Abstract

Single-cell multiomics provides critical insights into how disease-associated variants identified through genome-wide association studies (GWASs) influence transcription factor eRegulons within a specific cellular context; however, the regulatory roles of genetic variants in aging and disease remain unclear. Here, we present scMORE, a method that integrates single-cell transcriptomes and chromatin accessibility with GWAS summary statistics to identify cell-type-specific eRegulons associated with diseases. scMORE effectively captures trait-relevant cellular features and demonstrates robust performance across simulated and real single-cell datasets, and GWASs for 31 immune- and aging-related traits, including Parkinson’s disease (PD). In the human midbrain, scMORE identifies 77 aging-relevant eRegulons implicated in PD across seven brain cell types and reveals sex-dependent dysregulation of these eRegulons in PD neurons compared to both young and aged groups. By linking genetic variation to cell type-resolved eRegulon activity, scMORE illuminates how variants shape trait-relevant regulatory networks and provides a practical framework for mechanistic interpretation of GWAS signals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

GWASs have identified thousands of genetic variants associated with complex diseases over the past decades1,2,3; however, most of these variants reside in noncoding regulatory regions, complicating functional interpretation due to the cell type-specific nature of gene regulation4. Recent advances in single-cell sequencing technologies have provided unprecedented multimodal views at the cellular level, enabling the identification of disease-relevant core gene regulatory networks5. Integrating GWAS signals with single-cell data offers a powerful approach for elucidating the functional organization of master regulators within specific cellular contexts relevant to complex diseases6,7,8.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dissects cellular heterogeneity and disease processes9,10,11,12. Complementing scRNA-seq, single-cell sequencing assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (scATAC-seq) maps chromatin accessibility to reveal regulatory elements and transcription factor (TF)-mediated gene programs13,14,15,16. Recent single-cell multiomics enables simultaneous measurement of transcriptomes and epigenomes within the same cell, providing fine-grained views of transcriptional control and cis-regulatory element activity5,17,18. Several tools7,15,19,20,21 infer gene regulatory networks (GRNs) or enhancer-driven regulons (eRegulons) from these data; however, these approaches generally lack a statistical framework to quantify the genetic control of regulons in a cell type-specific manner.

In parallel, recent methods8,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 integrate GWAS summary statistics with single-cell data to prioritize disease-relevant cell types and states. For example, we and others developed scPagwas22, scBPS23 and scDRS24, which incorporate polygenic signals with scRNA-seq to pinpoint trait-relevant cell subpopulations and cellular states. Additionally, SCAVENGE29 employs network propagation to couple GWAS with scATAC-seq data, revealing disease-associated cell states and trajectories. Complementary efforts31,32,33 have constructed cell type-specific enhancer-gene maps using diverse strategies, including correlating enhancer activity with gene expression, integrating enhancer activity with the probability of physical contact to target genes, and combining multiple linking approaches into composite scores derived from bulk or single-cell data. Collectively, these advances demonstrate the promise of integrating GWAS signals with single-cell multiomics for charting disease-relevant cellular contexts, while highlighting the need for frameworks that operate at the regulon level (inferring TF–peak (enhancer)–target links and testing their polygenic enrichment to identify phenotype-relevant eRegulons in specific cellular contexts).

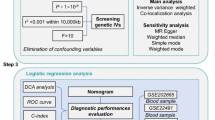

Here, we present scMORE (single-cell MultiOmics Regulon Enrichment), a network-based polygenic enrichment method that integrates single-cell multiomics and GWAS data to identify cell type-specific eRegulons relevant to complex diseases. scMORE first constructs a global TF–peak–target regulatory network using a generalized linear regression model (GLM), then infers cell type-specific eRegulons via a modified cosine similarity approach. Polygenic signals are mapped to peak–gene pairs and combined with cell type-specificity to generate trait-relevant regulon scores, with significance assessed by Monte-Carlo (MC)-derived empirical P values. Across simulated and real single-cell datasets, scMORE outperforms existing approaches. We applied scMORE to 31 immune- and aging-related traits using extensive single-cell multiomic data and GWAS results, with a particular focus on PD. We also introduce scHOB (https://schob.su-lab.org/), a user-friendly portal for curated scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets from various human organoids. By leveraging organoid-based single-cell multiomics, scMORE identifies cell type-specific eRegulons associated with eight psychiatric disorders.

Results

Overview of scMORE

Multiple lines of evidence4,24,25,27,30,34 have shown significant enrichment of polygenic signals from GWAS in genes with higher cell type-specific expression within disease-relevant cell types. Building on this principle and applying it to single-cell multiomic data, we hypothesize that if GWAS-identified disease-associated genes are concordantly activated within a cell type-specific TF-mediated eRegulon, the eRegulon is likely critical for complex diseases in that specific cellular context. To address the current gap in linking polygenic GWAS signals to cell type-specific eRegulons, we developed scMORE. The primary objective of scMORE is to compute a trait-associated regulon score (TRS) for each eRegulon in a given cell type. The framework comprises four key steps: (1) constructing a multimodal TF-mediated GRN; (2) inferring cell type-specific TF-eRegulons; (3) linking GWAS genetic signals to target genes through peak-level regulatory annotations; and (4) integrating genetic relevance and cell type specificity (CTS) into a unified TRS, followed by empirical assessment through MC sampling (Fig. 1a–f).

