Abstract

Chronological age is an imperfect estimate of molecular aging. Epigenetic age, derived from DNA methylation data, provides a more nuanced representation of aging-related biological processes. We examine the bidirectional relationship between epigenetic age and brain health events (stroke, dementia, late-life depression) using data from 4,018 participants. Participants with a prior brain health event are 4% epigenetically older (β = 0.04, SE = 0.01), indicating these conditions are associated with accelerated aging beyond that captured by chronological age. Additionally, a one standard deviation increase in epigenetic age is associated with 70% higher odds of experiencing a brain health event in the next four years (OR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.16–2.50), suggesting epigenetic age acceleration is not just a consequence but also a predictor of poor brain health. Mendelian Randomization analyses replicate these findings, supporting their causal nature. Our results support using epigenetic age as a biomarker to evaluate interventions aimed at preventing and promoting recovery after brain health events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age remains the principal risk factor for neurodegenerative conditions1 and the most substantial non-modifiable determinant for cerebrovascular disease, posing significant challenges to understanding the complex interplay of biological and molecular aging processes with disease risk2. Despite chronological age serving as a conventional marker, recent advancements have introduced more sophisticated measures of aging. Central to these innovations are epigenetic clocks, an approach based on the analysis of DNA methylation patterns at CpG sites3. This methylation process chemically alters DNA molecules, thereby modulating gene expression without changing the DNA sequence. In contrast to the DNA sequence, which remains largely unchanged throughout life, DNA methylation exhibits a degree of plasticity, allowing for changes in response to diverse lifestyle and environmental exposures, including established cardiovascular risk factors4.

Epigenetic clocks, derived from weighted aggregation of methylation across select CpG sites, echo the principles of polygenic risk scores, offering a quantifiable measure of biological age5. The selection of CpG sites and their integration into a singular biological age metric is informed by robust statistical models trained on specific outcomes, ranging from chronological age to more complex phenotypes associated with health span and lifespan. This approach has led to the development of various epigenetic clocks. Initially, these clocks were calibrated on chronological age6,7,8,9,10, but subsequent iterations have focused on broader phenotypes, such as time-to-death11 or clinical parameters linked to morbidity and mortality3. Notably, some epigenetic clocks, such as the PhenoAge3, GrimAge11, and Zhang12 clocks have demonstrated a superior ability to predict mortality and various health outcomes, significantly surpassing the predictive power of chronological age.

The pursuit of health and longevity is fundamentally tied to the preservation of a healthy brain. In the context of an aging global population, the imperative to sustain brain health becomes paramount, especially given the increased prevalence and incidence of neurological disorders, now the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years worldwide13. Among aging-related brain diseases, stroke, dementia, and late-life depression have the highest prevalence and incidence14, significantly impacting global brain health due to their disruptive effects on normal brain function. These conditions are closely related, sharing risk factors such as smoking, diet, physical activity, and socio-economic health determinants15,16,17,18,19, which are also known to influence epigenetic clocks4. Furthermore, stroke, dementia, and late-life depression can act as risk factors for each other, creating a complex web of interacting health problems20,21. Finally, the occurrence of late-life depression has been shown to be associated with cerebral small vessel disease, aligning it with stroke and dementia from a pathophysiological perspective22,23. This intricate relationship has given rise to the view that these conditions should not be treated as isolated outcomes, but as interconnected components of a broader aging process that requires a comprehensive approach24,25. To promote healthy aging, it is thus necessary to deepen our understanding of the relationship between brain health and the systemic manifestations of the aging process.

Given the growing interest in understanding the aging process beyond chronological age and growing importance of brain health as a determinant of healthy aging, we test the hypothesis that brain health events accelerate epigenetic aging, and conversely, that accelerated epigenetic aging increases the risk of brain health events. Given that the study of DNA methylation in brain health is still in its early stages, research in this field is limited and often involves small sample sizes. To address this, we conduct our analyses using the Health and Retirement Study, a large longitudinal study of older adults that is representative of the U.S. population (Fig. 1). The collection of DNA methylation data in 2016 provides an opportunity to assess the impact of past brain health events as well as the future risk of such events in relation to epigenetic age. To evaluate the hypothesized bidirectional relationships, we use both traditional epidemiological associations and a genetic mendelian randomization (MR) framework. By leveraging genetic variants as instrumental variables, MR enable us to support the causality of these associations with a higher level of evidence compared to observational analyses alone26,27.

1st Stage: We evaluate the association between a history of brain health events (stroke, dementia or late-life depression) and epigenetic age acceleration using a cross-sectional study design. Epigenetic age is derived from DNA methylation data collected from venous blood in 2016. 2nd Stage: We evaluate the association between accelerated epigenetic age and the risk of subsequent brain health events using a prospective study design. We leverage Mendelian Randomization analyses to assess the causality of the associations described in steps 1&2 using genetic variants as instruments. MR = Mendelian Randomization. Created in BioRender. Falcone, G. (2024) BioRender.com/c48z976.

Results

Cohort characteristics

The HRS enrolled 42,233 participants between 1992 and 2016. Of these, 4018 provided blood samples in 2016 and were included in our analyses (Fig. 2). Comparison of baseline characteristics between the complete HRS cohort and the subset with DNA methylation (DNAm) data can be found in Supplementary Table 1. The baseline characteristics of the studied population are presented in Table 1. The average age at DNAm data acquisition was 70 years, 58% were females, 17% were Blacks, and 5% were Hispanics, 64% had prevalent hypertension, 29% prevalent diabetes, 27% prevalent heart condition, mean BMI was 29, 11% were current smokers and 44% past smokers.

The effects of brain health events on epigenetic age (Stage 1) are studied in all participants with DNAm data. The effects of epigenetic age on subsequent brain health events (Stage 2) are studied in participants with DNAm and follow-up data, excluding those with a history of prior events. Genetic associations for epigenetic age are conducted in participants with both genetic and DNAm data. Genetic associations for brain health events are conducted in all participants with genetic data.

