Abstract

With global C-section rates rising, understanding potential consequences is imperative. Previous studies suggested links between birth mode and psychological outcomes. This study evaluates the association of birth mode and neurodevelopment in young children across two prospective cohorts, using repeated psychometric assessments. Data from the ELEMENT (Early Life Exposures in Mexico to Environmental Toxicants) and PROGRESS (Programming Research in Obesity, Growth, and Environment and Social Stress) cohorts, comprising 7158 and 2202 observations of 1402 children aged 2 to 36 months, and 726 children aged 5 to 27 months, respectively, were analyzed. Exclusion criteria for the cohorts were maternal diseases such as preeclampsia, renal or heart disease, gestational diabetes, and epilepsy. Neurodevelopment was gauged via Bayley’s Scales of Infant Development: 2nd edition for ELEMENT and 3rd edition for PROGRESS. Mixed-effects models longitudinally estimated associations between birth mode and neurodevelopment scores, adjusting for cofounders. In ELEMENT, psychomotor development composite scores were significantly affected by birth mode from ages 2 to 8 months; the largest estimate within this range was at 2 months (β =-1.93; 95% CI: [-3.64, -0.22], reference: vaginal delivery). For PROGRESS, a negative association was found with motor development composite scores over all the studied age range (β=-1.91; 95% CI: [-3.01, -0.81]). The association was stronger between ages 6 to 18 months, with the strongest estimate at 11 months (β=-2.58; 95% CI: [-4.37, -0.74]). A negative impact of C-section on language scores in girls was estimated for the PROGRESS cohort (β=-1.92; 95% CI: [-3.57, -0.27]), most marked in ages 22 to 25 months (largest β at 24.5 months=-3.04; 95% CI: [-5.79, -0.30]). Children born by C-section showed lower motor and language development scores during specific age windows in the first three years of life. Further research is necessary to understand the complexities and implications of these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although the World Health Organization has stated the optimal cesarean section (C-section) rate should be between 10 and 15% of all births1, in the United States C-section rates have hovered around 32% since the late 2000s2, while some countries report rates as high as 50%3. In Mexico, the mid-1990s saw a C-section rate of around 25% of all births. This number escalated to 35% by 2001, and further rose to 43% by 20103. By 2019, nearly half of all births (48%) were delivered via C-section; in Mexico City, the percentage reached an even higher rate of 52%4. This trend has stirred concerns about potential health implications of C-sections for both mothers and infants. Although C-sections can certainly save lives, they have been associated with adverse developmental and behavioral outcomes in children5,6,7, as well as mental health detriments for mothers, including postpartum depression, reduced likelihood of establishing breastfeeding, and impaired attachment to their babies8,9.

Previous research found that C-section births were associated with lower scores on cognitive and motor development tests at early ages10. Studies have also found evidence of a link between C-section delivery and a higher risk of autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)11. These findings suggest that the mode of delivery may play a significant role in shaping early developmental trajectories. Given the rising global rates of C-sections and their potential implications for child development, it is crucial to further explore these associations.

The first three years of life are often recognized as a critical period in child development, when the impacts of certain experiences or exposures may substantially shape developmental trajectories12. However, as different aspects of neurodevelopment may mature at various age windows during this period, their detailed study necessitates access to cohorts with repeated measures across a broad range of neurodevelopmental outcomes. This study utilized data from the ELEMENT (Early Life Exposures in Mexico to Environmental Toxicants) and PROGRESS (Programming Research in Obesity, Growth, Environment, and Social Stress) cohorts in Mexico City, which provide extensive longitudinal data on child neurodevelopment.

The aim of this study was not only to compare neurodevelopmental outcomes across birth modes but also to identify possible windows of heightened susceptibility to the potential influences of C-section birth, by trying to answer the following questions: Is there a difference in neurodevelopmental outcomes between children born by C-section and those born vaginally? Does birth by C-section influence specific domains of children’s neurodevelopment more significantly? Are there sensitive age windows during this period when the influence of birth by C-section on neurodevelopmental outcomes might be most substantial in terms of effect size? Are there sex-dependent differences in the influence of C-section on children’s neurodevelopment?

