Abstract

Cortisol is a key regulator of stress and circadian physiology, yet current monitoring relies on invasive blood sampling or saliva assays that are prone to contamination and provide limited temporal resolution. Wearable sweat cortisol sensors are promising, but require electronic sensing systems and have limited capability for long-term, time-sequenced monitoring. Here we present a wearable paper-based microfluidic platform that integrates plasmonic-gold-nanoflower-based colorimetric assays to enable non-invasive tracking of cortisol in eccrine sweat. Sweat is induced by carbachol iontophoresis and directed through collection channels using either electronically timed sequential activation or paper-based delay valves with self-powered electrochromic indicators. In human studies, the system resolved circadian variations, acute stress responses to cold pressor challenges, and jet-lag-associated disruptions, with the results closely matching those from saliva and serum assays. This wearable lateral flow technology establishes sweat as a viable medium for real-time hormone monitoring and may enable personalized management of stress, sleep and circadian misalignment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Managing stress is a critically important aspect of maintaining good physical and mental health1. Cortisol, a key biomarker for stress, is a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal glands2. Activation of the stress-responsive hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis induces the release of cortisol into the bloodstream. The resulting complex metabolic processes lead to elevated blood pressure and glucose levels, as mechanisms to respond to stressful scenarios3. Chronic exposure to elevated concentrations of cortisol can have detrimental effects on the cardiovascular, immune, renal and endocrine systems1. Misalignment of circadian rhythms, also controlled by cortisol, can likewise lead to adverse health effects4,5. Knowledge of cortisol levels can, therefore, potentially assist in the management of sleep patterns and stress-related disorders, including those related to post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome6.

Despite the importance of cortisol, monitoring its concentration in biofluids remains challenging. The collection and analysis of blood samples involves complex procedures, trained personnel and dedicated facilities6. Saliva is an attractive alternative to blood, but one that is prone to contamination by substances in the mouth7. Eccrine sweat is therefore of increasing interest3,6,8,9,10,11. Wearable devices for electrochemical sensing of cortisol in sweat12,13,14 offer important capabilities but require electronics for sensing and offer limited capacity for the time-dynamic detection of cortisol over hours. Conventional colorimetric sensors have some potential, but face challenges due to the extremely low concentrations of cortisol present in sweat3.

Lateral flow immunoassays that use colorimetric readout have proven utility in sensing biomarkers in blood serum, urine, nasal swabs and saliva. For measuring cortisol, such assays operate based on competitive binding between cortisol and a conjugate of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and cortisol (BSA–CTS), both of which bind anti-cortisol antibodies on plasmonic nanoparticles. The sensitivity depends on various physical, chemical and biological factors, including label type, bioreceptor affinity and flow rate15. Among these, the optical label is critically important. Relative to commonly used gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), gold nanoflowers (AuNFs) are particularly attractive for this purpose, due to their high surface areas and enhanced extinction coefficients associated with localized surface plasmon resonances16,17,18. Their complex surface structure also improves antibody immobilization efficiency18. Previous studies have demonstrated these enhancements in lateral flow assays (LFAs), but their application in detecting cortisol remains unexplored.

This Article reports a skin-interfaced device that combines paper-based microfluidic structures and LFAs that use AuNFs for the sampling and analysis of sweat in a time-sequential fashion following iontophoretic delivery of carbachol through the surface of the skin. The results include versions of the device with two different sampling modes: (1) a pre-programmed electronic timer circuit for sequenced iontophoresis events; and (2) a passive valve structure and self-powered electrochromic timer with which to capture distinct sampling events. Demonstrations of this technology involve studies on the diurnal cycle, cold pressor tests (CPTs) and responses to jet lag. Levels of cortisol in sweat measured in this fashion align well with separate assays based on saliva and serum. The results suggest the potential for routine biochemical assessments of stress and mental health, to guide therapeutic intervention.

Results

Wearable LFAs for long-term, time-dynamic monitoring of cortisol in stimulated sweat

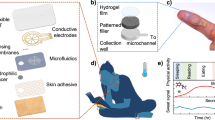

The platform comprises four major components: an encapsulation layer that caps the entire system; an integrated iontophoresis module with an electronic timer for time-triggered sweat stimulation; a set of agarose hydrogels containing carbachol (blue; carbagel) or KCl (yellow); and a skin-interfaced LFA module with four separate assays (Fig. 1a). A three-dimensional (3D) schematic illustration shows the assembly of these components in the device (Fig. 1b). The carbagel elements interface with the skin at a position next to the paper-based microfluidic cellulose collection channels. Iontophoretic delivery triggers the release of sweat, which then passes to the LFA (Fig. 1c). These multiple LFA assays support time-resolved measurements across multiple collection channels. Each channel has a separate sample pad to transfer sweat towards a conjugation pad, which contains AuNFs that are conjugated with an anti-cortisol antibody (AuNF–Ab conjugates) (Fig. 1d). Then, the sweat moves through the nitrocellulose membrane, which is spotted with BSA–CTS for the test line and anti-immunoglobulin G (anti-IgG) antibody for the control line. An absorbent pad at the end of the nitrocellulose membrane absorbs any excess sweat. An exploded view of the LFA (Fig. 1e) highlights each component, from the bottom skin adhesive to the top viewing window. The assay includes a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate with an adhesive layer, microfluidic spacers, nitrocellulose membranes, conjugation pads, sample pads, absorbent pads and viewing windows made of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic materials. Optical images show the device on the skin with hydrogel (Fig. 1f) and electronics (Fig. 1g). Figure 1h presents an image of an LFA on the body, displaying the test and control lines. Figure 1i illustrates the principles and operation for time-sequenced iontophoretic stimulation at 20-min intervals, with sweat flow visualized by green food dyes spotted on the conjugation pad.

a, Exploded schematic of the device, comprising an encapsulation cover, an iontophoretic stimulation module, hydrogels containing carbachol (blue) and KCl (yellow), and the skin-interfaced LFA. b, 3D representation of the device with an iontophoretic stimulation module and encapsulation layer. c, Magnified schematic of simultaneous sweat stimulation, collection onto cellulose paper and transport to an LFA strip via a sample pad. d, Detailed schematic of the LFA on a PET substrate. e, Exploded schematic of the LFA with a superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic viewing window, a sample pad, a conjugation pad, absorbent pads, nitrocellulose membranes and a PET substrate with skin adhesive. f, Photograph of an LFA with patterned hydrogels placed on the skin for iontophoretic stimulation. g, Photograph of the wearable LFA with the iontophoretic stimulation module and an encapsulation layer. h, Photograph of the device in operation for sensing cortisol concentrations in sweat. i, A series of optical images demonstrating a time-sequenced series of iontophoretic stimulation events. NC, nitrocellulose.

Synthesis, mechanism and characterization of the LFA

Figure 2a summarizes the principles of the competitive LFA for detecting the concentration of cortisol in sweat. The sample pad contains a phosphate buffer (1 M; 2 μl) that adjusts the pH of entering sweat to 6.5. Upon wetting the conjugation pad, cortisol in the sweat binds to the antibody on the AuNFs and moves along the nitrocellulose membrane, where the test line contains BSA–CTS and the control line contains anti-IgG antibody. At physiologically relevant sweat rates (0.5–1.0 μl min−1), the transit time of ~6–12 min provides sufficient incubation for cortisol to fully bind to the antibody3. As described elsewhere, the nanoflower geometry enhances the sensitivity of the assay due to the enhanced light extinction coefficient, large surface area and reduced velocity associated with flow through the nitrocellulose membrane compared with spherical geometries18,19. This scheme offers limits of detection that span into picomolar concentrations, consistent with physiological concentrations of cortisol in sweat.

