Abstract

Gastric pain has limited treatment options and the mechanisms within the central circuitry remain largely unclear. This study investigates the central circuitry in gastric pain induced by noxious gastric distension (GD) in mice. Here, we identified that the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) serves as the first-level center of gastric pain, primarily via the vagus nerve. The prelimbic cortex (PL) is engaged in the perception of gastric pain. The lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPB) and the paraventricular thalamic nucleus (PVT) are crucial regions for synaptic transmission from the NTS to the PL. The glutamatergic tetra-synaptic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL circuitry is necessary and sufficient for the processing of gastric pain. Overall, our finding reveals a glutamatergic tetra-synaptic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL circuitry that transmits gastric nociceptive signaling by the vagus nerve in mice. It provides an insight into the gastric pain ascending pathway and offers potential therapeutic targets for relieving visceral pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric pain is a highly prevalent gastrointestinal symptom with a complex etiology. Functional dyspepsia, gastric ulcers, gastric cancer, and gastroparesis are associated with painful sensations in the stomach1,2,3. Patients with gastric pain have impaired food intake, leading to weight loss and low quality of life4,5. Traditionally, it has been suggested that the occurrence of gastric pain is associated with abnormal gastric dynamics, visceral hypersensitivity, and psychosomatic factors, but the specific pathogenesis remains unclear, and there is a lack of specific therapies in the clinic. In recent years, research on visceral pain has made significant strides6,7,8,9. However, studies on gastric pain predominantly focus on the peripheral nervous system, with limited investigation into central nervous system mechanisms. There is a pressing clinical need for the development of novel, specific therapeutic approaches targeting gastric pain. Early studies have provided preliminary mappings of brain nuclei anatomically connected to the stomach10,11. However, which nuclei can respond to gastric pain stimuli and how they form neural circuits to transmit gastric pain signals remain unclear.

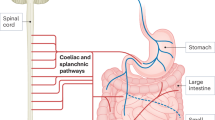

Vagal and spinal afferents are the two major primary afferents that convey sensory information with different natures from the upper gastrointestinal tract to the central nervous system12. It has been commonly assumed that vagal afferents convey predominantly physiological information while spinal afferents process nociception12. Although existing electrophysiological evidence reveals that vagal afferents respond to gastric distension (GD) in the noxious range (up to 60 mmHg)13, there is no conclusive evidence so far to show that vagal afferents include nociceptors that initiate pain due to the lack of high-threshold mechanosensitive afferent fibers (putative nociceptors). Despite the lack of evidence as a nociceptor, a considerable body of evidence indicates vagal afferents as pain modulators. For example, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy enhances visceromotor responses to colorectum distension14, a region beyond the innervation of vagal afferents. Sensitization of vagal afferents causes changes in the amygdala, resulting in suppression of nociceptive signals conveyed by gastric spinal afferents via the descending pain modulatory pathway15. In addition, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) reduces different forms of somatic pain16,17,18 or visceral pain14,19, although some other studies report no effect or dual effect20,21. The nucleus tractus solitaries (NTS) is a principal nucleus that receives afferent projections from the vagus nerve, and is responsible for relaying information from various organs within the body22,23. Studies have reported that noxious GD induces significantly more c-Fos expression in the NTS than in the thoracic spinal cord24. This suggests that the vagus nerve may play a more pivotal role in the transmission of gastric pain. However, the entire ascending neural circuit of vagal afferent-conveyed nociceptive signaling has not been mapped out in the brain, particularly at the cortex level.

As such, this study aims to investigate the ascending neural circuits that transmit gastric pain signals from the stomach to the cortex, and whether via the vagal afferents. This would be achieved by combining a variety of approaches, including virus-based tracing and mapping, in vivo neuronal activity recording, and functional manipulation of neuronal activities by optogenetics and chemogenetics. Moreover, this study would enrich the mapping of the stomach–brain axis, help in understanding the ascending neural circuits mediating gastric pain, and provide therapeutic strategies for the clinical management of gastric pain.

Results

The vagus-nucleus tractus solitarius pathway initiates the transmission of gastric pain signals

Gastric pain was induced by performing gastric balloon implantation surgery on 6-week-old mice. Postoperatively, no abnormalities were observed in mouse body weight, food intake, motor skills, or emotional states (Fig. S1A–E). The acromiotrapezius muscle electromyographic (EMG) recordings were conducted to assess the gastric pain behavior3,25,26,27. A behavioral test was conducted one week after the surgical recovery. The increase in the area under the curve (AUC) was positively correlated with the increase in distention pressure both in male (Fig. S1F, G, R2 = 0.8217, P < 0.0001, n = 8 mice) and female mice (Fig. S1H–I, R2 = 0.9074, P < 0.0001, n = 8 mice). To explore brain nuclei involved in the gastric pain, whole-brain c-Fos staining was employed after a noxious GD at 60 mmHg (Fig. 1A). The expression levels of c-Fos in the nuclei of the NTS, lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPB), paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT), and prelimbic cortex (PL) were the highest regions both in male and female mice (Figs. 1B, C and S2, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 3 male and 3 female mice). Since there are no significant differences in EMG activities and c-Fos expression levels between male and female mice, our study mainly focused on male mice unless otherwise stated.

A Schematic representation of GD and c-Fos staining in mice. B Heatmap illustrating the changes of c-Fos expression in the NTS, LPB, PVT, PL, DRN, LC, DMH, LH, PVH, and the BNST following GD stimulation (n = 3 mice). C Representative images of c-Fos expression in the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL in male and female mice. D Schematic diagram of gastric wall injection of HSV-EGFP. E From left to right, representative images depict neurons labeled with EGFP in the NTS, NG, and SC following HSV-EGFP injection into the gastric wall. F Schematic diagram of mouse gastric wall injection with HSV-EGFP with SDx and T5x, respectively procedures (left). After SDx and T5x, representative images of the NTS expressing HSV-EGFP (right). G Schematic diagram of GD with SDx and T5x, respectively procedures (left). After SDx and T5x, representative images and statistical analysis of c-Fos expression in the NTS under the same distension pressure (middle and right, n = 3 mice, P = 0.0014). GD gastric distension, EMG electromyographic, AUC the area under the curve, NTS the solitary nucleus, LPB lateral parabrachial nucleus, PVT paraventricular thalamic nucleus, PL prelimbic cortex, DRN dorsal nucleus of the middle suture, LC locus coeruleus, DMH dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus, LH lateral hypothalamus, PVH paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, BNST bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, NG nodose ganglion, SC spinal cord, SDx subdiaphragmatic vagotomy, T5x thoracic spinal cord transection at the T5 level. Scale bar = 100 μm in all Fig. Significance was assessed by two-way repeated-measure ANOVA in (B) and two-sided Student’s t-test in (G). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments and the data shown were from one representative experiment in (E, F).

The NTS serves as a prominent hub for visceral sensory transmission, however, its influence on gastric pain signaling remains uncertain28,29,30,31,32. Therefore, an anterogradely trans-polysynaptic type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) H129 strain expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (HSV-EGFP) was injected into the gastric wall (Fig. 1D). Subsequently, we observed neurons labeled with EGFP in the gastric wall post-viral injection, confirming a successful infection by HSV (Fig. S3A). Moreover, EGFP-positive neuronal expression was observed in both the nodose ganglion (NG) and the spinal cord (SC). The brain regions with the highest HSV expression included the NTS, LPB, PVT, PL, dorsal nucleus of the middle suture (DRN), paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (DMH), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and lateral hypothalamus (LH) (Fig. 1E and S3B). The NTS receives conduction from both the vagus nerve and the spinal nerve. To investigate whether the NTS gastric-origin signals are mainly transmitted via the vagus nerve or the spinal nerve, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (SDx) or thoracic spinal cord transection at the T5 level (T5x) was performed in mice. The EGFP expression in the NTS was nearly absent in SDx group of mice, while a substantial amount of EGFP signals were still observed in T5x group of mice (Fig. 1F). Additionally, there was almost no expression of c-Fos in the NTS after SDx whereas mice continued to exhibit abundant c-Fos expression in the NTS after T5x (Fig. 1G, **P < 0.01, t-test, n = 3 mice). These preliminary data suggest that the NTS responds to gastric pain stimuli via the vagus nerve, laying the foundation for identifying the ascending pathways of gastric pain signals.

