Abstract

In this article, we introduce an enhanced version of the log-logistic model, termed the Kumaraswamy alpha-power log-logistic (KAPLL) distribution. The KAPLL model expands upon the traditional log-logistic distribution and several well-established distributions. We investigate the mathematical properties of the KAPLL model, highlighting its ability to effectively model various aging and failure criteria. The KAPLL distribution exhibits remarkable flexibility in modeling various types of hazard rate behaviors. It is capable of accommodating a wide range of shapes, including increasing, decreasing, J-shaped, reversed J-shaped, bathtub-shaped, inverted bathtub-shaped, and even more complex forms such as decreasing–increasing–decreasing failure rates. The KAPLL distribution is characterized by its capacity to exhibit both symmetric and asymmetric shapes in its density function. The proposed KAPLL model overcomes key limitations of existing LL-based generalizations by offering enhanced flexibility in modeling diverse hazard rate shapes and tail behaviors. We estimate the KAPLL parameters using eight classical estimation methods. Comprehensive simulation results are presented and ranked to identify the most effective approach for estimating KAPLL parameters, which we believe will be of great interest to engineers and applied statisticians. To further demonstrate the versatility of the KAPLL distribution, we analyze five real-world datasets from reliability, engineering, biomedical, and environmental sciences, highlighting its flexibility relative to other extensions of the log-logistic model. Likelihood ratio tests conducted across five real datasets confirm that the KAPLL model provides a statistically significant improvement over the baseline log-logistic distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The quality of statistical analysis is heavily influenced by the choice of probability distribution. Consequently, significant efforts have been devoted to developing generalized classes of probabilistic distributions, along with relevant statistical methodologies. In practice, these distributions find applications across various fields, including insurance, actuarial science, investment, risk analysis, business and economic research, reliability engineering, chemical engineering, medicine, demography, and sociology, among others.

The statistical literature has introduced several newly generated classes of univariate continuous distributions by incorporating additional shape parameters into baseline models. These extended distributions have garnered the attention of statisticians due to their flexibility and capability to model both monotonic and non-monotonic real-life data. Notable examples include the Marshall–Olkin-G (MO-G)1, McDonald-G2, beta-G3, Kumaraswamy-G4, Kumaraswamy Marshal–Olkin-G (KMO-G)5, Weibull-G6, Weibull Marshall Olkin-G7, Marshall–Olkin alpha power-G (MOAP-G)8, and Kumaraswamy alpha-power-G (KAP-G)9, among others.

The classical log-logistic (LL) distribution, often referred to as the Fisk distribution in the context of income distribution literature10,11,12, has also been called the Pareto Type III distribution by Arnold13, who introduced an additional location parameter. Furthermore, the LL distribution is a special case of the Burr-XII distribution14 and the Kappa distribution15, both of which have been applied to streamflow and precipitation data. Additional details about the LL model can be found in16.

The LL model can be understood as the probability model for a random variable whose logarithm follows a logistic distribution. It serves as an alternative to the log-normal distribution, as it features a hazard rate (HR) function that initially increases before subsequently decreasing.

The LL distribution has been widely applied in survival analysis and reliability engineering due to its mathematical simplicity and closed-form expressions for key functions. However, it suffers from limited flexibility in capturing diverse failure rate shapes, particularly those observed in real-life data such as bathtub-shaped or unimodal HR shapes. These limitations restrict its applicability in complex failure-time scenarios.

In recent years, several researchers have introduced different generalized forms of the LL distribution to enhance its capability and flexibility in modeling time-to-event data. Some notable improvements to the LL model include the alpha-power transformed-LL17, transmuted LL (TLL)18, Marshall–Olkin LL (MOLL)19, McDonald-LL (McLL)20, Kumaraswamy Marshall–Olkin LL (KMOLL)21, additive Weibull lL (AWLL)22, extended Weibull LL23, extended-LL (ExLL)24, Zografos–Balakrishnan LL25, odd Lomax LL26, extended Poisson LL27, extended odd Weibull LL28, skew LL29, cubic transmuted LL30, LL Ailamujia31, and generalized Kavya–Manoharan LL32 distributions.

Although numerous generalizations of the LL distribution have been proposed in recent decades—such as the KLL, MOLL, KMOLL, McLL, BLL, AWLL, ExLL, and others—many of these models suffer from limited shape control, parameter redundancy, or complex forms that hinder interpretability or estimation. Most notably, while prior models aim to accommodate various HR shapes, few offer a unified and analytically tractable framework that simultaneously supports a wide spectrum of real-world behaviors, including heavy tails, multimodality, and diverse failure rate patterns (e.g., increasing-decreasing-increasing or inverted bathtub). To address these gaps and the limitations of the traditional LL model, we propose the Kumaraswamy alpha power log-logistic (KAPLL) distribution as a novel and flexible extension of the LL model. The KAPLL distribution introduces a synergistic blend of the Kumaraswamy and alpha power transformations into the LL baseline, allowing for superior control over skewness, tail behavior, and HR dynamics. Unlike existing counterparts, the KAPLL model can produce monotonic (increasing or decreasing), non-monotonic (unimodal, bathtub), and complex hybrid shapes within a concise parameter space. Furthermore, it retains analytical tractability for key functions such as the cumulative distribution function (CDF), probability density function (PDF), and HR function, enabling easier application in real-life survival and reliability analyses. Moreover, in many practical applications, these models show poor fitting when the data exhibit heavy tails or multimodality. On the other hand, the five-parameter KAPLL model that accommodates a wide spectrum of HR shapes, while retaining tractable mathematical properties, making it both theoretically sound and practically applicable. These advantages position the KAPLL distribution as a significant advancement over earlier LL-based distributions, filling crucial gaps in flexibility, interpretability, and practical applicability.

The proposed KAPLL dstribution is constructed by applying the KAP transformation introduced by9 to the LL distribution. The KAP transformation introduces boundedness, enhances control over skewness, and allows for more flexible tail behavior and hazard rate shapes. These features collectively enable the KAPLL distribution to capture a wider range of failure rate patterns and improve goodness-of-fit in practical applications. The development of the KAPLL model is thus motivated by the need for increased adaptability in modeling time-to-event data across various domains.

Other motivations for introducing the KAPLL distribution include the following: (i) The KAPLL model can effectively represent various HR function (HRF) shapes, including increasing, J-shaped, decreasing, reversed J-shaped, bathtub, modified bathtub, decreasing–increasing–decreasing, and unimodal forms; (ii) The KAPLL distribution encompasses several known lifetime submodels, as outlined in Table 2; (iii) It is particularly suitable for modeling skewed real-life data that may not be adequately represented by other established distributions; (iv) The KAPLL distribution has applications across various fields, including survival analysis, public health, industrial reliability, biomedical studies, and engineering; and (v) Empirical results demonstrate that the KAPLL distribution outperforms many well-known LL distributions in the context of five real-life data examples.

In addition to the theoretical development and practical applications of the KAPLL model, this study provides a comprehensive comparison of eight classical and modern estimation methods for estimating its parameters. Through an extensive Monte Carlo simulation study, the performance of each method is rigorously evaluated under varying sample sizes and parameter settings. This analysis not only highlights the robustness and limitations of each estimator but also serves as a valuable guideline for engineers and applied statisticians when selecting the most appropriate estimation technique for real-world data. By offering practical insights into estimator behavior, this work bridges the gap between theoretical modeling and applied implementation, reinforcing the KAPLL model’s utility in diverse reliability and survival analysis contexts.

