Abstract

Plasmid-mediated transmission can account for half of carbapenem-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) dissemination, underscoring the need to identify genetic determinants of plasmid persistence in the hospital setting. From 1,088 CPE isolates detected through nationwide surveillance in Singapore over five years, 1,115 closed carbapenemase-producing plasmids were identified and clustered, of which 92.5% (n = 1031) were grouped into 48 plasmid clusters (PCs). The most common plasmid genotypes were PC1 and PC2. Of 389 isolates carrying blaKPC-2-positive PC1 plasmids and 283 isolates carrying blaNDM-1-positive PC2 plasmids, 236 (60.7%) and 168 (59.4%) putatively acquired the carbapenemase gene via plasmid-mediated horizontal transmission, whereas 153 (39.3%) and 115 (40.6%) putatively acquired the carbapenemase gene via clonal lineage-dependent vertical transmission, respectively. Less abundant plasmids showed distinct inserted genomic regions encoding genes related to heavy metal and formaldehyde detoxification not found in predominant plasmids. Our data suggest that PC1 and PC2 genotypes are better adapted for stable propagation of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1, respectively, during inter-patient clonal spread and across multiple species (and sequence types) compared to other genetic settings. We propose that a crucial factor enabling evolutionarily successful carbapenemase plasmid genotypes to achieve hyperendemicity in the population is the maintenance of conserved genomes, thus minimizing fitness costs to their hosts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid global dissemination of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) poses an urgent public health threat. CRE are resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics and frequently carry mechanisms conferring resistance to other antimicrobial classes, limiting treatment options and resulting in poor outcomes for infected patients1. Consequently, they have been listed as top-priority critical pathogens by the World Health Organization2. Among the various types of CRE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) constitute the largest subset and wield the greatest epidemic potential, as carbapenemase production typically confers resistance without requiring additional chromosomal mutations or accessory mechanisms3. Crucially, in addition to clonal spread of resistant lineages, carbapenemase gene transmission can occur by horizontal gene transfer via mobile plasmids4,5,6.

The ability of plasmids to carry multiple antibiotic-resistance genes and be mobilized across bacterial cells of the same or different species via conjugation render them central to the molecular epidemiology of CPE7,8,9. As with many countries, the incidence of CPE continues to rise in Singapore despite intensive infection-prevention efforts10. Previous work from our group established that plasmid-mediated transmission accounted for half of CPE dissemination at the population level11.

Short-read sequencing, although widely used for genomic surveillance of high-risk bacterial clones through approaches such as reference-based mapping12, is suboptimal for high-resolution tracking of plasmids due to their structural plasticity and recombinant nature, which complicate accurate assembly. We employed hybrid assembly on both long- and short-read whole genome sequences to recontruct complete circularized plasmid genomes for all 1047 clinical and surveillance CPE isolates detected through a nationwide surveillance programme in Singapore over a five-year period, enabling analysis of carbapenemase gene transmission in the context of endemic co-circulation of four of the five most clinically-relevant carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes, namely Ambler class A Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) enzymes, class B metallo-β-lactamases of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM) and imipenemase (IMP) groups, and class D oxacillinase (OXA) variants13.

Using a method of clustering plasmids based on k-mer similarity, we were able to identify and resolve the structural and genetic features of diverse carbapenemase plasmid types. In addition, the depth and duration of sampling of this cohort, which reflected interlinked bacterial communities, provided the unique opportunity to analyse the evolution of carbapenemase plasmids and to identify genetic determinants of plasmid persistence in the hospital setting.

Results

Disposition of isolates

We had previously conducted a retrospective cohort study11 involving all six multi-disciplinary acute-care public hospitals, providing approximately 80% of inpatient medical care14 in Singapore (estimated population size, 5.5 million in 2015). From September 6, 2010 to April 28, 2015, 1251 CPE isolates (from 791 patients) confirmed by both genomic and phenotypic methods were collected across participating study sites. Hybrid assembly reconstructed whole genomes for 1088 isolates sampled from 705 patients, for which 1115 closed carbapenemase-producing plasmids were identified (Supplementary Fig. 1). Of the 1088 isolates, 20 isolates carried two different carbapenemase genes on separate plasmids, and 2 isolates carried two different carbapenemase genes on the same plasmid. Details on carbapenemase gene co-carriage can be found in Supplementary Data 1. The majority of isolates were K. pneumoniae (n = 486, 44.7%), followed by Escherichia coli (n = 339, 31.2%) and Enterobacter cloacae (n = 145, 13.3%). One hospital accounted for 67.5% (n = 753) of the isolates, in which K. pneumoniae (n = 323, 42.9%), E. coli (n = 232, 30.8%), and E. cloacae (n = 106, 14.1%) were similarly the predominant three species. The complete distribution of isolates by species and hospital is provided in Supplementary Table 1. E. coli ST131 (n = 64), K. pneumoniae ST14 (n = 50), and E. cloacae ST93 (n = 32) were the three most common sequence-types (ST), accounting for 18.9%, 10.3% and 22.1% of the respective species (Supplementary Table 2).

Differences in epidemiology between study sites could potentially be due to varying capacity per site, ranging from 300 to 1600 beds. Two hospitals were academic medical centers with solid organ and stem cell transplant units and four were teaching hospitals with academic affiliations; these factors, in addition to location of the study site (e.g., proximity to mature housing estates, city centre, or industrial areas), could have some influence on inpatient demographics and case mix.

