Abstract

Effective clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) requires targeting drug-tolerant populations within host macrophages. Here, we show that macrophage metabolic states govern redox heterogeneity and drug response in intracellular Mtb. Using a redox-sensitive fluorescent reporter (Mrx1-roGFP2), flow cytometry, and transcriptomics, we found that macrophages with high oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and low glycolysis harbor reductive, drug-tolerant Mtb, whereas glycolytically active macrophages generate mitochondrial ROS via reverse electron transport, imposing oxidative stress on Mtb and enhancing drug efficacy. Computational and genetic analyses identified NRF2 as a key regulator linking host metabolism to bacterial redox state and drug tolerance. Pharmacological reprogramming of macrophages with the FDA-approved drug meclizine (MEC) shifted metabolism towards glycolysis, suppressed redox heterogeneity, and reduced Mtb drug tolerance in macrophages and mice. MEC exhibited no adverse interactions with frontline anti-TB drugs. These findings demonstrate the therapeutic potential of host metabolic reprogramming to overcome Mtb drug tolerance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection represents one of the most intricate inter-organismic interactions, with both the bacterium and macrophages exhibiting remarkable phenotypic diversity1. Infected macrophages vary in polarization (M1/M2), metabolism (glycolysis/fatty acid oxidation), and lineage (alveolar macrophages [AMs]/interstitial macrophages [IMs]), all of which influence treatment outcome. This heterogeneity contributes to prolonged treatment of tuberculosis (TB), fostering noncompliance and drug resistance2,3. However, the mechanistic links between host-pathogen diversity and drug response remain poorly understood and addressing this gap is critical for developing shorter, more effective TB treatments and guiding future drug discovery.

In vivo studies reveal that macrophage functional diversity creates distinct intracellular niches that shape Mtb physiology and drug susceptibility4,5,6,7. IFNγ-activated macrophages drive Mtb into a non-proliferating but metabolically active drug-tolerant state4. A genome-wide screen identified host regulators (magnesium transporter and lipid droplets) in mediating this shift to persistence8. Nitric oxide (NO), a key macrophage effector, inhibits bacterial respiration, Fe-S cluster homeostasis, and carbon metabolism, promoting quiescence and phenotypic drug tolerance4,9,10. Mtb growth rate varies between macrophages and correlates with pre-existing cell-cell variation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity11. A highly drug-tolerant, non-replicating Mtb population is also found in necrotic caseum in rabbit lung cavities12. Furthermore, clinically prevalent mutations in metabolic genes (glpK, icl1 and prpR) and toxin-antitoxin modules reduce Mtb fitness and contribute to multidrug tolerance in macrophages and animal models, potentially limiting treatment efficacy in human TB13,14,15,16,17,18.

While stress-induced metabolic quiescence is a well-established driver of drug tolerance in Mtb4,19, actively replicating Mtb within macrophages can also exhibit tolerance20,21. Animal studies show that both replicating and non-replicating subpopulations can resume growth after drug withdrawal, suggesting that growth arrest alone does not account for tolerance19,20. Consistent with this, AMs from TB patient lung lesions harbor both metabolically active and quiescent subpopulations showing multi-drug tolerance22. These findings highlight the need to mechanistically dissect host and bacterial factors contributing to drug tolerance in metabolically active Mtb to better understand why protracted TB therapy is required.

We previously established a link between redox heterogeneity and drug tolerance in replicating Mtb using a ratiometric biosensor (Mrx1-roGFP2) to monitor mycothiol redox potential (EMSH), which was traced to heterogeneity in the invaded macrophage population21,23. Replicating Mtb within macrophages displayed redox diversity21,23. Infected macrophages were classified into three groups predominantly harboring Mtb in EMSH-reduced (−300 mV), EMSH-basal (−275 mV), or EMSH-oxidized (>−240 mV) states. This redox variation correlated with drug response, with EMSH-reduced bacteria exhibiting drug tolerance. EMSH-basal bacteria showed intermediate sensitivity, and EMSH-oxidized bacteria were highly drug susceptible23. However, the host physiological factors driving this macrophage heterogeneity, and how they influence redox and drug tolerance in replicating Mtb, remain unclear. It also remains unresolved whether macrophage heterogeneity causes or results from redox diversification in intracellular Mtb.

In this study, we dissected how macrophage phenotypic heterogeneity drives redox diversity and drug tolerance in Mtb. Using Mrx1-roGFP2, flow sorting, and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), we uncovered transcriptional differences among infected macrophages that create metabolically distinct niches, shaping Mtb subpopulations with varied redox potential and drug responses. Integrative computational analysis revealed that the antioxidant regulator nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) effectuates bioenergetic changes in infected macrophages, promoting a reductive, drug-tolerant state in Mtb. Genetic and pharmacological reprogramming of mitochondrial metabolism collapsed redox heterogeneity and diminished drug tolerance in Mtb in both macrophages and mouse models.

Results

Transcriptional profiling of macrophage sub-populations identifies factors that promote redox diversity and drug tolerance in Mtb

We infected primary mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) with an Mtb strain carrying an established redox biosensor (Mtb-roGFP2) plasmid that reports EMSH of Mtb23. Biosensor expression leads to ratiometric changes in the fluorescence excitation at 405 and 488 nm with a uniform emission at 510 nm in response to redox changes in Mtb. Under oxidative and reductive conditions, the fluorescence ratio of 405/488 increases and decreases, respectively23. We used our previously established flow sorting pipeline that averages the median fluorescence ratio (405/488) of the biosensor expressed by intraphagosomal Mtb-roGFP2 to gate and sort BMDMs into subsets enriched with either EMSH-reduced, EMSH-basal, or EMSH-oxidized bacteria (Suppl. Fig. 1). We previously showed that EMSH-reduced bacteria inside THP-1 macrophages are replicative and tolerant to isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (RIF), whereas EMSH-basal and -oxidized Mtb showed drug sensitivity21,23. We first determined whether the observations made with the THP-1 cell line and first-line anti-TB drugs are recapitulated in the present experimental setup of primary cells (BMDMs) exposed to multiple antibiotics clinically used to treat drug-sensitive and -resistant TB. Using the biosensor-based gating strategy, we sorted BMDMs infected with Mtb-roGFP2 at 24 h post-infection (p.i.), treated them with anti-TB drugs (INH, RIF, moxifloxacin (MOXI), and bedaquiline (BDQ) at 3X the in vitro minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC]) for 48 h, and confirmed that the EMSH-reduced fraction is uniformly more tolerant to multiple anti-TB drugs than the EMSH-oxidized fraction (Suppl. Fig. 2). In subsequent experiments, we focussed on BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced or EMSH-oxidized bacteria, as these fractions represent drug-tolerant or drug-sensitive phenotypes of Mtb, respectively21,23.

To acquire a mechanistic understanding of why macrophage subsets harbor redox diverse Mtb populations, we sorted Mtb-roGFP2-infected BMDMs 24 h p.i. and subjected them to RNA-seq (Fig. 1A). Four macrophage fractions were sorted for analysis by RNA-seq: BMDMs-predominantly harboring (i) EMSH-reduced bacilli, (ii) EMSH-oxidized bacilli, (iii) bystander BMDMs, and (iv) uninfected BMDMs (Fig. 1A). We identified differentially expressed genes (DEG) [base mean > 10, fold change > 1.5, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.1] between Mtb-infected BMDM subsets (BMDMs directly infected with Mtb), bystanders (uninfected BMDMs in the same environment as infected BMDMs), and uninfected BMDMs (BMDMs not exposed to Mtb- baseline control) (Suppl. Data 1). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that samples clustered with their biological replicates with clear segregation between uninfected and Mtb-infected BMDMs (Fig. 1B). An additional PCA on all infected BMDMs consistently revealed clear segregation of two populations of cells containing drug-tolerant (EMSH-reduced) or -sensitive (EMSH-oxidized) Mtb, indicating differences in the transcriptome signatures (Fig. 1C). Compared to the uninfected control, the expression of 6460 and 6225 genes was affected in the BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced and EMSH-oxidized populations, respectively (Fig. 1D, Suppl. Data 1). Data indicate that BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced and EMSH-oxidized cells represent functionally distinct macrophage subpopulations. Consistent with this, a direct comparison of transcriptomes revealed that 825 genes were differentially regulated between EMSH-oxidized and EMSH-reduced harboring fractions (374 and 367 genes were upregulated in EMSH-oxidized and EMSH-reduced fractions, respectively) (Suppl. Data 2). Expression of 6005 genes was deregulated between bystanders and uninfected BMDMs (Suppl. data 1). The bystander transcriptome showed overlap with both the infected subpopulations (fold change > 2.0, false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.1). However, among the DEGs between EMSH-oxidized and -reduced, there was ~2-fold more overlap between the genes upregulated in the EMSH-oxidized fraction and bystanders (212 genes) compared to those upregulated in the EMSH-reduced fraction and bystanders (99 genes) (Suppl. Fig. 3A, Suppl. Data 3). Consistent with this result, flow sorting of bystander BMDMs and subsequent infection with Mtb-roGFP2 uniformly shifted the EMSH of Mtb towards the oxidative state (Suppl. Fig. 6).

