Abstract

In 2022, Europe faced an extensive summer drought with severe socioeconomic consequences. Quantifying the influence of human-induced climate change on such an extreme event can help prepare for future droughts. Here, by combining observations and climate model outputs with hydrological and land-surface simulations, we show that Central and Southern Europe experienced the highest observed total water storage deficit since satellite observations began in 2002, probably representing the highest and most widespread soil moisture deficit in the past six decades. While precipitation deficits primarily drove the soil moisture drought, human-induced global warming contributed to over 30% of the drought intensity and its spatial extent via enhanced evaporation. We identify that 14–41% of the climate change contribution was mediated by the warming-driven drying of the soil that occurred before the hydrological year of 2022, indicating the importance of considering lagged climate change effects to avoid underestimating associated risks. Human-induced climate change had qualitatively similar effects on the extremely low observed river discharges. These results highlight that global warming effects on droughts are already underway, widespread and long lasting, and that drought risk may escalate with further human-induced warming in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

During the 2022 summer, Central and Southern Europe experienced an extreme drought characterized by very low soil moisture and river water levels, severely impacting multiple sectors across many countries. Impacts included limited municipal water supply, reduced crop yields, extensive wildfires, decreased hydropower generation, navigation restrictions in rivers and compromised stability of dykes1,2,3,4. For example, in Italy, half of the population faced water restrictions3, while in France, 60% of the regions were on the highest drought alert with over 100 municipalities receiving drinking water via trucks1,3. Beyond restricting domestic water consumption, the drought diminished water reserves for irrigation, exacerbating soil dryness and impacting agriculture. Grain maize, sunflower and soybean yields across Europe dropped by an average of 15% compared with the past 5 years, with the strongest impacts in France, Italy, Germany, Slovenia, Hungary and Romania1,3. For instance, Italy’s Po River basin saw a 30% decrease in rice yields, while suffering amplified agricultural impacts from a record-breaking 40 km inland saltwater intrusion due to reduced river discharge3,4. Furthermore, vegetation impacts5 were magnified by the high fire risk that resulted in the second-largest burnt area in Europe since 2000 (ref. 6), affecting especially Italy, Slovenia, France and Romania2. Originally driven by a strong precipitation deficit, the meteorological drought ultimately transitioned into low river discharges with extensive impacts. Reduced river water levels along the river Rhine disrupted shipping, impacting coal and oil transport in Germany and the Netherlands1,7. This exacerbated the energy strain amid increased air conditioning demand and reduced energy production owing to diminished river levels2. In fact, the low river levels affected the cooling systems in nuclear power plants, leading to reduced electricity generation and reactor shutdowns on the Belgium–France border2,8. Moreover, diminished reservoir water levels due to low river flow reduced hydropower generation, as exemplified by Portugal storing less than half the average hydroelectric energy1 and Italian power plants generating 40–50% less electricity, temporarily shutting down one plant in Piacenza2.

The widespread societal repercussions of the event highlighted water management as a crucial priority for stakeholders and emphasized the need for a deep understanding of the drought drivers, including the contribution of human-induced climate change to the event. In turn, the scientific community started providing important information on the event1,2,3,4,5. Schumacher et al.2, by focusing on West–Central Europe, which represents only a part of the affected area, identified that climate change has probably made common soil moisture droughts more probable, but they could not rule out a null or even opposite effect. On the basis of reanalyses weather data, Faranda et al.3 showed that the meteorological conditions during the drought were associated with a persistent anti-cyclonic anomaly, whose underlying hot–dry atmospheric conditions have probably been enhanced by human-induced global warming. However, they indicated that climate model simulations are required to disentangle the effects of human-induced climate change9,10. By considering a drought index capturing only recent weather dynamics, Faranda et al.3 may have neglected lagged effects on the drought, that is, effects from human-induced warming and precipitation trends before the hydrological year of 2022. Such effects may have exacerbated the drought by soil drying before 2022 via long-term warming, but so far the relevance of this effect remains unclear. Furthermore, the spatially compounding nature of the drought11, which encompassed multiple countries simultaneously with potentially compounding impacts, raises questions with respect to the extremeness of the drought’s spatial extent and the influence of human-induced climate change on this extent.

Notwithstanding the findings from earlier studies2,3, it is unclear how weather anomalies before the event contributed to the 2022 summer drought and how human-induced climate change affected the drought through changes in precipitation and temperature across different seasons before the event. Here, we combine hydrological and land-surface models with a suite of precipitation and temperature data from observations and 23 climate models to disentangle the direct and lagged effects of weather anomalies and human-induced climate change on the drought. We take a ‘storyline approach’12, that is, given the meteorological conditions driving the drought, we assess how human-induced climate change affected drought intensity and spatial extent. We derive soil moisture, river discharge and total water storage via hydrological simulations of the mesoscale Hydrological Model (mHM)13,14,15 driven by observed precipitation and temperature from the E-OBS dataset16 (hereinafter, mHM–E-OBS), which shows good agreement with observations (Extended Data Fig. 1). Given the known uncertainties in modelling soil water dynamics via different hydrological and land-surface models17,18, we confirm the results’ robustness for soil moisture and total water storage via simulations from the Community Land Model (CLM)19,20, a land-surface model, driven by the ERA5 reanalysis21 (CLM–ERA5) (Methods).

One of the most extreme soil moisture droughts in 60 years

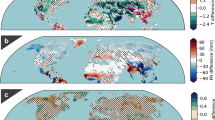

Satellite observations and hydrological simulations indicate that the 2022 drought was one of the most extreme of the last decades in Central and Southern Europe. Hydrological simulations based on the mHM–E-OBS setup starting in 1960 reveal that the 2 m soil moisture deficits in June–August (JJA) 2022 were the highest on record in many regions in Europe (Fig. 1a, stippling) and, accordingly, the total soil moisture deficit in Central and Southern Europe (Fig. 1a, hereinafter, Europe), which was ~280 km3 (equivalent to 120 million Olympic swimming pools), was the most extreme (Fig. 1b). In line with documented widespread drought impacts1,2, the simulations reveal that the spatial extent of the soil moisture drought (here defined as the area with soil moisture anomalies below two s.d. from the 1960–2021 average) was also the largest since 1960 (29% of Europe in Fig. 1c; similarly for one and four s.d., but the event ranked as the second for three s.d.; Extended Data Fig. 2). These results about the extremeness of the soil moisture deficit are mirrored by total water storage anomalies from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite observations and hydrological simulations, which rank the JJA total water storage across Europe, as well as Central and Southern Europe individually, as the driest since observations started in 2002 (Extended Data Fig. 1b–d, circled dot in the bottom left corner), again emphasizing the large extent of the event (Extended Data Fig. 1g,h). We also note that simulations based on the CLM–ERA5 setup rank the total soil moisture deficit in the summer of 2022 as the second-lowest since 1960. However, the performance of CLM–ERA5 is not as good as mHM–E-OBS, in capturing both the ranking of 2022’s European total water storage drought and the spatial pattern of the event (Supplementary Information). Owing to these discrepancies, it is well possible that 2022 was the most extreme soil moisture drought since 1960, and hereinafter we focus on the results from mHM–E-OBS, but further consider the results from CLM–ERA5 in the final section, Implications and challenges for drought dynamics and risks.

a, The anomaly of the simulated JJA 2022 average soil moisture in units of s.d. of the JJA 1960–2021 distribution. The stippling indicates locations where 2022 was drier than any simulated summer in 1960–2021. b, The anomaly of the European total (over the box in a) JJA average soil moisture relative to 1960–2021 (Methods). c, The land area of Europe under severe drought, that is, under JJA average soil moisture anomaly below two s.d. of the 1960–2021 distribution. Simulations are based on the mHM.

