Abstract

Integrated estimation and control present an ongoing challenge for robotic systems. Because controllers depend on data derived from measured states and parameters, which are often subject to uncertainties and noise. The suitability of frameworks depends on the complexity of the task and the constraints of computational resources. They must strike a balance between computational efficiency for rapid responses while maintaining accuracy and robustness for safe and reliable missions. This study capitalizes on recent advancements in neuromorphic computing tools, especially spiking neural networks (SNNs), and their applications in robotic and dynamical systems. We present a learning-free framework featuring a recurrent network of leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons, designed to mimic a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) provided by a robust filtering strategy called extended modified sliding innovation filter (EMSIF). Thus, our proposed framework benefits from the robustness of EMSIF and the computational efficiency of SNN. The weight matrices of SNN are tailored to match the desired system model, eliminating the need for training. Moreover, the network leverages a biologically plausible firing rule akin to predictive coding. Furthermore, in the presence of various uncertainties, the SNN-LQR-EMSIF compared with non-spiking LQR-EMSIF, and the optimal strategy called linear quadratic Gaussian (LQG) based on extended Kalman filter. We evaluate their performance in a workbench problem and, next in the satellite rendezvous maneuver implement the Clohessy-Wiltshire (CW) model. Results demonstrated that the SNN-LQR-EMSIF achieves acceptable performance in terms of computational efficiency, robustness, and accuracy, positioning it as a promising approach for addressing the challenges of Integrated estimation and control in dynamic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the design and implementation of robotic manipulators/systems undertaking diverse real-world tasks grow more ambitious, the importance of computational efficiency, reliability, and accuracy escalates. Currently, many of the implemented controllers rely heavily on the provision of accurate information about the system states and parameters, which is typically obtained through various types of sensors such as inertial measurement units (IMUs), GPS, LIDAR, and vision-based systems1. However, achieving such precision is often elusive due to the multifaceted uncertainties inherent to robotic systems. These uncertainties stem from environmental instabilities (e.g., lighting variations, terrain irregularities), sensor noise, latency, and hardware limitations. For instance, IMUs suffer from integration drift over time, GPS may become unreliable in urban canyons or indoors, and vision-based systems can fail under poor lighting or occlusion conditions. Additionally, system dynamics may include unmodeled behaviors or disturbances that are not fully captured in the sensing process. In many real-world scenarios, it is impractical—if not impossible—to obtain full measurements of all state variables at every time step. These factors collectively contribute to data degradation, which in turn impacts the reliability and performance of the control system. Consequently, to utilize the ability of noise canceling, and estimating the unmeasured states/parameters the performing estimation concurrently with control becomes essential to ensure safe, robust, and accurate behavior in robotic systems2,3. From the other perspective, considering the constraints imposed by computing resources and energy consumption particularly for the complex transportation systems utilizing electric vehicles4, the development of concurrent estimation and control frameworks that excel in computational efficiency, robustness, and accuracy becomes significantly important. Nowadays, the linear quadratic Gaussian (LQG) which is a popular and optimal framework for simultaneous estimation and control of linear dynamical systems, in its traditional algorithmic version which is implementable on traditional computers (Von Neumann computer architectures) has found widespread adoption across various domains such as robotic manipulators5, robot control6, robot path planning7, and satellite control8. However, in addition to the high energy consumption of the traditional computers for extensive problems, the LQG framework is not without its inherent limitations. The LQG framework is a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) that works based on the state feedback provided by the Kalman filter (KF)9. When confronted with uncertain dynamic models, its performance diminishes, and in the presence of external disturbances, it is not robust enough10. In such circumstances, the KF employed in conjunction with LQR control falls short of providing accurate information about system states/parameters. Consequently, the demonstrated limitations of the LQG underscore the pressing need for the development of a framework grounded in robust estimation principles. In addition to conventional estimation-control strategies such as LQG and observer-based methods, the literature includes various approaches for integrated estimation and control, including model predictive control (MPC)11, and machine learning-based strategies12. While these methods offer adaptability and performance benefits in certain contexts, they typically demand substantial computational resources and training time. So, benefiting, the advantages of neuromorphic computing, like highly parallel computing nature of spiking neural networks (SNN), that work with extremely low computational burden, and also they are implementable on neuromorphic computers13, In14, Slijkhuis et al., proposed an SNN-based framework for Integrated estimation and control, employing a combination of the Luenberger observer and LQR controller. They applied their method to scenarios involving a spring-mass-damper (SMD) system and a Cartpole system, evaluating its performance in terms of accuracy and similarity to its non-spiking counterpart. They also explored the robustness of their network in handling neuron silencing. While their results were promising, their framework had limitations, notably the need to design both controller and observer gains for each problem. Additionally, since they used the Luenberger observer, their framework inherited the observer limitations related to modeling uncertainties and noise canceling, which were not thoroughly assessed for robustness. Thus, based on the mentioned successful application of SNNs in the estimation and control and the works done in15,16,17, to address the mentioned limitations with observer-based approaches in previous works, here we propose a SNN-based concurrent estimation and control framework utilizing the SNN-based filtering strategies. To this aim, SNN-KF which was proposed in18 for optimal estimation of linear dynamical systems and its nonlinear version in19 has been considered. In addition to performing the optimal estimation, these filtering approaches eliminated the need for observer gain design, simplifying the process. Then, to enhance robustness against modeling uncertainties and environmental disturbances, a robust SNN-based estimation framework based on EMSIF was introduced. Thus, here we propose a robust framework, LQR-EMSIF, which integrates the LQR controller with the extended modified sliding innovation filter (EMSIF), a recently developed robust estimation technique18,19,20. The LQR-EMSIF leverages the robustness of the EMSIF filter in processing raw data obtained from measurement systems. The EMSIF represents an evolution of the sliding innovation filter (SIF), which belongs to the family of variable structure filters (VSF)20, and also it can be considered as a new generation of smooth variable structure filter (SVSF)21. Importantly, unlike the KF family, which prioritizes frameworks founded on minimal estimation error, the VSF family of algorithms has been developed based on guaranteed stability in the presence of bounded modeling uncertainties and external disturbances22. Additionally, considering the recent advancements in neuromorphic computing tools, including spiking neural networks (SNN), and their applications in robotics control and estimation14,18, as well as the spike coding theories23, we present a pioneering approach. In this study, to introduce a framework that comprehensively addresses the aforementioned limitations, we translate the LQR-EMSIF into a neuromorphic SNN-based framework, in which the firing rule derived from the predicted error of the network concerning the estimated state vector, constituting a manifestation of predictive coding23. This theory posits that the brain perpetually constructs and enhances a ‘mental model’ of its surrounding environment, serving the critical function of anticipating sensory input signals, which are subsequently compared with the actual sensory inputs received. As the concept of representation learning gains increasing prominence, predictive coding theory has found vibrant application and exploration within the realms of biologically inspired neural networks, such as SNN. The adoption of SNNs mitigates the computational efficiency challenges associated with this problem24. Owing to their minimal computational burden and inherent scalability, SNNs offer significant advantages over traditional non-spiking computing methods13. SNNs represent the third generation of neural networks, taking inspiration from the human brain, where neurons communicate using electrical pulses called spikes. SNNs leverage neural circuits composed of neurons and synapses, communicating via encoded data through spikes in an asynchronous fashion13,25,26,27,28. The asynchronous in spiking fashion characterized by event-driven processing18, stands in contrast to traditional Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)29,30,31, which operate synchronously or, in other words, are time-driven. Studies32 demonstrate that, for equivalent tasks, SNNs are 6 to 8 times more energy efficient than ANNs with an acceptable trade-off in accuracy33. Moreover, the inherent scalability of SNNs enhances their reliability, particularly under the condition of neuron silencing, where neuron loss is compensated for by an increase in the spiking rate of remaining neurons25. Thus, to harness the advantage of SNNs for the simultaneous robust estimation and control, here, we integrate the methods proposed in prior studies18, and14 to develop the previously mentioned SNN-LQR-EMSIF framework, anticipating substantial advantages. Subsequently, we assess the performance of the proposed SNN-LQR-EMSIF framework through a series of evaluations. Initially, we apply it to a linear workbench problem, followed by its application to the intricate task of satellite rendezvous in circular orbit, a critical maneuver in space robotic applications such as on-orbit servicing and refueling34, we then compare the SNN-LQR-EMSIF with its non-spiking counterpart, LQR-EMSIF, and the standard LQG under various sources of uncertainty, including modeling uncertainty, measurement outliers, and neuron silencing, finally the proposed model has been compared with a learning-based neuromorphic model. For the proposed framework, our findings revealed an acceptable performance in terms of curacy, and robustness while it outperforms the traditional frameworks in terms of computational efficiency. While this study builds upon foundational elements introduced in our earlier works, it presents a novel and unified neuromorphic framework for simultaneous estimation and control using spiking neural networks (SNNs). Unlike our prior studies, which focused separately on just estimation18,19 or learning-based neuromorphic control15, the proposed method integrates a robust estimation strategy (EMSIF) with a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) into a unified SNN-based architecture. Notably, we considered a biologically plausible firing rule based on predictive coding, enabling spike-efficient behavior and controlled neural activity without requiring any training. This integration allows direct decoding of control signals from spike activity, eliminating the need for sequential estimation-control logic.

