Abstract

Two main issues in ethical consumption attract attention: environmental and labor issues. However, few studies have compared the conditions and effects that contribute to ethical purchasing behavior. To fill this gap, we conducted two studies targeting the Japanese food industry. In Study 1, we examined consumers who are accustomed to ethical consumption and clarified the product characteristics valued by consumers with high awareness of ethical issues. In Study 2, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of product concepts of environmental and labor issues on coffee purchase intentions. Study 1 confirmed that environmental and labor issues are emphasized for coffee, whereas recycling is emphasized for tea. This difference is due to the difference in production countries (coffee: developing countries, tea: Japan) and packaging materials (coffee: paper cups, tea: PET bottles). Study 2 showed that labor issues had a greater impact on purchase intention and willingness to pay than that of environmental issues owing to the adoption of producers’ photographs. This study complemented existing literature by comparing the conditions and effects of environmental and labor issues on ethical purchasing behavior. Considering the limited resources of companies and limited ability of consumers to process information, understanding predictive factors is extremely crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growth of modern capitalism has caused a wide range of environmental and social ills (Carrington et al., 2016; Stringer et al., 2020). To achieve sustainable economic development, governments in most developed countries have made ethical consumption a priority issue (Kossmann and Gómez-Suárez, 2018). Ethical consumption is defined as conscientious consumption that considers personal and moral beliefs concerning health, society, and the natural environment (Oh and Yoon, 2014). Similarly, global companies have aimed to build a positive brand image by developing ethical products (Chatterjee et al., 2021). In response to this social demand, consumers are beginning to consider the ethical validity of their purchasing behavior (Yoon and Park, 2021). Purchasing behavior based on this set of values is called ethical consumption and is defined as “conscientious consumption that fulfills consumers’ civic responsibility by voluntarily engaging and helping socially responsible firms based on personal and moral beliefs” (Yoon, 2020). Younger consumers, such as millennials (Johnson and Chattaraman, 2019) and Generation Z (Robichaud and Yu, 2022), have especially strong ethics attitudes. In the backdrop of social media, criticism and boycotts of brands with unethical businesses are conspicuous (Djafarova and Foots, 2022). Consequently, 43% of global consumers stated that they chose products based on sustainability and environmental and ethical factors (Global Data, 2021).

In terms of products, the two main issues in ethical consumption that attract attention are environmental and labor issues. Such moral issues are no longer confined to the realm of politics but also permeate marketing (Park, 2018). In other words, consumers demand products from companies that address these issues. For instance, the food industry is increasing its focus on sustainability (Bangsa and Schlegelmilch, 2020), particularly regarding coffee. A growing number of roasters are aiming to increase product value while improving the environment of origin and the treatment of workers (Vicol et al., 2018). In academic research, the existing literature on ethical consumption has mainly focused on environmental (Ghali, 2021; Konuk, 2019; Kumar et al., 2022; Kushwah et al., 2019; Lee and Lim, 2020; Mohd Suki, 2016; Newton et al., 2015; Sreen et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2020) and labor issues (Balasubramanian and Soman, 2019; Gillani et al., 2021; Koos, 2021; Ladhari and Tchetgna, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Nicholls and Opal, 2005; O’Connor et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). This indicates that both industry and academia recognize these two issues as the cornerstones of ethical consumption. Ideally, to solve both problems concurrently and with limited resources, prioritization is essential, as the time and costs incurred in dealing with ethical issues place a heavy burden on companies. Moreover, extreme ethical emphasis hinders a positive customer experience; thus, it is important to determine which factors are particularly effective (Davies and Gutsche, 2016). However, few studies have compared the conditions and effects that contribute to ethical purchasing behavior (Balasubramanian and Soman, 2019; Ghali, 2021; Gillani et al., 2021; Koos, 2021; Konuk, 2019; Kumar et al., 2022; Kushwah et al., 2019; Ladhari and Tchetgna, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Lee and Lim, 2020; Mohd Suki, 2016; Newton et al., 2015; Nicholls and Opal, 2005; O’Connor et al., 2017; Sreen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2020).

To fill this gap, in this study, we conducted two studies targeting the Japanese food industry. This study aimed to clarify the effects and conditions of environmental and labor issues on ethical consumption, targeting the food—particularly coffee—industry. In Study 1, we targeted consumers who are accustomed to ethical consumption and clarified the product characteristics valued by consumers with high awareness of ethical issues. Even within the same food industry (i.e., coffee, tea), we focused on the possibility that effective factors for ethical consumption may differ and made comparisons. In the context of ethical consumption, respondents are susceptible to social desirability bias (Yamoah and Acquaye, 2019), causing them to overreact when presented with options. Hence, we adopted a pure recall approach that does not result in bias like the assisted recall approach that presents options (Kato, 2021). Consumers tend to overreact when presented with choices (Kardes et al., 2002). Factors that consumers perceive can be evaluated by not presenting options.

