Abstract

Image data has been generated massively by devices in medical imaging modalities, cameras, and even by artificial intelligence. Encryption is the powerful method to keep the image content confidential, in which an encryption algorithm must include the confusion and diffusion properties. For massive images, a efficient method of encryption must be chosen to meet the demands of encryption speed and confidentiality. So far, chaos-based image encryption has been an active topic of research because it is considered an effective method to remove the correlation in image data as well as to keep confidential by the involvement of chaotic system in the encryption process. Besides, multiple image encryption algorithms encrypt multiple images in parallel, and it provides highly efficient performance in term of speed if it is implemented on a parallel computing platform such as multiple core processing as well as digital hardware design. Chaos-based multiple image encryption is constructed by integrating a chaotic system into multiple image encryption. Recently, many algorithms of chaos-based multiple image encryption have been proposed, and they are proved to have high efficient in terms of both speed and confidentiality. However, all the existing algorithms of chaos-based multiple image encryption require images of the same size and of the same number of bits representing pixels. Further, they encrypt a cohort of plain images at the same time, and all ciphertext images of a cohort must also be decrypted at the same time. It means that if it does not allow to decrypt one or some selected ciphertext images from a cohort separately; and as a result, it wastes time and energy to decrypt unwanted images. In this paper, three novel structures of chaos-based multiple image encryption are proposed which overcome the drawbacks of existing algorithms. That is, the proposed cryptosystems accept cohort images of different sizes; pixels of images can be represented by different numbers of bits; and any selected ciphertext images from a cohort can be decrypted separately. The security is improved by using the session keys of image-content dependency. The proposed structures of multiple image encryption consist of permutation, substitution, and diffusion processes. The difference between three structures is the order of such processes. A perturbed chaotic map and a linear-feedback shift register are employed to generate pseudo-random bit sequences for session keys. The simulation results for the exemplar designs using the proposed structures show the effectiveness by means of the statistical analysis for the session keys using the NIST randomness test, information entropy, histogram, and correlation coefficients of adjacent pixels in ciphertext images, and security analysis by means of space and sensitivity of the secret key. The hardware implementation on the FPGA platform demonstrates the feasibility of the proposed structures by means of throughput and hardware efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, modern devices such as cameras, medical imaging modalities, and even artificial intelligence generate massive images. In order to keep image data confidential, encryption algorithms must be efficient in terms of speed and confidentiality in the context of massive images. So far, chaos-based image encryption is considered an effective method to remove the correlation in image data as well as to keep confidential by the involvement of chaotic system in the encryption process.

Since R. Matthews introduced the first chaos-based encryption1, many structures and algorithms have been proposed for chaos-based image encryption. In the early stage of development, a chaotic system was used as a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) and chaotic values were mixed with image data to obtain ciphered images, for example2,3. In the next stage of development, chaotic systems were utilized in structured cryptography models, i.e., substitution-permutation networks (SPN)4 and Feistel networks5. Recently, chaos has also been used with other techniques to construct chaotic image encryption, e.g., DNA encoding6,7 and quantum8,9. However, most of the existing chaotic encryption have dealt with a single image, namely single image encryption (SIE), e.g.,10,11.

Rather than SIE, more efficient performance is achieved by multiple image encryption (MIE), in which multiple images, called a cohort, are encrypted simultaneously. Since 2005, MIE has been implemented in the optical domain12,13,14,15,16, and in the digital data domain, for example17,18. After the first chaos-based MIE was introduced19, many works on MIE have been reported, for example6,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The input of chaos-based MIE algorithms is multiple images and multiple ciphertext images are achieved at the output. So far, there are several approaches to chaos-based MIE algorithms, and they are categorized based on different purposes, i.e., parallelism, techniques, image-content dependency, and structural configuration. In the following literature review, these approaches are considered only for chaos-based MIE.

-

Parallelism: The purpose of designing with parallelism operations is to strive for high speed when it is implemented on parallel computing platforms such as multiple core computing or digital hardware. With respect to the level of parallelism, chaos-based MIE algorithms can be categorized into three groups depending on the processing progress of pixels from images of a cohort being encrypted. The first group of chaos-based MIE algorithms has the lowest level of parallelism, in which all original images are merged to become a large image, then the data of the big image are encrypted pixel by pixel sequentially throughout the big image. For example, the algorithm in22,24,32,33,34 is completely sequential, in which all original images are merged, and then permutation and diffusion are performed pixel by pixel through the big image. The encryption scheme in34 is the kind of lowest level of parallelism, in which four RGB images are merged before permutation and substitution for pixels of the big image. The second group of chaos-based MIE algorithms has the highest level of parallelism, e.g.7, in which pixels at the same locations from all original images are encrypted with the same progress. For example, the algorithm in28,29 is completely parallel if the intra-image permutation scheme is used. The third group of chaos-based MIE algorithms has a moderate level of parallelism, in which some encryption processes of algorithms can be implemented in parallel, and some others are performed sequentially, e.g.23,31,35,36. For example, in Karawia23, multiple original images with the same size and the same pixel depth are merged to become a big image; then small pieces of images that are divided from the big image are shuffled with each other; after that, small pieces of images are converted into binary vectors, which are scrambled by XORing with binary vectors obtained by chaotic values; scrambled pieces of image are merged to become the big image, before all pixels are shuffled in the range of the big image; the big image is divided into images of the same size of original images. In practice, only the step where small pieces of images are scrambled by XORing with binary vectors generated by the chaotic map can be performed in parallel, while the shuffling operations of small pieces of images and of pixels must be implemented sequentially.

-

Techniques: So far, many techniques have been used in the design of chaos-based MIE. Techniques is of variety, ranged from cellular automa (CA), transforms to the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and others. The technique is used with the purpose to to ensure the security, that is, to improve with the confusion and diffusion properties for chaos-based MIE. First of all, the cellular automa in22 is used for generating rules for the permutation process which changes the permutation key from a pixel to pixel by means of their indexes. Secondly, in the DNA technique, bits are mapped by the rules of based pairing37 by four DNA bases, i.e. Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C), and there are eight sets of encoding and decoding rules38. Accordingly, the computing operations based on DNA such as XOR, addition, and subtraction, are employed for the permutation and diffusion processes6,7,22,25,39,40. After that, the image data in the DNA bases are decoded to represent image in binary. In fact, the DNA technique is a form of binary image encryption, but it deals with groups of two bits. Thirdly, in the technique with transforms, image data is converted into transform domains and the encryption process is performed on the data in the transform domains. Then, the encrypted data is inverse transformed to obtained ciphertext images. Several transforms are used for this purpose, i.e., discrete fractional random transform20,40,41, Rubik cube transform40,42, discrete fractional cosine transform43,44, discrete cosine transform32,45, fractional discrete Fourier transform46,47, Krawtchouk fractional transform48, fractional Hartley transformation35, etc. However, some techniques are complicated and slow down the encryption process. For example, the transform requires a lot of computational effort, so it is not suitable for encryption with high-speed priority. The most speed is achieved when the permutation is performed in spatial domain and the diffusion process is carried out with pixel values.

-

Image-content dependency: In most existing chaos-based MIE algorithms, the private key and session key are independent from the image content. Recently, there are some schemes of chaos-based MIE that are designed so the the image content is involve in the generation of the keys. There are several two main categories, i.e., secret key of image-content dependency and session keys of image-content dependency. As the first approach, the secret key of image-content dependency is the simplest way, in which some values are computed from the image, e.g. hash values, and used as the secret key. It is is kept constant during encryption. For example, the initial values and/or parameters of chaotic map are hashed values of plaintext images26,27,33,36,40,42,49,50. With this way, the secret key at the encryption side must be sent to the decryption side for each plaintext image. This creates the problem in the key management. In the second approach, the session keys are generated and dependent on the image content of intermediate ciphertexts during the encryption. In fact, the orbit of chaotic map is regularly perturbed by pixel values of intermediate ciphertext image while it produces the session keys as presented in28,40,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. However, most existing algorithms with the session keys of image-content dependency were designed for the chaos-based SIE. To the best our knowledge, there is only one algorithm presented in29 being for the chaos-based MIE. In summary, the image encryption with image-content dependency provides superior security, especially for the session keys of image-content dependency, because the encryption is sensitive to changes in the plaintext and ciphertext, in other words, it can resist from the plaintext- and ciphertext-related attacks. In addition, the session keys of image-content dependency requires more computation than the secret key of image-content dependency, so it is only suitable for the encryption algorithms that are implemented in the parallel computing platform.