Identification of a glutamatergic tetra-synaptic connectivity pathway from the NTS to the PL

Based on HSV expression and c-Fos staining, we first determined whether the synaptic transmission signals conveyed from the NTS to the PL represent a direct or indirect projection. The anterograde tracing virus AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP was injected into the NTS. There was no neural terminal expression observed in the PL (Fig. 2A). To further validate this result, retrograde tracing virus AAV2/Retro-mCherry was injected into the PL. There was not mCherry-positive neuron in the NTS (Fig. 2B). These data indicated no direct projection from the NTS to the PL. Then we determined how many synapses existed from the NTS to the PL. Injection of the anterograde tracing virus AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP into the NTS led to a significant expression of EGFP+ fibers in the LPB and the PVT (Fig. 2C). Additionally, injection of the retrograde tracing virus AAV2/Retro-mCherry into the PL led to a significant number of mCherry-positive neurons in the PVT but not in the LPB (Fig. 2D).

A Schematic of the anterograde virus tracing strategy. Typical images of virus injection sites within the NTS and expression in the PL (n = 3 mice). B Schematic of the retrograde virus tracing strategy. Typical images of virus injection sites within the PL and expression in the NTS (n = 3 mice). C Typical images of AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP injection sites within the NTS and viral expression in the LPB and the PVT (n = 3 mice). D Typical images of AAV2/Retro-mCherry injection sites within the PL and viral expression in the LPB and the PVT (n = 3 mice). E, F Identification of the NTS-LPB-PVT neural circuit. E Schematic of the anterograde trans-synaptic tracing (left). Representative images of viral expression in the LPB (middle). Representative images and quantification analysis showing the EGFP-labeled neurons in the LPB traced from the NTS colocalized with Glutamate and GABA antibody (right, n = 6 mice). F Image of the NTS-innervated LPB neurons and their axonal terminals in the PVT. G Typical images of AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP injection sites within the LPB and viral expression in the PVT (n = 3 mice). H Typical images of AAV2/Retro-mCherry injection sites within the PVT and viral expression in the LPB (n = 3 mice). I, J Identification of the LPB-PVT-PL neural circuit. I Schematic of the anterograde trans-synaptic tracing (left). Representative images of viral expression in the PVT (middle). Representative images and quantification analysis showing the EGFP-labeled neurons in the PVT traced from the LPB colocalized with glutamate and GABA antibody (right, n = 6 mice). J Image of the LPB-innervated PVT neurons and their axonal terminals in the PL. K Typical images of AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP injection sites within the PVT and viral expression in the PL (n = 5 mice). L Left: schematic of the anterograde trans-synaptic tracing. Middle: representative images of viral expression in the PL. Right: representative images and quantification analysis showing the EGFP-labeled neurons in the PL traced from the LPB colocalized with glutamate and GABA antibody (n = 6 mice). Scale bar = 50 μm in all figures.

We proceed with the step-by-step identification of the neural circuitry. The NTS-LPB neural pathway was initially identified by employing an anterograde monosynaptic tracking strategy. After injection of a scAAV2/1-hsyn-Cre virus into the NTS and an AAV2/9-DIO-Ypet-mGFP virus into the LPB, we observed EGFP+ neurons in the LPB, which predominantly exhibited positive staining for glutamatergic neurons, as opposed to GABAergic neurons (Fig. 2E). Having identified the NTS-LPB synapse, we looked for the targets downstream of the LPB to complete the pathway. An exciting discovery was made that a dense labeling of mGFP-positive axonal terminals existed in the PVT (Fig. 2F). To further delineate this neural connectivity, anterograde tracing virus AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP was injected into the LPB, resulting in the observation of significant fiber terminals in the PVT (Fig. 2G). AAV2/Retro-mCherry was injected into the PVT, resulting in the observation of a significant number of neurons in the LPB (Fig. 2H). Collectively, these data indicate that neurons projecting from the NTS to the LPB exhibit anterograde projections to the PVT. Then, utilizing a dual-virus strategy involving scAAV2/1-hsyn-Cre and AAV2/9-DIO-Ypet-mGFP, injected separately into the LPB and the PVT, respectively, a significant abundance of mGFP-positive signals was observed in the PVT. The mGFP-positive neuronal markers exclusively represent glutamatergic neurons within this circuitry (Fig. 2I). Meanwhile, we observed robust expression of neuronal terminals in the PL (Fig. 2J). To further delineate this pathway, AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP was injected into the PVT, resulting in the observation of significant fiber terminals of neuronal in the PL (Fig. 2K). scAAV2/1-hsyn-Cre and AAV2/9-DIO-Ypet-mGFP injected into PVT and PL, respectively, an abundance of mGFP-positive signals indicating considerable expression of neurons were observed in the PL. The identification of neurons expressing mGFP revealed that the majority were glutamatergic neurons (Fig. 2L). To further determine the synaptic connections of the stomach to the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL, the expression of HSV-EGFP was observed at different time points. HSV expression in the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL exhibited a time-dependent pattern. At 3 days post-HSV injection, EGFP expression was observed only in the NTS and there is no expression detected in other brain regions. At 5 days post-HSV injection, EGFP expression was observed not only in the NTS but also in the LPB. However, the EGFP expression in the PVT and the PL remained minimal. At 7 days post-HSV injection, EGFP expression was extended to the PVT and the PL (Fig. S4A). These data suggested the presence of synaptic progression among these four brain regions, supporting a glutamatergic tetra-synaptic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL circuitry.

The NTS glutamatergic neurons play a crucial role in responding to gastric pain behaviors in mice

To further identify the neuronal types associated with gastric pain in the NTS, staining was performed using neuronal markers. Notably, the upsurge in c-Fos positive cells activated in the NTS following GD was primarily attributed to glutamatergic neurons other than GABAergic neurons (Fig. 3A, B). An in vivo fiber-optic calcium imaging recording experiments showed that the application of diverse pressure stimuli to the stomach resulted in calcium activity and triggered the activation of calcium fluorescence in the NTSGlu (Figs. 3C–E and S5A–C, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). Furthermore, to investigate whether the NTSGlu response to GD stimulation occurs via the vagus nerve or the spinal nerves, we employed fiber-optic calcium imaging recording coupled with SDx or T5x exploration. A notable decrease in NTSGlu calcium activity was observed when exposed to comparable gastric pressure stimuli compared to the pre-SDx state. Conversely, there was no significant change in NTSGlu calcium activity after T5x (Fig. 3F, G, ***P < 0.001, t-test, n = 6 mice). To explore the regulation of the NTSGlu in gastric pain responses, optogenetics was employed to manipulate the NTSGlu and an EMG recording was utilized to assess gastric pain. Light-sensitive proteins containing glutamatergic neuron promoters were injected into the NTS (Fig. 3H–J). The application of 589 nm yellow light to inhibit the NTSGlu led to a substantial reduction in gastric pain sensitivity (Fig. 3K, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). Using 473 nm blue light at a frequency of 10 Hz to activate the NTSGlu exacerbated gastric pain behavior (Fig. 3L). Furthermore, following SDx with blue light at the same time, there was a significant reduction in the gastric pain response (Fig. 3L, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). These data indicated the NTS glutamatergic neurons play a crucial role via the vagus nerve in the perception of gastric pain behavior in mice.

A Representative images of co-expressed c-Fos neurons (red), glutamatergic neurons (green), and DAPI (blue) (left) and the percentage of co-expression in the NTS (right, n = 6 slices from 3 mice). B Representative images of co-expressed c-Fos neurons (red), GABA neurons (green), and DAPI (blue) in the NTS (left). The percentage of co-expression in the NTS (right, n = 6 slices from 3 mice). C Schematic of AAV-vglut2-GCaMP6s injection and optic fiber implantation in the NTS (left). Expression of GCaMP6s in the NTS (right). D Heatmap and average Ca2+ transients of the NTSGlu under GD stimulation. E Averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the NTSGlu under GD stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0248 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0005 in 60 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 80 mmHg). F Heatmap of the NTSGlu pre and post-SDx in GD stimulation, respectively (left). Average Ca2+ transients of the NTSGlu under GD stimulation at 60 mmHg for Pre and SDx, respectively (middle). Averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the NTSGlu pre and post-SDx in GD stimulation (right, n = 6 mice, P = 0.0002). G Heatmap, average Ca2+ transients, and averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the NTSGlu pre and post-T5x in GD stimulation (n = 6 mice). H Experimental procedure of optogenetic manipulation of NTSGlu. I Schematic of the EMG recording setup, including the implantation of two electrodes in the acromiotrapezius muscle, and the insertion of a balloon into the stomach. EMG recordings were conducted one week after recovery. J Expression of virus in the NTS. K Representative EMG traces and the AUC statistics under eNpHR-stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0004 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg). L Representative EMG traces and SDx administration of the AUC statistics under ChR2-stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0237 in 40 mmHg vs light off, P = 0.0214 in 60 mmHg vs light off, P = 0.0001 in 80 mmHg vs light off). AM acromiotrapezius muscle. Scale bar = 100 μm in (A–C, and J), scale bar = 20 μm in zoomed image in (A, B). Significance was assessed by two-way repeated-measure ANOVA in (E, K, and L), and two-sided Student’s t-test in (F, G). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Similar results were obtained in six independent experiments and the data shown were from one representative experiment in (C, J).

