Abstract

Sex differences manifest in various traits, as well as in the risk of cardiovascular, metabolic and immunological conditions. Despite the clear physical changes induced by gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT), little is known about how it affects underlying physiological and biochemical processes. Here we examined plasma proteome changes over 6 months of feminizing GAHT in 40 transgender individuals treated with estradiol plus one of two antiandrogens: cyproterone acetate or spironolactone. Testosterone levels dropped markedly in the cyproterone group, but less so in those receiving spironolactone. Among 5,279 total proteins measured, feminizing GAHT changed the levels of 245 and 91, in the cyproterone and spironolactone groups, respectively, with most (>95%) showing a decrease. Proteins associated with male spermatogenesis showed a marked decrease in the cyproterone group, attributable specifically to loss of testosterone. Changes in body fat percentage and breast volume following GAHT were also reflected in the plasma proteome, including an increase in leptin expression. We show that feminizing GAHT remodels the proteome toward a cis-female profile, altering 36 (cyproterone) and 22 (spironolactone) of the top 100 sex-associated proteins in UK Biobank adult data. Moreover, 43% of cyproterone-affected proteins overlapped with those altered by menopausal hormone therapy in cis women, showing the same directional changes, with notable exceptions including CXCL13 and NOS3. Feminizing GAHT skewed the protein profile toward that linked to asthma and autoimmunity, while GAHT with cyproterone specifically skewed it away from an atherosclerosis-associated profile, suggesting a protective effect. These results reveal that feminizing GAHT reshapes the plasma proteome in a hormone-dependent manner, with implications for reproductive capacity, immune regulation and long-term health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Sex differences span a wide range of physiology and behavior1. Males and females also show differences in a wide range of circulating biomolecules, including protein concentrations2, some associated with sex hormone levels3,4,5, particularly estradiol and testosterone6,7. Sex is also important in specifying risk of certain diseases, with females more likely to develop autoimmune conditions but less susceptible to a range of infections relative to males6,8,9.

Gender incongruence occurs when an individual’s gender identity does not align with that assigned at birth10. This includes people with binary (man and woman) and nonbinary identities. It is estimated that 1.6 million individuals identify as transgender in the USA alone11 and gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) represents a critical medical intervention for many to align their physical characteristics with their gender identity10,12,13,14,15. A common protocol for feminizing GAHT involves the administration of estradiol, a form of estrogen, in combination with antiandrogens that decrease the effects of testosterone through androgen receptor antagonism and/or inhibit testosterone synthesis10. There are extensive data on various phenotypic changes during GAHT, but less is known about impacts on underlying physiological and biochemical processes. Our previous research showed that feminizing GAHT remodels plasma metabolites and epigenetic marks in blood cells16,17, and a recent study showed that masculinizing GAHT alters the transcriptional and open chromatin profile of a range of immune cells, as well as inflammatory proteins in the circulation18.

The human circulatory system contains a diverse array of proteins that are essential for, and reflective of, physiological processes across the entire body19. Each individual has a defined ‘baseline’ plasma proteome influenced by multiple factors, including genetics, age, weight, diet and sex2,5,20,21,22,23,24. Consequently, protein biomarkers serve both as indicators and as therapeutic targets across a range of human conditions, including infertility, cancer and immune system dysregulation19,25,26,27,28. At present, the influence of GAHT on the plasma proteome and underlying physiology remains unclear. In this study, we used the Olink Explore HT proteomics platform to comprehensively characterize the levels of 5,279 proteins in a group of adults undergoing 6 months of feminizing GAHT with estradiol in combination with one of two different antiandrogens; spironolactone (SPIRO) and cyproterone acetate (CPA). CPA leads to greater testosterone suppression than SPIRO, as it both inhibits testosterone synthesis and acts as a more potent androgen receptor antagonist29. Our study characterizes the impact of feminizing GAHT on the plasma proteome, particularly differences arising in association with altered estradiol and/or testosterone, and assesses the likely impact on systemic physiological processes linked to long-term health outcomes

Results

Antiandrogen-specific remodeling of plasma proteins in feminizing GAHT

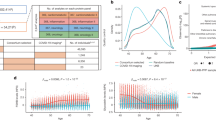

To explore how feminizing GAHT changes the plasma proteome, we assessed longitudinal plasma samples from 40 transgender people at baseline and 6 months after feminizing GAHT, collected as part of a randomized clinical trial30. Two groups of GAHT were included: one with estradiol plus antiandrogen CPA, and the other with estradiol plus antiandrogen SPIRO (Fig. 1a). The Olink Explore HT platform was used to measure the 5,279 plasma proteins (Fig. 1a). Over the 6-month treatment period, blood estradiol concentrations increased to the target concentration (>250 pmol l−1) in 17/20 CPA participants and 16/20 SPIRO participants, while testosterone decreased to target concentration (<2 nmol l−1) in 20/20 CPA participants and 9/20 SPIRO participants (Fig. 1b and Table 1). In total, the levels of 245 (4.6% of all tested) and 91 (1.7% of all tested) proteins were changed following 6-month feminizing GAHT with CPA or SPIRO, respectively (adjusted P value <0.05), with the majority of proteins (>95%) showing lower expression (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). These proteins remained significant when only participants that reached their target estradiol concentrations were included in the analysis (Supplementary Table 2). There were marked similarities in protein expression change in both antiandrogen groups with 37 common proteins (Fig. 1d), such as increased leptin (LEP) and decreased SPINT3 (Fig. 1c,e). However, there were notable differences, with several proteins associated with immune function increased in the CPA group only, such as CXCL13 and CCL28 (Fig. 1f,g and Extended Data Fig. 1). To identify the molecular pathways that are reflected in the changes in plasma protein levels following each type of feminizing GAHT, we performed pathway analysis (Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). CPA-associated proteins (adjusted P value <0.05) were enriched for immune response and cytokine signaling, while SPIRO-associated proteins were adhesion and extracellular organization (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Using a multiplex cytokine assay, we validated the changes in immune-related proteins identified by Olink and show that GAHT-induced proteomic changes occur as early as 3 months after therapy (Extended Data Fig. 1e–h).

a, Olink data for 5,279 proteins was generated in plasma collected at baseline (0 m) and after 6 months (6 m) of feminizing GAHT with CPA (n = 20) or SPIRO (n = 20). Illustrations from NIAID NIH BioArt Source. https://bioart.niaid.nih.gov/bioart/416. b, Boxplots of serum estradiol (left) and testosterone (right) concentrations (log2) at baseline and 6 months after GAHT in CPA (n = 20) and SPIRO (n = 20) groups. c, Volcano plots of Olink protein changed between baseline and 6 months after GAHT for CPA (left) and SPIRO (right). y axis, log10 Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P value; x axis, log2 fold change (FC) (6 m − baseline); dashed line, adjusted P value <0.05. d, Venn diagram of significant proteins overlapping between the two antiandrogen groups (top) and direction of change based on logFC (bottom). e–g, Boxplots of example proteins that change in both groups (common; e), CPA group only (f) and SPIRO group only (g). Protein level values for n = 20 participants are shown in each boxplot. Boxplots show the median (center), 25th–75th percentiles (bounds) and whiskers extending to minima and maxima within 1.5× IQR; outliers are plotted individually. All P values shown were derived from a linear mixed-effects model (nlme R package), using two-sided tests with multiple-comparison correction (Benjamini–Hochberg).

