Abstract

This study presents a wafer-level sealed silicon cavity (SSC) microacoustic integration platform to address the limitations in the cavity Silicon-on-Insulator (C-SOI) wafers for the 5G/6G wireless communication system. The proposed SSC platform features an extremely smooth suspended membrane with adjustable thickness, flexible cavity shapes with high density, self-formed acoustic wave confinement steps, stable temperature coefficient of frequency (TCF), and highly integrated compatibility with complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS). A surface smoothing method based on wet oxidation for SSC wafers is presented, which achieves a root mean square (RMS) roughness on the cavity surface of 1.5 nm for the first time. Based on the presented SSC platform, an Al0.75Sc0.25N sealed cavity bulk acoustic wave resonator (S-BAR) is designed, fabricated, and characterized. The experimental results show that the asymmetric second-order (A2) Lamb mode of S-BAR is enhanced for higher frequency with a maximum piezoelectric coupling coefficient (\({k}_{t}^{2}\)) of 9.53%, a maximum quality factor (Q) of 439, and a TCF of −11.44 ppm/K. Different designs’ piezoelectric coupling coefficient distribution is consistent with the theoretical prediction. The proposed smoothing process increases the S-BARs’ quality factor by ~400%. The frequency shift caused by the temperature (absolute value of TCF) is reduced by 62% compared with the traditional Al0.75Sc0.25N thin film bulk acoustic wave resonator (without temperature compensation). The enhanced performances demonstrated the potential of SSC in the next-generation highly integrated RF communication systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microacoustic devices are a class of micrometer/nanometer-scale electroacoustic components designed to generate, sense, control, or utilize acoustic waves. With the combination of piezoelectric materials and micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) technology, microacoustic devices have been widely developed, including acousto-optic modulator1,2,3, quantum acoustic microsystem4,5,6, piezoelectric micromachined ultrasound transducer (PMUT)7,8,9, radio frequency (RF) acoustic resonators10,11,12, etc. In terms of PMUT13, monolithic integration can achieve the highest density of transducers and a wider variety of array geometries. Moreover, an integrated solution is ideal for minimizing system size and reducing power consumption for wearable or implantable microacoustic devices, such as intravascular ultrasound imaging systems14. Beyond them, RF communication (5G/6G) is the biggest market for microacoustic devices, and next-generation wireless communication systems require higher integration density. Considering the over 80 microacoustic resonators/filters integrated inside the latest mobile phone, integrated electroacoustic modules not only reduce the board footprint but also significantly reduce the parasitic effects introduced by the wiring and components15. However, the existing microacoustic platforms present significant challenges to support the subsequent fabrication process for on-chip integration due to the special structure or process for microacoustic devices.

Most microacoustic devices require suspended structures on the substrate (e.g., silicon) to support the free out-of-plane vibration. To date, two wafer-level platforms and one process have been developed to achieve suspended structures in microacoustic systems: the silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer platform, the cavity silicon-on-insulator (C-SOI) wafer platform, and the sacrificial layer process. As is shown in Fig. 1a, the SOI wafer features three layers: silicon handle substrate, oxide layer, and silicon device layer. The SOI wafer platform, combined with the back etching process, can be used for the carrier substrate of thin film bulk acoustic resonator (FBAR)16. The back etching process selectively removes the silicon substrate to create a hollowed-out region and form the suspended structure. The process has the drawback of weakening the wafer, requiring additional support material17. Additionally, the aspect ratio constraints of backside etching necessitate a larger effective area for each device, thereby reducing the number of devices obtainable per wafer. In contrast to backside etching, the releasing process is another approach for suspended mechanical acoustic structures on SOI wafers by front etching. The construction of the suspended structure is achieved by isotropic dry etching of the substrate through release windows18. The disadvantage of this approach is that the etching boundaries of the release area cannot be accurately defined. Most importantly, this approach leads to incompatibility issues (between the etchant and device material) and hinders further microfabrication. C-SOI technology was invented to overcome the shortcomings of the SOI platform for microacoustic devices19. As illustrated in Fig. 1b, the C-SOI wafer integration platform features pre-etched cavities within the handle silicon. This approach mitigates potential damage to other components from the final etch. The advent of PMUT based on C-SOI wafers has led to a breakthrough in ultrasonic fingerprint recognition technology8. Nevertheless, this process requires wafers to have high uniformity for the uniform operating frequency of the microacoustic device, which leads to a high manufacturing cost. If C-SOI is used for high-frequency RF acoustic resonators, a substrate removal process is still required to ensure effective electromechanical coupling. The sacrificial layer process is the third mainstream process for MEMS microacoustic devices. The sacrificial layer is created before device fabrication and is removed after device fabrication to achieve device suspension20,21. This method requires a complex multilayer manufacturing process and needs to add a sealing layer13 for etching holes to support the subsequent fabrication processes. In summary, there are currently very few wafer-level platforms with low-cost, simple process, high-density suspended structure, and robust mechanical structure for microacoustic device integration.

