Abstract

In this study, a novel cascaded exponential proportional–integral–derivative (exp-PID) controller tuned by the starfish optimization algorithm (SFOA) is proposed for enhancing the transient and steady-state performance of nonlinear dynamic systems. The design objective is to achieve improved adaptability, robustness, and precision under varying operating conditions and external disturbances. The exponential PID structure introduces nonlinear modulation in the proportional and derivative components, enabling smoother control action and superior damping characteristics compared to conventional PID and fractional-order PID designs. The proposed SFOA-based exp-PID controller is validated on two benchmark systems: a DC motor speed control system and a three-tank liquid-level process. Across multiple independent trials, the controller achieved outstanding results, with the DC motor system attaining a rise time of 0.0039 s, settling time of 0.0083 s, and zero overshoot, while the three-tank system reached a rise time of 1.72 s, settling time of 2.47 s, overshoot of 1.5%, and steady-state error of 9.22 × 10⁻⁵%. Comparative analyses with recently developed algorithms (including the flood algorithm, greater cane rat algorithm, mantis search algorithm, and dandelion optimizer) as well as previously reported methods demonstrate the superior convergence behavior, stability, and accuracy of the proposed controller. Statistical evaluations further confirm the method’s robustness and consistent performance across repeated runs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In modern industrial systems, achieving precise and reliable control over dynamic processes such as direct current (DC) motor speed regulation and liquid-level control remains a significant challenge1. These systems often exhibit nonlinear behaviors, time-varying dynamics, and sensitivity to external disturbances. While the proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controller has been extensively adopted for its simplicity and satisfactory performance2, its fixed gains limit adaptability under changing operating conditions3. Consequently, conventional PID-based systems may experience instability, sluggish transient response, and poor disturbance rejection in dynamic environments4. These issues have motivated the development of intelligent and optimization-based tuning strategies capable of improving robustness and adaptability in real-time applications.

Among these, metaheuristic optimization techniques have proven highly effective for controller parameter tuning in nonlinear and uncertain systems. They provide efficient global search capabilities and avoid the limitations of classical gradient-based optimization. Recent studies have introduced several nature-inspired algorithms that emulate biological or physical behaviors to balance global exploration and local exploitation5,6,7,8,9. Although these algorithms have achieved promising results, their direct implementation in real-time control may be constrained by computational demands. Therefore, integrating metaheuristic optimization with adaptive control structures can enhance both efficiency and robustness in practical systems.

PID controllers remain the cornerstone of industrial control due to their simplicity and reliability10,11. However, their performance often deteriorates in nonlinear or time-varying systems. To address these limitations, several advanced variants have been proposed. The exponential PID (exp-PID) controller introduces nonlinear exponential terms in the proportional and derivative components, improving transient behavior and disturbance rejection12. The fractional-order PID (FOPID) controller extends the classical design through fractional calculus, providing more flexible tuning and better handling of system dynamics13,14,15. The optimal fractional-order time-delayed PID (optimal FOTID) controller further enhances robustness and precision in systems affected by delays and uncertainties16. These advanced PID designs demonstrate that effective performance relies strongly on intelligent tuning strategies17,18.

The optimization of control parameters has become essential in modern control engineering, especially in renewable energy and industrial automation systems such as photovoltaic (PV) plants and microgrids19,20,21. Many studies have demonstrated that metaheuristic-based tuning of advanced PID controllers can significantly improve transient response, steady-state accuracy, and disturbance rejection22,23,24. Similarly, intelligent and adaptive control schemes such as fuzzy logic control, active disturbance rejection control (ADRC), and model predictive control (MPC) have shown strong potential for regulating nonlinear systems like multi-tank processes25,26,27,28. Furthermore, hybrid approaches combining global metaheuristic search with local learning or refinement methods have been proposed to accelerate convergence and improve stability in complex systems29,30,31.

Building upon these research directions, this study proposes a novel control framework that integrates the starfish optimization algorithm (SFOA)5 with a cascaded exponential PID (exp-PID) controller. The SFOA is used to optimally tune the exp-PID parameters, including proportional, integral, derivative gains, and exponential modulation factors. This hybrid structure enhances adaptability and robustness, allowing the controller to maintain precise performance across varying operating conditions.

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed SFOA-based exp-PID controller, simulations were performed on two representative nonlinear processes: (i) a DC motor speed control system, and (ii) a three-tank liquid-level control system. Each system was tested under identical conditions using multiple objective functions and compared against several recent algorithms. The results demonstrated that the proposed controller achieves superior convergence behavior, minimal overshoot, and faster settling times, consistently outperforming other benchmarked methods. Moreover, statistical consistency across repeated runs confirmed its robustness and stability in handling stochastic search processes.

Although numerous studies have addressed PID optimization through metaheuristic algorithms, most focus primarily on classical or fractional PID structures without incorporating adaptive nonlinear transformations such as exponential or logarithmic functions. The limited exploration of nonlinear cascaded PID forms has restricted performance enhancement in systems exhibiting strong nonlinearity, actuator saturation, or load disturbances. Furthermore, the effectiveness of newly introduced optimizers such as SFOA in tuning multi-parameter nonlinear controllers has not yet been systematically investigated. These gaps highlight the necessity for an optimization framework that combines the nonlinear adaptability of exponential controllers with the global search efficiency of a recent, high-performing metaheuristic algorithm.

The main contributions and novelty of this study can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

A nonlinear control structure combining exponential error transformation and conventional PID regulation is formulated to achieve fast convergence, reduced overshoot, and high steady-state precision.

-

2.

The SFOA’s multidirectional arm-extension and adaptive regeneration principles are utilized to optimally tune the controller parameters, ensuring efficient global search and avoidance of local entrapment.

-

3.

Extensive experiments were performed using several recent optimization algorithms on both electromechanical and process-control systems. The proposed method consistently yielded the best transient and steady-state results, validating its robustness and adaptability.

-

4.

The controller was evaluated using multiple performance indices to confirm its generalization capability and optimization consistency.

-

5.