In Study 2, we conducted randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to examine the effects of environmental and labor issues on purchase intentions of coffee products. RCTs are a method wherein multiple groups are created through random assignment, each receiving different treatments, and the resulting differences in outcomes are assessed. RCTs, which are highly reliable in scientific validation, have found delayed application in the social sciences (Torgerson and Torgerson, 2008). However, many researchers have come to recognize the usefulness of RCTs, and the number of articles applying RCTs in the social sciences has recently increased (Cotterill et al., 2013; Merlin et al., 2022; Todd-Blick et al, 2020). While Study 1 equally evaluated all factors based on consumer perceptions, Study 2 focused on environmental and labor issues and directly compared effectiveness. Marketers can enhance product value by adding ethical concepts to traditional factors such as brand and performance (Jayawardhena et al., 2016). This study provides useful suggestions for strategy formulation.

Factors promoting ethical consumption

Factors that promote ethical consumption can be primarily categorized into two groups: consumer and product characteristics. This study focused on examining the latter. The existing documents are presented below.

Factors of consumer characteristics

Values for ethical consumption

The most influential factor in ethical consumption is environment-related intrapersonal values (Testa et al., 2021). Consumers with environmental concerns exhibit higher ethical consumption intentions (Cheung and To, 2019; Kushwah et al., 2019). Values for ethical consumption exhibit high explanatory power for purchase intention in the food industry (Asif et al., 2018; Sadiq et al., 2020). In addition, examining people who use ethical products on a daily basis (Fei et al., 2022) and understanding the mechanisms of consumer purchasing behavior (Quoquab et al., 2019) are important. However, such consumers are a global minority; although consumers acknowledge that environmental considerations play a role in their purchasing decisions, their actual consumption behaviors do not align with these decisions (Chaturvedi et al., 2021; Schäufele and Hamm, 2018).

Price and income

Ethical goods are priced higher than other goods. For example, coffee is purchased at a price approximately 30% higher than the typical transaction price, representing the respect for satisfactory working conditions on coffee farms (Shurvell, 2022). However, ethical consumption’s direct benefits are neither readily visible nor readily available (Farjam et al., 2019). Consumers generally make purchasing decisions based on the awareness of wanting to obtain the maximum value for the product price (Frank and Brock, 2018). Therefore, the price of goods eventually becomes a barrier to ethical consumption (Wiederhold and Martinez, 2018), and price burden is a major barrier, particularly for low-income consumers (Ran and Zhang, 2023; Schäufele and Hamm, 2018).

Subjective norms

Subjective norms refer to social pressures regarding whether to perform certain behaviors (Ajzen, 1991) and have long been recognized as the drivers of ethical consumption (Alsaad, 2021; Liu et al., 2021). Subjective norms such as opinion that organic food has health-promoting effects or expectations of a healthy lifestyle, drive ethical consumption (Sultan et al., 2020). The impact of this factor is particularly pronounced for Generation Z. Younger generations are digital natives, which increases their opportunities to monitor the behavior of others and publish information in real time. Ethical consumption by Generation Z is therefore driven by peer pressure through digital tools (Robichaud and Yu, 2022).

Factors of product characteristics

Environmental issues

Environmental concerns are commonly used as a direct predictor of purchase intention for ethical products (Kumar et al., 2022; Newton et al., 2015; Yue et al., 2020). In the food industry, consumers with environmental concerns tend to have higher willingness to pay (WTP) for ethically sourced and produced products (Konuk, 2019; Kushwah et al., 2019). Moreover, consumers scrutinize companies’ products to determine whether they are “really ethical or pretending to be ethical” (Bulut et al., 2021). Companies that continue to destroy the environment are actively pressured by consumers to develop products that meet the requirements of sustainable development (Ghali, 2021). Hence, companies are focusing on spreading awareness of environmental crises (Sreen et al., 2021), their brand image, and product attractiveness by providing ethical information (Mohd Suki, 2016). Product labels are an effective method of providing ethical information. Especially in the food industry, labels are the most used marketing tool by companies to inform consumers of product characteristics and are essential for promoting sustainable product choices (Cerri et al., 2018). Publicizing sustainable supply chains strengthens a company’s green image and ultimately influences consumer purchasing behavior (Lee and Lim, 2020).