A Schematic showing flow sorting–coupled RNA seq of macrophage subpopulations: uninfected (green), bystanders (gray), macrophages harboring EMSH-oxidized (yellow, here on labeled as ‘oxidized’) or EMSH-reduced (blue, here on labeled as ‘reduced’) Mtb; B Principal component analysis (PCA) plot comparing infected and uninfected macrophages; C PCA plot showing the subpopulations within the infected macrophages: ‘bystanders’, ‘oxidized’, ‘reduced’; D Heat map of genes differentially expressed between the subpopulations; genes clustered according to their involvement in pathways: E Oxidative phosphorylation; F NRF2 regulon; G Hippo signaling. Heatmaps are generated from three independent experiments with base mean >10, FDR < 0.1, and log2FC > 0.6. Figure 1A: Created in BioRender. Yadav, V. (2025) https://BioRender.com/6x5yph4. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The transcriptome of EMSH-oxidized and EMSH-reduced BMDMs overlapped considerably with that of previously reported transcriptional data of diverse macrophage populations infected with Mtb ex vivo and in vivo (BMDMs, AMs, and IMs) (Suppl. Fig. 3B–D)5,24. Overlap analysis between 825 DEGs of oxidized vs reduced fractions with the DEGs between Mtb-infected AMs or IMs showed a marginally higher overlap of EMSH-oxidized BMDMs with IM (17%, Fisher exact test: p < 0.0001) compared to the EMSH-reduced BMDMs (11%, Fisher exact test: p < 0.0001) (Suppl. Fig. 3B, Suppl. Data 4). DEGs between oxidized and reduced fractions showed overlap (Fisher exact test: p < 0.001) with Mtb-infected AMs isolated from the mouse bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid at day 10 p.i. (Suppl. Fig. 3C, Suppl. Data 5)25, indicating similarities in macrophage response to infection ex vivo and in vivo. Among shared genes, BAL fluid AMs were more similar to BMDMs with EMSH-reduced Mtb than EMSH-oxidized Mtb (47 vs 15 genes; Suppl. Fig. 3C), showing some overlap in their transcriptomes. We did not find any significant overlap with the transcriptomes of M1 and M2 macrophages (Suppl. Fig. 3D, Suppl. Data 6), which suggests that these macrophage subpopulations do not segregate along the M1-M2 axis.

To investigate the molecular basis of drug tolerance exhibited by EMSH-reduced bacilli in BMDMs (Suppl. Fig. 2), we conducted pathway analysis using the Gene Ontology tool (ShinyGO 0.8026) and the pathway enrichment tool, Enrichr27. We found that genes associated with mitochondrial respiration (oxidative phosphorylation [OXPHOS]), central carbon metabolism (TCA cycle), Hippo signaling, and cell protective antioxidant responses (NRF2-regulon) were induced more in BMDMs containing EMSH-reduced bacilli than those containing EMSH -oxidized bacilli (Fig. 1D–G). NRF2 is a master regulator of a cell-protective antioxidant transcriptional signature, including antioxidant production (Nqo1, Cat, Txnrd1), iron metabolism (Slc7a11, Slc7a2, Clec4e, Fbxl5), and cytoplasmic thiol production (Gsta3, Gclc, Gstm1 and Gstm2). These genes were induced in macrophages with EMSH-reduced fraction versus -oxidized fraction (Fig. 1F, Suppl. Data 2). Consistent with this, using a transcription factor enrichment tool (ChEA328), we found that the genes upregulated in BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced bacteria contained an NRF2-binding motif in their promoter region (Suppl. Fig. 4A). Enrichment of NRF2-specific genes was further substantiated by a significant commonality (enrichment FDR: 1.0E-05) with the genes downregulated in the transcriptome of lung tissues of Nrf2 knock-out (Nrf2-/-) transgenic mice (Suppl. Fig. 4B). Another transcription factor, Bach2, negatively regulates the antioxidant response by suppressing NRF2 transcriptional activity29,30. As expected, genes upregulated in lung macrophages of Bach2 knock-out (Bach2-/-) mice overlapped significantly with genes induced in BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced bacteria (enrichment FDR: 3.0E-24, Suppl. Fig. 4B). Ontology-based pathway enrichment further established the upregulation of antioxidant pathways in the macrophages harboring EMSH-reduced Mtb (Suppl. Fig. 4C). The oxidized fraction of infected BMDMs showed enrichment of genes involved in the cell cycle, DNA damage response (base-excision, DNA mismatch repair), and complement activation pathways (Suppl. Fig. 5).

Activation of the NRF2 regulon and Hippo pathway, which respond to redox and energetic changes31,32,33,34,35,36, along with upregulation of the TCA cycle and OXPHOS genes in BMDMs containing EMSH-reduced bacteria, suggests that host energy homeostasis could be an important physiological parameter required for mediating redox-dependent drug tolerance in Mtb populations.

NRF2-dependent changes in mitochondrial bioenergetics induce redox-linked drug tolerance in Mtb

Our transcriptomic data suggest a role for mechanisms controlling host redox balance and mitochondrial bioenergetics in supporting the emergence of a drug-tolerant EMSH-reduced population during infection. To clarify this link, we sorted BMDMs enriched with EMSH-reduced or EMSH-oxidized bacteria and applied an extracellular flux (XF) analyzer to measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) (Fig. 2A). Mammalian cells rely on cytosolic glycolysis and mitochondrial OXPHOS to generate energy for cellular functions. The OCR quantifies OXPHOS, whereas ECAR quantifies acidification due to lactate export during glycolytic flux37. Consistent with our RNA-seq data, BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced Mtb exhibited higher basal respiration and ATP-linked OCR than EMSH-oxidized fraction (Fig. 2B, C). Conversely, glycolytic parameters, such as glucose metabolism and glycolytic capacities, were significantly higher in EMSH-oxidized BMDMs than in the EMSH-reduced fraction (Fig. 2D, E).

A Workflow of the flow-sorting coupled Seahorse Extracellular Flux analysis; B, C A modified mitostress test was performed to calculate mitochondrial parameters. BR- basal respiration, ATP- ATP production, H + -leak- proton leak; D, E ECAR test was performed to assess the parameters associated with glycolysis in the three sorted BMDM subpopulations. Gly- glycolysis, GC- glycolytic capacity, NGA- non-glycolytic acidification; F Mitochondrial ROS in Mtb-roGFP2 infected BMDMs. Antimycin A used as the positive control; G Cellular ROS measured in Mtb-roGFP2 infected BMDMs, 100 µM menadione used as the control. MFI- median fluorescence intensity, a.u.-arbitrary units. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D., representative of three independent experiments. p-value determined using a Student’s two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction for comparison between two groups or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. Figure 2A: Created in BioRender. Yadav, V. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y42m819. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The drop in mitochondrial OXPHOS in BMDMs containing EMSH-oxidized bacilli is accompanied by higher mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mitoROS, a hallmark of mitochondrial stress) compared to BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced bacteria (Fig. 2F). MitoROS is a significant contributor to cellular ROS38. In agreement with this, the accumulation of cellular ROS was ~3-fold higher in BMDMs containing EMSH-oxidized Mtb than in the EMSH-reduced fraction (Fig. 2G). Scavenging of cellular ROS either by glutathione (GSH) or mitoTEMPO (a specific scavenger of mitoROS39) significantly increased the proportion of BMDMs containing EMSH-reduced fraction (Suppl. Fig. 7). The generation of ROS is dependent on the electron transport chain (ETC) during forward electron transport (FET), as well as when electrons flow backwards (reverse electron transport or RET) through complex I40. To establish the source of ROS (FET or RET) within the ETC of BMDMs, we measured mitoROS in BMDMs treated with rotenone. In FET, rotenone facilitates ROS generation at complex I. In contrast, rotenone reduces ROS by blocking complex I during RET40,41. The addition of rotenone uniformly reduces mitoROS in all the subsets of BMDMs infected with Mtb, consistent with earlier reports of RET as the primary contributor of mitoROS during Mtb infection41 (Suppl. Fig. 8). Consistent with the RNA-seq data, the bystander BMDMs exhibit glycolytic shift and mitochondrial stress similar to BMDMs containing EMSH-oxidized Mtb (Fig. 2B–G). These data show that BMDMs harboring drug-tolerant EMSH-reduced bacilli maintain mitochondrial function with limited glycolytic activity, while the EMSH-oxidized BMDM fraction and bystander BMDMs undergo a glycolytic shift accompanied by mitochondrial stress.