Testosterone concentration and changes in body composition are the major drivers of proteomic remodeling in feminizing GAHT

Next, we sought to understand the main underlying drivers of GAHT-associated plasma proteome changes. Each participant was ranked, relative to all others, based on mean fold change in protein expression for all 299 significant (adjusted P value <0.05) proteins (Fig. 2a), which revealed that participants receiving CPA generally showed higher fold changes in protein levels over time (14 out of top 20 responders; Fig. 2a). Baseline characteristics, such as age and body mass index (BMI) did not predict response to GAHT; however, reaching target testosterone (<2 nmol l−1) was associated with greater change in protein profile (Fig. 2a). As only 9 out of 20 individuals receiving SPIRO reached target testosterone concentration, we were able to investigate this in greater detail (Extended Data Fig. 2a). While most reproductive-tract-secreted proteins, such as SPINT3 and INSL3, were significantly reduced across the SPIRO group, the magnitude of reduction was greater among those who reached target testosterone levels (Fig. 2b–d, Extended Data Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Table 2). These testis-associated proteins correlated strongly with circulating testosterone concentration in our cohort and less so with circulating estradiol concentration (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Table 3). We then identified proteins associated with two phenotypes influenced by feminizing GAHT: body fat percentage and breast volume, across all individuals (Fig. 2e,f). Both percent fat and breast volume increased after 6 months of GAHT in most participants, and these measures were associated with changes in 38 and 249 plasma proteins, respectively (Fig. 2g,h and Supplementary Table 4). LEP, which is produced by adipose tissue31, was positively associated with both phenotypes (Fig. 2g–j). Among other GAHT-associated proteins, prolactin (PRL) and CXCL13 showed strong evidence of a positive association with breast volume, while SPINT3 and INSL3 showed strong evidence of a negative association (Fig. 2g,h).

a, Participants were ranked by mean NPX log2FC of proteins significantly associated with CPA-GAHT or SPIRO-GAHT (Padj <0.05). Each participant was labeled by clinical phenotype. b, Boxplot and individual line plots for INSL3 NPX level at baseline (0 months) and 6 months after GAHT (n = 20 in CPA group and n = 20 in SPIRO group). c, Correlation plot of testosterone concentration and INSL3 NPX values. Gray-shaded error band represents the 95% confidence interval of the fit. d, Boxplot of INSL3 levels in SPIRO group by target testosterone (n = 20 for 0 months, n = 11 for 6 months not reached target, n = 9 for 6 months reached target). e,f, Line graph showing log2FC from baseline to 6 months per individual in CPA and SPIRO groups for percentage fat (e) and breast volume (f). g, Volcano plot of proteins associated with percentage fat. h, Volcano plot of proteins associated with breast volume. y axis: log10 Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P value. x axis: log2FC (6 months − baseline). Dashed line: adjusted P value <0.05. i, Correlation plot of LEP levels and percentage fat. j, Correlation plot of LEP levels and mean breast volume. Gray dots, baseline SPIRO; black dots, baseline CPA; orange dot, 6 months GAHT with SPIRO; red dots, 6 months GAHT with CPA. Gray-shaded error band represents the 95% confidence interval of the fit. Boxplots show the median (center), 25th–75th percentiles (bounds) and whiskers extending to minima and maxima within 1.5× IQR; outliers are plotted individually. All P values shown were derived from a linear mixed-effects model (nlme R package), using two-sided tests with multiple-comparison correction (Benjamini–Hochberg).

Feminizing GAHT skews the plasma proteome toward a cis-female profile

To assess whether feminizing GAHT alters proteins that differ between cis males and cis females in the general population, we accessed data from the Pharma Proteomics Project, of 2,922 plasma proteins in 54,219 UK Biobank participants2 (Fig. 3a). In total, 2,606 proteins in our panel were also quantified in the earlier UK Biobank Olink panel (Fig. 3b). This included the 212 GAHT/CPA-associated and 81 GAHT/SPIRO-associated proteins we identified, representing 8.1% and 3.1% of all proteins in the UK Biobank panel (Fig. 3b). We calculated the enrichment of our GAHT dynamic proteins with the top 100 proteins associated with sex, age or BMI in the UK Biobank dataset (Fig. 3c). This analysis revealed that 36 and 22 of the top 100 sex-associated proteins were associated with feminizing GAHT with CPA or SPIRO, respectively (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 5). A marked fold change difference in protein levels from baseline to 6 months was also observed for the top sex-associated proteins (Fig. 3d). By contrast, only 11 and 8 of the top 100 age-associated and 9 and 6 of the top 100 BMI-associated proteins in UK Biobank participants were associated with feminizing GAHT with CPA or SPIRO, respectively (Fig. 3c). The direction of change was generally toward a cis-female pattern in both antiandrogen groups (Fig. 3e,f). Interestingly, 19 out of the top 100 sex-associated proteins are produced by the male reproductive tract (Human Protein Atlas32), and these drive the majority of differences between the CPA and SPIRO groups (Fig. 3g). By contrast, when the remaining 81 non-reproductive tract proteins were analyzed, both groups still shifted toward a female-like pattern, but the difference between CPA and SPIRO was no longer evident (Fig. 3g).

a, Overview of the UK Biobank dataset (n = 54,219) with 2,922 Olink proteins and key phenotypes comparison sex, age and BMI. b, Venn diagram of overlapping proteins between our 5,279 panel and UK Biobank (UKB) 2,922 panel (left) and percentage of UKB proteins that are associated with GAHT (right). c, Column graph showing percentage of the top 100 proteins associated with sex, age or BMI that are affected by feminizing GAHT. d, Bar plot showed the change (estimate) in protein expression in CPA-GAHT group between 0 months and 6 months of feminizing GAHT for top proteins associated with age, sex and BMI. e, Correlation plot of estimates for the top 100 sex-associated proteins between males and females (y axis) and CPA-GAHT (x axis). f, Correlation plot of estimates for the top 100 sex-associated proteins between males and females (y axis) and SPIRO-GAHT (x axis). g, Dot plot showing mean log2FC (6 months − 0 months) per participant for two sets of top 100 sex-associated proteins: male reproductive tract-associated proteins (n = 19) and all other proteins (n = 81). Higher values indicate stronger skew toward cis-female profile. Red dots, CPA-GAHT; orange dots, SPIRO-GAHT.

