Abstract

Neuropathic pain (NP) is a debilitating condition driven by chronic neuroinflammation, where abnormal communication between microglia and astrocytes amplifies pain signaling. Current therapies offer limited benefit and primarily address symptoms rather than underlying mechanisms. Here, we show that transferrin- and phosphatidylserine-modified liposomes carrying a TDP-43 aggregation inhibitor (TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1) effectively cross the blood–brain barrier, target glial cells, and modulate their activation states. In vitro, the formulation improved cell viability and promoted anti-inflammatory phenotypes. In vivo, studies conducted in male C57BL/6 J mice demonstrated significant alleviation of pain behaviors, reduced inflammatory cytokine expression, and suppression of the cGAS–STING pathway. These findings indicate that targeting TDP-43 aggregation with a nanocarrier system can reprogram glial interactions to relieve neuropathic pain. This strategy highlights a promising approach for developing targeted, disease-modifying therapies that act on key drivers of neuroinflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NP) is a chronic pain condition caused by damage or dysfunction within the nervous system, commonly associated with various diseases and medical conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and post-stroke pain1,2,3. Epidemiological studies suggest that NP affects approximately 6.9%–10% of the global population, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life and mental health4,5. Characterized by hypersensitivity to pain, abnormal pain perception, and spontaneous pain, the pathophysiology of NP is complex, involving multiple cell types and molecular pathways6,7. The interaction between microglia and astrocytes plays a crucial role in NP, where these cells activate post-nerve injury and exacerbate pain abnormalities by releasing inflammatory mediators8. Understanding these mechanisms is critical for developing therapeutic approaches1,9,10.

Despite various existing treatments for NP, including antidepressants, antiepileptic drugs, and local anesthetics, these often provide limited relief and are associated with side effects such as drowsiness, dry mouth, and dependency11,12,13. Moreover, these treatments primarily address symptoms rather than underlying causes and often yield unstable long-term results14,15. Recent research has shifted focus towards the cellular and molecular mechanisms, particularly intercellular communication and interactions16. For instance, the activation states of astrocytes and microglia and the inflammatory factors they release have emerged as therapeutic targets in the development and progression of NP17,18.

TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) is a nuclear RNA/DNA-binding protein that plays a critical role in RNA splicing and transport19. Under pathological conditions, TDP-43 can mislocalize to the cytoplasm and form aggregates, leading to neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction. Studies have shown that TDP-43 aggregation is not only associated with neurodegenerative diseases but also contributes to neuroinflammatory processes by activating microglia and astrocytes20,21,22. Therefore, TDP-43 serves as a key upstream regulator of neuroinflammation and represents an important therapeutic target for NP.

Liposomal drug delivery systems have been extensively utilized for treating various diseases, including NP, due to their excellent biocompatibility, adjustable drug release properties, and efficient cellular delivery23. These nanoparticles can traverse the blood-brain barrier (BBB), precisely targeting cells and enhancing therapeutic outcomes while minimizing systemic side effects24. The TDP-43 aggregation inhibitor, a potential neuroprotective agent, prevents protein aggregation and cell death and has shown promise in several neurodegenerative diseases21,25. Delivering this inhibitor via liposomes offers a intervention for NP’s inflammatory states and cellular damage mechanisms26,27.

This study aims to investigate the therapeutic potential of targeting TDP-43 aggregation in NP. By delivering a TDP-43 aggregation inhibitor using phosphatidylserine (PS)- and transferrin (TF)-modified liposomes, we evaluated their regulatory effects on microglia and astrocytes, which are key mediators of neuroinflammation. The study focuses on elucidating how inhibition of TDP-43 aggregation can suppress glial activation, thereby alleviating neuroinflammatory responses and improving NP symptoms. These findings not only provide insights into NP pathogenesis but also support the development of a targeted therapeutic strategy for patients with treatment-resistant NP.

Results

Microglia-astrocytes crosstalk mediating the onset of NP

Astrocytes and microglia are non-neuronal cells that maintain central nervous system homeostasis by regulating neuronal transmission and synaptic pruning. Given astrocytes and microglia’s critical role in sustaining neuronal function, understanding their heterogeneity and identifying the genes and mechanisms that regulate their response to NP is crucial28. This study explores changes in astrocytes and microglia within spinal cord tissues of adult C57BL/6J mice 7 and 14 days after CCI of the sciatic nerve, using single-cell sequencing analysis based on GEO dataset GSE20876629, which also includes contralateral normal controls.

We utilized the Seurat package for data integration and evaluated the gene count (nFeature_RNA), mRNA molecule count (nCount_RNA), and mitochondrial gene percentage (percent.mt) in the scRNA-seq data. We set quality control thresholds at nFeature_RNA > 200, nCount_RNA < 50000, and percent.mt <20 to eliminate low-quality cells (Fig. S1A). Highly variable genes were identified through variance analysis, selecting the top 2000 for downstream analysis (Fig. S1B). Dimensionality reduction was performed using PCA, where the ElbowPlot was employed to determine the optimal number of PCs. The first 17 PCs were then used for non-linear dimension reduction using t-SNE (Fig. S1C).

We annotated cell types in our samples using well-established cell lineage-specific marker genes and the online database CellMarker (Fig. S1D, E). We identified ten distinct cell categories (Fig. 1A): neurons, oligodendrocytes, microglia, astrocytes, endothelial cells, macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, fibroblasts, and pericytes (Per). The composition of different cell types within each sample is depicted in Fig. 1A. Additionally, we analyzed the distribution of cell subpopulations in the CCI mouse model. The results indicated a significant increase in the proportion of microglia and astrocytes in the CCI14D group compared to the CCI7D group (Fig. S1F). We also inferred communication between microglia and astrocytes by calculating the likelihood of interactions between all ligand-receptor pairs (L-R pairs) associated with each signaling pathway. There was robust communication between microglia and astrocytes in the CCI model (Fig. 1B).

A t-SNE clustering map of annotated cell types after batch effect removal, extracted from single cells in CCI model mice (7D and 14D) and their contralateral standard dorsal spinal tissue samples; B Intercellular ligand–receptor interaction networks were predicted using the CellPhoneDB database. Node size represents gene expression intensity, and edge thickness indicates interaction frequency. The figure illustrates interactions between microglia and astrocytes; C Volcano plot of DEGs in various subgroups. Yellow dots represent downregulated genes, and purple dots indicate upregulated genes; D Heatmap of GO-BP enrichment analysis for each subgroup. The left line chart represents gene expression abundance, the middle heatmap shows gene cluster expression, and the right side displays the GO analysis BP enrichment results; E t-SNE clustering map for microglial subpopulations; F Distribution of the anti-inflammatory polarization-related gene Tgfb1 in microglia subgroups; G Clustering distribution of microglia subgroups on the developmental tree, with different colors representing different cell subgroups; H t-SNE clustering map for astrocytes subgroups; I Distribution of the neuroprotective astrocyte-related gene S100A10 in astrocytes subgroups; J Clustering distribution of astrocyte subgroups on the developmental tree, with different colors representing different cell subgroups. RNA-seq data in this figure derive from GEO: GSE20876629.

Further enrichment analysis of DEGs across these ten cell types revealed involvement in pathways such as cell junction disassembly, microglia cell activation, and leukocyte activation in the inflammatory response, and other related signaling pathways (Fig. 1C, D).

We further explored the heterogeneity of microglia and astrocytes. Our results demonstrated that microglia could be reclassified into two distinct subclusters (microglia1 and microglia2) and astrocytes into three distinct subclusters (astrocyte1, astrocyte2, and astrocyte3) (Fig. 1E/H). Notably, the microglia2 subcluster exhibited higher expression of genes associated with anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive microglial phenotypes, such as Tgfb1, while the astrocyte3 subcluster showed elevated expression of genes linked to neuroprotective astrocytic states, such as S100A10 (Fig. 1F/I).

