Abstract

Endometrial cancer (EC) is one of the few malignancies with increasing incidence and mortality rates. Targeted therapy and immunotherapy have become pivotal treatment strategies for EC patients. However, the current methods and biomarkers for predicting immunotherapy responses and prognosis are remain limited. Programmed cell death (PCD) pathways play a crucial role in cancer development and progression and may serve as prognostic markers and indicators of drug sensitivity in EC. In our study, we integrated multiple PCD pathways and comprehensive multi-omics datasets from TCGA-EC and GEO databases. By analyzing distinct PCD signatures, we discovered two major EC subgroups with distinctive prognoses, tumor microenvironment (TME) profiles, and responses to immunotherapy. To further investigate the cellular basis of these PCD patterns, single-cell RNA sequencing analysis was conducted to explore tumor heterogeneity in PCD characteristics across EC subpopulations. Further investigation revealed seven key PCD-associated genes (HIF3A, ACTL8, SIRPG, FBN3, ARHGAP30, CD6, and P2RY13) that formed the basis for a novel prognostic scoring system—risk score (RS). Our findings showed that patients with lower risk scores had better survival rates and improved immunotherapy outcomes. Conversely, patients with higher risk scores experienced poor clinical outcomes and reduced immunotherapy efficacy, although alternative therapies such as docetaxel and olaparib demonstrated potential therapeutic benefits. Overall, the RS provides a valuable tool for early prognosis prediction and for identifying patients who may benefit from immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among female malignancies globally, endometrial cancer (EC) ranks as the sixth most common cancer and the second most frequent gynecologic malignancy, with an estimated 417,000 cases worldwide in 2020. Over the past three decades, the incidence of this disease has increased dramatically by 132%1,2. While early detection is achieved in approximately 90% of cases, leading to favorable 5-year survival outcomes through surgical intervention alone or in combination with localized treatments, patients experiencing recurrence face significant challenges due to uncertainties surrounding the optimal adjuvant therapeutic strategies3,4. This clinical scenario highlights the urgent need for reliable predictive models for both survival outcomes and immunotherapy efficacy, enabling more personalized treatment approaches.

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically regulated process of active cellular elimination that plays a pivotal role in both organismal development and cancer progressiont5. This biological process includes several pathways, such as apoptosis, anoikis, autophagy, alkaliptosis, cuproptosis, entosis, entotic cell death, immunogenic cell death, ferroptosis, lysosome-dependent death, methuosis, necroptosis, netotic cell death, NETosis, oxeiptosis, pyroptosis, parthanatos, and paraptosis6. Recent studies have underscored the critical involvement of PCD mechanisms in tumor progression and treatment responses in EC. Pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory cell death, has emerged as a key player in EC. Specifically, the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway is implicated in mediating pyroptosis in response to chemotherapy and immune signaling, with studies showing that inhibiting pyroptosis can enhance EC cell survival and resistance to immune therapy7. Autophagy, a critical form of programmed cell death, has been shown to regulate immune responses in EC. Autophagy inhibits the expression of NLRC5 and its MHC-I gene in vitro. Notably, the autophagy protein MAP1LC3/LC3 interacts with NLRC5, thereby suppressing the NLRC5-mediated MHC-I antigen presentation pathway. This suggests a novel mechanism through which autophagy contributes to immune evasion in EC via NLRC5-mediated pathways8. Research has shown that ferroptosis-related gene expression is closely linked to the metabolic state of EC. By regulating iron metabolism and antioxidant defenses, these genes impact tumor cell survival and proliferation. Moreover, ferroptosis inducers have been found to activate T lymphocytes, thereby strengthening anti-tumor immune responses9. A study on a prognostic model related to necrosis in endometrial cancer suggests that two necrosis-associated miRNAs used in the study may serve as valuable prognostic markers for EC patients and are associated with immune cell infiltration. This implies that necrotic degeneration may contribute to the development of EC through its interaction with immune responses10. These mechanisms indicate that the PCD pathway is closely associated with the tumor immune microenvironment, influencing the effectiveness of immunotherapy.

The growing understanding of these PCD mechanisms has spurred the development of novel therapeutic strategies. A notable example is the successful FDA approval of a BCL-2 inhibitor targeting apoptotic pathways, which has demonstrated efficacy in lymphoma treatment11. Research has shown that inhibiting ferroptosis can lead to resistance against anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy12. Furthermore, the combination of the Akt/mTOR inhibitor and autophagy inducer Ibrilatazar (ABTL0812) with paclitaxel/carboplatin demonstrated both safety and feasibility, along with promising efficacy in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer13. In addition, statins have been reported to enhance antitumor immunity by promoting caspase-1/GSDMD-induced pyroptosis and synergistically inhibiting ARID1A-mutated clear cell ovarian cancer (OCCC) when combined with ICB therapy. Important implications for the development of therapeutic strategies targeting pyroptosis-related pathways are offered by the finding, with the potential to enhance anti-tumor immune responses in endometrial cancer14. Overall, these discoveries emphasize the importance of PCD research in advancing our understanding of EC pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention strategies. Therefore, gaining a comprehensive understanding of tumor-associated PCD mechanisms is crucial for developing innovative anti-cancer therapies.

Nevertheless, current research has yet to provide a thorough and integrated understanding of the role of PCD in EC. Given the centrality of PCD in EC, we identified seven PCD-related genes and constructed a prognostic signature, namely RS. This RS demonstrated strong predictive power in both training and validation datasets, forecasting patient outcomes, immunotherapeutic responses, and drug-based therapies. This signature facilitates more accurate patient stratification and personalized therapeutic decisions in the management of endometrial cancer.

Results

Identification of two distinct PCD-related EC clusters and their prognostic analysis

We established a comprehensive analytical framework, beginning with the compilation of signature gene sets representing 18 distinct cell death modalities, sourced from peer-reviewed literature and curated databases (detailed in Supplementary Table S1). Prior to the primary analysis, we conducted data quality assessment and batch effect evaluation using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), with the results visualized in Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B. A Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) was then performed on TCGA samples to assess PCD-related gene expression and obtain PCD scores. The heatmap analysis revealed that Oxeiptosis, Pyroptosis, Lysosome-dependent cell death, Ferroptosis, Entosis, and Apoptosis were significantly enriched in endometrial cancer tissues, while gene sets related to Autophagy, Alkaliptosis, and Anoikis were significantly enriched in normal endometrial tissues (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, we determined the optimal K-value that maximized intra-cluster coherence by employing several clustering performance evaluation metrics. These included the Consensus Cumulative Distribution Function (Consensus CDF) curve and the Delta Area graph. The Consensus CDF curve illustrates the cumulative distribution function of the consensus matrix for varying numbers of clusters (k), with a higher CDF value at a given k indicating a more robust clustering result. Additionally, the Delta Area graph was used to evaluate the relative change in clustering performance compared to the previous k − 1. The largest improvement in the Delta Area suggested that k = 2 was the optimal number of clusters, as it yielded the most significant enhancement in clustering performance. Based on this analysis, we stratified the TCGA-EC cohort (n = 522) into two distinct PCD-related subgroups: a high PCD cluster (C1, n = 291) and a low PCD cluster (C2, n = 231) (Fig. 1B–D). Box plots were generated to visualize the distribution of PCD scores within these two clusters. Notably, except for Parthanatos and Oxeiptosis, which exhibited higher PCD scores in the C2 cluster than in C1, almost all other cell death modalities showed higher scores in the C1 cluster (Fig. 1E). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis further demonstrated that the high PCD cluster (C1) had a better prognosis compared to the low PCD cluster (C2) (Fig. 1F).

Identification of two PCD-associated EC clusters. (A) GSVA of PCD-related genes in endometrial cancer and normal samples to calculate PCD scores. (B) Determination of the most appropriate K value based on the cumulative distribution curve. (C) Area under the cumulative distribution curve for each K value. (D) Consensus matrix heatmap representing the optimal number of clusters (k = 2) based on PCD gene selection. (E) Box plots illustrating the 18 programmed cell death scores across the two PCD-associated EC clusters. (F) Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival curves showing the differential overall survival (OS) between the two clusters.

