Abstract

Metastases arise from a multistep process during which tumour cells face several microenvironmental mechanical challenges, which influence metastatic success. However, how circulating tumour cells (CTCs) adapt their mechanics to such microenvironments is not fully understood. Here we report that the deformability of CTCs affects their haematogenous dissemination and identify mechanical phenotypes that favour metastatic extravasation. Combining intravital microscopy with CTC-mimicking elastic beads, mechanical tuning in tumour lines and profiling of tumour-patient-derived cells, we demonstrate that the inherent mechanical properties of circulating objects dictate their ability to enter constraining vessels. We identify cellular viscosity as a rheostat of CTC circulation and arrest, and show that cellular viscosity is crucial for efficient extravasation. Moreover, we find that mechanical properties that favour extravasation and subsequent metastatic outgrowth can be opposite. Altogether, our results establish CTC viscosity as a key biomechanical parameter that shapes several steps of metastasis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the article and Supplementary Information. Original microscopy and imaging files are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Steeg, P. S. Targeting metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 201–218 (2016).

Follain, G. et al. Fluids and their mechanics in tumour transit: shaping metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 107–124 (2020).

Stylianopoulos, T. et al. Causes, consequences, and remedies for growth-induced solid stress in murine and human tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15101–15108 (2012).

Regmi, S., Fu, A. & Luo, K. Q. High shear stresses under exercise condition destroy circulating tumor cells in a microfluidic system. Sci. Rep. 7, 39975 (2017).

Wirtz, D., Konstantopoulos, K. & Searson, P. C. The physics of cancer: the role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 512–522 (2011).

Matthews, H. K. et al. Oncogenic signaling alters cell shape and mechanics to facilitate cell division under confinement. Dev. Cell 52, 563–573.e3 (2020).

Moose, D. L. et al. Cancer cells resist mechanical destruction in circulation via rhoa/actomyosin-dependent mechano-adaptation. Cell Rep. 30, 3864–3874.e6 (2020).

Guck, J. et al. Optical deformability as an inherent cell marker for testing malignant transformation and metastatic competence. Biophys. J. 88, 3689–3698 (2005).

Swaminathan, V. et al. Mechanical stiffness grades metastatic potential in patient tumor cells and in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 71, 5075–5080 (2011).

Alibert, C., Goud, B. & Manneville, J.-B. Are cancer cells really softer than normal cells?. Biol Cell 109, 167–189 (2017).

Gensbittel, V. et al. Mechanical adaptability of tumor cells in metastasis. Dev. Cell 56, 164–179 (2021).

Gassmann, P., Hemping-Bovenkerk, A., Mees, S. T. & Haier, J. Metastatic tumor cell arrest in the liver-lumen occlusion and specific adhesion are not exclusive. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 24, 851–858 (2009).

Osmani, N. et al. Metastatic tumor cells exploit their adhesion repertoire to counteract shear forces during intravascular arrest. Cell Rep. 28, 2491–2500.e5 (2019).

Kienast, Y. et al. Real-time imaging reveals the single steps of brain metastasis formation. Nat. Med. 16, 116–122 (2010).

Follain, G. et al. Hemodynamic forces tune the arrest, adhesion, and extravasation of circulating tumor cells. Dev. Cell 45, 33–52.e12 (2018).

Paul, C. D. et al. Tissue architectural cues drive organ targeting of tumor cells in zebrafish. Cell Syst. 9, 187–206.e16 (2019).

Tietze, S. et al. Spheroid culture of mesenchymal stromal cells results in morphorheological properties appropriate for improved microcirculation. Adv. Sci. 6, 1802104 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Efficient extravasation of tumor-repopulating cells depends on cell deformability. Sci. Rep. 6, 19304 (2016).

Cao, X. et al. A chemomechanical model for nuclear morphology and stresses during cell transendothelial migration. Biophys. J. 111, 1541–1552 (2016).

Roberts, A. B. et al. Tumor cell nuclei soften during transendothelial migration. J. Biomech. 121, 110400 (2021).

Allen, T. A. et al. Circulating tumor cells exit circulation while maintaining multicellularity, augmenting metastatic potential. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs231563 (2019).

Karreman, M. A. et al. Active remodeling of capillary endothelium via cancer cell-derived MMP9 promotes metastatic brain colonization. Cancer Res. 83, 1299–1314 (2023).