Proteome changes induced by feminizing GAHT reflect those in menopause and menopausal hormone therapy

We hypothesized that other periods of sex hormone change would similarly impact the plasma levels of proteins sensitive to feminizing GAHT. Using the same UK Biobank dataset, we identified proteins associated with sex-related phenotypes (Fig. 4a), including menopausal hormone therapy (MHT; yes/no), menopause (yes/no), hysterectomy (yes/no), oophorectomy (yes/no) or circulating sex hormone concentrations (at adjusted P value <0.05) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). There is a clear decline in estradiol in UK Biobank females not receiving MHT from 57 years onward (Fig. 4c). Conversely, females receiving MHT have lower, but consistent levels of estradiol from 40 to 75 years (Fig. 4c). In stratified analysis of females younger than 57 years, we found that 84% and 91% of CPA (212) and SPIRO (81) associated proteins varied in association with menopause, which represents a 1.8- and 2-fold enrichment compared with all UK Biobank quantified proteins (‘background’) for CPA and SPIRO groups, respectively (Fig. 4b). Only three proteins were significantly associated with menopause in women over 57 years and were therefore not analyzed for enrichment (Supplementary Table 7). MHT in women over 57 years was 2.6 and 3.2 times more enriched for CPA- and SPIRO-associated proteins compared with background, respectively (Fig. 4b). Hysterectomy or oophorectomy, not stratified by age, were associated with a smaller percentage of total proteins in the circulation; however, they were 1.8 and 2.2 times more enriched for CPA-associated proteins compared with background (Fig. 4b Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 7). Finally, we identified proteins that correlate with estradiol and testosterone concentrations in cis females and cis males in the UK Biobank, adjusted for age and BMI (Supplementary Table 7). As expected, there was enrichment for CPA and SPIRO associated proteins (Fig. 4b). When assessing the relationship between protein change with GAHT (6 months − baseline) relative to MHT (yes versus no) for female participants over 57 years old, we observed 83 out of 92 proteins change in same direction, indicating that MHT essentially has the same effect as GAHT for many proteins (Fig. 4d). Meanwhile, menopause in women under 57 years showed an inverse relationship, with 157 out of 179 proteins that decreased with CPA-GAHT instead increasing during menopause (Fig. 4e). As expected, proteins reduced by feminizing GAHT were negatively associated with estradiol concentration in cis females and positively associated with testosterone concentraitons in both cis females and males (Extended Data Fig. 4). Some proteins showed expected patterns, such as PRL and LEP, which were elevated following feminizing GAHT and MHT, positively associated with estradiol in cis females, and negatively associated with testosterone in cis males (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 4). Meanwhile, nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3) was elevated during feminizing GAHT with CPA, but was higher in cis males compared to cis females, decreased with MHT and was negatively associated with estradiol concentration in cis females (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 7).

a, Summary of sex-specific phenotypes and number of indivduals with Olink data in the UK Biobank. b, Column chart showing percentage of the GAHT-associated proteins (CPA, n = 212; SPIRO, n = 81) that are also significantly associated with female-specific phenotypes. Red bar, CPA-GAHT; orange bar, SPIRO-GAHT. Number on top of bar indicates fold enrichment relative to background. c, Scatter plots of circulating estradiol levels and age in UK Biobank females not on MHT (left; N = 4,877) or on MHT (right; N = 1,203), with the vertical dashed line at age 57 denoting the chosen cutoff for MHT-related analyses. d, Correlation between CPA-associated proteins change and MHT in women older than 57 years old (red box highlights most populated quadrant). e, Correlation between CPA-associated proteins change and menopause in women younger than 57 years old (red box highlights most populated quadrant).

Feminizing GAHT induced protein changes are associated with clinical phenotypes

To understand the potential implications of feminizing GAHT on overall health and health risks, we investigated whether the protein changes were associated with complex phenotypes in the general population. Two sets of data were used; 283 phenotypes previously associated with plasma proteins in the UK Biobank by Olink24 and 217 phenotypes previously associated with proteins in an Icelandic cohort by an alternative technology, Somascan33 (Fig. 5a). Phenotypes from both datasets were grouped into seven broad categories: behavior, biomarker, clinical, diet, hormone, immune and vascular. CPA-associated proteins were enriched for 97 Olink and 60 Somascan phenotypes, while SPIRO-associated proteins were enriched for 92 Olink and 90 Somascan phenotypes. There was a high overlap in enriched phenotypes in the CPA and SPIRO protein lists (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table 8). By plotting the adjusted P value and log2 fold change enrichment of each phenotype, we observed strong enrichment for terms related to body fat and water mass, serum glucose and urea in both CPA and SPIRO groups, as well as phobias and panic disorders in the SPIRO group (Fig. 5b–e). Other top terms across categories included ‘testosterone’, ‘time of last use of oral contraception’, ‘monocyte’ and ‘eosinophil’ percentage in blood, and ‘systolic blood pressure’ (Fig. 5b,c and Supplementary Table 8). We then examined whether feminizing GAHT induces protein changes that converge with or diverge from disease- or phenotype-associated signatures (Fig. 5d), with full directional data in Supplementary Table 8. This revealed that GAHT induced changes converging toward those observed in allergic asthma (Fig. 5e), allergic rhinitis and autoimmune disease, and diverging patterns to those associated with atherosclerosis (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table 8).

a, Venn diagram showing enrichment of GAHT-associated proteins with complex phenotypes from the UK Biobank using two proteomic platforms: Olink (left; 283 phenotypes) and SOMAscan (right; 217 phenotypes). Enrichment of GAHT-associated proteins across phenotypes was assessed using an overrepresentation test (hypergeometric distribution), with two-sided P values adjusted for multiple comparisons (Benjamini–Hochberg). Terms were considered enriched at Padj <0.05 and FC >1.33. b,c, Volcano plots showing enriched terms for CPA-associated (b) and SPIRO-associated (c) proteins. y axis, log10 adjusted P value; x axis, log2 fold change enrichment of each phenotype relative to baseline. Phenotypes are colored by category (clinical, biomarker, immune, vascular, diet, hormone or behavior). d, Bubble plot showing the direction of change (green, converging; peach, diverging) for selected phenotypes in CPA and SPIRO groups. Circle size reflects the number of significantly associated proteins (1–100). e, Correlation plot of proteins associated with allergic asthma showing the CPA-GAHT estimate on the x axis and the disease-associated beta value on the y axis. f, Correlation plot of proteins associated with atherosclerosis showing the CPA-GAHT estimate on the x axis and the disease-associated odds ratio (OR) on the y axis. The red square signifies the primary direction of overlapping protein concentration change.

