Abstract

Recent measles outbreaks in the USA have emerged despite the availability of the highly effective measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine. Current surveillance systems rely primarily on telephone surveys with provider verification or school-entry data, methods prone to incompleteness and systematic exclusion of vulnerable populations. Here, to address these limitations, we used a validated digital participatory surveillance platform to collect parental reports of ≥1-dose MMR vaccination among children under 5 years of age. Applying Small Area Estimation methods to generate granular, county-level coverage estimates nationwide, we found substantial geographic variation, including areas with MMR coverage <60%. Analysis of spatial clustering revealed hotspots of undervaccination overlapping closely with recent measles outbreaks, particularly in Texas and New Mexico—where our model estimates substantially lower vaccine coverage than official data. These findings underscore the urgent need for surveillance systems to include more granular and timely data that accurately identify undervaccinated communities, enabling targeted, timely public health interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The USA is experiencing a resurgence of measles1, despite the widespread availability of the safe and effective measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine. Multiple states reported cases in 2025, notably concentrated in western Texas and New Mexico. Declining MMR coverage, fuelled by multifaceted vaccine hesitancy2 and pandemic-related disruption3, has left national coverage below thresholds required to prevent sustained transmission4,5. Differences in vaccination coverage by geographic, socioeconomic and demographic factors have further contributed to pockets of vulnerability6,7,8, particularly in communities with lower MMR vaccine rates.

Effective public health interventions require timely, spatially granular surveillance data. However, existing US vaccination surveillance systems face notable limitations, including reporting delays, coarse geographic resolution (often reported only at the state level4) and reliance on milestones assessment at 24 and 36 months or kindergarten entry. These estimates typically depend on healthcare provider-verified, school or health department records4,5,9,10, which systematically underrepresent children who are homeschooled, uninsured or foreign-born, or face structural barriers to care—groups that historically have shown undervaccination11,12,13. Consequently, the existing system provides an incomplete picture of the true vaccine coverage, omitting key subpopulations and underestimating local vulnerability14.

Most official vaccination estimates focus on kindergarten-entry requirements, subject to state-exemption policies4, leaving younger children—who are more vulnerable to severe measles complications—poorly presented. In Texas, for example, the statewide kindergarten MMR uptake for the 2024–2025 school year was reported at 93.2%, near the herd-immunity threshold15, yet West Texas is currently experiencing a measles outbreak. Such aggregated figures may obscure local immunity gaps, especially among children too young for school entry or those facing barriers to care. National case reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) echo this concern: in 2025, nearly 30% of US measles cases occurred among children under 5 years of age, who also had the highest hospitalization rate (21%), while over 90% of all cases were in unvaccinated individuals1. The reliance on school-based reporting and state-specific data systems makes it difficult to construct a timely, unified national picture of measles immunity.

To address these gaps, we used a validated digital participatory surveillance platform OutbreaksNearMe (ONM)16,17 and Small Area Estimation (SAE) framework18,19 methods to generate publicly available county-level estimates of MMR vaccination coverage (≥1 dose) for children under 5 across the contiguous USA. We then leverage a geographic artificial intelligence (AI) foundation model to super-resolve these findings to a finer spatial scale.

Our approach complements existing surveillance systems, including recently published county-level reports of two-dose MMR coverage20, by better capturing populations who might otherwise be absent from official reporting, including homeschooled and uninsured children. The analysis identifies clusters of undervaccination that aligned closely with recent measles outbreaks, offering actionable insights for targeted immunization strategies and outbreak preparedness.

Results

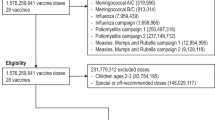

In a nationally representative sample of 22,062 US adults with children under 5 collected via the ONM participatory surveillance platform (fielded between July 2023 and April 2024), the survey-weighted estimate of MMR vaccine uptake (≥1 dose) was 64.0% (95% confidence interval (CI) 63.2–64.9%, representing approximately 71.1% (70.2–72.1%) of the MMR eligible population (children >6 months). As reported previously, uptake differed substantially by parental characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination status16.