Labor issues

The boycott of goods manufactured under questionable working conditions has been observed for over a century. For example, in 1899, a “white label” campaign was implemented to reward favorable working conditions in the department store fashion industry (Andorfer and Liebe, 2015). Since then, the emphasis has been on prohibiting illegal child labor and forced labor, improving safe and healthy working conditions, and promoting workers’ rights (Nicholls and Opal, 2005). Fair Trade, which has been attracting attention in recent years, is an international social movement that aims to alleviate poverty, mainly in developing countries, by changing the price mechanism of consumer goods by paying producers a premium higher than the market price (Koos, 2021). Even consumers who have never purchased Fair Trade products are willing and interested to learn about this concept (Balasubramanian and Soman, 2019). As such, Fair Trade knowledge provision reinforces intention to purchase ethically correct food (Berki-Kiss and Menrad, 2022). For example, consumers were willing to pay a 31% price premium for apples when they learned that the apples were from poorer areas (Wang et al., 2021). Fair Trade information is also effective in promoting the purchase of coffee (Lee et al., 2018), as Fair Trade purchasing experiences provide consumers with hedonic satisfaction (Ladhari and Tchetgna, 2017). As with environmental issues, adding the producer’s name and photo to the product label is an effective way to promote Fair Trade products (Gillani et al., 2021). Understanding and encouraging consumers to purchase Fair Trade products serves the significant goal of achieving safer working conditions and fair wages for workers globally (Lee et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2017).

However, these factors have been partially evaluated, and the magnitude of their effects has rarely been contrasted (Balasubramanian and Soman, 2019; Ghali, 2021; Gillani et al., 2021; Koos, 2021; Konuk, 2019; Kumar et al., 2022; Kushwah et al., 2019; Ladhari and Tchetgna, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Lee and Lim, 2020; Mohd Suki, 2016; Newton et al., 2015; Nicholls and Opal, 2005; O’Connor et al., 2017; Sreen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2020). Therefore, to make effective use of the limited resources of a company, it is important to extract factors from a bird’s-eye view, and then compare and verify their effects.

Empirical investigation

Study 1

Method

In Study 1, we targeted consumers accustomed to ethical consumption and clarified the product characteristics that consumers with high awareness of ethical issues value. An online survey was conducted from 21st to 25th October 2022 with 2132 people in their 20s to 60s in Japan. Participants were informed that this survey does not collect personal information, or information on participants’ sensitive thoughts, mental and physical conditions, or body parts, such as blood or cells. An informed consent agreement was signed before the survey started. In addition to age, the target audience included consumers who habitually purchase ethical products, such as food, coffee, and tea. The survey was distributed from a survey collaborators database held by Macromill, Inc., a Japanese research company. Of the 5000 people interviewed, 2868 did not meet the selection criteria and were excluded. As shown in Table 1, the data on gender and age were collected proportionally, and no bias was observed. The survey items consisted of the following nine items: (1) gender, (2) age, (3) marital status, (4) children, (5) annual household income, (6) purchasing habits of ethical products (option: none, food, coffee, tea), (7) awareness of daily ethical consumption (seven-point Likert scale; 1 = not aware of it at all, 7 = very conscious), (8) product features that show consideration for ethical issues (pure recall), and (9) involvement in ethical products (seven-point Likert scale). The objective variable of this study was (6), and the pure recall for extracting product ethical features was (7). There were no missing values, as responses to all survey items were mandatory.

To extract the factors from the product features that show consideration for ethical issues, natural language processing was used. As shown in Table 2, six factors and five words belonging to them were defined based on the frequency of their appearance in the data. The first factor was related to environment issues and the second is related to labor issues. Five of the most frequent nouns and adjectives related to each factor were set as words. Then, when any of these registered words were detected in the text, the mention flag (0/1) of the corresponding factor was added. Therefore, if multiple words belonging to the same factor were mentioned multiple times in one text, the flag remained at 1 (i.e., the number of occurrences was counted as 1). Japanese open-source software MeCab was used for morphological analysis and CaboCha was used for parsing.

We adopted regression models in which the objective variable was the awareness of daily ethical consumption (No. 1 in Table 3). The control variables were the attribute and psychological variables (Nos. 2–6 and 13), and the explanatory variables were the factor mention dummies (Nos. 7–12). Here, four models were built: Models 1, 2, 3, and 4 for all, food, coffee, and tea products, respectively. All models were variable selected by the stepwise method. The validity of the model was confirmed by R-squared. The analysis environment was the R statistical analysis software.

Results and discussion

As shown in Table 2, the most frequent factor was Package, which was detected in 389 out of 2132 responses. By product type, Package was the most frequently mentioned for food and tea, and Labor was the most frequently mentioned for coffee. Table 4 shows the results of the regression model. Confirming R-square, all models showed values close to 0.2, which was set as the threshold in many studies (Kenanidis et al., 2021; Taghipour et al., 2011); therefore, the models were reasonable. The overall results of Model 1 indicated that factor-mentioned dummies other than Environment and Package were significant at the 5% level. In contrast, product, food, and coffee showed differing results. Materials, Production_Area, and Recycle were significant for food, and Environment and Labor were significant for coffee. For tea, only Recycle was significant, showing a large difference from coffee. Therefore, coffee was the only product for which environmental and labor issues contributed to ethical awareness, and according to this model, the magnitudes of their effects were approximately the same.