NRF2 is a prominent factor that sustains the structural and functional integrity of mitochondria (e.g., ATP synthesis, membrane potential, mitoROS, and substrate availability)42,43 and that is overexpressed in AMs during the early stages of Mtb replication in mice25. Since an NRF2-driven transcriptional response featured in our RNA-Seq analysis, we hypothesized that NRF2 could link macrophage bioenergetics to redox diversity in Mtb. Supporting this, we found that several genes upregulated in macrophages containing EMSH-reduced Mtb had an NRF2 ChIP-Seq peak (Fig. 3A)25,44. In contrast, none of the genes upregulated in the macrophages harboring EMSH-oxidized Mtb showed these peaks (Fig. 3A). On this basis, we reduced the expression of Nrf2 in BMDMs using siRNA (siNRF2-BMDMs), resulting in a significant downregulation of Nrf2 and its dependent genes without affecting cellular viability (Suppl. Fig. 9A, B). As expected, the knockdown of Nrf2 increased mitoROS more than the scrambled siRNA (siSCR-BMDMs) control upon Mtb infection (Fig. 3B). We next investigated the effect of Nrf2 knockdown on mitochondrial respiration, EMSH of Mtb, and INH tolerance. Basal OCR and ATP-linked OCR were reduced in siNRF2-BMDMs compared to siSCR-BMDMs at 24 h p.i., indicating decreased mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 3C, D). Nrf2 knockdown did not increase glycolysis to compensate for the decreased mitochondrial respiration, which could be due to partial silencing of Nrf2 (Suppl. Fig. 9C). Diminished mitochondrial respiration and enhanced mitoROS correlated with an increased fraction of siNRF2-BMDMs harboring EMSH-oxidized Mtb relative to siSCR-BMDMs at 24 h p.i.(Fig. 3E). We also determined whether the oxidative shift observed upon suppression of Nrf2 led to a reduction in drug tolerance. While the survival of Mtb was comparable in siNRF2- and siSCR-BMDMs at 72 h p.i. (Fig. 3F), Mtb growing in siNRF2 BMDMs were significantly more sensitive to INH than those in siSCR BMDMs (percentage survival in siSCR: 39% ± 3% vs siNRF2: 19% ± 1%) (Fig. 3F).

A z-normalized RNA-Seq data of uninfected, bystanders, oxidized, and reduced populations, where genes are clustered by expression levels. Only those genes are represented that satisfy two of the following criteria: belong to the Nrf2 pathway (red) and bear the NRF2 binding motif in the promoter region (green) or have an NRF2 ChIP-seq (Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing) peak detected near the promoter region (blue). Genes in black represent those that are significantly upregulated in the reduced subpopulation in comparison to the oxidized subpopulation (no gene upregulated in the oxidized subpopulation was detected amongst the above genes); B Mitochondrial ROS in BMDMs transfected either with scrambled siRNA (siSCR, yellow) or siRNA targeted against Nrf2 (siNRF2, blue) at 24 h p.i. MFI- median fluorescence intensity, a.u.-arbitrary units; C, D Modified mitostress test of siSCR- or siNRF2-BMDMs at 24 h p.i. infected with Mtb H37Rv at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 2. BR- basal respiration, ATP- ATP production, H + -leak- proton leak, nmOCR- non-mitochondrial respiration; E Redox profile of Mtb-roGFP2 infected BMDMs transfected either with scrambled siRNA (siSCR) or siRNA against Nrf2 (siNRF2) at 24 h p.i; F Bar plot showing the colony forming units (CFUs) of Mtb in siSCR and siNRF2 BMDMs, treated with 3X MIC of INH (0.375 µg/ml) for 48 h. INH treatment was initiated at 24 h p.i.; G Mitochondrial ROS assessed in infected BMDMs upon treatment with different concentrations of SFN at the indicated concentrations at 24 h p.i.; H Glycolytic function test showing the ECAR upon treatment with 0.05% DMSO (vehicle control, labeled “DMSO”) or 5 µM SFN at 24 h p.i.; I Percentage distribution of redox-diverse fractions of Mtb-roGFP2 in BMDMs treated with the indicated concentrations of SFN at 24 h p.i.; J Antibiotic tolerance of intracellular Mtb assessed by CFUs upon treatment with vehicle or 5 µM SFN and 3X MIC of INH (0.375 µg/ml) for 48 h. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. p-value determined using a Student’s two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction for comparison between two groups or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As an additional verification of a functional linkage between NRF2 and mycobacterial redox, we used sorafenib (SFN), a pharmacological inhibitor of the Nrf2-Keap1 axis45. SFN attenuates the nuclear translocation of NRF2 and suppresses the transcriptional expression of NRF2-dependent antioxidant and respiratory genes, resulting in elevated mitochondrial stress45,46. Consistent with this observation, BMDMs treated with non-toxic concentrations of SFN (2.5–5 μM) led to suppressed OCR, a compensatory increase in glycolytic rate, and enhanced mitoROS (Fig. 3G, H, Suppl. Fig. 10A, B). Importantly, SFN treatment of BMDMs diminished redox heterogeneity in intraphagosomal Mtb, with most of the BMDMs harboring bacteria in the EMSH-basal or -oxidized states (Fig. 3I). Lastly, ~40% of Mtb survived INH treatment in BMDMs, whereas survival of Mtb reduced to ~19% upon exposure to SFN (5 μM) with INH (Fig. 3J). We confirmed that 5 μM of SFN does not affect Mtb survival in the 7H9 growth medium, as the MIC of SFN against Mtb remains 20 μM (Suppl. Fig. 10C, D), suggesting that SFN lowers INH tolerance of intraphagosomal Mtb by modulating host pathways. These data indicate that the differential induction of Nrf2 is one of the mechanisms that account for the observed bioenergetic differences in macrophages, resulting in redox heterogeneity and drug tolerance of Mtb.

Metabolic state of macrophages drives redox-dependent drug tolerance in Mtb

Data indicate a preferential engagement of mitochondrial OXPHOS by BMDMs harboring drug-tolerant EMSH-reduced bacteria, whereas drug-sensitive EMSH-oxidized Mtb resides in BMDMs committed to glycolysis. These observations motivated us to determine whether shifting metabolic reliance interchangeably between mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis modulates redox heterogeneity and drug tolerance in Mtb. To do this, we first examined the energy source driving mitochondrial respiration and the emergence of drug-tolerant, EMSH-reduced Mtb in BMDMs.

Mitochondria utilize glucose, glutamine (Gln), and fatty acids to generate ATP by OXPHOS. We assessed the preference of BMDMs harboring redox-diverse Mtb to use glucose, Gln, or fatty acids as energy sources in the mitochondrial stress test. To test the oxidation of endogenous fatty acids, we flow-sorted BMDMs containing EMSH-reduced and EMSH-oxidized Mtb. We measured OCR after treatment with the fatty acid oxidation inhibitor etomoxir (Eto). Both basal OCR and ATP-linked OCR were significantly reduced upon Eto treatment of BMDMs containing EMSH-reduced bacteria (Suppl. Fig. 11A). However, Eto treatment also suppresses the OCR of BMDMs harboring EMSH-oxidized and bystander BMDMs (Suppl. Fig. 11A). Moreover, Eto treatment did not affect the redox heterogeneity displayed by intraphagosomal Mtb (Suppl. Fig. 11B). Like Eto, trimetazidine, which inhibits the 3-keto acyl CoA thiolase step in the β-oxidation of fatty acids38,47, had no influence on redox heterogeneity exhibited by intra-phagosomal Mtb (Suppl. Fig. 11C). These findings agree with fatty acids being a principal energy source for Mtb-infected macrophages48,49,50. However, the fatty acid-dependent changes in the metabolic state of infected macrophages are unlikely to cause redox variations in the Mtb population.

Inhibition of Gln oxidation by bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadia-zol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES) did not affect the OCR of bystander or BMDMs containing redox diverse Mtb (Suppl. Fig. 11D). As expected, BPTES treatment did not influence the redox heterogeneity of Mtb (Suppl. Fig. 11E). Inspection of RNA-seq data revealed enhanced expression of mitochondrially located pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) in BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced compared to EMSH-oxidized fraction (Fig. 4A). We hypothesized that the EMSH-reduced fraction utilizes pyruvate for mitochondrial OXPHOS rather than lactic acid production. Inhibition of mitochondrial oxidation of glucose upon treatment with UK5099, which blocks pyruvate transport from the cytoplasm into mitochondria, resulted in a significant reduction in basal and ATP-linked OCR of BMDMs (Fig. 4B–D). As expected, UK5099 stimulates ECAR of Mtb-infected BMDMs (Suppl. Fig. 12A). UK5099 treatment of Mtb-infected BMDMs leads to pyruvate accumulation and a significant drop in early TCA cycle intermediates like α-ketoglutarate (2-KG) and citrate/isocitrate, confirming impaired pyruvate transport and OXPHOS without affecting macrophages’ viability (Suppl. Figs. 12B, C, 13A, Suppl. Data 8, 9). Other TCA metabolites showed slight, non-significant reductions, while glycolytic intermediates remained largely unchanged (Suppl. Fig. 12C).

