Abstract

Bemisia tabaci is a globally recognized pest known for its invasiveness, resistance to many insecticides, and ability to transmit viral diseases in plants. While research has focused on its physiological and ecological adaptations, the role of epigenetic regulators, particularly small non-coding RNAs like miRNAs, remains largely unexplored and may be key to its resilience to stressors. So far, no reference B. tabaci miRNAs are reported. Identifying them will give valuable insights for understanding how these regulatory miRNAs influence biological functions, the mechanisms that lead to management failures and developing next-generation management strategies. To assess the novel miRNAs in B. tabaci, we thoroughly searched various public repositories, such as NCBI, ENSEMBL, and miRBase, to retrieve biological data. This study predicted 81 novel miRNAs in B. tabaci, 37 and 44 from its whole genome and transcriptome sequence data sets. We validated the principal features of these predicted miRNAs using a sensitive algorithm such as RNAfold and RNA families (Rfam). The target prediction of these miRNAs revealed that many are involved in molecular functions, such as signaling, transcriptional factor-activating kinases, and nucleotide-binding proteins. Stem-loop qPCR and small RNA sequencing of predicted miRNAs in the B. tabaci genome confirmed their presence and conservation in related species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Whiteflies are categorized into three distinct subfamilies: Aleurodicinae (130 species in 20 genera, predominantly thriving in the Caribbean and the Americas), Aleyrodinae (140 genera that flourish in warm-temperate and pantropical regions), and Udamoselinae (two South American species in Udamoselis) 1. From an economic standpoint, species such as Bemisia tabaci, Trialeurodes vaporariorum, and T. abutilonia serve as significant vectors for plant viruses, which pose a considerable threat to essential agricultural and horticultural crops 2. Among them, B. tabaci is a widely distributed pest comprising over 44 cryptic species that vary in feeding behaviors, responses to insecticides, and ability to transmit viruses 3. Being a phloem feeder, it vectored more than 400 plant viruses 4, including genera of Begomovirus, Crinivirus, Potyviridae, Torradovirus, Carlavirus, and Cytorhabdovirus 5. This cryptic species thwarts biological control efforts, which increases reliance on insecticides for B. tabaci management. However, excessive insecticide use has driven resistance development in pest populations, diminishing effectiveness and leading to control failures 6. Insecticides are also hazardous to the environment, creating pollution and unwarranted impacts on beneficial organisms and mammals 7.

The discovery of the reverse genetic mechanism, RNA interference (RNAi) 8, provided a new gateway to develop next-generational bio-pesticides exploiting genetic material. The exogenous introduction of the gene-specific construct facilitates the pest management by harnessing the natural mechanism of small interfering RNA (siRNA) 9,10,11. This approach confidently provides exceptional opportunities for residue-free pest management through targeted suppressive functions. Small RNAs have been clearly classified into three major types based on their origin, structure, biogenesis, and function. Among these, PIWI-interacting piRNAs are particularly effective in inhibiting transcripts from self-serving genomic elements such as transposons 12, genome-encoded miRNAs, which regulate various biological processes, and siRNAs, which protect the organism from viruses 13. Furthermore, insect miRNA repertoires have been predominantly delineated in species with fully sequenced genomes. These include twelve species of Drosophila, four hymenopterans (Apis mellifera, Nasonia giraulti, N. longicornis, and N. vitripennis), three mosquito species (Aedes aegypti, Anopheles gambiae, and Culex quinquefasciatus), the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum), the silkworm (Bombyx mori), the butterfly (Heliconius melpomene), the migratory locust (Locusta migratoria), and the flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum) 14.

RNAi can be accomplished through the use of both endogenous and exogenous applications of dsRNA and/or siRNA, potentially downregulating target transcripts, which positions them as a dependable next-generation strategy for pest management problems. This strategy indeed necessitates biogenesis machinery, which is found in several insect orders, including Hemiptera 15. Irrespective of their mechanism of action, most of the proteins involved in biogenesis were shared by both miRNA and siRNA, including Dicer1, Loquacious and Argonaute1 for miRNA and Dicer2, R2D2 and Argonauate2 for siRNA pathway 16,17,18,19,20. Tribolium castaneum, the flour beetle, has been used as a model organism for RNAi studies 21,22,23, in contrast to the commonly used model organism, Drosophila melanogaster. It is because T. castaneum possesses sid1 (systemic RNA interference deficient 1), which is involved in intercellular mobilization and systemic action of endogenous miRNAs 24,25. Core RNAi machinery, including sid1-like protein, is present in the whiteflies and also shows the closest homology with aphids 26. In some insects, a systemic RNAi response is possible, which means that dsRNA delivery can trigger an RNAi response throughout the entire body 27.

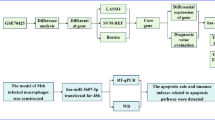

MiRBase is a recognized standard database containing validated miRNAs from prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. The database carries 48,885 miRNAs from 271 different organisms (https://www.mirbase.org, visited January 6, 2024). MiRBase does not have a reference miRNA accession for B. tabaci, and there are few previous studies on its miRNA. Several tools have been developed to predict miRNAs from transcriptomics and EST sequences, but not from whole genome sequences. This work aimed to find regulatory miRNAs for B. tabaci utilizing a bioinformatics pipeline using various genome resources such as ESTs, whole genome, and transcriptomes, and it also structurally validated the novel miRNAs (Fig. 1). The randomly selected miRNAs were validated using stem-loop real-time reverse transcription (RT) polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

Results

Mining miRNAs

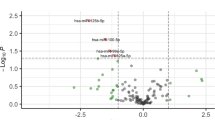

We retrieved 48,880 miRNA sequences from the miRBase repository and 7540 ESTs after clustering non-redundant sequences. The generated local EST database, utilizing pre-installed BLASTn software, blasted against miRNAs to predict expressed miRNAs; however, using an e-value of 10^(− 3) and allowing for a maximum of three mismatches yielded no hits. Subsequently, we leveraged the whole genome and transcriptome data of B. tabaci, which produced significant mapping statistics. By mapping the whole genome and transcriptome sequences for potential miRNA candidates, we identified 34 and 47 novel miRNAs, respectively, out of which 10 and 21 were specific to B. tabaci. Furthermore, 24 and 26 of these candidates matched previously described microRNA families, indicating conservation across various organisms (Figs. 2, 7). Finally, we documented the distribution of previously reported miRNAs, providing their sequence and mapping statistics in Table 1. The genomic mapping of predicted miRNAs is illustrated in Fig. 3.

The constructed phylogeny provided an ancestry of novel miRNAs that did not match any reported miRNA family. Clustering provided their possible ancestry divergence and uniqueness to B. tabaci. The novel identified miRNAs were grouped with the known miRNA family, representing their putative family, which is visualized using different color patterns. Those novel identified miRNAs that did not group with any known family were denoted as unique miRNAs with the same color throughout the tree.

This figure represents the genetic mapping of B. tabaci novel miRNAs to visualize their genomic distribution and provide chromosomal enrichment information. The outer circle emphasizes the chromosomal number and the unaligned scaffolds, while the inner heatmap highlights the miRNA read number in the respective chromosome. The color gradients were used to comprehend the chromosomal and scaffold-mapped miRNAs.

