Abstract

The study focuses on FTO/ZnO/Ag-x films (with different silver dopant levels) fabricated using the sol–gel/spin-coating technique. The optical, structural, and geometrical properties of these films were characterized through various methods, such as Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy, UV–visible spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM). Key findings include a reduction in transmittance and an increase in absorbance in the visible spectrum due to the interaction between silver and ZnO, enhancing photocatalytic properties. The optical band gap decreased from 3.23 to 2.80 eV with higher silver doping, suggesting the presence of Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR). Structural analysis confirmed a hexagonal wurtzite phase for ZnO and a body-centered cubic phase for silver, with polycrystalline layers forming on a single-crystalline FTO substrate. The films show potential for photocatalytic applications, particularly in water-splitting hydrogen production, and their photoelectrochemical performance as photoanodes was quantified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s world, humanity faces two critical challenges: managing energy risks and preventing ecosystem contamination. Among renewable energy sources, solar energy stands out for its abundance, sustainability, and environmental benefits. Utilizing solar energy for hydrogen gas (H2) production through water splitting has become a key focus. Photoelectrochemical (PEC) and photocatalytic methods have been explored as efficient ways to harness solar energy, converting it into storable and usable forms. The groundbreaking work1 on water splitting using titanium dioxide (TiO2) initiated the field of heterogeneous semiconductor photocatalysis. This technology is well-established, cost-effective, and offers a sustainable solution for converting solar energy into renewable H2 fuel, thus helping to reduce reliance on fossil fuels2.

The photocatalytic process relies on photo-induced charge carriers within semiconductor photocatalysts, leading to inter-band excitation of electrons and initiating subsequent redox reactions. Enhancing photocatalytic activity involves three main aspects: optimizing light absorption, improving charge carrier separation, and increasing catalytic efficiency3,4. Semiconductors like TiO2, ZnO, SnO2, and CeO2 are widely researched, with ZnO being notable for its high surface area and photosensitivity, making it suitable for catalysis, photocatalysis, photoelectrochemical, solar cells, and biological studies. As shown in Fig. 1, ZnO’s large band gap limits its activity to UV light, though its band positions make it highly effective for photocatalytic water-splitting applications.

However, the practical application of pristine ZnO as a photocatalyst is limited due to challenges such as inefficient charge carrier trapping, and significant electron–hole recombination rates, at its conduction and valence bands. Additionally, the high band gap confines its activity primarily to the ultraviolet (UV) region, which constitutes less than 5% of sunlight. To overcome these limitations and enhance its photocatalytic performance, an effective strategy involves incorporating noble metals with plasmonic properties, such as Ag and Au, as cocatalysts into ZnO. This modification facilitates the capture of photogenerated hot electrons, thereby reducing recombination rates and extending the lifetime of charge carriers (by about two times), which enhances photocatalytic activity under both UV and visible light5.

These modifications offer several advantages including facile reduction, high stability, efficient electron–hole pair generation, effective light absorption, and high affinity. Notably, noble metal centers on the ZnO surface act as efficient electron sinks, capturing photogenerated electrons and preventing recombination with holes, which substantially enhances photocatalytic activity (e.g., in water-splitting applications) under both UV and visible light6,7. In addition to metal modifications, the band gap and defects within the photocatalytic material play pivotal roles in their activity. Oxygen vacancies generated through impurity doping have been recognized for their contributions to improved photocatalytic performance8,9.

The plasmonic properties of noble metal nanoparticles lead to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect. LSPR occurs when the free electron density in a plasmonic metal collectively oscillates in response to visible light irradiation, where the light’s wavelength is significantly longer than the nanoparticle’s size. The electric field of the incident light displaces conduction electrons toward the nucleus, forming an electric dipole and enhancing the local electric field around the nanoparticle. This asymmetric charge distribution creates an internal and external electric field that opposes the incident light’s electric field. Consequently, the opposing field localizes the electron density, generating a Coulomb restoring force, that drives the resonant oscillation of conduction electrons at the same frequency as the incident light, but with significantly greater intensity.

Another cocatalyst that can enhance the photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO structures under visible light is carbon. In Ansari et al.10, C-doped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized through a single-step process demonstrated improved charge separation and enhanced visible light absorption, significantly boosting photocatalytic performance.

Various methods have been used to anchor metals onto ZnO nanostructures, including Hydrothermal Synthesis, Alkali Precipitation, Thermal Decomposition, Organo-Zinc Hydrolysis, Sol–Gel Chemical Method, Biogenic Synthesis using Biofilms, Flame Spray Pyrolysis, Photo Reduction, and Ball-Milling11. Each technique provides distinct control over the composition, morphology, and properties of the resulting metal-anchored ZnO nanostructures. For example, Zheng12 synthesized Ag/ZnO heterostructures with varying silver content via the solvothermal method, demonstrating tunable properties and functionalities. Similarly, AL-Jawad et al.13 synthesized Ag/ZnO nanostructures using the sol–gel method, highlighting their potential for antibacterial applications. Liu et al.14 reported the ultrasonic irradiation-assisted synthesis of worm-like core/shell Ag/ZnO composites with varying silver content. Zhang et al.15,16 fabricated silver nanoparticle-decorated flower-like ZnO nanostructures, demonstrating improved photocatalytic properties. They also decorated ZnO nanorods with Ag nanoprism/nanoparticles, resulting in enhanced photocurrent intensity due to localized surface plasmon resonance. Sawant et al. (2017) used an electrochemical biogenic synthesis to create Ag-ZnO nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic properties. Sawant et al.17, Reddy et al.18 employed a polyamine-mediated mineralization and reduction method to coat Ag@ZnO on cotton fabrics, achieving efficient photocatalytic activities.