Discussion

Despite the increasing use of GAHT to align physical and gender identities, the long-term health implications remain largely unclear. Previous studies have highlighted concerns such as bone loss34,35,36, poorer cardiovascular health37 and fertility issues38,39 with feminizing GAHT. In particular, the antiandrogen CPA has been linked with increased carotid intima-media thickness40 (a measure of cardiovascular risk) and acute liver injury41 and is not approved for GAHT by the US Food and Drug Administration. Recent longitudinal studies have shown that GAHT alters circulating metabolites16, epigenetic markers in blood17 and transcriptional profiles of immune cells18. Here, we used the Olink Explore HT technology to simultaneously measure the levels of thousands of proteins in plasma of people undergoing feminizing GAHT with two different antiandrogens: CPA and SPIRO. Our study revealed widespread alterations in the plasma proteome after 6 months of treatment, including general GAHT-related changes in proteins associated with reproduction and body composition, as well as distinct differences between CPA and SPIRO antiandrogen therapies (Figs. 1 and 2), particulary in proteins linked to immunity and cardiovascular phenotypes.

Feminizing GAHT results in a 25–50% decrease in testis volume within 2 years42,43,44, in association with a loss of mature sperm production45,46,47,48. In line with this, our analysis showed that achieving target testosterone levels was associated with a reduction in circulating proteins essential for male reproductive function in both the SPIRO and CPA groups (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 2). The most reduced protein, SPINT3, is primarily localized to the testis and seminal vesicle and is important for sperm production49,50. It is also the top sex-associated plasma protein identified in UK Biobank data from 54,219 adults (Supplementary Table 5). We also observed a marked reduction of INSL351 following feminizing GAHT. INSL3 is a marker of Leydig cell development and function in the testes52,53,54, and reduced plasma levels probably reflect declining spermatogenesis. It is unclear whether such changes are fully reversible following discontinuation of hormone therapy to recover spermatogenesis potential38 or whether transgender people may consider preserving fertility through sperm cryopreservation before commencing GAHT. The idenfication of circulating protein markers linked to reproductive capacity may also have utility in tracking specific aspects of feminizing GAHT outcome independent of gross phenotypic change.

Metabolic changes associated with variation in body composition, such as muscle loss, following GAHT have been described16. Here, we found that feminizing GAHT increases circulating LEP levels in association with higher fat content and breast volume (the primary outcome of our original clinical trial30) (Fig. 2g–j), independent of antiandrogen (CPA or SPIRO) used. Interestingly, PRL, a hormone involved in breast tissue development and lactation, was also associated with breast volume following GAHT (Fig. 2h), despite being selectively elevated following GAHT in CPA antiangrogen group (Fig. 2f).

The immune system shows widespread sex-specific difference in both structure (cellular composition) and function6. Generally, females have an enhanced protection against infection, but an elevated risk of autoimmune disease6,8. These sex-specific differences are partly specified by genetic factors but are primarily attributable to variation in sex hormones, particularly estrogens and androgens6,7,8,55,56. At present, the degree to which immune system function, and associated risk, change following feminizing GAHT remains unclear. We showed a strong elevation of several immune-related proteins in the CPA antiandrogen group, and to a lesser extent in the SPIRO group (Extended Data Fig. 1). Some of these changes are evident as early as 3 months following GAHT commencemt (Extended Data Fig. 1). The chemokine CXCL13, involved in B cell recruitment and dysregulated in autoimmune disease57, was one of the few proteins to show elevated levels following GAHT, specifically in association with CPA treatment (Fig. 1f). CXCL13 is an important immune regulator and biomarker of response to anti-PD1 cancer therapy in females58. It is also a prognostic marker for pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease59, and elevated levels in blood are implicated in the risk of several autoimmune diseases60. Our findings warrant further investigation into CXCL13 levels in relation to autoimmune disease risk and cancer immunotherapy outcomes in individuals undergoing feminizing GAHT with CPA.

A recent study showed that sex was a major overall contributor to variation in the plasma proteome, second only to genetic factors61. Here, we showed that feminizing GAHT with estradiol, plus SPIRO or CPA, changed the circulating levels of 22 or 36 of the top 100 sex-specific circulating proteins in the UK Biobank2, respectively. Therefore, within a relatively short period, changes in circulating sex hormone concentrations can alter a substantial proportion of sex-associated circulating proteins identified in the general population (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5). As expected, feminizing GAHT alters the plasma proteome toward a cis-female signature, with the strongest effect attributable to a decrease in male reproductive tract-associated proteins, primarily in the CPA group (Fig. 3g). Given the previously described risks of acute liver injury associated with CPA41, the dramatic effect on markers of male fertility observed here and the lack of any gross difference between the antiandrogen approaches related to external feminization (as assessed by breast volume), SPIRO may be the preferable choice for those undergoing feminizing GAHT aiming to maintain future fertility.

There are several other time points and interventions in the life course associated with hormonal change. Taking advantage of data from the UK Biobank, we showed that both menopause and MHT alter GAHT-associated proteins (Fig. 4), as anticipated based on underlying changes in sex hormone levels. We note that estradiol concentrations were detectable in only 21.4% of the female participants, limiting our ability to characterize the full range of estradiol variation associated with female-specific phenotypes (Supplementary Table 5). The majority of MHT-induced changes were in the same direction as those observed with GAHT, with notable exceptions, including endothelial NOS3 (Fig. 4). NOS3 is essential for vascular tone regulation, and rare loss-of-function variants have been causally linked to increased risk of coronary artery disease, hypertension and myocardial infarction, largely due to impaired nitric oxide bioavailability62. Interetsingly, NOS3 is higher in cis males compared with cis females, and our data suggest that GAHT with CPA results in even higher levels of this protein (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Finally, we show that feminizing GAHT with CPA or SPIRO alters levels of proteins associated with a range of complex clinical phenotypes, such as bone density, cardiovascular measures, allergic asthma and neuronal pathways24. CPA and SPIRO both induced protein changes convergent with ‘allergic asthma’ and ‘any autoimmune disease’, reflecting the positive effect of estradiol on these diseases63. A limitation of this analysis is that ‘autoimmune disease’ is an umbrella term for several diseases, and it is not specified which diseases were included in this term in the Iceland cohort24,33. Interestingly, contrary to reports of pro-atherogenic effect of CPA in animal models and polycystic ovary syndrome40,64, we observed that CPA induced changes in protein levels that were divergent with atherosclerosis and systolic blood pressure, suggesting a protective effect against cardiovarsular disease (Fig. 3e). This includes proteins such as FGF23, which is associated with cardiovascular disease and inversely correlated with circulating estrogen concentrations65,66.