Methods

Participants and study design

Both the Early Life Exposure in Mexico to Environmental Toxicants (ELEMENT) and Programming Research in Obesity, Growth, Environment and Social Stressors (PROGRESS) cohorts consist of Hispanic women from Mexico City. ELEMENT (1995–2003) initially enrolled 2170 women, either near delivery or during first-trimester prenatal visits, while PROGRESS (2007–2011) began with 1054 pregnant women, enrolling them before 20 weeks of gestation. Research protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Public Health. The study was thoroughly explained to participating mothers, who signed an informed consent. A parent/guardian provided written informed consent for child participation. All methods were performed in accordance with all relevant Mexican guidelines and regulations, and the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Detailed methodologies for both cohorts are elaborated upon in respective previous publications13,14.

Briefly, common original inclusion criteria for both cohorts excluded women not residing in or planning to leave Mexico City soon. A known diagnosis of preeclampsia, renal or heart disease, gestational diabetes, and epilepsy, were also exclusionary, alongside use of corticosteroids and anti-epilepsy drugs, and significant alcohol or illegal drug consumption. These exclusions were initially designed to minimize confounding by conditions that could independently impact neurodevelopment, in line with the primary objective of studying the effects of toxic metals exposure. For ELEMENT, neurodevelopment assessments were scheduled at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months of the child’s age, though actual visit timings showed variability [see Supplementary Information]. In PROGRESS, these assessments were scheduled at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, with similar variability. All neurodevelopment assessments for both cohorts were conducted at the Department of Developmental Neurobiology of the National Institute of Perinatology in Mexico City. Both cohorts’ data was gathered by the same fieldwork team, and the neurodevelopment assessments were performed by the same team of psychologists.

The analytic sample size, comprising children with at least one neurodevelopment assessment, finally stood at n = 1402 children for ELEMENT and n = 726 children for PROGRESS. A flowchart detailing the initial sample size and the analytic sample size in each cohort appears in the Supplementary Information.

Data collection

Neurodevelopment assessment

Children in both the ELEMENT and PROGRESS cohorts underwent neurodevelopmental assessments using the Bayley Scales. In ELEMENT, the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition (BSID-II), was used to gauge infants’ mental and psychomotor development indices (MDI and PDI)15. Conversely, in PROGRESS, the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (BSID-III), was utilized16. The assessments examined various domains including cognitive aspects such as sensorimotor development and problem-solving, language skills, and motor skills.

The BSID scores used in our study are composite scores, which combine various subtests to assess different domains of development. The scores were calculated based on norms provided in the BSID manuals, which were established from a representative sample of American children15,16. The composite scores are scaled to have an expected mean of 100 and a standard deviation (SD) of 15. For both cohorts, the scales’ instructions and prompts were translated into Spanish and administered by three trained psychologists. Inter-examiner reliability was evaluated at above 0.90 for all indices and scores.

Due to the differences in the structure, scoring systems, and psychometric properties between BSID-II and BSID-III, it was not feasible to combine the neurodevelopmental indices from both cohorts for analysis. BSID-II produces Mental and Psychomotor Development Indices, while BSID-III produces motor, language, and cognitive composite scores, making direct comparison and combination challenging. For example, the Psychomotor Development Index (PDI) from BSID-II has been found to be only moderately correlated with the Motor Composite Score of BSID-III17.

Birth & covariate assessment

Questionnaires were administered around the time of delivery to collect information on mode of birth (vaginal birth or C-section), gestational age at birth, and complications occurring around birth, such as preeclampsia, infections, or others. During the 1st visit to the research center, sociodemographic information such as mother’s age, parental education and marital status was gathered; while maternal intelligence quotient (IQ) was assessed by the Spanish version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)18. Socioeconomic status was retrospectively assessed in both cohorts using previously described methods19,20, in subsamples of ELEMENT (37%) and PROGRESS (68%). The quality of the home environment was assessed using the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Scale21, in subsamples of ELEMENT (25%) and PROGRESS (52%).