We confirmed that even within the same food industry, the factors that promoted ethical consumption differed. The factors for ethical consumption of tea and coffee, which were consumed on a daily basis, were clearly different. Japanese consumers value environmental and labor issues for coffee, and recycling issues for tea, owing to the difference in the production and the packaging material used. Coffee is mainly produced in developing countries, where consumers are concerned about the working conditions (Koos, 2021; Ladhari and Tchetgna, 2017; Lee et al., 2018). Nevertheless, most of the tea is locally produced, and the working conditions on the farms maintain a certain level of quality. In terms of packaging materials, coffee is generally served in paper cups, but tea is served in PET bottles. Accordingly, for tea, there is a tendency to recognize the importance of recycling. The results suggest that it is important to determine the conditions under which the ethical factor exerts its effect.

Study 2

Method

In Study 2, we conducted an RCT to examine the impact of product concepts of environmental and labor issues on coffee purchase intentions. We conducted an online survey from 26th to 30th October, 2022, on 400 people in their 20s to 60s in Japan. Participants were informed that this survey does not collect personal information or information on participants’ sensitive thoughts, mental and physical conditions, or body parts, such as blood or cells. An informed consent agreement was signed before the survey started. The target audience consisted of consumers who habitually drink coffee. The participants were randomly divided into two groups, one of which was presented with environmental issues and the other with a product concept sheet of labor issues. The survey was distributed from a survey collaborators database held by Macromill, Inc., a Japanese research company. As shown in Table 5, as with Study 1, the surveys were collected with the intention to avoid any particular bias in terms of gender or age.

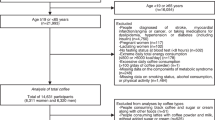

The survey items were as follows: (1) gender, (2) age, (3) marital status, (4) children, (5) frequency of drinking coffee at home (do not drink, less than one cup per week, one cup per week, two–three cups per week, four–six cups per week, one cup per day, and two or more cups per day), (6) purchase intention for the product on the concept sheet (rated on a seven-point Likert scale), and (7) WTP for the product on the concept sheet (rated on a seven-point Likert scale). Those who answered that they had no habit of drinking coffee in (5) were excluded. The objective variables for verification are (6) and (7), and the product concept sheet was presented before this question. As we prepared a screen that presents only the concept sheet in large size, each respondent was sure to see it. As shown in Fig. 1, the product concept sheet describes environmental and labor issues. After transitioning from the screen that presents the concept sheet, we asked (6) and (7) on the next survey screen. The chi-square test was applied to the matrix of group × purchase intention/group × WTP. The null hypothesis was “there is no difference in purchase intention/WTP in each group.” The significance level was 5%, and the analyses were performed using the R statistical analysis software. There were no missing values, as all responses to survey items were mandatory.

Results and discussion

Homogeneity of each group was important for conducting RCTs with high accuracy. As shown in Table 5, both groups were similar consumer groups considering the distribution of attributes. Upon applying the chi-square test to the matrix of each item × group, no significant difference was detected at the 5% level. Hence, this RCT was considered sufficiently valid. As shown in Table 6, labor issues (mean 4.105) scored higher than environmental issues (mean 3.995) based on the purchase intention results. According to the chi-square test, p < 0.05. The null hypothesis was rejected, and a significant difference was detected. As shown in Table 7, even in WTP, labor issues (mean 3.880) scored higher than environmental issues (mean 3.580). Similarly, significant differences were detected. Comparing the effect size with that of Cramer’s V, WTP tended to be larger than purchase intention.

In Study 1, both environmental and labor issues exhibited similar effects. However, in Study 2, labor issues were found to have a significant effect. This result had high validity, as the RCT was conducted under conditions that considered both environmental and labor issues. Consequently, consumers tended to prioritize human rights concerns over environmental concerns when making purchasing decisions. This divergence could be attributed to the influence of textual information and pictures related to human rights issues. Specifically, we believe that the effects of producer photographs warrant attention, as stimuli that allow the visibility of producer photographs carry significant implications for consumer psychology (Gillani et al., 2021). For example, cosmetic company Lush imprints its products with photographs and names of producers. E-mart, South Korea’s largest grocery chain, packages fruits and vegetables along with the names and faces of the respective farmers who cultivated the produce (Fuchs et al., 2022). Adopting this marketing communication approach for ethical products allows the efficient utilization of limited resources while promoting ethical consumption.