Weather anomalies during and before the drought

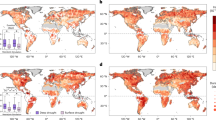

Given that lack of precipitation and warm conditions that enhance evaporation can lead to droughts18, we inspect the weather during and before the 2022 JJA drought event to understand the drivers of the summer drought. The 2022 summer was characterized and preceded by substantial weather anomalies (Fig. 2) associated with persistent high-pressure conditions over France3. In particular, JJA displayed a widespread lack of rainfall (–30% of the 1981–2010 average in median over Europe; Fig. 2c) with the exception of Greece and the south of Italy, where, accordingly, no soil moisture drought occurred in summer (Fig. 1a). At the same time, several heatwaves broke temperature records across many European countries2, contributing to an exceptionally warm summer (Fig. 2f), with the highest average temperature in Europe since 1960 (1.9 °C above the 1981–2010 average). The daily temperature range, which is a proxy for downwelling radiation and therefore is related to evaporation22, was also high over most of Europe (Fig. 2i). Notably, precipitation and temperature anomalies during the previous spring (March–May (MAM); Fig. 2b,e,h) and winter (December–February (DJF); Fig. 2a,d,g) were also substantial, and may have preconditioned the summer drought. For instance, the lack of rainfall in spring (Fig. 2b) affected most of Europe except for southern Spain, in particular its eastern coast, where no soil moisture drought was recorded. This indicates that precipitation anomalies across multiple seasons have probably contributed to the low summer soil moisture.

a, The anomaly derived from E-OBS data in mean precipitation (P) of DJF 2021–2022 relative to mean seasonal precipitation in 1981–2010, computed as a ratio (where >1 indicates wetter than average). b,c, The same as a, but for precipitation of MAM 2022 (b) and JJA 2022 (c). d–f, The same as a–c, but for the anomaly in average daily temperature (T), computed as the difference (>0 indicates warmer than average) for DJF 2021–2022 (d), MAM 2022 (e) and JJA 2022 (f). g–i, The same as a–c, but for the anomaly in the daily temperature range (Trange) (>1 indicates a higher daily temperature range than average) for DJF 2021–2022 (g), MAM 2022 (h) and JJA 2022 (i).

Influence of weather anomalies on summer soil moisture

Through soil moisture simulations23 (Methods), we disentangle the influence of weather anomalies on summer soil moisture, finding that both precipitation and temperature were important (Fig. 3, note that here we combined the contribution from anomaly in mean temperature and daily temperature range together). In particular, the compounding effect of hot–dry summer conditions reduced soil moisture over most of Europe (Fig. 3c,f). On average, the lack of rainfall contributed to −0.43 s.d. in summer soil moisture from the mean conditions, while high temperatures contributed −0.24 s.d., highlighting a relevant role of temperature anomalies in shaping the drought.

a, The anomaly in the JJA 2022 average soil moisture owing to the anomaly in precipitation during DJF 2021–2022, in units of s.d. of the JJA 1960–2021 distribution. The number on the top right shows the spatially weighted average across Europe (Fig. 1a). b,c, The same as a, but for the contribution to the JJA 2022 soil moisture drought from anomalies in precipitation of MAM 2022 (b) and JJA 2022 (c). d–f, The same as a–c, but for the contribution to the drought from combined anomalies in average daily temperature and daily temperature range for DJF 2021–2022 (d), MAM 2022 (e) and JJA 2022 (f). Simulations are based on the mHM.

The weather anomalies in spring and winter were also relevant. The lack of rainfall in spring (Fig. 3b) largely reduced summer soil moisture in Europe, by −0.39 s.d. on average. Nevertheless, in southern Spain, the abundant rainfall in spring (Fig. 2b) counteracted the hot–dry summer, averting a soil moisture drought in the following summer (Fig. 1a). Winter anomalies had a smaller impact (−0.09 s.d. for precipitation and −0.04 s.d. for temperature). However, regional precipitation effects were still substantial, particularly over the Iberian Peninsula, where the dry winter limited water accumulation for the subsequent summer (Fig. 3a). Notably, positive winter temperature anomalies in our analysis region do not markedly affect summer soil moisture (Fig. 3d), in line with expected low (or even negligible) evaporation in winter.

Overall, consistent with the relevance of lagged effects for the build-up of soil moisture droughts24,25,26,27,28, the above demonstrates that weather anomalies that occurred months before the soil moisture drought contributed substantially to its intensity. Altogether, the average influence of the winter-to-summer precipitation anomalies on summer soil moisture (−0.30 s.d.; Fig. 3a–c) and that of temperature (−0.13 s.d.; Fig. 3d–f) indicates that precipitation deficits were the key driver of the drought, while temperature anomalies exacerbated the event29,30. Finally, we note that the 2018–2020 (ref. 31) drought probably contributed to the drought in 2022 as soil moisture had not completely recovered in various regions by 20212.

Contribution of human-induced climate change to soil moisture

Weather anomalies affected the soil moisture drought, but it is unclear whether they arose merely from internal climate variability10 or were substantially modulated by human-induced climate change. Climate models of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) indicate potentially relevant changes in precipitation and temperature from human-induced climate change, but such changes vary widely across Europe and seasons (Extended Data Fig. 3), making direct connections to the drought challenging. In particular, climate models indicate that precipitation changes may have dried the soil in summer and wettened it during the preceding spring and winter on average in Europe (Fig. 4a), raising the question of how these opposing effects may have played out. Yet precipitation changes remain uncertain owing to differences across climate models and internal climate variability10,32,33,34,35 and are particularly heterogeneous in space, with a tendency towards wettening in Northern Europe and drying in Southern Europe (Extended Data Fig. 3). However, the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment concluded that evapotranspiration changes were a driver for drying under human-induced climate change in some regions, independently of changes of precipitation18. In the case of the 2022 summer drought event, temperatures in the year leading to the drought were substantially amplified by global warming (Fig. 4b), probably enhancing evaporation3. Changes in daily temperature ranges, which are related to evaporation, appear instead generally small and uncertain across models (Fig. 4c).

a, The change in mean precipitation (P) relative to pre-industrial conditions in 1851–1900 (computed as a ratio) in SON 2021, DJF 2021–2022, MAM 2022 and JJA 2022. The median across Europe (Fig. 1a) of the change derived from 23 CMIP6 climate models is depicted—the information from individual models is synthesised via a box plot that shows the interquartile range and the median across models. The grey lines connect changes across seasons from the same climate model. b, The same as a, but for the change in the average daily temperature (T), computed as a difference. c, The same as a, but for the change in the daily temperature range (Trange).

To quantify the net climate change influence on the drought from such intricate changes in meteorological drivers across space and time, we again conducted soil moisture simulations. Specifically, we quantified how human-induced climate change in seasonal precipitation and temperature affected the 2022 soil moisture by comparing simulated soil moisture under observed weather against simulated soil moisture obtained when removing the human-induced climate change trends in precipitation and temperature (Methods). We find that human-induced climate change has substantially intensified the drought across nearly the entire European region (Fig. 5a; results based on CLM–ERA5 simulations are consistent, see discussion in the final section, Implications and challenges for drought dynamics and risks). Specifically, simulations show that, in 2022, many areas experienced the lowest summer soil moisture since 1960 because of human-induced climate change (Fig. 5a, stippling). That is, in the absence of human-induced climate change, the land area experiencing the lowest soil moisture since 1960 (Fig. 1a) would have been half the size compared with what was observed. The intensification of the drought was largely due to the warming (Fig. 5b) and the associated increase in evaporation. Note that changes in daily temperature ranges had little influence on such temperature-driven drought changes (Extended Data Fig. 4). Conversely, precipitation changes intensified the warming-driven drying over Southern Europe and dampened it elsewhere (Fig. 5c). Notably, the increased precipitation even reversed the warming-driven soil drying around northeastern Poland and Lithuania (Fig. 5a), consistent with the spatial pattern of precipitation changes36 (Extended Data Fig. 3a–d).

a, Anomaly in the JJA 2022 average soil moisture due to human-induced climate change, that is, combined changes in mean precipitation, average daily temperature and daily temperature range, in units of s.d. of the JJA 1960–2021 distribution. b,c, The same as a, but for the individual contribution to the drought from temperature (combined daily average and daily range) changes (b) and precipitation changes (c). The stippling indicates locations where climate change contributions made JJA 2022 average soil moisture the driest relative to observed 1960–2021 summers. Simulations are based on the mHM.