Data analysis

Initially, we estimated descriptive statistics of covariates at baseline and outcomes at each age time-point. Subsequently, we assessed baseline differences in the distribution of covariates between mothers who underwent C-sections and those who had vaginal births. This was achieved using simple logistic regression models, with the birth mode (0 = vaginal birth; 1 = C-section) serving as the dependent variable. Notably, this analysis was intentionally performed using all available data rather than restricting it to the final analytic sample. The rationale behind this decision is to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the predictors of C-sections, thereby better identifying likely confounders for the main analysis. Thirdly, for the primary analysis, MDI and PDI from BSID-II, and Cognitive, Language, and Motor scores from BSID-III, were the dependent variables; cohorts were thus analyzed separately. For each cohort, mixed-effects regression models with a random intercept were fitted to longitudinally estimate the effect of C-section on each neurodevelopment score. As mixed models accommodate incomplete data, children with at least one neurodevelopment evaluation were included. A common set of relevant covariates were included in regression models, such as maternal age, schooling, IQ, child’s sex, and a dummy variable for prematurity (gestational age at birth below 37 weeks). Additionally, a 3rd-degree polynomial of the child’s age was included to model neurodevelopment trajectories, as this provided the best fit for the data. Calendar time was accounted for to capture potential secular trends in neurodevelopment, given the extended time span covered by both cohorts. The general form of the models was:

Where yi, t represents the neurodevelopment outcome of the i-th child at the time of the t-th evaluation; Ci is the birth mode of the i-th child; Zi represents a vector of the time-fixed covariates described above, Ai, t is the age of the i-th child at the time of the t-th evaluation, and Ti, t represents calendar time at the t-th evaluation of the i-th child. A second set of models, featuring an interaction term between birth mode and the child’s age polynomial, was fitted to identify critical periods for the effect of birth mode. Sex-stratified models, with both approaches, were also fitted.

Sensitivity analysis

In a sensitivity analysis, models were fitted with additional covariates that were not available for the whole sample, such as the HOME scale, socioeconomic status, and maternal complications, to assess their potential as confounders. A final model included all these additional covariates simultaneously, allowing for the evaluation of the findings’ robustness. Additionally, to address the potential impact of loss to follow-up, we included a dummy variable indicating whether an observation had complete data for the composite scores across all time points in our random-effects regression models. This approach controls for the completeness of the data and ensures the robustness of our findings despite intermittent follow-up. All analyses were performed with Stata v. 17 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the ELEMENT and PROGRESS cohorts, segmented by birth mode. Mothers undergoing C-sections were consistently older compared to those with vaginal deliveries. Furthermore, there were differences in gestational age in ELEMENT, where C-section deliveries resulted in slightly earlier births. Both cohorts revealed disparities in maternal schooling; in ELEMENT and PROGRESS, women who had C-sections had higher average schooling than their vaginal delivery counterparts. Women who underwent C-sections also reported a higher prevalence of complications. Other characteristics exhibited minimal variation between the two birth mode groups.

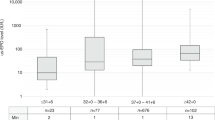

Table 2 presents the ELEMENT cohort’s BSID-II indices and the PROGRESS cohort’s BSID-III scores, categorized by birth mode and age. Overall, children born vaginally had higher mean MDI, PDI, and language scores than C-section births. This trend was consistent across most age groups.

Associations of birth mode with neurodevelopment

In the ELEMENT cohort, across the entire age range (2 to 36 months), birth by C-section had a negative association with both MDI and PDI, with a coefficient (β) of -0.39 (95% CI: [-1.20, 0.42]) and − 0.49 (95% CI: [-1.26, 0.28]), respectively. However, these estimates were not statistically significant. (Table 3).

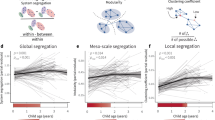

Birth by C-section had a significant negative association to PDI from two to 7.5 months; The largest estimate was at age 2 months (β=-1.93; 95% CI: [-3.64, -0.22]. After 7 months the estimate was attenuated and approached zero at age 30 months. There was no significant association with MDI, although the point estimate hovered around minus 0.6 points, again until age 30 months, approaching zero after that (Fig. 1).

Longitudinal association of birth by C-section and the Mental (A) and Psychomotor (B) Development Indices of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, 2nd Edition, by child’s age in the ELEMENT study (N = 1402, births by C-section = 26.9%). Models adjusted for prematurity, child’s sex, maternal age, IQ, schooling, marital status, and calendar time. The Y-axis represents the adjusted difference of BSID composite scores between birth modes; values below 0 indicate lower development scores in C-section-born children.

In the PROGRESS cohort, across the whole age-range (5 to 27 months), birth by C-section had a negative association with Language, Motor, and Cognitive scores. However, only the effect on the Motor score, a two-point effect, was statistically significant across the entire age range (β=-1.91, 95% CI: [-3.01, -0.81]). (Table 4).

The window for a significant association with Motor development was between ages 6 to 18 months, with the estimate surpassing a 2-point deficit in the score relative to children born vaginally; no windows of significance were found for Language or Cognitive scores (Fig. 2).