Investigation of immunotherapy responses across the two PCD-related clusters

The high-PCD group exhibited significantly higher TIDE, dysfunction, and IFNG (interferon Gamma)scores, which suggest a more active and dysregulated tumor immune microenvironment (Fig. 2A–C). These elevated scores are indicative of increased immune cell infiltration, particularly cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which play a critical role in tumor surveillance. In contrast, the high-PCD group showed lower exclusion scores compared to the low-PCD group (Fig. 2D). The exclusion score represents the ability of the tumor to exclude immune cells. The lower exclusion score in the high - PCD group suggests enhanced immune cell infiltration into the tumor, suggesting a more favorable immune microenvironment for immune response. Further analysis of immunotherapy efficacy markers revealed increased tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) in the high-PCD group (Fig. 2E-F). TMB measures the number of mutations in the tumor genome, while MSI indicates the instability of microsatellite sequences. Both TMB and MSI are associated with improved responses to immunotherapy due to increased neoantigen presentation, suggesting that the high-PCD group may be more likely to benefit from immunotherapy. Additionally, a comprehensive analysis of 46 immune checkpoint genes, including key therapeutic targets like PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1), and CTLA4, revealed significant upregulation in the high-PCD group (Fig. 2G). The upregulation of these immune checkpoint genes suggests the presence of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, which is typically associated with tumors that may respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors. This increased expression implies that tumors in the high-PCD group might have a higher potential for response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy, which works by inhibiting signals that suppress the immune system, thereby reactivating anti-tumor immunity.

Investigation of immunotherapy responses across the two PCD-related clusters. (A–F) Comparison of immunotherapy response metrics between the two PCD clusters, including (A) TIDE score, (B) dysfunction score, (C) IFNG expression, (D) exclusion score, (E) tumor mutation burden (TMB), and (F) microsatellite instability (MSI). (G) Immune checkpoint-related gene expression levels across the two PCD clusters.

Variation of the TME across the two PCD groups

In addition to the observed differences in immunotherapy response, we further analyzed key biomarkers of the tumor microenvironment (TME) that may predict the efficacy of EC immunotherapy in both groups. ssGSEA revealed a significant increase in immune cell infiltration within the high PCD group, with nearly all 28 immune cell types showing elevated infiltration scores (Fig. 3A). This widespread increase in immune cell infiltration suggests a more immunologically active TME in the high PCD group. Further characterization using the ESTIMATE algorithm provided comprehensive functional assessments of the TME. The high PCD group exhibited higher ESTIMATE, immune, and stromal scores, and lower tumor purity scores compared to the low PCD group (Fig. 3B–E). The higher ESTIMATE score in the high PCD group reflects a more complex and potentially more immunogenic TME. This score combines information about both immune and stromal components, and a higher value indicates a richer mixture of non-tumor cells, which may contribute to the anti-tumor immune response. The increased immune score in the high PCD group directly indicates a higher level of immune cell infiltration. This is consistent with the ssGSEA results and further supports the idea that the high PCD group has a more active immune infiltrate, potentially enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy. Additionally, the higher stromal score in the high PCD group suggests a more abundant stromal component in the TME. Stromal cells are known to secrete cytokines and chemokines that can recruit immune cells and modulate their function. Thus, the presence of a more prominent stromal compartment may provide a more supportive microenvironment for immune cell activity. The lower tumor purity score in the high PCD group indicates that a smaller proportion of the tumor sample consists of tumor cells, while a larger proportion comprises non-tumor cells (immune and stromal cells). This further underscores that the high PCD group has a TME characterized by a higher degree of immune and stromal cell infiltration, which is generally associated with a better response to immunotherapy. Taken together, these findings suggest that the low PCD group harbors a more aggressive tumor phenotype with a less favorable TME, characterized by reduced immune cell infiltration and higher tumor purity. In contrast, the high PCD group has a TME more conducive to an effective anti-tumor immune response, which may explain the differences in immunotherapy efficacy observed between the two groups.

The TME landscape varies between the two PCD-related clusters. (A) Box plots illustrating ssGSEA-derived infiltration scores for 28 immune cell types, comparing the two PCD-related EC clusters. (B) ESTIMATE score, (C) immune score, (D) stromal score, and (E) tumor purity derived from the ESTIMATE algorithm, contrasting the two PCD clusters.

Development and prognostic significance of RS

To further investigate the differences in the PCD landscape across the two PCD-related clusters, we performed differential expression analysis at the transcriptomic level using the criteria of p < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1. As a result, a total of 441 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified (Supplementary Table S2), with 377 genes up-regulated and 64 genes down-regulated (Fig. 4A). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of these 441 DEGs showed significant enrichment in immune-related biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions. KEGG analysis revealed enrichment in pathways such as Cytokine − cytokine receptor interaction and Cell adhesion molecules15,16,17 (Fig. 4B and C). To further explore the prognostic implications of these differential genes, we conducted univariate Cox regression analysis. This identified genes significantly associated with overall survival (OS) in both the TCGA-EC and META cohorts (P < 0.05 for TCGA-EC and P < 0.01 for META). The intersecting genes from both cohorts were then used to identify seven hub genes, which were incorporated into the risk score (RS) development framework. Next, in the TCGA-EC training cohort, we evaluated 99 distinct algorithmic combinations to construct robust predictive models. Model performance was assessed across all cohorts using mean C-index calculations (Fig. 4D). Among the 99 models tested, the RSF algorithm consistently demonstrated the highest average C-index. Based on this, the final prediction model was constructed using the seven hub genes (Fig. 4E and F). The RS of each patient with EC was calculated according to the formula as follows:

Subsequently, the RS was calculated for each sample across all cohorts. In both the TCGA and META cohorts, patients with high RS exhibited significantly poorer clinical outcomes (Fig. 4G and H). The calibration curve showed good agreement with the actual survival rates at 1-, 3-, and 5-years in both the TCGA-EC and META cohorts (Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2C). Additionally, we have constructed time-dependent ROC curves for each cohort, specifically illustrating the AUC values at the 1-, 3-, and 5-year time intervals. (Supplementary Fig. S2B and S2D). Calibration curve and time-dependent ROC curve analysis show that our risk scoring model has good predictive performance at different time points.

Generation and prognostic significance of RS. (A) Volcano plot depicting DEGs between the two PCD-related EC clusters. (B) GO analysis of DEGs associated with PCD. (C) KEGG pathway analysis of PCD-related DEGs. (D) Integrated outcomes from 99 machine learning algorithms, with the C-index calculated for each model across the TCGA-EC and META cohorts. Models are ranked according to the average C-index. (E) Identification of RS hub genes using the RSF algorithm. (F) Results of univariate Cox regression analysis for hub genes in both the training and validation cohorts. (G–H) Survival analysis comparing high and low RS groups in both the TCGA-EC and META cohorts.

We conducted a more in-depth analysis to validate the prognostic implications of RS-related hub genes in EC by utilizing the Biomarker Exploration for Solid Tumors (BEST) database (https://rookieutopia.com/app_direct/BEST/). In addition, we performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and the results were largely consistent with the predictions derived from the RSF algorithm (Supplementary Fig. S3). Notably, we found that these genes were significantly associated with disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression-free interval (PFI) in EC, highlighting their considerable prognostic value (Supplementary Fig. S4 and S5). Furthermore, we employed the GSCALite public server (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/web/GSCALite/) to systematically assess the multi-omics profiles of RS across 32 cancer types from the TCGA database. The analysis revealed significant differential expression of these hub genes across various tumor types (Supplementary Fig. S6A). Additionally, we observed differences in RS gene copy number variations (CNVs) across cancer types (Supplementary Fig. S6B). Notably, SIRPG and ARHGAP30 exhibited the highest CNV frequencies, primarily as heterozygous amplifications (Supplementary Figs. S6C-S6E). Our epigenetic analysis further revealed pronounced differences in methylation patterns between tumor and normal tissues (Supplementary Fig. S7A), with a widespread inverse correlation between methylation status and mRNA expression in the majority of tumor types (Supplementary Fig. S7B). This suggests that epigenetic regulation could influence patient outcomes. Moreover, RS-related genes were shown to activate the pan-cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway, while simultaneously inhibiting the DNA damage response pathway (Supplementary Fig. S7C).