Conclusion and future work

Implications

In terms of products, two aspects have been identified as affecting ethical consumption: environmental issues (Ghali, 2021; Konuk, 2019; Kumar et al., 2022; Kushwah et al., 2019; Lee and Lim, 2020; Mohd Suki, 2016; Newton et al., 2015; Sreen et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2020) and labor issues (Balasubramanian and Soman, 2019; Gillani et al., 2021; Koos, 2021; Ladhari and Tchetgna, 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Nicholls and Opal, 2005; O’Connor et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). However, few studies have compared the conditions and effects of the two issues on ethical purchasing behavior. Considering the limited resources of companies and limited ability of consumers to process information, understanding additional effective factors is extremely significant. This study contributes by filling this gap. In Study 1, we confirmed that the effective factors differ depending on the target product, even within the same food industry and same beverage category. Coffee was shown to be prominent in the food industry as a product with environmental and labor issues contributing to consumer ethical awareness. Furthermore, Study 2 revealed that labor issues had a greater impact on purchase intention and WTP than environmental issues in the coffee market. To our knowledge, studies extracting the factors of ethical consumption for each target product and comparing the effects of effective factors are scarce. These results add to the missing literature on ethical consumption.

Overall, this study offers important implications for practitioners who want to promote ethical consumption. Practitioners wishing to promote ethical consumption need designs that allow consumers to perceive immediate significance. Consumers understand the gravity of labor and environmental problems; however, to date, these efforts have not borne expected outcomes. Many consumers express their importance on these ethical factors (Hernández and Kaeck, 2019; Yoon and Park, 2021); however, their concern does not lead to actual purchase behavior (Chaturvedi et al., 2021; Iweala et al., 2019; Testa et al., 2021). One of the reasons for this may be the inability to identify appropriate ethical factors for the target product. As this study showed, even within the same food industry, effective factors and their strengths and weaknesses vary. Therefore, it is important to comprehensively extract ethical factors from consumer perceptions and compare the effects of these factors for different target products. Implementing this process is expected to clarify the importance of ethical products from the consumer’s point of view.

Limitations and future work

This study had several limitations. First, the results are limited to Japan’s food industry; as such, generalization of the findings is limited. Thus, expansion to other countries and product categories is required. In particular, Japanese consumers have unique characteristics. For example, they evaluate the safety of food products quite strictly (Rupprecht et al., 2020). They also have a strong interest in maintaining social harmony and empathy (Karremans et al., 2011; Watanabe and Yabu, 2021). Considering differences in ethical factor effects due to national characteristics, it is necessary to compare the same effects in multiple countries.

Second, as this study focused on product aspects, differences in effects due to consumer attributes were not sufficiently examined. For example, women tend to engage in environmental protection behavior more frequently than men (Dzialo, 2017). Furthermore, financial constraints such as income and price should be carefully considered (Ran and Zhang, 2023; Schäufele and Hamm, 2018; Wiederhold and Martinez, 2018). While ethical products tend to be in a high price range (Shurvell, 2022), directly perceiving their consumer value is difficult, making it is necessary to examine the difference in effects depending on income (Farjam et al., 2019). High-status consumers believe that environmentally friendly practices are good and achievable. In contrast, low-status consumers tend to feel that their everyday actions have little impact on environmental issues (Kennedy and Givens, 2019). In this way, more precise evaluation is possible by considering the attributes that influence ethical consumption.

Third, this study did not close the gap between consumer attitudes and behavior. Although consumers report that environmental considerations are a factor in their purchasing decisions, their consumption behaviors do not correspond to these decisions (Chaturvedi et al., 2021; Schäufele and Hamm, 2018). Thus, the attitude–behavior gap in ethical consumption—despite being an important academic and practical topic —remains an unresolved paradox (Casais and Faria, 2022; Sun, 2020). Therefore, to strengthen the conclusions of this study, further verification using data on purchasing behavior in physical stores should be conducted in the future.

Fourth, in the RCT conducted in this study, the impact of human rights issues was found to be considerable, primarily due to the combined influence of text and photographs, which are inseparable. In other words, it is not feasible to determine from this study alone whether photographs depicting the producers are genuinely effective. Therefore, it is imperative to employ research designs that allow for the differentiation and comparison of the effectiveness of photographs alongside other forms of information in future studies.

Fifth, the consideration of the characteristics of workers projected in photographs was insufficient to enhance the effect of human rights issues on ethical consumption. The effect may vary depending on the gender, age, and even race of the worker.

Finally, the properties of stimuli that enhance the effectiveness of environmental issues were not investigated. This study introduced only the effect of producer photographs on labor issues. Similarly, environmental issues may have characteristics that are preferred by consumers, offering future research avenues.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-zxa-27gk. Please set the character code to UTF8.