The rest of the paper is organized into seven sections. The KAPLL distribution is investigated in Section “The KAPLL distribution”. In Section “Properties of the KAPLL distribution”, some key properties of the KAPLL distribution are explored. Inference about the KAPLL parameters is presented in Section “Estimation methods”. Section “Applications to real-world data” provides simulation studies. In Section Comparative evaluation and discussion, we present five real-world data applications. Section “Conclusions and future perspectives” gives some conclusions.

The KAPLL distribution

The KAPLL model and its special cases are presented in this section. The CDF of the two-parameter LL model has the form

where \(\lambda\) and \(\beta\) are the scale and shape parameters, respectively.

The LL PDF reduces to

The KAPLL distribution is constructed based on the KAP-G family, which is specified by the CDF

where \(\alpha\), a and b are shape parameters.

The corresponding PDF of the KAP-G class is expressed by

Table 1 provides the special sub-families of the KAP-G family. Further information about the KAP-G family can be explored in9.

Inserting (1) in Eq. (3), the CDF of the KAPLL distribution follows as

The PDF corresponding to (5) takes the form

The HRF of the KAPLL distribution reduces to

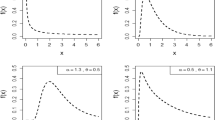

Table 2 provides five important special sub-models of the new KAPLL distribution. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the flexibility and diverse behavior of the KAPLL distribution through its PDF and HRF, respectively, for various combinations of parameter values with \(\lambda =1\). Figure 1 displays several shapes of the PDF, highlighting the ability of the KAPLL distribution to capture a wide range of distributional forms. These include both symmetric and asymmetric density profiles, as well as unimodal structure. This flexibility is essential in modeling real-world data sets that deviate from classical symmetric assumptions, enabling better fit and inferential accuracy across diverse applications.

Figure 2 presents the corresponding HRF plots under the same parameter settings, showcasing the model’s capability to accommodate various failure rate behaviors. The plots include increasing, decreasing, J-shaped, bathtub-shaped, revested J-shaped, decreasing-increasing-decreasing and inverted bathtub-shaped hazard functions. These are critical features in survival and reliability analysis, where the failure rate of a system or component may not follow a monotonic trend. For example, the bathtub-shaped curve, which characterizes early failures, a stable period, and wear-out failures, is effectively captured by the KAPLL model in several of the plotted scenarios.

These visualizations support our claim that the KAPLL distribution is a highly adaptable model capable of fitting data with diverse statistical characteristics. The inclusion of these graphical representations thus reinforces the theoretical properties derived and provides intuitive understanding of the model’s practical relevance.

Remark 1

A statistical model is said to be identifiable if distinct parameter values produce distinct probability distributions. For the KAPLL distribution, identifiability can be established by examining the form of the PDF, which depends on a combination of one-to-one transformations involving the parameters \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\lambda\) , a, and b. Specifically, the transformation \(\left( 1+\lambda /x^\beta \right) ^{-1}\), the exponential component \(\alpha ^{\left( 1+ \lambda /x^\beta \right) ^{-1}}\), and the power transformations controlled by a and b are all one-to-one functions over their domains. Consequently, the joint behavior of these terms makes the overall PDF injective in its parameter vector, supporting theoretical identifiability.

In addition to the analytical justification, we provide empirical support. Figure 1 displays the plots of the KAPLL density for twelve different combinations of parameters. It is clearly observed that each parameter set produces a distinct shape for the density function, confirming that the model is identifiable in practice. These variations are evident in the location, scale, skewness, and tail behavior of the plotted densities.

Properties of the KAPLL distribution

This section provides some key features of the KAPLL model.

Linear representation

Mead et al.9 provided a useful mixture representation of the PDF of the KAP-G class. According to9, the KAP-G density reduces to

Using the PDF and CDF of the LL model and after some algebra, the KAPLL density takes the form

It can also be rewritten simply as follows

where \(\zeta _{k+1} (x)=(k+1)\, g(x) \,(G(x))^k\) is the exponentiated-LL density with power parameter and \((k+1)>0\), and

Quantile function, skewness and kurtosis

The quantile function (QF) of the KAPLL distribution follows by inverting Eq. (5) as

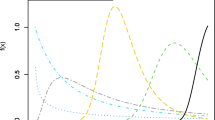

where \(\xi =\left\{ \left( \alpha -1\right) \left[ 1-\left( 1-u\right) ^\frac{1}{b}\right] ^\frac{1}{a}\right\}\), U follows the uniform (0,1) distribution. The effects of the shape parameters on the skewness (SK) and kurtosis (KU) can be studied by using the QF. The Bowley SK (BSK)39 is one of the earliest SK measures, which is defined by BSK\(=\frac{Q(3/4)+Q(1/4)-2*Q(1/2))}{Q(3/4)-Q(1/4)}\). The Moors KU (MKU)40 is defined based on octiles as follows MKU\(=\frac{Q(3/8)-Q(1/8)+Q(7/8)-Q(5/8)}{Q(6/8)-Q(2/8)}\). The BSK and MKU plots of the KAPLL distribution for some selected choices of \(\alpha ,\) \(\lambda ,\) a and b as functions of the parameter a are displayed in Fig. 3. The plots of the BSK and MKU are obtained for \(\lambda =1\), \(\beta =2\) and \(b=1.5\) and different values of a and \(\beta\). The plots show that the flexible shapes of the two measures of the KAPLL distribution, which depend on the values of a and \(\beta\). Furthermore, the KAPLL distribution can be used in modeling positive and negative SK as well as symmetric real-life data.

Some moments

The rth moment of X can be obtained from Eq. (7) as

After calculating the integration, the rth moment of X follows as

The mean of X , say, \(\mu _{X}\), follows from (9) with \(r=1\).

The rth incomplete moment of the KAPLL distribution has the form

After some algebra, \(I_r(t)\) reduces to

where\(\ _2F_1\left( \frac{-r}{\beta }+1,k+2;\frac{-r}{\beta }+2;-\lambda t^{-\beta }\right)\) is the hyper geometric function.

The mean residual life of the KAPLL distribution at age t has the form

where \(d=\left( 1+\frac{\lambda }{t^\beta }\right) ^{-1},\ \eta =\left( \alpha ^d-1\right) /\left( \alpha -1\right)\) and \(I_1\left( t\right)\) is the first incomplete moment.

The mean inactivity time of the KAPLL distribution takes the form

The Lorenz (L)41, Bonferroni (B) and Zenga (Z) curves are considered the most important inequality curves and have some applications in insurance, medicine, reliability, and economics.

The L curve is defined for the KAPLL distribution as follows

The B and Z inequality curves can be determined, through their relationship with the L curve, by the following formulae42

The moment generating function (MGF) of the KAPLL model is defined by

Based on Eq. (7), we can write

After some algebra, the MGF of the KAPLL follows as

The values of \(\mu _{X}\) are obtained by two ways, for some values of \(\alpha , \lambda , \beta\), a and b, based on the numerical integration (NI) and summation(SUM) formula. Table 3 display the values of \(\mu _{X}\) using the NI and SUM expressions at truncated M terms, where M refers to the truncated terms from the SUM (9). Table 3 shows that the SUM in (9) converges to the NI of \(\mu _{X}\) for all values of \(\alpha , \lambda , \beta\), a and b when M increases. Furthermore, the \(\mu _X\), variance (VA), SK, and KU of the KAPLL distribution are obtained numerically for some choices of \(\alpha , \lambda , \beta\), a and b. The values of the four measures are reported in Table 4. The numerical values in Tables 3 and 4 are computed by the R program43.

