Abstract

The study aimed to elucidate the underlying pharmacological mechanism of the traditional Chinese medicine Pue in ameliorating myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI), a critical clinical challenge exacerbated by reperfusion therapy. In vivo MIRI and in vitro anoxia/reoxygenation (A/R) models were constructed. The results demonstrated that Pue pretreatment effectively alleviated MIRI, as manifested by diminishing the levels of serum CK-MB and LDH, mitigating the extent of myocardial infarction and enhancing cardiac functionality. Additionally, Pue significantly alleviated histopathological damage in MIRI-treated myocardium, as evidenced by HE staining and TUNEL assay. In vitro, Pue pretreatment significantly alleviated A/R-induced damage by decreasing LDH levels, increasing cellular activity, inhibiting autophagic lysosomal overactivation, inhibiting oxidative stress (ROS, LIP ROS, MDA), increasing antioxidant defense (SOD, GSH-Px), and increasing P62 protein expression while decreasing LC3II/I ratio. Furthermore, Pue inhibited apoptosis and maintained mitochondrial homeostasis by up-regulating the expression of Hairy and Enhancer of Split-1 (HES1) protein, which was crucial for its cardioprotective effects. Nevertheless, the cardioprotective efficacy of Pue pretreatment was negated via the knockdown of HES1 protein expression via pAD/HES1-shRNA transfection. In conclusion, Pue effectively ameliorated HES1-mediated MIRI-induced autophagy, apoptosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a highly prevalent and fatal condition, characterized by myocardial cell damage and, in severe cases, irreversible necrosis, posing a substantial threat to human life and health1,2. Prompt hemoperfusion (reperfusion) remains the backbone of contemporary life-saving therapeutic strategies for patients with AMI and is crucial to salvage the myocardial tissue from persistent necrosis. Nevertheless, reperfusion of ischemic myocardium induces cardiomyocyte death, further exacerbating myocardial ischemic injury, i.e., myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI)3,4. Therefore, revealing the underlying mechanisms of MIRI may assist AMI patients in obtaining more clinical benefits.

Previous research has identified a myriad of biological processes, including inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and calcium overload, in the pathogenesis of MIRI. Although researchers have attempted to work tirelessly on alleviating MIRI by developing multiple pharmacological strategies targeting anti-inflammatory antioxidants5. However, clinical efficacy has not been satisfactory. This suggests that there are other biological processes involved in MIRI. Recently, ferroptosis, apoptosis, and autophagy-triggered role of regulated cell death (RCD), have emerged as crucial players in MIRI-triggered myocardial injury6,7,8. Nevertheless, the precise role of apoptosis and autophagy in the prevention and treatment of MIRI remains unclear. Notably, the impact of autophagy on MIRI is twofold. Several studies have demonstrated autophagy protects cardiomyocytes during ischemia; however, the excessive autophagy in myocardial reperfusion exacerbates cardiomyocyte injury9,10,11,12. Consequently, deciphering the underlying association between the molecular regulatory mechanism of MIRI and autophagy is imperative for developing novel therapeutic drugs and effective targets.

The HES family (HES1-7) comprises basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, of which HES1 plays a critical role in cell differentiation and cycle regulation13,14. It has been shown that macrophage overexpression of HES1 can activate cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathways to attenuate renal ischemia/reperfusion injury15. Furthermore, the knockdown of HES1 expression exacerbates the injury caused by stroke16. Nevertheless, the relationship between HES1 and autophagy in MIRI has not been clearly defined.

Puerarin (Pue) is the main bioactive ingredient isolated from Radix puerariae, with the capacity for pharmacological effects such as dilating cerebral and cardiac vessels and reducing tissue free radical production17,18. Moreover, has demonstrated ASI’s cardioprotective effects via inhibiting apoptosis through the Notch1/HES1 signaling pathway19. Although Pue has been reported to attenuate MIRI through multiple pathways, encompassing anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory responses, and anti-oxidative stress17, it is unclear whether HES1 participates in autophagy and apoptosis after Pue treatment.

Overall, the following scientific hypothesis was proposed: Pue pretreatment can protect against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibiting excessive autophagy and apoptosis by modulation of HES1. By elucidating this mechanism, we aim to provide novel insights into the therapeutic potential of Pue and HES1 in mitigating MIRI, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective treatment strategies for AMI patients.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and animals

Pue (purity of ≥ 98.0%) was acquired from MUSTBIO Technology Co., Ltd. (ChengDu, China). Rapamycin (RA, autophagy agonist) and 3-methyladenine (3-MA, autophagy antagonist) were purchased from MedChemExpress Bioreagents. Adenoviral pAD/HES1-shRNA and pAD/HES1-shRNA-NC (NC: negative control) were acquired from Cyagen Biologicals. (SuZhou, China). Antibodies against BCL2, BAX, LC3I/II and HES1 were procured from ZENBIO (ChengDu, China). Antibodies against P62, and β-actin were acquired from Proteintech Group, Inc (Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Horseradish peroxide-coupled IgG was sourced from ZENBIO (ChengDu, China).

Adult healthy male SD rats were purchased from the Animal Center of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China). The experimental procedures followed the guidelines of the ARRIVE and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines, and were authorized by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Approval No. CDYFY-IACUC-202407QR015).

In vitro experiments

Culture of H9c2 cardiomyocytes

A rat H9c2 cardiomyocyte cell line was acquired from The Cell Bank/Stem Cell Bank (BeiJing, China). Cells were cultured in High-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (H-DMEM, HyClone, Cytiva) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (PSG; 100×) (GIBIO, ThermoFisher, U.S.A.) with standard atmosphere (95% humidity, 21% O2, and 5% CO2) at 37.0˚C.