County-level vaccine uptake and geographic clustering

We applied a multilevel SAE framework to predict county-level MMR (≥1 dose) coverage across the contiguous USA. The estimates revealed substantial geographic variation in MMR uptake, with distinct patterns of spatial clustering, as shown in Fig. 1. For interpretability, counties were grouped into five risk categories based on predicted coverage: very high risk (<60%), high risk (60–69%), medium risk (70–79%), low risk (80–84%) and lowest risk (≥85%). Higher coverage was observed across the Northeast, Midwest and Northwest and along the Pacific coast. Spatial autocorrelation was strong (global Moran’s I = 0.53, P < 0.0001), indicating statistically significant geographical clustering of counties with similar vaccination rates. Local Moran’s I analysis identified statistically significant clusters of low coverage—hot spots—in West Texas, in southern New Mexico, in parts of Mississippi and across the rural Southeast. By contrast, cold spots—clusters of high coverage—were concentrated in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. Notably, several high-risk hot spot counties were located in states experiencing active measles outbreaks.

County-level estimates of ≥1-dose MMR vaccine coverage among US children under age 5 were generated using a multilevel regression with poststratification (MRP) framework, based on digital surveillance data (ONM) collected between July 2023 and April 2024 (n = 3,109 counties; one modelled estimate per county). a, Modelled vaccine uptake categorized into five risk levels based on estimated vaccination rate: very high risk (<60%), high risk (60–69%), medium risk (70–79%), low risk (80–84%) and lowest risk (≥85%), relative to the herd-immunity threshold for measles. Because these estimates include children under 6 months who are not yet vaccine-eligible, the upper threshold appears lower than the 92–95% benchmark typically cited for herd immunity. b, Results from a spatial clustering analysis using local indicators of spatial association (LISA), which identifies counties with vaccination rates statistically significantly higher or lower than their geographic neighbours (two-sided permutation test, 499 permutations, P < 0.05 after Benjamini–Hochberg correction). LISA cluster labels denote: high–high (counties with high uptake surrounded by high-uptake neighbours), low–low (low uptake surrounded by low-uptake neighbours), high–low (high uptake surrounded by low-uptake neighbours) and low–high (low uptake surrounded by high-uptake neighbours). Statistically significant clusters are highlighted; counties shown in white did not exhibit statistically significant spatial clustering. Figure adapted from TIGER/Line Shapefiles, US Census Bureau (2022).

At the state level, county-aggregated estimate ranges from 61.6% (95% CI 58.9–64.5%) in New Mexico to 79.1% (95% CI 76.5–81.6%) in Massachusetts, with a median of 71.3% (95% CI 69.4–73.4%). County-level estimates showed even greater variation, with a median MMR uptake of 71.4%, ranging from 35.8% (95% CI 35.8–42.0%) to 86.8% (95% CI 85.1–88.4%). Counties with the lowest modelled coverage were primarily in Georgia, Texas and Mississippi, while the highest coverage appeared in parts of New York, Indiana and Oregon (Fig. 2).

The box plot presents SAE-predicted county-level MMR vaccine uptake (≥1 dose) among children under age 5, grouped by the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia (n = 3,109 counties). Each box represents the interquartile range of county-level estimates, with the central line indicating the median. The horizontal lines extend to the minimum and maximum values within a typical range; counties with values far outside this range are plotted individually. The dashed vertical line at 85% denotes the threshold for the lowest measles risk category used in Fig. 1. Because these estimates include all children under 5, including those under 6 months who are not yet vaccine-eligible, the upper threshold appears lower than the 92–95% benchmark typically cited for herd immunity. No formal hypothesis testing was performed; all values represent model-derived county-level estimates from a single fitted model.

Model validation and local discrepancies

Multiple validation analyses supported our model-based coverage estimates. Shown in Table 1, the distribution of model-based estimates closely aligned with that of direct survey data at both the county and state levels. SAE-predicted MMR uptake showed strong agreement with direct survey estimates at both the county level (n = 932; Pearson r = 0.84, Spearman ρ = 0.86, R2 = 0.71; all P < 2.2 × 10⁻¹⁶) and state level (n = 49; Pearson r = 0.88, Spearman ρ = 0.91, R2 = 0.77; P = 7.0 × 10⁻¹⁶), with substantial R2 values in corresponding bivariate regressions. The estimated coverage and spatial clustering analysis are not sensitive to various alternative model specifications or spatial aggregation procedures.