-

Structural configuration: So far, there are two main architectures of chaos-based MIE. The first one is based on the substitution-permutation networks (SPN) and the second one is the Feistel structure5. Most of algorithms of chaos-based image employs the SPN, and very few schemes use the Feistel structure58,59,60. For the SPN, the substitution provides the confusion property by a substitution box (S-box) while the diffusion property is achieved by the permutation process. It is well known that the S-box is very simple but it makes the encryption resisted from most typical attacks. Most of existing algorithms of chaos-based encryption, that are successfully analyzed, are of permutation-diffusion structure, and are without any S-box61,62,63,64,65. This means that the permutation-diffusion structure does not provide strong security enough, and an S-box should be included in the image encryption algorithm. In addition, one of the weakness in most existing chaos-based MIE algorithms is that they are designed for performing only a single round of encryption, e.g.7,23,25,49. It is known that the combination of diffusion and permutation has been proved efficient in saving time for chaotic iterations as presented in33,66,67 but, there are few chaos-based MIE algorithms designed using the combination of diffusion and permutation29,33. Besides, most of existing chaos-based MIE algorithms are with the structures that limit themselves to the number of grayscale images with the same size to be encrypted, i.e., two19,20,32, three7,35,39,42,46,48,68, six40,41,44, twelve34, and multiple24,26,27,33,36,47,49,50. In case of different sizes, the plaintext images are required to reshape or pad pixels to become the same size before being encrypted. It needs overhead time to reshape and pad additional pixels. It also wastes time and energy to encrypt, and decrypt padded pixels. In practice, there are some areas of applications such as medical imaging modalities69, aerial imagery70, etc, in which various types of images are of different sizes and different pixel depths. Even the encryption scheme presented in 33 allows multiple images of a cohort with any sizes, it does not accept variety of pixel depths and it encrypts images sequentially, but not in parallel.

In summary, existing chaos-based MIE algorithms still suffer from limited security, performance, and generality. For generality, most existing MIE algorithms lack generality: they rely on specific chaotic maps and particular image parameterizations, employ non-standard architectures (neither SPN nor Feistel) and perform only a single encryption round. In other words, these algorithms are designed for specific scenarios rather than as a general model.

For performance, although parallel MIE algorithms have been proposed, all encrypted images within a cohort must still be decrypted to retrieve only some of them. This implies that undesired images also need to be decrypted to access the desired ones, thereby wasting computational time and energy. Furthermore, all existing parallel MIE algorithms require plaintext images of the same size. Padding pixels with specific values is therefore necessary to make all images uniform in size, which again increases time and energy consumption during encryption and decryption. Moreover, all existing MIE algorithms assume that pixels in every image are represented with the same bit depth. However, in practice certain application domains, such as medical imaging modalities69 and aerial imagery70, involve heterogeneous images of different sizes and bit depths.

Regarding security, most existing MIE algorithms use static session keys that are independent of image content. Ideally, MIE algorithms should employ session keys that depend on the content of the image during the encryption process. This dependency makes the schemes more resistant to attacks that exploit relationships between plaintext and ciphertext, such as chosen-plaintext, known-plaintext, and chosen-ciphertext attacks. In addition, many chaotic image encryption schemes have been successfully cryptanalyzed, as reported in61,62,63,64,65. The main reason is that their diffusion processes are based on simple linear transformations between plaintext and previous ciphertext pixels. Although such linear equations provide high processing speed, they do not guarantee adequate security. Therefore, nonlinear substitution mechanisms, such as S-boxes, should be incorporated to enhance robustness.

These gaps in the existing MIE algorithms are addressed in our work. In this work, three MIE structures are proposed to overcome the disadvantages, and the main contributions and novelty are as follows.

-

The proposed structures of chaos-based MIE are generic models in the form of substitution-permutation network, so that allow for employing any types of chaotic map, applying any number of encryption rounds to meet the security requirement. Three processes, i.e., permutation, diffusion, and substitution (S-box), are included in the proposed models, and those are combined in the same step and are performed pixel by pixel within individual images. The proposed models can encrypt any number of images, and work on spatial and pixel value domains. The images of a cohort are encrypted in parallel, while any ciphertext images from a cohort can be decrypted to retrieve individual images. Images can be of different sizes and different pixel depths.

-

The session keys in the proposed structures are dependent on the pixel values of the intermediate ciphertext images. The chaotic map is frequently perturbed by a random number generator, and chaotic values, together with random numbers, are used to generate session keys in encryption. In addition, the substitution box (S-box) is included to enhance the confusion property of the encryption. As a result, ciphers that employ the proposed structures can withstand any type of attack that exploits the difference in the plaintexts and ciphertexts.

-

The digital hardware is designed and implemented on the FPGA platform to demonstrate the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed structures in terms of throughput and efficiency. The resultant performance is compared to other existing cryptographic hardware designs.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section Proposed MIE structures presents the details of the encryption, decryption, and operation of the proposed structures. Next, section Exemplar simulation describes the details about the cohort of images, the chaotic map, and the values of the simulation parameters. The simulation results and statistical and security analysis are discussed in this section. Then, section Digital hardware design presents details of the hardware architecture for Structure 1, including operation, and architecture of the MIE Intellectual Property and FPGA Implementation results. The throughput and efficiency of the hardware design are calculated and compared with those in other reported designs. Finally, sections Discussion and Conclusion highlight the highlights of the proposed structures in terms of operation, security, and hardware performance.

Proposed MIE structures

Let us define \(\mathbb {I}=\{I_k\mid k=1,...,K\}\) to be a set of K images, called a cohort, in which image \(I_k=\{p(i_k,j_k)\mid i_k=1,...,M_k, j_k=1,...,N_k\}\) has a size of \(M_k\times N_k\); \(p(i_k,j_k)\) denotes the pixel value of image k at coordinates \((i_k,j_k)\), and is represented by \(Q_k\) bits, called the depth of pixels. It is assumed that the images of a cohort can be of different sizes (\(M_i\ne M_j\) and/or \(N_i\ne N_j\) for \(i\ne j\)) and that the pixels of different images in a cohort have different pixel depths (\(Q_i\ne Q_j\) for \(i\ne j\)). \(I_k\) is simply considered as a matrix of values.

Encryption

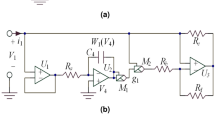

As shown in Fig. 1, each of the proposed structures consists of three processes, that is, permutation, diffusion, and substitution. Here, the diffusion property is achieved by the permutation and diffusion processes, while the confusion property is obtained by the substitution process. The diffusion process depends on the session key; therefore, it also enhances the confusion property. In fact, there can be several encryption structures depending on the relative position of these processes. In this research, the permutation is fixed and performed first, and then the others to ensure that the values of all pixels are changed by the encryption. These processes are performed separately and in parallel on all images. The encryption procedure, details on processes, and the function of blocks of the proposed structures are presented in the following.

Consider encryption for K images at the same time. The plaintext image k with the size \(M_k\times N_k\), \(k\in \left\{ 1,2,\cdots ,K\right\}\), is denoted by \(I_k=\left\{ p(i_k,j_k)|1\le i_k\le M_k, 1\le j_k\le M_k\right\}\). The source and destination locations are respectively denoted by \(XY_k=(i_k,j_k)\) and \(XY^{'}_k=(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\), where i and \(i^{'}\) are row numbers, and j and \(j^{'}\) are column numbers of the image k, with \(k\in \{1,2,\cdots ,K\}\). Intermediate-ciphertext pixels at the source and destination locations are denoted with a hat as \(\widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)\) and \(\widehat{c}(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\), respectively. The ciphertext pixels in an encryption round at the source and destination locations are denoted by \(c(i_k,j_k)\) and \(c(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\), respectively. The final ciphertext image k after \(N_e\) rounds of encryption is denoted by \(C_k\), which is constructed by ciphertext pixels \(c(i_k,j_k)\) with \(1\le i_k\le M_k\) and \(1\le j_k\le M_k\).

In the encryption procedure, pixels are scanned from left to right, row by row until all pixels in an image are encrypted. All images of a cohort are encrypted separately and in parallel for \(N_e\) rounds of encryption.

Structure 1

The first proposed structure, named Structure 1, is illustrated in Fig. 1a, in which the order of the processes is permutation, substitution, and then diffusion.

-

Permutation: The permutation is to move the plain source pixel \(p(i_k,j_k)\) and the destination pixel \(p(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\) in the same image k. Here, \(i_k\) and \(j_k\) of the source pixel are incrementally scanned from left to right and row by row of the image \(I_k\), and \(i^{'}_k\) and \(j^{'}_k)\) of the destination pixel are induced from chaotic values. Details about the way in which the values of \(i^{'}_k\) and \(j^{'}_k\) are calculated will be shown in the next subsection.

-

Substitution: The values of the permuted pixels at the source and destination locations, \(p\left( i_k,j_k\right)\) and \(p(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\), are then changed by substitution. The substitution is carried out by the S-box to get substituted values as

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{ll} \widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)& =\text {S-box}(p(i_k,j_k)),\\ \widehat{c}(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)& =\text {S-box}(p(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)), \end{array} \end{aligned}$$(1)where \(\text {S-box(.)}\) is the function that represents the substitution process and returns the substitution values.

