Abstract

Treatments for reproductive disorders in women consist of hormone replacement therapy, which have negative side effects that impact health, spurring the need to understand new mechanisms to employ new therapeutic strategies. Bidirectional communication between sensory neurons and the organs they innervate is an emerging area of interest in tissue physiology with a relevance in reproductive disorders. We hypothesized that the metabolic activity of sensory neurons has a profound effect on reproductive phenotypes. To investigate this phenomenon, we utilized a murine model with conditional deletion of liver kinase B1 (LKB1), a serine/threonine kinase that regulates cellular metabolism in sensory neurons (Nav1.8cre; LKB1fl/fl). LKB1 deletion in sensory neurons resulted in reduced ovarian innervation from dorsal root ganglia neurons and increased follicular turnover compared to littermate controls. Female mice with this LKB1 deletion had significantly more pups per litter compared to wild-type females. Interestingly, the LKB1 genotype of male breeders had no effect on fertility outcomes, thus indicating a female-specific role of sensory neuron metabolism in fertility. In summary, LKB1 expression in peripheral sensory neurons plays an important role in modulating fertility of female mice via ovarian sensory innervation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian dysfunction contributes to 25% of impairments in fertility1. There is a well-established relationship between cellular metabolism and reproductive fitness: metabolic stress has profound effects on fertility. States of perturbed metabolism due to conditions such as obesity or prolonged malnutrition result in impaired ovulation and steroid hormone production2,3,4,5,6. This synergy of metabolism and reproductive function may arise from effects of liver kinase B1 (LKB1), a ubiquitously expressed serine/threonine kinase with multiple downstream targets involved in metabolism, cellular growth, and mitochondrial homeostasis7,8. We have recently used a novel mouse model with sensory neuron specific (Nav1.8) deletion of LKB1 to show that metabolism in sensory neurons is an important regulator of physiological responses to fasting in female mice9. Sensory neurons in female mice with conditional LKB1 knockout had significantly diminished metabolic activity & mitochondrial respiration after fasting compared to controls9. Interestingly, metabolic activity in male sensory neurons was not LKB1-dependent, suggesting a female-specific role of LKB1 signaling in murine sensory neurons9.

Several recent studies have demonstrated that communication between peripheral sensory neurons and the organs they innervate influences the functional activity of recipient organs. This phenomenon occurs in multiple tissue types, including the lymph nodes, adipose tissue, the gut, and dura mater of the brain10,11,12. Sensory neurons regulate aspects of local microenvironment at the site of innervation by detecting and responding to noxious and innocuous stimuli such as inflammation, metabolic state, tissue remodeling, and hormones13,14. Key studies have demonstrated an important role of peripheral sensory neurons in ovarian hormone output and ovulation15,16,17,18,19. Dysregulation in neuronal signaling and innervation in the ovary has been reported in human fertility disorders and in corresponding animal models17,20,21,22. Thus, obtaining a better understanding of the role of sensory neuron metabolism and innervation in the ovary should open new therapeutic channels for the treatment of fertility disorders.

The aim of the current study is to characterize the effects of LKB1 deletion in murine peripheral sensory neurons on fertility outcomes, ovarian growth and turnover, and innervation. We had observed that our mouse line with LKB1-null sensory neurons were prolific breeders. Interestingly, female breeders with LKB1-null sensory neurons had much larger litter sizes than their wild-type (WT) counterparts, independent of sensory neuron LKB1-deletion in male breeders. We assessed breeding metrics, estrous cycling, and serum estradiol levels. We then hypothesized that females with LKB1-null sensory neurons would have reduced sensory innervation in the ovary and an increased number of viable follicles compared to littermate controls. To understand the role of LKB1 in ovarian innervation, we performed retrograde tract tracing of ovarian innervation by DRG neurons. To further explore the mechanism of LKB1-deletion effects on ovulation and fertility, we measured follicle growth and development in the ovaries. In summary, LKB1 deletion from sensory neurons enhances fertility in female mice and presents a novel target for future development of therapeutics.

Results

Female mice with LKB1-null sensory neurons have enhanced fertility

We have previously used gene expression and ex vivo cellular metabolic measures to show that LKB1 expression is significantly reduced in DRGs of Nav1.8LKB1 mice compared to littermate controls9. Using RNA in situ hybridization, we further validated our sensory neuron specific LKB1 knockout (Nav1.8LKB1). In LKB1fl/fl (normal expression of LKB1) lumbar DRGs, ubiquitous expression of Stk11 mRNA (LKB1) is observed (Fig. 1a) whereas significantly reduced colocalization of Stk11 and Scn10a (Nav1.8) is observed in Nav1.8LKB1 lumbar DRG neurons (Fig. 1b).

Female mice with LKB1-null sensory neurons have enhanced fertility. RNA in situ hybridization of LKB1fl/fl (a) and Nav1.8LKB1 (b) lumbar DRGs targeting Scn10a (green) and Stk11 (magenta). Scale bar = 10 μm. (c) Average Stk11 puncta per Scn10a expressing 1 µm3 (LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 0.029 ± 0.0088, n = 5 females; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 0.0098 ± 0.0025, n = 8 females.) (d) Graphic depiction of our breeding schema. (e) Number of pups per litter (WT: mean ± SEM = 5.7 ± 0.47 viable pups, n = 31 litters from 10 females with 2–5 litters each; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 7.4 ± 0.45 viable pups, n = 35 litters from 11 females with 2–5 litters each; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 12.1 ± 0.8 viable pups, n = 31 litters from 11 females with 2–5 litters each). (f) Number of pups per litter per female breeder across the first five litters. (g) Dam age in weeks at the birth of their first litter (WT: mean ± SEM = 11.1 ± 5.6 weeks, n = 10 females; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 10.9 ± 0.57 weeks, n = 11 females; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 8.4 ± 0.38 weeks, n = 11 females). (h) Number of days between breeding initiation and the birth of their first litter (WT: mean ± SEM = 32.8 ± 3.4 days, n = 10 females; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 28.1 ± 1.9 days, n = 9 females; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 24.9 ± 1.4 days, n = 7 females). (i) Number of days between consecutive litters per female breeder (WT: mean ± SEM = 38.0 ± 4.96 days, n = 14 from 10 females with 2–5 litters each; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 27.9 ± 1.7 days, n = 21 from 11 females with 2–5 litters each; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 30.0 ± 2.2, n = 26 from 11 females with 2–5 litters each). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 by Student’s unpaired t test (c), ordinary one-way ANOVA (e, g, h, and i), or repeated measures two-way ANOVA (f).

We had anecdotal observations that breeders with LKB1-null sensory neurons (Nav1.8LKB1) had larger litters than wild-type (WT) (C57BL6/J) breeders. Our breeding schema was such that male and female mice have opposite genotypes, i.e., LKB1fl/fl or Nav1.8LKB1. To assess whether the increased litter sizes were due to the reproductive phenotype of the male or female breeders, we compared the breeding histories of (1) Nav1.8LKB1 females paired with LKB1fl/fl males, (2) Nav1.8LKB1 males paired with LKB1fl/fl females, and (3) WT males paired with WT females (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Table S1). When the breeding pairs included a Nav1.8LKB1 females, the number of pups per litter (Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 12.1 ± 0.8) was significantly greater than when the breeding pairs had a LKB1fl/fl female (LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 7.4 ± 0.45) (Fig. 1d,e; Table 1). Further, LKB1fl/fl females paired with Nav1.8LKB1 males produced similar litter sizes compared to WT x WT pairings (WT: mean ± SEM = 5.7 ± 0.47). We also compared litter sizes from WT mice of other inbred strains and the outbred ICR strain (Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S2). There were no differences in litter sizes between any of the WT mixed strain breeders, whereas outbred ICR breeders had significantly larger litter sizes than WT inbred mice. Litter sizes for Nav1.8LKB1 and ICR female breeders were similar.