Materials availability

Material used for product concept sheet in Study 2: coffee beans: https://www.pexels.com/ja-jp/photo/1695052/; forest: https://www.pexels.com/ja-jp/photo/957024/; solar panel: https://www.pexels.com/ja-jp/photo/4148472/; farmer: https://pixabay.com/photos/coffee-couple-farmer-agriculture-6951264/, https://pixabay.com/photos/farmer-jungle-tanzania-africa-4493421/ (last accessed October 4, 2023).

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Alsaad AK (2021) Ethical judgment, subjective norms, and ethical consumption: the moderating role of moral certainty. J Retail Consum Serv 59:102380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102380

Andorfer VA, Liebe U (2015) Do information, price, or morals influence ethical consumption? A natural field experiment and customer survey on the purchase of Fair Trade coffee. Soc Sci Res 52:330–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.02.007

Asif M, Xuhui W, Nasiri A, Ayyub S (2018) Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: a comparative analysis. Food Qual Prefer 63:144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.08.006

Balasubramanian P, Soman S (2019) Awareness regarding fair trade concept and the factors influencing the fair trade apparel buying behavior of consumers in Cochin City. J Strateg Mark 27:612–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2018.1464049

Bangsa AB, Schlegelmilch BB (2020) Linking sustainable product attributes and consumer decision-making: insights from a systematic review. J Cleaner Prod 245:118902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118902

Berki-Kiss D, Menrad K (2022) Ethical consumption: influencing factors of consumer´s intention to purchase Fairtrade roses. Clean Circ Bioecon 2:100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcb.2022.100008

Bulut C, Nazli M, Aydin E et al. (2021) The effect of environmental concern on conscious green consumption of post-millennials: the moderating role of greenwashing perceptions. Young Consumers 22:306–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-10-2020-1241

Casais B, Faria J (2022) The intention-behavior gap in ethical consumption: mediators, moderators and consumer profiles based on ethical priorities. J Macromark 42(1):100–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/02761467211054836

Carrington MJ, Zwick D, Neville B (2016) The ideology of the ethical consumption gap. Mark Theor 16:21–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593115595674

Cerri J, Testa F, Rizzi F (2018) The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J Clean Prod 175:343–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.054

Chatterjee S, Sreen N, Sadarangani P (2021) An exploratory study identifying motives and barriers to ethical consumption for young Indian consumers. Int J Econ Bus Res 22:127–148. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEBR.2021.116319

Chaturvedi P, Kulshreshtha K, Tripathi V (2021) Investigating the role of celebrity institutional entrepreneur in reducing the attitude-behavior gap in sustainable consumption. Manag Environ Qual 33(3):625–643. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-09-2021-0226

Cheung MFY, To WM (2019) An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J Retail Consum Serv 50:145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.04.006

Cotterill S, John P, Richardson L (2013) The impact of a pledge request and the promise of publicity: a randomized controlled trial of charitable donations. Soc Sci Q 94(1):200–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00896.x

Davies IA, Gutsche S (2016) Consumer motivations for mainstream “ethical” consumption. Eur J Mark 50:1326–1347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2015-0795

Djafarova E, Foots S (2022) Exploring ethical consumption of generation Z: theory of planned behavior. Young Consumers 23:413–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-10-2021-1405

Dzialo L (2017) The feminization of environmental responsibility: a quantitative, cross-national analysis. Environ Sociol 3:427–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2017.1327924

Farjam M, Nikolaychuk O, Bravo G (2019) Experimental evidence of an environmental attitude-behavior gap in high-cost situations. Ecol Econ 166:106434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106434

Fei S, Zeng JY, Jin CH (2022) The role of consumer’ social capital on ethical consumption and consumer happiness. SAGE Open 12(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221095026

Frank P, Brock C (2018) Bridging the intention–behavior gap among organic grocery customers: the crucial role of point‐of‐sale information. Psychol Mark 35(8):586–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21108

Fuchs C, Kaiser U, Schreier M, van Osselaer SM (2022) The value of making producers personal. J Retail 98(3):486–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2021.10.004

Ghali ZZ (2021) Motives of ethical consumption: a study of ethical products’ consumption in Tunisia. Environ Dev Sustain 23:12883–12903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01191-1

Gillani A, Kutaula S, Leonidou LC et al. (2021) The impact of proximity on consumer fair trade engagement and purchasing behavior: the moderating role of empathic concern and hypocrisy. J Bus Ethics 169:557–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04278-6

Global Data (2021) Continued growth in vegan lifestyle to set ethical precedence for personal care and household goods. Global Data, https://www.globaldata.com/continued-growth-vegan-lifestyle-set-ethical-precedence-personal-care-household-goods/#:~:text=According%2520to%2520GlobalData’s%2520latest%2520COVID,influence%2520in%2520the%2520current%2520situation*. (last Accessed 31 Dec 2022)