Headley, M. B. et al. Visualization of immediate immune responses to pioneer metastatic cells in the lung. Nature 531, 513–517 (2016).

Girardo, S. et al. Standardized microgel beads as elastic cell mechanical probes. J. Mater. Chem. B 6, 6245–6261 (2018).

Träber, N. et al. Polyacrylamide bead sensors for in vivo quantification of cell-scale stress in zebrafish development. Sci. Rep. 9, 17031 (2019).

Guo, M. et al. Probing the stochastic, motor-driven properties of the cytoplasm using force spectrum microscopy. Cell 158, 822–832 (2014).

Girard, C. A. et al. A feed-forward mechanosignaling loop confers resistance to therapies targeting the MAPK pathway in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Cancer Res. 80, 1927–1941 (2020).

Grillet, F. et al. Circulating tumour cells from patients with colorectal cancer have cancer stem cell hallmarks in ex vivo culture. Gut 66, 1802–1810 (2017).

Dessard, M., Manneville, J.-B. & Berret, J.-F. Cytoplasmic viscosity is a potential biomarker for metastatic breast cancer cells. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 1727–1738 (2024).

Follain, G. et al. Impairing flow-mediated endothelial remodeling reduces extravasation of tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 11, 13144 (2021).

Peralta, M. et al. Endothelial calcium firing mediates the extravasation of metastatic tumor cells. iScience 28, 111690 (2025).

Lei, K. et al. Cancer-cell stiffening via cholesterol depletion enhances adoptive T-cell immunotherapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 1411–1425 (2021).

Tello-Lafoz, M. et al. Cytotoxic lymphocytes target characteristic biophysical vulnerabilities in cancer. Immunity 54, 1037–1054.e7 (2021).

Mittelheisser, V. et al. Evidence and therapeutic implications of biomechanically regulated immunosurveillance in cancer and other diseases. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 281–297 (2024).

Lorenz, C., Forsting, J., Style, R. W., Klumpp, S. & Köster, S. Keratin filament mechanics and energy dissipation are determined by metal-like plasticity. Matter 6, 2019–2033 (2023).

Yu, M. et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science 339, 580–584 (2013).

Padmanaban, V. et al. E-cadherin is required for metastasis in multiple models of breast cancer. Nature 573, 439–444 (2019).

Youssef, K. K. et al. Two distinct epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition programs control invasion and inflammation in segregated tumor cell populations. Nat. Cancer 5, 1660–1680 (2024).

Grasset, E. M. et al. Mapping the breast tumor microenvironment: proximity analysis reveals spatial relationships between macrophage subtypes and metastasis-initiating cancer cells. Oncogene 43, 2927–2937 (2024).

Goetz, J. G. et al. Endothelial cilia mediate low flow sensing during zebrafish vascular development. Cell Rep. 6, 799–808 (2014).

Hyenne, V. et al. Studying the fate of tumor extracellular vesicles at high spatiotemporal resolution using the zebrafish embryo. Dev. Cell 48, 554–572.e7 (2019).

Rosendahl, P. et al. Real-time fluorescence and deformability cytometry. Nat. Methods 15, 355–358 (2018).

Stoletov, K. et al. Visualizing extravasation dynamics of metastatic tumor cells. J. Cell Sci. 123, 2332–2341 (2010).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Guevorkian, K., Colbert, M.-J., Durth, M., Dufour, S. & Brochard-Wyart, F. Aspiration of biological viscoelastic drops. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 218101 (2010).