To further understand the reproductive phenotype of Nav1.8LKB1 females, we determined the age at which female breeders had their first litter. All intentional breeders were paired between 5 and 6 weeks of age, but animals that were impregnated before weaning were also included. Nav1.8LKB1 females had their first litter at a significantly younger age than either LKB1fl/fl mice or WT mice of other strains (Fig. 1f; Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S2). Further, there were no significant differences in the number of days between breeding initiation and the first litter birth (Fig. 1g; Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1e, Supplementary Table S2). There were no significant differences in days to first litter or litter frequency between Nav1.8LKB1, LKB1fl/fl, and WT (C57) females (Fig. 1h,I, Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S2).

To determine if the enhanced fertility observed in Nav1.8LKB1 females is age-dependent, we assessed litter sizes in a small cohort of Nav1.8LKB1 and LKB1fl/fl breeders at 20 weeks of age at the time of breeding initiation (Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S2). All other parameters (breeding schema, housing conditions, handling) were matched to those used for young breeders. There was an age-dependent decrease in litter size for both genotypes; however, there were no differences in the mean number of pups per litter between LKB1fl/fl (mean ± SEM = 5.7 ± 1.0) and Nav1.8LKB1 (mean ± SEM = 7.4 ± 0.85) female breeders.

Females with LKB1-null sensory neurons have altered estrous cycling and lower serum estradiol

To investigate female-specific sources of variation in fertility, we assessed the estrous cycling patterns and serum estradiol levels in WT, LKB1fl/fl, and Nav1.8LKB1 females as both measures are directly related to fertility potential in females. To test for an association between altered breeding rate and shifts in estrous cycling, we analyzed the amount of time the animals were spending in each phase. Compared to LKB1fl/fl females, Nav1.8LKB1 females spent less time in proestrus, whereas WT and LKB1fl/fl mice had similar proestrus duration (Fig. 2a; Table 2). LKB1fl/fl and Nav1.8LKB1 females both spent more time in estrus than WT females, but without any group differences in metestrus or diestrus (Fig. 2b–d; Table 3). There were no differences in cycle length (Fig. 2e; Table 2). Measurements of serum estradiol levels across the estrus cycle found normal estradiol level flucuations in LKB1fl/fl females (Fig. 2f). The data indicated that WT and Nav1.8LKB1 females had lower estradiol than LKB1fl/fl littermates during diestrus (Fig. 2f; Table 2).

Females with LKB1-null sensory neurons have altered estrous cycling and lower serum estradiol levels. Estrous cycling was tracked for ten days with twice daily vaginal lavage sample collection. The percentage of samples for each mouse in (a) proestrus, (b) estrus, (c), metestrus, and (d) diestrus across the entire collection period. (a) Proestrus: (WT: mean ± SEM = 13.5 ± 1.7%; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 17.9 ± 1.97%; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 10.9 ± 1.6%. (b) Estrus: (WT: mean ± SEM = 23.96 ± 3.8%; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 40.8 ± 4.3%; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 42.2 ± 4.5%. (c) Metestrus: WT: mean ± SEM = 22.9 ± 3.3%; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 17.8 ± 2.5%; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 19.2 ± 1.8%. (d) Diestrus: WT: mean ± SEM = 39.6 ± 4.8%; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 23.5 ± 4.8%; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 27.7 ± 3.9%. (e) Total cycle length (days between proestrus smears): (WT: mean ± SEM = 4.5 ± 0.27 days; LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 4.9 ± 0.33 days; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 5.0 ± 0.36 days. For (a–e), WT: n = 12 females; LKB1fl/fl: n = 17 females; Nav1.8LKB1: n = 17 females. (f) Serum estradiol (pg/mL) levels across the estrous cycle. (WT: n = 5–7 biological replicates per phase; LKB1fl/fl: n = 6–13 biological replicates per phase; Nav1.8LKB1: n = 7–12 biological replicates per phase; all biological replicates were assayed in duplicate). The dotted line indicates the mean serum estradiol (53 pg/mL) for age-matched male mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001, ****p < 0.0001 by ordinary one-way ANOVA (a–e) or ordinary two-way ANOVA (f).

LKB1 in peripheral sensory neurons promotes ovarian innervation

We performed retrograde tracing from the ovary in WT, LKB1fl/fl, and Nav1.8LKB1 mice by injecting with Fluorogold and collecting DRGs ten days later at both thoracic (T7–T13) and lumbar (L1–L5) levels of the spinal cord (Fig. 3a). Assessment of the total number of fluorogold-labeled neurons per DRG in WT (C57) mice showing fluorogold labelling in thoracic (T10–T13, especially T13) and lumbar (L1) DRGs (Fig. 3b), but no labelling outside those spinal levels. WT mice had greater innervation than LKB1fl/fl mice from T12–L1, but comparable fluorogold labelling staining at T10–T11. Female Nav1.8LKB1 mice had relatively low fluorogold staining in DRG at levels T12–T13 and L1, with no differences in fluorogold staining in T10–T11 compared to WT (Fig. 3B; Table 3). There were no differences in the total number of Nav1.8 neurons (Supplementary Fig. 3a).

LKB1 in peripheral sensory neurons promotes ovarian innervation. (a) Graphic schema of the experimental methods used for retrograde tracing of ovarian innervation. (b) The number of fluorogold-positive neurons per DRG. (WT: n = 5 mice; LKB1fl/fl: n = 4 mice, Nav1.8LKB1: n = 4 mice.) For each group, we obtained n = 5 technical replicates per DRG. (c) The number of Nav1.8-positive neurons with positive fluorogold signal per DRG. (WT: n = 5 mice; LKB1fl/fl: n = 4 mice, Nav1.8LKB1: n = 4 mice.) For each group, we obtained n = 5 technical replicates per DRG. (d) The number of TH-positive neurons with positive fluorogold signal per DRG. (WT: n = 5 mice; LKB1fl/fl: n = 4 mice, Nav1.8LKB1: n = 4 mice.) For each group, we used n = 5 technical replicates per DRG. (e-f) Representative confocal microscopy (30X) of fluorogold (red), Nav1.8 (green), and TH (purple) immunohistochemistry in the T12 DRG from LKB1fl/fl (e) and Nav1.8LKB1 (f) females. Scale bar = 50 μm. Arrows indicate positive fluorogold signal. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001, ****p < 0.0001 by repeated measures two-way ANOVA (d–f).

We then assessed the colocalization of Nav1.8 and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) sensory neurons with retrograde fluorogold staining. WT (C57) mice had increased Nav1.8/fluorogold colocalization at lower DRGs (T13 and L1), with less contribution from T10-T12 DRGs, whereas LKB1fl/fl mice have similar numbers of Nav1.8/fluorogold double-labelled neurons across all DRGs. Nav1.8/fluorogold colocalization was significantly reduced in Nav1.8LKB1 females compared to WT (C57) (T13 and L1) and LKB1fl/fl (T12, T13, and L1) females (Fig. 3c; Table 3). There were no differences in the number of TH/fluorogold double-labelled neurons between WT, LKB1fl/fl, and Nav1.8LKB1 mice, with the exception that Nav1.8LKB1 mice had significantly fewer TH/fluorogold neurons at T12 compared to WT, but not LKB1fl/fl mice (Fig. 3d; Table 3). When comparing the number of fluorogold- and Nav1.8 double positive neurons as a percentage of all Nav1.8 + neurons, there were still significantly fewer fluorogold-positive neurons in Nav1.8LKB1 mice compared to WT (T13 and L1) and LKB1fl/fl (T13) mice (Fig. 3e,f, and Supplementary Fig. 3b). When comparing the number of fluorogold- and TH double positive neurons as a percentage of all TH + neurons, Nav1.8LKB1 mice had fewer fluorogold positive neurons at T10 compared to WT (C57) only (Supplementary Fig. 3c). No other differences were observed.