Longitudinal association of birth by C-section and the Language (A), Motor (B) and Cognitive (C) Development Scores of the of the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd Edition, by child’s age in the PROGRESS study (N = 726, % C-section = 52.2%). Models adjusted for prematurity, child’s sex, maternal age, IQ, schooling and marital status, and calendar time. The Y-axis represents the adjusted difference of BSID composite scores between birth modes; values below 0 indicate lower development scores in C-section-born children.

Sex-stratified results

In the ELEMENT cohort, there was no significant association between C-section delivery and either the Mental or Psychomotor Development Indices for both girls and boys. In the PROGRESS cohort, girls delivered via cesarean section exhibited significantly lower Language Development scores (β=-1.92; 95% CI: [-3.57, -0.27]), across the entire age range, most marked at ages 22 to 25 months (β at 24.5 months=-3.04; 95% CI: [-5.79, -0.30]). Meanwhile, boys born through cesarean section showed a notable deficit in Motor Development scores (β = -2.17; 95% CI: (-3.70, -0.64)). Full results of the sex-stratified analyses are detailed in the Supplementary Information.

Sensitivity analyses

In the ELEMENT cohort, a marginal negative link with psychomotor scores appeared when incorporating socioeconomic status (SES), but other associations, including those factoring maternal complications and the combined model of SES, HOME, and maternal complications, remained non-significant. It’s noteworthy that the sample size was considerably reduced in the final model.

In the PROGRESS cohort, adjusting for the HOME scale revealed a significant negative tie between C-sections and motor scores. Including SES intensified this negative link with motor scores and showed a marginally significant negative association for language scores. This negative association with motor scores persisted even after accounting for maternal complications and in the final model with all covariates combined. However, the links to language and cognitive scores remained non-significant throughout [see full estimates in Supplementary Information].

The analysis which included a dummy variable for data completeness in our random-effects regression models, demonstrated that the adjusted estimates were consistent with our primary findings. These results are presented in the Supplementary Information, confirming the robustness of our conclusions despite variations in follow-up completeness.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the potential impact of birth by C-section on child neurodevelopmental outcomes during the first three years of life in two Mexican birth cohorts. Findings indicate that children born by C-section, on average, exhibit lower motor scores than those born vaginally during the first 18 months of life. However, this effect appears to wane over time. No significant associations between birth by C-section and mental or cognitive scores were identified across the studied age range, but a significant effect on language scores was estimated in girls, which is particularly strong close to 24 months of age.

A critical consideration in the study is the difficulty in differentiating risk-birth and non-risk birth in C-section deliveries. Prematurity is highly associated with neurodevelopmental deficits in early childhood, and thus premature birth was indeed included in the models. Moreover, additional analyses that included maternal complications were conducted, which did not result in large changes to the effect estimates. These results point to the findings being robust and not significantly influenced by these confounders. Nevertheless, this limitation should be acknowledged, as it is challenging to fully disentangle the effects of these risk factors from the mode of delivery with the limited data at hand.

A wealth of scientific evidence emphasizes that the first 1000 days of life are crucial for neurodevelopment12. Disturbances during this period can have lasting structural and functional consequences for brain development22. The microbiota hypothesis posits that C-sections might disrupt the infant’s microbiome, potentially leading to long-term impacts on immune function and overall health23,24,25,26. While the microbiota’s essential role in postnatal central nervous system maturation is acknowledged, the specific mechanisms connecting microbiota disturbances to cognitive deficits, metabolic disorders, and other issues remain elusive27,28,29. Current research suggests that both stress and microbiota play intertwined roles in birth outcomes and neurodevelopment8,23,24,30. Though the exact pathways remain undefined, the gut microbiota’s influence on the brain encompasses immunological, endocrine, metabolic, and neural routes31,32,33,34. Microbes have been observed to affect neuroendocrine signaling35, and are implicated in several brain functions such as synaptogenesis and neurotransmitter regulation36.