Primarily, the contributions in this study can be pointed as: (1) introduction of a robust SNN-based framework for Integrated estimation and control of dynamical systems, named SNN-LQR-EMSIF; (2) implementing a biologically plausible firing rule based on the concept of predictive coding concept, enhancing the biological relevance of our network and having control over the spike distribution in the network and prevent excessive spiking for a part of the network or a neuron; (3) comprehensive investigation on the performance of the proposed method in scenarios subjected to modeling uncertainties, measurement outliers, and neuron silencing along with analyzes on the sparsity in the spiking patterns to demonstrate computational efficiency; (4) application of the SNN-LQR-EMSIF to a real-world scenario involving Integrated estimation and control of satellite rendezvous, a novel application for this type of neuromorphic framework. Together, these contributions differentiate this work from prior literature and position it as a significant step forward in developing scalable, robust, and biologically inspired neuromorphic solutions for real-time robotic control applications.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Sect. “Theory” introduces the preliminaries, theoretical foundations, and the proposed framework developed to address the problem of integrated robust estimation and control in linear dynamical systems. Section “Numerical simulation” then presents the numerical simulations along with a discussion of the obtained results, and Sect. “Conclusion” concludes the study with closing remarks.

Theory

To establish the foundation for the proposed estimation and control strategy, we begin by formally defining the class of nonlinear systems under consideration, along with the associated uncertainties and control objectives. Thus, in this section, we provide essential preliminaries, followed by an outline of the study’s outcomes. The nonlinear dynamical system and measurement package considered in this study are defined by the following equations:

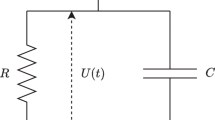

Here, \({\varvec{x}}\in {R}^{{n}_{x}}\) refers to the state vector, \({\varvec{u}}\in {R}^{{n}_{u}}\) is the input vector, \({\varvec{z}}\in {R}^{{n}_{z}}\) is the measurement vector. \(f(.)\) and \(h(.)\) refer the nonlinear dynamic and measurement model respectively. \({\varvec{w}}\) and \({\varvec{d}}\) represent the zero-mean Gaussian white noise with covariance matrices \(Q\), and \(R\), respectively. Figure 1 depicts the traditional block diagram of a Integrated estimation and control loop in conventional dynamical systems. This diagram reveals that both the estimator and controller employ sequential algorithms, resembling the logic of traditional von Neumann computer architectures.

Spiking neural network (SNN)

In this section, we present a brief overview of implementing an SNN, including its firing rule. To design a network composed of recurrent leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons capable of approximating the temporal variation of a parameter like \({\varvec{x}}\) as expressed in Eq. (1), we need to implement the following equation14:

Here, \({\varvec{\sigma}}\in {R}^{N}\) refers to the neuron membrane potential vector, λ is a decay or leak term considered on the membrane potential of the neurons, \(D\in {R}^{{n}_{x}\times N}\) is the random fixed decoding matrix containing the neurons’ output kernel, and \({\varvec{s}}\in {R}^{N}\) is the emitted spike population of the neurons in each time step. Further, according to spike coding network theories14,23, the introduced network of LIF neurons can reproduce the temporal variation of \({\varvec{x}}\) under two assumptions. First, we should be able to estimate \({\varvec{x}}\) from neural activity (filtered spike trains) using the following rule:

Here, \(\widehat{{\varvec{x}}}\) is the estimated state, and \({\varvec{r}}\in {R}^{N}\) represents the filtered spike trains, which have slower dynamics compared to \({\varvec{s}}\in {R}^{N}\). The dynamics of the filtered spike trains are provided by:

The second assumption states that the network seeks to minimize the cumulative discrepancy between the true state \({\varvec{x}}\) and its estimated counterpart \(\widehat{{\varvec{x}}}\). This optimization is performed by adjusting the spike timing rather than altering the output kernel values \(D\). In other words, the network reduces the overall prediction error while managing computational efficiency through the regulation of spike occurrence. To this aim, the following cost function is minimized23:

Here, \({\Vert .\Vert }_{2}^{2}\) represents the Euclidean norm, and \({\Vert .\Vert }_{1}\) indicates L1-norm. This firing rule ensures that each neuron emits a spike only when it contributes to reducing the predicted error, resembling a form of predictive coding23. Finally, along with obeying the mentioned rules, the neurons will emit spikes when their membrane potential reaches their specific thresholds. Thus, to ensure a biologically plausible spiking pattern, we define thresholds using the following expression:

