Abstract

The global incidence of obesity-related metabolic disorders and their comorbidities continue to increase along with a demand for innovative therapeutic interventions. An in-depth understanding of de novo thermogenic adipogenesis is vital to harness the potential of these adipocytes. Here, we combine genetic lineage tracing and single-nucleus RNA sequencing to demonstrate that adult adipose-resident c-kit+ cells are previously unidentified brown adipocyte progenitor cells (APCs). c-kit+ APCs differentiate into brown adipocytes but not white adipocytes in adipose tissue homeostasis as well as in cold exposure-, high-fat diet (HFD)- and aging-induced adipose remodeling. More importantly, the vital role of c-kit+ APCs in the generation of brown adipocytes is indicated by decreased brown fat, impaired thermogenic capacity, and excessive fat accumulation in c-kit mutant mice of both genders. In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that adult c-kit+ APCs give rise to brown adipocytes which are responsible for fat homeostasis and remodeling. Thus, c-kit+ progenitors may be an innovative and crucial target for obesity and metabolic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Body fat or adipose tissue, which regulates systemic energy consumption and expenditure, plays a predominant role in obesity. There are three types of adipose tissue, namely, white adipose tissue (WAT), brown adipose tissue (BAT), and beige adipose tissue, which possess diverse functional properties1,2. Recently, studies on brown adipocytes have been reinvigorated due to their whole-body energy expenditure properties and significant correlation with metabolic health and diseases. In adult humans, there are substantial deposits of BAT that correlate with leanness and a metabolically healthy phenotype3,4. The human fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) variant, which represses adipocyte thermogenesis, is strongly associated with obesity5. Thermogenic adipocytes derived from human capillary networks affect systemic glucose tolerance and improve metabolic homeostasis6. Because increasing evidence suggests that brown fat has critical natural roles in human metabolism, augmenting the mass and/or activity of brown adipose in humans may be a promising therapeutic approach to combat obesity and other metabolic diseases2,7.

The number of adipocytes in humans is set during childhood and mostly constant in adulthood8. However, remarkable turnover (~10% annually) of adipocytes in all adult ages has been observed, indicating steady adipogenesis to replace apoptotic fat cells throughout adulthood8. Therefore, the understanding of adult thermogenic adipogenesis is of great importance. Studies have revealed that the initial development of adipose depots during the fetal and early postnatal period relies on precursors distinct from those that contribute to tissue maintenance and remodeling in adulthood9,10. In recent years, fate-mapping studies have aided in the advancement of understanding the origin of adipose tissue during development7. Nevertheless, adult brown adipose expansion is still poorly understood. It is believed that adult adipose-resident precursors or preadipocytes give rise to brown adipocytes. However, recent studies have suggested that the origin and identity of adipocytes are complex11. Recent inducible genetic lineage tracing techniques and single-cell sequencing experiments have shed light on the origin and cell fate of brown adipocytes during adulthood. Elucidating how adult adipocytes turnover and their response during adulthood is pivotal to promote or attenuate their expansion.

c-kit is a well-known stem and progenitor cell marker. However, the biological features of adipose-resident c-kit+ cells and whether these cells are adipose progenitor cells (APCs) are unknown. Interestingly, a retrospective analysis has discovered that patients with chronic myeloid leukemia significantly gain weight after receiving imatinib therapy, which inhibits c-kit function12, thereby suggesting a correlation between c-kit signaling or c-kit+ cells and body fat. This correlation merits further investigation.

In the present study, we investigated the role of adipose-resident c-kit+ cells in adult pathophysiological adipogenesis. We crossed the Kit-CreER line with the Rosa26-RFP reporter line to generate Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice for inducible and irreversible labeling of c-kit+ cells and their progeny13. Using Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), we identified adipose-resident c-kit+ cells as thermogenic adipose progenitors that differentiate into brown adipocytes but not white adipocytes in fat tissue homeostasis and remodeling. Moreover, inhibition of c-kit reduced brown adipogenesis and promoted obesity. Thus, manipulation of c-kit+ APCs may be an innovative and crucial therapeutic strategy for obesity and metabolic diseases.

Results

Adipose-resident c-kit+ cells are previously unidentified adipose progenitors

To characterize the adipose-resident c-kit+ cells, we performed snRNA-seq on classic interscapular brown adipose tissues (iBAT) isolated from adult mice housed at 4 °C for 4 weeks. Using a standard workflow in Seurat, we assigned the cells into distinct cell clusters based on gene expression profiles. This unbiased clustering identified c-kit+ cells, platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα)+ APCs, two pre-brown adipocyte clusters (Pre-BAs-1, and Pre-BAs-2), four brown adipocyte clusters (BAs-1, BAs-2, BAs-3, and BAs-4), four endothelial cell clusters (ECs-1, ECs-2, ECs-3, and ECs-4), immune cells, PDGFRβ+ mural cells, neural cells, and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (Fig. 1A, B). Of note, a unique cluster of cells expressing c-kit was verified by snRNA-seq, and transcriptional profile analysis revealed that c-kit+ APCs were distinct from previously identified thermogenic APCs, including PDGFRα+ APCs and TRPV1+ APCs. The c-kit+ APCs had the following expression signature: high level of Kit and Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 (Erbb4); medium level of EBF transcription factor 2 (Ebf2); low level of CD34 and lymphocyte antigen 6a (Ly6a); and extremely low level of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (Dpp4) and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (Trpv1) (Fig. 1C). Notably, Gene Ontology analysis of the transcripts in the c-kit high-expressing cluster displayed significant enrichment for brown fat cell differentiation, response to nutrient levels, positive regulation of cold-induced thermogenesis, fatty acid metabolic process, and response to mitochondrial depolarization, which demonstrated the potential and commitment of c-kit+ APCs differentiating to thermogenic adipocytes under cold stimulation (Fig. 1D). Consistently, we re-analyzed the data from published scRNA/snRNA-seq of BAT at different temperature exposure14 (Fig. S1A) and found that c-kit+ cell cluster existed in the BAT which was different from previously identified APCs (Fig. S1B, C). These results showed that adipose-resident c-kit+ progenitors are novel APCs distinct from other populations and have committed differentiation potential to thermogenic adipose cells.