First stage: history of brain health events and epigenetic age

Of the 4,018 participants included in this cross-sectional analysis at the time of blood sample collection in 2016, 342 (8.5%) had a stroke, 298 (7.4%) had dementia, and 322 (8.0%) already had a late-life major depressive episode prior to DNAm acquisition. This resulted in 806 (20.1%) participants with a history of at least one brain health event, including 127 (3.2%) with two events and 13 (0.3%) with all three events. Epigenetic age was evaluated using 13 different epigenetic clocks. To avoid selecting specific clocks a priori, we used their average contribution after normalization as our main measure of epigenetic age. In multivariable linear regression adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, cardiovascular risk factors (BMI, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes) and comorbidities (heart attack, coronary artery disease, angina, congestive heart failure), brain health events were associated with a 4% increase (beta = 0.04, SD = 0.01, p = 0.002) in mean epigenetic age (Fig. 3 and Table 2). This association was strengthened when only adjusting for age, sex and race/ethnicity, with an 8% increase (beta = 0.08, SD = 0.01, p < 0.001) in mean epigenetic age. When focusing solely on the 4 more recent second-generation epigenetic clocks, which were constructed using both chronological age and health-related outcomes, we found that brain health events were associated with a 9% increase in mean epigenetic age (beta = 0.09, SD = 0.02, p < 0.001) after adjusting for all covariates.

A. Cross-sectional analysis: percentage of change in epigenetic ages following a brain health event after adjusting for chronological age, sex, race and ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, BMI, history of heart attack, coronary artery disease, angina, or congestive heart failure. N = 4018. Data are presented as linear regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals. Clocks displayed in red belong to the second generation of epigenetic clocks. B Longitudinal analysis: Odds Ratios of brain health events per one standard deviation increase in epigenetic age adjusting for chronological age, sex, and race and ethnicity. The second-generation epigenetic clocks are highlighted in red. N = 2,967. Data are presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Clocks displayed in red belong to the second generation of epigenetic clocks. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In secondary analyses that considered each brain health event type separately, a history of stroke was associated with a 6% increase in epigenetic age (beta = 0.06, SD = 0.02, p = 0.001 - Figure S2 and Table S7) after adjusting for demographics, risk factors, and comorbidities. Similarly, a history of dementia was associated with a 4% increase (beta = 0.04, SD = 0.02, p = 0.035 - Figure S3 and Table S9). A history of late-life major depressive disorder was not associated with an increase in epigenetic age in the fully adjusted model (beta= 0.01, SD = 0.02, p = 0.673 - Figure S4 and Table S11). Also, a history of either stroke or dementia was associated with a 4% increase in mean epigenetic age (beta= 0.04, SD = 0.01, p = 0.003 - Figure S1 and Table S5).

First stage: sensitivity analyses

Given the existing variation in the age cutoff used to define late-life depression, in sensitivity analyses we considered an age threshold of 60 instead of 65 at the first major depressive episode. Out of 4,018 participants, 583 (14.5%) had a late-life depression prior to DNAm acquisition and 1014 (25.2%) had a history of at least one brain health event. In multivariable linear regression adjusting for age, sex and race/ethnicity, brain health events were associated with an 8% increase (beta = 0.08, SD = 0.01, p < 0.001) in mean normalized epigenetic age. After adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities as well, a history of brain health events was associated with a 5% increase (beta = 0.05, SD = 0.01, p < 0.001) in mean epigenetic age (Table S13).

First stage: Mendelian randomization analyses

Several different MR analyses (Fig. 4) confirmed a positive association between genetically determined brain health events and accelerated epigenetic aging. In the primary analysis using 985 independent genetic instruments for brain health events and the inverse variance weighted MR method, genetically determined brain health events were associated with a 11% increase in mean epigenetic age (beta = 0.11, SD = 0.03, P < 0.001 – Table 3). The weighted median and MR-Egger methods, more conservative analytical approaches that are more robust to horizontal pleiotropy, yielded similar results, with genetically determined brain health events being associated, respectively, with 8% (beta = 0.8, SD = 0.04, P = 0.052) and 10% (beta = 0.1, SD = 0.04, P = 0.01) increases in epigenetic age. The MR-PRESSO global test and the MR-Egger Intercept did not suggest the presence of pleiotropy.

Summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression were clumped to identify significant genetic variants, which were then pooled. The pooled variants underwent further clumping to ensure their independence, with palindromic variants excluded. The associations between these genetic instruments and brain health outcomes, as well as epigenetic age, were analyzed in HRS participants. Finally, Mendelian Randomization analyses were performed to estimate the causal effect of brain health events on epigenetic age.

Second stage: epigenetic age and subsequent risk of brain health events

Of the 4018 participants with DNAm data, 806 (20.1%) had a history of brain health events before 2016 and 245 (6.1%) were missing data after the DNAm acquisition in 2016 (waves 14 and 15), including 116 (2.9%) who died and 129 (3.2%) who were lost to follow-up (Fig. 2). Of the 2967 participants included in the prospective analysis, 81 (2.7%) developed a stroke, 100 (3.4%) developed dementia and 95 (3.2%) developed a late-life major depressive disorder. This resulted in 261 (8.8%) participants developing at least one brain health event over the 4 years of follow-up, including 15 (0.5%) developing two. In multivariable logistic regression adjusting for demographics (age, sex and race/ethnicity), one SD increase in epigenetic age was associated with a 70% increase (OR = 1.70, 95%CI: 1.16–2.50) in the odds of brain health events (Fig. 3 and Table 2). When considering only the second-generation epigenetic clocks, each standard deviation increase in mean epigenetic age was associated with a 24% increase in the odds of brain health events (OR = 1.24, 95% CI: 0.99–1.56).

Further adjustments for cardiovascular risk factors (BMI, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes) and comorbidities (heart attack, coronary artery disease, angina, and congestive heart failure) can be considered depending on the objective of the analysis. These factors are known to influence methylation changes and might already be reflected in the estimation of epigenetic age3,28,29. From a biological perspective, adjusting for these factors could result in overadjustment. However, from a clinical perspective, these factors should be considered to validate the clinical utility of epigenetic age measurements. Therefore, we also tested a model that included these factors, in addition to demographics. It indicated that a one SD increase in epigenetic age was still associated with a 48% increase in the odds of brain health events (OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 0.99–2.21 – Table 2).

In secondary analyses, we observed that epigenetic age acceleration was associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing a combined outcome of stroke and dementia. This association was also observed when stroke and dementia were analyzed separately. However, no such association was found with late-life depression. Specifically, we found a 112% increase in the odds of developing either stroke or dementia (OR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.35–3.32 – see Figure S1 and Table S6) for each one SD increase in epigenetic age, after adjusting for demographics. Similar results were obtained when considering stroke (OR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.12–4.04 – see Figure S2 and Table S8) and dementia (OR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.10–3.56 – see Figure S3 and Table S10) individually. However, for late-life depression, the association was entirely non-significant (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.43–1.52 – see Figure S4 and Table S12).

Second stage: sensitivity analyses

We replicated the observational analyses with late-life depression ascertained using an age threshold of 60 instead of 65 at the first major depressive episode. Out of the 2779 participants included in the prospective analysis, 121 (4%) developed a late-life depressive disorder and 269 (10%) developed at least one brain health event over the 4 years of follow-up. In multivariable logistic models adjusting for demographics, one SD increase in epigenetic age was associated with a 57% increase (OR = 1.57, 95%CI: 1.07–2.31, Table S14) in the odds of brain health events.