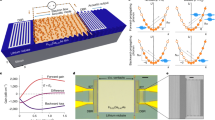

In this work, we present a wafer-level sealed silicon cavity (SSC) microacoustic platform, as shown in Fig. 1c–e. The SSC wafer features a smooth suspended silicon membrane with controllable thickness, customizable cavity shapes with high density, self-forming acoustic wave confinement steps, and improved temperature coefficient of frequency (TCF) for acoustic resonators. The construction of the SSC is realized by DRIE and a rapid annealing process with low cost and simple steps. Furthermore, the SSC platform is sturdy enough to support both MEMS and CMOS fabrication/bonding/integration. Additionally, the SSC platform can excite higher-order Lamb waves with enhanced electromechanical coupling in the 5G/6G frequency bands. Different from the other annealing smoothing process22,23, a wet oxidation-based surface smoothing process for the SSC wafer was proposed, achieving a root mean square (RMS) roughness of 1.5 nm on the cavity surface for the first time. The extremely flat cavity surface supports the subsequent high-quality material film deposition. Based on the presented SSC platform, we have designed, fabricated, and characterized C-band AlScN sealed cavity bulk acoustic wave resonators (S-BARs). The structure of S-BAR is shown in Fig. 1c. Compared with the conventional FBAR24, the proposed S-BAR can improve both electromechanical coupling and TCF. The measured data show that the fabricated S-BARs achieve a maximum quality factor (Q) of 439, a peak piezoelectric coupling coefficient (\({k}_{t}^{2}\)) of 9.53%, and a TCF of −11.44 ppm/K from 113 to 473 K for asymmetric second-order (A2) Lamb mode. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed SSC platform could be a novel promising integrated microacoustic platform to replace C-SOI for ultrasound and microwave applications.

