence for liver diseases: a survey from the EASL congress 2024. JHEP Rep. 6, 101209 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Artificial intelligence and radiologist burnout. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2448714 (2024).

Budzyń, K. et al. Endoscopist deskilling risk after exposure to artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: a multicentre, observational study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 896–903 (2025).

Kastrup, N., Holst-Kristensen, A. W. & Valentin, J. B. Landscape and challenges in economic evaluations of artificial intelligence in healthcare: a systematic review of methodology. BMC Digit. Health 2, 39 (2024).

Elvidge, J. & Dawoud, D. Reporting standards to support cost-effectiveness evaluations of AI-driven health care. Lancet Digit. Health 6, e602–e603 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Ailish McCafferty-Brown (Centre for Inflammation Research, Institute for Regeneration and Repair, University of Edinburgh) for assistance. S.M.G.M. is funded by the Medical Research Council (Doctoral Training Programme in Precision Medicine). S.W. is funded by a Medical Research Scotland PhD studentship. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a creative commons attribution (CC BY) licence to any author-accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.G.M. researched data and conceptualised the article. S.M.G.M., S.W., T.J.K., I.N.G. and J.A.F. contributed substantially to discussion of the content. S.M.G.M., T.J.K. and J.A.F. wrote the initial article draft. S.M.G.M. and S.W. produced the display items. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.J.K. serves as a consultant or advisory board member for Resolution Therapeutics, Clinnovate Health, HistoIndex, Fibrofind, Kynos Therapeutics, Perspectum, Concept Life Sciences, Servier Laboratories, Taiho Oncology, Roche, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals, has received speakers’ fees from Servier Laboratories, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Astrazeneca, HistoIndex, and Incyte Corporation. J.A.F. serves as a consultant and/or advisory board member for Resolution Therapeutics, Kynos Therapeutics, Gyre Therapeutics, Ipsen, River 2 Renal Corp., Stimuliver, Guidepoint and ICON plc, has received speakers’ fees from HistoIndex, Resolution Therapeutics and Société internationale de développement professionnel continu Cléo and research grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Genentech. S.M.G.M., S.W., and I.N.G. declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morel, S.M.G., Wu, S., Kendall, T.J. et al. Opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in hepatology. npj Gut Liver 3, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44355-025-00052-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44355-025-00052-w