At the continental scale, we identify that ~31% (8–51%, interquartile range based on the trends from different climate models) of Europe’s total soil moisture deficit was caused by human-induced climate change (Fig. 6a, first pair of bar plots). In line with Fig. 5, most of the human-induced climate change effect on the aggregated European soil moisture deficit arose from ongoing warming (Fig. 6a, second pair of bar plots), with opposing contributions from precipitation trends balancing out at the continental scale. The limited regional contribution from precipitation trends implies that the effect of decreasing summertime precipitation is compensated by the increasing precipitation in spring and winter (Fig. 4a), underscoring the importance of considering precipitation trends across multiple seasons to assess climate change impacts on summer soil moisture droughts comprehensively.

a, The first bar shows the anomaly of the European total (Fig. 1a) JJA 2022 average soil moisture relative to 1960–2021 (Methods). The second bar shows the total contribution of human-induced climate change to the JJA 2022 drought. The third and fourth bars show the contributions of human-induced climate change to the drought from temperature (temp.) (combined daily average and daily range) and precipitation (precip.) changes, respectively. The fifth and sixth bar plots show the climate change contributions mediated by weather before (lagged effect) and during (direct effect) the 2022 hydrological year (starting in November 2021), respectively. The contributions show the mean of the hydrological simulations driven by changes from 23 CMIP6 climate models, and the error bars show the interquartile range of the simulations. b, The land area of Europe under JJA average soil moisture anomaly below x (x axis) s.d. of the 1960–2021 distribution (brown line); and the area under drought when assuming no climate change (yellow line) and no temperature trends from climate change (red line) (derived as the median of hydrological simulations driven by changes from 23 CMIP6 climate models), plus the interquartile range from climate models (shading). Simulations are based on the mHM.

Lagged climate change effects and the spatial extent of soil moisture drought

While the soil moisture drought responded to the cumulative effect of past weather, human-induced climate change has shaped weather continuously over the past years. This raises the question of whether part of the climate change contribution to the drought stems from past climate change effects on weather, particularly from warming and precipitation trends preceding the hydrological year of 2022, which in Europe started on 1 November 2021. We therefore decompose the total climate change impact on the drought into a lagged effect due to the climate change impact on weather before 1 November 2021 and a direct effect due to climate change after 1 November 2021 (Fig. 6a, third pair of bar plots and Extended Data Fig. 5a). This breakdown reveals that 41% (37–52%, interquartile range) of the climate change-induced drying of the European-aggregated soil moisture was from lagged effects. At the continental scale, where warming dominates the climate change effect, this implies that climate change-driven effects were already underway before November 2021 through enhancing temperature-driven evaporation and soil drying.

In addition to shaping the temporal dynamics of the drought, we find that, by enhancing the soil moisture deficit over many areas (Fig. 5a), human-induced climate change substantially increased the drought’s spatial extent (Fig. 6b). For instance, climate change expanded the European area experiencing soil moisture anomalies below two s.d. from the average, enlarging it from about 1.03 to 1.64 million square kilometres, that is, climate change contributed to 38% (11–58%, interquartile range) of the spatial extent. Similar to the results of the aggregated water deficit at the continental scale (Fig. 6a), such an effect can be largely explained by temperature trends (Fig. 6b, compare orange and red lines), while precipitation trends33 dominate the uncertainties32.

Drivers and climate change effect on the hydrological drought

In 2022, as is common for many soil moisture droughts, the event transitioned into a hydrological drought, causing a widespread reduction in river discharges (Extended Data Fig. 6 and model evaluation in Extended Data Fig. 7). Simulations indicate that 51% of the European river surface experienced discharge anomalies below one s.d. from average, which was the most extensive event since 1960 (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Precipitation anomalies in spring and summer were the main drivers of the summer drought, contributing to −0.2 s.d. and −0.27 s.d. deviation from the mean discharge on average in Europe, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 8). Similarly to the soil moisture drought, climate change enhanced the hydrological drought strongly (Extended Data Fig. 9), contributing to 19% (9–30%, interquartile range) of the river surface under drought (defined via discharge below one s.d. from the mean). While lagged effects from climate change were less pronounced than for the soil moisture drought, they were still important (Extended Data Fig. 5b).

Implications and challenges for drought dynamics and risks

Combining observations and a range of model simulations, we demonstrated that, via enhancing evaporation, human-induced climate change contributed to 31% (8–51%) of the total European soil water losses of one of the most extreme droughts of the past six decades. The 31% estimate is confirmed by the CLM–ERA5 model setup (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), which also broadly confirms the contributions of meteorological anomalies (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4a–f). Given the uncertainties in modelling soil water dynamics via different hydrological and land-surface models17,18, such a remarkable agreement increases the confidence in the robustness of the results. Furthermore, our findings align with the recent human-induced atmospheric drying across Europe, which is unprecedented in the past 400 years37. Still, we note that more extreme droughts may have occurred in the past in the absence of human-induced climate change38. Our results mean that given the large-scale conditions causing the drought, such as the atmospheric circulation driving rainfall deficits, human-induced warming intensified the drought12. Human-induced climate change may further affect the probability that the large-scale conditions causing the drought occur, but such changes are more challenging to discern9,39. In line with previous studies, these results reflect the impact of climate variability and change on the drought, without accounting for anthropogenic groundwater pumping. While irrigation practices in Europe are substantially weaker compared with regions such as Asia40, our modelling framework may overestimate soil moisture drought severity at the surface in locations with intensive groundwater pumping41.

Despite the agreement between a hydrological and a land-surface model, climate change contributions in attribution studies may depend on methodological choices9 and alternative approaches for creating counterfactuals, each with its own advantages and limitations, exist9,42,43,44. Here, in contrast to nudged simulations that constrain atmospheric circulation, which are typically based on a single Earth system model43,45,46, our approach could account for uncertainties from different climate and hydrological/land-surface models. While using climate models is standard for attribution studies, models may have biases9. The debate on whether climate models underestimate human-induced warming in Europe47,48 means that the impact of human-induced climate change on the drought may be underestimated. Despite known uncertainties in the magnitude of human-induced climate change trends (Fig. 4) and inevitable methodological choices, our findings are consistent with previous research on hydrological trends18,49 and are rooted in fundamental physical principles and thus advance our understanding of long-lasting climate change effects on droughts9. That is, human-induced warming, a robust feature of climate models39, increases evaporation, building up soil water deficits over time.

