Abstract

The growing reliance on Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) communication has heightened the vulnerability of Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) systems to cybersecurity threats, such as manipulation or forgery of V2V messages. This paper investigates the impact of three types of false information injection (FII) on vehicle collision risk and driving efficiency. To address these vulnerabilities, we develop a novel machine learning-based onboard model, ACC anomaly Detection and Mitigation (ACCDM), designed to strengthen ACC resilience against such cyberattacks. ACCDM continuously monitors vehicle parameters under benign conditions, detecting deviations that indicate potential threats and deploying real-time mitigations to maintain safety and efficiency. Simulations across continuous and clustered attack scenarios validate ACCDM’s accuracy in detecting cybersecurity threats, preserving safe following distances, and mitigating the negative impacts of cyberattacks on ACC systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivation

In recent years, the integration of advanced electronics and software in automotive systems has significantly enhanced Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) capabilities, making it essential for vehicle automation by maintaining safe following distances and adjusting speed1,2. However, as ACC increasingly relies on Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communications, including Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V), Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I). and Vehicle-to-Internet of Things(V2IoT)3,4,5. It becomes more vulnerable to cybersecurity threats. Recent research indicates that cyberattacks can subtly manipulate control commands6, interfere with sensor measurements7,8, or block tampering with on-board network data9, leading to dangerous driving conditions. The expanding interconnectivity of vehicles increases the attack surface, making it easier for adversaries to exploit vulnerabilities in communication10,11,12. Despite these concerns, the majority of current research predominantly focuses on utilizing historical data to detect cyberattacks or evaluate their potential impacts, such as on traffic flow and safety, while paying little attention to utilizing machine learning methods for cyberattacks detection and mitigation in real time. This lack of focus on anomaly detection and real-time defense mechanisms leaves ACC systems exposed to sophisticated and evolving cybersecurity threats. Therefore, it is imperative to develop efficient strategies for detecting and mitigating these risks.

To address this gap, this paper presents a novel machine learning-based model for detecting anomalies and mitigating potential cybersecurity threats in ACC systems. Specifically, the proposed model employs machine learning techniques to develop onboard predictive models that estimate the expected response of a following vehicle under benign V2V communication conditions. By utilizing these predictive models, ACC systems can detect anomalies in vehicle responses that are indicative of potentially malicious communications. This approach enables the identification of deviations from normal behavior, thereby enhancing the detection of cybersecurity threats within the ACC system. This work contributes to the field of secure Connected and Autonomous vehicle (CAV) technology by providing an innovative and timely solution to bolster the reliability of ACC systems in the face of increasing cyberattack threats.

Literature review

With the development of CAV technology, vehicles can maintain high driving efficiency through network communication. However, the open and shared network environment makes vehicles vulnerable to malicious attacks. Recently, numerous high-profile studies have highlighted the potential for sophisticated security breaches in automotive systems13,14,15,16,17,18. Wang categorize cyberattacks into two types based on their security relevance: safety-related and non-safety-related attacks19. The former mainly concerns vehicle incidents, such as traffic accidents, while the latter focuses on driving privacy, such as the leakage of personal information. To illustrate the potential risks of these attacks, Cui classifies cyberattacks into various forms, including false information injection (FII), denial of service (DoS), spoofing, eavesdropping, message suspension, and hardware tampering20. He proposed a simulation platform for evaluating cooperative adaptive cruise control under cyberattacks, which reveals that FII has the greatest impact on traffic and significantly increases the risk of collision through simulation results. Various techniques have been proposed to detect malicious vehicular nodes disseminating FII in vehicular ad-hoc networks (VANETs). For example, Ganesan et al. developed an anomaly detection technique leveraging the redundancy and correlation among measurements from heterogeneous sensors and vehicular communications21. However, such redundancy may not be feasible in emerging CAVs due to limitations in sensor technology and associated costs. Additionally, Chowdhury et al. developed an unsupervised anomaly detection method using multi-source sensor data from heterogeneous autonomous systems22. It employs dimensionality reduction and clustering to identify anomalies. However, this method may suffer from high false positives, sensitivity to data quality, and detection delays in collaborative scenarios, impacting real-time performance.

Machine learning-based anomaly detection has been widely applied to various automotive security challenges. For instance, Taylor et al. detect anomalies in Controller Area Network (CAN) bus attacks by analyzing historical packet timing data23, while Narayanan et al. propose an anomaly detection system using hidden Markov model to secure in-vehicle networks24. Given that ACC serves as the foundation for numerous CAV applications, considerable attention has been focused on enhancing the security of ACC systems. Ju et al. provide a comprehensive review of attack detection methods and resilience techniques in CAVs25. He explores the effects of various types of attacks, including network intrusions and sensor anomalies, on vehicle dynamics and control, and presents strategies for anomaly detection using advanced machine learning algorithms. Wang et al. developed a general framework for modeling and synthesizing two types of cyberattacks on ACC vehicles: direct attacks on vehicle control commands and FII attacks on sensor measurements26 The data after the simulation can be used to effectively identify where the FII attacks occurs. In ACC systems, attacks may also target onboard sensors such as radar. Physical attacks can result in sudden acceleration or deceleration, leading to traffic congestion and increased energy consumption. Li et al. investigated the energy consumption of FII attacks on different traffic conditions involving free flowing and congested states, and analyzed the sensitivity of traffic flows to these cyberattacks9.