The algorithm’s convergence stability and performance variance were analyzed through multi-run statistical indicators, confirming its reliability in stochastic search environments.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes the SFOA, outlining its operators and search mechanism. Section 3 introduces the two case studies (a DC-motor speed regulation system and a three-tank liquid-level system) and presents their mathematical models. Section 4 details the cascaded exp-PID controller and its signal flow. Section 5 formulates the SFOA-based tuning procedure, including the performance index, parameter bounds for both plants, and the optimization workflow. Section 6 reports DC-motor results, first comparing the proposed controller with recent optimizers (FLA, GCRA, MSA, DO) and then with reported works (GWO, ASO, MMPA, LFDNM), together with parameter analyses, time-response plots, and multi-run statistics. Section 7 presents the corresponding three-tank results, with the same two-stage comparison (against recent optimizers and against reported methods (ALC-PSODE, MGO, AOA-HHO, CMA-ES)) and includes quantitative metrics and statistical evaluations. Section 8 concludes the study and outlines directions for future work.

Overview of starfish optimization algorithm

The SFOA is a bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm that mimics the behaviors of a starfish, including exploration, preying, and regeneration, to solve global optimization problems (as shown in Fig. 15. It is designed to balance exploration and exploitation through a hybrid search pattern. Starfish exhibit three remarkable behaviors that contribute to their survival and efficiency in nature. They explore their environment by extending their five arms, allowing them to navigate and search for resources. When hunting, they rely on their tube feet to capture prey with precision and adaptability. Additionally, their ability to regenerate lost limbs ensures resilience and continuity in their existence. Inspired by these natural strategies, SFOA incorporates these behaviors into an optimization algorithm, promoting thorough exploration and robust convergence.

The SFOA follows a structured mathematical framework composed of three fundamental stages. It begins with an initialization phase, where potential solutions are generated randomly to establish diversity within the search space. In the exploration phase, the algorithm mimics the starfish’s environmental probing, dynamically searching for improved solutions. Finally, the exploitation phase focuses on refining the best-obtained solutions, ensuring convergence toward optimal results with enhanced precision5. In the initialization phase, the population of starfish \(\:X\) is randomly initialized within the search space:

where \(\:{X}_{i,j}\) represents the position of the \(\:{i}^{th}\), starfish in the \(\:{j}^{th}\) dimension. \(\:N\) is the is the population size, and \(\:D\) is the number of design variables. In addition, each position is initialized as:

where \(\:{l}_{j},\:\)and\(\:\:{u}_{j}\) are the lower and upper bounds of the search space, and \(\:r\) is a random number.

The exploration phase ensures a diverse search, mimicking how starfish explore their environment. If \(\:D>5\), a five-dimensional search pattern is used:

where \(\:{X}_{best,p}^{\left(t\right)}\), \(\:t\) and \(\:{t}_{max}\) are the best solution in the population, the current iteration, the total number of iterations respectively. In addition, \(\:{a}_{1}=(2r-1)\pi\:\), \(\:\theta\:=\frac{\pi\:}{2}\left(\frac{t}{{t}_{max}}\right)\). If \(\:D\le\:5\), a one-dimensional search pattern is used:

where \(\:{X}_{{k}_{1},p}^{\left(t\right)}\), \(\:{X}_{{k}_{2},p}^{\left(t\right)}\), \(\:{A}_{1}\) and \(\:{A}_{2}\) are positions of randomly selected starfish, random numbers between − 1 and 1, respectively. In addition, \(\:{E}_{T}=\left(\frac{{t}_{max}-t}{{t}_{max}}\right)\cdot\:cos\theta\:\). After updating the positions, boundary constraints are enforcedç

The exploitation phase refines solutions through two key strategies:

-

Preying Behavior: Moves towards better positions using a two-directional search strategy:

where \(\:{d}_{m1}\), \(\:{d}_{m\:}\)are two randomly selected distances between the best solution and other starfish.

-

Regeneration Behavior: Ensures diversity by allowing the last starfish \(\:(i=N)\), to regenerate:

After updating, boundary constraints are applied:

Case studies

This section examines the application of the SFOA algorithm in optimizing exponential PID controller parameters for two different control systems: a DC motor speed regulation system and a three-tank liquid level control system. These case studies aim to evaluate the adaptability and effectiveness of the proposed optimization method. For the DC motor, the primary objective is to achieve precise and efficient speed regulation, a crucial requirement in numerous industrial applications. Meanwhile, the three-tank system focuses on maintaining stable liquid levels despite complex nonlinear interactions and dynamic disturbances. By developing detailed system models and conducting comparative analyses against well-established optimization techniques, these case studies highlight the SFOA algorithm’s ability to enhance system performance across diverse operating conditions.

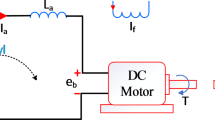

Mathematical modeling of DC motor system

In this section, explores the implementation of an externally excited DC motor for speed regulation by varying the armature voltage. Through an analysis of the corresponding electrical schematic, a mathematical model is developed to gain a thorough understanding of the motor’s behavior and electrical characteristics, as depicted in Fig. 2.

When the magnetic flux remains constant, the induced voltage \(\:{E}_{b}\), is directly proportional to the angular velocity \(\:{\omega\:}_{m}\), which represents the rate of change of rotation, \(\:\frac{d\theta\:}{dt}\)14.

The speed of an armature-controlled DC motor is regulated by the armature voltage \(\:{E}_{a}\). According to the mathematical model of the DC motor, the circuit can be described as follows.

Here, \(\:{I}_{a}\), \(\:{R}_{a}\), and \(\:{L}_{a}\) represent the armature current, armature resistance, and armature inductance of the DC motor, respectively. The torque produced by the armature current results from the combined influence of inertia and friction torques23.

Here, \(\:{\omega\:}_{m}\) denotes the angular speed of the motor shaft, \(\:J\) represents the moment of inertia, \(\:B\) is the motor friction constant, and \(\:K\) is the motor torque constant. By assuming all initial conditions of the system are zero, applying the Laplace transform to Eqs. (9–11) yields the following equation:

where \(\:{K}_{b}\) is electromotive force constant18,23. Finally, the open loop equation of the system for \(\:{T}_{L}=0\) is defined as follows:

Mathematical modeling of liquid level system

Three-tank liquid level control system

The goal of the three-tank liquid level control system is to regulate and maintain the liquid levels in Tanks 1, 2, and 3, as shown in Fig. 3. To simplify the model, several assumptions are considered. The tanks are open to the atmosphere, ensuring no pressure buildup. The liquid is considered incompressible, maintaining a constant total mass throughout the system. Fluid movement occurs exclusively from higher to lower levels between interconnected tanks, driven by natural gravitational flow. The system is assumed to be entirely leak-free, ensuring no unintended losses. Additionally, the flow rates are governed by the differences in liquid levels, which dictate the system’s dynamic behavior.