Here, \({D}_{i}\) is \({i}^{th}\) column of the matrix \(D\), which represents \({i}^{th}\) neuron’s output kernel that reflects the change in the error due to a spike of \({i}^{th}\) neuron. The parameters \(\nu\) and \(\mu\) play critical roles in balancing computational efficiency and estimation accuracy within the network. The parameter \(\nu\) acts as a sparsity regularizing agent. By reducing \(\nu\), the network is encouraged to generate fewer spikes, which in turn reduces the overall computational cost due to spike generation, making the system more energy-efficient and suitable for neuromorphic deployment. On the other hand, the parameter \(\mu\) influences a quadratic penalty term that promotes an even distribution of spikes among the neurons. This helps prevent over-reliance on a small subset of neurons and supports a more robust and balanced network activity. Together, these parameters enable fine-tuning of the network behavior to achieve an acceptable trade-off between resource usage and functional performance. It is notable that proper tuning of these parameters yields biologically plausible spiking patterns, where neural activity in biological brain is distributed approximately evenly among neurons. This is achieved through a firing rule that minimizes prediction error by regulating spike occurrences in response to excitation and inhibition. Note that throughout this study for all the simulations the parameters \(\nu\) and \(\mu\) have been tuned using trial-and-error (e.g.: changing one parameter while the other is being kept constant during the tuning) to achieve our desired sets.

SNN-based robust filtering

The SNN-based filtering strategies SNN-KF and the robust method SNN-MSIF for linear systems18, and the SNN-EKF and SNN-EMSIF for nonlinear dynamical systems have previously been introduced19. Implementing a double linearization approach SNN-EMSIF combines the SNN with the EMSIF, a robust filtering strategy for nonlinear dynamical systems17. In this framework, SNN-EMSIF is represented as a recurrent SNN composed of leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons. Its weight matrices can adaptively change to emulate the dynamics of EMSIF, combining the computational efficiency and scalability of SNNs with the robustness of the EMSIF in the condition of neuron silencing. The equations governing SNN-EMSIF are as follows18:

where:

In the above equations, \(A = \frac{\partial f}{{\partial {\varvec{x}}}}\left. \right|_{{x = \hat{x}}}\), denotes the Jacobian matrix of the system dynamics, which is recalculated at every time step using the most recent state estimate \(\widehat{{\varvec{x}}}\). The synaptic weight matrices \({\Omega }_{s}\) and \({\Omega }_{f}\) correspond to the slow and fast connection pathways within the recurrent spiking network. The slow connections primarily encode the target system’s dynamics, thereby realizing the estimator, whereas the fast connections help maintain stable network behavior by promoting a balanced distribution of spikes among neurons. The parameter \(\lambda\) determines the leakage rate of each neuron’s membrane potential, influencing how rapidly the potential decays over time, while \(F\) transforms the control input into a spike-based signal interpretable by the SNN. Within this structure, the second set of three terms in Eq. (3) mainly contributes to the a priori prediction stage of the estimation process. In contrast, the following two terms associated with \({\Omega }_{k}\), and \({F}_{k}\) adapt continuously throughout operation and correspond to the measurement-update (a posteriori) stage. Specifically, \({\Omega }_{k}\) regulates the adaptive correction dynamics, whereas \({F}_{k}\) injects the encoded measurement information into the spiking network. The evolution of these weight matrices is expressed through the following update relations:

where, \(C = \frac{\partial h}{{\partial {\varvec{x}}}}\left. \right|_{{x = \hat{x}}}\) is the Jacobian of measurement system that needs to be updated at every time step using the most recent estimate of the system state \(\widehat{{\varvec{x}}}\), while \({P}^{zz}\) represents the innovation covariance matrix, and \(\delta\) is the sliding boundary layer, a tuning parameter which can be tuned by trial-and-error method. To update \({P}^{zz}\), the following equations are used:

The final term \({\varvec{\eta}}\) in Eq. (9) accounts for zero-mean Gaussian noise, simulating the stochastic nature of the neural activity in biological neural circuits. The weight matrices are analytically designed to capture EMSIF dynamics, allowing the estimation of a fully observable nonlinear dynamical system with partially noisy state measurements via a network of recurrent LIF neurons.

Utilizing the framework presented in this section for estimation concurrently with the conventional control methods results in the system depicted in Fig. 2. The figure illustrates how the conventional non-spiking estimator in Fig. 1 has been replaced by an SNN designed to function as an estimator. Instead of employing sequential estimation algorithms, this SNN-based approach capitalizes on the advantages of SNNs, including computational efficiency, highly parallel computing. However, as shown in Fig. 2, estimation and control tasks are still conducted sequentially.

SNN-based integrated estimation and control

This section extends SNN-EMSIF to a network capable of concurrently performing state estimation and control of dynamical systems. As introduced in18 and19, for the derivation of the SNN-EMSIF, which implements the dynamics of estimator EMSIF, the SNN should be able to mimic the following dynamics which is the fully linearized form of EKF through computing the Jacobians:

where \(B = \frac{\partial f}{{\partial {\varvec{u}}}}\left. \right|_{{x = \hat{x}}}\) is the Jacobian of the dynamic model with respect to input vector. Here, to go further and add the control to the above-mentioned dynamics; \({\varvec{u}}=-{K}_{c}({\varvec{x}} -{{\varvec{x}}}^{D})\) is considered as the control input, So, the network should emulate the following linear system of equations:

where \({{\varvec{x}}}^{D}\) denotes the desired state. To extend the previously introduced network, the control rule \({\varvec{u}}\) is substituted into Eq. (8), resulting in the following network equation:

Here, a decoding rule for the \({x}^{D}\) is considered as follows:

where \(\overline{D }\) is a fixed matrix generated from random elements sampled from a zero-mean Gaussian distribution. To effectively implement the added dynamics for \({{\varvec{x}}}^{D}\) in the network, referring to Eq. (3), an additional set of connections is introduced into the above equation14:

After simplifications, the resulting network equation is as follows:

where:

Here, \({\Omega }_{c}\) somehow represents the slow connections for implementing the control input of the desired system. \(\overline{\Omega }\), and \({\overline{\Omega } }_{f}\) represent the slow and fast synaptic weights for various connections respectively. parallel with other connections, these weights are responsible for implementing the dynamics of the desired state for the controller and Eq. (21) represents the membrane potential dynamics of a recurrent SNN of LIF neurons, capable of concurrently performing state estimation and control of linearized dynamical systems. While the controller gain \({K}_{c}\) must be designed for the considered system, this framework operates without requiring any learning by the network. Furthermore, although we implemented optimal LQR control in this study, controller gain can be independently designed using any arbitrary approach. Finally, to extract the control input vector for the external plant from the spike populations, the following equation is employed:

where:

The above matrix can be used to decode the control input from the filtered spike trains. In summary, the proposed framework integrates estimation and control processes simultaneously. It directly generates the control input \({\varvec{u}}\) for the dynamical system using a noisy and partially observed measurement vector \({\varvec{z}}\). So, this approach eliminates the need for a sequential process where the state \({\varvec{x}}\) is first estimated and then used to compute the control input \({\varvec{u}}\), thereby enhancing efficiency and responsiveness. Thus, we don’t even need to extract the estimated states for the control task unless in the cases in which we need to monitor the estimated states. Figure 3 illustrates the block diagram of the framework presented in this section.

