Abstract

Mammographic calcifications are sentinel markers of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) with or without associated invasive breast cancer (IBC) but also occur in benign breast disease (BBD). Based on the size, shape and distribution of groups of calcifications, radiologists assess the need to perform a biopsy for pathologic diagnosis. The chemistry, mineralogy and cellular and molecular microenvironmental conditions of breast calcifications have been described in relationship to the pathology of breast lesions. However, detailed models to explain the development and expansion of calcifications are lacking, limiting our ability to define relationships of calcifications with prevalent and incident breast lesions. Here we apply a transdisciplinary geology, biology and medicine (GeoBioMed) approach targeting the internal structure, composition and occurrence of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) breast calcifications. BBD and DCIS biopsies from an extensively characterized Mayo Clinic cohort were evaluated with high-resolution microscopy and spectroscopy. Results show that calcifications are primarily composed of ACP, ACP at the threshold of transforming toward hydroxyapatite, and minor amounts of cholesterol and waxy substances. ACP nodule formation entails precipitation and coalescence of 100 nm-scale ACP spherules, 100 nm-thick alternating mineral- and organic matter-rich layering, fabric preserving (mimetic) diagenetic replacement of necrotic cells, and osteopontin stabilization within collagen containment. Based on these observations, we propose a model to explain the morphology and formation of ACP calcifications and classification linked to associated pathology. This work aims to guide development of methods to inhibit ACP calcifications within low-risk lesions that prompt unnecessary biopsies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advent of mammographic screening in 19511, both benign and malignant disorders that harbor the growth of small calcium-rich biominerals have been detected1,2,3,4,5,6. These deposits will herein be referred to as calcifications, rather than the previously used term microcalcifications, to more accurately reflect their nanometer (nm) through centimeter (cm) in vivo size range. Radiologists apply the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) classification7 to categorize the size, shape and distribution of groups of x-ray dense breast calcifications and assess the need for biopsy to obtain a pathologic diagnosis. Because mammographic groups of calcifications are often of µm- to cm-scale, many such lesions are sampled rather than removed in total. Pathology practice adds to sampling concerns because biopsy tissues are typically examined microscopically within only a few 5 μm-thick sections for diagnosis. Although pathologists report the presence of calcifications as an indication of sampling adequacy, a taxonomy for reporting their appearance is lacking, potentially limiting the value of such reporting in assuring adequate representation of the targeted lesion5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Detection of suspicious mammographic calcifications, usually embedded within ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS), leads to detection of 30–50% of invasive non-palpable breast carcinomas5,13,15,16. While DCIS is a non-obligate cancer precursor, more than 300,000 invasive cancers are diagnosed each year, most of which are associated with concurrent DCIS, while only approximately 60,000 cases of DCIS without invasion are detected annually in the United States17. Furthermore, while the identification of calcifications on mammograms detects 72–97% of clinically diagnosed benign breast disease (BBD) and DCIS cases (Supplementary Background), as well as 21% of invasive breast cancer (IBC) cases, the majority shows benign breast disease (BBD)1,2,4,5,11,13,18,19,20. This raises concern for unnecessary biopsies, the possibility of overlooking actionable disease, and the challenges of discerning calcifications associated with benign, pre-malignant and malignant lesions8. As a result, improved accuracy and precision of mammographic assessment of breast calcifications is needed1,2,5,11,13,18,21.

Breast calcifications have previously been classified as either Type I or II22,23. Type I calcifications are primarily associated with BBD, being composed of calcium oxalate dihydrate (COD; weddellite; CaC2O4 • 2(H2O)) with bipyramidal, ovoid and fusiform shapes and sometimes co-occurring with calcium phosphates1,12,22,23,24,25,26,27. Type II calcifications are more extensively studied due to their presence in DCIS and invasive breast cancer (IBC), and have been primarily interpreted to be composed of crystalline hydroxyapatite (HAP; Ca10H2(PO4)6(OH)2) with secondary amounts of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP; Ca9H2(PO4)6 • nH2O) and magnesium-rich whitlockite (Ca9Mg2(PO4)6OH)8,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. However, targeted analysis of clinically detected breast calcifications that are primarily composed of ACP in BBD and DCIS remains to be completed. This limits our understanding of how such structures develop, the morphologies and distributions that they assume, and how their radiological identification reflects the likelihood of underlying cancer, thus limiting our ability to improve management. The overlooked role of ACP calcifications in breast disease stands in contrast with the widespread recognition and extensive analysis of the fundamental role played by ACP in the biomineralization of teeth, bones, kidney stones, cardiovascular calcification, and other physiological and pathological calcifications in the human body, as well as many natural and bioengineered systems37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

GeoBioMed strategy

The goal of this study is to characterize ACP breast calcifications associated with BBD and DCIS by applying transdisciplinary concepts and techniques drawn from the fields of geology, biology and medicine via an approach called GeoBioMed43,44,45 and use these data to propose a model to describe their development and evolution. Initially developed to better understand kidney stone and aortic valve calcification, GeoBioMed analyses have demonstrated that human body soft tissue biomineralization results from natural processes that have governed billions of years of biomineralization in a wide variety of natural Earth environments43,44,45. Integrated correlative microscopy and spectroscopy completed in the present study advance our understanding of ACP calcification within BBD and DCIS across 10 to 100 nm- through 10 cm-diameter length scales. Analyses include micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT), Raman and energy dispersive x-ray (EDAX) spectroscopy, and environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM), as well as bright field (BF), circular polarization (CPOL), transmitted light photomultiplier tube (TPMT), super resolution autofluorescence (SRAF) and super resolution induced fluorescence microscopy. Internal controls are provided by the surrounding unaltered breast tissues in non-calcified portions of each histology section. These analyses and interpretations also incorporate previously rigorously established mechanistic understandings of both physiological and pathological calcification3,4,12,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,46.

Results in the present study provide insights on the causative mechanisms of ACP biomineralization (diagenetic phase transitions43,44) and ACP formational history (paragenesis43,44) that underly some forms of breast calcification. The term ACP is applied here to collectively refer to all precursor transient non-birefringent amorphous phases of calcium phosphate, non-birefringent ACP itself, and non-birefringent to very low birefringence ACP at the threshold of low order transformations toward HAP that can exhibit early stage rudimentary geometric (euhedral) forms43,44. Furthermore, a comparative baseline for confirming the presence of ACP breast calcifications in histologic sections is provided by an extensive literature of biomedical engineering and natural sciences research12,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,40,42,43,44,46,47,48.

Breast anatomy

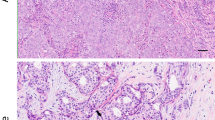

The mature human female breast is anatomically composed of several lactiferous ducts that drain from mammary lobes to the nipple. Typically, 15 to 20 of these radial lobe and duct systems terminate in 20 to 40 lobules that potentially can produce milk (Fig. 1a, b, c, e). Each lobule, its terminal duct and the immediately surrounding stromal adipose and connective tissues, are combined into a functional group called a terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU), which is where most disease processes of the breast arise (Figs. 1b; Supplementary Background)25,49,50,51. Each lobule is composed of a variable number of small, rounded milk forming glandular structures called acini (exocrine glands) (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 2) that are lined by layers of luminal and myoepithelial cells that facilitate milk secretion into ducts by contracting with infant suckling49,50,51,52. Acini are also intimately associated with an intricate network of other non-epithelial immune cell types53. Epithelial and luminal cells with apocrine metaplasia cells are commonly identified in BBD, especially in the lining of cysts (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5), which is one of the most common expressions of BBD54 (Fig. 1e, f). Apocrine cells are frequent in benign breast cysts and in dilated spaces showing columnar cell change55. Apical surfaces of cells in these contexts may give rise to spherical cytoplasmic buds that are associated with intraluminal calcifications54 (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The BBD and DCIS biopsies analyzed in the present study were excised from breast lobes and contain multiple TDLUs. The non-birefringent calcifications deposited within ducts containing necrotic cells and comedo necrosis and exhibiting collagen containment (Fig. 1g). Compared microscopic images, a mammographic image is also presented for comparison of fine linear and pleomorphic calcifications (Fig. 1h) associated with DCIS in segmental distribution in the superior breast (image by permission Jatoi et al. 2023).

Anatomical illustrations, microscopy imaging and a mammogram projection showing calcifications associated with the progressive development of BBD and DCIS in the human female breast. Illustrations (a, b, c, e and f) of breast anatomy by permission from Terese Winslow LLC. (d) BF microscopy image of a dilated lumen within BBD biopsy MCT006 showing non-birefringent SN1 calcifications composed of cores and concentrically layered cortices. (e and f) 3D illustrations of lactiferous duct showing normal epithelial and myoepithelial cells and the basement membrane (e) and a DCIS duct with abnormal cells, necrotic cells and comedo necrosis (f). (g) BF microscopy image from DCIS biopsy MCT002 of non-birefringent SEN calcifications deposited within ducts containing necrotic cells and comedo necrosis and exhibiting collagen containment. DCIS ACP SEN calcifications were crushed, fractured and partially removed during sectioning. (h) Mammographic image of fine linear and pleomorphic calcifications associated with DCIS in segmental distribution in the superior breast (image by permission Jatoi et al. 2023). ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SN1 = ACP spheroidal nodules associated with BBD. SEN = ACP semi-ellipsoidal nodules associated with DCIS. BBD = benign breast disease. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ. BF = bright field. HS = histology section. H&E = hematoxylin and eosin. TDLU = terminal duct lobular unit. 3D = three-dimensional.