a, Utilizing single-cell multimodal measurements to construct a global TF-GRN based on a GLM. b, A modified cosine similarity method is applied to infer the specificity score of each TF and its target genes (CTS) within a sub-GRN (eRegulon) in a specific cell type. c, Genetic association signals from GWAS summary statistics are mapped to peaks (PR), linked to corresponding genes (PS) and disease-specific genes (GS) are identified using MAGMA or FUMA gene-scoring methods. The GRS for each node is calculated as the product of GS, PR and PS, representing the genetic correlation of the node with the trait. d, The TRS is calculated for each eRegulon in a particular cell type by integrating the GRS and CTS scores. The s.d. term is included as a penalty to control the deviation between GWAS signals and gene expression. e, MC Model: 1,000 sets of matched control eRegulons are generated for each eRegulon in a given cell type. MC sampling is then used to calculate a P value for each eRegulon based on the empirical distribution. f, scMORE outputs. The outputs include (1) TRS, GRS and CTS values for each eRegulon associated with a specific disease in a given cell type; (2) MC-based empirical P values for each eRegulon within the specific cellular context.

First, scMORE integrates multimodal single-cell measurements to construct a TF-GRN using a GLM model15 by default (Fig. 1a). To quantify CTS, scMORE employs a modified cosine similarity approach. Cosine similarity, which measures the orientations of two n-dimensional vectors in a scale-independent manner, is robust to technical variations such as sequencing depth difference35,36,37,38,39. scMORE applies this method to calculate a specificity score for each node (TF or gene) within a given eRegulon in a specific cell type (Fig. 1b). Compared to six commonly used methods (for example, a Wilcoxon test, logistic regression and Student’s t-test), scMORE’s cosine similarity approach outperformed them in identifying cell type-specific genes in a brain single-cell multiomic dataset40 (Extended Data Fig. 1). The CTS score of each eRegulon is calculated by collapsing the specificity scores of its TF and target genes, with a penalty factor \(\theta\) (\(\theta\) = 0.5 by default) applied to emphasize the importance of the TF.

To evaluate the relevance of regulatory regions to the trait of interest, scMORE links GWAS single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to peak regions and calculates a peak relevance (PR) score based on the most significant SNP association by default. Alternatively, fine-mapped SNPs with high posterior probabilities can be incorporated to refine SNP-peak associations (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). The regulatory importance of each peak is quantified via peak strength (PS), defined as the strength of correlation between the peak and its associated gene, computed using linear regression. In parallel, the gene-level association score (GS) of each target gene is derived using MAGMA41 by default. These three components (GS, PR and PS) are combined to form a genetic relevance score (GRS) for each node, reflecting its overall contribution to the trait (Fig. 1c). As with CTS, the GRS of an eRegulon is computed by aggregating the GRS values of its TF and target genes, with the same penalty factor applied.

Building on previous work30, scMORE defines a TRS for each eRegulon in a given cell type by integrating GRS and CTS scores using the following formulation: \(\mathrm{TRS}=\mathrm{GRS}+\mathrm{CTS}-{\rm{s}}.{\rm{d}}.(\mathrm{GRS},\mathrm{CTS})\), where the s.d. term controls for deviations between genetic relevance and CTS, ensuring that the TRS is not dominated by either GWAS or single-cell data alone (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2). To assess statistical significance, scMORE generates 1,000 matched controls for each eRegulon in a given cell type and applies MC sampling to compute empirical P values based on the null distributions of these matched controls (Fig. 1e). To ensure comparability of relevance scores across traits and cell types, TRS, GRS and CTS values are scaled using z-score transformation.

The inputs to scMORE include single-cell transcriptional profiles, chromatin accessibility readouts and GWAS summary statistics (for either quantitative traits or case–control phenotypes). The output includes TRS, GRS and CTS values for each eRegulon associated with the trait of interest in a given cell type, along with the corresponding MC-based empirical P values (Fig. 1f).

Assessing scMORE in identifying immune-specific eRegulons for hematological traits

To evaluate the efficacy of scMORE, we utilized a GWAS summary dataset on lymphocyte count (n = 171,643 samples; Supplementary Table 1)42, a highly heritable hematological trait, and integrated it with a ground-truth single-cell multiomic dataset derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 2). Our analysis identified four significant eRegulons (ZEB1, IKZF1, FOXO1 and ZNF721) that were specifically associated with the lymphocyte count trait in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, no significant eRegulons were identified in monocyte cells, as determined by stringent significance threshold for TRS, GRS and CTS scores (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PCTS < 0.05; Fig. 2c). Additionally, these four significant eRegulons demonstrated markedly higher regulon activity in CD8+ T cells compared to monocytes, emphasizing their cell type-specific relevance (Fig. 2d). Among these, three eRegulons (ZEB1, IKZF1 and FOXO1) were also significantly associated with lymphocyte percent trait (n = 171,748 samples)42, which serves as an independent hematological measure of lymphocyte characteristics (Fig. 2e). For lymphocytes, FOXO1 is essential for promoting the formation of memory T cells, which possess the ability to self-renew and expand upon antigenic stimulation43,44. It also serves as a master regulator of memory programming in CAR T cells45. Similarly, IKZF1 plays pivotal roles at various stages of lymphocyte development and hematopoiesis46.

a, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot showing the cellular composition of a ground-truth single-cell multiomic dataset (monocytes, n = 1,000 cells and CD8+ T cells, n = 1,000 cells). b, Scatter-plot of scMORE-identified eRegulons associated with the lymphocyte count trait in CD8+ T cells. Each dot represents an eRegulon, with the -log-transformed GRS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the y axis and the −log-transformed CTS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the x axis. Gray dots indicate nonsignificant eRegulons and red dots represent significant eRegulons. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). c, Scatter-plot of scMORE-identified eRegulons relevant to the lymphocyte count trait in monocytes. No significant eRegulons were identified. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). d, Illustration of the performance of scMORE in identifying lymphocyte count trait-relevant eRegulons. Four lymphocyte count trait-relevant eRegulons exhibited stronger regulon activity scores in CD8+ T cells compared to monocytes. e, Heatmap displaying the TRSs of four significant eRegulons for both lymphocyte count and lymphocyte percent traits across monocytes and CD8+ T cells. The heatmap was generated using the pheatmap R package based on TRSs. The color bar represents TRS magnitude. **Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PTRS < 0.01; *Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PTRS < 0.05. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). f, Two-sided Pearson correlation of TRSs between lymphocyte count and lymphocyte percent, stratified by CD8+ T cells and monocytes. g, Benchmarking analysis comparing the performance of scMORE’s cosine specificity method with the averaged gene expression method. The E-statistics for each trait was calculated using getEnergyScore() function in scMORE. Each dot in boxplot indicates a blood trait. The two-sided paired Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance (n = 10 blood traits). Boxplot shows the median (center line), interquartile range (IQR; box) and 1.5 × IQR bounds (whiskers). Minima and maxima are represented by the whiskers.

Furthermore, three additional significant eRegulons (ETS1, LEF1 and FOXP1) were specifically associated with the lymphocyte percent trait (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PCTS < 0.05; Extended Data Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Table 4). These three eRegulons also exhibited suggestive associations with lymphocyte count trait (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.1 and PCTS < 0.05; Extended Data Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 3). FOXP1 mediates TGF-β-driven transcriptional repression in CD8+ T cells and suppresses antitumor T cell effector functions in tumor microenvironment47. Both ETS1 and LEF1 contribute to T cell activation and survival48,49. Notably, we observed a strong positive correlation between the TRS scores of eRegulons analyzed for lymphocyte count and lymphocyte percent traits in CD8+ T cells (r = 0.993, P = 2.3 × 10−70; Fig. 2f), which was higher than the correlation observed in monocytes (r = 0.846, P = 7.4 × 10−22). In an independent PBMC multiome dataset50, all seven CD8+ T cell-type-specific eRegulons associated with both lymphocyte traits remained significant or suggestive, confirming the reproducibility and robustness of the scMORE (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Table 2).

To assess biological relevance, we examined the overlap between lymphocyte-associated GWAS loci and scMORE-identified eRegulons. Across the seven significant eRegulons, 63 TFs or targets harbored one or more genome-wide significant (GWS) SNPs for both lymphocyte traits (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Five master TFs contained GWS SNPs for two traits (Supplementary Table 5); for example, IKZF1 harbored seven SNPs for lymphocyte count (for example, rs62447181, P = 4.014 × 10−10; rs6971716, P = 1.124 × 10−10) and three for lymphocyte percent (for example, rs149007767, P = 2.82 × 10−14). FOXO1 included five SNPs for lymphocyte count (for example, rs61954176, P = 1.214 × 10−9; rs537744482, P = 2.98 × 10−13) and one SNP for lymphocyte percent (for example, rs7323267, P = 2.07 × 10−10). Consistently, these core eRegulons were enriched for lymphocyte-associated genes from the OpenTargets (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Transcriptome-wide association analyses (TWAS)51 identified 17 TFs or targets (including IKZF1 and FOXO1) whose genetically predicted expression associated with lymphocyte traits (Extended Data Fig. 3e). As an orthogonal validation, we applied pgBoost52 to the PBMC dataset with cell-type stratification for both lymphocyte traits and found that pgBoost-prioritized target genes converged on the same eRegulons highlighted by scMORE (Supplementary Tables 6 and7 and Supplementary Notes). A PubMed scan using RISmed22 also supported these links: scMORE-identified result is significantly correlated with literature evidence (r = 0.24, P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 3a,b), exceeding correlations derived from matched random controls (permuted P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 3c,d).

To further validate the performance of scMORE, we conducted a similar analysis by integrating the same ground-truth single-cell dataset with GWAS summary statistics for additional eight blood cell traits (Supplementary Table 1). As expected, scMORE effectively identified cell type-specific eRegulons that were significantly associated with hematological traits (Supplementary Fig. 4). Unlike traditional methods53,54,55,56 that calculate gene specificity by averaging the expression levels of individual genes, scMORE utilizes the cosine similarity algorithm to determine the CTS of each TF and its target genes within a given eRegulon across all cells, effectively mitigating sparsity in single-cell data (Supplementary Fig. 5). Inspired by a previous study57, we employed energy statistics (E-statistics) to measure the separation of inferred relevance scores of eRegulons between different cell types. Higher E-statistic values reflect an improved capacity to identify cell type-specific eRegulons associated with traits of interest (Methods). Our analysis revealed that the cosine similarity-based scMORE approach significantly outperformed the averaged gene expression-based method53,54,55,56 in identifying cell type-specific eRegulons relevant to ten blood cell traits (OR = 1.21, P = 1.13 × 10−6; Fig. 2g and Supplementary Table 8).