Figure 3 demonstrates that for this framework, both the blocks of estimator and controller from Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 have been replaced by a single SNN. This represents an extension of the framework, leveraging the advantages of SNNs. Furthermore, the computations required for state estimation and control input have been parallelized. Consequently, implementing this framework can significantly reduce computational costs, allowing more complex tasks to be performed even with limited computing resources. Additionally, owing to the scalability of SNNs, if the network loses some of its neurons, the process continues by increasing the spiking rate of the remaining neurons, as demonstrated in the next section.

Numerical simulation

Here, to assess the performance and robustness of the proposed method, this section presents numerical simulations conducted on two representative systems under multiple uncertainty conditions. We first apply the proposed framework to a dynamical workbench problem and conduct various performance evaluations in terms of robustness, accuracy, and computational efficiency, in comparison with the well-established methods LQG and LQR-MSIF. Subsequently, we extend the analysis of the SNN-LQR-MSIF to a practical scenario involving the concurrent estimation and control of satellite rendezvous maneuvers. It is notable that, the two selected systems were chosen to evaluate both general applicability and real-world relevance of the proposed method. The first example—a generic second-order system with additive modeling uncertainties and measurement noise—serves as a controlled general benchmark to systematically evaluate the algorithm’s robustness, sparsity, and response to artificial perturbations. This abstraction allows direct comparison with traditional methods. The second scenario, satellite rendezvous, was selected due to its highly demand for a reliable and accurate estimation and control framework, as well as its practical constraints on computational and energy resources. It represents a real-world use case where neuromorphic efficiency, real-time responsiveness, and resilience to uncertainty are critical.

Case study 1: workbench dynamical system

Here, we initiate our investigation by applying the introduced framework to the following nonlinear dynamical system with a linear measurement:

where:

In general, for the controllable pair of \((A,B)\), the control law for the LQR controller is given by35:

Here, the symbol \(\widehat{{\varvec{x}}}\), denotes an estimated parameter. The controller gain \(K_{LQR}\) is designed to minimize the following cost function:

The weight matrices \({Q}_{c}\) and \({R}_{c}\) are determined through trial and error, with conditions \({Q}_{c}>0\) and \({R}_{c} \ge 0\) satisfied. The controller gain \({K}_{LQR}\) is calculated using the following equation:

where \(S\) is the unique positive semidefinite solution of the algebraic Riccati equation:

It is important to note that due to the linearity and time-invariance of the considered system (LTI), the gain matrix \({K}_{LQR}\) is computed offline and does not require updating during the maneuver. Moreover, based on the separation principle of linear systems theory, the obtained gain can be incorporated into our presented network without imposing any condition on the estimator. Simulations have been performed over a 10-s period with a time step of 0.01, employing the numerical values provided in Table 1.

Initially, we evaluated the applicability of the proposed framework in comparison with its non-spiking counterparts, LQG, and LQR-MSIF, by simulating a deterministic system without uncertainties. Next, we assessed the performance and effectiveness of the proposed framework by introducing various sources of uncertainties and disturbances. In line with real-world scenarios, where exact decoding matrices are typically unknown, we defined the decoding matrices \(D\) and \(\overline{D }\) using random samples from zero-mean Gaussian distributions with covariances of 0.25 and 1/300, respectively. Figure 4 displays time histories of controlled states and estimation errors within \(\pm 3\sigma\) bounds obtained from SNN-LQR-MSIF in comparison with LQG and LQR-MSIF. Figure 4(a) illustrates that the state \({x}_{1}\) converges to zero after \(t=5\) s, showcasing similar performance between the proposed framework and its non-spiking counterparts, LQG and LQR-MSIF. Figure 4(b) indicates that the state \({x}_{2}\) converges to zero around \(t=6\) s, again showing consistent performance between the proposed framework and non-spiking methods. Figure 4(c) demonstrates that all considered strategies remain stable, with errors staying within the prescribed bounds. Notably, the error obtained from KF deviates further from zero before converging around \(t=3\) s, while the errors from SNN-MSIF and MSIF exhibit faster convergence with smaller deviations. Figure 4(d) confirms the stability of all estimation methods, with SNN-LQR-MSIF showing nearly identical performance to non-spiking EKF and MSIF. This suggests that the predictive coding rule enables more timely correction in SNNs by emitting spikes only when the prediction error justifies it, leading to faster convergence with fewer computations.

Further, to gain more intuitive insights into the tuning parameters of the firing rule, namely \(\mu ,\) and \(\nu ,\) and their impacts on control accuracy, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. As depicted in Fig. 5, utilizing a colored map to show the variations of normalized average error, this analysis reveals that the tuning of firing rule parameters of the network directly affects control accuracy, and depending on the specific system, proper parameter sets can be identified by trial and error. The preferred parameter set used throughout our simulations is \(\mu =0.005\) and \(\nu =0.005\) (marked with a white circle in the figure). The percentage of emitted spikes by the neurons compared to all possible spikes is also shown in the figure by the numbers on the figure for each set of \(\mu\) and \(\nu\). It can be observed that decreasing \(\nu\) leads to a higher percentage of spikes compared to possible spikes for each \(\mu\). This highlights a trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency that can be an important factor in the tuning procedure of the network firing rule and confirms the previously mentioned matter about the tuning of \(\nu\) that controls the number of spikes.