-

Diffusion: After being replaced by Eq. (1), the pixels at the source and destination locations, \(\widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)\) and \(\widehat{c}(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\), are diffused to obtain ciphertext pixels as

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{ll} c(i_k,j_k)& =F^{(Diff)}_k\left( \widehat{c}(i_k,j_k),c(i_k,j_k-1),\phi ^{(S)}_k\right) ,\\ c(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)& =F^{(Diff)}_k\left( \widehat{c}(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k),c(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k-1),\phi ^{(D)}_k\right) , \end{array} \end{aligned}$$(2)where \(F^{(Diff)}_k(.)\) is the diffusion function that operates bit-wise; \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\) and \(c(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k-1)\) are the values of the ciphertext pixels that stand immediately before the source and destination locations, respectively; and \(\phi ^{(S)}_k\) and \(\phi ^{(D)}_k\) are pseudo-random values for the source and destination pixels. Note that the superscripts (S) and (D) are denoted for the source and destination in the following text.

In Structure 1, every source pixel is subsequently performed by three processes as described above. It is clear that the processes of permutation, substitution, and diffusion are combined and performed pixel-by-pixel. All images of a cohort are encrypted separately and in parallel for \(N_e\) encryption rounds.

Structure 2

The second proposed structure, named Structure 2, is presented in Fig. 1b. After permuting pixels, the source and destination pixels are diffused and then substituted as specified below.

-

Permutation: The permutation of Structure 2 is the same as that in Structure 1.

-

Diffusion: Pixels at the source and destination locations \(p(i_k,j_k)\) and \(p(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\) are diffused by

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{ll} \widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)& =F^{(Diff)}_k\left( p\left( i_k,j_k\right) ,c\left( i_k,j_k-1\right) ,\phi ^{(S)}_k\right) ,\\ \widehat{c}(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)& =F^{(Diff)}_k\left( p(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k),c(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k-1),\phi ^{(D)}_k\right) , \end{array} \end{aligned}$$(3)where function \(F^{(Diff)}_k(.)\), pixels \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\), \(c(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k-1)\), and chaotic values \(\phi ^{(S)}_k\) and \(\phi ^{(D)}_k\) are defined in Eq. (2).

-

Substitution: The diffused pixels at the source and destination locations, \(\widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)\) and \(\widehat{c}(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\), are then changed by substitution. The substitution is carried out by the S-box to get ciphertext pixels as

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{ll} c(i_k,j_k)& =\text {S-box}(\widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)),\\ c(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)& =\text {S-box}(\widehat{c}(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)). \end{array} \end{aligned}$$(4)

Compared with Structure 1, the diffusion process of Structure 2 is carried out before substitution. The encryption procedure is also performed pixel by pixel.

Structure 3

The third proposed structure, named Structure 3, is illustrated in Fig. 1c, in which permutation and diffusion are combined and performed pixel by pixel, the same as those in Structure 2. After all pixels of an image are permuted and diffused, a substitution is then performed on all pixels separated from permutation and diffusion. Specifically, the encryption processes are as follows.

-

Permutation: The permutation of Structure 3 is the same as that in Structure 1.

-

Diffusion: The permutation of Structure 3 is the same as that in Structure 2 as given in Eq. (3). After all pixels of the image are permuted and diffused, the intermediate image \(\widehat{C}_k=\left\{ \widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)|1\le i_k\le N_k, 1\le j_k\le M_k\right\}\) is obtained.

-

Substitution: The pixels in the intermediate image \(\widehat{C}_k\) are substituted by the S-box as

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{ll} c(i_k,j_k)&=\text {S-box}\left( \widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)\right) . \end{array} \end{aligned}$$(5)where \(\widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)\) is the pixel in location \(XY_k=(i_k,j_k)\) of \(\widehat{C}_k\).

Remarks

The highlight of the proposed structures can be derived from the configuration as follows.

-

More than one process is combined and performed at the same time. Those processes are permutation, substitution, and diffusion in Structure 1; permutation, diffusion, and substitution in Structure 2; and permutation and diffusion in Structure 3. The combination of more than one process is the difference in the proposed structures from most existing encryption algorithms. As a result, chaotic values are efficiently used for the processes of permutation and diffusion, and the speed is improved compared to that of most existing encryption algorithms in which all pixels of an image are completed for a process before the next process is performed, where it requires chaotic iterations for separate processes.

-

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the proposed structures encrypt images separately and in parallel. Therefore, the various sizes of the images can be accepted. In addition, because the session keys are generated separately for multiple images, the decryption can be done separately for any selected images. In addition, encryption separation allows separation of the decryption, which is the unique feature of the proposed structures.

Decryption

The decryption structures have the same block functions except that the order of processes is reversed compared to that in the encryption. Specifically, the permutation is the same as in the encryption while inverse substitution and inverse diffusion are used. In addition, in every individual image, the direction of the pixel scanning must be reversed in compared with that in the encryption. The decryption is also performed in \(N_e\) rounds.

All blocks of the proposed structures that provide parameters for the encryption processes are described in detail below.

Functions of blocks in the proposed structures

A chaotic map is used to generate pseudo-random values, and its dynamics of a chaotic map is perturbed by bits from the block Session Key Scheduling (SKS), the so-called perturbed chaotic map (PCM). The PCM and SKS are initiated and then iterated to generate bit sequences for permutation and diffusion during encryption. As shown in Fig. 1, Bit Pre-processing of image k, \(BPP_k\), uses bits of next plaintext, \(p(i_k,j_k+1)\), previous ciphered pixels, \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\), and the SKS bit sequence, \(sk_k\), to generate the coordinates of the destination pixel for permutation (\(XY^{'}_k\)) and pseudo-random values (\(\Phi _k\)) for diffusion to encrypt the present pixel of image K. The functions of blocks in the proposed structures are explained as follows.

Perturbed chaotic map (PCM)

The general model of PCM is employed in the proposed structures expressed by

where F(.) is a chaotic function; \(Y_i\) with \(i=1,..,4\) are bit arrangements in the construction of bit sequences of perturbation; \(X_n=[x_n^{(D)}\) \(x_n^{(D-1)}...\) \(x_n^{(2)}\) \(x_n^{(1)}]^T\) is the vector of state variables; \(\Gamma _0=[\gamma _0^{(G)}\) \(\gamma _0^{(G-1)}...\) \(\gamma _0^{(2)}\) \(\gamma _0^{(1)}]^T\) is the vector of initial control parameters and is regularly perturbed by \(\Delta _{\Gamma _n}=[\delta _{\gamma ^{(G)}_n}\) \(\delta _{\gamma ^{(G-1)}_n}...\) \(\delta _{\gamma ^{(2)}_n}\) \(\delta _{\gamma ^{(1)}_n}]^T\). D and G are the numbers of dimensions and those of the control parameters of the chaotic map, respectively. \(\widehat{\Gamma }_n=[\widehat{\gamma }_n^{(G)}\) \(\widehat{\gamma }_n^{(G-1)}...\) \(\widehat{\gamma }_n^{(2)}\) \(\widehat{\gamma }_n^{(1)}]^T\) is the vector of perturbed control parameters53.

The configuration of the PCM53.

Figure 2 illustrates the general PCM configuration, in which \(Y_i\), \(i=1,2\), performs the bit arrangement so that the bit of \(X_n\) is extracted and used to perturb the chaotic map. The bit sequence E with \(L_E=L_X+L_{\Gamma }\) bits in length is used as an external perturbation. The values of \(x_n^{(d)}\) and \(\gamma _n^{(g)}\), with \(d=1,...,D\) and \(g=1,...,G\), are represented by the \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) bits, respectively. The values of \(x_n^{(d)}\) and \(\gamma _n^{(g)}\) are real, so the numbers of bits for the integer and fraction portions of \(x_n^{(d)}\) and \(\gamma _n^{(g)}\) are denoted by \(\left\langle m^{(int)}_1,m^{(frac)}_1\right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle m^{(int)}_2,m^{(frac)}_2\right\rangle\), respectively, with \(m_1=m^{(int)}_1+m^{(frac)}_1\) and \(m_2=m^{(int)}_2+m^{(frac)}_2\) as

where \(a_i\) and \(b_i\) are binary. The amounts of perturbation, \(\delta _{x_n^{(d)}}\) and \(\delta _{\gamma _n^{(g)}}\), are

where \(c_i\) and \(d_i\) are binary. Similarly, the values of \(\widehat{X}_n\) and \(\widehat{\Gamma }_n\) are represented by

where \(e_i\) and \(f_i\) are also binary. The perturbation is the XORing operation as follows.

The value ranges of state variables and control parameters must be constrained in those as in the original model. So, a certain number of bits in the values of \(x_n^{(d)}\) and \(\gamma _n^{(g)}\) are fixed with specified values to ensure that the PCM exhibits chaotic behavior, while the other bits can be flippable. The positions of the perturbed bits are specified by \(Y_i\).

In this work, PCM is initiated by \(X_0\) and \(\Gamma _0\), and iterates for R times to get \(X_R\) to encrypt a set of K pixels; each pixel comes from an image. This process is repeated until all pixels in every image are encrypted for \(N_e\) rounds of encryption. More details on PCM can be found in53.