These dynamics are captured through the following differential Equations1,32.

In this system, \(\:{H}_{1}\),\(\:{H}_{2}\) and \(\:{H}_{3}\) represent the liquid levels in Tanks 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The flow rates \(\:{q}_{12}\), \(\:{q}_{13}\), and \(\:{q}_{23}\) are directly influenced by the differences in liquid levels between the tanks, ensuring that fluid moves from higher to lower levels. This relationship can be expressed mathematically as follows1:

The constants \(\:{k}_{12}\), \(\:{k}_{13}\), and \(\:{k}_{23}\) are determined by the system’s geometry and the physical properties of the liquid, influencing the rate of flow between tanks. To facilitate analysis, a simplified tank model is adopted, where \(\:{q}_{1}\) and \(\:{q}_{2}\:\)represent the inflow and outflow rates, respectively. The liquid height is denoted by\(\:\:\left(h\right)\), while \(\:\left(A\right)\:\)refers to the cross-sectional area of the tank1,33. To ensure consistency with previous studies, the system is modeled using a transfer function of the form:

This model allows for the simulation of the system’s dynamic behavior under different flow rates and control strategies. By implementing various control techniques, the flow rates can be adjusted to maintain the desired liquid levels, ensuring the system meets the requirements of specific applications. This approach enables precise regulation, making it adaptable to a wide range of industrial and process control scenarios. You can see brief schematic linking industrial applications with three tanks in Fig. 4.

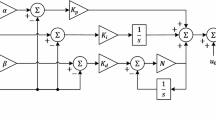

Concept of exponential PID controller

The cascaded exponential proportional–integral–derivative (exp-PID) controller is designed to enhance the adaptability and precision of control actions in nonlinear and time-varying dynamic systems. In contrast to a conventional PID controller, which applies constant gain values to the error signal and its derivative, the exp-PID incorporates nonlinear exponential transformations to adjust the control effort dynamically12. This structure provides improved transient response, reduced steady-state error, and enhanced robustness against external disturbances and parameter variations. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the exp-PID controller is composed of two interconnected subsystems: (i) the exponential block, which performs nonlinear modulation of the error dynamics, and (ii) the PID block, which generates the final control action based on the modified signals.

In the exponential block, the instantaneous error \(\:e\left(t\right)\) and its time derivative \(\:\frac{de\left(t\right)}{dt}\) are first weighted by time-varying scaling coefficients \(\:{\tau\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\), respectively. These scaled quantities are denoted as

Both signals are then passed through the nonlinear exponential activation function \(\:{f}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}}\left(u\right(t\left)\right)\), mathematically expressed as in (23).

This function maps the input into the bounded interval \(\:[-\text{1,1}]\), thereby suppressing large fluctuations in \(\:e\left(t\right)\) and \(\:\frac{de\left(t\right)}{dt}\) while amplifying smaller variations near equilibrium. The resulting nonlinear outputs are \(\:{f}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}}\left(k\right(t\left)\right)\) and \(\:{f}_{\text{e}\text{x}\text{p}}\left(l\right(t\left)\right)\). Each of these outputs is multiplied by corresponding gain coefficients \(\:{g}_{1}\)and \(\:{g}_{2}\). The combined outcome produces the auxiliary control signal \(\:\delta\:\left(t\right)\).

This nonlinear transformation allows the controller to emulate a self-tuning mechanism—strong corrective actions are moderated when the error is large, and fine adjustments are emphasized when the system approaches the desired setpoint. Consequently, the exponential block acts as an adaptive preprocessing unit that enhances system stability and mitigates overshoot in highly dynamic conditions. The output \(\:\delta\:\left(t\right)\) from the exponential block serves as the input to a conventional PID framework. The control signal \(\:u\left(t\right)\) is generated as:

where \(\:{K}_{p}\), \(\:{K}_{i}\), and \(\:{K}_{d}\) denote the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively. The integral term ensures zero steady-state error, while the derivative component enhances damping and anticipates future deviations. By acting on the nonlinear signal \(\:\delta\:\left(t\right)\), these classical components inherit the adaptability introduced by the exponential transformation. The overall controller thus realizes a cascaded nonlinear–linear architecture, where the exponential module modifies the input dynamics and the PID module performs fine regulation. This configuration offers both the interpretability of classical PID control and the flexibility of nonlinear modulation.

SFOA-based exp-PID controller

The SFOA is applied to optimize the parameters of the exp-PID controller for two distinct control systems: DC motor speed regulation and liquid level regulation. The primary objective is to minimize the cost function by fine-tuning the controller parameters, including \(\:{K}_{p}\), \(\:{K}_{i}\), \(\:{K}_{d}\), \(\:{\tau\:}_{1}\), \(\:{g}_{1}\), \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\) and \(\:{g}_{2}\), while ensuring optimal transient and steady-state performance.

Cost function

The cost function (\(\:CF\)) is designed to evaluate the performance of the exp-PID controller by considering key transient and steady-state characteristics. The cost function is defined as34:

where \(\:\rho\:\) is the balancing coefficient set to 1, \(\:{m}_{os}\) is the percentage overshoot, \(\:{e}_{ss}\) is the percentage steady-state error measured at the end of the simulation time \(\:{t}_{sim}\), \(\:{t}_{s}\) is the settling time within a ± 2% tolerance band, and \(\:{t}_{r}\) is the rise time from 10% to 90% of the final value. The cost function ensures a trade-off between steady-state accuracy and transient response, where the exponential term adjusts the influence of each component. The selection of simulation time varies based on the dynamics of the control system under evaluation. For a DC motor speed control system, the simulation time is set to 2 s to effectively capture the transient response and steady-state performance of the motor. In contrast, for a liquid level control system, a longer simulation time of 250 s is necessary due to the inherently slower response of liquid dynamics. This ensures that the controller’s performance, including settling time, overshoot, and steady-state error, is accurately assessed and optimized for each specific application.