Transfection of the adenovirus and establishment of the A/R model

The pAD/HES1-shRNA or NC was introduced into the cells cultured in a fresh H-DMEM with 10% FBS. Following the attainment of approximately 85% transfection efficiency after 48 h, the subsequent experiments were implemented. The target sequences of pAD/HES1-shRNA and NC are listed in Table S1.

An A/R model was employed to simulate in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI) conditions. In brief, H9c2 cardiomyocytes were placed in anoxia medium (NaCl 98.50 mM, NaH2PO4 0.90 mM, NaHCO3 6.00 mM, CaCl2 1.00 mM, KCl 10.00 mM, MgSO4 1.20 mM, HEPES 20.00 mM, sodium lactate 40.00 mM and pH 6.80) at 37˚C with 5% CO2 and 95% N2 for 4 h. Following, cells were incubated in reoxygenation liquid (NaCl 129.50 mM, NaH2PO4 0.90 mM and NaHCO3 20.00 mM, CaCl2 1.00 mM, KCl 5.00 mM, MgSO4 1.20 mM, glucose 5.5 mM, HEPES 20.00 mM and pH 7.40) under an air-tight chamber at 37 ◦C, 95% O2 and 5% CO2 for 4 h, using to simulate MIRI.

Experimental design

The cells were allocated randomly to eight groups as follows for the subsequent experiments: (a) Control group; (b) A/R group: cardiomyocytes were incubated in A/R liquid; (c) A/R + Concentration-gradient Pue group: cardiomyocytes were pre-treated with Pue (20, 40, 80, 160 and 320 µM) 48 h, then its exposed to A/R liquid; (d) A/R + Pue group: prior to A/R, cardiomyocytes pre-treated with 80 µM Pue 48 h; (e) A/R + Pue + RA: 80 µM Pue + 200nM RA co-incubated for 48 h prior to A/R; (f) A/R + 3MA: 5mM 3MA pre-treatment for 24 h and then exposure to A/R for 4 h/4 h; (g) A/R + Pue + pAD/HES1-shRNA: exposed to A/R Pre-injury, cells pre-treated with 80 µM Pue and pAD/HES1-shRNA for 48 h; ) A/R + Pue + NC: exposed to A/R Pre-injury, H9c2 cardiomyocytes pre-treated with NC and pre-treated with 80 µM Pue for 48 h.

Assessment of cell viability and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity

The viability of cells and LDH level were quantified utilizing the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) colorimetric assay (GlpBio cat. no. GK10001). and LDH assay kit (Beyotime, cat. no. C0017) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Oxidative stress assay

With A/R treatment, cell lysate supernatants were collected. The release of Cellular Superoxide dismutase (SOD, (Beyotime, cat. no. S0101M)), malondialdehyde (MDA, (Beyotime, cat. no. S0131M)), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px, (Nanjing Jiancheng, cat. no. A005-1-2)) and glutathione /glutathione disulfide (GSH/GSSG, (Beyotime, cat. no. S0053)) form cells were measured by means of a commercially available assay kit, respectively.

Quantification of caspase-3

Following various induction, the supernatants of cell lysates were collected. Caspase-3 activity was quantified utilizing a caspase-3 assay kit (Beyotime, cat. no. C1115) in accordance with the instructions provided in the kit.

Western bloting

Protein was extracted from the cells of each group using western and IP cell lysates (Beyotime, cat. no. P0013) following the protocol. The protein concentration was measured utilizing the BCA assay kit (Beyotime, cat. no. P0012). Subsequently, 40 µg protein sample was subjected to ionisation with a 12.5%or 10% PAGE color rapid gel (UElandy, cat. no. S6172S, S6171S). Subsequently, the protein-containing coagulum was transferred by wet transfer. The PVDF was then sealed with 5% nonfat dry milk for 2 h. Primary antibodies against HES1 (1:500; ZENBIO, cat. no. 381205), P62 (1:2000; ProteinTech, cat. no. 18420-1-AP), LC3I/II (1:800; ZENBIO, cat. no. 381544), BCL2 (1:800; ZENBIO, cat. no. 381702), BAX (1:800; ZENBIO, cat. no. 380709), and β-actin (1:2000; ProteinTech, cat. no. 20536-1-AP) were incubated overnight in a low-speed shaker maintained at 4.0 °C. The following day, the membranes incubated with a secondary Goat anti-Rabbit/Mouse IgG H&L-conjugated antibody (1:5000; ZENBIO, cat. no. 511203 cat. no. 511103) for 1 h at room temperature, respectively. Finally, the membranes were visualized using the ECL kit (Beyotime, cat. no. P0018S). The intensity of grey values in the protein lanes was measured using the ImageJ software.

Detection of intracellular ROS and lipid ROS (LIP ROS)

Intracellular ROS and LIP ROS levels were measured using a DCFH-DA kit (Beyotime; cat. no. S0033S) and a C11-BODIPY581/591 kit (GlpBio; cat. no. GC40165), respectively. Briefly, cardiomyocytes were treated and then incubated with 10µM DCFH-DA, 1µL C11-BODIPY581/591 per 1 ml no-FBS medium and 10 µl /mL Hoechst 33,342 (Beyotime, Cat. No. C1028) for 25 min at 37.0 °C in a cell culture incubator. Intracellular ROS and LIP ROS levels in cell populations from different experimental groups were observed using an inverted fluorescence microscopy technique (Olympus).