Additionally, we replicated the observational analyses excluding those participants missing data for any of the waves 14 and 15, as opposed to only excluding participants missing data for both of the two waves. Of the 4018 participants with DNAm data, 804 (20%) had a history of brain health event, 245 (6%) died and 394 (10%) were missing data for any of the waves 14 and 15, so this analysis included 2,573 participants. Of these, 79 (3%) developed a stroke, 75 developed dementia (3%), and 78 (3%) developed a late-life major depressive disorder. We observed a similar trend as in the primary analysis with a 1 SD increase in epigenetic age leading to a 78% (OR = 1.78, 95%CI: 1.16−2.72, Table S15) increase in the odds of brain health events after accounting for demographics.

Second stage: Mendelian Randomization analyses

Several different MR approaches (Fig. 5) confirmed a positive association between genetically determined epigenetic age and higher odds of brain health events. In the primary analysis using 777 independent genetic instruments and the inverse variance weighted MR method, one SD increase in genetically determined epigenetic age was associated with 15% higher odds of brain health events (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.06–1.25 – Table 3). The weighted median method yielded similar results (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.00–1.31), as well as the MR Egger method (OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.00–1.31). The MR-PRESSO global test, as well as the Egger intercept were not significant, indicating no substantial pleiotropy.

Summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of several epigenetic clocks were clumped to identify significant genetic variants, which were then pooled. The pooled variants underwent further clumping to ensure their independence, with palindromic variants excluded. The associations between these genetic instruments and epigenetic age, as well as brain health outcomes were analyzed in HRS participants. Finally, Mendelian Randomization analyses were performed to estimate the causal effect of epigenetic age acceleration on the risk of brain health events.

Discussion

In this two-stage epigenetic study within the Health and Retirement Study, we identified a significant bidirectional relationship between epigenetic aging and brain health events. In the first stage, the cross-sectional analysis revealed an association between a history of brain health events and accelerated epigenetic age. Specifically, patients with a prior history of stroke, dementia, or late-life depression exhibited a statistically significant increase in mean normalized epigenetic age, findings that remained robust after adjusting for a range of covariates. This association was further confirmed through Mendelian Randomization analyses, suggesting a causal linkage. In the second stage, the prospective cohort analysis revealed that individuals with an accelerated epigenetic age were at a substantially higher risk of developing brain health events. This association persisted after adjustments for confounders and was also observed in Mendelian Randomization analyses, again providing evidence for a causal relationship. These findings underscore the reciprocal influence between accelerated aging and the manifestation of brain health events, enhancing our comprehension of this complex interplay.

Mounting evidence points to the importance of epigenetic age as a more accurate indicator of true biological aging compared to chronological age3,30. Numerous studies have established that DNA methylation predicts all-cause mortality more accurately than chronological age alone31,32,33,34. This predictive ability has been first studied using epigenetic data from specific tissues, where methylation patterns are closely linked to disease development. For instance, accelerated epigenetic aging in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is associated with increased amyloid accumulation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease35. Similarly, the progression of osteoarthritis and obesity is reflected in the accelerated methylation patterns of cartilage36 and liver tissues29, respectively. Given the challenges and risks associated with tissue-specific sample collection, whole blood samples have become increasingly utilized for determining epigenetic age30. This approach has been validated, showing a high correlation between epigenetic age derived from whole blood and that from specific tissues, making it a reliable proxy for general epigenetic age assessment3. Subsequently, blood-derived epigenetic age acceleration has been linked to the occurrence of various conditions, including cancer37,38,39,40, cardiovascular and coronary heart diseases3, Parkinson’s disease41 and frailty42,43. In addition, key risk factors such as high blood pressure28, BMI29, triglycerides3, and serum glucose levels3,28, as well as smoking3 and low physical activity3,28 have been shown to accelerate aging-related epigenetic modifications. These findings emphasize the influence of environmental factors and the dynamic nature of DNA methylation status. Additionally, they suggest that epigenetic clocks could serve as a “surrogate” of an individual’s risk factor profile, capturing DNA methylation changes resulting from the presence of cardiovascular risk factors or comorbidities. For this reason, and to avoid overadjustment, we did not adjust for these covariates in the second stage of our observational analyses, but we included them in an alternative model to assess the added clinical utility of epigenetic age. Finally, at a cellular level, DNA methylation clocks have been connected to three of the nine recognized hallmarks of aging44: nutrient sensing, mitochondrial function, and stem cell composition, highlighting their integral role in characterizing the aging process45.

This study adds evidence to epigenetic aging research by focusing on a broad observational outcome related to brain health. Stroke, dementia, and late-life depression, the most common aging-related brain conditions, are intricately linked. They share overlapping risk factors, including smoking, diet, physical activity, and socio-emotional health determinants, which contribute to the occurrence of all three15,16,17,18,19 and a common small vessel disease pathophysiology22,23. Furthermore, the occurrence of one condition markedly increases the likelihood of developing the others: a history of depression heightens the risk of stroke46 and dementia47,48,49; stroke raises the chances of subsequent dementia21 or depression50; and dementia itself is a risk factor for both hemorrhagic stroke51 and depression52. This intricate interplay has led to the perspective that these conditions should not be examined in isolation, but rather collectively, as distinct yet connected manifestations of a broader brain health aging process24,25. Our findings lend substantial support to this viewpoint. We demonstrate that an acceleration in the body’s epigenetic aging process significantly increases the risk of developing stroke or dementia, but not late-life depression. Because the pace of epigenetic aging can be slowed by lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise28, our results suggest that taking care of our body as we get older is a potentially effective way of preventing brain health events. Moreover, our study reveals that stroke and dementia not only result from, but also contribute to, a general acceleration of epigenetic aging, as evidenced by blood-derived methylation changes. These results underscore the systemic nature of these conditions, suggesting that they should be considered comprehensively, rather than as pure neurological or psychiatric disorders.

Our study also provides evidence suggesting that the association between epigenetic aging and brain health are causal, as demonstrated by the results of our MR analyses. MR is an epidemiological method that leverages DNA sequence variants as instrumental variables, offering a powerful means to deduce potential causal links between exposures and outcomes26,27. By employing genetic variants that are randomly assigned during meiosis and remain constant throughout an individual’s life, MR effectively acts as a form of natural randomization. This approach is particularly valuable as it helps to counteract confounding by environmental factors and reverse causation, which are prevalent sources of bias in observational studies. Consequently, MR serves as a valuable tool, complementing observational studies by adding a layer of evidence to suggest the causal nature of observed relationships53. However, it is important to acknowledge that MR does not replace randomized controlled trials, which are still the gold standard for establishing causal associations. MR provides a crucial bridge in the hierarchy of scientific proof, particularly in scenarios where conducting trials is impractical or unethical.