Our discovery cohort is relatively small in size (n = 40 participants) and focused on feminizing GAHT, but is strengthened by the use of longitudinal measures for each individual. Furthermore, while the 6-month sampling period was sufficient to detect significant proteomic changes, it may not fully capture the long-term effects of GAHT. As such, future studies should aim to include larger groups of transgender individuals, including masculinizing GAHT, and extend the follow-up period to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term impacts. Moreover, the observable shift in immune-related proteins warrants an investigation of immune-cellular profiles over time in GAHT individuals. Finally, larger cohorts will enable consideration of innate factors (such as genetics) and environmental influences (such as diet and lifestyle), which are known to impact the plasma proteome, in future analyses.

Our study demonstrates the profound impact of feminizing GAHT on the proteome, reflecting physiological changes and a shift toward a cis-female proteome profile. The decrease in testis-expressed proteins is consistent with the suppression of testicular function and largely attributable to underlying testosterone levels. The observation that hormonal changes during natural periods in cisgender adult females produce effects similar to those seen with feminizing GAHT suggests that sex hormones exert broadly comparable physiological effects across both female and male genetic backgrounds. Feminizing GAHT also induced changes that converged with allergic disease and diverged from cardiovascular disease risk, highlighting the importance of further research into the long-term health effects of feminizing GAHT in transgender individuals.

Methods

Ethics and recruitment

This research was conducted using biospecimens collected during the clinical trial titled ‘A randomized double-blind trial comparing the effectiveness of antiandrogen medications in trans and gender diverse individuals’ (Universal Trial Number: U1111-1248-7232, ANZCTR registration ACTRN12620000339954) and was approved by the Austin Health Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics Approval Number: HREC/44503/Austin-2018)30. Participants were recruited from a tertiary referral hospital in Melbourne, Australia, between 31 August 2020 and 15 March 2022. Inclusion criteria included transgender people (transgender women and nonbinary people assigned male at birth) aged 16–80 years who were about to commence treatment with feminizing GAHT using standard doses of estradiol and antiandrogens to achieve sex steroid concentrations in the female reference range. Participants were provided with a Participant Information Sheet/Consent Form and gave written informed consent for their blood samples to be used in future studies, including blood analysis and genetic analysis.

Study participants

Proteomic data were generated using plasma samples from 40 participants at two time points (‘baseline’ before GAHT and ‘6 months’ after GAHT). Participant age at baseline ranged from 18 to 58 years, with a mean of 25.7 years at the baseline blood collection. Demographic information, including age and BMI, is presented in Table 1. Notably, none of the participants changed their weight category during the 6-month GAHT period. Some participants had preexisting conditions, including seven with depression or anxiety and two with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Validation of a subset of immune proteins was generated from 49 transgender participants at three time points (baseline, 3 months after GAHT and 6 months after GAHT)16.

Feminizing GAHT regimen and sex hormone measures

The study focused on 40 individuals undergoing feminizing GAHT. Participants were commenced on oral estradiol valerate 4 mg daily (or transdermal dose equivalent using patches or gel). Estradiol dosing was titrated at months 1, 2 and 3 to achieve serum estradiol concentrations 250–600 pmol l−1, in line with Australian consensus guidelines67. The median oral estradiol valerate dose was 6 mg at 6 months. In addition, participants were randomized using permuted block randomization to one of two antiandrogens: 12.5 mg daily CPA (n = 20) or 100 mg daily SPIRO (n = 20)30. Serum estradiol and total testosterone were measured using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry using the Shimadzu LC connected to an AB Sciex 5500 mass spectrometer, as previously described30. Median sex hormone levels at baseline and after 6 months of GAHT are presented in Table 1. In addition to estradiol and testosterone, the concentrations of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, PRL and sex hormone-binding globulin were measured at baseline and 1, 2, 3 and 6 months after GAHT. For participants where sex hormone data were not available at 6 months, the measurement at 3 months was used to determine if they reached target concentration.

Blood collection and plasma sample preparation

Approximately 7 ml of venous blood was collected for research in sodium heparin tubes at baseline and at 3 and 6 months after feminizing GAHT. Blood was collected after an overnight fast. For all samples, the plasma component was separated from cellular components by centrifugation (10 min at 500g, room temperature). Plasma samples were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

OLINK proteomics

Plasma samples were thawed and centrifuged (10 min at 500g), before being shipped on dry ice to Novogene in Singapore to assess 5,328 proteomic biomarkers with the antibody-based Olink Explore HT. The Explore HT platform utilizes Olink’s Proximity Extension Assay technology, where multiplexed oligonucleotide-labeled antibody probe pairs attach to their target protein in the sample. Protein expression is quantified by next-generation sequencing. Protein concentrations are expressed as the relative concentration unit normalized protein expression (NPX). Values were log2-transformed to account for heteroskedasticity2,68. The panel includes validated biomarkers for circulating and secreted proteins related to a range of biological processes, including immunology, reproduction and metabolism, and cancer biomarkers.

LUMINEX cytokine assay

The Human 48-Plex Luminex assay for cytokines was performed on the blood plasma from 49 transgender people at baseline, 3 months and 6 months after feminizing GAHT. Raw cytokine measurements were naturally log-transformed and internally standardized (z score) before statistical analysis. Mixed linear models were analyzed using the ‘nlme’ package in R version 4.1.2. P values were corrected for false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg approach, and a significance threshold was set at P < 0.05.

Statistical analysis of plasma protein biomarkers

Olink NPX values were used for analysis with the ‘nlme’ package (R version 4.1.2) for mixed linear models69. The statistical models tested how plasma proteomic biomarkers were affected by (1) feminizing GAHT (comparing six-mount with baseline proteome), (2) circulating concentration of estradiol across both time points and (3) circulating concentration of total testosterone at across both time points. All linear models were adjusted for age and baseline BMI as covariates and included a random intercept for participant ID. The second and third models investigated associations between log-transformed hormone levels and proteomic biomarkers, also using a random intercept for participant ID. P values were adjusted for false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. All boxplots plotted in the figures show the median (center), 25th–75th percentiles (bounds) and whiskers extending to minima and maxima within 1.5× interquartile range (IQR).