Benchmarking the scMORE

Accurate detection of disease-relevant eRegulons hinges on robust GRN inference15,20. We systematically benchmarked the performance of the GLM in scMORE against two alternative methods: the regularized linear model (GLMNET) and the gradient-boosted Random Forest regression model (XGBoost). Using cosine similarity, scMORE with the GLM model consistently outperformed the other two approaches in identifying hematological trait-relevant eRegulons (OR = 1.14–1.15, paired t-test P < 0.002; Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 9). With the averaged-expression approach, the three models were indistinguishable (P > 0.05). Although GLM-based approach inferred fewer eRegulons across varying cell counts from five tissues, its associations with ten hematological traits were more conserved than those from the other models (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). The seven eRegulons linked to both lymphocyte traits remained significant or suggestive under GLMNET and XGBoost (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.1 and PCTS < 0.05; Fig. 3b), with similar concordance across eight additional hematological traits (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 6c–f). Accordingly, scMORE default to GLM for inferring TF–gene interactions due to its performance and computational efficiency, while also supporting GLMNET and XGBoost as alternatives.

a, Benchmarking analysis of three GRN inference methods (GLM, XGBoost and GLMNET) for scMORE across 10 hematological traits in the ground-truth dataset. Both cosine similarity and averaged gene expression methods were evaluated for each GRN method. A two-sided paired Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance (n = 10 blood traits). Each dot in boxplot indicates a blood trait. Boxplot inside the violin plot shows the median (center line), IQR (box) and 1.5 × IQR bounds (whiskers). Minima and maxima are represented by the whiskers. b. Consistent identification of seven eRegulons relevant to lymphocyte count and percent across the three GRN inference methods. **Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PTRS < 0.01. *Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PTRS < 0.05. #Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.1 and PTRS < 0.05. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). c, Two-sided Pearson correlation analysis of TRSs between scMORE-based GLM and GLMNET, as well as XGBoost. d, Benchmarking analysis of scMORE’s cosine specificity performance compared to averaged gene expression and MAGMA_Cell-typing-based gene specificity across ten hematological traits using five immune single-cell multiomic datasets. These datasets included varying cell counts (1 K, n = 1,222 cells; 3 K, n = 2,722 cells; 5 K, n = 5,174 cells; 7 K, n = 7,304 cells; 9 K, n = 8,900 cells), spanning seven cell types (monocytes, mDCs, pDCs, B cells, NK cells, CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells). The E-statistics for each trait was calculated using the getEnergyScore() function in scMORE. Boxplot shows the median (center line), IQR (box) and 1.5 × IQR bounds (whiskers). Minima and maxima are represented by the whiskers. Each dot in boxplot indicates a blood trait (n = 10 blood traits).

Moreover, we probed parameter sensitivity under two peak-to-gene linking strategies (Signac16 and GREAT58). Varying peak-centered buffer sizes across ten blood traits, cosine-based scMORE consistently produced higher E-statistics than the averaged-expression method (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b); a buffer size of 500 bp was both high-performing and stable, so we set it as default. We next varied \(\theta\), which adjusts the relative contribution of target gene specificity and genetic relevance within a given eRegulon. Across all ten traits and both linking strategies, cosine-based scMORE outperformed the averaged-expression method for every tested \(\theta\), with larger \(\theta\) yielding higher E-statistics (Supplementary Fig. 7c,d). We adopted \(\theta\) = 0.5 as a robust default to emphasize TF influence. Performance was concordant between Signac and GREAT regardless of buffer or \(\theta\) (r = 0.88-0.89, P < 1 × 10−46; Extended Data Fig. 4a,b); unless noted, scMORE defaults to Signac-based linking strategy due to its broad use in single-cell analysis.

To assess the effect of \(\omega\), which penalizes off-target expression, E-statistics increased monotonically with \(\omega\) (Extended Data Fig. 4c), improving prioritization of cell-type-specific genes; however, overly large values can over-penalize biologically relevant genes with moderate off-target expression, so we set \(\omega =1\) as the default. Null simulations using synthetic GWAS data confirmed the robustness of scMORE (Extended Data Fig. 4d), and causal simulations with cell-type-restricted upregulation further showed high sensitivity in detecting biologically relevant regulatory signals (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

We next compared scMORE with MAGMA_Celltyping27 across five single-cell datasets (1K–9K cells) for ten blood traits. By E-statistics, cosine-based scMORE consistently outperformed MAGMA_Celltyping’s gene-specificity method, better distinguishing cell type-specific trait-relevant eRegulons (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 8). We further tested five alternative gene-scoring methods (FUSION59, S-PrediXcan60, S-MultiXcan51, SMR61 and fastBAT62) on the same datasets; beyond the default MAGMA implementation, scMORE again prioritized trait-relevant eRegulons, with particularly strong performance using S-MultiXcan51 and SMR61 (Supplementary Fig. 9). In 21 additional immune- and aging-related diseases from tissue-derived single-cell multiomics, scMORE also exceeded the two gene-specificity methods in immune/blood cell types (OR = 1.262–1.263, paired t-test P < 5 × 10−6; Supplementary Fig. 10a and Supplementary Table 10), human midbrain cell types (OR = 1.274–1.297, paired t-test P < 5 × 10−9; Supplementary Fig. 10b and Supplementary Table 11) and organoid-based cerebral cell types (OR = 1.32–1.34, paired t-test P < 5 × 10−6; Supplementary Fig. 10c and Supplementary Table 12).