Clinical value of the RS

To thoroughly assess the performance of the RS signature in comparison with other prognostic markers, we conducted an extensive review of the literature from the past five years. As a result, we selected 17 distinct prognostic signatures from EC to serve as benchmarks in our analysis (Supplementary Table S3). These signatures span a range of biological functions, including immune response, immunotherapy efficacy, immune infiltration, and more. Notably, the RS signature demonstrated superior predictive power, as measured by the concordance index (C-index), in both the TCGA-EC and META datasets (Fig. 5A and B). Given the strong correlation between elevated RS levels and poor clinical outcomes in EC patients, we further explored the potential of RS as an independent prognostic marker. To validate its prognostic significance, we performed univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, which confirmed its substantial prognostic value (Fig. 5C and D). In order to enhance clinical applicability, we developed an integrated nomogram that combines RS with relevant clinical parameters to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival probabilities (Fig. 5E). This nomogram calculates a total score for each patient based on the sum of the individual scores assigned to each variable. Detailed information on the specific scores for each variable, as well as the formula for calculating the total score, can be found in Supplementary Table S4. The calibration curves for the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival predictions provided by the nomogram showed excellent agreement between predicted and observed outcomes (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, the time-dependent C-index curve revealed that RS exhibited the highest C-index among the clinical variables (Supplementary Fig. S8A). Decision curve analysis (DCA) further confirmed that RS provided a greater net benefit compared to other clinical variables (Supplementary Fig. S8B). Additionally, the area under the curve (AUC) for the 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival predictions based on RS was superior to that of other clinical variables (Supplementary Fig. S8C-E). To assess the robustness and generalizability of the nomogram, we performed an external validation using the META cohort. The calibration curves (Supplementary Fig. S9A) indicated strong consistency between the predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. The nomogram achieved AUC values of 0.665, 0.711, and 0.774 for predicting 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival, respectively, in the META cohort (Supplementary Fig. S9B). These results highlight the promising potential of the integrated nomogram for clinical application in predicting survival outcomes in endometrial cancer patients.

The clinical application of RS in practice. (A–B) Comparative performance analysis of RS versus 17 established prognostic models across the TCGA-EC and META cohorts. (C–D) Evaluation of prognostic factors using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, presented as forest plots. (E) Integrated nomogram incorporating RS to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival probabilities. (F) Model validation via calibration curves, comparing predicted and observed survival outcomes at 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals.

Immune characteristics related to RS

A comprehensive investigation of the EC tumor microenvironment, performed through IOBR computational analysis, uncovered distinct immune infiltration patterns across RS subgroups. The low-RS cohort exhibited significantly higher levels of various immune cell populations, including T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and macrophage lineages (Fig. 6A). These higher levels of immune cell infiltration suggest a more active immune response in the low-RS group, potentially indicating a more favorable tumor environment for immunotherapy. Additionally, molecular signatures associated with favorable responses to immunotherapy were notably enriched in the low-RS population (Fig. 6B). These findings suggest that a lower RS correlates with increased immune system activation and a more robust response to treatment. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) and tumor neoantigen burden (TNB) are established biomarkers used to assess patient response to immunotherapy. Furthermore, previous research by Sun et al. emphasized the pivotal role of M2 macrophages in the context of EC immunotherapy18. The low - RS group displayed greater enrichment of TMB and TNB (Fig. 6C–D). High TMB and TNB levels are linked to an increased likelihood of generating neoantigens that can be recognized by the immune system, thereby facilitating a stronger immune response against the tumor. The elevated TMB and TNB in the low-RS group suggest that the tumors in this cohort may be more immunogenic, and thus more likely to respond to immunotherapy. A reduction in the infiltration of M2 macrophages was observed in the low-RS group (Fig. 6E–F). M2 macrophages are known for their role in promoting tumor growth, angiogenesis, and immune suppression. Their reduced presence in the low-RS group indicates a less immunosuppressive TME, which may enhance the effectiveness of the anti-tumor immune response. This shift away from a dominant M2 macrophage population could allow the immune system to more efficiently target and eliminate tumor cells. Survival analysis further substantiated the potential of RS as a complementary factor to TMB, TNB, and M2 macrophages in predicting patient outcomes (Fig. 6G–I). Notably, a lower RS, in conjunction with higher TMB or TNB levels, or reduced M2 macrophage presence, was associated with improved survival prognosis for EC patients. The combination of these factors indicates a more favorable TME for immune - mediated tumor control. A lower RS may reflect a less aggressive tumor phenotype or a more active immune infiltrate, which, when combined with high TMB/TNB and low M2 macrophage levels, creates an environment where the immune system can effectively target and eliminate tumor cells. This synergy between different factors in the TME contributes to the improved survival outcomes observed in patients with these characteristics.

Immune characteristics related to RS. (A) Comparative analysis of immune cell infiltration signatures between RS subgroups in patient cohorts. (B) Distribution of immunotherapy biomarkers across high and low RS subgroups. (C–E) Distribution of TMB, TNB, and M2 macrophage infiltration between high- and low-RS patient cohorts. (F) Correlation analysis between RS and M2 macrophage infiltration. (G-I) Integrated survival analyses incorporating RS with TMB, TNB, and M2 macrophage parameters.

The substantial predictive capabilities of RS in response to immunotherapy

A comprehensive investigation was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of RS in predicting outcomes of immunotherapy in patients with EC. Our analysis began with an in-depth examination of the IMvigor-210 dataset, which provided a rich set of prognosis and treatment data from this patient cohort. Moving beyond traditional analytical approaches, we accounted for the characteristic delayed effects of immunotherapy by performing a comparative analysis of restricted mean survival (RMS) at both 6- and 12-month intervals. Additionally, we evaluated long-term survival (LTS) beyond the 3-month treatment period (Fig. 7A-B). Notably, patients classified in the low-risk category demonstrated enhanced therapeutic benefits, indicating a stronger response to immunotherapeutic interventions. To explore the biological underpinnings of these findings, we examined the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIP) framework, which allowed for a detailed assessment of immune cell infiltration in the low-risk cohort. The analysis revealed significant differences, particularly evident in the fourth and fifth steps of immune cell infiltration assessment, consistent with our previous observations (Fig. 7C). Specifically, there was a higher presence of certain immune cell types in the low-risk cohort, which are known to play critical roles in anti-tumor immunity, such as CD8 + T cells and activated dendritic cells. These findings suggest that the low-risk patients may have a more robust immune response, enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy. This could be due to a favorable tumor microenvironment that supports immune activation and infiltration, ultimately contributing to improved clinical outcomes. To further validate these findings, we employed the subclass mapping algorithm on an independent cohort of melanoma patients undergoing immunotherapy. This analysis corroborated the correlation between low RS values and an improved response to PD-1 therapy (Fig. 7D). Specifically, melanoma patients with low RS values exhibited a significantly higher likelihood of tumor regression, consistent with the immune activation observed in the EC cohort. Finally, we extended our validation efforts to several other immunotherapy cohorts with prognostic data. In these cohorts, a low RS was consistently associated with more favorable prognostic outcomes following immunotherapy. Specifically, this relationship was observed in the GSE78220 cohort (Fig. 7E), the GSE135222 cohort (Fig. 7F), and the GSE91061 cohort, where patients with a low RS exhibited enhanced prognostic outcomes (Fig. 7G). These results collectively reinforce the utility of RS as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy outcomes in EC and other malignancies, highlighting its role in shaping the tumor-immune landscape and enhancing therapeutic response.