A t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plot of cell nuclei isolated from iBAT of Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice after exposure to cold temperature for 4 weeks after tamoxifen (Tam) administration, showing 16 subpopulations. B Bubble plots showing expression levels and distributions of representative transcripts for the selected genes among different cell clusters. The dot size represents the percentage of cells that expressed the gene, and the color represents the scaled value of the average expression level of gene X in cluster Y. The average expression levels of genes are calculated by normalization of the transcriptome data (gene sequence reads by a factor of 10,000, with log-transformed). C Violin plots showing expression levels of representative transcripts for adipose progenitor marker genes, including Pdgfrα, Kit, Cd34, Ly6a, Dpp4, Trpv1, Ebf2, and Erbb4 in c-kit+ APCs and PDGFRα+ APCs. D Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of the transcripts significantly upregulated by cold stimulation in c-kit+ adipocyte progenitors.

Lineage trajectory of c-kit+ cells in adipogenesis revealed their commitment to brown adipocytes

To depict the trajectory of c-kit+ progenitor differentiation into brown adipocytes during cold exposure, we further analyzed c-kit+ APCs as well as the Pre-BAs (Pre-BAs-1, Pre-BAs-2) and BAs (BAs-1, BAs-2, BAs-3, and BAs-4 clusters) among the populations of iBAT from Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice after tamoxifen (Tam) induction and cold stimulation (Fig. 2A). Intriguingly, the snRNA-seq gene expression profiles indicated heterogeneity of brown adipose cells. Pre-BAs-1 and Pre-BAs-2 exhibited expression of transcriptional factors or regulators for brown adipogenesis, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Pparg), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (Ppara), Pparg coactivator 1α (Ppargc1a), and PR domain containing 16 (Prdm16), but an extremely low level of UCP1 (Fig. 2B). BAs, including BAs-1, BAs-2, BAs-3, and BAs-4 clusters, commonly expressed UCP1, and showed functional diversity with different gene profile features. The BAs-1 displayed high expression of adipogenic transcriptional factors (such as Pparg, Ppara, Ppargc1a, Prdm16), moderate expression of genes responsible for lipolysis and fatty acid metabolism (such as elongation of very long chain fatty acid-like family member 6 (Elovl6), lipase E (Lipe), patatin like phospholipase domain containing 2 (Pnpla2), and patatin like phospholipase domain containing 3 (Pnpla3)), and low expression of genes related to thermogenesis and mitochondrial functions (such as UCP1, cytochrome c oxidase subunit 7A1 (Cox7a1), and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 8B (Cox8b)) (Fig. 2B). The BAs-2, BAs-3 and BAs-4 clusters showed low level of adipogenic transcriptional factors, and were distinguished by specific gene expression patterns of fatty acid metabolism and thermogenesis (Fig. 2B). It was noteworthy to mention that the BAs-4 cluster exhibited the highest level of genes associated with thermogenesis including UCP1. The BAs-2 presented a medium level of UCP1 and cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector A (Cidea). Meanwhile, the BAs-3 was enriched by UCP1, Cox7a1, and Cox8b, representing active mitochondrial functions. Lineage trajectory and pseudotemporal analysis predicted the majority of c-kit+ APCs to be the origin of the differentiating brown adipocytes (Fig. 2C, D), from c-kit+ APCs to Pre-BAs to BAs. RFP could be used to label c-kit+ cells and all their progeny in Tam-treated Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice (Fig. S2A, B). Importantly, RFP-labeled cells were identified in c-kit+ APCs as well as in the Pre-BAs-1, Pre-BAs-2, BAs-1, BAs-2, BAs-3 and BAs-4 clusters (Fig. 2E) with approximate percentages of 90%, 40%, 22%, 23%, 5%, 4%, and 20%, respectively (Fig. 2F). The distribution of RFP+ cells in the lineage trajectory of c-kit+ APCs, Pre-BAs, and BAs confirmed the self-renewal of c-kit+ APCs and the conversion of c-kit+ APCs to brown adipocytes (Fig. 2G).

A tSNE plot of c-kit+ APCs, two subpopulations of pre-brown adipocytes (Pre-BAs-1 and Pre-BAs-2 clusters), and four subpopulations of brown adipocytes (BAs-1, BAs-2, BAs-3, and BAs-4 clusters). B tSNE plots showing the distribution and expression of the indicated genes (Pparg, Pparα, Ppargc1α, Prdm16, Elovl6, Lipe, Pnpla2, Pnpla3, Ucp1, Cidea, Cox7a1, and Cox8b) across these cell clusters. C Trajectory analysis was performed to determine the significant transitional relationships among the c-kit+ APCs, Pre-BAs-1, Pre-BAs-2, BAs-1, BAs-2, BAs-3, and BAs-4 clusters. D Pseudotime curves were calculated for the c-kit+ APCs, Pre-BAs, and BAs, indicating the contribution of c-kit+ APCs to brown adipogenesis. E Distribution of RFP expression in c-kit+ APCs, as well as the Pre-BAs and BAs clusters within the tSNE plot. F Quantitation of the percentage of RFP+ cells in c-kit+ APCs and the two subpopulations of pre-brown adipocytes and four subpopulations of brown adipocytes. G Distribution of RFP+ cells in the lineage trajectory of c-kit+ APCs, Pre-BAs, and BAs.

Moreover, to investigate the role of c-kit+ APCs in WAT, we further analyzed snRNA-seq gene expression in pgWAT of Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice after Tam induction. The data showed that there were PDGFRα+ APCs, endothelial cells, pericytes, neural cells, immune cells, and adipocytes in WAT, but almost no c-kit+ APCs (Fig. S3A, C). RFP+ cells were hardly found in adipocytes and APCs of WAT (Fig. S3D), suggesting there are no c-kit+ APC-derived white adipocytes.

Collectively, these data demonstrated that c-kit+ APCs are brown adipocyte precursors that can differentiate to preadipocytes, early-phase brown adipocytes with enhanced capacity of thermogenic substrate metabolism, and eventually specialized thermogenic brown adipocytes.