Rényi and m-entropies

The entropy of a random variable X is a measure of the uncertain variation.

The Rényi entropy is defined by

Using Equation (7), the Rényi entropy of the KAPLL model takes the form

The \(m-\)entropy, say, \(L_X(m)\), is defined by

Hence, using (10), the \(m-\)entropy of the KAPLL model follows as

Order statistics

Let \(X_1\), \(X_2\), ...\(X_n\) be a random sample of size n and let \(X_{1:n},...,X_{n:n}\) be their associated order statistic. Then, the PDF of the ith order statistics, say, \(X_{i:n}\), which is denoted by \(f_{x_{i:n}}(x)\), reduces to

Substituting (5) and (6) in (11), the ith order statistic of the KAPLL distribution follows as

where \(d=\left( 1+\lambda \, x^{-\beta }\right) ^{-1}\) and \(\eta =\left( \alpha ^{d}-1\right) /\left( \alpha -1\right)\). After some algebra, we obtain

The last equation can be expressed as

where \(h_{s+1}(x)=(s+1)g(x)[G(x)]^s\) is the exponentiated-LL density with power parameter \((s+1)>0\), and

Estimation methods

In this section, we use eight methods to estimate the KAPLL parameters namely: the maximum likelihood estimators (MLE), least-squares estimators (LSE), weighted LSE (WLSE), maximum product of spacing estimators (MPSE), percentiles-estimators (PCE), Cramér von Mises estimators (CRVME), Anderson–Darling estimators (ADE), and right tail ADE (RADE). These estimation methods have been widely used in the literature for flexible and complex distributions (see, e.g.,44,45,46,47).

Let \(x_1\), \(x_2\), \(\ldots\), \(x_n\) be a random sample from KAPLL distribution then the logarithm of the likelihood function, say, (\(\ell\)), becomes

where \(d_i=\left( 1+\lambda \, x_i^{-\beta }\right) ^{-1}\) and \(\eta _i=\left( \alpha ^{d_i}-1\right) /\left( \alpha -1\right)\).

To obtain the MLE of a, b, \(\alpha\), \(\lambda\) and \(\beta\), the first derivatives of \(\ell\) are obtained with respect to the parameters. These derivatives are

and

The LSE and WLSE of the KAPLL parameters \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\lambda\), a and b can be obtained by minimizing

where \(\nu _i\)=1 in case of the LSE approach and \(\nu _i=(n+1)^2(n+2)/[i(n-i+1)]\) in case of the WLSE approach. Furthermore, the LSE and WLSE follow by solving the nonlinear equations

where

and

where \(d_{i:n}=\left( 1+ \lambda \, x_{i:n}^{-\beta }\right) ^{-1}\) and \(\eta _{i:n}=\left( \alpha ^{d_{i:n}}-1\right) /\left( \alpha -1\right)\).

The MPSE is an alternative approach to the MLE48,49. The uniform spacings of a random sample of size n from the KAPLL distribution ar defined by

where \(D_i=D_i(\alpha ,\beta ,\lambda ,a,b)=F(x_{i:n})-F(x_{i-1:n})\) be the uniform spacing for \((i=1,...,n+1)\), and \(F(x_{0:n})=0\), \(F(x_{n+1:n})=1\), and \(\sum _{i=1}^{n+1}D_i=1\).

The MPSE of the KAPLL parameters are determined by solving the non-linear equations

where \(\delta _s(x_{i:n})=0\) are defined in (13–17) for \(s=1,2,3,4,5.\)

The CRVME can be obtained based on the difference between the estimates of the CDF and the empirical CDF . The CRVME of the KAPLL parameters minimize the following function

which also follow by solving

The ADE of the KAPLL parameters are obtained by minimizing

which can be found as solutions of the system

The RADE of the KAPLL parameters \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\lambda\), a and b are obtained by minimizing the following function

They can also be obtained from the non-linear equations

The PCE of \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\lambda\), a and b can be determined by minimizing the quantity

Numerical simulations

This sections gives detailed simulation results to explore the behavior and performances of the introduced estimation methods in estimating the KAPLL parameters based on the following three measures namely: the mean square errors (MSE), \(MSE\ =\frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N}{(\hat{\varvec{\theta }_i}- \varvec{\theta })}^2,\) average absolute biases (|BIAS|), \(|BIAS|\ =\frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N}{|\hat{\varvec{\theta }_i}-\varvec{\theta }|},\) and mean relative errors (MRE), \(MRE\ =\frac{1}{N}\sum _{i=1}^{N}{|\hat{\varvec{\theta }_i}-\varvec{\theta }|}/{\varvec{\theta }}\), where \(\varvec{\theta }=(\alpha , \, \beta , \, \lambda , \, a,\, b)^{T}\).

Several sample sizes and parameters combinations are considered, i.e., n = {50, 100, 250, 500}, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 0.5, 0.9, 1.2)T, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 0.5, 1.1, 1.2)T, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 0.5, 1.3, 1.2)T, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 0.75, 0.6, 0.3)T, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 0.75, 0.6, 0.5)T, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 0.75, 1.3, 0.3)T, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 1, 0.6, 0.3)T, θ = (0.5, 1.5, 1, 0.6, 0.5)T. We generated \(N = 5000\) random samples based on the QF in (8) using the R software43.

Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 give the findings of simulations including the |BIAS|, MSE, and MRE for the eight estimation approaches. The results show that the values of |BIAS|, MSE and MRE decrease with the increase of n, indicating that the estimators demonstrate desirable asymptotic behavior in simulation, although no formal proof of consistency is provided. Hence, the introduced estimation methods perform very well in estimating the KAPLL parameters. Generally, based on simulation results, the ordering performance of the estimators is as follow: WLSE, MPSE, ADE, RADE, LSE, CRVME, ADE, and PCE. This order confirms the superiority of the MPS estimation method with overall sore of 38.

Applications to real-world data

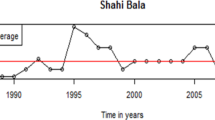

This section demonstrates the importance and practical applicability of the proposed KAPLL distribution by analyzing five real-world datasets from reliability, engineering, biomedical, and environmental sciences. In particular, these datasets are employed as independent validation tools to rigorously assess the generalizability and empirical relevance of the proposed model beyond the controlled settings of the simulation study. Our objective is to highlight the enhanced flexibility of the KAPLL model compared to existing extensions of the LL distribution. To this end, we focused on two primary criteria for selecting these datasets: their benchmark use in the literature and their practical relevance to real-world reliability, engineering, biomedical, and environmental contexts. All five datasets have been previously analyzed in well-established studies, allowing for meaningful comparisons with existing lifetime models. Additionally, they represent diverse practical scenarios—including mechanical component failure, stress testing of materials, biomedical, and environmental analysis—where flexible distributions are essential. Furthermore, the selected datasets exhibit, as shown from Table 14, a range of skewness values—both negative and positive—highlighting the diverse distributional characteristics that the proposed KAPLL model aims to capture. These datasets were chosen specifically to highlight the modeling flexibility and adaptability of the proposed KAPLL distribution across a variety of realistic reliability applications. The datasets vary in size, with 40, 63, 119, 300, and 576 observations, respectively. This section demonstrates the importance and practical applicability of the proposed KAPLL distribution by analyzing five real-world datasets. Our objective is to showcase the enhanced flexibility of the KAPLL model compared to existing extensions of the LL distribution. To this end, we selected the datasets based on two primary criteria: (1) their frequent use as benchmarks in the literature, and (2) their practical relevance to real-world reliability, engineering, biomedical, and environmental problems. All five datasets have been previously analyzed in well-established studies, enabling meaningful comparisons with existing lifetime models. Moreover, they reflect a variety of practical scenarios—including mechanical component failure, material stress testing, and fracture toughness analysis—where flexible distributions are critical for accurate modeling.