The literature review reveals that FII is the most prevalent type of attack encountered in the context of cyber threats. While existing studies have employed machine learning methods to identify FII cyberattacks, they primarily focus on post-event detection, often relying on historical data, sensor redundancy, or network consensus. These approaches, while valuable, exhibit limitations in real-time application due to their reliance on specific environmental conditions (e.g., sensor availability, data quality) or their tendency to generate high false positives. Additionally, many existing models lack the agility to adapt to complex, evolving threats in network-based ACC systems. In particular, the real-time identification of cyberattacks and linking attack detection with effective mitigation strategies remains underexplored, leaving ACC systems vulnerable to sophisticated and time-sensitive threats. To address these challenges, we propose ACC anomaly Detection and Mitigation (ACCDM) model, which is for real-time anomaly detection and mitigation to protect ACC systems from cyberattacks. The cornerstone of ACCDM is its machine learning-based prediction model, trained on benign data patterns under normal operating conditions, enabling the detection of deviations that may indicate malicious activity. ACCDM consists of two key components: (1) an onboard architecture for real-time anomaly detection and mitigation, and (2) an offline cloud-based infrastructure that refines prediction models based on extensive data from various driving scenarios. This dual-component structure ensures that ACCDM is robust, adaptable, and capable of maintaining the safety and functionality of ACC systems across evolving threat landscapes.

Novelty of this contribution

In this paper, we develop a novel machine learning-based model for anomaly detection and real-time mitigation within Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) systems. This model is designed to strengthen ACC systems against cyberattacks involving false information injection, thereby enhancing both the security and operational efficiency of ACC functionalities. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents a significant step forward in applying machine learning to address the real-time detection and mitigation of abnormal behavior in ACC systems. This model can be easily implemented in CAVs equipped with V2V communication technology. The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

Constructing three types of false information injection attacks (including sine wave, linearly increasing, and constant value methods) and investigating their impact on collision risk and vehicle following efficiency in ACC systems under both clustered and continuous attack scenarios.

-

(2)

Assessing the effectiveness of the proposed anomaly detection and mitigation model in reducing collision risk and improving following efficiency under three distinct types of false information injection attacks. The results demonstrate that the model offers significant advantages in terms of safety and vehicle following efficiency.

-

(3)

Implementing and validating the robustness of the proposed model in various simulated cyberattack scenarios, showing its effectiveness in maintaining ACC system performance and security. The model’s adaptability to varying attack intensities highlights its potential for deployment in CAVs equipped with V2V technology.

Paper organization

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the detailed modeling methodology of ACCDM. Section 3 presents the performance of ACCDM under different FII cyberattacks. Finally, Sect. 4 presents the conclusion and outlook.

Methodology

The methodology for developing the ACC anomaly Detection and Mitigation (ACCDM) model is divided into three parts: (i) Vehicle’s following models in traffic; (ii) ACC anomaly Detection and Mitigation model; and (iii) Simulation setup and evaluation metrics. The specific details are as follows.

Vehicle following model

Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) and Intelligent Driver Model (IDM) are two advanced models designed for vehicle following in traffic, enabling vehicles to maintain a safe distance from the preceding vehicle. By utilizing a combination of Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC), V2V communication and other sensors, the ego vehicle can acquire the preceding vehicle’s speed and inter-vehicle spacing, allowing it to adjust speed and acceleration. In this paper, we assume that after the ACC system downgrades, the vehicle defaults to using IDM for control. Both the ACC and IDM systems rely on V2V communication to obtain the preceding vehicle’s speed information and use radar/lidar sensors to calculate the spacing between vehicles.

Figure 1 illustrates the following mechanism of ACC model. ACC is a fundamental technology that enables the ego vehicle \(\varepsilon\) to autonomously adjust its speed \({v_\varepsilon }\) to follow the preceding vehicle p. To achieve this goal, \(\varepsilon\) uses data from radar/lidar sensors to measure the inter-vehicle spacing s and V2V communication to obtain p’s velocity \({v_p}\), ensuring that \(\varepsilon\) takes at least \({T_{gap}}\) seconds to reach the position currently occupied by. IDM serves as a theoretical model that mimics human driving behavior to gauge the speed and inter-vehicle spacing of p in a similar way to ACC. IDM can act as a reliable backup by simulating human-like responses to maintain safety and control under compromised conditions. Equations (1) and (2) represent the controller operation for computing the desired acceleration under ACC and IDM, respectively. \({k_1}\) and \({k_2}\) are position and velocity constants, \({s_0}\) is the static minimum spacing of the vehicle and its value is set to 0.