Critical features of B. tabaci novel miRNAs

The carefully calculated parameters that met all critical criteria, as outlined below, strongly indicate the potential significance of the identified miRNAs.

miRNA family

The nomenclature of uniquely identified miRNAs from B. tabaci has offered valuable insights into the evolutionary origins and divergence of these predicted miRNAs in alignment with annotated miRNA families. Among the 81 predicted novel miRNAs, 22 successfully corresponded with established families, indicating a careful representation of unique expression and divergence from ancestral forms. Notably, most of these corresponding families comprised only one novel miRNA, highlighting their diversity within the broader category of miRNAs. Furthermore, certain families, such as mir-263 (5), mir-673 (4), and mir-9 (2), included more than one predicted miRNA, indicating a complex relationship in their secondary structure formation, despite the absence of conservation. The nomenclature for the predicted miRNAs was assigned following the standard naming system used in miRBase. Each novel miRNA name began with ‘btab’ (B. tabaci), and the remaining identifier was adopted according to the matched miRBase and Rfam families. The unmatched miRNAs were named uniquely by giving the term, ‘novel’ to highlight the status of the new report (Tables 2, 3; Figs. 4, 5).

Pre-, mature-, and star- miRNA sequences

The length of precursor miRNAs ranged from 54 to 79 nucleotides and 93–07 nucleotides, and with average lengths of 59 and 99 nucleotides from the whole genome and transcriptome, respectively, found novel miRNAs. Notably, the length of mature and star sequences was 18–2 nucleotides with characteristic complementarity, a primary attribute of mature and star sequences that ascertained the sense and antisense nature of final mature miRNAs. The documented sequence information of novel miRNAs is given in Tables 2, 3.

Minimal folding free energy (MFE) and MFE index (MFEI)

The reliability of predicted miRNAs depended on a crucial aspect of secondary structure formation that required enough MFE. In this study, the assessed MFE ranged between − 15.2 and − 36.7 and − 25.9 and − 50.1, with an average of − 25.17 and − 33.7 for the miRNA found from the whole genome and transcriptome, respectively. The MFEI calculated for predicted miRNAs ranged from 0.71 to 1.21-kcal/mol. In contrast, the MFEI for tRNAs, rRNAs, and mRNAs was found to be 0.64, 0.59, and 0.62–0.66-kcal/mol, respectively (Tables 4, 5).

Nucleotide composition

The GC and AU content varied significantly, ranging from 30.39 o 53% for GC and 49.51% to 69.61% for AU in the predicted miRNAs across the whole genome. In the transcriptome, their ranges fell between 33.9 nd 55.7% for GC and 44.3–3.16% for AU (Tables 4, 5). These findings indicate a notable enrichment of AU content, which is one of the keys to miRNAs. These AU-rich elements (AREs) in miRNAs and their targets facilitate mRNA decay through interactions with ARE-binding proteins. Moreover, AU-rich miRNAs tend to bind more effectively to GU-rich seed matches in 3′ UTRs, increasing regulatory flexibility 28,29.

Phylogenetics

The annotation process for predicted miRNAs derived from the whole genome and transcriptome employed a unique color-coding system to vividly illustrate their evolutionary divergence. This strategic approach not only underscores the emergence of unique novel miRNAs but also suggests that these miRNAs may carry distinct and significant functions. The phylogenetic tree constructed for these predicted novel miRNAs revealed compelling connections between previously identified novel miRNAs and the evolutionary lineages of their corresponding clades. This analysis identified four major clusters, divided into eight sub-clusters, emphasizing the complexity of miRNA diversity (Fig. 2). Bootstrap values range from 250 to 1000, reflecting the stronger support to lower nodes, while the higher nodes with smaller values indicate areas for further research. Conserved miRNA families like mir-1, mir-92, and mir-263 cluster distinctly from novel miRNAs, suggesting species-specific regulatory roles. The tree scale of 0.1 denotes minor sequence variations within certain miRNA families (Fig. 2). Importantly, the unique novel miRNAs that do not fit into any known family were distinctly annotated using a single color throughout the phylogenetic tree, emphasizing their individuality and potential significance. In contrast, the remaining sequences were thoughtfully grouped with known family miRNAs, reinforcing our understanding of their evolutionary relationships. This comprehensive approach enhances our grasp of miRNA diversity and underscores the intricate evolutionary pathways that have shaped these important regulatory molecules (Fig. 2).

Stem-loop qPCR validation

The computational analysis yielded a set of miRNAs that did not match any known miRNA families, which were successfully amplified from the total RNA extracted from adult whiteflies. Notably, ten novel miRNAs were validated through this stem-loop qPCR, which includes btab-miR-10-novel-b, btab-miR-754-novel, btab-miR-92a-novel-a, btab-miR-1-novel, btab-miR-novel-3, btab-miR-novel-1, btab-miR-novel-13, btab-miR-263-novel-a, btab-miR-2765-novel, and btab-miR-124-novel. The analysis of five miRNAs—btab-miR-754-novel, btab-miR-1-novel, btab-miR-novel-3, btab-miR-263-novel-a, and btab-miR-2765-novel demonstrated differential expression across B. tabaci developmental stages. Specifically, btab-miR-754-novel and btab-miR-2765-novel were consistently expressed in all four stages examined. In contrast, btab-miR-1-novel and btab-miR-novel-3 were detected in instar II, instar IV, and adult stages, whereas btab-miR-263-novel-a was exclusively expressed in the adult stage. These findings provide valuable insights into stage-specific miRNA expression patterns during development (Supplementary Fig. 1: S1). A similar validation procedure was conducted for aphids and leafhoppers, resulting in the successful amplification of five miRNAs: btab-miR-10-novel-b, btab-miR-754-novel, btab-miR-92a-novel-a, btab-miR-1-novel, and btab-miR-novel-3. The quantification cycle metrics and melting curve profiles provided strong evidence supporting the specificity and efficiency of the amplifications, as illustrated in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 1: S2. These results contribute valuable insights into the presence of novel miRNAs across different hemipteran species, underscoring their potential significance in post-transcriptional regulation.

Experimental validation of selected novel miRNAs, (a) Cq graph of B. tabaci, (b) melt curve analysis of B. tabaci, (c) gel figure of qPCR samples of B. tabaci, (d) Cq values of selected miRNAs of B. tabaci, (e) Cq graph of Aphid and Leafhopper, (f) melt curve analysis of Aphid and Leafhopper, (g) gel figure of qPCR samples of Aphid and Leafhopper, (h) Cq values of seleceted miRNAs across B. tabaci developmental stages, (i) Cq values of selected miRNAs of Aphid and Leafhopper. Color used in the subsection (d) represents the sample designation in the subsections (a) and (b).