Lastly, we compared state-level model estimates with the CDC’s provider-verified 36-month one-dose MMR coverage data to assess overall coherence. Modelled and CDC estimates clustered closely along the 45° line, with modest differences (5–10 percentage points) and no signs of systematic differences (Fig. 3). However, only two states—Texas and New Mexico—were positioned well above the diagonal line, with model-based estimates substantially lower than the CDC-reported figures (New Mexico: 61.6% versus 90.3%; Texas: 62.9% versus 93.7%). These two states were also the only states experiencing substantial initial measles outbreaks during the study period. To better understand this discrepancy, we examined county-level patterns in Texas (Supplementary Information section 2.3.3) and found that measles cases were more than twice as likely to occur in ‘low–low’ counties (areas with both low estimated vaccination coverage and low-coverage neighbours), suggesting that spatial vulnerability and suboptimal vaccination rates among young children may help to explain the elevated risk of outbreaks.

Points represent the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia (n = 49 states), with values corresponding to state-level SAE-predicted MMR vaccine uptake among children under age 5 (x axis) and CDC-reported 36-month MMR coverage for ≥1 dose (y axis). Point size and colour indicate the number of confirmed measles cases in each state as of 11 April 2025. The dashed diagonal line indicates perfect agreement between model-based estimates and reported coverage. States above the line have higher reported coverage than predicted by the model, while those below the line have lower reported coverage. Statistical comparisons were descriptive; no formal hypothesis testing was applied.

AI super-resolution

Although public health surveillance typically aggregates data at the county level, measles outbreaks in the USA often emerge from tight-knit local communities. To extend our findings to a finer geographic scale, we leveraged Google’s Population Dynamic Foundational Model (PDFM)21 to produce MMR vaccination estimates at the ZIP Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA) level (see details in Supplementary Information section 2.4). PDFM is a multimodal AI system trained on privacy-preserving data sources (for example, search trends, map interactions, mobility and environmental signals) that captures neighbourhood-level context beyond standard census variables. Our subcounty estimates revealed similar regional patterns to the county-level model but identified more compact clusters of vaccine behaviour (Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2). The distribution of Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) categories shifted slightly, preserving most low–low clusters in Texas, New Mexico and the southern and southeastern USA, as well as high–high clusters in parts of the Midwest, while diluting other mixed patterns.

Discussion

Our study provides the nationwide county-level MMR vaccine coverage among US children under age 5, leveraging a digital surveillance tool and advanced spatial modelling methods. These granular estimates reveal substantial gaps in coverage, highlighting the critical role of local variation in vaccine-induced immunity in shaping measles vulnerability. Importantly, by drawing on a digital participatory surveillance platform rather than administrative records, our approach captures children who are often absent from official reporting systems, including those who are homeschooled, uninsured or otherwise outside traditional healthcare and school-based surveillance. Despite long-standing national recommendations for routine childhood vaccination, our findings show that MMR uptake remains low in many counties—particularly those with disadvantaged socioeconomic profiles—highlighting overlooked vulnerabilities within this at-risk population.

Notably, our model identified substantial clusters of undervaccination in locations across the US South and Southwest, including areas currently experiencing active measles outbreaks. These areas show sizable discrepancies between our model-based coverage estimates and official state-level data9, which probably reflect both age-composition differences (children under 5 years versus 36 months) and the exclusion of select populations in traditional surveillance methods (parent-reported coverage versus provider-verified records)4,22. For example, Texas and New Mexico fall well below the national average in our county-level estimates, despite high reported state-level coverage at kindergarten entry. Both states subsequently reported early measles activity in early 2025, consistent with our model’s identification of lower effective coverage and suggesting that official figures (at kindergarten entry) might have not fully represented the community-level MMR vaccine uptake at that time. Recent analyses of electronic health records from Truveta23 similarly document pandemic-related declines in MMR vaccination, although their data, derived solely from children with consistent healthcare access, suggested somewhat higher coverage among children engaged in routine care. These findings suggest that some children may be delaying rather than forgoing vaccination. Together, these differences underscore the critical need for surveillance systems capable of capturing delayed vaccinations and more comprehensively monitoring younger, harder-to-reach children.