C-section delivery’s link to adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes might stem from the diminished early physical contact and heightened stress for both mother and infant during the procedure. The absence of early skin-to-skin contact, often seen in C-sections, can hinder mother-infant bonding, breastfeeding initiation, and infant thermoregulation37. This contact promotes oxytocin release, vital for social bonding and stress reduction38. Furthermore, the elevated stress and cortisol levels in mothers from C-sections can impact infant neurodevelopment30. Additionally, breastfeeding is tied to better neurodevelopment39, and C-sections might delay its initiation and shorten its duration40. These factors highlight the need to address stress and early contact in clinical practice, given their potential influence on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The observed significant link between C-sections and motor development, but not mental or cognitive growth, might be attributed to the distinct neurobiological processes guiding these domains. Motor development hinges on the maturation of brain regions like the cerebellum, basal ganglia, and motor cortex41. The perinatal stress from a C-section, potentially exacerbated by diminished early mother-child contact, could more acutely impact these motor-centric brain areas37. Conversely, cognitive growth’s breadth might render it more resistant to such stressors, or our study’s assessment tools might have overlooked subtler impacts. Another consideration is the amplified neonatal stress response post C-Sect42, which could uniquely affect neurodevelopment areas such as motor skills more vulnerable to stress43,44. Moreover, external influences, like parental education and early stimulation, might play a greater role in mental and cognitive trajectories, overshadowing birth mode effects45,46. Pinpointing the exact mechanisms behind these disparate outcomes and understanding the lasting repercussions of C-sections on child development domains warrant further research.

The diminishing impact of C-sections on neurodevelopment as observed over time can be attributed to various factors. Initial effects might be counterbalanced by positive environmental influences like responsive caregiving, stimulation, and educational resources47. As children age, influences such as genetics, peer interactions, and schooling become more predominant, potentially overshadowing birth mode effects48. Some research suggests that later environmental factors can mediate associations between early life circumstances, including birth mode, and neurodevelopment49. Additionally, the varying sensitivity of assessment tools at different ages could contribute to the perceived waning effect of C-sections on development.

The sensitivity analysis reaffirmed the associations between C-section delivery and neurodevelopment, especially motor scores. Even after accounting for factors like the HOME scale, socioeconomic status, and maternal complications, the negative tie between C-section and motor development persisted in the whole age-range of the PROGRESS cohort, underscoring the confidence in this result.

Sex-stratified results hint that C-section births might have varied effects on neurodevelopmental outcomes by sex. Boys appear more vulnerable to adverse impacts on motor and psychomotor development from C-sections, whereas language development in girls seems more affected. Differences in developmental trajectories between sexes, influenced by biological and environmental factors, might explain these observations. For instance, girls often develop language skills earlier than boys, possibly making disruptions from C-sections more pronounced in specific developmental stages50. Additionally, male brains, maturing more slowly than female ones, might be more susceptible to perinatal exposures like C-Sect51. Furthermore, altered microbiota from C-sections, could differentially affect boys and girls52. This area is still under active investigation, and more research is needed to understand the mechanisms at play.

The observed effects of birth by C-section on composite scores of the BSID scales, although statistically significant, are subtle, and may not necessarily indicate a clinically significant developmental delay for individual children. However, these small shifts in developmental scores across a large population can have substantial public health implications. For example, even minor reductions in average developmental scores can increase the number of children requiring developmental interventions, thereby impacting educational and health services. Furthermore, children under age three are at their most receptive stage of development, and interventions aimed at reducing exposure to risk factors - such as being subjected to an unnecessary birth by C-section- may permanently and positively alter their development trajectories, ultimately providing great returns for society53.

Early monitoring and intervention are crucial to mitigating these potential developmental risks. Routine developmental screenings for children born via C-section can help identify and address developmental concerns early, allowing for timely interventions that could improve long-term outcomes. Additionally, promoting breastfeeding and ensuring early skin-to-skin contact in cesarean births can help mitigate some of these developmental risks, as these factors are tied to better neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Moreover, these findings highlight the importance of considering cesarean birth within the broader context of other known risk factors for neurodevelopmental outcomes. Factors such as parental education, socioeconomic status, and early childhood stimulation play significant roles in a child’s developmental trajectory and can interact with the mode of delivery. As such, these results underscore the need for comprehensive strategies that address multiple aspects of early childhood development to optimize outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

The current study presents several strengths. It utilizes data from two detailed cohorts, making use of longitudinal information to track and analyze neurodevelopmental outcomes across multiple ages; the longitudinal analysis approach can control for some unobserved confounders54,55. This methodology helps in identifying specific age periods that might be more susceptible. Another strength is the effective management of potential confounders, which is essential in child development studies. The integration of the HOME assessment, which evaluates the quality of a child’s home environment, adds depth to the research. This approach ensures a thorough assessment of the potential effects of C-sections on child neurodevelopment.