The fact that a substantial portion of the climate change contribution was mediated by the warming experienced before the hydrological year of 2022 has broad implications for droughts and underscores how climate change-enhanced evaporation silently contributes to an accumulation of soil moisture deficits. One of the implications is that, for a cold–wet year to offset the climate change effects fully, the weather must counterbalance not only the climate change-enhanced evaporation during the ongoing hydrological year but also that of the years before. We ran simulations to assess differences in hydrological and land-surface models, which also reflect differences in the representation of evaporation. The CLM–ERA5 land-surface model setup, which is less accurate than the mHM–E-OBS hydrological model, suggests a smaller lagged effect contribution to the total climate change impact on the total European soil moisture deficit, that is 14% compared with 41% in mHM–E-OBS (Supplementary Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 5c). Such differences may be linked to different representations of low-frequency variability in state-of-the-art hydrological and land-surface models50 and different representations of evaporation, a matter that deserves further investigation as it may severely affect uncertainties in their future drought projections. The analysis of soil moisture memory has a long history28,51, but the impact of the interaction between soil moisture memory and long-term human-induced climate change on droughts has been largely overlooked so far. Underestimating lagged effects would mean incompletely representing the climate change impact on water resources, an issue that may emerge prominently with rising temperatures leading to more pronounced lagged effects. Similarly, common drought indices that integrate water balance over a few months may provide not only incomplete information on the drought dynamics, but also on human-induced climate change effects.

The results underscore that climate change effects on droughts are already underway and, according to future projections18, will probably increase in the future52. Such effects are particularly challenging for Europe, where about 66% of the population relies on groundwater for its water-related needs, and groundwater is overexploited in many cities2,53. The potential for a growth in the drought spatial extents, which can escalate continent-wide aggregated impacts54,55,56,57, is particularly concerning. Spatially compounding, widespread droughts across multiple countries11 may yield greater impacts than localized events, even if they have equivalent continent-wide water deficits. This is due to the threshold behaviour of many impacts, where local impacts increase minimally beyond a minimum water availability, as shown by tree mortality58 and the shutdown of hydro and nuclear plants in 2022 when water in rivers crossed critical levels. Furthermore, through spatially compounding effects11, simultaneous impacts across multiple countries can put high pressure on emergency response actions59 of the European civil protection mechanism, calamity funds, insurance schemes and transnational risk reduction54,60. Our results and the widespread impacts of the summer of 2022 highlight the importance of creating a cost-effective61 pan-European approach to drought risk management2 to improve drought preparedness.

Methods

Data

To conduct hydrological simulations with the mHM13,14,62 and quantify weather anomalies associated with the drought, we used daily precipitation, daily average temperature and the daily range of temperature from the E-OBS dataset (v.25.0e) for the period 1950–2022 (ref. 16). The daily range of temperature was derived from the difference between maximum and minimum daily temperature (in some rare instances, the minimum temperature can exceed the maximum temperature in the E-OBS dataset due to the combination of the interpolation method and the sparse station network63, therefore we set the daily range to zero62). E-OBS data were regridded from the original 0.1° resolution to a 0.125° spatial resolution, which is the resolution required by the hydrological model, using the nearest neighbour approach. To run land-surface model simulations via the CLM19,20, we employed ERA5 reanalyses (CLM–ERA5 setup) as detailed in Supplementary Information.

For the mHM model, to derive the climate change signals in drought drivers, we used monthly means of precipitation, temperature and daily range of temperature (the latter was derived from daily maximum/minimum values) from CMIP6 models containing these variables. While CMIP6 models are routinely used in attribution studies9, employing regional climate models could have allowed for better distilling of local-scale heterogeneity in climate change signals. Here, CMIP6 models were preferred to regional climate models because (1) local-scale details are not expected to be critical for a continental-scale drought influenced by monthly to annual weather and (2) most regional climate models substantially underestimate European warming, potentially distorting extreme event attribution analyses (this primarily occurs because these models do not account for time-evolving aerosols, leading to an underestimation of increased downward shortwave radiation)48. We used the models (r1i1p1f1 for all models unless indicated differently) ACCESS-CM2, ACCESS-ESM1-5 (r10i1p1f1), AWI-CM-1-1-MR, CanESM5 (r10i1p1f1), CMCC-ESM2, CNRM-CM6-1-HR (r1i1p1f2), CNRM-CM6-1 (r1i1p1f2), EC-Earth3, EC-Earth3-Veg-LR, EC-Earth3-Veg, FGOALS-g3, GFDL-CM4, GFDL-ESM4, INM-CM4-8, INM-CM5-0, IPSL-CM6A-LR (r14i1p1f1), MIROC6 (r10i1p1f1), MIROC-ES2L (r10i1p1f2), MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MPI-ESM1-2-LR (r10i1p1f1), MRI-ESM2-0, NorESM2-MM and TaiESM1. Following Schumacher et al.2, we used data from the historical scenario (1851–2014) combined with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways SSP5-8.5 from 2015 onward (note that the historical natural ‘hist-nat’ scenario data are not available up to 2022, but at best up to 2020 for some models, making the use of ‘hist-nat’ not possible for this study). As a first step in the analyses involving climate models, we regridded the data of each climate model to the final grid of E-OBS using the nearest neighbour approach (before, we replaced sea grid points with the nearest land points to avoid mislocations of the land–sea gradient in the warming). Furthermore, in Extended Data Fig. 10, we employed 50 ensemble members of the climate model MIROC6 to provide insights into the contribution of internal climate variability to the uncertainties in precipitation and temperature trends10,32. We followed a similar procedure for CLM simulations as described in Supplementary Information.

Historical hydrological and land-surface simulations

We simulated 2 m soil moisture and river discharge (as well as total water storage anomaly for the model evaluation in Extended Data Fig. 1) at a horizontal resolution of 0.125° × 0.125° employing the mHM, using the E-OBS data introduced above as input climatic forcing (mHM–E-OBS setup). The temperature-based Hargreaves–Samani method22 was used to estimate daily potential evapotranspiration from daily average temperature and range of temperature. This is the most sophisticated method that can be implemented based on E-OBS data. We tested that historical simulations of soil moisture and total water storage anomalies are robust to different formulations of potential evapotranspiration by comparing mHM simulations forced with ERA5 reanalyses21 based on potential evapotranspiration (1) estimated via the Hargreaves–Samani method and (2) readily available from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts21. The model further employs physiographic information such as a digital elevation model, soil texture at various depths, hydrogeological formations and the historical land cover evolution. The mHM model is a grid-based hydrologic model that accounts for dominant hydrologic processes consisting of interception, root-zone soil moisture dynamics, evapotranspiration, run-off generation, groundwater recharge and discharge routing through the surface river network. The model uses soil layering of SoilGrids64, which provides harmonized soil characteristics globally up to the depths of 2 m. Accordingly, we analysed 2 m soil moisture52,65,66, which is relevant for plant root zones, hydrological processes, drought resilience and long-term drought effects. For example, many crops and vegetation types have root systems that extend to depths up to or around 2 m (ref. 67). The model mHM uses a state-of-the-art multi-scale parameter regionalization technique to derive a seamless set of model parameters based on hyper-resolution land-surface properties and upscaling approaches13,68. This particular scaling technique makes this model applicable across scales. We disregarded the first 10 years of simulations (1950–1959) in line with the typical spin-up time required by this model69. For the full model setup and configuration, we refer to the data repository in ref. 70. Details on the simulations based on the CLM land-surface model (CLM–ERA5 setup) are provided in the Supplementary Information, which also includes information on supplemental mHM simulations (presented in Supplementary Information only) forced with ERA5 reanalysis (mHM–ERA5 setup).

We derived river discharge based on the mHM model, which uses a multi-scale routing model13,15. Based on the digital elevation model of the domain of interest and derived properties called flow direction and accumulation maps, the multi-scale routing mode was used to set up the routing network automatically at the model resolution. We considered only rivers with a basin area larger than 1,000 km2. Note that for the river discharge, we inspected the average of the standardized anomaly in river discharge across Europe (Extended Data Fig. 6b), rather than the anomaly in the aggregated discharge as similarly done for soil moisture (Fig. 1b). This was done to avoid giving too much weight to the largest rivers. Accordingly, we did not present the counterpart of Fig. 6a for river discharge. Computing the absolute river surface under drought is unfeasible as it would require very high-resolution river network data; therefore, we quantified the drought spatial extent only in percentage, as the total area of grid points associated with dry river conditions divided by the total area of grid points associated with rivers. For all hydrological simulations, we restricted the output only to areas unaffected by missing E-OBS data.