Distribution of carbapenemase genes and classification of the 1115 closed carbapenemase-positive plasmids

Across 1115 closed plasmids, 15 carbapenemase genes were detected, most commonly blaKPC-2 (n = 477, 42.8%), followed by blaNDM-1 (n = 434, 38.9%), blaOXA-181 (n = 60, 5.4%), blaOXA-48 (n = 41, 3.7%), blaIMP-1 (n = 22, 2.0%), blaOXA-232 (n = 21, 1.9%), blaNDM-7 (n = 20, 1.8%), blaNDM-5 (n = 18, 1.6%), blaNDM-4 (n = 6, 0.5%), blaNDM-9 (n = 4, 0.4%), blaOXA-23 (n = 4, 0.4%), blaIMP-4 (n = 4, 0.4%), blaIMP-26 (n = 2, 0.2%), blaVIM-4 (n = 1, 0.1%), and blaKPC-6 (n = 1, 0.1%). blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 were distributed across all six study sites (Supplementary Table 3). Classification of the 1115 closed plasmids by replicon typing assigned majority (n = 898, 83.8%) of the plasmids to a single plasmid incompatibility (Inc) group; the remaining plasmids were found to carry multiple replicons. The predominant replicon types identified were IncU (n = 475, 42.6%), IncN (n = 304, 27.3%), IncC (n = 100, 9.0%), and IncL/M (n = 79, 7.1%) Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 4). Majority of the plasmids were relaxase-encoding (n = 1005, 90.1%), for which MOB-typing identified the predominant classes to be MOBP (n = 503, 45.1%), MOBF (n = 381, 34.2%), and MOBH (n = 104, 9.3%) (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 5).

A Classification of plasmids by replicon typing. The asterisk indicates that the named Inc group is detected with multiple replicon types. B Classification of plasmids by MOB-type. C Heatmap showing the plasmids grouped into 48 plasmid clusters based on pairwise k-mer (21 bp) similarity. Plasmid clusters were named according to size, with PC1 comprising the most plasmids. The five largest clusters (PC1, PC2, PC3, PC4, and PC5) are annotated.

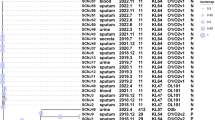

Plasmid clustering based on k-mer similarity

Carbapenemase-encoding plasmids were clustered based on pairwise k-mer (21 bp) similarity. To assign plasmids to clusters, we built an undirected similarity network in R with igraph (v1.6.0): each plasmid was represented as a node and an edge was drawn between any two plasmids whose 21-mer Jaccard similarity was ≥ 0.90. Clusters correspond to the connected components of this network (single-linkage grouping). Using this method, 92.1% (n = 1027) of the 1115 plasmids were grouped into 48 distinct clusters named according to size, with the largest plasmid cluster named PC1 and the smallest, PC50 (Fig. 1C). For consistency in the analysis, plasmids that contained two CP genes (blaVIM-4/blaIMP-26 and blaOXA-181/blaNDM-1, n = 2) were included as duplicates to accurately reflect CP-gene specific analyses. Therefore, PC33 and PC47 are not listed as true plasmid clusters, and these four plasmids are categorized as unclustered (Table 1). PC1 comprised 389 closely-related blaKPC-2-positive plasmids carrying the IncU replicon and accounted for 34.9% of all plasmids and 81.3% of all blaKPC-2-positive plasmids. Although by replicon typing PC1 is classified as IncU based on the in silico identity of a partial replicon sequence, previous in vitro experiments have shown that the functional replicon of PC1 is trfA and the plasmid is classified as IncPe115. PC2 comprised IncN plasmids that were predominantly blaNDM-1-positive with the exception of one blaNDM-9-positive plasmid, and accounted for 284 (25.5%) of all plasmids. PC2 accounted for 67.2% of all blaNDM-1-positive plasmids. In comparison, only 37 (3.3%) plasmids were represented in the third-largest cluster, PC3 (Table 1). We applied the same plasmid clustering approach to a different, publicly-available dataset of circularized blaIMP-4 plasmids (n = 154) from an institutional collection of mostly clinical carbapenem-resistant isolates systematically collected from 2002 to 20207. This dataset included some environmental isolates but did not include patient surveillance isolates, and showed a similar pattern in which a subset of highly conserved plasmid clusters dominate the cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2).

PC1 was distributed across 10 species, predominantly K. pneumoniae (42.9%, n = 167) and E. coli (33.2%, n = 129). Among K. pneumoniae isolates carrying PC1, there were 60 assigned STs, most commonly ST231 (6.7%, n = 11). Among E. coli isolates carrying PC1, there were 57 assigned STs, the most common being ST131 (11.9%, n = 14). PC2 was also distributed across 10 species, predominantly E. coli (38.7%, n = 110) and K. pneumoniae (27.5%, n = 78). Among E. coli isolates carrying PC2, there were 31 known STs, with ST131 (43.2%, n = 45) being the most common. Among K. pneumoniae isolates carrying PC2, there were 28 known STs, the most common being ST34 (15.8%, n = 12) (Supplementary Table 6).