A notable limitation of this study is the incompatibility between BSID-II indices and BSID-III scores, which precluded the merging of both cohorts for a unified analysis56. Moreover, the differences between these two versions of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development may have influenced the developmental scores, potentially leading to disparate outcomes in each cohort. This inconsistency might affect the generalizability of the results.

One limitation of this study is the exclusion of women with certain health conditions such as preeclampsia, renal or heart disease, gestational diabetes, and epilepsy. These exclusions were originally designed to control for confounding factors in the primary objectives of the ELEMENT and PROGRESS cohorts, which focused on the effects of toxic metal exposure. However, this may impact the generalizability of the findings, as the cohort is likely healthier overall compared to the general population. Although sensitivity analyses adjusting for maternal complications did not significantly alter our main estimates, the potential influence of these unobserved confounders on the association between birth mode and neurodevelopmental outcomes should be considered. Future studies should aim to include these conditions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between C-section and child neurodevelopment.

This study was also limited by the partial availability of data on key confounders, such as socioeconomic status and the HOME scale, which were only accessible for subsamples of both cohorts. Most notably, the dataset did not allow us to distinguish between elective and emergency C-section procedures, a factor that could potentially exert a significant confounding effect. However, it’s worth mentioning that we did adjust for maternal complications in a subset of the sample, serving as a proxy for emergency situations likely resulting in C-sections (as evident in Table 1). The adjustment did not significantly alter the main conclusions of the analysis, suggesting that the influence of this unobserved confounder may be partially controlled for. Despite these limitations, sensitivity analyses still underscored the significant impact of C-sections on motor development outcomes.

The findings from these Mexican birth cohorts, covering births from 1995 to 2013, provide insights into the effects of cesarean sections on early childhood neurodevelopment. However, caution is needed when generalizing these results. While biological mechanisms linking cesarean birth and neurodevelopment might remain stable, socio-cultural, environmental, and healthcare contexts have likely evolved since the time of the study. This research holds significance as it gives voice to Latin American populations, often underrepresented in developmental studies. Still, the specific socio-cultural factors of these populations may not be universally applicable. Therefore, while this study enriches the existing literature, its findings are bounded by the historical and geographical constraints of the sample. Future studies should aim to confirm these results across diverse, recent, and geographically varied cohorts to comprehensively understand the relationship between cesarean birth and early neurodevelopment.

Conclusions

This study highlights the potential neurodevelopmental risks associated with C-sections, which appear to particularly impact motor and language skills in early childhood. These findings add to the mounting evidence urging a critical reevaluation of non-medically indicated C-sections. The routine reliance on this mode of delivery demands reconsideration, given the paramount importance of safeguarding children’s well-being.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ELEMENT:

-

Early Life Exposure in Mexico to Environmental Toxicants cohort

- PROGRESS:

-

Programming Research in Obesity, Growth, and Environment and Social Stress cohort

- BSID-II:

-

Bayley Scales of Infant Development, 2nd edition

- BSID-III:

-

Bayley Scales of Infant and toddler Development, 3rd edition

- MDI:

-

Mental development Index

- PDI:

-

Psychomotor Development Index

- IQ:

-

Intelligence Quotient

- WAIS:

-

Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale

- HOME:

-

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment scale

References

Betran, A. P., Torloni, M. R., Zhang, J. J. & Gülmezoglu, A. M. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates Vol. 123 (BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2016).

Stephenson, J. Rate of First-time cesarean deliveries on the rise in the US. JAMA Health Forum. 3(7), e222824 (2022).

Betran, A. P., Ye, J., Moller, A. B., Souza, J. P. & Zhang, J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health 6(6) (2021).

2022 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 May 1]. Subsistema de Informacion de Nacimientos de la la Secretaría de Salud de México. http://www.dgis.salud.gob.mx/contenidos/sinais/s_sinac.html

Kelmanson, I. A. Emotional and behavioural features of preschool children born by caesarean deliveries at maternal request. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 10(6), 676–690 (2013).

Sandall, J. et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet 392(10155), 1349–1357 (2018).

Zaigham, M., Hellström-Westas, L., Domellöf, M. & Andersson, O. Prelabour caesarean section and neurodevelopmental outcome at 4 and 12 months of age: an observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20(1), 564 (2020).