Our spatial clustering analyses further identified considerable concentrations of low MMR vaccine uptake, counties with persistently low coverage surrounded by similarly undervaccinated areas, in regions such as West Texas, southern New Mexico, Mississippi and the rural Southeast. These clusters signal areas vulnerable to future outbreaks, even in the absence of current transmission. Given this elevated risk, public health officials may wish to revisit vaccination guidance for children aged 6–12 months9 residing in these regions24. Although counties vary substantially in size and population density, they remain a central unit for public health planning and monitoring. Here, we were able to leverage an AI foundation model to produce MMR vaccination estimates at the ZCTA level. The finer-scale modelling revealed more compact local clusters and subtle shifts in LISA category distributions, reflecting both improved precision from AI-enhanced local contextual factors and the inherent sensitivity of LISA statistics to spatial aggregation. However, the overall consistency of results across scales (county versus ZCTA; Supplementary Information section 2.4) suggests that county-level clustering captures broader underlying patterns of vaccine behaviour, while ZCTA-level maps provide complementary insight into smaller, community-based clusters that may be more relevant for localized behavioural dynamics. These maps do not define transmission boundaries but serve as practical tools to inform resource allocation and identify vulnerable regions. More systematic and inclusive data collection efforts at subcounty levels would greatly strengthen the ability to monitor undervaccination and design targeted interventions.

Beyond identifying spatial patterns of vaccination, an important contribution of this study lies in combining digital participatory surveillance with advanced statistical methods to improve the measurement of vaccination coverage, particularly among vulnerable populations. This methodology offers a timely and scalable complement to conventional immunization monitoring systems, such as vaccine registries and national surveys, by enhancing the detection of localized immunity gaps and increasing geographic granularity and inclusiveness to reach populations often missed by the existing systems. While digital surveillance data cannot replace traditional monitoring approaches, they can significantly improve timeliness, geographic resolution and representativeness via leveraging digital technology to enhance convenience, anonymity and outreach, features that are increasingly vital as social and economic interdependence accelerates and infectious-disease risks transcend local and national boundaries25,26.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, parent-reported MMR uptake may be subject to recall bias; however, our estimates align closely with direct survey results, correlate strongly with official benchmarks and are consistent with findings from independent studies. Second, survey response volume was low in some counties; however, our modelling strategy addresses spatial sparsity through aggregation and hierarchical smoothing, with resulting uncertainty reflected in the CIs and robustness of results demonstrated in multiple analyses. Third, our estimates are based on ≥1-dose coverage and do not reflect full completion of the two-dose MMR schedule as usually reported in other data sources. Moreover, because our study population includes children under age 5, many had not yet reached the age of routine MMR eligibility (12 months generally; but 6 months for exceptions such as travel). As such, our coverage estimates are expectedly lower than administrative data, in part because we are capturing the age group least likely to be fully vaccinated. These differences demonstrate how digital participatory surveillance and traditional monitoring approaches capture complementary populations and timeframes, and together could form a more robust, integrated monitoring system adapted to evolving population and disease dynamics. They also reinforce the urgency of adapting surveillance and outreach efforts to better include high-risk, undermonitored populations.

In summary, our work provides an innovative resource for improving immunization strategies and mitigating measles outbreaks through geographically targeted interventions. We developed an interactive website (https://healthmap.org/measles/) that enables users to explore county-level MMR vaccination estimates across the USA. Model-based surveillance can complement traditional systems by identifying at-risk communities earlier, guiding geographically targeted interventions and strengthening local preparedness, ultimately advancing national vaccine equity and disease prevention goals.

Methods

In a retrospective cohort study, we leveraged ONM, a previously validated digital health surveillance platform that collects anonymous, self-reported health information from a national sample of US adults. In brief, ONM utilized non-probability river sampling techniques to randomly deliver a survey to individuals in SurveyMonkey’s diverse, multi-million-person user pool. From July 2023 to April 2024, participants provided demographics, residential ZIP code and information on children under 5, including parental report of MMR vaccine status (≥1 dose versus none). For households with multiple eligible children, one child was randomly selected at the time of survey completion to avoid intrahousehold clustering. We constructed a nationally representative analytic sample of 22,062 parents with children under 5 using a weighting procedure calibrated to US Census benchmarks (including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education and geography). This study is a quantitative analysis only. Additional methodological details on the ONM platform and survey design have been published previously16 and validated for various public health applications17,27.

SAE with poststratification

To generate county-level MMR vaccine uptake (≥1 dose), we implemented a spatial multilevel logistic regression with poststratification (MRP) framework18,19. The regression model included both individual- and county-level variables, with random intercepts for county-like areas and states to account for unobserved contextual variation in vaccination decisions. To address sparsity in counties with limited direct survey data, we implemented an iterative spatial aggregation algorithm that merged counties into larger county-like areas until each area contained a minimum of five valid observations. The distribution of direct survey responses and sensitivity analyses of the aggregation procedure are shown in the Supplementary Information section 2.2.