The relevant terms of equations above (and in the rest of the paper) are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2 shows the following behavior of a two-vehicle scenario, where the leading vehicle’s motion is followed by either an ACC or IDM vehicle. The leading vehicle’s speed is modulated through various maneuvers, including acceleration, cruising, and deceleration, providing a comprehensive view of the following performance of both ACC and IDM systems. In Fig. 2(a), ACC shows minimal response delay, quickly aligning its speed with the leading vehicle, while the IDM adjusts more gradually, reflecting a smoother, human-like following behavior. Figure 2(b) reveals that ACC has more frequent changes in acceleration, in order to maintain a consistent following distance, whereas IDM demonstrates slower, more conservative acceleration adjustments. In Fig. 2(c), the ACC system maintains a smaller, more consistent following distance, while IDM keeps a larger, variable gap, enhancing safety by emulating cautious driving. Overall, the ACC system prioritizes rapid, efficient responses, whereas the IDM model emphasizes conservative, safety-oriented behavior, highlighting the advantages of ACC in dynamic driving scenarios.

ACCDM model

The ACCDM model provides onboard services for the ego vehicle \(\varepsilon\). ACCDM collects \(\varepsilon\)‘s operational data and uploads it to a trusted cloud server to refine a machine learning (ML) model. The model is periodically updated when \(\varepsilon\) is connected to a secure network, such as when stationary at the owner’s residence. During driving, if \(\varepsilon\) activates ACC, the system detects and mitigates V2V communication anomalies, emphasizing real-time resilience. Unlike other ML-based anomaly detection systems, ACCDM decouples the training of the ML model from on-road prediction tasks, addressing resource constraints and real-time requirements.

Figure 3 illustrates the architecture of the ACCDM model. It comprises a cloud component for offline model training and an onboard infrastructure designed for real-time mitigation. Different from other ACC implementations, ACCDM incorporates three critical components: (1) Cloud Component, (2) Anomaly Detector, and (3) Mitigator. The Cloud Component consists of a Data Collector and Model Training module. The Data Collector gathers only normal behavioral data for the system to learn through Model Training, thereby capturing responses to benign V2V communication patterns. The onboard Anomaly Detector then measures deviations from the nominal model to assess anomalies and fine-tunes the detection thresholds to capture minor anomalies that could potentially affect vehicle safety or efficiency. Upon detecting an anomaly, the Mitigator computes an alternative response, overrides the ACC controller if necessary, and conducts a plausibility check to ensure vehicle safety is not compromised, even under potentially adversarial conditions, thus maintaining real-time safety and efficiency. This approach ensures robust defense against detection subversion attacks, so that even if an adversary attempts to undermine the system covertly, the vehicle remains unaffected. The threat model assumes that an attacker can tamper with any V2V messages, including modifying, discarding, impersonating, or fabricating communications from other vehicles or infrastructure entities.

The specific algorithms for implementing ACCDM are detailed in Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2. In Algorithm 1, the Predictor is an offline-trained machine learning model that utilizes the same input parameters as the acceleration calculator (e.g., \({v_p},{v_\varepsilon },s\)). It outputs the predicted acceleration value, denoted as \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{pred}}\), while the Acceleration Calculator produces the corresponding result \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{ACC'}}\). Comparator calculates the deviation between the predicted value \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{pred}}\)and \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{ACC'}}\); If the deviation exceeds a predefined threshold, the anomaly is detected. When an anomaly is detected and V2V communication is disrupted, the Mitigator module intervenes, modifying the vehicle’s final acceleration \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{}}\) to maintain safety and efficency. After mitigation, the Power Control module recalculates the appropriate throttle or brake inputs to ensure stable driving dynamics. Simultaneously, the Data Collector logs relevant real-time data, which is later used for further offline model refinement, enhancing the system’s adaptability and resilience in future scenarios.

Algorithm 1 ACCDM

In Algorithm 2, if neither an anomaly is detected nor V2V communication is lost, the system operates in standard ACC mode, and the acceleration output is \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{ACC'}}\). Otherwise, the V2V communication device increases the sampling frequency to the maximum capacity (typically 100 ~ 200 Hz)29 to more accurately track the change in the position of the preceding vehicle and calculate its velocity \(v_{p}^{{\hbox{max} }}\). It is fed into the Acceleration Calculator to compute the adjusted acceleration \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{ACC}}\). Simultaneously, the Estimator is also a pre-trained machine learning model like the Predictor, computes the estimated acceleration \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{est}}\). However, unlike the Predictor, the Estimator only uses sensory inputs, such as the ego vehicle’s velocity \({v_\varepsilon }\) and spacing s. The Plausibility then validates the estimated acceleration by considering five parameters to calculate the time headway (THW). Based on THW, Plausibility ensures that the response estimator’s output does not compromise the safety or following efficiency of the ego vehicle \(\varepsilon\) even in the presence of potential adversarial interference. This multi-layered process ensures that the vehicle maintains safe operations under abnormal or attack conditions.

Algorithm 2 Mitigation

Simulation setup and evaluation metrics

This section consists of the following 3 steps, i.e., (1) Data generation; (2) Machine learning model selection; and (3) Evaluation metrics.