Constraints of optimization problems

The optimization of the exp-PID controller is subject to predefined parameter constraints to ensure stability, robustness, and effective control performance. These constraints define the feasible search space for the optimization algorithm, preventing extreme values that may degrade system performance. For the DC motor speed control system, the parameter bounds are set as shown in Table 1. These bounds ensure the controller operates within a reasonable range for efficient motor speed regulation. For the liquid level control system, a different set of constraints is applied due to the slower response dynamics of fluid systems, as shown in Table 2. These constraints allow the optimization algorithm to tune the controller effectively while ensuring stability and accuracy in maintaining liquid levels.

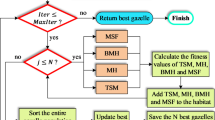

Application stage of SFOA

The SFOA-based tuning of the exp-PID controller follows an iterative process aimed at minimizing the cost function and enhancing system performance. The optimization begins with the initialization of controller parameters within predefined bounds. These parameters are then applied to the exp-PID controller, generating control signals that regulate the system’s response based on the reference input. The controller interacts with the plant model, producing an output that is evaluated using key performance metrics, including overshoot, steady-state error, rise time, and settling time. Once the system response is obtained, the cost function is computed to assess performance, ensuring a balance between transient and steady-state behavior. This cost function value is then processed within the SFOA module, where new controller parameters are generated based on the algorithm’s search and update rules. The process is repeated iteratively, refining the controller parameters with each cycle until an optimal solution is reached. For the DC motor speed regulation system, the optimization process continuously adjusts the controller parameters to enhance speed tracking and minimize errors. The control signal is applied to the plant model, and system response metrics are analyzed to iteratively fine-tune the controller settings, ensuring improved dynamic performance and stability. Similarly, in the liquid level regulation system, the same approach is applied, but with a focus on maintaining stability in slower-response dynamics.

Figure 6 shows the SFOA-based exp-PID design framework for DC motor system. On the other hand, the flowchart representation in Fig. 7 illustrates the structured workflow of SFOA optimization, where the exp-PID controller dynamically adapts to system conditions based on cost function evaluations. The iterative process ensures that the controller minimizes overshoot, reduces steady-state error, and improves settling time. By following this structured optimization framework, the proposed SFOA-based exp-PID controller achieves enhanced adaptability and efficiency, making it well-suited for both fast-response systems like DC motor speed control and slow-response systems like liquid level regulation. The continuous parameter tuning ensures optimal system performance while maintaining stability and robustness in dynamic control applications.

Simulation results on DC motor speed control system

Comparison with more recent algorithms

To assess the performance and robustness of the proposed SFOA-based exp-PID controller in regulating DC motor speed, a detailed comparative analysis was conducted with several recent metaheuristic algorithms. The competing optimizers included the flood algorithm (FLA)6, greater cane rat algorithm (GCRA)7, mantis search algorithm (MSA)8 and dandelion optimizer (DO)9. Each algorithm was implemented under identical simulation conditions, with a uniform population size and iteration limit, and each trial was repeated thirty times to ensure statistical consistency.

Statistical performance evaluation

The quantitative performance of each optimizer was evaluated in terms of the best, worst, mean, and standard deviation (SD) values of the defined cost function. The corresponding results are summarized in Table 3. Among all methods, the SFOA-based exp-PID achieved the lowest mean cost value of 1.6378 × 10⁻³, demonstrating both high accuracy and stability across independent runs. In contrast, the DO-based exp-PID exhibited the highest mean cost value (2.1472 × 10⁻³), indicating relatively weaker convergence and higher variance. The narrow SD of the proposed method (3.48 × 10⁻⁵) further confirms its reliable convergence characteristics and lower sensitivity to stochastic variations within the search process.

The convergence behavior of the cost function for all algorithms is illustrated in Fig. 8. The curve corresponding to the proposed SFOA-based exp-PID shows a markedly faster decline during the early iterations and stabilizes at a lower final value, signifying efficient exploration followed by refined local exploitation. By contrast, the DO-based controller displays sluggish convergence and stabilizes at a substantially higher cost level, while the remaining algorithms (FLA, GCRA, MSA) reach intermediate performance.

Optimized controller parameters

The optimized controller parameters derived from each algorithm are listed in Table 4. The SFOA-based exp-PID attained comparatively higher proportional (\(\:{K}_{p}\)) and integral (\(\:{K}_{i}\)) gains, as well as elevated exponential shaping coefficients (\(\:{\tau\:}_{1}\), \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\)), which collectively enhanced its transient and steady-state characteristics. These parameter trends indicate that the proposed optimization strategy effectively identifies gain combinations that accelerate response without introducing instability. The superior parameter balance also ensures smoother actuator behavior and reduced control effort.

Dynamic response analysis

The dynamic performance of each controller was investigated under a step-input reference signal. The transient responses shown in Fig. 9 reveal that the SFOA-based exp-PID achieves the fastest rise and settling times while entirely eliminating overshoot. The FLA- and MSA-based designs follow closely but show slightly slower convergence. In contrast, the DO-based exp-PID exhibits the slowest transient response, confirming its reduced adaptability in dynamic operating conditions.

A further assessment of steady-state behavior is presented in Fig. 10, where the motor speed tracking accuracy of each controller is compared. The SFOA-based and FLA-based controllers maintain the closest adherence to the reference speed, producing nearly zero steady-state error. Meanwhile, the DO- and GCRA-based designs display minor but noticeable deviations, reflecting their less effective fine-tuning of the integral and exponential parameters.

Quantitative performance indicators

Key performance metrics (including rise time, settling time, percentage overshoot, and steady-state error) are summarized in Table 5. The proposed SFOA-based exp-PID achieved a rise time of 0.0039 s, a settling time of 0.0083 s, zero overshoot, and an extremely small steady-state error of 2.53 × 10⁻⁴ %, confirming its outstanding dynamic precision. These improvements correspond to reductions of approximately 18–25% in transient durations compared with the next-best alternatives. Conversely, the DO-based exp-PID recorded the poorest results, with both the highest rise and settling times (0.0054 s and 0.0108 s) and a larger residual error (0.0067%).