Hernández A, Kaeck DL (2019) Ethical judgment of food fraud: effects on consumer behavior. J Food Prod Mark 25(6):605–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2019.1621789

Iweala S, Spiller A, Meyerding S (2019) Buy good, feel good? The influence of the warm glow of giving on the evaluation of food items with ethical claims in the U.K. and Germany. J Clean Prod 215:315–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.266

Jayawardhena C, Morrell K, Stride C (2016) Ethical consumption behaviors in supermarket shoppers: determinants and marketing implications. J Mark Manag 32:777–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1134627

Johnson O, Chattaraman V (2019) Conceptualization and measurement of millennial’s social signaling and self‐signaling for socially responsible consumption. J Con Behav 18:32–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1742

Kardes FR, Sanbonmatsu DM, Cronley ML, Houghton DC (2002) Consideration set overvaluation: When impossibly favorable ratings of a set of brands are observed. J Consumer Psychol 12(4):353–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(16)30086-9

Kato T (2021) Brand loyalty explained by concept recall: recognizing the significance of the brand concept compared to features. J Mark Anal 9(3):185–198. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-021-00115-w

Kenanidis E, Stamatopoulos T, Athanasiadou KI, Voulgaridou A, Pellios S, Anagnostis P, Potoupnis M, Tsiridis E (2021) Can we predict the behavior of the scoliotic curve after bracing in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Τhe prognostic value of apical vertebra rotation. Spine Deform 9:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43390-020-00184-4

Kennedy EH, Givens JE (2019) Eco-habitus or eco-powerlessness? Examining environmental concern across social class. Sociol Perspect 62:646–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121419836966

Konuk FA (2019) Consumers’ willingness to buy and willingness to pay for fair trade food: the influence of consciousness for fair consumption, environmental concern, trust and innovativeness. Food Res Int 120:141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2019.02.018. Pubmed:31000224

Koos S (2021) Moralising markets, marketizing morality. The fair trade movement, product labeling and the emergence of ethical consumerism in Europe. J Nonprofit Public Sect Mark 33:168–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2020.1865235

Kossmann E, Gómez-Suárez M (2018) Decision-making processes for purchases of ethical products: gaps between academic research and needs of marketing practitioners. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 15:353–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-018-0204-8

Kumar N, Garg P, Singh S (2022) Pro-environmental purchase intention towards eco-friendly apparel: augmenting the theory of planned behavior with perceived consumer effectiveness and environmental concern. J Glob Fashion Mark 13:134–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2021.2016062

Kushwah S, Dhir A, Sagar M (2019) Ethical consumption intentions and choice behavior towards organic food. Moderation role of buying and environmental concerns J Clean Prod 236:117519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.350

Ladhari R, Tchetgna NM (2017) Values, socially conscious behavior and consumption emotions as predictors of Canadians’ intent to buy fair trade products. Int J Con Stud 41:696–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12382

Lee C, Lim SY (2020) Impact of environmental concern on Image of Internal GSCM practices and consumer purchasing behavior. J Asian Finance Econ Bus 7:241–254. https://doi.org/10.13106/JAFEB.2020.VOL7.NO6.241

Lee H, Jin Y, Shin H (2018) Cosmopolitanism and ethical consumption: an extended theory of planned behaviour and modeling for fair trade coffee consumers in South Korea. Sustain Dev 26:822–834. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1851

Lee MY, Jackson V, Miller-Spillman KA et al. (2015) Female consumers׳ intention to be involved in fair-trade product consumption in the U.S. the role of previous experience, product features, and perceived benefits. J Retailing Con Serv 23:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.12.001

Liu Y, Liu MT, Perez A, Chan W, Collado J, Mo Z (2021) The importance of knowledge and trust for ethical fashion consumption. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 33(5):1175–1194. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-02-2020-0081

Merlin LA, Freeman K, Renne J, Hoermann S (2022) Clustered randomized controlled trial protocol of a Mobility-as-a-Service app for College campuses. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect 14:100572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100572

Mohd Suki NM (2016) Consumer environmental concern and green product purchase in Malaysia: structural effects of consumption values. J Clean Prod 132:204–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.087

Newton JD, Tsarenko Y, Ferraro C et al. (2015) Environmental concern and environmental purchase intentions: the mediating role of learning strategy. J Bus Res 68:1974–1981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.007

Nicholls A, Opal C (2005) Fair trade: market-driven ethical consumption Sage, London

O’Connor EL, Sims L, White KM (2017) Ethical food choices: examining people’s fair trade purchasing decisions. Food Qual Prefer 60:105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.04.001

Oh JC, Yoon SJ (2014) Theory‐based approach to factors affecting ethical consumption. Int J Consum Stud 38:278–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12092