Diel, E. E., Lichtman, J. W. & Richardson, D. S. Tutorial: avoiding and correcting sample-induced spherical aberration artifacts in 3D fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 15, 2773–2784 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of J.G.G.’s team for their constant helpful discussions throughout this investigation. J.G.G. is the coordinator of the NANOTUMOR Consortium, a program from ITMO Cancer of Alliance Nationale pour les Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé (AVIESAN), National Alliance for Life Sciences and Health within the framework of the Cancer Plan (France). Work and people in J.G.G.’s laboratory are mostly supported by the Institut National Du Cancer (INCa), French National Cancer Institute, charities (La Ligue contre le Cancer, Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC) and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM)), the National Plan Cancer Initiative, the Region Grand Est, INSERM and the University of Strasbourg, as well as from local donors (Rohan Athlétisme Saverne, Trailers De La Rose and Club Féminin Lampertheim). This work has been directly funded by support from the Ligue Contre le Cancer (labelisation) and the association Ruban Rose, with additional support from INCa. V.G. has been funded by INSERM, region Grand Est and La Ligue Contre le Cancer. La Ligue Contre le Cancer provided support to Z.Y. and G.F. L.B. and L.N.-B. are supported by FRM (ECO202206015567). K.U. is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), project ID 467937258. V.M. was funded by a PhD fellowship from the French Ministry of Science (MESRI) and by the Foundation ARC. J.G. acknowledges core funding by the Max Planck Society. D.J.M. acknowledges funding by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 310030_215690/1). The production and characterization of the polyacrylamide beads used in this study were supported by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme number 953121 (project FLAMIN-GO). R.G. is supported by the FLAMIN-GO project. We thank P. Kessler and I. Busnelli from PICSTRA (CRBS). We thank the animal facility PEFRE (CRBS). We thank P. Patel, part of the TDSU Lab-on-a-chip systems at MPL, for the production of the master template and microfluidic chips used for the bead production. We thank U. Appelt and M. Mroz of the Core Unit Cell Sorting and Immunomonitoring of the Nikolaus Fiebiger Centre for Molecular Medicine (NFZ) at the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg for their technical support in bead sorting. We thank R. Lo, S. Tarte-Deckert and M. Deckert for providing the M229 R/S cell lines. We thank A. Detappe for providing access to the MPA setup. We thank J. Vitre for their help with culturing the CTC-45 and CPP-45 patient-derived cell lines. This work is dedicated to the memory of our co-author Jochen Guck in gratitude for his friendship and scientific vision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.G.G., J.G., N.O., S.H. and V.G. Methodology: O.L., A.L., S.H., K.U., D.B., R.G. and S.G. Investigation: V.G., Z.Y., G.F., L.B., L.N.-B., K.U., O.L., A.L., G.E.M.A., L.P., V.H., V.M. and M.K. Resources: R.G., S.G., G.B. and J.P. Formal analysis: V.G., G.F., L.N.-B., K.U., O.L., T.S. and A.M. Writing—original draft: V.G., J.G.G., N.O., G.F., S.H., M.K., R.G., S.G. and J.G. Writing—review and editing: V.G., J.G.G. and N.O. Supervision: J.G.G., J.G., D.B., V.H., R.C. and D.J.M. Funding acquisition: J.G.G., N.O., S.G., D.B., J.G. and D.J.M. Study supervision: N.O., J.G. and J.G.G.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.K., S.G. and J.G. are co-founders and shareholders of Rivercyte GmbH, a company developing and selling deformability cytometers for research and clinical use. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks Bo Huang, Miranda Hunter, Paolo P. Provenzano and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Small size and low elasticity of circulating objects facilitate lodging in constraining blood vessels.

a, 3D render of the zebrafish embryo caudal plexus. White arrows indicate circulation route through large vessels and yellow arrows indicate routes through small vessels. b, Real Time-Deformability Cytometry plot of D2A1 tumour cells and relative properties of polyacrylamide bead populations designed to model circulating tumour cells (N = 1, n (cells) = 5000). c, Ratio of arrest occurring in each vascular subregion of the ZF embryo for large (19 µm) and small (11 µm) bead populations. (N = 2, n = 44 (large) and 32 (small)) (2-way ANOVA followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). d, Ratio of arrest occurring in each vascular subregion of the ZF embryo for stiff (2.0 kPa) and soft (0.3 kPa) bead populations. (N = 2, n = 22 (large) and 26 (small)) (2-way ANOVA followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg) e, Injection of tumour cell lines with different cell diameters in the zebrafish embryo. f, Ratios of cell diameter normalized to 1675 cell line and ratios of arrest occurring in small vessels of the ZF embryo for various tumour cell lines. ((Measure of diameter: n (cells) = 90 (for each cell line)) (Ratio of arrest in small vessels: n (embryos) = 28 (1675), 36 (D2A1), 27 (NIH3T3), 26 (A431), 30 (4T1) and 20 (ZMEL-1))). g, Correlation test of ratio of cell diameter normalized to 1675 cell line and ratio of arrest occurring in small vessels. ((Measure of diameter: n (cells) = 90 (for each cell line)) (Ratio of arrest in small vessels: n (embryos) = 28 (1675), 36 (D2A1), 27 (NIH3T3), 26 (A431), 30 (4T1) and 20 (ZMEL-1))). (Spearman r). Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation in c, d, f, and g.

