Abstract

This study aimed to identify miRNA-based biomarkers in a multi-ethnic cohort of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals to enhance preparedness for future variants of concern. A total of 31 healthy controls and 154 infected patients were enrolled, from which 13 matched controls and 38 infected nasal swab samples were analyzed using miRNA sequencing, followed by qRT-PCR validation. Among the 1788 miRNAs detected, 14 differentially expressed miRNAs and four novel miRNAs were identified, with novel-miR-264-5p showing a ≥ 2-fold change. Correlation with clinical markers highlighted several miRNAs as potential prognostic biomarkers. Seven miRNAs, including miR-146b-3p, miR-154-5p, miR-5010-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-335-3p, miR-30c-5p, and miR-202-5p, showed strong prognostic potential. Combined ROC analysis demonstrated that a panel of top-performing miRNAs significantly enhanced diagnostic accuracy (AUC 0.939–0.972; p < 0.0001). Moreover, integrating miRNA biomarkers with clinical parameters further improved performance (AUC = 0.982; p < 0.0001). miR-146b-3p, detected exclusively in infected patients, emerged as a highly specific biomarker. Several nasal miRNAs mirrored blood profiles, highlighting the utility of nasal swabs for non-invasive monitoring. Collectively, these findings suggest that miRNA-based biomarkers, alone or combined with clinical markers, offer a promising platform for COVID-19 prognosis and diagnosis, and lay groundwork for future miRNA-based antiviral strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and infected over 778 million individuals globally and caused over 7 million deaths until June 14, 2025 (https://covid19.who.int/). SARS-CoV-2 infection may result in symptoms ranging from being completely asymptomatic to having severe disease manifestations, such as the severe pulmonary disease, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)1,2. It can also induce inflammatory responses, such as cytokine storm and activation of chemokines, hypoxemia, disruption of kidney and liver enzymes among individuals, etc.,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. The infection occurs in both genders and can lead to multi-organ failure. However, men are more prone to severe COVID-19 than women, irrespective of age10. Co-morbidities, including previous lung infections, diabetes, hypertension, heart-associated risk factors, obesity, older age, immune disorders, and other organs manifestations, are all associated with induction of severe disease2,3,11,12,13.

Since the emergence of COVID-19, numerous studies have attempted to establish the crucial role of host responses at the molecular and cellular levels to the severity of the disease in the infected patients. Viral infections in general can alter host-immune as well as cellular transcriptional responses to facilitate their replication and infectivity. This can result in molecular changes at cellular levels that can be detected clinically14,15,16,17,18,19. Interestingly, not every patient shows a similar host-response pattern and there is always a need to find molecular biomarkers that may differentiate COVID-19 infected patients from non-infected ones through simple and straightforward clinical tests20,21,22.

Currently, researchers are emphasizing the exploration of microRNAs (miRNAs) as biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis, especially due to their stability and resistance to degradation in routinely examined body fluids, including nasopharyngeal discharge, saliva, urine, blood, plasma, and serum19,23,24,25,26,27,28. In viral infections, miRNA-based biomarkers can be especially useful since host miRNAs are induced as a host’s natural innate anti-viral response, better known as RNA interference (RNAi), to control virus infections29,30. Viruses, on the other hand, can exploit host miRNAs to subvert this response to facilitate their own replication or manipulate the host’s immune responses31,32. This has been observed in a number of clinically important viruses, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B & C viruses, influenza, dengue, and others33,34,35,36,37,38. An added advantage of identifying dysregulated miRNAs in diseases is the use of this information for eventual development of miRNA-based therapeutics39. MiRNAs are small, non-coding functional RNAs encoded by genes and expressed in cells and by viruses as key regulators of gene expression. They function in a post-transcriptional manner by attacking specific host mRNAs via sequence complementarity, causing their translational inhibition or degradation40,41,42,43. Thus, miRNAs regulate gene expression in a highly targeted manner and the best way to identify and quantitate them are approaches based on next generation sequencing (NGS)44.

At present, most of the published data in this area of research is mainly driven from miRNAs isolated from blood samples; however, nasopharyngeal sample collection was the most widely used method to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection globally19,45,46,47. It is well known that miRNAs are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and released in body fluids in a manner that each type of body fluid reveals its own canvas of miRNAs, a profile that changes upon disease induction and its severity. In COVID-19, there are only a few studies that report miRNA expression analysis from the nasopharyngeal samples in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, despite the wide use of this sample in diagnosis9,19,48,49,50,51. Most of these studies were limited to only a selection of miRNAs and did not investigate the whole miRNA expression profile.

To overcome this limitation, we used miRNAseq followed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-qPCR) to characterize miRNAs expressed during SARS-CoV-2 infection. While COVID-19 is no longer as deadly as it initially was and seems to have adapted well to the human population, the danger persists that a variant-of-concern (VOC) may emerge anytime that could cause another major pandemic, as is the case with other respiratory viruses like influenza. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify miRNAs that are uniquely expressed in a consistent manner following SARS-CoV-2 infection so that such miRNAs can be used as biomarkers for not only disease prognosis, but also the ability to develop novel RNA-based anti-virals and therapeutics that can be created rapidly to tackle any future pandemics.

Materials and methods

Ethical permission and informed consent

The study was approved by the UAE University (UAEU) Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC approval no: ERH-2020-7219 2020-22) and the Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee (DSREC) of the Dubai Health Authority (DHA) (DSREC approval nos: DSREC-11/2020_16 and DSREC-11/2021_08). Informed Consent was taken from each subject following DHA and UAEU established procedures using approved consent forms available both in English and Arabic. Moreover, we confirmed that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

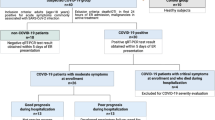

Control and patient enrollment

The patients included in this study were confirmed positive for the virus by the COVID-19 nasal swab RT-qPCR test approved by the national health authorities prior to enrollment into the study. They were admitted to the Rashid Hospital, Dubai, the largest tertiary care hospital managing patients with COVID-19 infection since the start of the pandemic in the UAE. The control subjects were recruited from the staff of the Rashid Hospital as well as the UAE University. Each subject tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection by the COVID-19 RT-qPCR test performed on samples taken from nasal swab. A total of 154 infected patient samples were collected from September 2021- March 2022, while 31 control samples were collected for the study.

Clinical data

Clinical and demographic data for the enrolled patients was collected from the electronic medical records of the Rashid Hospital, Dubai. The patients were assessed for any medical symptoms (either acute or chronic) at the time of enrollment. Most of the symptoms included cough, diarrhea, chest problems, fever, and nausea. The comorbidities reported by infected individuals included diabetes, hypertension, thyroid issues, lipidemia, anemia, asthma, viral infections, kidney problems, previous history of chest infections, and heart-related issues. Chest X-rays were performed, depending upon the severity of disease symptoms. Routine laboratory tests were performed as per hospital protocol.

RNA extraction and MiRNA sequencing

MiRNAs were extracted from nasal swab samples using the Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin miRNA mini kit (cat. no. 740971), as described by the manufacturer, and quantified using Nano Drop in house. The miRNA sample integrity was tested by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and sequenced at the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, Hong Kong) using UMI small RNA Library prep via the DNBSEQ platform (SE 50-single end; 50 bp size) at 20 M (20 million) clean read resolution.

RNAseq data analysis

RNAseq was performed on 38 SARS-CoV-2 infected and 13 control (non-infected) individuals, as described above. The raw data was filtered using BGI in-house software known as SOAPnuke v1.5.252 and the impurities in the data like sequences without inserts, sequences that were too long or of low-quality, poly A sequences, small fragment sequences, and sequences with adaptor contaminations were removed. The clean sequences were subjected to filtration based on read length and the sequences ranging from 18 to 30 nt were selected for the next step. The Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to compare the quality of gene expression between each sample, which showed higher similarities between each sample within a group. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to remove any outliers from samples. The filtered clean reads were then subjected to quality control using FASTQ53.

After sequencing, an average of 26.93 million reads (of ~ 50 nt length) were generated per sample and subjected to quality control. The clean reads were aligned to the reference genome sequence GCF_000001405.39_GRCh38.p13 (Homo sapiens), with an average alignment of 78.63% using Bowtie254. The results were submitted to the BGI in-house software Dr. Tom accessed through an online server for further analysis. The raw and analyzed data (BioProject accession number: PRJNA1049129) can be downloaded from the server (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1049129) for data re-analysis and further processing.