Data generation

The key challenge in evaluating ACCDM is to develop a comprehensive strategy to assess various attack types. Previous studies typically focus on specific false information injection (FII) cyberattack scenarios, for instance, Biron et al. focused on interference and flood attacks30, while Jagielski et al. focused on specific mutation attacks31. Section 2.1 explains that ACC systems obtain the preceding vehicle’s speed via V2V communication. To investigate the impact of FII on ACC performance, we employ various methods to generate and inject falsified speed data, simulating potential cyberattacks: (1) mutating existing messages, (2) forging new messages, and (3) blocking message delivery. Since the message payload includes the speed information of the preceding vehicle, an attack could lead to (1) underreporting of the speed information of the preceding vehicle, which reduces ego vehicle’s efficiency; (2) exaggerating the speed information of the preceding vehicle, which leads to unnecessary acceleration of the ego vehicle and increases the risk of collision; or (3) abrupt and random changes in the actual values, which results in erratic follow through. Positive deviations are categorized as collision attacks, while negative deviations are considered efficiency reducing attacks. We consider three different methods for generating false speed information with the following expressions.

Where \({v_{fake}}\) refers to malicious speed of preceding vehicle obtained through the V2V communication, and \({v_{true}}\) represents true speed. b, c are constants and t denotes time.

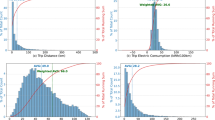

One of the primary evaluation objectives of this paper is to evaluate the effectiveness of ACCDM in diverse and realistic driving environments. We utilize real speed data from the High-D dataset32, which includes trajectory information from actual vehicles on German motorways. The dataset comprises approximately 110,500 samples, covering a total driving distance of about 44,500 km, collected at a frequency of 25 Hz. The dataset underwent a data filtering process to exclude entries with traveling times shorter than 400 frames. This refinement led to a final sample size comprising 18,844 samples. This data provides the trajectory of the leading vehicle, while the trajectory of the ego vehicle is computed using Eq. (1). We aggregated data from all scenarios to form a global dataset, which was subsequently divided into training and test sets in an 80 − 20 ratio.

Machine learning model

The feasibility of ACCDM depends heavily on the ability of the machine learning components to accurately identify anomalous messages and mitigate their adverse effects. The machine learning components, namely the Predictor and Response Estimator, are designed to accurately detect anomalous communications and mitigate adverse effects. The machine learning regression problem for these components can be framed in two ways: (i) stateless prediction and (ii) time-series prediction. The ML model must meet two critical requirements: (1) avoiding false positives on benign messages, and (2) accurately classifying malicious messages as anomalous. Additionally, it must generate real-time predictions within the computational and storage constraints of the vehicle system.

Here we considered four candidate architectures: Random Forest regressors (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN), and Time Delayed Neural Networks (TDNN). These specific algorithms were chosen due to their demonstrated effectiveness in anomaly detection and their compatibility with the computational limitations of automotive systems33. RF effectively handles high-dimensional data and complex feature interactions via ensemble learning. SVM, with strong theoretical foundations, provide robust performance across various datasets. FNN stand out for their ability to model highly non-linear relationships in vehicle data, offering customizable architectures that can remain lightweight for real-time anomaly detection in automotive systems. By enabling adjustable layer depth, FNN can be tailored to balance detection accuracy with minimal computational overhead, an essential requirement in resource-constrained automotive environments. Additionally, FNN solutions typically maintain enough interpretability to facilitate system validation and compliance with safety regulations, a critical factor in the automotive industry. Finally, TDNN extend FNN by capturing temporal dependencies, making them particularly well-suited for sequential communication signals. Architectures more complex than TDNN were deemed unnecessarily complicated given the constraints of the automotive system, as they introduce additional computational overhead without sufficient performance benefits under these conditions.

The relevant parameters for each machine learning model are shown in Table 2 below.

Evaluation metrics

The prediction performance of ACCDM is highly reliant on the selection of anomaly detection thresholds. According to Algorithm 1, we assign anomaly_flag by comparing the difference between \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{pred}}\) under machine learning and \(a_{\varepsilon }^{{ACC'}}\) obtained from the onboard Accelerator Calculator. Setting the threshold too high can diminish detection accuracy, while setting it too low may result in an increase in false positives. A high rate of false alarms could trigger frequent and unnecessary invocations of the reasonableness checker in ACCDM. Although the computational cost of the reasonableness checker is minimal, the cumulative overhead could become substantial, particularly since vehicles typically operate under benign conditions. Thus, selecting the optimal threshold is essential to ensuring both safety and efficiency in adversarial situations, while keeping performance overhead to a minimum during normal operation. We use four detection metrics: R (Recall), P (Precision), F1-score and FPR (False Positive rate) to estimate the quality of resilience under attack33. The formulas for these parameters are as follows.

Where TP represents true positives (correctly detected anomalies), FN denotes false negatives (anomalies that were missed), FP refers to false positives (incorrectly classified normal instances as anomalies), and TN indicates true negatives (correctly classified normal instances).