Evaluation of soil moisture and river discharge simulations

The mHM model has been thoroughly evaluated and tested for soil moisture, evapotranspiration, run-off and total water storage anomaly across Europe71,72,73,74. Accordingly, the model is currently the core of the German Drought Monitor75 and one of the Copernicus Climate Change Service models for seasonal predictions of soil moisture at a global scale. We further tested the performance of the mHM model against monthly satellite data of terrestrial total water storage (TWS) anomaly from GRACE76,77 (note that no satellite observations exist for 2 m soil moisture and TWS is its closest observed proxy). We employed correlations, inspected the spatial pattern of the 2022 drought and assessed biases in TWS anomalies aggregated over large regions (Extended Data Fig. 1). For the evaluation, we disregarded months that are not available in the GRACE dataset from the simulations and regridded simulated TWS simulations to the coarse resolution of GRACE. We evaluated the simulations based on the CLM–ERA5 setup in the same way (Supplementary Fig. 6).

For mHM simulations, we further evaluated the river discharge simulations against observed station data from the Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC, https://www.bafg.de/GRDC), using similar metrics employed for TWS evaluation and the Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient78 (Extended Data Fig. 7). For the evaluation, strongly human-modified basins were excluded. GRDC stations were selected by first matching them with the nearest mHM grid cells and then retaining stations and grid cells whose catchment areas differ by less than 10%; furthermore, we use stations with data in at least 20 years within the period 1960–2022. For the evaluation, for each station, we first disregarded days unavailable in the GRDC dataset from the simulations and then used daily data during the whole year or JJA averages for both GRDC and simulations.

Counterfactual experiments to quantify meteorological contributions

To quantify the contribution of seasonal weather anomalies to the 2022 summer soil moisture drought (Fig. 3), we conducted hydrological (mHM–E-OBS) and land-surface (CLM–ERA5) simulations23. In the following, we provide information regarding the mMH–E-OBS simulations. An analogous approach was employed for CLM–ERA5 simulations, though tailored to accommodate the different variables considered in the CLM–ERA5 setup (Supplementary Information). To quantify the contribution of precipitation anomaly during DJF 2021–2022, we computed the difference between the average soil moisture in JJA 2022 (SMJJA) in two simulations: (1) the baseline simulation driven by observed daily precipitation, daily average temperature and daily temperature range and (2) a simulation where we maintained observed daily precipitation and temperature but adjusted the field of daily precipitation during DJF 2021–2022 to match its climatology. We adjusted the field of precipitation daily time series during DJF 2021–2022 with a multiplicative factor (the inverse of the field shown in Fig. 2a) equal to the ratio of the DJF climatological mean precipitation (1981–2010) to the mean precipitation during DJF 2021–2022 (if the ratio is not defined due to zero mean precipitation during DJF 2021–2022, the adjusted field is set to the value of the climatology). The contribution of precipitation anomalies in other seasons and anomalies of average temperature and daily temperature range were assessed similarly. However, for the contribution of average temperature, we adjusted the field of daily average temperature during, for example, DJF 2021–2022, with an additive (rather than multiplicative) factor (the opposite of the field shown in Fig. 2d) equal to the difference between the DJF climatological mean daily average temperature (1981–2010) and the mean daily average during DJF 2021–2022. To assess the combined contribution of anomalies of average temperature and daily temperature range (referred to as temperature contribution in the main text; Fig. 3d–f), we adjusted both variables in the season of interest in the same simulation.

Counterfactual experiments for human-induced climate change

We take a ‘storyline approach’ for climate change attribution, that is, given the meteorological conditions driving the drought, we quantify the human-induced climate change effect on the drought and the contribution of changes in drought drivers to the overall effect12. Note that this differs from a ‘probabilistic approach’, which focuses on the human-induced climate change effect on the probability of events similar to the event in question79. We quantify the total contribution of climate change-driven seasonal precipitation and temperature changes to the 2022 summer drought (Fig. 5a) via computing the difference between SMJJA from (1) the baseline simulation and (2) a simulation driven by daily precipitation and temperature from which seasonal-dependent human-induced climate change trends were removed.

For (2), removing the observed trend would not suffice because the observed trend arises from a combination of human-induced climate change and an often relatively large trend from internal climate variability10,27,48. Similarly to observations, trends in individual climate model simulations arise from human-induced climate change and spurious trends from internal climate variability. However, here, the multi-model mean can allow for isolating human-induced climate change by averaging out spurious trends due to internal climate variability across simulations10,27,80. Thus, building on previous work44,80, including typical approaches employed in climate projections18,36, we removed the trends extracted from multiple climate models from observed time series, whereby the multi-model mean is representative of the human-induced climate change trend (for mHM–E-OBS simulations, the spread across models provides information on uncertainties related to model differences and internal climate variability44). In the following, we provide information regarding the mMH–E-OBS simulations, while an analogous approach is employed for CLM–ERA5 simulations as described in the Supplementary Information. We ran a simulation driven by daily precipitation and temperature from which—via what is sometimes referred to as a delta approach44,80,81,82—the seasonal- and year-dependent trends derived from individual CMIP6 models were removed. For each season and year Y between 1960 and 2022, we adjusted the field of precipitation daily time series using a multiplicative factor field equal to the ratio of seasonal mean precipitation in the pre-industrial period (1851–1900) to the seasonal mean precipitation over a 15 year window centred on the year Y. The daily average temperature and daily temperature range were adjusted similarly, but for daily average temperature, we adjusted the field by using an additive factor field equal to the difference between seasonal mean temperature in the pre-industrial period to the seasonal mean temperature over a 15 year window centred on the year Y. Using a window length longer than 15 years yields similar multi-model mean results in all factors. The factor fields (their inverse for precipitation and daily average temperature, and their opposite for daily average temperature) are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3 for the last four considered seasons (their median across Europe is shown in Fig. 4 for summary proposes only).

To disentangle the individual contribution of trends in precipitation (Fig. 5c), we computed the difference between SMJJA from the baseline simulation and a simulation where we removed CMIP6 model trends only for precipitation. To assess the total contribution of trends in average temperature and the daily temperature range (referred to as temperature contribution in the main text; Fig. 5b), we removed CMIP6 model trends from both variables. The contribution of daily temperature range trends (Extended Data Fig. 4) was quantified as the difference between the total contribution of temperature trends and the contribution of daily average temperature trends.

In Fig. 6a and Extended Data Fig. 5, we decompose the total climate change contribution into two parts: the climate change contribution mediated by weather (1) during the 2022 hydrological year (starting in November 2021), that is, a direct effect, and (2) before the 2022 hydrological year, that is, a lagged effect. (1) The climate change contribution mediated by weather during the 2022 hydrological year was quantified as the difference between SMJJA from the baseline simulation and a simulation driven by observed daily precipitation and temperature up to 1 November 2021 and detrended (removing CMIP6 model trends as described above) afterwards. (2) The contribution mediated by weather before the 2022 hydrological year was then computed as the difference between the total climate change contribution and the contribution mediated by weather during the 2022 hydrological year.