RNAseq: DEGs analysis

After sequencing and cleaning (removal of adaptors), the data in fastq file(s) format were analyzed using the automated Dr. Tom software from BGI that allowed visualization and analysis of raw data. The DESeq2 method55 (Q-value/adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05) was used to detect differentially expressed miRNAs. The miRNAs with adjusted p-value of ≤ 0.05 and log2FC ≥ 2/≤ −2 were considered as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and presented in red (upregulated) or green (downregulated) throughout the manuscript. All of the data were downloaded from Dr. Tom and re-analyzed using Microsoft Excel for any discrepancies. Venn diagrams were drawn for the overlapping miRNAs/transcripts using the online platform Bioinformatics & Evolutionary Genomics from Van de Peer laboratory website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). Heatmaps were generated using Multiple Experiment Viewer v4.9.056. The volcano and other plots used in this study were generated through Dr. Tom and were further improved accordingly.

Prediction of possible targeted mRNAs and associated pathways

MiRNAs function by targeting mRNAs; however, the number of experimentally verified mRNA targets of miRNAs are still limited. To overcome this lacuna, there are several methods (either supervised or semi-supervised) based on support vector machine (SVM). Most of these methods predict miRNA-mRNA interactions based on high-throughput sequencing experiments or from other verified sources. Three commonly used databases include: miRDB57 (https://mirdb.org/), TargetScan58 (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/), and DIANA-microT-CDS59 (http://www.microrna.gr/microT-CDS). These databases were employed to predict targets for the miRNAs identified in this study primarily due to limited available target-interaction data.

Identification of experimentally validated MiRNAs targets

Experimentally-validated miRNA targets were extracted from the miRTarBase60 (https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn/~miRTarBase/miRTarBase_2022/php/index.php), miRpathDB61 (https://mpd.bioinf.uni-sb.de/mirnas.html?organism=hsa.), and miRwayDB62 (http://www.mirway.iitkgp.ac.in/) databases. These databases collect miRNA-target interactions after surveying existing literature and classify them as strong or poor targets based on reporter assays. In this study, we chose the targets associated with strong experimental evidence only.

Functional enrichment of gene ontology (GO) and pathway analysis

The list of predicted and experimentally identified targeted genes were separately uploaded to DAVID (https://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp63 for gene ontology (GO) and pathway analysis using Homo sapiens as the reference species. The GO analysis plots genes according to their function, biological processes, cellular presence, and molecular functions. DAVID generated the list of genes involved in several biological pathways using KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes: https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html)64 and Reactome (https://reactome.org/)65 pathway databases.

RT-qPCR assays

Real time RT-qPCR was used to validate the miRNAseq results obtained. This was accomplished by retesting 15 patient miRNA samples analyzed by miRNAseq for 16 miRNAs using miRNA-based TaqMan assays from Applied Biosystems (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). Briefly, the extracted RNAs were first converted into cDNAs using the TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit, as per manufacturer’s directions (cat. no. A28007). This was followed by conducting TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assays for the miRNAs listed in Table 1 using the TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (cat. no. 4444964) and the QuantStudios 7 Flex Real-Time PCR system. A 384-plate format was used to test the miRNAs in triplicates.

Statistical analysis

To distinguish miRNAs expression between control and infected patients, a p value < 0.05 (student’s t-test) and Q value < 0.05 (False Discovery Rate (FDR) using Storey-Tibshirani procedure) were used. Levene’s test for equality of variances was used for comparing clinical data using SPSS v.26. GraphPad Prism v8 software was used to create Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves using the expression profiles of the miRNAs, as well as to generate other graphs presented in this study. The area under the curve (AUC) with a p value < 0.05 was used to assess the ability of a miRNA to distinguish between control and infected patients. AUC with p value < 0.05 for any miRNA could predict the usefulness of a miRNA to distinguish between control and infected patients effectively. To further account for multiple comparisons and reduce the risk of false positives, FDR correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg method was applied to ROC p-values. Only FDR-adjusted p-values (p-adjusted) below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For other graphical data, a p value < 0.05 was considered as a significant change.

Results

Patient demographics

This study encompassed a total of 31 control individuals (23 males (74.2%) and 8 females (25.8%), and 154 infected patients (116 males (75.3%) and 38 females (24.7%). The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a diverse and multinational country, home to people from various parts of the world. While the participants included in this research hailed from 40 different countries (Fig. 1a), a significant portion of them originated from India (n = 44; 23.8%), Philippines (n = 22; 11.9%), Pakistan (n = 18; 9.7%), UAE (n = 10; 5.4%), Egypt (n = 9; 4.9%), and Iran (n = 7; 3.8%). Additionally, there were 6 participants from Jordan and Iraq (3.2%), 5 from Bangladesh (2.7%), as well as 4 from Lebanon and Palestine (2.2%). Furthermore, Belgium, China, Nepal, Poland, Senegal, Sudan, and Syria were represented by 3 participants each (1.62%), while Australia, Ethiopia, Russia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, UK, and USA had 2 participants each (1.08%). Finally, Afghanistan, Armenia, Burundi, the Czech Republic, Eritrea, Germany, Ghana, Indonesia, Malaysia, Morocco, Switzerland, Thailand, Vietnam, and Yemen each had 1 participant, with one participant remaining unclassified (0.54%).

Clinical data shows distorted levels of ferritin, CRP, WBC, ALT, urea, & GFR in infected patients

Figure 1b shows the comparison of other demographic and clinical parameters between the control and infected groups. The mean age of the control and infected groups was 44.23 ± 11.3 and 46.67 ± 13.1 years, respectively. The age variation was not statistically different within either control or infected groups (Fig. 1; Table 2). Both the control and infected groups showed similar body mass index (BMI) of ~ 27–28, revealing an overall overweight cohort. Although the controls showed presence of common morbidities like hypertension and diabetes, they were never reported to be previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 at the time of data collection. Some clinical laboratory data for the control group could not be included in this study due to the unavailability of test reports or because these tests were not conducted since the individuals were not experiencing any illness. Nonetheless, the available data for the control group fell within the already defined normal value range. Among the 154 infected patients at the time of infection, 55 (35.7%) had received vaccinations. The vaccines administered included Sinopharm BIBP (n = 38), Pfizer-BioNTech (n = 10), and other vaccines (n = 7), with the majority having received two doses of any vaccine (n = 44). A majority of the infected participants (n = 86; 55.8%) had cough, fatigue, fever, and shortness of breath at the time of infection. While X-ray reports were not available for controls, they were taken for 104/154 (67.5%) of the infected patients. Among the enrolled patients, 35 (22.7%) required respiratory support with oxygen delivery rates of up to 6 L/min and 51 (33.1%) with > 6 L/min.

Visual representation of demographic and clinical outcomes of the participants. (a) A map displays the diverse origin of the participants of this study, representing 40 different countries across the globe. The intensity of green colors on the map indicates varying participant numbers from each country, with darker shades representing more participants and lighter shades indicating fewer. The world map was created using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Excel LTSC Professional Plus 2024, 64-bit). (b) Comparative analysis of age, BMI, plasma levels of IL-6, ferritin, D-dimer, CRP, lymphocyte, WBC, and platelet count, hemoglobin levels, ALT, AST, urea, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) between uninfected and SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. The red or green scatter plots represent significantly up- or downregulated clinical markers, while orange indicates non-significant change.

Routine or pre-defined laboratory tests were conducted for each infected patient. These tests involved the measurement of various clinical markers in patient blood, including ferritin, D-dimer, IL-6, C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell (WBC) & lymphocyte count, platelet count, hemoglobin levels, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), urea, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). WBCs represent a broader category of cells involved in the body’s immune response than lymphocytes which are a specific subtype of white blood cells that play key roles in adaptive immunity, including T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells. For example, lymphopenia, which is a decrease in the number of lymphocytes in the blood, is a common finding in patients with severe COVID-19, while the total WBC count can vary in the same patients, depending on factors such as the presence of secondary bacterial infections or other inflammatory conditions. The levels of these clinical markers were then compared with either control or established normal ranges (Fig. 1; Table 2). A significant elevation was identified in the plasma concentrations of ferritin, CRP, and ALT among infected patients, surpassing the defined normal range. Induced levels of WBC, hemoglobin, and urea were also noted, but within the normal range, compared to the control. A marked reduction in GFR was observed compared to controls despite remaining within normal ranges, while a slight reduction in lymphocytes was observed. Although elevated levels of D-dimer and IL-6 were observed in infected patients, insufficient data precluded their inclusion in subsequent analysis.