Uterine and testes/epididymis weights in females and males

Although the increased litter sizes were observed specifically when female Nav1.8LKB1 breeders were paired with LKB1fl/fl males, we wanted to assess whether the removal of LKB1 from sensory neurons had any impact on overt physiology in both male and female mice. As reported previously9, there were no overt differences in body weight between strain or genotype groups in either male or female mice. Age matched WT (C57) females had significantly lower reproductive organ weight compared to LKB1fl/fl and Nav1.8LKB1 females. There was no such difference between LKB1fl/fl and Nav1.8LKB1 females. For male mice, there were no differences in testes and epididymis weights (Supplementary Fig. S2, Supplementary Table S3).

Histological analysis of ovary morphology and periovarian fat in Nav1.8LKB1females

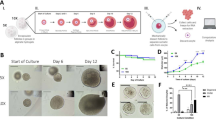

Because Nav1.8LKB1 female mice have significantly larger litters than LKB1fl/fl littermate controls, we performed a histological analysis on the ovaries and periovarian fat to investigate ovarian size, it’s surrounding fat, and the life cycle of the follicles (Fig. 4a). Nav1.8LKB1 ovaries are significantly larger compared to LKB1fl/fl ovaries (Fig. 4b; Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in the number of corpora lutea (CL) (p = 0.0669) (Fig. 4c; Table 4). We then assessed the number of follicles at each overall growth stage (independent of estrous cycle phase) and found that Nav1.8LKB1 mice had significantly more growing follicles (primary and secondary) and total follicles (sum of all types) compared LKB1fl/fl mice (Fig. 4d and e; Table 4). We attribute the increase in ovary size to the significantly increased number of follicles in Nav1.8LKB1 ovaries compared to LKB1fl/fl.

Histological analysis of ovary morphology in Nav1.8LKB1females. (a) Graphic depiction of assessment of the follicular life cycle. (b) Ovary size as measured immediately following extraction (LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 2.6 ± 0.12 mm, n = 8 females; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 3.2 ± 0.27 mm, n = 6 females). (c) Number of corpora lutea (CL) per ovary (LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 2.0 ± 0.45 CL, n = 6 females; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 2.1 ± 0.55 CL, n = 8 females). (d) Representative images of H&E-stained ovary sections from females in estrus. Scale bar = 100 μm. *= CL. (e) Number of follicles at each stage. (LKB1fl/fln = 12 females; Nav1.8LKB1n = 8 females) For each group, n = 5–10 technical replicates/sections. (f) Representative images of H&E-stained perigonadal adipocytes. Scale bar = 20 μm. (g) Size (area in µm2) of perigonadal adipocytes. (LKB1fl/fl: mean ± SEM = 1531 ± 121.8 µm2, n = 14 females; Nav1.8LKB1: mean ± SEM = 1943 ± 104.2 µm2, n = 15 females). For each group, n = 5–10 technical replicates (sections) with a minimum of 60 cells analyzed per section. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0001 by unpaired two-tailed t-test (b, c, g) or ordinary two-way ANOVA (e). Open symbols indicate females in proestrus or estrus; closed symbols indicate females in metestrus or diestrus (b–d).

Although we have previously shown that LKB1fl/fl and Nav1.8LKB1 female mice have similar whole-body metabolism9, we were interested to determine if changes in perigonadal adipose would present with enhanced fertility in Nav1.8LKB1 females. Nav1.8LKB1 females had larger perigonadal adipocytes than LKB1fl/fl mice, despite comparable body weight (Fig. 4f,g; Table 4); However, we did not assess the weight of the total fat pad.

Follicular dynamics across the estrous cycle in Nav1.8LKB1 ovaries

To further examine alterations in follicular development in the Nav1.8LKB1 ovary, we analyzed the number and size of follicles in H&E-stained whole ovary sections across each phase of the estrus cycle. We observed Nav1.8LKB1 females had significantly more secondary follicles than LKB1fl/fl mice, regardless of cycle phase (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S4). Primary follicles in Nav1.8LKB1 mice were significantly larger, although secondary follicles did not differ in size (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S4). Overall, Nav1.8LKB1 females had more pre-antral follicles than LKB1fl/fl females. There were no group differences observed in the size of pre-antral follicles (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S4), nor did we see any differences in the number or size of antral follicles (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S4). We next measured atretic follicles to discern whether Nav1.8LKB1 females exhibited an altered pattern of follicular selection for ovulation. While Nav1.8LKB1 mice had slightly more atretic follicles during proestrus/estrus, LKB1fl/fl mice had significantly more atretic follicles during diestrus (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Table S4).

To assess whether the observed differences in follicle size were due to precursor oocyte size or to effects of the support cell network, we measured oocyte size in H&E-stained ovary sections. There were no group differences in the size of oocytes in primary follicles, pre-antral follicles, or antral follicles at any phase of the estrous cycle; however, oocytes from secondary follicles were smaller in Nav1.8LKB1 females (Supplementary Fig. S5, Supplementary Table S5).

Discussion

We present the novel finding that modulation of sensory neurons via removal of LKB1 directly affected breeding in female mice via changes in estrous cycle, ovarian growth, and follicular development. Removal of LKB1 from sensory neurons resulted in an increase in litter size and decrease in the breeder age for the first pregnancy. These reproductive changes were only seen in female breeders with LKB1-null sensory neurons. Thus, when male mice with LKB1-null sensory neurons were paired with wild-type (LKB1fl/fl) females, litter sizes were comparable to those from WT (both sexes) breeding pairs. Our retrograde labelling studies confirmed that Nav1.8 neurons directly innervate the ovary from the DRG, and that this ovarian innervation declines in the absence of LKB1. These findings show a sex-specific interaction between LKB1 in sensory neurons and fertility specifically in female breeders.

The role of sensory neurons in modulating reproduction and ovarian function is not well understood. The primary sensory contribution to the ovary is thought to be calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-containing nerve fibers23,24,25. CGRP, a neuropeptide expressed by peptidergic sensory neurons, has important roles in mediating neurogenic inflammation and vasodilation, both of which regulate steroidogenesis and follicle development19,26,27. CGRP and Nav1.8 have up to 80% colocalization rodent sensory ganglia28. These neurons have direct effects on tissue physiology by detecting changes in the target tissue environment9,10,11,29. Further, activated Nav1.8-expressing neurons from the nodose ganglia release the neuropeptide CGRP30. Vagus and DRG Nav1.8 neurons may have differing effects on reproductive physiology. While DRG neurons primarily detect and respond to tissue damage and inflammation, vagal neurons mediate the autonomic nervous system31,32,33,34. The presence of Nav1.8 neurons in both the vagal nodose ganglia and DRG suggests that sensory neurons likely play a previously unappreciated role in the regulation of reproduction and fertility35.

LKB1 pathways present a promising therapeutic for fertility disorders36,37. LKB1 has multiple downstream targets that regulate cellular metabolism and function7,8,38, notably AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), a highly conserved kinase that senses and responds to changes in cellular energy levels39,40,41. LKB1/AMPK signaling increases ATP production by promoting glucose metabolism and lipid oxidation8. Without LKB1, sensory neurons cannot shift energy production pathways during metabolic stress9. LKB1 also regulates mitochondrial homeostasis, which is essential for axon growth; neurons lacking LKB1 have reduced axon length and branching42,43,44,45,46,47. Further, LKB1 regulates mitochondrial trafficking to axon terminals and presynaptic neurotransmitter release48,49. Changes in signal transduction and neurotransmitter release may accompany the reductions in ovarian innervation observed in female mice with LKB1-null sensory neurons. Likely sensory neurons lacking LKB1 are less able to detect and communicate the metabolic status of the ovary, and thus exert attenuated regulation over follicle growth and ovulation.