The predictive potential of RS for EC patient response to immunotherapy. (A) Comparative analysis of restricted mean survival (RMS) intervals at 6-month and 1-year post-treatment timepoints between high and low RS groups. (B) Long-term survival (LTS) difference curves at 3 months of treatment for high- and low-RS groups. (C) Differences in immune activation at each TIP step between high- and low-RS groups. (D) Evaluation of immunotherapeutic outcomes across RS groups using the subclass mapping algorithm. (E–F) Survival analysis of RS groups in the GSE78220 and GSE135222 cohorts. (G) Distribution of RS across different immunotherapy response groups in the GSE91061 cohort.

Screening of potential therapeutic drugs

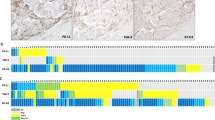

Given the significant prognostic differences between the high RS and low RS groups, and the limited immunotherapy response observed in high RS patients, we utilized the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP) and Profiling Relative Inhibition Simultaneously in Mixtures (PRISM) platforms to identify potential therapeutic drugs for this patient group. To validate our analytical framework, we assessed cisplatin sensitivity, a standard treatment option for EC, in order to determine the correlation between our algorithmic predictions and established clinical outcomes. Previous research has shown that germline pathogenic variants (GPVs) in BRCA1/2 are associated with an increased susceptibility to EC19. Our analysis revealed enhanced cisplatin responsiveness in patients with reduced BRCA1/2 expression, suggesting the potential for tailored chemotherapeutic strategies (Fig. 8A and B). As a result, we identified seven promising CTRP candidates (Olaparib, tretinoin, narciclasine, methotrexate, tamatinib, sorafenib, imatinib; Fig. 8C) and five PRISM candidates (docetaxel, vidarabine, daunorubicin, Olaparib, sorafenib; Fig. 8D). A subsequent PubMed literature review (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed/) highlighted Olaparib and docetaxel as particularly promising therapeutic options for high-RS patients. To further investigate the expression of hub genes in the RS model, we performed RT-PCR analysis to compare primary human endometrial epithelial cells (HEEC) with endometrial cancer (EC) cell lines (Ishikawa, HEC-1 A, RL-95-2). This analysis revealed distinct mRNA expression patterns for all seven regulatory factors between normal and cancerous cell lines (Fig. 8E). Notably, FBN3 showed the most significant differential expression between HEEC and EC cells, prompting further investigation through immunohistochemistry (IHC) in normal endometrial samples (n = 10) and EC specimens (n = 10). The IHC results confirmed that FBN3 expression was significantly elevated in EC tissues compared to normal endometrial samples (Fig. 8F).

Therapeutic agent screening for high-RS patients. (A–B) Evaluation of cisplatin sensitivity to assess the reliability of the algorithmic methodology. (C–D) Analysis of correlations and differences in drug sensitivity for potential compounds screened from the CTRP and PRISM datasets. (E) Comparison of relative mRNA expression of seven hub genes in human endometrial epithelial cells (HEEC) and EC cell lines (Ishikawa, HEC-1 A, RL-95-2). (F) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis showing FBN3 protein expression in EC tissues (n = 10) and normal endometrial tissues (n = 10); ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Characteristics of PCD in EC single-cell transcriptomics

Single-cell transcriptome data from five EC samples, obtained from the GSE 173,682 dataset, were comprehensively analyzed. A total of 13 distinct cell subpopulations were identified (Fig. 9A), with each cluster annotated based on specific marker genes. To highlight the unique characteristics of each cell cluster, a heatmap was generated to visualize the most representative marker genes, providing a detailed overview of the distinct profiles within the clusters (Fig. 9B). Subsequently, to evaluate programmed cell death (PCD) activity across different cell types in EC, the expression levels of 2228 PCD-related genes were examined across all identified cell populations (Fig. 9C). Among the 13 cell types analyzed, macrophages, endothelial cells, unciliated epithelia 1 cells, and unciliated epithelia 2 cells demonstrated significantly higher PCD activity compared to other cell types (Fig. 9D). Furthermore, we explored the expression patterns of hub genes within the tumor microenvironment. Interestingly, the seven identified hub genes were predominantly expressed in stromal fibroblasts, suggesting their crucial role in the functional activities of this particular cell type (Fig. 9E–K). This finding highlights the importance of stromal fibroblasts in the regulation of PCD within the TME of EC.

Characteristics of PCD in EC single-cell transcriptomics. (A) Classification of cell types based on specific marker genes. (B) Heatmap illustrating the most representative marker genes for each identified cell cluster. (C) PCD activity scores across various cell populations. (D) Distribution of PCD scores among different cell types. (E–K) Expression levels of RS hub genes across different cell types.

Discussion

Cell death processes are crucial for maintaining organismal homeostasis, facilitating developmental progression, and preventing uncontrolled cell growth20. Recent studies have highlighted strong associations between PCD and clinical outcomes across various cancer types, impacting both prognostic assessment and treatment strategies21,22. A key development in this field is the creation of the PCD-based Cancer Cell Death Index (CCDI) by Cao et al., a comprehensive model that evaluates prognosis and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients23. Furthermore, Zou et al. emphasized the critical role of PCD in determining treatment strategies and outcomes for triple-negative breast cancer21. Despite significant advances, current research on EC has largely focused on individual PCD mechanisms, such as ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and anoikis24,25,26leaving the collective impact of PCD patterns in EC insufficiently explored. To address this gap, our study provides a comprehensive analysis of the PCD landscape, identifying two distinct PCD-related EC clusters and developing a prognostic signature (RS) capable of predicting both clinical outcomes and therapeutic efficacy in EC patients.

Through consensus clustering analysis based on PCD scores, we identified two distinct PCD clusters within our cohort. Survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier methodology demonstrated a significantly better prognosis in the PCD-high cluster compared to the PCD-low cluster. Previous research has established that tumor microenvironment interactions substantially influence patient survival rates and immunotherapeutic efficacy27,28with PCD playing a pivotal role in modulating the tumor immune microenvironment23,29. Our analysis revealed substantial differences between the PCD-high and PCD-low clusters across various indicators, including overall survival, immune environment, mutational characteristics, TMB, chemotherapeutic effectiveness, and drug resistance patterns. Specifically, the PCD-high cluster exhibited enhanced survival rates, elevated immune/stromal/estimate scores, and reduced tumor purity, suggesting an increased potential for immune response activation.

Endometrial cancers frequently present with Mismatch Repair-deficient (dMMR) and microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) characteristics, which account for approximately 25–30% of cases30,31,32. The increased expression of programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2), coupled with a high tumor mutation burden, are characteristic of dMMR-MSI-H tumors, rendering them potentially sensitive to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies30,33,34,35. In line with these findings, our study observed a higher frequency of MSI-H and elevated expression of checkpoint genes, including PDCD1, CD274, and CTLA4, in the PCD-high cluster. These molecular alterations correlated with improved survival outcomes and a more favorable response to immunotherapy, consistent with prior research.