To contextualize the plasmids in our dataset in terms of known plasmid diversity, we performed BLAST on all 48 plasmid clusters against the PLSDB database. Thirty-five plasmid genotypes matched (weighted average identity >99%) a previously described plasmid outside of our dataset (Supplementary Table 7), and 13 were putative novel plasmids. We also compared our plasmid clustering approach with other approaches, such as using MOB-suite to assign MOB-suite clusters16 and COPLA to define plasmid taxonomic units17. Our clustering approach demonstrates good agreement with MOB-suite, which also utilizes an alignment-free method. All of our plasmid clusters are assigned to a single MOB-suite cluster (with the sole exception of PC11), but MOB-suite clusters could be further subdivided into multiple closely-related plasmid clusters, suggesting that our method is higher in resolution (Supplementary Fig. 4). COPLA was unable to classify 35.7% of our clustered plasmids into plasmid taxonomic units, suggesting previously unsampled diversity in our dataset (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Transmission dynamics of predominant carbapenemase-encoding plasmids

To investigate the relative impact of vertical versus horizontal transmission on the dissemination of carbapenemase-encoding plasmids in the study population, we analysed isolates carrying blaKPC-2-positive PC1 plasmids and blaNDM-1-positive PC2 plasmids, as designated by our k-mer based clustering method. A carbapenemase-encoding plasmid was considered vertically acquired by an isolate if the host met pairwise clonal linkage criteria with an earlier isolate. Briefly, a pair of isolates were determined to be clonally linked if they shared the same ST-cluster, same carbapenemase gene allele and had a pairwise single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) count (based on the recombination-filtered core gene alignments) below the BEAST-derived mutation rate threshold, assuming a Poisson distribution for the accumulation of mutations11. A carbapenemase-encoding plasmid was considered horizontally acquired by an isolate if the host was not clonally linked to another isolate.

Of the 389 isolates carrying a blaKPC-2-positive PC1 plasmid, 236 (60.7%) putatively acquired the plasmid via horizontal transmission, whereas 153 (39.3%) putatively vertically inherited the plasmid from a parent cell. Vertical transfer was unable to account for the spread of blaKPC-2-positive PC1 plasmids across the five institutions where it was detected. Of 60 clonal lineages, most were limited to a single hospital, and only five were found across two hospitals (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 8).

Each point represents the incidence of a A blaKPC-2-positive PC1 plasmid or B blaNDM-1-positive PC2 plasmid. The points are ordered along the x-axis based on the date of detection, with displacement along the y-axis for clarity. Plasmids that occurred in isolates that met pairwise clonal linkage criteria are visually connected by pink horizontal lines. Species and hospitals associated with the plasmids are listed. PC1 plasmids were detected across 10 species and five different hospitals, while PC2 plasmids were detected across 10 species and all six study sites. For clonal lineage, the following information is annotated in this format: “abbreviated species; ST number of isolates, number of hospitals where the clone was detected” (more details can be found in Supplementary Tables 8 and 9).

Of the 284 isolates carrying a blaNDM-1-positive PC2 plasmid, 168 (59.4%) putatively acquired the plasmid via horizontal transfer, whereas 115 (40.6%) putatively vertically inherited the plasmid from a parent cell. Similarly, vertical transfer was unable to account for the spread of blaNDM-1-positive PC2 plasmids across all six study sites. Of 38 clonal lineages, only seven spread beyond one hospital: six spanned two hospitals and one spanned three (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table 9).

Similar trends were observed for isolates carrying plasmids from the next two largest clusters, blaOXA-181-positive PC3 (n = 37) and blaOXA-48-positive PC4 (n = 31), as well as from PC7 (n = 25), the next-largest blaKPC-2-positive plasmid cluster after PC1, and PC5 (n = 29), the next-largest blaNDM-1-positive plasmid cluster after PC2, in which clonal lineage-dependent vertical transmission limited carbapenemase gene spread across fewer institutions compared to plasmid-mediated horizontal transmission of carbapenemase genes (Supplementary Fig. 6). Five E. coli ST162 isolates (from three unique patients and two hospitals) were found to co-carry blaKPC-2-positive PC1 and blaNDM-1-positive PC2 plasmids.

Our data suggest that plasmids are important drivers in the mobilization of carbapenemase genes between species and between geographic niches (different institutions), and also in the persistence of carbapenemase genes over time in the population. Based on the temporal trends of plasmid clusters that each accounted for >1% of all plasmids (n = 12), many plasmid genotypes are stably maintained in the population for years, although apart from PC1 and PC2, none of the other plasmids showed signs of potentially moving towards hyperendemicity within our period of study (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Predominant carbapenemase plasmids maintain a distinct backbone of core gene loci

PC1 and PC2 were considered evolutionarily successful plasmids due to their high prevalence, with each accounting for more than 25% of plasmids in the cohort (Table 1). The PC1 core genome of 97 genes that were present in 95% of PC1 plasmids was found to be highly conserved (> 90%) in PC7 and PC43 compared to other blaKPC-2-positive IncU plasmid genotypes (Fig. 3A). The PC2 core genome of 52 genes that were present in 95% of PC2 plasmids was found to be most highly conserved (> 90%) in PC20 and PC49 compared to other blaNDM-1-positive IncN genotypes (Fig. 3B). Gene cluster organisation of representative PC1 (Fig. 3C) and PC2 (Fig. 3D) plasmids, visualized by Clinker, emphasizes the structural conservation of a distinct backbone of core gene loci, and reveals divergence from the PC1 and PC2 genetic settings through insertion events.