Furthermore, we evaluated the robustness of SNN-LQR-MSIF against modeling uncertainties by introducing a 20% error in the dynamic transition matrix \(\widehat{A}=0.9A\). Simulation results in the presence of modeling uncertainty were compared with LQG and LQR-MSIF, as presented in Fig. 6. Figure 6(a) shows that in the presence of uncertainty, the SNN-based framework for the state \({x}_{1}\) deviates from non-spiking LQG and LQR-MSIF. However, SNN-LQR-MSIF exhibits superior performance, converging to zero at approximately \(t=4\) s and completely converging by \(t=6\) s. In contrast, non-spiking frameworks yield matching results converging to zero at \(t=7\) s. Figure 6(b) demonstrates that state \({x}_{2}\) exhibit similar deviation from non-spiking methods, particularly with a slightly greater overshoot and error until \(t=4\) s. However, after \(t=4\) s, SNN-LQR-MSIF displays faster convergence, a minor overshoot, and eventual convergence to zero after \(t=8\) s. In summary, these findings indicate that the proposed SNN-based framework exhibits commendable robustness in handling modeling uncertainties or external disturbances compared to non-spiking methods. Figure 6(c) illustrates the results for the state \({x}_{1}\), showcasing the performance of SNN-LQR-MSIF comparable to that of LQR-MSIF. Initially, both methods exhibit an error trend that diverges over time, exceeding the bound around \(t=1.5\) s but returning within the bounds by \(t=4\) s. Eventually, both methods achieve stable estimation, converging to zero around \(t=6\) s and \(t=8\) s for SNN-MSIF and MSIF, respectively. Meanwhile, the error from KF deviates entirely and its error has returned to the bound in almost \(t=8\) s and finally, it converged to zero at \(t=10\) s. Notably, at \(t=6\) s, KF exhibits an error that is approximately 20 times greater than the error obtained for the proposed SNN-LQR-MSIF is almost near zero. In Fig. 6(d), the results for the state \({x}_{2}\) show nearly identical performance between SNN-MSIF and MSIF, both maintaining stability in their estimations throughout the considered period. Conversely, the error from KF deviates similarly to what occurred with the state \({x}_{1}\). The obtained error for KF has exceeded the bound and has risen continually until almost \(t=2.5\) s reaches its maximum which is about 102 times greater than the obtained error for MSIF and SNN-MSIF is also approximately near to zero. Hence, it is evident that SNN-MSIF outperforms MSIF by faster convergence to zero in the presence of uncertainty, and it outperforms KF in terms of estimation stability. Thus, the results give us two different interpretations. First, compared to the standard LQG, the faster convergence of the LQR-MSIF confirms the robustness of the method in dealing with bounded modeling uncertainties because it is benefiting from the robust nature of the MSIF filter. Then, faster convergence of SNN-based method compared to its algorithmic version suggests that the predictive coding rule enables more timely correction in SNNs by emitting spikes only when the prediction error justifies it, leading to faster convergence with fewer computations.

An important challenge in robust navigation and control systems is handling measurement outliers, which can arise from sensor faults or external disturbances in the working environment. Therefore, to assess the framework’s robustness in such scenarios, unmodeled measurement outliers were introduced into the system at \(t=3\) s, \(t=5\) s, and \(t=6\) s. To simulate the presence of measurement outliers, the measurement system noise was multiplied by a factor of 500 at these time points. Figure 7 presents a comparison of results for controlled states and estimation errors within \(\pm 3\sigma\) bounds obtained from various frameworks in the presence of measurement outliers. Figure 7a displays the time history of the state \({x}_{1}\). It demonstrates that the presence of measurement outliers causes slight deviations in the results obtained from the SNN-based framework between \(t=3\) s, and \(t=7\) s. However, the framework successfully regulates the error, ultimately converging to results obtained from non-spiking methods. Figure 7b demonstrates the same behavior for the state \({x}_{2}\). Results from the SNN-based framework show minor deviations compared to non-spiking methods between \(t=3\) s, and \(t=7\) s, indicating that, although more sensitive to measurement outliers, the SNN-based methods continue to control the states effectively. Figure 7c presents the obtained errors for the state \({x}_{1}\), which exhibit significant deviations at the points of outlier injection. However, for all considered filters, these deviations are followed by rapid convergence to zero, confirming the filters’ stability. Moreover, the error from SNN-MSIF is considerably smaller, especially compared to KF which exceeds the bound on all points. In Fig. 7d, we investigate the error for the state \({x}_{2}\) which reveals when KF experiences abrupt deviation and its error exceeds the bound at the points of outlier injection, whereas SNN-MSIF and MSIF remain stable throughout the simulation. Thus, SNN-MSIF exhibits superior robustness in such situations. Furthermore, meanwhile the results here reconfirm the previous interpretations, the better performance of the SNN-based method in terms of faster convergence and lower error divergence while it is encountering with outliers, shows that the SNN-based method is more adaptable in such conditions because it is benefiting a dynamic adjustment of the computation in the SNN (changing the spiking rate and neurons activation demonstrated in Fig. 8) based on the incoming error. Thus, the proposed method can have an acceptable responsivity in dealing with such situations. Figure 8 illustrates the spiking pattern of the network achieved by the SNN-LQR-MSIF approach when confronted with measurement outliers. In Fig. 8a, we present the spiking pattern recorded in the presence of measurement outliers. It is evident that just right before the points of outlier injections (at time steps 300, 400, and 600), most neurons are in standby mode, emitting a few spikes. However, after the injection of outliers, a substantial portion of neurons (around 40%) become activated to handle the injected disturbances, that are rejected within just 2–3 time steps. The neural activity then decreases, demonstrating that the network effectively overcomes external disturbances or unmodeled dynamics by increasing neural activity or computational cost without failing in the assigned task. Moreover, Fig. 8(b) reveals the temporal variation of active neurons in percent, emphasizing the sudden change in the population of active neurons at the designated time steps. The population rises to nearly 40% to overcome the negative impacts of injected outliers on the system.

Finally, to assess the proposed framework’s performance in situations where some neurons may become silent, several simulations were conducted with varying numbers of neurons, ranging from \(N=50\) to \(N=400\) in the step of 50 neurons. Figure 9 presents the average overall network error in the controlled states after \(t=6\) s (where the errors almost converged to zero) versus the number of neurons. In Region 1, a significant error divergence to infinity is observed (the solid line which shows the error variation became almost vertical at the edge of Region 1) while this error is abruptly decreased at \(N=100\). This corresponds to the minimum number of neurons that the proposed framework requires to function effectively. Below this threshold, active neurons cannot provide sufficient neural activity to perform the necessary computations. An increase in the number of neurons within region 2 results in a gentle reduction in error. The minimum error can be observed at the optimal number of neurons at \(N=250\). In contrast, region 3 shows that an increase in the number of neurons degrades accuracy due to unstable spiking patterns with excessive neural activity. It is notable that because of the similarity, to avoid the repetitive figures, in this study, just the spiking pattern of the scenario with outlier injection has been investigated.

Furthermore, to have an assessment of the computational burden of the proposed framework by increasing the number of neurons (increasing the network size), runtime analysis has been done for the different \(N\) and the obtained results have been compared in Table 2. To this aim, multiple simulations in MATLAB code environment on a computer utilizing M4-Pro chip and 48 GB of memory have been conducted. The obtained results demonstrate that increasing the network size has a direct effect on the computational burden.

Overall, the proposed framework exhibits remarkable robustness in handling measurement outliers and effectively adapts to situations with varying numbers of neurons, provided a minimum neuron threshold is maintained. These findings support the framework’s suitability for robust navigation and control systems in real-world scenarios. Further studies on spiking patterns are provided in18. On the other hand, the proposed SNN-LQR-EMSIF achieves \(O({n}^{2}+pn)\) complexity compared to \(O({n}^{2.376}+m{n}^{2})\) for traditional LQG methods36. This efficiency stems from event-driven sparse processing inherent to SNNs37, eliminating continuous matrix operations.