To assess the determinants of eRegulon detection by scMORE, we found that datasets with larger cell numbers, greater cell-type diversity and larger GWAS sample sizes consistently yielded more eRegulons (Extended Data Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 10d and Supplementary Notes). While more than the default 1,000 iterations improved P value resolution, results from the 1,000 iterations were highly concordant with those from 10,000 and 100,000 iterations (Supplementary Fig. 11). By default, scMORE restricts analysis to scATAC-seq peaks intersecting with conserved elements and excludes exonic regions (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). Additionally, scMORE displays high computational efficiency, with runtime and memory usage scaling linearly with cell number (Supplementary Fig. 14). Collectively, these findings demonstrate the robustness and scalability of scMORE in uncovering trait-relevant eRegulons across complex cellular contexts.

scMORE identifies immune cell type-specific eRegulons for autoimmune diseases

To investigate shared regulatory architecture in autoimmunity, we integrated a PBMC single-cell multiomic dataset (n = 8,900 cells; Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 2) with GWAS for five autoimmune diseases: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE; n = 5,201 cases and 14,267 controls)63, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; n = 12,882 cases and 21,770 controls)64, rheumatoid arthritis (RA; n = 14,361 cases and 42,923 controls)65, ulcerative colitis (UC; n = 6,968 cases and 20,464 controls)64 and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC; n = 2,764 cases and 10,475 controls; Supplementary Table 1)66. Using linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC)67, we estimated pairwise genetic correlations and quantified locus overlap, revealing strong shared genetic architecture across these diseases (Extended Data Fig. 6).

a, UMAP embedding of seven immune cell types from a single-cell multiomic dataset. The dataset includes monocytes (n = 3,313 cells), CD4+ T cells (n = 2,283 cells), CD8+ T cells (n = 997 cells), NK (n = 1,130 cells), mDC (n = 101 cells) and pDC (n = 121 cells). b, Proportion of autoimmune disease-associated eRegulons in each immune cell type. c, Heatmap illustrating scMORE-identified cell type-specific eRegulons associated with five autoimmune diseases across seven immune cell types. **Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05, PTRS < 0.05 and TRS > 3. *Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05, PTRS < 0.05 and TRS > 1.5. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). d, Scatter-plots highlighting significant eRegulons associated with IBD in CD8+ T cells, RA in CD4+ T cells, SLE in monocytes and UC in mDCs. Each dot indicates an eRegulon, with the −log-transformed GRS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the y axis and the −log-transformed CTS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the x axis. Gray dots represent nonsignificant eRegulons, while red dots indicate significant eRegulons. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). e, The UMAP visualization of 3,313 monocyte cells, highlighting two subtypes: CD14+ and FCGR3A+ monocytes. f, Feature plot displaying the expression of two marker genes. g, Heatmap showing scMORE-identified monocyte subtype-specific eRegulons associated with five autoimmune diseases. The color bar represents the TRS of each eRegulon, and * denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PTRS < 0.05. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). h, TRS distributions for four eRegulon-disease pairs (HES5-IBD, KLF4-RA, BCL11B-SLE and UBTF-UC) across 50 monocyte cell states. Color bar indicates the TRS of each eRegulon.

Applying scMORE, we identified 26 eRegulons (≥20 genes) significantly associated with at least one disease across seven immune cell types (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PCTS < 0.05; Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 13). Of these, 15 were in lymphocytes (CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs)), and eight were in myeloid cells (monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs); Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 15). Lymphocyte-specific STAT4 and ETS1 eRegulons were associated with RA, IBD and UC. High ETS1 expression in lymphocytes has been previously linked to RA68 and IBD69. Monocyte/mDC-specific JUN and FOS eRegulons exhibited associations with SLE, RA, IBD and UC (empirical P < 0.05; Fig. 4c). These shared eRegulons may reflect inherent lineage similarities between two cell types. For example, the FOXO1 eRegulon was significant for all five autoimmune diseases in two lymphocyte types (CD8+ and CD4+ T cells) (Fig. 4d); FOXO1 promotes lymphocyte activation and proliferation70, and its transcriptional dysregulation of FOXO1 implicated in RA pathogenesis71,72,73. Likewise, the SPI1 eRegulon was significantly associated with SLE, UC, RA and IBD in two myeloid cell types (monocytes and mDCs) but not in other cell types. SPI1, also known as PU.1, has been linked to SLE74 and IBD75.

Among these 26 significant eRegulons, 15 TFs harbored GWS variants at least one autoimmune disease and 46 targets contained GWS variants (Supplementary Fig. 16a,b and Supplementary Table 14). Notably, ETS1 and IKZF3 mapped to all five autoimmune diseases (Supplementary Fig. 16c,d), consistent with scMORE’s shared-eRegulon signals. Examples include GWS SNPs mapping to ETS1 for IBD (rs7933433, P = 1.0 × 10−10), PBC (rs10893872, P = 1.0 × 10−8), RA (rs10556591, P = 1.46 × 10−11) and SLE (rs1128334, P = 3.0 × 10−33); and IKZF3 SNPs for IBD (rs2872507, P = 4.51 × 10−40), PBC (rs71152606, P = 8.0 × 10−44), RA (rs35736272, P = 6 × 10−30), SLE (rs8067378, P = 5.0 × 10−23) and UC (rs35736272, P = 6.0 × 10−30). TWAS with S-MultiXcan51 identified 19 autoimmune disease-risk genes within these eRegulons showing significantly predicted expression changes (Supplementary Fig. 17), including seven master regulators, further supporting their regulatory roles.