Grisbrook, M. A. et al. Associations among caesarean section Birth, post-traumatic stress, and Postpartum Depression symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19(8), 4900 (2022).

Kershenobich, D. Lactancia materna en México. Salud Publica Mex. 59(3, may-jun), 346 (2017).

Polidano, C., Zhu, A. & Bornstein, J. C. The relation between cesarean birth and child cognitive development. Sci. Rep.7(1) (2017).

Curran, E. A. et al. Research Review: birth by caesarean section and development of autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry; 56(5). (2015).

Cusick, S., Georgieff, M. K. & UNICEF. [cited 2023 May 4]. The first 1,000 days of life: The brain’s window of opportunity. (2013). https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/958-the-first-1000-days-of-life-the-brains-window-of-opportunity.html#:~:text=The%20first%201%2C000%20days%20of%20life%20%2D%20the%20time%20spanning%20roughly,across%20the%20lifespan%20are%20established

Perng, W. et al. Early life exposure in Mexico to ENvironmental Toxicants (ELEMENT) project. BMJ Open 9(8) (2019).

Braun, J. M. et al. Relationships between lead biomarkers and diurnal salivary cortisol indices in pregnant women from Mexico City: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Health 13(1) (2014).

Bayley, N. Bayley Scale of Infants Development (Psychological Corporation, 1993).

Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development 3rd edn (Harcourt Assessment Inc, 2006).

Luttikhuizen dos Santos, E. S., de Kieviet, J. F., Königs, M., van Elburg, R. M. & Oosterlaan, J. Predictive value of the Bayley scales of Infant Development on development of very preterm/very low birth weight children: A meta-analysis. Early Hum. Dev. 89(7), 487–496 (2013).

Ryan, J. J. & Lopez, S. J. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. In: Understanding Psychological Assessment 19–42. (Springer US, 2001).

Carrasco, A. V. The AMAI System of Classifying Households by socio-economic Level (ESOMAR. Health & Environmental Research Online (HERO), 2002).

López-Romo, H. Actualización regla amai nse 8× 7. In: Congreso AMAI; Mexico (2011).

Bradley, R. H. HOME Inventory. In: The Cambridge Handbook of Environment in Human Development, 568–589 (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Nelson, C. A., Bhutta, Z. A., Burke Harris, N., Danese, A. & Samara, M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ m3048 (2020).

Gur, T. L., Worly, B. L. & Bailey, M. T. Stress and the commensal microbiota: Importance in parturition and infant neurodevelopment. Front. Psychiatry 6 (2015).

Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. Regulation of the stress response by the gut microbiota: Implications for psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37 (2012).

Cho, C. E. & Norman, M. Cesarean section and development of the immune system in the offspring. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 208(4), 249–254 (2013).

Zhang, C. et al. The effects of Delivery Mode on the gut microbiota and health: State of art. Front. Microbiol. 12 (2021).

Sherwin, E., Sandhu, K. V., Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. May the force be with you: the light and dark sides of the microbiota–gut–brain Axis in Neuropsychiatry. CNS Drugs 30(11) (2016).

Rhee, S. H., Pothoulakis, C. & Mayer, E. A. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6 (2009).

Cryan, J. F. & Dinan, T. G. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13 (2012).

Buss, C., Davis, E. P., Hobel, C. J. & Sandman, C. A. Maternal pregnancy-specific anxiety is associated with child executive function at 69 years age. Stress 14(6) (2011).

Foster, J. A. & McVey Neufeld, K. A. Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 36 (2013).

Cryan, J. F. & O’Mahony, S. M. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 23(3) (2011).

S, T. R. S.K. M. Control of brain development, function, and behavior by the microbiome. Cell. Host Microbe 17(5) (2015).

Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. Gut instincts: microbiota as a key regulator of brain development, ageing and neurodegeneration. J. Physiol. 595(2) (2017).

Sudo, N. et al. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J. Physiol. 558(1) (2004).

Halverson, T. & Alagiakrishnan, K. Gut Microbes in Neurocognitive and Mental Health Disorders Vol. 52 (Annals of Medicine, 2020).

Moore, E. R., Bergman, N., Anderson, G. C. & Medley, N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2016 (2016).

Feldman, R., Rosenthal, Z. & Eidelman, A. I. Maternal-preterm skin-to-skin contact enhances child physiologic organization and cognitive control across the first 10 years of life. Biol. Psychiatry 75(1) (2014).