A Heat map showing expression of different subunits of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in the macrophage subpopulations: uninfected (green), bystanders (gray), macrophages harboring EMSH-oxidized (yellow) or EMSH-reduced (blue) Mtb; B Mechanism of action of UK5099, a mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) inhibitor; C, D. Modified mitostress test of Mtb-infected BMDMs upon treatment with 0.05% DMSO (vehicle control, labeled “DMSO”) or 10 µM UK5099 at 24 h p.i. BR- basal respiration, ATP- ATP production, H + -leak- proton leak, nmOCR- non-mitochondrial respiration; E Redox profile of intracellular Mtb in BMDMs 24 h p.i. treated with indicated concentrations of UK5099; F Antibiotic tolerance to 3X MIC of INH (MIC: 0.125 µg/ml) or MOXI(MIC: 0.25 µg/ml) with or without 10 µM UK5099; G Schematic representation of cellular metabolic pathways in the presence of 10 mM glucose or 10 mM galactose as sole sugar sources; H Experimental design to determine the effect of glucose (Glu) and galactose (Gal) on the redox profile and antibiotic tolerance of intracellular Mtb; I–K Extracellular flux analysis of Mtb-infected BMDMs at 24 h p.i. to measure basal respiration (BR) (I), glycolysis (J), and a ratio of OCR (BR) to ECAR (glycolysis) (K); L Redox profile of the intracellular Mtb in the presence of 10 mM Glu or 10 mM Gal as sole sugars at 24 h p.i.; M Antibiotic tolerance to 3X MIC of INH in Glu- or Gal-containing medium; N Intracellular abundance of glycolytic intermediates in Mtb-infected BMDMs growing in medium containing either 10 mM Glu or Gal at 24 h p.i. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. p-value determined using a Student’s two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction for comparison between two groups or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. Figure 4B, G, H: Created in BioRender. Yadav, V. (2025) https://BioRender.com/gi9w8lj; https://BioRender.com/n53i529; https://BioRender.com/f70x563. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Importantly, and in contrast to Eto and BPTES, UK5099-mediated inhibition of OCR correlated with a decrease in EMSH-reduced bacteria with a concomitant increase in EMSH-oxidized and -basal fractions in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4E). Consistent with this, drug tolerance assays suggest that UK5099 uniformly weakens the ability of Mtb to tolerate INH and MOXI (Fig. 4F; survival in INH: 32% ± 3%, INH + UK5099: 18% ± 1%; MOXI: 52% ± 3%, MOXI + UK5099: 34% ± 4%). UK5099 influences EMSH and drug tolerance of Mtb through the host, as it does not impact bacterial growth in 7H9 culture medium (Suppl. Fig. 13B).

Our efforts to confirm the contribution of pyruvate to redox-dependent drug tolerance of Mtb is complicated by the fact that multiple mitochondrial enzymes (e.g., glutamate-pyruvate transaminase 2 or alanine aminotransferase 2, serine: pyruvate aminotransferase, L-cysteine to pyruvate conversion pathway) directly contribute to pyruvate flux for OXPHOS without the need for transporting cytosolic pyruvate51,52,53,54. To circumvent this issue, we shifted cellular energy metabolism by selectively culturing BMDMs on glucose or galactose as the sole sugar source. Production of pyruvate due to glycolysis yields two net ATP, while pyruvate yield, via galactose metabolism, generates no net ATP55. Therefore, using galactose as the sole sugar source coerces mammalian cells to generate ATP by utilizing pyruvate to fuel mitochondrial OXPHOS (Fig. 4G, H). In agreement with this idea, when Mtb-infected BMDMs were grown in galactose, they exhibited a reduction in ECAR, reflecting decreased glycolysis and increased OCR, resulting in a ~ 5-fold increase in the OCR/ECAR ratio compared to glucose as the carbon source (Fig. 4I–K). Carbon source–dependent changes in OCR and ECAR did not alter the cytosolic pH of Mtb-infected BMDMs (Suppl. Fig. 14). Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)–based steady-state metabolomics revealed that BMDMs cultured in galactose had markedly reduced glycolytic intermediates but maintained TCA cycle metabolites compared to glucose-fed cells (Fig. 4N, Suppl. Fig. 15 and Suppl. Data 8, 9). Notably, galactose exposure led to glucose-6-phosphate accumulation, likely due to inhibition of glucose-6-phosphatase by galactose-1-phosphate, a product of galactose metabolism catalyzed by galactokinase56. These data are consistent with a switch to pyruvate oxidation by mitochondria when BMDMs use galactose as an energy source.

We next asked whether a shift in metabolic reliance to galactose-linked mitochondrial OXPHOS induces a reductive shift in the EMSH of Mtb, leading to increased drug tolerance. Compared to glucose, culturing in galactose resulted in a higher fraction of BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced Mtb (Fig. 4L). The increased fraction of EMSH-reduced Mtb resulted in ~63% of bacteria surviving INH in galactose-grown conditions compared to ~30% in glucose-grown conditions (Fig. 4M). Taken together, the data show that inherent metabolic plasticity displayed by macrophages in sugar utilization promotes redox diversity in Mtb to tolerate antibiotic pressure. Overall, these results indicate that while both fatty acids and glucose support bioenergetics in infected BMDMs, the flux of glucose via pyruvate for OXPHOS is necessary to induce a reductive shift in the EMSH of Mtb. In contrast, glycolysis likely plays a prominent role in maintaining bioenergetics in BMDMs containing EMSH-oxidized Mtb.

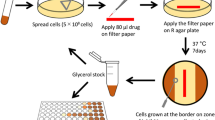

Anti-emetic drug meclizine reprograms macrophage bioenergetics during infection

Given that a metabolic shift from glycolysis to mitochondrial OXPHOS promotes redox-dependent drug tolerance, we hypothesized that targeting such a shift could potentiate TB treatment. However, pharmacological agents that can safely redirect energy metabolism from OXPHOS to glycolysis without compromising therapeutic value are generally limited and completely absent from the TB field. The deployment of a nutrient-sensitized screening strategy has identified an FDA-approved drug, meclizine (MEC), that shifts cellular energy metabolism from mitochondrial respiration to glycolysis in a variety of mammalian cells55,57. MEC is available without prescription for the treatment of nausea and vomiting, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and, to our knowledge, has not been explored as a treatment for TB55. Based on these findings, we investigated the mechanism and potential therapeutic utility of MEC in targeting redox-driven drug tolerance in Mtb.

We first determined whether MEC induces a reduction in OCR concomitant with an increase in ECAR in Mtb-infected BMDMs. Treatment with 20 μM of MEC reduced mitochondrial OCR and increased ECAR in Mtb-infected BMDMs without affecting the cytosolic pH of macrophages (Fig. 5A, B, Suppl. Fig. 16A). Upon MEC treatment, we also observed increased mitoROS and mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 5C, D). A change in cellular metabolism is often associated with mitochondrial remodeling58,59. We assessed whether MEC treatment affects the mitochondrial architecture by imaging mitochondria in Mtb-infected macrophages treated with MEC and observed that the surface area and the volume of mitochondria reduce significantly upon treatment (Fig. 5E). These findings suggest increased mitochondrial fragmentation upon MEC treatment, which could lead to a metabolic shift from OXPHOS towards glycolysis60,61.

A Bar plot showing the mitochondrial respiratory parameters determined by the modified mitostress test at 24 h p.i. upon treatment with 20 µM MEC or 0.2% DMSO (vehicle control, labeled “DMSO”). BR- basal respiration, ATP- ATP production, H + -leak- proton leak; B Glycolytic stress test to assess the glycolytic levels in infected macrophages 24 h p.i. upon treatment with 20 µM MEC or vehicle. Gly- glycolysis, GC- glycolytic capacity, NGA- non-glycolytic acidification; C Mitochondrial ROS measured upon treatment with 20 µM MEC at 24 h p.i.; D Mitochondrial membrane polarization measured by JC-1 dye at 24 h p.i., 50 µM carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) treatment used as positive control; UI: uninfected macrophages; E Representative pseudocoloured 3D views of uninfected and mCherry expressing Mtb-infected BMDMs at 24 h p.i., with and without exposure to 20 μM MEC. Mitochondria (amber), Mtb H37Rv (green), and the nucleus (purple) are shown as surfaces. Plots show the surface area (µm2) and volume (µm3) of mitochondria in uninfected and infected BMDMs (n > 500 from 6-8 cells per condition). Data are median with interquartile range. p-values calculated using a one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. UI: uninfected BMDMs, Inf: infected BMDMs; F, G RNA-seq of BMDMs infected with Mtb and treated with 20 µM MEC at 24 h p.i. F OXPHOS gene expression between vehicle-treated and MEC-treated BMDMs; and (G) net enrichment score (NES) calculated by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for the DEGs between MEC- and vehicle-treated infected macrophages; H Redox profile of the intracellular Mtb in the presence of indicated concentrations of MEC at 24 h p.i.; I Antibiotic tolerance in Mtb-infected BMDMs treated with 20 µM MEC and 0.5 mM 2-DG in the presence of 3X MIC of INH (0.375 µg/ml) or MOXI (0.75 µg/ml). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of three biological replicates done in triplicate. p-value determined using a Student’s two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction for comparison between two groups or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

However, these changes in mitochondrial function by 20 μM MEC did not result in the killing of BMDMs infected with Mtb (Suppl. Fig. 16B), likely due to the redirection of metabolism to glycolysis. To interrogate signaling pathways that could explain the metabolic switchover induced by MEC during infection, we performed RNA-seq of Mtb-infected BMDMs treated with MEC and vehicle control (treated with 0.2% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) for 24 h. Mtb-infected BMDMs treated with MEC showed differential regulation of 1088 genes compared to the DMSO control (log2-fold change [FC] >0.6, false discovery rate [FDR] <0.1) (Suppl. Fig. 17A, suppl. data 7). Remarkably, the transcriptional response of MEC-treated BMDMs reversed the expression of pathways elevated in BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced Mtb (Fig. 5F, G). For example, MEC treatment suppressed the NRF2 regulon, Hippo signaling, and OXPHOS genes (Fig. 5F, G, Suppl. Fig. 17B). Down-regulation of a significant repertoire of genes associated with OXPHOS explains the suppression of mitochondrial respiration in Mtb-infected BMDMs upon MEC treatment (Fig. 5A, F). We confirmed these findings by showing that MEC treatment suppresses the pool of TCA cycle intermediates such as citrate/isocitrate, 2-KG, and fumarate without affecting glycolytic metabolites (Suppl. Fig. 18A, B). The lack of deregulation of glycolytic genes and metabolites suggests that glycolysis compensates for diminished mitochondrial respiration. Our data indicate that an MEC-induced metabolic shift is associated with significant changes in the expression of genes controlled by regulators of energy metabolism and redox stress, NRF2 and Hippo signaling.