Given considerable heterogeneity within cell types4,29, we further evaluated scMORE’s capacity to detect cell state-specific eRegulons in a phenotypically rich manner. To this end, we re-clustered monocytes into CD14+ and FCGR3A+ subtypes using canonical markers (Fig. 4e,f), and tested genetic enrichment for the five autoimmune diseases. 12 disease-relevant eRegulons exhibited distinct enrichment patterns (Fig. 4g). Of them, five eRegulons (for example, KLF4, ETV6 and UBTF) were significantly enriched in both subtypes, whereas seven (for example, HES4, BCL11B and HMGB1) were subtype-specific, indicating lineage-linked regulation. To refine this analysis, we further defined 50 monocyte states based on pseudotimes generated by Slingshot76 (Supplementary Fig. 18a,b). scMORE revealed dynamic regulon enrichment across states (Fig. 4h). For example, the IBD-relevant HES4 eRegulon predominanted in FCGR3A+ states, whereas the RA-associated KLF4 eRegulon was broadly enriched. Functional analyses showed that HES4 targets were enriched for non-classical monocyte functions, including positive regulation of cytokine production, positive regulation of MAPK cascade and chemokine production (Supplementary Fig. 18c), whereas KLF4 targets highlighted general immune activation, including leukocyte proliferation, B cell activation and regulation of lymphocyte activation (Supplementary Fig. 18d). Together, these results demonstrate that scMORE resolves disease-associated eRegulons at both cell-type and cell-state levels, providing mechanistic insights into the transcriptional architecture of autoimmune diseases.

scMORE identifies aging-relevant eRegulons involved in Parkinson’s disease

PD is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder77. Although many genetic risk loci for PD have been reported78,79,80,81, how genetic variants regulate PD (especially in the aging midbrain) remains unclear. Recent single-cell studies chart midbrain cellular heterogeneity in aging and PD82,83,84, but a genetics-informed, regulon-level analysis has been lacking. To address this, we employed scMORE to integrate single-nuclei paired multimodal measurements from human midbrain (n = 58,949 cells)82 with PD GWAS summary statistics80 (n = 33,674 cases and 449,056 controls, Supplementary Table 1). This single-cell multimodal dataset includes seven cell types: oligodendrocytes (ODCs), oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), microglia (MG), astrocytes (ASs), endothelial cells (ECs), neurons (Ns) and peripheral T cells (Ts), derived from 9 young donors, 8 aged donors and 14 patients with PD across male and female individuals (Fig. 5a–c and Supplementary Fig. 19a,b).

a, UMAP visualization of single nuclei, colored by cell types. b, UMAP plot of single nuclei, colored by three groups (young, aged and PD). c, UMAP plot of single nuclei, colored by sex (male (M) and female (F)). d, Cell proportions of seven brain cell types across the three groups, stratified by sex. Cell composition of seven cell types across different group × sex categories (top). Spearman correlation (two-sided) between the proportion of each cell type and donor age (n = 31) (bottom). Only cell types corresponding to FDR-adjusted P < 0.05 are marked by an asterisk. e, Distribution of eRegulon sizes identified by scMORE in a human midbrain single-cell multiomic dataset. Among these detected eRegulons, 74.13% contain 20 or more genes. f, Heatmap illustrating the top-ranked PD-associated eRegulons identified by scMORE across seven brain cell types. **Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05, PTRS < 0.05 and TRS > 3. *Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05, PTRS < 0.05 and TRS > 1.5. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). g, Proportion of PD-associated eRegulons in each brain cell type. h, Scatter-plots demonstrating significant eRegulons associated with PD in ASs and OPCs. Each dot represents an eRegulon, with −log-transformed GRS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the y axis and −log-transformed CTS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the x axis. Gray dots denote nonsignificant eRegulons, and red dots indicate significant eRegulons. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). i, Representative examples showing differential eRegulon activity across the young (n = 9), aged (n = 8) and PD groups (n = 14). A two-sided Wilcoxon test was used to assess statistical significance. Boxplot shows the median (center line), IQR (box) and 1.5 × IQR bounds (whiskers). Minima and maxima are represented by the whiskers. Outliers are shown as individual points. j, Regulatory network of PD-associated genes in the ZFPM2-eRegulon that harbors strong genetic signals (SNPs and corresponding P values from GWAS summary data; no multiple correction). k, Functional enrichment analysis of the ZFPM2-eRegulon. Pathway enrichment results from Metascape (top) and Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process (BP) term enrichment results from WebGestlat (bottom).

After sex stratification, ODCs represented the most abundant midbrain cell type, followed by MG, OPCs, ASs, Ns and Ts (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 19c). ODCs, MGs, ASs and ECs differed in proportions between patients with PD and the other two groups (Supplementary Fig. 19d), consistent with previous findings82,83. Sex-specific analyses showed age-related shifts in OPCs and MGs in at least one sex, indicating sex-dependent aging effects (Supplementary Fig. 20). Proportions correlated with age in males for OPCs, ASs, Ns and ECs, and in females for ODCs, MG, Ns and ECs (Fig. 5d). Notably, Ns displayed distinct aging-associated patterns in both sexes (Fig. 5d).

Of the 286 eRegulons, 74.13% (comprising 20 or more genes) were retained for downstream analyses (Fig. 5e). Among 1,484 qualified cell type–eRegulon pairs, 273 (18.4%) showed significant associations with PD (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PCTS < 0.05; Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 21a,b). Notably, two immune-related cell types (Ts and MGs) exhibited similar association patterns compared to other brain cell types. By cell type, ASs (21.98%) and OPCs (14.29%) had the highest proportions of significant PD-associated eRegulons (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PCTS < 0.05; Fig. 5g). For instance, ZFPM2, ZNF536 and PRDM16 were significantly enriched in ASs, whereas ZNF462, SOX6 and CCDC88A were enriched in OPCs (Fig. 5h). Genes critical to ASs and OPCs function have been implicated causally in PD85,86. As orthogonal support, we employed pgBoost52 to the midbrain dataset with cell-type stratification for PD and observed that pgBoost variant-to-gene links mapping to genes clustering within scMORE-identified PD-relevant eRegulons (Supplementary Table 15). Additionally, 58.3% of eRegulons contained more than 30 reported PD-related hits based on RISmed-based PubMed scan (Supplementary Fig. 22).