Our findings open up avenues for future research. First, while our study highlights a relationship between epigenetic clocks and brain health events, it does not elucidate the pathways mediating this association. Each epigenetic clock we considered reflects the aggregate contribution of multiple DNAm loci, and it is known that methylation levels at some of these loci influence plasma protein levels11. Follow-up studies could explore associations between plasma proteins modulated by DNAm changes and brain health events, providing insights into how epigenetic clocks impact the risk of these outcomes. Furthermore, epigenetic clocks might aid in the early detection of individuals at elevated risk of poor brain health. Currently, observational risk scores and polygenic risk scoring are widely recognized methods for categorizing individuals into different risk groups54. While our study suggests a potential role for epigenetic clocks in risk assessment, further research is needed to validate their predictive utility and determine how best to integrate them with existing risk models. This combined approach could significantly facilitate early intervention strategies. Finally, there is an emerging interest in therapeutic interventions focused on modulating the epigenetic aging process itself, with the goal of preventing aging-related observational events. Recent research in mice has shown that DNA methylation clocks can be reversed through epigenetic reprogramming, leading to notable increases in life expectancy55. This underscores the significant role of epigenetic modifications on the aging process as a whole. Such findings may open up possibilities for the development of targeted treatments that not only manage but also proactively mitigate the risks of aging-related neurological conditions by addressing their underlying epigenetic mechanisms. However, the translation of these findings to humans remains uncertain, and it is not yet clear whether targeting epigenetic markers will be truly relevant or effective in clinical settings.

The primary strength of our study is the utilization of the Health and Retirement Study, which is among the largest and best-characterized cohorts with DNA methylation data to date. Acquiring DNA methylation data is often a costly endeavor, leading to smaller datasets that typically require integration with other datasets to reach sufficient power11. The Health and Retirement Study’s substantial size, combined with its demographic representativeness of the US population, significantly bolsters the generalizability of our findings to older Americans. Additionally, the application of MR analyses enabled us to strengthen our observational results, providing a more compelling argument for the causal nature of the relationships we identified. However, our study is not without limitations. First, while our study included several cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities, the absence of certain measurements (e.g., blood pressure medications) limited our ability to adjust for comprehensive clinical risk scores like the Framingham score, and we cannot rule out the possibility that unaccounted risk factors may be influencing the observed acceleration in epigenetic aging or the increased risk of brain health events. Second, our cross-sectional observational analysis is likely influenced by survival bias. It’s reasonable to assume that survivors of brain health events are generally healthier and may demonstrate slower epigenetic aging compared to non-survivors. This factor could potentially skew our results towards the null hypothesis.

In conclusion, our findings using high-quality data from the Health and Retirement Study cohort establish bidirectional associations between epigenetic aging and brain health events. We have demonstrated that a history of stroke, dementia, or late-life depression is not only associated with accelerated epigenetic aging but also that an advanced epigenetic age increases the likelihood of these conditions. Through Mendelian Randomization analyses, we provide evidence supporting the potential causal nature of these associations. While our study contributes to the understanding of aging-related brain health and underscores the possible role of epigenetic factors, further research is warranted to confirm these associations and explore their practical implications. Overall, our work suggests opportunities for future research, particularly in early risk assessment and intervention strategies, and highlights the promising potential of epigenetic clocks in advancing brain health outcomes.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University School of Medicine (protocol number: 2000038837). Ethical approval for the Health and Retirement Study was obtained from the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (protocol number: HUM00061128). All participants gave informed written consent. HRS offers financial payments as tokens of appreciation to respondents for participating, but these were not intended as compensation.

Study design

We conducted a 2-stage observational and genetic study nested within the HRS (Fig. 1). Our goal was to investigate two different hypotheses: first, that persons who have survived brain health events, including stroke, dementia, and late-life depression, exhibit epigenetic age acceleration; and second, that those with accelerated epigenetic aging are at an elevated risk for subsequent brain health events. Both hypotheses were examined through a combination of observational and genetic analyses. To investigate the first hypothesis, we performed a nested cross-sectional analysis on HRS participants who had available DNA Methylation data. This allowed us to assess the association between survival from brain health events and epigenetic aging. To test the second hypothesis, we implemented a prospective cohort design using the same HRS group with available methylation data. This design enabled us to observe whether individuals with accelerated epigenetic aging were more likely to experience subsequent brain health events. The genetic analyses for both stages were conducted using one-sample Mendelian randomizations within the HRS cohort.

The health and retirement study

The HRS is an ongoing, longitudinal study that is nationally representative of older adults in the United States. Its primary aim is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the health and economic circumstances associated with aging at both individual and population levels. The HRS sample was compiled through multiple phases of recruitment and data collection. The inaugural cohort, enrolled in 1992, included individuals born between 1931 and 1941 (who were then aged 51–61), along with their spouses of any age. Subsequently, a distinct study named “Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old” (AHEAD) was conducted, focusing on the cohort born between 1890 and 1923 (who were then aged 70 and above). In 1998, these two samples were merged and supplemented with the addition of two more cohorts: the “Children of the Depression” (CODA, born 1924–1930) and the “War Babies” (born 1942–1947). This was done to ensure the sample accurately represented the U.S. population over the age of 50. Later, the “Early Baby Boomers” (EBB, born 1948–1953) and the “Mid Baby Boomers” (MBB, born 1954–1959) were added in 2004 and 2010, respectively. The most recent addition was the “Late Baby Boomers” (LBB, born 1960–1965) in 201656. As of now, the HRS has successfully enrolled over 40,000 participants. Among these, nearly 20,000 have provided DNA samples, and DNA Methylation (DNAm) data has been obtained from 4018 participants. The study conducts biennial interviews with participants, covering a broad range of variables such as income, employment, disability, physical health and functioning, and cognitive functioning. Further details about the HRS and its survey design can be found elsewhere57.

Analytic sample

The present study utilized a subset of participants from the HRS who had available DNA Methylation data. DNAm assays were conducted on a non-random subsample of 4018 individuals who took part in the Health and Retirement 2016 Venous Blood Study58. The sample is predominantly female (54.3%) with a median age of 66 years, and ages ranging from 50 to 100 years. The sample exhibits racial diversity with 10.0% being non-Hispanic Black, 8.9% Hispanic and 81.1% non-Hispanic White and others. The sample is also socioeconomically diverse as indicated by the educational distribution: less than high school (14.0%), high school/GED (29.9%), some college (25.8%), and college+ (30.3%). More than a third of the sample is obese (44.5%), 11.0% are current smokers, and 44.2% are former smokers. The sample has been weighted to ensure it is representative of the broader U.S. population58.