Results and discussion

This section begins with the selection of the optimal machine learning algorithm. The evaluation is based on the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the predicted values and the ground truth acceleration values, with a smaller error indicating a better prediction. As discussed before, we consider the cyberattacks in the form of false information injection (FII), and take four machine learning architectures as candidates: RF, SVM, FNN, and TDNN. The accuracy of these algorithms at different thresholds is subsequently analyzed. Finally, the resilience of ACCDM under various scenarios is examined, along with the calculation of collision risk and efficiency degradation under a naive ACC system.

Determination of machine learning models and thresholds

Figure 4 shows the prediction results of RF, SVM, TDNN and FNN in benign condition for a specific sample. The RF model in Fig. 4(a) struggles to capture small fluctuations and often flattens areas with rapid changes, which will limit its effectiveness in detecting anomalies. The SVM model in Fig. 4(b) generally follows the trend of the ground truth but exhibits significant deviations in the deceleration region. The predictions produced by the TDNN model in Fig. 4(c) are closely aligned with the ground truth trends for all frames, yielding smoother results, yet it fails to capture motion details in dynamic changes and exhibits larger errors. In contrast, the FNN model in Fig. 4(d) delivers the most accurate results, consistently matching the ground truth with minimal discrepancies. Overall, FNN outperforms all other models, followed by SVM, both significantly surpassing RF and TDNN in accuracy and their ability to track small changes in acceleration.

To clearly highlight the differences in the prediction performance among the four machine learning methods, we employed the RMSE to quantify the discrepancy between the predicted and actual values. The results, shown in Table 3, indicate that the FNN model has the lowest RMSE, demonstrating it to be the most accurate and closest to the actual values.

Figure 5 illustrates the Line graph of four metrics under clustered sinusoidal attacks, which corrupts approximately 25% of the V2V messages. This attack is representative as it incorporates features of both clustered and continuous attacks, combining positive and negative biases within the same attack instance. In Fig. 5(a), The FNN model consistently achieves the highest recall across all thresholds, demonstrating its strong ability to detect most anomalies and minimize missed detections (false negatives). As the threshold increases from 0.05 to 0.4, the recall for all models gradually decreases. In terms of precision, as shown in Fig. 5(b), FNN maintains superior performance, especially at lower thresholds, with significantly higher precision than the other models. This indicates that FNN effectively captures anomalies while minimizing false alarms, which is crucial for maintaining operational efficiency in benign conditions. The F1 scores in Fig. 5(c) further confirm FNN’s superiority, consistently achieving the highest values and providing an optimal balance between recall and precision. This underscores the robustness of FNN in ACCDM anomaly detection. In Fig. 5(d), FNN consistently shows a low FPR across different thresholds, outperforming models such as SVM, RF and TDNN. This suggests that FNN reliably reduces unwanted false positives.

Overall, these results indicate that FNN delivers the highest prediction quality and is the optimal model for ACCDM. After evaluating different thresholds, 0.15 was selected as the optimal threshold, providing the best balance between detection accuracy and operational efficiency.

ACCDM resilience under sinusoidal FII attacks

This section discusses the resilience of ACCDM under sinusoidal FII attacks, and the simulation results under a certain sample are shown in Fig. 6. The left image depicts a clustered attack affecting 25% of the total frames, while the right image shows a continuous attack impacting 80%.

In Fig. 6(a) and (b), the true speed (blue line) is altered by the malicious input (orange dashed line), simulating spurious V2V speed communication attacks. In Fig. 6(c) and (d), the naïve ACC system fails to distinguish between real and fake data affected by FII, resulting in significant velocity fluctuations clearly depicted by the orange dashed lines. However, ACCDM successfully detects and mitigates these malicious alterations, maintaining a velocity profile (green line) that closely aligns with the benign conditions (blue line). Similarly, in Fig. 6(e) and (f), the results of time headway (THW) are compared. The naïve ACC system shows large fluctuations in THW under attacks (orange line), which could compromise safety by increasing collision risks or resulting in overly cautious driving. In contrast, ACCDM maintains a stable and safe THW (green line), closely matching the benign THW (blue line). Although the THW occasionally falls slightly below the benign conditions under continuous attacks, vehicle safety remains uncompromised. This further demonstrating its robustness in handling FII attacks.

To fully assess the performance of ACCDM, we analyzed the THW under both clustered attacks (impacting 25% of frames) and continuous attacks (impacting 80% of frames), as summarized in Table 4. We considered a threshold of THW < 1.15 s to indicate collision risk and THW > 1.25 s to denote efficiency degradation. Under the clustered FII attack scenario, none of the models, including ACCDM, exhibited instances of THW < 1.15, indicating no collision risks. However, Degrade IDM and Naïve ACC show a minor increase in THW > 1.25, reflecting a slight loss in efficiency, while ACCDM maintains optimal performance without exceeding this threshold. In the continuous attack scenario, Naïve ACC displays significant vulnerabilities, with 13.68% of cases falling below the THW < 1.15 threshold, indicating collision risks. Additionally, Naïve ACC exceeds the THW > 1.25 threshold in 14.01% of cases, whereas IDM exceeds this threshold in 84.63% of cases, indicating a significant efficiency loss. In contrast, ACCDM exhibits 0% in both collision risk and efficiency loss, proving its ability to maintain safety and operational effectiveness under sinusoidal FII attack conditions. These results underscore ACCDM’s superior resilience and adaptability in mitigating both collision risks and efficiency degradation compared to the other models.