The LPB and the PVT are crucial regions for synaptic transmission from the NTS to the PL

Next, the roles of the LPB and the PVT in responding to gastric pain signals were explored. To further identify the neuronal types associated with gastric pain in the LPB, staining was performed using neuronal markers. Notably, the upsurge in c-FOS positive cells activated in the LPB following GD stimulation was primarily attributed to glutamatergic neurons (Fig. S6A). An in vivo fiber-optic calcium imaging recording experiments showed that the application of diverse pressure stimuli to the stomach resulted in calcium activity and triggered the activation of calcium fluorescence in the LPBGlu (Figs. 4A–C and S6B, C, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). To explore the regulation of the LPBGlu in gastric pain responses, optogenetics was employed to manipulate the LPBGlu and an EMG recording was utilized to assess gastric pain. Light-sensitive proteins containing glutamatergic neuron promoters were injected into the LPB (Fig. 4D, E). Using 473 nm blue light at a frequency of 10 Hz to activate the LPBGlu exacerbated gastric pain behavior (Fig. 4F, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). The application of 589 nm yellow light to inhibit the LPBGlu led to a substantial reduction in gastric pain sensitivity (Fig. 4G, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice).

A Schematic of AAV-vglut2-GCaMP6s injection and optic fiber implantation in the LPB (left). Expression of GCaMP6s in the LPB (right). B Heatmap and average Ca2+ transients of the LPBGlu under GD stimulation. C Averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the LPBGlu pre and post-GD stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0407 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg). D Experimental procedure of optogenetic manipulation of LPBGlu (left). Schematics of the EMG recording setup (right). E Expression of virus in the LPB. F, G Representative EMG traces and the AUC statistics under ChR2-stimulation or eNpHR-stimulation (n = 6 mice; P = 0.0011 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg under ChR2-stimulation; P = 0.0021 in 60 mmHg, P = 0.0003 in 80 mmHg under eNpHR-stimulation). H Schematic of AAV-vglut2-GCaMP6s injection and optic fiber implantation in the PVT (left). Expression of GCaMP6s in the PVT (right). I Heatmap and average Ca2+ transients of the PVTGlu under GD stimulation. J Averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the PVTGlu (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0001 in 40 mmHg, 60 mmHg, and 80 mmHg). K Experimental procedure of optogenetic manipulation of PVTGlu (left). Schematics of the EMG recording setup (right). L Expression of virus in the PVT. M, N Representative EMG traces and the AUC statistics under ChR2-stimulation or eNpHR-stimulation (n = 6 mice; P = 0.0105 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0133 in 60 mmHg, P = 0.0003 in 80 mmHg under ChR2-stimulation; P = 0.0149 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg under eNpHR-stimulation). AM acromiotrapezius muscle. Scale bar = 100 μm in (A, E, H, and L), scale bar = 20 μm in zoomed image in (A, L). Significance was assessed by two-way repeated-measure ANOVA in (C, F, G, J, M, and N). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Similar results were obtained in six independent experiments and the data shown were from one representative experiment in (E, I).

Similarly, the types of neurons in the PVT activated by gastric pain stimuli were investigated. Notably, the upsurge in c-Fos-positive cells activated in the PVT following GD was primarily attributed to glutamatergic neurons (Fig. S7A). An in vivo fiber-optic calcium imaging recording experiments showed that the application of diverse pressure stimuli to the stomach resulted in calcium activity and triggered the activation of calcium fluorescence in the PVTGlu (Figs. 4H–J and S7B, C, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). To explore the regulation of the PVTGlu in gastric pain responses, optogenetics was employed to manipulate the PVTGlu, and an EMG recording was utilized to assess gastric pain (Fig. 4K, L). Using 473 nm blue light at a frequency of 10 Hz to activate the PVTGlu exacerbated gastric pain behavior (Fig. 4M, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). The application of 589 nm yellow light to inhibit the PVTGlu led to a substantial reduction in gastric pain sensitivity (Fig. 4N, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). These data indicated the LPBGlu and the PVTGlu play a crucial role in the perception of gastric pain behavior in mice.

The PL glutamatergic neurons perceive gastric pain signals

The majority of neurons activated by GD stimulation were glutamatergic neurons other than GABAergic neurons in the PL (Fig. 5A, B). Injection of AAV-vglut2-GCaMP6S in the PL combined with fiber photometry validated the activation of the PLGlu in response to GD stimuli of varying pressures (Figs. 5C–E and S8A–C, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). Similarly, utilizing optogenetics in conjunction with EMG recordings, it was observed that activation of the PLGlu increased the AUC of EMG and inhibition of the PLGlu reduced the AUC of EMG (Fig. 5F–I, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice), indicating the role of PLGlu in gastric pain. To investigate whether the gastric pain signal in the PL is conveyed through the vagus nerve, NTS, LPB, and PVT, a stepwise verification was conducted. A significant decrease in the PLGlu calcium activity in response to GD stimuli was observed after SDx, whereas there was no noticeable alteration in the PLGlu calcium activity after T5x (Fig. 5J, K, **P < 0.01, t-test, n = 6 mice). Activation of the AAV2/9-vglut2-hM4Di (Gi) in the NTS by clozapine N-oxide (CNO, 3.3 mg/kg) led to a significant decrease in c-Fos expression in the PL (Fig. 5L, *P < 0.05, t-test, n = 3 mice). Compared to the saline-injected group, the PLGlu calcium signals significantly decreased under equivalent pressure stimulation after CNO injection in the NTS (Fig. 5M, ***P < 0.001, t-test, n = 3 mice). Additionally, inhibition of the LPB neurons with CNO significantly reduced c-Fos expression (Fig. S9A, B, *P < 0.05, t-test, n = 3 mice) and glutamatergic neurons calcium signals (Fig. S9C, D, **P < 0.01, t-test, n = 6 mice) in the PL during GD stimulation compared with the saline group. Similarly, inhibition of the PVT neurons with CNO significantly also reduced c-Fos expression (Fig. S10A, B, ***P < 0.001, t-test, n = 3 mice) and glutamatergic neurons calcium signals (Fig. S10C, D, **P < 0.01, t-test, n = 6 mice) in the PL during GD stimulation compared with the saline group. These data suggest that the gastric pain signal travels through the vagus nerve to the NTS, LPB, and PVT and reaches the PLGlu to perceive gastric pain response.

A, B Representative images of co-expressed c-Fos (red), glutamatergic neurons or GABA neurons (green), and DAPI (blue) in the PL (left). The percentage of co-expression in the PL (right, n = 4 mice). C Schematic of AAV-vglut2-GCaMP6s injection and fiber implantation in the PL (left). Expression of GCaMP6s in the PL (right). D Heatmap and average Ca2+ transients of the PLGlu receiving GD stimulation. E Averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the PLGlu (right, n = 6 mice, P = 0.0001 in 40 mmHg, 60 mmHg, and 80 mmHg). F Experimental procedure of optogenetic manipulation of the PLGlu (left). Schematic of the EMG recording setup (right). G Representative images expression of virus in the PL. Similar results were obtained in six independent experiments and the data shown were from one representative experiment. H Representative EMG traces and statistical graph of EMG recordings AUC responses to GD under normal conditions or upon ChR2-stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0004 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg). I Representative EMG traces and statistical graph of EMG recordings AUC responses to GD under normal conditions or upon eNpHR-stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0235 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg). J Heatmap and average Ca2+ transients of the PLGlu in pre and post-receiving SDx in GD stimulation, respectively (left). Averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the PLGlu in pre and post-receiving SDx in GD stimulation (right, n = 6 mice, P = 0.0058). K Heatmap and average Ca2+ transients and averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the PLGlu in pre and post-receiving T5x in GD stimulation (n = 6 mice). L Schematic of AAV injection in the NTS (left). Decreased c-Fos expression in the PL after CNO injection compared with the saline group (middle). Statistical graph of c-Fos+ cells number (right, n = 3 mice, P = 0.0177). M Schematic of AAV injection in the NTS, AAV, and optic fiber implantation in the PL (left). Heatmap of the PLGlu in receiving saline or CNO in GD stimulation (middle) and averaged peak ΔF/F of calcium activity of the PLGlu (right, n = 6 mice, P = 0.0002). AM acromiotrapezius muscle. Scale bar = 100 μm in (A–C, G, and L), scale bar = 20 μm in zoomed image in (A, B, and G). Significance was assessed by two-way repeated-measure ANOVA in (E, H, and I), and two-sided Student’s t-test in (J–M). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s. not significant. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM.