Session key scheduling (SKS)

s The SKS produces session keys to encrypt individual pixels and perturb the PCM. The core of SKS is the keystream generator based on the linear feedback shift register (LFSR)71.

The input of the keystream generator is the initial vector \(S_0\) and the predefined private key ID. The SKS outputs are the session keys \(sk_k\) with \(k=1,...,K\) and the bit sequence E for PCM perturbation. The bit sequence \(sk_k\) will be used to identify the location of destination pixels (\(XY^{'}_k\)) and to generate diffusion values (\(\Phi _k\)), so the length of \(sk_k\) must be

where \(N_{pix\_max}=M_{max}*N_{max}\) is with \(M_{max}=\textrm{max}_{k\in \{1,2,...,K\}}M_k\) and \(N_{max}=\textrm{max}_{k\in \{1,2,...,K\}}N_k\); \(Q_{max}\) is the maximum number of bits that represent a pixel of images, \(Q_{max}=\textrm{max}_{k\in \{1,2,...,K\}}Q_k\); and \(\lceil .\rceil\) is the round-up function.

The length \(L_E\) requires \(\left( K*L_{sk}+L_E\right)\) bits to encrypt a group of K pixels from K images at the same time. Therefore, the sequence requires at least \((K*L_{sk}+L_E)*N_{pix\_max}\) bits to encrypt all pixels of K images. Consequently, the number of states of LFSR72 must be at least

As shown in Fig. 3a, each frame is of \(K*L_{sk}+L_E\) bits to encrypt K pixels from K images. So, it requires \(N_{pix\_max}\) frames to encrypt all pixels of K images. In detail, each sequence \(sk_k\) is used to produce pseudo-random values, as shown in Fig. 3b.

The bit sequence E is used to construct \(\delta _{x^{(d)}_n}\) and \(\delta _{\gamma ^{(g)}_n}\) to perturb the PCM as shown in Eq. (8). The length of E, \(L_E\), is considered using the numbers of bits represented for the values of the state variables, and the control parameters are \(D*m_1\) and \(G*m_2\), respectively. However, some constraints are made for the range of state variables and control parameters of the PCM to ensure the existence of chaotic behavior. In terms of security, the number of bits that are extracted to construct \(XY^{'}_k\) and \(\Phi _k\) should be lower than \(D*m_1\), so the attacker is challenged to recover chaotic dynamics and infer values of \(X_0\) and \(\Gamma _0\).

Bit Pre-processing (BPP)

The BPP takes bits from \(X_R\), \(sk_k\), and \(pc_k\) to produce the coordinate of the destination pixel, \(XY^{'}_k=(i^{'}_k,j^{'}_k)\), for permutation with the pixel at \((i_k,j_k)\) of the image k as

and pseudo-random values, \(\Phi _k=\{\phi ^{(S)}_k,\phi ^{(D)}_k\}\), for diffusion of source and destination pixels as

where \(F^{(IJ)}_{k}(.)\) and \(F^{(\Phi )}_k(.)\) are bitwise functions of image k. bit sequences \(bs^{(I)}_k\), \(bs^{(J)}_k\), \(bs^{(S)}_k\), and \(bs^{(D)}_k\) are extracted from the values of \(X_R\); bit sequence \(pc_k\) is formed by interleaving bits of pixels \(p(i_k,j_k+1)\) and \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\) as given in Eq. (16); \(M_k\) and \(N_k\) are the actual size of the image \(I_k\), and each pixel is represented by \(Q_k\) bits; and mod(.) is the modulus function.

Bit interleaving

The block Bit interleaving is used to interleave bits of the next plain pixel \(p(i_k,j_k+1)\) and the past ciphertext pixel \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\) of the image \(I_k\), and a bit sequence \(pc_k\) is obtained. Specifically, the representation of \(p(i_k,j_k+1)\) and \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\) is

where \(b^{(p)}_i\) and \(b^{(c)}_i\) are binary. The bitwise operation of interleaving is as follows.

where || is the bit concatenation operation. The initial ciphered pixels \(c^{(0)}_k\) and the plain pixels \(p(M_k,N_k+1)\) denoted by \(p^{(0)}_k\) for \(\forall k\in \{1,2,...,K\}\) are used to encrypt the pixels at (1, 1) and the last pixel at \((M_k,N_k)\), respectively. Those are part of the secret key.

Operation and security of the proposed structures

In this subsection, the operation of the structures proposed in Fig. 1 is described step by step in the form of a flow chart as in Fig. 4. The security in terms of the secret key space and the image-content dependency is discussed.

The operation

The flow charts in Fig. 4 show that the encryption is separated for each image and in parallel for multiple images. The inputs are the parameters’ values, including the number of encryption rounds (\(N_e\)), the initial vectors and control parameters of the chaotic map (\(X_0\) and \(\Gamma _0\)), the number of cohort images (K) and the size of images (\(M_k\), \(N_k\) and \(Q_k\)), the number of chaotic iterations (R), the substitution box (S-box), initial secret values (\(p^{(0)}_k\), \(c^{(0)}_k\)). From that, running values are set for the encryption of K images.

Each encryption session is separate for an individual image. For each image encryption session, \(Pause_k\) is the flag that indicates that the encryption process for image \(I_k\) is in progress (\(Pause_k=0\)) or complete (\(Pause_k=1\)). In an encryption progress for the image \(I_k\), the processes of permutation, diffusion, and substitution are performed in the orders described in Subsection Description for the encryption.

As shown in the flowchart for Structures 1 and 2 in Fig. 4a and 4b, pixels are chosen to encrypt sequentially, that is, scanning from left to right and row by row. Each pair of pixels, source and destination pixels, in Structures 1 and 2 is processed by combining the permutation, diffusion, and substitution in one step. Then, the next pair of pixels is processed as indicated by the increment of \(i_k\) and \(j_k\). During each process, appropriate equations as described for Structures 1 and 2 in Subsection Description for the encryption are used. If all pixels of \(I_k\) are scanned and encrypted for rounds \(N_e\), that is, \(n_k>N_e\), the encryption of the image \(I_k\) is complete by setting the flag \(Pause_k=1\).

The flowchart in Fig. 4c for Structure 3 shows that the permutation and diffusion processes are carried out the same as those in Structures 1 and 2, except that the substitution process is separated from the permutation and diffusion. The substitution process is performed after all pixels of \(I_k\) are permuted and diffused.

The encryption for all images is finished if all the flags are set to ‘1’, that is, \(Pause_k=1\) for \(\forall k\in \{1,2,\cdots ,K\}\). Specifically, K encryption sessions are performed in parallel for K images. The chaotic map is iterated while the LFSR is shifted at the same time. The session keys are generated in parallel for K encryption sessions.

It is clear from the structural configuration and flow charts of the encryption algorithms that all images are encrypted separately and in parallel. Therefore, three features are achieved; that is, it allows images with different sizes and different pixel depths, and it allows decrypting some ciphertext images of a cohort, instead of decryption for all ciphertext images as in existing algorithms. In addition, these structures can be easily implemented on the parallel computing platform, such as multiple cores and hardware design, to achieve high-speed encryption.

The security

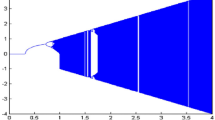

Consider the security of the proposed structures in terms of secret key space and image-content dependency. Firstly, the secret key space of the proposed structures is considered by several factors, i.e. the initial vectors of state variables and control parameters of the chaotic map, the LFSR’s seed, initial values of ciphertexts \(c^{(0)}_k\) and plaintexts \(p^{(0)}_k\) with \(k=1,2,\cdots ,K\) as in Eq. (15), and the user key of the block SKS. Specifically, the number of bits for the LFSR’s seed and the user key can be chosen as desired, but it must satisfy the number of states given in Eq. (12) to ensure randomness of session keys. The initial values of \(c^{(0)}_k\) and \(p^{(0)}_k\) with \(k=1,2,\cdots ,K\) have a fixed number of bits. For example, 64 bits for \(c^{(0)}_k\) and 64 bits for \(p^{(0)}_k\) with \(K=8\) and 8-bit grayscale pixels. The initial vectors of the chaotic map consist of the initial value of the state variables, \(X_0\), and the initial value of the control parameters, \(\Gamma _0\). Here, the chaotic map is implemented on a digital platform, so \(X_0\) and \(\Gamma _0\) are represented by a number of bits. The chaotic map is perturbed as shown in Fig. 2, therefore, the bits that are changed during the iteration of the chaotic map are considered the secret key. The number of bits of the secret key can be as long as desired and depending on the representation for the values of state variables and control parameters. In addition, a chosen chaotic map whose state variables and control parameters have a large value range of chaotic behavior also provides a large number of bits for the secret key. Moreover, depending on the chaotic map adopted, higher dimensions of state space can provide a large number of bits for the secret key. For example, the Logistic map has only one state variable, and the value range of chaotic variable is in the range 0 to 1. Therefore, the number of bits for the secret key is dependent on the number of bits representing the values of the state variable and control parameters. In contrast, the Cat map and the Standard map are two-dimensional state variables, and the value ranges of state variables and control parameters that exhibit chaos are larger than the Logistic map. Therefore, the Cat map and Standard maps can provide a number of bits for the secret key larger than that from the Logistic map. In summary, the number of bits for the secret key or the key space can be as large as desired in several ways, as given above. However, adoptions of a large number of bits representing values of state variables and control parameters and/or higher-dimensional chaos pay the speed of encryption. It takes longer to compute for an iteration of the chaotic map.