To assess aging contributions, we integrated the midbrain single-cell multimodal data with GWAS for seven aging-related traits (Table 1), including healthspan (n = 300,477)87, parental lifespan (n = 570,798)88, frailty (n = 175,226)89, epigenetic age acceleration (EAA; n = 34,710)90, extreme longevity (90th percentile, n = 36,345; and 99th percentile, n = 28,967)91 and the common factor multivariate longevity (mvAge; n = 1,958,774)92. Using stringent criteria, we defined aging-relevant eRegulons as those significant for all seven traits. Among these aging-relevant eRegulons, 77 were also significantly associated with PD, including ZFPM2, ZEB1, MEF2C, SOX6, NFATC2 and CCDC88A (Extended Data Fig. 7a), suggesting a potential core set of regulators linking aging and neurodegeneration. Differential regulon activity (DRA) analyses across three groups (young, aged and PD) further revealed that these aging-relevant eRegulons contribute to PD risk (Fig. 5i and Extended Data Fig. 7b). For example, ZFPM2, PRDM16 and RFX4 in ASs; and ZFPM2, SOX6 and CCDC88A in OPCs exhibited significantly abnormal regulon activity in patients with PD compared to either the young or aged groups.

To further prioritize trait-relevant eRegulons, we assessed their overlap with top PD GWAS loci80,93. We identified 24 PD risk genes, including LRRK2, P2RY12, SYBU, TMEM163 and IGSF9B, harboring 35 GWS lead SNPs (for example, rs76904798, P = 1.52 × 10−28, and rs34637584, P = 3.6 × 10−148, in LRRK2; rs57891859, P = 4.55 × 10−14, in TMEM163; and rs3802920, P = 6.26 × 10−20, rs11223628, P = 2.20 × 10−14, in IGSF9B) (Supplementary Table 16). Several of these genes, including TMEM163, LRRK2 and SH3GL2, also showed genetically predicted expression associated with PD by S-MultiXcan51 (Supplementary Table 17). Based on biological relevance and therapeutic potential, we prioritized four representative eRegulons, ZFPM2, ZEB1, MEF2C and NFATC2 (Fig. 5j,k and Supplementary Fig. 23a–c). The ZFPM2-eRegulon encompassed 16 risk genes (for example, TMEM163, SYBU, RIMS1, SH3GL2 and KCND3) with 23 lead SNPs (for example, SH3GL2: rs13294100, rs10756907, rs8180177 and rs1536072), and was enriched in ASs and OPCs (Fig. 5j). Its target genes were significantly enriched in neurodevelopmental and synaptic pathways, including neuron differentiation, brain development and synapse organization (Fig. 5k). The MEF2C and NFATC2 eRegulons included eight PD risk genes (for example, LRRK2, FCGR2A, SIPA1L2 and MED12L), and were highly enriched in Ts and MGs (two immune cell types critical in neurodegeneration). Their target genes were significantly associated with immune activation, cell adhesion and MAPK signaling (Supplementary Fig. 23b). As an orthogonal validation, PD-relevant genes prioritized by the OpenTargets platform94 were significantly or suggestively enriched across all four key eRegulons (Supplementary Fig. 23c).

To evaluate the therapeutic relevance, we performed drug-gene interaction analysis using the DGIdb database (https://dgidb.org/). This analysis revealed hub genes within each core eRegulon that are targeted by multiple FDA-approved drugs (Supplementary Figs. 24a,b and 25a,b). For example, in the ZFPM2-eRegulon: ADRA1A, ALDH1A1, EGFR and VEGFA; In the ZEB1-eRegulon: MAOB, GRIN2B, CACNA1D and APOE; In MEF2C and NFAT2C eRegulons: IL1B, PPARG, CSF1R and P2RY12. Notably, MAOB, a key target within ZEB1-eRegulon, is targeted by several antiparkinson agents, including selegiline, rasagiline, safinamide and levodopa (Supplementary Fig. 25a). ALDH1A1 also interacts with approved PD drugs such as pramipexole, ropinirole, carbidopa anhydrous, rotigotine, cabergoline, pergolide and apomorphine (Supplementary Fig. 24a). These results underscore these eRegulons as actionable targets for PD intervention.

Given that sex-dependent aging-related patterns in Ns (Fig. 5d), we dissected neuron-specific regulation. We identified 22 aging-relevant eRegulons significantly associated with PD in Ns (Fig. 6a). Sex-stratified scMORE analyses showed that the overall disease relevance was consistent between sexes, with all 22 aging-relevant eRegulons remaining significant in both male and female cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 25c). Notably, DRA analyses revealed altered activity of eRegulons such as BCL11A, ZEB1 and DMBX1 in patients with PD (Fig. 6b). When stratified by sex, these eRegulons displayed divergent trajectories (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 26). For instance, in males, BCL11A, ZEB1, DMBX1 and CUX2 exhibited a biphasic pattern, decreasing from young to aged, followed by reactivation in PD. In contrast, females exhibited a progressive increase across aging and PD (Fig. 6d). BCL11A, a core SWI/SNF component, governs neuronal fate during cortical and spinal cord development95; its haploinsufficiency causes neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders96 and defines dopaminergic neuron subtypes with distinct projection patterns and vulnerability to neurodegeneration97. Functional enrichment of BCL11A-targeted genes highlighted pathways related to synaptic signaling, neuron projection development and neurotransmitter transport (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05; Fig. 6e). Two members, PTPRN2 and NOL4, harbor PD GWS SNPs (rs80148128 and rs2076574176; Fig. 6f), and PTPRN2 shows sex-specific epigenetic regulation in cortical neurons related to PD98. The ZEB1-eRegulon also exhibited neuron-specific activity and contained multiple PD risk genes (for example, IGSF9B, RBMS3, NOL4, PTPRN2 and DSCAM; Fig. 6f); its targets were enriched for neuronal morphogenesis, synaptic signaling and calcium signaling (Supplementary Fig. 23a). Overall, scMORE pinpoints aging-relevant eRegulons implicated in PD, illuminating interactions among aging, sex and cell type-specific regulatory programs.