The tetra-synaptic glutamatergic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL pathway regulates gastric pain behavior in mice

Next, we investigated whether this glutamatergic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL circuitry (NTSGlu–LPBGlu–PVTGlu–PLGlu) could regulate gastric pain behavior. Since this is a tetra-synaptic connectivity pathway, we determined their functions one synapse by one synapse between two nuclei. We initially determined the role of the NTSGlu neural terminals projecting to the LPB in the modulation of gastric pain. Optogenetic activation of NTSGlu neural axon terminals projecting to the LPB significantly increased the AUC of EMG while optogenetic silencing of the NTSGlu neuronal axon terminals projecting to the LPB significantly reduced the AUC of EMG (Fig. 6A–D, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice for ChR2 group, n = 5 mice for eNpHR group). We next determined the role of the LPBGlu neural terminals projecting to the PVT in the modulation of gastric pain. Optogenetic activation of LPBGlu neural axon terminals projecting to the PVT significantly increased the AUC of EMG while optogenetic silencing of the NTSGlu neuronal axon terminals projecting to the LPB significantly reduced the AUC of EMG (Fig. 6E–H, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). We next determined the role of the PVTGlu neural terminals projecting to the PL in the regulation of gastric pain. Activation of the PVTGlu neuronal axon terminals projecting to the PL significantly increased the AUC of EMG, and inhibition of the PVTGlu neuronal axon terminals projecting to the PL significantly reduced the AUC of EMG (Fig. 6I–L, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). These data suggest the function of the NTS-LPB, LPB-PVT, and PVT-PL neural circuits in regulating gastric pain. We also determined the role of the NTS-PVT neural circuit in the regulation of gastric pain. Whether activating or inhibiting the NTS-PVT neural pathway, it did not alter the AUC of EMG (Fig. S11A–E, P > 0.05, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). Moreover, the circuit-tracing techniques showed that there were neither direct projections from NTS to PL nor from LPB to PL (Figs. 2A, B and S12A, B).

A Experimental timeline of optogenetic manipulation of the NTS-LPB neural pathway. B Schematic showing injection of virus into the NTS and implantation of optical fiber into the LPB. And representative image showing the axonal terminals from NTSGlu in the LPB. C Representative EMG traces and statistical graph of AUC of EMG recordings under normal conditions or upon ChR2- stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0001 in 40 mmHg and 60 mmHg, P = 0.0185 in 80 mmHg). D Representative EMG traces and statistical graph of AUC of EMG recordings under normal conditions or upon eNpHR-stimulation (n = 5 mice, P = 0.0002 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg). E Experimental timeline of optogenetic manipulation of the LPB-PVT neural pathway. F Schematic showing injection of virus into the LPB and implantation of optical fiber into the PVT. And representative image showing the axonal terminals from LPBGlu in the PVT. G, H Representative EMG traces and a statistical graph of the AUC of EMG recordings from mice under normal conditions, as well as during ChR2-stimulation and eNpHR-stimulation (n = 6 mice; P = 0.0001 in 40 mmHg, 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg under ChR2-stimulation; P = 0.0046 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg under eNpHR-stimulation). I Experimental timeline of optogenetic manipulation of the PVT-PL neural pathway. J Schematic showing injection of virus into the PVT and implantation of optical fiber into the PL for optogenetic manipulations. And representative image showing the axonal terminals from PVTGlu in the PL. K, L Representative EMG traces and a statistical graph of the AUC of EMG recordings under normal conditions, as well as during ChR2-stimulation and eNpHR-stimulation (n = 6 mice; P = 0.0020 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0002 in 60 mmHg, P = 0.0009 in 80 mmHg under ChR2-stimulation; P = 0.0002 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg under eNpHR-stimulation). Scale bar = 100 μm in (B, F, and G). Significance was assessed by two-way repeated-measure ANOVA in (C, D, G, H, K, and L). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s. not significant. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Similar results were obtained in six independent experiments and the data shown were from one representative experiment in (B, F, and J).

Since this is a tetra-synaptic connectivity pathway, we then determined their functions as two synapses by two synapses among three nuclei using cre-dependent chemicalgenetics virus strategy and microinjection combined with EMG recordings (Fig. 7A–C). Inhibiting of the NTS-LPB-PVT circuit with cannula administration of CNO into the PVT significantly reduced the AUC of EMG response to GD when compared with the saline-injected group (Fig. 7D, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). Similarly, inhibiting of the LPB-PVT-PL circuit with cannula administration of CNO into the PL significantly reduced the AUC of EMG response to GD when compared with the saline-injected group (Fig. 7E–H, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, two-way repeated measure ANOVA, n = 6 mice). These data suggest that the NTS-LPB-PVT and the LPB-PVT-PL neural circuit play a role in the modulation of gastric pain.

A Experimental timeline of chemogenetics manipulation of the NTS-LPB-PVT neural pathway. B Schematic showing virus injection into the NTS and the LPB, and implantation of cannula into the PVT. C The expression of hM4Di in the LPB and axonal terminals in the PVT. D Representative EMG traces and statistical graph of AUC of EMG recordings under saline or CNO stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0035 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0001 in 60 mmHg and 80 mmHg). E Experimental timeline of chemogenetics manipulation of the LPB-PVT-PL neural pathway. F Schematic showing virus injection into the LPB and the PVT, and implantation of cannula into the PL. G The expression of hM4Di in the PVT and axonal terminals in the PL. H Representative EMG traces and statistical graph of AUC of EMG recordings under saline or CNO stimulation (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0004 in 40 mmHg, P = 0.0015 in 60 mmHg, P = 0.0064 in 80 mmHg). I Experimental timeline of chemogenetics manipulation of the LPB-PVT-PL neural pathway and fiber photometry recording glutamate release in the PL. J Schematic showing injection of scAAV2/1-Cre into the NTS, AAV2/R-vglut2-DIO-hM4Di into the PVT, implantation of the cannula into the LPB for chemogenetics manipulations. And injection of iGluSnFR into the PL, implantation of optical fiber into the PL. K Representative images of iGluSnFR expression in the PL and hM4Di expression in the LPB. L Heatmap and average glutamate release transients in saline and CNO group receiving GD stimulation in male mice. M Averaged peak ΔF/F of glutamate release in saline and CNO in male mice (n = 6 mice, P = 0.0001). N Heatmap and average glutamate release transients in saline and CNO group in female mice. O Averaged peak ΔF/F of glutamate release in saline and CNO in female mice (n = 5 mice, P = 0.0017). Scale bar = 100 μm in (C, G, and K). Significance was assessed by two-way repeated-measure ANOVA in (D, H), and two-sided Student’s t-test in (M, O), ***P < 0.001, n.s. not significant. All data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Similar results were obtained in six independent experiments and the data shown were from one representative experiment in (C, J, and K).

Due to the pivotal role of glutamatergic neurons in this circuit, a fluorescent probe combined with chemicalgenetics was used to manipulate the tetra-synaptic neural circuit and detect glutamate release during GD. scAAV2/1-hsyn-Cre was injected into the NTS, AAV2/Retro-vglut2-DIO-hM4Di-EGFP was injected into the PVT, AAV2/9-hsyn-iGluSnFR was injected into the PL, and a cannula was implanted in the LPB. Specific inhibition of the circuit was achieved by injecting CNO into the LPB. The glutamate release decreased significantly during GD stimulation compared with the saline group (Fig. 7I–M, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, t-test, n = 6 mice). Similar results were obtained from female mice (Fig. 7N, O, **P < 0.01, t-test, n = 5 mice), indicating there was no statistical difference detected between male and female mice. These results further support the notion that glutamatergic neurons play a vital role in transmitting GD-induced gastric pain signals through the tetra-synaptic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL neural circuit from the stomach to the brain. Thus, our data demonstrated that the glutamatergic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL circuitry is necessary and sufficient for the modulation of gastric pain.