Finally, in terms of vaccines, at the time of sample collection, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was not yet widespread. Among the 13 healthy controls, 2 individuals (15.4%) had received Pfizer vaccinations, while the remaining 11 were unvaccinated. In the infected group, 17 of our infected patients (44.7%) were vaccinated: 6 patients had received the Pfizer vaccine, 9 had received Sinopharm, and 2 had received Covishield. The remaining 21 infected patients were unvaccinated.

SARS-CoV-2 infection significantly alters expression of a small subset of host MiRNAs

RNA was extracted from the nasopharyngeal swabs. Depending upon the amount and quality of the RNA, a select group of samples were analyzed by miRNAseq. Nevertheless, statistically significant number of samples were selected, including 13 control and 38 individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. The average age of the control and infected patient was 47.62 ± 12.76 and 47.66 ± 12.92 years, respectively, while the male/female ratio was 3:1 for both groups (Table 3).

Figure 2 shows the quality of data and the overall results obtained from the miRNAseq analysis. The heatmap displaying the raw expression data (Fig. 2a), the bar graphs representing transcript expression profiles from individual samples (Fig. 2b), as well as the two groups with data represented as box plots (Fig. 2c), demonstrated consistent distribution within each sample from both groups, highlighting reliability of the data. The initial data analysis yielded a total of 1788 transcripts, with 1456 of them being previously known and 332 identified as novel miRNAs (Supplementary Data S1). Among the miRNAs detected, 1218 (67%) were expressed in both the control and infected groups, 78 (4.3%) miRNAs were uniquely expressed in the control group, while 492 (27.1%) were uniquely expressed in the infected group (Fig. 2d). Pearson correlation of miRNA expression changes between control and infected groups revealed that SARS-CoV-2 infection altered ~ 2.6% of the host miRNAs (Fig. 2e). Of the significantly altered miRNAs, 44 were known and 4 were novel miRNAs (29 up- and 15 downregulated; with p and Q values < 0.05) that may be able to distinguish between control from infected groups (Fig. 2f). Despite miRNAseq being a well-established and reliable technique that may not necessitate additional validation66, we took the extra step of confirming our overall miRNAseq findings. This was achieved by randomly selecting 15 RNA samples (7 control and 8 infected) that had been sequenced and subjecting them to TaqMan RT-qPCR assays for 16 miRNAs (two as endogenous controls). The results from our RT-qPCR analysis indicated that, with the exception of two miRNAs (miR-5010-3p and miR-2110), the remaining samples exhibited a similar trend in miRNA expression (non-significant variance) to what was observed in the miRNAseq analysis (Fig. 3). Our findings demonstrate a superiority over the previously established normal range, with a 15–20% non-concordance in gene expression between RT-qPCR and miRNAseq.

Summary of the miRNA expression analysis of the raw data. In this study, 13 control and 38 infected samples were subject to miRNAseq. MiRNA sequencing resulted in 1788 transcripts that were identified as potential miRNAs. The data was analyzed using the fully automated program Dr. Tom from BGI. (a) Heatmap of the hierarchal clustered raw data representing control and infected groups. (b) Tukey box plots showing the expression of miRNAs in individual control and infected samples after normalization. (c) Tukey box plot comparing the whole group level distributions of miRNAs expression data after normalization. (d) Pearson’s correlation plot representing the correlation (r) values between control and infected groups. (e) Venn diagram of intersection of miRNAs expressed in control and infected groups representing 1296 control and 1710 infected miRNAs in sub groups with fold change (FC) > 0, 1 and 2. (f) Volcano plot of the differentially regulated miRNAs. Red and green dots represent up- and downregulated miRNAs with FC ≥ 1.

Characterization of the differentially regulated miRNAs observed in infected patients

Next, we closely analyzed the 48 miRNAs with p/Q values < 0.05 observed in the infected patients. As shown, among the 44 known miRNAs, 29 were upregulated and 15 were downregulated (Fig. 4a and b). However, only 36 of the 44 showed a fold change of > 1, with 24 being upregulated and 12 downregulated (Fig. 4b). Additionally, 14 miRNAs (12 upregulated and 2 downregulated) showed a fold change greater than ± 2 (Fig. 4b). Notably, miR-146b-3p and miR-365b-3p were significantly upregulated, while miR-202-5p was markedly downregulated (as shown in Fig. 4c; Table 4). Among the four novel miRNAs examined, novel-miR-285-5p displayed significant upregulation, whereas the other three novel miRNAs, miR-115-5p, miR-189-5p, and miR-264-3p, were downregulated in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Table 4).

Quantitative RT-PCR validation of the miRNAseq data. The relative normalized expression values (log 2 of infected/control) of the individual samples obtained from the miRNAseq analysis (n = 13 control and 38 infected) were compared with those obtained from the RT-qPCR data (n = 7 control and 8 infected). The red and green box and violin graphs show up- and down-regulated miRNAs, while the blue depicts the results that contradict the findings of the miRNAseq analysis. The floating line for every bar represents the mean expression value. The p value shows difference in mean (student’s t-test) for each miRNA in the miRNAseq and RT-qPCR cohort.

Summary of the differentially regulated miRNAs in the infected patients. DEG analysis identified 48 miRNAs with p/Q values < 0.05 with 44 known and 4 novel miRNAs. (a) Heatmap of the hierarchal clustered DEGs in individual infected samples. The blue boxes represent downregulated miRNAs, while yellow boxes show upregulated miRNAs in infected samples when compared to the control. These boxes represent log2 (Infected/Control) values for individual infected samples. (b) Bar graph representing up- and downregulated miRNAs in infected vs. control groups. Red bars represent up- while green bar represent downregulated miRNAs. (c) Volcano plot of differentially expressed up- (red dots) and down- (green dots) regulated 14 miRNAs in the infected group when compared to the control.

miRNAs may serve as possible prognostic markers in defining SARS-CoV-2 infected patients

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the potential of differentially regulated miRNAs as prognostic markers when identifying SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. This was accomplished by conducting ROC analysis of each miRNA that helps discriminate the true negatives from true positives. Thus, ROC curves were created for each known miRNA that showed differential regulation in our study (with a fold change of ± 2 or more), as well as for the novel miRNAs identified during our research. Furthermore, we constructed ROC curves for four previously-reported miRNAs with an FC < 2 in our study (miR125-5p, miR-151b, miR590-3p, and miR-625-5p) (Table 5), but that had been shown to have potential as biomarkers to test their overall diagnostic performance in our SARS-CoV-2-infected patients67. These ROC curves were drawn using normalized miRNA read counts levels observed in both the control and infected groups. The analysis of the ROC area under the curve (AUC) was used as a feature used to measure the accuracy of our biomarkers. Several miRNAs, including miR-146b-3p (AUC = 0.999, p < 0.0001), miR-154-5p (AUC = 0.891, p = 0.002), miR-335-3p (AUC = 0.874, p < 0.0001), and miR-30c-5p (AUC = 0.761, p = 0.004), demonstrated excellent discriminative ability between infected and control samples. (Fig. 5a). Among the novel miRNAs, N-miR-264-5p showed a high diagnostic value with an AUC of 0.902 (p < 0.0001), while N-miR-115-5p also displayed strong potential (AUC = 0.792, p = 0.001). (Fig. 5b).

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of differentially regulated miRNAs in COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls. ROC analysis was conducted using RNA sequencing data from 51 nasal swab samples (control: n = 13, infected: n = 38). (a) ROC curves for 12 upregulated and 2 down regulated known miRNAs showing FC ≥ ± 2 identified through RNA sequencing. (b) ROC curves of 4 novel miRNAs identified in this study. (c) ROC curves for previously reported circulating miRNAs validated using expression data from our cohort. (d) Combined ROC curves showing the improved discriminative power when multiple miRNAs were combined as biomarker panels. ROC curves were drawn for these reported miRNAs using read count expression data from our study. In all ROC plots, red and green lines represent predictive curves for upregulated and downregulated miRNAs, respectively; the dashed blue line indicates the random classifier (reference line), whereas orange line represents predictive curves for combined miRNAs. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) values and corresponding p-values are indicated for each miRNA.