DNA methylation data

Detailed information on the 2016 Venous Blood Study is provided in the VBS 2016 Data Description58. Blood samples were obtained from willing respondents during in-home phlebotomy visits, ideally scheduled within four weeks of the 2016 HRS core interview. Although fasting was suggested, it was not required. Methylation was assessed using the Infinium Methylation EPIC BeadChip. To ensure a balanced representation of key demographic variables (such as age, cohort, sex, education, and race/ethnicity), samples were randomized across plates, including 40 pairs of blinded duplicates. The correlation for all CpG sites was found to be greater than 0.97 when duplicate samples were analyzed. Data preprocessing and quality control were performed using the minfi package in R. A total of 3.4% of the methylation probes (equivalent to 29,431 out of 866,091) were excluded from the final dataset due to subpar performance, as determined by a detection p-value threshold of 0.01. Following the removal of these probes, samples that failed the detection p-value analysis were identified and removed using a 5% cut-off (minfi), resulting in the exclusion of 58 samples. Any samples that mismatched in sex and any controls (including cell lines and blinded duplicates) were also removed. High-quality methylation data were retained for 97.9% of the samples (n = 4018). Any missing beta methylation values were replaced with the mean beta methylation value of the respective probe across all samples before the construction of DNAm age measures.

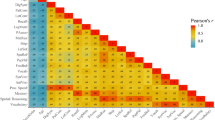

Epigenetic clocks

Thirteen epigenetic clocks were evaluated centrally by the HRS team using the HRS DNAm data. Since these clocks were originally developed using independent datasets, our study serves as a validation of their predictive accuracy for brain health outcomes. These clocks were calculated as a weighted sum of aging-related CpGs, typically ranging from 100 to 500, with weights determined using a penalized regression model. These methylation clocks, which represent epigenetic age, are measured in epigenetic years, with the premise that each tick of the clock signifies aging. Among these thirteen clocks, nine are classified as first-generation clocks, calibrated based on age6,7,8,9,10,40,59,60,61, while the remaining four are second-generation clocks, calibrated on health-related outcomes, namely Zhang12, PhenoAge3, GrimAge11, and MPOA62. These clocks exhibit significant variability in their mean values, ranges, and minimum and maximum ages. Some of the clocks, when expressed in years, have extremely high maximum ages (for example, Lin at 133 and Weidner at 148), while others have very low minimum ages (for example, Lin at 1.9). To create a composite value representing epigenetic age without any a priori selection of the clocks, we standardized them to approximate a normal distribution and took the average of these standardized clocks as our primary measure of epigenetic age. We also report results corresponding to each individual clock.

Genetic data

The genotyping for this study was carried out by the Center for Inherited Disease Research in the years 2011, 2012, and 2015. Detailed information regarding quality control can be accessed in the online Quality Control Report63. Genotype data was collected from over 15,000 HRS participants using the Illumina HumanOmni2.5 BeadChips (HumanOmni2.5-4v1, HumanOmni2.5-8v1), which measures approximately 2.4 million Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). The Genetics Coordinating Center at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA, performed the genotyping quality control. Criteria for removal included individuals with missing call rates exceeding 2%, SNPs with call rates less than 98%, Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium p value less than 0.0001, chromosomal anomalies, and first-degree relatives in the HRS. Imputation to the 1000 Genomes Project Phase I v3 (released March 2012) was conducted using SHAPEIT2 and IMPUTE2. A worldwide reference panel consisting of all 1092 samples from the Phase I integrated variant set was utilized. The Genetics Coordinating Center at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA, performed and documented these imputation analyses. All positions and names are aligned to the GRCh37/hg19 build.

Genetic instruments

We utilized genetic instruments derived from external genome-wide association studies (GWASes) to represent the exposure variables: brain health events for the first stage and epigenetic age for the second stage.

1st stage

Our selection of genetic instruments involved the following sources for stroke, dementia and depression, respectively: the GIGASTROKE consortium’s GWAS of all-cause stroke64, the European Alzheimer & Dementia Biobank consortium’s GWAS of Alzheimer’s disease65, and a meta-analysis of the three largest GWASes of depression66. From each of these studies, we selected SNPs that were biallelic, common (minor allele frequency greater than 5%) and associated with the respective trait (p < 1e-5). To ensure the independence of these SNPs, we filtered out variants with an r2 (a measure of correlation between two genetic variants) greater than 0.1. This resulted in 382 SNPs for stroke, 256 for Alzheimer’s disease, and 462 for depression. These SNPs were combined to yield 1100 instruments associated with either stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, or depression. From this pool, 20 variants were excluded to ensure independence, 75 were not present in the imputed HRS genetic data, and 20 palindromic SNPs were excluded, resulting in a final list of 985 instruments. We then estimated the effect of the genetic instruments on the epigenetic age and on the brain health composite by conducting single-SNP association tests in HRS (Fig. 4). The effect estimates corresponding to epigenetic age were obtained in HRS participants with DNAm and genetic data and the ones corresponding to brain health events were obtained in all HRS participants with genetic data (Fig. 2).

2nd stage

For the second stage, we selected genetic instruments by combining data from multi-ethnic GWASes67 of six epigenetic clocks: GrimAge11, Hannum8, PhenoAge3, Horvath9, PAI-111, and Gran3,11,41. From each of these GWASes, we selected common SNPs (minor allele frequency >5%) associated with the respective epigenetic clock (p < 1e-5). To ensure the independence of these SNPs, we filtered out variants with an r2 greater than 0.1. This yielded 81 SNPs for the GrimAge clock, 84 for the Hannum clock, 104 for the PhenoAge clock, 103 for the Horvath clock, 75 for the PAI-1 clock, and 403 for the Gran clock. These SNPs were combined to obtain a pooled list of 850 SNPs associated with any of the six epigenetic clocks. From this pool, 52 variants were excluded to ensure independence, 6 were not present in the imputed HRS genetic data, and 15 palindromic SNPs were excluded, resulting in a final list of 777 instruments. We then estimated the effect of the genetic instruments on the epigenetic age and on the brain health composite by conducting single-SNP association tests in HRS (Fig. 5).