Evaluation of Lyso-Tracker Red

Cardiomyocytes were incubated with the fluorescent dye Lyso-Tracker Red (Beyotime, cat. no. C1046) for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark following the reagent manufacturer’s instructions. Changes were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Flow cytometry assay

Cellular mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opening and apoptosis were evaluated using the MMP assay kit (BestBio, cat. no. BB-4105), MPTP assay kit (BestBio, cat. no. BB-48122), and V-FITC/PI apoptosis kit (BestBio, No. BB-4101), respectively, following the reagent vendor’s protocol. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells/tube were collected after treatment and then incubated withJC-1, BBcellProbe M61 and Annexin V-FITC/PI Probe, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 20 min or 15 min in the dark, respectively. These cells were then immediately analyzed using Agilent NovoCyte Advanteon (Agilent, no. BB-4101) flow cytometer [MMP: excitation (EX) with 485 nm, emission (EM) with 580 nm; MPTP: EX with 488 nm, EM with 520 nm; apoptosis: Ex with 488 nm; Em with 578 nm; ] for in real-time. The analysis of events is conducted using 10.0 FlowJo.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) microimaging

Briefly, 1 × 106 cells/tube were collected after treatment, and incubated overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 3 h. After fixation, dehydration, embedding, and ultrathin sectioning (50 nm), staining was performed for 10 min. Autophagosomes were observed via TEM.

In vivo experiments

Establishment of MIRI model

Following 7 days of adaptive feeding, Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were systematically randomized into four groups: (1) Sham group, (2) MIRI group, (3) MIRI + Pue group, (4) MIRI + Pue + pAD/HES1-shRNA group. Rats in the Sham and MIRI groups received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of normal saline; rats in the MIRI + Pue group were administered with Pue (100 mg/Kg/d, i.p, 3 weeks); rats belonging to MIRI + Pue + pAD/HES1-shRNA group underwent the same Pue treatment regimen as the MIRI + Pue group for two weeks, followed by intramyocardial injection of pAD/HES1-shRNA (2 × 10¹¹ plaque-forming units/ml, distributed across five sites, with 10 µl per site). The MIRI model was constructed by ligating the coronary arteries left (LAD) of the anterior descending. Prior to the procedure20, rats were sedated and analgesic-treated with 1.5% isoflurane and meloxicam (5 mg/kg). Subsequently, they were positioned supine on the operating table, connected to a small animal ventilator, and underwent a left 3–4 intercostal incision to expose the heart. The LAD was then ligated with a 7 − 0 silk suture for 45 min to induce myocardial ischemia, followed by suture release to allow for 24 h of reperfusion. Conversely, the Sham-operated group underwent an identical surgical protocol without the actual clamping of the LAD.

Echocardiography

After MIRI treatment, cardiac functionality was meticulously assessed using 2D transthoracic echocardiography based on the Vevo 2100 imaging system (VisualSonics Inc, Can Canada) after anesthetizing the rats with 1.5% isoflurane and immobilizing them on an operating table.

Measurement of CK-MB and LDH

After undergoing sonication, serum samples were prepared for each group. Subsequently, the serum levels of LDH and CK-MB were quantitated using the corresponding assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng, Nanjing, China) in adherence to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of infarct size

The infarct area was evaluated through dual staining with triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) and Evans blue. Following reperfusion, the LAD was clamped, and subsequently, 0.5% Evans blue dye was injected into the left ventricle. Hearts were promptly excised, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for 45 s, and sectioned into 8-mm transverse slices. These slices were then incubated in 2% TTC (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 37 °C for 25 min. After incubation, the heart sections were fixed in paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 h, and images were captured for analysis.

Hematoxylin & eosin (HE) staining

After MIRI treatment, the collected rat hearts of each group were fixed in 4% PFA, dehydrated in gradient ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned, then deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated in gradient ethanol. Finally, the sections were incubated with HE dye and visualized with a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) to observe pathological changes in the myocardial tissue in the sections.

TUNEL saining

Briefly, myocardial tissues were fixed in 4% PFA, dehydrated, embedded, and sectioned. Staining was performed according to the instructions of the TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Images of the stained sections were acquired using a Nikon fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

DHE saining

After MIRI treatment, heart samples were collected, dehydrated, frozen, embedded in OCT, and sectioned (6 μm), then stained using a dihydroethidium (DHE) probe (Yeasen, China) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, ROS levels in the tissue sections were detected using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ci, Japan).

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed utilizing GraphPad Prism 9.0. The results were performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s or Tukey’s subsequent multiple comparison tests, and showed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). P ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Ethics statement

All animal experimental procedures followed the guidelines of the ARRIVE and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines, and were authorized by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Approval No. CDYFY-IACUC-202407QR015).

Results

Pue preclude H9c2 cardiomyocytes from injury induced by A/R

The chemical structure diagram of Pue is illustrated in Fig. 1A. The effectiveness of A/R model construction and the protective concentration of Pue was determined using a high-sensitivity CCK-8 assay for cell activity and LDH for cytotoxicity assessment. H9c2 Cardiomyocytes were incubated with 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 µM Pue for 48 h and then exposed to A/R treatment. The study results indicate a significant decrease in cell viability and an increase in LDH in the A/R group in comparison to the Control group, confirming the efficacy of the in vitro A/R-mimicking MIRI construct. Additionally, Pue improved cardiomyocyte activity in a dose-dependent manner. However, at drug concentrations exceeding 160 µM, cell viability decreased rather than increased, and cytotoxicity increased (Fig. 1B - D). Based on the principle of optimal drug delivery, 80 µM Pue was selected for the next series of experiments (Fig. 2A and B).

Pue preclude H9c2 cardiomyocytes from injury induced by A/R. (A) Chemical formula for Pue. (B, C) Cell Counting Kit-8 assay of A/R-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte viability after different concentrations of Pue pre-treatment. (D) LDH. Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pue, Puerarin; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ns, not significant.