c-kit+ progenitors can differentiate into mature brown adipocytes

To investigate whether c-kit+ APCs can give rise to brown adipocytes, we isolated the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of iBAT from Tam-treated Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice and cultured them to differentiate into brown adipocytes. First of all, we verified the no leaky of RFP in Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice, evidenced by undetected RFP fluorescence signals from 20-week and 100-week-old mice without Tam (Fig S4). To verify the cell identity of RFP-labeled cells, we performed one pulse administration of Tam and immunostaining of the iBAT at day 0 after Tam administration. Data showed that RFP marked c-kit+ APCs (c-Kit+UCP1−) as well as a few c-kit+ brown adipocytes (c-Kit+UCP1+) (Fig. S5A). Additionally, a complete strategy of four times of Tam administration to fully induce Cre recombinase activity was performed, and iBAT was collected 2 weeks later (Fig. 3A). Expectedly, we found RFP-labeled c-kit+ APCs in the SVFs of iBAT via immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 3B). Then, SVFs of iBAT from Tam-treated Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice were isolated by discarding mature adipocytes and cultured in vitro (Fig. 3A). Coimmunostaining of the isolated stromal cells showed that RFP+ cells were c-kit+ APCs (Fig. 3C), but not smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, adipocytes, immune cells, PDGFRα+ APCs, or PDGFRβ+ mural cells in the SVFs (Fig. S5B). After inducing the stromal cells to mature brown adipocytes, co-immunofluorescence staining showed a tremendous amount of RFP+BODIPY+ cells, demonstrating the c-kit lineage brown adipocytes (Fig. 3D). Additionally, we added ACK2, a c-kit blocking antibody, in SVF cells for inhibition of c-kit. Co-immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 3E) and quantitative analysis (Fig. 3F) showed dramatically decreased RFP positive adipocytes after ACK2 treatment. These in vitro data revealed that the c-kit+ APCs from SVFs of iBAT could differentiate into brown adipocytes.

A Schematic of the Tam induction strategy for Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice, and isolation of the stromal vascular fraction for culture and differentiation into brown adipocytes. Partial elements created in BioRender. Yang, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/x6xcmbq. B Representative immunofluorescence staining with RFP and UCP1 indicates the presence of c-kit+ APCs in the stromal vascular fraction of iBAT. Scale bar = 100 μm, n = 6 mice. C Representative images of stromal cells double-stained for c-Kit and RFP, Scale bar = 50 μm. D Representative images of brown adipocytes double-stained for BODIPY and RFP, Scale bar = 50 μm. C, D Each experiment was independently reproduced at least 3–4 times. E Representative images of control and ACK2-treated brown adipocytes double-stained for BODIPY and RFP, Scale bar = 50 μm. F Quantitative analysis of RFP+ BODIPY + cells. Each dot indicates a value from one cell experiment, n = 6. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (Control versus ACK2).

c-kit+ progenitors contribute to brown adipocytes but not white adipocytes in fat homeostasis

To evaluate the cell fate of c-kit+ progenitors in adipose tissue homeostasis, classic iBAT, iBAT that interfaces interscapular white adipose tissue (iBAT/iWAT), and perigonadal white adipose tissue (pgWAT) were collected from 20- and 50-week-old Tam-treated Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice for lineage tracing analysis (Fig. 4A). RFP expression was detected in iBAT and iBAT/iWAT but not in pgWAT from Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice at 10 weeks after treatment with Tam. Coimmunostaining of RFP and UCP1 or perilipin (PLIN) showed that the c-kit+ cell progeny were brown adipocytes (Figs. 4B, C and S6A, B) but not white adipocytes (Figs. 4D and S6C). More importantly, the numbers of RFP+ brown adipocytes were significantly increased in iBAT and iBAT/iWAT from mice at 40 weeks after Tam induction compared to that from mice at 10 weeks after Tam treatment (Figs. 4E, F and S6D, E). Moreover, RFP expression could hardly be observed in pgWAT at 40 weeks after Tam induction (Figs. 4G and S6F). Noteworthy, conspicuous differences could be observed on the iBAT/iWAT sections wherein there were abundant RFP+ adipocytes in the brown adipose area in contrast to the scarcity of RFP+ adipocytes in the white adipose region. Taken together, these data demonstrated that c-kit+ progenitor cells can massively expand and give rise to brown adipocytes but not white adipocytes in fat cell turnover and tissue homeostasis.

A Schematic depicting the experimental procedures. Ten-week-old Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice were administered with Tam, and different adipose tissues were collected at 10 and 40 weeks after Tam treatment, respectively, for analysis. B–G Classic interscapular brown adipose tissue (iBAT), iBAT that interfaces with interscapular white adipose tissue (iBAT/iWAT), and perigonadal white adipose tissue (pgWAT) were collected for immunofluorescence staining of the red fluorescent protein (RFP) lineage marker and the uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) thermogenic marker, n = 6 mice/group. At 10 weeks post-Tam treatment, RFP+UCP1+ cells were observed in iBAT (B) and iBAT/iWAT (C), whereas few RFP+UCP+ cells were observed in pgWAT (D). At 40 weeks post-Tam treatment, more RFP+UCP1+ cells were observed in iBAT (E) and iBAT/iWAT (F) but not in pgWAT (G). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Dynamic recruitment of c-kit+ progenitor-derived brown adipocytes is involved in pathophysiological adipose remodeling

Fat tissue undergoes dynamic remodeling, including quantitative and qualitative changes, in response to different physiological or nutritional cues. To test whether c-kit+ cells generating adipocytes are functionally involved in fat remodeling, we utilized Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice to trace the fate and number of c-kit progeny during cold exposure-, high-fat diet (HFD)-, and aging-induced adipose tissue alterations.

After Tam treatment, Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice were housed at 4 °C for 4 weeks, and classic brown (iBAT), beige (inguinal subcutaneous white adipose tissue, ingWAT), and white (pgWAT) adipose tissue were analyzed (Fig. 5A). Cold exposure led to more multilocular morphology of brown and beige fat (Fig. 5B). Intriguingly, prolonged cold exposure significantly increased the percentage of RFP+ brown adipocytes in iBAT with percentages of 13.35% in the cold group and 7.28% in the room temperature (RT; 22 °C) group (Fig. 5C). Moreover, there was a significant increase in RFP+ beige adipocytes in ingWAT in the cold group compared to the RT group (Fig. 5D). In contrast to classic brown and beige adipose tissue, RFP+ adipocytes were not detected in cold-stimulated pgWAT (Fig. S7A), which suggested that white adipocytes did not originate from c-kit+ cells.