The first dataset is addressed by50, and it contains 40 observations of time to failure (\(10^3h\)) of turbocharger of one type of engine. The data are: 3.5, 1.6, 5.4, 4.8, 6.0, 7.0, 6.5, 7.3, 8.0, 7.7, 8.4, 3.9, 2.0, 5.0, 6.1, 5.6, 8.1, 6.5, 7.3, 7.1, 7.8, 2.6, 8.4, 4.5, 5.8, 5.1, 6.3, 7.3, 6.7, 7.7, 8.3, 7.9, 8.5, 4.6, 3.0, 5.3, 8.7, 6.0, 9.0, 8.8.

The second dataset is studied by51, and it consists of 63 observations of strengths of 1.5 cm glass fibers. The data are: 0.93, 0.55, 1.25, 1.49, 1.36, 1.52, 1.61, 1.58, 1.64, 1.73, 1.68, 1.81, 0.74, 2, 1.04, 1.39, 1.27, 1.49, 1.53, 1.59, 1.61, 1.66, 1.68, 1.76, 1.82, 2.01, 0.77, 1.11, 1.28, 1.42, 1.5,1.54, 1.60, 1.62, 1.66, 1.69, 1.76, 1.84, 2.24, 0.81, 1.13, 1.29, 1.48, 1.50, 1.55, 1.61, 1.62,1.66, 1.70, 1.77, 1.84, 0.84, 1.24, 1.30, 1.48, 1.51, 1.55, 1.61, 1.63, 1.67, 1.7, 1.78, 1.89.

The third dataset contains 119 observations of fracture toughness MPa m1/2 data from the material Alumina (\(AL_2O_3\))52. The data are: 5.5, 5, 4.9, 6.4, 5.1, 5.2, 5.2, 5, 4.7, 4, 4.5, 4.2, 4.1, 4.56, 5.01, 4.7, 3.13, 3.12, 2.68, 2.77, 2.7, 2.36, 4.38, 5.73, 4.35, 6.81, 1.91, 2.66, 2.61, 1.68, 2.04, 2.08, 2.13, 3.8, 3.73, 3.71, 3.28, 3.9, 4, 3.8, 4.1, 3.9, 4.05, 4, 3.95, 4, 4.5, 4.5, 4.2, 4.55, 4.65, 4.1, 4.25, 4.3, 4.5, 4.7, 5.15, 4.3, 4.5, 4.9, 5, 5.35, 5.15, 5.25, 5.8, 5.85, 5.9, 5.75, 6.25, 6.05, 5.9, 3.6, 4.1, 4.5, 5.3, 4.85, 5.3, 5.45, 5.1, 5.3, 5.2, 5.3, 5.25, 4.75, 4.5, 4.2, 4, 4.15, 4.25, 4.3, 3.75, 3.95, 3.51, 4.13, 5.4, 5, 2.1, 4.6, 3.2, 2.5, 4.1, 3.5, 3.2, 3.3, 4.6, 4.3, 4.3, 4.5, 5.5, 4.6, 4.9, 4.3, 3, 3.4, 3.7, 4.4, 4.9, 4.9, 5.

The fourth dataset comprised 300 adult Egyptian individuals with documented age (ranging from 18 to 85 years) and sex, equally distributed between males and females. All participants underwent high-resolution three-dimensional multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) imaging of the neck at the Radiodiagnosis Department, Ain Shams University Hospital, Egypt, for clinical indications unrelated to neck disorders, and were classified as Group I. Individuals in the preadolescent age group were excluded, as skeletal structures at this stage are not reliable for sex determination due to the absence of secondary sexual characteristics, which only emerge following hormonally driven bone remodeling during puberty. This dataset was studied by53. The data are: 33.7, 36, 38.3, 33.7, 32, 34.4, 38.5, 38.2, 33.2, 32.3, 32.5, 30.5, 32.7, 38.2, 28.4, 29.5, 32, 37, 32, 31.4, 27.7, 30.9, 33.5, 36.3, 29.5, 31.2, 31.4, 33.6, 33, 33.7, 36.8, 28.9, 34.7, 31.9, 32.8, 28.3, 38.1, 36.2, 36.9, 32.5, 37.7, 41, 31.9, 36.3, 40.7, 38.7, 35.5, 36.1, 36.9, 35.9, 35.6, 33.2, 34.8, 31.7, 39.5, 39.9, 34.7, 35.9, 34.3, 39.7, 36, 38.5, 29.9, 35.4, 36.4, 35, 33.5, 36.6, 35, 30.1, 31, 36.4, 34.7, 33.9, 36.1, 39.7, 38.9, 36.6, 32.6, 39.3, 33.8, 34.2, 32.5, 38.8, 36, 36, 35, 37.8, 41.3, 32.4, 38.1, 37.6, 36.3, 36.8, 36.5, 38, 33.4, 36, 43.8, 41.1, 38, 36.7, 35.9, 31.3, 33.5, 37, 33, 33.8, 35.8, 40.7, 40.9, 36.7, 37.4, 33.4, 31.6, 37.5, 36.5, 39.2, 31.1, 35.9, 29.5, 35.7, 37.5, 37.4, 37.5, 37.4, 40, 42.3, 32.5, 35.5, 45.1, 39, 32.6, 33, 41.7, 38.5, 37.3, 34.4, 37.8, 31.7, 37.9, 34.3, 32.2, 34.2, 35.1, 44.6, 33.4, 30.3, 30.5, 29.4, 30.9, 31.7, 28.5, 32.6, 32.6, 33.2, 29.1, 32.1, 26.5, 29.4, 35.3, 29.3, 32.3, 29.4, 33.3, 30.4, 27.9, 25.7, 32.3, 30.4, 27.6, 24.3, 30.8,29.7, 24.2, 25, 29.7, 30.3, 28.8, 31, 25.9, 30.1, 26.1, 27.3, 27.2, 28.6, 34.6, 27.8, 26.5, 26.8, 29.3, 31.6, 30.1, 30.8, 29.2, 30.9, 30, 33.2, 30.5, 33.1, 35.8, 30.2, 29.7, 26.8, 29.5, 32.8, 30.3, 34.2, 27, 30.3, 36.3, 33.5, 31.7, 31.1, 31.5, 26.6, 31.3, 31.2, 31.2, 30.3, 26.2, 29.4, 34.5, 29.5, 28.6, 34.2, 40.5, 34.1, 36.6, 35.2, 36.2, 30.7, 38.3, 34, 38.8, 29.7, 31.2, 26.1, 33.3, 30.5, 28.9, 26.2, 30, 34.3, 25.9, 27.8, 28.5, 34.8, 26.5, 24.4, 28.5, 28.9, 30.9, 24.6, 30.5, 31.2, 33.8, 29.5, 34.8, 26.7, 29.5, 33, 33.4, 26.3, 26.1, 35, 31.9, 34.4, 26.8, 31, 29.5, 25.4, 30.8, 29.3, 24.9, 29.2, 33.9, 33.3, 26.6, 23.3, 37.4, 31, 31, 27.2, 31.9, 29, 40.1, 31.2, 32.9, 29, 29.9, 32.9, 26.9, 33.6, 29.5, 26.4, 28.9, 32.7, 38, 34.3