Pue inhibits A/R-induced oxidative stress and excessive autophagy in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. (A) Cell Counting Kit-8 assay of A/R-induced cells viability after Pue, RA or 3-MA pre-treatment. (B) LDH, (C) SOD, (D) MDA, (E) GSH-Px, (F) GSH/GSSG ratio, (G) Caspase-3 activity and (H-K) Protein expression of HES1, P62, and LC3II/I was determined using Western bloting analysis in cell lysates after A/R-induced following pre-treatment with Pue, RA or 3MA. Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pue, Puerarin; RA, rapamycin; 3MA, 3-methyladenine; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, Malondialdehyde; GSH/GSSH, glutathione/glutathione disulfide; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase. HES1, Hairy and Enhancer of Split-1; P62, Sequestosome 1; LC3B, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; ns, not significant.

Pue inhibits A/R-induced oxidative stress and excessive autophagy in H9c2 cardiomyocytes

Following the completion of A/R treatment, the level of oxidative stress release in cardiomyocytes was examined to determine the role of Pue on oxidative stress during A/R injury. Compared to the Control group, the A/R group showed a significant decrease in SOD and GSH-Px activity, as well as the GSH/GSSG ratio, and an increase in MDA after injury. However, pretreatment with 80 µM Pue reversed these changes. Autophagy-related reagents were used to observe the efficacy of Pue on autophagy. The findings indicated that 3MA, an autophagy inhibitor, ameliorated A/R-induced oxidative stress injury, whereas RA, an autophagy activator, counteracted the protective effect of Pue (Fig. 2C-G). Autophagy-related protein levels and HES1 expression levels were detected to evaluate the effects of Pue on A/R-induced autophagy and HES1. In contrast to the AR group, the Pue and 3MA pretreatment group upregulated the expression levels of HES1 and P62, while decreasing the LC3II/I ratio. Conversely, RA counteracted the beneficial effect of Pue (Fig. 2H-K). These results suggest that Pue may protect cardiomyocytes from A/R injury by upregulating HES1, mitigating oxidative stress, and inhibiting excessive autophagy.

Pue prevents MPTP opening and Lyso-Tracker Red production from injury induced by A/R

Compared to the Control group, the A/R group exhibited MPTP over-opening. Treatment with 80 µM Pue and 5 mM 3MA prevented MPTP over-opening, while 200 nM RA treatment reversed the protective effect of Pue (Fig. 3A and B). Additionally, autophagy lysosomal expression levels were detected using a Lyso-Tracker Red staining tracer. The intensity of red fluorescence was significantly higher in the AR-injured group compared to the Control group. Pre-treatment with Pue, 3-MA significantly reduced the fluorescence expression level, while RA counteracted its beneficial effect (Fig. 3C and D). These results suggest that Pue may protect cardiomyocytes from A/R damage by altering A/R-induced pH changes and inhibiting autophagy.

Pue prevents MPTP opening and Lyso-Tracker Red production from injury induced by A/R. (A, B) Flow cytometry BBcellProbe M61 assay for cellular MPTP following Pue, RA or 3MA pre-treatment. (C, D) Fluorescent probe LysoTracker Red for detecting lysosomes and quantitative analysis following treatment (enlargement, 200×; scaled bar: 50 μm). Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pue, Puerarin; RA, rapamycin; 3MA, 3-methyladenine; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; MPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; ns, not significant.

Pue ameliorates autophagy of A/R-induced via mediating HES1 in cardiomyocytes

The experiments above demonstrated that Pue pretreatment had a similar effect to 3-MA after A/R injury. This prevented autophagic overactivation by upregulating HES1 expression. Based on the up-regulation of HES1 expression, the study investigated the inhibitory effect of HES1-mediated Pue on A/R-induced autophagy by silencing the expression of HES1 through transfection of pAD/HES1-shRNA. We first verified the successful transfection of H9c2 cells with HES1 adenovirus at the protein molecular level, as shown in FIG. S1. In addition, the results of the protein molecular level demonstrated that Pue pretreatment notably elevated the expression of HES1 and P62 protein levels while decreasing the LC3II/I ratio. However, silencing HES1 expression through transfection of pAD/HES1-shRNA reversed the changes in the expression of autophagy-related proteins by Pue (Fig. 4A- D).

Pue inhibits autophagy of A/R-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes via mediating HES1. (A-D) Expression and quantification of HES1, P62, LC3II/I, proteins in A/R-induced cells were determined using western bloting analysis after pre-treatment with Pue, pAD/HES1-shRNA or NC. (E) Lyso-Tracker-Red stained images of H9c2 cardiomyocytes (enlargement, 200×; scaled bar: 50 μm), (F) Autophagosomes were observed via TEM (enlargement, 8000×; scaled bar: 200 nm). Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pue, Puerarin; NC, negative control; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; TEM, Transmission electron microscopy; ns, not significant.

Additionally, autophagy lysosomal expression levels were detected using a Lyso-Tracker Red staining tracer. The intensity of red fluorescence was significantly higher in the AR-injured group compared to the Control group. Pre-treatment with Pue, notably decreased the fluorescence expression level, while pAD/HES1-shRNA transfection resisted its beneficial effect (Fig. 4E).

Similarly, autophagic vesicles were revealed using TEM. The results indicate a significant increase in the number of autophagosomes following A/R treatment-induced injury in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Pretreatment with pue was effective in reducing autophagosome overproduction, while pAD/HES1-shRNA transfection reversed these changes (Fig. 4F).

The results suggest that Pue inhibits autophagy of A/R-induced via upregulating HES1 in cardiomyocytes.