Discussion

The study investigated the entire ascending pathway of gastric pain signal transmission. Results revealed that GD stimulation induced gastric pain in mice, resulting in a significant increase in the number of activated neurons in the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL. Functional studies further demonstrated enhanced calcium activity in glutamatergic neurons within the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL. Importantly, this study identified the NTS–LPB–PVT–PL glutamatergic tetra-synaptic neural circuit as sufficient and necessary for regulating gastric pain. Through in-depth exploration, this study discovered that the NTS–LPB–PVT–PL glutamatergic tetra-synaptic neural circuit primarily regulates the transmission of gastric pain signals through the vagal afferent pathway (Fig. 8). This study identifies that there is a visceral pain ascending pathway using gastric pain as an example. The research will provide insight into the stomach–brain axis, particularly the signaling pathway for the perception of gastric pain, and offer potential therapeutic targets.

GD induces an increased c-Fos expression in brain regions, including the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL. The formed glutamatergic NTS–LPB–PVT–PL circuitry holds crucial significance in the transmission of gastric pain. Moreover, the transmission of noxious information from the stomach primarily travels through this pathway via the vagus nerve to convey signals to the cortical regions, resulting in an increase in EMG activity and pain perception. GD gastric distension, NG nodose ganglion, NTS the solitary nucleus, LPB lateral parabrachial nucleus, PVT paraventricular thalamic nucleus, PL prelimbic cortex, Glu glutamatergic neurons, EMG electromyographic.

One of the most important findings is that vagus-NTSGlu initiates the gastric pain signal transmission. While the NTS in the brainstem has been reported to participate in food intake28, the emesis33,34 and encoding the fundamental organizational features of gastrointestinal sensory input22, it remains unclear whether it regulates gastric pain. As GD combined with EMG recording is a well-established method for assessing gastric pain behavior3,25,26,27,35, we employed this approach to investigate the central mechanisms of gastric pain. The first and foremost step was to identify a projection relationship between the stomach and the brain through neurospecific polysynaptic anterograde tracing virus HSV which was different from conventional tracer labeling techniques. While previous studies have explored brain regions structurally connected to the stomach10,11, advancements in technology have led to the discovery of newly connected nuclei, such as the PVT and the PL. However, consistent with prior research, the NTS remains the region with the highest expression abundance. This project pathway was also supported by the c-Fos study since the NTS neurons were activated by noxious GD stimulation. Previous studies have shown that the NTS received dual projections from both the vagus nerve and the spinal nerve36,37 and the noxious GD induces significantly more c-Fos expression in the NTS than in the thoracic spinal cord24. Notably, in the present study, GD stimulation primarily activates glutamatergic neurons in the NTS. Upon subdiaphragmatic vagotomy, the response of NTSGlu to GD vanished, whereas the thoracic spinal cord transection at the T5 level did not impede the calcium activity of the NTSGlu. These findings suggest that the vagus nerve plays a crucial role in the transmission of gastric pain signals to the NTSGlu.

Another important finding is that we confirmed that the PL is a center for the perception of gastric pain induced by GD stimulation using anterograde trans-synaptic viral tracing techniques and immunofluorescent staining. Some studies have reported that decreased neuronal activity in the PL in both neuropathic and inflammatory pain animal models, and activation of the PL neurons has been shown to ameliorate the pain hypersensitivity phenotype in chronic pain mice38,39,40,41. The PL has various types of neurons, including glutamatergic and GABA neurons42,43,44,45, we reveal that GD stimulation predominantly activated glutamatergic neurons in the PL by immunofluorescent staining combined with fiber photometry recordings. Furthermore, extensive experimental data indicates that activation of the PLGlu increases gastric pain behavior, while inhibition of the PLGlu significantly alleviates gastric pain behavior in mice. We speculate that this may be associated with different neuronal types or signals incoming from upstream brain regions, or even different types of pain. The PL may play different roles and assume different roles in various circumstances. In clinical study, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) evidence suggests a close association between the prefrontal cortex and gastric sensation, particularly evident in increased blood oxygen saturation during GD46,47,48. Due to the limitations of clinical research, it is difficult to identify the subregion, and the neuronal types of the prefrontal cortex involved in gastric pain processing, our findings localize the perception of gastric pain to the PL within the cerebral cortex. These findings may potentially contribute to implementing different treatment approaches, including repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) of the PL for patients experiencing various types of gastric pain in clinical settings.

The discovery of the endogenous ascending pain transmission system has played a very important role in the basic research and clinical treatment of somatic pain49,50,51. One important reason why the treatment of chronic visceral pain is currently very difficult in clinical practice is that people are very unclear about the mechanism of visceral pain52. In particular, the endogenous gastric pain ascending pathway was not discovered. Despite accumulating evidence depicting the neural signaling pathways between the stomach and the brain34,53,54,55,56,57, the intact ascending neural circuits that encode gastric pain remain elusive. Our data highlight the existence of an NTSGlu–LPBGlu–PVTGlu–PLGlu pathway that is specifically involved in gastric pain. To exclude the possibility of other circuits in gastric pain processing, we showed that there were no direct projections from NTS to PL. The NTS has projects to PVT, yet the NTS-PVT pathway does not regulate gastric pain and likely regulates overeating disorders as reported previously30. Using labeled retrograde viruses, we also showed that there were no direct projections from LPB to PL. Importantly, we provided evidence to show that the circuit mainly involved projections from glutamatergic neurons. Therefore, the present study discovered a structurally identified tetra-synaptic pathway from the stomach to the brain and enriched the connotation of the stomach–brain axis. To confirm this tetra-synaptic pathway is sufficient and necessary for gastric pain processing, we developed a strategy. This included employing multiple viral vectors coupled with optogenetics and chemogenetics. In addition, a one-synapse-to-one-synapse and two-synapses-to-two-synapse approaches were also utilized to delineate the anatomical and functional roles of this tetra-synaptic pathway. Therefore, our study demonstrated that the NTSGlu–LPBGlu–PVTGlu–PLGlu ascending pathway was engaged in regulating gastric pain behaviors and enriched the denotation of the stomach–brain axis. We observed consistency in the key results across both female and male mice, indicating that the conclusion applies to both sexes. Of note is that this strategy would be expected to be widely applied in the exploration of multiple synaptic circuits of other brain functions and disorders such as anxiety and depression in addition to employing it to confirm the multiple synaptic circuits in gastric pain. Since current viral strategies for multi-synaptic neural circuit regulation are limited, future research needs to explore new methods and technologies to directly study tetra-synaptic connectivity. Another point is that we did not further investigate the downstream pathways of the signal in this study. However, a potential mechanism is that the PL projects to the motor cortex, which subsequently influences the thalamus and rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM), leading to projections to the spinal cord segments innervating the acromiotrapezius muscle to modulate its activity58,59,60. This requires further investigation.

Previous studies have indicated the role of the spinal cord in the response of gastric pain61,62,63. However, our research has identified a tetra-synaptic pathway based on the vagus nerve. Through extensive investigation, we demonstrated that calcium activity in the NTSGlu and the PLGlu, significantly activated during noxious GD stimulation, which can be disrupted by subdiaphragmatic vagotomy but not by thoracic spinal cord transection at the T5 level. Additionally, optogenetic activation of the NTSGlu increased gastric pain in mice, yet this gastric pain behavior can be significantly alleviated upon reactivation of NTSGlu after subdiaphragmatic vagotomy. There is substantial evidence suggesting the crucial contribution of the vagus nerve to gastric pain signals15,27,64,65, providing large support for our study. The observed shift in the time-to-peak calcium activity of the PLGlu following T5x (Fig. 5K). The changes in time-to-peak noted may suggest a role for spinal signaling in the transmission of gastric pain signals. Further research is warranted to explore the entire spinal ascending neural pathways that mediate gastric pain behavior.