The fifth dataset represents wind speed data extracted from a comprehensive meteorological dataset recorded at 15-minute intervals by the USDA-ARS Conservation and Production Laboratory (CPRL), Soil and Water Management Research Unit (SWMRU) research weather station located in Bushland, Texas. Although the original dataset includes several meteorological variables, only the wind speed (m/s) variable is analyzed in this study. A subsample covering six consecutive days in early 2019 was selected, resulting in a total of 576 observations. The measurements were collected under standardized reference conditions using calibrated sensors installed at a height of 2 meters, with quality control and gap-filling procedures applied as described in the original data source. The dataset is publicly available at: https://doi.org/10.15482/USDA.ADC/1526433. The data are: 10.590, 10.560, 10.800, 10.190, 9.570, 9.100, 9.920, 10.010, 9.820, 9.330, 9.290, 8.740, 9.320, 8.930, 8.000, 8.720, 9.010, 9.640, 9.170, 9.500, 9.700, 9.370, 9.520, 9.130, 9.030, 9.490, 8.890, 7.860, 7.790, 8.330, 7.010, 7.120, 6.370, 5.890, 7.230, 7.030, 6.420, 6.600, 7.000, 6.850, 6.290, 6.790, 6.070, 5.910, 5.620, 5.620, 5.740, 5.150, 5.340, 4.880, 4.690, 4.590, 4.750, 4.780, 4.530, 4.310, 4.200, 4.050, 3.790, 3.840, 3.380, 3.670, 3.250, 2.850, 2.820, 2.680, 2.930, 2.580, 2.720, 1.950, 1.670, 1.320, 1.290, 0.720, 0.740, 0.410, 0.530, 0.850, 0.970, 1.210, 1.900, 1.600, 1.690, 1.360, 0.720, 0.960, 0.660, 0.390, 0.870, 0.990, 0.900, 1.500, 1.900, 2.170, 2.230, 2.880, 2.860, 2.910, 2.760, 2.130, 1.400, 1.400, 1.750, 1.820, 2.010, 2.370, 2.600, 2.550, 2.530, 2.250, 2.390, 2.110, 1.770, 1.790, 1.490, 1.370, 1.310, 1.930, 1.780, 1.670, 1.390, 1.070, 1.050, 1.270, 1.550, 2.390, 2.710, 2.600, 2.050, 1.840, 2.210, 2.580, 2.870, 3.360, 3.390, 3.280, 3.620, 3.300, 3.180, 3.070, 3.440, 3.000, 1.930, 0.920, 1.650, 1.890, 1.190, 1.950, 1.470, 1.400, 0.970, 1.170, 1.110, 0.810, 0.870, 0.690, 1.570, 4.050, 4.290, 4.500, 4.270, 4.290, 4.000, 3.740, 3.380, 3.200, 2.870, 1.830, 1.500, 1.470, 1.560, 2.450, 2.740, 2.510, 2.390, 2.550, 2.050, 2.490, 2.590, 2.940, 3.250, 3.170, 2.580, 2.580, 2.360, 2.780, 2.390, 2.390, 3.010, 2.910, 2.320, 1.310, 1.310, 0.610, 1.350, 1.280, 1.280, 1.200, 1.950, 1.860, 1.490, 1.060, 0.740, 1.310, 1.790, 1.850, 1.540, 1.770, 1.950, 1.970, 1.790, 1.490, 2.030, 2.490, 3.070, 2.570, 2.630, 2.840, 2.750, 2.790, 3.050, 2.250, 2.160, 2.530, 3.190, 3.700, 2.890, 2.520, 2.620, 3.350, 3.620, 2.930, 3.790, 4.000, 4.090, 4.230, 3.810, 3.980, 3.650, 3.600, 3.580, 3.710, 3.710, 4.080, 3.960, 4.160, 4.450, 4.940, 5.460, 5.680, 4.950, 5.450, 5.550, 5.070, 5.490, 5.640, 5.560, 5.890, 6.510, 6.120, 5.330, 5.780, 4.320, 2.570, 2.570, 2.630, 2.130, 0.940, 1.020, 1.640, 1.640, 1.750, 1.840, 1.570, 1.680, 1.790, 1.340, 1.340, 1.430, 1.480, 1.530, 1.620, 1.770, 1.730, 1.000, 1.530, 1.330, 1.110, 0.500, 1.130, 1.830, 1.950, 1.850, 1.490, 1.190, 2.220, 2.140, 1.830, 1.550, 1.640, 2.010, 3.440, 3.010, 3.270, 3.520, 3.260, 3.180, 3.260, 3.960, 4.230, 4.350, 4.050, 4.120, 4.360, 3.810, 3.610, 4.490, 4.910, 4.260, 3.570, 2.960, 2.930, 2.030, 2.830, 2.900, 2.280, 2.650, 2.220, 2.280, 2.450, 2.440, 1.750, 1.250, 1.550, 1.950, 2.300, 3.180, 3.030, 2.650, 2.570, 2.580, 2.180, 2.030, 1.930, 1.740, 1.950, 1.540, 1.900, 1.640, 0.990, 1.460, 1.070, 1.520, 1.400, 1.490, 1.680, 1.390, 0.710, 1.100, 0.990, 0.370, 0.510, 0.620, 1.170, 0.970, 0.690, 0.710, 0.400, 0.770, 0.990, 1.080, 1.050, 1.570, 2.110, 2.290, 2.240, 2.090, 1.900, 2.160, 2.250, 1.880, 1.940, 1.790, 1.380, 1.660, 1.900, 2.260, 2.560, 2.690, 3.090, 3.440, 3.320, 3.430, 3.840, 3.660, 2.720, 2.570, 2.200, 1.900, 1.790, 1.930, 2.010, 1.760, 1.430, 1.150, 1.230, 1.750, 1.990, 2.180, 2.050, 2.740, 3.420, 3.130, 2.670, 3.320, 3.600, 3.520, 2.960, 3.020, 3.680, 3.680, 3.600, 3.130, 2.540, 2.780, 2.950, 3.000, 2.940, 3.610, 4.280, 4.680, 5.010, 5.360, 5.360, 4.700, 5.170, 4.920, 5.120, 4.110, 5.090, 6.060, 5.870, 5.730, 6.070, 5.540, 5.370, 4.930, 4.910, 4.860, 4.590, 4.180, 3.650, 3.740, 2.800, 2.920, 3.050, 2.930, 3.070, 2.670, 2.210, 2.820, 2.760, 2.680, 2.420, 3.000, 3.060, 3.220, 3.420, 3.410, 3.540, 3.420, 3.340, 3.560, 4.100, 3.340, 3.350, 4.010, 3.810, 4.520, 5.360, 5.728, 5.957, 4.963, 4.780, 3.966, 4.138, 3.928, 4.480, 5.243, 5.162, 4.681, 5.241, 5.265, 3.824, 3.782, 3.646, 3.913, 3.463, 3.274, 3.169, 3.609, 3.217, 3.267, 4.124, 4.654, 4.716, 4.056, 4.198, 3.854, 3.744, 3.764, 3.340, 3.539, 3.792, 3.480, 3.267, 2.980, 3.523, 4.555, 4.876, 4.954, 4.473, 4.863, 4.638, 4.485, 4.887, 5.889, 5.840, 6.566, 5.105, 5.478, 6.173, 7.829, 7.721, 7.546, 7.863, 8.140, 8.590, 9.010, 7.907, 5.997, 6.118, 5.842, 5.954, 6.111, 5.570, 4.627, 3.836, 3.148, 3.445, 3.483, 3.538, 2.752, 2.612, 2.618, 2.200, 2.810, 3.516, 4.258, 4.700, 5.358, 5.013, 5.081, 4.970, 4.517, 6.434, 6.619, 7.068, 6.562, 6.873, 6.312, 6.648, 6.907, 9.350, 9.910, 10.270.