Secondly, the proposed MIE algorithms have the image-content dependency. Specifically, the current session keys are the coordinates of destination pixels \(XY^{'}_k\) and pseudo-random values \(\Phi _k\) with \(k=1,2,\cdots ,K\). For image \(I_k\), \(XY^{'}_k\) and \(\Phi _k\) in Eqs. (13) and (14) are directly related to the values of the previous ciphertext pixel \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\) and the next plaintext pixel \(p(i_k,j_k+1)\) by means of \(pc_k\) as given in Eq. (16). This means that the permutation and diffusion processes depend on the image content. The dependency on image content provides better security and resistance to the types of attacks such as chosen-plaintext and chosen-ciphertext attacks. However, the algorithms of proposed structures continually encrypt pixel-by-pixel throughout images, so they cannot resist the ciphertext-crop attack.

Exemplar simulation

In this section, examples of all proposed structures are simulated using Python v3.12.6, and then statistical and security analyzes are performed using Matlab R2016a for the simulation results to confirm effectiveness.

Chosen chaotic maps, images and values of parameters for simulation

In this example, a set of eight images as shown in Fig. 5 is encrypted using each of the three proposed designs. Table 1 shows the size of the image and the number of bits that represent pixels in different images. As given in Table 2, the critical values for encryption are to specify its capability to adopt the values of other parameters. \(K_{max}\), \(M_{max}\), \(N_{max}\), and \(Q_{max}\) are, respectively, the maximum numbers of images, rows, and columns of pixels, and of bits representing a pixel. Here, the chosen values are greater than or at least equal to the actual numbers characterized by the images.

-

Chosen chaotic maps: The Cat map is chosen and its perturbation is described in the form of Eq. (6) as

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \left[ \begin{array}{c} x^{(2)}_{n+1}\\ x^{(1)}_{n+1}\end{array} \right] & = mod\left( \left[ \begin{array}{c} \widehat{\gamma }_n^{(1)}x^{(2)}_n+\left( 1+\widehat{\gamma }_n^{(2)}\widehat{\gamma }_n^{(1)}\right) x^{(1)}_n\\ x^{(2)}_n + \widehat{\gamma }_n^{(2)}x^{(1)}_n\end{array}\right] ,1\right) ,\\ \left[ \begin{array}{c} \widehat{\gamma }^{(2)}_{n}\\ \widehat{\gamma }^{(1)}_{n} \end{array} \right] & = \left[ \begin{array}{c} \gamma ^{(2)}_{0}\\ \gamma ^{(1)}_{0} \end{array} \right] \bigoplus \left[ \begin{array}{c}\delta _{\gamma ^{(2)}_{n}}\\ \delta _{\gamma ^{(1)}_n} \end{array} \right] , \\ \left[ \begin{array}{c}\delta _{\gamma ^{(2)}_{n}}\\ \delta _{\gamma ^{(1)}_{n}} \end{array} \right] & = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \left[ \begin{array}{c} Y^{(a)}_1\left( E\right) \\ Y^{(b)}_1\left( E\right) \end{array} \right] & \text {for } n=1, \\ \\ \left[ \begin{array}{c} Y^{(a)}_2\left( x^{(2)}_{n}\right) \\ Y^{(b)}_2\left( x^{(1)}_{n}\right) \end{array} \right]&\text {for } 1< n \le R, \end{array} \right. \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$(17)where \(X_n=\left[ x^{(2)}_{n}~~x^{(1)}_{n}\right] ^\intercal\) are state variables and \(\Delta _{\Gamma _n}=\left[ \gamma ^{(2)}_{n}~~\gamma ^{(1)}_{n}\right] ^\intercal\) are control parameters; these are in the ranges of \(x^{(2)}_{n}\), \(x^{(1)}_{n} \in (0,1)\) and \(\gamma ^{(2)}_{n}\), \(\gamma ^{(1)}_{n}>0\); \(Y^{(a)}_2\), \(Y^{(b)}_2\), \(Y^{(a)}_1\) and \(Y^{(b)}_1\) are to arrange bits of either E or \(X_n\) to construct permutation amounts. The values of the state variables and control parameters are represented as fixed-point numbers. The formats, bit patterns, value ranges, and bit positions to be perturbed are given in Table 3. \(Y^{(a)}_1\) and \(Y^{(b)}_1\) are chosen the same format as \(Y^{(a)}_2\) and \(Y^{(b)}_2\), respectively, but bits are from E. Bit arrangements \(Y^{(a)}_2\) and \(Y^{(b)}_2\) are chosen to construct perturbation amounts \(\Delta _{\Gamma _n}\) as shown in Table 4; where \(B_0\) at specific positions are fixed at ‘0’, and the group \((i,b_j)\) is denoted for bit \(b_j\) of the state variable \(x^{(i)}_n\). These are bits used as \(d_i\) in Eq.(8), and the perturbation is based on the XOR operation as given in Eq. (10). The initial values in decimal for the PCM are chosen as in Table 5. It is noted that even though the value range of control parameters are separated and the perturbation is applied, the chaotic behavior certainly exists with nonstationary dynamics.

-

The SKS: From Table 2, the maximum number of pixels in each image is \(N_{pix\_max}=2^{20}\) or 2048 pixels. According to Eq. (11), the length of \(sk_k\) is \(L_{sk}=68\) bits. As assumed that each of the state variables and control parameters of the PCM is perturbed by 16 bits as given in the leftmost column of Table 3, therefore, the length of bit sequences to perturb the PCM is \(L_E=64\) bits for the perturbed Cat map. In this example, the LFSR is chosen and, according to Eq. (12), the number of states of LFSR is \(N=32\) with the primitive polynomial \(X^{32}+X^{22}+X^{2}+1\) as suggested in 72. The seed of LFSR is \(S_0\) in hexadecimal form, as shown in Table 5.

-

The BPP: Table 6 shows bits of chaotic values, \(b_{-17}\)...\(b_{-48}\), being extracted and used to construct values of coordinates of destination pixels and pseudo-random values in Eqs. (13) and (14), respectively. More specifically, bits sequences \(bs^{(t)}_k\) with \(t\in \{I,J,S,D\}\) in the four leftmost columns of Table 6 are taken bits of chaotic values in the second column. Then, bit sequences \(bs^{(t)}_k\) with \(t\in \{I,J,S,D\}\) are XORed with portions of \(sk_k\) (see Fig. 3b) to produce pseudo-random values for permutation and diffusion. The modulus is applied as given in Eqs. (13) and (14) for smaller images and smaller number of bits representing the pixels. The XOR operation is chosen for functions \(F_k^{(IJ)}\) and \(F_k^{(\Phi )}\) in Eqs. (13) and (14) as \(F_k^{(IJ)}=bs_k^{(t_1)}\oplus sk_k^{(t_1)} \bigoplus _{i=1}^T pc^{(i)}_k\) and \(F_k^{(\Phi )}=bs_k^{(t_2)}\oplus sk_k^{(t_2)} \bigoplus _{i=1}^T pc^{(i)}_k\), with \(t_1\in \{I,J\}\) and \(t_2\in \{S,D\}\). Here, the bit sequences \(sk_k^{(t_1)}\) and \(sk_k^{(t_2)}\) can be cut to shorten and fit the lengths of \(bs_k^{(t_1)}\) and \(bs_k^{(t_2)}\), respectively. Also, bit sequence \(pc_k\) is padded with bits 1’s to have the length equal to an integer number of times of the length of \(bs_k^{(t)}\) with \(t\in \{I,J,S,D\}\), then it is divided into T sub-sequences before XORing all together.

-

The diffusion: Similarly to the functions in the BPP, the function \(F^{(Diff)}_k(.)\) is the XOR operation among its entries in Eqs. (2) and (3) as \(F_k^{(Diff)}=\widehat{c}(i_k,j_k)\oplus c(i_k,j_k-1) \oplus \phi _k^{(t)}\) and \(F_k^{(Diff)}=p(i_k,j_k)\oplus c(i_k,j_k-1)\oplus \phi _k^{(t)}\), respectively, with \(t\in \{S,D\}\).

-

The S-box: In this exemplar simulation, the 8-bit AES S-box73 and its corresponding inverse S-box are chosen. In fact, a new S-box can be generated by using chaotic values. For pixels represented by 24-bit data, i.e. red, green, and blue colors, three consecutive substitutions using the same S-box are performed, such that each is for 8 bit data of pixels. Then, the outputs of the S-box are merged to return 24-bit data of pixels.