Our approach for creating counterfactuals, combined with the computationally efficient yet performant hydrological mHM model, allows for integrating climate change signals from 23 climate models and assess uncertainties on attribution statements of soil moisture and hydrological droughts at the European scale based on the mHM–E-OBS setup (Fig. 6). To this end, we ran hydrological simulations individually based on multiplicative/additive factors from individual CMIP6 models. However, to optimize computational efficiency, we ran a single common simulation up to 2005 based on the multi-model mean factors. We tested for a single climate model with strong trends (EC-Earth3-Veg) that this choice does not affect the attribution statements. In particular, the difference between the climate change driven change in SMJJA based on multiplicative/additive factors from (1) the EC-Earth3-Veg model for the period 1960–2022 and (2) the multi-model mean up to 2005 and the EC-Earth3-Veg model thereafter, ranges (5–95th percentile over Europe) from −0.005 × 10−3σ1960−2021 to 3 × 10−3σ1960−2021, where σ1960−2021 is the standard deviation of the distribution of the 1960–2021 JJA average soil moisture, while the European mean of the absolute difference is 0.9 × 10−3σ1960−2021. Finally, note that structural model differences have a relevant contribution to the resulting uncertainties33. Accordingly, the overall uncertainty in precipitation and average temperature trends illustrated by the interquartile range in Fig. 4a,b is, apart from September–November (SON), larger than the uncertainty due to internal climate variability (Extended Data Fig. 10).

On the basis of the mHM–E-OBS setup, we tested that running simulations for 1960–2022, and therefore neglecting trends before 1960, is justified as trends up to 1990 have virtually no impact on the 2022 drought. Finally, we note that, for studying a continental drought developing over multiple years, we considered forced changes in mean seasonal conditions of drought drivers as representative of changes during anomalous seasons. This approach for removing climate change trends may provide a conservative estimate of the climate change effect if extremely dry seasons, such as the summer of 2022, warm and dry more than average summers with climate change. However, this choice is consistent with limited variability changes compared with mean changes at the monthly scale in some CMIP5 models83 and with the fact that we did not find evidence for such an effect in the CMIP6 model ensemble (similarly, no clear evidence was found for daily temperature extremes84). That is, for the 2022 summer, we found that the European-averaged CMIP6-based multi-model mean change in mean precipitation/temperature is about equal to the multi-model mean change of summers that are ranked as dry as the 2022 summer on a scale from one to five in terms of aggregated precipitation over Europe land masses. Nudged simulations that constrain atmospheric circulation43,45,46 could examine this choice further.

Aggregated statistics

All the statistics, such as mean, median and percentage of land masses, were weighted by grid point surfaces, employing the R packages wCorr85 and spatstat86. The anomaly in the European total soil moisture (Figs. 1b and 6a) was computed as the spatially weighted sum of the yearly anomaly in the volume of the JJA average soil moisture relative to the 1960–2021 JJA average. In the text, summary statistics concerning CMIP6 models are calculated as the multi-model mean of the final values of the statistics associated with different models. As an exception, the change in the spatial extent of soil moisture and hydrological droughts is based on the multi-model median (as depicted in Fig. 6b) due to the skewed distribution of the spatial extents for extreme droughts. For similar reasons, Extended Data Fig. 5a,b displays the multi-model median, and the statistic related to the land area that would have experienced a record-breaking soil moisture drought in the absence of climate change is based on the counterfactual soil moisture spatial map derived, in a first step, as the multi-model mean.

Data availability

E-OBS daily data (v.25.0e) at resolution 0.1° over Europe lands are available at https://www.ecad.eu/download/ensembles/download.php. CMIP6 data can be retrieved at https://esgf-data.dkrz.de/projects/esgf-dkrz/. GRACE data are available at https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/TELLUS_GRAC_L3_CSR_RL06_LND_v04. The mHM model routed run-off is available from the UFZ data portal70. ERA5 reanalyses are available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels.

Code availability

All custom codes are direct implementations of standard methods and techniques, described in detail in Methods. All maps were obtained by using the oce R package87. The mHM model is available under the repository https://git.ufz.de/mhm/mhm. Data pre-processing, including the computation of the multiplicative and additive factors, was carried out with standard Climate Data Operators functions88.

References

Toreti, A. et al. Drought in Europe August 2022 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2022).

Schumacher, D. L. et al. Detecting the human fingerprint in the summer 2022 Western–Central European soil drought. Earth Syst. Dyn. 15, 131–154 (2024).

Faranda, D., Pascale, S. & Bulut, B. Persistent anticyclonic conditions and climate change exacerbated the exceptional 2022 European-Mediterranean drought. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 034030 (2023).

Bonaldo, D. et al. The summer 2022 drought: a taste of future climate for the Po Valley (Italy)? Reg. Environ. Change 23, 1 (2023).

van der Woude, A. M. et al. Temperature extremes of 2022 reduced carbon uptake by forests in Europe. Nat. Commun. 14, 6218 (2023).

Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2022 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

Hogan, M. & Nasralla, S. Low water hampers Rhine River shipping in Germany. Reuters https://www.reuters.com/business/low-water-hampers-rhine-river-shipping-germany-2023-06-19/ (19 June 2023).

Kollewe, J. EDF cuts output at nuclear power plants as French rivers get too warm. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/aug/03/edf-to-reduce-nuclear-power-output-as-french-river-temperatures-rise (3 August 2022).

Stott, P. A. et al. Attribution of extreme weather and climate-related events. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 7, 23–41 (2016).

Deser, C., Knutti, R., Solomon, S. & Phillips, A. S. Communication of the role of natural variability in future North American climate. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 775–779 (2012).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Shepherd, T. G. A common framework for approaches to extreme event attribution. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2, 28–38 (2016).

Samaniego, L., Kumar, R. & Attinger, S. Multiscale parameter regionalization of a grid-based hydrologic model at the mesoscale. Water Resour. Res. 46, W05523 (2010).

Kumar, R., Samaniego, L. & Attinger, S. Implications of distributed hydrologic model parameterization on water fluxes at multiple scales and locations. Water Resour. Res. 49, 360–379 (2013).

Thober, S. et al. The multiscale routing model mRM v1.0: simple river routing at resolutions from 1 to 50 km. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 2501–2521 (2019).

Cornes, R. C., van der Schrier, G., van den Besselaar, E. J. & Jones, P. D. An ensemble version of the E-OBS temperature and precipitation data sets. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 9391–9409 (2018).

Caretta, M. A. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) 551–712 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1513–1766 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Lawrence, P. J. et al. Simulating the biogeochemical and biogeophysical impacts of transient land cover change and wood harvest in the Community Climate System Model (CCSM4) from 1850 to 2100. J. Clim. 25, 3071–3095 (2012).

Oleson, K. W. & Lawrence, D. M. Technical Description of Version 4.5 of the Community Land Model (CLM). NCAR Technical Note NCAR/TN-503+STR http://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/cesm1.2/clm/CLM45_Tech_Note.pdf (CESM, 2013).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Hargreaves, G. H. & Samani, Z. A. Reference crop evapotranspiration from temperature. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1, 96–99 (1985).

Bastos, A. et al. Direct and seasonal legacy effects of the 2018 heat wave and drought on European ecosystem productivity. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2724 (2020).

Ionita, M., Nagavciuc, V., Kumar, R. & Rakovec, O. On the curious case of the recent decade, mid-spring precipitation deficit in Central Europe. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 49 (2020).

Moravec, V. et al. Europe under multi-year droughts: how severe was the 2014–2018 drought period? Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 034062 (2021).

van der Wiel, K., Batelaan, T. J. & Wanders, N. Large increases of multi-year droughts in North-Western Europe in a warmer climate. Clim. Dyn. 60, 1781–1800 (2023).

Bevacqua, E. et al. Advancing research on compound weather and climate events via large ensemble model simulations. Nat. Commun. 14, 2145 (2023).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Soil moisture memory in AGCM simulations: analysis of Global Land–Atmosphere Coupling Experiment (GLACE) data. J. Hydrometeorol. 7, 1090–1112 (2006).