The ROC curves for the previously reported circulating miRNAs associated with viral infections were evaluated using expression data from our study. MiRNAs such as miR-125-5p (AUC = 0.746, p = 0.007), miR-151b (AUC = 0.749, p = 0.006), and miR-590-3p (AUC = 0.823, p < 0.0001) demonstrated robust predictive performance, validating previous reports (Fig. 5c). The optimal sensitivity and specificity values for identified markers in our study ranged from 65.91 to 100% and 61.54–100%, respectively, revealing high specificity with low to zero false rates since an AUC value of 1 indicates 100% accuracy (Supplementary Data S2)68. The cut-off values for differentially regulated miRNA biomarkers were also determined based on normalized read counts to achieve an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity using ROC curve analysis (Supplementary Data S2). This approach provides a robust estimate of the classification potential of the identified miRNAs within our cohort, aligning with methodologies previously described in biomarker research68,69.

To account for multiple comparisons, the FDR correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg method was applied to ROC p-values. Only FDR-adjusted p-values (p-adjusted) below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. This correction ensured that the significance of miRNAs as biomarkers is not due to random chance when evaluating multiple candidates. After correction, miR-146b-3p, miR-154-5p, miR-5010-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-335-3p, miR-30c-5p and miR-202-5p emerged as the most promising biomarker candidates (Fig. 5a). These miRNAs demonstrated strong discriminative power, with AUC values ranging from 0.75 to 0.99 and statistically significant p-values after multiple testing correction. Finally, combined ROC curve analyses, integrating multiple top-performing miRNAs (such as miR-146b-3p, miR-154-5p, miR-335-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-30c-5p, and miR-202-5p) significantly enhanced diagnostic performance, achieving AUC values between 0.939 and 0.972 (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5d). These findings highlight the potential advantage of using multi-miRNA panels over individual biomarkers for improving COVID-19 diagnosis from nasal swab samples.

Clinical markers and miRNAs showed significant correlation among each other

In our study, we noticed notable changes in both clinical indicators and miRNA expression among individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 when compared to those who were healthy. To delve deeper into their connections, we conducted a correlation analysis by calculating the Pearson’s coefficient that evaluates the linear relationship between variables (Fig. 6).

Correlation analysis and diagnostic performance of clinical markers and miRNA biomarkers in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), p-values, and R² values were calculated to assess associations between clinical markers and differentially expressed miRNAs. Analyses were conducted using RNA sequencing data and clinical parameters from up to 51 samples (controls: n = 13; infected: n = 38). (a) Heatmap representing Pearson’s correlation coefficients among clinical markers, including ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell count (WBC), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), urea, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Significant correlations are indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). (b) Heatmap showing Pearson correlation values among selected potential biomarker miRNAs. (c) Scatter plots illustrating significant individual correlations between specific clinical markers (ferritin, CRP, GFR, urea) and candidate miRNAs (N-miR-115-5p, N-miR-264-5p, N-miR-30c-5p, and miR-5010-3p). (d) ROC curve analysis assessing the diagnostic performance of individual clinical markers (ferritin, CRP, urea, and GFR), their combined performance, and performance in combination with selected miRNAs. Integration of miRNA expression profiles with clinical markers markedly improved diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.982, p < 0.0001).

This analysis uncovered significant associations not only within the clinical markers or miRNA expression levels, but also between these two categories. Within the clinical markers, we observed both positive and negative correlations. For instance, ferritin displayed significant positive correlations with CRP, WBC, and ALT, while CRP exhibited a positive correlation with urea but a negative correlation with GFR. Additionally, GFR showed a strong negative correlation with urea levels in COVID-19 infected patients (Fig. 6a).

Notably, we also detected significant correlation among differentially regulated miRNAs. For this analysis, we selected miRNAs with an AUC greater than 0.75 and a p-value less than 0.05. These miRNAs included miR-154-5p, miR-5010-3p, miR-335-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-202-5p, miR-590-3p, miR-625-3p, novel-miR-115-5p, and novel-miR-264-5p (Supplementary Data S2 and Fig. 5). Our results revealed positive correlation between several miRNAs pairs, such as miR-154-5p/miR-5010-5p, miR-5010-3p/miR-30c-5p, miR-335-3p/miR-30c-5p, miR-30c-5p/miR-5010-3p, miR-202-5p/miR-625-5p, miR-590-3p/miR-625-5p, novel-miR-115-5p/novel-miR-264-5p, as well as miR-625-5p/miR-202-5p (Fig. 6b). Additionally, significant negative correlations were observed between miR-154-5p/novel-miR-264-5p, miR-5010-3p/novel-miR-115-5p, miR-335-3p/novel-miR-264-5p, miR-30c-5p/novel-miR-115-5p and novel-miR-264-5p (Fig. 6b).

Remarkably, we also detected meaningful associations between the expression values of clinical markers and miRNAs expression levels (Fig. 6c). Individual scatter plot analyses further confirmed significant correlations between selected miRNAs and key clinical markers. N-miR-115-5p levels negatively correlated with ferritin concentrations, while N-miR-30c-5p levels positively correlated with urea and CRP. Furthermore, miR-5010-3p demonstrated a positive association with urea and a negative association with GFR. Similarly, N-miR-264-5p levels were significantly associated with GFR, highlighting their potential relevance to kidney function during SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 6c).

Next, ROC curve analysis was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic performance of individual clinical markers and their combination with miRNAs (Fig. 6d). Among the clinical markers, ferritin (AUC = 0.931), CRP (AUC = 0.844), GFR (AUC = 0.777), and urea (AUC = 0.753) demonstrated reasonable discriminative ability between infected and control groups. When clinical markers were combined, diagnostic performance improved (AUC = 0.951, p = 0.002). Importantly, integrating selected miRNA biomarkers with clinical markers further enhanced diagnostic accuracy, achieving an AUC of 0.982 (p < 0.0001), suggesting that a combined miRNA-clinical marker panel could serve as a highly sensitive and specific approach for detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection. Overall, our findings demonstrate a notable connection between the expression levels of specific miRNAs and clinical markers, revealing a biological association between the two. This association has the potential to serve as valuable prognostic markers for distinguishing SARS-CoV-2 infected patients from healthy individuals.

Differentially-expressed miRNAs share crucial biological pathways associated with disease severity

Next, we aimed at identifying the targets of the differentially-regulated miRNAs observed in our study. While numerous computer-based tools are available for predicting potential miRNA targets, we chose to focus solely on experimentally verified target genes for our specific miRNAs. To identify these targets, we conducted a thorough search of online databases, including miRTarBase, miRpathDB, and miRwayDB, which revealed that out of 14 miRNA that exhibited FC > ± 2, ten miRNAs, including miR-30c-5p, miR-132-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-18a-3p, miR-154-5p, miR-335-3p, miR-146b-3p, miR-202-5p, and miR-103a-2-5p targeted a total of 40, 34, 18, 7, 6, 5, 5, 3, and 2 human genes, respectively, while there were no experimentally-validated targets identified for the remaining four miRNAs (Table 5).

To gain further insights into whether the genes we predicted as experimental targets share various biological pathways, we initially constructed a protein network encompassing all proteins transcribed by these genes using the STRING database. Among the 122 genes, 118 were found to be interconnected (resulting in 118 nodes and 344 edges) at higher confidence STRING settings (Fig. 7a). Subsequently, we conducted searches for associated KEGG pathways, biological processes, molecular functions, and diseases using the DAVID database. DAVID analysis yielded 112 biological pathways (Supplementary Data S3) with a p-value < 0.05, including prominent pathways such as FoxO, MAPK, neurotrophin, PI3-AKT, prolactin, relaxin, TGF-β, AGE-RAGE, ErbB, and apelin signaling (Fig. 7b). The number of genes associated with each pathway are indicated by the size of the circle shown (Fig. 7b).

Network analysis further revealed that many genes associated with multiple pathways could be regulated by similar miRNAs (Fig. 7c & Supplementary Data S4). For example, among the miRNAs identified in this study, the MAPK signaling pathway could be influenced by miR-132-3p, miR-18a-3p, miR-28-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-202-5p, and miR-146-3p. Similarly, the crucial PI3-AKT pathway is linked to miR-132-3p, miR-18a-3p, miR-28-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-335-3p, and miR-154-5p. The same was true of many other genes, including AGE-RAGE, Apelin, FoxO, Relaxin, Neurotrophin, Prolactin, ErbB, and chemokine.

Gene ontology analysis demonstrated that the predicted experimentally verified genes in this study regulate numerous biological processes, including transcription, apoptosis, morphogenesis, protein phosphorylation, and cell proliferation, among others, as shown in Fig. 7d & Supplementary Data S5) and molecular functions, such as protein binding, DNA binding, enzyme binding, miRNA binding, and transcription factor regulation, as illustrated in Fig. 7e & Supplementary Data S6). Furthermore, expression of these genes was associated with various diseases, especially many different types of cancers (breast, lung, ovarian, colorectal, prostate, oral, stomach, etc.), bone mineral density disease (osteoporosis), hypercholesterolemia, kidney failure, and human papillomavirus infection (Fig. 7f & Supplementary Data S7). These findings underscore the potential implications of dysregulated miRNAs in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients as they may have significant consequences.

Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway analysis of experimentally verified targeted genes. Ten of the differentially regulated miRNAs (FC > ± 2) identified in our study were used to predict their target genes and associated biological pathways. (a) Protein-protein interactions in miRNAs-associated targets during SARS-CoV-2 infection using STRING. Proteins showing two or more interactions were included in this figure. (b) Biological pathways associated with target genes in our study. (c) Interaction analysis demonstrating the connections between miRNAs (shown in blue), associated genes (shown in black), and the targeted pathways (shown in red). The blue lines show the connection between the miRNAs and their target genes, while the green lines represent the connections between miRNAs and the targeted pathways. This network of identified pathways, genes, and miRNAs was constructed and visualized using Cytoscape and resulted in 54 nodes and 154 edges. The genes associated with only one miRNA or pathway were excluded. (d) Biological processes associated with the targeted genes. (e) Molecular functions associated with the targeted genes. (f) Association between the targeted genes and various diseases.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify miRNA-based biomarkers in our ethnically-rich population infected with SARS-CoV-2 for prognosis/diagnosis purposes and beyond (Fig. 1a). SARS-CoV-2 infection often leads to abnormal inflammatory and biochemical markers, including elevated D-dimers, ferritin, CRP, urea, creatinine, and abnormal cell counts, contributing to organ dysfunction and ICU admissions13,70. In our cohort, ferritin, hemoglobin, CRP, WBC, ALT, and urea were significantly elevated, while GFR was reduced. IL-6 and D-dimer levels exceeded normal thresholds, but lacked control group comparisons (Fig. 1b; Table 2). Notably, ferritin correlated with CRP, WBC, ALT, and GFR, while urea was linked to lower GFR and higher CRP. These correlations highlight their potential as screening markers for infected patients (Fig. 6).

Our study is unique due to its comprehensive data collection and diverse cohort, comprising individuals from over 40 countries in the UAE (Fig. 1a). This diversity enhances insights into SARS-CoV-2-induced clinical and biochemical alterations. Due to sample quality limitations, sequencing analysis was conducted on 57 samples (control: n = 13, infected: n = 38), with additional validation performed on 15 RT-PCR samples. While the cohort size may impact statistical power, similar studies have used comparable sample sizes (Table 6), and the application of FDR correction, inclusion of age- and sex-matched controls, and RT-PCR validation strengthens the reliability of our findings.

We analyzed 14 differentially expressed miRNAs (≥ 2-fold change), along with four novel and four known miRNAs, as potential biomarkers using ROC analysis (Figs. 2, 3 and 4; Table 5). Seven miRNAs, including miR-146b-3p, miR-154-5p, miR-5010-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-335-3p, miR-30c-5p and miR-202-5p, showed strong prognostic potential (AUC: 0.75–1, p < 0.05). Additionally, four previously reported miRNAs, though less dysregulated, exhibited consistent expression (miR125-5p, miR-151b, miR590-3p, and miR-625-5p)71, reinforcing their biomarker potential (Figs. 5, Table S2). Despite being less significantly dysregulated, these four miRNAs were also reported to be dysregulated in blood samples51,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82.

In this study, cut-off values for miRNA biomarkers were established using normalized read counts to balance sensitivity and specificity through ROC curve analysis (Supplementary Data S2). Higher sensitivity thresholds were emphasized for early screening to minimize false negatives, whereas specificity was prioritized in the context of disease severity assessment or prognostic evaluation, to avoid overestimating risk and ensuring accurate clinical decision-making. These thresholds serve as reference points within our cohort and should be further validated in future studies tailored to specific clinical applications. Furthermore, to ensure consistency across samples and comparability, all read counts were normalized for library size and distribution prior to ROC analysis, enhancing the robustness of classification estimates. While absolute expression levels may vary across detection platforms, normalization methods, and different cohorts, the consistent directionality of deregulated miRNAs (their up- or down-regulation) supports their reproducibility as biomarkers. Therefore, while the specific cut-off values identified here may require external validation, they offer a reliable reference for assessing clinical utility within this study.

Interestingly, our combined ROC curve analyses further demonstrated the advantage of using multi-miRNA panels for diagnostic purposes. Integration of multiple top-performing miRNAs, including miR-146b-3p, miR-154-5p, miR-335-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-30c-5p, and miR-202-5p, significantly enhanced diagnostic performance, with AUC values ranging from 0.939 to 0.972 (p < 0.0001). These results suggest that a multi-miRNA panel may offer superior sensitivity and specificity compared to individual biomarkers. Such panels could be particularly valuable in improving the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection from nasal swab samples, providing a more reliable molecular diagnostic tool in clinical practice.

Next, we compared our findings with differentially regulated miRNAs in WBCs, plasma, and serum (Fig. 8). While our findings provide valuable insights into the role of miRNAs identified using nasal swab, it is important to consider the potential relationship between miRNA profiles in blood samples. Blood-based miRNA profiling is widely used for biomarker discovery due to the stability and systemic nature of circulating miRNAs; however, nasal swabs offer a more direct and localized assessment of respiratory tract infections. Despite the fact that most studies used miRNA sequencing, the expression profiles varied, with only a few miRNAs overlapping (Fig. 8). Notably, Chen et al., 202072 and Fernandez-Pato et al., 202274 showed 86% and 100% concordance with our nasal swab findings using WBCs and plasma, respectively. Interestingly, WBCs and plasma profiles were more similar to nasal swabs than serum, suggesting the use of coagulants can affect results. miR-125b-5p was frequently dysregulated across all sample types, while miR-127-3p and miR-151b were upregulated in nasal swabs, WBCs, and plasma but absent in serum. Furthermore, miR-590-3p was consistently downregulated in nasal swabs, WBCs, and serum but unreported in plasma. These findings highlight distinct miRNA expression patterns across sample types and underscore the potential of nasal swabs as biomarkers for COVID-19 therapeutic monitoring. Even though our study focused on nasal swabs, future studies comparing miRNA profiles from paired blood and nasal samples could enhance the reliability and clinical applicability of these biomarkers. Such comparisons may help determine whether specific miRNAs identified in nasal swabs also exhibit similar diagnostic potential in blood-based assays.

Comparative analysis of miRNA expression levels between our nasal swab (NS) samples and those obtained from various studies on blood. We examined the expression levels of fourteen identified miRNAs showing > 2-fold change in expression from our study in comparison to samples from blood, including WBC, plasma, and serum. Red boxes denote miRNAs that were upregulated, while green boxes denote those that were downregulated following COVID-19 infection. The miRNAs highlighted in blue showed the same expression profile in our nasal swab samples as those observed in the WBCs, plasma, or serum reported from other studies, while the miRNA in orange was the most consistently dysregulated miRNA reported in most studies listed here. This is contrary to the profile of serum miRNAs reported that were mostly dysregulated in the opposite manner; i.,e., upregulated in nasal swabs, but downregulated in serum. All the studies reported in this figure used RNAseq except the one in the last column reported by Li et al., 2022 that used RT-qPCR.

Understanding host responses to viral infection is crucial for managing patient health and predicting outcomes. Circulatory miRNAs have emerged as potential biomarkers for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection and assessing disease severity71. Combining miRNA expression with clinical markers may improve disease monitoring and prognosis. Our analysis revealed significant correlations between identified miRNAs and clinical parameters (Fig. 6). MiR-30c-5p and miR-5010-3p correlated with high urea and low GFR, indicating poor prognosis, while novel-miR-264-5p correlated with low CRP and high GFR, suggesting a good prognosis. These findings highlight the potential of miRNA-based markers combined with clinical data for improved patient assessment. While individual clinical markers such as ferritin, CRP, GFR, and urea demonstrated reasonable discriminatory ability, combining these clinical markers significantly enhanced diagnostic performance (AUC = 0.951, p = 0.002). Notably, the addition of selected miRNA biomarkers to the clinical parameters further improved diagnostic accuracy, achieving an impressive AUC of 0.982 (p < 0.0001). These findings highlight that miRNA expression profiles, when integrated with routine clinical data, could offer a highly sensitive and specific approach for identifying SARS-CoV-2 infection. This combinatorial strategy may overcome the limitations of using clinical markers alone and provide a more robust platform for early and precise diagnosis, particularly in cases where clinical symptoms are ambiguous or overlapping with other respiratory infections.