Pue inhibits A/R-induced oxidative stress and lipid oxidation by adjusting HES1

To confirm the cardioprotective effect of Pue inhibition of oxidative stress through HES1, pAD/HES-shRNA + Pue or NC + Pue was transfected into cardiomyocytes pretreated for 48 h, followed by A/R treatment. Compared to the Control group, SOD, GSH-Px, and GSH/GSSG decreased obviously, while MDA increased in the A/R group. MDA activity decreased remarkably, and SOD, GSH-Px, and GSH/GSSG increased in the AR + Pue group and AR + Pue + NC group. However, pAD/HES-shRNA reversed the protective effect of Pue (Fig. 5A-D).

Pue inhibits accumulation of oxidative stress and lipid oxidation in A/R-induced by adjusting HES1. (A) SOD activity in A/R-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes after pre-treatment with Pue, pAD/HES1-shRNA or NC, (B) MDA, (C) GSH-Px, (D) GSH/GSSG ratio, (E) Immunofluorescence for the detection and quantitative analysis of ROS (enlargement, 200×; scaled bar: 50 μm). (F)Immunofluorescence for the detection of LIP ROS after treatment and quantitative analysis (enlargement, 200×; scaled bar: 50 μm). Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pue, Puerarin; NC, negative control; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; GSH/GSSH, glutathione/glutathione disulfide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; LIP ROS, lipid ROS; ns, not significant.

Moreover, intracellular ROS (green) and LIP ROS (green/red) levels were measured using an inverted fluorescence microscopy technique. The results showed significantly higher levels of green fluorescence intensity expression and decreased red fluorescence in the A/R group compared with the Control group. Pue pretreatment significantly inhibited A/R-induced fluorescence intensity expression of cellular ROS and LIP ROS. However, the protective role of Pue production on cells was counteracted by pAD/HES1-shRNA transfection (Fig. 5E, F). The findings suggest that Pue alleviates A/R-induced oxidative stress and lipid oxidation in H9c2 cardiomyocytes by adjusting HES1.

Pue alleviates apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes induced by A/R injury via mediating HES1

When examining the relationship between the protective role of autophagy induced by A/R and Pue, changes in apoptosis-related metrics were observed. The levels of BCL2 and Bax protein expression were measured using Western blot. Following A/R-induced injury, BCL2 expression was remarkably reduced, while Bax expression levels and the Bax/BCL2 ratio were elevated in the A/R group compared to the Control group. However, Pue pretreatment significantly reversed these changes. In contrast, the protective role of Pue on A/R induction was blocked by pretreatment with pAD/HES1-shRNA, while pAD/HES1-shRNA-NC treatment had no significant effect on Pue (Fig. 6A and B). The study also confirmed the results through the use of a kit assay of caspase-3 activity and flow cytometry of apoptosis rate, which was in line with the appeal (Fig. 6C-E). These findings demonstrated that Pue plays a significant role in protecting H9c2 cardiomyocytes from A/R damage via inhibiting apoptosis through the regulation of HES1.

Pue alleviates apoptosis caused by A/R injury by mediating HES1. (A) Western bloting analysis for the detection of protein expression and quantitative analysis of BCL2 and Bax in cell lysates after Pue, pAD/HES1-shRNA or NC treatment. (B) Caspase-3 activity, (C, D) Apoptosis was detected using the Annexin V-FITC/PI via flow cytometry. Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pue, Puerarin; NC, negative control; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; BCL2, B‑cell Lymphoma-2; Bax, BCL2‑associated X protein; ns, not significant.

Pue inhibits MPTP opening, MMP loss in A/R-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes to ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction by adjusting HES1

Numerous studies have demonstrated the criticality of maintaining mitochondrial functional homeostasis for cardiomyocytes21,22,23. MPTP and MMP are essential components of mitochondria24. Thus, the impact of HES1-mediated Pue on mitochondria during A/R injury was evaluated by detecting changes in MPTP and MMP. The BBcellProbe M61 assay and JC-1 stain results indicated a significant decrease in MPTP and an increase in MMP red/green ratio in the A/R group, respectively, compared to the Control group. Pretreatment with Pue significantly prevented MPTP opening and MMP depolarizing. Conversely, pAD/HES-shRNA treatment nullified the protective effect of Pue pretreatment (Fig. 7A, B and C, D). The results indicate that Pue inhibits MPTP opening and MMP loss in A/R-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes, thereby ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction by regulating HES1.

Pue inhibits MPTP opening, MMP loss in A/R-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes to ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction by adjusting HES1. (A, B) Flow cytometry BBcellProbe M61 assay for cellular MPTP. (C, D) JC-1 assay for cellular MMP. Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Pue, Puerarin; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; MPTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; NC, negative control; ns, not significant.

Pue safeguards cardiomyocytes from MIRI injury via the mediation of HES1

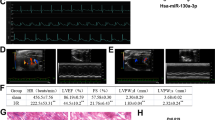

A MIRI model was constructed using SD rats to validate the in vivo protective effect of Pue. Our in vivo results showed that myocardial injury biomarker levels (LDH and CK-MB) were significantly elevated in the serum of MIRI-injured rats (Fig. 8A and B). Similarly, cardiac echocardiographic results showed that cardiac function was severely impaired after MIRI injury, as evidenced by a significant reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular shortening fraction (LVFS). Notably, Pue effectively improved MIRI-induced appeals to serological biomarkers and cardiac function. In contrast, the above in vivo protective effects of Pue against MIRI were eliminated by pAD/HES1-shRNA (knockdown of HES1) intervention (Fig. 8C-E). Similarly, the extent of myocardial infarction was significantly larger in the MIRI group than in Sham, and importantly, it was pretreatment with Pue that significantly reduced the infarct extent, whereas pAD/HES1-shRNA intervention blocked this protective effect of Pue (Fig. 8F and G). In addition, TUNEL staining and HE pathology sections showed that in the MIRI group, the myocardial tissue exhibited a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes, damage to myocardial fibers, and disorganized cardiomyocyte arrangement. Similarly, pre-administration of Pue was effective in ameliorating MIRI-induced pathomorphological changes in myocardial tissue. However, pAD/HES1-shRNA intervention reversed the above in vivo protective effects of Pue against MIRI (Fig. 8H and I). Furthermore, the results of DHE staining (tissue ROS), which were consistent with those of in vitro experiments (Fig. 8J). Our results suggest that Pue can effectively ameliorate MIRI by mediating HES1.