a, Schematic of the LFA for sensing sweat cortisol based on the use of AuNFs and competitive mechanisms. b, Absorbance spectrum of AuNFs. c, A transmission electron microscope image of a typical AuNF. d, Size distributions of AuNFs measured by dynamic light scattering. e–g, Standard calibration curves of the LFA with artificial sweat using the test line (e), control line (f) and control/test ratio (g). n = 3. h, Effect of flow rate on the control/test line ratios for cortisol concentrations of 0 and 100 ng ml−1. n = 3. i, Performance of LFA calibration curves for estimating the cortisol concentration in real sweat of various baseline cortisol concentrations versus artificial sweat. Sweat samples were drop-cast onto the LFA assays. n = 3. j, LFA versus ELISA for estimating the concentration of cortisol in real sweat. n = 3. k, Stability of the LFA signal with time at cortisol concentrations of 0 and 100 ng ml−1. n = 3 before optimization of the AuNF volume. The data represent mean values ± s.d. (n = 3 technical replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 1a highlights the synthesis of AuNFs via the reaction of para-aminobenzenethiol with Au3+ ions. Upon reduction of gold ions by thiolate complex formation, the clear solution turns reddish brown, indicating the formation of AuNFs. Figure 2b shows the ultraviolet absorbance spectrum of AuNFs, with a maximum peak at 558 nm, resulting from their larger size compared with typical AuNPs. Figure 2c presents a transmission electron microscopy image of a typical AuNF, with an average size of 164 nm, as determined from dynamic light scattering (Fig. 2d). A concentration-dependent increase in the zeta potential (the electrical potential at the particle’s surface) follows from an increase in the anti-cortisol antibody concentration, demonstrating successful binding of the antibody to the surface of AuNFs (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

In this competitive LFA assay, AuNF–Ab conjugates bind to the immobilized BSA–CTS antigen at the test line in the absence of cortisol in sweat, forming a distinct and intense band (Extended Data Fig. 1c). The residual AuNF–Ab conjugates, both with and without cortisol, subsequently interact via their fragment crystallizable regions with the anti-mouse IgG antibody at the control line. Increasing the cortisol concentration (0–100 ng ml−1) results in a progressive fading of the test line colour due to the partial or full occupation of anti-cortisol antibody with sweat cortisol and competition with BSA–CTS at the test line, which disappears entirely at approximately 1,000 ng ml−1 (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 1c–g). Similarly, the control line becomes more pronounced with increasing cortisol concentration (Fig. 2f). Thus, the LFA demonstrates high-contrast bright bands at both the test and control lines, particularly at low and high cortisol concentrations. As such, the control-to-test-line ratios provide sensitive quantification of cortisol concentrations. The optimization of adjusted sweat pH levels (Extended Data Fig. 1h,i), working buffers (Extended Data Fig. 1j,k), BSA–CTS (Extended Data Fig. 1l,m) and anti-cortisol antibody (Extended Data Figs. 1m and 2a) yields a highly sensitive assay, as demonstrated by the standard calibration curve for artificial sweat solution spiked with cortisol concentrations ranging from 100 pg ml−1 to 100 ng ml−1 at a flow rate of 0.5 μl min−1 (Fig. 2g). Application of the signal-to-noise method20 determined the limit of detection for cortisol to be 75 pg ml−1, supporting the sensitivity of the assay into the low-picomolar range. The calibration curve covers the physiologically relevant concentrations of cortisol in sweat, which extends to 100 ng ml−1.

A series of experiments validates the operation of the system. The results indicate negligible sensitivity to sweat flow rate and injection volume, over relevant ranges, after optimization (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 2b,c). The standard calibration curves obtained for three different real sweat samples with baseline cortisol concentrations of 1.0, 0.9 and 0.3 ng ml−1, as well as artificial sweat samples, all of which are spiked with cortisol, are consistent (Pearson’s correlation coefficient, r = 0.99; Fig. 2i). Furthermore, cortisol concentrations obtained from the LFA assay correlate with those measured using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) kit (r = 0.94; Fig. 2j). Quantitative readouts of test line intensity under varying illumination conditions (4,500–5,500 K) and using various imaging devices (digital and smartphone cameras) show negligible signal variation, supporting the robustness of the assay (Extended Data Fig. 2d–f). Protocols for analysing the LFA signals appear in Extended Data Fig. 3a–g and the Supplementary Information section ‘Analysis of wearable LFA’. The LFA signals remain consistent for up to 6 h after assay completion, which is critical for time-sequenced iontophoretic sweat sampling and detection over several hours (Fig. 2k).

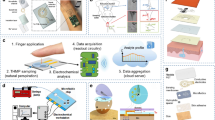

Mechanisms and characterization results for time-sequenced iontophoretic stimulation of sweat production

Optical images of the time-sequenced iontophoresis module appear in Extended Data Fig. 4a–c. Figure 3a and Extended Data Fig. 4d–f show a block diagram and connection scheme. First, activating the long-term timer (TPL5110) with a switch generates a pulse signal that triggers the short-term timer (TLC551). The short-term timer, pre-configured in one-shot mode, then activates one of the step-up converters (R1218) from the four channels (initially set to 00) through a 2-to-4 decoder (SN74LVC1G139) connected to a 2-bit counter (74HC73). During this activation, direct electrical current flows from positive (+) to negative (−) bottom electrodes, thereby delivering carbachol locally through the skin to trigger sweat production. Here, the limiting converter resistor determines the magnitude of the electrical current, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 4e. After a set duration (for example, 5 min), the short-term timer turns off and shifts the counter by one position. The counter sequence follows the order: 00 → 01 → 10 → 11 → 00. A timing diagram in Fig. 3b also confirms the time-sequenced series of iontophoretic sweat stimulation. This stimulation sequence repeats according to the preset timing parameters. In the photographs (on the right-hand side of the graph), the centre LED and red LED on each channel represent activation of the short-term timer and current counter sequence, respectively. Extended Data Fig. 4g,h presents the results for stimulation time interval (tinterval) versus long timer resistance (RL) and stimulation time (ton) versus short timer resistance (Rs), respectively. Extended Data Fig. 4i demonstrates a low level of timing variability.

a, Electrical circuit block diagram and connection mechanisms for the time-sequenced iontophoretic stimulation module. b, Timing diagram showing output voltages for each iontophoretic channel in response to the voltage-triggering signals for long- and short-term timers. c,d, 3D schematics of the electronic components on the top (c) and bottom (d) of the module. e, Effect of the separation distance between the stimulation area and collection channel on the volume of sweat for participants 1 and 2 and FEA simulation. n = 3. f, Effect of the separation distance between the stimulation area and collection channel on sweat rate for participants 1 and 2. n = 3. Dashed line corresponds to FEA simulation. g, Electrical field simulation for operation of the module (first stimulation bay) at a current of 130 μA, demonstrating the effectiveness of the separation. h, Demonstration of the time-sequenced series of iontophoresis (IP) events for 4 collection channels with 6-mm spacing (first iontophoresis event). i, Electric field simulation for the iontophoretic module (second iontophoresis event). The colorimetric bar has a logarithmic scale. j, Demonstration of the second iontophoresis event. k, Electric field simulation for the third iontophoresis event. l, Demonstration of the third iontophoresis event. The data reveal no evidence of cross-contamination at different time points. The data represent mean values ± s.d. (n = 3 technical replicates). Ch, channel.

Figure 3c,d shows a schematic of the flexible printed circuit board with electronic components on the top and bottom of the iontophoretic stimulation module. The main timer modules reside at the centre of the device, with each channel next to the main timer modules in a counter-clockwise order. The remaining components, including a switch, a battery and wireless charging circuits, are located on separate flexible printed circuit board islands, which fold onto the main timer modules during packaging.

Experiments and finite element analysis (FEA) simulations that include the properties of the hydrogel (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b), the current densities (Extended Data Fig. 5c–k) and the distances between the stimulation site and collection channel (Fig. 3e,f) serve as guides to maximize the sweat rate that follows from iontophoretic delivery. Carbagel produces about 20 μl sweat, compared with 5 μl for the alternative pilogel (pilocarpine in hydrogel), at 0.5% wt/vol, 4.3 μA mm−2 and a 1.5-mm distance between the stimulation site and collection channel (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Carbagel is better suited for the application presented here than pilogel, as the miniaturized LFA requires more than 10 μl sweat for operation. The total amount of sweat can be controlled with the limiting converter resistor. For values from 500–200 Ω, the current through the skin ranges from 100–500 μA (Extended Data Fig. 5c), with a corresponding increase in sweat volume (Extended Data Fig. 5d–h). Extended Data Fig. 5i–k illustrates FEA results for the effect of current density on electric field distribution through the skin. The LFA can be filled within 30 min of stimulation for the case of a paper-based microfluidic collection channel with dimensions of 2 mm × 10 mm (Extended Data Fig. 5l,m).

The distance between the stimulation site and collection channel is a critical parameter for maximizing the collected sweat volume and minimizing cross-contamination between each collection channel (Fig. 3e,f). At distances greater than 5.5 mm from the stimulation site, little sweat emerges from the collection channel, thereby defining a minimum distance to avoid cross-contamination. At a distance of 1.5 mm, sweat volumes of over 20 μl can be produced while forming a tight seal with the skin. A series of FEA simulations and on-body stimulation experiments confirm capabilities in time-sequenced iontophoretic stimulation with zero cross-contamination (Fig. 3g–l).