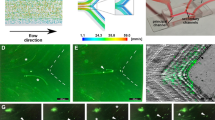

Extended Data Fig. 2 CTCs use viscous deformation to enter small-sized vessels.

a, Beads arrested in the DA, AVJ, CV and CPCs. b, Location and volumetric mean of pressure of arrested beads. (N = 6, n (beads) = 42). c, Volumetric mean of pressure sustained by arrested beads in the different subregions of the ZF embryo. (N = 6, n (beads) = 8 (DA), 10 (AVJ), 8 (CV), 7 (ISVs) and 9 (CPCs)) (Kruskal-Wallis followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). d, Volumetric mean of pressure sustained by arrested beads at occlusion sites vs all other sites. (N = 6, n (beads) = 16 (occlusion sites) and 26 (other sites)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). e, Volume of beads arrested in LVs and SVs. (N = 6, n (beads) = 26 (LVs) and 16 (SVs)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). f, Flatness of beads arrested in LVs and SVs. (N = 6, n (beads) = 26 (LVs) and 16 (SVs)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). g, D2A1 tumour cells arrested in the DA, AVJ, CV and CPCs. h, Flatness of D2A1 tumour cells arrested in LVs and SVs. (N = 2, n (cells) = 44 (LVs) and 47 (SVs)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). i, Elongation and flatness of beads and D2A1 tumour cells arrested in ZF embryos. (N = 6 (beads) and 2 (cells), n (beads or cells) = 42 (beads) and 91 (cells)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). j, ATP production in cells treated with control PBS vs PBS 2 mM sodium azide (NaN3), 10 mM 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) (N = 1, n (wells) = 3 (control and treated)) (Two-tailed Welch’s t-test). k, Normalized change in aspect ratio as a function of normalized time (0% = arrival at occlusion site, 100% = entry completion in ISV) spent at ISV entrance for polyacrylamide elastic beads, D2A1 and ATP-deprived D2A1 tumour cells (N = 6 (beads) and 2 (D2A1 and ATP-deprived D2A1), n (events of arrival, arrest and completed entry at DA-ISV connections) = 26 (beads), 32 (D2A1) and 17 (ATP-deprived D2A1). Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation in c-f and h-k.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Knock-down of cytoskeleton genes alters viscoelastic properties and intravascular behaviour of tumour cells.

a, Protein expression of target-proteins 3 days post-transfection with siRNA. Lanes were rearranged for side-by-side display in vimentin and caveolin-1 blots. N (WB) = 1, n (protein extractions) = 5 for all conditions. b, Micropipette aspiration assay time lapses of siRNA-treated D2A1 tumour cells. First and last frames display cytoplasm (green) and nucleus (blue) segmentations. Green and blue arrowheads respectively indicate progression of cytoplasm and nucleus aspiration in the glass capillary. c, Mechanical phenotypes resulting from siRNA treatments in D2A1 tumour cells. d, Mechanically-tuned D2A1 tumour cells arrested in the caudal plexus of ZF embryo 5 mpi. Yellow arrows indicate tumour cells arrested in small vessels. e, Heatmaps displaying hotspots of arrest 5 mpi of siRNA-treated D2A1 tumour cells in ZF embryos. (N = 3 (siLMNA, siCAV1), n (embryos) = 18 (siLMNA), 15 (siCAV1)). f, Fold changes in arrest patterns in ZF embryos 5 mpi and viscoelastic properties as measured in MPA for siRNA-treated D2A1 tumour cells. g, D2A1 NLS-mCherry tumour cell undergoing micropipette aspiration. h, siCTRL- and siLMNA-treated D2A1 NLS-mCherry tumour cells arrested in large or small vessels of ZF embryos. i, Nucleus elongation of siCTRL- and siLMNA-treated D2A1 NLS mCherry tumour cells arrested in large and small vessels of zebrafish embryos (N = 3, n (nuclei) = 14 (siCTRL - LVs), 9 (siLMNA - LVs), 24 (siCTRL – SVs), 22 (siLMNA - SVs) (One-way ANOVA followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Increasing elasticity or viscosity in tumour cells confirms link between viscosity and circulation and arrest patterns.