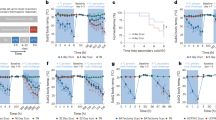

A Schematic depicting the experimental procedure for the exposure of Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice to cold temperature (4 °C) or to room temperature (RT; 22 °C) for 4 weeks after Tam treatment. B Representative H&E staining of adipose tissue sections of iBAT and ingWAT depots in the cold and RT group, n = 6 mice/group. C-D Immunofluorescence (IF) staining of tissue sections of iBAT (C) and ingWAT (D) for RFP and UCP1. Quantitative analysis showing cold exposure increased the percentages of RFP+UCP1+ cells both in iBAT (C) and ingWAT (D). C, D Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 6 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (RT versus Cold). E Schematic illustrating Tam-induced Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice fed on a high-fat diet (HFD) or chow diet (Control) for 16 weeks. F H&E staining of adipose tissue sections of iBAT and ingWAT depots from control and HFD mice, n = 6 mice/group. G-H Representative IF images of iBAT (G) and ingWAT (H) tissue sections double-stained for RFP and UCP1. Quantitative analysis indicating that HFD significantly reduced the proportion of RFP+UCP1+ cells in iBAT (G). RFP+UCP1+ cells were scarcely observed in ingWAT (H) in both the control and HFD mice. G Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 8 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (Control versus HFD). H Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 7 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (Control versus HFD). I Graph representing adipose tissues was collected for analysis from Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice at 10 weeks, 40 weeks, 70 weeks, and 100 weeks after Tam treatment. J Quantitation of RFP+UCP1+ cells in iBAT at different ages. Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 4 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (Tam 40 w versus Tam 70 w; Tam 70 w versus Tam 100 w). Scale bar = 100 μm. K Representative images of iBAT tissue sections double-stained for RFP and UCP1 at indicated time points.

We next hypothesized that whitening of thermogenic fat during obesity-related metabolic remodeling diminishes the recruitment of thermogenic adipocytes from c-kit+ progenitors. To test this hypothesis, Tam-treated Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice were fed with an HFD for 16 weeks (Fig. 5E), which resulted in more unilocular and larger lipid droplets in brown and beige adipocytes (Fig. 5F). As expected, the proportion of RFP+UCP1+ adipocytes in iBAT (1.75%) was significantly reduced in HFD-fed mice compared to control mice (11.75%) (Fig. 5G). In addition, RPF+ adipocytes could hardly be observed in ingWAT (Fig. 5H) or pgWAT (Fig. S7B) during HFD-induced remodeling.

Considering the enhanced number of c-kit-derived brown adipocytes from young to mid-age adults, we next investigated how these cells change during aging by collecting iBAT from Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice at 10, 40, 70, and 100 weeks after Tam treatment for analysis (Fig. 5I). Notably, the number of RFP+UCP1+ adipocytes was low in iBAT obtained from mice at 10 weeks after Tam, but it increased in iBAT at 40 weeks after Tam treatment. Moreover, the number of RFP+UCP1+ adipocytes gradually attenuated with age as indicated by coimmunostaining of fat obtained from mice at 70 weeks and 100 weeks after Tam treatment (Fig. 5K). Quantification of labeled cells verified that 3.66% of UCP1+ cells adopted a c-kit lineage at Tam-10w and that 54.95% of UCP1+ cells adopted a c-kit lineage at Tam-40w. However, the percentage of c-kit-derived brown adipocytes gradually decreased with age, with values of 30.5% and 22.25% at 70 and 100 weeks after Tam treatment, respectively (Fig. 5J).

Overall, these data suggested that c-kit+ progenitors convert to thermogenic brown adipocytes but not white adipocytes, and this conversion may be promoted by cold exposure and diminished by overnutrition. More importantly, c-kit+ progenitors are more likely to be impaired in brown adipogenesis during aging and may be partially responsible for age-related obesity.

c-kit inhibition results in obesity and reduced brown adipogenesis

To further investigate whether c-kit affects thermogenic adipocytes and fat depot expansion during adulthood, we utilized KitW/+ mice, which carry a spontaneous mutation at the Kit locus and have a white spotted belly and impaired c-kit function. We monitored chow diet-fed c-kit+/+ and c-kitW/+ mice over the course of 80 weeks. The body weight of 15-week-old c-kitW/+ mice was similar to that of c-kit+/+ mice, but the body weight of 20-week-old c-kitW/+ mice was significantly increased compared to that of c-kit+/+ mice. This weight difference was maintained as the mice aged (Fig. 6A, B). The increased body weight of c-kitW/+ mice was accompanied by an increase of fat mass but not lean mass (Fig. 6C). More importantly, compared to c-kit+/+ mice, c-kitW/+ mice had less thermogenic adipose tissue as indicated by lower standardized uptake values in the BAT region and a significantly lower percentage of detected BAT radiation (Fig. 6D). Additionally, the iBAT and ingWAT in c-kitW/+ mice had significantly fewer multilocular adipocytes and larger lipid droplets in the cytoplasm than c-kit+/+ mice, and the pgWAT in c-kitW/+ mice had larger lipid droplets compared to c-kit+/+ mice (Fig. 6E).

A Representative photograph of 50-week-old c-kit+/+and c-kitw/+ mice. B Body weights of c-kit+/+and c-kitw/+ mice over 80 weeks on a standard chow diet. Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 9–14 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice). C The body compositions of c-kit+/+and c-kitw/+ mice were detected by a Body Composition Analyzer. Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 8 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice). D Representative PET-CT images of mice after a cold challenge study for 4 h at 4 °C and quantitative analysis of the 18FDG uptake in BAT as indicated by the percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 5 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice). E Adipose tissue sections from iBAT, ingWAT, and pgWAT of c-kit+/+and c-kitw/+mice were collected and stained with H&E (left). Quantitative analysis of the lipid droplet surface of stained adipose tissue sections (right). Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 4 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice). F Schematic of the experimental procedure for Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice with localized inhibition of c-kit by intra-iBAT injection of IgG control or ACK2 and exposure to cold temperature (4 °C) for 2 weeks. Partial elements created in BioRender. Yang, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/90iw46s. G Immunofluorescence staining of the tissue sections of iBAT for RFP and UCP1 (left). Quantitative analysis showed local injection of ACK2 decreased the percentages of RFP+UCP1+ cells in iBAT (right). Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 8 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice). H The weight of different adipose tissues. Each dot indicates a value from one mouse, and n = 15–16 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice). I Relative mRNA level of browning genes in iBAT in mice treated with Control and ACK2. Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 7-11 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice). J Rectal temperature in mice treated with Control and ACK2. *P < 0.05 (c-kitw/+ versus c-kit+/+ or ACK2 versus Control). Each dot indicates a value from one mouse and n = 8 mice/group. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (c-kit+/+ mice versus c-kitw/+ mice).