Efficient optical access through the use of superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic materials

Water vapour that emerges from the nitrocellulose membrane tends to condense on the surface of the viewing window, thereby frustrating the ability to visualize the LFA (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). Superhydrophilic surfaces prevent droplet condensation by causing water to spread evenly as a thin film21,22. However, the exclusive use of superhydrophilic materials leads to wicking of sweat away from the nitrocellulose membrane (Fig. 4b). The placement of superhydrophobic material on top of the sample and conjugation pad resolves this issue by blocking sweat flow through the top window (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 6c–j). Figure 4d demonstrates the effectiveness of a superhydrophilic window (contact angle: 9.4°) in preventing droplet formation compared with superhydrophobic (contact angle: 151°) or untreated PET (contact angle: 82°) windows. The configuration with both superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic materials enables reliable operation and clear visualization after 15 min (Fig. 4e) and 4 h (Fig. 4f) of continuous heating on a hotplate at 30°. Characterization of the contact angle (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b), atomic force microscopy (Extended Data Fig. 7c,d), optical properties (Fig. 4g–i) and reactive-ion etching process parameters (Extended Data Fig. 7e) of these materials provided additional insights, as discussed in the Supplementary Information section ‘Characterization of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic surfaces’.

a, Cross-sectional view of the LFA showing the mechanism of sweat vapour condensation on the surface of a superhydrophobic or hydrophobic viewing window. b, Cross-sectional view of the LFA showing a failure mechanism due to sweat flow through a viewing window entirely comprising a superhydrophilic window. c, Cross-sectional view of the LFA assembly with a combination of superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic materials comprising the viewing window. The result prevents vapour condensation above the test line and below the control line and blocks sweat flow through the window. d, Optical image of a skin-interfaced device that uses iontophoretic stimulation of sweat to illustrate the effect of various material types on vapour condensation. e,f, Photograph of an LFA device that uses a superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic viewing window at 15 min (e) and 4 h (f). g, Transmittance change as a function of time for normal PET, superhydrophilic PET and a superhydrophobic viewing window (PET + PSA) at 30 °C in the presence of water. The data represent mean values ± s.d. (n = 3 technical replicates). h, Transmittance spectra of glass, normal PET, superhydrophilic PET and superhydrophobic PET + PSA at the initial state. n = 1. i, Transmittance spectra of glass, normal PET, superhydrophilic PET and superhydrophobic PET + PSA after 6 h of heating at 30 °C in the presence of water. n = 1. CA, contact angle.

BSA-gated paper-based microfluidic delay valves and electrochromic timer for chronosampling

A simple, passive alternative to the electronic module described previously comprises a series of LFAs coupled with BSA-gated paper-based microfluidic delay valves and electrochromic timers. The result provides an effective solution for chronosampling and defining the timing of sweat collection without the need for electronics (Fig. 5a). Narrow paper-based microfluidic cellulose channels with drop-cast layers of BSA (4%; 1.5 μl) serve as delay valves that direct sweat in a time-sequenced manner into separate LFAs. These valves temporarily restrict the flow until the BSA dissolves, allowing sequential delivery of sweat into each LFA and electrochromic timer pair. Electrochromic timers aligned with the valves and LFAs operate through a colour change associated with the reduction of a layer of polyaniline. Specifically, the timers comprise a two-electrode galvanic cell wherein polyaniline serves as the cathode, nickel metal serves as the anode and human sweat acts as the electrolyte (Fig. 5b). Digital image capture and analysis quantifies the change in colour, thereby allowing determination—with an appropriate calibration factor—of the time for sweat collection into each LFA.

a, Exploded view of a wearable LFA with BSA-gated delay valves, LFAs and an electrochromic timer. b, Exploded view of an electrochromic timer to define the sweat collection time for each channel. c, On-body demonstration of chronosampling functionality by delay valves for a series of LFAs. d, Delay times of the valves for experimental (squares) and simulation (circles and dashed line) data as a function of BSA concentration. e, Contact angles of the BSA-loaded paper-based microfluidic surface as a function of the BSA concentration. f, Delay time of the valves at a concentration of 3% for experimental (squares) and simulation (circles and dashed line) data for varying valve widths. g, Simulated progression of water saturation (blue) and BSA dissolution (red). h, Galvanostatic charge/discharge traces (at a constant current of 5 µA) for a polyaniline cathode (black trace, bottom plot) and a nickel anode (green trace, bottom plot) with representative images and b values (blue symbols, top plot) obtained from the polyaniline electrode at different charge states. i, Discharge traces obtained from electrochromic timers equipped with different load resistors bridging the anode and cathode. j, Electrochromic discharge traces obtained at different temperatures. k, Effect of the exogenous reductive interferent ascorbic acid on the colour (b) of the polyaniline cathodes. l, Comparison of the timer discharge using real and artificial sweat as the electrolyte. m, Timer discharge traces obtained on the body both with (blue symbols) and without (red symbols) pre-treatment chemistry to remove reducing species from the sweat volume (benchtop data are provided for reference; black trace). n, Practical demonstration of the fully integrated device for two participants with iontophoretically stimulated sweat followed by exercise. n = 1. The data represent mean values ± s.d. (n = 3 technical replicates for d–g and i–m).

Benchtop validation and on-body demonstrations of this system show expected sequential filling of each LFA and colorimetric readout of the timing (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 8a). The delay time of the valves increases with higher BSA loading (Fig. 5d), caused by the higher contact angles at higher BSA concentrations (Fig. 5e). The volume and concentration of the drop-cast BSA solution determine the extent of BSA loading. Increasing valve widths lead to shorter delay times (Fig. 5f). The computational framework for simulating these valves integrates multiphase flow dynamics in porous media with a temporal evolution model of dissolution. The valve operates via negative capillary pressure, halting fluid propagation until the dissolution of the BSA induces a dynamic reduction in the contact angle (θ). As the BSA concentration asymptotically approaches 0, the contact angle θ approaches superhydrophilic conditions (θ → 0°)23,24, thereby enabling controlled fluid permeation through the valve architecture (Fig. 5g and Extended Data Fig. 9a–c).

Figure 5h displays information on the timer, specifically the galvanostatic charge/discharge traces obtained from both the polyaniline cathode (black trace) and nickel anode (purple trace) under an applied current of 5 µA. The data include colorimetric b values (blue diamonds) and representative digital photographs of the polyaniline electrode. During reduction, polyaniline displays a sloping voltage plateau at 0.3 V associated with its conversion from the fully oxidized pernigraniline phase to the partially oxidized emeraldine phase. During this transition, the colour of the electrode changes substantially, transitioning from dark blue to pale green (appearing red in photographs due to the roughened Au electrode). Further reduction results in complete conversion of the emeraldine phase to the leucoemeraldine phase, but this conversion does not provide a substantial colour change. Importantly, the voltage that develops at the aniline electrode remains above that of the Ni anode, such that spontaneous discharge of the electrochemical cell is maintained irrespective of the charge state. Similarly, this colorimetric and redox transition is completely reversible upon application of an oxidizing current, as evidenced by the charging trace provided in the bottom half of Fig. 5h.

An optical image of an optimized device on the wrist appears in Extended Data Fig. 9d, showing the paper-based microfluidic sweat collection inlet, BSA valves, electrochromic timers and LFA channels. In the assembled device, spontaneous reduction initiates with the introduction of sweat into the timing well, resulting in polyaniline reduction and a concomittant colour change analogous to that displayed in Fig. 5h. The total timing duration in this assembly depends on a load resistor placed between the anode and cathode that limits the rate of battery discharge. Appropriate selection of the resistance can address the requirements of a specific application (Fig. 5i). Timing durations from several minutes to over one hour are achievable in this way. As timing in this structure relies on the standard reduction potentials of the anode and cathode, it is comparatively less sensitive to temperature effects than analogous diffusion-based colorimetric timing systems8, as displayed in Fig. 5j. Reducing species, such as ascorbic acid, can act as interferents by reacting with the oxidized polyaniline membrane on the timer and discolouring the timer prematurely. A trace of polyaniline on the cellulose paper-based microfluidic channel before the timer reacts with any reducing species before sweat reaches the timer, thereby protecting the timer from discolouration by sweat. Subjecting polyaniline cathodes to progressively increasing concentrations of ascorbic acid reveals the effect of exogenous reducing species on electrochromic timing elements (Fig. 5k). Increasing concentrations of reductants induce spontaneous reduction of the electrode (and a concomitant lightening of the apparent coloration) with full reduction obtained at 100 mM. Following solution pre-reduction, the effect of reductive interferents can be effectively eliminated. Detailed schematics, characterizations and simulations of the timer appear in Extended Data Fig. 10a–k and Supplementary Information sections ‘Principles and dynamics of electrochromic timer’ and ‘Concentration polarization in electrochromic timing elements’.