The relationship between metabolism and reproduction has been intensively studied, particularly as fertility disorders often coincide with metabolic abnormalities3,50,51. Significant shifts in nutritional availability, energy stores, and metabolic demand divert energy use away from reproduction and towards survival functions52. Metabolic changes during high-fat diet consumption manifest in altered ovarian function even in the absence of overt weight gain and obesity53,54,55. Because sensory neurons lacking LKB1 have a reduced capability to innervate tissue and an impaired response to metabolic stress, mice with LKB1-deficient sensory neurons may have impaired ability to detect and respond to changes in energy demand9. Our previous study in LKB1-deficient mice did not show any overt differences in weight loss and regain after a 24-h fast; however, female Nav1.8LKB1 mice showed prolonged sensitization of peripheral sensory neurons compared to LKB1fl/fl littermate controls9. Those results, together with current observations that Nav1.8LKB1 females have larger perigonadal adipocytes and enhanced fertility, provide further evidence that sensory neurons play an essential role in metabolic stress responses. Interestingly, ablation of adipose-innervating sensory neurons results in increased fat mass and lipogenesis-promoting gene upregulation12. The sex-specific findings in our study highlight the need for additional research into the mechanisms whereby females regulate and respond to metabolic stress, as further understanding of these processes may pave the way for therapeutic developments for treating female fertility.

Interactions between LKB1 and sex hormones, particularly 17β-estradiol (E2), and their receptors may underly the present findings in female mice - and in our previous work. While not yet reported in neurons, several studies have observed a link between LKB1 activity and estrogen receptor (ER) signaling in other cell types. ERα and ERβ have markedly differing physiological effects: ERα promotes cellular proliferation and prevents weight gain and insulin resistance, while ERβ has anti-inflammatory effects and often antagonizes ERα responses56,57,58. Of the two subtypes, ERα has the best-established interaction with LKB159. Subtype-specific expression of ERs has been observed in DRG neurons, with ERα expression predominating in small to medium diameter DRG neurons and ERβ expression in small subpopulations of small, medium, and large diameter DRG neurons60. In our study, we observed significantly reduced diestrus serum estradiol levels during in Nav1.8LKB1 female mice; however, levels in other phases of the cycle were similar to wild-type female and male mice. While sensory neurons are not directly responsible for steroid hormone production, the lack of LKB1 in these cells likely modulates their response to circulating hormones such as E2.

A limitation of our study is that we made our assessments of ovarian innervation and histology in non-pregnant mice. The uterus also has sensory innervation and likely receives a contribution from DRG neurons61,62,63,64. Thus, there remains much to be established regarding the dynamics of sensory feedback in relation to fertility. Our goal was to focus on the relationship between ovarian physiology and sensory neurons in relation to female fertility; however, we acknowledge that there is much to be gained from investigating the role of sensory neurons in the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy.

In conclusion, modulating the metabolic profile of sensory neurons via deletion of LKB1 resulted in a phenotype of enhanced fertility in female mice, increased litter sizes, and younger pregnancies. Breeding a male with LKB1-null sensory neurons with a WT female did not alter fertility and produced similar litter sizes to wild-type breeders (Fig. 1C). Thus, this sex-specific reproductive phenotype highlights a novel role for sensory neurons in modulating fertility. Nav1.8-expressing sensory neurons innervate the ovary from the DRG, but this innervation is reduced in the absence of LKB1. These data support existing literature showing that LKB1 is essential for proper axonal growth and innervation, which we now extend to the case of peripheral sensory neurons. This LKB1 expression in sensory neurons present a promising target for understanding neuronal regulation of female fertility.

Materials and methods

Animals

Unmated female mice (6–10 weeks old) of two different strains were used for all experiments, except for breeding studies (see below). WT C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (stock no. 000664) and used to establish our in-house breeding colony at UT-Dallas. Transgenic mice (C57BL/6) expressing NLS-Cre recombinase under control of the Scn10a (Nav1.8) promoter were obtained initially from Professor John Wood (University College London) but are commercially available from (Ifrafrontier, EMMA ID: 04582). Although most Nav1.8-expressing neurons are nociceptors (C-fibers), Nav1.8 is expressed in small diameter neurons in the dorsal root ganglia, trigeminal ganglia, and nodose ganglia and can therefore be broadly identified as peripheral sensory neurons28,35,65. Previous characterization of these mice demonstrated normal electrophysiological properties and expression of Cre recombinase in approximately 75% of Nav1.8-positive neurons in the DRG29,65. Genetically modified LKB1 flox mice (FVB;129S6-Stk11tm1Rdp/NCI; LKB1fl/fl), which have loxP sites flanking exons 3–6 of the Stk11 gene, were purchased from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (Strain No. 01XN2). LKB1fl/fl mice were bred with Nav1.8cre heterozygous mice to produce cell specific LKB1 knockouts (Nav1.8LKB1)9,66. Previous characterization of these mice showed significantly reduced Stk11 gene expression in DRGs from Nav1.8LKB1 male and female mice compared to cre-negative littermate controls9. Further, ex vivo assessment of sensory neuron bioenergetics showed diminished mitochondrial function in the absence of LKB1. Our breeding strategy was such that Nav1.8LKB1 animals were homozygous for the LKB1 floxed gene (LKB1fl/fl) and expressed one copy of Nav1.8cre. Littermate controls (LKB1fl/fl) expressed two copies of the LKB1 floxed gene and had normal LKB1 expression in the absence of Nav1.8cre9. WT mixed strain mice (C57BL/6J x FVB:129 S) were bred in-house and used as a strain control for fertility assessments. ICR (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) breeders served as an outbred strain control. Fertility metrics from ICR breeders were generously provided by Theodore Price at the University of Texas at Dallas.

All animals used in this study were bred in-house and group housed (3–5 per cage) in polypropylene cages. Animal housing rooms were maintained at a temperature of 21 ± 2 °C under a 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 6 AM and off at 6 PM). Mice had ad libitum access to water and standard rodent chow (LabDiet ProLab RMH 1800). All procedures used in this study were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines67,68. All procedures used in this study were approved by the University of Texas at Dallas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols 16-07 (breeding) and 17-10 (experiment).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Animals were weaned between 21–28 days of age, at which time a tail clip biopsy (~ 1 mm) was collected. DNA was extracted from tail clips by suspension in 75 µl extraction buffer (25 mM NaOH, 0.2 mM EDTA in ddH2O) with incubation at 95 °C for one hour. An equal amount of neutralization buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 5.5) was added following incubation. DNA samples were stored at − 20 °C until genotyping. PCR was performed using JumpStart REDTaq Ready Mix (Sigma, Cat#P0982-800RXN) and the primers listed below. Genotyping for Nav1.8cre was performed as a single reaction, whereas LKB1 LoxP and WT reactions were performed separately. The LKB1-flox gene was amplified using the primer pair LKB1rdp_COM 5’-GAG ATG GGT ACC AGG AGT TGG GGC T-3’ and LKB1rdp_WT 5’- GGG CTT CCA CCT GGT GCC AGC CTG T-3’. The LKB1 WT gene was amplified using the primer pair LKB1rdp_COM 5’-GAG ATG GGT ACC AGG AGT TGG GGC T-3’ and LKB1rdp_MUT 5’-TCT AAC GCG CTC ATC GTC ATC CTC GGC-3’. The Nav1.8cre gene was amplified using the custom primer pair newNAV-WT-Fwd 5’ GAT GGA CTG CAG AGG ATG GA-3’ and newNAV-Cre-Rev 5’-CGT ATA TCC TGG CAG CGA TC -3’. The Nav1.8 WT gene was amplified using the custom primer pair newNAV-WT-Fwd 5’ GAT GGA CTG CAG AGG ATG GA -3’ and newNAV-WT-Rev 5’-GGT GTG TGC TGT AGA AAG-3’. Samples were run on a 2% agarose (VWR, Cat# MPN605-500G) and 1× Tris-Acetate-EDTA (TAE) gel and imaged using a ChemiDoc apparatus (BioRad) and ImageLab. DNA Ladder (100 bp, Thermo Scientific GeneRuler 100 bp) was used for size determination. The Nav1.8cre and Nav1.8 WT bands were at 800 and 500 bp, respectively, whereas the LKB1 mutant and LKB1 WT bands were at 300 and 220 bp, respectively. In the LKB1 WT reaction, a band at 600 bp appeared in the presence of LoxP sites (Supplementary Fig. S1)66.