Ciphertext images in the example using Structure 1 in Fig. 1a encryption rounds \(N_e=1,...,5\).

Simulation results

Here, the set of eight images is encrypted for several rounds of encryption, \(n_k=1..N_e\), with \(k=1...K\) and \(N_e=5\). Figures 6, 7 and 8 display the ciphertext images produced by the exemplar designs using Structures 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The ciphertext images look like random images in every first round of encryption. In addition, these ciphertext images were successfully decrypted for any selected individual ciphered images.

Ciphertext images in the example using Structure 2 in Fig. 1b encryption rounds \(N_e=1,...,5\).

Ciphertext images in the example using Structure 3 in Fig. 1c encryption rounds \(N_e=1,...,5\).

It should be noted that the three-color image is considered as a grayscale image with a pixel depth of 24 bits. However, the color image is separated into three 8-bit grayscale images for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Firstly, the randomness test is performed using the NIST SP 800-22 test standard to confirm the quality of session keys. Then, a statistical analysis of ciphertext images is performed with two main metrics, namely information entropy and correlation coefficients. Statistical analysis is measured for individual channels of color images, whereas bits of color channels are concatenated for encryption. Table 7 shows the information entropy and correlation coefficients of the original images.

NIST randomness test for session keys

Here, the randomness test is performed for the bit sequences generated by the SKS blocks to confirm the quality of the session keys. As shown in Fig. 1, the session keys are \(sk_k\) with \(k=1,2,\cdots ,8\), and more than 2 million bits of each session key \(sk_k\) are recorded for the test. In this study, the NIST SP 800-22 test standard is used for the session key randomness test. Each session key \(sk_k\) with a length of 165.457.600 bits is collected during encryption for the test. The test result is judged by \(P-value\), and it is passed if \(P-value>0.01\). Table 8 shows the test result of \(sk_k\) with \(k=1,2,\cdots ,8\), and it is clear that all \(P-value\) are greater than 0.01 or pass. In other words, all the session keys in the exemplar simulation have good randomness and are qualified for encryption.

Information entropy

The information entropy (IE) of an image measures the randomness of the values of the pixels, and the ideal value of IE is equal to the number of bits that represent the pixels. An image is mostly random if its IE is close to the ideal value.

In this example, IE of the color images is computed for each channel, so the ideal value of IE is 8 bits. Table 9 displays IE of encrypted images with different numbers of encryption rounds, \(N_e=1,...,5\). The values of IE of all encrypted images are almost equal to the ideal value (8 bits) in every encryption round. The information entropy of all plaintext images in the simulation changes quickly from small values in the original images as given in Table 7 to almost 8 after the first round of encryption, at \(N_e=1\). The average information entropy is measured in all ciphertext images and is unchanged with increasing number of encryption rounds. In all simulations, the average value of 7.9992 is very close to the ideal value of 8, which means that the values of the pixels in the ciphertext images are highly random and uniformly distributed.

Histogram analysis

The histogram of an image reflects the distribution of pixel values, and the statistical histogram can be measured using the chi-square test with a significance level of 0.05. The equation of \(\chi ^2\) is

where V is the number of gray level (\(V = 256\) for 8-bit grayscale images), and \(O_i\) and \(E_i\) are respectively observed and expected occurrence frequencies of gray level i, with \(0\le i\le V-1\). The expected occurrence frequency of 8-bit grayscale images is \(E_i = \frac{M*N}{V}\); \(M\times N\) is the size of the images. The hypothesis test considers the significance of the histogram if it complies with a uniform distribution, and the test is accepted (or the histogram is uniformly distributed) if \(\chi ^2\le \chi ^2_\alpha (V-1)\). In this example, the significance level \(\alpha = 0.05\) is considered, and \(\chi ^2_{0.05}(255) = [293.247]\).

Table 10 gives the test results of the ciphertext images for the exemplar simulation. The value of \(\chi ^2\) is less than [!tb]. In other words, the histogram statistics of all ciphertext images pass the test, or the histogram of ciphertext images is uniformly distributed. It is clear that the chi-square values of the plain text images in Table 7 are large, but are quickly reduced to and smaller than \(\chi ^2_{0.05}(255)\). The average values are calculated on the overall ciphertext images, and the chi-square test with significant level \(\alpha = 0.05\) and passed, even after the first encryption round, means that the histogramof ciphertext images are uniformly distributed.

Correlation coefficients between adjacent pixels

It is well known that a high similarity in the values of adjacent pixels in an image makes the visual structure. In this example, the correlation coefficients (CCs) between pairs of adjacent pixels in three directions, that is, horizontal (H), vertical (V) and diagonal (D), is measured, and the Pearson correlation coefficient is used for measurements for grayscale images and every channel of color images. The closer the CCs are to zero, the more random the image is.

Tables 11, 12 and 13 show the CCs of the ciphertext images in the exemplar simulation of each design. The results show that the CC values are close to zero in every encryption round, which means that the ciphertext images. However, the values of Clock’s CCs are the biggest in all examples. The average values are calculated on all the ciphertext images of the cohort. Even the average values are small, but they fluctuate around zero and regardless to number of encryption rounds. This means that the visual structure in the plaintext images, with large value of CCs as seen in Table 7, is destroyed in the ciphertext images, with small values in all directions of horizontal, vertical and diagonal, as seen in Table 11, 12 and 13.

Compared with the values of the original images given in Table 7, the IE, the Chi-square test and the CC of the plain images are significantly changed compared to those of the ciphertext images given in Table 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13.

Security analysis

Let us consider the security aspects of the examples using the proposed structures using two crucial metrics, namely the secret key space and the sensitivity of the secret key.

Space of the secret key

The space of the secret key is considered by the number of flippable bits which are initial values of parameters. In this simulation, the flippable bits of initial values of the Cat map (\(X_0\) and \(\Gamma _0\)) and of the SKS (\(S_0\)) as well as of plaintext and ciphertext pixels (\(c^{(0)}_k\) and \(p^{(0)}_k\) with \(k=1..K\)) in the context of encrypting eight images. Table 14 shows 486 flippable bits that contribute by parameters. In other words, the secret key space is \(2^{486}\), and the ciphers in this exemplar simulation based on the proposed structures can resist brute-force attacks using modern computers.

Sensitivity of the secret key

The sensitivity of the secret key of a MIE algorithm can be assessed by measuring the difference between two sets of ciphertext images that are obtained from the same set of plain images using two almost identical secret keys. Two secret keys are said to be almost identical because one of them is produced by using the other with slight modification. In this simulation, the least significant bits of the parameters are changed in turn to make the smallest difference between pairs of secret keys, as shown in Table 15.

The number of pixels change rate (NPCR) and the unified averaged changed intensity (UACI)74,75 are used to measure the sensitivity of the secret key in two sets of ciphertext images. Specifically, a pair of ciphertext images \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are used to calculate NPCR and UACI as

and

where \(D(x,y)=1\) if \(C_1(x,y)\ne C_2(x,y)\), and \(D(x,y)=0\) if \(C_1(x,y)=C_2(x,y)\). The values of NPCR and UACI are used to determine the random tests. A random test with the critical value \(\alpha =0.05\) is passed if \(NPCR\ge 99.569\%\) and \(UACI\in [33.282\%, 33.644\%]\) as mentioned in75.

As given in Eq. (16), the initial plain pixels, \(p_k^{(0)}\) with \(k=1,..,K\), are used to perturb the chaotic map in encryption for the last pixels in the final encryption round. So, the sensitivity of the initial plain pixels is not used to consider the sensitivity for encryption. Similarity, sensitivity of the initial ciphertext pixels is only considered for the decryption.

Tables 16, 17 18, 19, 20 and 21 present NPCR and UACI ciphertexts to analyze the sensitivity of each secret key parameter. The tests are measured for individual images and for all images using average values. It is clear that most of the tests for individual images have been passed, and average values indicate that cipherext images of the cohort have been passed for sensitivity of every parameter. Passing the test of average values is very important for the case of MIE. Here, the average values of NPCR and UACI fluctuate slightly around 99.6 and 33.4 for all changes in the secret key and regardless of the number of encryption rounds. The sensitivity test is passed for every parameter of the secret key; therefore, any parameters can be used equivalently to lengthen the number of bits of the secret key. In other words, the exemplar ciphers in this simulation that use the proposed structures are highly sensitive to the smallest changes in the secret key.

Comparison to the simulation results of some algorithms of chaos-based MIE

Table 22 shows the comparison between the exemplar simulation using the proposed structures and some existing MIE algorithms based on chaos. Here, comparisons are made only on the statistical properties of ciphertexts and the security properties of algorithms, regardless of structural configuration, parallelism, techniques, and image-content dependency. It is clear that the statistical properties of the ciphertexts in this simulation, i.e. information entropy and correlation coefficients, are comparable to those of existing algorithms. Although the key space of the exemplar designs (\(2^{486}\)) is moderate compared to that of other algorithms, it is large enough to resist the brute-force attack using a modern computer. The randomness of ciphertexts and sensitivity of secret key in this simulation are measured with pass by means of the chi-square test and of NCPR and UAIC, while some other algorithms are not quantitatively reported.

