Abstract

The essential cofactor coenzyme A (CoASH) and its thioester derivatives (acyl-CoAs) have pivotal roles in cellular metabolism. However, the mechanism by which different acyl-CoAs are accurately partitioned into different subcellular compartments to support site-specific reactions, and the physiological impact of such compartmentalization, remain poorly understood. Here, we report an optimized liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry-based pan-chain acyl-CoA extraction and profiling method that enables a robust detection of 33 cellular and 23 mitochondrial acyl-CoAs from cultured human cells. We reveal that SLC25A16 and SLC25A42 are critical for mitochondrial import of free CoASH. This CoASH import process supports an enriched mitochondrial CoA pool and CoA-dependent pathways in the matrix, including the high-flux TCA cycle and fatty acid oxidation. Despite a small fraction of the mitochondria-localized CoA synthase COASY, de novo CoA biosynthesis is primarily cytosolic and supports cytosolic lipid anabolism. This mitochondrial acyl-CoA compartmentalization enables a spatial regulation of anabolic and energy-related catabolic processes, which promises to shed light on pathophysiology in the inborn errors of CoA metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

CoASH and CoA esters are vitamin B5-derived essential cofactors that activate carboxylates and lipids to support various metabolic pathways in humans1,2,3,4. These pathways are compartmentalized into different subcellular organelles, including mitochondria for the TCA cycle and fatty acid oxidation (FAO), cytosol for lipid biosynthesis and nucleus for histone modifications. However, the molecular details of how acyl-CoAs are partitioned and communicated across different subcellular compartments have not been fully characterized in the context of cellular physiology. In particular, the mitochondrial matrix contains a very high level of the CoA pool, which constitutes 80–95% of the total cellular CoA contents, as estimated from previous animal tissue studies5,6,7. Yet the exact molecular mechanism responsible for establishing such a high mitochondrial CoA pool remains ambiguous. Here, we reason that either de novo CoA biosynthesis within the mitochondria or a direct CoA uptake across the inner mitochondrial membrane may be responsible.

Cellular CoASH is synthesized from the essential nutrient vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) by a series of sequential enzymatic reactions, with the first and rate-limiting step catalysed by pantothenate kinases (PANKs)8, and the final two steps catalysed by bifunctional CoA synthase (COASY), which generates dephospho-CoASH (dpCoASH) and free CoASH9. Earlier biochemical studies demonstrated CoA biosynthesis activity in both cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions8,10,11. Recent studies have reported that COASY is localized to mitochondria12,13,14, or dual-localized in both cytosol and mitochondria15, raising the possibility that the mitochondrial CoA pool may be generated through local biosynthesis.

Direct CoA transport is indicated by the identification of putative mitochondrial CoA transporters. A yeast genetics study first identified Leu5 as a putative mitochondrial CoA transporter in yeast16 and proposed SLC25A16 (A16) and SLC25A42 (A42) as its human orthologs16,17,18. A16 and A42 belong to the SLC25 family, the largest mitochondrial metabolite transporter family, which facilitates the translocation of metabolites of different structures across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Notably, dysfunction of many of these transporters has been implicated in human diseases19,20,21. In particular, the homozygous A42N291D mutation in humans has been shown to cause mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, a disorder characterized by hypotonia, developmental delay, epilepsy and lactic acidosis22,23,24.

Whether A16 and A42 mediate direct CoA transport under physiological conditions has not been studied. In vitro proteoliposome transport assays have reported the translocation of CoASH, dpCoASH, ADP and adenosine 3′,5′-diphosphate17, and such nucleotide-like ligands for A16 and A42 are supported by phylogenetic analysis of SLC25 family transporters25. However, whether any acyl-CoA species can be directly transported across mitochondria has not been investigated. For instance, the mitochondrial acetyl group of acetyl-CoA is generally considered to be exported indirectly through either citrate shuttling4,26 or acetylcarnitine27, while cytosolic ACLY, ACSS2 and carnitine acyltransferases generate the cytosolic acetyl-CoA pool27,28,29. In addition, if de novo CoA biosynthesis occurs within mitochondria, the directionality of CoA transport is uncertain. A recent study using a fluorescent CoASH biosensor proposed that A42 and A16 mediate CoASH import and dpCoASH export, respectively30. Our previous combinatorial CRISPR screen31 identified a ‘synthetic sick’ interaction between A16 and A42, indicating their functional redundancy. Together, these observations highlight the need for a systemic investigation of A16 and A42 in the context of cellular metabolism to clarify their roles in mitochondrial CoA transport and compartmentalization.

The major roadblock for addressing these questions lies in the technical difficulty of profiling different acyl-CoA species from human cells. Upon conjugation with different carboxylates and fatty acids, these acyl-CoAs become transient metabolic intermediates of very low abundance and exhibit varying hydrophobicities owing to different acyl-chain lengths. Previous liquid chromatography (LC) methods achieved extraordinary separation and detection of short-chain acyl-CoAs32,33,34,35,36, while other LC methods have been reported for long-chain acyl-CoAs33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Another chemical ligation method that transfers the acyl chain to CysTPP enables pan-chain analysis but cannot simultaneously measure free CoASH or distinguish other acyl-donors43. Recently, fluorescent protein sensors for free CoASH30 and acetyl-CoA44 have been reported with spatial and temporal resolution; however, probes for other acyl-CoAs are not yet available. Therefore, a simple, sensitive method that allows simultaneous profiling of acyl-CoAs across different chain lengths is critically needed to elucidate the subcellular (acyl-)CoA landscape in human cells.

Here, we report an optimized extraction and LC–mass spectrometry (LC–MS)-based acyl-CoA profiling method that allows robust detection of 33 cellular and 23 mitochondrial acyl-CoAs from cultured human cells. Using this method, we revealed a primarily cytosolic CoASH biosynthesis and a mitochondrial CoA pool established by A16 and A42-mediated CoASH uptake. This mitochondrial CoA pool critically supports intra-mitochondrial catabolic pathways, including the TCA cycle and FAO. Our work highlights the significance of acyl-CoA compartmentalization in the spatial regulation of cytosolic anabolism and mitochondrial catabolism.

Results

Pan-chain acyl-CoA profiling from whole cells and mitochondria

We developed an acyl-CoA profiling method to achieve simple extraction, separation and detection of cellular acyl-CoAs across all chain lengths from cultured mammalian cells (Fig. 1a). First, a fast-quenching extraction method, using no-washing, dry-ice-cold 80% methanol, which was initially developed for cofactor metabolite analysis45, was crucial for preserving transient, low-abundance CoA esters, which greatly expanded the scope of detectable acyl-CoAs. Second, a solid phase extraction (SPE) step with high recovery across pan-chain acyl-CoAs46 significantly simplified the sample matrix from whole-cell metabolite extracts. Owing to the much simpler sample matrix in the mitochondrial fraction, this SPE step can be skipped when analysing mitochondrial acyl-CoAs obtained from the rapid immuno-isolated mitochondrial fraction of K562 cells expressing 3×HA–EGFP–OMP25 (HA-MITO)47. Third, an isopropanol-based reverse-phase LC method, modified from a previous long-chain and very long-chain acyl-CoAs LC method42, allowed separation of acyl-CoAs across all chain lengths with significantly varying hydrophobicity (Fig. 1b). A few hydrophilic acyl-CoAs, including CoASH, acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA and succinyl/methylmalonyl(MMA)-CoA, exhibited split peaks (Fig. 1b,c), which were confirmed by accurate mass measurements, tandem MS (MS/MS) or commercial standard retention times. A phosphate-based column priming step48 before the isopropanol-based LC method was important to prevent severe peak tailing in hydrophobic, long-chain acyl-CoAs, thus enabling pan-chain acyl-CoA profiling in a single LC run.

a, Schematic overview of the acyl-CoA profiling workflow. IP, immunoprecipitation; RP, reverse-phase. b, Extracted ion chromatograms showing the LC separation of pan-chain acyl-CoAs. c, Representative abundant acyl-CoAs from whole-cell lysates of human K562 cells. d, Validation of annotated acyl-CoAs by stable isotope labelling (acyl-CoAs, M+4) using [13C315N1]-pantothenate (1 mg l−1, 72 h) or MS/MS (Extended Data Fig. 1). e, Mass shift confirmation of representative acyl-CoAs. Black, the unlabelled acyl-CoAs and their natural isotopic peaks. Red, M+4-labelled acyl-CoAs and their natural isotopic peaks. f, Pan-chain acyl-CoA profiling of whole-cell or mitochondrial fraction from K562 cells expressing HA-MITO tag, highlighting compartment-specific enrichment of cytosolic and mitochondrial acyl-CoAs. N.D., not detected. Data in f are shown as mean ± s.d.; n = 3.

We then applied this optimized method to profile acyl-CoAs from both whole-cell and mitochondrial fractions of the human K562 leukaemia cell line under basal conditions. As expected for whole-cell analysis, acetyl-CoA was the most abundant cellular CoA ester, followed by free CoASH (Fig. 1c), consistent with their central roles in various metabolic pathways3,49. We generated an in silico list of 187 cellular acyl-CoAs based on metabolic pathways, the literature and Human Metabolome Database searches (Supplementary Table 1). Using accurate mass, 33 and 23 acyl-CoAs were consistently detected from the whole-cell and mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 1f), respectively. This represents one of the largest and most diverse ranges of acyl-CoA species detected from cultured human cell lines, which had only been previously achieved by separate LC methods for short-chain and long-chain acyl-CoAs33,34,41.

The identities of these acyl-CoAs were validated by two methods. First, MS/MS analysis of these acyl-CoA species exhibited both common fragment ions corresponding to the charged adenine moiety (m/z = 136.0618) and a neutral loss of adenosine diphosphate M = 507 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The representative short-chain and long-chain acyl-CoAs detected in the samples and standards are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1b. Second, stable isotope labelling upon culturing with [13C315N1]-pantothenate (M+4) for 3 days (Fig. 1d) demonstrated that these acyl-CoA species exhibited a signature M+4 mass shift32,50. The observed mass shifts for representative short-chain and long-chain acyl-CoAs are shown in Fig. 1e. Together, these approaches validated our simplified pan-chain acyl-CoA profiling method, which underpinned our subsequent mechanistic studies in the context of cellular metabolism.