Prediction of potential targets and functional annotation

The target prediction study showed promising results, revealing that the 81 novel miRNAs had multiple targets, with some having as many as 1000. Initially, targets exceeding the cutoff in MFE were individually ranked. Subsequently, those targets demonstrating concordance across all employed algorithms, specifically miRanda, PITA (Probability of Interaction by Target Accessibility), and TargetScan were extracted to ensure high-confidence, robust predictions. For MFE thresholds above -20 kcal/mol, miRanda and PITA identified 40,380 and 26,334 targets respectively, whereas TargetScan, applying a cut-off at an MFE of − 16 kcal/mol, detected 73,522 candidates. Ultimately, a consensus set of 1392 targets, validated across all three algorithms, was sorted (Supplementary File 3). The analysis further revealed that multiple microRNAs (miRNAs) concurrently targeted specific transcripts, with a total of 10,843 unique targets, of which 1,084 formed consistent pairs across prediction tools. Additionally, individual miRNAs were observed to target multiple mRNA transcripts, and several of them targeted multiple sites within the same transcript—recording a total of 4597 interaction instances. Among these interactions, 1743 had involved targets that aligned across algorithms. When the MFE threshold was relaxed to − 10 kcal/mol, the study identified 450,015 potential targets for all novel miRNAs. Subsequent filtering to enhance both sensitivity and specificity was performed at an MFE cutoff greater than − 30 kcal/mol, yielding 591 transcripts with MFE values ranging from − 30.1 to − 35.82 kcal/mol and miRanda scores spanning 140 to 184. Additionally, 36 targets were predicted using PITA, whereas only a single target was identified with TargetScan (Fig. 7a). Functional enrichment analysis of B. tabaci transcripts revealed a strong representation of pathways involved in cytoskeletal organization, transcriptional regulation, and energy metabolism, as indicated by GO terms such as actin cytoskeleton organization, ATP binding, and RNA binding (Fig. 8). KEGG analysis further supported these findings with enrichment in metabolic pathways, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and key signaling cascades including MAPK, mTOR, and calcium signaling, all of which are central to development, immune response, and environmental adaptation. Notably, these enriched functions correlate with the predicted targets of novel miRNAs derived from genomic sources, suggesting that these miRNAs may play critical regulatory roles in orchestrating gene networks essential for development, stress response, and other biological processes in B. tabaci (Fig. 9a). This highlights the importance of miRNA-mediated regulation in shaping the molecular basis of this insect’s adaptability and ecological success. Additionally, the complete annotation of the target predicted is presented in the Supplementary file 4. Finally, the study highlighted that the targets obtained with MFE above -30 included signaling proteins, kinase proteins, and nucleotide-binding proteins, emphasizing their important role in regulating plant immune responses (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). The current research has successfully validated ten candidate miRNAs through stem-loop qPCR, highlighting their existence with significant biological relevance and critical regulatory functions. These miRNAs demonstrated a MFE of less than − 30 kcal/mol and a miRanda score exceeding 140, indicating a strong binding affinity with their target genes. Specifically, btab-miR-124-novel is involved in regulating peptidase enzyme activity, while btab-miR-263-novel-b modulates gated and channel proteins. Additionally, btab-miR-2765-novel influences ion channels and transcription factors, btab-miR-novel-10 plays a vital role in neurogenesis and cellular development, and btab-miR-novel-1 regulates the biogenesis of both macro and micromolecules (Figs. 10 and 11; Supplementary File 5). The expression and presence of these miRNAs were further confirmed using stem-loop qPCR, emphasizing their essential roles in cellular function and metabolism. These findings open up exciting possibilities for the development of miRNA-based strategies in pest management in the future.

Conservancy

The conservation status of B. tabaci miRNAs revealed that the previously reported miRNAs, including btab-novel-24, btab-novel-56, btab-let-7, and btab-mir-2822 showed the highest conservancy across the miRNAs database. The results from conservation analyses conducted with the animal database indicated that all the currently predicted B. tabaci miRNAs demonstrated notable conservation among arthropod groups. The top 20 conserved miRNAs and their corresponding genetic groups are illustrated in Fig. 12. Interestingly, the miRNAs btab-miR-10-novel-b, btab-miR-754-novel, btab-miR-92a-novel-a, btab-miR-1-novel, and btab-miR-novel-3 have been successfully amplified in A. gossypii, A. biguttula, and B. tabaci, indicating their evolutionary conservation across hemipteran lineages (Supplementary File 6). This conservation suggests they may contribute to fundamental regulatory mechanisms related to host interactions, stress adaptation, or development.

Small RNA sequencing and whole genome predictions correlation

Small RNA sequencing of B. tabaci egg samples yielded 10 million raw reads, with 8 million (80%) remaining after quality filtering. Mapping to the B. tabaci genome revealed 107 known miRNAs and 37 novel miRNAs predicted by miRDeep2 (score ≥ 5, randfold; p < 0.05). Two miRNAs, OU963869.1_14981: Highest abundance (74,776 reads), with a Small RNA sequencing of B. tabaci egg samples yielded 10 million raw reads, with 8 million (80%) remaining after quality filtering. Mapping to the B. tabaci genome revealed 107 known miRNAs and 37 novel miRNAs predicted by miRDeep2 (score ≥ 5, randfold p < 0.05). Two miRNAs were found abundant, the highest one being OU963869.1_14981 (74,776 reads), with a miRDeep2 score of 38,126 and seed similarity to dme-miR-7-5p, and the second most abundant being OU963871.1_17976 (72,953 reads), sharing seed homology with dme-miR-278-3p. A subset of miRNAs, including btab-miR-263-novel-d, btab-miR-novel-26, btab-miR-novel-29, and btab-miR-137-novel, exhibited both sequence alignment and strand-specific expression, as supported by NGS reads. For instance, btab-miR-novel-26 showed strong evidence with the mature sequence taaggaactgtttgatgtggtga aligned to its genomic region. The mature strand uaaggaacuguuugaugugguga was also detected from miRNA-seq reads. These matched sequences demonstrate precise Dicer processing and stable expression in vivo (Fig. 9b; Supplementary Files 7 and 8).

Notably, conserved miRNA candidates such as btab-miR-novel-29 and btab-miR-137-novel mapped to different contigs (CAKKNF020000012.1 and CAKKNF020000013.1), but shared a common mature sequence auggcacuggaagaauucacggg, supporting their potential evolutionary relevance or duplication events. Also, btab-miR-3338-novel and btab-miR-92a-novel-b displayed variations of the mature motif auugcacuugucccggccua, aligned on chromosome OU963867.1, further suggesting sequence conservation and functional redundancy. An intriguing piece of information is that btab-miR-92a-novel-b was identified through both stem-loop and small RNA sequencing methods, thereby further enhancing the confidence in these predictions.

Discussion

Numerous recent studies have demonstrated the involvement of miRNAs in numerous biological and developmental processes as well as physiological reactions in insects 30. Gaining more knowledge about insect miRNAs and their targets may help us to understand the range of biological processes like insect development, reproduction, and immunity that underlie miRNA-mediated regulation as well as the functional importance of miRNAs 31,32. By uncovering these mechanisms, feature research can identify potential miRNA-based interventions, paving the way for innovative and sustainable pest management strategies that may be helpful in developing next-generational pest control strategies. Few works have been done to scan miRNAs from publicly available EST and whole genome details of insects. The EST sequences were largely explored for miRNAs in silico, which provided the opportunity to compare or match the target miRNAs with known miRNA sequences to detect miRNAs in a variety of agricultural plants 33,34,35. Indeed, many differential gene expression studies were conducted to monitor the induced expression of miRNAs 36,37,38, but less work was done to identify the regulatory RNAs using in silico analysis 39,40. Moreover, identifying miRNAs from the whole genome has not been done so far in both plant and animal genomes. These small non-coding RNAs have emerged as key regulators of gene expression, playing a critical role in various cellular processes. The discovery of these novel miRNAs can offer new insights into the intricate mechanisms of gene regulation and potentially lead to the development of novel therapeutic interventions. We used bioinformatic approaches to profile the miRNAs across the B. tabaci genome and validated the predicted miRNAs using machine-learning algorithms.