Results and discussion

Mode analysis and design of S-BAR

Figure 1 shows the structure of the designed S-BAR, which consists of an intrinsic (100) silicon substrate with a sealed cavity, bottom Pt electrode, middle piezoelectric Al0.75Sc0.25N material, and top Al electrode, respectively. The membrane above the sealed cavity is crystalline silicon with a tunable thickness and smooth surface. The sealed cavity has a self-formed boundary with a length and height of ~1 μm and 600 nm, which can help suppress the lateral transmission of acoustic waves to reduce acoustic loss. Pt can provide low resistance as the bottom metal and has good lattice matching with Al0.75Sc0.25N. Al is chosen as the top metal due to its high conductivity. Different from the classical FBAR operating on the symmetric first-order (S1) Lamb mode25, the proposed S-BAR can work on the asymmetric second-order (A2) mode26 with \({k}_{t}^{2}\) enhancement. The simulated admittance response of S-BAR in Fig. 2a shows that the thickness ratios (\(\alpha\)) of the piezoelectric Al0.75Sc0.25N layer thickness to the total thickness can be used to generate A2 mode. When the \(\alpha\) is close to 1, the S1 mode of the resonator has the largest \({k}_{t}^{2}\) (\({k}_{t}^{2}=({f}_{p}^{2}-{f}_{s}^{2})/{f}_{p}^{2}\)) among all the resonant modes, where the \({f}_{s}\) and \({f}_{p}\) are the resonance and anti-resonance frequency, respectively. When the α is close to 0.3, the A2 mode of the resonator is fully excited, having the largest \({k}_{t}^{2}\). The principle behind it is that the silicon membrane participates in tuning the stress distribution of the resonator. The optimized stress distribution can increase the coupling piezoelectric mutual energy \({U}_{m}\) for higher-order modes. Then the \({k}_{t}^{2}\) can be enhanced since the \({U}_{m}\) is proportional to the \({k}_{t}^{2}\) 25. The coupling piezoelectric mutual energy equation is an integral formula: \({U}_{m}=1/4\,{\int }_{V}({TdE}+{EdT}){dV}\), where the integral domain \(V\) is the volume of the piezoelectric Al0.75Sc0.25N layer, \(T\) is the stress tensor, \(d\) is the piezoelectric (strain) coefficient matrix, and \(E\) is the electric field vector25. For S-BAR, neither \(d\) nor \(E\) is a function of the integral domain \(V\) and can be seen as constants, only \(T\) has a distribution along the \(z\) direction. The integral of stress \(T\) in Al0.75Sc0.25N layer plays a crucial role of \({U}_{m}\). The simulated stress \(T\) distributions based on finite element analysis (FEA) of S-BAR at S1 and A2 modes with different \(\alpha\) are illustrated in Fig. 2b. Ignoring the sudden change at the interface of the material stack, the stress distribution of S-BAR satisfies the sinusoidal form, with a period of \(0.5n\), where \(n\) is the order of the resonant mode. When \(\alpha\) is equal to 1, the distribution of half-period stress makes the \({U}_{m}\) of the resonator working in the S1 mode reach the maximum value. At the same time, the distribution of one-period stress makes the \({U}_{m}\) of the A2 mode almost 0. As \(\alpha\) gradually decreases, the \({U}_{m}\) of the S1 mode will become smaller due to the smaller integral domain in Fig. 2b, but the \({U}_{m}\) of the A2 mode will increase and reach a peak at around \(\alpha =0.31\), and then decrease. When the \(\alpha\) decreases, the stress zero point of A2 mode moves from the Al0.75Sc0.25N layer to the interface between the Al0.75Sc0.25N and silicon, which makes the integrated \({U}_{m}\) increase and reach the maximum value, thus producing the maximum \({k}_{t}^{2}\). Figure 2c verifies this conclusion using eigenmode analysis. The A2 mode of Al0.75Sc0.25N S-BAR can be excited and reaches the maximum simulated \({k}_{t}^{2}\) of 9.69% at \(\alpha =0.31\). Based on Fig. 2c, four S-BAR wafers with different \(\alpha\) are fabricated in this work for demonstration.

Fabrication process

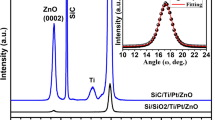

The fabrication process flow chart is shown in Fig. 3. First, a 4-inch intrinsic (100) silicon wafer is photolithographically processed using an ASML PAS5000 Stepper. The photolithography pattern is a defined-boundary rectangular array of circular holes with a diameter of 600 nm and a spacing of 500 nm. Then, the wafer is etched by ICP-DRIE. The etching depth of a 600 nm-diameter hole is around 5 μm. The second step is the rapid annealing at 1150 °C for 100 s in Argon at one atmosphere (1 atm) of pressure. The hole array structure on the surface of the silicon wafer will gradually evolve into a sealed cavity with a suspended crystalline silicon membrane. The principle of sealed cavity formation is the surface diffusion of silicon atoms driven by surface tension. At high temperatures, surface atoms migrate in ways that reduce the local chemical potential27,28. Diffusion of silicon atoms occurs at around 1000 °C, without reaching its solid melting point29. The cavity’s thickness and depth and the silicon membrane’s thickness are determined by the diameter, spacing, and depth of the DRIE etched silicon holes. The equation of the membrane’s profile is a fourth-order equation without an analytical solution28. It is also challenging to obtain numerical simulation solutions30. Our experimental results show that by keeping the etching depth of holes constant, the thickness of the silicon membrane is inversely proportional to the diameter of the holes and directly proportional to the spacing of the wells. An array of holes with a 500-nm diameter and 600-nm spacing will produce a 1.2-μm-thick silicon membrane with holes etched to a depth of 5 μm.