Materials and methods

Detailed methods are presented in the online Supplementary Extended Methods.

Biopsies and Micro-CT scans

This research involving human breast biopsies was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB 75-87). These analyses include 8 participants in a comprehensive longitudinal Mayo Clinic BBD cohort (Supplementary Table 1), which enrolled 18,704 women at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, from 1967 to 2013, who were followed for a median of 15.8 years during their ensuing development of incident IBC55,56,57,58. The clinical data, mammograms and biopsies of participants were reviewed in detail, with identification of breast cancer at least six months following enrollment in 9.9% of the women55,56,57,58. Participants underwent screening with screen-film mammography used to guide surgical biopsies and reveal the presence of BBD, DCIS and/or IBC for the purposes of the present study. A stratified cohort of 156 BBD, DCIS and IBC surgical biopsies, each approximately 10 mm in diameter and collected from 1994 to 2007, were prepared as formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks55,56,57,58. All 156 FFPE blocks were subjected to Micro-CT scanning at Mayo Clinic Rochester at a resolution of 10 μm on a Bruker SkyScan 1276 set to confirm the presence, morphology and distribution of calcifications. Results confirmed that 100% of the 156 biopsies contained calcifications. From this cohort, eight biopsies were selected that exhibited high extents of calcification to increase the likelihood of sampling calcifications within 2D histological sections (three sections from each biopsy block, 24 sections in total). Analysis of the Micro-CT data indicated that the calcifications present in the 8 biopsies chosen for analysis were comparable in morphology (measured by calcification volume and structure model index21) to those observed throughout the entire stratified cohort of 156 biopsies.

Histological sections, stains, and Immunofluorescence labels

A total of three serial histologic sections, each 5–10 μm thick, were made from the eight biopsy FFPE blocks at the Research Histology Laboratory at Mayo Clinic Rochester. Sections were dewaxed and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series. Additional sections were cut directly adjacent to the histological sections were use in spectroscopic analyses. Calcification sites were identified and marked in the adjacent histological sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) by a study pathologist (MES). This further characterized the size, shape, 3D distribution and spatial orientation of calcifications in each biopsy and permitted calcifications to be spatially correlated between the Micro-CT scans and histology sections. One sequential suite of histology sections remained unstained, while a second suite of complimentary sections were also prepared. Some unstained sections were mounted in ultrapure water for Raman spectroscopy and imaging under environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) as described previously43,44,45. Another subset of the human breast biopsy unstained histological sections was probed with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole stain (DAPI) for DNA and against human osteopontin (OPN) protein (CoraLite Plus 647 conjugated Osteopontin Rabbit polyclonal antibody (CL647-22952, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL).

High-resolution multimodal microscopy

Stained and unstained histology sections were analyzed using multiple optical modalities43,44,45 including bright field (BF), transmission photon multiplying tube (TPMT), circular polarization (CPOL), super resolution autofluorescence (SRAF) and super resolution immunofluorescence (SRIF) microscopy. As described previously44these analyses were completed on a custom built Carl Zeiss LSM 980 Spectral NLO Airyscan II Super resolution system (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) and energy dispersive x-ray analysis (EDAX)

The ESEM of dewaxed histological sections adjacent to the H&E stained sections were critical point dried using hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS), sputter coated with a gold-palladium (Au/Pd) target (Denton DESK II TSC, Moorstown, NJ), imaged under vacuum in a FEI Quanta FEG 450 FESEM (Hillsboro, OR) using multiple magnifications. As described previously43,44,45the ESEM system parameters were optimized across the samples to accommodate the ~ 10 mm working distance, 20 kV beam (4.0 nm spot size) and a pixel dwell time of 300 ns. Elemental maps as well as EDAX spot analyses (n = 12), obtained at multiple locations across the biopsy histology sections as identified by H&E staining, targeted calcium (Ca), phosphate (P), magnesium (Mg) and other elements that are indicative of ACP calcification and/or can be either substituted within ACP or coating ACP43,44,45.

Raman spectroscopy

Breast calcification mineralogy was further determined with a WiTec Alpha300 RSA Raman imaging microscope system (WiTec, Nashville, TN) with a 532 nm-wavelength laser. As described previously44the system includes a Zeiss microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a 100 × air objective (EC Epiplan-Neofluar 100x/0.9 NA) capable of providing submicron spatial resolution was used to record Raman spectra and H&E analysis. Adjacent 5 μm-thick histology sections of the tissue biopsies were mounted with ultrapure water and used for Raman analysis. Typical Raman spectra were collected using a 5–10 mW laser power with exposure time of 1s and 10 accumulations. An optical fiber providing an effective pinhole diameter of 50 μm was used to send the optical signal to a WiTec UHTS400 spectrometer and WiTec Peltier cooled CCD camera (Newton, Andor). This analysis exhibited all expected phosphate (PO4–3; Td point group) Raman bands: symmetric stretch (v1) at 961 cm− 1, bending (v2) at 431 & 454 cm− 1, and bending (V4) at 581, 592 & 611 cm− 1 along with the corresponding broad Raman features associated with the amorphous phase as shown in Fig. 3i. Characteristic Raman bands corresponding to waxy substances are observed at 1063 (C-C stretch), 1134 (C-C stretch), 1296 (CH2 bend), and 1419 (CH2 bend), 1441 cm− 1 (CH2 bend). Corresponding C-H stretch modes are seen in the 2800–3010 cm− 1 range59,60,61.

Image adjustments, analysis, and presentation

Multimodal image processing and analyses were performed in the native Carl Zeiss Zen (version 3.5) program used to acquire the images in the same Zeiss LSM 980 microscope system computer. As described previously44a gamma of 0.45 or 0.75 was used when needed under a spline mode if deemed necessary to enhance the image fidelity for clearer observation and image interpretation. Image enhancements were made in the three-dimensional (3D) rendering programs Imaris, CanvasXDraw, Adobe Photoshop, Microsoft PowerPoint, while the final images were cropped, sized and assembled into figures.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This basic medical research study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota (IRB 75–87). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota obtained informed consent from all adult patients who participated in the cohort study.

= analysis completed.

= analysis completed.  = detected. Bd = below detection. Na = not applicable. * = Zeiss 2015 Michel-Lévy interference colour chart.

= detected. Bd = below detection. Na = not applicable. * = Zeiss 2015 Michel-Lévy interference colour chart.Results

Types of ACP calcification associated with BBD and DCIS

Spatially correlated multimodal microscopy and spectroscopy completed in the present study (Table 1) suggests five types of calcification nodules are present in the BBD and DCIS biopsies.

Their mineralogy, size, shape, internal structure, occurrence, and osteopontin (OPN), cholesterol and waxy substances associations are summarized in Table 2. These calcifications form simultaneously in multiple locations and accrete and transform with time, dependent upon the physical, chemical, and biological breast microenvironmental conditions in which they are deposited. Characterizations of each of the five nodule types (Table 2) are synthesized to infer the diagenetic phase transitions (Fig. 2a) and paragenesis (Fig. 2b, c) responsible for breast calcification. The five types of calcification nodules (Table 2) include: (1) SN1: ACP spheroidal nodules associated with BBD that are ≤ 50 μm in diameter and composed of separate smaller nodules with cores and thin concentrically layered outer coatings (cortices) that coalesce to form the overall larger nodule (Figs. 2 and 3a and b; Supplementary Figs. 3–7; Supplementary Movie 1); (2) SN2: ACP spheroidal nodules associated with DCIS that are ≤ 50 μm in diameter and exhibit cores composed of smaller nodules with their own cores and coalescing cortices, which often exhibit rudimentary geometric (euhedral) forms and are encrusted by thick outermost concentrically layered cortices (Figs. 2, 3c, d and 4; Supplementary Figs. 8–12); (3) SN3: ACP spheroidal nodules associated with DCIS that are ≤ 50 μm in diameter and composed of structureless ACP deposits (Figs. 2, 3c, d and 4a; Supplementary Figs. 8–12); (4) SN4: ACP spheroidal nodules associated with DCIS that are ≤ 100 μm in diameter, exhibit euhedral forms69 similar to those observed in kidney stones and natural hot spring travertine43experience radial fracturing during sectioning previously described as psammomas29 and are composed of Ångstrom-scale fabric preserving ACP replacement of the necrotic cells (mimetic replacement43) and fabric destructive replacement of comedo necrosis (Figs. 3e and f and 4a; Supplementary Figs. 8–12; Supplementary Movie 2); and (5) SEN: ACP semi-ellipsoidal nodules associated with DCIS that are ≤ 500 μm in diameter and also form as the result of mimetic replacement of necrotic cells and recrystallization of comedo necrosis (Figs. 2, 3g, h and 4b; Supplementary Figs. 8–12; Supplementary Movie 3). It is important to note that SN1 in BBD are similar in size and internal structure to the cores of SN2 in DCIS (Table 2). This implies that SN1 may have originally formed under ductal BBD conditions and then later served as a nucleus that was encrusted by ACP cortices to form SN2 under DCIS conditions. In contrast, SN2, SN3, SN4 and SEN exhibit distinctly varied sizes and internal structures from each other, implying they may have formed under different DCIS conditions. However, while confirmation of these paragenetic hypotheses (Fig. 2) is beyond the scope of the present study, the proposed classification scheme (Table 2) provides a roadmap for future controlled experimental studies (described below) that will test whether SN1-4 and SEN formed from a continuum of interrelated diagenetic phase transitions, or from separate BBD and DCIS processes.

Diagenetic phase transitions and paragenesis of SN1-4 and SEN calcifications associated with BBD and DCIS. (a) Diagenetic phase transitions and relative changes in ΔG of ACP, cholesterol and waxy substances. Ca/P atomic ratio analyses of the SN1-4 and SEN calcifications were collected using EDAX and compared with previously established standards for ACP36,37,44,48,70,71,72,73,74,75. Graph illustrates: (1) direct precipitation of ACP, cholesterol and waxy substances (WS) from saturated breast solutions (dashed black lines); and (2) non-classical (kinetic) step wise transformation from ACP spherule precipitation and coalescence to form SN1-4 and SEN calcifications (solid red line). Increased concentrations of OPN, decreased concentrations of ALP29 and collagen containment combine to slow the precipitation of ACP and its transformation toward HAP29,44,76,77. (b and c) Sequential and simultaneous developmental pathways (paragenetic sequence) of the precipitation of ACP, cholesterol and WS associated with BBD (b) and DCIS (c). BBD = benign breast disease. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SN = spheroidal nodules. SEN = semi-ellipsoidal nodules. ΔG = Gibbs free energy. TDLU = terminal ductal lobular unit. WS = waxy substances. Ca/P = calcium/phosphate. OPN = osteopontin. ALP = alkaline phosphatase. EDAX = energy-dispersive x-ray analysis. HAP = hydroxyapatite.

Microscopy and Raman spectroscopy analyses of calcifications associated with BBD and DCIS. (a and b) Paired TPMT and CPOL microscopy images of SN1 calcifications in biopsy MCT006. (c and d) Paired TPMT and CPOL microscopy images of SN2 and SN3 calcifications in BBD biopsy MCT009. (e and f) Paired BF and CPOL microscopy images of SN4 calcifications in DCIS biopsy MCT009. DCIS ACP SN deposits are commonly crushed during section preparation to form these types of rosettes that have previously been called psammomas; Scimeca et al. 2014). (g and h) Paired BF and CPOL microscopy images of SEN calcifications in DCIS biopsy MCT002. SEN deposits were crushed, fractured and partially removed during sectioning. (i) Representative 300–1900 cm− 1 Raman spectrum from a total of 50 Raman spot analyses within SN1-4 and SEN calcifications (including those shown in a-h), with expanded spectral regions shown at 380–640 and 925–985 cm− 1. Example Raman spot analysis locations are shown with white dots in TPMT and BF images a, c, e, and g. Peak fitting analyses indicate that both SN1-4 and SEN calcifications are composed of ACP (red and blue peak areas correspond to Raman bands for ACP and ACP transforming toward HAP, respectively). See experimental section for details on how peak fitting analyses performed from the raw data62. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. HAP = hydroxyapatite. SN = spheroidal nodules. SEN = semi-ellipsoidal nodules. BBD = benign breast disease. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ. TPMT = transmitted light photomultiplier tube. CPOL = circular polarization. BF = bright field. HS = histology section. H&E = hematoxylin and eosin.

Example ESEM and EDAX elemental analyses of SN2, SN4 and SEN calcifications associated with DCIS. Calcifications are commonly crushed and fractured during sectioning, which creates the SN4 rosette morphology (a) and partially removes SEN deposits during sectioning (b). White dots indicate areas of EDAX spot spectral analyses. (a) ESEM image of SN2 and SN4 calcifications in DCIS biopsy MCT002. (b) ESEM image of DCIS biopsy MCT009 containing SEN calcifications. (c – f) Four representative EDAX spot analysis spectra (n = 50) exhibit peaks dominated by calcium (Ca) and phosphate (P), with trace amounts of magnesium (Mg) and sodium (Na). These EDAX spot analyses, coupled with Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 3g), indicate that SN2-4 and SEN calcifications contain a Ca/P atomic percent of 1.57–2.54 (Fig. 2a), which in combination with their non-birefringence (c – f) is further evidence that the SN1-4 and SEN calcifications are composed of ACP37 and not crystalline HAP. ESEM = environmental scanning electron microscopy. EDAX = energy-dispersive X-ray. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SN = spheroidal nodules. SEN = semi-ellipsoidal nodules. BBD = benign breast disease. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ. Ca/P = calcium/phosphate.

Microscopy and x-ray imaging of BBD SN1 and DCIS SEN calcifications associated with BBD and DCIS. (a) BF microscopy image of a histology section from BBD biopsy MCT006 exhibiting cysts and ACP SN. (b - d) 3D surface rendered Micro-CT scan lateral view of the paraffin embedded block from which the histology section in a was prepared. Volume rendered raw Micro-CT data (b), 3D surface-rendered Micro-CT data with color coded sphericity analyses (c) and an overlay of image b on image c (d). (e and f) Micro-CT 3D surface rendered image enlargements of c with sphericity analyses. (g) BF microscopy image of a histology section from DCIS biopsy MCT009 exhibiting ACP SEN within ducts. (h - j) 3D surface-rendered Micro-CT scan lateral view of the paraffin embedded block from which the histology section in g was prepared. Volume rendered raw Micro-CT data (h), 3D surface rendered Micro-CT data with sphericity analyses (i) and an overlay of image h on image i (j). (k and l) Micro-CT 3D surface-rendered image enlargements of i with sphericity analyses. While variable, the largest ACP SN associated with BBD are significantly smaller than the ACP SN and ACP SEN deposits in DCIS. Micro-CT = micro-computed tomography. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward HAP. HAP = hydroxyapatite. SN = spheroidal nodules. SEN = semi-ellipsoidal nodules. BBD = benign breast disease. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ. HS = histology section. 3D = three-dimensional.

Microscopy and spectroscopy of SN1 calcifications, cholesterol and waxy substances (WS) associated with BBD. (a - h) Paired TPMT, CPOL, SRAF and SRIF imaging of BBD biopsy MCT006, exhibiting highly birefringent WS and euhedral cholesterol precipitated on the inner walls of BBD acini. (i) A representative 300–3500 cm− 1 Raman spectrum from Raman spot analyses (n = 50) within BBD (a - h), with expanded spectral regions for WS at 800–1500 and 2700–3000 cm− 1. See experimental section for details on how peak fitting analyses were performed63,64,65,66,67,68. Euhedral morphology (g, h) indicates cholesterol composition, which has been confirmed with Raman analyses in previous studies44. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SN = spheroidal nodules. BBD = benign breast disease. TPMT = transmitted light photomultiplier tube. CPOL = circular polarization. SRAF = super resolution autofluorescence. SRIF = super resolution induced fluorescence.WS = waxy substances. HS = histology section. OPN = osteopontin.

Spatially correlated CPOL and SRAF microscopy imaging of SN1, 2 and 4 calcifications associated with BBD and DCIS. Nanolayered cortices at all scales within calcifications are composed of 100’s nm- to 1 μm-scale non-birefringent ACP spherules that have coalesced. (a and b) SN1 calcifications in BBD biopsy MCT006. Individual small SN1 deposits is composed of an inner core with a thin outer concentrically nanolayered cortex. These cortices coalesce to form the larger SN1 calcifications. (b and c) SN2 calcifications in DCIS biopsy MCT002. Small irregular intergrown nodules forming the cores, which have been encrusted by a cortex of high frequency concentric nano layering. (e and f) SN4 calcification in DCIS biopsy MCT002 that exhibits radial fracturing caused crushing during sectioning to form a rosette morphology29. The whole SN4 calcification is composed of ACP fabric preserving (mimetic) replacement of necrotic cells and comedo necrosis. TPMT = transmitted light photomultiplier tube. CPOL = circular polarization. SRAF = super resolution autofluorescence. ESEM = environmental scanning electron microscopy. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SN = spheroidal nodules. HS = histology section. H&E = hematoxylin and eosin. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ.

Microscopy of SN3 calcifications. Spatially correlated TPMT, CPOL, SRAF and SRIF imaging of SN3 calcifications in DCIS biopsies MCT002 (a and i) and MCT009 (j and l), which indicate that SN3 calcifications formed in contact with necrotic cells (a – l). White boxes in a, b and c indicate areas of SN3 enlargements in d – f and g – i, respectively. OPN forms coatings and is entombed within SN3 deposits (c, f, i, l). SN3 calcifications were crushed, fractured and partially removed during sectioning (g – i). ACP transformation toward HAP is exhibited by euhedral forms (f, g – i). TPMT = transmitted light photomultiplier tube. CPOL = circular polarization. SRAF = super resolution autofluorescence. SRIF = super resolution induced fluorescence. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SN = spheroidal nodules. HAP = hydroxyapatite. BBD = benign breast disease. BF = bright field. HS = histology section. WS = waxy substances. OPN = osteopontin.

Microscopy of SEN calcifications within ducts surrounded by collagen containment and containing necrotic cells and comedo necrosis associated with DCIS. Spatially correlated TPMT, CPOL, SRAF and SRIF imaging of DCIS biopsy MCT002. White boxes shown in a, b and c indicate areas of enlargements in d - l. OPN coats the surface of, and is entombed within, SEN calcifications (f, i, l). OPN is in lower concentrations (dim SRIF) when formed in association with necrotic cells (g – i) and higher concentrations (bright SRIF) when formed in association with comedo necrosis (j – l). SEN deposits were crushed, fractured and partially removed during sectioning (a – f). ACP transformation within SEN calcifications is indicated by euhedral forms (d - f). Acicular and shapeless cholesterol exhibits bright CPOL birefringence in necrotic cells (h) and comedo necrosis (k). DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ. ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SEN = semi-ellipsoidal nodules. TPMT = transmitted light photomultiplier tube. CPOL = circular polarization. SRAF = super resolution autofluorescence. SRIF = super resolution induced fluorescence. HS = histology section. OPN = osteopontin. H&E = hematoxylin and eosin.

Microscopy indicates that ACP spherules coalescence drives SEN calcifications formation associated with DCIS. Spatially correlated TPMT, CPOL and SRAF microscopy imaging of SEN calcifications in DCIS biopsy MCT002. (a and b) Paired TPMT and CPOL images of SEN calcification formed inside a duct surrounded and contained by collagen. (c and d) Paired TPMT and CPOL enlargements of a non-birefringent SEN calcification from areas identified with a white box in a and b. Collagen is birefringent while SEN calcifications are non-birefringent to weakly birefringent. The SEN deposit was compressed and fractured during histology section preparation, forming irregular lathe shapes that exhibit euhedral forms. (e) SRAF image enlargement of area delimited by white box in d. SEN calcifications are formed because of ACP spherule coalescence that mimetically replaces and preserves the original fabric of necrotic cells and comedo necrosis. (e and f) SRAF and ESEM images from areas shown by white boxes in c and d). ACP = amorphous calcium phosphate and amorphous calcium phosphate transforming toward hydroxyapatite. SEN = semi-ellipsoidal nodules. DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ. TPMT = transmitted light photomultiplier tube. CPOL = circular polarization. SRAF = super resolution autofluorescence. HS = histology section. H&E = hematoxylin and eosin.

Raman and EDAX spectroscopy coupled with high-resolution microscopy (Table 1) indicate that all five types of calcification nodules form within microscopic structures that are pathologically BBD or DCIS and are primarily mineralogically composed of ACP (Table 2; Figs. 2 and 3; Supplementary Figs. 1–12). Evidence for this ACP mineralogical composition includes: (1) Raman spectra (n = 50) exhibiting broad amorphous ACP peaks overlapping with crystalline HAP peaks in the ranges of 400–500, 550–700 and 925–985 cm− 1 with approximately 7–10 weight% CO32− (Fig. 3i)30,33,34,35,43,44,62,78,79,80,81,82; (2) predominantly absent (extinct) birefringence to rare very low birefringence (including small amounts of 100’s nm-diameter moderately to brightly birefringent precursor cholesterol remnants entombed within the ACP) under high resolution CPOL microscopy (Fig. 3b, d, f, h; Supplementary Figs. 1, 3–10)43,44,47; and (3) EDAX spectra (n = 40) documenting Ca/P atomic % compositions of 1.57 to 2.54 that are consistent with previously reported ACP compositions (Figs. 2a and 4c-f; Supplementary Fig. 12)37,43,44,48,83. 3D rendered Micro-CT scans (Fig. 5) are used here to independently confirm (without sectioning artifacts) the size, shape and distribution of the five types of calcification nodules (Table 2) and serves to directly link the multimodal microscopy and spectroscopy (Figs. 3a-h, 4a, b, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10; Supplementary Movies 1, 3) with radiological signatures5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

In addition, all five types of calcification nodules contain minor amounts of cholesterol (Table 2; Figs. 2 and 6g, h; Supplementary Figs. 3–5, 9, 10), while only SN1 calcifications in BBD (Table 2) are associated with minor amounts of waxy substances produced by the breast (Table 2; Figs. 2 and 6a-f; Supplementary Figs. 3–5). Evidence for the presence of cholesterol and waxy substances includes: (1) highly birefringent shapeless to euhedral (platy, cleft and acicular84) cholesterol crystals or euhedral crystal molds dissolved by H&E stains in SN1 BBD (Figs. 2 and 6g, h; Supplementary Figs. 1 h, 3–5) and similarly in SN2-4 and SEN DCIS calcifications; (2) highly birefringent shapeless waxy substances (Figs. 2 and 6a-f; Supplementary Figs. 3–5)85 in SN1 BBD calcifications; and (3) Raman spectra (n = 50) exhibiting spectral regions at 800–1500 and 2700–3000 cm− 1 indicating the presence of highly birefringent waxy substances in SN1 BBD calcifications (Fig. 6a-f, i; Supplementary Figs. 3–5)63,64,65,66,67,68. In addition, concentrated coatings of OPN are observed on the surface of, and entombed within, all five types of ACP nodules (Table 2; Figs. 8c, f, i and l and 9c, f, i, l). OPN was not, however, observed to coat either cholesterol or waxy substances (Fig. 6a-f; Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

The GeoBioMed analyses conducted here indicate that there are five unique types of breast calcification nodules with distinct morphologies, internal structures and paragenesis. A better understanding of how they form may allow for determination of whether calcifications observed with mammography are “likely” versus “unlikely” to present the case for actionable lesions. Follow-up testing could then be used to develop approaches to prevent formation of “nuisance” calcifications that are not sentinels of either DCIS or invasive cancer. The following discussion hypothesizes how these novel insights on breast calcification may aid in early detection of cancer progression and their implications.

Universal nature of ACP biomineralization

ACP has been an essential and universally distributed mineralogical component of hard body parts in invertebrate and vertebrate animals and plants through geological time30,31,43,70,86,87,88,89,90,91,92. The amorphous character and dynamic energetics of ACP transformations, combined with the widespread availability of physio-chemical solution chemistries required for ACP precipitation in natural environments, explains the common role of ACP in biomineralization and its affinity for morphological flexibility, compositional variability and thermodynamic instability37,48,74. These qualities of ACP account for the spherule coalescence and high-frequency layering, extinct to very low birefringence, euhedral forms and broad range of chemical compositions that are characteristic of the SN1-4 and SEN calcifications observed in the present study (Table 2)37,48,74. Given these attributes, it is not surprising that ACP plays a fundamental role in the incipient stages of human body biomineralization processes that range from physiological (regulated) through pathological (dysregulated, dystrophic or metastatic) calcification1,3,4,12,22,23,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,43,44.

Mechanisms of ACP nodule formation in breast tissues

The fundamental building blocks of the five types of nodular calcifications (SN1-4 and SEN) are 100 nm-diameter scale ACP spherules that grow, cluster and coalesce into concentric high frequency layering. This mechanism of spherule coalescence is directly analogous to the universal non-classical biomineralization of ACP commonly observed in many different types of natural geological deposits40,43,93,94,95,96. ACP spherule coalescence is also the process underlying kidney stones formation and aortic valve calcification43,44,45. In addition, the combination of BF, TPMT, CPOL, SRAF and SRIF imaging conducted here records: (1) the emergence of ACP early euhedral forms in SN3 and SEN; and (2) the formation of high frequency, 10 to 100 nm-thick, alternating organic-matter-rich and ACP-rich concentric nanolayers in SN1, 2 and 4 nodule cortices. The entombed organic matter forming the concentric layering, derived from the host breast tissues, cells, matrix and fluids, is interpreted to be composed of biomolecules such as peptides, proteins, polysaccharides such as glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronic acid, and carbonic anhydrase, which are intimately associated with mucus production in many vertebrates and invertebrates43,44,97. These concentrically layered cortices form stratigraphic successions of biomineral growth that are continuous around individual nodules, forming age-equivalent individual layers that can be tracked between accreting nodules. Furthermore, the process of ACP mimetic replacement characteristic of SN4 and SEN calcification, is also a common product of diagenetic phase transitions in both natural and engineered environments, as well as human kidney stone and aortic valve calcification43,44,45. DCIS SEN calcifications grow outward via concentric accretion from the interior portions of each duct until contacting the inner surfaces of continuous layers of collagen surrounding the duct (collagen containment). This process is analogous to aortic valve calcification44 and likely shields ACP nodules from contact with bulk solution chemistry and water and combines with phosphorylated OPN coatings to stabilize the ACP nodules76,77,98,99. This in turn minimizes and slows eventual SEN contact with the inner wall of the duct, which although slowed by these processes will cause stretching, compression, weakening and eventual rupture of the collagen containment.

OPN influence in stabilizing calcification and promoting malignancy

Concentrated coatings of OPN have been detected in all five types of breast calcification nodules. OPN is an extracellular phosphoprotein controlled by cell physiology and inter- and intracellular matrix biochemistry to regulate a wide variety of essential physiological processes throughout the human body. These influences include driving breast cancer recurrence through promotion of tumor cell proliferation, carcinogenesis and immunomodulation100,101sympathetic nervous system control of bone mineralization102,103protection against blood-brain barrier disruption104support of innate and adaptive antiviral and antibacterial immunity105,106and stabilization of kidney stone and aortic valve calcification43,44. In its non-phosphorylated form, OPN is a catalyst of HAP precipitation, yet conversely, OPN in its phosphorylated form acts as a strong inhibitor of ACP precipitation76,77,98,99,107. The abundance of phosphorylated OPN detected in the present study serves to chemically stabilize ACP and prevent its spontaneous transition to HAP69,73,76,77,83,107,108,109. The entombment of OPN within ACP nodules as documented here (Fig. 8) may also ultimately slow cancer progression by sequestering the carcinogenic effects of OPN101. Furthermore, the eventual breach of collagen containment by SEN breast calcification may assist atypical DCIS cells in penetrating through the basement membranes, invading stromal tissues surrounding the duct, and allowing IBC to spread and metastasize via lymphatics and blood vessels8,28,51,110,111,112,113. Results from the present study also suggest that OPN stabilization and collagen containment combine in DCIS calcifications, as they do in aortic valves44to slow ACP calcification by preventing exposure to breast solution chemistries (pH, saturation state, and availability of H2O) that could quickly drive transformation of ACP to HAP and rapidly further increase the extent of calcification. However, these useful effects of OPN in stabilizing ACP biomineralization are balanced in breast microenvironments by tumor cell-derived OPN as an autocrine and paracrine catalyst of tumor recurrence100,101.

High-resolution Micro-CT in complementing radiology

The size, shape and distribution of breast calcifications are radiologically classified7 to help predict risk of underlying malignancy. Calcifications can be assessed on mammography as either “benign” requiring no dedicated follow-up, “probably benign” requiring short-interval imaging follow-up, or “suspicious” requiring biopsy, although predictive values for malignancy are generally < 30% for most groupings of calcifications recommended for biopsy1,13,26,114,115,116. The relatively recent advent of 3D Micro-CT imaging permits analysis and visualization of breast calcifications at resolutions of 100’s nm to 50 µm13,115,116,117,118,119which complement 2D and 3D mammography at lower resolutions (50–100 μm generated from lower x-ray dosages) as well as other advanced imaging techniques14,82,120,121,122,123. However, direct comparison of calcifications between Micro-CT and mammography scans can be challenging due to Micro-CT surface rendering algorithms118which for example make it difficult to distinguish coarse, coarse heterogeneous, and sometimes pleomorphic calcifications between the two techniques115,116. Similar types of rendered 3D images without surface rendering could be completed at the clinical level for shape recognition to evaluate the need for further assessment and biopsies.

Micro-CT radiology evaluations of two biopsy sections (one BBD and one DCIS) were completed here to provide basic initial radiological contextualization for microscopy and spectroscopy analyses. However, even with significantly larger sample sets than ours, discriminating between coarse, coarse heterogeneous, and pleomorphic calcification groupings in Micro-CT scans could remain challenging1,13,115,116. While these constraints prevent generalizations regarding radiological presentation of the five calcification nodules classified here, our Micro-CT data (Fig. 5) has multiple implications. Micro-CT scans of BBD SN1 calcifications are compatible with course heterogeneous groupings, which would imply an approximately 15% positive predictive value (PPV) of malignancy1,13,115,116. Conversely, DCIS SN2-4 and SEN calcifications are consistent with multiple pleomorphic groupings associated with dystrophic tissues (Fig. 6x). This would imply a PPV for malignancy risk of approximately 29%2,13,115,116. Another challenge in radiology is that small breast calcifications similar to those found in DCIS may be present in BBD (i.e., a false positive)1,13,115,116. Future testing (described below) would likely lead to better discrimination of these types of small calcifications and reduce unneeded biopsies. Collectively, these types of GeoBioMed approaches would lay the groundwork for future large cohort studies aimed at refining radiological PPV risk assessment for malignancy from the shape, size and distributions of breast calcifications formed under controlled experimentation.

Mineralogy and processes of calcification

Mineralogical determination of BBD and DCIS breast calcifications completed here from a small sample set differ from previous reports in two fundamental ways. The first is that neither fully crystalline HAP nor whitlockite were detected in BBD or DCIS biopsies in the present study. However, both have been reported as primary and minor mineralogical components, respectively, of Type II DCIS calcifications in previous studies28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,48. These previous reports do, however, detect minor amounts of classically defined ACP37,48 associated with DCIS28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. The second difference is that no evidence was collected in the present study to indicate the presence of crystalline COD. Yet the bipyramidal euhedral crystal morphology of COD in some breast calcifications has been observed with SEM, BF and birefringence under polarization, confirming previous interpretations that COD can play a primary role in Type I calcifications in BBD and a minor role in Type II calcifications in DCIS1,12,22,23,24,27.

Multiple factors may have combined to explain these discrepancies in breast calcification mineralogical identifications between the present and previous studies. Previous studies have used different yet al.so rigorous suites of analyses to identify crystalline HAP and COD8,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Therefore, the lack of COD detection in the present study most likely results from the small biopsy sample cohort size herein. Another possibility is the inherent heterogeneity of in vivo distributions of calcifications within the breast, which is responsible for presence-absence disparities in both cellular and calcification components when comparing between individual biopsies from the same and different patients13. In addition, routine staining protocols used in previous studies may have affected the preservation potential of calcification mineralogy in histology sections, which is a previously recognized subject of ongoing debate1,13,24. Yet despite these possible factors, the mechanisms of ACP breast calcification reported here can be directly integrated with previous reports since non-classical ACP mineralization is a direct precursor to both HAP and COD mineralization36,37,43,44,48,71,72,74,75,109,124. In addition, the perivascular, periductal, peri-glandular and stromal localizations of waxy substances observed here in BBD biopsies have been previously described as homogenous “waxy appearing” eosinophilic amyloid deposits125. These waxy amyloid substances are implicated primarily as an inflammatory disorder expressed exclusively in BBD glands and often present as fibroadenomatous change associated with fat necrosis with no accompanying evidence of malignancy125.

Implications for translational breast disease medicine

The mechanisms and processes potentially controlling breast calcification identified in the present and previous studies8,22,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36are dominated by kinetic biological influences that prevent consistently reliable thermodynamic predictions. Therefore, future systematically controlled testing will be required to understand, predict and potentially prevent breast calcification using batch30,31,36 and microfluidic45,126,127 experimentation. Experimentation on how to slow, prevent, disrupt and/or dissolve ACP calcification43,44,45 in these experiments would target initial formation of ACP spherules, their coalescence and transformation into high-frequency layering. This testing could include controlled manipulation of gradients and fluctuations influencing ACP deposition43,44,76,77. Furthermore, these experiments could also include testing metabolic and surface enzymatic or inhibitory influences on ACP deposition of the in vivo breast microbiome128,129.

Especially useful in determining these underlying mechanisms would be high resolution spatial and temporal real-time and time lapse microfluidic tracking of the formation of ACP, cholesterol and waxy substances in the presence of living breast cells embedded in hydrogels127. Experimental designs could include testing changes in diet and hydration, plant extracts and other natural products43,130,131,132and a wide variety of pharmaceuticals. The effect of changing concentrations and combinations of previously identified protein inhibitors and promotors of ACP could also be evaluated133,134. Additional strategic targets include molecular suppressor and progression influences135reactive oxygen species influence136microbiome control137,138 and effects of surrounding stromal tissues8,139. Previous studies have documented multiple other developmental and reproductive associations that influence groupings of breast calcifications that could be factored into the experimentation and the choice of biopsy cohorts for analysis140. Recent advances in spatial transcriptomics141,142 would allow expression of the three splice variants (OPN-a, b, c) of the metastasis gene responsible for OPN production in tumors143,144 to be tracked during ACP formation. This would serve as an indicator of the balance between OPN stabilization and inhibition of ACP transformation, OPN enhancement of cancer progression, and targeted suppression/downregulation therapy of OPN expression in cancer cells thereby slowing cancer cell progression and migration. Taken together, these experimental approaches may serve to both reduce formation of calcifications in benign lesions and improve radiologic characterization to reduce unneeded biopsies. Furthermore, when groups of mammographic calcifications are sampled by biopsy, these experiments would enhance assessment of the need for repeat biopsy within the setting of an initial benign impression on microscopic examination of biopsy sections.

Data availability

Availability of Data and MaterialsThe datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the UIUC Box repository https://uofi.box.com/s/yl0q6k2m47cdoj2cgf8jnxkny6ceh2dm.

References

Tse, G. M., Tan, P. H., Pang, A. L. M., Tang, A. P. Y. & Cheung, H. S. Calcification in breast lesions: pathologists’ perspective. J. Clin. Pathol. 61, 145–151 (2008).

Tse, G. M., Tan, P. H., Cheung, H. S., Chu, W. C. W. & Lam, W. W. M. Intermediate to highly suspicious calcification in breast lesions: a radio-pathologic correlation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 110, 1–7 (2008).

Cox, R. F. & Morgan, M. P. Microcalcifications in breast cancer: lessons from physiological mineralization. Bone 53, 437–450 (2013).

O’Grady, S. & Morgan, M. P. Microcalcifications in breast cancer: from pathophysiology to diagnosis and prognosis. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Reviews Cancer. 1869, 310–320 (2018).

Tot, T., Gere, M., Hofmeyer, S., Bauer, A. & Pellas, U. The clinical value of detecting microcalcifications on a mammogram. Sem. Cancer Biol. 72, 165–174 (2021).

Nicosia, L. et al. History of mammography: analysis of breast imaging diagnostic achievements over the last century. Healthc. (Basel). 11, 1596 (2023).

Shiwlani, A., Ahmad, A., Umar, M., Dharejo, N. & Tahir, A. BI-RADS Category Prediction from Mammography Images and Mammography Radiology Reports Using Deep Learning: A Systematic Review. 3, (2024).

Jatoi, I., Shaaban, A. M., Jou, E. & Benson, J. R. The biology and management of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpsurg.2023.101361

De Paredes, E. S. & De Paredes, E. S. Atlas of Mammography (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007).

Wilkinson, L., Thomas, V. & Sharma, N. Microcalcification on mammography: approaches to interpretation and biopsy. Br J. Radiol 90, 20160594 .

Hanna, W. M. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: an update for the pathologist in the era of individualized risk assessment and tailored therapies. Mod. Pathol. 32, 896–915 (2019).

Haghayeghi, K., Najibi, M., Wang, H., Donegan, L. & Wang, Y. Clinicopathologic update of calcium oxalate in breast: A 15-year retrospective review. Breast J. 26, 1736–1741 (2020).

Logullo, A. F., Prigenzi, K. C. K., Nimir, C. C. B. A., Franco, A. F. V. & Campos, M. S. D. A. Breast microcalcifications: past, present and future (Review). Mol. Clin. Oncol. 16, 81 (2022).

Mathieu, E. et al. Health benefits and harms of mammography screening in older women (75 + years)—a systematic review. Br. J. Cancer. 130, 275–296 (2024).

Gershon-Cohen, J. Atlas of Mammography (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1970). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-85678-5

Rominger, M., Wisgickl, C. & Timmesfeld, N. Breast microcalcifications as type descriptors to stratify risk of malignancy: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis of 10665 cases with special focus on round/punctate microcalcifications. RöFo - Fortschr. Auf Dem Gebiet Der Röntgenstrahlen Und Der Bildgebenden Verfahren. 184, 1144–1152 (2012).

World Health Organization (WHO). https://www.who.int

Kim, S., Tran, T. X. M., Song, H. & Park, B. Microcalcifications, mammographic breast density, and risk of breast cancer: a cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 24, 96 (2022).

Venkatesan, A., Chu, P., Kerlikowske, K., Sickles, E. A. & Smith-Bindman, R. Positive predictive value of specific mammographic findings according to reader and patient variables. Radiology 250, 648–657 (2009).

Farshid, G., Sullivan, T., Downey, P., Gill, P. G. & Pieterse, S. Independent predictors of breast malignancy in screen-detected microcalcifications: biopsy results in 2545 cases. Br. J. Cancer. 105, 1669–1675 (2011).

Schrup, S. et al. Microcalcifications in benign breast biopsies: association with lesion type and risk. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 208, 543–551 (2024).

Frappart, L. et al. Structure and composition of microcalcifications in benign and malignant lesions of the breast: study by light microscopy, transmission and scanning electron microscopy, microprobe analysis, and X-ray diffraction. Hum. Pathol. 15, 880–889 (1984).

Frappart, L. et al. Different types of microcalcifications observed in breast pathology. Vichows Archiv Pathol. Anat. 410, 179–187 (1987).

Tornos, C., Silva, E., el-naggar, A. & Pritzker, K. Calcium oxalate crystals in breast biopsies the missing microcalcifications. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 14, 961–968 (1990).

Tabar, L. et al. Mammographic tumor features can predict long-term outcomes reliably in women with 1–14-mm invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer 101, 1745–1759 (2004).

Choi, W. J. et al. Calcifications with suspicious morphology at mammography: should they all be considered with the same clinical significance? Eur. Radiol. 31, 2529–2538 (2021).

Chinyama, C. N. Calcification in benign lesions. in Benign Breast Diseases: Radiology - Pathology - Risk Assessment (ed Chinyama, C. N.) 229–240 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41065-9_13. (2014).

Cichon, M. A., Degnim, A. C., Visscher, D. W. & Radisky, D. C. Microenvironmental influences that drive progression from benign breast disease to invasive breast Cancer. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 15, 389–397 (2010).

Scimeca, M. et al. Microcalcifications in breast cancer: an active phenomenon mediated by epithelial cells with mesenchymal characteristics. BMC Cancer. 14, 286 (2014).

Vidavsky, N. et al. Studying biomineralization pathways in a 3D culture model of breast cancer microcalcifications. Biomaterials 179, 71–82 (2018).

Vidavsky, N., Kunitake, J. A. M. R. & Estroff, L. A. Multiple pathways for pathological calcification in the human body. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001271 (2021).

Kunitake, J. A. M. R. et al. Correlative imaging reveals physiochemical heterogeneity of microcalcifications in human breast carcinomas. J. Struct. Biol. 202, 25–34 (2018).

Kunitake, J. A. M. R. et al. Biomineralogical signatures of breast microcalcifications. Sci. Adv. 9, eade3152 (2023).

Gosling, S. et al. Calcification microstructure reflects breast tissue microenvironment. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 24, 333–342 (2019).

Gosling, S. et al. A multi-modal exploration of heterogeneous physico–chemical properties of DCIS breast microcalcifications. Analyst 147, 1641–1654 (2022).

Nahmias, Y., Yazbek Grobman, G. & Vidavsky, N. Inhibiting pathological calcium phosphate mineralization: implications for disease progression. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16, 18344–18359 (2024).

Dorozhkin, S. Calcium orthophosphates in nature, biology and medicine. Materials 2, 399–498 (2009).

Dorozhkin, S. V. Calcium orthophosphates. Biomatter 1, 121–164 (2011).

Dorozhkin, S. V. Calcium orthophosphates and human beings. Biomatter 2, 53–70 (2012).

Weiner, S. & Addadi, L. Crystallization pathways in biomineralization. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 41, 21–40 (2011).

Zhao, J., Liu, Y., Sun, W. & Yang, X. First detection, characterization, and application of amorphous calcium phosphate in dentistry. J. Dent. Sci. 7, 316–323 (2012).

Wegst, U. G. K., Bai, H., Saiz, E., Tomsia, A. P. & Ritchie, R. O. Bioinspired structural materials. NATURE MATERIALS 14, 23-36 (2015).

Sivaguru, M. et al. Human kidney stones: a natural record of universal biomineralization. Nat. Rev. Urol. 18, 404–432 (2021).

Sivaguru, M. et al. Osteopontin stabilization and collagen containment slows amorphous calcium phosphate transformation during human aortic valve leaflet calcification. Sci. Rep. 14, 12222 (2024).

Sivaguru, M. et al. Geobiology reveals how human kidney stones dissolve in vivo. Sci. Rep. 8, 13731 (2018).

He, W. et al. Formation of Bone-like nanocrystalline apatite using Self-Assembled liquid crystals. Chem. Mater. 24, 892–902 (2012).

Mahamid, J. et al. Mapping amorphous calcium phosphate transformation into crystalline mineral from the cell to the bone in zebrafish fin rays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 6316–6321 (2010).

Degli Esposti, L. & Iafisco, M. Amorphous calcium phosphate, the lack of order is an abundance of possibilities. Biomaterials Biosystems. 5, 100037 (2022).

Lopez-Garcia, M. A., Geyer, F. C., Lacroix-Triki, M., Marchió, C. & Reis-Filho, J. S. Breast cancer precursors revisited: molecular features and progression pathways. Histopathology 57, 171–192 (2010).