MEC collapses redox heterogeneity to diminish drug tolerance in Mtb

We then determined whether MEC-mediated reshaping of macrophage metabolism reverses the drug tolerance and redox heterogeneity displayed by intra-phagosomal Mtb. Pre-treatment with MEC abolished the fraction of intra-phagosomal Mtb displaying reductive-EMSH in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5H). Using a pH-sensitive reporter construct (rv2390c’::GFP, smyc’::mCherry62), we confirmed that Mtb is not experiencing acidic pH stress in MEC-treated BMDMs (Suppl. Fig. 16C). Next, we examined whether MEC reduced drug tolerance during infection. BMDMs with or without MEC treatment were infected with Mtb for 24 h and exposed to 3X MIC of INH or MOXI for an additional 48 h before lysis and enumeration of viable counts. We found that the addition of MEC reduced INH tolerance significantly (Fig. 5I; INH: 39 % ± 4 %, INH + MEC: 17 % ± 2 %). A similar decrease in tolerance was observed upon substitution of INH with MOXI (MOXI: 40 % ± 7 %, MOXI + MEC: 15 % ± 4 %) (Fig. 5I). To determine whether the increased ability of INH and MOXI to kill Mtb in macrophages is linked to elevated glycolysis by MEC, we poisoned glycolysis using an inhibitor of the first hexokinase-mediated step in glycolysis, 2-deoxyglucose (2DG)5. Inhibition of glycolysis with 2-DG enhanced bacterial survival in Mtb-infected BMDMs and abrogated the potentiating effect of MEC on lethality induced by INH and MOXI, restoring tolerance comparable to BMDMs treated with antibiotics alone (Fig. 5I). The effects of MEC or 2-DG are driven by changes in macrophage metabolism, as these agents did not alter the OCR or ECAR of extracellular Mtb (Suppl. Fig. 16D–G). Moreover, Mtb remained viable even at high MEC concentrations (320 μM) in 7H9 medium (Suppl. Fig. 16H, I). Our findings imply that increased OXPHOS and suppressed glycolytic flux in Mtb-infected BMDMs induce drug tolerance, which MEC reverses.

Next, we tested Mtb’s response to INH in the presence of MEC in a murine model of infection. Because the pathophysiology of human TB and tolerance to anti-TB drugs are closely recapitulated in C3HeB/FeJ mice63, we aerosol-infected this mouse line with Mtb. At two weeks p.i., animals were treated with MEC for two weeks, followed by treatment with INH, MEC, and INH plus MEC for an additional six weeks, and then we measured the lung bacillary load (Fig. 6A). MEC dose (25 mg/kg/body weight) was based on previous mouse experiments64. As reported earlier, INH monotherapy reduced the bacterial burden from ~106 to ~104 per lung at six weeks (p = 0.0002) of treatment (Fig. 6B). MEC alone showed a marginal (~2.5 fold decrease) effect on bacterial viability over time (Fig. 6B). Relative to the control regimen (INH alone), the addition of MEC decreased lung CFU by ~20-fold after six weeks (p = 0.0001) of treatment (Fig. 6B). The gross and histopathological changes observed in the lungs after six weeks of therapy were correlated to the observed bacillary load (Fig. 6C, D). The extent of lung damage was greater in the untreated (score = 37.5) and MEC-treated animals (score = 35), intermediate in INH-treated animals (score = 17.5), and lowest in the case of the MEC plus INH-treated animals (score = 2.5) (Fig. 6E).

A Strategy for investigating the efficacy of MEC at reducing tolerance against INH in C3HeB/FeJ mice; B Bacterial CFUs counted from lungs at the indicated time-points. Number of animals in each group for the 10 weeks p.i. timepoint are vehicle (n = 9), MEC (n = 10), INH (n = 7), and MEC + INH (n = 10). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D., and the p-value was determined by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test; C Gross pathology of lungs of Mtb-infected mice at 10 weeks p.i across experimental groups; D Hematoxylin and eosin–stained lung sections (after 6 weeks of treatment) from mice infected with Mtb for all experimental groups. Pathology sections show granuloma (G), alveolar space (AS), collapsed parenchyma (CP), and necrotic area (N). All images were taken at 10X magnification; E Granuloma score was calculated from the histopathological lung sections from 5 mice in each group, F Proportions of AM and IM populations in the lungs of animals treated either with vehicle control or with MEC for 3 mice in each group. For (E) and (F), data are expressed as mean ± S.D., and the p-value is determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Since in vitro studies indicate that MEC reduces drug tolerance of intracellular Mtb by enhancing glycolysis and suppressing OXPHOS, we also asked whether MEC stimulates a similar effect in vivo. We examined the proportion of AMs and IMs upon MEC treatment. During lung infection in mice, Mtb resides in glycolytically active IMs and mitochondrially respiring AMs5. Expectedly, treatment of infected mice with the glycolytic inhibitor 2-DG decreased the number of glycolytically active IMs5. We then asked whether MEC alters the proportion of IMs and AMs. In line with the in vitro findings, the proportion of glycolytically active IMs increased, and AMs decreased at six weeks post-MEC treatment (Fig. 6F). Together, these results confirm that adjunct therapy with MEC counteracts drug tolerance by reshaping the metabolism of infected macrophages.

MEC exhibits no adverse interaction with anti-TB drugs

A favorable safety profile, oral pharmacokinetics with the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, and years of clinical use in humans for treating nausea and vertigo65,66 make MEC a good candidate for developing new therapeutic combinations for treating TB. We assessed the pharmacological compatibility of MEC by measuring its interaction with clinically relevant, first-line anti-TB drugs (isoniazid or H, rifampicin or R, ethambutol or E, and pyrazinamide or Z) given as a combination. We also performed a single-dose pharmacokinetic interaction by administering HREZ orally at the human equivalent doses with and without MEC (25 mg/kg/body weight, intraperitoneally [ip]) in mice. We have included an additional group of mice that was dosed with MEC (25 mg/kg/body weight,ip) to compare the PK profile of MEC in the presence of an HREZ combination (Fig. 7A). Plasma and lung homogenates were analyzed for individual drugs using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and parameters such as maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUClast) were quantified as a ratio for single-treatment groups vs. the combination (Fig. 7B–F). PK profiles revealed no to moderate drug-drug interaction when MEC was administered with HREZ. Cmax and AUClast for MEC, when administered alone, were 0.31 μg/ml and 1.04 μg/ml*h, respectively, which increased to 0.733 μg/ml and 2.36 μg/ml*h, respectively, when administered along with HREZ. Similarly, Cmax and AUClast for H/R/E/Z administered with MEC were 5.25 μg/ml and 13.8 μg/ml*h for H, 8.8 μg/ml and 130.18 μg/ml*h for R, 1.92 μg/ml and 9.69 μg/ml*h for E and 63.1 μg/ml and 216.99 μg/ml*h for Z, respectively (Fig. 7B–G). The plasma PK profiles of HREZ remained unchanged in the presence of MEC. Comparative ratios of Cmax and AUClast for H, R, and Z with and without MEC were close to 1 except for E, which showed minor interaction (Cmax ratio: 1.41 and AUClast: 1.22) (Fig. 7G). The average concentration of drug permeation in the lungs was determined at 6 and 24 h post-treatment, and the lung accumulation of HREZ in the presence or absence of MEC remained comparable (Fig. 7H). Similarly, HREZ did not affect lung deposition of MEC at 6 and 24 h post-treatment (Fig. 7H). Overall, the PK results suggested no adverse interactions between the HREZ plus MEC combination vs. HREZ alone. Taken together, our study demonstrates an effect of MEC on drug tolerance, no significant drug-drug interaction with HREZ, and a potentiating effect of MEC on INH. With over 50 years of safe clinical use of MEC for nausea and vertigo55,64,65, our findings suggest repurposing MEC for developing a new combination for shortening therapy time for TB.

A Three groups of treatment in BALB/c mice used in the pharmacokinetic study: MEC alone, front-line anti-TB combination therapy (HREZ), and combination (MEC + HREZ); B–F Line plots indicate pharmacokinetic profiles of MEC and individual drugs of the anti-TB therapy regimen, analyzed individually and in the presence of each other in the plasma of animals. Differences were non-significant by the two-tailed Mann-Whitney test (p > 0.05). G Ratios of Cmax and AUClast of individual drugs or a combination with MEC to analyze drug-drug interactions. Doses used are the following: MEC, 25 mg/kg body weight, ip; H, 25 mg/kg body weight, per os (po); R, 10 mg/kg body weight, po; E, 200 mg/kg body weight, po; Z, 150 mg/kg body weight, orally; BDL, below the detection limit. All data are means ± S.D. of concentrations at each time point of samples in triplicate (n = 3 animals per group), H Lung deposition of MEC alone and combined with anti-TB drugs at 6 h and 24 h post-ip administration. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Drug tolerance in Mtb is often linked to reduced metabolism under stress67, as seen with IFNγ activation and nitrosative stress in murine macrophages4,7. However, human studies show that drug tolerance can also arise in metabolically active Mtb populations19,20,22,68,69,70,71, enabling persistence and relapse post-treatment72,73. Consistently, we and others have observed drug tolerance in actively replicating Mtb within naïve macrophages20,21, driven by energy-dependent processes like efflux, sulfur metabolism, and redox regulation (e.g., trans-sulfuration, Fe-S cluster formation, and mycothiol synthesis)20,21,74. Yet, how macrophage physiology engages with the pathogen to power bacterial sulfur and redox metabolism for drug tolerance remains unclear.