Previous studies by this research group have explored the effects of doping various elements, including Cu19, Al20 and NiO21 on zinc oxide coated on various films such as ITO22, Si and Quartz23 has been investigated by several different methods such as RF-sputtering and RF magnetron sputtering. So, the crystalline structure, surface morphology, effect of temperature on film roughness, and optical, geometric, physicochemical, and mechanical properties were characterized. As a result, the studied films were proposed for electronic devices and transparent conducting oxide applications.

One of the key applications of photocatalytic materials, in addition to hydrogen production via water splitting, is the removal of pollutants and the treatment of urban and industrial wastewater, which has been the focus of valuable research. For instance, a study on nickel-carbon nanocomposites with hierarchical structures24 revealed significant catalytic and electrochemical properties in the catalytic reduction of compounds such as p-nitrophenol (PNP) and methyl orange (MO). Additionally, the effective removal of antibiotics, particularly diclofenac (DF), from wastewater was explored using mesoporous polyacrylamide/gelatin–iron lanthanum oxide nanohybrids25. Furthermore, the development of nickel oxide (NiO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanohybrids26 focused on enhancing the photocatalytic degradation of antibiotic pollutants, especially under visible light irradiation.

Several studies have proposed the synthesis of structures aimed at addressing the challenge of energy storage. Notable examples include: the WS2-halloysite nanocomposite27,28, which demonstrates an eco-friendly synthesis method with excellent properties for energy storage, particularly in electrochemical supercapacitors. Reduced graphene oxide-titanium silver nanocomposites29 exhibit a high specific surface area and enhanced electrochemical properties leading to improved charge storage capacity for energy storage devices. The NiO–CuO nanocomposite decorated with polyaniline30 has been utilized to create a high-performance symmetric supercapacitor, capable of operating effectively over a wide potential window. The WS2-MWCNT nanocomposite27,28 not only detects harmful chemicals like perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) but also functions as a supercapacitor for energy storage. Furthermore, the combination of CNT with samarium/cobalt layered double hydroxide31 resulted in a multifunctional composite material that effectively removes antimony and is utilized in high-capacitance energy storage devices, demonstrating excellent stability.

This study synthesizes ZnO/Ag nanostructures using a chemical sol–gel method at room temperature, incorporating varying silver weight percentages on zinc oxide nanocrystal surfaces. These nanostructures were spin-coated onto fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass substrates (1.5 × 1.5 cm2). The Ag-loaded ZnO films, with different silver contents, target photoelectrochemical water-splitting applications. The optical, structural, and geometrical properties were characterized using UV–visible spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), Photoluminescence (PL) and field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM). The research emphasizes modifying ZnO surfaces with silver nanoparticles and the resulting film formation, contributing to the development of efficient photocatalytic materials for renewable energy applications. We proved this claim by quantitatively investigating the photocatalytic efficiency, photoelectrochemical stability and electronic properties of the films.

Based on the optical, structural, and geometric properties of the prepared FTO/ZnO/Ag-x films, they are suggested for photocatalytic applications such as hydrogen production, enhancing performance across ultraviolet and visible light regions.

Experimental details

The synthesis of pristine and silver-doped zinc oxide (ZnO) solutions was accomplished using the sol–gel method. Initially, 25 ml of methanol (Merck, Germany) was mixed with an equal volume of isopropanol (IPA, Merck, Germany). Then, 6.5847 g of zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O, Merck, Germany), serving as the zinc precursor, was added to create ZnO seed solutions with a 0.6 M concentration. The mixtures were stirred vigorously at 60 °C for 1 h, resulting in a milky white solution. Monoethanolamine (MEA) was gradually added to the solution while maintaining constant stirring at 60 °C for 12 h to achieve a transparent solution. The MEA-to-ZnO molar ratio was kept at 1:1 to act as a stabilizing agent. After thorough mixing of the reagents, different concentrations (0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%) of silver nitrate (AgNO3, Applecom Germany) were introduced as dopants into the ZnO sol. Before deposition, the solution was aged at room temperature for 24 h to ensure homogeneity13.

FTO glass slides (1.5 cm × 1.5 cm, 1.6 mm thickness, and surface resistance below 30 ohms per square) were used as substrates. The cleaning process involved ultrasonic treatment in baths of acetone, polyethylene glycol, ethanol, and deionized water, with each step lasting 15 min, followed by air drying. ZnO or Ag-doped ZnO sol was deposited on the substrates using the spin-coating technique. The samples were dried at 150 °C for 20 min, a process repeated seven times to form a conformal film on the substrate. The final annealing step involved heating the samples at 500 °C for 2 h. A schematic of the preparation process for both pure and doped ZnO thin films is shown in Fig. 2. Details about the prepared samples are summarized in Table 1, and a view of the samples fabricated using the sol–gel/spin-coating technique is displayed in Fig. 3.

Results and discussion

Optical characterization

To study the optical properties of FTO/ZnO/Ag-x films, the transmission spectrum, absorption spectrum, extinction coefficient (K), Tauc plot, and photoluminescence (PL) spectrum were measured and analyzed as a function of varying Ag doping ratios.