The resulting structure exhibits excellent performance for real sweat in benchtop (Fig. 5l) and on-body (Fig. 5m) studies. Figure 5n shows a practical demonstration of the device with two participants. Iontophoresis initially induced sweat, which filled the first set of LFAs and electrochromic timers. After 15 min, participants began exercising while collecting sweat for the next sets of LFAs and timers. Both participants showed a slight increase in sweat cortisol concentration following exercise (Fig. 5n).

Cortisol physiology and clinical studies

Trials with human participants demonstrate the ability of the device to monitor daily cycles, the effects of CPTs and the results of disruptions to the sleep cycle caused by jet lag (Fig. 6a,b). The data in Fig. 6c show variations in cortisol concentrations aligned with circadian rhythms for three participants over three days. Cortisol concentrations measured in saliva using an ELISA kit provide data for comparison. Collection of sweat and saliva samples occurred at 17:00 on the first day; 9:30, 12:00, 14:30 and 17:00 on the second day; and 9:30 on the third day. On the first day, the integrated device was used with a 2 h 30 min stimulation interval set by the electronic timer. For both saliva and sweat, cortisol concentrations started low for all participants on the first day (17:00), peaked on the second day morning (09:30), gradually decreased throughout the second day (17:00) and then increased again on the third day morning (09:30). Data from circadian rhythm studies reveal a strong correlation between sweat cortisol and saliva cortisol (r = 0.73) for six participants (Fig. 6d).

a, Schematic of evaluations for circadian rhythms, CPTs and effects of jet lag. b, Photograph of a device on the skin. c, Time-dynamic monitoring of sweat (black) and saliva cortisol (red) over 3 days using the integrated LFA module for 3 participants: P1 (female; 37 years), P2 (male; 24 years) and P3 (male; 38 years). d, Correlation between sweat and saliva cortisol collected from the forearms of n = 6 participants (4 males and 2 females; 26 datapoints; r = 0.73). e, Photograph of a participant performing a CPT with a device mounted on the forearm. f–h, Time-dynamic monitoring of sweat and serum cortisol concentrations before, during and after a CPT for 3 participants: P1 (f; male; 38 years), P2 (g; male; 26 years) and P3 (h; male; 24 years). i,j, Serum (red) and sweat (grey) cortisol concentrations in the morning (09:30) and afternoon (16:00) before travel, immediately after travel and after recovery for a participant (male; 32 years) visiting Seoul from Chicago for 26 days (i) and a participant (female; 24 years) visiting Taipei from Chicago for 20 days (j). k, Sweat cortisol concentrations in the morning (09:30) and afternoon (16:00) before travel, immediately after travel and after recovery for a participant (male; 34 years) visiting Seoul from Chicago for 17 days. l, Correlation between sweat and serum cortisol collected from the forearms of n = 10 participants (8 males and 2 females; 33 datapoints). The data represent mean values ± s.d.

Investigations of the effect of CPTs on sweat and serum cortisol concentrations further highlight the versatility of the integrated system in studying psychoneurological responses to acute stress (Fig. 6e). Sweat iontophoretic stimulation and serum collection occurred on an interval set to 20 min. Both serum and sweat cortisol concentrations increase upon exposure to ice water, reaching peak values at 20 min after exposure, followed by recovery at 40 min after exposure (Fig. 6f–h).

Monitoring disruptions to circadian rhythms is particularly relevant for night shift workers, intercontinental airline travellers and patients with insomnia or excessive sleepiness5. Jet lag, in particular, affects travellers crossing multiple time zomes, sometimes leading to daytime fatigue, insomnia, nausea and early waking25. Measurements of sweat and serum cortisol concentrations offer valuable insights into the impact of jet lag on circadian rhythms before travel, immediately after travel and during recovery (Fig. 6i–k). In one case, a participant travelled from Chicago to Seoul and returned 26 days later, with a nine-hour time difference (Fig. 6i). Cortisol concentrations in sweat and serum were measured 3 days before departure, 1 day after returning to Chicago and 12 days after recovery. Before travel, the participant displayed a typical circadian rhythm, with higher cortisol concentrations in the morning (09:30) and lower concentrations in the afternoon (16:00). After returning to Chicago, the rhythm reversed, with lower cortisol concentrations in the morning (09:30) and higher concentrations in the afternoon (16:00). After 12 days of recovery, the circadian rhythm normalized, with higher cortisol concentrations in the morning (09:30) and lower concentrations in the afternoon (16:00).

In another case, a participant travelled from Chicago to Taiwan and returned 20 days later, with a 13-h time difference (Fig. 6j). Cortisol concentrations for sweat and serum were measured 1 day before departure, 1 day after returning to Chicago and 12 days after recovery. Similar to the first participant, this participant exhibited a typical circadian rhythm before travel, a reversed circadian rhythm after travel and a normalized rhythm after recovery. Additionally, we investigated sweat cortisol concentrations for a participant who travelled from Chicago to Seoul and returned after 17 days, with a 9-h time difference (Fig. 6k). Sweat cortisol concentrations were measured 5 days before departure, 1 day after returning to Chicago and 12 days after recovery. Similar circadian rhythm profiles to those of the other two participants were observed for this participant. A positive correlation between sweat and serum cortisol concentrations was observed, with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of r = 0.73 for 10 participants (Fig. 6l), demonstrating the relevance of sweat cortisol in monitoring the effects of acute stressors, as well as disruptions to circadian rhythms by jet lag, effectively.

Conclusion

The wearable platform introduced here provides a rapid, convenient method for time-sequential sampling of eccrine sweat and measurements of cortisol concentrations, with accuracy and selectivity across a range of physiologically relevant values. The simplicity of the electronics design and the use of quantitative colorimetric readout schemes enabled by AuNF-based LFAs represent two essential features of the technology that are advantages relative to other approaches. The timing circuit and chronosampling valves both enable time-resolved sampling and quantification of sweat cortisol. The circuit autonomously controls sweat stimulation and sampling over extended periods, while the valves support short-term electronics-free operation and compatibility with natural modes of sweating. These two strategies provide complementary options for dynamic sweat monitoring across different use-case scenarios. Comprehensive benchtop studies with artificial sweat provide a basis for understanding all aspects of the operation and for optimizing essential design choices. Human participant studies, including quantitative correlations with concentrations of cortisol measured in saliva and serum using conventional techniques, confirm the practical value of the technology. Additional physiological studies demonstrate the ability to track circadian rhythms, monitor responses to acute stresses (such as those induced by CPTs) and determine the effects of jet lag on circadian misalignment. Potential applications span these scenarios and others, where elevated cortisol levels—particularly those that are persistent—can guide therapeutic intervention. Combination of this platform with biophysical monitoring systems26,27 will extend the capabilities to develop a more comprehensive understanding of stress. Extensions of this type of wearable LFA technology may allow for evaluation of the concentrations of other biochemical species of interest in sweat.

Methods

Study design

Human trials were approved by the Institutional Review Board (STU00220834) at Northwestern University and all participants gave complete, informed, signed consent before participating in the on-body experiments. All 13 human participants (nine males and four females) from the laboratory participated randomly in the experiments based on no specific selection criteria and no compensation. A priori power analysis for a two-tailed bivariate normal model correlation indicated that the minimum sample size to yield a statistical power of at least 0.8 with an alpha of 0.05 and a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of r = 0.7 was 13 for Fig. 6d (26 datapoints) and Fig. 6l (33 datapoints).