Biswas, S. K., Banerjee, S., Baker, G. W., Kuo, C. Y. & Chowdhury, I. The mammary gland: basic structure and molecular signaling during development. IJMS 23, 3883 (2022).

Hophan, S. L. et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ of breast: from molecular etiology to therapeutic management. Endocrinology 163, bqac027 (2022).

Tabár, L. Breast cancers originating from the terminal ductal lobular units: in situ and invasive acinar adenocarcinoma of the breast, AAB. European J. Radiology 152, (July 2022):110323

Kumar, T. et al. A spatially resolved single-cell genomic atlas of the adult human breast. Nature 620, 181–191 (2023).

Santen, R. J. & Mansel, R. Benign breast disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 275–285 (2005).

Degnim, A. C. et al. Changes in Breast Cancer Risk Associated with Benign Breast Disease from 1967 to 2013. JNCI Cancer Spectrum pkae128 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkae128

Hartmann, L. C. et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 353, 229–237 (2005).

Vierkant, R. A. et al. Mammographic breast density and risk of breast cancer in women with atypical hyperplasia: an observational cohort study from the Mayo clinic benign breast disease (BBD) cohort. BMC Cancer. 17, 84 (2017).

Sherman, M. E. et al. Benign breast disease and breast Cancer risk in the percutaneous biopsy era. JAMA Surg. 159, 193–201 (2024).

Mizushima, S. & Simanouti, T. Raman frequencies of n-Paraffin molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 71, 1320–1324 (1949).

Samuel, A. Z. et al. Determination of percent crystallinity of Side-Chain crystallized Alkylated-Dextran derivatives with Raman spectroscopy and multivariate curve resolution. Anal. Chem. 88, 4644–4650 (2016).

Samuel, A. Z. Direct Estimation of polymer crystallinity with Raman spectroscopy using ratio of scattering cross-sections estimated from variable temperature measurements. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 224, 117431 (2020).

Montes-Hernandez, G. & Renard, F. Nucleation of brushite and hydroxyapatite from amorphous calcium phosphate phases revealed by dynamic In situ Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 15302–15311 (2020).

Russell, D. W. Cholesterol biosynthesis and metabolism. Cardiovasc. Drug Ther. 6, 103–110 (1992).

Zock, P. L., de Vries, J. H. & Katan, M. B. Impact of myristic acid versus palmitic acid on serum lipid and lipoprotein levels in healthy women and men. Arterioscler. Thromb. 14, 567–575 (1994).

Nes, W. D. Biosynthesis of cholesterol and other sterols. Chem. Rev. 111, 6423–6451 (2011).

Afonso, M. S. et al. Mol. Pathways Underlying Cholesterol Homeost. Nutrients 10, 760 (2018).

Esperança, E. S., Bonatto, M. S., Costa, M. C., Meirelles, A. J. A. & Maximo, G. J. Cholesterol thermodynamic behaviour in mixtures with medium chain fatty acids and vegetable oils composed of them. Fluid. Phase. Equilibria. 557, 113432 (2022).

Ye, J. & DeBose-Boyd, R. A. Regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 3, a004754 (2011).

Broeders, W. et al. Innate immune cells in the pathophysiology of calcific aortic valve disease: lessons to be learned from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease? Basic. Res. Cardiol. 117, 28 (2022).

Cölfen, H. & Mann, S. Higher-Order organization by mesoscale Self‐Assembly and transformation of hybrid nanostructures. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 2350–2365 (2003).

Dorozhkin, S. V. & Dorozhkina, E. I. In vitro simulation of vascular calcification by the controlled crystallization of amorphous calcium phosphates onto porous cholesterol. J. Mater. Sci. 40, 6417–6422 (2005).

Gower, L. B. Biomimetic model systems for investigating the amorphous precursor pathway and its role in biomineralization. Chem. Rev. 108 https://doi.org/10.1021/cr800443h (2008).

Rodriguez, K. J., Piechura, L. M., Porras, A. M. & Masters, K. S. Manipulation of valve composition to elucidate the role of collagen in aortic valve calcification. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 14, 29 (2014).

Gelli, R., Ridi, F. & Baglioni, P. The importance of being amorphous: calcium and magnesium phosphates in the human body. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 269, 219–235 (2019).

Gower, L. & Elias, J. Colloid assembly and transformation (CAT): the relationship of PILP to biomineralization. J. Struct. Biology: X. 6, 100059 (2022).

Holt, C., Lenton, S., Nylander, T., Sørensen, E. S. & Teixeira, S. C. M. Mineralisation of soft and hard tissues and the stability of biofluids. J. Struct. Biol. 185, 383–396 (2014).

Schweikle, M. et al. Stabilisation of amorphous calcium phosphate in polyethylene glycol hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 90, 132–145 (2019).

Penel, G. et al. Infrared and Raman microspectrometry study of fluor-fluor-hydroxy and hydroxy-apatite powders.

Awonusi, A., Morris, M. D. & Tecklenburg, M. M. J. Carbonate assignment and calibration in the Raman spectrum of apatite. Calcif Tissue Int. 81, 46–52 (2007).

Stammeier, J. A., Purgstaller, B., Hippler, D., Mavromatis, V. & Dietzel, M. In-situ Raman spectroscopy of amorphous calcium phosphate to crystalline hydroxyapatite transformation. MethodsX 5, 1241–1250 (2018).

Siddiqi, S. A. & Azhar, U. Carbonate substituted hydroxyapatite. in Handbook of Ionic Substituted Hydroxyapatites 149–173Elsevier, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102834-6.00006-9

Shah, B., Fundaro, G. & Mandava, S. Breast Imaging Review (Springer New York, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1728-7

Habraken, W. J. E. M. et al. Ion-association complexes unite classical and non-classical theories for the biomimetic nucleation of calcium phosphate. Nat. Commun. 4, 1507 (2013).

Letter, H., Komforti, M., Maxwell, R. & Maimone, S. Cholesterol granuloma of the breast: A case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 18, 3009–3013 (2023).

Shi, J., Sweedman, M. C. & Shi, Y. C. Structure, birefringence and digestibility of spherulites produced from debranched waxy maize starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 183, 1486–1494 (2021).

Lowenstam, H. A. & Weiner, S. Transformation of amorphous calcium phosphate to crystalline dahllite in the radular teeth of chitons. Science 227, 51–53 (1985).

Lowenstam, H. A. & Weiner, S. On Biomineralization (Oxford University Press, 1989).

Addadi, L., Raz, S. & Weiner, S. Taking advantage of disorder: amorphous calcium carbonate and its roles in biomineralization. Adv. Mater. 15, 959–970 (2003).

Addadi, L., Vidavsky, N. & Weiner, S. Transient precursor amorphous phases in biomineralization.in the footsteps of heinz A. Lowenstam. Z. Für Kristallographie - Crystalline Mater. 227, 711–717 (2012).

Malekhosseini, M. et al. Traces of calcium oxalate biomineralization in fossil leaves from late oligocene Maar deposits from Germany. Sci. Rep. 12, 15959 (2022).

Larkin, N. R. et al. The fossil record’s oldest known calculus (an enterolith of the gastrointestinal tract), from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation (Upper Jurassic), UK. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 134, 526–532 (2023).

Pulletikurti, S., Veena, K. S., Yadav, M., Deniz, A. A. & Krishnamurthy, R. Experimentally modeling the emergence of prebiotically plausible phospholipid vesicles. Chem 10, 1-29 (2024).

Keith, H. D. & Padden, F. J. Jr. A phenomenological theory of spherulitic crystallization. J. Appl. Phys. 34, 2409–2421 (2004).

Weiner, S. Transient precursor strategy in mineral formation of bone. Bone 39, 431–433 (2006).

Watkins, J., Manga, M., Huber, C. & Martin, M. Diffusion-controlled spherulite growth in Obsidian inferred from H2O concentration profiles. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 157, 163–172 (2009).

Mercedes-Martín, R. et al. A depositional model for spherulitic carbonates associated with alkaline, volcanic lakes. Mar. Pet. Geol. 86, 168–191 (2017).

Verkoelen, C. F. & Verhulst, A. Proposed mechanisms in renal tubular crystal retention. Kidney Int. 72, 13–18 (2007).

Sainger, R. et al. Dephosphorylation of Circulating human osteopontin correlates with severe valvular calcification in patients with calcific aortic valve disease. Biomarkers 17, 111–118 (2012).

Gericke, A. et al. Importance of phosphorylation for osteopontin regulation of biomineralization. Calcif Tissue Int. 77, 45–54 (2005).

Gu, Y. et al. Osteopontin is a therapeutic target that drives breast cancer recurrence. Nat. Commun. 15, 9174 (2024).

Panda, V. K. et al. Osteopontin: A key multifaceted regulator in tumor progression and Immunomodulation. Biomedicines 12, 1527 (2024).

Nagao, M. et al. Sympathetic control of bone mass regulated by osteopontin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 17767–17772 (2011).