The simulation shows by means of the exemplar ciphers that the proposed structures are effective for practical applications. Next, the hardware for Structure 1 is designed, simulated, verified, and implemented on the FPGA platform to confirm the feasibility of the proposed designs in hardware applications.

Digital hardware design

In this section, the hardware for MIE Structure 1 as illustrated in Fig. 1a is designed and implemented on the Intel FPGA device. The reason for choosing the FPGA platform is that the pixels of an individual image are permuted in the range of the image. The GPU only outperforms the FPGA if an image is processed in separate portions of pixels. In addition, the pipeline is implemented in FPGA to parallelize the encryption process for every individual image.

The hardware design uses the value of parameters for in the simulation mentioned above. The results on resource utilization, throughput, and hardware performance will also be evaluated and discussed. The hardware architecture of decryption is analogous to that of encryption, but the difference is only the reverse order of pixel processing compared to that of encryption.

Hardware architecture of MIE

Figure 9 shows the MIE system architecture that incorporates MIE hardware as a core component, which is named MIE Intellectual Property (MIE-IP). The MIE-IP receives instructions from the processor through the AXI4-Lite communication interface to manage control information such as parameter setting for the encryption system, encryption requests, and read/write requests of data. The DDR4 SDRAM module is used to accommodate the image data for encryption or decryption. Both the processor and MIE-IP interface with the Memory Controller to access data in the DDR4 SDRAM. Furthermore, the application connects with the MIE system through high-speed data communication protocols such as PCIe or Ethernet. The operation of MIE System can be tracked through the JTAG communication interface.

Operation of digital hardware

The MIE-IP hardware performs the encryption function described above. The execution time is balanced to have optimal speed for the entire system. So, the MIE system performs on blocks of \(K\times N_{co}\) pixels in the internal memory, SRAM, of the FPGA chip. A block of pixels is illustrated in Fig. 10. A cohort of K pixels, each from an individual image, is encrypted at the same time. The encryption is repeated block by block until all images are encrypted. Encryption of a block is called an iteration. In each iteration, the hardware performs reading a block of data from the DDR4 SDRAM into the SRAM, encrypting blocks’ pixels, and writing encrypted pixels from the SRAM into the DDR4 SDRAM.

Memory reads/write

The scheme of consecutive read/write commands is used for reading/writing blocks of pixels between the SRAM and the DDR4 SDRAM. As an example for two consecutive read commands, the detail of the time is shown in Fig. 11. Specifically, the duration is \(T_2 = t_{acc} + t_{read1}+ t_{read2}+ t_{diff}\) with \(t_{diff} \ll t_{acc}\) and \(t_{diff} \ll t_{read}\); where \(t_{acc}\) is the time access of the read commands; \(t_{read}\) is the time for all data to be read, and \(t_{diff}\) is the delay between two read commands or between two groups of data from consecutive read commands. Multiple consecutive read commands can be performed to save time. This is also applicable to write commands.

Timing diagram of the scheme of two consecutive read commands with the DDR4 SDRAM76.

Operation phases of digital hardware

In this work, the allocation of time for the operating phases of the hardware is illustrated in Fig. 12. The encryption process is divided into multiple iterations and each iteration encrypts a block of pixels. An iteration consists of a series of phases, that is, Initial Key Phase and Normal Computation Phases, as shown in Fig. 12.

At the beginning of MIE, the SKS performs Initial Key Phase, and then the PCM iterates for the first value in Phase 1. Blocks of pixels are read from the DDR4 SDRAM into the SRAM, encrypted in SDRAM, and written back to the DDR4 SDRAM in Phases 2, 3, and 4. In order to optimize computation time, Session Key Scheduling, called Key Phase, for the next block is performed concurrently with Phases 2, 3, and 4 of the current block.

MIE-IP architecture

The abstract architecture of MIE-IP is shown in Fig. 13. The design consists of five key components, as detailed in the following.

Register block

Register Block (RB) is a collection of registers that are used to store parameters, operational information, and system status information. Processor (CPU) writes control information to and reads status information from the RB via the AXI4-Lite communication interface.

Global computing

Global Computing (GC) consists of three main components: Session Key Scheduling, PCM Computing, and Position Generator.

Session Key Scheduling (SKS) works as an LFSR-based keystream generator. The number of states for the LFSR in the SKS is calculated based on Eq. (12), i.e., \(N= 32\) states as in the simulation. However, the number of bits required to encrypt a cohort of K pixels is equal to the length of a frame given in Fig. 3, i.e., \(L_E+K*L_{sk}= 608\) bits in this exemplar design. With an LFSR of 32 states, it requires 608 clock cycles to obtain 608 bits. To reduce the time delay in generating a sequence of 608 bits, this design implements the pipeline of 19 parallel-running LFSRs, and each LSFR is 32 bits in length. The seed \(S_0\) of 32 bits is modified to become 19 seeds for 19 LFSRs. The bit sequences in the outputs of 19 LFSRs are merged to become 608 bits. In other words, the sequence of 608 bits is generated in only 32 clock cycles.

PCM Computing (PC) performs R chaotic iterations to get a value vector of \(X_R\). So, a block of \(N_{co}\) cohorts requires \(N_{co}\) values of \(X_R\). In order to optimize the speed of the hardware, the pipeline technique is applied to the hardware design for the PC, in which R PCMs are implemented and run in parallel using the same clock signal. However, such the R PCMs are put together in chain to reduce the computation time that the output of a PCM is the input of another. Therefore, instead of \(R*N_{co}\) clock cycles to obtain \(N_{co}\) values of \(X_R\), it requires only \(R + N_{co}-1\) clock cycles as Fig. 14 illustrates the timing diagram of PCM Computing, where values of \(X_R\) are obtained at \(t_R\) in different PCMs. In this exemplar design, \(N_{co}=8\) and \(R=5\) are chosen, so it only requires 13 clock cycles, instead of 39 clock cycles.

Position Generator performs the computation using Eqs. (13) and (14), and is implemented on hardware using only combinational logic gates, so it does not require any clock cycle in the timing diagram of the system.

Image computing core

Each Image Computing Core (ICC) is responsible for encrypting pixels of an individual image. The more ICCs integrated into the system, the greater the number of images that can be encrypted simultaneously.

Each ICC composed of four primary components, i.e. Bit Pre-processing (BPP), Bit Interleaving (BI), Permutation-S-box-Diffusion (PSD), and Read-Write Image Controller (RWIC). The specific roles of BPP, BI, and PSD are detailed above. The RWIC component oversees the reading and writing processes of blocks of pixels from the Memory Read/Write Coordinator. The ICCs perform its computations in parallel, each ICC operates independently without interference from others.

Memory read/write coordinator

Memory Read/Write Coordinator (MRWC) is responsible for coordinating data transfer between the Memory Controller via the AXI4 interface and the ICCs. The MRWC uses the SRAM on the FPGA chip to temporarily store image data retrieved from the DDR4 SDRAM in Phase 2 and to temporarily hold encrypted image data before being written to the DDR4 SDRAM by MIE-IP. In addition, this block also performs the crucial function of converting pixel coordinates into corresponding storage addresses in the DDR4 SDRAM, and vice versa. There are two specific data organization methods as shown in Fig. 15, where pixels with the same highlighted color correspond to the same image.

The first method in Fig. 15a organizes the images in a continuous way. The second method in Fig. 15b allocates pixels of the same image to a separate memory region where pixels of the same image are non-adjacent addresses in the DDR4 SDRAM. In fact, the first method provides better optimization for memory space compared to the second. However, the first method creates complexity in the coordinate-address transformation process, i.e., the conversion of pixel coordinates into storage addresses in the DDR4 SDRAM. Consequently, the computational complexity of the first method of data organization reduces the overall encryption speed. The second method requires less hardware resources, compared to that in the first one, for the coordinate-address transformation. Since the amount of image data is relatively modest in comparison to the space of the DDR4 SDRAM, the second method is chosen to optimize the speed of the hardware.

Encryption controller

Encryption Controller (EC) oversees the entire operation of Global Computing, Image Computing Cores, and Memory Read/Write Coordinator. Specifically, the EC consists of subsystems with different responsibilities, that is, the Register Controller manages the read and write operations of Register Block; Global Controller coordinates the functions of Global Computing; Image Controller directs the activities of all Image Computing Cores; and the AXI4 Controller generates the control signals for the Memory Read/Write Coordinator.

Global Controller operates on the basis of a finite state machine (FSM) as depicted in Fig. 16. The AXI4 controller consists of two FSMs, as illustrated in Fig. 17 to manage the reading and writing processes of MIE-IP using the AXI4 protocol.