In this study, we used a fluorescent Mtb redox reporter strain to dissect the link between macrophage bioenergetics and redox-driven drug tolerance in actively replicating Mtb. This reporter, characterized previously9,21,23,75, reveals functional heterogeneity among BMDMs during early infection—reflected in transcriptional profiles, energy metabolism, and mitoROS. Such variability aligns with known pre-existing heterogeneity in macrophage populations, including differences in iNOS expression11, mitochondrial function and phagosomal pH76,77,78, all of which can shape the redox environment of intraphagosomal Mtb. Additionally, intrinsic Mtb heterogeneity, such as variable DNA damage responses, asymmetric division, and stochastic KatG expression, can further influence macrophage physiology and drive diverse bacterial redox states19,71,79,80.

Macrophage metabolism during Mtb infections is complex, with studies reporting diverse phenotypes ranging from balanced glycolysis and OXPHOS81, to elevated glycolysis82,83, and suppression of both pathways37,84. Our findings add to this by uncovering distinct macrophage subsets with varying glycolysis/OXPHOS ratios, potentially explaining inconsistencies in earlier reports. Prior studies primarily analyzed bulk murine BMDMs or human MDMs37,84, obscuring underlying heterogeneity within the BMDM population. We confirmed that Mtb infection reduces OXPHOS in bulk BMDMs (Suppl. Fig. 19). However, by phenotyping infected BMDMs with a redox reporter strain prior to flow sorting, RNA-seq, and XF analysis, we identified distinct subsets with differing profiles in glycolysis, mitoROS, and OXPHOS.

In BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced bacteria, glucose fuels OXPHOS instead of converting to lactate, unlike in EMSH-oxidized or bystander cells. Blocking glucose-linked OXPHOS by impairing the transport of pyruvate from cytosol to mitochondria induces oxidative stress and drug lethality in Mtb, while promoting mitochondrial OCR enhances reductive shift and drug tolerance. Bioenergetic and redox similarities between BMDMs harboring EMSH-oxidized Mtb and bystanders are consistent with our earlier work showing that extracellular vesicles derived from Mtb-infected macrophages contain soluble factors capable of inducing an oxidative shift in bystander macrophages85. Moreover, infected cells release cytokines, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and apoptotic vesicles to reprogram neighboring uninfected (bystander) macrophages towards a more glycolytic, oxidative and inflammatory phenotype86,87,88,89.

Within the framework of Mtb infection, studies have reported that Mtb induces glycolysis in the lungs of infected mice90 and lung granulomas from patients with active TB91. Interestingly, IFNγ-dependent control of Mtb relies on the induction of glycolytic enzymes by HIF1α in macrophages92. Despite the known role of glycolysis in restricting Mtb in these studies, the pathogen manages to shift the environment in its favor for persistence and drug tolerance during infection. Our findings raise the possibility that metabolic heterogeneity within macrophage populations regulates Mtb’s redox metabolism for survival and drug tolerance. Local factors found in lung macrophages may coordinate the metabolic network of macrophages during infection. In this context, a study using TB-pleural effusion (TB-PE) as a physiologically relevant fluid found in the human respiratory cavity showed that TB-PE ex vivo shifts the glycolysis-based metabolic program of macrophages to OXPHOS93. Given that a similar metabolic phenotype is exhibited by macrophages directly isolated from the pleural cavity of TB patients and lung biopsies of TB-infected non-human primates94, we hypothesize that host energy metabolism and its correlation with redox-linked changes in sensitivity to anti-TB drugs, revealed by our study, is likely to be relevant in clinical settings of human TB.

Mtb experiences oxidative stress in glycolytically active BMDMs likely due to elevated mitoROS, which triggers NADPH oxidase recruitment to mycobacterial phagosomes and promotes xenophagy23,38. Reduced TCA cycle and ETC activity in these BMDMs likely limits NADH production and electron flow, leading to increased RET-ROS and oxidative shift in Mtb. Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling alters respiratory complexes and generates RET-ROS at complex I95. Supporting this, TLR signaling, known to drive RET-ROS at complex I, is modestly upregulated in our RNA-seq of glycolytically active BMDMs. Our data revealed differential activation of the Hippo signaling pathway in Mtb-infected BMDMs. Hippo signaling promotes phagosomal and mitochondrial ROS by bringing mitochondria closer to phagosomes96, and helps maintain redox balance in macrophages. MST1/2 kinases, acting as ROS sensors, also stabilize NRF2 to limit excessive ROS97. BMDMs with low mitoROS and drug-tolerant Mtb showed upregulation of Mst1 and Nrf2, and Nrf2 suppression reversed this phenotype, suggesting MST-NRF2 signaling reduces ROS, promoting a reductive shift and drug tolerance in Mtb. This Nrf2 signature in drug-tolerant BMDMs aligns with prior reports in Mtb-infected AMs in mice25 and active TB patients98. Early Nrf2 activation suppresses inflammation and nitric oxide production25,99,100, creating a favorable niche for Mtb replication, reductive stress, and drug tolerance. Moreover, type I IFN signaling suppresses Mtb replication by enhancing glycolysis and ROS84, while Nrf2 activation reverses this response43. This mechanism further explains the observed EMSH-reduced redox state in BMDMs with high Nrf2 expression during Mtb infection. NRF2-dependent induction of cystine-glutamate antiporter (xCT) may enhance intracellular cysteine levels by importing cystine101, promoting a reductive EMSH shift in Mtb through utilization of host-derived cysteine into mycothiol. While cysteine boosts anti-TB drug activity75,102, Mtb counter this by channeling cysteine into Fe-S clusters, H2S, and methionine metabolites in EMSH-reduced bacteria21. The observed NRF2 activation in mice and TB patients25,98,103 suggests a conserved link between NRF2 signaling, host metabolism, and redox-driven drug tolerance in human TB. Lastly, while NRF2 responds to multiple signals, a known Mtb-secreted virulence factor, Esat-6, promotes NRF2 activation and antioxidant responses in macrophages104. Given that the Esat-6 function depends on acidic pH105,106, and that EMSH-reduced Mtb are enriched in acidic macrophages21, we propose that pH-dependent activation of the Esat-6 pathway may contribute to Nrf2 induction in BMDMs harboring EMSH-reduced Mtb.

Our study highlights the potential to target redox-mediated drug tolerance in Mtb by modulating host metabolism. Disrupting macrophage antioxidant responses may enhance antibiotic efficacy; for instance, NRF2 activator-loaded nanoparticles have improved S. aureus clearance in macrophages107. A similar approach using NRF2 inhibitors could potentiate anti-TB drugs. However, as redox balance is critical beyond macrophages, including cell signaling, off-target effects must be considered108,109. We show that shifting macrophage metabolism from OXPHOS to glycolysis sensitizes intracellular Mtb to antibiotics. Using the FDA-approved drug MEC, which inhibits OXPHOS via the Kennedy pathway by accumulating phosphoethanolamine [57, we observed enhanced antibiotic killing. Although underexplored in infections, host metabolic modulation is a proven strategy in cancers110, myocardial infarction111, and stroke112. In this context, a recent adjunctive human clinical trial using an antidiabetic drug (metformin) in combination with anti-TB drugs showed encouraging results in reducing inflammation and lung tissue damage113. MEC readily crosses the blood-brain barrier114,115, making it a candidate for TB meningitis treatment. MEC has been used safely for >50 years for the treatment of nausea and vertigo65,66. We found no adverse interaction of MEC with first-line anti-TB drugs in mice. Whether currently approved doses of MEC achieve the required concentration in plasma and lung required for safe adjunctive effects with anti-TB drugs needs further experimentation. Safety studies are important because MEC has a variable impact on OXPHOS in different cell types55, and the associated increase in RET-ROS has been linked to necrosis of Mtb-infected macrophages41. Studies in animals, including non-human primates, have shown that higher doses of MEC can be tolerated116,117. Nonetheless, preclinical studies of efficacy and toxicity are required to determine optimal dosing and safety regimens before evaluating the utility of MEC as an adjunct to anti-TB drugs in humans. Together, our findings underscore the need to consider macrophage heterogeneity and bioenergetic state when developing host-directed adjunctive strategies for TB treatment. While targeting non-growing Mtb within the caseous centers of granuloma is being actively pursued in the TB field118,119,120,121,122, the heterogeneity of the host macrophages (AM, IM, and BMDMs) and its impact on bacterial physiology and drug tolerance is only recently been getting attention. Adjuvant strategies using host-directed therapies to potentiate the efficacy of anti-TB drugs through targeting bioenergetic shifts in macrophages, such as those reported for MEC, represent an important approach for future studies.