Materials and reagents

Unless otherwise noted, all materials were used without further purification. The materials for the absorbent pad (Advanced Microdevices Pvt Type GFB-R4), sample pad (Whatman GF/F glass microfibre filters) and conjugation pad (ClaremontBio glass fibre) were purchased from Advanced Microdevices. The immunopore RP nitrocellulose membrane was purchased from Cytiva. Anti-cortisol antibody (10R-145a) and BSA–CTS (80-IC10) were purchased from Fitzgerald. Gold(III) chloride trihydrate (≥99.9%), gold wire (diameter: 0.5 mm; 99.99%), ammonium chloride (EMSURE), sulfuric acid (95.0–98.0%), aniline (≥99.5%), nickel wire (diameter: 0.5 mm; 99.99%), pilocarpine nitrate, BSA, Agarose Low EEO, sodium phosphate monobasic, sodium phosphate dibasic, aminobenzenethiol, gold chloride hydrate, polyvinylpyrrolidone, cortisol standard (C-106), Tween 20 and mouse anti-IgG antibody (M8642-1MG) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Bright nickel plating solution was obtained from Gold Plating Services. Polyimide films (75 µm thickness; 15.24 cm width) were purchased from Argon. Gold (99.999%) and chromium (99.95%) pellets for electron beam evaporation were obtained from Kurt J. Lesker Company. Double-sided copper-clad laminate (M916137; Pyralux) was purchased from DuPont. Capillary blood collection tubes (15 μl), Protein LoBind Eppendorf tubes (1.5 and 2.0 ml), Whatman cellulose (602H; 1575), alcohol prep pads and Pierce 20× borate buffer were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Carbachol was purchased from AA Blocks. Artificial sweat (1700-0020) was purchased from Pickering Laboratories. The battery holders, switches, low-dropout regulators (1.8 and 3.3 V), rectifiers, voltage regulators, 10 nF capacitors (0201), 1 μF capacitors (0201 and 0402), DC/DC converters, 0.22 μF capacitors (0402), 10 μH inductors (50 mA; 0603), red LEDs (0603), resistors (0201), programmable IC SOT-23-THIN timers, 551-type timer/oscillators (single), hex inverters, JK flip-flop 2 elements and 2-to-4 decoder/demultiplexer were purchased from DigiKey. LiPO batteries were purchased from LiPol Battery. 23 G safety lancets and superhydrophilic PET sheets (B0827YLFV9; Frienda) were purchased from Amazon. Sheets of PET (LX000464) were purchased from Flexconn. Skin adhesives (PC2723U) were purchased from Scapa Healthcare. Pressure-sensitive adhesives (90106NB) were purchased from Adhesives Research. Clear moisture-resistant polyester films (50 μm (8567K22) and 200 μm (8567K62)) were purchased from McMaster-Carr. Saliva collectors (Salivette Cortisol, with synthetic swab, cap) were purchased from Sarstedt Salivette. Human Cortisol ELISA kits (LS-F10024) for sweat and serum were purchased from LifeSpan Biosciences. Cortisol ELISA kits (ab154996; saliva samples) were purchased from Abcam.

AuNF synthesis

A 25-mM solution of 4-aminobenzene-1-thiol (ABT) in 95% ethanol was added to 10 mM HAuCl4 solution containing 0.001% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in ultrapure water with a reaction ratio of 1 to 9 (vol/vol). The resulting mixture turned purple-brown within 10 s. Afterward, the mixtures were triple-washed with centrifugations at 6,000 r.p.m. for 30 min to remove excess reagents.

Conjugation of AuNF with anti-cortisol antibody

The preparation of AuNF–Ab conjugates began by sonicating a solution of AuNFs for 10 s to disperse the material evenly within the tube. Conjugation of antibody to the AuNFs involved mixing 200 μl AuNF stock solution with 800 μl borate buffer (5 mM) and adding 0.5 μl anti-cortisol antibody (1.16 mg ml−1). The borate buffer (5 mM) was obtained by diluting 20 mM borate buffer in deionized water (2% vol borate buffer in deionized water). After ensuring complete mixing, the mixture was incubated for 2 h in a rotating mixer at 10 r.p.m. and then left undisturbed for an additional 5 min at room temperature. At this stage, AuNFs were bound with antibodies. Adding 100 μl 1% BSA solution to the mixture, followed by subsequent incubation for 1 h in a rotating mixer at 10 r.p.m., blocked the unbound surfaces of the AuNFs. After 5 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 2,500g for 35 min at 4 °C and washed with 1 ml borate buffer (5 mM) three times for complete removal of the supernatant. After final centrifugation, the precipitate was reconstituted in 100 μl 0.5% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline and stored at 4 °C until later use.

Preparation of sample and conjugate pads

The sample pad (2.0 mm × 1.5 mm) was treated with 2 μl buffer (pH 6.5) and dried under vacuum at room temperature for 10 min. The sample pad was designed with a staircase structure to facilitate efficient sweat absorption and transport towards the assay components. To reduce non-specific biofouling of AuNF–Ab conjugates, the conjugate pad was initially impregnated with 5 μl of a working buffer containing 30% (wt/vol) BSA and Tween 20 and dried under vacuum at room temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, AuNF–Ab conjugates were deposited onto the conjugate pad at a volume of 2 μl and dried under the same conditions.

Preparation of nitrocellulose membranes with test and control lines

Nitrocellulose membranes were miniaturized for wearable implementation and cut into 2-mm-wide pieces using an infrared laser (LPKF) before assembly into standard LFA cassettes. The test line reagent comprised BSA–CTS at a 1/8 dilution factor with a final concentration of 0.125 mg ml−1, whereas the control line contained an anti-mouse IgG antibody at 1 mg ml−1. Both reagents were dispensed onto the nitrocellulose membrane using predefined parameters, including a dispensing volume of 0.325 μl mm−1 and a speed of 100 mm s−1, followed by drying in a vacuum chamber at room temperature for 20 min. The test and control lines were spaced 5 mm apart for optimal visualization and signal differentiation.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic surfaces

The preparation of superhydrophobic surfaces involved fluorine plasma treatment using a deep reactive-ion etching system (SPTS). The PET substrate with a thin layer of adhesive (FLX000464; Flexcon) was placed in the chamber with the adhesive side facing up, followed by evacuation to a pressure of 1.6 Pa. CF4 gas was then introduced at a flow rate of 50 sccm, with a glow discharge at 200 W for 2 min.

Fabrication of paper-based microfluidic BSA valves

Dropcasting 1.5 μl BSA (4% wt/vol; Sigma–Aldrich) solution onto the designated valve location in the cellulose paper completed the preparation of BSA-gated paper-based microfluidic delay valves, followed by drying under vacuum for 20 min.

Assembly of the wearable LFA system

A 3D printer (Formlabs) created the guide jig for the alignment and assembly of different layers. The sequential assembly of the chamber wall, PET substrate, skin adhesive and cellulose collection paper was conducted by aligning the edges of each layer using the 3D-printed guide jig. LFA components and covers were assembled by flipping the device and assembling from the opposite side. Assembly of system was complete after all four LFA modules were placed in the chamber and covered by the superhydrophilic viewing window.

Fabrication of the electrochromic timer

Electrochromic timers were assembled as a two-terminal electrochemical cell wherein polyaniline served as the cathode, nickel metal served as the anode and human sweat acted as an electrolyte. Timing elements were fabricated from thin-film Au electrodes supported on flexible polyimide, as follows. Substrate materials were initially prepared by electron beam deposition of metal films (100 nm Au, with a 20-nm Cr adhesion layer; AJA International) onto a large polyimide substrate (75 µm thickness; surface area: ~700 cm2) whose surface was cleaned (sequential rinsing with water and isopropanol) and treated with ultraviolet ozone (UVOCS; 5 min). Deposition was performed at a constant rate of 1 Å s−1. Following deposition, electrode traces were patterned using an ultraviolet laser micromachining system (ProtoLaser U4; LPKF Laser and Electronics SE) at an output power of 0.5 W in a single pass. This laser power was sufficient to affect the complete ablation of the Au/Cr layer along the cutting path, with little damage to the underlying polyimide substrate. Arrays of eight timers were patterned in this fashion in preparation for subsequent chemical treatment by electrodeposition.