a, Transgelin expression in siCTRL- vs siTAGLN- treated D2A1 tumour cells and vimentin expression in control vs vimentin-overexpressing D2A1 tumour cells. Lanes were rearranged for side-by-side display in the transgelin blot. N (WB) = 1, n (protein extractions) = 5 for all conditions. b, Ratios of elasticity and viscosity normalized to control of siCTRL and siTAGLN- Treated D2A1 tumour cells. (N = 2, n (cells) = 14 (siCTRL) and 19 (siTAGLN)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test of ratio of elasticity; Two-tailed Welch’s t-test of ratio of viscosity). c, Ratios of elasticity and viscosity normalized to control of CTRL and mVIM- transfected D2A1 tumour cells. (N = 2, n (cells) = 20 (CTRL) and 19 (mVIM)) (Two-tailed Welch’s t test of ratio of elasticity; Man-Whitney test of ratio of viscosity). d, Mechanical phenotypes resulting from siTAGLN and mVIM transfections in D2A1 tumour cells. e, Mechanically tuned D2A1 tumour cells arrested in ZF embryos 5 mpi. Yellow arrows indicate tumour cells arrested in small vessels. f, Heatmaps displaying hotspots of arrest 5 mpi of mechanically tuned D2A1 tumour cells in ZF embryos. (N = 4 (CTRL, mVIM); 2 (siCTRL, siTAGLN), n (embryos) = 19 (CTRL); 18 mVIM, siTAGLN); 15 (siCTRL)). g, Ratio of arrest occurring in small vessels of ZF embryos for mechanically tuned D2A1 tumour cells. (N = 4 (CTRL, mVIM); 2 (siCTRL, siTAGLN), n (embryos) = 15 (siCTRL); 18 (mVIM, siTAGLN); 19 (CTRL)). (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney) h, Fold changes in arrest patterns in ZF embryo 5 mpi and viscoelastic properties as measured in MPA for mechanically tuned D2A1 tumour cells. Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation in b, c and g.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Intravascular behaviour of human tumour cells confirms link between viscosity and circulation and arrest patterns.

a, Ratio of elasticity of M229 R / S and CTC- / CPP-45 tumour cell line pairs normalized to M229 R and CTC-45 respectively (N = 6 (M229 R, M229 S) and 3 (CTC-45, CPP-45), n (cells) = 24 (M229 R), 27 (M229 S), 16 (CTC-45), 22 (CPP-45)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney (M229 R vs M229 S); Two-tailed Welch’s t-test (CTC-45 vs CPP-45)). b, Ratio of viscosity of M229 R / S and CTC- / CPP-45 tumour cell line pairs normalized to M229 R and CTC-45 respectively (N = 6 (M229 R, M229 S) and 3 (CTC-45, CPP-45), n (cells) = 24 (M229 R), 27 (M229 S), 16 (CTC-45), 22 (CPP-45)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). c, Tumour cells arrested in ZF embryos 5 mpi. Yellow arrows indicate tumour cells arrested in small vessels. d, Heatmaps displaying hotspots of arrest 5 mpi of tumour cells in ZF embryo (N = 2 (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, M229 R, M229 S, CTC-45 and CPP-45), n (embryos) = 11 (MCF-7), 18 (MDA-MB-231), 12 (M229 R and M229 S), 13 (CTC-45) and 15 (CPP-45)). e, Fold changes in arrest patterns in ZF embryo 5 mpi and viscoelastic properties for paired tumour cell lines. f, Correlation test of fold change in ratio of arrest occurring in small vessels and fold change in ratio of elasticity (Extended Data Figs. 3f, 4h and 5e) (Spearman r). Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation in a-b.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Location heatmaps of intravascular, pocketed and extravasated tumour cells.

a, Heatmaps displaying hotspots of intravascular and extravasated siRNA-treated D2A1 tumour cells 24 hours post-injection. (N = 12 (siCTRL); 3 (siMYH9, siVIM, siCAV1, siLMNA), n (embryos) = 128 (siCTRL), 18 (siMYH9), 30 (siVIM), 23 (siCAV1), 33 (siLMNA)). b, Heatmaps displaying hotspots of intravascular, pocketed and extravasated siRNA-treated D2A1 tumour cells 3 hours post-injection. (N = 4 (siCTRL); 2 (siMYH9, siVIM, siCAV1, siLMNA), n (embryos) = 45 (siCTRL), 12 (siMYH9), 24 (siVIM), 23 (siCAV1), 17 (siLMNA)).