By comparing patterns of different acyl-CoA species profiles from the whole-cell and mitochondrial fractions, we were able to highlight acyl-CoAs that are probably mitochondrially or cytosolically enriched (Fig. 1f). In K562 cells, we found that free CoASH was the most abundant CoA species in the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 1f), consistent with recent reports on the high mitochondrial enrichment of CoASH30,47. Other acyl-CoAs highly enriched in mitochondria included C5:0-CoA and C3:0-(propionyl-)CoA, supporting branched-chain amino acid catabolism and odd-chain FAO; C4:0-DC (dicarboxylic)-(succinyl-)CoA, supporting the TCA cycle; and long-chain C18:1-(oleoyl-)CoA and C16:0-(palmitoyl-)CoA, representing the activation of long-chain fatty acids for subsequent oxidation catabolism (Fig. 1f). We also detected very long-chain acyl-CoAs such as C22:6-CoA in mitochondria, which were canonically believed to be metabolized mainly inside peroxisomes1. By comparison, C2:0-(acetyl-)CoA, C3:0-DC-(malonyl-)CoA and C6:0-OH-DC-(3-HMG-)CoA were de-enriched in the mitochondria, consistent with their cytosolic role in fatty acid and mevalonate biosynthesis49. The different enrichment patterns of these acyl-CoAs highlight the physiological spatial regulation of acyl-CoAs, which crucially supports the compartmentalized metabolism.

COASY, the CoA biosynthesis enzyme, primarily functions in the cytosol, supporting lipid anabolism

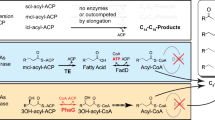

Given that CoA species are charged and therefore cannot freely cross the mitochondrial inner membrane, we explored the mechanism of how CoA species are compartmentalized into mitochondria. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether this compartmentalization is achieved through a mitochondrially localized de novo CoA biosynthesis pathway (COASY-dependent) or a transport process (mediated by putative mitochondrial CoA transporters A16 and A42) (Fig. 2a).

a, Schematic of putative pathways supporting the mitochondrial CoA pool: COASY-mediated de novo biosynthesis or transporter-mediated mitochondrial CoA uptake. b, Western blot of COASY from whole-cell lysate (0.1 million cells) or mitochondrial fraction (ten million cells, 100× enrichment) from K562 cells expressing HA-MITO tag. c, Anti-FLAG and anti-COASY western blots of ectopically expressed C-terminal FLAG-tagged COASYα, COASYβ and endogenous COASY from whole-cell lysate and mitochondrial fraction (~20× enrichment) from K562 cells expressing HA-MITO tag. SHMT2 and VDAC, mitochondrial markers; GAPDH, cytosolic protein marker. d, Anti-FLAG immunofluorescence staining of HeLa cells expressing 3×HA–EGFP–OMP25 (HA-MITO tag) and FLAG-tagged COASYα. Magnified view of framed areas is shown on the right. Scale bars, 5 μm. e, COASY isoform expression from human tissues with major transcripts (bottom) annotated by translation start site (arrows). Data were obtained from the GTEx portal, GTEx Analysis Release v.10 and dbGaP accession number phs000424.v10.p2. Data in b, c and d are representative of experiments that were independently repeated at least two times with similar results.

We first revisited COASY localization in human K562 cells. We prepared protein lysates from either whole-cell or immuno-isolated HA-MITO tagged mitochondria and performed western blotting analysis using anti-COASY (Fig. 2b). Endogenous COASY was present in both the whole-cell and rapid immuno-isolated mitochondrial fractions (100× enriched in cell number). However, only ~10% of the total COASY was found in the mitochondrial fraction, in contrast to a major enrichment of the mitochondrial matrix protein SHMT2 and the mitochondrial outer membrane protein VDAC (Fig. 2b).

Mammalian COASY has been reported to have two splicing variants: COASYα, which is ubiquitously expressed, and COASYβ, which contains an additional 29 residues at the amino terminus and is considered primarily expressed in the brain, with proposed mitochondrial localization13. To investigate the subcellular localization of COASY, we tested carboxy-terminal FLAG-tagged human COASYα and COASYβ in K562 cells. Ectopically expressed COASYα-FLAG was present at a much higher level than the endogenous COASY, as shown by anti-COASY western blot, and only a small fraction was present in the mitochondria (Fig. 2c), consistent with the localization pattern of endogenous COASY (Fig. 2b). Immunofluorescence staining of HeLa cells expressing COASYα-FLAG using anti-FLAG antibody revealed a diffused, cytosolic localization of COASYα with little enrichment to mitochondria labelled by HA-MITO tag (Fig. 2d). COASYβ-FLAG was expressed at a much lower level and was not detected in the mitochondrial fraction, despite a 20× enrichment in input cell number (Fig. 2c), hinting that COASYβ could not be stably expressed in the cells and is not mitochondria-enriched. In addition, despite the previously reported COASYβ expression in the brain, mining human isoform expression of COASY in different tissues (GTEx portal) detected only two highly expressed, functional isoforms, both of which encode COASYα (ENST00000421097.6 and a longer one, ENST00000393818.3). The COASYβ isoform was not expressed in any human tissues (Fig. 2e), suggesting that it is not physiologically functional. Taken together, these data allowed us to conclude that endogenous COASY is predominantly expressed as the α isoform and is cytosolic, supporting a primarily cytosolic CoA biosynthesis pathway.

We next investigated the physiological consequences of COASY CRISPR knockout (KO) in human cell lines. CRISPR KO of COASY in both K562 (Fig. 3a) and HeLa cells led to severe growth defects, underscoring a crucial function of CoA biosynthesis for cell viability (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 2d). Whole-cell polar metabolite profiling identified a defect in lipid biosynthesis, with significant accumulation of several lipid biosynthesis precursors in COASY KO cells (Fig. 3c–e and Extended Data Fig. 2a–c,e). These accumulated metabolites included malonate, the acyl-donor for fatty acid biosynthesis precursor malonyl-CoA; 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate (3-HMG), the acyl-donor for 3-HMG-CoA, which supports the mevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis49; and CDP-choline, the headgroup of phospholipid phosphatidylcholines. The accumulation of these lipid precursors suggested a blockade of CoA-dependent lipid biosynthesis, probably caused by the loss of CoA cofactors in the cytosol upon COASY loss.

a, Anti-COASY western blot from COASY CRISPR KO K562 cells generated with two guides. GAPDH, loading control. b, Left, cell proliferation rate of control (Ctrl) and COASY CRISPR KO K562 cells. Right, proliferation fold change of Ctrl and COASY KO cells on day 6. The y axis is in log2 scale. c, Volcano plot showing whole-cell small polar metabolite profiling from Ctrl and COASY KO (sgRNA #1) K562 cells. Accumulated and depleted metabolites in COASY KO cells are marked in red and blue, respectively. Metabolites that changed consistently in two COASY KO cell lines (see Extended Data Fig. 2) are labelled. d, LC–MS peak intensities of malonate, 3-HMG and CDP-choline in Ctrl and COASY KO (sgRNA #1) cells. e, Schematic of cytosolic lipid anabolic pathways. The accumulated precursors in COASY KO cells are highlighted in red. f, Whole-cell acyl-CoA profiling in Ctrl and COASY KO (sgRNA #1) K562 cells, showing a significant decrease in pan-chain acyl-CoA levels in COASY KO cells. The y axis is in log10 scale. g, Representative short-chain and long-chain acyl-CoAs in the Ctrl and COASY KO cells. The y axis is in linear scale. Data are expressed as scatter dot plots with mean (f) or mean ± s.d. (b, d, g); n = 3. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (b) or two-tailed Student’s t-test (c, d, f, g). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

We then applied the optimized pan-chain acyl-CoA profiling method and demonstrated a significant reduction of all acyl-CoA species in the COASY KO K562 cells (Fig. 3f,g) and COASY KO HeLa cells (Extended Data Fig. 2f). This reduction was observed in nearly all acyl-CoA species regardless of their chain length and mitochondrial enrichment, as illustrated by representative CoA species shown on a linear scale (Fig. 3g and Extended Data Fig. 2f). The significant reduction in CoA pool is consistent with COASY’s role in cellular CoA biosynthesis, and the unexpected cell survival and residual CoA pool in the COASY KOs might hint at a yet-to-be-characterized compensatory mechanism; for instance, regulation of CoA recycling51.

Consistent with its predominant cytosolic localization, we found that COASY primarily functions to support the whole-cell acyl-CoA pool and cytosolic lipid anabolic pathways. Our data did not support a role of COASY in establishing the mitochondrial CoA pool by de novo biosynthesis, suggesting that alternative mechanisms are probably responsible for sustaining the mitochondrial CoA pool and metabolism.

Double KO of SLC25A16 (A16) and SLC25A42 (A42) impairs TCA cycle and lipid metabolism

We then investigated whether mitochondrial CoA transporters might be required for establishing mitochondrial acyl-CoAs levels. The human genome encodes two putative mitochondrial CoA transporters, SLC25A16 (A16) and SLC25A42 (A42), both of which are ubiquitously expressed in all human tissues (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Although A16 single KO cells grew normally, A42 single KO cells already exhibited a significant proliferation defect, and A16/A42 double KO (DKO) cells showed the most severe growth defect in both K562 (Fig. 4a) and HeLa cells (Extended Data Fig. 6a), confirming the ‘synthetic sick’ interaction between the paralogous gene pairs identified from a previous double CRISPR screen31. The ‘synthetic sick’ growth defect was probably a result of the inhibition on the mitochondrial electron transport chain, given that treatment with antimycin, an electron transport chain complex III inhibitor, abolished the major synthetic defect in the A42 and DKO cells (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Consistently, Seahorse mitochondrial stress assays revealed that A16/A42 DKO cells exhibited lower basal and maximum respiration, indicating compromised mitochondrial bioenergetics (Fig. 4b).

a, Left, cell proliferation rate of Ctrl, SLC25A42 KO, SLC25A16 KO and A16/A42 DKO K562 cells. Right, the proliferation rate on day 9. The dotted line denotes the expected log fold change based on the additive effects from A42 and A16 single KOs, if there were no genetic interactions. b, Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) for Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO K562 cells during a Seahorse Mito Stress Test (n = 4). c, Volcano plot of annotated mitochondrial small polar metabolite profiling from Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO K562 cells, highlighting the changes of the TCA cycle intermediates. Accumulated and depleted metabolites in DKO cells are marked in red and blue, respectively. d, Volcano plot showing the untargeted analysis of mitochondrial small polar metabolite profiling from Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO K562 cells, highlighting a significant depletion of CoASH and succinyl/MMA-CoA, and accumulation of acylcarnitines (see Extended Data Fig. 4). e, LC–MS peak intensities of mitochondrial CoASH, succinyl/MMA-CoA, α-KG and two representative acylcarnitines. f, Basal and FCCP-mediated uncoupled OCR for Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO K562 cells during a Seahorse FAO stress assay using palmitate as the sole fuel source (n = 5). g, Stable isotope tracing of A16/A42 DKO K562 cells using [U-13C5]-glutamine (2 mM for 2 h). The y axis shows the natural abundance-corrected isotopologue fraction. All data are expressed as mean ± s.d.; n = 3 unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed Student’s t-test (c, d), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (a, f, g) or Fisher’s least significant difference test (e). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05.

To further characterize the impact of A16/A42 loss on mitochondrial metabolism, we immuno-isolated mitochondria from DKO and control K562 cells expressing the HA-MITO tag and performed polar metabolite profiling by LC–MS (Fig. 4c,d). Analysing data by annotated metabolites first identified a striking, over tenfold accumulation of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and a significant decrease in downstream TCA cycle intermediates, including succinate, fumarate and malate, in the DKO mitochondria (Fig. 4c), suggesting a blockade at the CoA-consuming α-KG dehydrogenase complex (αKGDHc) step in the TCA cycle.

We then performed [U-13C5]-glutamine tracing in the DKO K562 cells to follow the oxidative and reductive branches of the TCA cycle. During the 2 h labelling, oxidation of M+5 α-KG leads to M+4 labelling in other TCA cycle intermediates, while reductive carboxylation results in M+5 labelling for citrate and M+3 labelling in other metabolites (Fig. 4g). In K562 cells, consistent with the unlabelled mitochondrial metabolite profiling (Fig. 4c,e), the total pool size (Extended Data Fig. 5a) of α-KG increased, while both the total pool size and M+4 pool size of fumarate and malate were significantly decreased in the DKO, supporting a major blockade at the αKGDHc step (Extended Data Fig. 5a). The M+4 labelling fractions (Fig. 4g) of citrate decreased in the DKO cells; while the M+5 citrate, M+3 malate, M+3 fumarate and M+3 aspartate fractions significantly increased, suggesting a reduction of oxidative TCA cycle flux and an upregulation of reductive pathway flux (Fig. 4g). We then validated a similar TCA cycle rewiring in the DKO HeLa cells (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d), which exhibited a more pronounced increase in the M+3 labelling of pathway intermediates, suggesting a major shift toward the reductive pathway flux under impaired mitochondrial CoA transport in these cells (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d).

Analysing unannotated metabolic features from the mitochondrial metabolite profiling data revealed acylcarnitines accumulation and CoA depletion in the DKO mitochondria (Fig. 4d). A closer inspection of the data indicated that CoASH and succinyl/MMA-CoA, two abundant mitochondrial (acyl-)CoAs, were among the most depleted metabolites in the DKO mitochondria (Fig. 4d). The most accumulated metabolites in the DKO mitochondria included several acylcarnitines (Fig. 4d), suggesting an inability to convert acylcarnitines to acyl-CoAs for subsequent FAO. The identities of the acylcarnitines were further confirmed by MS/MS signature fragmentation spectra analysis52 (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). Although the CoA reduction was already observed in the single KOs, the major accumulation of α-KG and acylcarnitines was only observed in the DKOs and not in the single KOs (Fig. 4e). The phenotype was also validated in DKO HeLa cells (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Together, these data suggest that mitochondria can tolerate moderate reductions in CoA levels to maintain the basal TCA cycle and FAO.

We then further characterized lipid catabolism in the DKO K562 cells by performing the Seahorse FAO stress test using palmitate as the only fuel source. Notably, DKOs exhibited significantly lower basal respiration than controls, and palmitate was only able to increase the basal respiration in the controls but not DKOs (Fig. 4f). Although FCCP significantly induced palmitate-mediated respiration in the control cells, DKOs showed no stimulated palmitate respiration (Fig. 4f), confirming a blockade of lipid catabolism in the DKOs.

We then investigated the acyl-CoA landscape in both A16/A42 DKO mitochondrial and whole-cell fractions using our acyl-CoA profiling method. In K562 cells, the DKO mitochondria revealed a severe depletion of both CoASH and its precursor, dpCoASH (Fig. 5a,b), supporting that both CoASH and dpCoASH are ligands of A16/A42, consistent with the previous in vitro proteoliposome evidence for human A42 (ref. 17). Loss of both A16 and A42 also led to a severe depletion of several mitochondria-enriched short-chain acyl-CoAs in the mitochondrial fraction, including propionyl-CoA, succinyl/MMA-CoA and C5:0-CoA (Fig. 5a,b). By comparison, acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA and (iso)butyryl-CoA exhibited smaller to no reduction in the mitochondrial fraction, supporting their cytosolic enrichment (Fig. 5a,b). Long-chain acyl-CoAs, by contrast, did not show a reduction (Fig. 5a,b), probably because of the accumulation of long-chain acylcarnitines and the blockade of FAO in the DKO mitochondria (Fig. 4d–f). The same pattern of depletion in mitochondrially enriched short-chain acyl-CoAs was also validated in HeLa DKO mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b), confirming that both A16 and A42 are essential for mitochondrial CoA uptake.

a, Mitochondrial acyl-CoA profiling in Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO K562 cells (y axis in log10 scale), highlighting a significant decrease of mitochondria-enriched short-chain acyl-CoAs in the DKO mitochondria. b, Representative acyl-CoAs from a, including significantly decreased dpCoASH and free CoASH, mitochondria-enriched short-chain acyl-CoAs (propionyl-CoA, succinyl/MMA-CoA, C5:0-CoA), cytosolic-enriched acyl-CoAs (acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, (iso)butyryl-CoA) and long-chain C16:0-CoA in Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO mitochondria (y axis in linear scale). c, Whole-cell acyl-CoA profiling in Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO K562 cells (y axis in log10 scale). Data are expressed as scatter dot plots with mean (a, c) or mean ± s.d. (b); n = 3. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05.

Acyl-CoA profiling of DKO whole-cell lysates also revealed a significant but less severe reduction in free CoASH, short-chain and several medium-chain acyl-CoAs (Fig. 5c). Given that the level of reduction was less severe than that in the mitochondrial fraction, and the cytosolic malonyl-CoA did not decrease in the DKO whole-cell fraction, our data suggest that this decline in whole-cell acyl-CoA level was a result of depletion of the mitochondrial acyl-CoA pool, which constitutes a major fraction of the total cellular CoA pool.

Disease mutant A42N291D and a matrix-targeting COASY cannot support the mitochondrial CoA pool

The mitochondrial CoA reduction in the A42 single KO K562 cells allowed us to directly examine the impact of human disease mutants. A homozygous missense mutation, N291D, in A42 has been identified in several cases of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy22,23,24, and structural prediction of A42 hinted that this mutation impairs the positively charged substrate-binding pockets22. To test the disease mutant, we ectopically expressed A42WT, A42N291D, as well as a matrix-targeting COASY (MTS-COASY) construct in the A42 single KO K562 cells. Western blotting of mitochondrial lysates confirmed that A42WT, A42N291D and MTS-COASY were properly targeted to the mitochondria (Fig. 6a). Both ectopic A42WT and A42N291D were expressed at a much higher level than the endogenous A42 (Fig. 6a), suggesting that A42N291D does not affect A42 protein stability (Fig. 6a). Using mitochondrial acyl-CoA profiling, we confirmed a reduced level of mitochondrial short-chain acyl-CoAs in the A42 KO cells, which was significantly upregulated upon A42WT overexpression (Fig. 6b). By contrast, both A42N291D and MTS-COASY failed to rescue and exhibited similar reduced mitochondrial CoA levels as the A42 KO cells (Fig. 6b). The data directly demonstrated that mitochondrial CoA enrichment critically relies on CoA transporters, and the human disease mutant A42N291D is a loss-of-function mutant that cannot import CoA.

a, Anti-COASY and anti-SLC25A42 western blot of mitochondrial lysates from Ctrl and A42 KO K562 cells expressing EGFP (–), C-terminal FLAG-tagged A42WT, A42N291D and mitochondrial localized MTS-COASY. VDAC, loading control. b, Measurements of mitochondria-enriched acyl-CoAs from mitochondrial fractions. All data are expressed as mean ± s.d.; n = 3 unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test. ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05.

The functional characterization of MTS-COASY and disease mutant A42N291D was further validated by a yeast complementation assay. Leu5, the single yeast ortholog of A16 and A42 (refs. 16,25), is crucial for yeast to grow on glycerol, an unfermentable carbon source for mitochondrial respiration16,17,18. We therefore generated leu5Δ yeast strains and transformed these strains with yeast Leu5 or corresponding human protein-expressing plasmids. Despite a significant enrichment of MTS-COASY in the mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 8a), neither COASY nor MTS-COASY was able to rescue the leu5Δ growth defect on glycerol (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Similarly, A42N291D failed to rescue, while yeast Leu5, human A42 and A16 all successfully rescued the leu5Δ growth defect on glycerol (Extended Data Fig. 8c). These data further corroborated our findings that the mitochondrial CoA pool depends on the CoA transporter.

A16 and A42 are required for mitochondrial import of CoASH

To directly investigate the role of A16 and A42 in mitochondrial CoA import, we performed in vitro mitochondria-based uptake assays using stable-isotope-labelled CoAs, with labelling on either the CoA moiety or the acyl moiety.

We first examined the role of A42 in mitochondrial CoA uptake using immuno-isolated mitochondria from A42 KO and A42 KO cells re-expressing A42WT. As stable-isotope-labelled CoASH is not commercially available, we produced the M+4 stable-isotope-labelled acyl-CoAs with labelling on the CoA moiety as transporting ligands by co-culturing cells with [13C315N1]-pantothenate (M+4) for 3 days, followed by acyl-CoA extraction and SPE purification (Fig. 7a). Indeed, after 6 min incubation, M+4-labelled free CoASH was imported into A42WT-expressing mitochondria at a significantly higher level than into A42 KO mitochondria (Fig. 7b), suggesting that A42 is important for mitochondrial CoA import. We then performed the same uptake assay in A16/A42 DKO cells and also observed a significant reduction in CoASH uptake (Fig. 7c), confirming that both A16 and A42 are required for CoASH import.

a, Schematic of the mitochondrial uptake assay of the CoA pool using immuno-isolated mitochondria from K562 cells expressing HA-MITO tag. The substrate pool [13C315N1]-acyl-CoAs, including CoASH (M+4, stable isotope labelling at the CoA moiety marked in red), was prepared from K562 cells after [13C315N1]-pantothenate labelling for 3 days. b, Labelled CoASH (M+4) from the mitochondrial uptake assay of CoA pool using A42 KO and A42 KO re-expressing A42WT K562 cells. The input level of CoASH (M+4) from the 5× diluted substrate pool is shown. c, Labelled CoASH (M+4) (left) and labelled acetyl-CoA (M+4) (right) from the mitochondrial uptake assay of CoA pool using Ctrl and A16/A42 DKO mitochondria. The input levels of CoASH (M+4) and acetyl-CoA (M+4) from the 5× diluted substrate pool are shown. d, Schematic of mitochondria acetyl-CoA uptake assay of 13C2-acetyl-CoA (M+2) at 10 μM using immuno-isolated mitochondria from K562 cells expressing HA-MITO tag. The substrate 13C2-acetyl-CoA (M+2) contained labelling at the acetyl moiety, marked in red. e, Labelled acetyl-CoA (M+2) from the mitochondrial acetyl-CoA uptake assay using Ctrl mitochondria. The input level of 13C2-acetyl-CoA (M+2) from the 5× diluted input is shown. f, Summary diagram highlighting the physiological role of A16 and A42 in mitochondrial CoASH uptake and in regulating mitochondrial CoA metabolism. All data are expressed as mean ± s.d.; n = 3 unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Interestingly, in this assay, we also detected M+4-labelled acetyl-CoA in the mitochondria, with higher levels in the control compared to the DKO mitochondria (Fig. 7c). This mitochondrial acetyl-CoA labelling could result either from a direct uptake or from an intra-mitochondrial metabolic conversion of the imported M+4-labelled CoASH.

We then performed the uptake assay using the commercially available pure acetyl-CoA substrate, with labelling on the acetyl group (13C2-acetyl-CoA; Fig. 7d). After 6 min incubation at room temperature (20–25 °C), only a negligible amount of 13C2-acetyl-CoA was detected in the isolated mitochondria from the control cells (Fig. 7e), although an approximately doubled input of acetyl-CoA substrate was used (Fig. 7c,e). Although this minimal amount of detected M+2-labelled acetyl-CoA could be either bound to the mitochondrial outer membrane or directly imported, the noticeable level of M+4-labelled acetyl-CoA in the mitochondria (seen in Fig. 7c) was probably derived from the imported free CoASH through high-flux catabolic pathways.

Discussion

Our cellular metabolism and in vitro mitochondrial uptake assays revealed that the mitochondrial CoA pool is established through a free CoASH uptake process mediated by the mitochondrial transporters A42 and A16, and that the COASY-dependent de novo CoA biosynthesis is primarily cytosolic. We identified a selective depletion of several mitochondrially enriched acyl-CoAs upon loss of A16/A42, including known catabolic pathway intermediates CoASH, propionyl-CoA, succinyl/MMA-CoA and C5:0-CoA. Depletion of these mitochondrial acyl-CoAs in the DKOs was accompanied by TCA cycle rewiring and impaired lipid catabolism, suggesting that this mitochondrial CoA compartmentalization allows spatial separation of mitochondrial catabolic pathways from cytosolic processes (Fig. 7f). Additionally, the depletion of the mitochondrial CoA pool in the DKOs led to a secondary decrease in the whole-cell levels of short-chain and medium-chain acyl-CoAs, which highlights the critical role of the mitochondrial CoA pool as the predominant cellular CoA pool and emphasizes the importance of CoA compartmentalization for the spatial regulation of cellular metabolism.

Our study provides direct evidence that the mitochondrial total CoA pool is established by A16/A42-mediated transport. Previous studies using animal tissues such as rat heart5 and liver6,7 identified that 80–95% of total cellular CoA is localized inside the mitochondria, with the cytosolic and mitochondrial total CoA concentrations estimated to be 14–100 μM (refs. 5,53) and 2–5 mM (refs. 5,7,53), respectively. Recent studies in human cells also corroborated these findings. An enrichment of the mitochondrial CoASH pool from HeLa cells was reported by MS analysis, in which whole-cell and mitochondrial matrix CoASH concentrations were at 14 μM and 42 μM, respectively47; or from other human cell lines by CoASH sensor, at 66–85 μM and 258–816 μM, respectively30. Given that A16/A42 DKO led to a severe mitochondrial CoA depletion (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 7a,b), we conclude that there is a net import of CoA from the cytosol into the mitochondria under physiological conditions against its concentration gradient. Interestingly, CoA uptake was shown to be dependent on both mitochondrial membrane potential and H+ gradients54, hinting at a putative secondary active transport mechanism.

Our pan-chain acyl-CoA profiling and mitochondrial uptake assay from the KO cells provide strong evidence for a direct transport of free CoASH mediated by A16/A42. Using in vitro mitochondria-based uptake assays, we showed that acetyl-CoA, the most abundant cellular short-chain acyl-CoA, is unlikely to be directly imported into mitochondria (Fig. 7d,e), and this result is consistent with the need for citrate shuttle and carnitine shuttle to translocate acetyl-CoAs and fatty acids4,27,55. Our observation that mitochondrial dpCoASH also decreased in DKO mitochondria in the same way as CoASH strongly supports that dpCoASH is also a transporting ligand under physiological conditions. This finding is in line with a previous in vitro proteoliposome assay for A42 (ref. 17).

Our study provides a valuable analytic tool to profile compartment-specific, acyl-CoA landscapes in human cells, shedding light on the pathophysiology of inborn errors of CoA metabolism. The A42 homozygous missense mutation N291D has been shown to cause encephalomyopathy with a variable phenotypic spectrum, including hypotonia, developmental delay, epilepsy and lactic acidosis22,23,24; and a homozygous, putative deleterious A16 missense mutation has been implicated in fingernail dysplasia with no obvious bioenergetic or neurological impairments56. In our study, our mitochondrial acyl-CoA profiling provided direct experimental evidence that the A42N291D mutation is a loss-of-function catalytic variant, which supports previous structural modelling that predicted the disease mutation disrupts a positively charged CoA binding pocket of A42 (ref. 22). Interestingly, mutations in enzymes involved in de novo CoA biosynthesis, PANK2 and COASY, have been implicated in neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation, with clinical signature of abnormal iron accumulation in basal ganglia57,58. Together, our results underscore the importance of comparative analysis of compartment-specific acyl-CoA landscapes as a critical axis for probing core metabolic processes and the pathophysiology of human diseases.

Methods

Cell culture

Human cell line K562 cells were purchased from ATCC (CCL-243). HeLa-M cells were a subclone of HeLa cells (ATCC, CCL-2) from the P. De Camilli laboratory. K562 and HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher, 11995) with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, F2442) and 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, 15140122). For [13C315N1]-pantothenate labelling experiments, K562 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium without pantothenic acid (US Biological Life Sciences, R8999-01A), supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS (dFBS; Thermo Fisher, A3382001), 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, 15140122) and 1 mg l−1 [13C315N1]-pantothenate (Sigma-Aldrich, 705837). For the [U-13C5]-glutamine tracing assay, cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% dFBS, 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin and 2 mM [U-13C5]-glutamine (Med Chem Express, HY-N0390S1). All cells used in the study were confirmed to be mycoplasma-free by regular testing using the Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit (ATCC, 30-1012K). Unless otherwise stated, the experiments in this study were conducted with K562 cells. All experiments performed with HeLa cells are marked in the figures.

Plasmid and cloning

The single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for spCas9 were synthesized and cloned into the lentiCRISPR v2 vector (Addgene, 52961) for single KO cell line generation. The sgRNAs for spCas9 were synthesized and cloned into either the lentiCRISPR v2 vector (Addgene 52961, puromycin selection cassette) or the pXPR_BRD051 vector (Addgene 98291, hygromycin selection cassette) for the DKO cell line generation. For studies involving protein overexpression, EGFP or human SLC25A42WT, SLC25A42N291D, COASYα, COASYβ and mitochondrial MTS-COASY proteins with a C-terminal FLAG-tag following a flexible linker were custom-synthesized (GenScript) and cloned into a pLYS5 lentiviral vector (Addgene, 50054). For mitochondria rapid immuno-isolation, pMXs-3×HA-EGFP-OMP25 (Addgene, 83356) was used to tag the mitochondrial outer membrane protein OMP25.

The sgRNA sequences and the cDNA sequences used in our study are listed below:

OR2M4-chr01 (OR2) CCATAAGGGACAGTTGACTG

OR11A1-chr06 (OR11) GTGATGCCAAAAATGCTGGA

The above two cutting control sgRNAs were from a previous study31.

SLC25A16 CGGACCCTAACCATGTCAAG

SLC25A42 TGTCGTTCCAGCCAGTGCGC (ordered from GenScript)

COASY #1 AGCGAGGAGACCTATCGTGG

COASY #2 ATGACATCAAAAGTCAAGGA

Codon optimized COASYα-FLAG

ATGGCCGTTTTCAGAAGCGGCCTGCTAGTGCTGACGACCCCTCTCGCCTCTCTGGCCCCTAGACTGGCCAGCATCCTGACCAGCGCCGCTAGACTCGTGAACCACACACTGTACGTGCACCTGCAGCCAGGCATGAGCCTGGAAGGACCTGCCCAACCCCAGAGCTCACCCGTGCAGGCCACCTTCGAGGTGTTGGACTTCATCACACACCTGTATGCCGGCGCTGATGTGCATAGACACTTAGATGTGCGGATCCTGCTGACCAACATTAGAACAAAGTCCACATTCCTGCCTCCTCTGCCAACCAGCGTGCAGAATCTGGCTCATCCTCCTGAGGTGGTGCTGACCGACTTTCAGACCCTGGATGGCAGCCAATACAACCCTGTGAAGCAGCAACTGGTGCGGTACGCCACAAGCTGCTACTCATGCTGCCCCAGGCTGGCCAGCGTGCTGCTGTACAGCGACTACGGCATCGGAGAGGTGCCTGTGGAACCCCTGGATGTGCCCCTGCCCAGCACCATCCGGCCCGCCAGCCCTGTTGCTGGGTCCCCAAAGCAACCAGTGAGAGGTTATTACAGAGGCGCAGTGGGCGGAACATTCGACAGACTCCATAATGCCCACAAGGTGCTGCTGAGCGTGGCCTGCATCCTGGCCCAGGAGCAGCTGGTGGTCGGCGTGGCCGACAAGGACCTGTTAAAATCCAAGCTGCTCCCAGAACTGCTGCAGCCTTACACCGAGCGGGTGGAACACCTGAGCGAGTTCCTGGTCGATATCAAGCCCAGCCTGACCTTTGACGTGATTCCTCTGCTGGACCCCTACGGCCCCGCCGGATCCGATCCTTCTCTCGAGTTCCTGGTCGTGTCTGAGGAAACCTACCGGGGCGGCATGGCCATCAACAGATTCCGGCTTGAAAACGACCTGGAAGAACTGGCACTGTACCAGATCCAGCTGCTCAAAGACCTGAGACACACCGAGAACGAGGAAGATAAGGTTTCTTCTAGCAGCTTCAGACAGAGAATGCTGGGAAATCTGCTGAGACCTCCATACGAGAGACCTGAGCTGCCTACCTGTCTGTACGTGATCGGCCTGACCGGCATCAGCGGCAGCGGCAAGTCCAGCATCGCTCAGAGACTGAAAGGCCTGGGAGCCTTCGTGATCGACAGCGACCACCTGGGCCACAGAGCCTACGCCCCTGGCGGCCCTGCTTACCAGCCTGTGGTCGAGGCCTTTGGCACAGATATTCTGCACAAGGACGGCATCATCAACCGCAAGGTGCTGGGAAGCAGAGTGTTCGGCAACAAGAAACAGCTGAAGATCCTGACCGACATCATGTGGCCTATCATCGCCAAGCTGGCCCGGGAAGAGATGGACCGGGCCGTGGCCGAGGGCAAAAGAGTTTGTGTGATCGACGCCGCCGTGCTGCTGGAAGCCGGCTGGCAGAACCTGGTGCACGAGGTGTGGACCGCCGTGATCCCTGAGACAGAGGCCGTGCGCAGAATCGTGGAAAGAGATGGCCTGAGCGAGGCCGCTGCCCAGAGCAGACTGCAGTCTCAGATGAGCGGCCAGCAGCTGGTGGAACAGAGCCACGTGGTCCTGAGCACACTGTGGGAGCCTCACATCACCCAGCGGCAGGTGGAAAAGGCCTGGGCCCTGCTGCAAAAGCGGATCCCCAAGACACACCAGGCCCTGGACTCTAGAGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTATGGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGTAA

Codon optimized COASYβ-FLAG

ATGAGAACACCTAGACTGAGAGCCCAGCCTAGAGGCGCCGTGTACCAGGCCCCTAGCCCCCCACCAGCCCCTGTGGGCCTGGGCTCCATGGCCGTGTTCCGGAGCGGCCTGCTGGTGCTGACGACCCCTCTGGCCTCTCTGGCCCCACGGCTGGCCAGCATCCTGACCAGCGCCGCAAGACTGGTGAACCACACCCTGTACGTGCACCTGCAGCCCGGCATGTCTCTGGAAGGCCCCGCCCAGCCTCAGAGCAGCCCCGTCCAGGCTACATTCGAGGTGCTGGATTTCATCACACACCTCTACGCCGGCGCCGACGTGCACCGGCACCTGGACGTGCGAATCCTGCTGACAAATATCAGAACCAAAAGCACATTTCTGCCCCCTCTGCCTACATCTGTGCAGAACCTGGCCCATCCTCCAGAGGTGGTGCTGACAGACTTCCAGACCCTGGATGGCTCTCAGTACAACCCCGTGAAGCAACAACTGGTGAGATACGCCACCAGCTGTTACAGCTGCTGCCCTAGACTGGCCAGCGTGCTGCTGTATTCTGACTACGGAATCGGGGAGGTGCCTGTGGAACCTCTGGACGTGCCCCTGCCCAGCACAATCCGGCCCGCCAGCCCTGTGGCTGGCTCTCCCAAGCAGCCTGTGCGCGGCTACTACCGGGGCGCTGTGGGCGGCACCTTTGACAGACTGCACAACGCCCACAAGGTGCTGCTGAGCGTGGCCTGCATCCTGGCTCAGGAGCAGCTGGTGGTGGGAGTGGCCGATAAGGACCTGCTGAAAAGCAAGCTGCTGCCTGAACTGCTGCAGCCTTACACCGAACGGGTGGAGCACCTGTCCGAATTCCTGGTCGACATCAAGCCTTCTCTGACCTTTGATGTTATTCCTCTGCTGGATCCTTACGGCCCTGCCGGATCGGACCCTAGCCTGGAATTCCTGGTGGTTTCCGAGGAAACCTACAGGGGCGGAATGGCCATCAACCGGTTCAGACTCGAAAACGACCTGGAAGAGCTGGCCCTGTACCAGATCCAGCTGCTGAAAGATCTGAGACACACCGAGAACGAGGAGGACAAGGTGTCCAGCTCCAGCTTCAGACAGAGAATGCTGGGCAATCTGCTTAGACCCCCGTACGAGCGGCCTGAGCTGCCTACCTGTCTGTACGTGATCGGACTGACCGGAATCAGCGGTAGCGGCAAGAGCAGCATCGCCCAGAGACTGAAGGGCCTCGGCGCTTTCGTGATCGACAGCGACCACCTGGGCCACAGAGCCTATGCCCCTGGCGGACCTGCCTACCAGCCTGTCGTGGAAGCCTTCGGCACAGATATTCTCCATAAGGACGGCATCATCAATAGAAAGGTGCTGGGAAGCAGAGTTTTCGGCAACAAGAAGCAGCTGAAGATCCTGACCGACATCATGTGGCCTATCATCGCCAAGCTGGCCAGAGAGGAAATGGACCGGGCTGTGGCCGAGGGCAAAAGAGTGTGCGTGATCGACGCCGCCGTGCTGCTGGAAGCCGGCTGGCAGAACCTGGTGCACGAGGTGTGGACCGCCGTCATCCCTGAGACAGAGGCTGTCCGGAGGATTGTGGAGAGAGATGGCCTGTCCGAGGCCGCTGCCCAAAGCAGACTGCAGTCTCAGATGAGCGGCCAGCAGCTCGTGGAACAGAGCCACGTGGTGCTGAGCACCCTGTGGGAGCCCCACATCACCCAGCGGCAGGTGGAGAAAGCCTGGGCCCTTCTGCAAAAACGGATCCCCAAGACCCACCAGGCCCTGGACTCTAGAGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTATGGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGTAA

Codon optimized SLC25A42WT-FLAG

ATGGGCAACGGCGTGAAGGAAGGCCCTGTGCGGCTGCATGAAGATGCCGAGGCCGTGCTGAGCAGCAGCGTGTCCTCCAAGCGGGACCACCGGCAGGTGCTGTCTAGCCTGCTGAGCGGAGCTCTGGCCGGCGCTCTGGCTAAGACCGCCGTGGCCCCTCTGGATAGAACCAAGATCATCTTTCAGGTGAGCTCTAAAAGATTCTCCGCTAAAGAGGCCTTCCGGGTGCTGTACTACACCTACCTGAACGAGGGCTTCCTGAGCCTGTGGCGGGGCAATAGCGCTACCATGGTGAGGGTGGTCCCCTACGCCGCTATCCAGTTCAGCGCCCACGAGGAGTATAAGAGAATCCTGGGCAGCTACTACGGCTTTAGAGGCGAGGCCCTGCCCCCCTGGCCTAGACTGTTCGCCGGCGCCCTGGCCGGTACAACCGCCGCCTCTCTGACCTACCCTCTGGACCTGGTGCGCGCCAGAATGGCCGTGACCCCTAAGGAAATGTACAGCAACATCTTTCACGTGTTCATCAGAATTAGCAGAGAGGAAGGACTGAAGACCCTGTACCACGGCTTCATGCCTACAGTGCTGGGCGTTATCCCTTACGCCGGACTCAGTTTTTTCACCTACGAGACACTGAAAAGCCTGCACAGAGAATACAGCGGCAGAAGACAGCCTTACCCATTCGAGAGAATGATCTTCGGCGCATGCGCCGGCCTGATCGGACAGAGCGCCAGCTACCCCCTGGACGTGGTGCGGAGAAGGATGCAAACAGCCGGAGTTACAGGCTACCCTAGAGCCAGCATCGCCAGAACCCTGAGAACAATCGTGCGGGAAGAGGGCGCTGTGCGGGGCCTGTATAAGGGCCTGTCCATGAACTGGGTCAAGGGCCCAATCGCCGTGGGCATCAGCTTCACCACCTTCGACCTTATGCAGATCCTGCTGCGGCACCTCCAGAGCTCTAGAGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTATGGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGTAA

Codon optimized SLC25A42N291D-FLAG

ATGGGCAACGGCGTGAAGGAAGGCCCTGTGCGGCTGCATGAAGATGCCGAGGCCGTGCTGAGCAGCAGCGTGTCCTCCAAGCGGGACCACCGGCAGGTGCTGTCTAGCCTGCTGAGCGGAGCTCTGGCCGGCGCTCTGGCTAAGACCGCCGTGGCCCCTCTGGATAGAACCAAGATCATCTTTCAGGTGAGCTCTAAAAGATTCTCCGCTAAAGAGGCCTTCCGGGTGCTGTACTACACCTACCTGAACGAGGGCTTCCTGAGCCTGTGGCGGGGCAATAGCGCTACCATGGTGAGGGTGGTCCCCTACGCCGCTATCCAGTTCAGCGCCCACGAGGAGTATAAGAGAATCCTGGGCAGCTACTACGGCTTTAGAGGCGAGGCCCTGCCCCCCTGGCCTAGACTGTTCGCCGGCGCCCTGGCCGGTACAACCGCCGCCTCTCTGACCTACCCTCTGGACCTGGTGCGCGCCAGAATGGCCGTGACCCCTAAGGAAATGTACAGCAACATCTTTCACGTGTTCATCAGAATTAGCAGAGAGGAAGGACTGAAGACCCTGTACCACGGCTTCATGCCTACAGTGCTGGGCGTTATCCCTTACGCCGGACTCAGTTTTTTCACCTACGAGACACTGAAAAGCCTGCACAGAGAATACAGCGGCAGAAGACAGCCTTACCCATTCGAGAGAATGATCTTCGGCGCATGCGCCGGCCTGATCGGACAGAGCGCCAGCTACCCCCTGGACGTGGTGCGGAGAAGGATGCAAACAGCCGGAGTTACAGGCTACCCTAGAGCCAGCATCGCCAGAACCCTGAGAACAATCGTGCGGGAAGAGGGCGCTGTGCGGGGCCTGTATAAGGGCCTGTCCATGGACTGGGTCAAGGGCCCAATCGCCGTGGGCATCAGCTTCACCACCTTCGACCTTATGCAGATCCTGCTGCGGCACCTCCAGAGCTCTAGAGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTATGGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGTAA

Codon optimized MTS-COASYα-FLAG (MTS-COASY)

ATGCTGGCTACAAGAGTGTTCAGCCTGGTCGGCAAGAGAGCCATCAGCACCTCTGTGTGCGTGCGGGCCCACGCCGTTTTCAGAAGCGGCCTGCTAGTGCTGACGACCCCTCTCGCCTCTCTGGCCCCTAGACTGGCCAGCATCCTGACCAGCGCCGCTAGACTCGTGAACCACACACTGTACGTGCACCTGCAGCCAGGCATGAGCCTGGAAGGACCTGCCCAACCCCAGAGCTCACCCGTGCAGGCCACCTTCGAGGTGTTGGACTTCATCACACACCTGTATGCCGGCGCTGATGTGCATAGACACTTAGATGTGCGGATCCTGCTGACCAACATTAGAACAAAGTCCACATTCCTGCCTCCTCTGCCAACCAGCGTGCAGAATCTGGCTCATCCTCCTGAGGTGGTGCTGACCGACTTTCAGACCCTGGATGGCAGCCAATACAACCCTGTGAAGCAGCAACTGGTGCGGTACGCCACAAGCTGCTACTCATGCTGCCCCAGGCTGGCCAGCGTGCTGCTGTACAGCGACTACGGCATCGGAGAGGTGCCTGTGGAACCCCTGGATGTGCCCCTGCCCAGCACCATCCGGCCCGCCAGCCCTGTTGCTGGGTCCCCAAAGCAACCAGTGAGAGGTTATTACAGAGGCGCAGTGGGCGGAACATTCGACAGACTCCATAATGCCCACAAGGTGCTGCTGAGCGTGGCCTGCATCCTGGCCCAGGAGCAGCTGGTGGTCGGCGTGGCCGACAAGGACCTGTTAAAATCCAAGCTGCTCCCAGAACTGCTGCAGCCTTACACCGAGCGGGTGGAACACCTGAGCGAGTTCCTGGTCGATATCAAGCCCAGCCTGACCTTTGACGTGATTCCTCTGCTGGACCCCTACGGCCCCGCCGGATCCGATCCTTCTCTCGAGTTCCTGGTCGTGTCTGAGGAAACCTACCGGGGCGGCATGGCCATCAACAGATTCCGGCTTGAAAACGACCTGGAAGAACTGGCACTGTACCAGATCCAGCTGCTCAAAGACCTGAGACACACCGAGAACGAGGAAGATAAGGTTTCTTCTAGCAGCTTCAGACAGAGAATGCTGGGAAATCTGCTGAGACCTCCATACGAGAGACCTGAGCTGCCTACCTGTCTGTACGTGATCGGCCTGACCGGCATCAGCGGCAGCGGCAAGTCCAGCATCGCTCAGAGACTGAAAGGCCTGGGAGCCTTCGTGATCGACAGCGACCACCTGGGCCACAGAGCCTACGCCCCTGGCGGCCCTGCTTACCAGCCTGTGGTCGAGGCCTTTGGCACAGATATTCTGCACAAGGACGGCATCATCAACCGCAAGGTGCTGGGAAGCAGAGTGTTCGGCAACAAGAAACAGCTGAAGATCCTGACCGACATCATGTGGCCTATCATCGCCAAGCTGGCCCGGGAAGAGATGGACCGGGCCGTGGCCGAGGGCAAAAGAGTTTGTGTGATCGACGCCGCCGTGCTGCTGGAAGCCGGCTGGCAGAACCTGGTGCACGAGGTGTGGACCGCCGTGATCCCTGAGACAGAGGCCGTGCGCAGAATCGTGGAAAGAGATGGCCTGAGCGAGGCCGCTGCCCAGAGCAGACTGCAGTCTCAGATGAGCGGCCAGCAGCTGGTGGAACAGAGCCACGTGGTCCTGAGCACACTGTGGGAGCCTCACATCACCCAGCGGCAGGTGGAAAAGGCCTGGGCCCTGCTGCAAAAGCGGATCCCCAAGACACACCAGGCCCTGGACTCTAGAGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTGGTGGATCTATGGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGTAA

Lentivirus production and cell line transduction

HEK293T cells for lentivirus production were obtained from S. Chen’s lab (Yale). Lentivirus production and cell line transduction were performed as previously described59. In brief, for lentivirus production, 0.6 × 106 HEK293T cells were plated on day 0 in a 6 cm dish. On day 1, 600 ng of pMD2.G (Addgene, 12259), 900 ng of psPAX2 (Addgene, 12260) and 1 μg of lentiviral plasmids were mixed with 5 μl of Lipofectamine P3000 reagent (Invitrogen, 100022057) in 125 μl serum-free DMEM. The mixture was then combined with another 125 μl of serum-free DMEM containing 5 μl of Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, 100022050) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature before adding dropwise to the HEK293FT cells. Media change was performed on day 2. On day 3 and day 4, the virus-containing spent media was collected by filtering through a 0.45 μm sterile filter and stored at −80 °C until use.

For cell line transduction, 0.5 × 106 cells were plated in a 24-well plate (for K562 cells) or a 12-well plate (for HeLa cells) in 500 μl DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, TR-1003-G) and 200–300 μl of virus-containing media. Cells were spin-infected at 2,000g at 37 °C for 60 min. After overnight incubation, the infected cells were transferred to a 10 cm dish containing the fresh media supplemented with the corresponding antibiotics to start the selection. To generate the DKOs and corresponding controls, cells were first infected with plasmids bearing a hygromycin selection cassette, followed by 1 week of selection with 0.25 mg ml−1 hygromycin (Roche, 10843555001). After at least 1 day of recovery, the cells were infected again with plasmids bearing a puromycin selection cassette, followed by 3–5 days of selection with 2 μg ml−1 puromycin (Gibco, A1113803). Two cutting controls (OR2, OR11) were used as CRISPR KO controls. For SLC25A42 single KO with ectopic overexpression rescue cells, cells were first infected with overexpressing plasmids, followed by selection with 0.25 mg ml−1 hygromycin (Roche, 10843555001) for 1 week. EGFP was used as an overexpression control to account for effects of the hygromycin selection cassette. The cells were infected again with lentiCRISPR V2-puro with sgRNA targeting SLC25A42 or with sgRNA targeting OR2 as a cutting control, followed by 2 μg ml−1 puromycin (Gibco, A1113803) selection for 3–5 days. After the antibiotic selections, cells were allowed to recover in regular culture media for at least 1 day before performing the subsequent studies.

Cell proliferation assay

For K562 cells, 80,000 cells were seeded in a total volume of 1 ml DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin in 24-well plates in triplicate. For HeLa cells, 50,000 cells were seeded in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin in 12-well plates in triplicate. For delipidated culturing conditions, 10% FBS was replaced by 10% charcoal-stripped FBS (Gibco, A3382101). For antimycin treatment conditions, 100 nM antimycin (Sigma-Aldrich, A8674) was added to the culture media. Cell numbers upon seeding were measured again for normalization. Cells were counted and passaged every 3 days after seeding until day 6 or day 9.

Seahorse mitochondrial stress and FAO stress tests

The Seahorse mitochondrial stress and FAO stress tests were performed using a Seahorse XFe24 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies) with Seahorse Wave Desktop Software (v.2.6.1.56) (Agilent Technologies) and normalized with cell number (counted while seeding). For the mitochondrial stress test, one million K562 cells were counted and resuspended at a concentration of 2.5 million cells per ml in Seahorse assay media (Agilent, 103575-100). Then, 40 µl of cells (roughly 100,000 cells) were plated in each well of a Seahorse XFe24 culture plate that was pre-coated with Cell-Tak (Corning, 354240) working solution. Cellular oxygen consumption rate was measured using the Mito Stress Test Kit (Agilent Technologies, 103015) at the following drug concentrations: 1.5 µM oligomycin, 1 µM FCCP and a mixture of 0.5 µM rotenone and 0.5 µM antimycin. For the FAO assays, K562 cells were washed two times with Seahorse FAO assay media (Seahorse XF base medium with 5 mM HEPES (Agilent Technologies, 103575-100) supplemented with 0.5 µM l-carnitine (Sigma-Aldrich, C0283)). Roughly 100,000 cells were plated in Seahorse FAO assay media in each well that was pre-coated with 50 µg ml−1 poly-d-lysine (ThermoFisher, A3890401), followed by 200g centrifugation for 5 min for full adherence. Additional media, either supplemented with BSA or 167 μM palmitic acid conjugated to BSA (6:1 molar ratio), was gently added to each well to reach a final volume of 500 µl and incubated for 30 min before the assay. Cellular oxygen consumption rate was measured at the following drug concentrations: 1.5 µM oligomycin, 10 µM FCCP and a mixture of 0.5 µM rotenone and 0.5 µM antimycin.

Western blotting

For western blotting experiments, cells or immuno-isolated mitochondria were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, J60645.AK) supplemented with 1% SDS and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11836170001) and cleared with QIAshredder (QIAGEN, 79654). The protein concentration was measured with a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, 23225) for normalization. SDS–PAGE was performed using NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, NP0335BOX) or 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX, Stain-Free Protein Gel (Bio-Rad, P4568096), followed by PVDF membrane transfer using the Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system. Membranes were imaged on a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system. Antibodies and concentrations were used as follows: anti-VDAC (Cell Signaling Technology, 4661S, 1:1,000); anti-SHMT2 (Sigma-Aldrich, HPA-020549, 1:1,000); anti-GAPDH (Invitrogen, 39-8600, 1:1,000); anti-COASY (Santa Cruz, sc-393812, 1:200); anti-FLAG (GenScript, A00187, 1:1,000); anti-SLC25A42 (Atlas Antibodies, HPA049449, 1:1,000); anti-MYC rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling, 71D10, 2278S, 1:2,000); anti-FLAG rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling, 2368S, 1:2,000). Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody, HRP (Invitrogen, PI31460, 1:5,000); Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody, HRP (Invitrogen, PI31430, 1:5,000); and LI-COR secondary goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW antibody (926-32211, 1:10,000).

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence, roughly 50,000 HeLa cells ectopically overexpressing COASYα-FLAG were seeded on glass coverslips (12 mm round) in a 24-well plate 2 days before the experiment. Cells were fixed at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde (Invitrogen, FB002) for 15 min. After 3× PBS washing and 1 h room temperature incubation with blocking buffer (0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, 93443) and 5% (w/v) BSA (Fisher Scientific, BP1600) in PBS (Gibco, 10010023)), the fixed cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with anti-FLAG antibody (GenScript, A00187) at a 1:400 dilution. After blocking buffer washing (2×) and PBS washing (2×), the fixed cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with the goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 633 (Thermo Fisher, A-21050) at a 1:600 dilution. After washing four times as stated above, the fixed cells were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen, P36941) overnight. The confocal images were acquired the next day with an Andor Spinning Disk Confocal BC43 microscope (Oxford Instruments) at Yale West Campus imaging core.

[U-13C5]-glutamine stable isotope tracing assay

For the stable isotope tracing assay, 1 million K562 or 0.6 million HeLa cells were seeded 1 day before the experiment. The next day, cells are washed with PBS (1×) before changing to tracing media (DMEM with 10% dFBS, 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin and 2 mM [U-13C5]-glutamine (Med Chem Express, HY-N0390S1)). After a 2 h incubation, cells were washed with PBS (1×), followed by metabolite extraction with 500 μl 80% methanol at dry-ice temperature. The extracts were then incubated on dry ice for 5 min and wet ice for 10 min before centrifugation at 20,000g at 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatants were collected for LC–MS small polar metabolite profiling with the method stated below. Manual peak integration was performed using Skyline (MacCoss Lab, Skyline-daily 24.1.1.398)60. Naturally occurring 13C abundance was corrected using the R package ‘IsoCorrectoR’ (v.1.24.0)61 to obtain the corrected peak intensities and fractions.

Mitochondria immunoprecipitation

The rapid mitochondria immuno-isolation method was adapted from a previous protocol31,47,62. In brief, for K562 cells, roughly 40 million cells expressing 3×HA–EGFP–OMP25 (HA-MITO tag) were washed with room-temperature PBS, collected at 1,000g centrifugation for 2 min and resuspended with 1 ml ice-cold KPBS buffer (136 mM KCl, 10 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.25) before lysing. For HeLa cells, roughly 25 million cells were washed with room-temperature PBS before scraping and collecting in 1 ml ice-cold KPBS buffer. HA-MITO tagged cells in KPBS buffer were then mechanically lysed with 22 gentle strokes by a Dounce Tissue Grinder (DWK Life Sciences 8853000001). The lysates were then centrifuged at 1,000g for 2 min at 4 °C; mitochondria containing supernatants were transferred to 80 μl pre-washed magnetic anti-HA beads (Pierce, 88837) and incubated on an end-to-end rotator for 3.5 min at 4 °C. After washing with ice-cold KPBS three times, the isolated mitochondria were lysed for western blotting, aliquoted for mitochondria uptake assay or extracted for LC–MS metabolites analysis. Samples were stored at −80 °C if not immediately proceeding to subsequent analysis.

LC–MS-based Acyl-CoA profiling

For whole-cell acyl-CoA profiling, for K562 cells, roughly 40 million cells were pelleted at 1,000g for 2 min and immediately extracted without washing. For HeLa cells, roughly 25 million cells were immediately extracted without washing. The acyl-CoA extraction was performed by adding 2 ml dry-ice-cold 80% methanol, followed by a 60 s vigorous vortex. The extracts were treated with 1.2 ml of a dry-ice-cold methanol–NH4FA mixture (methanol, 200 mM ammonium formate; 2:1, v/v) followed by a 60 s vigorous vortex, and then incubated on dry ice for ~5 min and wet ice for ~10 min. The extracted metabolites were then centrifuged at 20,000g at 4 °C for 20 min, and the supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C.

The SPE protocol was adapted from a previous method46. Whole-cell acyl-CoA extracts were first acidified by 800 μl of glacial acetic acid and vortexed before SPE. The Supelco SPE column (Sigma-Aldrich, 54127-U) was first conditioned with 1 ml of condition buffer (acetonitrile/isopropanol/water/acetic acid, 9:3:4:4, v/v/v/v), loaded with the acidified acyl-CoA extracts, washed with 2 ml condition buffer and eluted with 1 ml elution buffer (methanol, 250 mM ammonium formate pH 7, 4:1, v/v).

For mitochondria acyl-CoA profiling, mitochondria were immuno-isolated from roughly 40 million K562 or 25 million HeLa cells using the method stated above. Mitochondrial acyl-CoAs were extracted with 50 μl of dry-ice-cold 80% followed by ~5 min dry ice incubation and ~10 min wet ice incubation, and then vortexed. Metabolite samples were stored at −80 °C if not immediately proceeding to LC–MS analysis.

The LC–MS analyses were performed on a Q Exactive Plus benchtop Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with an Ion Max source and a HESI II probe, coupled to a Vanquish UHPLC system. The LC gradient of acyl-CoAs was modified from a previous publication42 using an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (130 Å, 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters, 186002352). Mobile phase A consisted of 5 mM NH4FA pH 9 (adjusted with ammonium hydroxide), and mobile phase B consisted of 5 mM NH4FA, pH 9 and isopropanol (5:95, v/v). The column was maintained at 27 °C. The injection volume was 5 μl. Autosampler temperature was maintained at 6 °C. The LC conditions were set as follows: flow rate, 0.15 ml min−1 with a gradient of 2% B at 0 min, 2% B at 2 min, 40% B at 13 min, 40% B at 15 min, 98% B at 28 min, 98% B at 30 min, 2% B at 32 min and 2% B at 40 min. The mass data were acquired in positive ion mode with full scan acquisition over an m/z range of 650–1,200, at a resolution of 70,000, with an AGC target of 3 × 106, maximum injection time of 400 ms, sheath gas flow of 40 units, auxiliary gas flow of ten units, sweep gas flow of one unit, spray voltage of 4.0 kV, capillary temperature of 325 °C and auxiliary gas heater temperature of 300 °C.

The LC–MS/MS analysis of acyl-CoAs was performed using the same column and mobile gradients as mentioned above. Acyl-CoA standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (acetyl-CoA, A2181; malonyl-CoA, M4263; oleoyl-CoA, O1012; arachidonoyl-CoA, A5837). Mass data were acquired using targeted Selected Ion Monitoring mode at a resolution of 70,000, with an AGC target of 1 × 105, maximum injection time of 100 ms, loop count of five and isolation window of 2.0 m/z; and data-dependent MS/MS at a resolution of 17,500, AGC target of 1 × 105, maximum injection time of 100 ms, loop count of five, isolation window of 2.0 m/z and stepped normalized collision energies of 10, 35 and 50. MS/MS data were collected on species exceeding an intensity threshold of 8 × 103. Dynamic exclusion was set to 6.0 s.

The column requires priming with potassium phosphate monobasic buffer to mitigate the severe peak tailing of long-chain acyl-CoAs48. In brief, for priming, the column was disconnected from the mass spectrometer and flushed with 1 M phosphate and methanol (95:5, v/v) at 0.1 ml min−1 for 1–2 h. The column was then washed with water and acetonitrile (95:5, v/v) at 1.5 ml min−1 for 1–2 h, followed by a wash with acyl-CoA profiling mobile phase A and B (as stated above) with the following isocratic steps (20 min each): 2% B; 10% B; 20% B; 40% B; 60% B; 80% B; 98% B. The priming was performed roughly every 100 injections or whenever the long-chain peak shapes deteriorated.

LC–MS data were analysed using Xcalibur (v.4.1) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Compound Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

LC–MS-based cellular and mitochondrial small polar metabolite profiling

LC–MS-based polar metabolite profiling (untargeted) was performed following a previous method59 on a Q Exactive Plus benchtop Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with an Ion Max source and a HESI II probe, coupled to a Vanquish UHPLC system.

In brief, for whole-cell analyses, for K562 cells, roughly two million cells were collected, washed once with 1 ml ice-cold PBS before lysing with 500 μl acetonitrile/methanol/water (27:9:1 v/v/v). For HeLa cells, 0.6 million cells were seeded on a six-well plate on day 0. On day 1, cells were washed once with 1 ml ice-cold PBS before being extracted with 500 μl acetonitrile/methanol/water (27:9:1 v/v/v). The cellular extracts were then vortexed and centrifuged at 20,000g for 20 min at 4 °C, with the supernatant collected for subsequent LC–MS analyses. For mitochondrial metabolite profiling, roughly 40 million cells (K562) or 25 million cells (HeLa) were collected for mitochondria isolation using the method stated above. At the end of isolation, metabolites were extracted with 50 μl of 80% dry-ice-cold methanol, followed by ~5 min dry ice incubation and ~10 min wet ice incubation before removing the magnetic beads. The mitochondrial extracts were then vortexed and centrifuged at 20,000g for 20 min at 4 °C, with the supernatant collected for subsequent LC–MS analyses. Metabolite samples were stored at −80 °C if not immediately proceeding to LC–MS analysis.

Polar metabolite samples were analysed on a SeQuant ZIC-pHILIC polymeric 5 μm, 150 × 2.1 mm column (EMD-Millipore 150460). The column was maintained at 27 °C, and the autosampler was maintained at 6 °C. The sample injection volume was 5 μl. Mobile phase A consisted of 20 mM ammonium carbonate/ammonium hydroxide pH 9.6, and mobile phase B was 100% acetonitrile. LC gradients were set with a flow rate of 0.150 ml min−1 as follows: 0 min, 80% B; 0.5 min, 80% B; 20.5 min, 20% B; 21.5 min, 80% B; and 29 min, 80% B. The mass data were acquired in polarity switching mode with full scan acquisition over an m/z range of 70–1,000 at a resolution of 70,000, with an AGC target of 3 × 106, maximum injection time of 250 ms, sheath gas flow of 50 units, auxiliary gas flow of ten units, sweep gas flow of two units, spray voltage of 2.5 kV, capillary temperature of 310 °C and auxiliary gas heater temperature of 370 °C. Compound Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to pick peaks and integrate intensity from raw data. For whole-cell polar metabolite profiling, one quality control filter was applied: maximum coefficient of variation of the metabolite within quality control samples (s.d. / mean) < 0.3. The filtered metabolites were then annotated by searching against an in-house chemical standard library with 5 ppm mass accuracy and 0.5 min retention time windows, followed by manual curation. The data are presented as either annotated metabolites based on the in-house chemical standard library, or the untargeted analysis included all peaks quantified by Compound Discoverer.