Figure 4a presents the transmittance spectra of pure ZnO and Ag-doped ZnO films with doping ratios ranging from 2 to 8%. The spectra, recorded over wavelengths of 200–1100 nm, shows minimal transmission in the 200–380 nm region, corresponding to the Zn–O bond. In the visible region, a notable reduction in transmission is observed as the Ag concentration increases, indicating an interaction between silver and ZnO.

(a) optical transmittance spectra (b) absorbance spectra with repeatability test results, including standard deviations (c) extinction coefficient versus wavelength and (d) Tauc’s plots for the optical band gaps of FTO/ZnO and FTO/ZnO/Ag films (e) room temperature photoluminescence emission spectra of the films.

Figure 4b demonstrates that Ag-loaded ZnO enhances light absorption due to the surface plasmon resonance effect of Ag nanoparticles. This increased light absorption in the visible and near-infrared regions corresponds to the improved photocatalytic properties of the films. To ensure the reproducibility of the synthesis method, standard deviation bars are included in the absorbance spectra. The standard deviations are as follows: 0.56 for Pure ZnO, 0.52 for Ag/ZnO 2%, 0.53 for Ag/ZnO 4%, 0.46 for Ag/ZnO 6%, and 0.32 for Ag/ZnO 8%.

Figure 4c illustrates the variations in the extinction coefficient (K) of Ag/ZnO films with different silver doping levels. The K represents the loss of light due to absorption or scattering per unit volume. It quantifies the reduction in electromagnetic wave intensity concerning the wavelength (λ). The extinction coefficient can be calculated using the equation provided by Baydogan et al.32:

If cm−1 and cm represent the unit of α and λ, respectively, K becomes a unitless quantity.

The extinction coefficientof the FTO/ZnO film ranged from 0.12 to 0.29, increasing to approximately 0.14–0.62 after silver doping. For FTO/ZnO/Ag-x films, K values rose with wavelength, peaking in the higher wavelength region of the visible spectrum, indicating opacity in that range (except for pristine ZnO). As silver concentration increased, the K peak exhibited a red shift, with corresponding increases in K. This suggests that visible wavelengths are absorbed more effectively than lower wavelengths. The enhanced K values with higher silver content indicate significantly improved photon absorption in the FTO/ZnO film, which correlates with findings in Fig. 4a,b. Overall, increased Ag concentration enhances light absorption and boosts the photocatalytic performance of the films.

The optical band gaps of prepared films were calculated using the Tauc equation33:

where α, hν, Eg, and B correspond respectively with absorption coefficient, photon energy, optical bandgap, and band tailing parameter. Also, n = 1/2 is considered for semiconductors with direct transition bandgap like ZnO.

Figure 4d reveals that the optical bandgap of the FTO/ZnO film was approximately 3.23 eV, which decreased to around 2.80 eV for the FTO/ZnO/Ag-8 film. This reduction in the bandgap indicates that the addition of silver in the synthesized structure led to the formation of defect sites, which affected the crystallinity of the material.

To evaluate the potential for energy transfer events that do not involve charge transfer, we conducted photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy on the samples. All samples were excited with an excitation wavelength of 320 nm. A decrease in emission intensity was observed for the Ag/ZnO 8% sample compared to the other samples, as shown in Fig. 4e. This reduction in emission intensity suggests a decrease in electron–hole recombination.

Structural characterization

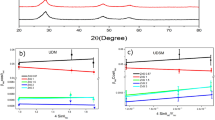

Figure 5a shows the XRD spectra recorded from the films under investigation. To estimate various geometric parameters related to the crystalline structure of the films, the following methods were independently used: the Scherrer method34, the Williamson–Hall method35 and, the Rietveld method36. The first method assumes that observed line broadening is mostly due to the finite size of the crystallites and relates the Bragg angle of the (hkl) peak with its width to yield the crystallite size along the given direction dhkl:

where θ is the diffraction angle corresponding to the peak maximum, β is the full-width half maximum of the line, K is the shape factor (usually 0.89), and λ is the X-ray wavelength.

Plots of XRD data taken from the reference substrate (bare FTO) and samples containing various amounts of Ag dopants in ZnO crystals: (A) XRD spectra indexed with appropriate (hkl) indices of crystalline components, (B) Williamson-Hall graph exhibiting relative strains and finite crystalline sizes within FTO/ZnO/Ag-0 film.

In turn, the Williamson–Hall method extends the Scherrer method to materials composed of distorted lattices. Assuming that both effects, finite size and lattice strain, equally contribute to the line width. So, the following equation is proposed:

where ε is the relative strain in the lattice. Figure 5b shows an example graph of (β∙cos(θ)) vs. sin(θ) dependence, the slope of which corresponds to the strain, while the intercept to the size of the lattice.

The last method, the Rietveld refinement algorithm, was originally developed for structure analysis of pure crystals, but then it demonstrated its usefulness in quantitative phase analysis of multicomponent materials as well. The iterative procedure minimizes the difference between the recorded XRD pattern and the hypothesized one based on the assumed crystal structure. Apart from refining the lattice parameters (crystal structure, lattice constants, atomic positions, etc.), the method is also able to establish the relative volume contents of each crystal sub-structure in multiphase samples similar to those studied in this work.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the structure analysis of the spin-coated ZnO films with Ag inclusions onto FTO substrates, obtained using the Scherrer method. A plentiful of various XRD peaks related to each crystalline phase shows on one hand well-developed crystals, but on the other—the lack of texture, which is the predominant orientation of the crystallites. As a whole, the deposited FTO/ZnO film is found to be a solid mixture of interconnected crystallites 90–160 Å in diameter depending on the crystalline direction and material. Note that for all samples, the sizes of the crystallites in a given FTO layer remain constant regardless of the crystalline direction, which proves that these crystallites are of spherical shape. Unlike that, the crystallites in the ZnO layer are found in oblong spheroids with the aspect ratio changing between 9:16 (sample FTO/ZnO/Ag-0) to 13:15 (FTO/ZnO/Ag-8). Finally, the crystallites constituting the Ag phase are found more regular than those in ZnO, but not perfectly spherical.