Cathode preparation

The high reflectivity of gold electrodes before roughening places tight constraints on both the lighting and the view angle as ambient reflections strongly impact the apparent electrode colour. Roughening the surfaces of these electrodes reduces the reflectivity and facilitates the angle-independent extraction of colour information, thereby improving the timing reliability. Cathode preparation began with the application of a roughened Au layer to reduce the reflectivity of the bare Au substrate. Rough gold was deposited by cyclic voltammetry between −1.8 and 0.2 V (scan rate: 0.5 V s−1) from a 10-mM solution of HAuCl4 in 2.5 M NH4Cl supporting electrolyte using an Au slug as the counter and reference electrode28. A total of 25 cycles were applied, pausing every five cycles to mix the electrolyte solution with a pipette to reduce the accumulation of bubbles on the electrode surface. Following roughening, polyaniline was deposited from a monomer solution of 0.5 M aniline in 1 M H2SO4 by the application of a constant reducing current of 50 µA for 400 s using an Au slug as the counter electrode and a double-junction Ag/AgCl electrode (BASI) as the reference. To ensure even and dark coloration of polyaniline cathodes, electrodes were subsequently oxidized by polarization to 0.4 V in pH 4.5 solution before cutout and assembly (again using Ag/AgCl as the reference and Au as the counter electrode).

Anode preparation and timer cutout

Nickel anodes were applied by electrodeposition from a commercially available bright nickel plating bath (Gold Plating Services) by the application of a reducing potential of −1.5 V versus Ni metal for 120 s using an Ni wire as the counter and reference electrode. Following electrodeposition, individual timers were cut from the substrate (ProtoLaser U4; 0.5 W; 30 repetitions) for integration with the paper-based microfluidic assembly.

Electric field simulation for iontophoresis

Numerical simulations were conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics, employing tetrahedral mesh elements for all of the computational analyses. A refined mesh with feature sizes smaller than one-fifth of the electrode width was adopted to ensure accuracy. The numerical solver dynamically controlled time step sizes through backward differentiation formulas, with the initial step sizes kept small to prevent singularity. The total current was applied to the anode during stimulation, whereas zero external electric potential was applied to the cathode. The material properties and key parameters used in the simulation included: a skin conductivity σ of 0.026 S m−1 (ref. 29); a diffusion coefficient D of 14.8 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 (ref. 30); a reaction rate constant k of 0.05 min−1; an initial carbachol concentration c0 in the carbagel of 1%; a sweat rate coefficient ζ/c0 of 40 μl min−1; a critical concentration ct/c0 of 0.004; and a saturation concentration cmax/c0 of 0.025.

FEA simulation for the BSA-gated paper-based microfluidic delay valve

Numerical simulations were conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics31,32. Darcy’s law interface23 was utilized to describe the fluid flow through the filter paper (porous medium). The mass source was utilized to describe the inlet flow rate qin of 1 μl min−1 in the centre circle. A no-flow condition was applied across the vertical boundaries, whereas the upper and lower boundaries were set to a zero-pressure outlet condition. The phase transport in the porous medium interface was employed to define the water saturation phenomenon within the filter paper. The Brooks and Corey model33 was utilized to model the capillary pressure in two-phase flow, denoting the entry capillary pressure as pec = \(\frac{2\gamma \cos \theta }{{r}_{\rm{c}}}\) 34, where γ is the surface tension, rc is the pore radius and θ is the contact angle measured from the experiments, dependent on the BSA concentration φ. To define the BSA dissolution mechanism, the Nernst–Brunner equation35 was utilized, combined with the water fraction s in the filter paper: \(\frac{\Delta \varphi }{\Delta t}\) = −χφs, where φ is the BSA concentration and χ is the dissolution rate constant. The domain ordinary differential equation and differential algebraic equation interface was employed to describe the BSA dissolution. The material properties and key parameters used in the simulation included: a paper porosity ε of 0.8; a pore radius rc of 1 μm; a surface tension γ of 72.3 mN m−1; a pore size distribution index λp of 2; a permeability K of 1 × 10−13 m−2; and a dissolution rate constant χ of 1.8% min−1.

Preparation of the encapsulation layer

A 3D printer (Formlabs) created the sandwich mould for baking the encapsulation layer. Smooth-On Dragon Skin 10 (with a mixing ratio of 1:1) was poured into the mould, degassed in a vacuum chamber for 30 min and baked in a 75 °C oven for 3 h.

Diurnal cycle for sweat cortisol

Five healthy volunteers (four male and one female) with regular sleep–wake rhythms participated in a diurnal cortisol cycle test. Participants did not have any food intake for at least 60 min before each testing. The on-body testing comprised sweat stimulation sessions throughout three consecutive days, including: (1) day one at 17:00; (2) day two at 09:30, 12:00, 14:30 and 17:00; and (3) day three at 09:00. After sanitizing the forearm, sweat was stimulated and collected simultaneously by the iontophoresis-integrated LFA device, where 130-μA current was applied for 5 min. Saliva samples were collected immediately after the sweat stimulation and stored under −18 °C until further use. The image of the LFA assay was taken with an RGB Calibrate ColorChecker 24 (Classic Nano; 24 mm × 40 mm) 1 h after the complete wetting of the LFA strip.

For saliva collection, volunteers thoroughly rinsed their mouth with water 15 min before collection. A saliva salivate (Sarstedt) was used to collect saliva samples by keeping a cotton swab inside the mouth for 5 min. The participants avoided chewing the swab during collection. After 5 min, the cotton swab was returned to the salivate and centrifuged for 2 min at 2,000g. The supernatant of saliva sample was then collected using a pipette and stored in a −18 °C freezer until use.

CPTs

Five healthy volunteers (four males and one female) participated in the standard CPT in the afternoon (between 15:00 and 17:00) to avoid the effect of diurnal cortisol cycle variation. The CPT began with an initial sweat collection session through iontophoresis on the forearm of the dominant hand for 5 min. At the same time, capillary blood samples were collected from the non-dominant hand for the purpose of baseline blood cortisol concentration determination. After baseline sample collection, the iontophoresis device with a timer was turned on for sequential sweat stimulation. Immediately after the initial iontophoresis, volunteers immersed the dominant hand wearing the integrated LFA device into the icy cold water (2 °C) and removed the hand after 3 min. Fresh capillary blood was collected from the non-dominant hand at different stages synchronized with iontophoresis time (immediately after the CPT, at 20 min and at 40 min).

For capillary blood collection, an alcohol pad was used to sanitize the volunteer’s fingers before collection. A 21-G lancet punctured the sanitized finger to draw blood droplets. A 15-μl capillary blood collection tube (PTS Diagnostics) was used to collect blood droplets of over 50 μl into a 1.5-ml Eppendorf microtube. The collected blood sample was set aside for 40 min at room temperature for blood clotting. After 40 min resting, the blood sample was centrifuged at 2,000g for 15 min to separate the serum from the clotted white and red blood cells. The supernatant serum was collected in a 1.5-ml Eppendorf microtube and stored in a −18 °C freezer until use.

Jet lag experiment

Four healthy volunteers (three males and one female) participated in the jet lag study. All volunteers experienced a time difference of more than eight hours, as well as varying degrees of jet lag symptoms. All volunteers took flights from the USA to East Asia and stayed there for more than two weeks. Before travel, baseline sweat cortisol concentrations were quantified using the LFA device in the morning (09:30) and afternoon (16:00). For two participants, capillary blood samples were collected at the same time, with sweat cortisol measurement. Likewise, sweat and blood samples were collected and measured in the morning (09:30) and afternoon (16:00) on the first and twelfth day after the return flight.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro (version 2022; OriginLab) and G*Power 3.1.9. For Fig. 2c, four different batches were imaged to characterize the shape and size of the AuNFs. The selected image is representative of approximately 85 nanoparticles.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All of the data generated and analysed during the study are included in the paper, extended data figures and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code related to the LFA data presented in this paper is available at https://github.com/cho8690/LFA.git.

References

Weber, C. J., Clay, O. M., Lycan, R. E., Anderson, G. K. & Simoska, O. Advances in electrochemical biosensor design for the detection of the stress biomarker cortisol. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 416, 87–106 (2024).

Ok, J., Park, S., Jung, Y. H. & Kim, T. I. Wearable and implantable cortisol-sensing electronics for stress monitoring. Adv. Mater. 36, e2211595 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Soft, skin-interfaced microfluidic systems with integrated immunoassays, fluorometric sensors, and impedance measurement capabilities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 27906–27915 (2020).

O’Byrne, N. A., Yuen, F., Butt, W. Z. & Liu, P. Y. Sleep and circadian regulation of cortisol: a short review. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 18, 178–186 (2021).

Zee, P. C. & Goldstein, C. A. Treatment of shift work disorder and jet lag. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 12, 396–411 (2010).

Upasham, S., Churcher, N. K. M., Rice, P. & Prasad, S. Sweating out the circadian rhythm: a technical review. ACS Sens. 6, 659–672 (2021).