Discussion

The overall comparison demonstrates that the starfish-driven tuning mechanism substantially enhances both convergence quality and control precision relative to other contemporary optimizers. By balancing its regenerative exploration and directional exploitation phases, SFOA avoids premature convergence and effectively searches the multimodal parameter landscape of the cascaded exp-PID controller. Consequently, it delivers superior transient behavior, minimal overshoot, and high steady-state accuracy in the DC-motor speed regulation task. The consistency between the statistical evidence (Table 3), parameter analysis (Table 4), convergence curve (Fig. 8) and temporal responses (Figs. 9 and 10) confirms that the SFOA-based exp-PID provides the most reliable and efficient control strategy among all tested algorithms.

Comparison with reported works

A comparative investigation was conducted between the proposed SFOA-based exponential PID (exp-PID) controller and several control methods previously reported in the literature to further validate its efficiency and robustness for DC motor speed regulation. The benchmarked methods included the grey wolf optimization (GWO)-based PID15, atom search optimization (ASO)-based PID14, marine predator algorithm (MMPA)-based PID30, hybrid Lévy flight distribution and Nelder–Mead algorithm (LFDNM)-based PID17. Each controller was tested under identical simulation conditions and reference inputs to ensure an equitable comparison of transient and steady-state behaviors.

Transient response comparison

The transient characteristics of the DC motor speed control system are illustrated in Fig. 11, where the speed responses obtained using the five control methods are compared. The proposed SFOA-based exp-PID exhibits the fastest rise and settling times, reaching the desired speed in a substantially shorter period than the alternative approaches. This improvement results from the nonlinear exponential preprocessing within the cascaded structure, which accelerates corrective actions during the initial response phase. Unlike the GWO- and ASO-based controllers, which display moderate oscillations before stabilization, the SFOA-based exp-PID demonstrates zero overshoot, ensuring a smooth approach to the reference value. The MMPA-based PID, on the other hand, exhibits pronounced overshoot and a longer settling period, suggesting an excessive exploratory search pattern that slows convergence in fine-tuning the control parameters. The LFDNM-based PID achieves acceptable transient performance but remains inferior in both speed and damping compared with the proposed approach. The smooth, monotonic transition of the SFOA-based controller emphasizes its superior damping characteristics and adaptability to dynamic changes in the armature current and torque response.

Steady-state response comparison

The steady-state behavior for the same set of controllers is presented in Fig. 12. It is evident that the SFOA-based exp-PID maintains the closest tracking to the reference speed, with an almost negligible steady-state deviation. In contrast, the GWO- and ASO-based controllers exhibit small but visible steady-state offsets, while the LFDNM-based design shows slight ripple around the target speed. The MMPA-based controller performs the worst in this aspect, as it fails to sustain stable operation and produces residual oscillations even after the system reaches steady state. The results confirm that the exponential term incorporated into the SFOA-tuned controller enhances integral compensation without inducing overshoot, allowing it to maintain steady operation and high accuracy despite disturbances or model nonlinearities.

Quantitative performance evaluation

A comprehensive comparison of quantitative performance metrics (including rise time, settling time, percentage overshoot, and steady-state error) is presented in Table 6. The proposed controller achieves a rise time of 0.0039 s and a settling time of 0.0083 s, outperforming all benchmarked techniques by a significant margin. Both times are an order of magnitude faster than those of the GWO- and ASO-based controllers (0.1388 s and 0.0692 s, respectively). The zero-overshoot characteristic of the SFOA-based exp-PID eliminates transient instability, which is particularly beneficial for precision electromechanical systems. The steady-state error achieved by the proposed controller is 2.53 × 10⁻⁴ %, which is nearly two orders of magnitude smaller than the smallest error among the reference methods. In contrast, the MMPA-based PID suffers from a large overshoot (7.01%) and elevated steady-state error (0.4358%), while the LFDNM-based PID, though relatively stable, records higher residual error (0.0051%) and slower convergence. These observations collectively demonstrate that the proposed optimization framework achieves both rapid transient convergence and precise steady-state accuracy.

Discussion

The superior performance of the SFOA-based exp-PID can be attributed to its balanced exploration–exploitation mechanism, which enables efficient global search during the early optimization stages and refined local adjustment near the optimum. The regenerative and multi-directional behaviors of the starfish algorithm prevent premature convergence while ensuring smooth parameter evolution, leading to stable and robust control actions. In contrast, the MMPA tends to over-explore the solution space, reducing tuning precision for low-dimensional control problems, whereas the ASO and GWO methods often stagnate in local minima due to their limited exploitation capability. The hybrid LFDNM approach improves convergence but lacks the nonlinear adaptation provided by the exponential transformation. Consequently, the SFOA-based exp-PID achieves the most favorable trade-off between fast response, minimal overshoot, and near-zero error, as corroborated by the results in Table 6; Figs. 11 and 12. Furthermore, the study adopts a linearized DC-motor model around its nominal operating point to maintain consistency with previously reported analyses. Although this simplification facilitates comparison, future investigations may extend the analysis to include the motor’s nonlinear electromagnetic effects and load disturbances to verify the controller’s performance under real-world conditions.

Simulation results on liquid level control system

Comparison with more recent algorithms

To evaluate the efficiency and reliability of the proposed SFOA-based exponential PID (exp-PID) controller in regulating the liquid level system, a comprehensive comparison was conducted with several recently developed metaheuristic optimizers. The competing algorithms included the FLA6, GCRA7, MSA8 and DO9. Each optimizer was tested under identical simulation settings (equal population size, iteration limit, and thirty independent runs) to ensure fair statistical comparison and to minimize random bias.

Statistical performance evaluation

The statistical outcomes summarizing the best, worst, mean, and standard deviation (SD) of the objective-function values are provided in Table 7. The proposed SFOA-based exp-PID achieved the lowest mean cost value of 2.9676 × 10⁻¹, reflecting the most efficient optimization among all methods. In contrast, the MSA-based exp-PID produced the highest mean cost (3.6086 × 10⁻¹) and widest performance spread, indicating a tendency toward inconsistent convergence. The FLA-, GCRA-, and DO-based variants displayed intermediate results but remained inferior in terms of both mean and SD. Overall, the proposed controller achieved up to 17.8% reduction in cost relative to the MSA-based approach and consistent gains of 5–12% compared with the other methods. These findings confirm that the SFOA’s multi-directional exploration and regenerative behavior effectively locate the global optimum with high stability.