To find out whether c-kit mutation affects cold-induced brown adipogenesis and thermogenesis at an age before the onset of the obese phenotype, 8-week-old c-kit+/+ mice and c-kitW/+ mice were investigated. First of all, there was no significant difference in the size and mean surface area of lipid droplets in iBAT between c-kit+/+ mice and c-kitW/+ mice at RT without stimulation (Fig. S8A). Then, the mice were housed at 4 °C for 2 weeks (Fig. S8B). HE staining revealed that compared to c-kit+/+ mice, c-kitW/+ mice exhibited significantly fewer multilocular adipocytes in iBAT, ingWAT, and pgWAT, with larger cytoplasmic lipid droplets (Fig. S8C). The iBAT mass of c-kitW/+ mice was significantly reduced relative to c-kit+/+ mice, while no significant differences were detected in ingWAT or pgWAT mass (Fig. S8D). Furthermore, quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that the mRNA expression levels of browning markers (Ucp1, Cidea, Cox7a, Cox8b, Elovl3, and Pparg) in iBAT were significantly decreased in c-kitW/+ mice (Fig. S8E). Critically, we observed lower core body temperatures in c-kitW/+ mice, indicating impaired thermogenic capacity in c-kitW/+ mice upon cold exposure (Fig. S8F).

Subsequently, we conducted localized inhibition of c-kit by intra-iBAT injection of ACK2 in Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice with cold exposure after Tam induction (Fig. 6F). Immunostaining showed that the number of RFP+UCP1+ adipocytes in iBAT with ACK2 injection (4.66%) was significantly attenuated compared to control mice (15.17%) (Fig. 6G). The weight of iBAT in the ACK2-treated group was lower than that in the control group (Fig. 6H). Furthermore, the mRNA expression of browning markers, including Ucp1, Cidea, Cox7a, Cox8b, Elovl3, and Pparg, was decreased in the iBAT of ACK2-treated mice (Fig. 6I). More importantly, we found that the rectal temperature, which indicates the overall thermogenesis of BAT, was significantly lower in the ACK2-treated group compared to the control group (Fig. 6J). These results revealed that localized inhibition of c-kit+ APCs in BAT reduced brown adipogenesis and thermogenesis.

In summary, the current findings demonstrated that both systemic and local inhibition of c-kit cause decreased thermogenesis and fat remodeling, which is attributed to, at least partially, impaired brown adipogenesis.

Discussion

In the present study, we combined genetic lineage tracing and single-nucleus RNA sequencing to provide an unprecedented view that adult adipose-resident c-kit+ cells are previously unidentified brown adipocyte progenitors. Endogenous c-kit+ APCs and their progeny give rise to brown adipocytes but not white adipocytes in adult fat cell turnover and homeostasis. Cold exposure promotes c-kit+ APC differentiation to brown adipocytes, while overnutrition attenuates this process. Moreover, c-kit+ APCs are more likely to be impaired in brown adipogenesis during aging and may be partially responsible for age-related obesity. The vital role of c-kit+ APCs in the generation of thermogenic adipocytes is indicated by decreased brown fat and excessive fat accumulation in c-kit mutant mice. Thus, adipose-resident c-kit+ APCs are indispensable regulators in adult thermogenic adipogenesis and adipose tissue remodeling, thereby providing an innovative and crucial target for obesity and metabolic diseases.

The origin of thermogenic adipocytes remains controversial. Previous studies have identified Myf5+Pax3+En1+ cells as fetal brown adipose precursors2, but research focusing on adult brown and beige adipogenesis is scarce. Studies on the growth of adipose depots have consistently suggested that de novo adipogenesis occurs in close proximity to the vasculature, but the exact nature and identity of these progenitors have remained unclear11. For de novo brown adipogenesis, genetic lineage tracing models have demonstrated that cold exposure induces PDGFRα+ progenitors to proliferate and differentiate into brown adipocytes15. Recently, scRNA-seq of BAT stromal vascular cells from mice, followed by lineage trajectory analysis, has revealed that Trpv1+ cells proliferate upon cold exposure and differentiate into brown adipocytes14. Fat-mapping analyses have suggested that adult beige fat biogenesis involves both de novo differentiation from progenitors and reinstatement of thermogenic activity in white adipocytes16. Oguri et al.17 employed scRNA-seq to define a unique subset of adipose progenitors, characterized by PDGFRα, Sca-1, and CD81, which give rise to beige fat. In the present study, we identified a novel brown adipocyte progenitor that is distinct from PDGFRα+ and Trpv1+ APCs. Of note, both PDGFRα+ APCs and Trpv1+ APCs differentiate into white adipocytes under pathophysiological conditions14,18. However, very few c-kit lineage-derived white adipocytes were found under physiological turnover or HFD-induced white adipogenesis, suggesting that c-kit+ APCs are a better and more specialized target for promoting thermogenic adipogenesis compared to other known APCs. More importantly, we observed up to 50% of UCP1+ thermogenic cells arising from c-kit+ APCs in middle adulthood, indicating the principal and significant role of c-kit+ APCs in thermogenic adipogenesis.

Fat tissue is dynamically remodeled in response to various physiological or nutritional cues. Chronic cold facilitates de novo adipogenesis of brown adipocytes from APCs, while overnutrition attenuates this process. As expected, c-kit+ APCs, similar to previously identified APCs, were provoked under cold conditions to differentiate into brown adipocytes. Interestingly, the number of c-kit lineage-derived thermogenic adipocytes increased at an early age but significantly decreased in older mice. Previous research has found that age-induced impairment of brown APC function contributes to the loss of brown adipocyte regeneration, thereby promoting the development of obesity and other metabolic disorders with age19. In addition, several studies have reported that aging negatively impacts brown fat biogenesis20,21. A recent single-cell RNA sequencing analysis has also revealed that the proliferation of a subpopulation of adipogenic progenitors declines with aging17. The present data suggested that c-kit+ APCs are susceptible to aging and are more vulnerable than other APCs. The impairment of c-kit+ APCs is responsible, at least in part, for the age-related decreased thermogenic adipogenesis, but it remains unknown whether it is caused by reduced self-proliferation or decelerated de novo differentiation. Additionally, the underlying mechanism of c-kit+ APCs in aging merits further investigation.