Averaged crystallite sizes from Table 2 (together with respective standard deviations) are shown in Fig. 6a. Note that the crystallite size in the FTO substrate varies with increasing Ag content in such a way that it starts from ca. 135 Å in the reference sample (bare FTO), then achieves minimum value (ca. 80 Å) for the sample with 4% Ag content, and finally rises again up to 110 Å. It is also worth noting that the standard deviation of these sizes is very small (less than 10%). Unlike FTO, crystallite sizes of ZnO remain nearly constant at ca. 130 Å, but their standard deviation is found much larger. Similar behavior can be seen for Ag crystallites, the sizes of which vary between 120 and 150 Å with significant standard deviations.

Table 3 presents similar data, that is the crystallite sizes of the constituent structures, together with relative lattice distortions estimated using the Williamson–Hall method. Similar to previous results, a graphical comparison of crystallite sizes within crystalline phases is shown in Fig. 6b.

Comparison of data shown in Fig. 6a,b reveal some interesting trends. Similar to the Scherrer method, the sizes of FTO crystallites vary in a non-monotonous way in the range from 150 to 120 Å, exhibiting a clear minimum at ca. 100 Å for samples with 4% Ag content. Unlike that, however, the sizes of the ZnO crystallites obtained from the Williamson–Hall method decrease with increasing Ag content in a completely different manner than that in Fig. 6a. In this case, the crystallites are found to be the largest in the pure ZnO layer (ca. 400 Å), but upon the addition of Ag gradual decrease to 160 Å is observed. Finally, the sizes of Ag crystallites agree well in both graphs (Fig. 6a,b), that is, they vary between 120 and 200 Å depending on the Ag content.

Results obtained using the Rietveld method, concerning the lattice constants and relative phase volumes of the constituent substructures, are summarized in Table 4. For clarity, the relative contributions of each sub-phase are also plotted as the stacked column graph (normalized to 100%) shown in Fig. 7. Note that all lattice parameters are very similar to those in perfect single-crystals that agree with rather low relative lattice distortions estimated using the Williamson–Hall method. This also applies to the tetragonality parameters (c0/a0 ratio in tetragonal and hexagonal lattices) that are found independent of the Ag addition level.

Summarizing, obtained XRD patterns reveal that the constituent materials in the spin-coated films have a structure composed of hexagonal ZnO (wurtzite) and body-centered-cubic Ag (regular) crystals mixed to form continuous layer onto otherwise single-crystalline FTO substrate. Note the intensities of Ag-related peaks that gradually saturate with increasing Ag content (compare, for example, Ag (200) peaks in various samples) which demonstrate the formation of Ag inclusions within the ZnO host lattice. In addition, the lattice parameters presented in Table 4 show no significant difference between Ag inclusions in the deposited films (4.08–4.09 Å) and the reference data (4.09 Å), which proves almost perfect Ag lattice. Assuming that the Ag atoms were substituted with foreign ones (e.g. Zn), the lattice would have been distorted leading to substantially different a0 values of the Ag lattice. On the other hand, assuming that the Ag atoms were placed in between lattice nodes, their respective XRD peaks were not present. As a whole, obtained results suggest that the spin-coated films are neither solid nor interstitial solutions of Ag atoms within the ZnO host lattice. These films are polycrystalline mixtures of solid phases of Ag and ZnO crystals.

Geometrical characterization

Figure 8 shows FESEM images that exhibit the granular structure of the spin-coated films under investigation. To analyze the specific surface morphology of these structures, the images were processed towards the estimation of several shape descriptors determining predominant planar figures. To this end, original grayscale FESEM images were first binarized and then segmented using the watershed algorithm to determine the edges of the grains (example shown in Fig. 9) followed by statistical analysis of obtained data. The reason for using of the watershed algorithm lies in its ability to induce closed object boundaries and its relatively low computation time compared to other segmentation methods (e.g. Otsu’s method, conjugated gradient method, edge detection etc.)37. On the other hand, the watershed might end up with over-segmentation and its sensitivity to noise, which can detrimentally affect the accuracy of the segmentation38.

The following parameters were calculated: circularity, roundness, solidity, and the Feret’s diameter. The first three parameters are fractional numbers lying in the range between zero and one, while the last one defines the specific size of the segments in terms of their lengths. Circularity is a positive fractional value that quantifies the deviation from a perfect circle. It is computed according to the formula39:

where A is the segment area, and P is its perimeter. As the figure gets more developed (very long coastline embracing very small land), the circularity decays to zero. On the contrary, the circularity of a perfect circle equals unity. In turn, the roundness is the ratio of the major and minor semi-axes lengths of the best-fit ellipse replacing the given selection area40:

where amin, and amax are the minor and major semi-axes of the equivalent ellipse, respectively. Another parameter, solidity, is the ratio of the actual area of the figure and its convex hull41:

For a perfectly convex figure solidity approaches the unity, otherwise it is less than but non-zero. The Feret’s diameter dF equals the length of a straight line lying in a segment and connecting any two points on its boundary. Among all possible dF values, the minimum and maximum Feret’s diameters are of special importance for the characterization of particle shape and form.