The third step is to achieve surface smoothing through wet oxidation and adjust the thickness of the silicon membrane to the designed value. As is shown in Fig. 4a, c, e, AFM measurement results show that the RMS roughness of the suspended membrane manufactured after annealing is 13.1 nm, and the RMS of the un-patterned region also reaches 3 nm. The rough surface is attributed to the diffusion length of adatoms being smaller than the spacing between adjacent discontinuous interfaces before diffusion occurs, and the nucleation of vacancy islands will occur during the diffusion of silicon atoms31. To flatten the membrane on the SSC, additional annealing at 1020 °C in a vacuum chamber for 5630 min is investigated, but this process is very time-consuming23. Similarly, annealing at 1000 °C in hydrogen can also achieve a very flat silicon surface, but the smoothing is aimed at the trench structure rather than the SSC22. Surface unevenness significantly affects the quality of subsequently deposited metals and piezoelectric materials, thereby degrading device performance. To address this issue, this study proposed a novel wet oxidation method to smooth the surface of migrated Si film to an RMS roughness of 1.5 nm within two cycles (262 min). The oxidation furnace was set at 1050 °C and 1 atm of pressure. Due to the high temperature of the oxidation process, the diffusion rate of silicon atoms is high29. The migration of silicon atoms will eventually form a flat surface after a certain time. Moreover, this solution could kill two birds with one stone. As oxidation proceeds, silicon is consumed, and the thickness of the silicon membrane can be reduced for higher-frequency applications. The thickness ratio of consumed silicon and formed silicon dioxide is 0.44 to 132, and an oxide layer of 0.5 μm requires 131 min of oxidation time under experiments in our clean room. For example, a silicon membrane with an initial thickness of 1200 nm can be controlled to a thickness of about 1000 nm after a 131-min oxidation cycle (200 nm of silicon is oxidized). Therefore, the oxidation time can control the thickness of the remaining silicon membrane for different requirements. More details of the wet oxidation process of S-BAR can be found in the Supplementary Information. Figure 4b, d, e shows the AFM results of the same SSC wafer after wet oxidation and oxide removal. The RMS inside cavity area decreases from 13.1 to 1.5 nm, and the RMS outside cavity area decreases from 3.6 to 0.2 nm, respectively. This demonstrates the feasibility of the proposed wet oxidation surface smoothing method.

a, b Three-dimensional (3-D) laser micrographs of an oval-shaped sealed silicon cavity before and after surface smoothing. c, d AFM images with root mean square (RMS) of film surface inside the cavity region before and after surface smoothing. e, f AFM images with RMS of surface outside of the cavity region before and after surface smoothing

The wet oxidation process can also be used for regional thinning of the suspended silicon membrane. Based on the local oxidation of silicon (LOCOS) process, regional thinning can be realized by the patterned silicon nitride hard mask. Oxygen and water move very slowly in nitride. Therefore, when silicon nitride patterns are formed on silicon, the nitride film serves as an effective oxidation mask, preventing oxidants from reaching the silicon surface covered by the nitride. During the silicon oxidation, the thin layer on top of the nitride film is also converted to silicon dioxide. The thickness of the nitride mask should be greater than the thickness consumed in all oxidation cycles. At moderate pressures (1–8 atmospheres), the consumption rate of the nitride mask is about 4% of the silicon oxidation rate, so a thin nitride layer (<100 nm) is sufficient for masking33. Isotropic silicon oxidation causes a “Bird’s Beak” phenomenon at the oxidation boundary. A smooth boundary can be formed from the non-oxidized area to the oxidized area, which is conducive to the adequate coverage of the metal electrode at the bottom of the S-BAR. The profile of this boundary can be controlled by the thickness of the nitride mask and the thickness of the generated silicon oxide34.

Hence, different suspended silicon membrane thicknesses can be achieved on the same wafer. The process flow should be as follows: after forming the cavity and performing the oxidation smoothing treatment on the wafer, a patterned silicon nitride is used as a mask, then an oxidation treatment is performed, and finally, buffered oxide etchant (BOE) can be used to remove the oxide layer and nitride layer.