Recently, Lee et al. reported that BAs could express c-kit, and c-kit+ BAs were transiently increased in the first week after denervation or thermoneutrality of BAT, but not by thermogenic activation, including cold exposure22. Although using the same Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice, our Tam induction strategy is completely different from Lee’s study. We label all the c-kit+ cells under physiological state by administering Tam four times and allowing 2 weeks of washout to ensure that the Tam is eliminated and does not label cells with newly acquired c-kit expression, and then trace c-kit+ cells division or conversion. In contrast, Lee et al. perform Tam induction alongside the stimulation (denervation or thermoneutrality), resulting in labeling of cells with elevated c-kit expression during stimulation. The different strategies account for distinct address of the distinct biology of c-kit and c-kit+ cells associated with BAs. Lee et al. elucidate the function of c-kit signaling in BAs, while we provide evidence discovering the cell fate of c-kit+ APCs. In our system of Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice tracing models, it is possible that RFP-labeled pre-existing mature BAs, in addition to c-kit+ APCs after Tam induction. However, the substantial expansion of RFP+ adipose cells in BAT adapted to RT for a year or cold for a month can’t be derived from BAs, since mature BAs can hardly divide and proliferate. Furthermore, in vitro culture of SVF cells, which were removed from adipocytes, confirms the potential of c-kit+ APCs differentiation into BAs. The existence of c-kit+ APCs and the function of c-kit signaling in lipogenesis of mature BAs suggest a comprehensive and critical role of c-kit in BAT homeostasis and remodeling.

Noteworthy, while murine models lack direct evidence of mature adipocyte proliferation to date, emerging studies in humans unexpectedly displayed that terminally differentiated adipocytes are able to reenter the cell cycle, which correlates with endoreplication and adipocyte hypertrophy under obesity and hyperinsulinemia23. Despite this study providing nice evidence to show cell cycle reentry, comprehensive evidence to support proliferation and mitosis of mature adipocytes is still missing23. However, the observed cell cycle progression does imply that mature adipocytes may theoretically retain the potential to proliferate and divide under specific conditions. Therefore, although our data strongly suggest that RFP-labeled brown adipocytes arise from the differentiation of c-kit+ progenitor cells, we cannot entirely rule out the potential contributions of pre-existing RFP-labeled adipocytes to the final RFP-labeled brown adipocyte pool observed in this study. Dual-labeling lineage tracing employing dual recombinases (e.g., Cre-loxp and Dre-rox) to irreversibly label distinct cell populations at specific timepoints would eliminate such ambiguity by providing spatiotemporal resolution, high specificity, and compatibility with multi-color reporters. Therefore, such a dual-labeling strategy could be used in future investigations to provide definitive evidence to resolve whether labeled brown adipocytes originate from c-kit+ progenitors or pre-existing adipocytes or both.

The present data showed that c-kit depletion led to obesity due to whole fat accumulation, decreased thermogenic fat, and reduced thermogenesis of adipose tissue. The correlation of c-kit with obesity has been previously reported. A retrospective study of 50 newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia patients has reported that more than 75% of patients significantly gain weight after receiving imatinib, which suppresses c-kit function as a kinase inhibitor12, suggesting that c-kit is associated with human obesity; however, the mechanism remains unknown. Gao et al. demonstrated that stem cell factor (SCF)/c-kit signaling promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and energy expenditure24. In addition, activation of the SCF/c-kit systemically or specifically in brown fat augments thermogenesis and reduces body weight24. In addition to SCF/c-kit signaling, the present findings suggested that impaired c-kit+ APC-derived brown adipogenesis may account for obesity both in animals and humans with c-kit inhibition. These clinical findings suggested that c-kit+ APCs are a promising candidate with translational significance to combat obesity.

In summary, our studies revealed that adipose-resident c-kit+ cells are previously unidentified adipose progenitors. And c-kit+ APCs can differentiate into preadipocytes, early-phase brown adipocytes with enhanced capacity of thermogenic substrate metabolism, and eventually specialized thermogenic brown adipocytes. C-kit+ APC conversion to brown adipocytes is involved in pathophysiological adipose tissue homeostasis and remodeling. C-kit inhibition reduces brown adipogenesis and thermogenesis, which eventually results in obesity. Our findings provide evidence for c-kit+ progenitors as an innovative and crucial target for obesity and metabolic diseases.

The intriguing role of BAT in dissipating energy and regulating metabolic health makes them a viable therapeutic target for obesity and related metabolic diseases. The present study demonstrated that adipose-resident c-kit+ progenitors are newly identified APCs and are responsible for brown adipogenesis during adulthood, providing a promising approach to increase thermogenic fat tissue and manipulate metabolic status. Moreover, our data strongly support c-kit+ progenitor differentiation as the primary mechanism underlying brown adipogenesis, although we acknowledge that the possible contribution of pre-existing brown adipocyte proliferation to brown adipogenesis cannot be conclusively excluded without double-labeling lineage tracing experiments. Furthermore, the intrinsic characteristics of endogenous c-kit+ APCs are unclear. The precise mechanisms of adult c-kit+ APC differentiation into brown adipocytes, as well as how they are regulated under complicated pathophysiological conditions, warrant further exploration.

Methods

Animals

Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice were obtained by crossing Kit-CreER mice with Rosa26-RFP mice as previously described13. The mouse genotype was screened by PCR of genomic DNA prepared from the tail. Tam (Sigma, T5648) was dissolved in corn oil and administered by gavage (0.1–0.15 mg/g × 4 times) to induce Cre recombinase activity. Unless otherwise stated, both male and female mice were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle within a temperature-controlled room (21–22 °C) and allowed free access to food and water. The body weight of the mice was evaluated every 5 weeks. For experiments involving cold exposure, mice were housed at 4 °C (cold) or 22 °C (RT) in a controlled environmental diurnal chamber with free access to food and water for 4 weeks after Tam administration. For the HFD experiments, mice had free access to water and food (either a standard chow diet or 60% HFD; Research Diets, D12492) for 16 weeks after Tam administration. For the ACK2 experiments, mice performed localized inhibition of c-kit by intra-iBAT injection of ACK2 (Biolegend, 135131) and were housed at 4 °C (cold) for 2 weeks after Tam administration. Each mouse received an injection of 100 μL ACK2 solution (1 mg/ml) into the iBAT region every 72 h, and the control group received an equivalent volume/amount of IgG. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Mouse husbandry and all experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the School of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Cell isolation and culture

BAT was cut into small pieces and then digested with 0.2% collagenase (Sigma, C6885) at 37 °C for 45 min. The cell suspension was filtered through the 40-μm nylon cell strainer to remove tissue debris. Stromal cells were maintained in culture media (DMEM/F12, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin). SVF cells at 80% confluences were incubated in differentiation media (culture media supplemented with 10 μg/ml insulin (Beyotime, P3376), 0.5 mM IBMX (Sigma, I7018), 1 μM dexamethasone (Sigma, D4902), 10 nM T3 (Sigma, T2877) and 1 mM rosiglitazone (Sigma, R2408))for 48 h, then were incubated in induction media (culture media supplemented with 10 μg/ml insulin, 10 nM T3, and 1 mM rosiglitazone)and harvested at day 6–8 post-differentiation. For the ACK2 experiments, ACK2 or IgG control (1 mg/ml) was added to culture and differentiation media.