The outcome was parent-reported receipt of at least one dose of the MMR vaccine among children under 5. Individual-level controls included parent age group (18–29, 30–39, 40–49 and 50-59), gender (male or female) and race/ethnicity (Asian, Black, Hispanic, white or other). County-level covariates were selected on the basis of prior literature28 and LASSO regression, and included: median household income, percentage of white residents, percentage of single-parent households, percentage enrolled in Medicaid from the American Community Survey (5-year estimates 2019–2023)29, percentage of adults completing the primary COVID-19 vaccine series30, and Democratic vote share in the 2020 US presidential election31.

Model predictions were then poststratified using US Census microdata32 to produce population-weighted county-level estimates of ≥1-dose MMR coverage among children under 5. The fitted model was applied to all combinations of demographic strata (age group × race/ethnicity × gender) within each county. Poststratification ensured that estimates were aligned with the demographic and geographic distribution of the US population, thereby generating population-representative county-level estimates, including for counties without direct survey responses. To calculate the 95% CIs, we used Monte Carlo simulation to generate 1,000 replicates of MMR uptake estimates for each county, state and demographic subgroup. State-level estimates were computed as population-weighted averages of county-level estimates based on US Census counts.

Benchmarking against traditional surveillance and outbreak data

To further evaluate alignment with established data sources, we compared our state-level estimates with CDC-published one-dose MMR coverage at 36 months33. In parallel, we incorporated publicly reported measles case counts as of April 2025, corresponding to the initial phase of the current outbreak, to assess whether states with lower predicted coverage and larger gaps relative to official statistics overlapped with regions experiencing elevated outbreak activity. This benchmarking step enabled us to assess concordance between small area estimates and existing surveillance systems while examining the potential added value of our approach for identifying areas of public health concern.

Spatial clustering analysis and visualization

Given the central role of social and geographic clustering in measles transmission, we conducted spatial clustering analysis using LISA to detect statistically significant patterns of MMR uptake across counties. Although counties vary substantially in size and population density, this scale remains the most relevant administrative unit for many public health agencies. We used LISA to examine whether modelled undervaccination was geographically isolated or clustered across contiguous counties, providing descriptive insight into potential pockets of outbreak risk. This method identifies geographic clusters—such as counties with high or low uptake surrounded by neighbours with similar values—potentially indicative of localized outbreak risk. To support public health interpretation, we categorized counties into five risk groups based on predicted MMR vaccine coverage thresholds, informed by the herd immunity threshold for measles (typically estimated at 92–95%). Counties with estimated uptake below 60% were classified as very high risk, followed by high risk (60–69%), medium risk (70–79%), low risk (80–84%) and lowest risk (≥85%). These thresholds reflect increasing proximity to the herd immunity benchmark and help prioritize areas for intervention. While the highest group cut-off (≥85%) may appear low relative to the 92–95% herd immunity benchmark, this reflects the inclusion of infants under 6 months who are not yet eligible for MMR vaccination in the denominator of our estimates. Map boundaries are based on 2022 US Census Bureau TIGER/Line shapefiles, accessed via the R package tigris (version 2.1).

AI-based super-resolution with PDFM embeddings

Building on the county-level analysis, we extended our framework to the ZCTA scale to examine patterns of undervaccination across local communities, where measles transmission is shaped by social interactions and health behaviour. This extension was enabled by embeddings from PDFM21, an AI system pretrained on large-scale, multimodal data sources—including Google search and map activity, trends of mobility and busyness, geospatial data and environmental conditions—that capture fine-grained neighbourhood context while preserving privacy (Supplementary Information section 2.4). By incorporating these high-dimensional embeddings into our SAE framework, we applied an AI-based super-resolution approach to assess the consistency between county- and ZCTA-level estimates and to demonstrate how subcounty resolution can support more targeted public health strategies.