ACCDM resilience under positive bias FII attacks

Figure 7 illustrates the resilience of ACCDM under positive bias FII attacks, with the left image depicting clustered attacks over 25% of the total frames, and the right image showing continuous attacks covering 80% of the frames.

In Fig. 7(a), the malicious input (orange dashed line) is clustered and exhibits increasing values over time, which in Fig. 7(b) remains constantly greater than the ground truth. In Fig. 7(c), the clustered and increasing malicious inputs cause the Naive ACC’s speed to oscillate around the true value. This indicates that the ego vehicle experiences sudden acceleration, followed by immediate deceleration once the attacks cease. This is due to the Naïve ACC attempts to accelerate and thus maintain a constant THW when the preceding vehicle’s fake speed increases. However, since the inter-vehicle spacing from sensors remains unaffected by the FII attacks, the vehicle’s acceleration is limited. Consequently, when the FII is no longer present, the vehicle quickly decelerates nearby the ground truth. In Fig. 7(d), the naïve ACC system (orange dashed line) displays significant acceleration early during continuous attacks. Interestingly, the vehicle later decelerates back toward the true speed. This behavior occurs because the naïve ACC system initially accelerates sharply to maintain a fixed headway during the positive bias attack. As a result, the headway decreases significantly, triggering a sharp deceleration to ensure driving safety. When the FII attacks ends, the inter-vehicle distance becomes too small, prompting the vehicle to decelerate abruptly to restore a safe speed before gradually accelerating again. In contrast, the performance of ACCDM (green line) remains consistently aligned with the benign speed (blue line), indicating that ACCDM effectively minimizes the speed oscillations caused by the attack. Figure 7(e) and (f) depict the impact of FII on THW. Under attacks, the naïve ACC system experiences excessive THW fluctuations (orange line), which can pose safety risks, such as an increased likelihood of collisions or overly cautious driving. However, the ACCDM system maintains a stable THW (green line), closely matching the benign condition (blue line).

Table 5 presents the THW under positive bias FII attacks. One can see that the THW less than 1.15 s occurs exclusively in the Naïve ACC system, and THW greater than 1.25 s is only observed in the degraded IDM. This indicates that the risk of vehicle collision and efficiency reduction under positive bias cluster attacks is minimal. In contrast, in the continuous attack scenario, Naïve ACC demonstrates significant vulnerabilities, with 71.37% of cases falling below the THW < 1.15, indicating a lot of collision risks, and 71.42% of cases in degrade IDM exceeding the THW > 1.25, reflecting substantial efficiency loss. In contrast, ACCDM maintains 0% for both collision risk and efficiency loss. These results suggest that ACCDM is highly resilient in mitigating safety risks and operational inefficiencies under attack conditions, outperforming the other models, especially Naïve ACC.

ACCDM resilience under negative bias FII attacks

This section discusses the resilience of ACCDM under negative bias FII attacks, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The left image depicts a clustered attack affecting 25% of the total frames, while the right image shows a continuous attack impacting 80%.

Similar to the results discussed in Figs. 7 and 8 illustrates the impact of negative bias FII attacks on ACCDM and Naïve ACC under both clustered and continuous attack scenarios. During clustered attacks (see Fig. 8(a), (c) and (e)), the malicious inputs show a gradual decrease, causing Naïve ACC to experience velocity fluctuations and sudden decelerations as it tries to maintain a safe following distance. During continuous attacks (see Fig. 8(b), (d) and (f)), Naïve ACC undergoes sharp decelerations early on, followed by a gradual return to the true speed. These fluctuations are evident in both velocity and THW measurements, reflecting the system’s inability to maintain stable control under attack. In contrast, ACCDM consistently mitigates the effects of both attack types, maintaining stable speeds and THW that closely match benign conditions. This demonstrates ACCDM’s resilience, as it prevents the excessive speed variations and headway fluctuations that could otherwise compromise safety, offering superior performance over Naïve ACC.

Table 6I presents the THW under negative bias FII attacks. Similar to the results discussed previously for positive bias, none of the models show THW < 1.15 in the clustered attack scenario, indicating no risk of collision. Only Degrade IDM and Naïve ACC slightly exceed the THW > 1.25 threshold in 0.26% and 0.37% of cases, respectively, while ACCDM and Ground truth maintain optimal performance without any efficiency loss. This suggests that the clustered attack has a minor effect on vehicle-following efficiency. In the continuous attack scenario, Degrade IDM and Naïve ACC demonstrate significant weaknesses. Degrade IDM records 2.88% of cases below THW < 1.15, indicating collision risk, while 71.42% of its cases exceed the THW > 1.25 threshold, reflecting considerable efficiency loss. Naïve ACC shows similar issues, with 0.01% of cases falling below THW < 1.15 and 71.06% exceeding the efficiency threshold. In contrast, ACCDM consistently maintains 0% in both collision risk and efficiency loss, demonstrating its strong ability to mitigate the adverse effects of negative bias attacks. These results highlight ACCDM’s superior resilience in preserving both safety and efficiency, particularly in contrast to the vulnerability of Naïve ACC under continuous attack conditions.