Mohammadi, M. H. et al. Saliva lab-on-a-chip biosensors: recent novel ideas and applications in disease detection. Microchem. J. 168, 106506 (2021).

Cho, S. et al. A skin-interfaced microfluidic platform supports dynamic sweat biochemical analysis during human exercise. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eado5366 (2024).

Choi, J., Ghaffari, R., Baker, L. B. & Rogers, J. A. Skin-interfaced systems for sweat collection and analytics. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar3921 (2018).

Kim, J., Campbell, A. S., de Avila, B. E. & Wang, J. Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 389–406 (2019).

Shajari, S. et al. MicroSweat: a wearable microfluidic patch for noninvasive and reliable sweat collection enables human stress monitoring. Adv. Sci. 10, e2204171 (2023).

Parlak, O., Keene, S. T., Marais, A., Curto, V. F. & Salleo, A. Molecularly selective nanoporous membrane-based wearable organic electrochemical device for noninvasive cortisol sensing. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar2904 (2018).

Wang, B. et al. Wearable aptamer-field-effect transistor sensing system for noninvasive cortisol monitoring. Sci. Adv. 8, eabk0967 (2022).

Torrente-Rodriguez, R. M. et al. Investigation of cortisol dynamics in human sweat using a graphene-based wireless mHealth system. Matter 2, 921–937 (2020).

Rivas, L., Merkoci, A., Hu, L. M., Parolo, C. & Idili, A. Rational approach to tailor Au–IrO2 nanoflowers as colorimetric labels for lateral flow assays. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 4151–4161 (2023).

Liang, R. S. et al. A sensitive gold nanoflower-based lateral flow assay coupled with gold staining technique for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen. Microchim. Acta 191, 434 (2024).

Lai, W. H. et al. Gold nanoflowers labelled lateral flow assay integrated with smartphone for highly sensitive detection of clenbuterol in swine urine. Food Agr. Immunol. 30, 1225–1238 (2019).

Cai, P., Wang, R., Ling, S. & Wang, S. Rapid and sensitive detection of tenuazonic acid in agricultural by-products based on gold nano-flower lateral flow. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 1021758 (2022).

Zhan, L. et al. The role of nanoparticle design in determining analytical performance of lateral flow immunoassays. Nano Lett. 17, 7207–7212 (2017).

Gupta, R. et al. Ultrasensitive lateral-flow assays via plasmonically active antibody-conjugated fluorescent nanoparticles. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 1556–1570 (2023).

Meng, F. F., Xu, Y., Wu, Z. Q. & Chen, H. Transparent and superhydrophilic antifogging coatings constructed by poly (N-hydroxyethyl acrylamide) composites. Colloids Surf. A 642, 128724 (2022).

Hu, X. B. et al. Highly transparent superhydrophilic graphene oxide coating for antifogging. Mater. Lett. 182, 372–375 (2016).

Patari, S. & Mahapatra, P. S. Liquid wicking in a paper strip: an experimental and numerical study. ACS Omega 5, 22931–22939 (2020).

Patari, S., Chowdhury, I. U., Kumar, J. & Mahapatra, P. S. Dynamics of liquid flow through fabric porous media: experimental, analytical, and numerical investigation. Phys. Fluids 35, 102102 (2023).

Cingi, C., Emre, I. E. & Muluk, N. B. Jetlag related sleep problems and their management: a review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 24, 59–64 (2018).

Xu, C. et al. A physicochemical-sensing electronic skin for stress response monitoring. Nat. Electron. 7, 168–179 (2024).

Yoo, J. Y. et al. Wireless broadband acousto-mechanical sensing system for continuous physiological monitoring. Nat. Med. 29, 3137–3148 (2023).

Sanzó, G. et al. Bubble electrodeposition of gold porous nanocorals for the enzymatic and non-enzymatic detection of glucose. Bioelectrochemistry 112, 125–131 (2016).

Peters, M. J., Stinstra, J. G. & Hendriks, M. Estimation of the electrical conductivity of human tissue. Electromagnetics 21, 545–557 (2001).

Muller, W., Misgeld, U. & Heinemann, U. Carbachol effects on hippocampal neurons in vitro: dependence on the rate of rise of carbachol tissue concentration. Exp. Brain Res. 72, 287–298 (1988).

Chowdhury, I. U., Mahapatra, P. S. & Sen, A. K. Shape evolution of drops on surfaces of different wettability gradients. Chem. Eng. Sci. 229, 116136 (2021).

Chowdhury, I. U., Mahapatra, P. S., Sen, A. K., Pattamatta, A. & Tiwari, M. K. Autonomous transport and splitting of a droplet on an open surface. Phys. Rev. Fluids 6, 094003 (2021).

Brooks, R. H. & Corey, A. T. Properties of porous media affecting fluid flow. J. Irrig. Drain. Div. 92, 61–88 (1966).

Masoodi, R. & Pillai, K. A general formula for capillary suction-pressure in porous media. J. Porous Media 15, 775–783 (2012).

Siepmann, J. & Siepmann, F. Mathematical modeling of drug dissolution. Int. J. Pharm. 453, 12–24 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics at Northwestern University. This work made use of the NUFAB facility of Northwestern University’s NUANCE Center, which has received support from the SHyNE Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the International Institute for Nanotechnology and Northwestern University’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center programme (NSF DMR-2308691). This work made use of the EPIC facility of Northwestern University’s NUANCE Center, which has received support from the SHyNE Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the International Institute for Nanotechnology and Northwestern University’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center programme (NSF DMR-2308691). This work was supported by the Northwestern University High Throughput Analysis Laboratory and Keck Biophysics Facility, the shared resource of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, supported partly by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center (Support Grant P30 CA060553). We acknowledge use of the facility at IMSERC at Northwestern University, which has received support from SHyNE Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633) and the National Institutes of Health (1S10OD012016-01 and 1S10RR019071-01A1). The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health sleep and circadian training grant (T32HL007909 to K.M.), the Turkish Fulbright Commission under the Fulbright Postdoctoral Program (FY-2020-TR-PD-10 to S.Ş.), a postdoctoral fellowship provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (to S.S.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12202241 to Z.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Soongwon Cho, R.S. and J.A.R. conceived of the project. Soongwon Cho, S.S., Y.X., S. Oh and J.A.R. designed the research. Soongwon Cho, S.S., Y.X., R.S., S.Ş., I.H. and M.L. designed and developed the AuNF-based LFA. Soongwon Cho, S.S., Y.X., L.F., M.L., K.-C.P., X.M. and S. Oh developed the wearable version of the LFA. S.S., Soongwon Cho and Jinho Park developed the method and codes for the LFA analysis. Soongwon Cho, S. Oh, M.L. and Y.X. developed the integrated iontophoresis with a smart timer. Soongwon Cho, S.S., Seunghee Cho and Y.X. developed the BSA-gated delay valves for chronosampling. Soongwon Cho, K.M. and Y.X. developed the wearable electrochromic timer. K.M. performed the FEA simulations for the electrochromic timer. Z.L., S.L. and Y.H. performed the FEA simulations for the iontophoresis and BSA-gated delay valves. Jinho Park and H.L. developed and synthesized AuNF. Soongwon Cho, Y.X., S.S., M.L., R.F.N., Y.Z., Y.-w.K., C.P., Jeonghwan Park, Y.-T.H., S.W., H.B., S. Opal, Seunghee Cho, A.T. and Z.C. assisted with and participated in the human participant trials. A.J.A. developed the codes for the colorimetric analysis. R.G. provided the sweat collection equipment and devices. J.A.R., Y.X., S.S., K.M., Z.L., M.L., S. Oh and Soongwon Cho wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.A.R., A.J.A. and R.G. are co-founders of a company, Epicore Biosystems, that develops and commercializes microfluidic devices for sweat analysis, but using other sensing techniques. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sensors thanks Yei Hwan Jung, Hui Kong and Sihong Wang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Development of a highly sensitive LFA for picomolar detection of sweat cortisol.