The convergence profiles of all algorithms are depicted in Fig. 13. The SFOA-based curve shows the steepest decline in the early iterations and stabilizes at a minimum cost plateau, confirming its rapid convergence capability. The MSA-based controller exhibits an oscillatory trend before settling, while the FLA- and GCRA-based versions converge more slowly, underscoring their weaker exploitation efficiency.

Optimized controller parameters

The optimal parameter sets determined for each control method are summarized in Table 8. The SFOA-tuned controller yielded the highest proportional (\(\:{K}_{p}\)) and exponential scaling coefficients (\(\:{\tau\:}_{1}\), \(\:{\tau\:}_{2}\)), along with finely balanced integral (\(\:{K}_{i}\)) and derivative (\(\:{K}_{d}\)) gains. This combination enhances the controller’s adaptability and responsiveness to level variations. In comparison, the MSA-based optimizer produced smaller \(\:{K}_{p}\) and less effective exponential shaping parameters, resulting in sluggish behavior and greater steady-state deviations. The DO- and FLA-based designs displayed moderate parameter distributions, whereas the GCRA-based variant emphasized larger integral gains, causing mild oscillatory responses. These parameter trends demonstrate that the SFOA efficiently identifies gain relationships that yield faster rise and settling times without introducing instability. The resulting control signal exhibits smoother actuation and lower energy expenditure, which are critical for precision process-control systems.

Transient and steady-state response analysis

The transient responses of the liquid-level control system for all tested algorithms are presented in Fig. 14. The proposed SFOA-based exp-PID provides the fastest rise time and the shortest settling time, reaching the desired level with minimal oscillation. The FLA-based design performs comparably but with slightly slower convergence, while the DO-based controller produces a moderate response accompanied by a small overshoot. In contrast, the MSA-based exp-PID exhibits the slowest reaction and pronounced oscillations, extending the stabilization period and indicating inferior damping performance.

The steady-state characteristics, illustrated in Fig. 15, show that the SFOA-based exp-PID maintains the liquid level extremely close to the setpoint with nearly zero steady-state error. The DO-based controller demonstrates acceptable accuracy but a slightly higher residual error, while the FLA-based exp-PID deviates more noticeably, implying possible long-term offset. These results highlight the strong steady-state precision achieved by the SFOA-tuned nonlinear control structure.

Quantitative performance indicators

A comparative summary of key dynamic metrics (rise time, settling time, percentage overshoot, and steady-state error) is provided in Table 9. The SFOA-based exp-PID records a rise time of 1.7202 s and a settling time of 2.4715 s, outperforming all other algorithms. Its overshoot remains tightly limited at 1.4976%, and the steady-state error is only 9.219 × 10⁻⁵ %, confirming exceptional tracking accuracy. By contrast, the MSA-based controller shows the slowest transient performance (rise time = 2.1206 s; settling time = 3.0499 s), while the DO-based variant, though faster, exhibits the largest overshoot (1.8518%). The FLA- and GCRA-based controllers fall between these extremes but still trail behind the SFOA in all performance aspects.

In industrial applications, the freeboard constraint (the margin between the nominal level \(\:{h}_{n}\) and the tank’s maximum permissible level \(\:{h}_{max}\)) is a safety criterion. The permissible overshoot can be expressed as \(\:{h}_{max}={h}_{n}(1+{M}_{p}/100)\:\)where \(\:{M}_{p}\) denotes percentage overshoot. Assuming \(\:{h}_{n}=0.8\text{\hspace{0.17em}m}\) and \(\:{h}_{max}=0.9\text{\hspace{0.17em}m}\), the allowable overshoot equals 12.5%. As reported in Table 9, the SFOA-based exp-PID’s overshoot (1.4976%) and even the highest observed overshoot (1.8518% for the DO-based controller) remain well within this practical safety limit. Thus, all tested controllers operate under safe transient conditions, but the proposed approach achieves the most stable and efficient regulation.

Discussion

The comparative analysis unequivocally demonstrates that the SFOA-driven tuning strategy enhances both optimization quality and control precision. Its distinctive regenerative search and multidirectional arm-extension mechanisms enable a balanced exploration–exploitation process, preventing premature convergence and ensuring refined local adjustment of controller gains. The statistical evidence (Table 7), optimized parameter patterns (Table 8), convergence curve (Fig. 13) and dynamic responses (Figs. 14 and 15) collectively validate the superiority of the proposed SFOA-based exp-PID controller. It delivers faster transient response, minimal overshoot, and nearly zero steady-state error while maintaining operational safety margins within industrial freeboard limits. Consequently, this controller can be considered a robust and efficient solution for precise liquid-level regulation in nonlinear, slow-dynamics process systems.

Comparison with reported works

A further comparative study was performed to validate the effectiveness of the proposed SFOA-based exp-PID controller for the three-tank liquid-level control system against a series of recently reported optimization-based PID methods. The benchmarked controllers include the ALC-PSODE-based PID33, MGO-based PID1, AOA-HHO-based PID32 and CMA-ES-based PID32. All controllers were simulated under identical operating conditions, reference inputs, and dynamic parameters to ensure a fair and reproducible evaluation of both transient and steady-state performances.

Transient-response evaluation

The transient responses of the various controllers are depicted in Fig. 16. The proposed SFOA-based exp-PID achieves the fastest rise and settling times, enabling the liquid level to reach the desired value far earlier than the other benchmarked methods. The controller responds smoothly to step changes, reflecting the benefit of the exponential nonlinearity in the cascaded structure, which accelerates error correction without introducing oscillation. In contrast, the ALC-PSODE-based PID and MGO-based PID present slower transients with noticeable overshoot, while the AOA-HHO-based PID and CMA-ES-based PID show significantly delayed stabilization and high oscillatory behavior. The large settling times of the latter two controllers indicate limited exploitation capacity and slower convergence within their optimization processes. The minimal overshoot achieved by the proposed controller prevents level excursion beyond the permissible range—an essential feature in safety-critical process operations.