Since miRNAs play a significant biological role in therapeutics, the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, in silico miRNA identification techniques for animals, especially for humans, are highly in use 41. Numerous diseases, such as cancer, viral infections, rheumatic and cardiovascular illnesses, and neurological disorders, have been linked to abnormal miRNA expression and function 42. miRNAs were reported to be stable in human fluids, which makes them potential biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis 43. Similarly, utilizing miRNA-based biomarkers presents a robust strategy for differentiating between biotypes and ecotypes, allowing for the accurate identification of cryptic and genetically diverse organisms such as B. tabaci. This methodology can potentially improve our capacity to monitor population dynamics and devise targeted management strategies. Additionally, miRNAs act as therapeutic agents to treat a variety of human illnesses 44. Nanocarriers have been investigated for the targeted delivery and detection of miRNAs, enabling early diagnosis and therapy for miRNA-related disorders, particularly cancer 45. In many economically important plant species, particularly cereals like maize, the genomes are embedded with a substantial portion of repetitive sequences 46,47 that perturbed the in silico identification of miRNAs. In addition, the genomes of various plants, including wheat and barley, complicate in silico prediction and experimental evaluations of miRNA due to the homologous copies of miRNAs 48,49. Previous studies revealed that using the same criteria for identifying and annotating miRNAs among plant and animal genomes was inapplicable because there are considerable structural and functional differences between plant and animal miRNAs 48,50. In silico identification of small non-coding RNAs from insects using a standard prediction algorithm specifically developed for animal cells 41 may unravel the existence of the potential miRNA candidates. To date, the documented 48,880 miRNAs are reported from 271 different organisms, in which only 31 genetic groups were annotated experimentally 51. A large number of these accessions were only predicted by in silico analysis. Many miRNA sequences in insects were mainly identified using in silico methods but has no experimental confirmation, and there remains uncertainty over their validity in miRBase 51,52. Using miRNAs with experimental backing may lead to more reliable outcomes in identifying miRNAs in silico. However, potential issues such as inconsistent naming and incorrect annotations of mature miRNAs cause further inconsistencies and contradictions in downstream analysis procedures 53,54.

The stability of an RNA’s hairpin fold structure could be determined by its MFE. It is believed that precursor miRNAs have a lower MFE than other non-coding RNAs, which makes MFE a helpful parameter for miRNA prediction 55. The predicted novel miRNAs exhibited MFE values ranging from − 15.70 to − 50.1 kcal/mol, with an average of − 33.70 kcal/mol, aligning with the characteristic parameters of − 0.71 to − 1.21 kcal/mol 56. Sufficient MFE values assessed in this study signified the characteristic features of miRNAs predicted. High MFEI values were considered to be essential indicators for distinguishing miRNAs from other RNA species, including tRNAs (MFEI = 0.64), rRNAs (MFEI = 0.59), mRNAs (MFEI = 0.62–0.66), or pseudo-hairpins produced from coding sequences 57,58. The high MFEI values observed in our analysis were consistent and supported the genuineness and assurance of our miRNA identification approach, as reported earlier 56,58. The GC content of miRNAs plays a critical role in their biogenesis, stability, and regulatory function. High-GC miRNAs, such as those in the miR-17-92 cluster, exhibit enhanced thermodynamic stability and are often associated with conserved regulatory pathways, including cell proliferation and cancer 59,60. Conversely, AU-rich miRNAs, like miR-124, are more labile but enable rapid responses to cellular stress, highlighting a trade-off between stability and regulatory flexibility 61,62. This current study identified several high-GC miRNA candidates (e.g., btab-miR-92a-novel) that may regulate housekeeping genes, while low-GC miRNAs (e.g., btab-miR-novel-12) could mediate stress adaptation. he minimal size of the bulges determines the thermodynamic stability of plant microRNAs. This was an important consideration, especially when analyzing the microRNA-star sequence duplex, which should not be occupied by more than one loop structure 63. The secondary structure of identified novel miRNAs fulfilled the above criteria, with very few miRNAs, such as btab-miR-5252-novel, btab-miR-novel-9, and btab-miR-novel-25 showing bulged structure within mature sequences, which may be the result of a single nucleotide mismatch giving them a bulged appearance. However, the miRNAs with two bulges were also deemed legitimate, as several previous reports had described them as possible plant progenitors 64,65. The presence of two small bulges was also substantiated as a characteristic feature of miRNAs, indicating that the present predictions were not false. The current study also predicted miRNAs that were previously functionally annotated, such as bantam miRNA, which promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in Drosophila 66,67, and the let-7 miRNA family, which regulates the cell cycle, proliferation, and apoptosis 68,69. The miRNAs miR-13b and bantam were implicated in the developmental regulation of some insect species and were predicted to potentially target a broad range of transcripts, including several ones involved in chitin metabolic pathways or hormone signaling [81]. The significant threat that B. tabaci poses to various crops globally warrants increased attention to understand the essential role of small non-coding RNAs in biological processes. These RNAs are not only involved in crucial biological functions but also play a key role in how insects cope with pesticide pressures, challenging the successful use of synthetic pesticides. The microRNA miR-276-3p is essential for mediating resistance to cyantraniliprole in B. tabaci by regulating the CYP6CX3 gene. Under standard conditions, miR-276-3p targets and inhibits the expression of CYP6CX3. However, in resistant strains exposed to cyantraniliprole, there is an upregulation of CYP6CX3 and a concomitant downregulation of miR-276-3p. This observation indicates a significant role for miRNAs in modulating detoxification pathways, thereby enhancing insecticide resistance 70. Additionally, the increased expression of CYP6CM1, controlled by novel_miR-1517, was associated with B. tabaci’s resistance to imidacloprid 71,72. A recent study found that miR-263b impacted the susceptibility of Sitobion miscanthi to imidacloprid by interacting with the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) β1 subunit 73. The functional enrichment analysis revealed molecular adaptations of B. tabaci, with detoxification genes (P450s, GSTs, ABC transporters) strongly associated with insecticide resistance 74,75. The significant representation of cytoskeletal and vesicular trafficking pathways correlates with its efficient transmission of begomoviruses 76,77,78. The enrichment of metabolic and MAPK signaling pathways reflects the species’ metabolic flexibility 79. Our predicted novel miRNAs may regulate these key pathways, similar to findings in other hemipterans 80. This integrated analysis suggested miRNA-mediated regulation underpins B. tabaci pesticide resistance and viral transmission capabilities. More research is necessary to determine if the elevated miRNA expression in resistant populations is connected to their resistance, as those insect miRNAs reported so far have typically functioned via negative regulation. However, understanding their positive/negative regulatory roles could assist scientists in developing sustainable pest management strategies 81.

Several studies have shown that the chromosomal locations of miRNA genes impacted the production and maturation of miRNAs. Multiple miRNAs can originate from the same transcript or geneOlena and Patton 82. In the present study, genomic mapping of novel miRNAs to the whole genome using precursor coordinates suggested that small non-coding RNAs were distributed in clusters. These miRNAs were regulated by specific circuits, leading to variations in their expression levels in response to biotic and abiotic stressors 83,84. Therefore, gaining knowledge about the transcriptional control of miRNA genes and their genomic architecture is crucial to understanding their biogenesis 14.

miRNAs could target mRNAs using two binding patterns to the 3’-UTRs of target transcripts. The ‘seed region’ involves perfect complementarity between the target site and the 5’-end of the miRNAs 85, while the second pattern involves imperfect base pairings. Efforts are being made to understand the boundaries of the 3ʹ-UTRs in various species since robust pairing on the 3ʹ end of the miRNA can compensate for the low complementarity at the seed region to provide regulatory activities 86. This is crucial to understanding how miRNAs would be used for therapeutic applications and disease treatment 87. The mature and pre-miRNAs are highly conserved and regarded as evolutionarily conserved regulators of gene expression across various species of organisms. This strongly supported our revelations of the conservation status of B. tabaci miRNAs, which were previously shown to be conserved across the arthropod genetic groups 39.

To substantiate the predictions, real-time expression analysis was performed to corroborate the in silico data. Various molecular methodologies exist to authenticate real-time expression, particularly for miRNAs. Among these, stem-loop qPCR remains a preeminent and extensively adopted technique. This investigation employed the same approach that validated eight novel miRNAs. Researchers have adeptly utilized stem-loop qPCR to profile and verify the presence of novel miRNAs under diverse experimental conditions in B. tabaci 14,88. In this protocol, short RNAs were amplified by adding poly(A) tails and reverse transcribed using a poly(T) adaptor primer. PCR amplification ensued with a miRNA-specific forward primer and a poly(T) adaptor reverse primer. Upon electrophoresis on a 4% agarose gel, reverse transcribed miRNAs with ligated adaptor sequences produced discrete bands at 63–67 nucleotides. This miRNA synthesis exhibited a singular Cq value and a uniform dissociation curve 89. The present study yielded analogous outcomes in terms of Cq values and melting curve analysis.