In clinic, patients suffering from gastric pain exhibit comorbid psychiatric disorders or eating disorders66,67,68. However, due to the unclear nature of the stomach ascending neural pathway, treatment strategies are very limited. The present study identified a complete ascending neural pathway mediated by the vagus nerve, encompassing the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL, which transmits gastric pain signals. Therefore, intervening in either the gastric-vagus nerve or the PL holds the potential to offer assistance to patients suffering from gastric pain accompanied by psychiatric or eating disorders.

To sum up, this study identified a neural circuit from the stomach to the cortex. The NTSGlu–LPBGlu–PVTGlu–PLGlu circuit is sufficient and necessary for processing gastric pain signals. These findings reveal a visceral pain ascending pathway and enrich the connotation and denotation of the stomach–brain axis. Since the vagus nerve and the PL are two important parts of the endogenous visceral pain ascending pathway and are easy to manipulate, VNS or targeting the PL by rTMS or electric stimulation might provide an effective strategy for the clinical management of gastric pain in patients.

Methods

Animals

Male and female C57BL/6J mice aged 6–8 weeks were obtained from the Animal Research Center of Soochow University and housed under a standard environment (24 ± 2 °C, 40 to 60% relative humidity, and 12/12-h light/dark cycle) with free access to food and water. The handling of the animals was approved by the Soochow University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and was carried out in strict accordance with the guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Stomach–brain virus tracing

Neurospecific polysynaptic anterograde tracing was performed using type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) strain H129 (BrainVTA, Wuhan, China) along with a titer of 2.0E + 09 PFU/mL. Bortezomib (Selleckchem, Houston, USA) was injected intraperitoneally (0.1 mg/mL) to aid HSV infection prior to virus injection36,69. The mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and the abdominal cavity was opened to expose gastro. Three microliter (3 μL) HSV was injected in three different locations on the gastric wall using a Hamilton microsyringe, during which the wall was kept moist using 0.9% saline. The incision was closed using a 4-0 silk suture, and the fluorescent signals were observed 7 days after viral expression. To deduce primary, secondary, etc. synaptic connections from the injection site, an equal amount of HSV was injected at the same location in the gastric wall. EGFP fluorescence expression in the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL was then observed at 3, 5, and 7 days post-injection.

Gastric pain measurement

The assessment of gastric pain behavior involves gastric distension (GD) coupled with EMG recordings of the acromiotrapezius muscle, adapted from a well-established paradigm3,25,26,27.

The procedure for gastric intragastric balloon implantation is outlined briefly as follows. Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and the surgical area was shaved and sterilized with iodophor. The abdominal cavity was opened to expose the stomach using sterile surgical instruments, and a small puncture was made on the bottom of the greater curvature of the stomach with microscopic scissors to insert the balloon. The catheter was sutured onto the gastric wall with the other end threaded under the skin and stuck out from the neck. After surgery, mice were provided with liquid food to avoid distending the stomach from solid food.

To record EMG activities, two electrodes were implanted in the acromiotrapezius muscle3,25,26,27. In brief, the mouse was deeply anesthetized with isoflurane. After making a transverse incision with sterilized scissors, blunt dissection was performed to expose the muscles. Nickel-chromium electrodes were implanted approximately 0.5 cm from the midline on each side of the neck. One end of each sterile nickel-chromium electrode was inserted into the acromiotrapezius muscle, with the other end exposed through the skin at the back incision. The incision was closed with 4-0 sutures, and the exposed electrodes were wrapped with sealing film to prevent the mouse from biting them. The mouse was housed individually post-operation. On day seven after surgery, the gastric pain response was assessed using GD stimulation combined with EMG recordings.

Gastric pain was determined by GD and EMG. The mouse was deeply anesthetized with isoflurane. The balloon tubing was connected to the modified blood pressure monitor. Prior to the gastric pain behavioral test, the mice were allowed to be accommodated in a transparent resin box for 30 min to minimize the impact of the environment on behavioral testing. Mice received a series of graded GD stimulation, each lasting 20 s with 2 min intervals between distensions. EMG was continuously recorded by the Biopac Data Acquisition Systems with an EMG-150C amplifier (Biopac Systems, Inc, Goleta, CA, USA). The EMG traces were analyzed using Acknowledge software (Biopac Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA). The response to GD was defined as an increase in EMG activity above baseline during the 20 s GD period. Data were reported as the area under the curve (AUC) of the integrated EMG after baseline subtraction. The tests were conducted in a blind manner.

Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy

Mice were given liquid food to reduce solid content in the stomach during the experiment one day prior to vagotomy. Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and placed on a surgical heating pad. The abdomen was shaved, sterilized using iodophor, and opened with sterile instruments. The stomach was gently taken from the cavity and kept moist with 0.9% saline throughout the procedure. The esophagus was gently lifted, and the anterior branch of the vagus nerve was cut off with microscopic scissors at the base of the esophagus10,24,70,71.

Thoracic spinal cord transection at the T5 level

The highest spinal cord segment corresponding to the gastric innervation of visceral afferent nerve connections is found at thoracic level 5 (T5), where the spinal transection was performed72. Mice for surgery were prepared as described above. T13 was confirmed by its dorsal spinous process and T5 was confirmed by counting 8 ribs upwards. A skin incision was made at segments T4–T8 along the dorsal midline. Muscle and adipose tissue were bluntly peeled off from the dorsal plate of the spinal cord to expose the region of the T5 vertebrae. The spinal process of the T5 vertebrae was then clamped, and ophthalmic scissors were inserted along the edges of the vertebral plates to cut open the conical plates on both sides, and the plates were carefully removed to completely expose the spinal cord. A small incision was made on the surface of the spinal cord on both sides, a scalpel was inserted into the incision to the ventral base, and a forceful cut was made to completely sever the spinal cord. The incision on the muscle and skin was closed with a suture. The hind limb paralysis of the mice after this procedure indicated successful transection.

Immunofluorescence staining

Mice were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane and intracardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 4% PFA. Brain tissue was collected and fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C for 6 h, and then gradient dehydrated with 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose. Coronal sections of the brain (30 μm) were cut using a Cryostat microtome (Leica, CM1950) at −20 °C. The sections were washed three times with PBS and blocked with blocking solutions (7% normal donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.05% sodium aside) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with appropriate primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. The primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-c-Fos (Cell signaling, 2250S, 1:300), mouse anti-c-Fos (Santa Cruz, sc-271243, 1:500), c-Fos Guinea pig pAb (Asis Biofarm, OB-PGP080, 1:600), rabbit anti-Glutamate (Sigma, G6642, 1:400), and rabbit anti-GABA (Sigma, A2052, 1:400). The remaining unblinded primary antibodies were removed by washing three times with PBS prior to incubation with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibodies used were donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A21206, 1:500), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, A31507, 1:500), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A31507, 1:400), and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, A31572, 1:500). Following another three PBS wash, sections were mounted in medium containing 40, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI, Abcam, AB104139).

Stereotaxic injection

Adult mice aged 6-8 weeks were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane and mounted on a stereotactic frame (RWD, 71000-M, Shenzhen, China). Virus suspensions were loaded into a 10 μL syringe (Gaoge, Shanghai, China) connected to a glass micropipette with a tip, and 200 nL was injected with a speed of 20 nL/min into the targeting regions (NTS: AP = −7.4 mm, ML = 0.5 mm, DV = 4.5 mm; LPB: AP = −5.3 mm, ML = 1.5 mm, DV = 3.5 mm; PVT: AP = −1.3 mm, ML = 0 mm, DV = 3.2 mm; PL: AP = 2.2 mm, ML = 0.2 mm, DV = 2.2 mm) based on a stereotaxic atlas73. At each injection site, the micropipette was left in situ for 10 min after the completion of the injection to allow the viral spread and was subsequently withdrawn slowly. Because bilateral injections might cause more damage to the brain tissue, the unilateral injection (right hemisphere) was performed in the present study. The precision of the injection site was examined after experiments and animals with off-target injections were excluded. All experiments were randomized according to numbers.

For fiber photometry, 200 nL AAV2/9-vglut2-GCaMP6s-EGFP (BrainVTA, Wuhan, China, titer: 2.94E + 12 vg/mL) was unilaterally injected into the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL.