Ibsen, C. J. S., Chernyshov, D. & Birkedal, H. Apatite formation from amorphous calcium phosphate and mixed amorphous calcium phosphate/Amorphous calcium carbonate. Chem. – Eur. J. 22, 12347–12357 (2016).

Suzuki, H., Hasegawa, Y., Kanamaru, K. & Zhang, J. H. Mechanisms of Osteopontin-Induced stabilization of Blood-Brain barrier disruption after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Stroke 41, 1783–1790 (2010).

Van Der Windt, G. J. W. et al. Osteopontin impairs host defense during Pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 203, 1850–1858 (2011).

Zhao, K. et al. Intracellular osteopontin stabilizes TRAF3 to positively regulate innate antiviral response. Sci. Rep. 6, 23771 (2016).

Ibsen, C. J. S., Gebauer, D. & Birkedal, H. Osteopontin stabilizes metastable States prior to nucleation during apatite formation. Chem. Mater. 28, 8550–8555 (2016).

Chen, J. H., Simmons, C. A. & Towler, D. A. Cell–Matrix interactions in the pathobiology of calcific aortic valve disease. Circul. Res. 108, 1510–1524 (2011).

Rodriguez, D. E. et al. Multifunctional role of osteopontin in directing intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen and activation of osteoclasts. Acta Biomater. 10, 494–507 (2014).

Villanueva, H. et al. The emerging roles of steroid hormone receptors in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 23, 237–248 (2018).

Dessources, K., Sebastiao, A. P. M., Pareja, F., Weigelt, B. & Reis-Filho, J. S. How Did We Get There? The Progression from Ductal Carcinoma In Situ to Invasive Ductal Carcinoma. (2019).

Hoda, S., Brogi, E., Koener, F. & Rosen, P. Rosen’s Breast Pathology.

Wilson, G. M., Dinh, P., Pathmanathan, N. & Graham, J. D. Ductal carcinoma in situ: molecular changes accompanying disease progression. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 27, 101–131 (2022).

Bick, U. & Mammography How to interpret microcalcifications. in Diseases of the Abdomen and Pelvis 2014–2017: Diagnostic Imaging and Interventional Techniques (eds Hodler, J., von Schulthess, G. K., Kubik-Huch, R. A. & Zollikofer, C. L.) 313–318 (Springer Milan, Milano, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-88-470-5659-6_40. (2014).

Brahimetaj, R. et al. Improved automated early detection of breast cancer based on high resolution 3D micro-CT microcalcification images. BMC Cancer. 22, 162 (2022).

Brahimetaj, R., Cornelis, J. & Jansen, B. Micro-CT microcalcification analysis: A scoping review of current applications and future potential in breast Cancer research. Tomography 10, 1716–1729 (2024).

Willekens, I. et al. High-resolution 3D micro-CT imaging of breast microcalcifications: a preliminary analysis. BMC Cancer. 14, 9 (2014).

Kenkel, D. et al. A Micro CT study in patients with breast microcalcifications using a mathematical algorithm to assess 3D structure. PLoS One. 12, e0169349 (2017).

Bell, B. M. & Gossweiler, M. Benign Breast Calcifications. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2025).

Rauch, G. M. et al. Microcalcifications in 1657 patients with pure ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: correlation with clinical, histopathologic, biologic features, and local recurrence. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 23, 482–489 (2016).

Colan-Georges, A. Atlas of Full Breast Ultrasonography (Springer International Publishing, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31418-1

Nori, J., Kaur, M., Kornecki, A., Meenal, J. D. & Yaffe, M. J. Atlas of Contrast-Enhanced Mammography (Springer International Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56263-2

Rangarajan, K. et al. Ultra-high resolution, multi-scale, context-aware approach for detection of small cancers on mammography. Sci. Rep. 12, 11622 (2022).

Cölfen, H. & Mann, S. Higher-Order organization by mesoscale Self-Assembly and transformation of hybrid nanostructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 2350–2365 (2003).

Farooq, A., Shponka, V. & Jorns, J. M. Amyloidosis of breast: an uncommon mimic of fat necrosis. Hum. Pathol. Rep. 26, 300578 (2021).

Fouke, B. W. et al. Sulfate-reducing bacteria streamers and iron sulfides abruptly occlude porosity and increase hydraulic resistance in proppant-filled shale fractures. Bulletin 106, 179–208 (2022).

Mendoza, M., Chen, M. H., Huang, P. & Mahler, G. J. Shear and endothelial induced late-stage calcific aortic valve disease-on-a-chip develops calcium phosphate mineralizations. Lab. Chip. 22, 1374–1385 (2022).

Saw, J. J. et al. In vivo entombment of Bacteria and Fungi during calcium oxalate, brushite, and Struvite urolithiasis. Kidney360 2, 298–311 (2021).

Bernardo, G. et al. The Emerging Role of the Microbiota in Breast Cancer Progression. Cells 12, 1945 (2023).

Donato, M. et al. The emerging role of nutraceuticals in cardiovascular calcification: evidence from preclinical and clinical studies. Nutrients 13, 2603 (2021).

Balandrin, M. F. Commercial utilization of Plant-Derived saponins: an overview of medicinal, pharmaceutical, and industrial applications. in Saponins Used in Traditional and Modern Medicine (eds Waller, G. R. & Yamasaki, K.) 1–14 (Springer US, Boston, MA, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1367-8_1. (1996).

Balandrin, M. F., Klocke, J. A., Wurtele, E. S. & Bollinger Wm. H. Natural plant chemicals: sources of industrial and medicinal materials. Science 228, 1154–1160 (1985).

Khan, S. R. et al. Kidney stones. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2, 1–23 (2016).

Basavaraj, D. R., Biyani, C. S., Browning, A. J. & Cartledge, J. J. The role of urinary kidney stone inhibitors and promoters in the pathogenesis of calcium containing renal stones. EAU-EBU Update Ser. 5, 126–136 (2007).

Qiu, S. et al. Spiculation Sign Recognition in a Pulmonary Nodule Based on Spiking Neural P Systems. Biomed Res Int 6619076 (2020). (2020).

Sivaguru, M. & Fouke, B. W. Renal Macrophages and Multinucleated Giant Cells: Ferrymen of the River Styx? Kidney360 3, 1616–1619 (2022).

Urbaniak, C. et al. Microbiota of human breast tissue. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3007–3014 (2014).

Hieken, T. J. et al. The Microbiome of aseptically collected human breast tissue in benign and malignant disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 30751 (2016).

Leonardi, M. C. et al. Tools to guide radiation oncologists in the management of DCIS. Healthcare 12, 795 (2024).

Azam, S. et al. Predictors of mammographic microcalcifications. Int. J. Cancer. 148, 1132–1143 (2021).

Yoosuf, N., Navarro, J. F., Salmén, F., Ståhl, P. L. & Daub, C. O. Identification and transfer of Spatial transcriptomics signatures for cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res. 22, 6 (2020).

Rossi, M. & Radisky, D. C. Multiplex digital Spatial profiling in breast Cancer research: State-of-the-Art technologies and applications across the translational science spectrum. Cancers (Basel). 16, 1615 (2024).

Patani, N., Jouhra, F., Jiang, W. & Mokbel, K. Osteopontin expression profiles predict pathological and clinical outcome in breast Cancer. ANTICANCER RESEARCH 28, 4105-4110 (2008).

Kariya, Y., Oyama, M., Kariya, Y. & Hashimoto, Y. Phosphorylated osteopontin secreted from Cancer cells induces Cancer cell motility. Biomolecules 11, 1323 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank those individuals who have donated their tissues for the advancement of education and research. We also thank C. Wallace and T. Josek with the Integrated Technologies Group at the Illinois Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology for assistance with ESEM and EDAX analyses. We also thank K. Naicker and N. Prabhu at Cytometry and Microscopy to Omics facility at the Illinois Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center for assistance with OPN immunohistochemistry and sample preparation for Raman analyses.

Funding

This research was supported by a Barbara and Ed Weil Foundation grant to B.W.F.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E.S., S.E.S. and S.M. provided access to reposited Mayo Cohort BBD-DCIS biopsy samples after careful evaluation of tissue type and clinical pathologist report and prepared labeled and unlabeled histology sections. M.S., K.W.F. and B.W.F completed multimodal GeoBioMed microscopy analysis, as well as data analysis, compilation and drafting figures. A.Z.S and R.B. provided expertise in collecting, analysis and interpreting Raman spectroscopy data of human breast tissues. M.E.S., S.E.S. and S.M. provided in-depth discussions throughout the project and thoroughly edited text and figure drafts made by M.S., K.W.F., B.W.F., S.E.S., M.E.S., S.M., A.Z.S., and R.B. provided expertise throughout the study leading up to the final submission from their respective fields of geology, biology, cytometry, multimodal microscopy, omics, breast cancer pathology, breast imaging, Raman spectroscopy of human breast tissues. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This basic medical research study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota (IRB 75–87). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota obtained informed consent from all adult patients who participated in the cohort study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information