Conclusion

In summary, this research presents a novel machine learning-based ACC anomaly Detection and Mitigation (ACCDM) model, aimed at enhancing the security and robustness of ACC systems against cyberattacks based on false information injection. The proposed model effectively detects and mitigates three common types of false information injection attacks, including continuous and clustered attacks, which are common threats to V2V enabled ACC systems. The extensive simulations conducted in this study demonstrated that the ACCDM model achieved a 0% collision rate and no significant efficiency losses under various cyberattack scenarios, highlighting its robustness and effectiveness. In contrast, traditional Naïve ACC systems exhibited considerable vulnerabilities, including an increased risk of collisions and a substantial decline in performance when subjected to similar attacks. The practical significance of this research lies in its potential to greatly enhance vehicle safety and reliability in an increasingly interconnected driving environment. As CAV technologies continue to evolve, the ACCDM model offers a viable solution to mitigate the growing cybersecurity risks associated with V2V communication. By leveraging machine learning techniques, this work not only strengthens the resilience of ACC systems but also paves the way for the development of more secure and reliable autonomous driving technologies.

Nevertheless, the study acknowledges certain limitations, including dependence on accurate normal driving behavior data for model training and the lack of validation across diverse real-world scenarios. Future research could focus on integrating additional data sources to further enhance the robustness of the ACCDM framework. In addition, we plan to explore the integration of lightweight deep learning architectures, such as MobileNet, as well as model optimization techniques like pruning and knowledge distillation, to further improve detection accuracy, computational efficiency, and adaptability in resource-constrained vehicle environments. These efforts will ultimately contribute to the development of safer and more reliable autonomous driving systems.

Data availability

The High-D dataset used for the research described in the article is public available at https://levelxdata.com/highd-dataset.

Code availability

The custom code used to generate the results in this study is archived on Zenodo (version v1) under DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17089809. The files are accessible upon request via the DOI page. The archive includes source code, a minimal runnable sample, representative trained weights, and instructions for reproducing the figures.

References

Ohno Hiroshi. Analysis and modeling of human driving behaviors using adaptive cruise control [J]. Appl. Soft Comput., 1(3). 237–243. (2001).

Chen Xianda, Z. et al. Follownet: a comprehensive benchmark for car-following behavior modeling [J]. Sci. Data. 10 (1), 828–842 (2023).

Chun, C. M., Maode, M. & Zhijin, P. Attack models and countermeasures for autonomous vehicles [M]. Intelligent Technologies for Internet of Vehicles. Springer. : 375–401. (2021).

RS Ponmagal. An intelligent dynamic cyber physical system threat detection system for ensuring secured communication in 6G autonomous vehicle networks [J]. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20795–20815 (2024).

Kang, Y. & Yijun, C. Vehicle-to-vehicle cooperative driving model considering end-to-end delay of communication network [J]. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 22966–22976 (2023).

Li, T., Benjamin, R., Shian, W., Mingfeng, S. & Stern Raphael. Exploring energy impacts of cyberattacks on adaptive cruise control vehicles [C]; proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), pp: 1–6. (2023).

Petit Jonathan, S. & Steven, E. Potential cyberattacks on automated vehicles [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 16 (2), 546–556 (2014).

Adriana, B. Groza bogdan. Cyberattacks on adaptive cruise controls and emergency braking systems: adversary models, impact assessment, and countermeasures [J]. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 73 (2), 1216–1230 (2024).

Li Tianyi, W., Shian, S. & Mingfeng, S. Raphael. Can cyberattacks on adaptive cruise control vehicles be effectively detected? [C]; proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), pp: 323–328. (2024).

Singh, R. R., Chaminda, H. & Omprakash, K. Lloret jaime. In-vehicle communication cyber security: challenges and solutions [J]. Sensors 22 (17), 6679–6711 (2022).

Bendiab Gueltoum, H., Amina, G., Georgios, K., Nicholas, S. & Stavros Autonomous vehicles security: challenges and solutions using blockchain and artificial intelligence [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24 (4), 3614–3637 (2023).

Haicheng, T. & Yongxiang, X. Chen Xi. Vulnerability Analysis of Cyber Physical Systems Under the False Alarm Cyber Attacks [J]599127416–127424 (Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2022).

Zhou Zhi, L., Linheng, Q., Xu, R. & Bin An Autonomous Platoon Formation Strategy To Optimize CAV car-following Stability Under Periodic Disturbance [J]626129096–129120 (Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2023).

Wang Bohui, S. & Rong A distributed platoon control framework for connected automated vehicles in an urban traffic network [J]. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 9 (4), 1717–1730 (2022).