McCabe, G. J. & Wolock, D. M. Independent effects of temperature and precipitation on modeled runoff in the conterminous United States. Water Resour. Res. 47, W11522 (2011).

Manning, C. et al. Soil moisture drought in Europe: a compound event of precipitation and potential evapotranspiration on multiple time scales. J. Hydrometeorol. 19, 1255–1271 (2018).

Rakovec, O. et al. The 2018–2020 multi-year drought sets a new benchmark in Europe. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002394 (2022).

Bevacqua, E., Zappa, G., Lehner, F. & Zscheischler, J. Precipitation trends determine future occurrences of compound hot–dry events. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 350–355 (2022).

Vogel, M. M., Zscheischler, J. & Seneviratne, S. I. Varying soil moisture–atmosphere feedbacks explain divergent temperature extremes and precipitation projections in Central Europe. Earth Syst. Dynam. 9, 1107–1125 (2018).

Bevacqua, E., Zappa, G. & Shepherd, T. G. Shorter cyclone clusters modulate changes in European wintertime precipitation extremes. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 124005 (2020).

Maraun, D. When will trends in European mean and heavy daily precipitation emerge? Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 014004 (2013).

Lee, J.-Y. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 553–672 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Treydte, K. et al. Recent human-induced atmospheric drying across Europe unprecedented in the last 400 years. Nat. Geosci. 17, 58–65 (2023).

Hanel, M. et al. Revisiting the recent European droughts from a long-term perspective. Sci. Rep. 8, 9499 (2018).

Shepherd, T. G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nat. Geosci. 7, 703–708 (2014).

FAO Statistical Yearbook 2017: World Food and Agriculture (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2017).

Wada, Y. et al. Global depletion of groundwater resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L20402 (2010).

Mengel, M., Treu, S., Lange, S. & Frieler, K. ATTRICI v1. 1—counterfactual climate for impact attribution. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 5269–5284 (2021).

van Garderen, L., Feser, F. & Shepherd, T. G. A methodology for attributing the role of climate change in extreme events: a global spectrally nudged storyline. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 171–186 (2021).

Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M. et al. The footprint of human-induced climate change on heat-related deaths in the summer of 2022 in Switzerland. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 074037 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Storyline attribution of human influence on a record-breaking spatially compounding flood-heat event. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi2714 (2023).

Meredith, E. P., Semenov, V. A., Maraun, D., Park, W. & Chernokulsky, A. V. Crucial role of Black Sea warming in amplifying the 2012 Krymsk precipitation extreme. Nat. Geosci. 8, 615–619 (2015).

Vautard, R. et al. Heat extremes in Western Europe increasing faster than simulated due to atmospheric circulation trends. Nat. Commun. 14, 6803 (2023).

Schumacher, D. L. et al. Exacerbated summer European warming not captured by climate models neglecting long-term aerosol changes. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 182 (2024).

Gudmundsson, L. et al. Globally observed trends in mean and extreme river flow attributed to climate change. Science 371, 1159–1162 (2021).

Humphrey, V. et al. Sensitivity of atmospheric CO2 growth rate to observed changes in terrestrial water storage. Nature 560, 628–631 (2018).

Delworth, T. L. & Manabe, S. The influence of potential evaporation on the variabilities of simulated soil wetness and climate. J. Clim. 1, 523–547 (1988).

Samaniego, L. et al. Anthropogenic warming exacerbates European soil moisture droughts. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1117–1121 (2018).

The problems of water stress. European Environment Agency https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/92-9167-025-1/page003.html (2023).

Jongman, B. et al. Increasing stress on disaster-risk finance due to large floods. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 264–268 (2014).

Bevacqua, E. et al. Larger spatial footprint of wintertime total precipitation extremes in a warmer climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091990 (2021).

Brunner, M. I., Swain, D. L., Gilleland, E. & Wood, A. W. Increasing importance of temperature as a contributor to the spatial extent of streamflow drought. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 024038 (2021).

Fang, B., Bevacqua, E., Rakovec, O. & Zscheischler, J. An increase in the spatial extent of European floods over the last 70 years. EGUsphere 2024, 1–26 (2024).

Allen, C. D. et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 259, 660–684 (2010).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Juang, C. S., Williams, A. P., Kolden, C. A. & Westerling, A. L. Increasing synchronous fire danger in forests of the western United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091377 (2021).

van den Hurk, B. J. et al. Consideration of compound drivers and impacts in the disaster risk reduction cycle. iScience 26, 106030 (2023).

Blauhut, V. et al. Lessons from the 2018–2019 European droughts: a collective need for unifying drought risk management. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 2201–2217 (2022).

Samaniego, L. et al. mhm-ufz/mhm: v5.13.1. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8279545 (2023).

Known issues in E-OBS. Copernicus https://surfobs.climate.copernicus.eu/userguidance/known_issues_eobs.php (2023).

Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids250m: global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12, e0169748 (2017).

Vidal, J.-P. et al. Multilevel and multiscale drought reanalysis over France with the Safran-Isba-Modcou hydrometeorological suite. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 459–478 (2010).

Andreadis, K. M. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Trends in 20th century drought over the continental United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L10403 (2006).

Jackson, R. B. et al. A global analysis of root distributions for terrestrial biomes. Oecologia 108, 389–411 (1996).

Samaniego, L. et al. Toward seamless hydrologic predictions across spatial scales. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 4323–4346 (2017).

Samaniego, L., Kumar, R. & Zink, M. Implications of parameter uncertainty on soil moisture drought analysis in Germany. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 47–68 (2013).

Rakovec, O., Kumar, R. & Samaniego, L. Mesoscale hydrologic model based historical streamflow simulation over Europe at 1/8 degree. UFZ https://www.ufz.de/record/dmp/archive/14403/en/ (2023).

Rakovec, O. et al. Multiscale and multivariate evaluation of water fluxes and states over European river basins. J. Hydrometeorol. 17, 287–307 (2016).

Samaniego, L. et al. Hydrological forecasts and projections for improved decision-making in the water sector in Europe. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 2451–2471 (2019).

Kumar, R. et al. Strong hydroclimatic controls on vulnerability to subsurface nitrate contamination across Europe. Nat. Commun. 11, 6302 (2020).

Pohl, F. et al. Long-term daily hydrometeorological drought indices, soil moisture, and evapotranspiration for ICOS sites. Sci. Data 10, 281 (2023).

Zink, M. et al. The German drought monitor. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 074002 (2016).

Landerer, F. W. & Swenson, S. Accuracy of scaled grace terrestrial water storage estimates. Water Resourc. Res. 48, W04531 (2012).

Landerer, F. CSR TELLUS GRACE level-3 monthly land water-equivalent-thickness surface mass anomaly release 6.0 version 04. PODAAC https://doi.org/10.5067/TELND-3AC64 (2021).

Jiang, S., Bevacqua, E. & Zscheischler, J. River flooding mechanisms and their changes in Europe revealed by explainable machine learning. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 6339–6359 (2022).

Stott, P. A. & Christidis, N. Operational attribution of weather and climate extremes: what next? Environ. Res. Clim. 2, 013001 (2023).

Mitchell, D. et al. Half a degree additional warming, prognosis and projected impacts (HAPPI): background and experimental design. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 571–583 (2017).

Mishra, A. N. et al. Climate change amplified the 2009 extreme landslide event in Austria. Clim. Change 176, 124 (2023).

Maraun, D. et al. A severe landslide event in the Alpine foreland under possible future climate and land-use changes. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 87 (2022).

van der Wiel, K. & Bintanja, R. Contribution of climatic changes in mean and variability to monthly temperature and precipitation extremes. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 1 (2021).