To further assess the robustness of our results, model performance was evaluated by comparing model-based estimates with direct survey estimates at both the county and state levels. In addition, we conducted extensive analyses evaluating model fit, the sensitivity of results to alternative specifications and the stability of estimates across subgroups. We also validated predictions using independent external data sources and additional statistical tests. These steps were designed to show that our conclusions are not dependent on any single alternative analytical choice. Full methodological details and supplementary results are provided in the Supplementary Information. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.4.3 (RStudio). The study adheres to the STROBE reporting guideline, was approved by the institutional review board (IRB-P00023700) and received a waiver of informed consent. Use of the data in this study complied fully with the terms of use of the SurveyMonkey platform and associated data-use agreements.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

For privacy, individual-level survey data cannot be made publicly available. Researchers affiliated with academic or public health institutions may request access to these data for non-commercial research purposes. Requests should be submitted to the corresponding author. Requests will typically be processed within 4–6 weeks. All derived data products from this study, including county- and ZCTA-level predicted MMR vaccination coverage, will be deposited in a public data repository and are also accessible through the interactive dashboard at https://healthmap.org/measles/

Code availability

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.2). The code used to generate the estimates and figures is publicly available at Github (https://github.com/eric-gengzhou/MMR_vaccine_estimates)34.

References

Measles cases and outbreaks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/index.html (2025).

Grills, L. A. & Wagner, A. L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parental vaccine hesitancy: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccine 41, 6127–6133 (2023).

Desilva, M. B. et al. COVID-19 and completion of select routine childhood vaccinations. Pediatrics https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2024-068244(2025).

Seither, R. et al. Coverage with selected vaccines and exemption rates among children in kindergarten-United States, 2023–24 school year. Morb. Mort. Wkly Rep. 73, 925–932 (2024).

Seither, R. et al. Coverage with selected vaccines and exemption from school vaccine requirements among children in kindergarten-United States, 2022–23 school year. Morb. Mort. Wkly Rep. 72, 1217–1224 (2023).

Truelove, S. A. et al. Characterizing the impact of spatial clustering of susceptibility for measles elimination. Vaccine 37, 732–741 (2019).

Alvarez-Zuzek, L. G., Zipfel, C. M. & Bansal, S. Spatial clustering in vaccination hesitancy: the role of social influence and social selection. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1010437 (2022).

Gromis, A. & Liu, K.-Y. Spatial clustering of vaccine exemptions on the risk of a measles outbreak. Pediatrics 149, e2021050971 (2022).

Measles vaccination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/measles/vaccines/index.html (2025).

Hill, H. A., Yankey, D., Elam-Evans, L. D., Chen, M. & Singleton, J. A. Vaccination coverage by age 24 months among children born in 2019 and 2020-National Immunization Survey-Child, United States, 2020–2022. Morb. Mort. Wkly Rep. 72, 1190–1196 (2023).

Cordner, A. The health care access and utilization of homeschooled children in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 269–273 (2012).

Ghildayal, N. et al. Public health surveillance in electronic health records: lessons from PCORnet. Prevent. Chron. Dis. 21, E51 (2024).

Mohanty, S. et al. Homeschooling parents in California: attitudes, beliefs and behaviors associated with child’s vaccination status. Vaccine 38, 1899–1905 (2020).

Masters, N. B. et al. Fine-scale spatial clustering of measles nonvaccination that increases outbreak potential is obscured by aggregated reporting data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 28506–28514 (2020).

Vaccination Coverage Levels in Texas Schools — Kindergarten (Texas Department of State Health Services, 2025); https://www.dshs.texas.gov/immunizations/data/school/coverage (2025).

Zhou, E. G. et al. Parental factors associated with measles–mumps–rubella vaccination in US children younger than 5 years. Am. J. Public Health 115, 369–373 (2025).

Rader, B. et al. Use of at-home COVID-19 tests—United States, August 23, 2021–March 12, 2022. Morb. Mort. Wkly Rep. 71, 489 (2022).

Mills, C. W., Johnson, G., Huang, T. T., Balk, D. & Wyka, K. Use of small-area estimates to describe county-level geographic variation in prevalence of extreme obesity among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e204289 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Multilevel regression and poststratification for small-area estimation of population health outcomes: a case study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence using the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Am. J. Epidemiol. 179, 1025–1033 (2014).

Dong, E., Saiyed, S., Nearchou, A., Okura, Y. & Gardner, L. M. Trends in county-level MMR vaccination coverage in children in the United States. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.8952 (2025).

Agarwal, M. et al. General geospatial inference with a population dynamics foundation model. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.07207 (2024).

Seeskin, Z. H. et al. Estimating county-level vaccination coverage using Small Area Estimation with the National Immunization Survey-Child. Vaccine 42, 418–425 (2024).