These results underscore the successful integration of genome-based miRNA prediction and experimental validation through small RNA sequencing. The combined approach enabled the identification of authentic miRNAs with evidence of expression and processing. This comprehensive annotation of novel miRNAs expands the miRNA landscape in B. tabaci and provides a foundation for downstream analysis of their regulatory functions. Future studies involving target prediction, differential expression profiling across developmental stages, and pathway enrichment will offer insights into the biological significance of these novel regulatory molecules.

Materials and methods

Mining B. tabaci miRNAs

Computational approaches

Three computational methods were employed to potentially extract miRNAs from the whitefly genomic resources (Fig. 1). The first method involved obtaining expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database and aligning them with the known miRNAs from two sources, namely miRBase (https://www.mirbase.org/) 51 and InsectBase (http://v2.insect-genome.com/) 90, against ESTs to identify the existence of miRNA. The second approach was identifying miRNA distribution and their abundance from B. tabaci whole genome sequence, which was retrieved from NCBI and European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) repositories. The third computational approach was to mine the miRNAs from transcriptome sequences of B. tabaci exposed to different stress and biological interactions retrieved from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) 91. The predicted miRNAs were subjected to the downstream analyses.

Acquisition of sequences from databases

The unprocessed reads of transcriptome sequences were obtained from the NCBI Bioproject database utilizing the SRA toolkit (v.3.2), which has been installed on a Linux operating system and executed through the command line interface. The relevant accession information is detailed in additional file 1 (Additional file 1; Table 1). The total miRNA sequences were sourced from miRBase 51. B. tabaci-specific miRNA sequences were retrieved from InsectBase 90 and were used as the reference sequence. Most importantly, miRbase is the chief source for the miRNA repository, but unfortunately, no single accession is represented for B. tabaci. The acquired sequences were subjected to the CD-HIT test to remove redundant sequences from reference and EST sequences, and they were subsequently involved in the remaining process.

Mining from ESTs

The final EST sequences that underwent non-redundant clustering were subsequently utilized for further computational analysis. The NCBI BLAST+ (v.2.15.0) 92 search algorithm was installed on a Linux system and generated a local custom database comprising known mature miRNAs by employing the make blastdb function, utilizing the nucleotide database type and sparse seqids to facilitate the identification of sequence identifiers. The clustered ESTs were then queried against this locally generated database, using an e-value threshold of 3, to identify potential miRNA candidates.

Mining from transcriptome assembly

The transcriptomic sequences underwent a thorough quality check to detect the presence of adapter sequences, which were subsequently removed using Trimmomatic-0.39 93. The remaining sequences were assembled using the De novo approach with the assistance of Trinity (v.2.15.2) 94, Spades (v.4.0) 95, Velvet 96, and AbySS (v.2.3.10) 97. Trinity and SPAdes were employed to facilitate the assembly of larger transcriptomic libraries, capitalizing on their efficiency in processing short-read sequences from extensive datasets. Conversely, Velvet and AbySS were utilized to assemble smaller RNA libraries, given their exceptional proficiency in handling siRNA sequences with a minimal k-mer threshold of fewer than 25 nucleotides. Following the assembly process, the sequences underwent analysis using ShortStack (v. 4.1.0) 98, employing stringent parameters to ensure high-confidence miRNA annotation retaining only uniquely mapped reads (–map u), with a strand-cutoff of 0.95 and a minimum coverage of 10 reads (–mincov 10). The focus was on miRNAs within the size range of 18 to 24 nucleotides (–dicermin 18 –dicermax 24). For specific parameters and workflow details, please refer to Supplementary File 2. This enabled the identification of both known and potential novel microRNAs (miRNAs) derived from the transcriptomic sequences, utilizing species-specific databases and comprehensive references of reported mature miRNAs.

Mining from the whole genome

The whole genome of B. tabaci (GCA_001854935.1) is currently accessible at the scaffold level and has been designated as a reference genome by NCBI. Recently, Rothamsted Research in Harpenden, United Kingdom, contributed a comprehensive chromosomal assembly of B. tabaci (GCA_918797505.1), which features minimal unassembled regions. This assembly serves as an important reference genome for the analysis of miRNAs. To facilitate this research, a local database of the whitefly genome was established using the BLASTn search algorithm, ensuring efficient data retrieval and analysis. SUmirFind_sRNA.pl script 99 was employed to map miRNAs across the whole genome by matching species-specific and whole mature miRNAs from miRBase as a query with a searching parameter of less than two nucleotide mismatches. The mapped reads were retrieved from the whole genome using a custom bash script based on the genome coordinates generated from SUmirFind_sRNA.pl.

The sequences extracted were analyzed to determine the possibility of containing miRNAs using miRDeep (v. 2.0.1.2) software (https://github.com/rajewsky-lab/mirdeep2) 100. At the outset, the extracted reads were aligned to the reference genome using mapper.pl, allowing perfect matches to reduce alignment discrepancies. Subsequently, the mapped reads underwent analysis with miRDeep2.pl, which incorporated established mature and precursor miRNA sequences from miRBase and species-specific annotations. Various general characteristics were considered during the prediction process, such as the formation of a stable secondary structure with minimal folding energy (MFE) and MFE index (MFEI), the pattern of secondary loop formation, the presence of dicer cleavage site adjacent to the mature sequences, the presence of seed sequences, the probability of being other forms of RNAs (tRNA, rRNA, and snRNAs), and the A + U composition of precursor sequences being higher than the G + C content. Stable RNAfold (v.2.7.0) software (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi) 101 was used to check the first two criteria. miRDeep was used to verify the presence of a DICER cleavage site and seed sequences. The fifth criterion was tested using the Rfam database (https://rfam.org/) 102 integrated into miRDeep software. Finally, the miRDeep tool predicted the miRNAs from the input sequences that met all the characteristics mentioned above. The predicted miRNAs were engraved with their precursor genome coordinates, while the probability of these predictions being other forms of RNAs was also determined and reported as either positive or negative.

Phylogenetics of B. tabaci miRNAs

The miRNA evolutionary relationship was determined using the RAxML-NG 103 (v.2.0) algorithm in the linux terminal 104. An evolutionary tree was generated using the Neighbor-joining approach with a bootstrap value of 1000.

Conservation of B. tabaci miRNAs

sRNAcon package from sRNAtoolbox (https://arn.ugr.es/srnatoolbox) 105 was used to determine the conservation status of miRNAs predicted and reported for B. tabaci. We then analyzed the query miRNA sequences for conservation against arthropod miRNAs with default parameters. Additionally, miRNA sequences from 24 hemipteran families were obtained from the InsectBase 90. The conservation of these miRNA sequences across different hemipteran orders was also analyzed and discussed.