We also compared our results with eight studies analyzing miRNA profiles in nasopharyngeal samples48,49,50,51,82,83,84,85,86, and one in bronchial aspirates87. While no single miRNA was shared across all studies, several miRNAs, including miR-486-5p, let-7 family, miR-34b, miR-200 family, miR-21, and miR-27a-3p, appeared in multiple studies with similar or contrasting expression patterns (Table 6). Notably, miR-486-5p and miR-27-3p were common between a nasal swab and bronchial aspirate study but absent in other nasal swab studies. These findings highlight shared and unique miRNA dysregulation patterns in COVID-19 across different respiratory sample types. We could identify only one miRNA that was common to one published nasal swab study that had the same expression profile as we reported, miR-21. To the contrary, we identified three miRNAs (miR-378a-3p, miR-146-3p, and miR-30c-5p) that were identified in another study, but with opposing expression profile (Table 6). This inconsistency was not exclusive to the current analysis of nasopharyngeal samples, but was also observed in studies involving blood or serum samples (reviewed in71. Based on these observations, it is plausible that validated biomarkers in one study may not align with those in another conducted elsewhere, as factors such as ethnicity, gender, age, presence of comorbidities, medications, types of COVID-19 treatments & vaccines administered, and the strain of SARS-CoV-2, etc., could influence miRNA expression profiles in COVID-19 patients71,88.

It has been evident that SARS-CoV-2 infection alters host miRNA expression, impacting biological functions and clinical outcomes71. It is widely recognized that miRNAs target genes within interconnected pathways rather than randomly across the transcriptome89. Our analysis identified miRNA-targeted genes involved in key signaling pathways, including FoXO, MAPK, PI3-Akt, prolactin, TGF-β, and chemokine activation (Table 6; Fig. 7). These pathways regulate essential cellular processes such as transcription, apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, morphogenesis, enzyme activity, and receptor functions, highlighting the critical role of miRNAs in COVID-19 pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. While bioinformatics predictions provide mechanistic insights, functional validation through RT-qPCR, luciferase assays, and knockdown experiments is warranted to confirm miRNA-mRNA interactions and their roles in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A majority of the miRNAs identified in this study (Table 5) have previously been linked to either host immune responses or oncogenesis. For instance, miR-146b-3p, which we and others have found to be dysregulated in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients72, has been associated with pro-inflammatory markers, such as IL-6 and IL-890,91. Inhibition of miR-146b-3p has been shown to result in a 49% reduction in IL-6 expression, making it a promising inflammatory marker91.

Another identified miRNA, miR-154-5p, known as a regulator of allergic inflammation, has been proposed as a potential marker in patients with endometriosis92,93. The upregulated miR-103a-5p in our study has been linked to T-cell activation in COVID-19 patients at rehabilitation stage and found to be upregulated in the plasma of COVID-19 patients72,80. Additionally, the upregulated miR-132-3p reported in our study is known to mediate anti-inflammatory effects by targeting acetylcholine and could impact processes like autophagy and calcium signaling94.

Three upregulated miRNAs—miR-1307-5p, miR-127-3p, and miR-30c-5p—are known to mediate host-viral responses and oncogenesis71. miR-1307 promotes NF-κβ/MAPK signaling, enhancing cell proliferation95. miR-127-3p downregulation over-activates type I IFN signaling, affecting transcription and antiviral defense96. Meanwhile, miR-30c-5p inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression and improves tamoxifen response in breast cancer97. Other upregulated miRNAs, including miR-365b-3p, miR-6887-3p, miR-5010-3p, and miR-335-3p, regulate apoptosis, MAPK/JAK/STAT signaling, and tumor development98,99. Another upregulated miRNA in our study, miR-18a-3p is linked to p53-mediated ceRNA networks, where its knockdown reduces tumor growth and promotes differentiation100.

Two of our identified miRNAs, miR-3663-5p and miR-202-5p, showed downregulation upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. MiR-3663-5p has previously been reported as dysregulated in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and may be linked to insulin signaling, metabolic regulation, and inflammation101. On the other hand, the downregulated miR-202-5p has been identified as an tumor suppressor and a potential diagnostic biomarker with reduced levels associated with cancer progression102. Overall, the potential outcomes of the markedly disrupted miRNAs observed in this study indicate that SARS-CoV-2 infection not only initiates a host immune response and inflammation, but also encourages tissue damage that could be associated with organ failure, and in the long term, even cancer103. Our study suggests that miRNA dysregulation might induce oncogenic responses by activating IL-6 and TNF-α, while also potentially inciting anti-tumor responses following infection, implying a multifaceted relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and the progression of cancer.

Beyond their prognostic value, the differentially expressed miRNAs identified in this study may offer therapeutic potential. The emergence of non-coding RNAs as promising candidates for therapeutic applications across infectious and non-infectious diseases is well established104,105,106,107,108,109,110. Restoring the expression of downregulated miRNAs like miR-202-5p could enhance antiviral defenses, while targeting upregulated miRNAs such as miR-146b-3p, miR-132-3p, miR-103a-5p, miR-127-3p, and miR-30c-5p could modulate immune and antiviral pathways in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. For instance, miRNA-132-3p, showing an upregulation in this study, has been shown to facilitate influenza A infection and enhance viral gene expression111,112. If miRNA-132-3p has a similar effect during COVID-19, downregulation of this miRNA could potentially be a valuable therapeutic target in COVID-19. Our findings thus suggest diverse roles of these miRNAs in host response and viral pathogenesis. Future mechanistic studies on their direct functional impact on SARS-CoV-2 could open avenues for promising RNA-based anti-COVID strategies, as has been seen in other diseases. For example, Liu et al.113 demonstrated that miR-146b-3p attenuates ARDS in septic mice by targeting and inhibiting the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thus reducing inflammation and tissue damage. Thus, future studies are needed to validate the therapeutic potential of the identified miRNAs, though currently, their strongest application remains in prognosis and disease monitoring.

Conclusions.

We have identified 14 known, 4 novel, and 4 previously-identified miRNAs with the potential to serve as biomarkers for COVID-19 infection, miRNAs that exhibit differential regulation following SARS-CoV-2 infection in nasal swab samples. This research is unique in its presentation of data from a diverse global cohort residing in the UAE, making these biomarkers more suitable to a wide range of ethnicities. Many of the miRNAs identified demonstrated promising potential for distinguishing individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 from uninfected individuals in combination with clinical parameters. Our results are consistent with previously reported data, and the newly discovered miRNAs in this study should be considered as promising candidates for future research. These biomarkers should also be valuable towards the rapid development of novel anti-virals and therapeutics against future variants-of-concern (VOC) that may emerge with pandemic potential.

Limitations and future directions

This study identifies important miRNA-based biomarkers for future studies; however, with certain limitations. For instance, sample size & quality, and potential confounders such as medications, vaccination status, and circulating viral variants could have influenced miRNA profiles and host responses. Furthermore, a longitudinal sampling design could have better captured the temporal changes in miRNA expression with disease progression along with an analysis of paired blood samples to determine systemic biomarker signatures. Therefore, future research should track miRNA dynamics across the acute, recovery, and post-COVID-19 phases to enhance biomarker relevance and correlate with disease severity. Future studies are also warranted with larger, stratified cohorts and detailed clinical metadata to refine biomarker reliability. Finally, while our findings highlight miRNAs with strong prognostic potential, it is important to distinguish their biomarker role from direct antiviral functions. Although prior studies, such as Haddad et al.114, suggest miRNAs may influence viral transmission, we did not directly assess such functional impacts. In short, our results lay a foundation for future functional investigations, with the immediate clinical utility of these miRNAs lying in prognosis and disease monitoring.

Data availability

The control and patient samples are being further analyzed for other biomolecules and hence not available. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the BioProject repository under accession number: PRJNA1049129 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1049129).

References

Celik, I. & Ozturk, R. From asymptomatic to critical illness: decoding various clinical stages of COVID-19. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 51 (SI-1), 3284–3300 (2021).

Hu, B. et al. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19 (3), 141–154 (2021).

Clerbaux, L. A. et al. Factors Modulating COVID-19: A Mechanistic Understanding Based on the Adverse Outcome Pathway Framework. J Clin Med, 11(15). (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Inflammatory pathways in COVID-19: Mechanism and therapeutic interventions. MedComm 2022. 3(3): p. e154. (2020).