Using Monocle, we constructed developmental trajectories for each cell type. We observed distinct trajectories for different types of cells; the microglia subpopulation microglia1 transitioned towards microglia2, whereas the astrocyte subpopulation started from astrocyte1 and developed towards astrocyte3 and astrocyte2 (Figs. 1G/J and S1G, H). In summary, these results indicate that the crosstalk between microglia and astrocyte mediates the occurrence of NP.

Astrocyte and microglia targeting with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1

Research has demonstrated that TDP-43 plays a significant role in neuroinflammatory diseases through pathways involving microglia and astrocyte22,30. Although TDP-43-in are widely used in various neurologically related diseases31,32, their application in NP remains underexplored. To investigate the role of TDP-43-in in NP, we developed TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 using the thin-film hydration method, with TF as a targeting molecule to facilitate drug transport across the BBB. PS aids in targeting the liposomes to activate astrocyte and microglia. TF targets the TF receptors (TfR) that are overexpressed on the endothelial cells of the BBB, allowing passage through the BBB33,34. Nanoparticles enhance the delivery of therapeutic agents across the BBB, effectively transporting the drug to the brain35. However, there are few studies on the activation of microglia and astrocyte in chronic NP36,37.

The average particle sizes of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 were 101.1 ± 4.2 nm and 105.4 ± 5.7 nm, respectively, exhibiting narrow size distributions (Fig. S2A). The zeta potential distributions for TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 are shown in Fig. S2B. TEM analysis revealed that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 possess hollow structures and uniform morphology (Fig. S2C). The particle size and EE of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 were observed at 4 °C over 28 days. The particle size of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 varied from 100 nm to 150 nm, indicating regular and minimal changes. The encapsulation efficiencies for TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 were 44.27 ± 2.79% and 39.13 ± 2.59%, respectively (Figs. 2A and S3A), demonstrating good stability.

A Particle size stability of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 was monitored over 30 days, showing consistent morphology (mean ± SD, n = 3); B Comparison of cumulative TDP-43 release from TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 in PBS (mean ± SD, n = 3); C Fluorescence microscopy images (scale bar = 15 μm) showed effective uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 by LPS-induced primary astrocytes (mean ± SD, n = 3); D Fluorescence microscopy images (scale bar = 15 μm) demonstrated DiR-labeled nanoparticle uptake in LPS-induced primary microglia (mean ± SD, n = 3); E Flow cytometry analysis of LPS-induced astrocytes revealed time-dependent uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 at 30 min and 4 h; F Flow cytometry analysis of LPS-induced microglia showed significant uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 at 30 min and 4 h. Data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent sample t-tests. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. * indicates p < 0.05 compared to the two groups. Cell experiments were repeated three times.

As shown in Fig. 2B, in PBS (pH 5.0), more than 80% of TDP-43 was released from TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 within 12 h. In contrast, under PBS (pH 7.4) conditions, only about 20% of TDP-43 was released within 12 h. After 48 h, approximately 90% of the encapsulated TDP-43 was released from TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 in PBS (pH 5.0), whereas only about 30% was released under PBS (pH 7.4) conditions.

We further investigated the hemolytic effect of different concentrations of TDP-43 (3.125–100 μM) on mouse erythrocytes. As shown in Fig. S3B, the hemolysis rate gradually increased from 0.25% at the lowest concentration of 3.125 μM to 4.95% at 100 μM TDP-43. Biomaterials are generally classified based on their hemolysis index into non-hemolytic (≤ 2%), slightly hemolytic (2–5%), and hemolytic (> 5%). According to these standards, the formulations used in this study are suitable for intravenous administration.

The safety of liposomes in astrocytes and microglia was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. Astrocytes and microglia were incubated with TDP-43-IN-1 or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 containing varying concentrations of TDP-43 (0–200 μg/mL) for 48 h, followed by the CCK-8 assay. Figure S3C shows no significant differences in cell viability between cells treated with TDP-43-IN-1 and those treated with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, indicating that both formulations are non-toxic to astrocytes and microglia.

We further characterized the yield and purity of astrocytes and microglia using anti-GFAP and anti-CD68 antibodies (Fig. S4A). Subsequently, we investigated the uptake mechanism of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 by astrocytes and microglia. As shown in Fig. S4B, the uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 by astrocyte pre-treated with 2-deoxyglucose was downregulated, indicating that the uptake process is energy-dependent. Similarly, pre-treatment of astrocyte with PS resulted in reduced uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, suggesting that PSRs may mediate the cellular uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1.

We used fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry to analyze the in vitro uptake of liposomes by astrocytes and microglia. Additionally, we examined the uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in LPS-induced astrocytes and microglia. As depicted in Fig. 2C–F, cells’ uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 was time-dependent. Compared to TDP-43-IN-1, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showed significantly higher accumulation in astrocytes and microglia. Conversely, the accumulation of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 + TF in astrocytes and microglia was significantly lower compared to TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 alone.

Furthermore, we used laser confocal microscopy to observe the uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in normal astrocytes and microglia. We found that normal astrocytes and microglia exhibited lower uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. S4C). These data suggest that TF can mediate the cellular uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1.

In vitro protective effects of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 on LPS-induced cells

We investigated whether TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 protect cells induced by LPS. Primary astrocytes and microglia were divided into five groups: Control, LPS, LPS + TDP-43, LPS + TDP-43-IN-1, and LPS + TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1. Except for the Control group, all other groups were induced with LPS for 2 h. Following this, cells were incubated with different liposomes for 72 h, and cell viability was assessed.

As shown in Fig. 3A, compared to the Control group, primary astrocytes and microglia viability significantly decreased in the LPS group. However, compared to the LPS group, the viability of cells treated with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 significantly increased, with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showing the most pronounced protective effect.

A TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 treatment enhanced the viability of LPS-induced primary astrocytes and microglia; B Western blot analysis showed that LPS stimulation significantly downregulated PSR protein expression in both astrocytes and microglia; C Western blot analysis showed that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 increased the expression of C3 and S100A10 in LPS-induced astrocytes; D Western blot analysis showed that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 increased CD86 and CD206 protein expression in LPS-induced microglia; E,G Immunofluorescence (scale bar = 25 μm) analysis of C3 and S100A10 expression in primary astrocytes; F,H Immunofluorescence (scale bar = 25 μm) analysis of CD86 and CD206 expression in microglia. Data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent sample t-tests. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. * indicates p < 0.05 between groups. Cell experiments were repeated three times.

PS-specific receptors (PSRs) are crucial in recognizing and engulfing apoptotic cells by activating astrocytes and microglia38. Western blot analysis of PSR expression revealed that LPS-induced microglia expresses lower levels of PSRs compared to astrocytes (Fig. 3B). Previous studies have shown that NP triggers the activation of functionally distinct astrocyte subtypes: neurotoxic astrocytes, which exert detrimental effects through the release of complement component C3, and neuroprotective astrocytes, which promote neuronal survival and tissue repair39. Similarly, previous studies have shown that microglial polarization includes pro-inflammatory (neurotoxic) and anti-inflammatory (neuroprotective) phenotypes40. Therefore, promoting a transition of astrocytes toward neuroprotective states and microglia toward anti-inflammatory phenotypes may represent an effective strategy for treating CCI.

We assessed the expression levels of C3 and S100A10 in injured primary astrocytes and CD86 and CD206 in injured microglia. The analysis showed that, compared to the Control group, the LPS group had significantly elevated expressions of C3 and CD86 proteins and significantly reduced expressions of S100A10 and CD206 proteins. However, treatment with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 reversed these changes in the expression of C3, S100A10, CD86, and CD206 in injured primary astrocytes and microglia (Fig. 3C–H), with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showing the most substantial effect. These results suggest that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 protect LPS-induced primary astrocytes and microglia.

TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 can cross the BBB and exhibit brain targeting

To investigate the in vivo application of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, we first analyzed their ability to penetrate the BBB using an in vitro BBB model (Fig. S5A). The fluorescence intensity of the lower chamber medium was measured using a spectrophotometer to calculate the transport efficiency. Results indicated that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 had significantly higher transport efficiency than TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. S5B).

As shown in Fig. S5C, there was no significant difference in the resistance values between the receiver Transwell chamber and the donor chamber within 12 h after administering TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, indicating that BBB integrity remained unaffected post-treatment. Additionally, we assessed the uptake efficiency of liposomes by astrocytes and microglia in the lower chamber. The results demonstrated that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 had significantly higher penetration efficiency through the BBB than TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. S5D, E).

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. S5F–I, significant differences in fluorescence intensity were observed in cells after incubation with different drugs for 1 h or 6 h. This indicates that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 can penetrate the BBB time-dependent, with a markedly higher transport efficiency than TDP-43-IN-1.

We further assessed the in vivo biodistribution of liposomes in mice using an IVIS imaging system. Mice were treated with DiR, TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR and then imaged at 1, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post-treatment. Notably, DiR-conjugated liposomes were detected in the brain and spleen of the mice (Fig. 4A, B). Additionally, the fluorescence intensity in the brains of mice treated with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR was significantly higher than that in mice treated with DiR or TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, indicating enhanced brain targeting by TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR (Fig. 4C).

A Fluorescence imaging demonstrated the biodistribution of liposomes in mouse brain tissue; B Biodistribution analysis across major organs (brain, heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys) showed predominant localization in the brain and spleen; C Statistical analysis of average fluorescence intensity and DiR in the mouse brain; D Quantification of TDP-43 levels in mouse brain tissue. E TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showed effective targeting to astrocytes (GFAP-positive) and microglia (CD86-positive) in the brains of CCI mice. Scale bar = 25 μm. F Nanoparticle uptake tracking via fluorescence imaging revealed robust cellular absorption, with arrows indicating perinuclear accumulation of nanoparticles. Data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent sample t-tests. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. * indicates p < 0.05 between groups: experimental animals, n = 6.

In the CCI mouse model, similar imaging was performed at 1, 6, and 24 h post-treatment with DiR, TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR. The accumulation of DiR-conjugated liposomes in the brains of CCI mice was evident (Fig. S6A). The fluorescence intensity in the brains of CCI mice treated with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR was significantly higher than that in mice treated with DiR or TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, further confirming enhanced brain targeting by TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR (Fig. S6B). Drug concentrations in mouse plasma and brain tissue were evaluated. At all time points, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showed significantly higher brain accumulation compared to TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. 4D). Cryosectioning of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of CCI model mice was performed. GFAP and CD86 immunolabeling was used to visualize astrocytes and microglia, respectively, confirming the brain-targeting efficiency of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. 4E). Fluorescent imaging tracked the uptake of nanoparticles. Confocal microscopy revealed clustered accumulation on the cell surface at 1 h and pronounced perinuclear localization at 24 h post-incubation (Fig. 4F).

We also performed cryosectioning and staining of brain tissues from CCI model mice, using GFAP and IBA1 to label astrocytes and microglia, respectively, to observe the brain-targeting capability of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. 4D). In the CCI model mice, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 effectively targeted injured astrocytes and microglia and modulated their polarization.

For in vivo safety evaluation, H&E staining showed no significant damage to the major organs of CCI mice treated with TDP-43, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. S6C). Additionally, serum levels of ALT, AST, BUN, and CREA remained within normal ranges at the end of the treatment (Fig. S6D), indicating that TDP-43, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 were safe at the experimental doses.

Prophylactic and therapeutic intrathecal administration of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 alleviates NP and neuroinflammation

To evaluate the preventative effects of TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 on CCI-induced NP and neuroinflammation, we conducted the experiment shown in Fig. 5A. Compared to the sham group, the PWT of CCI mice decreased significantly from days 1 to 14, and their TWL was markedly and cold sensitivity latency shortened during the same period. Pre-treatment with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 effectively reversed CCI-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia and cold allodynia.

A Schematic diagram of the prophylactic injection experimental procedure (Created in BioRender. J, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/j57dtiq); B Quantification of mechanical withdrawal thresholds and thermal latency following treatment, showing improvement in pain thresholds; C Assessment of cold allodynia latency, indicating effective reversal by liposomal treatment; D qRT-PCR detection of IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA expression in spinal cord tissues revealed reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression following treatment; E Schematic diagram of the therapeutic injection experimental procedure (Created in BioRender. J, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/51wvmie); F Quantification of mechanical and thermal pain thresholds post-therapy, demonstrating significant analgesic effects of liposomes; G Rotarod test results showing improvement in coordination and endurance after treatment; H qRT-PCR analysis showing reduced spinal IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA expression levels following liposomal therapy: * indicates comparison with the sham group, # indicates comparison with the CCI group, & indicates comparison with the CCI + TDP-43-in group, p < 0.05. For other panels: * indicates p < 0.05 between groups: experimental animals, n = 6. Data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent sample t-tests. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used.

Compared to the CCI group, mice treated with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showed increased PWTs and thermal withdrawal latencies and cold withdrawal latencies on days 1, 3, and 5 post-surgery, with the TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 group demonstrating the most pronounced effects (Fig. 5B, C). On day 3, RT-qPCR analysis was used to assess cytokine mRNA expression (IL-6 and TNF-α) in mouse spinal cord tissues. Pre-treatment with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 significantly reduced the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA in the ipsilateral spinal cord dorsal horn, with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showing the most substantial reduction (Fig. 5D). These results indicate that prophylactic intrathecal administration of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 can alleviate CCI-induced NP, inhibit microglia proliferation, and reduce neuroinflammation.

To evaluate the therapeutic effects of TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 on CCI-induced NP and neuroinflammation, we conducted the experiment outlined in Fig. 5E. Following CCI and injection of TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia tests were performed on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 14. Compared to the sham group, the CCI group exhibited a significant reduction in PWT from days 1 to 14. A single intrathecal injection of TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 on day 8 significantly alleviated mechanical allodynia on days 9 and 11 post-CCI. Moreover, the TWL was increased in the TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 groups on days 9 and 11 post-surgery, with effects lasting for 3 days. The TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 group showed the most pronounced improvements (Fig. 5F). The rotarod test was used to assess motor coordination, muscle strength, and fatigue tolerance. Compared to the sham group, CCI mice showed significantly prolonged reaction times on the rotarod from days 1 to 14. Pretreatment with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 effectively reversed CCI-induced motor impairment. On days 1, 3, and 5 post-surgery, all treatment groups exhibited significantly reduced reaction times compared to the CCI group, with the TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 group showing the most pronounced improvement (Fig. 5G). On day 11, RT-qPCR was used to measure cytokine mRNA expression (IL-6 and TNF-α) in mouse spinal cord tissues. A single intrathecal injection of TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 on day 8 reduced the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA in the ipsilateral spinal cord dorsal horn, with the TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 group demonstrating the most significant reduction (Fig. 5H). Further, ELISA analysis of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in the serum of mice treated with intrathecal TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showed that the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were significantly elevated in the CCI group compared to the control. However, these levels were significantly reduced in CCI mice treated with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. S7A). Immunofluorescence staining and Western blot analysis revealed that the expression of GFAP-positive astrocytes and CD86-positive microglia, as well as their protein levels, were significantly higher in the CCI group compared to the TDP-43-IN, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 groups. Notably, treatment with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 significantly reduced the number of astrocytes and microglia in CCI mice (Fig. S7B, C). These results indicate that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 can alleviate CCI-induced NP and ameliorate neuroinflammation.

TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 promote therapeutic polarization of astrocytes and microglia

We further evaluated whether TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 influence the polarization states of astrocytes and microglia in CCI mice. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that, compared to the sham group, the CCI group had a significant increase in the number of C3/GFAP-positive astrocytes (indicative of a neurotoxic phenotype) and a significant decrease in S100A10/GFAP-positive astrocytes (associated with a neuroprotective phenotype). Treatment with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in CCI mice significantly reduced the proportion of neurotoxic astrocytes and increased the number of neuroprotective astrocytes (Fig. 6A, B).

A, B Immunofluorescence images (scale bar = 25 μm) showed that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 reduced the expression of C3 and increased S100A10 in astrocytes, indicating a shift toward a neuroprotective phenotype; C, D Immunofluorescence images (scale bar = 25 μm) showing the expression levels of CD206, CD86, and IBA1; E Statistical analysis of C3 and S100A10 protein expression detected by Western blot, which was significantly decreased following treatment; F Statistical analysis of CD86 and CD206 protein expression detected by Western blot. Data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent sample t-tests. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. * indicates p < 0.05 between groups: experimental animals, n = 6.

Similarly, compared to the sham group, the CCI group showed a significant increase in CD86-positive microglia (pro-inflammatory) and a significant decrease in CD206-positive microglia (anti-inflammatory). Treatment with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in CCI mice significantly reduced pro-inflammatory microglia and increased anti-inflammatory microglia (Fig. 6C, D).

Further protein expression analysis showed that, compared to the sham group, the CCI group had significantly elevated levels of C3 and CD86 proteins and significantly reduced levels of S100A10 and CD206 proteins. Treatment with TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in CCI mice reversed these changes, with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 showing the most pronounced effects (Fig. 6E, F). These results indicate that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 effectively promotes a shift in astrocytes toward a neuroprotective phenotype and microglia toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype.

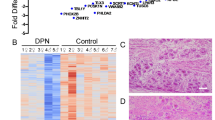

TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 inhibit cGAS-STING pathway activation

To elucidate the mechanism by which TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 treat NP, we conducted transcriptome sequencing on the sham, CCI, and CCI + TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 groups. As shown in Fig. S8A, B, the CCI group exhibited upregulation of 36 genes and downregulation of 53 genes compared to the sham group. In contrast, the TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 treatment group displayed 58 upregulated genes and 29 downregulated genes compared to the CCI group. The intersection of these gene sets revealed 12 common genes (Fig. S8C).

Hierarchical clustering analysis of these 12 genes showed that nine DEGs were highly expressed in the CCI group, but their expression levels significantly decreased in the CCI + TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 group (Fig. S8D). Furthermore, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 treatment significantly inhibited the expression of type I interferon (IFN) response-related genes, including STAT1 (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1), STAT2 (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 2), IRF7 (IFN Regulatory Factor 7), IRF9 (IFN Regulatory Factor 9), IFIH1 (IFN Induced with Helicase C Domain 1), and PSMB9 (Proteasome 20S Subunit Beta 9) (Fig. S8E). Previous studies have shown that the type I IFN response is regulated by the cGAS-STING pathway, which plays a crucial role in promoting inflammation41.

To further investigate whether TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 affect the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway, we analyzed the colocalization of STING and cGAS with GFAP and IBA1. As shown in Fig. 7A, cGAS/GFAP and STING/GFAP expression significantly increased in the CCI group compared to the sham group. Treatment with TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 significantly inhibited the expression of cGAS/GFAP and STING/GFAP in the CCI group. We also found that cGAS and STING were expressed in microglia (Fig. 7B). The CCI group showed upregulated expression of cGAS/CD86 and STING/CD86 compared to the sham group, while TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 treatment markedly suppressed the expression of cGAS/CD86 and STING/CD86 in CCI mice.

A Immunofluorescence staining showed decreased expression of GFAP, cGAS, and STING following treatment (scale bar = 25 μm); B Immunofluorescence staining showed reduced CD86, cGAS, and STING expression (scale bar = 25 μm); C, D Western blot analyses confirmed that treatment significantly suppressed the cGAS-STING signaling pathway; E Western blot analysis of IL-6 and TNF-α signaling showed no significant differences. Data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent sample t-tests. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. * indicates p < 0.05 between groups: experimental animals, n = 6.

Western blot analysis revealed that CCI mice exhibited significant upregulation of TDP-43, cGAS, STING, p-TBK1/TBK1, p-IRF3/IRF3, p-STAT1/STAT1, CD86, and GFAP compared with the sham group (Fig. 7C). TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 administration significantly downregulated these proteins, confirming suppression of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway. To evaluate whether the therapeutic effect was specifically mediated by TDP-43 regulation, we conducted a control experiment using a non-specific anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Immunofluorescence results showed that cGAS/GFAP and STING/GFAP expression was significantly upregulated in the CCI group versus sham, and that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 treatment—but not NSAID—effectively suppressed their expression (Fig. 7A, B). Similar trends were observed in IBA1-positive microglia, suggesting a TDP-43-specific mechanism of action.

To further validate the direct role of TDP-43, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of TDP-43 (5′-GAGACUUGGUGGUGCAUAA-3′)42. Western blot analysis demonstrated that si-TDP-43 significantly reduced the expression of TDP-43, cGAS, STING, p-TBK1/TBK1, p-IRF3/IRF3, and p-STAT1/STAT1 compared to the CCI group (Fig. 7D).

Moreover, Western blot results showed that TNF-α and IL-6 levels were significantly elevated in the CCI group and that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 effectively suppressed their expression (Fig. 7E), further supporting the conclusion that the nanoparticles primarily exert their therapeutic effect via modulation of the immune response. Collectively, these findings indicate that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 alleviates NP by suppressing activation of the cGAS-STING signaling pathway.

TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 inhibit cGAS-STING pathway activation to protect astrocytes and microglia

We further investigated whether TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 exert protective effects against LPS-induced activation of astrocytes and microglia through the cGAS-STING pathway. Primary astrocytes and microglia were co-incubated with the STING activator SR717. CCK8 assays revealed that SR717 significantly reversed the increase in cell viability induced by TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in primary astrocytes and microglia (Fig. 8A). Additionally, SR717 reversed the C3 and S100A10 expression changes in injured primary astrocytes and CD86 and CD206 expression in microglia induced by TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 (Fig. 8B–D). These findings indicate that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 protect primary astrocytes and microglia from LPS-induced damage by inhibiting the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway.

A CCK8 assays showed that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 treatment significantly increased the viability of primary astrocytes and microglia; B Western blot analysis showed reduced expression of C3 and S100A10 in astrocytes and decreased CD86 and CD206 levels in microglia after treatment, indicating reversal of inflammatory phenotypes; C Immunofluorescence (scale bar = 25 μm) to detect C3 and S100A10 expression in primary astrocytes; D Immunofluorescence (scale bar = 25 μm) to detect CD86 and CD206 expression in microglia. Data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using independent sample t-tests. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. * indicates p < 0.05 between groups. Cell experiments were repeated three times.

Immunofluorescence analysis of brain sections stained for NeuN (mature neurons) and TUNEL (apoptotic cells) revealed no significant neuronal apoptosis in any group (Fig. S9A). Western blot analysis of Bax, Bcl-2, and cleaved Caspase-3 showed no significant differences among groups (Fig. S9B). TDP-43 expression in neurons, as evaluated by immunofluorescence, showed no nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio change (Fig. S9C), and Western blot analysis confirmed no difference in total TDP-43 levels (Fig. S9D). Immunofluorescence and Western blot detection of MAP2, NeuN, and β-II-tubulin revealed no significant changes in neuronal maturation among groups (Fig. S9E, F). Nissl staining confirmed no structural or functional neuronal abnormalities. Western blot analysis of cGAS-STING signaling in neurons showed no significant change among groups (Fig. S9G), suggesting that the suppressive effects of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in the CCI model are primarily exerted in microglia.