Target prediction and functional annotation of novel miRNAs

To identify the potential targets of these miRNAs miRconstarget (animals) 105 integrated with three target prediction algorithms, working best against animal tissue sources, including miRanda 106, TargetScan 107, and PITA 108 with simple seed algorithms, which match the 8 bp seeding sequence defined based on experimentally proven miRNA families, were employed with the default parameters. The coding sequences of B. tabaci were retrieved from the Ensembl 109 and NCBI databases subjected to the target prediction process. The results obtained from the prediction software were then sorted stringently with the MFE of more than -15 for TargetScan and -20 for miRanda and PITA to maximize the sensitivity of the target prediction. It ensured that only high-quality targets were identified and further analyzed. The final targets were then annotated for their functional role using ShinyGO-0.80 (https://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/) 110 and eggNOG 111, tools that can annotate genes with their functional category, subcellular localization, and signaling pathways. Furthermore, the high-quality sorted targets were then annotated for pathways governed using KEGG 112. It helped in understanding the functional role of the predicted targets and their biological relevance to the organism under study. Overall, the detailed approach helped gain a better insight into the regulatory role of predicted novel miRNAs and identify potential targets for further analysis.

Experimental validation of in silico miRNAs

Insect sources

Populations of key cotton insect pests, Bemisia tabaci (silver leaf whitefly), Aphis gossypii (cotton aphid), and Amrasca biguttula (cotton leafhopper) were established and maintained under controlled glasshouse conditions (30 ± 2 °C; 70 ± 5% RH; 12L) at Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU), Coimbatore, India.

Silver leaf whitefly, B. tabaci

B. tabaci population was established during January 2022 at the glasshouse of the Department of Agricultural Entomology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU), Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, on 35–50 days old cotton plants in pots (variety Co17, TNAU). Female whiteflies were initially collected from the cotton (Co17) fields at the Department of Cotton, TNAU, Coimbatore. Genomic sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) gene using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplicon employing universal primers 113 confirmed the B. tabaci population aligned to Asia I population. The biological stages of B. tabaci collected from culture were preserved using RNAlater (Invitrogen, USA) in -80 (Thermo Fisher, USA) for further analysis.

Cotton aphid, A. gossypii

A. gossypii was established in January 2023 at TNAU, Coimbatore, using 35–50 days old cotton plants (Co17 variety). The aphids were sourced from local cotton fields, and their identity was confirmed through genomic sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) gene.

Cotton leafhopper, A. biguttula

A. buguttula was established in January 2023 at Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU), Coimbatore, using cotton plants aged 35 to 50 days (Co17 variety). The insects were sourced from nearby cotton fields, and their identification was confirmed using genomic sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) gene.

Stem-loop qPCR

To validate the computationally predicted miRNA, stem-loop qPCR of short RNAs was performed [47]. Total RNA was extracted from three biological replicates of insect samples using Trizol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers for the ten randomly selected miRNAs were designed using PrimerBLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast). Pulsed-reverse transcriptase reaction (PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit, Takara Bio Inc.) was performed using 100 ng RNA per sample in a 20 μL total volume using small RNA-specific RT-primers designed as described by Chen et al. 114 (Supplementary file 1; Table 2).

For the stem-loop qPCR, a template consisting of 2 μL of the RT reaction was employed in a 20 μL total volume for 39 cycles using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq ™ II (Takara Bio Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instructions in CFX Opus 96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories India Pvt. Ltd.). Nuclease-free water served as the no-template control along with miRNA-specific RT products. The PCR was run at 95 °C for two minutes and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 56 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 25 s. After that, a melt curve analysis was conducted using the CFX Maestro software (Bio-Rad).

Small RNA sequencing

Total RNA, encompassing the small RNA fraction, was extracted from cell samples using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. The aqueous phase was purified using the miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Germany), which is specifically designed to enrich RNAs shorter than 200 nucleotides. Each biological sample was processed in two separate replicates, and all subsequent steps, including quantification, quality assessment, library preparation, and sequencing, were conducted independently for each replicate. RNA concentration and purity were first evaluated using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). For precise quantification of small RNAs, the samples were examined using the Qubit 4 Fluorometer along with the Qubit RNA Broad Range Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The integrity of the RNA was verified by gel electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel (Lonza, Belgium), and only samples exhibiting RIN ≥ 7.0 (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, USA) proceeded to library preparation.

Small RNA libraries were constructed utilizing the QIAseq miRNA Library Kit (Qiagen, Germany), in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. This procedure encompassed adapter ligation, reverse transcription, and PCR amplification. The libraries were purified using QIAseq Beads (Qiagen, Germany) to eliminate unincorporated primers and adapter dimers. The quality and size distribution of the final libraries were assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with the High Sensitivity DNA Chip (Agilent Technologies, USA), thereby confirming the expected insert size range (~ 140–160 bp, including adapters). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, SanDiego, CA) using single-end 50 bp read chemistry. Both replicates were sequenced independently to account for biological variability.

Bioinformatics analysis

Raw sequencing reads underwent initial processing with Cutadapt 115 to remove adapter sequences, and the quality of the trimmed reads was assessed using FastQC 116. Reads ranging from 18 to 25 nucleotides were kept for further analysis. The cleaned reads were aligned to the reference genome with Bowtie, allowing 1–2 mismatches to ensure high mapping stringency. The identification of known and novel microRNAs was performed using the miRDeep2 algorithm 117, which combines sequencing alignment, secondary structure predictions, and probabilistic scoring to distinguish genuine miRNAs from background noise. Each replicate was analyzed separately to generate miRNA profiles specific to each sample. After the initial analysis, read counts from both replicates were combined for a comprehensive overview. This combined approach ensured that the final miRNA profile accurately reflected consistent and reproducible expression patterns across biological replicates.

Conclusion

Machine learning algorithms effectively identified potential miRNAs from whole genome and transcriptome data for the cotton whitefly B. tabaci, an important pest of many vegetable crops transmitting begomoviruses. This approach involved training a model on known miRNA sequences and using that model to predict potential miRNAs in the genome or transcriptome of the target organism, B. tabaci. It significantly reduced the time required to identify miRNAs and provided preliminary putative results. The experimental validation of randomly selected novel miRNAs confirmed their existence and functions in the B. tabaci genome at the global cellular scale. Additionally, the accuracy and reliability of these predictions depend on the quality and completeness of the genomic and transcriptomic data used as input. By providing a faster and more efficient means of identifying potential miRNAs, the described methods in this study can accelerate research on miRNA-mediated gene regulation that may contribute to developing new pest management strategies using genomic tools.

Data availability

The analysis results are presented in the main tables of the manuscript, while additional detailed results and supporting information are provided in the supplementary files. All sequencing data analyzed were deposited in the NCBI database and their accession numbers are included in Supplementary File 1, Table 1. The raw sequencing reads derived from Small RNA sequencing of B. tabaci, as generated within the scope of this study, have been deposited into the NCBI database and are publicly accessible under the SRA accession number SRR34286297.

References

Boykin, L. M., Bell, C. D., Evans, G., Small, I. & De Barro, P. J. Is agriculture driving the diversification of the Bemisia tabaci species complex (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodidae)? Dating, diversification and biogeographic evidence revealed. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 1–10 (2013).

De Barro, P. J., Liu, S.-S., Boykin, L. M. & Dinsdale, A. B. Bemisia tabaci: A statement of species status. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 1–19 (2011).

Chi, Y. et al. Differential transmission of Sri Lankan cassava mosaic virus by three cryptic species of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci complex. Virology 540, 141–149 (2020).

Jones, D. R. Plant viruses transmitted by whiteflies. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 109, 195–219 (2003).

Ghosh, S. & Ghanim, M. Factors determining transmission of persistent viruses by Bemisia tabaci and emergence of new virus–vector relationships. Viruses 13, 1808 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. Lethal and sublethal effects of cyantraniliprole, a new anthranilic diamide insecticide, on Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) MED. Crop Prot. 91, 108–113 (2017).

Cimino, A. M., Boyles, A. L., Thayer, K. A. & Perry, M. J. Effects of neonicotinoid pesticide exposure on human health: A systematic review. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, 155–162 (2017).