Rabaan, A. A. et al. Diverse immunological factors influencing pathogenesis in patients with COVID-19: A review on viral dissemination, immunotherapeutic options to counter cytokine storm and inflammatory responses. Pathogens 10(5), 565 (2021).

Qudus, M. S. et al. The roles of critical pro-inflammatory cytokines in the drive of cytokine storm during SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Med. Virol. 95 (4), e28751 (2023).

Hojyo, S. et al. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm. Regen. 40, 37 (2020).

Farahani, M. et al. Molecular pathways involved in COVID-19 and potential pathway-based therapeutic targets. Biomed. Pharmacother. 145, 112420 (2022).

Wu, H. H. L. et al. COVID-19 and hepatorenal syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 28 (39), 5666–5678 (2022).

Fabiao, J. et al. Why do men have worse COVID-19-related outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis with sex adjusted for age. Braz J. Med. Biol. Res. 55, e11711 (2022).

Iannizzi, C. et al. Convalescent plasma for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5 (5), CD013600 (2023).

Kartsonaki, C. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of an international cohort of 600 000 hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Int. J. Epidemiol. 52 (2), 355–376 (2023).

Ahmad, W. & Shabbiri, K. Two years of SARS-CoV-2 infection (2019–2021): structural biology, vaccination, and current global situation. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 34 (1), 5 (2022).

Herbert, J. A. & Panagiotou, S. In Immune Response To Viruses. Encyclopedia of Infection and Immunity. Vol. 1 (ed. Rezaei, N.) 429-444 (Elsevier, 2022).

Moreno-Altamirano, M. M. B., Kolstoe, S. E. & Sanchez-Garcia, F. J. Virus control of cell metabolism for replication and evasion of host immune responses. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 95 (2019).

Adhya, D. & Basu, A. Epigenetic modulation of host: new insights into immune evasion by viruses. J. Biosci. 35 (4), 647–663 (2010).

Hilleman, M. R. Strategies and mechanisms for host and pathogen survival in acute and persistent viral infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101 (Suppl 2(Suppl 2), 14560–14566 (2004).

Gavriatopoulou, M. et al. Organ-specific manifestations of COVID-19 infection. Clin. Exp. Med. 20 (4), 493–506 (2020).

Ahmad, W. et al. Differentially-regulated MiRNAs in COVID-19: A systematic review. Rev. Med. Virol. 33(4), e2449 (2023).

Mathew, D. et al. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science 369(6508), eabc8511 (2020).

Battaglini, D. et al. Laboratory biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis in COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 13, 857573 (2022).

Samprathi, M. & Jayashree, M. Biomarkers in COVID-19: an Up-To-Date review. Front. Pediatr. 8, 607647 (2020).

Luo, S. et al. Exploring potential biomarkers and molecular mechanisms of ischemic cardiomyopathy and COVID-19 comorbidity based on bioinformatics and systems biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(7), 6511 (2023).

Su, B. et al. Potential application of MicroRNA profiling to the diagnosis and prognosis of HIV-1 infection. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3185 (2018).

Stanczyk, J. et al. Altered expression of MicroRNA in synovial fibroblasts and synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 58 (4), 1001–1009 (2008).

Andorfer, C. A. et al. MicroRNA signatures: clinical biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 17 (6), 313–319 (2011).

Huang, W. MicroRNAs: biomarkers, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Methods Mol. Biol. 1617, 57–67 (2017).

Leon-Icaza, S. A., Zeng, M. & Rosas-Taraco, A. G. MicroRNAs in viral acute respiratory infections: immune regulation, biomarkers, therapy, and vaccines. ExRNA 1 (1), 1 (2019).

Trobaugh, D. W. & Klimstra, W. B. MicroRNA regulation of RNA virus replication and pathogenesis. Trends Mol. Med. 23 (1), 80–93 (2017).

Takahashi, T., Heaton, S. M. & Parrish, N. F. Mammalian antiviral systems directed by small RNA. PLoS Pathog. 17 (12), e1010091 (2021).

Trobaugh, D. W. et al. RNA viruses can hijack vertebrate MicroRNAs to suppress innate immunity. Nature 506 (7487), 245–248 (2014).

Ostrycharz, E. & Hukowska-Szematowicz, B. Micro-Players of great Significance-Host MicroRNA signature in viral infections in humans and animals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(18), 10536 (2022).

Nguyen, T. H. et al. Potential role of MicroRNAs in the regulation of antiviral responses to influenza infection. Front. Immunol. 9, 1541 (2018).

Wong, R. R. et al. Role of MicroRNAs in antiviral responses to dengue infection. J. Biomed. Sci. 27 (1), 4 (2020).

Megahed, F. et al. MicroRNAs: small molecules with significant functions, particularly in the context of viral hepatitis B and C infection. Med. (Kaunas) 59(1), 173. (2023).

Shimakami, T. et al. Stabilization of hepatitis C virus RNA by an Ago2-miR-122 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 109 (3), 941–946 (2012).

Chinniah, R. et al. The effect of MiRNA gene regulation on HIV disease. Front. Genet. 13, 862642 (2022).

Balasubramaniam, M., Pandhare, J. & Dash, C. Are MicroRNAs important players in HIV-1 infection?? An update. Viruses 10(3), 110 (2018).

Diener, C., Keller, A. & Meese, E. Emerging concepts of MiRNA therapeutics: from cells to clinic. Trends Genet. 38 (6), 613–626 (2022).

Hombach, S. & Kretz, M. Non-coding rnas: classification, biology and functioning. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 937, 3–17 (2016).

Blakely, J. P. Guest editorial: changes in radiology training. Invest. Radiol. 8 (5), 357–359 (1973).

Dexheimer, P. J. & Cochella, L. MicroRNAs: from mechanism to organism. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 8, 409 (2020).

Skalsky, R. L. & Cullen, B. R. Viruses, micrornas, and host interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 123–141 (2010).

Benesova, S., Kubista, M. & Valihrach, L. Small RNA-Sequencing: approaches and considerations for MiRNA analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 11(6), 964 (2021).

MubarakAli, D. Comprehensive review on rapid diagnosis of new infection COVID-19. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 194 (3), 1390–1400 (2022).

Tarim, E. A. et al. Microfluidic-based virus detection methods for respiratory diseases. Emergent Mater. 4 (1), 143–168 (2021).

Pritchard, C. C., Cheng, H. H. & Tewari, M. MicroRNA profiling: approaches and considerations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13 (5), 358–369 (2012).

Eichmeier, A. et al. Conserved MicroRNAs in human nasopharynx tissue samples from swabs are differentially expressed in response to SARS-CoV-2. Genes (Basel) 13(2), 348 (2022).

Farr, R. J. et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection by MicroRNA profiling of the upper respiratory tract. PLoS One. 17 (4), e0265670 (2022).

Latini, A. et al. Expression analysis of MiRNA hsa-let7b-5p in naso-oropharyngeal swabs of COVID-19 patients supports its role in regulating ACE2 and DPP4 receptors. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 26 (19), 4940–4948 (2022).

McDonald, J. T. et al. Role of miR-2392 in driving SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell. Rep. 37 (3), 109839 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a mapreduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. Gigascience 7 (1), 1–6 (2018).

Wingett, S. W. & Andrews, S. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Res, 7: p. 1338. (2018).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9 (4), 357–359 (2012).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15 (12), 550 (2014).

Saeed, A. I. et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 34 (2), 374–378 (2003).

Chen, Y. & Wang, X. MiRDB: an online database for prediction of functional MicroRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 (D1), D127–D131 (2020).

McGeary, S. E. et al. The biochemical basis of MicroRNA targeting efficacy. Science 366(6472), eaav1741 (2019).

Tastsoglou, S. et al. DIANA-microT 2023: Including Predicted Targets of Virally Encoded miRNAs (Nucleic Acids Res, 2023).

Huang, H. Y. et al. MiRTarBase update 2022: an informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (D1), D222–D230 (2022).

Kehl, T. et al. MiRPathDB 2.0: a novel release of the MiRNA pathway dictionary database. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 (D1), D142–D147 (2020).

Das, S. S., Saha, P. & Chakravorty, N. miRwayDB: a database for experimentally validated microRNA-pathway associations in pathophysiological conditions. Database (Oxford), 2018. (2018).

Huang da, W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4 (1), 44–57 (2009).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1), D457–D462 (2016).

Griss, J. et al. ReactomeGSA - Efficient Multi-Omics comparative pathway analysis. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 19 (12), 2115–2125 (2020).