For local selective activation or inhibition of the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL glutamatergic neurons, the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL were unilaterally injected with AAV2/9-vglut2-ChR2-EGFP, AAV2/9-vglut2-eNpHR-EGFP, AAV2/9-vglut2-hM4Di-mCherry, AAV2/9-vglut2-hM3Dq-mCherry, AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP, AAV2/1-hsyn-Flp, AAV-hsyn-DIO-eNpHR-EYFP, AAV-hsyn-DIO-ChR2-EGFP, and AAV2/Retro-hsyn-fDIO-Cre-mCherry (BrainVTA, Wuhan, China, titers: 2–5.5E + 12 vg/mL).

For neural circuit tracing, AAV2/9-vglut2-EGFP, scAAV2/Retro-hsyn-mCherry, scAAV2/1-hsyn-cre, AAV2/9-EF1α-DIO-Ypet-2A-mGFP, and AAV2/Retro-DIO-EGFP (BrainVTA, Wuhan, China, titers: 2–5.5E + 12 vg/mL) were used.

For NTS–LPB–PVT–PL glutamatergic neural circuit functional exploring, AAV2/9-vglut2-ChR2-EGFP, AAV2/9-vglut2-eNpHR-EGFP, AAV2/9-vglut2-hM4Di-mCherry, AAV2/9-vglut2-hM3Dq-mCherry, AAV2/1-hsyn-Cre, and AAV-vglut2-DIO-hM4Di-EGFP (BrainVTA, Wuhan, China, titers: 2–5.5E + 12 vg/mL) were used.

For detecting the neural circuit glutamate release in response to the GD, AAV2/9-hsyn-iGluSnFR-EGFP (BrainVTA, Wuhan, China, titer: 4.5E + 12 vg/mL) was injected into PL, scAAV2/1-hsyn-Cre and AAV2/Retro-vglut2-DIO-hM4Di-EGFP (BrainVTA, Wuhan, China, titers: 2–5.5E + 12 vg/mL) were injected into the NTS and the PVT separately.

Fiber photometry recordings

Fiber photometry (ThinkerTech, Nanjing, China) was utilized to record calcium activity in the NTS, LPB, PVT, and PL 3 weeks after transfection of a virus containing a calcium indicator. Detection methods were as described earlier and are briefly described below6,8. A low-autofluorescence 200-μm-core, 0.37-NA fiber optic (ThinkerTech, Nanjing, China) was implanted 0–100 μm above the virus injection site and affixed to the skull with dental cement. The fluorescence signal was acquired at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz via the data acquisition system including the amplifier (C7319, Hamamatsu) and the photomultiplier tube. Data were classified based on behavioral events in individual experiments, and each stimulus was repeated eight times to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of the data. Fiber-optic recording data were analyzed using custom-written MATLAB (MATLAB R2021a, MathWorks, USA) code using ΔF/F 2s before stimulation as a baseline. The value of ΔF/F = (F − F0)/F0 characterizes the change in fluorescence intensity around the event. Experimental records were analyzed and visualized using Prism 8 GraphPad (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and the ThinkerTech fiber photometric analysis software package.

Behavioral tests

Mouse motor function was measured by the rotarod test. Prior to the formal test, mice were trained at constant speeds (10 r/min, 20 r/min, and 30 r/min) every day until the mice were able to exercise for 5 min on the bar rotator at a constant speed of 30 r/min. During the formal test, mice were given a constant speed of 30 r/min, and their time on the rotating bar was recorded to evaluate their motor performance. Anxiety levels were assessed by the open-field test (OFT). In the OFT, mice were placed in a corner of a square field whose side was 40 cm with sufficient illumination. The movement of mice was recorded without interruption for 10 min. The time that each mouse spent in different areas was analyzed by Anymaze (ANY-maze 2024, Stoelting, USA) software to evaluate anxiety levels.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error with n indicating the number of animals. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) with appropriate inferential methods. The normal distribution of data was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Unless indicated otherwise, data were analyzed using either the two-sided Student’s t-test or the two-way repeated-measure ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the supplementary materials. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Enck, P. et al. Functional dyspepsia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 17081 (2017).

Grover, M., Farrugia, G. & Stanghellini, V. Gastroparesis: a turning point in understanding and treatment. Gut 68, 2238–2250 (2019).

Wang, H. J. et al. Epigenetic upregulation of acid-sensing ion channel 1 contributes to gastric hypersensitivity in adult offspring rats with prenatal maternal stress. Pain 161, 989–1004 (2020).

Stanghellini, V. et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology 150, 1380–1392 (2016).

Chang, L. et al. Gender, age, society, culture, and the patient’s perspective in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 130, 1435–1446 (2006).

Li, Y. C., Wang, Q., Li, M. G., Hu, S. F. & Xu, G. Y. A paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus input to ventral of lateral septal nucleus controls chronic visceral pain. Pain 164, 625–637 (2023).

Xu, Q. Y. et al. Identification of a glutamatergic claustrum-anterior cingulate cortex circuit for visceral pain processing. J. Neurosci. 42, 8154–8168 (2022).

Zhang, F. C. et al. Paraventricular thalamus-insular cortex circuit mediates colorectal visceral pain induced by neonatal colonic inflammation in mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 30, e14534 (2023).

Chang, X., Zhang, H. & Chen, S. Neural circuits regulating visceral pain. Commun. Biol. 7, 457 (2024).

Rinaman, L. & Schwartz, G. Anterograde transneuronal viral tracing of central viscerosensory pathways in rats. J. Neurosci. 24, 2782–2786 (2004).

Horn, C. C. et al. Delineation of vagal emetic pathways: intragastric copper sulfate-induced emesis and viral tract tracing in musk shrews. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 306, R341–R351 (2014).

Grundy, D. Neuroanatomy of visceral nociception: vagal and splanchnic afferent. Gut 51, i2–i5 (2002). Suppl 1.

Ozaki, N., Sengupta, J. N. & Gebhart, G. F. Mechanosensitive properties of gastric vagal afferent fibers in the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 82, 2210–2220 (1999).

Chen, S. L. et al. Subdiaphragmatic vagal afferent nerves modulate visceral pain. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 294, G1441–G1449 (2008).

Cordner, Z. A. et al. Vagal gut-brain signaling mediates amygdaloid plasticity, affect, and pain in a functional dyspepsia model. JCI Insight 6, e144046 (2021).

Frøkjaer, J. B. et al. Modulation of vagal tone enhances gastroduodenal motility and reduces somatic pain sensitivity. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 28, 592–598 (2016).

Ji, R. R. Specialized pro-resolving mediators as resolution pharmacology for the control of pain and itch. Annu Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 63, 273–293 (2023).

Bohotin, C. et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in awake rats reduces formalin-induced nociceptive behaviour and fos-immunoreactivity in trigeminal nucleus caudalis. Pain 101, 3–12 (2003).

Zhang, X. et al. Vagus nerve stimulation modulates visceral pain-related affective memory. Behav. Brain Res. 236, 8–15 (2013).

Laqua, R., Leutzow, B., Wendt, M. & Usichenko, T. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation may elicit anti- and pro-nociceptive effects under experimentally-induced pain—a crossover placebo-controlled investigation. Auton. Neurosci. 185, 120–122 (2014).

Usichenko, T., Laqua, R., Leutzow, B. & Lotze, M. Preliminary findings of cerebral responses on transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation on experimental heat pain. Brain Imaging Behav. 11, 30–37 (2017).

Ran, C., Boettcher, J. C., Kaye, J. A., Gallori, C. E. & Liberles, S. D. A brainstem map for visceral sensations. Nature 609, 320–326 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. A vagal-NTS neural pathway that stimulates feeding. Curr. Biol. 30, 3986–3998.e3985 (2020).

Traub, R. J., Sengupta, J. N. & Gebhart, G. F. Differential c-fos expression in the nucleus of the solitary tract and spinal cord following noxious gastric distention in the rat. Neuroscience 74, 873–884 (1996).

Winston, J. H. & Sarna, S. K. Developmental origins of functional dyspepsia-like gastric hypersensitivity in rats. Gastroenterology 144, 570–579.e573 (2013).

Wang, H. J. et al. DNMT1 involved in the analgesic effect of folic acid on gastric hypersensitivity through downregulating ASIC1 in adult offspring rats with prenatal maternal stress. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 29, 1678–1689 (2023).

Lamb, K., Kang, Y. M., Gebhart, G. F. & Bielefeldt, K. Gastric inflammation triggers hypersensitivity to acid in awake rats. Gastroenterology 125, 1410–1418 (2003).