The seven hub genes identified in our PCD-based prognostic model play significant role in tumor microenvironment regulation, immunotherapeutic response, and cancer development. For instance, research has identified novel immunosuppressive functions of Signal Regulatory Protein Gamma (SIRPG), with increased SIRPG expression being associated with enhanced efficacy of PD-1 blockade in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and melanoma36. As a transmembrane glycoprotein, SIRPG enhances cancer stem-like properties in lung cancer cells, facilitating immune evasion through the upregulation of CD4737. This suggests that SIRPG could be a potential target for improving the effectiveness of immunotherapy in certain cancers. ACTL8, a cancer/testis antigen family member, is upregulated in cancers like gastric cancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma, promoting tumor progression38,39. Its expression patterns indicate that it might serve as a potential therapeutic target, potentially influencing the tumor microenvironment and immune cell behavior, although the exact mechanisms of its impact on immune cell infiltration and the tumor microenvironment in the context of immunotherapy remain to be further elucidated. CD6, almost exclusively expressed by lymphocytes, including the majority of mature T cells and approximately 50% of NK cells, plays a crucial role in immune regulation40. Anti-CD6 monoclonal antibodies may offer a novel approach to cancer immunotherapy by modulating autoimmunity through CD4 + lymphocyte differentiation and enhancing cancer cell killing via CD8 + T cells and NK cells41. Additionally, CD6’s ligand, CD166, represents an ideal target for chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy. CD6-CAR-T cells have shown promise in targeting and eliminating CD166-positive human colorectal cancer stem cells, providing a potential immunotherapy strategy42. FBN3 mutations are more prevalent in gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas compared to non-gastrointestinal malignancies43. Although no direct immunotherapeutic targets have been developed for FBN3, the mutation status of FBN3 may influence the tumor microenvironment and immune cell function by modulating the expression of key immune-related genes and cytokines. Hypoxia-inducible factor 3 subunitα (HIF3A), a member of the HIF transcription factor family, regulates genes involved in inflammatory responses and oncogenic processes44. Elevated expression of HIF3A has been observed in ovarian cancer, where it promotes disease progression, highlighting its potential as a target for therapeutic intervention45. P2RY13 is implicated in various immune functions in lung adenocarcinoma, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, chemokine signaling, and B cell receptor signaling pathways46. Additionally, P2RY13 is a characteristic gene of the microglial inflammatory program, promoting lymphocyte infiltration and interacting with neurons to maintain brain homeostasis, suggesting its broader relevance in immune modulation47. ARHGAP30, a Rho GTPase-activating protein, regulates cell adhesion and stress fiber formation through its interaction with Wrch-148. In lung adenocarcinoma, ARHGAP30 expression is positively correlated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), immune-stimulating factors, MHC molecules, chemokines, and chemokine receptors49this suggests that ARHGAP30 may influence the tumor microenvironment by modulating immune cell infiltration and function. Collectively, these findings validate the ability of our RS model to provide accurate immunological and prognostic assessments in patients with EC. Our analysis revealed significantly improved survival rates among patients with a low RS. The predictive robustness of the RS model was further validated through comprehensive KM and ROC curve analyses across both the training and validation datasets. When compared to previously established models, our RS framework demonstrated superior predictive accuracy and consistency. Notably, the practical utility of the RS model exceeded that of traditional clinical parameters, providing an efficient and reliable tool for predicting survival outcomes in EC. However, it is important to note that this comparison was primarily based on the C-index, which does not fully capture the underlying biological differences among the models. For instance, our models incorporate immune-related genes, which may influence their predictive performance. Future work will explore the biological basis of our RS model and investigate the potential integration of immune-related genes to further enhance its predictive power.

Patients in the low-RS group exhibited elevated TMB and TNB levels, as well as increased infiltration of various immune cell populations. These findings suggest a potential enhancement of antitumor immune responses50. Superior survival outcomes were consistently observed in this group across multiple immunotherapy cohorts. Moreover, subclass mapping analysis confirmed that low-RS patients had an improved immunotherapeutic response, further corroborating our findings. These results underscore the potential utility of RS in the early identification of populations likely to respond to immunotherapy. Given the suboptimal immunotherapy outcomes observed in high-RS patients, we employed a validated drug screening framework to identify potential therapeutic alternatives51,52, ultimately identifying olaparib and docetaxel as promising candidates. The groundbreaking DUO-E trial demonstrated significant clinical benefits when combining immunotherapy with olaparib, a PARP inhibitor, in advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer patients. Notably, this combination therapy enhanced the efficacy of ICIs, resulting in improved PFS outcomes across all MMR status categories53. Furthermore, clinical benefits were observed in both the intention-to-treat and proficient MMR populations with the addition of durvalumab to carboplatin/paclitaxel, followed by durvalumab + olaparib, compared to carboplatin/paclitaxel alone, in a separate DUO-E trial, regardless of the RCA1/BRCA2 mutation status54. According to the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2023), docetaxel is considered a primary therapeutic option for recurrent endometrial cancer55. Adjuvant chemotherapy with docetaxel/cisplatin, followed by radiation therapy, has demonstrated benefits for patients with high-risk factors, with manageable toxicities56. Additionally, research has shown that taxane compounds, such as docetaxel, promote T cell-mediated cytotoxic vesicle release, inducing cancer cell apoptosis. These agents enhance cancer cell elimination through both T cell receptor-dependent and -independent mechanisms, highlighting their potential for developing more effective and less toxic anticancer therapeutics57.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis was constrained by the sample size and the reliance on publicly available datasets, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, the molecular mechanisms underlying the influence of RS-associated genes on tumor development remain incompletely understood and warrant further investigation. Furthermore, our study lacks direct experimental validation in EC cell lines or animal models, which is essential for confirming the biological impact and therapeutic potential of the identified candidates. To address these gaps, future research will include in vitro and in vivo experiments. Lastly, the comprehensive validation of the clinical utility of RS will necessitate larger-scale, prospective studies conducted across multiple clinical centers. This will help to confirm its predictive accuracy and applicability in diverse clinical settings.

Conclusions

We successfully developed a novel prognostic model, RS, based on PCD-related signatures. This model demonstrated promising predictive capabilities for patient outcomes across diverse cohorts and effectively indicated immunotherapeutic responsiveness. In addition to its prognostic value, the model also addresses therapeutic challenges, particularly in high-RS patients who exhibited limited efficacy to immunotherapy. Through our analysis, we identified docetaxel and Olaparib as potential alternative treatments for these patients. Thus, the PCD-based RS model not only serves as a valuable tool for predicting EC patient outcomes but also plays a critical role in guiding therapeutic decision-making. By offering innovative approaches to treatment, it holds significant promise for the clinical management of EC patients.

Materials and methods

Data source

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data, along with corresponding clinical information, were obtained from two major databases: Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga/). For our analysis, we incorporated eight distinct cohorts:: TCGA-EC, GSE26193, GSE140082, GSE78220, GSE91061, GSE135222, GSE 173,682 and IMvigor210, with the latter sourced from published research58. In cases where multiple probes detected the same gene, the expression values were averaged to provide a consolidated representation. To ensure comparability across cohorts, all gene expression data were preprocessed as follows: (1) log2 transformation (for RNA-seq counts: log2(x + 1)) to reduce skewness; (2) removal of low-expression genes (mean TPM < 1 in all samples); (3) Z-score normalization ((x − µ)/σ) applied to transformed data to standardize feature scales for machine learning. For microarray data, quantile normalization (limma R package) was additionally performed to align inter-sample distributions. This approach enabled the harmonization of the data, allowing for more reliable downstream analysis.

The TCGA-EC dataset served as our primary training cohort, while GSE26193 and GSE140082 were used for model validation. To evaluate the model’s performance in predicting immunotherapy response, we further analyzed data from four independent clinical trials investigating immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatments. These trials spanned various cancer types and therapeutic strategies: the IMvigor210 study, which assessed anti-PD-L1 therapy in metastatic urothelial carcinoma; GSE78220, which focused on anti-PD-1 treatment in melanoma patients; GSE91061, which examined combination anti-CTLA4/PD-1 therapy in melanoma; and GSE135222, which investigated anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in non-small cell lung carcinoma. This comprehensive analysis allowed us to assess the model’s applicability and robustness across different clinical contexts and treatment regimens.

A comprehensive search for PCD-associated genes was conducted across multiple databases and literature sources, including the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB), GeneCards, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), as well as relevant review publications59,60,61,62. The search yielded gene sets corresponding to a wide range of cell death pathways. These pathways included apoptosis (580 genes), pyroptosis (52 genes), ferroptosis (88 genes), autophagy (367 genes), necroptosis (101 genes), cuproptosis (19 genes), parthanatos (9 genes), entotic cell death (15 genes), netotic cell death (8 genes), lysosome-dependent cell death (220 genes), alkaliptosis (7 genes), oxeiptosis (5 genes), NETosis (24 genes), immunogenic cell death (34 genes), anoikis (338 genes), paraptosis (66 genes), methuosis (8 genes), and entosis (23 genes), as summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Identification of PCD-associated clusters in EC

Using the derived PCD score as a classification metric, we conducted a cluster analysis on the TCGA-EC dataset with the ‘ConsensusClusterPlus’ R package to identify distinct PCD-related clusters of EC. The clustering approach utilized Euclidean distance calculations combined with agglomerative k-means algorithms. Specifically, 1000 iterations were performed, with each iteration sampling 80% of the cases to ensure robustness and consistency of the results. To further assess the clinical relevance of the identified clusters, survival differences between them were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. This allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the prognostic implications of the PCD-related clusters in EC.

Evaluation of the immunotherapy response in EC

To analyze immune cell infiltration patterns across different PCD subgroups, we employed the single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) methodology, a variant of the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) algorithm, which enabled the examination of 28 distinct immune cell populations. Additionally, the ‘ESTIMATE’ package was used to quantify immune, stromal, and ESTIMATE scores, along with tumor purity, thereby generating corresponding scores to characterize the tumor microenvironment. To further explore the immune landscape, we assessed the expression patterns of immune checkpoint molecules using Spearman correlation analyses.

Immunotherapy response patterns were evaluated through multiple approaches. First, patient-specific TIDE scores were calculated using the TIDE platform (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) based on TCGA-EC expression data63. The response classification was determined using TIDE score thresholds: positive scores indicated non-responders, while negative scores suggested responders. Comparative analysis between the PCD clusters included the evaluation of Dysfunction, IFNG, and Exclusion signatures to provide deeper insights into immune evasion mechanisms. Moreover, additional immunotherapy response indicators, such as tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) status, were also examined. TMB calculations were performed using the R package “maftools” with mutation data, while MSI information was extracted from cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/)64,65.

Establishment of a RS prognostic signature

The expression matrix of genes associated with PCD was first extracted to identify relevant molecular features. Next, DEGs between tumor and control specimens were identified using the ‘edgeR’ R package, with cutoff criteria set at log2|fold change| > 1 and an adjusted p-value (padj) < 0.05. Volcano plots were then generated and visualized using the ‘ggplot2’ R package to provide a clear depiction of these DEGs. To further investigate the molecular processes and biological pathways associated with PCD in endometrial cancer, GO and KEGG pathway analyses were conducted. These analyses were performed using the ‘clusterProfiler’ R package, allowing for the assessment of all DEGs related to PCD. Statistical significance for all analyses was determined using a threshold of p < 0.05.

Following a univariate Cox regression analysis of the previously described PCD-related characteristics, several significant prognostic PCD-related features were further selected using the TCGA-EC (p < 0.05) and META (p < 0.01) standard “survival” R package. To ensure comparability across different cohorts, all data underwent preprocessing, which included Z-score normalization. Subsequently, to assess the correlation between the RS, immunotherapy, and prognosis, we designated the TCGA-EC cohort, which included comprehensive treatment details, as the training set, while the META cohorts were used as validation sets. The META cohort was created by integrating the GSE26193 and GSE140082 datasets. To eliminate batch effects, the datasets were merged using the “comBat” function from the sva package. The adjustment was performed using an empirical Bayesian framework to account for systematic differences between batches. The effectiveness of batch effect removal was assessed before and after correction using principal component analysis (PCA) (Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B).

The development of our comprehensive risk score model incorporated ten distinct machine learning approaches: CoxBoost, stepwise Cox regression, Lasso, Ridge regression, elastic net (Enet), survival-SVMs, GBMs, SuperPC, plsRcox, and RSF. Model training was conducted using the TCGA-EC dataset as the primary cohort. For the RSF model, we utilized the randomForestSRC package and used the “rfsrc” function with two important parameters: “ntree” and “nodesize.” The parameter “ntree” represents the number of trees in the random forest, while “nodesize” represents the minimum size of the terminal nodes. In this study, we set “ntree” to 1,000 and “nodesize” to 5.For the CoxBoost model, we first called the “optimCoxBoostPenalty” function to determine the optimal penalty (shrinkage) value. We then combined this with cross-validation to perform 10-fold cross-validation on the CoxBoost model to search for the best number of boosting steps. Finally, the “CoxBoost” function was used to fit the model. The stepwise cox analysis was performed using the survival package, and the complexity of the statistical model was evaluated based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). We calculated all possible combinations for the direction parameter, including “both,” “backward,” and “forward.” Lasso, Ridge, and Enet models were implemented using the glmnet package and the “cv.glmnet” function. The regularization parameter lambda was determined through 10-fold cross-validation, while the tradeoff parameter alpha was set between 0 and 1 (interval = 0.1). When alpha is equal to 1, Lasso is executed, while Ridge is executed when alpha is equal to 0. For other values of alpha, Enet is executed. The survival-SVM model was implemented using the “survivalsvm” function from the survivalsvm package, which employs support vector analysis on datasets with survival outcomes. The GBM model was implemented using the gbm package. The “gbm” function was used with 10-fold cross-validation to fit a GBM. The SuperPC model was implemented using the superpc package, which is an extension of PCA. The “superpc.cv” function was also used with 10-fold cross-validation. For the plsRcox model, the “cv.plsRcox” function of the plsRcox package was used.

The RS development pipeline is outlined below

-

•We performed differential expression analysis of the two PCD-related clusters at the transcriptomic level, applying a threshold of p < 0.05 and |log2FC| > 1, to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs). In addition, univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted on these PCD-related DEGs, and prognosis-related genes significantly associated with overall survival (OS) were screened from both the TCGA-EC and META cohorts (with p < 0.05 for TCGA-EC and p < 0.01 for META). The intersection of these genes from both cohorts was taken to identify the hub genes.

-

• Ten machine learning algorithms were applied, utilizing 99 different combinations to construct the most predictive RS, with optimization focused on achieving the best concordance index (C-index) performance.

-

• Following model training on the training set, all validation cohorts were subsequently tested. The average C-index for each model was calculated, and the model exhibiting the highest C-index value was selected as the optimal one.

Prognostic value and potential clinical applications of RS

Based on the resulting model, we assigned scores to each sample in both the training and validation sets, subsequently categorizing them into high-RS and low-RS groups. The prognostic significance of the RS was then assessed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves to evaluate survival outcomes across these two groups. Additionally, we systematically identified 17 prognostic features associated with endometrial cancer and calculated a score for each sample using previously published coefficients. To evaluate the predictive performance of all signatures in each cohort, we utilized the C-index. To enhance the clinical applicability of the RS, we constructed a clinical nomogram integrating factors derived from multivariate Cox regression analysis. Model performance was assessed using several metrics, including the time-dependent C-index to measure discriminative ability, calibration curves for evaluating prediction accuracy, and decision curve analysis to assess potential patient benefits. Furthermore, we analyzed the temporal predictive performance using the “survivalROC” package, which generated time-dependent ROC curves and the corresponding AUC values at 1-, 3-, and 5-year timepoints, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s predictive accuracy over time.

A comprehensive study of immunotherapy response and immune-omics molecular profiling utilizing RS

We collected several established markers related to tumor microenvironment (TME) cell types and immunotherapy responses using the IOBR package66. To analyze immunological differences between patients with high and low risk scores (RS), we applied a unified approach, calculating an enrichment score for each sample. This allowed us to contrast various factors such as tumor mutational burden (TMB), tumor neoantigen burden (TNB), and the presence of M2 macrophages between the two cohorts. Based on these differences, patients were subsequently recategorized according to their RS. To assess the efficacy of immunotherapy, we initially analyzed the survival response delay to immunotherapy in these patients. We further evaluated the immunotherapy response by examining patients’ survival delays and utilized a combination of the TIP algorithm and subclass mapping to estimate the response67. To ensure the reliability of our findings, we conducted external validation studies across three independent cohorts: GSE7822068, GSE13522269, and GSE9106169.