Case study 2: satellite rendezvous maneuver

This section is initiated by the presentation of the mathematical model for the satellite rendezvous maneuver. Subsequently, the design of the LQR controller is expounded upon. Lastly, the simulation results are provided. The rendezvous problem involves maneuvering two distinct satellites, the chaser, and the target. As depicted in Fig. 10, the chaser satellite approaches the target in orbit.

Schematic of rendezvous maneuver38.

To derive the equations of relative motion, we consider the following equation in the Earth-centered inertial frame (ECI)39.

Here, \({{\varvec{r}}}_{c}\) and \({{\varvec{r}}}_{t}\) represent the position vectors of the chaser and target, respectively. The relative acceleration is described by the following expression:

Meanwhile, considering the circular orbit, the gravitational force in ECI is expressed as:

Here, \({\mu }_{earth}\) signifies the Earth’s gravitational parameter, \(m\) denotes spacecraft mass, and \({\varvec{r}},\) and \(r\) represent the spacecraft position vector and its magnitude, respectively. Importantly, the absolute motion of both the chaser and target in the ECI frame can be separately formulated as follows:

The above equations represent normalized forms of Eq. (32), divided by the spacecraft mass. To formulate suitable equations for controller design, it is advantageous to represent relative motion in the target frame, a non-inertial reference frame rotating with the angular velocity, \({\varvec{\omega}}\).

Here, \({\varvec{s}}\) denotes relative distance, \(M,\) and \({\varvec{f}}\) refer to Earth’s mass and external forces, respectively, and the asterisk (*) denotes parameters in the target frame. The linearized form of Eq. (35) in the target frame, known as the Clohessy-Wiltshire (CW) equations, is expressed as39:

where:

Here, \({R}_{o}\) represents the orbital radius of the target spacecraft, and \(n\) is the mean motion. To design the LQR controller, we begin by defining the state and input vectors as \({\varvec{x}}={\left[x,y,z,\dot{x},\dot{y},\dot{z}\right]}^{T}\), and \({\varvec{u}}=[{f}_{x},{f}_{y},{f}_{z}]\), respectively. Subsequently, we derive the state space form of CW equations, expressed as:

where:

The simulations in this section are conducted using the numerical values provided in Table 3, with a time duration of 360 s and a time step of 0.05. Additionally, the decoding matrices \(D\) and \(\overline{D }\) are defined using random samples from zero-mean Gaussian distributions with covariances of 1/50, and 1/2500, respectively.

Figure 11 presents a comparison between SNN-LQR-MSIF and non-spiking LQG and LQR-MSIF in the context of the rendezvous maneuver problem. Each element of the system’s state vector is individually compared. The results demonstrate that all considered frameworks successfully control the states, with errors smoothly converging to zero. Moreover, it is evident that the proposed SNN-based framework exhibits similar performance in controlling the states, aligning with the results obtained from the optimal non-spiking framework LQG. Notably, for states \(z\), and \({v}_{z}\), some discrepancies are observed. For state \(z\), the SNN-LQR-MSIF exhibits a slightly greater overshoot compared to non-spiking LQG and LQR-MSIF, but ultimately successfully controls the state error to zero. Furthermore, for state \({v}_{z}\) the result from SNN-LQR-MSIF exhibits minor deviation from non-spiking frameworks between \(t=100\) s and \(t=200\) s. To provide quantitative insight into this comparison, average errors obtained from different methods after \(t=300\) s are presented in Table 4. The results reveal that non-spiking methods deliver consistent accuracy, and the SNN-based method demonstrates acceptable accuracy. In summary, compared to traditional non-spiking frameworks like LQG and LQR-MSIF, the achieved results for controlled states affirm the acceptable performance of SNN-LQR-MSIF for the problem of satellite rendezvous, a critical maneuver in space robotic applications.

Figure 12 compares the obtained control inputs for different control approaches. Comparisons demonstrated that while the control inputs for the non-spiking methods coincide together, the obtained control inputs for the SNN-LQR-MSIF for the \({f}_{x}\) and \({f}_{z}\) have tracked the control inputs obtained for LQG and LQR-MSIF, but for \({f}_{y}\) the obtained input from SNN-LQR-MSIF has started with a deviation with respect to the other methods before \(t=25\) s, and then it has almost converged to the inputs obtained from the non-spiking methods. On the other hand, from a closer perspective obtained results for the SNN-based method have negligible fluctuations which can be the source of the deviations in the controlled states in Fig. 11.

To assess the computational efficiency of the SNN-based framework relative to conventional artificial neural networks (ANNs), we delve into the spiking pattern generated by the designed SNN, as showcased in Fig. 13(a). This vividly illustrates the network’s efficient execution of its task. Upon closer examination, as depicted in Fig. 13(b), during the initial 2000 time-steps (before \(t=100\) s), when state-vector errors are sizable, the network exhibits heightened neural activity, with approximately 20% of neurons being active. Subsequently, the population of active neurons gently declines and remains relatively constant, with minor fluctuations hovering around 5% for the remainder of the simulation. In essence, the network accomplishes its task while utilizing a mere 2.4% of possible spikes over the entire simulation duration, in stark contrast to traditional ANNs that consume 100% of potential spikes. This underscores the computational efficiency of SNN-LQR-MSIF in simultaneously handling estimation and control for satellite rendezvous.

Moving on to assess the robustness of the SNN-LQR-MSIF against modeling uncertainties, we introduce a 10% error into the dynamic transition matrix \(\widehat{A}=0.9A\) used within the framework. Figure 14 demonstrates the results for controlled states using the aforementioned strategies in the presence of uncertainty. This figure underscores that SNN-LQR-MSIF exhibits higher sensitivity to modeling uncertainties compared to non-spiking strategies. However, it also presents that SNN-LQR-MSIF effectively controls the system, with all the errors gracefully converging to zero. Furthermore, Table 5 presents average errors obtained from controlled states after \(t=300\) s, verifying the findings depicted in Fig. 14.

To further evaluate the robustness of SNN-LQR-MSIF against external disturbances, such as instability in the working environment, we introduce measurement outliers. This scenario is configured so that unmodeled measurement outliers are injected into the system at \(t=100\) s, \(t=150\) s, and \(t=200\) s. Notably, to introduce the outliers at these time steps, the measurement system noise is scaled by a factor of 200. Figure 15 illustrates the results for various frameworks in this scenario. Similar to modeling uncertainties, it reveals that the SNN-LQR-MSIF is more sensitive to measurement outliers compared to non-spiking strategies. However, it effectively maintains control, with all errors converging to zero.