Rodriguez Coy, L., Plummer, K. M., Khalifa, M. E. & MacDiarmid, R. M. Mycovirus-encoded suppressors of RNA silencing: Possible allies or enemies in the use of RNAi to control fungal disease in crops. Front. Fungal Biol. 3, 965781 (2022).

Fire, A. et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811 (1998).

Montgomery, M. K. RNA interference: historical overview and significance. RNA Interference, Editing, and Modification: Methods and Protocols, 3–21 (2004).

Montgomery, T. A. et al. AGO1-miR173 complex initiates phased siRNA formation in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20055–20062 (2008).

Klattenhoff, C. & Theurkauf, W. Biogenesis and germline functions of piRNAs. (2008).

Wang, X.-H. et al. RNA interference directs innate immunity against viruses in adult Drosophila. Science 312, 452–454 (2006).

Guo, Q., Tao, Y.-L. & Chu, D. Characterization and comparative profiling of miRNAs in invasive Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) B and Q. PLoS ONE 8, e59884 (2013).

Huvenne, H. & Smagghe, G. Mechanisms of dsRNA uptake in insects and potential of RNAi for pest control: a review. J. Insect Physiol. 56, 227–235 (2010).

Okamura, K., Ishizuka, A., Siomi, H. & Siomi, M. C. Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes Dev. 18, 1655–1666 (2004).

Lee, Y. S. et al. Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell 117, 69–81 (2004).

Saito, K., Ishizuka, A., Siomi, H. & Siomi, M. C. Processing of pre-microRNAs by the Dicer-1–Loquacious complex in Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol. 3, e235 (2005).

Liu, Q. et al. R2D2, a bridge between the initiation and effector steps of the Drosophila RNAi pathway. Science 301, 1921–1925 (2003).

Förstemann, K. et al. Normal microRNA maturation and germ-line stem cell maintenance requires Loquacious, a double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein. PLoS Biol. 3, e236 (2005).

Richards, S. et al. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature 452, 949–955 (2008).

Klingler, M. & Bucher, G. The red flour beetle T. castaneum: Elaborate genetic toolkit and unbiased large scale RNAi screening to study insect biology and evolution. EvoDevo 13, 1–11 (2022).

Brown, S. J. et al. The red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera): A model for studies of development and pest biology. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, pdb.emo126 (2009).

Roignant, J.-Y. et al. Absence of transitive and systemic pathways allows cell-specific and isoform-specific RNAi in Drosophila. RNA 9, 299–308 (2003).

Price, D. R. & Gatehouse, J. A. RNAi-mediated crop protection against insects. Trends Biotechnol. 26, 393–400 (2008).

Upadhyay, S. K. et al. siRNA machinery in whitefly (Bemisia tabaci). PLoS ONE 8, e83692 (2013).

Darrington, M., Dalmay, T., Morrison, N. I. & Chapman, T. Implementing the sterile insect technique with RNA interference—A review. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 164, 155–175 (2017).

Barreau, C., Paillard, L. & Osborne, H. B. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles?. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 7138–7150 (2005).

Jing, Q. et al. Involvement of microRNA in AU-rich element-mediated mRNA instability. Cell 120, 623–634 (2005).

Ren, Y., Dong, W., Chen, J., Xue, H. & Bu, W. Identification and function of microRNAs in hemipteran pests: A review. Insect Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.13449 (2024).

Pani, A. & Mahapatra, R. K. Computational identification of microRNAs and their targets in Catharanthus roseus expressed sequence tags. Genomics Data 1, 2–6 (2013).

Chaudhary, V. Development of Micro-RNA and EST-SSR Markers for Diversity Analysis in Clusterbean [Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub][With CD Copy], Mol. Biol. Biotechnol., CCSHAU, Hisar, (2019).

Sunkar, R. & Jagadeeswaran, G. In silico identification of conserved microRNAs in large number of diverse plant species. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 1–13 (2008).

Kalvari, I. et al. Non-coding RNA analysis using the Rfam database. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 62, e51 (2018).

Vivek, A. In silico identification and characterization of microRNAs based on EST and GSS in orphan legume crop, Lens culinaris medik. (lentil). Agri Gene 8, 45–56 (2018).

Van den Brande, S. et al. Identification and profiling of stable microRNAs in hemolymph of young and old Locusta migratoria fifth instars. Curr. Res. Insect Sci. 2, 100041 (2022).

Kakumani, P. K. et al. Identification and characteristics of microRNAs from army worm, Spodoptera frugiperda cell line Sf21. PLoS ONE 10, e0116988 (2015).

Chang, Z. X. et al. Identification and characterization of microRNAs in the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera. Insect Sci. 23, 452–468 (2016).

Zhang, B. H., Pan, X. P., Wang, Q. L., Cobb, G. P. & Anderson, T. A. Identification and characterization of new plant microRNAs using EST analysis. Cell Res. 15, 336–360 (2005).

Asokan, R., Roopa, H., Rebijith, K., Ranjitha, H. & Krishna, N. K. In silico mining of micro-RNAs from Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 13 (2014).

Esteller, M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 861–874 (2011).

Parakh, A. Dynamics of PIWI-interacting RNAs in Disease and Medicine. NeuroQuantology 20, 1879 (2022).

Matulić, M. et al. miRNA in molecular diagnostics. Bioengineering 9, 459 (2022).

Coradduzza, D. et al. Role of nano-mirnas in diagnostics and therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6836 (2022).

Ho, P. T., Clark, I. M. & Le, L. T. MicroRNA-based diagnosis and therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7167 (2022).

Brenchley, R. et al. Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Nature 491, 705–710 (2012).

Mehrotra, S. & Goyal, V. Repetitive sequences in plant nuclear DNA: Types, distribution, evolution and function. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 12, 164–171 (2014).

Mendes, N. D., Freitas, A. T. & Sagot, M.-F. Current tools for the identification of miRNA genes and their targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 2419–2433 (2009).

Kleftogiannis, D. et al. Where we stand, where we are moving: Surveying computational techniques for identifying miRNA genes and uncovering their regulatory role. J. Biomed. Inform. 46, 563–573 (2013).

Axtell, M. J., Westholm, J. O. & Lai, E. C. Vive la différence: Biogenesis and evolution of microRNAs in plants and animals. Genome Biol. 12, 1–13 (2011).

Kozomara, A., Birgaoanu, M. & Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: From microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D155–D162 (2019).

Meng, Y., Shao, C., Wang, H. & Chen, M. Are all the miRBase-registered microRNAs true? A structure-and expression-based re-examination in plants. RNA Biol. 9, 249–253 (2012).

Van Peer, G. et al. miRBase Tracker: Keeping track of microRNA annotation changes. Database 2014, bau080 (2014).

Budak, H., Bulut, R., Kantar, M. & Alptekin, B. MicroRNA nomenclature and the need for a revised naming prescription. Brief. Funct. Genom. 15, 65–71 (2016).

Bonnet, E., Wuyts, J., Rouzé, P. & Van de Peer, Y. Evidence that microRNA precursors, unlike other non-coding RNAs, have lower folding free energies than random sequences. Bioinformatics 20, 2911–2917 (2004).

Zhang, B., Wang, Q. & Pan, X. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in animals and plants. J. Cell. Physiol. 210, 279–289 (2007).

Schwab, R. et al. Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Dev. Cell 8, 517–527 (2005).

Kantar, M. et al. Subgenomic analysis of microRNAs in polyploid wheat. Funct. Integr. Genom. 12, 465–479 (2012).

Bartel, D. P. Metazoan microRNAs. Cell 173, 20–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006 (2018).

Volinia, S. et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2257–2261. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0510565103 (2006).