RNA in situ hybridization

We performed RNA in situ hybridization on fresh frozen DRGs from LKB1fl/fl and Nav1.8LKB1 mice to confirm the deletion of LKB1 from Nav1.8 neurons. RNAscope in situ hybridization assay (Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit version 2) was performed following the Advanced Cell Diagnostics (ACD) protocol using the following adjustments. Samples were incubated in fresh 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) at 4 °C for one hour and a 30-s Protease IV digestion was used for all experiments. The fluorophores used were from Akoya Biosciences at a 1:1500 dilution: TSA Plus Fluorescein (Cat# NEL741001KT) for C1 and TSA Plus Cyanine 5 (Cat# NEL745001KT) for C3. We used the following probes: Mm-Scn10a (Cat#426011) and Mm-Stk11-C3 (Cat#469211-C3). The RNAscope 3-plex negative control probe (Cat#320871), which targets the bacterial gene DapB, was used to confirm probe specificity and control for background staining. The target region for the probe used (ACD Bio Cat No. 469211-C3) is base pairs 982–1930 of the stk11 gene (Accession No. NM_011492.4), which spans exons 2–8 and therefore includes exons 3–6 where the KO occurs. To check for RNA and tissue quality, a positive control probe that targets a highly expressed transcript (Ubiquitin C) in all cell types was used (Mm-UBC, Cat#310771).

Breeding history

Intentional breeding pairs were initiated when animals were between 5 and 6 weeks of age, except for a small cohort (analyzed separately) that was initiated at 20 weeks of age. We also included data from females that were impregnated prior to weaning in some analyses. All breeding pairs are set up as trios, with one male paired with two females, to promote pair nursing, cross fostering, and pup health. Per facility and husbandry guidelines, litters older than ten days were separated with their respective dam in cases of overcrowding. Our breeding strategy was such that Nav1.8LKB1 males were paired with LKB1fl/fl females or LKB1fl/fl males with Nav1.8LKB1 females (Fig. 1c). WT breeding pairs (C57BL6/J, mixed strain, and ICR) had both male and female WT breeders. At no point were male breeders removed from the breeding cages.

Breeders were carefully tracked by experimenters to ensure accuracy of breeding data. Breeders were handled only by experimenters, with glove changes between cages to reduce animal stress by minimizing scent transfer. Breeding cages were cleaned exclusively by familiar experimenters. Per facility and husbandry guidelines, all cages were provided with standard rodent bedding, nesting material for enrichment, and a red igloo nesting box. When initiating breeding pairs, mice were placed in a clean cage with fresh food, bedding, and nesting material. Female estrous cycles were not tracked prior to the initiation of breeding pairs.

All breeding information was collected for individual female breeders: data was never averaged for two females in the same trio. All genotypes referenced in breeding data refer to the genotype of the female breeder. The age at first litter was defined as the age of the female breeder on the date of birth of her first viable litter. Conversely, days to first litter was defined as the number of days between breeding initiation to the birth of the first viable litter per female in each breeding pair. Litter sizes were determined by counting the number of viable pups born from each female and were tracked for the first five litters for each female. Rare occurrences (< 1%) of non-viable pups (death due to cannibalism, maternal neglect, etc.) were not counted for this study. Litter frequency was measured as the number of days between consecutive viable litters for each female breeder. Breeding schematics can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Estrous cycling

Estrous cycling was assessed over a ten-day period via cytology of vaginal lavage samples. Starting at six weeks of age in non-mated female mice, samples were collected twice per day between 8 and 10 a.m. and 5–7 p.m. for ten consecutive days. Vaginal lavage samples were collected using previously described methods by experimenters blinded to genotype69,70,71. To summarize, vaginal lavage with 20 µL sterile saline was collected onto charged microscope slides (Fisher, Cat#12-544-7) and allowed to air dry overnight. Samples were stained with toluidine blue for visualization of cells and imaged using brightfield microscopy. Classification of cycle phase was performed by experimenters blinded to genotype. Phases were determined by cell type and density present in the stained vaginal lavage samples. Proestrus smears consist primarily of nucleated epithelial cells, whereas estrus smears consist primarily of anucleated or “cornified” epithelial cells that appear in high density and often in clumps. Metestrus smears consist of a mixture of anucleated epithelial cells and neutrophils, with few little nucleated epithelial cells, and are usually of high cell density. Diestrus smears consist primarily of neutrophils and range from moderate to low cell density. Transitory phases were marked as such. For example, a smear with an equal number of nucleated and anucleated epithelial cells would be classified as a proestrus-estrus transition and denoted “P/E”. Complete cycle tracking information can be found in Supplementary Table S6. To compare estrous cycle tracking between groups, each phase is represented as a percentage, where the number of samples in each phase was divided by the total number of collected samples per mouse. For example, if two of 20 samples over the ten-day period were in proestrus, this would be represented as 10%. Cycle length was measured as the number of days between consecutive proestrus smears.

Estradiol ELISA

Serum was isolated from tail blood collected in the morning (9 a.m.–11 a.m.) immediately following vaginal lavage collection. Tail blood was collected using microvette EDTA-coated tail vein capsules (Sarstedt, Cat#16.444.100). Serum was isolated via centrifugation at 14,000 RPM for 15 min at 4 °C. Serum samples were immediately stored at − 80 °C. Quantification of serum estradiol was performed using the Crystal Chem Estradiol ELISA kit (Cat#80548) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay has a detectability range of 5–1280 pg/mL and a CV of 10%. The samples were assayed at a 1:3 dilution in 0 pg/mL standard buffer.

Retrograde tracing

To determine the extent of sensory innervation to the ovary, we performed retrograde tracing studies on WT, LKB1fl/fl, and Nav1.8LKB1 females. Fluorogold (Hydroxystilbamidine, Biotium, Cat#80014) was diluted in ddH2O to a 0.4% solution and stored at 4 °C in opaque/black tubes (Black Beauty Microcentrifuge Tubes, Argos Technologies, 1.5mL, Cat#47751-688)72,73,74,75. All surgical tools were autoclaved before use. During the surgery, tools were sterilized using a Dry Glass Bead Sterilizer (Stoelting, Cat#50287) and 100% anhydrous ethanol (Decon Laboratories, CAS#64-17-5, Cat#2701). The mice were heavily sedated using isoflurane (5% induction, 3% maintenance). The surgical site was shaved and cleaned with 10% povidone iodine prep solution (USP equivalent to 1% available iodine, Dynarex, Cat#1416) and 100% anhydrous Ethanol. Via laparotomy, the skin and peritoneum were incised with a #10 scalpel blade (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#S2646) and the ovary and perigonadal fat pad were exposed. A 5 µL volume of the 0.4% Fluorogold solution was injected into the left ovary using a 30-gauge needle mounted on a 25 µL Hamilton syringe. The peritoneum was sutured closed using a 5 -0 silk suture (VWR, MV-682) and the skin was then closed using an AutoClip Kit with 9 mm clips (Fine Science Tools, Cat#12020-00). Mice were given a subcutaneous injection of Gentamicin (10 mg/kg, sterile-filtered, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#G1272-100 mL) as a preventative antibiotic into the nape of the neck with a 25-gauge needle using a 1 mL syringe and returned to their home cages to recover. Mice were also given 0.125 mg Meloxicam (Bio-Serv, Cat#M275-050D) for post-surgical pain and monitored daily for infection or malaise.