In step four, the oxide layer is removed by wet etching using BOE. Then, a Pt bottom electrode with a thickness of 77 nm is evaporated on the wafer, followed by the lift-off process. In step six, Al0.75Sc0.25N is sputtered on the wafer. The probe holes are opened by etching Al0.75Sc0.25N with 86% phosphoric acid at 80 °C. In the last step, an Al top electrode with a thickness of 100 nm is deposited on the wafer and patterned. Finally, four 4-inch wafers are fabricated, one of which is not smoothed (Wafer-1), two are smoothed one round (Wafer-2 and Wafer-3), and the remaining one is smoothed two rounds (Wafer-4). The suspended silicon membrane thicknesses of the four wafers are ~1200, 1000, 1000, and 900 nm, respectively. There are three purposes for processing these four wafers. Firstly, experimental data is needed to verify that S-BAR can control the piezoelectric coupling (\({k}_{t}^{2}\)), as shown in Fig. 2c. Notably, the bandwidth of the acoustic filter increases with the increase of the \({k}_{t}^{2}.\)25 Secondly, it is necessary to experimentally evaluate the impact of the surface smoothing method on the performance of S-BAR, especially the quality factor (Q). The insertion loss of the acoustic filter decreases with the increase of the Q25. Finally, the performance of the designed S-BAR working in different frequency ranges needs to be explored. Different thickness designs correspond to different operating frequencies. Therefore, the research on the S-BAR of these four wafers is directly related to the frequency, bandwidth, and insertion loss of the S-BAR filter in practical RF wireless communication scenarios.

Figure 5 shows the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the fabricated wafer after different steps. The holes array is formed after ICP-DRIE with a freely defined boundary (e.g., ellipse, pentagon) shown in Fig. 5a. After rapid annealing, an around 0.8 μm-high sealed cavity with a 1.2 μm-thick suspended membrane is achieved shown in Fig. 5b. A 600 nm high and 1 μm wide step-like transition boundary is formed at the edge of the holes array. The top surface of the cavity is rough after annealing. The fabricated S-BAR device overview and zoomed-in image are shown in Fig. 5c, d. Benefiting from effective smoothing, a flat surface can be observed on the top of the device region. The die photo in Fig. 5e shows that the devices’ cavity area has good uniformity and high yield. The shapes of the cavities can be freely defined and fabricated as any pattern (e.g., ellipse, polygon). Figure 5f shows a fabricated 4-inch wafer with a \(5\times 5\) array die distribution. Except for the dies at the four corners, the remaining 21 dies are available, which shows the stability of the fabrication.

a SEM image of DRIE holes before rapid annealing. b SEM image of cross-section view of sealed cavity after rapid annealing with rough surface. c SEM image of 45° top view of fabricated S-BAR. d zoomed-in image of the sealed cavity region of S-BAR with a smooth surface. e Die micrograph of the fabricated wafer. f A fabricated S-BAR wafer

Measurement results

The fabricated S-BARs are characterized by a vector network analyzer in dry air at room temperature. The measured admittance responses of Deveice-1 to Deveice-4 of the same layout (Fig. 5c) from four different wafers with their modified Butterworth-Van Dyke (MBVD) modeled fitting curves are shown in Fig. 6a–d. Wafer-1 has not been smoothed, and its silicon membrane thickness is around the initial 1200 nm. The target A2 mode of Device-1 fabricated on it has a \({k}_{t}^{2}\) of 9.02% at a resonance frequency of 4.23 GHz. Since its rough surface affects the quality of metal and Al0.75Sc0.25N, its 3-dB \({Q}_{S}\) and \({Q}_{P}\) are 81 and 61, respectively. Device-2 and -3 have the same silicon thickness but different Al0.75Sc0.25N thicknesses (420 and 540 nm). Their measured admittance responses show the target A2 mode working at 5.15 and 4.48 GHz with \({k}_{t}^{2}\) of 9.35% and 9.53% respectively. After smoothing one round, the \(Q\) of Device-2 and Device-3 are larger than Device-1, reaching \({Q}_{S}\) and \({Q}_{P}\) of 106, 116, and 89, 110. Wafer-4 has been smoothed after two rounds. Device-4 on Wafer-4 achieves a \({Q}_{S}\) of 363 at 3.81 GHz and a \({Q}_{P}\) of 149 at 3.90 GHz. Due to design considerations, the thicker Al0.75Sc0.25N makes its \(\alpha =0.51\), which brings a \({k}_{t}^{2}\) of 4.94%. The \({k}_{t}^{2}\) of four devices are plotted with a theoretically predicted curve in Fig. 2c. The theoretical design is consistent with the experimental results. The performance summary of measured S-BARs is shown in Fig. 6e. In addition, the measured admittance responses are also verified by simulation (in Figs. S3 and S4). Fig. S5 shows the MBVD fitting circuits of the four measured S-BARs with a table of critical parameters. Compared with the unsmoothed Wafer-1, the \({R}_{0}\) and \({R}_{S}\) of Wafer-2 to Wafer-4 are smaller, which indicates that the deposited metal electrode on the smoothed wafers has better quality and sputtered Al0.75Sc0.25N has smaller dielectric loss. This is beneficial to improving the \(Q\) of the fabricated S-BARs. In Fig. 6f, the \(Q\) distribution box plot of measured S-BARs on four wafers also demonstrates that the \(Q\) of the devices are increased by the smoothing process. After two rounds of smoothing, the measured maximum \(Q\) of S-BAR increased by around 400% (from 97 to 439). It is believed that the performance of S-BAR can be further improved by optimized thickness design (\({k}_{t}^{2}\)) and smoothing process (\(Q\)) in the future.