The descriptive statistics summarized in Table 14 underscore the diversity among the five datasets in terms of size (n), central tendency, variability, and distributional shape. Notably, the skewness values range from negative to positive, indicating that the datasets are not symmetrically distributed. This variation reflects the complexity often encountered in real-world reliability and engineering data. Therefore, it is crucial to employ a flexible distribution capable of capturing such heterogeneity.

The proposed KAPLL model is particularly well-suited for this purpose, as it can accommodate a wide range of skewness and kurtosis levels, making it a strong candidate for modeling these datasets effectively.

The fits of the KAPLL distributions is compared with some existing LL distributions namely: the alpha power transformed LL (APTLL)17, KMOLL21, McLL20, AWLL22, alpha power LL (APLL)54, TLL18, and LL distributions.

The performance of the fitted distributions is explored using some measures including the Akaike information criterion (AIC), consistent Akaike IC (CAIC), Hannan–Quinn IC (HQIC), Bayesian IC (BIC), (\(-\ell\)), where \(\ell\) the maximized log-likelihood, as well as some statistics include the Cramér–Von Mises (\(W^{*}\)), Anderson-–Darling (\(A^{*}\)), Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) and the KS p-value (PV).

All numerical results in this section are calculated using the R software. Table 15 provides goodness-of-fit measures of the competing models for the five analyzed datasets. The results in this table indicate the superior fitting performance of the proposed KAPLL distribution over other existing LL extensions. The ML estimates and standard errors (SEs) for the models’ parameters are reported in Tables 16 and 17, for all datasets. Overall, the KAPLL distribution have the lowest values for goodness-of-fit criteria among all LL fitted models. Then, it could be chosen as the most adequate model for fitting the five datasets.

Furthermore, the visual fitting performance of the proposed KAPLL distribution is comprehensively assessed in Figs. 4 and 5. These figures present a detailed graphical comparison between the empirical data and the fitted KAPLL model through various diagnostic plots. Specifically, each panel includes the histogram of the observed dataset overlaid with the estimated PDF, the empirical and fitted CDF, and the probability–probability (PP) plots. These plots collectively illustrate how well the KAPLL model captures the overall distributional behavior of the data.

In addition, Figs. 6, 7 and 8 show the histogram-based visual comparison of the KAPLL model against several other competing lifetime distributions, including known extensions of the LL distribution. For each dataset, the histogram is overlaid with the fitted density curves from all candidate models. This comparative visualization allows for a clear, direct assessment of goodness-of-fit among the competing models.

From the visual evidence provided in all these figures, it is apparent that the KAPLL distribution consistently aligns more closely with the empirical data than the alternative models. Specifically, the KAPLL model’s density curves match the peaks, tails, and spread of the histograms more accurately; its CDF trace follows the empirical curves with minimal deviation; and the PP plots demonstrate that the fitted values are nearly perfectly aligned with the 45-degree reference line, indicating strong agreement between the observed and theoretical distributions. These visual diagnostics confirm the superior flexibility and accuracy of the KAPLL model in capturing the complex characteristics of the datasets, thereby validating its efficacy as a robust and generalizable extension of the LL family.

To validate the proposed KAPLL distribution beyond controlled simulations, we used five independent real-world datasets as external validation benchmarks. These datasets were chosen because they represent diverse domains (mechanical failure, material strength, and fracture toughness), cover a range of sample sizes (40–576), and exhibit different distributional shapes (positive skewness, heavy tails). By analyzing these datasets, we aimed to test the generalizability and robustness of the KAPLL model under practical conditions.

Table 18 presents the parameter estimates of the KAPLL distribution obtained using the eight estimation methods, along with the corresponding KS statistics and their associated PV for the five real datasets. Taken together, these analyses confirm that the datasets serve as effective validation tools: the KAPLL consistently adapts across domains, and the observed fit patterns are consistent with those obtained in the simulation study, thereby validating both the model and its estimation strategies. Based on the KS statistics and p-values, the CRVME method provides the best fit for Dataset 1, while the ML method performs best for Dataset 2. For Datasets 3, 4 and 5, the LS method yields the most favorable results. Overall, all estimation methods produce strong and consistent performance across the datasets, reinforcing the robustness and flexibility of the KAPLL model. Furthermore, the estimates derived from real data are largely consistent with the findings from the simulation study, where the WLSE method was most effective on average. Although WLSE is not always the top performer in the real data analysis, the observed variability is expected, as these results are based on single-sample evaluations, unlike the broader simulations that span various sample sizes and parameter configurations. These findings collectively confirm the practical utility of the KAPLL distribution and the adaptability of its estimation procedures to diverse data conditions.

Comparative evaluation and discussion

This comparative evaluation across validation datasets further strengthens the case for the KAPLL distribution. Unlike purely illustrative examples, these datasets act as independent benchmarks, confirming that the proposed model is not overfitted to simulated data but performs well in diverse empirical contexts.

The performance of the proposed KAPLL model was evaluated against several recent extensions of the LL distribution, including the APTLL, KMOLL, McLL, AWLL, APLL, TLL, and classical LL models. The comparison, based on criteria such as AIC, CAIC, HQIC, BIC, \(-\ell\), \(W^{*}\), \(A^{*}\), KS and PV statistics, consistently showed that the proposed model provided superior goodness-of-fit across multiple real-life datasets. This improvement can be attributed to the added flexibility introduced by the KAP transformation, which enable the model to capture complex hazard rate shapes—including bathtub and unimodal patterns—more effectively than existing models. Additionally, the KAPLL model retains closed-form expressions for its density and distribution functions, which is a practical advantage over more computationally intensive alternatives. These findings confirm that the proposed model not only enhances flexibility but also improves empirical performance, making it a valuable addition to the family of generalized LL distributions.