Coenye, T. Do results obtained with RNA-sequencing require independent verification? Biofilm 3, 100043 (2021).

Nahm, F. S. Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 75 (1), 25–36 (2022).

Unal, I. Defining an optimal Cut-Point value in ROC analysis: an alternative approach. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2017, 3762651 (2017).

Florkowski, C. M. Sensitivity, specificity, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves and likelihood ratios: communicating the performance of diagnostic tests. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 29 (Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S83–S87 (2008).

Araya, S. et al. Organ function biomarker abnormalities, associated factors and disease outcome among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Biomark. Med. 16 (6), 417–426 (2022).

Ahmad, W. et al. Differentially-regulated MiRNAs in COVID-19: A systematic review. Rev. Med. Virol. 33 (4), e2449 (2023).

Chen, Y. M. et al. Blood molecular markers associated with COVID-19 immunopathology and multi-organ damage. EMBO J. 39 (24), e105896 (2020).

Farr, R. J. et al. Altered MicroRNA expression in COVID-19 patients enables identification of SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS Pathog. 17 (7), e1009759 (2021).

Fernandez-Pato, A. et al. Plasma MiRNA profile at COVID-19 onset predicts severity status and mortality. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 11 (1), 676–688 (2022).

Garcia-Giralt, N. et al. Circulating MicroRNA profiling is altered in the acute respiratory distress syndrome related to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 6929 (2022).

Grehl, C. et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 derived small RNAs and changes in Circulating small RNAs associated with COVID-19. Viruses 13(8), 1593 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Differential MicroRNA expression in the peripheral blood from human patients with COVID-19. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 34 (10), e23590 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Potential predictive value of miR-125b-5p, miR-155-5p and their target genes in the course of COVID-19. Infect. Drug Resist. 15, 4079–4091 (2022).

Nicoletti, A. S. et al. Differentially expressed plasmatic MicroRNAs in Brazilian patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): preliminary results. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49 (7), 6931–6943 (2022).

Zheng, H. Y. et al. Longitudinal transcriptome analyses show robust T cell immunity during recovery from COVID-19. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 5 (1), 294 (2020).

Gutmann, C. et al. Association of cardiometabolic MicroRNAs with COVID-19 severity and mortality. Cardiovasc. Res. 118 (2), 461–474 (2022).

Tang, H. et al. The noncoding and coding transcriptional landscape of the peripheral immune response in patients with COVID-19. Clin. Transl Med. 10 (6), e200 (2020).

Zhao, Q. et al. Identification of a SARS-CoV-2 virus-encoded small non-coding RNA in association with the neurological disorders in COVID-19 patients. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7 (1), 107 (2022).

Soltane, R. et al. A comparative analysis of MicroRNA expression in mild, moderate, and severe COVID-19: insights from urine, serum, and nasopharyngeal samples. Biomolecules 13(12), 1681 (2023).

Garnier, N. et al. Altered MicroRNA expression in severe COVID-19: potential prognostic and pathophysiological role. Clin. Transl Med. 12 (6), e899 (2022).

Wu, W. et al. Changes of small Non-coding RNAs by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 821137 (2022).

Molinero, M. et al. Bronchial Aspirate-Based profiling identifies MicroRNA signatures associated with COVID-19 and fatal disease in critically ill patients. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 756517 (2021).

Jankovic, M. et al. MiRNAs as a potential biomarker in the COVID-19 infection and complications course, severity, and outcome. Diagnostics (Basel), 13(6), 1091 (2023).

Backes, C. et al. A dictionary on MicroRNAs and their putative target pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (13), 4476–4486 (2010).

Sheedy, F. J. & O’Neill, L. A. Adding fuel to fire: MicroRNAs as a new class of mediators of inflammation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67 (Suppl 3), iii50–iii55 (2008).

Pfeiffer, D. et al. miR-146a, miR-146b, and miR-155 increase expression of IL-6 and IL-8 and support HSP10 in an in vitro sepsis model. PLoS One. 12 (6), e0179850 (2017).

Kim, M. et al. MiR-154-5p-MCP1 axis regulates allergic inflammation by mediating cellular interactions. Front. Immunol. 12, 663726 (2021).

Pateisky, P. et al. hsa-miRNA-154-5p expression in plasma of endometriosis patients is a potential diagnostic marker for the disease. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 37 (4), 449–466 (2018).

Shaked, I. et al. MicroRNA-132 potentiates cholinergic anti-inflammatory signaling by targeting acetylcholinesterase. Immunity 31 (6), 965–973 (2009).

Du, X. et al. MiR-1307-5p targeting TRAF3 upregulates the MAPK/NF-kappaB pathway and promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation. Cancer Cell. Int. 20, 502 (2020).

Wu, L. et al. Downregulation of renal Hsa-miR-127-3p contributes to the overactivation of type I interferon signaling pathway in the kidney of lupus nephritis. Front. Immunol. 12, 747616 (2021).

Hu, S. et al. Identification of MicroRNA hsa-miR-30c-5p as an inhibitory factor in the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and investigation of its regulatory network via comprehensive analysis. Bioengineered 12 (1), 7165–7177 (2021).

Nie, J. et al. microRNA-365, down-regulated in colon cancer, inhibits cell cycle progression and promotes apoptosis of colon cancer cells by probably targeting Cyclin D1 and Bcl-2. Carcinogenesis 33 (1), 220–225 (2012).

Ye, L. et al. Functions and targets of miR-335 in cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 14, 3335–3349 (2021).

Hsu, T. I. et al. MicroRNA-18a is elevated in prostate cancer and promotes tumorigenesis through suppressing STK4 in vitro and in vivo. Oncogenesis 3 (4), e99 (2014).

Soronen, J. et al. Novel hepatic MicroRNAs upregulated in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Physiol. Rep. 4(1), e12661 (2016).

Ahmed, E. A., Rajendran, P. & Scherthan, H. The microRNA-202 as a diagnostic biomarker and a potential tumor suppressor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(11), 5870 (2022).

Costanzo, M., De Giglio, M. A. R. & Roviello, G. N. Deciphering the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(9), 7803 (2023).

Kimura, M. et al. MicroRNAs in infectious diseases: potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 36 (4), e0001523 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Non-coding RNAs expression in SARS-CoV-2 infection: pathogenesis, clinical significance, and therapeutic targets. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8 (1), 441 (2023).

Janga, H. et al. Non-coding RNA networks in infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2883, 53–77 (2025).

Tamgue, O. et al. Non-Coding RNAs in the etiology and control of major and neglected human tropical diseases. Front. Immunol. 12, 703936 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Comprehensive review for non-coding rnas: from mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 224, 116218 (2024).

Baptista, B. et al. Non-coding rnas: emerging from the discovery to therapeutic applications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 189, 114469 (2021).

Garbo, S. et al. Next RNA therapeutics: the mine of Non-Coding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(13), 7471 (2022).

Lagos, D. et al. miR-132 regulates antiviral innate immunity through suppression of the p300 transcriptional co-activator. Nat. Cell. Biol. 12 (5), 513–519 (2010).

Zhang, F. et al. MicroRNA-132-3p suppresses type I IFN response through targeting IRF1 to facilitate H1N1 influenza A virus infection. Biosci. Rep. 39(12), BSR20192769 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Up-regulation of miR-146b-3p protects septic mice with acute respiratory distress syndrome by inhibiting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J. Bioenerg Biomembr. 52 (4), 229–236 (2020).

Haddad, H. & Walid, A. Z. MiRNA target prediction might explain the reduced transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in jordan, middle East. Noncoding RNA Res. 5 (3), 135–143 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are truly grateful to the staff and patients of Rashid Hospital, Dubai and the College of Medicine & Health Sciences, UAE University (CMHS, UAEU) for the donation of samples and medical records to conduct the study. Without this generosity of spirit, this study would not have been possible. Special thanks go to Mr. Shiraz Anjum & Mr. Sam Daniel at the Al Jalila Children’s Specialty Hospital for help with sample collection and processing, and Ms. Ekhlass Mohammed of the Department of Pediatrics, CMHS, UAEU for help in taking samples from the control individuals at CMHS, UAEU. WA & FM contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This project was funded by the Al Jalila Foundation (AJF2020006), Dubai, UAE and in part from funds from the Abu Dhabi Department of Education and Knowledge (ADEK) ASPIRE Grant (AARE20-344) and by ASPIRE, the technology program management pillar of Abu Dhabi’s Advanced Technology Research Council (ATRC), via the ASPIRE “Abu Dhabi Precision Medicine ARI” (VRI-20-10).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions