Abstract

Thermalization in quantum many-body systems typically unfolds over timescales governed by intrinsic relaxation mechanisms. Yet, its spatial aspect is less understood. We investigate this phenomenon in the nonequilibrium steady state (NESS) of a Bose-Hubbard chain subject to coherent driving and dissipation at its boundaries, a setup inspired by current designs in circuit quantum electrodynamics. The dynamical fingerprints of chaos in this NESS are probed using semiclassical out-of-time-order correlators within the truncated Wigner approximation. At intermediate drive strengths, we uncover a two-stage thermalization along the spatial dimension: phase coherence is rapidly lost near the drive, while amplitude relaxation occurs over much longer distances. This separation of scales gives rise to an extended hydrodynamic regime exhibiting anomalous temperature profiles, which we designate as a “prethermal” domain. At stronger drives, the system enters a nonthermal, non-chaotic finite-momentum condensate characterized by sub-Poissonian photon statistics and a spatially modulated phase profile, whose stability is undermined by quantum fluctuations. We explore the conditions underlying this protracted thermalization in space and argue that similar mechanisms are likely to emerge in a broad class of extended driven-dissipative systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chaos and thermalization are ubiquitous features in classical and quantum many-body systems. Classical chaotic dynamics are well understood in terms of Lyapunov instability: two initially nearby trajectories in phase space diverge exponentially in time1. In quantum mechanics, however, the notion of phase-space trajectory is lost, and the characterization of chaos becomes more subtle. Quantum chaotic dynamics are typically diagnosed through the statistical properties of the energy spectrum2 as well as through the temporal behavior of out-of-time-ordered correlation functions3. With the recent advances of quantum computing platforms, especially within circuit quantum electrodynamics (QED), the study of chaos in quantum devices has gained significant relevance4,5,6,7,8,9. State-of-the art driven-dissipative circuit QED architectures are nowadays able to control tens of coupled nonlinear oscillators, enabling the experimental realization of atom-photon bound states10,11,12, two-dimensional Bose-Hubbard lattices13, quantum chaotic and thermalized models14,15,16 and concatenated bosonic qubits17. In the ongoing effort to fabricate and operate increasingly complex systems—featuring a growing number of individual degrees of freedom and enhanced nonlinearities, chaotic dynamics and thermalization are both an opportunity for quantum simulations and a threat for the coherent manipulation of quantum information.

Large, isolated and nonintegrable many-body systems are generically expected to thermalize at sufficiently long times. Classically, the microscopic understanding of thermalization is addressed by Boltzmann’s H-theorem, which relies on the assumption of molecular chaos18,19. Quantum mechanically, the eigenstate thermalization hypothesis provides a theoretical framework to explain how closed Hamiltonian systems can achieve thermalization under unitary dynamics2,20,21,22,23. Typically, thermalization occurs in two stages. First, non-conserved quantities rapidly relax to local equilibrium values. Then, the hydrodynamic modes—long-wavelength excitations associated with conserved quantities such as energy or particle density—relax through a slower, often diffusive, process. This prolonged transient before complete thermalization is particularly pronounced in the proximity of integrability, where it has sometimes been dubbed prethermal regime. This is the case when an integrability-breaking perturbation is turned on suddenly24,25,26 or in a periodic fashion27,28,29,30,31. The system initially relaxes to a quasi-equilibrium state32,33, and subsequently converges to a true thermal state on an exceedingly long timescale34.

Quantum devices are inherently prone to intrinsic losses as well as extrinsic dissipation channels introduced by measurement, and their open, nonequilibrium nature poses significant conceptual challenges. While dissipative quantum chaos has gained considerable attention35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, thermalization in chaotic dissipative systems remains only partially explored. In this work, we investigate the route to thermalization in driven-dissipative chains of nonlinear bosonic modes, where photons are coherently injected at one end of the chain, and the coupling to the input and output channels induces incoherent photon losses at both ends of the chain. This is a prototypical and versatile model for quantum hardware based on superconducting circuits, within reach of current experimental setups43,44,45. Similar chains have been realized in other quantum architectures, including trapped ions46, semiconductor micropillars47, and ultracold gases in optical lattices48.

At the classical level, i.e., neglecting the quantum fluctuations, recent studies of boundary-driven dissipative Klein-Gordon chains have revealed a rich phenomenology, including unconventional transport behaviors49,50,51, which are absent in their isolated counterparts52. As the drive strength is increased, three distinct nonequilibrium steady-state (NESS) regimes have been identified: First, a quasi-linear regime in which nonlinearities are essentially irrelevant, the dynamics remain regular, and transport is ballistic. Second, a hydrodynamic regime characterized by local thermal equilibria and superdiffusive transport. At even stronger drives, this regime gives way to a resonant nonlinear wave (RNW) regime, characterized by a spatially periodic phase profile and ballistic transport. The RNW regime has been shown to remain stable under weak but finite thermal fluctuations induced by the environments at the two boundaries of the chain.

In this article, we explore the structure of the quantum many-body NESS and we investigate how quantum fluctuations impact this rich dynamical landscape. We leverage the fact that these systems are experimentally operated in regimes well described by semiclassical approaches to promote well-established concepts and tools from classical chaos theory to analyze the ergodic properties of the nonequilibrium steady state (NESS) of the open quantum chain. Specifically, we use the truncated Wigner approximation (TWA) and out-of-time-order correlators (OTOCs) to follow the transition from regular to chaotic regimes beyond the classical descriptions of Refs. 49,50,51. In the chaotic regime, we spatially resolve the transition from the strongly nonequilibrium state near the coherent drive to the low-temperature state expected at the opposite end of the chain. Between these extremes, we identify an extended phase, referred to as the prethermal phase, in which the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry, initially broken by the boundary drive, is restored, and the chain locally equilibrates to high-density states. This phase exhibits anomalous heating: the temperature increases with the distance from the boundary where energy is injected, resulting in a temperature gradient that opposes both the photon and energy currents. We attribute this phenomenon to a significant mismatch between the short relaxation scale of the phase degree of freedom and the longer hydrodynamic relaxation of the amplitude sector of the photonic field. Away from the hydrodynamic regime, we find that quantum effects significantly impact the RNW regime. In particular, quantum fluctuations demote the long-range coherence of the phase modulation and can even destabilize the RNW regime in sufficiently long chains. Our findings are directly relevant to current experimental platforms, and we propose diagnostics based on routinely measured quantities, which can be determined through quantum-state tomography via, e.g., heterodyne detection.

Results

Boundary-driven dissipative Bose-Hubbard chain

We consider a one-dimensional chain of L single-mode photonic resonators with nearest-neighbor coupling, modeled by the Bose-Hubbard model. The leftmost resonator of the chain is driven by a continuous wave drive, and the resonators at both ends of the chain experience single-photon losses, as depicted in Fig. 1. The intrinsic losses of the resonators within the bulk of the chain are assumed to be negligible. The dynamics are modeled by a Lindblad master equation for the system’s density matrix \(\hat{\rho}(t)\) reading (we set ℏ = 1).

The system Hamiltonian is expressed in the frame rotating at the drive frequency ωd as

Here, \({\hat{a}}_{\ell }^{{{\dagger}} }\) (\({\hat{a}}_{\ell }\)) are the bosonic creation (annihilation) operators for the photons in the ℓ-th resonator mode of frequency ω0. Δ ≔ ωd − ω0 is the pump-to-resonator detuning, J is the hopping amplitude between neighboring resonators, and U is the strength of the onsite Kerr nonlinearity. Our model is motivated by state-of-the-art experimental cavity or circuit QED setups43,44,45 with a weak but finite interaction, ∣U∣ ≪ ∣Δ∣, ∣J∣. While U = 0 makes the model trivially integrable, a finite U ensures the non-integrability of the Bose-Hubbard Hamiltonian on sizable chains53. Unlike in the classical Klein-Gordon chains studied in Refs. 50,51, the Kerr nonlinearity features a \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry associated with photon number conservation in the bulk of the chain. F is the amplitude of the driving field, which explicitly breaks this symmetry at one end of the chain. We take U > 0, Δ > 0, J > 0, and F≥0 (U < 0, Δ < 0, J < 0, and F≤0 yields identical results). The Lindblad dissipators at sites ℓ = 1 and ℓ = L are defined as

where \({\hat{L}}_{\ell }=\sqrt{\gamma }{\hat{a}}_{\ell }\) are the local jump operators modeling incoherent one-photon losses to the zero-temperature environment at a rate γ > 0. When not driven and isolated, i.e., F = γ = 0, the Bose-Hubbard chain is far from the Mott insulating regime, and it is naturally expected to thermalize (see, e.g., Refs. 54, 55). In the presence of drive and dissipation, it is expected to reach a unique NESS, \({\lim }_{t\to \infty }\hat{\rho}(t)\), carrying uniform DC currents of photons and energy flowing from the left drive to the right drain. As initial conditions for Eq. (1), we simply choose the vacuum state, \(\hat{\rho }(0){ = \bigotimes }_{\ell = 1}^{L}{\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{\ell }{\left\langle 0\right\vert }_{\ell }\), where \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }_{\ell }\) denotes the Fock state with zero excitation in the ℓ-th resonator. We take γ as the unit of energy and set Δ = 2.5, J = 2, and U = 0.1 for the remainder of this study.

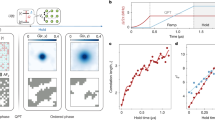

a Tight-binding array of L nonlinear resonators described by the Hamiltonian in Eq. (2) subject to a drive of amplitude F coherently injecting photons at the leftmost site and to single-photon losses with rate γ at both ends of the chain. The interplay of interaction, drive, and dissipation leads to a nonequilibrium steady state (NESS). b Lyapunov growth between neighboring Wigner trajectories is used to identify chaotic dynamics. c In the chaotic regime, the chain hosts three distinct domains illustrated by their steady-state local Wigner functions Wℓ(α, α*): a nonsymmetric nonthermal domain near the left boundary, an extensive prethermal phase where the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry of the phase is restored and which hosts a high density of photons only saturated by the Kerr nonlinearity, and a \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\)-symmetric thermal domain near the right boundary which is characterized by fluctuations over the vacuum state.

To access the NESS of Eq. (1), we use the truncated Wigner approximation (TWA), an approach based on a semiclassical treatment of the bosonic fields that accounts for leading-order quantum fluctuations56,57. In the TWA, Eq. (1) is mapped to a set of L coupled stochastic differential equations for the complex field amplitudes αℓ, reading

where f(α) ≔ Δ α − U (∣α∣2 − 1)α, ξ1 and ξL are complex Gaussian white noises such that 〈ξ1(t)〉 = 〈ξL(t)〉 = 0 and \(\langle {\xi }_{1}(t){\xi }_{1}^{* }({t}^{{\prime} })\rangle =\langle {\xi }_{L}(t){\xi }_{L}^{* }({t}^{{\prime} })\rangle =\delta (t-{t}^{{\prime} })\). In the absence of drive and dissipation, i.e., F = γ = 0, this set of equations corresponds to a discrete version of nonlinear Schrödinger equations58,59,60,61,62. Quantum mechanical effects are encoded both in the vacuum initial conditions αℓ(0) for ℓ = 1, …, L drawn from a complex Gaussian distribution with zero mean and variance 1/2, and in the stochastic coupling to the baths. The limiting equations in the classical regime are discussed in the Supplementary Note 1. A solution of Eqs. (4) is called a Wigner trajectory. Individual Wigner trajectories capture the stochastic nature of the interactions between the quantum system and its environment. In this framework, observables are calculated by sampling the Wigner trajectories over many realizations of the quantum noise. The quantum state at site ℓ can be conveniently visualized using the local Wigner function Wℓ(t; α, α*) which can be reconstructed from the statistical distribution of αℓ(t) in the complex ℜ(αℓ) − ℑ(αℓ) plane (see Methods).

Although the TWA is exact only for quadratic models (U = 0), it has been successfully applied to describe dissipative phase transitions, disordered systems, time crystals, and quantum chaos in a variety of weakly nonlinear driven-dissipative systems63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70. We justify the use of the TWA in our model by the weakness of the Kerr nonlinearity—a condition easily achievable in current circuit QED architectures71; under this condition, the TWA faithfully describes the NESS of single or multiple nonlinear driven resonators66 and boundary-driven dimers69. We further validate this approach by benchmarking it against exact results for small system sizes and comparing it with other approximation schemes (see the Supplementary Note 2). The choice of the TWA is motivated by the considerable reduction of the computational complexity it offers: the exponential growth of the Hilbert space in Eq. (1) is reduced to a linear growth in the number of stochastic equations (4), thus enabling direct numerical integration of long chains of resonators up to times past the transient dynamics and deep in the steady-state regime. Furthermore, Wigner trajectories extend the classical notion of phase-space trajectories to the quantum regime, thereby offering a practical means of investigating the exponential sensitivity to initial conditions (or lack thereof), which is a constitutive hallmark of chaotic dynamics1. Notably, while the density matrix and local Wigner functions remain constant in the NESS, individual Wigner trajectories keep fluctuating and can thus be used to analyze the integrable versus chaotic character of the dynamics in the NESS38,42.

Dynamical regimes in the NESS

We begin by investigating the NESS phase diagram as a function of the drive amplitude F and the chain length L. Unless specified otherwise, all expectation values reported below are computed in the NESS. To characterize the different steady-state regimes, we extract observables at the last site of the chain. We monitor two standard quantities in quantum optics that can easily be probed within the TWA framework: the steady-state photon number \({n}_{\ell }:= \langle {\hat{a}}_{\ell }^{{{\dagger}} }{\hat{a}}_{\ell }\rangle\) and the variance of its fluctuations \({(\Delta {n}_{\ell })}^{2}:= \langle {({\hat{a}}_{\ell }^{{{\dagger}} }{\hat{a}}_{\ell })}^{2}\rangle -{\langle {\hat{a}}_{\ell }^{{{\dagger}} }{\hat{a}}_{\ell }\rangle }^{2}\) by means of the quantity

which quantifies the relative distance to Poissonian statistics (compared to the conventional indicator g(2), δnℓ defined in Eq. (5) is less prone to numerical errors caused by a finite sampling of Wigner trajectories.). 〈…〉 indicates the average over Wigner trajectories once the NESS is reached. δnℓ = 0 corresponds to Poissonian statistics typical of coherent states, δnℓ > 0 corresponds to super-Poissonian statistics, and sub-Poissonian statistics with δnℓ < 0 are incompatible with a classical description of the state72. The quantity δnℓ is directly related to the second-order coherence function \({g}_{\ell }^{(2)}\), a standard observable in quantum optics, via \(\delta {n}_{\ell }={n}_{\ell }^{2}({g}_{\ell }^{(2)}-1)\).

In addition to the above static diagnostics, we probe the chaotic character of the dynamics, or lack thereof, by means of an out-of-time correlator (OTOC) in the NESS. OTOCs are commonly used as a diagnostic of the spatiotemporal spread of chaos in both quantum mechanical and classical systems. We focus on the OTOC between the number and the phase degrees of freedom of the resonators. In the Methods, we show that the semiclassical formulation of this phase OTOC reads61,73,74,75,76,77,78

Here, \({\varphi }_{\ell }(t):= \arg [{\alpha }_{\ell }(t)]\) is the phase of the complex field in the ℓ-th resonator along an individual Wigner trajectory. The superscripts (a) and (b) refer to two replicas of the system which are identical until time t, at which an infinitesimal perturbation is applied to the resonator at site k in replica b according to \({\varphi }_{k}^{(b)}(t)={\varphi }_{k}^{(a)}(t)+\varepsilon\), with ε ≪ 1. The subsequent evolution is computed using the same quantum noise realization for the two replicas. We stress that in Eq. (6), the replica (b) is the one perturbed at site k and, therefore, \({\varphi }_{\ell }^{(b)}\) implicitly depends on the k index.

Both the initial growth and the late regimes of Dk,ℓ(τ) shed light on the chaotic versus regular nature of the dynamics in the NESS. In chaotic dynamics, the typical distance between two trajectories with nearly identical initial conditions is expected to grow exponentially – a hallmark of Lyapunov instability, which is often taken as a defining feature of classical chaos. Quantum mechanically, this exponential growth is expected to be captured by OTOCs in systems that have a well-defined semiclassical limit or large-N limit. Dk,ℓ(τ → ∞) ≪ 1 corresponds to situations where the phases in replica a and b remain strongly correlated, suggestive of regular dynamics. In contrast, in chaotic regimes where the trajectories decorrelate rapidly, φ(a) and φ(b) can be seen as uniformly distributed random phases, resulting in a saturation value at its ergodic bound Dk,ℓ(τ → ∞) ≈ 1. We refer the Reader to the Methods section for additional details on the OTOC’s dynamics. Here, we use the saturation value of the steady-state phase OTOC, D1,ℓ(τ → ∞), as a proxy to map the chaotic versus regular character of the nonequilibrium steady-state dynamics as the drive strength F and the chain length L are varied. We notice that, while nℓ and δnℓ (or \({g}_{\ell }^{(2)}\)) can be monitored in the laboratory, accessing the behavior of Dkℓ may be more difficult, as it requires an accurate cloning of the time evolution.

Focusing on the last site, ℓ = L, the results are collected in Fig. 2. Qualitatively similar results are obtained throughout the chain, and we refer the reader to the Supplementary Note 3 for results at ℓ = 1 and ℓ = L/2. We identify three distinct regimes:

-

(I)

Regular quasilinear regime; at weak drive, only a few photons populate the last site. The photon statistics are Poissonian (δnL ≈ 0) and the small saturation value of the phase OTOC, D1,L(τ → ∞) ≈ 10−2 − 10−1, indicates regular dynamics. In this regime, single-particle excitations are dilute, rendering nonlinearities negligible and preventing the onset of chaos.

-

(II)

Chaotic regime; at stronger drives, the photon number markedly increases with respect to the quasilinear regime and nonlinearities are now relevant. The large value of δnL indicates strong super-Poissonian fluctuations, compatible with a thermal description of light. Concurrently, the phase OTOC saturates to D1,L(τ → ∞) ≈ 1, signaling significant dephasing between the fields in the two replicas. These observations, along with the exponential growth of D1, ℓ(τ) shown in the Methods section, confirm the chaotic nature of the quantum dynamics. This regime will be discussed in detail in the “Chaotic regime" subsection.

-

(III)

Resonant nonlinear wave (RNW) regime; at even stronger drives, the dynamics reach an incompressible regime where the large photon number marginally increases with F79. The small saturation value D1, L(τ → ∞) ≈ 10−2 − 10−1 indicates persistent phase correlations between the two replicas. These observations, along with the sub-exponential growth of D1, ℓ(τ) shown in the Methods section, are indicative of regular dynamics. This regime exhibits distinct quantum signatures, most notably the emergence of sub-Poissonian photon statistics, as indicated by δnL < 0. These features will be discussed in detail in the “Regular RNW regime" subsection.

Steady-state properties of the last resonator in the chain, ℓ = L, as functions of the chain length L and drive strength F. a Photon number nL. b Photon-number fluctuation δnL, defined in Eq. (5). c Saturation value of the steady-state phase OTOC, D1,L(τ → ∞), defined in Eq. (6). The three distinct regimes labeled I, II, and III are discussed in throughout the “Results" section. d–f Cuts of a–c, respectively, at fixed chain length L = 10. Results are computed by averaging over Ntraj = 103 independent Wigner trajectories. Statistics are further improved by averaging over a time window Δτ after reaching the NESS: Δτ = 25 for D1,L(τ → ∞), and Δτ = 2 × 103 for nL and δnL. Throughout the manuscript, the dissipation rate γ sets the unit of energy, and the other parameters are fixed to Δ = 2.5, J = 2, and U = 0.1.

The crossover from the regular quasilinear regime (I) to the chaotic regime (II) is smooth in both nL and δnL while the transition between the chaotic regime (II) and the RNW regime (III) is characterized by abrupt variations [see Fig. 2 (d) and (e)]. In particular, the drive strength F at which the photon number leaps coincides with that of the maximum of δnL.

Chaotic regime

Two-stage relaxation in space

In this section, we focus on the chaotic regime (II). We decompose the complex field in terms of amplitude and phase degrees of freedom, \({\alpha }_{\ell }=| {\alpha }_{\ell }| \,{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\varphi }_{\ell }}\), and separately analyze their spatial relaxation along the chain, from ℓ = 1 to ℓ = L. Figure 3 (a) and (b) shows the steady-state profile of photon density nℓ = 〈∣αℓ∣2〉 − 1/2 and the circular phase variance \(\Delta {\varphi }_{\ell }:= 1-| \langle {{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\varphi }_{\ell }}\rangle |\) across the chain. The latter quantifies the spread of the phase distribution: Δφℓ → 0 if the phase is well-defined, whereas Δφℓ → 1 for a uniformly distributed phase. The field amplitude decays slowly along the chain over a characteristic length scale ξn, which increases monotonically with both the chain length L and the drive strength F. We distinguish two regimes: for weak drives, F ≲ 6.5, the photon density relaxes just beyond the driven site; for intermediate drives, F ≳ 6.5, the density first saturates to a large value over an extended region, with its decay occurring only near the end of the chain. These large spatial scales can be explained by the local conservation of the photon number within the bulk of the chain, which hinders the rapid relaxation of the amplitude degree of freedom. Instead, this relaxation occurs through much slower hydrodynamic processes involving the driven-dissipative conditions at the two boundaries of the chain. In contrast, the phase degrees of freedom relax over a microscopic length scale ξφ, typically spanning only a few lattice sites. The saturation of the phase variance, Δφℓ → 1, signals the restoration of the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry of the underlying bulk Hamiltonian. This mechanism is illustrated in Fig. 3 (d-f), where the local Wigner functions Wℓ(α, α*) rapidly lose the anisotropy imprinted by the coherent boundary drive and become invariant under rotations in the complex plane throughout the rest of the chain. The overall change of the topology of Wℓ(α, α*), from ring shape to bell shape, will be discussed below.

Spatial profiles of equal-time photon statistics in the chaotic NESS. a Photon density nℓ = 〈∣αℓ∣2〉 − 1/2, showing a growing relaxation length scale with increasing drive strength F = 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8 (from yellow to purple), and a plateau across most of the chain at stronger drives. b Circular phase variance \(\Delta {\varphi }_{\ell }:= 1-| \langle {{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\varphi }_{\ell }}\rangle |\), which rapidly saturates to unity, indicating a uniform phase distribution. c First-order coherence function \(| {g}_{k,\ell }^{(1)}|\) defined in Eq. (7) showing exponential decay of phase correlations on microscopic length scales away from ℓ = k. d–f Normalized local Wigner functions, \({\tilde{W}}_{\ell }(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* }):= {W}_{\ell }(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* })/\max [{W}_{\ell }(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* })]\) for representative sites in a chain of length L = 400. Results are computed by averaging over Ntraj = 102 independent Wigner trajectories and over a time window Δτ = 104 once the steady state is reached. The drive strength is set to F = 7.5 in b–f, and the other parameters are set as in Fig. 2.

To corroborate the short relaxation of the phase sector, we compute the spatial correlations of the phases in the chain by means of the first-order coherence function,

The results are presented in Fig. 3(c) as a function of ℓ for a center site k = L/2. The profile of the spatial correlations shows exponential decay, \(| {g}_{k,\ell }^{(1)}| \sim {{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{-| k-\ell | /{\xi }_{\varphi }}\), typical of a disordered phase with a correlation length ξφ on the order of a few sites, before saturating to values below 10−2.

Altogether, these results point to a two-stage thermalization process in space: the phase sector relaxes to a disordered state over a short, microscopic length scale, while the amplitude sector undergoes a slower relaxation that depends on the boundary conditions and unfolds over the entire system. As we shall demonstrate below, this opens up a significant region of the chain, beyond the few sites directly influenced by the boundary drive, but before the complete relaxation to near-vacuum states subject to thermal fluctuations, where an effective \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry emerges. In this intermediate region, the highly populated sites along the chain can be interpreted as being in local equilibrium, characterized by a large and slowly varying chemical potential.

Hydrodynamic description

We test this hydrodynamic scenario by probing the local symmetries, the local thermodynamics, and the temporal fluctuations across the chain. On general grounds, the local steady-state density matrix \({\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }:= {\lim }_{t\to \infty }{{{{\rm{Tr}}}}}_{k\ne \ell }\hat{\rho }(t)\) can be cast as the solution of an effective driven-dissipative impurity model constructed by singling out one site of the chain, and tracing out its neighbors such as to treat them as incoherent sources and drains. In a generic NESS, however, the rigorous derivation of an effective driven-dissipative impurity model is a daunting task, and we simply rely on symmetries and heuristics to identify minimal impurity models that successfully locally capture both the statics as well as temporal fluctuations.

Let us first address the statics. Guided by hydrodynamic principles, we assume that, away from the boundary drive, the local steady-state density matrix \({\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }\) is close to an equilibrium \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\)-symmetric Gibbs state of the form (we set kB = 1)

where \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{\ell }\) is such that \({{{\rm{Tr}}}}\left({\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }^{{{{\rm{eq}}}}}\right)=1\), and the local Hamiltonian

corresponds to a single site of the chain Hamiltonian in Eq. (2). Tℓ and μℓ are, respectively, the effective temperature and chemical potential at site ℓ, to be determined. Note that the quadratic onsite contributions to \(\hat{H}\), namely − Δ − U/2, have been absorbed into a redefinition of μℓ.

We assess the validity of this effective description and the underlying restoration of the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry by fitting the local steady-state Wigner function Wℓ(α, α*) along the chain to those predicted by the above Gibbs ansatz. The two fitting parameters are Tℓ and μℓ. We repeat this procedure at all sites from ℓ = 1 to ℓ = L. Excellent matches are obtained at all sites except near the driven boundary, thereby confirming the rapid restoration of the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry away from the drive and validating the use of the Gibbs state as a local thermometer. In regimes where the photon density is very low, the Kerr nonlinearity is effectively inactive, and it becomes numerically challenging to extract Tℓ and μℓ independently. However, the ratio μℓ/Tℓ, which governs the shape of the Wigner function in the dilute limit, can still be determined with high accuracy.

Let us now turn to the description of the dynamical fluctuations in the steady state. We start from the local \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\)-symmetric Hamiltonian \(\hat{h}\) introduced in Eq. (9) and promote it to Lindblad dynamics by supplementing it with the first non-trivial jump operators allowed under weak \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry80,

The non-negative parameters \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\uparrow }\), \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\downarrow }\), \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\phi }\), and \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\) are effective rates of incoherent pumping, decay, dephasing, and 2-photon decay at site ℓ. The inclusion of the latter is essential to ensure the saturation of the photon number when \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\uparrow } > {\gamma }_{\ell }^{\downarrow }\). Equations (9) and (10) define a driven-dissipative impurity ansatz that supports a NESS. The parameters \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\uparrow }\), \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\downarrow }\) and \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\) are determined by fitting the local Wigner functions Wℓ(α, α*) to those predicted by the impurity ansatz. The latter are independent of the dephasing rate \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\phi }\) that can be extracted by fitting two-time correlation functions. The overall fitting procedure is detailed in the Supplementary Note 6. Excellent matches are obtained everywhere away from the boundary drive.

Although this impurity ansatz does not rely on assuming local equilibria, we have verified that both the previous Gibbs ansatz and this impurity ansatz consistently capture and reproduce the same static properties when related through the detailed-balance condition

We stress that the above steady-state impurity modeling is not unique. In particular, we also tested a generalized version of the Scully-Lamb model81,82 defined by \({\hat{L}}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}=0\) and a modified \({\hat{L}}_{\uparrow }={\hat{a}}^{{{\dagger}} }({\gamma }^{\uparrow }-{{{\mathcal{S}}}}\,\hat{a}{\hat{a}}^{{{\dagger}} })/\sqrt{{\gamma }^{\uparrow }}\), where \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\ge 0\) is a photon saturation rate. In the context of lasing, this model can be derived as an effective theory for the optical degree of freedom when the (inverted) atomic population modeled by two-level systems has been integrated out83,84. This ansatz proved to be equally successful in capturing both the statics and the dynamical fluctuations yielding, comparable values of the effective parameters \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\uparrow }\) and \({\gamma }_{\ell }^{\downarrow }\).

A detailed comparison between these three thermometers, and temperature computed from the equipartition theorem whenever the latter is applicable, can be found in the Supplementary Notes 5, 6 and 7. As reported in Fig. 4 (d), we obtained an excellent agreement between these multiple approaches.

Spatial profile of the local (a) effective temperature Tℓ, b effective chemical potential μℓ, and c entropy density \({S}_{\ell }:= -{{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }\log {\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }]\) across a chain of length L = 400. The results are obtained by mapping the local steady-state physics at site ℓ to the Gibbs ansatz defined in Eq. (8). d Spatial profile of the dimensionless ratio μℓ/Tℓ for the same system. The results are obtained by mapping the local physics at site ℓ to the Gibbs ansatz, to the 2-photon impurity ansatz defined in Eqs. (9) and (10), and to the generalized Scully-Lamb ansatz. Three distinct spatial domains are discussed in the text: 1) nonsymmetric nonthermal domain where all the ansätze fail; 2) prethermal domain where μℓ/Tℓ > 0; 3) thermal domain with μℓ/Tℓ≤0. e Respective sizes of the three domains versus the total chain length L. The dashed lines are guides for the eye. The drive strength is set to F = 7.5 and the other parameters are set as in Fig. 2.

Nonthermal, prethermal, and thermal domains

The above generalized thermometers provide the spatial profiles of the local temperature and chemical potential, Tℓ and μℓ, respectively, which we use to analyze the thermodynamics along the chain, see Fig. 4(a) and (b). In Fig. 4(c), we present the dimensionless ratio Tℓ/μℓ. As a complementary observable, we also monitor the entropy density \({S}_{\ell }:= -{{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }\log {\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }]\), see Fig. 4(c), that can be computed independently, i.e. without relying on the thermodynamic ansätze.

Depending on the strength of the drive, we distinguish two regimes. At relatively weak drives (F ≲ 6.5), μℓ remains negative throughout the chain and Sℓ monotonously decreases along the chain. This is consistent with the monotonously decaying photon density profiles shown in Fig. 3(a): negative chemical potentials lead to photon depletion toward a vacuum state dressed by thermal fluctuations. At intermediate drives (F ≳ 6.5), μℓ becomes positive and approximately constant across most of the chain, before dropping abruptly to negative values near the non-driven right boundary. This correlates with the photon density profiles shown in Fig. 3(a): large positive chemical potentials sustain a significant photon population limited only by the Kerr nonlinearity. Concurrently, Tℓ increases across most of the chain, reaching very high values before dropping sharply near the right end. Although the low temperatures observed at both boundaries are consistent with the proximity of the zero-temperature dissipative baths, the magnitude and position of the temperature maximum may at first seem to challenge the Clausius principle. This anomalous profile is corroborated by the entropy density profile, Sℓ, which exhibits an accumulation of entropy precisely where Tℓ attains its peak. This counterintuitive behavior motivates our designation of this anomalous regime as “prethermal”. Similar anomalous heating profiles have previously been reported in the context of the discrete nonlinear Schrödinger equation subjected to incoherent thermal reservoirs at the two ends of a one-dimensional chain58. This effect has been attributed to the coupling between heat and particle transport. Specifically, it arises from the coexistence of two conserved quantities in the bulk, photon number and energy, whose associated Noether currents, jn and jϵ, are coupled at the level of linear response theory.

Altogether, we identify three distinct spatial domains in the chaotic chain, from the left to the right:

-

1.

Nonsymmetric nonthermal domain; The first few sites are not captured by the different hydrodynamic ansätze because of the proximity to the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\)-breaking drive. This breaking of \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry is visible in the asymmetry of local Wigner functions represented in Fig. 3 (d). Here, the quantities Tℓ and μℓ are ill-defined, as indicated by the hatched region in the figure.

-

2.

\({\mathbb{U}}(1)\)-symmetric prethermal domain; In this intermediate region of the chain, only realized under strong enough driving, local quantities are well captured by hydrodynamics with a positive effective chemical potential, μℓ > 0, and a finite 2-photon decay rate γs. The relatively constant number of photons reported in Fig. 3 (a), along with the large ring-shaped Wigner functions in Fig. 3 (e), can be interpreted as the result of the competition between a large chemical potential that strives to add photons and the Kerr non-linearity that acts as a saturation mechanism. This state should not be interpreted as lasing: unlike standard lasers, the temporal phase coherence here is short-lived, and the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry remains unbroken (see Supplementary Note 6). Instead, the phase undergoes diffusive dynamics85, which restores the symmetry of the chain Hamiltonian. From a thermodynamic perspective, this domain exhibits anomalous heating, characterized by temperature Tℓ and entropy Sℓ that increase with distance from the coherent drive. This originates from the fact that the energy current is predominantly transported by a flux of photons with large chemical potential, rather than through conventional heat flow.

-

3.

\({\mathbb{U}}(1)\)-symmetric thermal domain; The right side of the chain is captured by the impurity ansatz with a negative chemical potential, μℓ≤0. The corresponding Wigner functions, illustrated in Fig. 3 (f), display bell-shaped envelopes that can be interpreted as the outcome of a competition between the chemical potential depleting the photon population towards the vacuum, and the thermal fluctuations that sustain a residual population of weakly-interacting photons. Thermodynamically, the energy current is now mostly driven by the strong thermal gradient that has built up in this region of the chain.

We argue in Fig. 4 (e) that the sizes of the non-symmetric and thermal domains are limited to the subdominant portions of the chain, while the size of the prethermal domain increases linearly with the total length of the chain L. This suggests that the latter may be an extensive thermodynamic phase that occurs ahead of the complete thermalization at the rightmost portion of the chain.

Regular RNW regime

In this Section, we focus on the RNW regime that was first observed in Ref. 50 in the context of driven-dissipative Klein-Gordon chains coupled to zero-temperature boundary baths, and further studied in Ref. 51. We discuss how the presence of quantum fluctuations modifies the classical picture.

Performing a quench from the vacuum and evolving under strong coherent drive, the dynamics exhibit two successive temporal regimes, illustrated in Fig. 5 in terms of the average phase 〈φℓ〉 and photon density nℓ. Initially, the system undergoes a prolonged transient during which φℓ is uniformly distributed, rendering 〈φℓ〉 ill-defined away from the boundary drive. In this stage, nℓ gradually builds up along the chain, starting from the driven boundary site and progressively reaching large values throughout the entire system. This transient corresponds to the chaotic regime discussed in the previous section. It is followed at late times by the onset of the RNW steady state, where φℓ acquires a finite expectation value that slowly rotates along the chain. The dominant wavelength of these oscillations, approximately 30 sites here, as well as the large and uniform photon density, are expected to be dynamically set and independent of the total chain length L51. As we show in the Supplementary Note 8, both 〈φℓ〉 and nℓ in the RNW steady state closely match their classical counterparts, indicating that these observables do not capture distinct quantum features of the RNW regime. The onset of the RNW steady state is governed by a characteristic timescale tss that will be discussed below.

Spatiotemporal evolution of a the photon density nℓ, and b the average phase 〈φℓ〉 as functions of time t and site index ℓ in a L = 100 chain in the RNW regime. The hatched region in b indicates the transient chaotic regime in which the \({\mathbb{U}}(1)\) symmetry is restored and the average phase becomes ill-defined. Results are obtained upon averaging over Ntraj = 5 × 103 independent Wigner trajectories. The drive amplitude is fixed to F = 12.5. The other parameters are set as in Fig. 2.

Quantum signatures in the steady state

Let us now characterize the distinct quantum signatures of the RNW regime once it is established. In Fig. 6(a), we monitor the phase fluctuations by means of the circular variance \(\Delta {\varphi }_{\ell }:= 1-| \langle {{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\varphi }_{\ell }}\rangle |\) as a function of the site index ℓ. In contrast to the driven-dissipative Klein-Gordon chain with zero-temperature boundary baths, where phase fluctuations are absent50,51, we find that Δφℓ increases monotonically along the chain. This behavior is further illustrated in Fig. 6(b–e) through the Wigner functions \({W}_{\ell }\left(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* }\right)\) at four representative sites in the bulk of the chain; (b) ℓ = 5, (c) ℓ = 25, (d) ℓ = 50, (e) ℓ = 95. The amplitude degree of freedom remains effectively frozen, while the phase undergoes diffusion. As a result, \({W}_{\ell }\left(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* }\right)\) is concentrated along an arc in phase space, with its angular extent gradually broadening along the chain. The suppressed fluctuations in the radial direction underpin the sub-Poissonian photon statistics characteristic of the RNW regime.

a Phase fluctuations along the chain, quantified by the circular variance \(\Delta {\varphi }_{\ell }:= 1-| \langle {{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\varphi }_{\ell }}\rangle |\), plotted as a function of site index ℓ for a chain of length L = 100 in the RNW regime. The solid blue line corresponds to the TWA results, while the dashed black line shows the classical Gross-Pitaevskii solution. b–e Local Wigner functions Wℓ(α, α*) at representative sites throughout the chain. We show the normalized distribution \(\tilde{W}(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* }):= {W}_{\ell }(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* })/\max [{W}_{\ell }(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{* })]\). Yellow markers denote the classical Gross-Pitaevskii solutions. f Same as in a, but for the first-order coherence function \(| {g}_{k\ell }^{(1)}|\) with k = 1. Results are computed by averaging over Ntraj = 5 × 103 independent Wigner trajectories and over a time window Δτ = 103 once the steady state is reached. The drive amplitude is fixed to F = 12.5. The other parameters are set as in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 6 (f), the phase coherence \(| {g}_{1,\ell }^{(1)}|\) exhibits long-range correlations extending across the entire chain. However, contrary to the classical prediction of a uniform \(| {g}_{1,\ell }^{(1)}|\), we observe a slow spatial decay of phase coherence along the chain. This decay arises from quantum fluctuations, which demote the true long-range order predicted in the classical limit. Determining the precise functional form of this decay is challenging due to numerical limitations on accessible system sizes, and because large systems tend to lose the RNW regime, as we discuss below. We also demonstrate that the RNW regime is stable against the presence of weak but finite intrinsic photon losses at all sites, up to decay rates γint = 10−3. For larger values of γint, the RNW first collapses into the chaotic regime and ultimately collapses to a collection of local vacuum states.

Metastability and transition to chaos

We found compelling numerical evidence that the RNW steady state does not persist in the thermodynamic limit in the presence of quantum fluctuations. Following a quench from the vacuum under strong coherent drive, we observe that the emergence of the RNW steady state is governed by a characteristic timescale tss which increases exponentially with the system size L. Moreover, even when evolving the dynamics beyond tss, the system fails to reach the RNW steady state for chains larger than a critical length L > L*, instead remaining confined to the chaotic regime described in the previous section.

This is illustrated in Fig. 7 (a), where the photon density at the end of the chain, nL(t), is monitored for various L. While nL(t) converges to its RNW value for chains of length L ≤ 200, it saturates to system-size-dependent values consistent with the chaotic regime for L ≳ 200. To highlight the quantum origin of this dynamical phenomenon, we compare with the classical case: the convergence to the RNW steady state is restored when setting the quantum fluctuations to zero in Eqs. (4). Moreover, the classical solution exhibits transient chaos before approaching the regular RNW steady state.

a Transient dynamics of the photon number at the last site of the chain, nL(t), plotted as a function of time t for system sizes L = 100, 200, and 400. The gray line is the classical Gross-Pitaevskii solution for L = 400. b Characteristic timescale tss to reach the RNW steady state as a function of system size L, for three different drive strengths. Each data series is truncated once the RNW regime fails to emerge within the accessible simulation time. The black dashed line is an exponential fit to the data for F = 12.5. c Evidence of metastability near the transition between the RNW and chaotic regimes. The photon number at the last site, \({n}_{L}({t}_{\max }\simeq 1{0}^{5})\), is computed from Ntraj = 200 Wigner trajectories and time-averaged over a window Δt = 103. The resulting histogram is shown for L = 200, 300, and 400. In a and c, the drive amplitude is fixed at F = 12.5. The other parameters are set as in Fig. 2.

Within the quantum picture, the size L* at which the breakdown of the RNW regime occurs decreases with increasing drive strength F, ruling out a reentrant chaotic phase in the NESS phase diagram as a function of L. In Fig. 7(b), we demonstrate the exponential scaling of tss that is operationally defined via the convergence criterion \(| {n}_{L}(t > {t}_{{{{\rm{ss}}}}})-{n}_{L}({t}_{\max })| < \varepsilon\), with ε = 0.01, whenever the RNW regime has been reached at the final time \({t}_{\max }\).

We attribute this phenomenon to the emergence of metastability: in the absence of fluctuations, multiple stationary states coexist, namely the chaotic and the RNW steady states39,51. The addition of quantum fluctuations allow trajectories to stochastically transition between these, and the RNW regime becomes metastable for L > L*. To probe this, we evolve an ensemble of Wigner trajectories from the vacuum up to a late time \({t}_{\max }\), and subsequently analyze the time-averaged photon number at the chain’s end over a window Δt. The latter is chosen to suppress high-frequency noise while preserving distinctions between chaotic and regular dynamics. Histograms of this observable, shown in Fig. 7 (c) for a fixed \({t}_{\max }=1{0}^{5}\), Δt = 103, reveal a clear dynamical crossover when increasing the system size: unimodal at L = 200 (fully RNW), bimodal at L = 300 (coexistence), and unimodal (fully chaotic) at L = 400. Notably, at L = 300, a significant fraction of the trajectories remains in the chaotic manifold although \({t}_{\max }\gg {t}_{{{{\rm{ss}}}}}\).

Discussion

The NESS of the boundary-driven dissipative chain of quantum nonlinear oscillators revealed an extensive spatial domain, where the chaotic dynamics drive the system to a hydrodynamic regime describable via local equilibria with a large, emergent chemical potential. While consistently with its hydrodynamic nature, this regime displays no distinct quantum signatures, it exhibits anomalous heating, with temperature increasing away from the coherent drive.

More broadly, the emergence of a such a prethermal chaotic phase hinges on three key ingredients: first, an interacting bulk with two conserved charges; second, a local nonequilibrium drive that explicitly breaks the associated symmetries; and finally, weakly-symmetric dissipation channels positioned far from the drive, enabling nontrivial steady states and slow hydrodynamic relaxation. Together with the semiclassical framework developed here, these elements provide a minimal blueprint for realizing prethermal chaotic phases in a broad class of boundary-driven systems.

Quantum fluctuations were found to be relevant to the RNW regime: (i) inducing phase fluctuations along the chain that degrade the long-range coherence of the finite-momentum condensate, and (ii) ultimately destabilizing the condensate in sufficiently long chains. These findings naturally raise the question of how anomalous heating in the prethermal domain and phase fluctuations in the RNW regime impact transport properties, which were reported to be superdiffusive and ballistic, respectively, in classical Klein-Gordon chains49,50,86,87,88. In particular, it is an intriguing possibility that phase fluctuations in the RNW regime might hold fingerprints of Kardar-Parisi-Zhang universality. Also, it remains an open question to assess the role of quantum fluctuations, beyond semiclassics, on both the existence of the prethermal domain and the instability of the RNW regime in the thermodynamic limit. Resolving these challenges will demand either significantly larger numerical simulations or novel approaches beyond TWA, capable of capturing intermediate Kerr nonlinearities while incorporating quantum fluctuations.

Methods

Stochastic semiclassical description

The TWA is a semiclassical approximation of the quantum many-body dynamics that accounts for leading-order quantum fluctuations. It relies on a phase-space representation of the system’s density matrix \(\hat{\rho }\) in terms of the Wigner function \(W({\alpha }_{1},{\alpha }_{1}^{* },\ldots ,{\alpha }_{L},{\alpha }_{L}^{* })\), where αℓ and \({\alpha }_{\ell }^{* }\) for ℓ = 1, …, L are the complex amplitudes associated with the local coherent states. In this framework, the Lindblad master equation on the operator \(\hat{\rho }\) in Eq. (1) is mapped to a partial differential equation on W. Two-body interactions in the Hamiltonian yield contributions up to third order derivatives of the type \({\alpha }_{\ell }\,{\partial }^{3}W/\partial {\alpha }_{\ell }^{* }{\partial }^{2}{\alpha }_{\ell }\). The approximation consists of discarding third and higher-order derivatives, reducing the dynamics to a Fokker-Planck equation where W can be interpreted as a probability distribution of the phase-space variables. The latter equation can then be unraveled into a set of L coupled stochastic differential equations on the complex amplitudes αℓ given by Eq. (4). In practice, we compute the solutions of these Langevin-like equations, the so-called Wigner trajectories, by means of numerical solvers specific to stochastic differential equations. Observables are computed by averaging over a large number of trajectories generated by different realizations of the quantum noise.

The dictionary between the original Lindblad master equation framework and the Wigner-trajectory implementation of the TWA framework is reported in Table 1, where 〈…〉 in the observable column is the standard quantum expectation value and, in the Wigner trajectories column, denotes the average with respect to Wigner trajectories. The local Wigner function Wℓ(t; α, α*) is a phase-space representation of the reduced density matrix at site ℓ, \({\hat{\rho }}_{\ell }(t):= {{{{\rm{Tr}}}}}_{k\ne \ell }\,\hat{\rho}(t)\). It can be simply reconstructed by generating the histogram of αℓ(t) in the complex plane when sampling over Wigner trajectories. When the NESS is reached, single-time observables converge to constant values and Wℓ(t; α, α*) → Wℓ(α, α*). There, the statistics can be improved by also sampling the trajectories in time, significantly reducing the computational overhead.

Semiclassical OTOC

Here we describe in detail our probe of semiclassical chaos, the semiclassical OTOC of Eq. (6). We show how Eq. (6) can be derived from the quantum formulation of the out-of-time order correlators,

The above OTOC involves a “square commutator” between site k at time t and site ℓ at a later time t + τ. The operators \({\hat{A}}_{\ell }={\hat{n}}_{\ell }:= {\sum }_{n = 0}^{\infty }n\,{\left\vert n\right\rangle }_{\ell }{\left\langle n\right\vert }_{\ell }\) and \({\hat{B}}_{\ell }={{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\hat{\varphi }}_{\ell }}:= \mathop{\sum }_{n = 0}^{\infty }{\left\vert n\right\rangle }_{\ell }{\left\langle n+1\right\vert }_{\ell }\) are chosen to decompose the local field operator into \({\hat{a}}_{\ell }=\sqrt{\hat{{n}_{\ell }}}\,{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\hat{\varphi }}_{\ell }}\). They obey the quantum commutation relation \([{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\hat{\varphi }}_{k}},{\hat{n}}_{\ell }]={\delta }_{k\ell }\,{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\hat{\varphi }}_{\ell }}\). Quantum mechanically, while the absence of a well-defined phase operator is known, the operator \({{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{\hat{\varphi }}_{\ell }}\) is well defined.

In a semiclassical approach, these operators are replaced with c-numbers, namely local number nℓ and phase φℓ, and the latter is well defined. The commutation relations are replaced with \(\left\{{n}_{k},{\varphi }_{\ell }\right\}={\delta }_{k\ell }\), where { ⋅ , ⋅ } denotes the Poisson brackets defined as

Carrying out this replacement in Eq. (12), using the relation \(\{{\varphi }_{\ell }({t}^{{\prime} }),{n}_{k}(t)\}=-\delta {\varphi }_{\ell }({t}^{{\prime} })/\delta {\varphi }_{k}(t)\), one obtains the semiclassical version of Ck,ℓ(t, τ) which reads

where 〈…〉 denote the average over the quantum noise and δ/δφk(t) implements an infinitesimal perturbation of the phase at site k and time t. In practice, this is implemented by cloning the system in two replicas a and b, applying an infinitesimal perturbation at time t on the phase at site k of replica b, subsequently evolving both replicas subject to the same quantum noise, and finally averaging over realizations of the quantum noise. Thus, the semiclassical phase OTOC can be cast as

which boils down to the operational definition given in Eq. (6).

Whenever the dynamics reaches a steady state, \(\hat{\rho }:= {\lim }_{t\to \infty }\hat{\rho}(t)\), we can define the semiclassical steady-state phase OTOC as \({D}_{k,\ell }(\tau ):= {\lim }_{t\to \infty }{D}_{k,\ell }(t,\tau )\). Throughout the paper, we focus on Dk,ℓ(τ) only.

We now show that our semiclassical OTOC is able to capture the basic features of quantum information spreading in extended many-body systems89, as well as the initial exponential growth in the presence of chaos. On general grounds, we have Dk,ℓ(τ = 0) = 0, while Dk,ℓ(τ > 0) is expected to increase with τ whenever trajectories in the two replicas start deviating, and, eventually, to saturate to a finite value Dk,ℓ(τ → ∞). Both the growth and the saturation regimes of Dk,ℓ(τ) shed light on the chaotic versus regular nature of the dynamics in the NESS. In Fig. 8 (a) we show the space-time dynamics of D1,ℓ(τ) in the chaotic regime of the boundary-driven dissipative Bose-Hubbard chain Eq. (2), for a system’s size equal to L = 80. We see how D1,ℓ(τ) exhibits a causal light-cone structure with a ballistic spreading of information characterized by a butterfly velocity v = 2J90. In Fig. 8 (b) and (c), we illustrate the growth of the steady-state semiclassical OTOC for two representative values of the drive strength F, one for the chaotic regime, one for the regular RNW regime, always for a chain with L = 80. In panel (b), D1,ℓ(τ) shows a rapid exponential growth of the form \({D}_{1,\ell }(\tau ) \sim \exp [\lambda (t-\ell /v)]\) where λ is a Lyapunov rate, followed by a saturation regime where D1,ℓ(τ → ∞) ≃ 1, i.e., maximal decorrelation. Altogether, the semiclassical OTOC D1, ℓ(τ) captures both the Lyapunov growth and the saturation regimes expected of quantum chaotic dynamics. In panel (c), D1,ℓ(τ) instead displays early-time oscillations and the overall growth is slower than exponential. Eventually, the late-time saturation value D1,ℓ(τ) is significantly less than 1. This is indicative of regular dynamics.

a Spatio-temporal scrambling of information in the NESS probed by the semiclassical OTOC D1,ℓ(τ), defined in Eq. (14) and computed via Eq. (6), across a chain of length L = 80 in the chaotic regime. The dashed line indicates ballistic spreading of information at the butterfly velocity v = 2J. b Dynamics of D1,ℓ(τ) in the chaotic regime computed at sites ℓ = 1, 10, 20, …, 80 (from dark purple to light pink) of an L = 80 chain. The exponential growth in τ at a Lyapunov rate λ ≃ 2.8 is a hallmark of chaotic dynamics. c Dynamics of D1,ℓ(τ) in the RNW regime at the same sites as in b. The sub-exponential growth in time τ signals non-chaotic dynamics. The dashed line indicates the ergodic bound on the saturation value of the semiclassical OTOC. The results are computed upon averaging over Ntraj = 5 × 103 independent Wigner trajectories. In a and b, the drive amplitude is fixed to F = 7.5, in c to F = 12.5. The other parameters are set as in Fig. 2.

Data availability

Data used to generate the plots are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

Simulation codes are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Strogatz, S. H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos, 1st ed. (CRC Press, 2018).

D’Alessio, L., Kafri, Y., Polkovnikov, A. & Rigol, M. From quantum chaos and eigenstate thermalization to statistical mechanics and thermodynamics. Adv. Phys. 65, 239 (2016).

Hashimoto, K., Murata, K. and Yoshii, R. Out-of-time-order correlators in quantum mechanics, J. High Energy Phys. 318, (2017).

Berke, C., Varvelis, E., Trebst, S., Altland, A. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Transmon platform for quantum computing challenged by chaotic fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 13, 2495 (2022).

Shillito, R. et al. Dynamics of Transmon Ionization. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 034031 (2022).

Cohen, J., Petrescu, A., Shillito, R. & Blais, A. Reminiscence of classical chaos in driven transmons. PRX Quantum 4, 020312 (2023).

Dumas, M. F. et al. Measurement-induced transmon ionization. Phys. Rev. X 14, 041023 (2024).

García-Mata, I. et al. Impact of chaos on the excited-state quantum phase transition of the Kerr parametric oscillator. Phys. Rev. A 111, L031502 (2025).

Chávez-Carlos, J. et al. Driving superconducting qubits into chaos. Quantum Sci. Technol. 10, 015039 (2025).

Liu, Y. & Houck, A. A. Quantum electrodynamics near a photonic bandgap. Nat. Phys. 13, 48 (2017).

Sundaresan, N. M., Lundgren, R., Zhu, G., Gorshkov, A. V. & Houck, A. A. Interacting qubit-photon bound states with superconducting circuits. Phys. Rev. X 9, 011021 (2019).

Scigliuzzo, M. et al. Controlling atom-photon bound states in an array of Josephson-Junction Resonators. Phys. Rev. X 12, 031036 (2022).

Karamlou, A. H. et al. Probing entanglement in a 2D hard-core Bose-Hubbard lattice. Nature 629, 561 (2024).

Braumüller, J. et al. Probing quantum information propagation with out-of-time-ordered correlators. Nat. Phys. 18, 172 (2022).

Zhang, X., Kim, E., Mark, D. K., Choi, S. & Painter, O. A superconducting quantum simulator based on a photonic-bandgap metamaterial. Science 379, 278 (2023).

Andersen, T. I. et al. Thermalization and criticality on an analogue-digital quantum simulator. Nature 638, 79 (2025).

Putterman, H. et al. Hardware-efficient quantum error correction via concatenated bosonic qubits. Nature 638, 927 (2025).

Boltzmann, L. Weitere Studien über das Wärmegleichgewicht unter Gasmolekülen. Sitzungsberichte Akademie der Wissenschaften 66, 275 (1872).

Brown, H. R., Myrvold, W. & Uffink, J. Boltzmann’s H-theorem, its discontents, and the birth of statistical mechanics. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part B: Stud. Hist. Philos. Mod. Phys. 40, 174 (2009).

Deutsch, J. M. Quantum statistical mechanics in a closed system. Phys. Rev. A 43, 2046 (1991).

Srednicki, M. Chaos and quantum thermalization. Phys. Rev. E 50, 888 (1994).

Srednicki, M. The approach to thermal equilibrium in quantized chaotic systems. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 32, 1163 (1999).

Rigol, M., Dunjko, V. & Olshanii, M. Thermalization and its mechanism for generic isolated quantum systems. Nature 452, 854 (2008).

Bertini, B., Essler, F. H., Groha, S. & Robinson, N. J. Prethermalization and Thermalization in Models with Weak Integrability Breaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 180601 (2015).

Babadi, M., Demler, E. & Knap, M. Far-from-equilibrium field theory of many-body quantum spin systems: prethermalization and relaxation of spin spiral states in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041005 (2015).

Birnkammer, S., Bastianello, A. & Knap, M. Prethermalization in one-dimensional quantum many-body systems with confinement. Nat. Commun. 13, 7663 (2022).

Abanin, D., De Roeck, W., Ho, W. W. & Huveneers, F. A rigorous theory of many-body prethermalization for periodically driven and closed quantum systems. Commun. Math. Phys. 354, 809 (2017).

Abanin, D. A., De Roeck, W., Ho, W. W. & Huveneers, F. Effective Hamiltonians, prethermalization, and slow energy absorption in periodically driven many-body systems. Phys. Rev. B 95, 014112 (2017).

Else, D. V., Bauer, B. & Nayak, C. Prethermal phases of matter protected by time-translation symmetry. Phys. Rev. X 7, 011026 (2017).

Machado, F., Else, D. V., Kahanamoku-Meyer, G. D., Nayak, C. & Yao, N. Y. Long-range prethermal phases of nonequilibrium matter. Phys. Rev. X 10, 011043 (2020).

Pizzi, A., Nunnenkamp, A. & Knolle, J. Classical prethermal phases of matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 140602 (2021).

Vidmar, L. & Rigol, M. Generalized Gibbs ensemble in integrable lattice models. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2016, 064007 (2016).

Mori, T., Ikeda, T. N., Kaminishi, E. & Ueda, M. Thermalization and prethermalization in isolated quantum systems: a theoretical overview. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 51, 112001 (2018).

Berges, J., Borsányi, S. & Wetterich, C. Prethermalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 142002 (2004).

Akemann, G., Kieburg, M., Mielke, A. & Prosen, T. Universal signature from integrability to chaos in dissipative open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 254101 (2019).

Hamazaki, R., Kawabata, K., Kura, N. & Ueda, M. Universality classes of non-Hermitian random matrices. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023286 (2020).

Sá, L., Ribeiro, P. & Prosen, T. Complex spacing ratios: a signature of dissipative quantum chaos. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021019 (2020).

Dahan, D., Arwas, G. & Grosfeld, E. Classical and quantum chaos in chirally-driven, dissipative Bose-Hubbard systems. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 14 (2022).

Prasad, M., Yadalam, H. K., Aron, C. & Kulkarni, M. Dissipative quantum dynamics, phase transitions, and non-Hermitian random matrices. Phys. Rev. A 105, L050201 (2022).

Kawabata, K., Kulkarni, A., Li, J., Numasawa, T. & Ryu, S. Symmetry of open quantum systems: classification of dissipative quantum chaos. PRX Quantum 4, 030328 (2023).

Villase nor, D., Santos, L. F. & Barberis-Blostein, P. Breakdown of the quantum distinction of regular and chaotic classical dynamics in dissipative systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 240404 (2024).

Ferrari, F. et al. Dissipative quantum chaos unveiled by stochastic quantum trajectories. Phys. Rev. Res. 7, 013276 (2025).

Fitzpatrick, M., Sundaresan, N. M., Li, A. C. Y., Koch, J. & Houck, A. A. Observation of a dissipative phase transition in a one-dimensional circuit qed lattice. Phys. Rev. X 7, 011016 (2017).

Fedorov, G. P. et al. Photon transport in a Bose-Hubbard chain of superconducting artificial atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 180503 (2021).

Jouanny, V. et al. High kinetic inductance cavity arrays for compact band engineering and topology-based disorder meters. Nat. Commun. 16, 3396 (2025).

Mei, Q.-X. et al. Experimental realization of the Rabi-Hubbard model with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 160504 (2022).

Rodriguez, S. R. K. et al. Interaction-induced hopping phase in driven-dissipative coupled photonic microcavities. Nat. Commun. 7, 11887 (2016).

Benary, J. et al. Experimental observation of a dissipative phase transition in a multi-mode many-body quantum system. New J. Phys. 24, 103034 (2022).

Debnath, K., Mascarenhas, E. & Savona, V. Nonequilibrium photonic transport and phase transition in an array of optical cavities. New J. Phys. 19, 115006 (2017).

Prem, A., Bulchandani, V. B. & Sondhi, S. L. Dynamics and transport in the boundary-driven dissipative Klein-Gordon chain. Phys. Rev. B 107, 104304 (2023).

Kumar, U., Mishra, S., Kundu, A. & Dhar, A. Observation of multiple attractors and diffusive transport in a periodically driven klein-gordon chain. Phys. Rev. E 109, 064124 (2024).

Parisi, G. On the approach to equilibrium of a Hamiltonian chain of anharmonic oscillators. Eur. Phys. Lett. 40, 357 (1997).

Kolovsky, A. R. & Buchleitner, A. Quantum chaos in the Bose-Hubbard model. Eur. Phys. Lett. 68, 632 (2004).

Kollath, C., Läuchli, A. M. & Altman, E. Quench Dynamics and Nonequilibrium Phase Diagram of the Bose-Hubbard Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 180601 (2007).

Schlagheck, P. & Shepelyansky, D. L. Dynamical thermalization in Bose-Hubbard systems. Phys. Rev. E 93, 012126 (2016).

Carmichael, H. J.Statistical Methods in Quantum Optics 1 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1999).

Polkovnikov, A. Phase space representation of quantum dynamics. Ann. Phys. 325, 1790 (2010).

Iubini, S., Lepri, S. & Politi, A. Nonequilibrium discrete nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Phys. Rev. E 86, 011108 (2012).

Iubini, S., Lepri, S., Livi, R. & Politi, A. Coupled transport in rotor models. New J. Phys. 18, 083023 (2016).

Iubini, S. Coupled transport in a linear-stochastic Schrödinger equation. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2019, 094016 (2019).

Chatterjee, A. K., Kundu, A. & Kulkarni, M. Spatiotemporal spread of perturbations in a driven dissipative Duffing chain: An out-of-time-ordered correlator approach. Phys. Rev. E 102, 052103 (2020).

Komorowski, T., Lebowitz, J. L. & Olla, S. Heat flow in a periodically forced, thermostatted chain. Commun. Math. Phys. 400, 2181 (2023).

Dagvadorj, G. et al. Nonequilibrium phase transition in a two-dimensional driven open quantum system. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041028 (2015).

Dujardin, J., Argüelles, A. & Schlagheck, P. Elastic and inelastic transmission in guided atom lasers: A truncated Wigner approach. Phys. Rev. A 91, 033614 (2015).

Dujardin, J., Engl, T. & Schlagheck, P. Breakdown of Anderson localization in the transport of Bose-Einstein condensates through one-dimensional disordered potentials. Phys. Rev. A 93, 013612 (2016).

Vicentini, F., Minganti, F., Rota, R., Orso, G. & Ciuti, C. Critical slowing down in driven-dissipative Bose-Hubbard lattices. Phys. Rev. A 97, 013853 (2018).

Vicentini, F., Minganti, F., Biella, A., Orso, G. & Ciuti, C. Optimal stochastic unraveling of disordered open quantum systems: Application to driven-dissipative photonic lattices. Phys. Rev. A 99, 032115 (2019).

Schlagheck, P., Ullmo, D., Urbina, J. D., Richter, K. & Tomsovic, S. Enhancement of many-body quantum interference in chaotic bosonic systems: the role of symmetry and dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 215302 (2019).

Seibold, K., Rota, R. & Savona, V. Dissipative time crystal in an asymmetric nonlinear photonic dimer. Phys. Rev. A 101, 033839 (2020).

Deuar, P., Ferrier, A., Matuszewski, M., Orso, G. & Szymańska, M. H. Fully Quantum Scalable Description of Driven-Dissipative Lattice Models. PRX Quantum 2, 010319 (2021).

Blais, A., Grimsmo, A. L., Girvin, S. & Wallraff, A. Circuit quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025005 (2021).

Scully, M. O. and Zubairy, M. S. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511813993Quantum Optics, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Das, A. et al. Light-cone spreading of perturbations and the butterfly effect in a classical spin chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 024101 (2018).

Bilitewski, T., Bhattacharjee, S. & Moessner, R. Temperature dependence of the butterfly effect in a classical many-body system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 250602 (2018).

Schuckert, A. & Knap, M. Many-body chaos near a thermal phase transition. SciPost Phys. 7, 022 (2019).

Bilitewski, T., Bhattacharjee, S. & Moessner, R. Classical many-body chaos with and without quasiparticles. Phys. Rev. B 103, 174302 (2021).

Ruidas, S. & Banerjee, S. Many-body chaos and anomalous diffusion across thermal phase transitions in two dimensions. SciPost Phys. 11, 087 (2021).

Deger, A., Roy, S. & Lazarides, A. Arresting classical many-body chaos by kinetic constraints. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 160601 (2022).

Biondi, M., Blatter, G., Türeci, H. E. & Schmidt, S. Nonequilibrium gas-liquid transition in the driven-dissipative photonic lattice. Phys. Rev. A 96, 043809 (2017).

Minganti, F., Arkhipov, I.I., Miranowicz, A. and Nori, F.Correspondence between dissipative phase transitions of light and time crystals https://arxiv.org/abs/2008.08075 arXiv:2008.08075 [quant-ph] (2020).

Minganti, F., Arkhipov, I. I., Miranowicz, A. & Nori, F. Continuous dissipative phase transitions with or without symmetry breaking. New J. Phys. 23, 122001 (2021).

Minganti, F., Arkhipov, I. I., Miranowicz, A. & Nori, F. Liouvillian spectral collapse in the Scully-Lamb laser model. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043197 (2021).

Scully, M. O. & Lamb, W. E. Quantum theory of an optical maser. I. General Theory. Phys. Rev. 159, 208 (1967).

Yamamoto, Y. & İmamoglu, A. Mesoscopic quantum optics. (John Wiley, New York, 1999).

Minganti, F., Biella, A., Bartolo, N. & Ciuti, C. Spectral theory of Liouvillians for dissipative phase transitions. Phys. Rev. A 98, 042118 (2018).

Garbe, L., Minoguchi, Y., Huber, J. & Rabl, P. The bosonic skin effect: Boundary condensation in asymmetric transport. SciPost Phys. 16, 029 (2024).

Muraev, P. S., Maksimov, D. N. & Kolovsky, A. R. Signatures of quantum chaos and fermionization in the incoherent transport of bosonic carriers in the Bose-Hubbard chain. Phys. Rev. E 109, L032107 (2024).

Marković, D. & Čubrović, M. Chaos and anomalous transport in a semiclassical Bose-Hubbard chain. Phys. Rev. E 109, 034213 (2024).

Xu, S. & Swingle, B. Scrambling dynamics and out-of-time-ordered correlators in quantum many-body systems. PRX Quantum 5, 010201 (2024).

Lieb, E. H. & Robinson, D. W. The finite group velocity of quantum spin systems. Commun. Math. Phys. 28, 251 (1972).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andreas Läuchli for invaluable suggestions on the analysis of local thermal equilibrium. We also acknowledge enlightening discussions with Alberto Biella, Abhishek Dhar, Lorenzo Fioroni, Luca Gravina, Manas Kulkarni, Alberto Mercurio, and Pasquale Scarlino. CA acknowledges the support from the French ANR “MoMA” project ANR-19-CE30-0020 and the support from the project 6004-1 of the Indo-French Centre for the Promotion of Advanced Research (IFCPAR). FF, FM, and VS acknowledge the support by the Swiss National Science Foundation through Projects No. 200020_185015, 200020_215172, and 20QU-1_215928, and by the EPFL Science Seed Fund 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.F. developed the code and performed the numerical simulations. F.F., F.M., and C.A. analyzed and interpreted the results. V.S. supervised F.F. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrari, F., Minganti, F., Aron, C. et al. Chaotic and quantum dynamics in driven-dissipative bosonic chains. Commun Phys 8, 407 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02314-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02314-8