Elkon, R., Ugalde, A. P. & Agami, R. Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation: Extent, regulation and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 496–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3482 (2013).

Shao, Y. et al. Involvement of histone deacetylation in MORC2-mediated down-regulation of carbonic anhydrase IX. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 2813–2824. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq006 (2010).

Medley, J. C., Panzade, G. & Zinovyeva, A. Y. microRNA strand selection: Unwinding the rules. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 12, e1627. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1627 (2021).

Vishwakarma, N. P. & Jadeja, V. J. Identification of miRNA encoded by Jatropha curcas from EST and GSS. Plant Signal. Behav. 8, e23152 (2013).

Panda, D. et al. Computational identification and characterization of conserved miRNAs and their target genes in garlic (Allium sativum L.) expressed sequence tags. Gene 537, 333–342 (2014).

Brennecke, J., Hipfner, D. R., Stark, A., Russell, R. B. & Cohen, S. M. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113, 25–36 (2003).

Luan, J.-B. et al. Global analysis of the transcriptional response of whitefly to Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus reveals the relationship of coevolved adaptations. J. Virol. 85, 3330–3340 (2011).

Scott, R. C., Juhász, G. & Neufeld, T. P. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr. Biol. 17, 1–11 (2007).

Schulte, L. N., Eulalio, A., Mollenkopf, H. J., Reinhardt, R. & Vogel, J. Analysis of the host microRNA response to Salmonella uncovers the control of major cytokines by the let-7 family. EMBO J. 30, 1977–1989 (2011).

Zhang, M.-Y. et al. MicroRNA-190-5p confers chlorantraniliprole resistance by regulating CYP6K2 in Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 184, 105133 (2022).

Yang, X. et al. RNA interference-mediated knockdown of the hydroxyacid-oxoacid transhydrogenase gene decreases thiamethoxam resistance in adults of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci. Sci. Rep. 7, 41201 (2017).

Gong, P.-P. et al. Novel_miR-1517 mediates CYP6CM1 to regulate imidacloprid resistance in Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Gennadius). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 194, 105469 (2023).

Zhang, B.-Z. et al. MicroRNA-263b confers imidacloprid resistance in Sitobion miscanthi (Takahashi) by regulating the expression of the nAChRβ1 subunit. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 187, 105218 (2022).

Bass, C. & Field, L. M. Gene amplification and insecticide resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 67, 886–890 (2011).

Karatolos, N. et al. Over-expression of a cytochrome P450 is associated with resistance to pyriproxyfen in the greenhouse whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum. PLoS ONE 7, e31077 (2012).

Hasegawa, D. K. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals networks of genes activated in the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci when fed on tomato plants infected with Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Virology 513, 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2017.10.008 (2018).

Rana, V. S. et al. Implication of the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, collagen protein in begomoviruses acquisition and transmission. Phytopathology 109, 1481–1493 (2019).

Vinoth Kumar, R. & Shivaprasad, P. Plant-virus-insect tritrophic interactions: Insights into the functions of geminivirus virion-sense strand genes. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20201846 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Two cytochrome P450 genes are involved in imidacloprid resistance in field populations of the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 107, 343–350 (2013).

Liang, P. et al. A plant virus manipulates both its host plant and the insect that facilitates its transmission. Sci. Adv. 11, eadr4563. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adr4563 (2025).

He, J. et al. MicroRNA-276 promotes egg-hatching synchrony by up-regulating BRM in locusts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 584–589 (2016).

Olena, A. F. & Patton, J. G. Genomic organization of microRNAs. J. Cell. Physiol. 222, 540–545 (2010).

Rajwanshi, R., Chakraborty, S., Jayanandi, K., Deb, B. & Lightfoot, D. A. Orthologous plant microRNAs: Microregulators with great potential for improving stress tolerance in plants. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127, 2525–2543 (2014).

Dolata, J. et al. Salt stress reveals a new role for ARGONAUTE1 in miRNA biogenesis at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Plant Physiol. 172, 297–312 (2016).

Rajewsky, N. microRNA target predictions in animals. Nat. Genet. 38, S8–S13 (2006).

Ghosh, Z., Chakrabarti, J. & Mallick, B. miRNomics—The bioinformatics of microRNA genes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 363, 6–11 (2007).

Maziere, P. & Enright, A. J. Prediction of microRNA targets. Drug Discov. Today 12, 452–458 (2007).

Wang, B. et al. MicroRNA profiling of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci Middle East-Aisa Minor I following the acquisition of Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus. Virol. J. 13, 1–14 (2016).

Hasegawa, D. K. et al. Deep sequencing of small RNAs in the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci Reveals Novel MicroRNAs potentially associated with Begomovirus acquisition and transmission. Insects. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11090562 (2020).

Mei, Y. et al. InsectBase 2.0: A comprehensive gene resource for insects. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D1040–D1045 (2022).

Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D20-d26. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1112 (2022).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 10, 1–9 (2009).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Trinity: Reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644 (2011).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Zerbino, D. R. & Birney, E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18, 821–829 (2008).

Simpson, J. T. et al. ABySS: A parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res. 19, 1117–1123 (2009).

Axtell, M. J. ShortStack: Comprehensive annotation and quantification of small RNA genes. RNA 19, 740–751. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.035279.112 (2013).

Alptekin, B., Akpinar, B. A. & Budak, H. A comprehensive prescription for plant miRNA identification. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 2058 (2017).

An, J., Lai, J., Lehman, M. L. & Nelson, C. C. miRDeep*: An integrated application tool for miRNA identification from RNA sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 727–737 (2013).

Lorenz, R. et al. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 6, 1–14 (2011).

Griffiths-Jones, S., Bateman, A., Marshall, M., Khanna, A. & Eddy, S. R. Rfam: An RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 439–441 (2003).

Kozlov, A. M., Darriba, D., Flouri, T., Morel, B. & Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: A fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 35, 4453–4455. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305 (2019).

Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J. & Higgins, D. G. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2.3.1–2.3.22 (2003).

Rueda, A. et al. sRNAtoolbox: An integrated collection of small RNA research tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W467–W473 (2015).

Anton, J. E. et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 5, R1–R1 (2004).

Agarwal, V., Bell, G. W., Nam, J.-W. & Bartel, D. P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 4, e05005 (2015).

Kertesz, M., Iovino, N., Unnerstall, U., Gaul, U. & Segal, E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat. Genet. 39, 1278–1284 (2007).

Zerbino, D. R. et al. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D754–D761 (2018).

Ge, S. X., Jung, D. & Yao, R. ShinyGO: A graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 36, 2628–2629 (2020).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Kawashima, S., Okuno, Y. & Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D277–D280 (2004).

Krause-Sakate, R. et al. First detection of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) MED in Oklahoma and development of a high-resolution melting assay for MEAM1 and MED discrimination. J. Econ. Entomol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toae228 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem–loop RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e179–e179 (2005).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Andersson, R. et al. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Version 0.11 2 (2010).

Friedländer, M. R., Mackowiak, S. D., Li, N., Chen, W. & Rajewsky, N. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 37–52 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the Department of Agricultural Entomology and the Department of Plant Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics, Center for Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, for the server facilities provided. I also extend my thanks to NF-OBC (UGC-CSIR) for providing fellowship.

Funding

The research did not receive any funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K., M.M., and B.V conceived the study and supervised the project. P.K. and J.M implemented software and performed analyses. M.M. and J.M. curated data sets. All authors discussed the results and implications. P.K., M.M., B.V., PS.S., and S.S wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolanchi, P., Marimuthu, M., Venkatasamy, B. et al. Genomic exploration of Bemisia tabaci microRNAs using predictive modeling and confirmation through experimental evidence. Sci Rep 15, 34006 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12989-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12989-2