Statistical parameters of planar figures that approximate selected segments in grayscale maps obtained by watershed segmentation of FESEM images are reported in Table 5 and graphically summarized in Fig. 10. Note the striking homogeneity of obtained parameters in terms of mean and median values as well as standard deviations and min–max ranges between the samples comparing the unitless parameters: circularity, roundness, and solidity. The first parameter is found to change in the range between 0.46 and 0.63, which appears similar to that of the equilateral triangle (0.605). The next one—roundness—varies in a narrow range between 0.68 and 0.71 which exhibits a slightly elliptical mean shape of the segments. Similarly, the last parameter—solidity—also varies in a relatively narrow range between 0.78 and 0.84, which means that only ca. 20% of the convex hull area lies outside the actual edges of the segment. As a result, the average segment seen in the image looks similar to a figure based on an isosceles triangle (in agreement with circularity and roundness values) with slightly concave edges (according to solidity value) similar to a non-uniform triangle star.

Half-box graphs display shape descriptors of primary planar figures from watershed segmentation of FESEM images, representing first-order grains. (A) circularity, (B) roundness, (C) solidity, and (D) Feret’s diameter, along with their statistical measures: mean (solid lines), median (dotted lines), standard deviations (boxes), and min–max ranges (whiskers).

Results obtained in terms of the Feret’s diameter appear significantly different from those defining the overall shape of the segments (unitless parameters discussed above). First of all, the diameter is found to be larger than 40 nm in the samples containing 0, 2, and 6% of Ag in the films, while in the remaining two it is found either very small (ca. 20 nm in the sample with 4% Ag) or very large (100 nm in the sample with 8% of Ag). Such a result appears inconsistent with the previous estimations done using the XRD method. Note, however, that FESEM reveals the shape of the same surface, while XRD probes the films tens of micrometers into their depths. In addition, FESEM yields the shape of the grains mapped on a plane, whereas XRD brings the size of the coherently diffracting domains seen at various angles. As such, FESEM shows the view along the direction normal to the surface that reveals the planar shape of the tops of the otherwise columnar crystallites.

Electrochemical measurements

According to the energy band diagram of the n-type semiconductor (ZnO) connected to the plasmonic metal (Ag), as shown in Fig. 11a, the work function of silver (− 4.26 eV), which represents the Fermi level of the metal, is higher than the Fermi level of zinc oxide (− 5.2 eV). Under ultraviolet radiation, Ag acts as an electron sink; by forming a Schottky barrier at the metal/semiconductor interface, preventing the electrons from returning to the conduction band of ZnO. Additionally, the holes remain in the valence band of the semiconductor. In this manner, Ag traps the electrons and inhibits the recombination of e⁻ and h⁺. Consequently, the electrons accumulated on the metal surface can participate in the photocatalytic reaction, as illustrated in Fig. 11b.

When visible light irradiates a noble metal with plasmonic properties due to its LSPR characteristic, three scenarios are possible (as shown in Fig. 12a–c)42,43,44:

-

Hot electrons are injected from the metal into the semiconductor due to intra-band transitions.

-

A strong near-field electric field forms on the semiconductor, leading to resonance energy transfer.

-

Photon scattering by the metal nanoparticles causes light to travel a longer path within the metal/semiconductor nanostructure, increasing absorption.

The first scenario is, of course, the most probable. Hot electrons gain sufficient energy to overcome the Schottky barrier and enter the conduction band (CB) of the semiconductor. Additionally, electrons are induced to accumulate in the CB due to resonance energy transfer and the formation of a near-field electric field. Consequently, a significant number of charge carriers flow into the semiconductor’s CB, where they can reach the surface and occupy active sites for the reduction reaction, thereby enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. When visible light is emitted, the number of electrons accumulated in the semiconductor’s CB is significantly higher than the number of holes in the valence band. Therefore, despite some electron–hole (e−/h+) recombination, the recombination rate remains lower than the rate of electron generation.

According to Fig. 13a, the redox reactions (reduction and oxidation) of hydrogen-bonded compounds, such as H₂O, can be carried out using a three-electrode photoelectrochemical cell, resulting in the production of exhaust gases, O₂ and H₂, at the working and counter electrodes, respectively. Finally, the electron transfer pathway under UV/visible light irradiation, shown in Fig. 13b, leads to a reduction reaction on both semiconductor and metal surfaces, thereby improving the efficiency of photocatalytic activity.

To evaluate the photoelectrochemical performance of the fabricated films as photoanodes, linear to assess the photoelectrochemical performance of the fabricated films as photoanodes, we employed a three-electrode PEC setup featuring a platinum counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) measurements and applied bias photo-conversion efficiency (ABPE) calculations were conducted. The LSV measurements spanned from − 2.0 to 2.0 V at a scan rate of 100 mV/s under xenon light irradiation, utilizing a 0.5 M NaOH aqueous solution. Photocurrent intensities (Jph) were recorded at a bias potential of 1.23 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), which corresponds to the minimum photon energy necessary for the water-splitting reaction.

Figure 14a presents the I–V curves for ZnO and ZnO/Ag films deposited on FTO substrates. The photocurrent intensities under illumination were measured as follows: 227.6 µA/cm2 for pure ZnO, 850.2 µA/cm2 for ZnO/Ag 2%, 1586.7 µA/cm2 for ZnO/Ag 4%, 2265.4 µA/cm2 for ZnO/Ag 6%, and 3260.5 µA/cm2 for ZnO/Ag 8% at 1.23 V. Notably, the photocurrent for the 8% ZnO/Ag photoanode increased approximately 14-fold compared to the pure ZnO film. This significant enhancement is attributed to the presence of Ag nanoparticles, which improve light-harvesting efficiency by effectively trapping electrons in shallow trap states.

To evaluate the photoelectrochemical performance quantitatively, we calculated the applied bias photo-conversion efficiency (ABPE) using the formula outlined by Behara et al.45:

In this equation, Eapp denotes the potential difference between the working and counter electrodes, Jph is the photocurrent intensity, and Ilight represents the incident illumination power density (400 mW/cm2).

The ABPE was derived from the J-V curve shown in Fig. 14a. As illustrated in Fig. 14b, among the five samples evaluated, the ZnO/Ag 8% in a 0.5 M NaOH electrolyte solution exhibited the highest ABPE, approximately 0.72%.

To investigate the impact of Ag doping on the electrochemical performance of ZnO films, we employed cyclic voltammetry (CV). An aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide was selected as the electrolytic medium, and measurements were conducted below 2.2 V vs. RHE in a three-electrode configuration to prevent the oxidation of Ag nanoparticles under both dark and xenon lamp illumination conditions.

Figure 15 presents the CV plot with a scan rate of 100 mV/s in a 0.5 M NaOH solution for the fabricated FTO/ZnO and FTO/ZnO/Ag-8% films, recorded over 10 and 50 cycles. The results indicate the high stability of the FTO/ZnO/Ag-8% film, demonstrating the robust covalent linkages between the photocatalyst materials and the FTO substrate, which are anchored via click chemistry. In contrast, the lower stability observed in the pure ZnO film may be attributed to photo-corrosion, resulting in surface cracks within the ZnO material.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is employed to study the electrical characteristics of photoanodes, providing insights into their interfacial electrical conductivity46. Figure 16a displays the EIS spectra of ZnO/Ag films with varying amounts of silver dopants on FTO substrates, measured under both dark and illuminated conditions at frequencies ranging from 1000 kHz to 100 MHz. The size of the semicircle in the EIS plot represents the electron transfer resistance, which influences the rate of electron movement at the electrode interface. In the dark, the EIS arcs are significantly larger than those under illumination due to the reduced generation of electrons. When exposed to light, the impedance decreases markedly because of the separation of photogenerated charge carriers, indicating that illumination greatly reduces the charge transfer resistance at the electrode/electrolyte interface. This demonstrates that Ag-doped ZnO films exhibit lower resistance and facilitate faster electron transfer, resulting in shorter electron transfer times. Higher concentrations of silver further accelerate charge transfer in ZnO/Ag films, aiding the migration of plasmon-induced hot carriers from silver to the surface of zinc oxide.

The Nyquist plots obtained were fitted using a circuit model, as shown in Fig. 16b. The Randles circuit was utilized to achieve EIS spectra that closely matches the expected results of an electrochemical experiment. In this circuit, Zw, Rsol, Cdl, Cct, and Rct correspond to the Warburg impedance, solution resistance, double layer capacitance, charge transfer capacitance, and charge transfer resistance, respectively. It is important to note that the mechanism of charge transport in these structures differs between dark and illuminated conditions, as indicated by the distinct EIS circuits observed. A probable reason for this discrepancy is the absence of surface states in the dark, which leads to the lack of Cct in the EIS circuit.

The interface between the FTO substrate and the ZnO/Ag layer plays a crucial role in influencing the electronic properties that affect photocatalytic activity. A well-engineered interface promotes efficient charge separation, reduces electron–hole recombination, and facilitates smooth charge transfer, all of which are essential for enhanced photocatalytic performance.

Figure 17 illustrates the effect of the interface between the FTO substrate and the ZnO/Ag-8% layer on photoelectrochemical (PEC) current density over time. The blue curve represents a well-formed interface, where efficient charge transfer occurs between the FTO substrate and the ZnO/Ag layer, resulting in higher photocatalytic efficiency and lower recombination rates. In contrast, the red dashed curve indicates a poorly formed interface, where charge transfer is less effective, leading to reduced photocatalytic efficiency and increased recombination of electron–hole pairs. The gray area highlights the performance disparity, demonstrating how improving the interface can significantly enhance photocatalytic activity by facilitating electron transfer and minimizing recombination.

Conclusion

The optical characterization of FTO/ZnO/Ag-x films revealed unique absorption properties in the visible light spectrum. Increasing silver content led to a decrease in the optical bandgap (Eg), enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. This improvement is attributed to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect of silver. Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy confirmed the formation of a Schottky barrier at the ZnO-Ag interface, reducing electron–hole recombination and contributing to the films’ enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light.

Three methods—Scherrer, Williamson–Hall, and Rietveld—were used to analyze the crystal structure of FTO/ZnO/Ag-x films. The Scherrer method indicated that FTO crystallites were spherical, ZnO crystallites were oblong spheroids, and Ag crystallites were nearly spherical. While the FTO crystallite size changed with increased silver doping, the sizes of ZnO and Ag crystallites remained mostly unchanged. The Williamson–Hall method confirmed these findings for FTO and Ag but showed a decrease in ZnO crystallite size with higher silver doping. Rietveld analysis supported the Williamson–Hall results, showing minimal lattice distortions and consistent phase volumes across doping levels. Structural analysis revealed a mixture of hexagonal wurtzite ZnO and body-centered cubic Ag, forming polycrystalline layers on a monocrystalline FTO substrate. FESEM analysis, using grayscale image processing and statistical evaluation of surface parameters (circularity, roundness, solidity), confirmed uniform surface morphology.

Silver-doped ZnO improves the transfer of hot electrons to the conduction band, enhancing Applied Bias Photo-conversion Efficiency (ABPE). The increased efficiency in FTO/ZnO/Ag systems is attributed to effective charge transport across interfaces, aided by proper band-edge alignment and electrochemical potential gradients, which promote electron–hole separation. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy confirms improved interfacial charge transfer kinetics, while covalent bonds between nanoparticles and the substrate enhance stability and activity. These findings are key for designing more efficient photocatalysts for applications like hydrogen production, wastewater treatment, and solar cells.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Fujishima, A. & Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972).

Waseem, R., Khursheed, A., Rais, A. K. & Haekyoung, K. Ag decorated ZnO for enhanced photocatalytic H2 generation and pollutant degradation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48(75), 29071–29081 (2023).

Ma, X. C., Dai, Y., Yu, L. & Huang, B. B. Energy transfer in plasmonic photocatalytic composites. Light Sci. Appl. 5, e16017 (2016).

Zhang, C. et al. Au nanoparticles sensitized ZnO nanorod@nanoplatelet core–shell arrays for enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Energy 12, 231–239 (2015).

Fageria, P., Gangopadhyay, S. & Pande, S. Synthesis of ZnO/Au and ZnO/Ag nanoparticles and their photocatalytic application using UV and visible light. RSC Adv. 4, 24962–24972 (2014).

Deng, Q. et al. Ag nanoparticle decorated nanoporous ZnO microrods and their enhanced photocatalytic activities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4(11), 6030–6037 (2012).

Wang, P., Huang, B., Dai, Y. & Whangbo, M. H. Plasmonic photocatalysts: Harvesting visible light with noble metal nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14(28), 9813–9825 (2012).

Archana, B., Manjunath, K., Nagaraju, G., Sekhar, K. B. C. & Kottam, N. Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen generation and photostability of ZnO nanoparticles obtained via green synthesis. Hydrogen Energy 42, 5125–5131 (2016).

Mittal, M., Sharma, M. & Pandey, O. P. UV–Visible light induced photocatalytic studies of Cu doped ZnO nanoparticles prepared by co-precipitation method. Solar Energy 110, 386–397 (2014).

Ansari, S. A. et al. Novel furfural-complexed approach to synthesizing carbon-Doped ZnO with breakthrough photocatalytic efficacy. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.08.014 (2024).

Bokov, D., Jalil, A.T., Chupradit, S., Suksatan, W., Ansari, M.J., Shewael, I.H., Valiev, G.H., Kianfar, H. (2021). Nanomaterial by sol-gel method: Synthesis and application. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng.

Zheng, Y. et al. Ag/ZnO heterostructure nanocrystals: Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalysis. Inorg. Chem. 46(17), 6980–6986 (2007).

Al-Jawad, S. M. H., Sabeeh, S. H., Taha, A. A. & Jassim, H. A. Studying structural, morphological and optical properties of nanocrystalline ZnO: Ag films prepared by sol-gel method for antimicrobial activity. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 87, 362–371 (2018).

Liu, H. R. et al. Worm-like Ag/ZnO core–shell heterostructural composites: fabrication, characterization, and pphotocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 116(30), 16182–16190 (2012).

Zhang, X., Zhao, J., Wang, S., Dai, H. & Sun, X. Shape-dependent localized surface plasmon enhanced photocatalytic effect of ZnO nanorods decorated with Ag. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39(16), 8238–8245 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. Growth and characterization of flower-like Ag/ZnO heterostructure composites with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Mater. Sci. 49, 2347–2354 (2014).

Sawant, S. Y., Kim, J. Y., Han, T. H., Ansari, S. A. & Cho, M. H. Electrochemically active biofilm-assisted biogenic synthesis of an Ag-decorated ZnO@C core–shell ternary plasmonic photocatalyst with enhanced visible-photocatalytic activity. New J. Chem. 42(3), 1995–2005 (2018).

Reddy, T. N., Manna, J. & Rana, R. K. Polyamine-mediated interfacial assembly of rGO-ZnO nanostructures: A bio-inspired approach and enhanced photocatalytic properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7(35), 19684–19690 (2015).

Dejam, L. et al. ZnO, Cu-doped ZnO, Al-doped ZnO and Cu-Al doped ZnO thin films: Advanced micro-morphology, crystalline structures and optical properties. Results Phys. 44, 106209 (2023).

Ţălu, Ş et al. Microstructure and micromorphology of ZnO thin films: Case study on Al doping and annealing effects. Superlattices Microstruct. 93, 109–121 (2016).

Ghaderi, A. et al. Evaluating structural, morphological, and multifractal aspects of n-ZnO/p-ZnO homojunctions and n-ZnO/p-NiO heterojunctions. Microsc. Res. Technique 86(6), 731–741 (2023).

Dejam, L. et al. ITO:n-ZnO:p-NiO and ITO:n-ZnO:p-NZO thin films: Study of crystalline structures, surface statistical metrics, and optical properties. Microsc. Res. Technique 85(11), 3674–3693 (2022).