Furthermore, we conducted an ablation study to evaluate the performance of the proposed KAPLL model in comparison to its nested sub-models, as listed in Table 2. The models were assessed using several goodness-of-fit criteria, including the \(-\ell\), \(W^{*}\), \(A^{*}\), KS statistics, and the corresponding PV. We intentionally excluded information-based criteria such as AIC, CAIC, BIC, and HQIC from this comparison, as these metrics are influenced by the number of model parameters, which could bias the evaluation in favor of simpler models. Instead, we focused on distributional goodness-of-fit measures that assess how well the models capture the empirical behavior of the data. The comparison was carried out across all five real datasets. As presented in Table 19, the KAPLL model consistently achieved lower goodness-of-fit statistics and higher p-values, indicating a superior fit relative to its sub-models.

Figures 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 display the quantile-quantile (QQ) plots comparing the empirical quantiles of the observed data with the theoretical quantiles of the KAPLL model and its nested sub-models across the five datasets. A model that fits well will produce points that closely follow the 45-degree reference line. As evident from the plots, the KAPLL distribution consistently shows the closest alignment to this line in all cases, visually confirming its superior goodness-of-fit and flexibility relative to its sub-models.

To justify the necessity of the proposed KAPLL distribution, which extends the classical LL model by introducing three additional shape parameters (\(\alpha\), a, and b), we conducted a rigorous ablation study using the LRT. This test compares the KAPLL model against its nested sub-model, the LL distribution, across five real-world datasets. Since the KAPLL distribution is a generalization of LL distribution, the LRT statistic follows a chi-square distribution with 3 degrees of freedom. The LRT statistic is calculated as \(w = 2(\ell _{\text {KAPLL}} - \ell _{\text {LL}})\), where \(\ell _{\text {KAPLL}}\) and \(\ell _{\text {LL}}\) are the maximumized log-likelihoods of the KAPLL and LL models, respectively. As shown in Table 20, the LRT statistics are highly significant across all five datasets, with very small p-values, indicating strong evidence in favor of the KAPLL model.

These findings provide strong statistical evidence that the added complexity of the KAPLL model translates into meaningful improvements in fit, validating both its theoretical advancement and practical utility in modeling complex data patterns. Thus, the validation datasets not only highlight the superiority of the KAPLL model over its sub-models but also establish its empirical relevance across varied real-world scenarios.

Conclusions and future perspectives

In this paper, a flexible five-parameter model called the Kumaraswamy alpha-power log-logistic (KAPLL) distribution is introduced. The hazard function of the KAPLL model provides monotonic and non-monotonic failure rates, as well as its density can be symmetric and asymmetric. The KAPLL distribution exhibits various types of hazard rate behaviors including increasing, decreasing, J-shaped, reversed J-shaped, bathtub-shaped, inverted bathtub-shaped, and even more complex forms such as decreasing–increasing–decreasing failure rates. Its mathematical features are explored. Furthermore, the KAPLL parameters are estimated by eight approaches of estimation. A simulation study is performed to compare these approaches and showed that the weighted least-squares (WLS) method outperforms all considered estimation methods. Hence, our results, confirms the superiority of the WLS approach in estimating the KAPLL parameters. Finally, the practical importance of the KAPLL distribution is addressed through the analysis of five real-life datasets from reliability, engineering, biomedical, and environmental sciences. Goodness-of-fit statistics and graphical assessments illustrated that the KAPLL model consistently provides a superior fit compared to other log-logistic-based models. Furthermore, this superiority was substantiated through a comprehensive ablation study and likelihood ratio testing. Compared to its nested sub-models, the KAPLL distribution consistently achieved better goodness-of-fit across all datasets. These findings highlight the practical value of the additional shape parameters in enhancing model flexibility and capturing complex data behaviors. Despite its flexibility and strong empirical performance, the KAPLL distribution has some limitations due to its five-parameter structure. In particular, parameter estimation can be challenging for small or low-variability datasets, and the risk of overfitting may be higher than that of simpler models. Users should weigh these considerations carefully when applying the model.

Building upon the foundation of the KAPLL distribution, several promising directions can be pursued to expand its scope and practical relevance across diverse domains. Potential avenues for future research include: Enhancing existing parameter estimation techniques, such as maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods, particularly in the presence of censored data, to increase the model’s reliability and precision in real-world applications. Investigating non-parametric or semi-parametric adaptations of the model, which could offer greater flexibility and broader applicability. Further integrating Bayesian frameworks for both inference and model selection, which may provide deeper insights and comparative advantages over traditional methods. Developing a discrete analogue of the KAPLL distribution to facilitate its use in modeling count data, thereby extending its utility to a wider array of applied settings.

Data availability

All datasets analyzed during this study are included within the article.

References

Marshall, A. W. & Olkin, I. A new method for adding a parameter to a family of distributions with application to the exponential and Weibull families. Biometrika84, 641–652 (1997).

Alexander, C., Cordeiro, G. M., Ortega, E. M. & Sarabia, J. M. Generalized beta-generated distributions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 56, 1880–1897 (2012).

Eugene, N., Lee, C. & Famoye, F. Beta-normal distribution and its applications. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 31, 497–512 (2002).

Cordeiro, G. M. & de Castro, M. A new family of generalized distributions. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 81, 883–898 (2011).

Alizadeh, M. et al. The Kumaraswamy Marshal–Olkin family of distributions. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 23, 546–557 (2015).

Bourguignon, M., Silva, R. B. & Cordeiro, G. M. The Weibull-G family of probability distributions. J. Data Sci. 12, 53–68 (2014).

Korkmaz, M. Ç. et al. The Weibull Marshall–Olkin family: Regression model and application to censored data. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 48, 4171–4194 (2019).

Nassar, M., Kumar, D., Dey, S., Cordeiro, G. M. & Afify, A. Z. The Marshall–Olkin alpha power family of distributions with applications. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 351, 41–53 (2019).

Mead, M. E., Afify, A. & Butt, N. S. The modified Kumaraswamy Weibull distribution: Properties and applications in reliability and engineering sciences. Pak. J. Stat. Oper. Res. 16, 433–446 (2020).

Fisk, P. R. The graduation of income distributions. Econom.: J. Econom. Soc. 29, 171–185 (1961).

Dagum, C. A model of income distribution and the conditions of existence of moments of finite order. Bull. Int. Stat. Inst. 46, 199–205 (1975).

Shoukri, M. M., Mian, I. U. H. & Tracy, D. S. Sampling properties of estimators of the log-logistic distribution with application to Canadian precipitation data. Can. J. Stat. 16, 223–236 (1988).

Arnold, B. C. Pareto Distrib. (International Co-operative Publication House, Fairland, Maryland USA, 1983).

Burr, I. W. Cumulative frequency functions. Ann. Math. Stat. 13, 215–232 (1942).

Mielke, P. W. & Johnson, E. S. Three-parameter kappa distribution maximum likelihood estimates and likelihood ratio tests. Mon. Weather Rev. 101, 701–709 (1973).

Kleiber, C. & Kotz, S. Statistical size distributions in economics and actuarial sciences (John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

Aldahlan, M. A. Alpha power transformed log-logistic distribution with application to breaking stress data. Adv. Math. Phys. 2020, 1–9 (2020).

Aryal, G. R. Transmuted log-logistic distribution. J. Stat. Appl. Prob. 2, 11–20 (2013).

Gui, W. Marshall-Olkin extended log-logistic distribution and its application in minification processes. Appl. Math. Sci. 7, 3947–3961 (2013).