Immunohistochemistry

For retrograde tracing experiments, ten days following Fluorogold injection, mice were euthanized following the University of Texas at Dallas IACUC procedure. Bilateral DRGs (T7–L5) were collected and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 4–6 h. DRGs were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) for 48 h and frozen in OCT. Frozen DRGs were serially sectioned on a cryostat at 14 μm and mounted onto charged microscope slides. Each slide contained ipsilateral and contralateral DRG from the same level (i.e., all L1 samples) from each group. Frozen DRG sections were stored at − 20 °C prior to immunohistochemistry. All samples were sectioned such that every fifth section was represented on one slide, spanning the entire DRG. Frozen sections were dried out for 15 min at room temperature (RT) prior to rehydration of the samples with 1× PBS. For antigen retrieval, rehydrated sections were incubated in heated 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (in 1× PBS, pH 6.0; Sigma, Cat#C8532-500G) for 5 min, three times in succession. Sections were then incubated in blocking buffer (3% normal goat serum (Gibco, Cat#16210-072), 2% bovine serum albumin (VWR, Cat#97061-416), 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, Cat#X100), 0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#P1379), and 0.1% sodium azide (Sigma, Cat#RTC000068) in 1× PBS, pH 7.4) for two hours at RT followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C in a primary antibody solution consisting of anti-Nav1.8 (NeuroMab, Cat#75–166, mouse monoclonal IgG2a, RRID: AB_2183861), anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (Aves Labs, Cat#TYH, chicken polyclonal IgG, RRID: AB_10013440), and anti-Fluorogold (Millipore, Cat#AB153, rabbit polyclonal IgG, RRID: AB_90738) diluted at 1:500 in blocking buffer. Sections were then washed three times in 1× PBS + 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T) and incubated in secondary antibody solution (Goat anti-mouse IgG2a Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Cat# A21131, RRID: AB_2535771), Goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen, Cat#A11001, RRID: AB_2535813), and Goat anti-chicken IgG Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen, Cat#A32933, RRID: AB_2762845) diluted at 1:1000 in blocking buffer for two hours at RT, protected from light. Sections were then washed three times in 1× PBS-T, incubated in DAPI (1:5000) for one minute, washed once with 1× PBS, and mounted with Gelvatol. Mounted sections were stored at RT overnight in dark and then stored at 4 °C until imaging.

Image acquisition and analysis for fluorescent microscopy

Images for analysis were acquired using the Zeiss Axio Observer Microscope equipped with an Axiocam 503 B/W monochrome camera (Carl Zeiss, Inc.). Epi-fluorescent z-stack images were taken with 20× objective (NA 0.8) 0.227 μm/pixel using ZEN2.5 Pro software (Carl Zeiss, Inc.). Image analysis was performed on five serial 14 μm sections per DRG using the Olympus CellSens Software using the “Count and Measure” feature. Only cells with visible nuclei (DAPI) were measured to avoid overcounting duplicate cells. First, the total number of neurons with fluorogold signal were counted. Then, we counted the fluorogold-positive neurons that colocalized with either Nav1.8+ or TH+ immunostaining. Experimenters were blinded to genotype for all image acquisition and analysis. Representative images for publication were acquired using the Olympus FV300RS Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope using the 30× objective (UPLSAPO30x; UPLSAPO N 30X SI OIL, NA 1.05, WD 0.8 mm w/ correction collar) using the 3D Z-stack mode on the Complete Fluoview Acquisition Software.

Tissue collection and processing

For histology experiments, estrous cycle phase was determined using the measures described above immediately prior to tissue collection. For tissue collection, mice were euthanized following the University of Texas at Dallas IACUC procedure and the ovaries and surrounding perigonadal fat were collected and post-fixed in 4% PFA (made in 1× PBS) for 4–6 h. Ovary size (both ovaries) was measured immediately following extraction using a caliper by an experimenter blinded to genotype. One ovary per mouse together with its perigonadal fat pad was embedded in paraffin and cut into 10 μm-thick sections, which were mounted on charged microscope slides. For histological analysis of ovarian and adipocyte structure, paraffin embedded sections were stained with Hematoxylin (Sigma, Cat#HHS16) and Eosin Y Solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#318906) (H&E).

Image acquisition and analysis of ovaries and adipocytes

H&E-stained tissue sections were imaged via brightfield microscopy using the Olympus VS120 Virtual Slide Microscope equipped with the 40x objective (NA 0.95, 0.33 μm/pixel). Sections were mounted serially, and every fifth slide was used for analysis (5–10 sections per ovary) using the Olympus cellSens Software. Sections were analyzed by experimenters blinded to estrous cycle phase and genotype.

Follicles were classified based on a modified scheme originally proposed by Pedersen & Peters (1986) and further described in Myers et al., 2004 and Westwood, 200876,77,78. In brief, follicles were initially classified into the following types: growing (primary or secondary), maturing (pre-antral or antral) or atretic (degenerating). A phase dependent analysis of each follicle type can be found in the supplementary data. Oocytes with a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells were classified as primary follicles. Oocytes with multiple surrounding layers of granulosa cells were classified as secondary follicles. Oocytes surrounded by a defined zona granulosa and theca without the formation of a follicular antrum were classified as pre-antral follicles, whereas those with a formed follicular antrum were classified as antral follicles. Atretic follicles were determined by the presence of apoptotic cells. To ensure follicles were not counted more than once, only follicles with a visible nucleus were used for analysis. For primary and secondary follicles, the raw count was normalized by the section thickness (10 μm) and frequency of sections (every fifth section) to give a total follicle number for each ovary. For pre-antral, antral, and degenerating follicles, the raw counts obtained were used due to the larger size of these follicular types. Adipocytes were quantified by measuring the area of at least 60 randomly selected adipocytes per section in the perigonadal fat pad.

Image acquisition and spots/volume analysis in IMARIS for in situ hybridization

To quantify the effectiveness of LKB1 knockout in lumbar DRGs of Nav1.8LKB1 mice compared to LKB1fl/fl mice, images were acquired on the Zeiss AxioObserver 7 Microscope equipped with an Axiocam 503 B/W357 monochrome camera (Carl Zeiss, Inc) or Olympus FV3000 confocal microscope. Image acquisition settings were determined using the negative control samples as reference following ACD assay protocol (Supplementary Fig. S6). Z-stack images were taken using a 40x magnification. We utilized imagining and machine learning software, IMARIS (v. 10.1.0, Oxford Instruments), to quantify the number of Stk11 puncta in Scn10a expressing neurons. This was accomplished by generating a 3-D model of the Scn10a positive regions, which visualized Nav1.8 expressing sensory neurons, and quantifying the Stk11 puncta present in the Scn10a expressing space. All images were analyzed after conversion from .tif to .ims filetype. Z-stack images were reconstructed in Imaris and 3-D volumes were generated via the surfaces feature by drawing regions of interest around Scn10a positive neurons in individual slices of the z-stack. Imaris’ machine learning spots analysis was utilized to count Stk11 puncta in Scn10a positive regions by subdividing the Stk11 puncta into two discrete groups: Stk11 puncta that overlap with Scn10a positive regions, and Stk11 puncta that do not overlap with Scn10a positive regions. Following four successive iterations of machine learning to ensure accuracy, images were subjected to a spots analysis with qualification criteria of 1 μm estimated diameter, and analysis channel set to Stk11. Exclusion was placed on spots which lie outside of the region of interest by setting the lower bound to ‘off’ and upper bound to 1. Machine learning consisted of an average of 4 iterations of manual classification of puncta to correct any false positives (i.e., any puncta outside of the Scn10a region). Deviation in spot counts of the same image between multiple analysis with the same iteration and criteria were negligible.

Statistics

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.4.0 software. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analysis. One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used to analyze datasets for breeding metrics except for litter sizes over time, which was analyzed using Ordinary Two-Way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons. Estrous cycling data (each phase analyzed separately) were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons. One animal from the Nav1.8LKB1 group was removed from the estrus cycle tracking data as it was determined to be an outlier via the Grubb’s test with α = 0.05. Serum estradiol data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons The ROUT method with Q = 1% was used to identify multiple outliers. Eight outliers were identified and removed from analysis. Immunohistochemistry for retrograde tracing experiments were analyzed using ordinary two-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. Histological datasets were analyzed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Follicle and oocyte histology datasets were analyzed using ordinary two-way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak’s correction for multiple comparisons. Histograms for follicle histology were made by calculating the frequency distribution for each data set and plotting the percentage of samples within each bin. Student’s t-test was used to analyze RNA in situ hybridization to assess knockdown of LKB1 in Nav1.8 expressing neurons.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the large size of the raw data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Carson, S. A. & Kallen, A. N. Diagnosis and management of infertility: a review. JAMA. 326 (1), 65–76 (2021).

Deng, Y. et al. Steroid hormone profiling in obese and nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 14156 (2017).

Lainez, N. M. & Coss, D. Obesity, neuroinflammation, and reproductive function. Endocrinology. 160 (11), 2719–2736 (2019).

Magyar, B. P. et al. Short-term fasting attenuates overall steroid hormone biosynthesis in healthy Young women. J. Endocr. Soc. 6(7). (2022).

Sirotkin, A. V. et al. Body fat affects mouse reproduction, ovarian hormone release, and response to follicular stimulating hormone. Reprod. Biol. 18 (1), 5–11 (2018).

Wassif, W. S. et al. Steroid metabolism and excretion in severe anorexia nervosa: effects of refeeding. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93 (5), 911–917 (2011).

Molina, E., Hong, L. & Chefetz, I. AMPKα-like proteins as LKB1 downstream targets in cell physiology and cancer. J. Mol. Med. 99 (5), 651–662 (2021).

Shackelford, D. B. & Shaw, R. J. The LKB1–AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 9 (8), 563–575 (2009).

Garner, K. M. & Burton, M. D. Sex-specific role of sensory neuron LKB1 on metabolic stress-induced mechanical hypersensitivity and mitochondrial respiration. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 323 (2), R227–R243 (2022).

Chiu, I. M. et al. Bacteria activate sensory neurons that modulate pain and inflammation. Nature. 501 (7465), 52–57 (2013).

Huang, S. et al. Lymph nodes are innervated by a unique population of sensory neurons with immunomodulatory potential. Cell. 184 (2), 441–459e25 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. The role of somatosensory innervation of adipose tissues. Nature. 609 (7927), 569–574 (2022).

Lenert, M. E. et al. Sensory neurons, neuroimmunity, and pain modulation by sex hormones. Endocrinology, 162(8). (2021).

Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A., Verri, W. A. Jr. & Chiu, I. M. Nociceptor sensory neuron-immune interactions in pain and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 38 (1), 5–19 (2017).

Flores, A. et al. Acute effects of unilateral sectioning the superior ovarian nerve of rats with unilateral ovariectomy on ovarian hormones (progesterone, testosterone and estradiol) levels vary during the estrous cycle. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 9 (1), 34 (2011).

Kagitani, F., Uchida, S. & Hotta, H. Effects of electrical stimulation of the superior ovarian nerve and the ovarian plexus nerve on the ovarian estradiol secretion rate in rats. J. Physiol. Sci. 58 (2), 133–138 (2008).

Morales-Ledesma, L. et al. Unilateral sectioning of the superior ovarian nerve of rats with polycystic ovarian syndrome restores ovulation in the innervated ovary. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 8 (1), 99 (2010).

Ramírez Hernández, D. A. et al. Role of the superior ovarian nerve in the regulation of follicular development and steroidogenesis in the morning of diestrus 1. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37 (6), 1477–1488 (2020).

Rosas, G. et al. The neural signals of the superior ovarian nerve modulate in an asymmetric way the ovarian steroidogenic response to the vasoactive intestinal peptide. Front. Physiol. 9 (2018).

Arnold, J. et al. Imbalance between sympathetic and sensory innervation in peritoneal endometriosis. Brain. Behav. Immun. 26 (1), 132–141 (2012).

del Campo, M. et al. Effect of superior ovarian nerve and plexus nerve sympathetic denervation on ovarian-derived infertility provoked by estradiol exposure to rats. Front. Physiol. 10 (2019).

Lara, H. E. et al. Changes in sympathetic nerve activity of the mammalian ovary during a normal estrous cycle and in polycystic ovary syndrome: studies on norepinephrine release. Microsc. Res. Tech. 59 (6), 495–502 (2002).

Calka, J., McDonald, J. K. & Ojeda, S. R. The innervation of the immature rat ovary by calcitonin gene-related Peptide1. Biol. Reprod. 39 (5), 1215–1223 (1988).

Burden, H. W. et al. The sensory innervation of the ovary: a horseradish peroxidase study in the rat. Anat. Rec. 207 (4), 623–627 (1983).

Klein, C. M. & Burden, H. W. Substance P- and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)-immunoreactive nerve fibers in relation to ovarian postganglionic perikarya in para- and prevertebral ganglia: evidence from combined retrograde tracing and immunocytochemistry. Cell Tissue Res. 252 (2), 403–410 (1988).

Hanada, T. et al. Number, size, conduction, and vasoconstrictor ability of unmyelinated fibers of the ovarian nerve in adult and aged rats. Auton. Neurosci. Basic. Clin. 164 (1), 6–12 (2011).

Russell, F. A. et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 94 (4), 1099–1142 (2014).

Patil, M. J., Hovhannisyan, A. H. & Akopian, A. N. Characteristics of sensory neuronal groups in CGRP-cre-ER reporter mice: comparison to Nav1.8-cre, TRPV1-cre and TRPV1-GFP mouse lines. PLoS One. 13 (6), e0198601 (2018).

Szabo-Pardi, T. A. et al. Sensory Neuron TLR4 mediates the development of nerve-injury induced mechanical hypersensitivity in female mice. Brain Behav. Immunity. 97, 42–60 (2021).

Jia, L. et al. TLR4 signaling selectively and directly promotes CGRP release from vagal afferents in the mouse. Eneuro. 8(1). (2021).

Kupari, J. et al. An atlas of vagal sensory neurons and their molecular specialization. Cell. Rep. 27 (8), 2508–2523e4 (2019).

Morales, L. et al. Ipsilateral vagotomy to unilaterally ovariectomized pre-pubertal rats modifies compensatory ovarian responses. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 5 (1), 24 (2007).

Sapio, M. R. et al. Comparative analysis of dorsal root, nodose and sympathetic ganglia for the development of new analgesics. Front. Neurosci. 14 (2020).

Trujillo, A., Morales, L. & Domínguez, R. The effects of sensorial denervation on the ovarian function, by the local administration of capsaicin, depend on the day of the oestrous cycle when the treatment was performed. Endocrine. 48 (1), 321–328 (2015).

Gautron, L. et al. Genetic tracing of Nav1.8-expressing vagal afferents in the mouse. J. Comp. Neurol. 519 (15), 3085–3101 (2011).