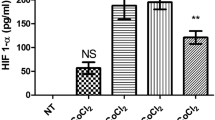

Extended Data Fig. 7 Endothelial remodeling dynamics are affected by tumour cell viscosity and don’t require of tumour cells that they undergo deformation.

a, Ratio of intravascular cells 3 hours post-injection of mechanically altered tumour cells. (N = 4 (siCTRL); 2 (siMYH9, siVIM, siCAV1, siLMNA), n (embryos) = 45 (siCTRL); 12 (siMYH9); 24 (siVIM); 23 (siCAV1); 17 (siLMNA)) (Kruskal-Wallis followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). b, Ratio of pocketed cells in large vessels of the ZF embryo 3 hpi of mechanically-altered tumour cells. (N = 4 (siCTRL); 2 (siMYH9, siVIM, siCAV1, siLMNA), n (embryos) = 44 (siCTRL); 11 (siMYH9); 22 (siVIM); 23 (siCAV1); 16 (siLMNA)) (Kruskal-Wallis followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). c, Ratio of pocketed or extravasated cells 3 hpi for single cells vs grouped cells. (N = 4, n (cells) = 42 (single) and 32 (grouped)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). d, D2A1 tumour cells pocketed in the DA, AVJ, CV, ISVs and CPCs 3 hpi. Yellow stars indicate tumour cell-containing endothelial pockets. e, D2A1 tumour cells extravasated between the CV and the CPCs. Yellow stars indicate the location of the cells in the extravascular space between the CV and the CPCs. f, D2A1 tumour cells extravasated around ISVs 3 hpi. Yellow star indicates extravascular location of the tumour cell. g, Ratio of early extravasation events in different vascular subregions of the ZF embryo 3 hpi of siCTRL-treated D2A1 tumour cells. (N = 4, n (embryos) = 26 (DA), 39 (AVJ), 27 (ISVs) and 34 (CV+CPCs)) (Kruskal-Wallis followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). h, Graphical summary of the indirect impact of cell viscosity on tumour cell extravasation. As established previously, the constraining vessels in which early completed extravasation events occur are more accessible to low viscosity tumour cells. i, Pocketed D2A1 tumour cell 3 hpi and corresponding 3D renders. Yellow star indicates tumour cell-containing endothelial pocket. j-l, Normalized volume, elongation and flatness of intravascular, pocketed and extravasated D2A1 tumour cells 3 hpi. (N = 2, n (cells) = 78 (intravascular), 12 (pocketed) and 15 (extravasated)) (Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation in a-c, g and j-l.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Extravasation dynamics of paired human tumour cell lines support link between viscosity and endothelial remodeling-driven extravasation.

a, Heatmaps displaying hotspots of intravascular, pocketed and extravasated patient-derived tumour cells 24 hpi. (N = 2 (All cell lines), n (embryos) = 39 (MCF-7), 55 (MDA-MB-231), 40 (M229R), 29 (M229S, CTC-45), 26 (CPP-45)). b, Ratio of pocketed cells 24 hours post-injection of MCF-7 vs MDA-MB-231 tumour cells. (N = 2 (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231), n (embryos) = 39 (MCF-7), 55 (MDA-MB-231)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). c, Ratio of extravasated cells 24 hpi of M229 R vs M229 S tumour cells. (N = 2 (M229 R, M229 S), n (embryos) = 40 (M229 R), 29 (M229 S)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). d, CPP-45 tumour cells arrested in ZF embryo 24 hpi. Yellow arrows indicate extravasated cells. e, Ratio of extravasated cells 24 hpi of CTC-45 vs CPP-45 tumour cells. (N = 2 (CTC-45, CPP-45), n (embryos) = 29 (CTC-45), 25 (CPP-45)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation in b-c and e.