Steady-state performance

The steady-state characteristics illustrated in Fig. 17 further confirm the superiority of the proposed controller. Once the transient phase ends, the SFOA-based exp-PID maintains the liquid level almost perfectly at the reference value, exhibiting an extremely small steady-state error. By comparison, the ALC-PSODE-based and MGO-based controllers show small but measurable offsets, while the AOA-HHO- and CMA-ES-based PIDs experience persistent deviations and low-frequency ripples around the setpoint. This steady-state precision demonstrates that the SFOA-tuned exponential terms effectively enhance the integral action without inducing sluggishness, allowing precise long-term level regulation despite the nonlinear flow dynamics and slow system response inherent to multi-tank configurations.

Quantitative performance assessment

The quantitative metrics summarized in Table 10 provide a comprehensive overview of the transient and steady-state performance for all controllers. The proposed SFOA-based exp-PID achieves a rise time of 1.7202 s, settling time of 2.4715 s, overshoot of 1.4976%, and a steady-state error of 9.219 × 10⁻⁵ %. These results represent substantial improvements over all reference methods. For comparison, the CMA-ES-based PID exhibits an exceptionally long settling time of 238.6706 s and a high overshoot of 50.1692%, while the AOA-HHO-based PID reaches 160.1083 s with an overshoot exceeding 20%. The ALC-PSODE-based and MGO-based PIDs perform moderately but still present large deviations (overshoot ≈ 12%) and significantly longer stabilization times (60–64 s). The near-zero steady-state error of the proposed controller, several orders of magnitude smaller than those of its counterparts, confirms its superior tracking precision and robustness to steady disturbances. The slower convergence of the CMA-ES-based PID can be attributed to the covariance-matrix adaptation process, which tends to progress conservatively on the highly nonlinear cost surface introduced by the exponential transformation. Conversely, the SFOA’s adaptive regeneration and multidirectional search strategy ensures both rapid convergence and refined local adjustment, yielding optimal control gains even in such complex optimization landscapes.

Discussion

The comparative outcomes demonstrate that the SFOA-driven tuning mechanism provides a well-balanced combination of exploration and exploitation, enabling efficient global search during the early optimization phase and precise local refinement near the optimum. This behavior allows the exp-PID controller to maintain stability, accuracy, and low energy consumption even under nonlinear, slow-response conditions typical of multi-tank systems. As evidenced by the data in Table 10 and the temporal behaviors in Figs. 16 and 17, the SFOA-based exp-PID significantly outperforms all reported counterparts in every evaluated metric. Its rapid rise and settling times, minimal overshoot, and negligible steady-state error make it a highly reliable and efficient solution for complex fluid-level regulation tasks. Furthermore, the results confirm that the integration of exponential nonlinearity with starfish-based adaptive optimization introduces a generalized control framework that can be extended to a wide range of industrial process-control applications.

Conclusion and future work

A cascaded exponential PID controller optimized through the SFOA has been developed and extensively analyzed in this study. The combination of exponential error modulation and the adaptive regeneration mechanism of SFOA enabled precise control with rapid convergence and strong robustness against nonlinearities and parameter variations. Comprehensive simulations on a DC-motor system and a three-tank liquid-level process confirmed the efficiency of the proposed approach. In the DC-motor case, the SFOA-tuned exp-PID achieved a rise time of 0.0039 s, settling time of 0.0083 s, and zero overshoot, indicating a near-ideal transient response. For the three-tank system, the controller achieved a rise time of 1.72 s, settling time of 2.47 s, overshoot of 1.50%, and steady-state error below 1 × 10⁻⁴ %, outperforming competing algorithms such as FLA, GCRA, MSA, and DO under identical conditions. Statistical comparisons across 25 runs verified the convergence stability and repeatability of the proposed method. These findings demonstrate that the SFOA-based exp-PID offers a versatile and reliable solution for nonlinear process control, achieving faster responses and enhanced steady-state accuracy compared to conventional and recently developed optimization-based controllers.

Although the present study focused on simulation-based validation, future research will explore real-time implementation on embedded platforms (e.g., Arduino, STM32, or dSPACE) to assess hardware efficiency and control latency. Extending the approach to fractional-order and multi-objective optimization frameworks may further improve dynamic adaptability and control smoothness. The hybridization of SFOA with complementary techniques such as Differential Evolution (DE), reinforcement learning, or adaptive fuzzy logic is also a promising avenue for achieving faster convergence and improved learning capability. Moreover, applying the proposed controller to more complex systems (such as renewable-energy conversion units, robotic manipulators, and autonomous mechatronic platforms) could demonstrate its scalability and generalization potential. These developments are expected to establish the SFOA-based exp-PID as a robust, intelligent, and industry-ready control paradigm.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ekinci, S. et al. Advanced control parameter optimization in DC motors and liquid level systems. Sci. Rep. 15, 1394. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85273-y (2025).

Jabari, M. et al. Efficient pressure regulation in nonlinear shell-and-tube steam condensers via a novel TDn(1 + PIDn) controller and DCSA algorithm. Sci. Rep. 15, 2090. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86107-7 (2025).

Kong, W. et al. PID control algorithm based on multistrategy enhanced Dung beetle optimizer and back propagation neural network for DC motor control. Sci. Rep. 14, 28276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79653-z (2024).

Cong, X. & Guo, L. PID control for a class of nonlinear uncertain stochastic systems. In: 2017 IEEE 56th Annual Conference on Decision and Control (CDC). 612–617 https://doi.org/10.1109/CDC.2017.8263728 (IEEE, 2017).

Zhong, C. et al. Starfish optimization algorithm (SFOA): a bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization compared with 100 optimizers. Neural Comput. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-024-10694-1 (2024).

Ghasemi, M. et al. Flood algorithm (FLA): an efficient inspired meta-heuristic for engineering optimization. J. Supercomput. 80, 22913–23017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-024-06291-7 (2024).

Agushaka, J. O. et al. Greater cane rat algorithm (GCRA): A nature-inspired metaheuristic for optimization problems. Heliyon 10, e31629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31629 (2024).

Abdel-Basset, M., Mohamed, R., Zidan, M., Jameel, M. & Abouhawwash, M. Mantis search algorithm: A novel bio-inspired algorithm for global optimization and engineering design problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 415, 116200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2023.116200 (2023).

Zhao, S., Zhang, T., Ma, S., Chen, M. & Optimizer, D. A nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 114, 105075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105075 (2022).