Ascertainment of brain health events

Stroke

Stroke events were identified as the first instance of stroke in a dedicated variable evaluated throughout the study period (1992–2020), based on self-reported or proxy-reported doctor’s diagnosis (Has a doctor ever told you that you had a stroke?). In cases where participants were unable to be directly interviewed (e.g., deceased), health care proxies were interviewed. Transient ischemic attacks were not systematically assessed and were not classified as strokes, and information on stroke subtype was not available. Previous studies using HRS data have demonstrated that associations between known risk factors and self-reported stroke incidence in the HRS align well with associations in studies using observationally verified strokes68. Moreover, self-reported strokes in the HRS corresponded well with strokes coded according to the International Classification of Diseases in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services records, with a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 93%69.

Dementia

The ascertainment of all-cause dementia among self-respondents was carried out at each wave using the modified version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS): a 27-point cognitive scale that encompasses immediate and delayed 10-noun free recall tests (each with a range of 0–10 points), a serial seven subtraction test (range: 0–5 points), and a backward count from 20 test (range: 0–2 points)70,71. Based on their continuous score, we categorized cognitive status into two groups—those with and without dementia—using observationally verified cutpoints from the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS). A supplemental study of the HRS, ADAMS involves in-home neuropsychological and observational assessments combined with expert clinician adjudication to obtain a gold-standard diagnosis of cognitive status70,72. Respondents with scores ranging from 12 to 27 were classified as non-impaired; those with scores from 7 to 11 were identified as having cognitive impairment but no dementia; and those with scores from 0 to 6 were classified as having dementia. For the purposes of this paper, we focused solely on participants with dementia. A small percentage of respondents (0.8%–3.1%) declined to participate in tests of immediate and delayed recall and serial 7 s. To address this, HRS has developed an imputation strategy for cognitive variables across all waves73.

Late-life depression

Following a common definition from the literature74,75,76,77, we defined late-life depression as a major depressive episode occurring after the age of 65 in an individual with no history of depressive episodes prior to this age. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the validated, modified 8-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale78,79. During each biennial questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate (yes/no) whether they had experienced any of the 8 symptoms in the preceding week. A summary score (ranging from 0 to 8) was compiled by adding the number of affirmative responses across the 8 items, with two positively framed items being reverse-coded78. Major depressive episodes were identified using dichotomized CES-D summary scores for each wave, with a cutoff of ≥4 symptoms. This threshold has been previously validated and is considered equivalent to the 16-symptom cut-off of the well-validated 20-item CES-D scale76,78,80. In our sensitivity analyses, we explored an alternative definition of late-life depression found in the literature, characterized by a lower age cutoff of 60 years, instead of 6581,82,83.

Covariates ascertainment

We collected self-reported demographic and socioeconomic variables at the onset of the Venous Blood Study58, including age (continuous), sex (male or female), and race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic or other). Additionally, we gathered self-reported measures of health behaviors and health conditions at baseline, such as body mass index (continuous, kg/m2 derived from self-reported height and weight), and cigarette smoking status (nonsmoker, former smoker, current smoker). Health conditions were determined based on responses (yes/no) to the question “Has a doctor ever told you that you had a (health condition)?” for heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. Previous studies using HRS data have shown that self-reported health conditions align substantially with medical records data, and that the self-reported health behavioral measures have strong external validity68,84,85,86,87.

Statistical analyses

We describe discrete data as counts (percentages) and continuous data as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. In the first stage of the study, which examined the association between a history of brain health events (exposure) and epigenetic age (outcome), a history of brain health events was defined as having experienced a stroke, dementia, or late-life depression episode ascertained in waves 1 (1992) to 13 (2016). In the second stage of the study, which examined the association between epigenetic age (exposure) and the onset of new brain health events (outcomes), these events were defined as a stroke, dementia, or late-life depressive episode ascertained in waves 14 (2018) or 15 (2020). Participants who did not participate in both of these waves, due to loss to follow-up or death, were excluded from this analysis. Additionally, participants who had experienced brain health events between waves 1 and 13 were also excluded from this phase of the analysis.

In the first stage of our study, we explored the association between a history of brain health events and epigenetic age using multivariable linear regression models. These models were either unadjusted (Model 1), adjusted for potential demographic confounders such as age, sex, and race/ethnicity (Model 2), or adjusted for these demographic factors and cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and body mass index), and comorbidities (history of heart events including heart attack, coronary artery disease, angina, and congestive heart failure, Model 3). In the second stage, we investigated the association between epigenetic age and the risk of new brain health events using multivariable logistic regression models. These models were either unadjusted (Model 1) or adjusted for the same sets of confounders as in the first stage (Model 2 and 3).

Mendelian randomization

In both stages, our primary MR analyses used the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method. In secondary analyses, we tested for horizontal pleiotropy (the possibility that the effect of the instrument on the outcome of interest is exerted through a pathway other than the exposure) using the Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO88) global test with 10,000 simulations and the MR-Egger intercept term89. To account for this possible phenomenon, we implemented the weighted median method, a robust alternative to the IVW method that allows for up to 50% of the genetic variants used to be invalid instrumental variables without biasing the causal effect estimate90. Additionally, the weighted median approach is less sensitive to outliers than the IVW method, which can be useful in the presence of genetic variants with extreme effect estimates26.

Secondary and sensitivity analyses

In our secondary analyses, we repeated the epidemiological analyses for both stages, considering each brain health outcome individually (stroke, dementia, and depression), as well as a composite outcome that included only stroke and dementia. In addition to our main measure, the mean epigenetic age, we also report the association results for each epigenetic clock. We also considered the average of the second-generation clocks, rather than all epigenetic clocks, as an alternative measure of epigenetic age. In our sensitivity analyses, we: (1) tested the association between epigenetic age and the risk of new brain health events, excluding only participants missing data for waves 14 or 15, as opposed to excluding participants missing both waves; (2) repeated both stages using an age cutoff of 60 to ascertain late-life depression.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data generated in this study is available in Supplementary Tables S3-S15. Source data for Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. S1-S4 are provided with this paper.

The HRS longitudinal individual level data are available from HRS and the RAND Center for the Study of Aging (https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/rand). The HRS genome-wide data are available through the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP), accession number phs000428.v2.p2. The HRS DNA methylation data are available by applying for access at https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/data-products/restricted-data. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Observational analyses and plotting were performed using available packages in R 4.2.191: dplyr, stats, ggplot2, ggforestplot, tableone. Genetic analyses including clumping, association testing and all Mendelian Randomization analyses were performed using the Genal 0.992 package in Python 3.9.193. The Genal package and associated code examples are publicly available at https://github.com/CypRiv/genal.

References

Hou, Y. et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 15, 565–581 (2019).

Kelly-Hayes, M. Influence of Age and Health Behaviors on Stroke Risk: Lessons from Longitudinal Studies. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 58, S325–S328 (2010).

Levine, M. E. et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 10, 573–591 (2018).

Zhang, F. F. et al. Physical activity and global genomic DNA methylation in a cancer-free population. Epigenetics 6, 293–299 (2011).

Choi, S. W., Mak, T. S. H. & O’Reilly, P. F. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat. Protoc. 15, 2759–2772 (2020).

Bocklandt, S. et al. Epigenetic Predictor of Age. PLoS One 6, e14821 (2011).

Garagnani, P. et al. Methylation of ELOVL2 gene as a new epigenetic marker of age. Aging Cell 11, 1132–1134 (2012).

Hannum, G. et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 49, 359–367 (2013).

Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14, 3156 (2013).

Weidner, C. I. et al. Aging of blood can be tracked by DNA methylation changes at just three CpG sites. Genome Biol. 15, R24 (2014).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 303–327 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. DNA methylation signatures in peripheral blood strongly predict all-cause mortality. Nat. Commun. 8, 14617 (2017).

G. B. D. 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X (2019).

Vos, T. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Herrman, H. et al. Time for united action on depression: a Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 399, 957–1022 (2022).

Luger, T. M., Suls, J. & Vander Weg, M. W. How robust is the association between smoking and depression in adults? A meta-analysis using linear mixed-effects models. Addict. Behav. 39, 1418–1429 (2014).

Lund, C. et al. Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 357–369 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Dietary patterns and depression risk: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 253, 373–382 (2017).

Schuch, F. B. et al. Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 631–648 (2018).

Alexopoulos, G. S. Mechanisms and treatment of late-life depression. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 188 (2019).

Kuźma, E. et al. Stroke and dementia risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement 14, 1416–1426 (2018).

Farhat, N. S., Theiss, R., Santini, T., Ibrahim, T. S. & Aizenstein, H. J. Neuroimaging of Small Vessel Disease in Late-Life Depression. Adv. Exp. Med Biol. 1192, 95–115 (2019).

Cannistraro, R. J. et al. CNS small vessel disease: A clinical review. Neurology 92, 1146–1156 (2019).

Singh, S. D. et al. Brain health begins with brain care. Lancet Neurol. 21, 961–962 (2022).

Wang, Y., Pan, Y. & Li, H. What is brain health and why is it important? BMJ 371, m3683 (2020).

Burgess, S., Foley, C. N., Allara, E., Staley, J. R. & Howson, J. M. M. A robust and efficient method for Mendelian randomization with hundreds of genetic variants. Nat. Commun. 11, 376 (2020).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Smith, G. D. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 362, k601 (2018).

Quach, A. et al. Epigenetic clock analysis of diet, exercise, education, and lifestyle factors. Aging (Albany NY) 9, 419–446 (2017).

Horvath, S. et al. Obesity accelerates epigenetic aging of human liver. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15538–15543 (2014).

Horvath, S. & Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet 19, 371–384 (2018).

Christiansen, L. et al. DNA methylation age is associated with mortality in a longitudinal Danish twin study. Aging Cell 15, 149–154 (2016).

Marioni, R. E. et al. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 16, 25 (2015).

Chen, B. H. et al. DNA methylation-based measures of biological age: meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging 8, 1844–1865 (2016).

Perna, L. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration predicts cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality in a German case cohort. Clin. Epigenet. 8, 64 (2016).

Levine, M. E., Lu, A. T., Bennett, D. A. & Horvath, S. Epigenetic age of the pre-frontal cortex is associated with neuritic plaques, amyloid load, and Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive functioning. Aging 7, 1198–1211 (2015).

Vidal, L. et al. Specific increase of methylation age in osteoarthritis cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 24, S63 (2016).

Ambatipudi, S. et al. DNA methylome analysis identifies accelerated epigenetic ageing associated with postmenopausal breast cancer susceptibility. Eur. J. Cancer 75, 299–307 (2017).

Levine, M. E. et al. DNA methylation age of blood predicts future onset of lung cancer in the women’s health initiative. Aging 7, 690–700 (2015).

Morales Berstein, F. et al. Assessing the causal role of epigenetic clocks in the development of multiple cancers: a Mendelian randomization study. eLife 11, e75374 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. Correlation of an epigenetic mitotic clock with cancer risk. Genome Biol. 17, 205 (2016).

Horvath, S. & Ritz, B. R. Increased epigenetic age and granulocyte counts in the blood of Parkinson’s disease patients. Aging 7, 1130–1142 (2015).

Marioni, R. E. et al. The epigenetic clock is correlated with physical and cognitive fitness in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 1388–1396 (2015).

Breitling, L. P. et al. Frailty is associated with the epigenetic clock but not with telomere length in a German cohort. Clin. Epigenet. 8, 21 (2016).

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217 (2013).

Kabacik, S. et al. The relationship between epigenetic age and the hallmarks of aging in human cells. Nat. Aging 2, 484–493 (2022).

Feigin, V. L. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20, 795–820 (2021).

Saczynski, J. S. et al. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology 75, 35–41 (2010).

Holmquist, S., Nordström, A. & Nordström, P. The association of depression with subsequent dementia diagnosis: A Swedish nationwide cohort study from 1964 to 2016. PLoS Med 17, e1003016 (2020).

Elser, H. et al. Association of Early-, Middle-, and Late-Life Depression With Incident Dementia in a Danish Cohort. JAMA Neurol. 80, 949–958 (2023).

Towfighi, A. et al. Poststroke Depression: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 48, e30–e43 (2017).

Waziry, R., Chibnik, L. B., Bos, D., Ikram, M. K. & Hofman, A. Risk of hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology 94, 265–272 (2020).

Kitching, D. Depression in dementia. Aust. Prescr. 38, 209–2011 (2015).

Sheehan, N. A. & Didelez, V. Epidemiology, genetic epidemiology and Mendelian randomisation: more need than ever to attend to detail. Hum. Genet 139, 121–136 (2020).

Choi, S. W., Mak, T. S. H. & O’Reilly, P. F. A guide to performing Polygenic Risk Score analyses. Nat. Protoc. 15, 2759–2772 (2020).

Yang, J. H. et al. Loss of epigenetic information as a cause of mammalian aging. Cell 186, 305–326.e27 (2023).

Sonnega, A. et al. Cohort Profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J. Epidemiol. 43, 576–585 (2014).

Fisher, G. G. & Ryan, L. H. Overview of the Health and Retirement Study and Introduction to the Special Issue. Work Aging Retire 4, 1–9 (2018).