Figure 16 provides insight into the spiking pattern of SNN-LQR-MSIF in the presence of measurement outliers. In Fig. 16(a), the network reacts to disturbances by increasing the number of active neurons, rapidly rejecting disturbances in just 2–3 time steps. Figure 16(b) quantifies this by depicting the variation in the population of active neurons in percentage terms. The figure highlights a significant increase in the proportion of active neurons, rising from approximately 10% to nearly 50%. Figure 17 shows the comparison between the obtained control input from the SNN-based strategy and the non-spiking counterpart compared to the standard LQG. although the results demonstrate an approximately good coincidence between the obtained results from the various methods, the obtained control inputs for the SNN-based strategy have considerable jumps in their values on the time steps when the outliers are injected to the system, similar to the increase in the neural activity in the network, which shows the increase in the control effort to damp the external disturbances.

Corresponding averaged errors from the controlled states after \(t=300\) s is presented in Table 6, thus reinforcing the insights gleaned from the data depicted in Fig. 15.

Here, results obtained in this section affirm that the framework proposed in this study demonstrates computational efficiency for such problems. Compared to traditional computing strategies like LQR-MSIF and LQG, it exhibits good and comparable performance in terms of robustness and accuracy. While the proposed SNN-LQR-MSIF framework demonstrates promising performance in terms of computational efficiency, robustness, and accuracy, it is important to acknowledge and discuss the inherent trade-offs among these metrics. Specifically, in scenarios involving significant modeling uncertainties or injected measurement outliers, the SNN-based method may exhibit slightly higher estimation errors or transient control deviations compared to its non-spiking counterparts. This is largely due to the sparsity-driven firing rule, which reduces computational burden by limiting spike activity. However, this may lead to under-representation of subtle state variations in highly dynamic environments, thus impacting accuracy. On the other hand, robustness is retained through the predictive coding mechanism and the use of EMSIF-inspired network dynamics, which stabilize performance in the presence of disturbances or neuron silencing. These trade-offs are governed primarily by the firing rule parameters \(\nu\) and \(\mu\) which must be tuned to balance spike sparsity (efficiency) with responsiveness and network activation (accuracy and robustness). A discussion of this trade-off space is illustrated in Fig. 5, where an ideal region for parameter selection is identified there by trial-and-error. Furthermore, for having a comparison between the proposed method in this study with other learning-based neuromorphic methods, we compared the obtained results from our first simulation case here (simulation without uncertainties for satellite rendezvous reported in Table 4) with the same scenario for the satellite rendezvous introduced in our previous works11, that uses a learning-based neuromorphic controller. Table 7 compares the obtained accuracy for the different approached implemented.

Comparison of the obtained results shows the acceptable accuracy of the proposed method for the same scenario compared to the learning-based approach. Though learning-based methods offer adaptability and online learning capabilities but often come with increased complexity, training costs, and reduced interpretability. Moreover, many learning-based controllers are heavily relying on their learning frameworks and techniques, which may require careful hyperparameter tuning and extensive training time or may cause delay in online inference because of computational resource overhead. In contrast, the framework proposed in this study offers a learning-free alternative that is analytically derived from the dynamics of robust filtering and control. By eliminating the need for training while still leveraging the energy efficiency and scalability of SNNs, our method achieves comparable or superior robustness with significantly reduced computational overhead, especially in edge or resource-constrained environments. This positions our approach as a viable solution for real-time control applications where reliability and computational efficiency are critical. Thus, it can be deduced that the method proposed in this study can be a good candidate for learning-free neuromorphic approach for integrated estimation and control. Finally, it is notable that, while the SNN-LQR-EMSIF framework exhibits slightly higher errors in certain state estimates compared to the LQR-MSIF, these differences are both explainable and acceptable within the context of real-time neuromorphic processing. The observed deviations can be attributed to the discrete, event-driven nature of spiking computation, where state updates occur only when the prediction error become considerably large for faster charge of membrane potential of the LIF neurons. In contrast, LQR-MSIF, operating on continuous signal updates, can react more smoothly but at the cost of higher computational burden. Importantly, considering the acceptable accuracy, the SNN-based method maintains stable convergence and system behavior, and its robustness under uncertainty and resilience to measurement outliers often exceed those of LQR-MSIF. Moreover, the trade-off introduced by SNN’s sparse activity results in significantly reduced computational load—favorable for embedded and space applications where resources are limited.

Conclusion

In the presented study, we have dived into the crucial challenges of concurrent estimation and control within dynamical systems, underscoring its paramount importance. As the complexity and safety considerations associated with mission-critical tasks continue to intensify, the demand for computationally efficient and dependable strategies has become increasingly imperative. Moreover, in the real-world application landscape, encountering uncertainties such as environmental instability, external disturbances, and unmodeled dynamics, the call for robust solutions capable of navigating these challenges is resounding. Thus, we proposed an efficient approach grounded in biologically plausible principles. Our framework harnessed the potential of a recurrent spiking neural network (SNN), composed of leaky integrate-and-fire neurons, bearing resemblance to a linear quadratic regulator (LQR) enriched by the state estimation of a modified sliding innovation filter (MSIF). This innovative approach, SNN-LQR-MSIF combines the robustness inherited from the MSIF, while concurrently infusing it with computational efficiency and scalability inherent in SNNs. Importantly, the elimination of the need for extensive training, owing to spike coding theories, empowered the design of SNN weight matrices grounded in the dynamic model of the target system. Further, the SNN-LQR-MSIF approach has been analyzed under various uncertainties, such as modeling errors, measurement outliers, and occasional neuron silencing. Also, it has been compared with its non-spiking counterpart, LQR-MSIF, and the well-known linear quadratic Gaussian (LQG) method. Our evaluation included both standard linear problems and the satellite rendezvous maneuver, a critical task in space robotics. The results showed that SNN-LQR-MSIF performed well, offering advantages in computational efficiency, reliability, and accuracy. This makes it a promising solution for simultaneous estimation and control. Looking ahead, we aim to develop learning-based methods that combine SNNs with predictive coding for robust estimation and control. These future advancements could further improve control and estimation in dynamical systems.

Future work will focus on validating the proposed method in real-world hardware platforms. Due to its sparse firing activity, learning-free structure, and modular design, the SNN-LQR-EMSIF framework is well-suited for implementation on neuromorphic chips such as BrainChip Akida or Intel Loihi. We plan to conduct hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experiments to assess performance under real-time constraints and sensor interface integration. In parallel, future work will aim to adaptively tune the firing rule parameters based on the operational environment to dynamically optimize the balance between robustness, accuracy, and computational efficiency. These developments are critical steps toward demonstrating the practical viability of the proposed neuromorphic estimation and control system in edge computing and onboard robotic platforms.

Data availability

The code and data generated or analyzed during this study are available in the GitHub repository: https:/github.com/INQUIRELAB/neuromorphic-integrated-control.

References

Liu, Y., Wang, S., Xie, Y., Xiong, T. & Wu, M. A review of sensing technologies for indoor autonomous mobile robots. Sensors 24(4), 1222 (2024).

Slade, P., Culbertson, P., Sunberg, Z. & Kochenderfer, M. Simultaneous active parameter estimation and control using sampling-based Bayesian reinforcement learning. In 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 804–810 (2017).