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraffin-embedded tissue: Sections (5-μm thick) were blocked for 1 h at RT in blocking buffer (PBS with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% Triton X-100), incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-RFP (Rockland, 600-401-379, 1:1000), anti-perilipin-1 (Abcam, ab61682, 1:500), anti-UCP1 (Novus Biologicals, NB100-2828, 1:200), and anti-c-kit (R&D Systems, AF1356, 1:100). Alexa Fluor 488- or 555-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:1000) were used to detect primary antibodies. All slides were mounted with anti-fade mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Lab, H1200).

Cells: Remove the coverslip from the medium and aspirate the excess medium from the SVF cells. Add 100 μL of BODIPY 500/510 C1, C12 (MCE, HY-D1617), gently shake it to cover the cells completely, and then incubate at RT for 5–30 min. Wash twice with medium, 5 min each time. Remove the coverslip from the medium and aspirate the excess medium from mature adipocytes. Fix it with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min and blocked for 1 h at RT in blocking buffer (PBS with 1% BSA, and 0.1% Triton X-100), incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at RT. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-SMA-FITC (Sigma, F3777,1:500), anti-CD31 (R&D, AF3628,1:50), anti-perilipin-1 (1:500), anti-CD45 (R&D, AF114), anti-PDGFRα (R&D, AF1062,1:200), anti-PDGFRβ (eBioscience, 14-1402-82, 1:200). Alexa Fluor 488- or 555-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:1000) were used to detect primary antibodies.

Histopathological analysis

The mice were subjected to perfusion fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, and iBAT, ingWAT, and pgWAT were collected at the indicated time points. For the preparation of paraffin sections, adipose tissues were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Adipose sections (5-μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and the histological features were observed and captured under a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Features in the images were measured and quantified using Image-Pro Plus 6.0.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from cells or tissues was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum RNA was extracted using a miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara), 50 ng of cDNA, and 500 nmol/L primers as well as an ABI 7500-fast detector. The primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Micro-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) study

An intravenous injection of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG; 200–300 μCi per mouse) was then given to each mouse, and the mice were maintained at 4 °C for an additional hour. Mice were anesthetized in a chamber with 3% isoflurane. Whole-body PET scans were performed using a micro-PET/CT system (SuperArgus, Sedecal, Spain) at RT with a scanning time of 10 min. Acquired PET images were co-registered with the CT images, and 18F-FDG uptake in the interscapular BAT area was analyzed using PMOD software to evaluate BAT activity. 18F-FDG uptake in BAT was quantified as the percentage of injected dose per gram tissue (%ID/g) with decay correction.

Isolation of nuclei from brown adipose tissue for snRNA-seq

The iBAT was collected from Kit-CreER; Rosa26-RFP mice housed at 4 °C. To prepare single-nucleus suspensions from iBAT, tissue was frozen using liquid nitrogen and then lysed to obtain a single-nucleus suspension by adding 2 mL of chilled lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% Nonidet™ P40 Substitute in Nuclease-Free Water) to the tissue. The tissue was homogenized 5–15 times using a tissue grinder, and the tissue was lysed on ice for 30 min with gentle swirling 3–5 times during the incubation. The reserved chilled Hibernate A®/B27®/GlutaMAX™ (HEB) media was then returned to the lysed tissue solution, and the tissue was further triturated with 5–7 passes through a 1-mL pipette. A 30-µm cell strainer (MACS Smart Strainer; Miltenyi Biotech 130-110-915) was washed with 1 mL of PBS, and the lysed tissue solution was filtered through the strainer to remove debris and clumps. Filtered nuclei were centrifuged at 500 RCF for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed, and nuclei were washed in 1 mL of Nuclei Wash and Resuspension Buffer [1X PBS with 1.0% BSA and 0.2 U/µl RNase inhibitor]. Nuclei were manually counted by Trypan blue and acridine orange/propidium iodide after each centrifugation and resuspended.

Single-nucleus RNA library preparation and sequencing

The single-nucleus suspensions were processed using the 10x Genomics platform. Nuclei were loaded onto 3’ library chips from the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3′ Library Kit according to the 10x Genomics protocol. In brief, Next GEM technology was utilized to partition the single-nucleus suspension into gel bead-in-emulsion in the 10x Chromium controller instrument. Cell lysis, barcoded reverse transcription of RNA, amplification, shearing, 5′ adapter addition, and sample index PCR were then performed. The loaded nuclei comprised 16,000 nuclei, and the libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000.

Processing of single-nucleus RNA-seq data and quality control

Cell Ranger (version 5.0) was applied to filter low-quality reads, align reads to the human reference genome (GRCh38), assign cell barcodes, and generate the unique molecular identifier (UMI) matrices. To eliminate sample-to-sample variability caused by ambient RNA present in all droplets from a given single-cell suspension, we utilized the R package SoupX v1.2.2 (SoupX removes ambient RNA contamination from droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data)25 for ambient RNA decontamination. This process involved calculating the contamination rate for each cell based on the ambient RNA expression profile derived from low RNA content droplets in the unfiltered gene-barcode matrix provided by the Cell Ranger pipeline. The count data were then normalized (RNA expression by a factor of 10,000 with log-transformed). To remove the background noise, the expression of each cell was then corrected using the estimated contamination fractions (with set Contamination Fraction (dataset, 0.88, forceAccept = TRUE)) and the ambient RNA profile. The output gene expression matrices were analyzed by R software (version 3.6.1) with the Seurat package (version 3.2.0) for further QC. All samples were merged into one Seurat object using the merge function in Seurat. Then, cells with fewer than 300 genes detected, or fewer than 500 UMI counts detected, or >30% mitochondrial UMI counts were filtered out.