The TCF of the S-BAR is measured in a vacuum cryogenic probe station shown in Fig. S5. As is shown in Fig. 7, the TCF of Al0.75Sc0.25N S-BAR is −11.44 ppm/K from 113 to 473 K, which is much larger than the measured TCF (−30 ppm/K) of Al0.75Sc0.25N FBAR24. The temperature compensation effect is attributed to the migrated silicon membrane, and its contribution to composite FBAR has been experimentally validated. Al0.7Sc0.3N/Si composite FBAR can achieve temperature compensation of TCF from −38.4 to −16.9 ppm/K35, and the possible mechanism involves stress-induced temperature compensation. The stress compensation effect has been employed to achieve a TCF of +0.8 ppm/K for multilayer FBAR36. In this work, the silicon membrane beneath the Al0.75Sc0.25N exhibits a tensile stress distribution (in Fig. S6) prior to Al0.75Sc0.25N sputtering, which contributes to the TCF of −11.44 ppm/K for S-BAR. Further details regarding this mechanism are provided in the Supplementary Information. The measured \(Q\) is enhanced by both increasing and decreasing temperature. This may be due to the lower dielectric losses at the low temperatures and lower mechanical losses contributed by high temperatures in the stacked structure.

Conclusion

In this work, we proposed a new microacoustic platform for highly integrated RF microacoustic devices with a smooth suspended sealed membrane, controllable membrane thickness, high-density freely definable cavity, self-formed acoustic wave confinement steps, enhanced coupling, and stable TCF. A S-BAR based on Al0.75Sc0.25N is proposed and fabricated on this platform for demonstration. The \({k}_{t}^{2}\) of fabricated A2 mode S-BAR can be enhanced from 0 to over 9% by tuning the stress distribution. The presented wet oxidation smoothing method for SSC wafer can effectively help improve the \(Q\) of the presented S-BAR (increase by around 400%). The measurement results of S-BAR and other published works are compared in Table 1. With the SSC platform’s help, the fabricated S-BAR’s TCF is higher than the state-of-the-art FBAR’s. However, the low \(Q\) value and spurious mode are the issues that need to be addressed. In addition to smoothing the suspended silicon membrane, wet oxidation can also be used to simultaneously thin the thickness of the silicon membrane. Nevertheless, the thickness of the silicon membrane needs to be adjusted to be thinner to cope with higher-frequency applications. Experimental results verify the feasibility, innovation, and advancement of the proposed S-BAR, which has the potential to replace the current FBAR filter for the high Table 1 Comparison with other published results ly integrated front-end module (FEM) of the 5G/6G RF communication system. Higher integration is the development trend of FEMs for wireless communication system. High-integration FEM requires devices to have precisely controllable boundaries. Compared with the existing sacrificial layer process for definable boudaries37, the SSC platform has the advantage of low cost. The robust mechanical structure of the S-BAR with a sealed cavity can support the subsequent on-chip integration process, and has the advantage of low process complexity compared with the FEM integrated bonding process15. The SSC platform supports contact-type processes, which makes it less sensitive to the packaging process than the existing FBAR suspended film structure, which helps to further reduce packaging costs. In addition to S-BAR for FEM, the SSC platform is compatible with CMOS processes and can realize compact, integrated chips, such as wearable or implantable microacoustic sensors or actuators. In conclusion, this paper provides novel insights into the design and fabrication of an SSC microacoustic platform, which has great potential for development in ultrasound and microwave applications.

Data availability

All data are fully available without restriction.

References

Hassanien, A. E. et al. Efficient and wideband acousto-optic modulation on thin-film lithium niobate for microwave-to-photonic conversion. Photonics Res. 9, 1182–1190 (2021).