Espinoza, A. T. & Roascio, D. Concurrent adaptive control and parameter estimation through composite adaptation using model reference adaptive control/Kalman Filter methods. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA) 662–667 (2017).

Sadeghvaziri, E., Javid, R., Omidi, H. & Arafat, M. A machine learning approach to understanding sociodemographic factors in electric vehicle ownership in the US. Sustainability 16(23), 10202 (2024).

Doina, Z. M. LQG/LQR optimal control for flexible joint manipulator. In 2012 International Conference and Exposition on Electrical and Power Engineering 35–40 (2012).

Wang, W., Chen, X., Yin, X. & Song, Y. Optimal LQG control based on the prediction for a robot system over wireless network. In 2011 International Conference on Electric Information and Control Engineering 3406–09 (2011).

Van Den Berg, J., Abeel, P. & Goldberg, K. LQG-MP: Optimized path planning for robots with motion uncertainty and imperfect state information. Int. J. Robot. Res. 30(7), 895–913 (2011).

Tayebi, J., Nikkhah, A. A. & Roshanian, J. LQR/LQG attitude stabilization of an agile microsatellite with CMG. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 89(2), 290–296 (2017).

Lee, K., Joen, S., Kim, H. & Kum, D. Optimal path tracking control of autonomous vehicle: Adaptive full-state linear quadratic Gaussian (LQG) control. IEEE Access 7, 109120–109133 (2019).

Alandoli, E. A. & Lee, T. S. A critical review of control techniques for flexible and rigid link manipulators. Robotica 38(12), 2239–2265 (2020).

Schwenzer, M., Ay, M., Bergs, T. & Abel, D. Review on model predictive control: an engineering perspective. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 117, 1327–1349 (2021).

Bagheri, A., Cabral, T. O. & Pourkargar, D. B. Integrated learning-based estimation and nonlinear predictive control of an ammonia synthesis reactor. AIChE J. 71(5), e18732 (2025).

Schuman, C. D. et al. Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2(1), 10–19 (2022).

Slijkhuis, F. S., Keemink, S. W. & Lanillos, P. Closed-form control with spike coding networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.12887 (2022).

Ahmadvand, R., Sharif, S. S. & Banad, Y. M. A cloud-edge framework for energy-efficient event-driven control: An integration of online supervised learning, spiking neural networks and local plasticity rules. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.02316 (2024).

Ahmadvand, R., Sharif, S. S. & Banad, Y. M. Efficient brain-inspired control strategies: Cloud-based online supervised learning for spiking neural networks in dynamical systems. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. (2024).

Kiani, M. & Ahmadvand, R. The strong tracking innovation filter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 58(4), 3261–3270 (2022).

Ahmadvand, R., Sharif, S. S. & Banad, Y. M. Enhancing energy efficiency and reliability in autonomous systems estimation using neuromorphic approach. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.07963 (2023).

Ahmadvand, R., Sharif, S. S. & Banad, Y. M. Neuromorphic robust estimation of nonlinear dynamical systems applied to satellite rendezvous. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.08392.

Gadsden, S. A. & Al-Shabi, M. The sliding innovation filter. Sliding Innov. Filter 8, 96129–96138 (2020).

Habibi, S. The smooth variable structure filter. Proc. IEEE 95(5), 1026–1059 (2007).

Gadsden, S. A. Smooth variable structure filtering: Theory and applications, Department of Mechanical Engineering, McMaster University, Doctoral dissertation (2011).

Boerlin, M., Mchanes, C. K. & Deneve, S. Predictive coding of dynamical variables in balanced spiking networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9(11), e10032–e10058 (2013).

Schuman, C. D. et al. A survey of neuromorphic computing and neural networks in hardware. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.06963 (2017).

Alemi, A., Machens, C., Deneve, S. & Slotine, J. J. Learning arbitrary dynamics in efficient, balanced spiking networks using local plasticity rules. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.08026 (2017).

Alemi, A., Machnes, C., Deneve, S. & Slotine, J. J. Learning nonlinear dynamics in efficient, balanced spiking networks using local plasticity rules. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence vol. 32, no. 1 (2018).

Eshraghian, J. K. et al. Training spiking neural networks using lessons from deep learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.12894 (2021).

Yamazaki, K., Vo-Ho, V. K., Bulsara, D. & Le, N. Spiking neural networks and their applications: A review. Brain Sci. 12(7), 863 (2022).

Fekrmandi, H., Colvin, B. P., Sargolzaei, A. & Banad, Y. M. A model-based technique for fault identification of sensors in autonomous systems using adaptive neural networks and extended Kalman filtering. In SPIE Health Monitoring of Structural and Biological Systems XVII Vol. 12488 372384 (2023).

Khoshavi, N. et al. Shieldenn: Online accelerated framework for fault-tolerant deep neural network architectures. In 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC) 1–6 (2020).

Roohi, A., Angizi, S., Fan, D. & DeMara, R. F. Processing-in-memory acceleration of convolutional neural networks for energy-efficiency, and power-intermittency resilience. In 2019 International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED) 8–13 (2019).

Lemaire, E. et al. An analytical estimation of spiking neural networks energy efficiency. In International Conference on Neural Information Processing 574–587 (2022).

Deng, L. et al. Rethinking the performance comparison between SNNS and ANNS. Neural Netw. 121, 294–307 (2020).

Flores-Abad, A., Ma, O., Pham, K. & Ulrich, S. A review of space robotics technologies for on-orbit servicing. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 68, 1–26 (2014).

Okyere, E., Bousbaine, A., Poyi, G. T., Joseph, A. K. & Andrade, J. M. LQR controller design for quad-rotor helicopters. J. Eng. 2019(17), 4003–4007 (2019).

Grewal, M. S. & Andrews, A. P. Kalman Filtering: Theory and Practice with MATLAB (Wiley, 2014).

Davies, M. et al. Loihi: A neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning. IEEE Micro 38(1), 82–99 (2018).

Ahmadvand, R., Sharif, S. S. & Banad, Y. M. Neuromorphic robust framework for concurrent estimation and control in dynamical systems using spiking neural networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03873.

Arantes, G. & Martins-Filho, L. S. Guidance and control of position and attitude for rendezvous and dock/berthing with a noncooperative/target spacecraft. Math. Problems Eng. (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A. conceived the original idea, developed the theoretical framework, conducted the mathematical derivations, implemented the numerical simulations, and drafted the manuscript. S.S.S. contributed to the validation of results and assisted with manuscript review and preparation. Y.M.B. supervised the research, provided feedback on the theoretical framework, guided the methodology, validated the results, and contributed to the final manuscript revision. All authors discussed the results, contributed to the interpretation of data, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmadvand, R., Sharif, S.S. & Banad, Y.M. Neuromorphic robust framework for integrated estimation and control in dynamical systems using spiking neural networks. Sci Rep 15, 44753 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28344-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28344-4