Dimension reduction, unsupervised clustering, and cell-type annotation

First, we identified highly variable genes (HVGs) that were used for subsequent analysis using the Find Variable Features function with selection.method = “mvp.” Dimension reduction and unsupervised clustering were performed according to the standard workflow in Seurat. Mitochondrial genes, dissociation-induced genes, and human leukocyte antigen genes were removed from the HVGs for downstream analyses. The effect of the percentage of mitochondrial gene count was regressed out using the Scale Data function with the following parameter: “vars.to.regress = c(“nCount_RNA,” “percent.mt”).” A principal component analysis (PCA) matrix was calculated to reduce noise by using RunPCA with default parameters, and the top 18 components were used based on the knee point at the cumulative curve of standard deviations of each principal component. The PCA-reduced data were then used to compute a shared nearest neighbor graph, and they were further subjected to graph-based clustering with the Louvain Method. The clustered cells were then projected into a two-dimensional space for visualization using the nonlinear dimensional reduction method, RunUMAP, in the Seurat package.

DotPlot visualization and differential expression analysis

DotPlot is a classical plot to show the expression of marker genes in each cell cluster. Usually, the dot size represents the percentage of cells that expressed the gene, and the color represents the scaled value of the average expression level of gene X in cluster Y. In single-cell/nucleus analysis, the average expression levels of genes are calculated by normalization of the transcriptome data (gene sequence reads by a factor of 10,000 with log-transformed). To identify differentially expressed genes between two groups of clusters, we used the FindMarkers function to perform differential gene expression analysis. Genes with adjusted P value less than 0.05 were considered as differentially expressed genes.

Trajectory inference

To map differentiation of the APCs, Pre-BAs, and BAs subpopulations, trajectory analysis was performed with Monocle2 (version 2.14.0), which determined the significant transitional relationships among cell types and clusters. Raw count data from the Seurat object was converted to a Cell Data Set object using the import CDS function in Monocle. The top 100 HVGs of each subpopulation were set as the ordering genes. The minimum spanning tree was constructed using the ReduceDimensions function (reduction_method = “DDRTree”).

Statistics analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). GraphPad Prism 10 was used to perform all statistical analyses. Two group comparisons were conducted by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Source data are provided with this paper. All data supporting the findings described in this manuscript are also available from the corresponding author upon request. Single-nucleus RNA-seq dataset has been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2021) in National Genomics Data Center (Nucleic Acids Res 2022), China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA: CRA011067) that are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA011067. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Oikonomou, E. K. & Antoniades, C. The role of adipose tissue in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 83–99 (2019).

Ghaben, A. L. & Scherer, P. E. Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 242–258 (2019).

Cypess, A. M. et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1509–1517 (2009).

Saito, M. et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes 58, 1526–1531 (2009).

Claussnitzer, M. et al. FTO obesity variant circuitry and adipocyte browning in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 895–907 (2015).

Min, S. Y. et al. Human ‘brite/beige’ adipocytes develop from capillary networks, and their implantation improves metabolic homeostasis in mice. Nat. Med. 22, 312–318 (2016).

Wang, W. & Seale, P. Control of brown and beige fat development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 691–702 (2016).

Spalding, K. L. et al. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature 453, 783–787 (2008).

Wang, Q. A. et al. Distinct regulatory mechanisms governing embryonic versus adult adipocyte maturation. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 1099–1111 (2015).

Jiang, Y., Berry, D. C., Tang, W. & Graff, J. M. Independent stem cell lineages regulate adipose organogenesis and adipose homeostasis. Cell Rep. 9, 1007–1022 (2014).

Sanchez-Gurmaches, J., Hung, C. M. & Guertin, D. A. Emerging complexities in adipocyte origins and identity. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 313–326 (2016).

Aduwa, E. et al. Significant weight gain in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia after imatinib therapy. Blood 120, 5087–5088 (2012).

Chen, Q. et al. Genetic lineage tracing analysis of c-kit(+) stem/progenitor cells revealed a contribution to vascular injury-induced neointimal lesions. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 121, 277–286 (2018).

Shamsi, F. et al. Vascular smooth muscle-derived Trpv1(+) progenitors are a source of cold-induced thermogenic adipocytes. Nat. Metab. 3, 485–495 (2021).

Lee, Y. H., Petkova, A. P., Konkar, A. A. & Granneman, J. G. Cellular origins of cold-induced brown adipocytes in adult mice. FASEB J. 29, 286–299 (2015).

Shao, M. et al. Cellular origins of beige fat cells revisited. Diabetes 68, 1874–1885 (2019).

Oguri, Y. et al. CD81 controls beige fat progenitor cell growth and energy balance via FAK signaling. Cell 182, 563–577.e20 (2020).

Lee, Y. H., Petkova, A. P., Mottillo, E. P. & Granneman, J. G. In vivo identification of bipotential adipocyte progenitors recruited by beta3-adrenoceptor activation and high-fat feeding. Cell Metab. 15, 480–491 (2012).

Graja, A. & Schulz, T. J. Mechanisms of aging-related impairment of brown adipocyte development and function. Gerontology 61, 211–217 (2015).

Tajima, K. et al. Mitochondrial lipoylation integrates age-associated decline in brown fat thermogenesis. Nat. Metab. 1, 886–898 (2019).

Berry, D. C. et al. Cellular aging contributes to failure of cold-induced beige adipocyte formation in old mice and humans. Cell Metab. 25, 166–181 (2017).

Lee, H. J. et al. Endothelial cell-derived stem cell factor promotes lipid accumulation through c-Kit-mediated increase of lipogenic enzymes in brown adipocytes. Nat. Commun. 14, 2754 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Obesity and hyperinsulinemia drive adipocytes to activate a cell cycle program and senesce. Nat. Med. 27, 1941–1953 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. The stem cell factor/Kit signalling pathway regulates mitochondrial function and energy expenditure. Nat. Commun. 5, 4282 (2014).

Young, M. D. & Behjati, S. SoupX removes ambient RNA contamination from droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data. GigaScience 9, giaa151 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82125005, 82270430, 82470349, and 81971350), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (22ZR1480000), National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1104200), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LZ24H040001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Q.C., Y.Y., Z.R., L.Z., and M.J. Methodology: Q.C., Y.Y., Z.R., and M.J. Investigation: Q.C., Y.Y., Z.R., Q.Z., D.Y., C.F., J.Z., M.L., M.Y., S. S., L.Z., and M.J. Visualization: Q.C., Y.Y., and Z.R. Supervision: Q.C., L.Z., and M.J. Writing—original draft: Q.C., Y.Y., and Z.R. Writing—review and editing: Q.C., Y.Y., Z.R., and M.J.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Yu, Y., Zhang, R. et al. Commitment of adipose-resident c-kit+ progenitors to brown adipocytes contributes to adipose tissue homeostasis and remodeling. Nat Commun 16, 5883 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60754-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60754-w