a, Schematic illustration of AuNF synthesis chemistry. b, Measurement of zeta potential for AuNF incubated for 1 h with varying concentrations of anti-cortisol antibody. n = 3. c-f, Demonstration of chronosampled LFA with increasing cortisol concentrations: 0 (c), 1 (d), 10 (d) and 100 ng/mL (f). Scale bar, 5 mm. g, An optical image of an LFA strip at a cortisol concentration of 1000 ng/mL. Scale bar, 5 mm. h, Adjustment of artificial sweat and real sweat to pH 6.5 using phosphate buffer within the sample pads. Measured color (a*, black) and pH values (red) are shown. n = 3. i, pH titration curve for artificial sweat (pH 4.3) using 1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). n = 1. j, Evaluation of different working buffer concentrations (1:1 ratio of BSA to Tween 20) for LFA sensitivity. n = 3. k, Performance comparison of different working buffer types (Trixton, Tw20, 10G and PVP) for AuNF transport through the NC membrane. Scale bar, 10 mm. l, Effect of varying BSA-CTS concentrations (from 1 mg/mL to 0.125 mg/mL) on the visual appearances of the test lines. Scale bar, 2 mm. m, Effect of BSA-CTS dilution factors (4X and 8X), and anti-cortisol antibody dilution factors (6X and 8X) on the control/test line ratios at cortisol concentrations of 0, 1, and 100 ng/mL. n = 3. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 technical replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Characterization of a highly sensitive LFA for picomolar detection of sweat cortisol.

a, Effect of cortisol ab dilutions (1X, 2X, 4X, 6X and 8X) on the control/test line ratios at cortisol concentrations of 0, and 100 ng/mL. n = 3. b, Effect of flow rate on the control/test line ratios for cortisol concentrations of 0, and 100 ng/mL prior to working buffer optimization. n = 3. c, Effect of injection volumes (10, 15, and 20 μL) on the control/test line ratios at cortisol concentrations of 1 and 100 ng/mL. n = 3 prior to optimization of assay components. d, Effect of lighting color temperature (4500, 5000, 5500 K) on the control/test line ratios at cortisol concentrations of 0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ng/mL. n = 3. e,f, Comparison of control/test line ratios of LFA images, at cortisol concentrations of 0, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ng/mL, taken with a smartphone camera (Iphone 16 pro) and a digital camera (Canon) at lighting color temperatures of e, 5500 K, and f, 4500 K. n = 3. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 technical replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Analytical protocol for the test line and control line signals for wearable LFA.

a, Original image of an assay with color checker for calibration. Scale bar, 5 mm. b, Image of the assay after applying color calibration. Scale bar, 5 mm. c, Separated green channel image. Scale bar, 5 mm. d, Green channel image with a yellow line for LFA profile analysis. Scale bar, 5 mm. e, Straightened image of the yellow line for LFA profile analysis, representing the gray levels of the test and control lines. f, Gray level profiles of the straightened image of the yellow line showing the test and control line signals. g, Flow chart for LFA analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Electrical timer for time-sequenced iontophoretic stimulation.

a, An optical photograph of the implemented electrical circuit including electrical timer, iontophoresis stimulation and power management integrated circuit (PMIC). Scale bar, 5mm. b, A close-up photograph of the implemented electrical timer circuit for time-sequenced iontophoretic stimulation, fabricated on a flexible PCB. Scale bar, 5 mm. c, An optical photograph of the wireless charging module. Scale bar, 5 mm. d, Schematic of the electrical timer circuit. e, Fully implemented circuit for time-sequenced iontophoretic stimulation. f, Power management integrated circuit and operating principle for wireless charging. g, Experiental results showing interval time as a function of long timer resistance. n = 3. h, Iontophoresis stimulation time as a function of short timer resistance. n = 3. i, Experimental results showing the cycle variation in sweat stimulation time and time interval between stimulation. n = 3. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 technical replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Optimization of carbagel iontophoresis for simultaneous sweat stimulation and paper-based microfluidic collection.

a, Schematic illustration of integrated iontophoresis with a paper-based microfluidic sweat collection channel. b, Total sweat volume collected by the paper-based microfluidic channel following iontophoretic stimulation using carbagel (black) and pilogel (red). n = 3. c, Current stability of the iontophoretic modules with different resistances. d, Simulation setup for estimating sweat volume, including the anode, cathode, and extended region for modeling carbachol diffusion within the skin (total current: 130 μA, duration: 10 min). Scale bar, 10 mm. Color bar in logarithmic scale. e, Sweat rate estimation model based on iontophoretically delivered carbachol concentration, using threshold concentrations for sweat initiation and maximum sweat rate. f, Experimental (red, black) and simulated data (blue) for total sweat volume collected at varying current densities (1% carbagel, 1.5 mm spacing). n = 3. g, Experimental sweat rate in two subjects over 40 min under carbagel stimulation at varying current densities. n = 3. h, Simulated sweat rate over 40 min at varying current densities. i-k, Top and cross-sectional views of the electrical field distribution in the iontophoretic module at current densities of 130 μA (i), 41 μA (j) and 19 μA (k). Color bar in logarithmic scale. l,m, Successful generation of sufficient sweat volume using the integrated iontophoresis system, paper-based microfluidic collection channel, and LFA. Scale bar, 5 mm. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3 technical replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Prevention of sweat vapor condensation and unwanted hydrophilic wicking through the surface of the top window.

a, Schematic illustration of sweat vapor condensation on a superhydrophobic cover. b, Photograph of a wet LFA strip with dyed artificial sweat, showing water droplet condensation on the viewing window. Scale bar, 5 mm. c,d, Schematic illustrations of LFA device with a test paper for visualizing unwanted hydrophilic wicking through a superhydrophilic cover (c) and a combination of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic covers (d). e,f, Schematic illustrations of LFA devices after pumping artificial sweat with a superhydrophilic cover with a wet test paper (e) and with a combination of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic cover with a dry test paper (f). g,h, Optical images of LFA devices with a test paper before sweat wicking with a superhydrophilic cover (g) and a combination of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic cover (h). Scale bar, 5 mm. i,j, Optical images of LFA devices after pumping artificial sweat with a superhydrophilic cover with a wet test paper (i) and a combination of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic cover with a dry test paper (j). Scale bar, 5 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Surface characterizations of superhydrophilic and superhydrophobic surfaces.

a, Contact angle measurements for a PET film. b, Contact angle measurements for a superhydrophilic PET film. c, Atomic force microscopic (AFM) image of a PET film. Scale bar 1 μm. d, AFM image of a superhydrophilic PET surface formed by a coating of silica nanoparticles. Scale bar 1 μm. e, The effect of reactive ion etching power on the contact angle of a superhydrophobic PET + PSA substrate. n = 3.

Extended Data Fig. 8 In vitro chronosampling for a set of LFAs modulated by BSA delay valves.

Sequential filling of 5 LFA channels with artificial sweat by a series of BSA delay valves at a flow rate of 1 μL/min. Scale bar, 5 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Simulation setup and results for BSA-valves and a device image.

a, Boundary conditions for the simulation. b, Water saturation at the outlet (right) for BSA loading concentrations (w/v, 1 μL) of 0%, 1%, 2%, and 3%. c, Simulated progression of water saturation (blue) and BSA dissolution (red) for valves with 3% BSA, 2% BSA, and 1% BSA. d, Fully integrated system incorporating paper-based microfluidics, electrochromic timing elements, and LFAs to facilitate and characterize the time-dependent collection and chemical analysis of sweat. Scale bar, 10 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Principles, characterizations and simulations for the electrochromic timer.

a, Schematic illustration of an electrochromic timer. b, Optical and scanning electron micrographs of timer electrodes at different points during assembly. c, Cyclic voltammetry of smooth and electrochemically roughened Au electrodes, illustrating an increase in the electroactive surface area following roughening. d, Electroactive surface areas computed from the results in c. e, Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of bare and roughened Au electrodes. f, Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of an electrochromic timer using artificial sweat (pH = 4.5) as the electrolyte. The inset depicts a modified Randle’s circuit used to fit the experimental data. g, Cell discharge curves obtained at different discharge currents. h, Correlation between discharge current and discharge time. i, Correlation between discharge current and cell capacity. j, Colorimetric response obtained from timers both in the presence and absence of chemical pretreatments to remove reductants from incoming sweat. Data are presented as mean values ± SD. (n = 3) k, Simulated pH gradients within electrochromic timing elements with different load resistors computed at the end of cell discharge. Irrespective of load resistor, only modest changes to solution pH are obtained, although discharging at elevated current densities (low resistance) results in exaggerated concentration gradients.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary discussion.

Supplementary Video 1

Chronosampling BSA valves.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 2–6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Figs. 1–10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, S., Shajari, S., Xiong, Y. et al. Wearable lateral flow assays for cortisol monitoring with time-dynamic sweat sampling and sensing by electrochromic timers. Nat. Sens. 1, 85–98 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44460-025-00005-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44460-025-00005-z