Methods

Mtb culture conditions

H37Rv strain of Mtb and H37Rv expressing Mrx1-roGFP2 (Mtb-roGFP2) were used in the study. The bacteria were grown to log phase in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 10% albumin/dextrose/saline (ADS) or 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose catalase (OADC) supplement, 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80, and 50 μg/ml hygromycin B (only for Mtb-roGFP2).

Bone Marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) culture and in vitro assays

BMDMs were isolated from female C57BL/6 J mice and cultured in DMEM (Cell Clone) supplemented with 10% FBS (Cell Clone), 30 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, BioLegend), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma Aldrich), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma Aldrich), 10 mM HEPES buffer (Sigma Aldrich), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich) at 37 °C for 6 d. BMDM purity was checked by staining with monoclonal antibodies against MerTK (Thermo Fischer, (DS5MMER) Alexa Fluor 700) and CD64(anti-mouse, BioLegend). For FACS-based experiments, BMDMs were infected with Mtb-roGFP2 at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 10 for 3 h, before extracellular bacteria were removed by washing thrice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS). Fresh OptiMEM medium (Thermo-Fischer) supplemented with 5% FBS and 30 ng/ml M-CSF was added, and cells were incubated for different time points according to experimental requirements.

For CFU determination, cells were infected at a moi of 2 with Mtb H37Rv for 3 h and lysed with 0.05% SDS in water and plated on 7H11 agar supplemented with 10% OADC at different time points post-infection. Cells were incubated in OptiMEM medium supplemented with 5% FBS and 30 ng/ml M-CSF post-infection, and fresh medium was added every 48 h.

Redox profiling of intracellular Mtb-roGFP2

At different time points post-infection, cells were washed and scraped off in DPBS and acquired using a BD FACS Aria Fusion flow cytometer and the data were analyzed using BD FACS Diva software. At least 10,000 GFP-positive events were analyzed by excitation at 405 and 488 nm with a constant emission (510 nm) to determine EMSH under different treatment conditions. Events were gated based on a previously developed strategy23, where infected BMDMs were treated with 10 mM CHP for complete oxidation or 100 mM DTT for complete reduction of the biosensor.

Flow sorting of macrophages infected with Mtb-roGFP2

Post-infection at the required time points, the growth medium was removed from the cells, followed by washing with DPBS supplemented with 2% FBS. Fresh DPBS was added, and the cells were gently scrapped off using a cell scrapper. The cell suspension was centrifuged, and cells were resuspended in DPBS and passed through a 40-micron (40μ) cell strainer. Cells were sorted using BD FACS Aria Fusion flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) employing the 405 nm and the 488 nm lasers into EMSH-reduced, -basal, -oxidized and bystander sub-populations. Cells were gated using 10 mM CHP (oxidant) and 100 mM DTT (reductant) into EMSH-oxidized (~-240 mV) and -reduced (~-300 mV), respectively. The GFP-negative population was gated as bystanders. The sorting was done at a “four-way purity” setting, and the purity of sorting was assessed by post-sort analysis. The uninfected cells were also treated with the same conditions as the infected and mock-sorted to eliminate differences that may arise due to cell sorting.

RNA isolation, library preparation for RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing was done at the Next-Gen Genomics Facility at the National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bangalore. Total RNA was extracted from FACS-sorted macrophage sub-populations using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit. All RNA samples (three biological replicates in each group) passed quality control analysis on the Agilent 4200 TapeStation system. rRNA depletion was done using NEBNext® rRNA Depletion Kit (Human/Mouse/Rat) with RNA Sample Purification Beads (E6350X). Directional poly-A + RNA-sequencing libraries were generated with the NEBNext® Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep with Sample Purification Beads (E7765L). Libraries were sequenced on a NovaSEQ6000 (Illumina) using a paired-end sequencing format with read length of 100 bp.

RNA-Seq Data Analysis for macrophage subpopulations

RNA-Seq data were preprocessed to obtain read counts using the “htseq” pipeline in Python123 using the reference genome of Mus musculus (GCF_000001635.27_GRCm39). Differential gene expression analysis was performed on the different subgroups with a base mean value of expression greater than 1, log2 fold change greater than 0.6 and an adjusted p-value less than 0.1 using the DESeq2 pipeline124. To characterize the differentially expressed genes between the oxidized and reduced populations, DESeq2 was used to identify genes that were specifically upregulated in each category with respect to the other category using the above criteria. Similarly, gene signatures pertaining to bystander, reduced and oxidized populations with respect to the reference uninfected genes were also calculated using the above criteria. Gene expression values for genes common with differentially expressed genes and different gene signatures (see gene lists section) were plotted as heatmaps using the cluster map function in the seaborn package after conversion of read counts to transcripts per million (TPM), followed by z-scoring across the experimental conditions to avoid biases due to absolute values of gene expression. Complete analytical details and the transcriptomic data are uploaded to the NCBI GEO database, accession number GSE283664.

Gene lists and overlap analysis

Gene list belonging to the oxidative phosphorylation pathway was obtained from the MSigDB database125. Gene list belonging to the antioxidant pathway was obtained from the Gene Ontology Molecular Functions subcategory. The Hippo signaling pathway was obtained from Reactome gene sets through the MSigDB database125. M1 and M2 specific macrophage polarization signatures were obtained from GSE5099126 through the MSigDB database. Gene signatures characterizing the transcriptomic states post 4 h and 24 h were obtained from24. AM and IM-specific gene signatures upon infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis were obtained from25 (greater than log2 fold change). Finally, gene signatures belonging to the NRF2 pathway were obtained from25. Gene lists corresponding to NRF2 chip-seq performed on peritoneal macrophages with differential peaks and associated NRF2 motifs were obtained from GSE7517725,44. Overlap analysis between the different gene signatures and pathways was performed using the ggVennDiagram module in R. Quantification of pathway activity followed by z-normalization was performed using the ssGSEA function in the gseapy library in Python127.

MIC and MBC determination

Mtb H37Rv were cultured in 7H9 + ADS medium till mid-log phase (~0.4-0.6 OD600), post which ~106 Mtb were seeded in 200 ul 7H9 + ADS medium without Tween-80. After 5 days of incubation at 37 °C, 20 μL of Alamar blue was added, and the plates were re-incubated for 24 h. The fluorescence readings were recorded in a Spectramax M3 microplate reader with excitation at 530 nm and emission at 590 nm. Percentage inhibition was calculated based on the relative fluorescence units and the minimum concentration that resulted in at least 90% inhibition (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration or MIC).

For determining the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), 20μl of cells from the MIC plate were spotted on 7H11-agar plates supplemented with 10% OADC. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 3 weeks, and MBC was defined as the concentration where no bacterial colonies were visible on the plates.

ROS measurement assays

For ROS measurement assays, BMDMs were seeded in 24-well plates (0.3 million cells/well). To measure cellular ROS, cells were stained with 2.5 μM CellROX Deep Red dye (Thermo Fischer Scientific-Life technologies) for 30 min in DPBS. As positive control, cells were pretreated with 100 μM Menadione (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 h before staining. For mitochondrial ROS measurement, cells were stained with 2.5 μM MitoSOX Red dye (Thermo Fischer Scientific-Life technologies) for 30 min in the Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) buffer. As a positive control for mitochondrial ROS measurement, cells were treated with 20 μM Antimycin A (Sigma Aldrich) for the last 15 min of staining. After completion of staining, cells were washed thrice with DPBS, and fluorescence was assessed using BD FACS Aria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) at prescribed excitation and emission maxima CellROX DeepRed: 644/665; MitoSOX Red: 544/610.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of Nrf2 in BMDMs

BMDMs were seeded in a 6-well plate after 6 days of differentiation. Post reattachment, the medium was replaced with OptiMEM medium with 40 nM Nrf2-targeting siRNA (siNRF2) or scrambled siRNA negative control (siSCR) and 4 μL Lipofectamine 3000 per well (Thermo-Fischer Scientific). The siRNAs were procured from the Integrated DNA Technologies Predesigned Dicer-Substrate siRNA (DsiRNA). The sequence of siRNA against Nrf2 was:

Sequence: rGrCrG rArUrG rArArU rUrUrU rArUrU rCrUrG rCrUrU rUrCA T

Sequence: rArUrG rArArA rGrCrA rGrArA rUrArA rArArU rUrCrA rUrCrG rCrCrA

24 h post-transfection, cells were infected with Mtb-roGFP2 or Mtb H37Rv according to experimental requirements and downstream assays were performed.

qRT-PCR

Infected BMDMs were lysed in the RLT buffer (Qiagen), and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini Kit. Isolated RNA was further treated with DNase I (Thermo Scientific) to remove any residual genomic DNA. 500 ng of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA for downstream qRT-PCR analysis using the iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad). CFX96 RT-PCR System, BioRad and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad) were used to assess gene expression, and the primers used for qRT-PCR for different genes were as follows:

Nrf2 FP 5’-CAGCATAGAGCAGGACATGGAG-3’

Nrf2 RP 5’-GAACAGCGGTAGTATCAGCCAG-3’

Gstm1 FP 5’-TGTTTGAGCCCAAGTGCCTGGA-3’

Gstm1 RP5’-TAGGTGTTGCGATGTAGCGGCT-3’

Gclc FP 5’-ACACCTGGATGATGCCAACGAG-3’

Gclc RP 5’-CCTCCATTGGTCGGAACTCTAC-3’

Pik3cb FP5’-CAGTTTGGTGTCATCCTGGAAGC-3’

Pik3cb RP5’-TCTGCTCAGCTTCACCGCATTC-3’

Gapdh FP5’-CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG-3’

Gapdh RP5’-ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG-3’

Mouse Gapdh expression (Ct values) was used as the normalization control in all cases. All primers were designed using the Origene Primer design tool.