Tahir, M. H., Mansoor, M., Zubair, M. & Hamedani, G. G. McDonald log-logistic distribution with an application to breast cancer data. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 13, 65–82 (2014).

Cakmakyapan, S., Ozel, G., Gebaly, Y. M. H. E. & Hamedani, G. G. The Kumaraswamy Marshall–Olkin log-logistic distribution with application. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 17, 59–76 (2018).

Hemeda, S. Additive Weibull log logistic distribution: Properties and application. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Math. Stat. 3, 8–15 (2018).

Abouelmagd, T. H. M. et al. Extended Weibull log-logistic distribution. J. Nonlin. Sci. Appl. 12, 523–534 (2019).

Alfaer, N. M., Gemeay, A. M., Aljohani, H. M. & Afify, A. Z. The extended log-logistic distribution: Inference and actuarial applications. Mathematics 9, 1386 (2021).

Ramos, M. W. A., Cordeiro, G. M., Marinho, P. R. D., Dias, C. R. B. & Hamedani, G. G. The Zografos–Balakrishnan log-logistic distribution: Properties and applications. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 12, 225–244 (2013).

Cordeiro, G. M., Afify, A. Z., Ortega, E. M., Suzuki, A. K. & Mead, M. E. The odd Lomax generator of distributions: Properties, estimation and applications. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 347, 222–237 (2019).

Almamy, J. A. Extended Poisson log-logistic distribution. Int. J. Stat. Probab 8, 56–69 (2019).

Afify, A. Z., Hussein, E. A., Alnssyan, B. & Mahran, H. A. The extended log-logistic distribution: Properties, inference, and applications in medicine and geology. J. Stat. Appl. Probab 12, 1155–1580 (2023).

Gaire, A. K. & Gurung, Y. B. Skew log-logistic distribution: Properties and application. Stat. Trans. 25, 43–62 (2024).

Rahman, M. M., Darwish, J. A., Shahbaz, S. H., Hamedani, G. G. & Shahbaz, M. Q. A new cubic transmuted log-logistic distribution: Properties, applications, and characterizations. Adv. Appl. Stat. 91, 335–361 (2024).

Ali, I. et al. On a transmuted distribution based on log-logistic and Ailamujia hazard functions with application to lifetime data. Lobachevskii J. Math. 45, 1557–1569 (2024).

Afify, A. Z., Abdelall, Y. Y., AlQadi, H. & Mahran, H. A. The modified log-logistic distribution: Properties and inference with real-life data applications. Contemp. Math. 6, 862–902 (2025).

Kariuki, V., Wanjoya, A., Ngesa, O. & Alqawba, M. A flexible family of distributions based on the alpha power family of distributions and its application to survival data. Pak. J. Stat. 39, 237–258 (2023).

Mahdavi, A. & Kundu, D. A new method for generating distributions with an application to exponential distribution. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods. 46, 6543–6557 (2017).

Gupta, R. C., Gupta, P. L. & Gupta, R. D. Modeling failure time data by Lehman alternatives. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 27, 887–904 (1998).

Kariuki, V. et al. Properties, estimation, and applications of the extended log-logistic distribution. Sci. Rep. 14, 1420967 (2024).

De Santana, T. V. F., Ortega, E. M., Cordeiro, G. M. & Silva, G. O. The Kumaraswamy-log-logistic distribution. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 11, 265–291 (2012).

Rosaiah, K., Kantam, R. R. L. & Kumar, S. Reliability test plans for exponentiated log-logistic distribution. Econom. Quality Control. 21, 279–289 (2006).

Kenney, J. F. & Keeping, E. S. Mathematics of statistics. Princeton New Jersey. Part 1, 3rd edn, 101–102 (1962).

Moors, J. J. A quantile alternative for kurtosis. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Ser. D: Stat..37, 25–32 (1998).

Lorenz, M. O. Methods of measuring the concentration of wealth. Publ. Am. Stat. Assoc..9, 209–219 (1905).

Arcagni, A. & Porro, F. The graphical representation of the inequality. Dipart. Stat. Metodi Quantitat. Work. Papers. 37, 419–437 (2014).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R foundation for statistical computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed: 10 June 2025).

Ahmad, A., Alsadat, N., Rather, A. A., Meraou, M. A. & El-Din, M. M. A novel statistical approach to COVID-19 variability using the Weibull-inverse Nadarajah Haghighi distribution. Alexandria Eng. J. 105, 950–962 (2024).

Ahmad, K. et al. Statistical inference on the exponentiated moment exponential distribution and its discretization. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 17, 1–14 (2024).

Ahmad, A. et al. Novel family of probability generating distributions: Properties and data analysis. Phys. Scripta 99, 1–19 (2024).

Qayoom, D., Rather, A. A., Alsadat, N., Hussam, E. & Gemeay, A. M. A new class of Lindley distribution: System reliability, simulation and applications. Heliyon 10, 1–31 (2024).

Cheng, R. C. H. & Amin, N. A. K. Estimating parameters in continuous univariate distributions with a shifted origin. J. Royal Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.) 45, 394–403 (1983).

Cheng, R. C. H., & Amin, N. A. K. (1979). Maximum product-of-spacings estimation with applications to the lognormal distribution. Math report, 791.

Xu, K., Xie, M., Tang, L. C. & Ho, S. L. Application of neural networks in forecasting engine systems reliability. Appl. Soft Comput. 2, 255–268 (2003).

Smith, R. L. & Naylor, J. A comparison of maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimators for the three-parameter Weibull distribution. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. C: Appl. Stat. 36, 358–369 (1987).

Nadarajah, S. & Kotz, S. On the alternative to the Weibull function. Eng. Fract. Mech. 74, 451–456 (2007).

Abdelkader, A. et al. Hyoid bone-based sex discrimination among Egyptians using a multidetector computed tomography: Discriminant function analysis, meta-analysis, and artificial intelligence-assisted study. Sci. Rep. 15, 2680 (2025).

Malik, A. S. & Ahmad, S. P. An extension of log-logistic distribution for analyzing survival data. Pak. J. Stat. Oper. Res. 16, 789–801 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This Project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under grant no. (IPP: 293-662-2025). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Funding

This Project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia under grant no. (IPP: 293-662-2025). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Ahmed Z. Afify, Mohamed E. Mead, Abdussalam Aljadani; Data curation: Mohamed E. Mead, Abdulaziz S. Alghamdi, Enayat M. Abd Elrazik; Formal analysis: Mohamed E. Mead, Hamada H. Hassan; Investigation: Hamada H. Hassan, Abdussalam Aljadani; Methodology: Ahmed Z. Afify, Hamada H. Hassan, Enayat M. Abd Elrazik; Resources: Abdussalam Aljadani, Abdulaziz S. Alghamdi; Software: Ahmed Z. Afify, Hamada H. Hassan; Validation: Ahmed Z. Afify, Abdulaziz S. Alghamdi; Visualization: Abdulaziz S. Alghamdi, Enayat M. Abd Elrazik; Writing—original draft: Ahmed Z. Afify, Mohamed E. Mead, Hamada H. Hassan; Writing—review & editing: Ahmed Z. Afify, Abdussalam Aljadani, Enayat M. Abd Elrazik. All authors contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Afify, A.Z., Mead, M.E., Hassan, H.H. et al. A flexible extension of the log-logistic model with diverse failure rate shapes and applications. Sci Rep 16, 3266 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34460-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34460-y