Pue alleviates MIRI-triggered myocardial damage. (A) CK-MB levels in serum of rats in each group. (B) LDH. (C) LVEF. (D) LVFS. (E) Representative images of rat heart detected by echocardiography. (F, G) Representative images of rat myocardial infarction area. (H-J) Representative images of rat myocardial tissue damage by H&E, TUNEL, and DHE staining (enlargement, 200×, scaled bar: 50 μm). Data are showed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Despite reperfusion treatment rescuing ischemic cardiomyocytes, paradoxically, reperfusion itself aggravates further myocardial injury—commonly known as MIRI25,26,27. The biological process of MIRI is complex, and the current treatment efficacy is not desirable. Therefore, mitigating MIRI is a critical issue to be addressed in clinical treatment. In the present study, we found that PUE attenuated cardiomyocyte injury in an A/R experimental model, and this cardioprotective effect was mediated by HES1. In addition, we elucidated for the first time that Pue inhibits autophagy, anti-oxidative stress, and anti-apoptosis, and maintains mitochondrial function by regulating HES1.

Autophagy is essential for maintaining homeostasis in cells, tissues, and organisms28, while dysregulated autophagy can cause numerous diseases, including MIRI29. Nevertheless, the role of autophagy in MIRI is controversial. Cui et al. reported that autophagy induced by the HIF-1α/BNIP3 signaling pathway in MIRI has a protective effect in cardiomyocytes30. Similarly, Wang et al. found that inhibition of TRPML1 channels restored impaired myocardial autophagy, which in turn significantly reduced myocardial infarction area and rescued cardiac function in I/R mice31. Conversely, Resveratrol can attenuate MIRI by inhibiting autophagy through the DJ-1-regulated MEKK1/JNK pathway32. Ginsenoside Rb1 attenuates MIRI by inhibiting autophagy via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway33. Previous studies have shown autophagy to be a double-edged sword. Adaptive autophagy is protective against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, whereas excessive autophagy promotes myocardial reperfusion injury. Furthermore, the mentioned study demonstrated the significant role of traditional Chinese medicine in inhibiting autophagy to attenuate MIRI.

Pue is the main bioactive component isolated from Pueraria lobata34. It is used extensively to treat cardiovascular diseases due to its various pharmacological properties, such as vasodilatation, cardio-protection, and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties34. In recent years, numerous studies have reported that Pue can improve MIRI through multiple mechanisms, including Inhibition of autophagy, anti-apoptosis, antioxidative and anti-inflammation18,35,36. Likewise, the A/R model was constructed in this study using Pue pretreatment of cardiomyocytes. The experimental results showed that Pue pretreatment increased the expression of P62 protein in cardiomyocytes, decreased the LC3II/I ratio, and reduced the formation of autophagic lysosomes. In addition, Pue pretreatment decreased MDA and ROS, increased GSH/GSSG ratio, increased expression of the apoptosis-related protein BCL2, and decreased Bax in cardiomyocytes. Remarkably, the red-green transition of MMP and the opening of MPTP in A/R model cardiomyocytes decreased after Pue pretreatment. The above observations indicated Pue attenuates myocardial injury by inhibiting autophagy, antioxidants, anti-apoptosis, and maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis.

The regulatory mechanism of autophagy in MIRI is complex and regulated by a variety of signaling pathways, including HIF-1α/BNIP3, AKT/mTOR, AMPK/SIRT3, and miR-193a-3p/ALKBH530,33,37,38. HES1 belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix DNA-binding proteins family and is essential for the development of multiple organs39. HES1 has been reported to inhibit autophagy, which regulates PTEN expression and exacerbates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy40. However, only one study has indirectly reported a link between the NOTCH1/HES1/AKT pathway and autophagy via microRNA-30e in MIRI. In addition, the authors did not clarify whether there is a regulatory relationship between HES1 and autophagy41. Therefore, the relationship between HES1 and autophagy in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury is unclear. In the present study, we discovered cardiomyocyte injury after constructing the A/R model was associated with HES1 downregulation and increased autophagy. On the other hand, administration of Pue enables attenuation of A/R-induced cardiomyocyte injury by upregulating HES1 and inhibiting autophagy. To further clarify the relationship between HES1 and autophagy in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cells were pretreated with pAD/HES1-shRNA to observe the changes of autophagy in A/R model cardiomyocytes after Pue treatment. The experimental results showed that the expression of P62 protein decreased and the ratio of LC3II/I increased in cardiomyocytes after HES1 knockdown, indicating that the inhibitory effect of Pue on autophagy had disappeared. TEM and Lyso-Tracker Red staining revealed similar results. Consistent with this, the in vivo results confirmed that pre-treatment with Pue was effective in improving myocardial protection against MIRI. The above findings suggest that Pue protects cardiomyocytes from A/R or MIRI damage by inhibiting excessive autophagy through HES1, which is also the innovation of this study.