Furat Rencber, S. et al. Effect of resveratrol and metformin on ovarian reserve and ultrastructure in PCOS: an experimental study. J. Ovarian Res. 11 (1), 55 (2018).

Kocer, D., Bayram, F. & Diri, H. The effects of metformin on endothelial dysfunction, lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 30 (5), 367–371 (2014).

Alessi, D. R., Sakamoto, K. & Bayascas, J. R. LKB1-dependent signaling pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75 (1), 137–163 (2006).

Herzig, S. & Shaw, R. J. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19 (2), 121–135 (2018).

Saikia, R. & Joseph, J. AMPK: a key regulator of energy stress and calcium-induced autophagy. J. Mol. Med. 99 (11), 1539–1551 (2021).

Mounier, R. et al. AMPKα1 regulates macrophage skewing at the time of resolution of inflammation during skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Metabol. 18 (2), 251–264 (2013).

Asada, N., Sanada, K. & Fukada, Y. LKB1 regulates neuronal migration and neuronal differentiation in the developing neocortex through centrosomal positioning. J. Neurosci. 27 (43), 11769 (2007).

Barnes, A. P. et al. LKB1 and SAD kinases define a pathway required for the polarization of cortical neurons. Cell. 129 (3), 549–563 (2007).

Burger, C. A. et al. LKB1 coordinates neurite remodeling to drive synapse layer emergence in the outer retina. eLife. 9, e56931 (2020).

Huang, W. et al. Protein kinase LKB1 regulates polarized dendrite formation of adult hippocampal newborn neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 (1), 469–474 (2014).

Shelly, M. et al. LKB1/STRAD promotes Axon initiation during neuronal polarization. Cell. 129 (3), 565–577 (2007).

Winckler, B. BDNF instructs the kinase LKB1 to grow an Axon. Cell. 129 (3), 459–460 (2007).

Courchet, J. et al. Terminal Axon branching is regulated by the LKB1-NUAK1 kinase pathway via presynaptic mitochondrial capture. Cell. 153 (7), 1510–1525 (2013).

Kwon, S. K. et al. LKB1 regulates mitochondria-dependent presynaptic calcium clearance and neurotransmitter release properties at excitatory synapses along cortical axons. PLoS Biol. 14 (7), e1002516 (2016).

Colledge, W. H. The neuroendocrine regulation of the mammalian reproductive axis. Introduction. Exp. Physiol. 98 (11), 1519–1521 (2013).

Lotti, F. et al. Metabolic Syndrome and Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(4). (2021).

Perrigo, G. & Bronson, F. H. Foraging effort, food intake, fat deposition and puberty in female mice. Biol. Reprod. 29 (2), 455–463 (1983).

Hohos, N. M. et al. High-fat diet exposure, regardless of induction of obesity, is associated with altered expression of genes critical to normal ovulatory function. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 470, 199–207 (2018).

Lenert, M. E. & Burton, M. D. Acute effects of a high-fat diet on estrous cycling and body weight of intact female mice. Neuropsychopharmacology (2021).

Negrón, A. L. & Radovick, S. High-Fat Diet alters LH secretion and pulse frequency in female mice in an estrous cycle-dependent manner. Endocrinology. 161(10). (2020).

Arnal, J. F. et al. Membrane and nuclear estrogen receptor alpha actions: from tissue specificity to medical implications. Physiol. Rev. 97 (3), 1045–1087 (2017).

Paterni, I. et al. Estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ): subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids. 90, 13–29 (2014).

Leitman, D. C. et al. Regulation of specific target genes and biological responses by estrogen receptor subtype agonists. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 10 (6), 629–636 (2010).

Chen, I. C. et al. Clinical relevance of liver kinase B1(LKB1) protein and gene expression in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 21374 (2016).

Papka, R. E. et al. Estrogen receptor-α and -β immunoreactivity and mRNA in neurons of sensory and autonomic ganglia and spinal cord. Cell Tissue Res. 304 (2), 193–214 (2001).

Zoubina, E. V. & Smith, P. G. Sympathetic hyperinnervation of the uterus in the estrogen receptor α knock-out mouse. Neuroscience. 103 (1), 237–244 (2001).

Chaban, V. et al. The same dorsal root ganglion neurons innervate uterus and colon in the rat. NeuroReport. 18(3). (2007).

Dodds, K. N. et al. Morphological identification of thoracolumbar spinal afferent nerve endings in mouse uterus. J. Comp. Neurol. 529 (8), 2029–2041 (2021).

Herweijer, G. et al. Characterization of primary afferent spinal innervation of mouse uterus. Front. NeuroSci. 8. (2014).

Stirling, L. C. et al. Nociceptor-specific gene deletion using heterozygous NaV1. 8-Cre recombinase mice. Pain. 113 (1–2), 27–36 (2005).

Bardeesy, N. et al. Loss of the Lkb1 tumour suppressor provokes intestinal polyposis but resistance to transformation. Nature. 419 (6903), 162–167 (2002).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 18 (7), e3000411 (2020).

National Research Council Committee for the Update of the Guide for the, C. and A. Use of Laboratory, The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health, in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2011, National Academy of Sciences.: Washington (DC). (2011).

Lenert, M. E., Chaparro, M. M. & Burton, M. D. Homeostatic regulation of estrus cycle of young female mice on western diet. J. Endocr. Soc. 5(4). (2021).

Byers, S. L. et al. Mouse estrous cycle identification tool and images. PLoS One. 7 (4), e35538 (2012).

Cora, M. C., Kooistra, L. & Travlos, G. Vaginal cytology of the laboratory rat and mouse: review and criteria for the staging of the estrous cycle using stained vaginal smears. Toxicol. Pathol. 43 (6), 776–793 (2015).

Miller, M. Q. et al. Two-photon excitation fluorescent spectral and decay properties of retrograde neuronal tracer Fluoro-Gold. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 18053 (2021).

Mondello, S. E. et al. Enhancing fluorogold-based neural tract tracing. J. Neurosci. Methods. 270, 85–91 (2016).

Schmued, L. C. & Fallon, J. H. Fluoro-gold: a new fluorescent retrograde axonal tracer with numerous unique properties. Brain Res. 377 (1), 147–154 (1986).

dos Santos, N. L. et al. Age and sex drive differential behavioral and neuroimmune phenotypes during postoperative pain. Neurobiol. Aging (2022).

Pedersen, T. & Peters, H. Proposal for a classification of oocytes and follicles in the mouse ovary. Reproduction. 17 (3), 555–557 (1968).

Westwood, F. R. The female rat reproductive cycle: a practical histological guide to staging. Toxicol. Pathol. 36 (3), 375–384 (2008).

Myers, M. et al. Methods for quantifying follicular numbers within the mouse ovary. Reproduction. 127 (5), 569–580 (2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all current and past members of the Neuroimmunology and Behavior Laboratory and Center for Advanced Pain Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas. In particular, the authors express gratitude to Natalia L dos Santos for her invaluable expertise and training in estrous cycle tracking and classification. The authors also thank Hanna Abdelhadi, Michaela Chaparro, and Andreas Matthew Chavez for their technical expertise and assistance. Finally, the authors thank Theodore J. Price and the Pain Neurobiology Research Group for their generous contributions to the ICR fertility metrics.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant F99NS129173 (MEL), Eugene McDermott Graduate Fellowship 202205 (MEL), R21DK130015-01A1 (MDB), Rita Foundation Award in Pain (MDB), and the University of Texas Rising STARS program research support grant (MDB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E.L. & M.D.B.: Participated in Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology and Writing. E.K.D: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing. M.D.B. Supervised all aspects of the study, acquired funding, and provided all resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lenert, M.E., Debner, E.K. & Burton, M.D. Sensory neuron LKB1 mediates ovarian and reproductive function. Sci Rep 14, 29109 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79947-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79947-2