Analysis of plasma proteome data from the UK Biobank dataset

The UK Biobank is one of the largest biomedical databases, comprising data from over 500,000 participants recruited between 2006 and 2010 across 22 centers in England, Scotland and Wales70,71. Olink NPX values for 2,922 proteins of 54,219 participants in the UK Biobank were accessed through the UK Biobank Research Analysis Platform (UKB-RAP). Health data were extracted for individual participants to link sex-specific phenotypes to expression of proteins in the circulation. For all male and female participants, we extracted sex and age (categorical variables) and circulating estradiol and testosterone (as continuous variables). For female participants, we extracted several female-specific categorical factors: menopause, use of MHT, hysterectomy and oophorectomy. As several sex-related phenotypes are age-associated, such as menopause, we stratified our analysis by age, separating females younger than 57 years from those 57 and older. This cutoff also ensured an approximately equal number of participants in each age group (Supplementary Table 6). The ‘nlme’ package was used to test plasma protein biomarkers associated with (1) MHT use and menopause (stratified by age: younger than 57 years old or 57 and older), hysterectomy and oophorectomy across all ages in females, (2) circulating estradiol concentrations across all ages in both females and males and (3) circulating total testosterone concentrations across all ages in both females and males. A limitation of this analysis is that estradiol concentrations were detectable in only 21.4% of female participants with Olink proteomic data. By contrast, 94.2% of male participants had measurable testosterone concentrations. All linear models were adjusted for age and BMI as covariates. For the hormone analyses, log-transformed hormone levels were used to assess associations with proteomic biomarkers (Supplementary Table 6). P values were adjusted for false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg method72, with statistical significance set at an adjusted P value <0.05.

Pathways and phenotype enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis were performed with Homer using gene names encoding for differential proteins, with the full set of 5,279 protein names used as the ‘background’ gene set73. To determine which GO terms or KEGG pathways were significantly enriched in the differentially expressed proteins, a hypergeometric test was used. The results of this enrichment analysis were visualized using the ggplot2 package in R. Tissue-specific expression of proteins in the Human Protein Atlas was mapped using the TissueEnrich tool and presented as low, intermediate or high expression per tissue per protein32. Enrichment of GAHT-associated proteins in the UK Biobank Olink-phenotype dataset was calculated using supplementary data from Eljarn et al.24. Analysis was restricted to 337 phenotypes that had more than 40 proteins mapped, and enrichment of GAHT-associated proteins for these phenotypes was calculated using a hypergeometric test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The affinity proteomics data have been deposited to the PRIDE74 repository with the dataset identifier PAD000016.

Code availability

R code for reproducing figures and phenotype enrichment analysis is available via GitHub at https://github.com/BNovLab/Feminizing-Gender-Affirming-Hormone-Therapy-Proteomics.

References

Kelley, D. B. Sexually dimorphic behaviors. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 225–251 (1988).

Sun, B. B. et al. Plasma proteomic associations with genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature 622, 329–338 (2023).

Cai, M. L. et al. Proteomic analyses reveal higher levels of neutrophil activation in men than in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 13, 911997 (2022).

Militello, R. et al. Modulation of plasma proteomic profile by regular training in male and female basketball players: a preliminary study. Front. Physiol. 13, 813447 (2022).

Wingo, A. P. et al. Sex differences in brain protein expression and disease. Nat. Med. 29, 2224–2232 (2023).

Klein, S. L. & Flanagan, K. L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 626–638 (2016).

Dunn, S. E., Perry, W. A. & Klein, S. L. Mechanisms and consequences of sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20, 37–55 (2024).

Shepherd, R., Cheung, A. S., Pang, K., Saffery, R. & Novakovic, B. Sexual dimorphism in innate immunity: the role of sex hormones and epigenetics. Front. Immunol. 11, 604000 (2020).

Whitacre, C. C. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2, 777–780 (2001).

Coleman, E. et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J. Transgend. Health 23, S1–S259 (2022).

Herman, J. L., Flores, A. R. & O’Neill, K. K. How Many Adults and Youth Identify as Transgender in the United States? (The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, 2022).

Foster Skewis, L., Bretherton, I., Leemaqz, S. Y., Zajac, J. D. & Cheung, A. S. Short-term effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on dysphoria and quality of life in transgender individuals: a prospective controlled study. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 717766 (2021).

Baker, K. E. et al. Hormone therapy, mental health, and quality of life among transgender people: a systematic review. J. Endocr. Soc. 5, bvab011 (2021).

van Leerdam, T. R., Zajac, J. D. & Cheung, A. S. The effect of gender-affirming hormones on gender dysphoria, quality of life, and psychological functioning in transgender individuals: a systematic review. Transgend. Health 8, 6–21 (2023).

Nolan, B. J., Zwickl, S., Locke, P., Zajac, J. D. & Cheung, A. S. Early access to testosterone therapy in transgender and gender-diverse adults seeking masculinization: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2331919 (2023).

Shepherd, R. et al. Impact of distinct anti-androgen exposures on the plasma metabolome in feminizing gender-affirming hormone therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 109, 2857–2871 (2024).

Shepherd, R. et al. Gender-affirming hormone therapy induces specific DNA methylation changes in blood. Clin. Epigenet. 14, 24 (2022).

Lakshmikanth, T. et al. Immune system adaptation during gender-affirming testosterone treatment. Nature 633, 155–164 (2024).

Sun, B. B. et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 558, 73–79 (2018).

Coenen, L., Lehallier, B., de Vries, H. E. & Middeldorp, J. Markers of aging: unsupervised integrated analyses of the human plasma proteome. Front. Aging 4, 1112109 (2023).

Goudswaard, L. J. et al. Effects of adiposity on the human plasma proteome: observational and Mendelian randomisation estimates. Int. J. Obes. 45, 2221–2229 (2021).

Kalnapenkis, A. et al. Genetic determinants of plasma protein levels in the Estonian population. Sci. Rep. 14, 7694 (2024).

Altelaar, A. F., Munoz, J. & Heck, A. J. Next-generation proteomics: towards an integrative view of proteome dynamics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 35–48 (2013).

Eldjarn, G. H. et al. Large-scale plasma proteomics comparisons through genetics and disease associations. Nature 622, 348–358 (2023).

Martins, A. D., Panner Selvam, M. K., Agarwal, A., Alves, M. G. & Baskaran, S. Alterations in seminal plasma proteomic profile in men with primary and secondary infertility. Sci. Rep. 10, 7539 (2020).

de Azambuja Rodrigues, P. M. et al. Proteomics reveals disturbances in the immune response and energy metabolism of monocytes from patients with septic shock. Sci. Rep. 11, 15149 (2021).

Ivansson, E. et al. Large-scale proteomics reveals precise biomarkers for detection of ovarian cancer in symptomatic women. Sci. Rep. 14, 17288 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Next-generation sequencing and proteomics of cerebrospinal fluid from COVID-19 patients with neurological manifestations. Front. Immunol. 12, 782731 (2021).