Qiu, W. et al. Multiple NTS neuron populations cumulatively suppress food intake. Elife 12, e85640 (2023).

Ly, T. et al. Sequential appetite suppression by oral and visceral feedback to the brainstem. Nature 624, 130–137 (2023).

Fan, S. et al. Microbiota-gut–brain axis drives overeating disorders. Cell Metab. 35, 2011–2027.e2017 (2023).

Cheng, W. et al. Hindbrain circuits in the control of eating behaviour and energy balance. Nat. Metab. 4, 826–835 (2022).

Jun, S. et al. Circuit-specific control of blood pressure by PNMT-expressing nucleus tractus solitarii neurons. Neurosci. Bull. 39, 1193–1209 (2023).

Huo, L. et al. Brain circuits for retching-like behavior. Natl Sci. Rev. 11, nwad256 (2024).

Xie, Z. et al. The gut-to-brain axis for toxin-induced defensive responses. Cell 185, 4298–4316.e4221 (2022).

Ozaki, N., Bielefeldt, K., Sengupta, J. N. & Gebhart, G. F. Models of gastric hyperalgesia in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 283, G666–G676 (2002).

Chen, Y. et al. Distinct neural networks derived from galanin-containing nociceptors and neurotensin-expressing pruriceptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2118501119 (2022).

Ben Rehouma, M. et al. Acute visceral pain in rats: vagal nerve block compared to bupivacaine administered intramuscularly. Anesth. Analg. 133, 1311–1320 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Role of prelimbic GABAergic circuits in sensory and emotional aspects of neuropathic pain. Cell Rep. 12, 752–759 (2015).

Ji, G. et al. Cognitive impairment in pain through amygdala-driven prefrontal cortical deactivation. J. Neurosci. 30, 5451–5464 (2010).

Wang, G. Q. et al. Deactivation of excitatory neurons in the prelimbic cortex via Cdk5 promotes pain sensation and anxiety. Nat. Commun. 6, 7660 (2015).

Tan, L. L. & Kuner, R. Neocortical circuits in pain and pain relief. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 458–471 (2021).

Yu, L. et al. Activity in projection neurons from prelimbic cortex to the PVT is necessary for retrieval of morphine withdrawal memory. Cell Rep. 35, 108958 (2021).

Jiang, L. X. et al. Diminished activation of excitatory neurons in the prelimbic cortex leads to impaired working memory capacity in mice. BMC Biol. 21, 171 (2023).

Woo, E., Datta, D. & Arnsten, A. F. T. Glutamate metabotropic receptor type 3 (mGlu3) localization in the rat prelimbic medial prefrontal cortex. Front Neuroanat. 16, 849937 (2022).

Kin, K., Francis-Oliveira, J., Kano, S. I. & Niwa, M. Adolescent stress impairs postpartum social behavior via anterior insula-prelimbic pathway in mice. Nat. Commun. 14, 2975 (2023).

Ladabaum, U., Roberts, T. P. & McGonigle, D. J. Gastric fundic distension activates fronto-limbic structures but not primary somatosensory cortex: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroimage 34, 724–732 (2007).

Wang, G. J. et al. Gastric distention activates satiety circuitry in the human brain. Neuroimage 39, 1824–1831 (2008).

Ladabaum, U. et al. Gastric distention correlates with activation of multiple cortical and subcortical regions. Gastroenterology 120, 369–376 (2001).

Markenson, J. A. Mechanisms of chronic pain. Am. J. Med. 101, 6s–18s (1996).

Choi, S. et al. Parallel ascending spinal pathways for affective touch and pain. Nature 587, 258–263 (2020).

Finnerup, N. B., Kuner, R. & Jensen, T. S. Neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to treatment. Physiol. Rev. 101, 259–301 (2021).

LeBrett, W. G. & Chang, L. Prescription pain medications for disorders of gut-brain interaction: comparing usage patterns with clinical practice recommendations. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 35, e14645 (2023).

Zhang, T., Perkins, M. H., Chang, H., Han, W. & de Araujo, I. E. An inter-organ neural circuit for appetite suppression. Cell 185, 2478–2494.e2428 (2022).

Marino, R. A. M. et al. Control of food approach and eating by a GABAergic projection from lateral hypothalamus to dorsal pons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 8611–8615 (2020).

Han, Y. et al. A hindbrain dopaminergic neural circuit prevents weight gain by reinforcing food satiation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf8719 (2021).

Borgmann, D. et al. Gut-brain communication by distinct sensory neurons differently controls feeding and glucose metabolism. Cell Metab. 33, 1466–1482.e1467 (2021).

Jais, A. et al. PNOC(ARC) neurons promote hyperphagia and obesity upon high-fat-diet feeding. Neuron 106, 1009–1025.e1010 (2020).

Gao, L. et al. Single-neuron projectome of mouse prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 515–529 (2022).

Apkarian, V. A., Hashmi, J. A. & Baliki, M. N. Pain and the brain: specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain 152, S49–s64 (2011).

Zhang, Z. et al. Spinal projecting neurons in rostral ventromedial medulla co-regulate motor and sympathetic tone. Cell 187, 3427–3444.e3421 (2024).

Dang, K., Bielefeldt, K. & Gebhart, G. F. Gastric ulcers reduce A-type potassium currents in rat gastric sensory ganglion neurons. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286, G573–G579 (2004).

Qin, C., Chen, J. D., Zhang, J. & Foreman, R. D. Somatic afferent modulation of thoracic (T9-T10) spinal neurons receiving gastric mechanical input in rats. Neuromodulation 13, 77–86 (2010).

Bielefeldt, K., Ozaki, N. & Gebhart, G. F. Mild gastritis alters voltage-sensitive sodium currents in gastric sensory neurons in rats. Gastroenterology 122, 752–761 (2002).

Hou, L. et al. Auricular vagus nerve stimulation improves visceral hypersensitivity and gastric motility and depression-like behaviors via vago-vagal pathway in a rat model of functional dyspepsia. Brain Sci. 13, 253 (2023).

Kang, Y. M., Lamb, K., Gebhart, G. F. & Bielefeldt, K. Experimentally induced ulcers and gastric sensory-motor function in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 288, G284–G291 (2005).

Yao, C. et al. Exploring the bidirectional relationship between pain and mental disorders: a comprehensive Mendelian randomization study. J. Headache Pain. 24, 82 (2023).

Gracie, D. J., Hamlin, P. J. & Ford, A. C. The influence of the brain–gut axis in inflammatory bowel disease and possible implications for treatment. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 632–642 (2019).

Salvioli, B. et al. Audit of digestive complaints and psychopathological traits in patients with eating disorders: a prospective study. Dig. Liver Dis. 45, 639–644 (2013).

Cai, B. et al. A direct spino-cortical circuit bypassing the thalamus modulates nociception. Cell Res. 33, 775–789 (2023).

Kim, D. Y. et al. A neural circuit mechanism for mechanosensory feedback control of ingestion. Nature 580, 376–380 (2020).

Bercik, P. et al. The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology 141, 599–609, (2011). 609.e591-593.

Loukas, M. et al. A review of the thoracic splanchnic nerves and celiac ganglia. Clin. Anat. 23, 512–522 (2010).

Paxinos, G., Franklin, K. B. J. Paxinos and Franklin’s the mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. In: Paxinos and Franklin’s the Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (Elsevier, 2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81920108016 and 32230041 to G.-Y.X.), the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX22_3215 to F.-C.Z.), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors sincerely thank Dr. Yang Yu (Institute of Neuroscience, Soochow University) and Ze-Yuan Wu (River Valley High School, Singapore) for advice and assistance in revising the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: G.-Y.X. Experiment conductance and data analyses: F.-C.Z., R.-X.W., and D.L. Acquisition of data: F.-C.Z., Y.-C.L., X.-X.D., S.H., and Q.S. Manuscript writing and revision: F.-C.Z., R.L., and G.-Y.X.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Melanie Kaelberer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, FC., Weng, RX., Li, D. et al. A vagus nerve dominant tetra-synaptic ascending pathway for gastric pain processing. Nat Commun 15, 9824 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54056-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54056-w

This article is cited by

-

A novel approach to the prevention and management of cardiovascular diseases: targeting brain–heart axis

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)

-

Upregulation of NR2A in Glutamatergic VTA Neurons Contributes to Chronic Visceral Pain in Male Mice

Neuroscience Bulletin (2025)