Park KC (2018) Understanding ethical consumers: willingness-to-pay by moral cause. J Con Mark 35:157–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2017-2103

Quoquab F, Mohammad J, Sukari NN (2019) A multiple-item scale for measuring “sustainable consumption behaviour” construct: development and psychometric evaluation. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 31:791–816. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-02-2018-0047

Ran W, Zhang L (2023) Bridging the intention-behavior gap in mobile phone recycling in China: the effect of consumers’ price sensitivity and proactive personality. Environ Dev Sustain 25(1):938–959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-02085-6

Robichaud Z, Yu H (2022) Do young consumers care about ethical consumption? Modelling Gen Z’s purchase intention towards fair trade coffee. Br Food J 124:2740–2760. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2021-0536

Sadiq M, Paul J, Bharti K (2020) Dispositional traits and organic food consumption. J Clean Prod 266:121961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121961

Schäufele I, Hamm U (2018) Organic wine purchase behavior in Germany: exploring the attitude-behaviour-gap with data from a household panel. Food Qual Prefer 63:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.07.010

Shurvell J (2022) Top 6 fair trade brands tried and tested for international coffee day. Forbes, October 1. https://www.forbes.com/sites/joanneshurvell/2022/10/01/top-6-fair-trade-brands-tried-and-tested-for-international-coffee-day/?sh=12ce6916289c (Accessed 20 Jun 2022)

Sreen N, Dhir A, Talwar S et al. (2021) Behavioural reasoning perspectives to brand love toward natural products: moderating role of environmental concern and household size. J Retailing Con Serv 61:102549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102549

Stringer T, Mortimer G, Payne AR (2020) Do ethical concerns and personal values influence the purchase intention of fast-fashion clothing? J Fashion Mark Manag 24:99–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-01-2019-0011

Sultan P, Tarafder T, Pearson D, Henryks J (2020) Intention-behavior gap and perceived behavioral control-behavior gap in theory of planned behavior: moderating roles of communication, satisfaction and trust in organic food consumption. Food Qual Prefer 81:103838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103838

Sun W (2020) Toward a theory of ethical consumer intention formation: re-extending the theory of planned behavior. AMS Rev 10(3–4):260–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-019-00156-6

Taghipour HR, Naseri MH, Safiarian R, Dadjoo Y, Pishgoo B, Mohebbi HA, Besheli LD, Malekzadeh M, Kabir A (2011) Quality of life one year after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Iran Red Crescent Med J 13(3):171–177

Testa F, Pretner G, Iovino R, Bianchi G, Tessitore S, Iraldo F (2021) Drivers to green consumption: a systematic review. Environ Dev Sustain 23:4826–4880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00844-5

Todd-Blick A, Spurlock CA, Jin L, Cappers P, Borgeson S, Fredman D, Zuboy J (2020) Winners are not keepers: characterizing household engagement, gains, and energy patterns in demand response using machine learning in the United States. Energy Res Soc Sci 70:101595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101595

Torgerson D, Torgerson C (2008) Designing randomised trials in health, education and the social sciences: an introduction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Vicol M, Neilson J, Hartatri DFS et al. (2018) Upgrading for whom? Relationship coffee, value chain interventions and rural development in Indonesia. World Dev 110:26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.020

Wang E, An N, Geng X et al. (2021) Consumers’ willingness to pay for ethical consumption initiatives on e-commerce platforms. J Integr Agric 20:1012–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63584-5

Wiederhold W, Martinez LF (2018) Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: the attitude‐behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. Int J Consum Stud 42(4):419–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12435

Yamoah FA, Acquaye A (2019) Unravelling the attitude-behaviour gap paradox for sustainable food consumption: insight from the UK apple market. J Clean Prod 217:172–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.094

Yoon S (2020) Testing the effects of reciprocal norm and network traits on ethical consumption behavior. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 32(7):1611–1628. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-08-2017-0193

Yoon S, Park Y (2021) Does citizenship behaviour cause ethical consumption? Exploring the reciprocal locus of citizenship between customer and company. Asian J Bus Ethics 10:275–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-021-00130-1

Yue B, Sheng G, She S et al. (2020) Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behaviour in China: the role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 12:2074. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052074

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK: Conceptualization, Data Analysis and Writing; KH: Conceptualization; KK: Data Analysis; MM: Data Collection; YI: Survey Design; RI: Previous Research Survey; MK: Project Management.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Meiji University does not require an ethical review for research that does not target data on a part of the human body, such as blood or cells, or information on an individual’s sensitive thoughts or mental and physical conditions.

Informed consent

All study participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kato, T., Hayami, K., Kasahara, K. et al. Environmental vs. labor issues: evidence of influence on intention to purchase ethical coffee in Japan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 714 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02229-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02229-1