Jézéquel, A. et al. Conditional and residual trends of singular hot days in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 064018 (2020).

Emad, A. & Bailey, P. wCorr: weighted correlations. R package version 1.9.1 (2017).

Baddeley, A. J. et al. Spatstat: an R package for analyzing spatial point pattens. J. Stat. Soft. 12, 1–42 (2005).

Kelley, D., Richards, C. & Layton, C. oce: analysis of oceanographic data. R package version 1.7-10 (2022).

Schulzweida, U. CDO user guide. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10020800 (2023).

Acknowledgements

E.B. received funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) via the Emmy Noether Programme (grant ID 524780515). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101003469. J.Z. acknowledges the Helmholtz Initiative and Networking Fund (Young Investigator Group COMPOUNDX, grant agreement VH-NG-1537). O.R. acknowledges the Czech Science Foundation grant 23-08056S. We acknowledge the E-OBS dataset from the EU-FP6 project UERRA and the Copernicus Climate Change Service, and the data providers in the ECA&D project (https://www.ecad.eu). The authors acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme, which, through its Working Group on Coupled Modelling, coordinated and promoted CMIP6, and the authors thank the climate modelling groups for producing and making available their model output, the Earth System Grid Federation for archiving the data and providing access, and the multiple funding agencies who support CMIP and the Earth System Grid Federation. The mHM simulations were computed at the High-Performance Computing Cluster EVE, a joint effort of both the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research–UFZ and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig. We thank the administration and support staff of EVE, that is, B. Langenberg, C. Krause, T. Harzendorf, G. Schramm and L. Schurack from the UFZ.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung GmbH - UFZ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B. analysed the model outputs, wrote the manuscript with contributions from O.R. and D.L.S. and designed the study with contributions from J.Z. E.B. prepared the CMIP6 multiplicative/additive factors and carried out mHM simulations building on code from O.R., who also carried out the factual mHM simulations and prepared river discharge and TWS observational data for the evaluation of mHM and CLM. D.L.S. carried out the CLM simulations based on CMIP6 multiplicative/additive factors derived by adapting the code from E.B. R.K. provided conceptual input during the work development. All authors (E.B., O.R., D.L.S., R.K., S.T., L.S., S.I.S. and J.Z.) discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Thomas Richardson, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Evaluation of the mHM model (forced with E-OBS).

a-d, Simulated (mHM) against observed (GRACE) regionally averaged total water storage anomaly (TWS) during 2002-2022 for IPCC regions, that is (a) Northern Europe, (b) Central Europe, and (c) Southern Europe/the Mediterranean (these three regions are displayed in panel h), and (d) Europe (box in Fig. 1a). Orange small and purple large dots show monthly and June–August (JJA) average values, respectively (the circled large purple dot indicates the year 2022). e, Grid-point correlation between simulated and observed monthly average values of total water storage anomaly. f, The same as (e), but for JJA average values. g-h, The ranking of the (g) observed and (h) simulated average values of total water storage during JJA 2022 relative to JJA values of 2002-2022.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Human-induced change in precipitation and temperature for the four seasons preceding the 2022 drought.

a-d, Multimodel mean change of mean precipitation in (a) September–November (SON) 2021, (b) December 2021–February 2022 (DJF 2021–2022), (c) March–May (MAM) 2022, and (d) June–August (JJA) 2022 relative to preindustrial conditions in 1851-1900 (computed as a ratio; > 1 indicates higher precipitation). e-h, The same as (a-d), but for change in average daily temperature (computed as a difference; > 0 indicates warming). i-l, The same as (a-d), but for change in the daily temperature range (> 1 indicates an increase in the daily temperature range).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Contribution of climate change-driven trends in the daily temperature range to the June–August (JJA) 2022 soil moisture drought.

Anomaly in the JJA 2022 average soil moisture due to changes in daily temperature range, in units of s.d. of the JJA 1960-2021 distribution. The absence of stippling indicates that there are no locations where climate change-driven trends in the daily temperature range made JJA 2022 the driest relative to 1960-2021. Simulations are based on the mesoscale Hydrological Model (mHM).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Contribution of climate change lagged effect to the soil moisture and hydrological droughts.

a, Fraction of the climate change contribution to the soil moisture drought from lagged effects, computed as the multimodel median of the ratio of the anomaly in the June–August 2022 average soil moisture due to the climate change effect mediated by weather before the 2022 hydrological year (starting in November 2021) to the total climate change effect. The number on the top-right shows the spatially-weighted average across Europe (box in Fig. 1a). Magenta indicates locations where the total climate change effect (based on the multimodel mean as in Fig. 5a) is positive. Simulations are based on the mesoscale Hydrological Model (mHM). b, The same as (a), but for river discharge. c, Similar to (a), but for soil moisture derived from CLM–ERA5 simulations – this is based on a single simulation (rather than on the multimodel median of multiple simulation as in panel a) based on combined climate change factors derived from the multiple CMIP6 models; the setup is described in the Supplementary Information (section 2)).

Extended Data Fig. 6 The 2022 European hydrological drought.

The same as Fig. 1, but for river discharge and with the exception that (b) shows the average of the standardised anomaly in river discharge across Europe, and (c) shows the spatial extent of the river surface in Europe (box in panel a) that experienced discharge anomalies below one s.d. from average, expressed in percentage (Methods).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Evaluation of the mHM model (forced with E-OBS).

a-d, Simulated (mHM) against observed (GRDC) regionally averaged rank (from 0 indicating dryness, to 1 indicating wetness) of the June–August (JJA) average river discharge values relative to the period of data availability in GRDC for IPCC regions, that is (a) Northern Europe, (b) Central Europe, and (c) Southern Europe/the Mediterranean (these three regions are displayed in Extended Data Fig. 1h), and (d) Europe (box in Fig. 1a). The circled large dot indicates the year 2022 (note that 2020-2022 data is not available for Southern Europe/Mediterranean after processing the GRDC stations). e, Grid-point correlation between simulated and observed daily river discharge. f, The same as (e), but for JJA average values. g, Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency coefficient computed based on simulated and observed daily river discharge (NSE has values ranging from negative infinite to 1.0, with values above 0.5 generally deemed satisfactory for discharge simulations78). h, The same as (g), but for JJA average values. i-k, The ranking of the (i) observed and (j) simulated average values of river discharge during JJA 2022 relative to the period of data availability in GRDC, and (k) the scatterplot of such ranking across stations. Note that the data availability period in GRDC varies depending on the station.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Contribution of weather anomalies to the June–August 2022 hydrological drought.

a-f, The same as Fig. 3a–f, but for river discharge instead of soil moisture.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Contribution of climate change to the June–August 2022 hydrological drought.

a-c, The same as Fig. 5a-c, but for river discharge instead of soil moisture.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Uncertainties due to internal climate variability in precipitation and temperature changes for the four seasons preceding the 2022 drought.

a,b, The same as Fig. 4a,b, but based on fifty ensemble members of the climate model MIROC6. Boxplots show the interquartile range and the median across the ensemble members.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary text, Methods, Figs. 1–8 and References.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bevacqua, E., Rakovec, O., Schumacher, D.L. et al. Direct and lagged climate change effects intensified the 2022 European drought. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1100–1107 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01559-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01559-2

This article is cited by

-

Effect of rainfall variability and temporal resolution on rainwater harvesting tank sizing in a case study from Jordan and Germany

Discover Water (2026)

-

Growing human-induced climate change fingerprint in regional weekly fire extremes

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Navigating drought

Nature Geoscience (2025)

-

Atmospheric drought indices in future projections

Nature Water (2025)

-

Hysteresis and reversibility of agroecological droughts in response to carbon dioxide removal

Nature Water (2025)