Identification potential therapeutic drugs for high RS patients

Expression data for human cancer cell lines (CCLs) were obtained from the Broad Institute Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE). Drug sensitivity data for these CCLs were sourced from two datasets: the CTRP v.2.0 dataset (available at https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ctrp) and the PRISM repurposed drug dataset (19Q4, accessible at https://depmap.org/portal/prism/). To assess drug sensitivity, we employed the area under the dose-response curve (AUC) as a key metric.

Cells and cell cultures

We maintained human endometrial epithelial cells (HEEC) as well as established endometrial cancer (EC) cell lines, including Ishikawa, HEC1A, and RL952, in our laboratory. The growth conditions for HEEC, Ishikawa, and RL952 cells were standardized using RPMI1640 medium (Gibco, USA), supplemented with 10% OriCell fetal bovine serum (New Zealand origin) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a controlled environment with 5% CO2 and optimal humidity to promote consistent growth. In contrast, for HEC1A cells, McCoy’s 5 A medium (Gibco, USA) was used as the culture substrate.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

RNA was extracted using the Axygen RNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the RNA using the cDNA reverse transcription kit (Genstar). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using StepOne™ and StepOnePlus™ real-time PCR systems, with amplification carried out using SYBR Select Master Mix.The primer sequences for the seven hub genes were as follows:

HIF3A: forward (homo-F): GCTCATCTGCGAAGCCATCC, reverse (homo-R): GTACTCGTAGGCGGAACAGC; ACTL8: forward (homo-F): GAACCACAGACGGGAGCAAG, reverse (homo-R): CGATGGGACATGCAGCAACT; SIRPG: forward (homo-F): TCTTCGTGGGACTGCCAACT, reverse (homo-R): GACAGCTATGAGGAGCAGCG; FBN3: forward (homo-F): CATGGCTCAGGCTACACTGC, reverse (homo-R): GATGCACTCCCCATGAGCAC; ARHGAP30: forward (homo-F): CTGTCCCAAACTACAGGACC, reverse (homo-R): ACGATGGATTGTACCCGCAC; CD6: forward (homo-F): GTGTCACCTGTGCAGAGAAC, reverse (homo-R): TCATCGCACACTGATCCCCA; P2RY13: forward (homo-F): GTATCCTCCCAAAGGTGACACT, reverse (homo-R): TATTCAGCAGGATGCCGGTC. GAPDH was used as an internal control, and data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method to determine relative gene expression levels.

Immunohistochemical staining

We collected endometrial cancer tissue samples from 10 patients who had been pathologically diagnosed with endometrial cancer and had not received any prior therapeutic interventions, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy. The control group consisted of normal endometrial tissues obtained from 10 patients undergoing total hysterectomy for benign conditions, including cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and uterine prolapse. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Liuzhou, China). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their enrollment in the study. All experiments conducted in this study adhered to the ethical guidelines and regulations set forth by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University. For the detection of FBN3 protein, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections. The protocol began with methanol-based deparaffinization, followed by antigen retrieval in EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) using heat-mediated methods. After blocking for 30 min, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary FBN3 antibody (Cloud-Clone Corp, PAA381Hu01, 1:250 dilution). Subsequently, the sections were exposed to an HRP-conjugated rabbit IgG secondary antibody at room temperature. Images were captured using an Olympus BX43 microscope. Quantitative analysis was performed using a dual scoring system. The percentage of immunopositive cells was assessed under high magnification (200×) and classified as follows: score 1 (0–25%), score 2 (25–50%), score 3 (50–75%), or score 4 (75–100%). The intensity of the staining was graded on a scale of 0–3: negative (0), weak (1), moderate (2), or strong (3). The final immunoreactivity score (IRS) was calculated by multiplying the percentage of immunopositive cells with the staining intensity score for each high-magnification field.

Processing of single-cell transcriptomic data

Single-cell expression matrices from five EC samples were retrieved from the GEO database (GSE173682). Doublets were identified and removed using DoubletFinder (version 2.0.3). Cells with more than 15% mitochondrial gene content, fewer than 200 expressed genes, or more than 6,000 expressed genes were classified as doublets and excluded. Additionally, ribosomal genes were removed. To scale down and cluster the single-cell expression data, Seurat 4.0.1 (with parameters: resolution = 1, PC = 1:30) was employed, following batch effect correction using the Harmony package. Cell types were annotated using SingleR and conventional cell markers. The FindAllMarkers function was then utilized to identify highly expressed genes in each subpopulation, applying the criteria of log2|fold-change| > 0.25 and p_adj < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Between-group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-tests for normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed variables. For multi-group comparisons, one-way ANOVA was applied to parametric data, while the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for non-parametric data. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using two-sided Fisher’s exact tests. The cutoff value for the RS score was determined using the “surv-cutpoint” function from the survminer package. All potential cutoff points were tested repeatedly to identify the one that maximized the rank statistics. Subsequently, the two-class classification method was applied to categorize the RS score. Based on the selected maximum logarithmic rank statistics, patients were classified into high- and low-score groups within each cohort, helping to minimize computational batch effects. The screening of differentially expressed genes was conducted using the limma R package. The data underwent log2 transformation and quantile normalization to eliminate technical biases. The significance threshold was set as |log2FC| >1 and FDR-adjusted p< 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Crosbie, E. J. et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 399, 1412–1428. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00323-3 (2022).

McEachron, J. et al. Evaluation of survival, recurrence patterns and adjuvant therapy in surgically staged High-Grade endometrial Cancer with retroperitoneal metastases. Cancers (Basel) 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13092052 (2021).

Rauh-Hain, J. A. & Del Carmen, M. G. Treatment for advanced and recurrent endometrial carcinoma: Combined modalities. Oncologist 15, 852–861. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0091 (2010).

Liu, J. et al. Programmed cell death tunes tumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 13, 847345. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.847345 (2022).

Galluzzi, L. et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell. Death Differ. 25, 486–541. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4 (2018).

Su, P. et al. ERRα promotes glycolytic metabolism and targets the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway to regulate pyroptosis in endometrial cancer. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 42 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-023-02834-7 (2023).

Zhan, L. et al. LC3 and NLRC5 interaction inhibits NLRC5-mediated MHC class I antigen presentation pathway in endometrial cancer. Cancer Lett. 529 (2022).

Zalyte, E. & Ferroptosis metabolic rewiring, and endometrial Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010075 (2023).

Zhang, Q., Luo, Y., Zhang, S., Huang, Q. & Liu, G. Development of a necroptosis-related prognostic model for uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 14, 4257. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54651-3 (2024).

Carneiro, B. A. & El-Deiry, W. S. Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0341-y (2020).

Jiang, Z. et al. TYRO3 induces anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy resistance by limiting innate immunity and tumoral ferroptosis. J. Clin. Invest. 131. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI139434 (2021).

Leary, A. et al. ENDOLUNG trial. A phase 1/2 study of the akt/mtor inhibitor and autophagy inducer Ibrilatazar (ABTL0812) in combination with paclitaxel/carboplatin in patients with advanced/recurrent endometrial cancer. BMC Cancer 24 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12501-5 (2024).

Zhou, W. et al. Targeting the mevalonate pathway suppresses ARID1A-inactivated cancers by promoting pyroptosis. Cancer Cell 41, 740–756 e710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2023.03.002 (2023).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Sun, Y., Jiang, G., Wu, Q., Ye, L. & Li, B. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in the progression, prognosis and treatment of endometrial cancer. Front. Oncol. 13, 1213347. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1213347 (2023).