Ghosh, S. & Piazza, G. Laterally vibrating resonator based elasto-optic modulation in aluminum nitride. APL Photonics 1, 036101 (2016).

Tadesse, S. A. & Li, M. Sub-optical wavelength acoustic wave modulation of integrated photonic resonators at microwave frequencies. Nat. Commun. 5, 5402 (2014).

Kuznetsov, A. S., Biermann, K. & Santos, P. V. Acceleration-induced spectral beats in strongly driven harmonic oscillators. Nat. Commun. 15, 5343 (2024).

Chu, Y. et al. Quantum acoustics with superconducting qubits. Science 358, 199–202 (2017).

Noguchi, A., Yamazaki, R., Tabuchi, Y. & Nakamura, Y. Single-photon quantum regime of artificial radiation pressure on a surface acoustic wave resonator. Nat. Commun. 11, 1183 (2020).

Cai, J. et al. Beyond fundamental resonance mode: high-order multi-band ALN PMUT for in vivo photoacoustic imaging. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 116 (2022).

Lu, Y. & Horsley, D. A. Modeling, Fabrication, and Characterization of Piezoelectric Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer Arrays Based on Cavity SOI Wafers. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 24, 1142–1149 (2015).

Lu, Y. et al. Ultrasonic fingerprint sensor using a piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer array integrated with complementary metal oxide semiconductor electronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 263503 (2015).

Hakim, F., Rudawski, N. G., Tharpe, T. & Tabrizian, R. A ferroelectric-gate fin microwave acoustic spectral processor. Nat. Electron. 7, 147–156 (2024).

Yang, Y., Lu, R. & Gong, S. Scaling acoustic filters towards 5G. In Proc. 2018 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting 39.6.1–39.6.4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2018.8614699 (2018).

Xie, J. et al. Sub-terahertz electromechanics. Nat. Electron. 6, 301–306 (2023).

Lu, Y., Heidari, A. & Horsley, D. A. A high fill-factor annular array of high frequency piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 24, 904–913 (2015).

Wang, J., Zheng, Z., Chan, J. & Yeow, J. T. W. Capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducers for intravascular ultrasound imaging. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 6, 1–13 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. 3D Monolithic integration of ScAlN-based GHz MEMS acoustic filters on 200mm RFSOI wafer. In Proc. 2022 International Electron Devices Meeting 16.2.1–16.2.4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM45625.2022.10019557 (2022).

Park, M., Wang, J. & Ansari, A. High-overtone thin film ferroelectric AlScN-on-silicon composite resonators. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 42, 911–914 (2021).

Prasad, M., Sahula, V. & Khanna, V. K. Design and fabrication of Si-diaphragm, ZnO piezoelectric film-based MEMS acoustic sensor using SOI wafers. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 26, 233–241 (2013).

Wang, J. et al. A film bulk acoustic resonator based on ferroelectric aluminum scandium nitride films. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 29, 741–747 (2020).

Lu, J., Zhang, L., Takagi, H. & Maeda, R. A novel cavity-first process for flexible fabrication of MEMS on silicon on insulator (SOI) wafer. Microelectron. Eng. 119, 28–31 (2014).

Liu, C. et al. A Sc 0.2 Al 0.8 N-based 14 GHz film bulk acoustic resonator with over 8% coupling coefficient and over 400 quality factor for Ku-band applications. In Proc. 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IUS51837.2023.10306371 (IEEE, 2023).

Ruby, R. C., Bradley, P., Oshmyansky, Y., Chien, A. & Larson, J. D. Thin film bulk wave acoustic resonators (FBAR) for wireless applications. In Proc. 2001 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. Proceedings. An International Symposium (Cat. No.01CH37263) Vol. 1, 813–821 (2001).

Hiruta, R., Kuribayashi, H., Shimizu, R., Sudoh, K. & Iwasaki, H. Flattening of micro-structured Si surfaces by hydrogen annealing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 252, 5279–5283 (2006).

Sudoh, K., Nakamura, J., Naito, M., Higuchi, K. & Maenaka, K. Formation of silicon-on-nothing structures with extremely flat surfaces. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 075601 (2013).

Suzuki, M. & Yanagitani, T. 2P3-3 Temperature coefficient of elastic and GHz piezoelectric properties in ScAlN films(Poster Session). (Institute for Ultrasonic Elecronics, 2013) https://doi.org/10.24492/use.34.0_253.