The LC–MS/MS analysis for 3-HMG was performed using the same column and mobile gradients as mentioned above. The 3-HMG chemical standard was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (H4392). MS was acquired in polarity switching mode following the same parameters as above, except the maximum injection time was 100 ms. Data-dependent MS/MS spectra were acquired for the top five precursors from the MS scan at a resolution of 17,500, with an AGC target of 1 × 105, maximum injection time of 50 ms, loop count of five, isolation window of 2.0 m/z and stepped normalized collision energies of 10, 30 and 50. MS/MS spectra were collected on species with an intensity threshold of 8 × 103. Dynamic exclusion was set to 8.0 s.

The LC–MS/MS analyses for acylcarnitines were performed using the same column and mobile phase gradients as mentioned above. Acylcarnitine standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (palmitoyl-l-carnitine, 91503; myristoyl-l-carnitine, 91582; butyryl-l-carnitine, 42623). MS spectra were acquired in positive ion mode using a targeted acquisition method at a resolution of 70,000, with an AGC target of 5 × 104, maximum injection time of 100 ms, loop count of five and an isolation window of 4.0 m/z. Data-dependent MS/MS spectra were acquired at a resolution of 35,000, with an AGC target of 2 × 105, maximum injection time of 100 ms, loop count of five, isolation window of 3.0 m/z and stepped normalized collision energies of 15, 35 and 50. MS/MS spectra were collected on species exceeding an intensity threshold of 8 × 103. Dynamic exclusion was set to 5.0 s.

Generation of [13C3-15N1] stable-isotope-labelled acyl-CoAs

[13C3-15N1] stable-isotope-labelled acyl-CoAs (M+4) were produced with modifications from previous method32,50. In brief, roughly five million K562 cells were washed twice with PBS (Gibco, 10010023) before seeding into labelling media, which consisted of RPMI 1640 medium without pantothenic acid (US Biological Life Sciences, R8999-01A), 10% dFBS (Thermo Fisher, A3382001), 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, 15140122) and 1 mg l−1 [13C315N1]-pantothenate (Sigma-Aldrich, 705837). [13C315N1]-pantothenate was prepared in water at 1 g l−1 to make a 1,000× stock concentration and stored at −20 °C upon use. K562 cells were then labelled for 72 h, with a media change performed at 48 h. Upon collection, cells were extracted using the same method stated above, followed by SPE sample purification (see LC–MS-based acyl-CoA profiling). The SPE-purified M+4-labelled acyl-CoAs were nitrogen-dried into a pellet and stored at −20 °C (temporarily) or at −80 °C (long term) before being reconstituted with mitochondria assay buffer for the mitochondria uptake assay (see below).

Mitochondria uptake assay

Dried pellets of M+4-labelled acyl-CoAs were reconstituted with 200 μl or 300 μl assay buffer (110 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM KH2PO4, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% BSA) with final pH adjusted to 7.5 using KOH. The [(1,2-13C2)-acetyl]-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich, 658650) was prepared as a 5 mM stock solution in water, and finally diluted to 10 μM in the assay buffer. Both substrate solutions were freshly prepared immediately before the uptake assay. For mitochondria, roughly 75 million HA-MITO-tagged K562 cells were collected and immuno-isolated with 160 μl anti-HA beads using the method stated above. At the final KPBS wash, the isolated mitochondria on beads were equally aliquoted for triplicate samples. KPBS was then removed, and isolated mitochondria on beads were incubated with 50 μl substrates (self-reconstituted M+4 acyl-CoAs or 10 μM [(1,2-13C2)-acetyl]-CoA) at room temperature. The uptake was quenched at 6 min by directly adding 1 ml ice-cold KPBS, followed by washing with 1 ml ice-cold KPBS three times. The metabolites were extracted with 50 μl dry-ice-cold 80% methanol for subsequent LC–MS analysis. Then, 10 μl of the input substrate pool was extracted with 40 μl dry-ice-cold 100% methanol and quantified with LC–MS.

Yeast complementation analysis

Yeast cells were cultured in either yeast peptone dextrose medium (2% (w/v) peptone (Research Products International, P20250) and 1% (w/v) Bacto yeast extract (Gibco, 212750) supplemented with 2% (w/v) d-glucose (Research Products International, G32040)) or yeast peptone glycerol, in which 3% (v/v) glycerol (Research Products International, G22025) was used instead of glucose. Synthetic complete media were made of 0.67% (w/v) yeast nitrogen base (Research Products International, Y20040) and 2% (w/v) d-glucose, supplemented with auxotrophic requirements. For solid media, 2% (w/v) agar (Research Products International, A20030) was used. Transformation, sporulation, tetrad dissection and plasmid swapping on 5-fluoroorotic acid (Gold-Bio) synthetic complete medium were performed using standard methods. Yeast cells were grown at 30 °C and collected in early stationary growth phase (15–20 optical density units per ml). Yeast-related plasmid information is provided in the Supplementary information. Restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs, and the HiFi DNA Assembly method (NEBuilder, NEB) was used to construct expression vectors.

The leu5Δ/LEU5 heterozygous strain was generated from the wild-type diploid BY4743 strain63, in which the LEU5 gene was targeted with the natMX6 gene disruption cassette amplified from pAG25 plasmid following a previous protocol64 using the following PCR primers, and deletion was selected with nourseothricin (Gold-Bio, N500).

Sense primer:

ACCAGTGAAATTTCTCGAGGTAACTGCTAAAATAAACACAGTTCTTAAGTCAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC

Antisense primer:

AATAGACGGTTTCATTGCGATATGCAAATAAAACAAAATGCGATGCATAACGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG.

The leu5Δ [pTU-LEU5] haploid strain (leu5Δ strain expressing pTU-LEU5) was generated by transforming the leu5Δ/LEU5 strain with a single-copy plasmid (pTU-LEU5, CEN, URA3), inducing sporulation and isolating haploid progeny carrying the leu5Δ and pTU-LEU5 plasmid in the BY4741 background. For testing human CoA transporters, the leu5Δ [pTU-LEU5] strain was transformed with single-copy vector pTL (CEN, leucine selection) carrying yeast LEU5, human SLC25A42, SLC25A42N291D, SLC25A16 or empty vector (as a negative control). For testing human COASY, the leu5Δ [pTU-LEU5] strain was co-transformed with multi-copy vector pKG-GW3 (histidine selection) carrying human COASY, and MTS-COASY and pTL carrying LEU5 or empty vector.

Transformed yeast cells were streaked onto synthetic defined medium containing all amino acids, nucleotide supplements and 1% (w/v) 5-fluoroorotic acid (Gold-Bio). The plates were incubated for 3 days at 30 °C to lose the URA3 selection vector pTU-LEU5. Isolated cells lacking pTU-LEU5 were grown overnight in liquid synthetic medium and diluted to a final concentration of 0.8 optical density units per ml in water. Then, 3 μl of each suspension and three subsequent tenfold serial dilutions were spotted onto yeast peptone dextrose or yeast peptone glycerol agar plates for 3 days at 30 °C.

Yeast mitochondria isolation

Mitochondria were isolated as described previously65. In brief, cells cultured in synthetic complete medium at 30 °C were collected at early stationary growth phase (15–20 optical density units per ml). Upon washing, spheroplasts were obtained after Zymolyase 20T (Amsbio, 12049-1) digestion and disrupted with a Dounce homogenizer. Mitochondria were purified by differential centrifugation, in which the crude mitochondrial fraction pellet from a 10 min, 12,000g spin at 4 °C was then applied for a 1 h, 134,000g spin using a sucrose step gradient (15–23–32–60% sucrose, w/v). Total protein concentrations were quantified according to the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, 23225).

Statistics and reproducibility

For cell proliferation, metabolite profiling and Seahorse mitochondrial stress experiments, data are shown as means ± s.d. or as scatter plots with mean as indicated in each figure, with n ≥ 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance between two groups was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Statistical significance between multiple groups was calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by a post hoc test as indicated in each figure. The significance level is indicated in the figure captions. All experiments were validated at least two times with similar results. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (v.10.3.1), Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 365) or as reported by the relevant computational tools.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

COASY, SLC25A16 and SLC25A42 gene expression data are from the GTEx portal, GTEx analysis release V10 and dbGaP accession number phs000424.v10.p2. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Barritt, S. A., DuBois-Coyne, S. E. & Dibble, C. C. Coenzyme A biosynthesis: mechanisms of regulation, function and disease. Nat. Metab. 6, 1008–1023 (2024).

Trefely, S., Lovell, C. D., Snyder, N. W. & Wellen, K. E. Compartmentalised acyl-CoA metabolism and roles in chromatin regulation. Mol. Metab. 38, 100941 (2020).

Naquet, P., Kerr, E. W., Vickers, S. D. & Leonardi, R. Regulation of coenzyme A levels by degradation: the ‘Ins and Outs’. Prog. Lipid Res. 78, 101028 (2020).

Shi, L. & Tu, B. P. Acetyl-CoA and the regulation of metabolism: mechanisms and consequences. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 33, 125–131 (2015).

Idell-Wenger, J. A., Grotyohann, L. W. & Neely, J. R. Coenzyme A and carnitine distribution in normal and ischemic hearts. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 4310–4318 (1978).

Garland, P. B., Shepherd, D. & Yates, D. W. Steady-state concentrations of coenzyme A, acetyl-coenzyme A and long-chain fatty acyl-coenzyme A in rat-liver mitochondria oxidizing palmitate. Biochem. J. 97, 587–594 (1965).

Van Broekhoven, A., Peeters, M.-C., Debeer, L. J. & Mannaerts, G. P. Subcellular distribution of coenzyme A: evidence for a separate coenzyme A pool in peroxisomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 100, 305–312 (1981).

Robishaw, J. D., Berkich, D. & Neely, J. R. Rate-limiting step and control of coenzyme A synthesis in cardiac muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 10967–10972 (1982).

Daugherty, M. et al. Complete reconstitution of the human coenzyme A biosynthetic pathway via comparative genomics. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 21431–21439 (2002).

Skrede, S. & Halvorsen, O. Mitochondrial biosynthesis of coenzyme A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 91, 1536–1542 (1979).

Tahiliani, A. G. & Neely, J. R. Mitochondrial synthesis of coenzyme A is on the external surface. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 19, 1161–1167 (1987).

Zhyvoloup, A. et al. Subcellular localization and regulation of coenzyme A synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50316–50321 (2003).

Nemazanyy, I. et al. Identification of a novel CoA synthase isoform, which is primarily expressed in the brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341, 995–1000 (2006).

Rhee, H.-W. et al. Proteomic mapping of mitochondria in living cells via spatially restricted enzymatic tagging. Science 339, 1328–1331 (2013).