Crimmins, E., Faul, J., Thyagarajan, B. & Weir, D. Venous Blood Collection and Assay Protocol in the 2016 Health and Retirement Study.

Horvath, S. et al. Epigenetic clock for skin and blood cells applied to Hutchinson Gilford Progeria Syndrome and ex vivo studies. Aging (Albany NY) 10, 1758–1775 (2018).

Lin, Q. & Wagner, W. Epigenetic Aging Signatures Are Coherently Modified in Cancer. PLoS Genet 11, e1005334 (2015).

Vidal-Bralo, L., Lopez-Golan, Y. & Gonzalez, A. Simplified Assay for Epigenetic Age Estimation in Whole Blood of Adults. Front Genet 7, 126 (2016).

Belsky, D. W. et al. Quantification of the pace of biological aging in humans through a blood test: a DNA methylation algorithm. Published online February, 2020:2020.02.05.927434. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.05.927434.

David, R. Weir. HRS Genetic QC Nov 2021. Accessed July, https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/genetic/HRS-QC-Report-Phase-4_Nov2021_FINAL.pdf (2023).

Debette, S. et al. Stroke genetics informs drug discovery and risk prediction across ancestries. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1175817/v1 (2022).

Bellenguez, C. et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 54, 412–436 (2022).

Howard, D. M. et al. Genome-wide association study of depression phenotypes in UK Biobank identifies variants in excitatory synaptic pathways. Nat. Commun. 9, 1470 (2018).

McCartney, D. L. et al. Genome-wide association studies identify 137 genetic loci for DNA methylation biomarkers of aging. Genome Biol. 22, 194 (2021).

Glymour, M. M. & Avendano, M. Can Self-Reported Strokes Be Used to Study Stroke Incidence and Risk Factors? Stroke 40, 873–879 (2009).

Gilsanz, P. et al. Changes in Depressive Symptoms and Incidence of First Stroke Among Middle‐Aged and Older US Adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4, e001923 (2015).

Crimmins, E. M., Kim, J. K., Langa, K. M. & Weir, D. R. Assessment of Cognition Using Surveys and Neuropsychological Assessment: The Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J. Gerontology: Ser. B 66B, i162–i171 (2011).

Ofstedal, M., Fisher, G., Herzog, A. R., & Herzog A. R. Documentation of Cognitive Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study.

Langa, K. M. et al. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: Study Design and Methods. Neuroepidemiology 25, 181–191 (2005).

Servais, M. Overview of HRS Public Data Files for Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analysis. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; https://doi.org/10.7826/ISR-UM.06.585031.001.05.0023.2010 (2010).

Rodda, J., Walker, Z. & Carter, J. Depression in older adults. BMJ 343, d5219 (2011).

Sekhon, S., Patel J., & Sapra A. Late-Life Depression. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Accessed January 17, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551507/ (2023).

Zivin, K. et al. Depression among older adults in the United States and England. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 18, 1036–1044 (2010).

Alexopoulos, G. S. Depression in the elderly. Lancet 365, 1961–1970 (2005).

Steffick, D. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; https://doi.org/10.7826/ISR-UM.06.585031.001.05.0005.2000 (2000).

Radloff, L. S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 (1977).

Mezuk, B., Bohnert, A. S. B., Ratliff, S. & Zivin, K. Job Strain, Depressive Symptoms, and Drinking Behavior Among Older Adults: Results From the Health and Retirement Study. J. Gerontology: Ser. B 66B, 426–434 (2011).

Randall Espinoza, M. D., Aaron, H. & Kaufman M. D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Late-Life Depression. 2014;31. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/diagnosis-and-treatment-late-life-depression.

Taylor, W. D. Depression in the Elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1228–1236 (2014).

Aziz, R. & Steffens, D. C. What Are the Causes of Late-Life Depression? Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 36, 497–516 (2013).

Fisher, G., Faul, J., Weir, D. & Wallace, R. Documentation of Chronic Disease Measures in the Health and Retirement Study.

Okura, Y., Urban, L. H., Mahoney, D. W., Jacobsen, S. J. & Rodeheffer, R. J. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57, 1096–1103 (2004).

Wallace, R. B. & Herzog, A. R. Overview of the Health Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. J. Hum. Resour. 30, S84–S107 (1995).

Jenkins K., Ofstedal M., Weir D., Weir D. Documentation of Health Behaviors and Risk Factors Measured in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS/AHEAD).

Verbanck, M., Chen, C. Y., Neale, B. & Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet 50, 693–698 (2018).

Burgess, S. & Thompson, S. G. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 32, 377–389 (2017).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 40, 304–314 (2016).

Team RDC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Published online http://www.R-project.org/ (2012).

Rivier, C. A. et al. Genal: A Python Toolkit for Genetic Risk Scoring and Mendelian Randomization. Published online May 2024:2024.05.23.24307776. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.23.24307776.

Van Rossum G., & Drake F. L. Python 3 Reference Manual. CreateSpace; 2009.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the HRS study participants. HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. C. Rivier is supported by the AAN/AHA Ralph L. Sacco Scholars Fellowship (https://doi.org/10.58275/AHA.24RSSPOST1328228.pc.gr.197089). N. Szejko received grants from the Polish Neurological Society, Polish Ministry of Health, Medical University of Warsaw, Tourette Association of America, American Brain Foundation and American Academy of Neurology. S. Huo receives funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG, 514143076). S. Clocchiatti-Tuozzo is funded by NIH T32 AG019134 and together with T.M. Gill are funded by P30 AG021342. K.N. Sheth is supported by the NIH (R03NS112859, R01NS110721, R01NS075209, U01NS113445, U01NS106513, R01NR01833, U24NS107215, and U24NS107136) and the American Heart Association (17CSA33550004, 817874) and reports grants from Hyperfine, Biogen, and Astrocyte unrelated to this work. G.J. Falcone is supported by the NIH (P30AG021342), the American Heart Association (817874), and the Yale Pepper Pilot Award (P30AG021342). A. de Havenon reports NIH/NINDS funding (K23NS105924, R01NS130189, UG3NS130228).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: C.R., N.S. and G.F.; development of methodology: C.R., N.S., H.Z., K.S. and G.F.; acquisition of data: C.R., N.S., K.S. and G.F.; analysis and interpretation of data: C.R., N.S., D.R., S.C., S.H., T.G., K.S. and G.F.; writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: C.R., A.H., H.Z., T.G., K.S., and G.F. with input from all authors; and study supervision: K.S. and G.F.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Luigi Ferrucci and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rivier, C.A., Szejko, N., Renedo, D. et al. Bidirectional relationship between epigenetic age and stroke, dementia, and late-life depression. Nat Commun 16, 1261 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54721-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54721-0