Solaymani, S. et al. Optical properties and surface dynamics analyses of homojunction and hetrojunction Q/ITO/ZnO/NZO and Q/ITO/ZnO/NiO thin films. Results Phys. 29, 104679 (2021).

Hammud, H. H. et al. Catalytic and capacitive properties of hierarchical carbon–nickel nanocomposites. Catalysts 14, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal14030181 (2024).

Parveen, N. et al. Emerging mesoporous polyacrylamide/gelatin-iron lanthanum oxide nanohybrids towards the antibiotic drugs removal from the wastewater. Nanomaterials 13(21), 2835. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13212835.PMID:37947681;PMCID:PMC10649728 (2023).

Ansari, S. A. et al. Emerging NiO–rGO nanohybrids for antibiotic pollutant degradation under visible-light irradiation. Surfaces Interfaces 40, 103078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2023.103078 (2023).

Mashkoor, F. et al. A smart recycling solution: WS2-halloysite nanocomposite for heavy metals remediation from wastewater and postliminar application in electrochemical supercapacitor for energy storage. Appl. Clay Sci. 245, 107149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2023.107149 (2023).

Mashkoor, F. et al. Freestanding WS2-MWCNT nanocomposite for electrochemical detection of contaminants of emerging Concern-Perfluorooctanoic Acid “A forever chemical” and supercapacitor applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c02376 (2023).

Shoeb, M. et al. Unraveling the electrochemical properties and charge storage mechanisms of lactobacillus-mediated synthesized RGO-titanium silver nanocomposite as a promising binder-free electrode for asymmetric supercapacitor device. J. Alloys Compounds 964, 171188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171188 (2023).

Adnan, S. M. et al. Fabrication of NiO–CuO decorated polyaniline (PANI/NiO–CuO) nanocomposite based symmetric supercapacitor device for high-energy density performance with wide potential window in aqueous electrolyte. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 157, 111265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111265 (2023).

Mashkoor, F., Shoeb, M., Khan, M. N. & Jeong, C. CNT supported Sm/Co-LDH for antimony adsorption and subsequent application in supercapacitor to prevent secondary pollution. J. Alloys Compounds. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.173557 (2024).

Baydogan, N., Ozdurmusoglu, T., Cimenoglu, H. & Tugrul, A. B. Refractive index and extinction coefficient of ZnO:Al thin films derived by sol-gel dip coating technique. Defect Diffusion Forum 334–335, 290–293 (2013).

Tauc, J., Grigorovici, R. & Vancu, A. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous germanium. Phys. Status Solidi B 15, 627–637 (1966).

Patterson, A. L. The Scherrer formula for X-Ray particle size determination. Phys. Rev 56(10), 978 (1939).

Williamson, G. K. & Hall, W. H. X-ray line broadening from filed aluminum and wolfram. Acta Metallurgica 1(1), 22–31 (1953).

Rietveld, H. M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. Appl. Crystallogr. 2(2), 65–71 (1969).

Leena Silvoster, M., Kumar, R.M.S. in Segmentation of Images Using Watershed and MSER: A State-of-the-Art Review, Vol. 295, 463–480. (Springer, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47411-9_25.

Viqar, M., Madjarova, V. & Stoykova, E. Modified watershed approach for segmentation of complex optical coherence tomographic images. J. Int. Sci. Publ. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2303.16609 (2022).

Surace, R., De Filippis, L.A.C., Niini, E., Ludovico, A.D., Orkas, J., (2009). Morphological investigation of foamed aluminum parts produced by melt gas injection. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng.

Takashimizu, Y., Iiyoshi, M., (2016). New parameter of roundness R: Circularity corrected by aspect ratio. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 3(2).

Kopanja, L., Loncar, B., Zunic, D. & Tadic, M. Nanoparticle shapes: Quantification by elongation, convexity and circularity measures. Electr. Eng. 70(7S), 44–50 (2019).

Bumajdad, A. & Madkour, M. Understanding the superior photocatalytic activity of noble metals modified Titania under UV and visible light irradiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CP54411G (2014).

Fu, Y.S., Li, J., Li, L. (2019). Metal/semiconductor nanocomposites for photocatalysis: Fundamentals, structures, applications and properties. Nanomater. MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9030359.

Xiao, F. X. & Liu, B. Plasmon-dictated photo-electrochemical water splitting for solar-to-chemical energy conversion: current status and future perspectives. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.201701098 (2018).

Behara, D. K. et al. Synchronization of charge carrier separation by tailoring the interface of Si–Au–TiO2 heterostructures via click chemistry for PEC water splitting. CES 154, 150–169 (2016).

Ahmad, R., Hahn, Y. B., Ahn, M. S. & Bhat, K. S. Fabrication of a robust and highly sensitive nitrate biosensor based on directly grown zinc oxide nanorods on a silver electrode. New J. Chem. 41, 10992. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nj02526b (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Original draft A.S. Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Methodology, Review-editing and editing E.D. Original draft. Review-editing and editing M.B. Software, Formal analysis, Review-editing and editing S.K. Software, Formal analysis, Review-editing and editing J.S. Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation S.S. Virtualization, Writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anzabi, L.C., Shafiekhani, A., Darabi, E. et al. Nanoscale 3D spatial analysis of FTO/ZnO/Ag-x films subjected to photocatalytic activity. Sci Rep 15, 7330 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82949-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82949-9