Hashimoto, K.-Y. RF Bulk Acoustic Wave Filters for Communications (Artech House, 2009).

Xu, J. et al. Sealed-cavity bulk acoustic resonator for subsequent fabrication and higher order mode. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 33, 3–5 (2024).

Sato, T., Aoki, N., Mizushima, I. & Tsunashima, Y. A new substrate engineering for the formation of empty space in silicon (ESS) induced by silicon surface migration. In Proc. International Electron Devices Meeting 1999. Technical Digest (Cat. No.99CH36318) 517–520. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.1999.824206 (1999).

Mullins, W. W. Theory of thermal grooving. J. Appl. Phys. 28, 333–339 (1957).

Shimizu, R., Kuribayashi, H., Hiruta, R., Sudoh, K. & Iwasaki, H. Mechanism and control technology of trench corner rounding by hydrogen annealing for highly reliable trench MOSFET. In Proc. 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Power Semiconductor Devices and IC’s 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISPSD.2006.1666084 (2006).

Smereka, P. Semi-implicit level set methods for curvature and surface diffusion motion. J. Sci. Comput. 19, 439–456 (2003).

Finnie, P. & Homma, Y. Nucleation and step flow on ultraflat silicon. Phys. Rev. B 62, 8313–8317 (2000).

Deal, B. E. & Grove, A. S. General relationship for the thermal oxidation of silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 36, 3770–3778 (1965).

El-Kareh, B. Fundamentals of Semiconductor Processing Technology https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-2209-6 (Springer US, 1995).

Desiatov, B., Goykhman, I. & Levy, U. Demonstration of submicron square-like silicon waveguide using optimized LOCOS process. Opt. Express 18, 18592–18597 (2010).

Wang, J., Park, M. & Ansari, A. Thermal characterization of ferroelectric aluminum scandium nitride acoustic resonators. In Proc. 2021 IEEE 34th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems 214–217. https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMS51782.2021.9375203 (2021).

Liu, Y., Sun, K., Ma, J., Yu, Z. & Lan, Z. Design and fabrication of temperature-compensated film bulk acoustic resonator filter based on the stress compensation effect. Coatings 12, 1126 (2022).

Zou, Y. et al. Aluminum scandium nitride thin-film bulk acoustic resonators for 5G wideband applications. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 1–7 (2022).

Peng, W., Nam, S., Wang, D., Mi, Z. & Mortazawi, A. A 56 GHz trilayer AlN/ScAlN/AlN periodically poled FBAR. In Proc. 2024 IEEE/MTT-S International Microwave Symposium 150–153. https://doi.org/10.1109/IMS40175.2024.10600386 (2024).

Izhar et al. A K-band bulk acoustic wave resonator using periodically poled Al0.72Sc0.28N. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 44, 1196–1199 (2023).

Kochhar, A. et al. X-band bulk acoustic wave resonator (XBAW) using periodically polarized piezoelectric films (P3F). In Proc. 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IUS51837.2023.10306825 (2023).

Vetury, R., Hodge, M. D. & Shealy, J. B. High power, wideband single crystal XBAW technology for sub-6 GHz micro RF filter applications. In Proc. 2018 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1109/ULTSYM.2018.8580045 (IEEE, 2018).

Yi, X. et al. High-quality film bulk acoustic resonators fabricated on AlN films grown by a new two-step method. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 43, 942–945 (2022).

Bousquet, M. et al. Single-mode high frequency LiNbO3 film bulk acoustic resonator. In Proc. 2019 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium 84–87. https://doi.org/10.1109/ULTSYM.2019.8925617 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council 26202122, in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China 62304193, in part by the Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission MHP/007/22, and in part by the Hong Kong RGC Strategic Topics Grant STG3/E-602/23N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.X. carried out calculations, FEA simulation, fabrication, measurement, data analysis, wrote the paper, and made the modifications to the manuscript. Z.R., F.Q., and J.Z. participated in fabrication, characterization, as well as data analysis. Y.Y. conceived the idea, supervised the whole work, wrote the paper, and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, J., Ren, Z., Qian, F. et al. A wafer-level sealed silicon cavity microacoustic platform for radio frequency integration. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 107 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00958-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00958-8