A Comparison of the core genome of PC1, the predominant blaKPC-2-positive IncU plasmid type, with all other blaKPC-2-positive IncU plasmids. B Comparison of the core genome of PC2, the predominant blaNDM-1-positive IncN plasmid type, with all other blaNDM-1-positive IncN plasmids. Visualization of structural differences between representative sequences of C PC1 and other closely-related blaKPC-2-positive IncU plasmids, as marked by the red box in this figure (A), and D PC2 and other closely-related blaNDM-1-positive IncN plasmids, as marked by the red box in this figure (B). In the linear alignments generated by Clinker, similar colors indicate conserved regions; grey arrows represent inserted genes.

The blaKPC-2-associated PC1 genotype, a hybrid of pSA20021456.2-like plasmids (GenBank accession no. CP030221) and pKPCAPSS-like plasmids (GenBank accession no. KP008371), appears to be unique to Singapore to date, and was previously characterized as pKPC2_sg1 (GenBank accession no. MN542377)18. pKPC2_sg1 was demonstrated in vitro to impose low fitness costs, have high conjugation frequencies and high retention rates in multiple Enterobacterales species15. PC7 and PC43 also appear to be unique to our dataset (Supplementary Table 7).

In contrast, blaNDM-1-associated PC2 has been reported previously as pNDM-ECS01 (GenBank accession no. KJ413946) and has been widely linked to high-risk clones such as E. coli ST131 and K. pneumoniae ST11 and ST1519. PC20 and PC49 have also been previously identified outside of Singapore (Supplementary Table 7).

Expansion of the accessory genome limits prevalence of carbapenemase plasmids

To investigate if there were any specific genes that could be associated with the likelihood or failure to achieve hyperendemicity, we compared the full gene complement of PC1 (34.9% of all plasmids) with that of plasmids with high core genome similarity but significantly lower prevalence (Supplementary Fig. 3), such as PC7 (2.2% of all plasmids) and PC43 (0.2% of all plasmids) (Fig. 4A). Likewise, we compared the full gene complement of PC2 (25.5% of all plasmids) with that of PC20 (0.4% of all plasmids) and PC49 (0.2% of all plasmids) (Fig. 4B). It could be ruled out that the less prevalent plasmids were poorly represented in the cohort as a result of late emergence towards the end of the sampling time frame (Supplementary Fig. 8).

A Matrix depicting the gene complement of PC1, the predominant blaKPC-2-positive IncU plasmid type, and the closely similar plasmids PC7 and PC43. Plasmids are ordered along the y-axis according to the k-mer similarity dendrogram shown on the left. Genes are ordered along the x-axis, and those of interest are annotated. B Matrix depicting the gene complement of PC2, the predominant blaNDM-1-positive IncN plasmid type, and the closely similar plasmids PC20 and PC49. Representative closed plasmids are shown and annotated.

PC7 plasmids harbored additional genes not found in PC1 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Comparison of representative PC1 (71,855 bp) and PC7 (87,271 bp) plasmids show two distinct inserted genomic regions in PC7 (Fig. 4A). Notably, the 8020 bp region (Inserted Region 1) encoded genes belonging to the Mer operon20 involved in mercury detoxification and the 6574 bp region (Inserted Region 2) encoded genes belonging to the FrmRAB operon21, involved in formaldehyde detoxification (Supplementary Table 10). Similarly, plasmids in PC43 (97,516 bp) contained the arsR, copG, and srpC genes involved in heavy metal detoxification (Supplementary Table 11).

Likewise, PC20 and PC49 plasmids also contained accessory genes not present in PC2 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Comparison of representative PC2 (41,183 bp) and PC20 (50,744 bp) plasmids show two distinct inserted genomic regions in PC20 (Fig. 4B), although only one of the regions (8494 bp) encoded known genes—belonging to the Ars operon22 and involved in arsenic detoxification (Supplementary Table 12), as well as genes related to integration and excision. Comparison of representative PC2 and PC49 (59,567 bp) plasmids show a single inserted genomic region in PC49 (Supplementary Table 13).

Based on 85% coverage and identity, of isolates carrying PC1, the mercury detoxification region was found in the chromosome of 0.26% (n = 1) and in the carbapenemase-negative plasmid compartment of 0.51.% (n = 2). The formaldehyde detoxification region was found in the chromosomes of 12.3% (n = 48) and in the carbapenemase-negative plasmid compartment of 9.5% (n = 37) of PC1 isolates. Similarly, among isolates carrying PC2, the arsenic detoxification region was found in the chromosome of only 12.3% (n = 35) and in the carbapenemase-negative plasmid compartment of only 16.5% (n = 47), suggesting that these detoxification genes were not essential for the survival of bacteria harboring the predominant carbapenemase plasmids. The presence of heavy metal and organic contaminants in the hospital environment has been documented23. The detoxification genes found in patient isolates could have been acquired horizontally from environmental bacteria, where it may have conferred a survival advantage. Biocide and metal resistance genes are also known to co-occur with antibiotic resistance genes on the same plasmid24.

Evolution of plasmids within the same clonal transmission cluster and within the same patient

We next examined plasmid evolution along the same clonal lineage between patients and across multiple species within the same patient. blaKPC-2-positive plasmids were grouped into 10 plasmid clusters based on k-mer similarity (Table 1). A clonal transmission cluster comprised index isolates that met pairwise clonal linkage criteria with at least one earlier index isolate from another patient. An index isolate was defined as the first-detected isolate carrying a unique carbapenemase gene in a patient during the study period. More than one index isolate (carrying different carbapenemase genes) could be associated with a patient if they shared the same date of culture. Only index isolates were considered for construction of clonal transmission clusters to ensure that clusters reflect between-patient transmission events. PC1 plasmids were associated with 14 clonal transmission clusters across four species, while the remaining blaKPC-2-positive plasmid clusters were collectively associated with only six clonal transmission clusters across two species. blaNDM-1-positive plasmids were grouped into 20 plasmid clusters (Table 1). PC2 plasmids were associated with 19 clonal transmission clusters across six species, compared with 10 clonal transmission clusters across three species for all other blaNDM-1-positive plasmid clusters. We found evidence for carriage of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 genes on multiple plasmid genotypes within the same clonal lineage, reflecting dynamic alterations to plasmid structures on which carbapenemase genes are localized, or the transfer of carbapenemase genes to non-carbapenemase plasmids. However, most of the clonal transmission clusters with more than three isolates arose from an isolate carrying either blaKPC-2 on a PC1 plasmid or blaNDM-1 on a PC2 plasmid, suggesting that PC1 and PC2 genotypes are well-adapted for stable propagation of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1, respectively, during inter-patient clonal spread (Fig. 5A, B). This is exemplified in the largest blaKPC-2 clonal transmission cluster (Clonal cluster 1) comprising 19 E. cloacae ST93 isolates, where putative recombination-driven changes to the blaKPC-2 plasmid resulting in its departure from the predominant PC1 genome were not preserved, and blaKPC-2 reverted to localization on a PC1 backbone in subsequent clones.

Plasmid profiles of A blaKPC-2-positive and B blaNDM-1-positive clonal transmission clusters. Clonal transmission clusters comprising three or more isolates are shown. Each column represents a clonal transmission cluster comprising index isolates that met pairwise clonal linkage criteria with at least one earlier index isolate from another patient. An index isolate was defined as the first-detected isolate carrying a unique carbapenemase gene in a patient during the study period. For each cluster, carbapenemase plasmid genes are arranged along the y-axis and isolates are arranged along the x-axis according to date of culture, from earliest to latest (left to right). Heat map indicates gene presence (colored) or absence (greyed). The number of isolates per clonal transmission cluster as well as number of days between the earliest and latest isolate detected are shown.

Twenty-two individuals (of 705 patients) were determined to be the source of five or more isolates. In 20 of 22 patients, the same plasmid was found in two or more different species; in five of 22 patients, the same plasmid was found in three or more different species. The median number of species in which PC1 and PC2 were found were 2 (IQR, 2−2 and IQR, 1−2, respectively). For remaining PCs, the median number of host species was 1 (IQR 1−1). Our data suggests that in the context of a singular human host, blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 are more stably maintained over time and across multiple species (and STs) in PC1 and PC2 plasmids, respectively, compared to other genetic settings (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Current surveillance systems for bacterial pathogens are limited to tracking clonally evolving lineages, which is severely inadequate in the case of CPE, as carbapenemase genes are primarily localised on extrachromosomal plasmids that can spread horizontally between strains and species. A few longitudinal studies have attempted de novo reconstruction of selected plasmid sequences7,25,26. To our knowledge, this work is based on the largest collection of complete CPE genomes, including 1115 fully circularized carbapenemase-encoding plasmids. Our analyses revealed remarkable plasmid diversity of at least 48 distinct mobilizable carbapenemase plasmid genotypes, and depicted the rise of predominant plasmid clusters in the context of co-circulation of four of the five major carbapenemase types across a nationwide network of hospitals. blaKPC-2-associated PC1 and blaNDM-1-associated PC2 accounted for approximately 60% of all CPE plasmids detected in the span of five years. These predominant plasmids drove widespread inter-species dissemination across multiple institutions and long-term persistence of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 in the population.

Prior results from a European survey spanning six months and limited to K. pneumoniae suggested that blaKPC-2 mobilized into multiple plasmids while maintaining predominantly in ST258/512, whereas blaNDM-1 leveraged on frequent transposition to access varied plasmids across different STs for spread9. Our data similarly acknowledges the mosaicism of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 plasmids, but suggests that over a longer time scale, the spread of blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1 were driven by dominant plasmids that mobilized as a discrete unit among diverse strains and lineages.

Our data suggests that there is a dynamic tension between plasticity and stability in the evolution of carbapenemase plasmids over time. These resistance plasmids readily acquired a variety of genes, but their diversity was constrained by selection pressures imposed by their bacterial and possibly human hosts for certain genetic settings over others. It is known that the absence of selection for plasmid-encoded traits, most plasmids reduce overall bacterial fitness27. We propose that a crucial factor enabling evolutionarily successful carbapenemase plasmid genotypes such as PC1 and PC2 to achieve hyperendemicity in the population is the maintenance of conserved genomes, preserving as far as possible only core genes, thus minimizing fitness costs to the host28. The broad host range of PC1 and PC2, including evidence of the association of PC1 with hypervirulent strains of K. pneumoniae18, which could fuel community outbreaks is deeply concerning.

We acknowledge that there may be limits to the generalisability of our findings to other ecological settings. However, we believe that at the very least this work provides insight to carbapenemase gene spread in Southeast Asia, given Singapore’s status as a regional travel hub and our extensive sampling methodology covering 80% of the national inpatient load. There are also inherent limitations in our clustering strategy based on k-mer similarity. It may not reliably distinguish phylogenetically related plasmids, as recombination can lead to convergence or divergence in gene content that causes unrelated plasmids to cluster together or closely-related ones to appear distinct. The method also does not account for gene order or synteny, which can offer important clues about shared plasmid backbones. Additionally, the similarity threshold used for clustering, while empirically selected, is ultimately arbitrary. It serves to provide a useful descriptive landscape of carbapenemase plasmid diversity but may still imply relationships that do not reflect true evolutionary history. We did not conduct in vitro conjugation assays for plasmids other than PC1, which we had previously demonstrated to impose low fitness costs, have high conjugation frequencies, and high retention rates in multiple Enterobacterales species15. More work needs to be done to determine the molecular mechanisms underlying the fitness effects of carbapenemase-encoding plasmids, and the possibility of using a comparative genomics approach to predict epidemic-potential plasmids.

Our work highlights an urgent need to expand surveillance efforts to adequately recover plasmid structures in order to comprehensively understand carbapenemase gene dissemination, and provides a framework for identification of genes associated with plasmid persistence.

Methods

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics institutional review boards of National Health Group Singapore (DSRB reference: 2014/00617) which did not require that patients provide written informed consent, primarily on the grounds that this study posed no more than minimal risk to participants as it did not involve interaction with patients, and robust measures were in place to protect patients’ confidentiality during analysis. This retrospective cohort study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines for reporting observational studies29.

Study population

From September 6, 2010 to April 28, 2015, all CRE isolates from inpatient clinical and surveillance cultures were collected across participating sites11. Surveillance cultures to detect gut colonization were from rectal swab or stool samples taken from asymptomatic carriers identified via screening of high-risk patients and epidemiologically linked contacts. CRE isolates suspected of carrying carbapenemase genes were submitted to the National Public Health Laboratory (NPHL) for further phenotypic characterization and polymerase chain reaction-based assays. CPE isolates were obtained from NPHL for whole genome sequencing and analysis.

Whole genome sequencing and hybrid assembly

Sequencing libraries for each isolate were prepared using the Illumina Nextera XT kit and sequenced on the MiSeq platform10. Cutadapt30 (v1.14) was used for adapter and quality trimming. A minimum quality score of 20 was applied and reads shorter than 20 bp were filtered. Libraries for long-read sequencing were prepared for the same isolates using the ONT Rapid Barcoding Kit (RBK004) and sequenced on R9.4.1 flowcells on a GridION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Basecalling was performed using Guppy version 3.2.6 (https://nanoporetech.com/software/other/guppy), which was integrated with the MinKNOW software, and demultiplexing was performed using qcat (https://github.com/nanoporetech/qcat). The average Nanopore data throughput was 1.2 Gb per isolate (range: 0.002—5.4 Gb). Hybrid assemblies were generated from the long-read and short-read sequencing data using Unicycler31 (v0.48) with default parameters. Hybrid assemblies that contained closed carbapenemase gene contigs less than 500 kb (assumed to be non-chromosomal) that contained at least one replicon were included in the final analysis.

Bacterial species and ST assignments and plasmid identification

Bacterial species and ST assigments were based on previously published work11. Isolates for which ST assignment was unsuccessful from short-read assemblies were re-typed from hybrid assemblies using MLST (v2.23)32. Carbapenemase-encoding plasmids were defined as fully-circularized contigs that (i) contained at least one carbapenemase gene with 100% amino acid coverage and identity as determined NCBI AMRFinderPlus33, (ii) were less than or equal to 500 kb in length, (iii) contained a replicon sequence as determined by MOB-suite16 (v3.1.4), and (iv) did not contain any MLST gene allele.

Plasmid clustering

Carbapenemase-encoding plasmids were clustered based on pairwise k-mer (21 bp) similarity. Plasmids were converted into k-mer lists using the GenomeTester434 toolkit and the Jaccard similarity index was calculated between plasmid pairs. To assign plasmids to clusters, we built an undirected similarity network in R with igraph (v1.6.0): each plasmid was represented as a node and an edge was drawn between any two plasmids whose 21-mer Jaccard similarity was ≥ 0.90. Clusters correspond to the connected components of this network (single-linkage grouping). Visualization of clusters was performed using the ComplexHeatmap35 R package.

Representative plasmids were randomly selected from a subset of PC1 (n = 29, 7.5%) plasmids with identical circularized genomic lengths of 71,855 bp. Representative plasmids were randomly selected for PC7 and PC43. Intra-plasmid cluster pairwise k-mer similarity was 81.8% to 99.8% for PC1, 82.0% to 99.5% for PC7, and 98.9% for PC43. The representative PC2 plasmid was randomly selected from a subset of PC2 (n = 47, 16.5%) plasmids with the predominant circularized genomic length of 41,183 bp. PC20 and PC49 were very small clusters and representative plasmids were one of four (49,990 bp to 50,744 bp) and two (59,529 bp and 59,467 bp) plasmids per cluster, respectively. The intra-plasmid cluster pairwise k-mer similarity was 83.3% to 100% for PC2, 97.0% to 99.8% for PC20 and was 94.7% for PC49.

Plasmid gene annotation and analysis

Plasmid gene annotation was performed using Prokka36 (v1.14.6), supplemented by reference plasmid sequences obtained from NCBI following BLAST searches of representative circularized plasmids, and pan-genomes and core genomes were reconstructed using Panaroo37 (v1.5.0). k-mer similarity trees were constructed and visualized using the R package ggtree38 (v3.3.0) from the complementary fraction (1-distance) of k-mer distances. Plasmid persistence and gene profile plots were generated using the ggplot239 package (v3.3.5). Antibiotic resistance genes were identified using NCBI AMRFinderPlus33 (v3.10.21). Virulence genes were determined using ABRicate40 (v1.0.0) based on the VFDB database41. Further annotation of hypothetical proteins was performed with Bakta42 (v1.11.0) and/or NCBI Blastx (v2.9.0-2). Identification of Mer, Ars, and Frm operons in chromosomal and carbapenemase-negative plasmid compartments was performed with Blastn (v2.9.0-2) using representative sequences from PC7, PC43, and PC20 containing all the respective operon genes, and thresholds of 85% for identity and coverage. To differentiate between plasmid and chromosomal sequences, we utilized PlasClass43 (v0.1.1) and applied a probability threshold of 0.5 to classify a sequence as a plasmid. Carbapenemase-negative plasmid compartments were defined as plasmids with no carbapenemase genes identified by NCBI AMRFinderPlus33.

Determination of mutation rate of bacterial species and SNP threshold

Using previously published methods11, BEAST-derived mutation rates (substitutions/genome/year) for K. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. cloacae, and C. freundii were determined to be 1.01, 0.33, 1.06, and 2.72, respectively. These values were used as the SNP thresholds for defining clonal linkage among the above named species as well as other bacterial species with a limited number of isolates: the SNP threshold for K. pneumoniae was used for K. oxytoca, M. morganii, and P. mirabilis, SNP threshold for E. cloacae was used for E. aerogenes, and SNP threshold for C. freundii was used for C. amalonaticus, C. koseri, and C. rodentium/C. farmeri.

Role of the funding source

The sponsor of the study had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

A detailed description of the tools used to analyse the data are available in the manuscript or in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The Illumina short-read sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under accession codes PRJNA757551 and PRJNA765801. The Oxford Nanopore Technologies long-read sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under accession codes PRJNA801415 and PRJNA801416. The hybrid assembly data generated in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession codes PRJNA1171009, PRJNA1171156, PRJNA1171157, and PRJNA1171553. The sample-specific hybrid assembly accession codes are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Three samples were not uploaded because they did not meet the GenBank assembly size criteria.

References

Budhram, D. R., Mac, S., Bielecki, J. M., Patel, S. N. & Sander, B. Health outcomes attributable to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 41, 37–43 (2020).

Tacconelli, E. et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 318–327 (2018).

Lutgring, J. D. & Limbago, B. M. The problem of carbapenemase-producing-carbapenem-resistant-enterobacteriaceae detection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 529–534 (2016).

Barry, K. E. Don’t overlook the little guy_ An evaluation of the frequency of small plasmids co-conjugating with larger carbapenemase gene containing plasmids. Plasmid 103, 1–8 (2019).

Sheppard, A. E. et al. Nested Russian doll-like genetic mobility drives rapid dissemination of the carbapenem resistance gene bla KPC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 3767–3778 (2016).

Rozwandowicz, M. et al. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1121–1137 (2018).

Macesic, N. et al. Genomic dissection of endemic carbapenem resistance reveals metallo-beta-lactamase dissemination through clonal, plasmid and integron transfer. Nat. Commun. 14, 4764 (2023).

León-Sampedro, R. et al. Pervasive transmission of a carbapenem resistance plasmid in the gut microbiota of hospitalized patients. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 606–616 (2021).

David, S. et al. Integrated chromosomal and plasmid sequence analyses reveal diverse modes of carbapenemase gene spread among Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 25043–25054 (2020).

Marimuthu, K. et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae among adult inpatients in Singapore. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64, S68–S75 (2017).

Marimuthu, K. et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals hidden transmission of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales. Nat. Commun. 13, 3052 (2022).

David, S. et al. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1919–1929 (2019).

Nordmann, P., Dortet, L. & Poirel, L. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm!. Trends Mol. Med. 18, 263–272 (2012).

Ministry of Health, Singapore. Admissions and Outpatient Attendances. https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/admissions-and-outpatient-attendances (2018).

Yong, M. et al. Dominant carbapenemase-encoding plasmids in clinical enterobacterales isolates and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 28, 1578–1588 (2022).

Robertson, J. & Nash, J. H. E. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom. 4, e000206 (2018).

Redondo-Salvo, S. et al. COPLA, a taxonomic classifier of plasmids. BMC Bioinforma. 22, 390 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Acquisition of plasmid with carbapenem-resistance gene blaKPC2 in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae, Singapore. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 11 (2020).

Netikul, T. et al. Characterization of an IncN2-type blaNDM-1-carrying plasmid in Escherichia coli ST131 and Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 and ST15 isolates in Thailand. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 3161–3163 (2014).

Christakis, C. A., Barkay, T. & Boyd, E. S. Expanded diversity and phylogeny of mer genes broadens mercury resistance paradigms and reveals an origin for MerA among thermophilic archaea. Front. Microbiol. 12, 682605 (2021).

Denby, K. J. et al. The mechanism of a formaldehyde-sensing transcriptional regulator. Sci. Rep. 6, 38879 (2016).

Carlin, A., Shi, W., Dey, S. & Rosen, B. P. The ars operon of Escherichia coli confers arsenical and antimonial resistance. J. Bacteriol. 177, 981–986 (1995).

Ajala, O. J., Tijani, J. O., Salau, R. B., Abdulkareem, A. S. & Aremu, O. S. A review of emerging micro-pollutants in hospital wastewater: environmental fate and remediation options. Results Eng. 16, 100671 (2022).

Pal, C., Bengtsson-Palme, J., Kristiansson, E. & Larsson, D. G. J. Co-occurrence of resistance genes to antibiotics, biocides and metals reveals novel insights into their co-selection potential. BMC Genomics 16, 964 (2015).

Stoesser, N. et al. Genomic epidemiology of complex, multispecies, plasmid-borne blaKPC carbapenemase in enterobacterales in the United Kingdom from 2009 to 2014. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, 18 (2020).

Roberts, L. et al. Genomic analysis of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae in Queensland reveals widespread transmission of bla IMP-4 on an IncHI2 plasmid. Microb. Genom. 6, e00032 (2020).

San Millan, A. Evolution of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in the clinical context. Trends Microbiol. 26, 978–985 (2018).

Rodríguez-Beltrán, J., DelaFuente, J., León-Sampedro, R., MacLean, R. C. & San Millán, Á. Beyond horizontal gene transfer: the role of plasmids in bacterial evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-00497-1 (2021).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 344–349 (2008).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005595 (2017).

Seemann, T. mlst. GitHub. https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (2022).

Feldgarden, M. et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog facilitate examination of the genomic links among antimicrobial resistance, stress response, and virulence. Sci. Rep. 11, 12728 (2021).

Kaplinski, L., Lepamets, M. & Remm, M. GenomeTester4: a toolkit for performing basic set operations - union, intersection and complement on k-mer lists. GigaScience 4, s13742–015-0097-y (2015).

Gu, Z. Complex heatmap visualization. iMeta 1, e43 (2022).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Tonkin-Hill, G. et al. Producing polished prokaryotic pangenomes with the Panaroo pipeline. Genome Biol. 21, 180 (2020).

Yu, G., Smith, D. K., Zhu, H., Guan, Y. & Lam, T. T.-Y. ggtree: an R package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 28–36 (2017).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

Seemann, T. ABRicate. GitHub. https://github.com/tseemann/abricate (2020).

Chen, L., Zheng, D., Liu, B., Yang, J. & Jin, Q. VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis-10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D694–697 (2016).

Schwengers, O. et al. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb. Genom. 7, 000685 (2021).

Pellow, D., Mizrahi, I. & Shamir, R. PlasClass improves plasmid sequence classification. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1007781 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Singapore Infectious Diseases Initiative, Infection Prevention and Control units of contributing hospitals, Singapore Clinical Research Network (SCRN), and the Singapore Clinical Research Institute (SCRI). This research was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (NMRC) under its NMRC Clinician Scientist Award—Senior Investigator (MOH-001763; O.T.N.), NMRC Clinician Scientist Individual Research Grant (MOH-001706; K.M.), NMRC Collaborative Grant: Collaborative Solutions Targeting Antimicrobial Resistance Threats in Health Systems (CoSTAR-HS; CG21APR2005; O.T.N.), and NMRC Open Fund—Large Collaborative Grant: AntiMicrobial resistance Research & Intervention Alliance Singapore (AMRITAS; MOH-001326-01; O.T.N.). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Singapore Ministry of Health and/or the National Medical Research Council. D.W.E. is a Robertson Foundation Fellow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

O.T.N. conceived of and led the study. K.M., I.V., B.P.Z.C., R.K.C.F., S.K.P., S.T.O., N.S., K.C.T., T.H.K., P.P.D., T.Y.T., D.C., R.M.D., N.W.S.T., M.A., R.T.P.L., and J.T. were involved in epidemiological and microbiological data collection from the participating institutions. O.T.N., V.K., R.C., P.S.R.S., N.M.T., and Z.Q.L. were involved in data analysis and data interpretation. V.K. wrote the manuscript in consultation with O.T.N., L.Y.H., Y.-H.G., W.M., and D.W.E. The corresponding author attests that the authors had access to all the study data, take responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis, and had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Michael Brouwer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koh, V., Cabrera, R., Sridatta, P.S.R. et al. Plasmid dynamics driving carbapenemase gene dissemination in healthcare environments: a nationwide analysis of closed Enterobacterales genomes. Nat Commun 16, 9522 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64515-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64515-7