Izci, D., Ekinci, S., Kayri, M. & Eker, E. A novel improved arithmetic optimization algorithm for optimal design of PID controlled and bode’s ideal transfer function based automobile cruise control system. Evol. Syst. 13, 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12530-021-09402-4 (2022).

Bhookya, J., Vijaya Kumar, M., Ravi Kumar, J. & Seshagiri Rao, A. Implementation of PID controller for liquid level system using mGWO and integration of IoT application. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 28, 100368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jii.2022.100368 (2022).

Çelik, E. Exponential PID controller for effective load frequency regulation of electric power systems. ISA Trans. 153, 364–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2024.07.038 (2024).

Jabari, M., Ekinci, S., Izci, D., Bajaj, M. & Zaitsev, I. Efficient DC motor speed control using a novel multi-stage FOPD(1 + PI) controller optimized by the pelican optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14, 22442. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73409-5 (2024).

Hekimoglu, B. Optimal tuning of fractional order PID controller for DC motor speed control via chaotic atom search optimization algorithm. IEEE Access. 7, 38100–38114. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2905961 (2019).

Agarwal, J., Parmar, G., Gupta, R. & Sikander, A. Analysis of grey Wolf optimizer based fractional order PID controller in speed control of DC motor. Microsyst. Technol. 24, 4997–5006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00542-018-3920-4 (2018).

Zare, R., Mohajery, H. & Shayeghi, P. Optimal FOTID controller design for regulation of DC motor speed. Int. J. Tech. Phys. Probl. Eng. 14, 57–63 (2022).

Izci, D. Design and application of an optimally tuned PID controller for DC motor speed regulation via a novel hybrid Lévy flight distribution and Nelder–Mead algorithm. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 43, 3195–3211. https://doi.org/10.1177/01423312211019633 (2021).

Ekinci, S., Hekimoğlu, B. & Izci, D. Opposition based Henry gas solubility optimization as a novel algorithm for PID control of DC motor. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 24, 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2020.08.011 (2021).

Jabari, M. et al. A novel artificial intelligence based multistage controller for load frequency control in power systems. Sci. Rep. 14, 29571. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81382-2 (2024).

Jabari, M. et al. Efficient parameter extraction in PV solar modules with the diligent crow search algorithm. Discover Energy. 4, 35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43937-024-00063-3 (2024).

Jabari, M. et al. Parameter identification of PV solar cells and modules using bio dynamics grasshopper optimization algorithm. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 18, 3314–3338. https://doi.org/10.1049/gtd2.13279 (2024).

Rizk-Allah, R. M. et al. Incorporating adaptive local search and experience-based perturbed learning into artificial rabbits optimizer for improved DC motor speed regulation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 162, 110266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2024.110266 (2024).

Ayinla, S. L. et al. Optimal control of DC motor using leader-based Harris Hawks optimization algorithm. Frankl. Open. 6, 100058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fraope.2023.100058 (2024).

Munagala, V. K. & Jatoth, R. K. A novel approach for controlling DC motor speed using NARXnet based FOPID controller. Evol. Syst. 14, 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12530-022-09437-1 (2023).

Başçi, A. & Derdiyok, A. Implementation of an adaptive fuzzy compensator for coupled tank liquid level control system. Measurement 91, 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2016.05.026 (2016).

Meng, X., Yu, H., Zhang, J., Xu, T. & Wu, H. Liquid level control of Four-Tank system based on active disturbance rejection technology. Measurement 175, 109146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2021.109146 (2021).

Yu, S. et al. Liquid level tracking control of Three-tank systems. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 18, 2630–2640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12555-018-0895-y (2020).

Rajasekhar, N., Radhakrishnan, T. K. & Samsudeen, N. Decentralized multi-agent control of a three-tank hybrid system based on twin delayed deep deterministic policy gradient reinforcement learning algorithm. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 12, 1098–1115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-023-01227-0 (2024).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D. & Yilmaz, M. Efficient speed control for DC motors using novel gazelle simplex optimizer. IEEE Access. 11, 105830–105842. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3319596 (2023).

Ramezani, M., Bahmanyar, D. & Razmjooy, N. A new improved model of marine predator algorithm for optimization problems. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46, 8803–8826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-05688-3 (2021).

Guo, Y. & Mohamed, M. E. A. Speed control of direct current motor using ANFIS based hybrid P-I-D configuration controller. IEEE Access. 8, 125638–125647. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3007615 (2020).

Issa, M. Enhanced arithmetic optimization algorithm for parameter Estimation of PID controller. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 2191–2205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-022-07136-2 (2023).

Moharam, A., El-Hosseini, M. A. & Ali, H. A. Design of optimal PID controller using hybrid differential evolution and particle swarm optimization with an aging leader and challengers. Appl. Soft Comput. 38, 727–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2015.10.041 (2016).

Izci, D., Ekinci, S., Eker, E. & Kayri, M. Augmented hunger games search algorithm using logarithmic spiral opposition-based learning for function optimization and controller design. J. King Saud Univ. - Eng. Sci. 36, 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksues.2022.03.001 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by European Union under the REFRESH—Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-Tech Industries Project via the Operational Programme Just Transition under Grant CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048; in part by the National Centre for Energy II and ExPEDite Project a Research and Innovation Action to Support the Implementation of the Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission Project TN02000025; and in part by ExPEDite through European Union’s Horizon Mission Programme under Grant 101139527. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Stanislav Misak for his exceptional supervision, project administration, and overall guidance throughout the course of this project. His expertise and support were instrumental to its success.

Funding

This research is funded by European Union under the REFRESH—Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-Tech Industries Project via the Operational Programme Just Transition under Grant CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048; in part by the National Centre for Energy II and ExPEDite Project a Research and Innovation Action to Support the Implementation of the Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission Project TN02000025; and in part by ExPEDite through European Union’s Horizon Mission Programme under Grant 101139527.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Davut Izci, Serdar Ekinci, Mostafa Jabari: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—Original draft preparation, Mohit Bajaj, Emre Çelik: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing. Lukas Prokop, Olena Rubanenko: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Izci, D., Jabari, M., Çelik, E. et al. Designing a cascaded exponential PID controller via starfish optimizer for DC motor and liquid level systems. Sci Rep 15, 44504 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28145-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28145-9