Apoptosis and autophagy are two forms of programmed cell death involved in the pathogenesis and development of MIRI, and crosstalk between the two death modes appears at all stages of MIRI development42,43,44. Consistent with this, we confirmed the involvement of autophagy and apoptosis in MIRI by examining different enzymes and biochemical functional indices. Numerous studies have demonstrated that some natural herbal components can exert pharmacological effects by mediating multiple targets and signaling pathways45. For example, BCF has been shown to protect cardiomyocytes against MIRI by inhibiting apoptosis and autophagy46, EGCG has been reported to alleviate myocardial MIRI through inhibition of apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis20. Thus, the therapeutic implications of targeting apoptosis and autophagy are apparent, and it will be important for the prevention and treatment of MIRI-induced RCD multi-target drugs are expected to be a more effective therapeutic strategy for MIRI, based on the pathological significance and mechanisms of apoptosis and autophagy underlying MIRI. As a potential target of several herbal drugs, HES1 is upregulated in MIRI and can protect cardiomyocytes from ischemia/reperfusion injury by participating in NOTCH, PTEN/AKT pathways19,47. However, the role of HES1 in the pathological processes of autophagy and apoptosis has not been fully elucidated. Therefore, we hypothesized that Pue could also attenuate A/R injury by upregulating HES1 to inhibit different RCDs. In the present study, we demonstrated that Pue significantly upregulated the protein level of HES1, and Pue significantly inhibited excessive autophagy while reducing A/R-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, and decreased caspase-3 activity. Notably, we found that autophagy-associated proteins (p62 and LC 3 I/II) and apoptosis-associated proteins (BCL2 and BAX) exhibited synchronous changes. However, pAd/HES1-shRNA transfection abrogated the effects of Pue on myocardial autophagy- and apoptosis-related indices. These findings reveal that Pue may affect the crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy in cardiomyocytes and prevent myocardium from MIRI injury by regulating HES1.

MPTP-dependent cell death is a form of cell death driven by mitochondrial dysfunction caused by MPTP opening and triggered by increased levels of Ca2+ and ROS48. Previous studies demonstrated that MPTP opening is an important factor contributing to MIRI23,24,49. The results of the present study show that Pue maintains mitochondrial homeostasis by reducing A/R-induced MPTP opening in cardiomyocytes. Notably, not only autophagy activators but also pAd/HES1 shRNA transfection treatment could block the effect of Pue on mitochondrial function.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study clarified that Pue could attenuate MIRI-induced damage by upregulating HES1 to inhibit autophagy, maintain redox homeostasis, reduce apoptosis, and preserve mitochondrial function. These results provide mechanistic evidence for the role of HES1 in the cardioprotective effects of Pue against MIRI-induced damage (Fig. 9).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Correspondence author.

References

Algoet, M. et al. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and the influence of inflammation. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 33(6), 357–366 (2023).

Dong, C. et al. Gut microbiota combined with metabolites reveals unique features of acute myocardial infarction patients different from stable coronary artery disease. J. Adv. Res. 46, 101–112 (2023).

Ibáñez, B., Heusch, G., Ovize, M. & Van de Werf, F. Evolving therapies for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65(14), 1454–1471 (2015).

Xiao, H. et al. CIRKIL exacerbates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by interacting with Ku70. Circ. Res. 130(5), e3–e17 (2022).

Dong, L. et al. Research progress of chinese medicine in the treatment of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Chin. Med. 51, 1–17 (2023).

Xiang, Q., Yi, X., Zhu, X. H., Wei, X. & Jiang, D. S. Regulated cell death in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 35(3), 219–234 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Galangin alleviated myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by enhancing autophagic flux and inhibiting inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 945, 175621 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Salvianolic acid B inhibits ferroptosis and apoptosis during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via decreasing the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of GPX4 and the ROS-JNK/MAPK pathways. Molecules 28, 4117 (2023).

Chen, H. Y. et al. ELAVL1 is transcriptionally activated by FOXC1 and promotes ferroptosis in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating autophagy. Mol. Med. 27(1), 14 (2021).

Gu, S. et al. Downregulation of LAPTM4B contributes to the impairment of the autophagic flux via unopposed activation of mTORC1 signaling during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 127(7), e148–e165 (2020).

Yu, Y. W. et al. Shexiang Baoxin Pill attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by activating autophagy via modulating the ceRNA-Map3k8 pathway. Phytomedicine 104, 154336 (2022).

Zeng, M., Wei, X., He, Y. L., Chen, J. X. & Lin, W. T. TFAP2C inhibits cell autophagy to alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating miR-23a-5p/SFRP5/Wnt5a axis. FASEB J. 37(6), e22959 (2023).

De Decker, M. et al. HES1 and HES4 have non-redundant roles downstream of Notch during early human T-cell development. Haematologica 106(1), 130–141 (2021).

Kageyama, R., Ohtsuka, T. & Tomita, K. The bHLH gene Hes1 regulates differentiation of multiple cell types. Mol. Cells 10(1), 1–7 (2000).

Inoue, T. et al. Non-canonical cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway-mediated activation of peritoneal macrophages induces Hes1 and blocks ischemia/reperfusion injury in the kidney. Kidney Int. 95(3), 563–576 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Hes1 knockdown exacerbates ischemic stroke following tMCAO by increasing ER stress-dependent apoptosis via the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP signaling pathway. Neurosci. Bull. 36(2), 134–142 (2020).

Gao, M. et al. Puerarin: A protective drug against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front, Pharmacol 13, 927611 (2022).

Wang, Z. K. et al. Puerarin protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting inflammation and the NLRP3 inflammasome: The role of the SIRT1/NF-κB pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 89(Pt B), 107086 (2020).