Wang Shunchao, L., Zhibin, W. & Bingtong, L. M. Collision avoidance motion planning for connected and automated vehicle platoon merging and splitting with a hybrid automaton architecture [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25 (2), 1445–1464 (2023).

Li Qianwen, C. & Zhiwei, L. A review of connected and automated vehicle platoon merging and splitting operations [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23 (12), 22790–22806 (2022).

Khattak Zulqarnain, H., Smith Brian, L. & Park Hyungjun Fontaine Michael D. Cooperative lane control application for fully connected and automated vehicles at multilane freeways [J]. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 111, 294–317 (2020).

Cheng Rongjun, J., Qun, Z., Yuchen, G. & Hongxia Analysis of the Impact of Cyberattacks on the Lane Changing Behavior of Connected Automated Vehicles [J]632129333–129350 (Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2023).

Wang, N. W. & Yueh-Min, H. Chen Wei-Ming. A novel secure communication scheme in vehicular ad hoc networks [J]. Comput. Commun. 31 (12), 2827–2837 (2008).

Lian, C., Jia, H., Brian, P. B. & Pavle, B. Development of a simulation platform for safety impact analysis considering vehicle dynamics, sensor errors, and communication latencies: assessing cooperative adaptive cruise control under cyber attack [J]. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 97, 1–22 (2018).

Ganesan Arun, R. & Jayanthi, S. Exploiting consistency among heterogeneous sensors for vehicle anomaly detection [J]. SAE Tech. Paper. 1654 (1), 1654–1659 (2017).

Shafayet, C. S. & Mejbaul, I. K. Noor Rouhan. Unsupervised abnormality detection using heterogeneous autonomous systems [J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006–03733, 1–6. (2020).

Taylor Adrian, J., Nathalie, L. & Sylvain Frequency-based anomaly detection for the automotive CAN bus [C]; proceedings of the 2015 World Congress on Industrial Control Systems Security (WCICSS), 2015, pp: 45 – 9.

Nair, N. S. & Sudip, M. Joshi Anupam. OBD_SecureAlert: An anomaly detection system for vehicles [C]; proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP), pp: 1–6. (2016).

Ju Zhiyang, Z. et al. A survey on attack detection and resilience for connected and automated vehicles: from vehicle dynamics and control perspective [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 7 (4), 815–837 (2022).

Wang Shian, S., Mingfeng, S. & Raphael Analytical characterization of cyberattacks on adaptive cruise control vehicles [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 12 (1), 1–12 (2024).

Milanés Vicente, Shladover Steven, E. Modeling cooperative and autonomous adaptive cruise control dynamic responses using experimental data [J]. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 48, 285–300 (2014).

Dihua, S., Yuchu, H. & Min, Z. Cooperative driving modelling in the vicinity of traffic signals based on intelligent driver model [J]. IET Intel. Transport Syst. 12 (10), 1236–1242 (2018).

Marchetti Mirco, S., Dario, G., Alessandro, C. & Michele Evaluation of anomaly detection for in-vehicle networks through information-theoretic algorithms [C]; proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd International Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry Leveraging a better tomorrow (RTSI), pp: 1–6. (2016).

Abdollahi, B. Z., Satadru, D. & Pierluigi, P. Real-time detection and Estimation of denial of service attack in connected vehicle systems [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 19 (12), 3893–3902 (2018).

Jagielski Matthew, J., Nicholas, L., Chung-Wei, N. R. & Cristina Shiraishi Shinichi. Threat detection for collaborative adaptive cruise control in connected cars [C]; proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th ACM conference on security & privacy in wireless and mobile networks, pp: 184-9. (2018).

Krajewski Robert, B., Julian, K., Laurent, E. & Lutz The highd dataset: A drone dataset of naturalistic vehicle trajectories on german highways for validation of highly automated driving systems [C]; proceedings of the. 21st international conference on intelligent transportation systems (ITSC), 2018, pp: 2118-25. (2018).

Boddupalli Srivalli, R. A., Someshwar & Ray Sandip. Resilient cooperative adaptive cruise control for autonomous vehicles using machine learning [J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23 (9), 15655–15672 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (No. 2108085MF205), Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (No. 2508085QF248), Science and Engineering Teachers’Job Placement Program in Enterprises (No. 2024jsqygz58), Young Scholars Overseas Visiting and Research Funding Project of Wannan Medical College (No. wyqnyx202009), Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province for College Scholar (No. 2024AH053451) and Quality Engineering Program of Anhui Province (No. 2022shsj025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yan-Tao Zhang: Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Li-Yang: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft. Hao-Zhang: Investigation, Validation. Nan-Wan:Data curation, Visualization. Zi-Wen Wu:Data curation, Visualization. Jie- Chen: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Jie-Chang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Yan-Tao Zhang and Li-Yang contributed equally to this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper entitled ‘‘Machine Learning-Based Detection and Mitigation of Cyberattacks in Adaptive Cruise Control Systems’’.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, YT., Yang, L., Zhang, H. et al. Machine learning-based detection and mitigation of cyberattacks in adaptive cruise control systems. Sci Rep 15, 36335 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20096-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20096-5