Discussion

The complexity of NP stems from its multifactorial pathophysiological mechanisms, particularly the interplay between microglia and astrocytes43. This study employed TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 to modulate the cGAS-STING inflammatory pathway, thereby reducing the crosstalk between these cells and significantly alleviating NP. Unlike previous studies, the innovation of this research lies in leveraging nanotechnology to optimize drug delivery, targeting cellular mechanisms of pain regulation rather than merely blocking pain signals.

In this study, the application of liposomal nanoparticles as carriers not only enhanced the efficiency of drug delivery to the brain but also increased the drug’s affinity for specific cell types through surface modifications with PS and TF. This special design allowed for more effective drug accumulation in microglia and astrocytes compared to traditional liposomes, addressing an area less explored in prior research. This approach potentially reduces side effects and improves therapeutic efficacy, offering a strategy for NP treatment.

In neuroscience, TDP-43 aggregation inhibitors have primarily been studied in models of neurodegenerative diseases27,44. These inhibitors exert their effects through multiple mechanisms, including suppression of pathological aggregation, restoration of nuclear function, regulation of RNA metabolism, and modulation of inflammatory responses. TDP-43 undergoes liquid–liquid phase separation via its C-terminal low-complexity domain (LCD), forming dynamic liquid droplets. Under pathological conditions, these droplets can transition into irreversible aggregates45,46. Aggregation inhibitors can disrupt LCD-mediated intermolecular interactions and maintain the dynamic equilibrium of phase separation. Moreover, TDP-43 pathology not only affects neurons but also triggers activation of glial cells, especially microglia and astrocytes, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, thereby exacerbating neuroinflammation and injury47,48. TDP-43 aggregates activate TLR4/MyD88 signaling and facilitate NF-κB nuclear translocation, a process that can be attenuated by aggregation inhibitors to reduce inflammatory cytokine expression. This study’s TDP-43 aggregation inhibitors effectively alleviate NP caused by inflammatory interactions between microglia and astrocytes. This mechanism has been rarely reported in previous studies, paving the way for the application of TDP-43 aggregation inhibitors in pain management and providing evidence for their anti-inflammatory effects. Although our data indicate that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 reduced TDP-43 protein levels and downstream cGAS-STING signaling, the study lacks direct evidence (e.g., immunofluorescence or filter-trap assays) to visualize TDP-43 aggregation in glial cells activated by CCI. This limitation precludes a definitive conclusion as to whether the therapeutic effect is mediated by disrupting pre-existing aggregates or preventing the formation of new ones. Future studies will employ techniques such as sarkosyl-insoluble fractionation or thioflavin T staining to quantify TDP-43 aggregation in this model.

The cGAS-STING pathway is a crucial component of intrinsic cellular immunity, significantly regulating inflammation and immune responses49. While this pathway’s role in autoimmune and infectious diseases has been extensively studied, its specific involvement in NP remains unclear50,51. Our research demonstrates that modulating the cGAS-STING pathway can significantly regulate the activity of microglia and astrocytes, reducing inflammation and pain. This finding provides experimental evidence for the potential application of this pathway in NP treatment.

Our results demonstrate that the functional effects of the TDP-43 aggregation inhibitor TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 are primarily exerted in microglia rather than neurons. This observation is consistent with previous studies indicating that glial cells, particularly microglia and astrocytes, play crucial roles in the transmission of nociceptive information. Modulating glial activation alters the secretion profile of inflammatory mediators and reduces neuronal excitotoxicity without directly suppressing neuronal activity52,53. While TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 may indirectly improve neurotransmitter imbalance by attenuating glial inflammation, its direct effects on neurotransmitter systems remain to be further elucidated. Future research will explore how TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 modulates synaptic neurotransmission (e.g., Glu/GABA balance) and plasticity (e.g., spine density) in NP. Our CCI model enables direct measurement of spinal LTP and mEPSCs, while blood-brain barrier–penetrating liposomal nanoparticles can be targeted to the synaptic microenvironment. These findings may help identify synaptic biomarkers for pain staging or inform combination therapies with neuromodulators such as pregabalin.

Changes in cell polarization states are critical factors influencing the severity of NP54,55,56. In this study, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 significantly promoted the shift of astrocytes toward a neuroprotective phenotype and microglia toward an anti-inflammatory state. These results align with previous research on the role of cell polarization in neuroprotection and further emphasize the effectiveness of targeting specific cell states as a therapeutic strategy57,58.

The choice to use a CCI model in mice for this study was based on its ability to mimic the pathological features of human NP closely. However, every animal model has limitations, such as fully replicating all biomarker changes observed in human pathology. Future research should consider using other models, such as genetic or alternative mechanical injury models, to further validate our findings and explore their applicability across different types of NP.

This study proposes a strategy for treating NP using liposomes loaded with a TDP-43 aggregation inhibitor to regulate the cGAS-STING pathway. Clinically, NP is a widespread and challenging condition to treat, with traditional therapies such as antidepressants, antiepileptics, and local anesthetics often providing limited efficacy and significant side effects. The approach in this study targets vital regulatory pathways of neuroinflammation, directly acting on crucial cell types involved in the pathological process, and shows potential for alleviating pain symptoms. Optimizing the drug delivery system can also increase drug concentration in target areas, enhance therapeutic effects, and reduce systemic side effects. The successful application of this strategy could provide more effective and safer treatment options for NP and other similar inflammation-related neurological disorders. This study mainly focused on the role of glial cell–neuron interactions in the central nervous system (spinal cord and brain) during neuropathic pain. Although we confirmed that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 had no significant effect on neuronal apoptosis or functional markers (Fig. S9), we did not systematically evaluate its role in peripheral nerve repair following sciatic nerve injury. This limitation arises from the CCI model, which primarily simulates nerve compression rather than transection, making the assessment of peripheral regeneration challenging. Future studies will adopt sciatic nerve crush or transection models, combined with morphological (nerve fiber density) and functional (nerve conduction velocity) assessments, to comprehensively evaluate the peripheral repair potential of this nanomedicine. In addition, while the statistical analysis supplemented for Fig. S9C supports the observed nuclear-to-cytoplasmic distribution trend of TDP-43, the limited resolution of the images warrants cautious interpretation. Future research will employ higher-resolution imaging techniques, such as confocal microscopy or super-resolution imaging, to more accurately validate TDP-43 localization. Together, these directions will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic effects of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 on both central and peripheral mechanisms of neuropathic pain.

Neuronal hyperexcitability is a hallmark feature of NP, often driven by the upregulation of voltage-gated ion channels (e.g., Nav1.3, Nav1.7, Cav3.2) and nociceptive receptors (e.g., TRPV1, P2X3)50. Accumulation of TDP-43 has been reported to interfere with RNA processing, leading to abnormal splicing and destabilization of transcripts encoding key ion channels such as Kv1.2, thereby contributing to increased neuronal excitability. By reducing TDP-43 aggregation, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 may restore ion channel homeostasis and suppress aberrant firing. In addition, microglia–neuron communication via the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 and CCL2-CCR2 axes drives the chronicization of NP55. TDP-43 aggregates may enhance chemokine release via microglial TLR4/MyD88 activation, while TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 may downregulate CX3CL1 and CCL2 expression, disrupting this pathological crosstalk.

Despite the promising theoretical and experimental results, several limitations exist. First, the findings are primarily based on animal models, specifically the CCI model in mice, which, although replicating some critical features of human NP, cannot fully replicate human pathological states. Physiological and pathological responses in animal models may differ from those in humans, presenting uncertainties in translating these findings to human applications. In addition, to minimize physiological variability caused by hormonal cycles, only male mice were used in this study. However, we fully recognize that sex differences may influence neuroinflammation and analgesic responses. Therefore, future studies will include both male and female mice to systematically evaluate sex-dependent therapeutic effects of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, thereby enhancing the translational relevance of our findings. Inhibiting TDP-43 aggregation may cause unintended interactions with other RNAs, such as precursor microRNAs or long non-coding RNAs, which could disrupt normal gene expression. Additionally, TDP-43 inhibitors might cross-react with other TDP family members or RNA-binding proteins like FUS and hnRNPA1, potentially affecting their normal biological functions. Secondly, the transient therapeutic effects observed in this study highlight some inherent challenges associated with central nervous system delivery of nanomedicines, including formulation stability, sustained targeting, and the complex pathological microenvironment. Integration of materials engineering, combinatorial therapeutic strategies, and dynamic monitoring techniques may help overcome these limitations and promote the translation of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 from an experimental platform to a clinically viable and long-acting analgesic solution. In our future research, we aim to improve nanoparticle stability and controlled release profiles, and systematically evaluate the efficacy and safety of enhanced therapeutic strategies. This study did not assess long-term treatment outcomes, including the potential for delayed adverse effects or drug tolerance. Furthermore, as a nanocarrier system, long-term studies assessing the biosafety and controllable release of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 are still lacking. Although short-term results are encouraging, the long-term implications of repeated administration require further investigation. Given the hormonal differences between sexes, it is plausible that TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 may exert sex-dependent therapeutic effects. Evaluating efficacy in both male and female subjects will be a critical component of our subsequent studies. The targeted delivery mechanism of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 may involve ligand–receptor interactions such as recognition between TFRC on endothelial cells and TREM2 on microglia59, or may rely on lysosomal pathways mediated by LAMP160. Understanding these targeting mechanisms is essential to elucidating how TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 exerts its therapeutic effects and will be the focus of our future investigations.

In light of the current findings and limitations, future research should proceed in several key directions. First, additional preclinical studies are needed to validate the therapeutic efficacy of this strategy across different types and stages of NP models and to explore its potential applications in other neurological disorders. Second, clinical trials are necessary to assess the safety and efficacy of this approach in humans, especially regarding its feasibility and performance during long-term treatment. Furthermore, the nanoparticle design must be further optimized to improve in vivo stability and biocompatibility, thereby ensuring precise and efficient drug delivery. These efforts aim to translate this emerging therapeutic strategy into a reliable clinical treatment, offering innovative solutions for NP and other neurological diseases.

Considering the integration of TF, PS, and the TDP-43 aggregation inhibitor in the formulation of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, its preparation involves multistep conjugation and encapsulation procedures, which may be challenged by variable coupling efficiency and limited drug loading capacity. Additionally, due to potential procoagulant risks associated with TF modification and PS exposure, toxicity studies in multiple species, including long-term (≥ 6 months) repeated-dose studies in non-human primates, should be conducted before clinical translation.

Currently, clinical treatments for NP rely primarily on antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline), antiepileptic drugs (e.g., gabapentin), and opioids, all of which suffer from limited efficacy and significant side effects61,62. The present study proposes a “nanocarrier-targeted delivery-glial polarization modulation” triad strategy. By modifying liposomes with PS and TF, this system crosses the BBB and selectively accumulates in microglia and astrocytes, enhancing local drug concentration at lesion sites. Moreover, by inhibiting TDP-43 aggregation and modulating the cGAS-STING pathway, while simultaneously regulating inflammatory cascades and glial polarization, it achieves a multi-target therapeutic effect superior to single-pathway blockade. The targeting capability of the nanocarrier reduces systemic exposure and minimizes hepatic and renal toxicity, which is particularly advantageous for chronic pain patients requiring long-term medication.

NP therapies have primarily targeted neuronal excitability, such as with sodium channel blockers, while largely neglecting the pivotal role of glial cells in the persistence and amplification of pain63,64. This study demonstrates that promoting neuroprotective astrocyte polarization and anti-inflammatory microglial polarization enhances the release of neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF, GDNF), thereby supporting neuronal survival and axonal regeneration. Dysregulation of glial polarization is a critical contributor to the transition from acute to chronic pain; restoring balanced glial phenotypes may help reverse pathological pain progression. In future clinical applications, individualized therapeutic strategies could be informed by monitoring glial markers (e.g., C3, Arg1) in cerebrospinal fluid or blood. Furthermore, real-time assessment of glial activation status using PET imaging probes (e.g., TSPO ligands) may help optimize treatment timing and dosage.

In summary, to explore effective strategy to treat NP, we constructed a liposomal delivery system loading with a TDP-43 aggregation inhibitor regulate the activation of the cGAS-STING inflammatory pathway, reducing microglia-astrocytes crosstalk (Fig. 9). This study offers a perspective on the clinical treatment of NP. However, the research has limitations regarding animal models, long-term safety, and specific mechanisms. Future work should include clinical trials, optimization of the drug delivery system, and in-depth mechanistic studies to expand the application scope and enhance therapeutic efficacy.

The molecular mechanism of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 regulates the cGAS-STING inflammatory pathway, mediating microglia-astrocyte crosstalk and affecting NP (Created in BioRender. J M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/34tusv0).

Methods

Preparation of liposomes

Liposomes loaded with the TDP-43 inhibitor (TDP-43-in, HY-163574, MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China) were prepared using the thin-film hydration method. The liposomes were modified with PS and TF and designated as TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1. Another set of liposomes containing DSPE-PEG2000 was referred to as TDP-43-IN-1. The formulations of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 were as follows: PS/1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate (1-propyl glycerol) (DPPG)/TF/lecithin/cholesterol (Chol)/TDP-43-in in a ratio of 1:4:2:12:1:8 (w/w/w/w/w/w) and PS/DPPG/DSPE-PEG2000/lecithin/Chol/TDP-43-in in a ratio of 1:4:2:2:12:1:8 (w/w/w/w/w/w/w), respectively.

The lipid materials were dissolved in a mixture of anhydrous methanol and chloroform (1:3). The solution was then evaporated under reduced pressure at 40 °C for 1 h to form a uniform lipid film. This film was frozen overnight at −20 °C, followed by hydration in a 40 °C ammonium sulfate solution for 1 h. TDP-43-in was dissolved in 1.0 mL of saline and added to the liposome suspension. The product was dialyzed in saline for 2 h and then in pure water for an additional 2 h. Post-dialysis, the solution within the dialysis bag was sonicated using a JN-900D ultrasonicator. Finally, the solution was lyophilized to yield TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1. DiR-labeled liposomes were prepared by adding an appropriate amount of DiR (1:5%, w/w) (D12731, Invitrogen, USA) to the lipid powder.

The specific formulation of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 consisted of PS, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate (1-propyl glycerol) (DPPG), TF, lecithin, cholesterol (Chol), and a TDP-43 inhibitor (TDP-43-in). The weight ratio of these components was PS:DPPG:TF:lecithin:Chol:TDP-43-in = 1:4:2:12:1:8.

Encapsulation efficiency (EE) and drug loading capacity

To measure EE, the drug was encapsulated into individual liposome formulations and then centrifuged (130,000 × g, 4 °C for 1 h) to remove any unencapsulated drug, followed by resuspension in fresh phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The liposomes were placed in a dialysis bag (3.5 kD; Spectrum Labs, Rancho Dominguez, CA). At predetermined time points (t = 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 h), the supernatant was collected and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Liposomes were centrifuged at 130,000 × g at 4 °C for 1 h to assess the loading efficiency. HPLC determined the concentration of TDP-43-in in the supernatant. EE was calculated using the formula EE = (DT–DU)/DT × 100, where DT represents the total amount of drug added during the formulation process, and DU is the amount found in the supernatant.

The in vitro drug release from TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 was determined using a dialysis method. At each predetermined time point, 4.0 mL of liposome suspension was sampled for analysis in PBS (pH 7.4 and pH 5.0, at 37 °C), and an equal volume of fresh release medium was added. The drug release was quantified using HPLC. Cumulative drug release for TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 was calculated and plotted to generate release profiles.

Particle size distribution

The particle size, zeta potential, and polydispersity index (PDI) of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 were measured using a Zeta Plus laser particle size analyzer at 25 °C. The stability of both liposome formulations was assessed after storage at 4 °C for 28 days using the same analyzer.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The morphology of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1 was examined using a JEM-2100 TEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). A 10 μL sample of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 or TDP-43-IN-1 in purified water (2 mg/mL) was applied to a carbon-coated copper grid (200 mesh) and negatively stained with a 2% solution of phosphotungstic acid (PTA) for 2 min.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis

The surface elemental composition of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TF/TDP-43-IN-1 was determined using a K-Alpha XPS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The analysis was conducted with ten scans using an Al-Kα X-ray source, and the analyzed spot size was 650 μm.

Hemocompatibility test

Blood samples were collected from C57BL/6J mice and washed three times with saline. Subsequently, a 2% red blood cell suspension was incubated with various concentrations of liposome formulations (3.125–100 μM), saline (negative control), or distilled water (positive control) at 37 °C for 30 min. The samples were then centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 min. Absorbance at 415 nm was measured to quantify hemoglobin released in the supernatant. The hemolysis percentage was calculated using the positive control absorbance as 100%.

Cell culture and identification

Primary astrocytes and microglia were isolated from the cerebral cortex of three neonatal mice. The brain tissues were digested with trypsin, gently agitated, and resuspended in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) supplemented with 10% bovine serum (10099158, Gibco, Shanghai, China) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (C0222, Beyotime). The cell suspension was filtered and seeded into flasks coated with poly-L-lysine (P1524, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). After 12–14 days, microglia was separated from the mixed glial culture by orbital shaking at 200 × g for 1 h. The supernatant containing microglia was then replated onto poly-D-lysine-coated T-flasks. For the astrocytes cultures, any remaining microglia were removed by overnight shaking at 300 × g. Adherent cells were then reseeded to enrich for astrocytes.

Primary astrocytes and microglia were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well into a 24-well plate for immunofluorescence identification. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton ×-100 for 20 min. Blocking was performed with 5% normal goat serum containing 0.25% Triton ×-100 at room temperature for 4 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The cells were then incubated with appropriate fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. GFAP and CD68 immunofluorescence were used to detect astrocytes and microglia after 14-21 days of culture.

In the treatment groups, astrocytes and microglia were incubated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng/mL) (00-4976-93, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) for 1 h, followed by treatment with fresh serum-free DMEM containing TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 (equivalent to 5 μmol/L TDP-43-in), si-TDP-43(GCTCTAATTCTGGTGCAGCAA) for 72 h in a standard culture environment (37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity). High-quality fetal bovine serum and media, along with sterile plasticware designed explicitly for tissue culture, were used to ensure the quality of cell cultures65.

Astrocytes and microglia were incubated with LPS for 1 h. Subsequently, these cells were co-incubated with various compounds for further experiments. These compounds included PS (HY-A0183, MedChemExpress (MCE), Shanghai, China), 2-deoxy-D-glucose (HY-13966, MCE, Shanghai, China), colchicine (HY-16569, MCE, Shanghai, China), methyl-β-cyclodextrin (HY-101461, MCE, Shanghai, China), chlorpromazine (HY-12708, MCE, Shanghai, China), and the STING activator SR717 (HY-131454, MCE, Shanghai, China).

In vitro safety evaluation of liposomes

The cytotoxicity of liposomes on astrocytes and microglia was assessed using the CCK-8 assay. Different concentrations of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 and TDP-43-IN-1, ranging from 0 to 200 μg/mL, were incubated with astrocytes and microglia for 48 h, after which cell viability was measured.

In vitro uptake assay

The mechanism of liposomal uptake induced by LPS in primary cultured astrocytes was investigated. Primary astrocytes and microglia were treated with TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR + TF (equivalent to 5 μmol/L TDP-43-in and 100 μg/mL TF) for 30 min and 4 h. Following treatment, cells were washed three times with PBS, fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min, and stained with DAPI (500 ng/mL) for 15 min. Fluorescent images were captured to visualize the uptake of liposomes.

Quantification of liposome internalization was performed using flow cytometry. In brief, primary astrocytes and microglia were cultured with TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR + TF. After treatments, cells were washed thrice with PBS, digested with 0.25% trypsin, and resuspended in PBS. Flow cytometry was utilized to analyze the uptake of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1. Liposomal uptake was also observed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71, Olympus, Japan).

In vitro BBB permeability studies

bEnd.3 cells (CL-0598, Wuhan Ponsaic Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per insert in the upper chamber of a Transwell apparatus and cultured to form a monolayer. The integrity of the monolayer was confirmed by achieving a transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) of over 200 Ω/cm2. TDP-43-IN-1-DiR and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR were applied to the upper chamber and incubated for 4 h. The permeability of the liposomes across the BBB was quantified by measuring the fluorescence in the lower chamber using a spectrophotometer65.

Dual targeting efficacy of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in vitro

Each well of a 24-well plate was seeded with three aliquots of cells (1 × 105 cells each). TDP-43-IN-1-DiR and TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR were added to the upper chamber and incubated for 1 or 6 h. At predetermined time intervals, the solution in the lower chamber was analyzed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer to calculate the penetration efficiency of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 across the in vitro BBB. Primary astrocytes and microglia collected from the lower chamber were analyzed via flow cytometry. Furthermore, cells in the lower chamber were fixed in 4% PFA and stained with DAPI, and their uptake of liposomes was assessed using a fluorescence microscope. This allowed for the observation of liposome uptake by primary astrocytes and microglia.

Observation of the cellular uptake process of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1

TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 was immobilized on a 24-well plate overnight. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 4 × 10⁴ astrocytes were seeded and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO₂, and 95% relative humidity for 24 h. Cells were then transferred to 8-well chamber slides for further analysis. For fluorescence microscopy, 2.3 × 10⁴ cells were seeded on 8-well slides and incubated with FITC-labeled TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 for 1, 4, or 24 h. Cells were washed with Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺-containing PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min at room temperature. After three PBS washes, cells were blocked with iTFx signal enhancer (Thermo Fisher, Germany) for 30 min, followed by incubation with Cy3-conjugated streptavidin antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 min. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA) for 10 min. Fluoromount (Dako, Hamburg, Germany) was applied for preservation. Images were captured using a widefield microscope (Zeiss Cell Observer Z1, Carl Zeiss, Germany) and a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II, Germany)66.

Protective effects of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 on primary astrocytes

Following LPS induction, the culture medium was discarded, and each well was replenished with 100 µL of serum-free medium containing 10% CCK-8. After 2 h, absorbance at 450 nm was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader to calculate cell viability. Primary astrocytes and microglia were seeded in 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well). Post-LPS treatment, cells were harvested and lysed using RIPA buffer. Western blot assessed the expression of PSR, C3, S100A10, CD86, and CD206 proteins in primary astrocytes and microglia.

Model establishment

To establish a mouse chronic constriction injury (CCI) model for simulating NP, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 1% sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). The sciatic nerve on the left mid-thigh was exposed and ligated proximally with three 7-0 Prolene sutures spaced 1 mm apart until a brief twitch in the left hind limb was observed. In the sham group, mice underwent the same anesthesia and sciatic nerve exposure procedure without nerve ligation. Both sham and CCI groups received sciatic nerve exposure and ligation surgeries.

Mice were divided into sham, CCI, CCI + TDP-43-in, CCI + TDP-43-IN-1, and CCI + TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 groups. Prophylactic groups received a preoperative intrathecal injection of 5 µL TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 1 h before surgery. The treatment groups were given a therapeutic intrathecal injection of 5 µL TDP-43-in, TDP-43-IN-1, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1, NASID group on the 8th day post-operation. The sham and CCI groups received a 5 µL intrathecal saline injection65. In the NASID group, 5 μL of NASID (SPEDIFEN, USA) was intrathecally injected. Behavioral tests were conducted before the mice were euthanized with CO2, and the L4–L5 spinal cord tissues were collected for further analysis67.

Biodistribution of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 in mice

In vivo, TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1 biodistribution was assessed in both sham and CCI mice. Mice were administered DiR, TDP-43-IN-1-DiR, or TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1-DiR via tail vein injection. Subsequently, animals were imaged using an in vivo imaging system (IVIS, MS lumina XRMS, PerkinElmer) to visualize the distribution of DiR red fluorescence. DiR fluorescence was quantified using UV spectrophotometry. The anterior cingulate cortex was cryosectioned to assess liposome distribution. Nuclei were stained with DAPI, and fluorescence microscopy was used for imaging.

Mechanical allodynia testing

Mice were acclimated for 30 min in transparent plastic boxes on a glass surface. For mechanical sensitivity, mice were placed on a wire mesh platform and stimulated on the ipsilateral hind paw using von Frey filaments with logarithmically increasing stiffness (0.16–2.00 × g, Stoelting). The 50% paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was calculated using Dixon’s up-down method. Thermal withdrawal latency (TWL) was measured using a Hargreaves apparatus (IITC/Life Science, CA, USA), with a cutoff time of 25 s. Baseline TWL was recorded one day prior to CCI induction. Testing was performed on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 14 post-surgery. Each test was repeated three times at 5-min intervals, and the average was used as TWL. Cold allodynia was induced by applying 50 μL of acetone to the plantar surface of the affected paw. Reflexive behaviors such as licking or withdrawal within 10 min were recorded. Paw edema following Listeria monocytogenes-induced inflammation was measured using a water displacement plethysmometer (Ugo Basile). All behavioral assessments were performed and analyzed in a blinded fashion68.

Thermal hyperalgesia testing

Mice were acclimated for 30 min in transparent plastic boxes on a glass surface. Thermal withdrawal latency (TWL) was assessed using a Hargreaves radiant heat device (IITC/Life Science, CA, USA), stimulating the hind paw until a withdrawal response was induced. Responses include lifting, dodging, or flinching of the foot. A cutoff time of 25 s was set to prevent tissue damage. Baseline TWL was recorded one day before the induction of CCI. Thermal hyperalgesia tests were performed on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 14. Three measurements were taken at 5-min intervals, with the average recorded as the TWL.

ELISA

Blood was drawn from the abdominal aorta and centrifuged at 72 h to collect plasma. Concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (JN17113, Ji Ning Industrial, Shanghai, China), interleukin-6 (IL-6) (JN16894, Ji Ning Industrial, Shanghai, China), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) (JN16939, Ji Ning Industrial, Shanghai, China) were measured using ELISA. Absorbance at 450 nm was detected with an ELISA reader.

In vivo safety evaluation of TF/PS/TDP-43-IN-1

Multiple organ tissues were collected from CCI mice and fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h. Subsequently, the tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Tissue morphological changes were observed under an inverted microscope. Serum biochemical markers, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT, JN20465), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, JN20681), blood urea nitrogen (BUN, JN55961), and creatinine (CREA, JN7806), were assessed using assay kits purchased from Ji Ning Industrial, Shanghai, China, following the manufacturer’s protocols.

Western blot analysis of protein expression in tissues and cells

Cellular proteins were quantified from whole-cell lysates using the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (23227, Thermo Fisher, USA). Proteins from extracellular vesicles (EVs) and cells were extracted using RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 1% Triton ×-100). Equal amounts of protein from each sample (5–10 µg for EV extracts (EVE) and 20 µg for whole-cell extracts (WCE)) were loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels for electrophoresis and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and then incubated overnight with primary antibodies: mouse anti-GAPDH (ab8245, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-TDP-43 (ab109535, Abcam, UK), rabbit anti-PSR (NBP1-71693, Bio-Techne China), rabbit anti-C3 (ab97462, Abcam, UK), rabbit anti-PSR (NBP1-71693, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-C3 (ab97462, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-S100A10 (NBP1-89370, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), mouse anti-CD86 (NBP2-25208, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-CD206 (NBP1-90020, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-IBA1 (ab178846, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-GFAP (NB300-141, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-cGAS (NBP3-16666, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-STING (ab288157, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-p-TBK1 (5483, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-TBK1 (3504, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-p-IRF3 (79945, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-IRF3 (11904, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-p-STAT1 (9167, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Shanghai, China), and rabbit anti-STAT1 (9172, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-BAX (ab32503, Abcam, UK), rabbit anti-cleaved Caspase-3 (ab32042, Abcam, UK), rabbit anti-Bcl-2 (ab182858, Abcam, UK), rabbit anti-MAP2 (ab5392, Abcam, UK), rabbit anti-NeuN (ab177487, Abcam, UK), and rabbit anti-β-II-tubulin (ab179512, Abcam, UK). All antibodies were diluted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The next day, secondary antibodies (Peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) #111035003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA, or Peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) #115035003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA) were incubated for 1 h. The immune-reactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (WP20005, Thermo Fisher, USA), and images were captured with the ChemiDoc XRS Plus luminescent image analyzer (Bio-Rad). Image J software was used for densitometric quantification of the Western blot bands, with GAPDH serving as the internal control. Each experiment was repeated three times. All the original WB images can be found at the Supplementary Information.

RT-qPCR analysis of gene expression in tissues and cells

Total RNA was extracted from tissues and cells using Trizol reagent (15596026, Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (RR047A, Takara, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on the synthesized cDNA using the Fast SYBR Green PCR Kit (Catalog No: 11736059, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) with triplicate wells for each sample. GAPDH was used as the internal control. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The experiment was conducted three times. Primer sequences used for RT-qPCR, synthesized by Takara, are listed in Table S1.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cell samples were fixed with 4% PFA at room temperature for 15 min and then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37 °C for 30 min to prevent non-specific staining. Cells were incubated overnight with primary antibodies, washed three times with PBS for 3 min each, and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

For animal tissue samples, after behavioral tests, mice were euthanized via CO2 inhalation, and L4–L5 spinal cord tissues were harvested. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) prepared in 100 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, China). Tissues were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, embedded in OCT compound (45345, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and frozen at −20 °C. Coronal cryosections of the anterior cingulate cortex (30 μm thick) were prepared using a cryostat (CM1520, Leica Microsystems, Shanghai, China). Tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies in a humidified chamber for 12 h, washed with PBS, and then incubated with secondary antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Finally, the sections were washed in PBS and mounted on slides. All immunofluorescently labeled sections were observed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Primary antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-C3 (ab97462, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-S100A10 (NBP1-89370, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), mouse anti-CD86 (NBP2-25208, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-CD206 (NBP1-90020, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-IBA1 (ab178846, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-GFAP (NB300-141, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), rabbit anti-CD86 (ab239075, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-cGAS (NBP3-16666, Bio-Techne China Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), and rabbit anti-STING (ab288157, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rabbit anti-NeuN (ab177487, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and rabbit anti-MBP (ab7349, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 594-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (ab150160, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (ab150081, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). All antibodies were diluted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For neuronal assessment, brain tissue sections were subjected to Nissl staining (Beyotime, Shanghai, China; Cat. No. C0117).

Single-cell analysis