Extended Data Fig. 9 The viscoelastic profile of CTCs has a lasting impact on post-extravasation metastatic outgrowth.

a, D2A1 tumour cells arrested in the mouse lung vasculature 1 hpi and corresponding 3D render. b, Quantification of elongation of mechanically altered D2A1 tumour cells arrested in the mouse lung vasculature 1 hpi (N = 4 (siCTRL), 3 (siTAGLN), 2 (siLMNA) and 1 (siMYH9, siVIM) n (cells) = 77 (siCTRL), 28 (siMYH9), 49 (siVIM), 61 (siLMNA), 55 (siTAGLN)) (Kruskal-Wallis followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). c, Flatness of mechanically altered D2A1 tumour cells arrested in the mouse lung vasculature 1 hpi (N = 4 (siCTRL), 3 (siTAGLN), 2 (siLMNA) and 1 (siMYH9, siVIM) n (cells) = 77 (siCTRL), 28 (siMYH9), 49 (siVIM), 61 (siLMNA), 55 (siTAGLN)) (Kruskal-Wallis followed by original FDR method of Benjamini and Hochberg). d, Cell elongation in ZF embryo small vessels vs mouse lung vasculature. (N = 2 (ZF), 4 (Mouse), n (cells) = 47 (Zebrafish SVs), 217 (Mouse lungs)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). e, Cell flatness in ZF embryo small vessels vs mouse lung vasculature. (N = 2 (ZF), 4 (Mouse), n (cells) = 47 (Zebrafish SVs), 217 (Mouse lungs)) (Two-tailed Mann-Whitney). f, Mechanically-altered D2A1 tumour cells arrested in the mouse lung vasculature 1 hpi. g, Mechanically altered D2A1 tumour cells arrested in the mouse lung vasculature 24 hpi and 3D renders for discrimination of intravascular and extravascular cells. h, Quantification of intravascular and extravascular mechanically altered D2A1 tumour cells in the mouse lung vasculature 24 hpi. (N = 4 (siCTRL) and 2 (siMYH9, siVIM, siLMNA, siTAGLN), n (cells) = 40 (siCTRL), 18 (siMYH9), 19 (siVIM), 13 (siLMNA, siTAGLN)) (Fischer’s exact test). i, Metastatic foci originating from mechanically altered tumour cells 10 dpi to the mouse lung vasculature. Data are presented as mean +/- standard deviation in b-e. N corresponds to number of 10-week-old BALB/c female mice used in the experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Pan-organ assessment of the lasting impact of tumour cell viscoelasticity on metastatic outgrowth.

a, Pan-organ bioluminescence imaging-based assay for metastatic outgrowth assessment 15 dpi. b-l, Bioluminescence imaging and quantification of organs displaying bioluminescence total flux superior to the average of the siVIM group 15 dpi (intracardiac) of siRNA-treated D2A1 tumour cells. N (Experiments) = 3 for all organs probed. n (number of organs) = 9 (siCTRL), 12 (siVIM), 9 (siMYH9) for brains, 8 (siCTRL), 11 (siVIM), 9 (siMYH9) for livers, 9 (siCTRL), 13 (siVIM), 8 (siMYH9) for guts, 8 (siCTRL), 13 (siVIM), 8 (siMYH9) for pairs of kidneys, 8 (siCTRL), 10 (siVIM), 8 (siMYH9) for ovaries / uterus and 8 (siCTRL), 13 (siVIM), 8 (siMYH9) for spleens. Chi-square tests were performed in c, e, g, i, k and m). 9 (siCTRL), 13 (siVIM) and 9 (siMYH9) female 10-week-old BALB/c mice were used in this experiment.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–4, Text, Discussion, Methods, uncropped western blots for Supplementary Fig. 4 and References.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Figures.

Source data

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3a

Unprocessed western blots related to Extended Data Fig. 3a.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4a

Unprocessed western blots related to Extended Data Fig. 4a.

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data for Fig. 5.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 1.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 2.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 3.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 4.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 5.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 7.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 8.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 9.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 10.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gensbittel, V., Yesilata, Z., Bochler, L. et al. Cell viscosity influences haematogenous dissemination and metastatic extravasation of tumour cells. Nat. Mater. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02462-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02462-w