Huang, H., Lai, S., Wan, Q., Qi, W. & Liu, J. Astragaloside IV protects cardiomyocytes from anoxia/reoxygenation injury by upregulating the expression of Hes1 protein. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 94, 542–553 (2016).

Hu, T. et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate confers protection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting ferroptosis, apoptosis, and autophagy via modulation of 14-3-3η. Biomed. Pharmacother. 174, 116542 (2024).

Bassiouni, W., Valencia, R., Mahmud, Z., Seubert, J. M. & Schulz, R. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 proteolyzes mitofusin-2 and impairs mitochondrial function during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 118(1), 29 (2023).

Jin, Q. et al. DUSP1 alleviates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by suppressing the Mff-required mitochondrial fission and Bnip3-related mitophagy via the JNK pathways. Redox Biol. 14, 576–587 (2018).

Zhang, C. X. et al. Mitochondria-targeted cyclosporin A delivery system to treat myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury of rats. J. Nanobiotechnol. 17(1), 18 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Lycopene protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 13, 2331–2342 (2019).

Ibarrola, J. et al. Myocardial injury after ischemia/reperfusion is attenuated by pharmacological Galectin-3 inhibition. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 9607 (2019).

Li, W. et al. PLCE1 promotes myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in H/R H9c2 cells and I/R rats by promoting inflammation. Biosci. Rep. 39(7), 66 (2019).

Nie, C. et al. Hydrogen gas inhalation alleviates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by the inhibition of oxidative stress and NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis in rats. Life Sci. 272, 119248 (2021).

Mizushima, N. & Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 147(4), 728–741 (2011).

Klionsky, D. J. et al. Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 40(19), e108863 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. HIF-1α/BNIP3 signaling pathway-induced-autophagy plays protective role during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 120, 109464 (2019).

Xing, Y. et al. Blunting TRPML1 channels protects myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by restoring impaired cardiomyocyte autophagy. Basic Res. Cardiol. 117(1), 20 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Resveratrol inhibits autophagy against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through the DJ-1/MEKK1/JNK pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 951, 175748 (2023).

Qin, G. W., Lu, P., Peng, L. & Jiang, W. Ginsenoside Rb1 Inhibits cardiomyocyte autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Chin. Med. 49(8), 1913–1927 (2021).

Zhou, Y. X., Zhang, H. & Peng, C. Puerarin: A review of pharmacological effects. Phytother. Res. 28(7), 961–975 (2014).

Han, Y. et al. Puerarin protects cardiomyocytes from ischemia-reperfusion injury by upregulating LncRNA ANRIL and inhibiting autophagy. Cell Tissue Res. 385(3), 739–751 (2021).

Xu, H. X. et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to the puerarin-induced cardioprotection via suppression of apoptosis and oxidative stress in a cell model of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Mol. Med. Rep. 20(1), 719–727 (2019).

He, H., Liu, P. & Li, P. Dexmedetomidine ameliorates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by enhancing autophagy through activation of the AMPK/SIRT3 pathway. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 17, 3205–3218 (2023).

Wang, D., Wang, D., Jin, Q. & Wang, X. Suxiao Jiuxin Pill alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced autophagy via miR-193a-3p/ALKBH5 pathway. Phytomedicine 125, 155359 (2024).

Harima, Y., Imayoshi, I., Shimojo, H., Kobayashi, T. & Kageyama, R. The roles and mechanism of ultradian oscillatory expression of the mouse Hes genes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 34, 85–90 (2014).

Fang, N. & Li, P. O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase OGT inhibits diabetic nephropathy by stabilizing histone methyltransferases EZH2 via the HES1/PTEN axis. Life Sci. 274, 119226 (2021).

Zheng, J., Li, J., Kou, B., Yi, Q. & Shi, T. MicroRNA-30e protects the heart against ischemia and reperfusion injury through autophagy and the Notch1/Hes1/Akt signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 41(6), 3221–3230 (2018).

Dong, Y. et al. Molecular machinery and interplay of apoptosis and autophagy in coronary heart disease. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 136, 27–41 (2019).

Song, H. et al. CREG protects from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating myocardial autophagy and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863(8), 1893–1903 (2017).

Tsai, C. F. et al. Paeonol protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury by mediating apoptosis and autophagy crosstalk. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 586498 (2020).

Wang, R. et al. Saponins in Chinese herbal medicine exerts protection in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: Possible mechanism and target analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 570867 (2020).

Jian, J., Xuan, F., Qin, F. & Huang, R. Bauhinia championii flavone inhibits apoptosis and autophagy via the PI3K/Akt pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 9, 5933–5945 (2015).

Yu, L. et al. Protective effect of berberine against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury: Role of Notch1/Hes1-PTEN/Akt signaling. Apoptosis 20, 796–810 (2015).

Robichaux, D. J., Harata, M., Murphy, E. & Karch, J. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore-dependent necrosis. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 174, 47–55 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Curculigoside attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Int. J. Mol. Med. 45(5), 1514–1524 (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82360057), and Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant No. 20224ACB206002, 20242BAB26115, 20232BAB206010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SQ‑L, and JC‑L conceived and designed the study. YY and HH performed cell experiments, data curation, and Visualization. TH and FJ‑F performed cell experiments and data analysis. CC-Z, XQ-W and MF contributed to methodology. All authors contributed to the original draft. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. SQ‑L and JC‑L revised the manuscript. SQ‑L and HH supervised the study and confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Y., Lai, S., Hu, T. et al. Puerarin pretreatment provides protection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibiting excessive autophagy and apoptosis by modulation of HES1. Sci Rep 15, 794 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84808-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84808-z