Latest US First-Time Measles Vaccination Trends for Children under 24 Months, (Truveta, 2025); https://www.truveta.com/blog/research/research-insights/first-time-measles-vaccination-trends-us-children-under-24-months/

Rader, B., Walensky, R. P., Rogers, W. S. & Brownstein, J. S. Revising US MMR vaccine recommendations amid changing domestic risks. JAMA 333, 1201–1202 (2025).

Khabbaz, R. F., Moseley, R. R., Steiner, R. J., Levitt, A. M. & Bell, B. P. Challenges of infectious diseases in the USA. Lancet 384, 53–63 (2014).

Baker, R. E. et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 193–205 (2022).

Rader, B. et al. Mask-wearing and control of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the USA: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e148–e157 (2021).

Kempe, A. et al. Parental hesitancy about routine childhood and influenza vaccinations: a national survey. Pediatrics 146, e20193852 (2020).

American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, 2019–2023 (US Census Bureau, 2023); https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html

COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States (County) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023); https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccinations-in-the-United-States-County/8xkx-amqh/about_data

Baltz, S. et al. American election results at the precinct level. Sci. Data 9, 651 (2022).

Schroeder, J. V. R. et al. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 20.0 (IPUMS, 2025).

Vaccination Coverage Among Children Age 35 Months (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2023); https://www.kff.org/other-health/state-indicator/percent-of-children-aged-0-35-months-who-are-immunized/

Zhou, E. G. MMR vaccine estimates. Github https://github.com/eric-gengzhou/MMR_vaccine_estimates (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Gertz, B. R. Anderson and C. Remmel for their support and assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.G.Z. performed the statistical analyses. E.G.Z., J.S.B. and B.R. acquired, analysed and interpreted the data. E.G.Z. and B.R. drafted the article; they had full access to the study data and take responsibility for the data integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. J.S.B. and B.R. supervised the study. All authors conceptualized and designed the study and critically revised the article for important intellectual content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.R. reports research funding from the Thrasher Research Fund (Boston Children’s Hospital grant FP00000397). E.G.Z. receives salary support from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL150044) outside the submitted work. All authors declare no other competing interests related to this study.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Health thanks Jon Zelner and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Lorenzo Righetto, in collaboration with the Nature Health team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 ZIP Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA)–Level Estimates of MMR Vaccine Uptake Among U.S. Children Under Age 5.

Note: ZCTA-level estimates of ≥1-dose measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccine coverage among U.S. children under age 5 were generated using the same multilevel regression with post-stratification (MRP) framework as in the county-level analysis, extended with contextual embeddings from Google’s Population Dynamics Foundation Model (PDFM). Embedding components derived from principal component analysis were included as auxiliary covariates. Modeled vaccine uptake is categorized into five risk levels—Very High Risk (<60%), High Risk (60–69%), Medium Risk (70–79%), Low Risk (80–84%), and Lowest Risk (≥85%)—relative to the herd-immunity threshold for measles. Because estimates include children under 6 months who are not yet vaccine-eligible, the upper threshold appears lower than the 92–95% benchmark typically cited for herd immunity. (n = 29,971 ZCTAs; one modeled estimate per ZCTA.). Figure adapted from TIGER/Line Shapefiles, US Census Bureau (2022).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial Clustering of Predicted MMR Vaccine Uptake at the ZCTA Level.

Note: Results from a Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analysis applied to modeled MMR vaccination rates at the ZCTA level (n = 29,971). LISA identifies ZCTAs with statistically significantly higher or lower uptake than their geographic neighbors using queen contiguity weights (two-sided permutation test, 499 permutations, p < 0.05 after Benjamini–Hochberg correction). Cluster categories include High–High (ZCTAs with high uptake surrounded by high-uptake neighbors), Low–Low (low uptake surrounded by low-uptake neighbors), High–Low, and Low–High. Statistically significant clusters are highlighted; areas shown in white did not exhibit statistically significant spatial clustering. Patterns largely mirror those at the county level, though with finer spatial resolution and more localized cluster boundaries. Figure adapted from TIGER/Line Shapefiles, US Census Bureau (2022).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods (sections 1–1.2), Results (sections 2–2.5), Tables 1–10 and Figs. 1–14.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, E.G., Brownstein, J.S. & Rader, B. Assessing MMR vaccination coverage gaps in US children with digital participatory surveillance. Nat. Health 1, 138–144 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44360-025-00031-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44360-025-00031-8