Belfort, M. B. et al. Infant feeding and childhood cognition at ages 3 and 7 years: effects of breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. JAMA Pediatr. 167(9) (2013).

Prior, E. et al. Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95(5) (2012).

Iverson, J. M. Developing language in a developing body: the relationship between motor development and language development. J. Child. Lang. 37(2) (2010).

Martinez, L. D., Glynn, L. M., Sandman, C. A., Wing, D. A. & Davis, E. P. Cesarean delivery and infant cortisol regulation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 122 (2020).

Davis, E. P. & Sandman, C. A. The timing of prenatal exposure to maternal cortisol and psychosocial stress is associated with human infant cognitive development. Child. Dev. 81(1) (2010).

Gellner, A. K. et al. Stress vulnerability shapes disruption of motor cortical neuroplasticity. Transl Psychiatry 12(1) (2022).

Bornstein, M. H. & Bradley, R. H. in Socioeconomic Status, Parenting, and Child Development. (eds Bornstein, M. H. & Bradley, R. H.) (Routledge, 2014).

Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C. S. & Suwalsky, J. T. D. Physically developed and Exploratory Young Infants Contribute to their own long-term academic achievement. Psychol. Sci.; 24(10). (2013).

Belsky, J. & Pluess, M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to Environmental influences. Psychol. Bull. ;135(6). (2009).

Tucker-Drob, E. M. & Harden, K. P. Early childhood cognitive development and parental cognitive stimulation: evidence for reciprocal gene-environment transactions. Dev. Sci.; 15(2). (2012).

Linsell, L. et al. Cognitive trajectories from infancy to early adulthood following birth before 26 weeks of gestation: a prospective, population-based cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child.; 103(4). (2018).

Huttenlocher, J., Haight, W., Bryk, A., Seltzer, M. & Lyons, T. Early Vocabulary Growth: relation to Language input and gender. Dev. Psychol. ;27(2). (1991).

Lenroot, R. K. & Giedd, J. N. Sex differences in the adolescent brain. Vol. 72, Brain and Cognition. (2010).

Jašarević, E., Howerton, C. L., Howard, C. D. & Bale, T. L. Alterations in the vaginal microbiome by maternal stress are associated with metabolic reprogramming of the offspring gut and brain. Endocrinology (United States) 156(9) (2015).

Doyle, O., Harmon, C. P., Heckman, J. J. & Tremblay, R. E. Investing in early human development: timing and economic efficiency. Econ. Hum. Biol. 7(1), 1–6 (2009).

Fitzmaurice, G., Laird, N. & Ware, J. Longitudinal and clustered data. In Applied Longitudinal Analysis p. xxvii–18 (2011).

Fitzmaurice, G. M., Laird, N. M. & Ware, J. H. Applied Longitudinal Analysis (Wiley, 2011).

Aylward, G. P. & Stancin T. Screening and assessment tools. In Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics 123–201. (Elsevier, 2005).

Acknowledgements

The researchers thank the ABC Hospital for their continuing support of the ELEMENT Cohort. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Lourdes Schnaas for laying the foundations of neurodevelopmental assessment in ELEMENT & PROGRESS.

Funding

Support for the ELEMENT and PROGRESS cohorts and all data described in this paper was made possible by National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) grants R01 ES007821, R01 ES014930, R01 ES013744, R01 ES021446, R24 ES028502, and P30 ES017885.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JF conceptualized the study, performed the literature review, interpreted the results, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. HLF formulated the research questions, performed most of the statistical analysis, interpreted the results, drafted sections of the manuscript and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SMM, EOV and CHC performed neurodevelopment assessments, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. VMR, YHG and GMS curated the data, performed initial statistical analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. BTV, HHB, KEP, ROW, and MTR critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

Research protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Public Health. The study was thoroughly explained to participating mothers, who signed an informed consent. A parent/guardian provided written informed consent for child participation. All methods were performed in accordance with all relevant Mexican guidelines and regulations, and the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fritz, J., Lamadrid-Figueroa, H., Muñoz-Rocha, T.V. et al. Cesarean birth is associated with lower motor and language development scores during early childhood: a longitudinal analysis of two cohorts. Sci Rep 14, 23438 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73914-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73914-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Long-lasting effects of pregnancy and childbirth on physical activity in early school-age children

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The Role of the human microbiome in neurodegenerative diseases: A Perspective

Current Genetics (2025)