Burinkul, S., Panyakhamlerd, K., Suwan, A., Tuntiviriyapun, P. & Wainipitapong, S. Anti-androgenic effects comparison between cyproterone acetate and spironolactone in transgender women: a randomized controlled trial. J. Sex. Med. 18, 1299–1307 (2021).

Angus, L. M. et al. Effect of spironolactone and cyproterone acetate on breast growth in transgender people: a randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 110, e1874–e1884 (2024).

Obradovic, M. et al. Leptin and obesity: role and clinical implication. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 585887 (2021).

Jain, A. & Tuteja, G. TissueEnrich: tissue-specific gene enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics 35, 1966–1967 (2019).

Ferkingstad, E. et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat. Genet. 53, 1712–1721 (2021).

Bretherton, I. et al. Bone microarchitecture in transgender adults: a cross-sectional study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 37, 643–648 (2022).

van der Loos, M. et al. Bone mineral density in transgender adolescents treated with puberty suppression and subsequent gender-affirming hormones. JAMA Pediatr. 177, 1332–1341 (2023).

Dobrolinska, M. et al. Bone mineral density in transgender individuals after gonadectomy and long-term gender-affirming hormonal treatment. J. Sex. Med. 16, 1469–1477 (2019).

Connelly, P. J. et al. Gender-affirming hormone therapy, vascular health and cardiovascular disease in transgender adults. Hypertension 74, 1266–1274 (2019).

de Nie, I. et al. Successful restoration of spermatogenesis following gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender women. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100858 (2023).

Rodriguez-Wallberg, K. et al. Reproductive health in transgender and gender diverse individuals: a narrative review to guide clinical care and international guidelines. Int J. Transgend. Health 24, 7–25 (2023).

Gode, F. et al. Alteration of cardiovascular risk parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome who were prescribed to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 284, 923–929 (2011).

Cyproterone. in LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017).

Schneider, F., Kliesch, S., Schlatt, S. & Neuhaus, N. Andrology of male-to-female transsexuals: influence of cross-sex hormone therapy on testicular function. Andrology 5, 873–880 (2017).

Meyer, W. J. III et al. Physical and hormonal evaluation of transsexual patients: a longitudinal study. Arch. Sex. Behav. 15, 121–138 (1986).

Fisher, A. D. et al. Cross-sex hormone treatment and psychobiological changes in transsexual persons: two-year follow-up data. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 4260–4269 (2016).

Jindarak, S. et al. Spermatogenesis abnormalities following hormonal therapy in transwomen. BioMed. Res. Int. 2018, 7919481 (2018).

Vereecke, G. et al. Characterisation of testicular function and spermatogenesis in transgender women. Hum. Reprod. 36, 5–15 (2021).

Leavy, M. et al. Effects of elevated beta-estradiol levels on the functional morphology of the testis—new insights. Sci. Rep. 7, 39931 (2017).

Jiang, D. D. et al. Effects of estrogen on spermatogenesis in transgender women. Urology 132, 117–122 (2019).

Clauss, A., Persson, M., Lilja, H. & Lundwall, A. Three genes expressing Kunitz domains in the epididymis are related to genes of WFDC-type protease inhibitors and semen coagulum proteins in spite of lacking similarity between their protein products. BMC Biochem. 12, 55 (2011).

Robertson, M. J. et al. Large-scale discovery of male reproductive tract-specific genes through analysis of RNA-seq datasets. BMC Biol. 18, 103 (2020).

Ivell, R. & Anand-Ivell, R. Biology of insulin-like factor 3 in human reproduction. Hum. Reprod. Update 15, 463–476 (2009).

Ivell, R., Mamsen, L. S., Andersen, C. Y. & Anand-Ivell, R. Expression and role of INSL3 in the fetal testis. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 868313 (2022).

Ivell, R., Wade, J. D. & Anand-Ivell, R. INSL3 as a biomarker of Leydig cell functionality. Biol. Reprod. 88, 147 (2013).

Anand-Ivell, R., Heng, K., Hafen, B., Setchell, B. & Ivell, R. Dynamics of INSL3 peptide expression in the rodent testis. Biol. Reprod. 81, 480–487 (2009).

Khan, D. & Ansar, A. S. The immune system is a natural target for estrogen action: opposing effects of estrogen in two prototypical autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 6, 635 (2015).

Chakraborty, B. et al. Estrogen receptor signaling in the immune system. Endocr. Rev. 44, 117–141 (2023).

Law, C. et al. Interferon subverts an AHR–JUN axis to promote CXCL13+ T cells in lupus. Nature 631, 857–866 (2024).

Brennan, M. et al. T-cell expression of CXCL13 is associated with immunotherapy response in a sex-dependent manner in patients with lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 12, 956–963 (2024).

Vuga, L. J. et al. C-X-C motif chemokine 13 (CXCL13) is a prognostic biomarker of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 189, 966–974 (2014).

Pan, Z., Zhu, T., Liu, Y. & Zhang, N. Role of the CXCL13/CXCR5 axis in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 13, 850998 (2022).

Carrasco-Zanini, J. et al. Mapping biological influences on the human plasma proteome beyond the genome. Nat. Metab. 6, 2010–2023 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Nitric oxide synthase-3 deficiency results in hypoplastic coronary arteries and postnatal myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 35, 920–931 (2014).

Merrheim, J. et al. Estrogen, estrogen-like molecules and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 19, 102468 (2020).

Sanjuan, A. et al. Effects of estradiol, cyproterone acetate, tibolone and raloxifene on uterus and aorta atherosclerosis in oophorectomized cholesterol-fed rabbits. Maturitas 45, 59–66 (2003).

Edmonston, D., Grabner, A. & Wolf, M. FGF23 and klotho at the intersection of kidney and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 11–24 (2024).

Ix, J. H., Chonchol, M., Laughlin, G. A., Shlipak, M. G. & Whooley, M. A. Relation of sex and estrogen therapy to serum fibroblast growth factor 23, serum phosphorus, and urine phosphorus: the Heart and Soul Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 58, 737–745 (2011).

Cheung, A. S., Wynne, K., Erasmus, J., Murray, S. & Zajac, J. D. Position statement on the hormonal management of adult transgender and gender diverse individuals. Med. J. Aust. 211, 127–133 (2019).

Feyaerts, D. et al. Integrated plasma proteomic and single-cell immune signaling network signatures demarcate mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19. Cell Rep. Med 3, 100680 (2022).

Pinheiro J. et al. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-166 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlme/index.html (2025).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57, 289–300 (1995).

Heinz, S. et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010).

Perez-Riverol, Y. et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D543–D553 (2025).