Antibiotic tolerance assay

BMDMs were infected at a moi of 2 with Mtb H37Rv for 3 h. Extracellular bacteria were removed by washing the cells thrice with DPBS, and treatment was initiated (SFN, MEC, glucose/galactose, UK5099). At the required time points, cells were lysed with 0.05% SDS and the lysate was plated on 7H11 agar plates supplemented with OADC after serially diluting the lysate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C and CFUs were enumerated after 3 weeks.

MTT assay

BMDMs were seeded in a 96-well plate (30000 cells/ well), and upon attachment to the surface, they were treated with different concentrations of drugs for 24 h. Post-treatment, 0.25 mg/ml (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added to the cells and incubated for 2.5 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. To assess survival, absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a Spectramax plate reader. Untreated cells or cells treated with 50% DMSO for 10 min were taken as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurement/Modified Mitostress test

Before the assay, the Seahorse XFp Cell Culture plate was coated with 15 μl Cell-Tak reagent (5 μl Cell-Tak, 145 μl 0.1 N sodium bicarbonate at pH 8) for 30 min at 37 °C. After coating, BMDMs were seeded at a density of 40000 cells per well in the cell culture plate in Agilent Seahorse XF Base Medium supplemented with 2mM L-Glutamine, 10 mM D-Glucose and 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate.

Three OCR readings were taken under basal conditions, followed by periodic addition of oligomycin (2 μM) and a combination of rotenone (2 μM) and antimycin (4 μM). Measurements were taken using an 8-well Seahorse XFp analyzer (Agilent Technologies). The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism ver. 10. Basal respiration was calculated by subtracting the non-mitochondrial OCR (lowest reading after adding rotenone and antimycin) from the last reading before oligomycin injection. ATP production was calculated by subtracting the lowest reading after oligomycin injection from the previous reading before oligomycin injection. Proton leak was calculated by subtracting the non-mitochondrial OCR from the lowest reading after oligomycin injection.

To assess respiratory parameters in the presence of 10 mM glucose or galactose, cells were incubated with either sugar source in the medium for 24 h, after which the modified mitostress test was performed. For different inhibitors/drugs, treatment was done in regular culture plates post, and the cells were seeded in the Seahorse cell culture plates for XF analysis.

Extracellular Acidification Rate (ECAR) measurement

BMDMs were seeded in a Cell-Tak-coated Seahorse XFp Cell Culture plate (40000 cells per well) in Agilent Seahorse XF Base Medium supplemented with 2mM L-Glutamine. The standard Agilent Seahorse Glycolytic Stress test was run according to the manufacturer’s protocol, wherein three ECAR readings each were measured upon sequential addition of 10 mM D-Glucose, 2 μM oligomycin and 100 mM 2-DG. For different drugs, macrophages were seeded directly into the XFp plates, and the glycolysis stress test was run. Glycolysis was calculated by subtracting the lowest reading before glucose injection (non-glycolytic acidification) from the highest reading post glucose injection. Glycolytic capacity was calculated by subtracting the lowest reading before glucose injection from the highest reading after oligomycin injection.

OCR and ECAR measurements of Mtb

Log-phase Mtb cultures (OD600 = 0.6 to 0.8) were incubated in 7H9 medium containing the nonmetabolizable detergent tyloxapol (MP Biomedical) and lacking ADS or a carbon source for one day. These cultures were then passed 10 times through a 26-gauge syringe needle to remove Mtb clumps. The resulting single-cell suspension of bacteria at 4 × 106 cells/well was added to a Cell-Tak-coated XF culture plate. Measurements were performed using a Seahorse XFp analyzer with cells in unbuffered 7H9 growth medium (pH 7.35 lacking monopotassium phosphate and disodium phosphate). OCR and ECAR measurements were recorded at multiple timepoints upon addition of 10 mM glucose, 20 μM MEC, 1mM 2-DG, and 2 μM CCCP delivered automatically through the drug ports of the sensor cartridge.

Mitochondrial membrane polarization measurement

~0.3 million BMDMs in a 24-well plate were infected with Mtb H37Rv, and at 24 h p.i., cells were washed with DPBS and stained with 2 μM JC-1 dye (Thermo Scientific). After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, cells were washed three times with DPBS, and fluorescence was measured using a BD FACS Aria Fusion flow cytometer at 485/535 nm and 550/600 nm excitation/emission wavelengths. Cells were treated with 50 μM FCCP for 30 min during staining as a positive control.

BCECF staining

BMDMs were infected with Mtb at a moi of 2 and 24 h p.i., treated with 5 μM BCECF, AM (2’,7’-Bis-(2-Carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-Carboxyfluorescein, Acetoxymethyl Ester) stain in DPBS for 30 min at 37 °C. Post incubation, cells were washed thrice with DPBS and fluorescence was measured using a BD FACS Aria Fusion flow cytometer at 485/535 nm and 405/510 nm excitation/emission wavelengths. For making the standard curve, cells were treated with DPBS set at different pH levels for 30 min in the presence of 10 μM nigericin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 μM valinomycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

LC-MS/MS analysis of glycolytic and TCA intermediates

Steady-state metabolite levels were quantified using previously described protocols128. In brief, metabolites were extracted, resuspended in required solvents (50% methanol for TCA cycle intermediates and water for sugar phosphates) and separated on a Synergi 4-µm Fusion-RP 80 Å LC column (100 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex) using a Shimadzu Nexera UHPLC system. TCA cycle intermediates were derivatized prior to separation128. Two solvent systems were employed: for TCA intermediates—Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water, and Solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in methanol; for sugar phosphates—Solvent A was 5 mM ammonium acetate in water, and Solvent B was 100% acetonitrile. Chromatographic flow parameters followed previously established settings128. Metabolite detection was performed using an AB Sciex Qtrap 5500 mass spectrometer with data acquired via Analyst 1.6.2 software (Sciex). TCA intermediates were analyzed in positive ion mode, while sugar phosphates were measured in negative ion mode. Quantification was carried out by calculating peak areas using MultiQuant software (version 3.0.1).

Mitochondrial imaging

For imaging of murine BMDMs, bone marrow was obtained from the femurs of 6- to 8- 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River). Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by EPFL’s Chief Veterinarian, by the Service de la Consommation et des Affaires Vétérinaires of the Canton of Vaud, and by the Swiss Office Vétérinaire Fédéral under license VD 3434. Bone marrow was cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 20% L929-cell-conditioned medium (as a source for M-CSF) for 7 days. No antibiotics were used in the cell culture media for all cell types to avoid activation of macrophages or inhibition of Mtb growth.

Differentiated BMDMs were seeded in 24-well plates (Ibidi) suitable for high-resolution imaging. A 1 mL aliquot of a culture of the Mtb H37Rv mCherry strain grown to exponential phase (OD600 0.3–0.5) was centrifuged at 5000 g for 5 min at room temperature, the supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in the macrophage media. A single cell suspension was generated via filtration through a 5-μm syringe filter (Millipore). BMDMs were infected with a 200-fold dilution of the single-cell suspension for 4 h. Infected cells were washed with pre-warmed PBS to remove extracellular bacteria and incubated in the presence or absence of 20 μM MEC for 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

For staining of mitochondria, cells were washed with a pre-warmed medium and incubated with 50 nM MitoTracker Deep Red FM (Invitrogen, M22426) for 1 h. Stained cells were then washed to remove excess dye and fixed with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for a minimum of 2 h. Fixed cells were washed to remove excess fixative and stained with Hoechst (Thermo Fisher) at 5 μg/mL for 30 min at room temperature for visualizing nuclei.

Confocal images were acquired on a Leica SP8 inverted microscope using a 63x oil objective (NA = 1.4). Z stacks were subsequently deconvolved using the Huygens Professional Deconvolution software (Scientific Volume Imaging). ImageJ and Imaris 10.1 (Bitplane) were used to quantify mitochondrial volume and surface area. Imaris was also used for rendering 3D images.

RNA isolation, sequencing and data analysis for MEC-treated macrophages

Differentiated BMDMs were infected with Mtb-roGFP2 at a moi 10 for 3 h, after which the extracellular bacteria were removed by washing thrice with DPBS. Post-infection, cells were treated with 0.2% DMSO (vehicle control) or 20 μM MEC hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich). At 24 h p.i., infected BMDMs from each condition were flow-sorted using GFP as a marker for infection and total RNA was isolated and subjected to sequencing as explained earlier.

Raw reads were obtained as fastq files. The reference genome sequence and annotation files for mouse (Mus musculus, GCF_000001635.27_GRCm39) were downloaded from the NCBI ftp (“ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov”). The raw read quality was checked using the FastQC software (version v0.11.5), and the differential gene expression (DGE) analysis was done using the EdgeR package in R129. Complete analysis details and the transcriptomic data are uploaded to the NCBI GEO database, accession number GSE283874.

In vivo mice experiment