FPGA implementation

The MIE system in Fig. 9 is implemented on the Han Pilot Platform and tested as shown in Fig. 18a to confirm the operation of the proposed design. The Han Pilot Platform is a development kit based on the Intel Arria 10 SoC FPGA from Intel-Altera. In this work, the code is written in SystemVerilog, then synthesized and implemented using Quartus Prime 21.1 Standard Edition. Functionality testing and performance evaluation are conducted for the implementation.

FPGA-based system architecture

Figure 18b shows the details of the MIE system on the Han Pilot Platform for testing; where the Nios II CPU is used for general control and the JTAG-UART is utilized for console communication.

Hardware metrics

The encryption and decryption processes of the FPGA-based system are simulated using Questa *-Intel® FPGA Edition software. After verifying the MIE-IP through functional simulation, the hardware metrics are assessed to demonstrate the utilization of the design resources, including the number of adaptive logic modules (ALM), digital signal processing blocks (DSP), registers, and block memory bits. The performance of the design is evaluated, including speed (maximum frequency, throughput), efficiency (throughput-to-ALM ratio), and power consumption.

-

The throughput: Here, the throughput is computed for the maximum image data that goes through the hardware during the encryption time. It depends on, at maximum, the number of images that are encrypted at the same times, the size of the images, and the depth of the pixels as

$$\begin{aligned} Throughput=\frac{Q_{max} * K_{max}*M_{max}*N_{max}}{T_{total}} ~~\text {(Mbps)}, \end{aligned}$$(21)where \(T_{total}\) is the encryption time for all data by only the ICCs. \(T_{total}\) is counted by \(T_{total}=\frac{N_{iterations}*T_{N_{co}}*N_{co}}{f_{max}}\), in which \(f_{max}\) is the maximum frequency of the MIE-IP core; \(N_{iterations}\) is the number of iterations needed to encrypt all pixels of the largest image, \(N_{iterations}=\lceil \frac{M_{max}*N_{max}}{N_{co}}\rceil\); and \(T_{N_{co}}\) is the number of clock cycles to encrypt plain pixels \(p(i_k,j_k)\) and \(p(i'_k,j'_k)\) for \(k=1..K\) as

$$\begin{aligned} T_{N_{co}}=T_{SDRAM\_to\_SRAM}+T_{SRAM\_to\_ICCs}+T_{ICCs\_to\_SRAM}+T_{SRAM\_to\_SDRAM}, \end{aligned}$$(22)where \(T_{SDRAM\_to\_SRAM}\) takes six clock cycles to write \(p(i_k,j_k)\), \(p(i'_k,j'_k)\), \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\), \(c(i'_k,j'_k-1)\), \(p(i_k,j_k-1)\), \(p(i'_k,j'_k-1)\) for \(k=1..K\) from the DDR4 SDRAM to the SRAM; \(T_{SRAM\_to\_ICCs}\) is one clock cycle to read data from the SRAM to the ICCs; \(T_{ICCs\_to\_SRAM}\) is one clock cycle to write the output of the ICCs to the SRAM; \(T_{SRAM\_to\_SDRAM}\) are two clock cycles to write \(c(i_k,j_k)\) and \(c(i'_k,j'_k)\) back to the DDR4 SDRAM. Consequently, \(T_{N_{co}}\) is ten clock cycles, and substituting \(T_{N_{co}}\) into Eq.(21), the throughput is

$$\begin{aligned} Throughput=\frac{Q_{max} * K_{max}*M_{max}*N_{max}*f_{max}}{10N_{co}\lceil \frac{M_{max}*N_{max}}{N_{co}}\rceil } ~~\text {(Mbps)}, \end{aligned}$$(23)where \(f_{max}\) is the maximum frequency of MIE hardware, and it has been found that the critical path lies in the fixed-point multiplication of the chaotic map implementation (PCM Computing in Fig. 13) in this exemplar design; \(Q_{max}\) is the maximum number of bits representing a pixel; and K is the number of images encrypted simultaneously. In this work, all hardware components in the design were optimized for the highest speed.

-

The hardware efficiency: The hardware efficiency is computed as

$$\begin{aligned} Efficiency=\frac{Throughput}{ALMs} ~~\text {(Mbps/ALM)}. \end{aligned}$$(24)Tables 23 and 24 summarize hardware metrics and power consumption. The throughput is 998.2 Mbps measured with the value of the simulation parameters as \(f_{max}=51.99\) MHz, \(K_{max}=8\), \(M_{max}=1024\), \(N_{max}=1024\), \(Q_{max}=24\), and \(N_{co}=8\). These metrics indicate that the exemplar design requires modest resources on the FPGA chip, while it achieves high throughput, as given in Table 24. The low efficiency is obtained because there is hardware sacrification to optimize the speed with the use of pipeline technique. Note from Table 23 that the amount of 96.1% RAM blocks is required for the entire MIE system, which is composed of several hardware modules such as NiOS, DRAM Controller, etc., for performing an end-to-end application. In fact, BRAM utilization is only counted for MIE-IP solely at 0.516%. The amount of hardware utilization for MIE-IP is less than 10% of the resource of the Intel Arria 10 SoC FPGA chip. The power consumption has been measured using the software tools by the FPGA chip manufacturer after complete compilation, placement, and routing.

-

The latency: Considering the hardware latency, the analysis is based on the configurations of the proposed structures shown in Fig. 1 and their flowcharts in Fig. 4. The latency is defined as the time duration between the input of the first pixel of an image and the output of the first ciphertext pixel. It should be noted that the Bit Interleaving, Bit Pre-Processing (BPP), and Diffusion blocks are implemented with combinational logic (without flip-flops); therefore, these blocks operate combinationally and do not consume any clock cycles. Only the Permutation block requires memory read and write operations for pixel data. The S-box is also implemented with combinational logic and functions as a codebook; however, its delay depends on how it is utilized in each structure. Specifically, the S-boxes in Structures 1 and 2 do not incur any delay, whereas the S-boxes in Structure 3 require time for reading and writing pixel values from and to memory during the substitution process. In Structure 3, after the permutation and diffusion processes are completed for all pixels of an image, the substitution process is performed sequentially by reading the pixel values from memory and writing them back after substitution. Therefore, the latency of the proposed structures can be analyzed as follows. For Structures 1 and 2: The pixels in image \(I_k\) are processed sequentially. In the exemplar design, both pixels \(p(i_k,j_k+1)\) and \(c(i_k,j_k-1)\) can be read simultaneously because they are stored in the same word of the SRAM. Therefore, only one SRAM read cycle is required. As described above, each permutation requires one SRAM read and one SRAM write cycle, denoted as \(T_{reading\_SRAM}\) and \(T_{writing\_SRAM}\), respectively. The latency is calculated as the time interval from when the first pixel p(1, 1) enters the encryption core to when the first ciphertext pixel c(1, 1) is produced. However, since the permutation operates over the entire image-space range, the overall latency corresponds to the time needed to complete encryption of all pixels in the smallest image across \(N_e\) encryption rounds. The size of the smallest image is used in this calculation because its ciphertext pixels are returned first. Therefore, the latency of Structures 1 and 2 for \(N_e\) rounds of encryption is given by

$$\begin{aligned} Latency_{1,2}=N_e*M_{min}*N_{min}*\left( 2*T_{reading\_SRAM}+T_{writing\_SRAM}\right) ~~~~~~~~(clock~cycles) \end{aligned}$$(25)where \(M_{min}\) and \(N_{min}\) are the size of smallest image in terms of the numbers of pixels. For Structure 3: Encryption is divided into two stages. In the first stage, all pixels are completely permuted and diffused. In the second stage, the pixels are substituted using the S-box. The total latency is determined by the time required to complete the permutation and diffusion processes over \(N_e\) rounds, plus the time required for \((N_e - 1)\) rounds of substitution. Therefore, the latency of Structure 3 is given by

$$\begin{aligned} Latency_3=\left( 2*N_e-1\right) *M_{min}*N_{min}*\left( T_{reading\_SRAM}+T_{writing\_SRAM}\right) ~~~~~~~~(clock~cycles) \end{aligned}$$(26)In FPGA, it only needs one clock cycle to read/write to SRAM, which means \(T_{reading\_SRAM}=T_{writing\_SRAM}=1/f_{max}\). Equations (25) and (26) become

$$\begin{aligned} Latency_{1,2}=\frac{3*N_e*M_{min}*M_{min}}{f_{max}}~~~(seconds) \end{aligned}$$(27)and

$$\begin{aligned} Latency_3=\frac{2*\left( 2*N_e-1\right) *M_{min}*N_{min}}{f_{max}}~~~(seconds) \end{aligned}$$(28)In the exemplar hardware design with \(N_e=5\), \(M_{min}=N_{min}=256\) (see Table 1), the estimated latencies using Eq. (27) for Structures 1 and 2 and Eq. (28) for Structure 3 are \(Latency_{1,2}\approx 18.908\) milliseconds and \(Latency_{3}\approx 22.689\) milliseconds, respectively.

-