Acknowledgements

B.N., A.S.C., M.M. and R.D., are supported by the Allen Distinguished Investigator program, a Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group advised program of the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. B.N., A.S.C., D.B. and K.C.P. are supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator Grants (1173314 (B.N.), 2008956 (A.S.C.), 1175744 (D.B.) and 2027186 (K.C.P.)). Murdoch Children’s Research Institute is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Program. L.M.A. is supported by an Australian Government Research and Training Program scholarship. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AI179004, Austin Medical Research Foundation, Endocrine Society of Australia Postdoctoral Award and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians Foundation Cottrell Research Establishment Fellowship Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. G.C, T.O.C. and L.A.B.J. were supported by a Competitiveness Operational Programme grant of the Romanian Ministry of European Funds (P_37_762, MySMIS 103587) and by a Romania’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan grant of the Romanian Ministry of Investments and European Projects (PNRR-III-C9-2022-I8, CF 85/15.11.2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.N., R. Saffery, A.S.C. and L.M.A. conceptualized the study. L.M.A. and A.S.C. recruited participants and collected samples. B.W.K., B.A. and R. Shepherd processed blood samples and prepared plasma for proteomics. N.N.L.N. and D.C. conducted formal analysis and T.M. provided statistical support. G.C., T.O.C., L.M.A. and L.A.B.J. and C.L. provided data analysis to support the study. N.N.L.N., D.C., B.N. and R. Saffery wrote the original draft of the paper and made figures. B.N., A.S.C., R. Saffery, M.M., R.A.D., M.N., G.T., D.B. and K.C.P. acquired funding and developed the hypotheses. All authors reviewed and edited the text and approved the final paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Sabra Klein, Ni Landegren and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ashley Castellanos-Jankiewicz and Sonia Muliyil, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Pathways analysis and validation of Olink results by Luminex for CPA-GAHT and SPIRO-GAHT associated proteins.

Bubble plot showing enrichment of GAHT-associated proteins in A. KEGG, B. GO biological processes and C. GO Reactome terms. The size of the circles represents the fraction of targets in each term, while the intensity of the red color indicates the level of significance (log10 p-value). D. Key genes enriched in top terms. E-H. Validation of immune Olink biomarkers using a 48-cytokine Luminex panel in a larger number of participants (n = 49). E. Overview of the Luminex data generation. F. Boxplot showing hormone concentrations over time for 49 participants. G. Scatter plot showing positive correlation between Luminex and Olink (r = 0.77, p = 2.3E-15) for MCP-1. Grey shaded error band represents the 95% confidence interval of the fit. H. Boxplots of MCP-1/CCL2 in Olink data (n = 20; left panel) and luminex data (n = 49; right panel). Boxplots show the median (centre), 25th–75th percentiles (bounds), and whiskers extending to minima and maxima within 1.5×IQR; outliers are plotted individually.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Relationship between protein levels and reaching target testosterone in the SPIRO-GAHT group.

A. Volcano plot of significant proteins in the SPIRO sub-groups that reach target testosterone (left panel, n = 9) and do not reach target testosterone (right panel, n = 11). The y-axis represents -the log10 unadjusted p-value, and the x-axis represents the NPX log2 fold change (6 M – 0 M). The dashed y-intercepts indicate a p-value of <0.05. B. Dot plot showing change in protein rank (log10 scale, y-axis) between ‘reach’ and ‘do not reach’ testosterone groups for the top 20 proteins associated with CPA-GAHT (x-axis). Red dots: testis-produced proteins. Black arrow indicates weaker significance in ‘do not reach group’, red arrow indicates stronger significance in ‘do not reach group’ relative to ‘reach testostorone’ group. C. Boxplot for SPINT3 NPX level at baseline and 6 months post CPA-GAHT and SPIRO-GAHT (n = 20 participant in each boxplot). Boxplot of SPINT3 levels in SPIRO group by target testosterone (n = 20 for 0 m, n = 11 for 6 m not reached target, n = 9 for 6 m reached target). Correlation plot of testosterone concentration and SPINT3 NPX values. Grey shaded error band represents the 95% confidence interval of the fit. Boxplots show the median (centre), 25th–75th percentiles (bounds), and whiskers extending to minima and maxima within 1.5×IQR; outliers are plotted individually.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Proteins associated with circulating testosterone and estradiol concentration in participants receiving GAHT.

Volcano plots of significant proteins associated with A. testosterone and B. estradiol. Y-axis: log10 Benjamini-Hochberg p-value. X-axis: effect size (estimate value) derived from the mixed linear model. The dashed y-intercepts indicate an adjusted p < 0.05. Scatter plots of C. LEP and D. INSL3 correlation with estradiol, testosterone and prolactin concentrations. In each scatter plot the grey shaded error band represents the 95% confidence interval of the fit.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Correlation between protein change in response to GAHT and in association with female-specific phenotypes and hormone concentrations in the UK Biobank.

Correlation plots of CPA-GAHT estimates (x-axis) and A. estimates for hysterectomy in cis-females B. estimates for oophorectomy in cis-females (y-axis), C. estimates for circulating estradiol in cis-females (y-axis), D. estimates for circulating testosterone in cis females, and E. estimates for circulating testosterone in cis males in the UK Biobank.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Levels of select proteins showing differences between sexes, in response to female-specific phenotypes and feminizing GAHT.

A. PRL (prolactin) is significantly higher in females compared to males (left), reduced with MHT (menopausal hormone therapy) under 57 years old, and increased with MHT above 57 years old. PRL increases after 6 months feminising GAHT using CPA, but no change in SPIRO (right). B. LEP (leptin) is significantly higher in females compared to males (left), elevated with MHT both younger and older ages. It also increases following GAHT in both CPA and SPIRO groups (right). C. NOS3 (endothelial nitric oxide synthase 3) is significantly higher in males compared to females (left), reduced in those using MHT above 57 years old, elevated in those with menopause under 57 years old, and increased in CPA group. P-val: p-value; P: adjusted p-value; ns: non-significant. Each boxplot shows n = 20 participants. Boxplots show the median (centre), 25th–75th percentiles (bounds), and whiskers extending to minima and maxima within 1.5×IQR; outliers are plotted individually.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables 1–8

Supplementary Tables 1–8.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, N.N.L., Celestra, D., Angus, L.M. et al. Plasma proteome adaptations during feminizing gender-affirming hormone therapy. Nat Med 32, 139–150 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04023-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-04023-9

This article is cited by

-

Mapping the effects of gender-affirming sex hormone therapy

Nature Medicine (2026)

-

Sex matters: mechanistic insights into sex-driven patterns of autoimmunity and implications for pharmacotherapy

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2026)