Sherman, M. E. & Foulkes, W. D. BRCA1/2 and endometrial cancer risk: Implications for management. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 113, 1127–1128. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab037 (2021).

Bertheloot, D., Latz, E. & Franklin, B. S. Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 18, 1106–1121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-020-00630-3 (2021).

Zou, Y. et al. Leveraging diverse cell-death patterns to predict the prognosis and drug sensitivity of triple-negative breast cancer patients after surgery. Int. J. Surg. 107, 106936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106936 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. Implications of different cell death patterns for prognosis and immunity in lung adenocarcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol. 7, 121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-023-00456-y (2023).

Cao, K. et al. Analysis of multiple programmed cell death-related prognostic genes and functional validations of necroptosis-associated genes in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. EBioMedicine 99, 104920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104920 (2024).

Wang, R. et al. Screening for ferroptosis genes related to endometrial carcinoma and predicting of targeted drugs based on bioinformatics. Arch. Toxicol. 98, 3155–3165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-024-03783-6 (2024).

Chen, Y. Identification and validation of Cuproptosis-Related prognostic signature and associated regulatory axis in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma. Front. Genet. 13, 912037. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.912037 (2022).

Chen, S., Gu, J., Zhang, Q., Hu, Y. & Ge, Y. Development of biomarker signatures associated with Anoikis to predict prognosis in endometrial carcinoma patients. J. Oncol. 2021, 3375297. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3375297 (2021).

Fu, Y., Liu, S., Zeng, S. & Shen, H. From bench to bed: the tumor immune microenvironment and current immunotherapeutic strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38, 396. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-019-1396-4 (2019).

Dou, Y. et al. Proteogenomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Cell 180, 729–748 e726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.026 (2020).

Xiao, L. et al. Exploring a specialized programmed-cell death patterns to predict the prognosis and sensitivity of immunotherapy in cutaneous melanoma via machine learning. Apoptosis 29, 1070–1089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-024-01960-7 (2024).

Dudley, J. C., Lin, M. T., Le, D. T. & Eshleman, J. R. Microsatellite instability as a biomarker for PD-1 Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 813–820. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1678 (2016).

Luchini, C. et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: A systematic review-based approach. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1232–1243. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz116 (2019).

Bonneville, R. et al. Landscape of microsatellite instability across 39 Cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017 https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00073 (2017).

Kloor, M. & von Doeberitz, K. The immune biology of microsatellite-unstable cancer. Trends Cancer 2, 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2016.02.004 (2016).

Rousseau, B. et al. PD-1 blockade in solid tumors with defects in polymerase epsilon. Cancer Discov. 12, 1435–1448. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0521 (2022).

Le, D. T. et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 Blockade. Science 357, 409–413. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan6733 (2017).

Luo, L. et al. SIRPG expression positively associates with an inflamed tumor microenvironment and response to PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 73, 147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-024-03737-y (2024).

Xu, C. et al. SIRPgamma-expressing cancer stem-like cells promote immune escape of lung cancer via Hippo signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 132 https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI141797 (2022).

Yu, W. et al. ACTL8 promotes the progression of gastric cancer through PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Dig. Dis. Sci. 69, 3786–3798 (2024).

Wang, L., Xing, X., Tian, H. & Fan, Q. Actin-like protein 8, a member of cancer/testis antigens, supports the aggressive development of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via activating cell cycle signaling. Tissue Cell 75, 101708 (2022).

Braun, M. et al. The CD6 scavenger receptor is differentially expressed on a CD56 natural killer cell subpopulation and contributes to natural killer-derived cytokine and chemokine secretion. J. Innate Immun. 3, 420–434 (2011).

Ruth, J. H., Gurrea-Rubio, M., Athukorala, K. S., Rasmussen, S. M. & Fox, D. A. CD6 is a target for cancer immunotherapy. JCI Insight 6 (2021).

He, S. et al. CD166-specific CAR-T cells potently target colorectal cancer cells. Transl. Oncol. 27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101575 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Comparative molecular analysis of gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Cell 33, 721–735 e728 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.010

Makino, Y. et al. Inhibitory PAS domain protein is a negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible gene expression. Nature 414, 550–554. https://doi.org/10.1038/35107085 (2001).

Zhang, C. et al. LINC01342 promotes the progression of ovarian cancer by absorbing microRNA-30c-2-3p to upregulate HIF3A. J. Cell. Physiol. 235, 3939–3949. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.29289 (2020).

Lin, J., Wu, C., Ma, D. & Hu, Q. Identification of P2RY13 as an immune-related prognostic biomarker in lung adenocarcinoma: A public database-based retrospective study. PeerJ 9 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11319 (2021).

Miller, T. E. et al. Programs, origins and Immunomodulatory functions of myeloid cells in glioma. Sci. Rep. 15 (2025).

Kreider-Letterman, G., Carr, N. M. & Garcia-Mata, R. Fixing the GAP: the role of RhoGAPs in cancer. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2022.151209 (2022).

Hu, S. et al. DNA methylation of ARHGAP30 is negatively associated with ARHGAP30 expression in lung adenocarcinoma, which reduces tumor immunity and is detrimental to patient survival. Aging 13, 25799–25845. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.203762 (2021).

Borst, J., Ahrends, T., Babala, N., Melief, C. J. M. & Kastenmuller, W. CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 635–647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-018-0044-0 (2018).

Tian, S. et al. Identification of a DNA methylation-driven genes-based prognostic model and drug targets in breast cancer: In silico screening of therapeutic compounds and in vitro characterization. Front. Immunol. 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.761326 (2021).

Yang, C. et al. Prognosis and personalized treatment prediction in TP53-mutant hepatocellular carcinoma: an in Silico strategy towards precision oncology. Brief. Bioinform. 22. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaa164 (2021).

Westin, S. N. et al. Durvalumab plus carboplatin/paclitaxel followed by maintenance durvalumab with or without Olaparib as First-Line treatment for advanced endometrial cancer: The phase III DUO-E trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 42. https://doi.org/10.1200/Jco.23.02132 (2024).

Nieuwenhuysen, E. V. et al. Durvalumab + carboplatin/paclitaxel (CP) followed by durvalumab ± olaparib as first-line treatment for newly diagnosed advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer (EC) in DUO-E: Results byBRCA1/BRCA2mutation (BRCAm) status. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 5595–5595 (2024).

Abu-Rustum, N. et al. Uterine neoplasms, version 1.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 21, 181–209. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0006 (2023).

Kang, O. J. et al. Docetaxel/Cisplatin chemotherapy followed by pelvic radiation therapy in patients with High-risk endometrial Cancer after staging surgery: A phase 2 study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. (2024).

Vennin, C. et al. Taxanes trigger cancer cell killing in vivo by inducing non-canonical T cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Cell. 41, 1170–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2023.05.009 (2023). e1112.

Necchi, A. et al. Atezolizumab in platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: Post-progression outcomes from the phase II IMvigor210 study. Ann. Oncol. 28, 3044–3050. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx518 (2017).

Tang, D., Chen, X., Kang, R. & Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell. Res. 31, 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1 (2021).

Tang, D., Chen, X. & Kroemer, G. Cuproptosis: A copper-triggered modality of mitochondrial cell death. Cell. Res. 32, 417–418. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-022-00653-7 (2022).

Robinson, N. et al. Programmed necrotic cell death of macrophages: Focus on pyroptosis, necroptosis, and parthanatos. Redox Biol. 26, 101239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2019.101239 (2019).

Tang, R. et al. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in anticancer immunity. J. Hematol. Oncol. 13, 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00946-7 (2020).

Fu, J. et al. Large-scale public data reuse to model immunotherapy response and resistance. Genome Med. 12, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-020-0721-z (2020).

Cerami, E. et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 (2012).

Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: Efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28, 1747–1756. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.239244.118 (2018).

Zeng, D. et al. Multi-omics immuno-oncology biological research to decode tumor microenvironment and signatures. Front. Immunol. 12, 687975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.687975 (2021).