a, Scatter-plot showing 22 aging-relevant eRegulons significantly associated with PD in neurons (Ns). Each dot represents an eRegulon, with the −log-transformed GRS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the y axis and the −log-transformed CTS P values (−log10(P)) shown on the x axis. Gray dots denote nonsignificant eRegulons, while red dots indicate significant eRegulons. The 22 aging-relevant eRegulons are highlighted in the boxed area. b, Representative examples exhibiting differential activity of three aging-related eRegulons across the young (n = 9), aged (n = 8) and PD groups (n = 14). A two-sided Wilcoxon test was used to assess statistical significance. Boxplot shows the median (center line), IQR (box) and 1.5 × IQR bounds (whiskers). Minima and maxima are represented by the whiskers. Outliers are shown as individual points. c, Heatmap displaying the top-ranked PD-associated eRegulons identified by scMORE across seven brain cell types. d, Representative examples of differential activity of four aging-relevant eRegulons across the young (n = 9), aged (n = 8) and PD groups (n = 14), stratified by sex (male: n = 21; female: n = 10). The two-sided Wilcoxon test was used to assess statistical significance. Boxplot shows the median (center line), IQR (box) and 1.5 × IQR bounds (whiskers). Minima and maxima are represented by the whiskers. Outliers are shown as individual points. e, Functional enrichment analyses of the BCL11A-eRegulon (n = 46 genes) based on GO BP using WebGestalt. f, Regulatory network of the BCL11A and ZEB1 eRegulons that contain PD-associated genes and risk SNPs (SNPs and corresponding P values from GWAS summary data; no multiple correction).

scMORE identifies key eRegulons associated with psychiatric disorders

Human organoids are advanced 3D models that recapitulate key features of human development and function10. Unlike two-dimensional cultures, they enable study of complex cellular interactions15. To address the lack of a unified organoid-based single-cell multiomic resource, we present single-cell Human Organoid Bank (scHOB), a curated repository integrating scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets from ten widely used human organoids. This current release contains over 1.5 million cells spanning 67 major cell types, 385 samples and 83 distinct experimental protocols (Fig. 7a, Extended Data Fig. 8, Supplementary Fig. 27 and Supplementary Table 18). The scHOB portal (https://schob.su-lab.org/) provides an intuitive interface to browse, query, analyze and visualize single-cell multimodal data, with filtering by organoid type, protocol and accession metadata (Supplementary Figs. 28 and 29). Three advanced search modes and four core functional modules support functional enrichment, intercellular communication, chromatin co-accessibility and cell type-specific gene–drug interaction analyses (Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Notes).

a, Schematic representation of the scHOB database. scHOB curates and integrates data from over 1.5 million cells derived from various human organoids and their corresponding fetal tissues, including 83.4% scRNA-seq cells and 16.6% scATAC-seq cells. Example analysis was performed to demonstrate the utility of scMORE in identifying critical eRegulons associated with eight psychiatric disorders within organoid-based single-cell data. b, Distribution of regulon sizes identified by scMORE in human cerebral organoid single-cell multiomic data. Among these detected eRegulons, 71.66% consist of 20 or more genes. c, Heatmap illustrating scMORE-identified key eRegulons associated with eight psychiatric disorders across five brain cell types, categorized as three groups: glutamatergic neurons, GABAergic neurons and non-neuronal cells. **Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05, PTRS < 0.05 and TRS > 3. *Denotes PCTS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05, PTRS < 0.05 and TRS > 1.5. Significance was assessed by an MC permutation test (one-sided, upper tail; n = 1,000 iterations; no multiple correction). d, Network visualization of disease-eRegulon associations within specific cellular contexts. This network-based analysis illustrates interactions between TF-eRegulons and psychiatric disorders in a cell type-specific manner. Diamonds represent psychiatric disorders (colored by cell type) and circles denote TF-eRegulons. e, Seven psychiatric disorder-specific eRegulons shared between glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons. f, Regulatory network of a representative eRegulon (FOXP2) that harbors strong genetic signals. Triangle denotes TF, diamonds represent psychiatric disorders, purple circles indicate target genes harboring GWAS loci, and light purple circles indicate risk SNPs. g, Functional enrichment analysis of the FOXP2-eRegulon based on GO BP using WebGestalt.

To demonstrate scMORE on organoid data, we integrated human cerebral organoid single-cell multiomic data with GWAS summary statistics for eight neuropsychiatric disorders (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 1): schizophrenia (SCZ; n = 52,017 cases and 75,889 controls)99, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; n = 38,691 cases and 186,843 controls)100, autism spectrum disorder (ASD; n = 18,382 cases and 27,969 controls)101, major depressive disorder (MDD; n = 59,851 cases and 113,154 controls)102, bipolar disorder (BIP; n = 41,917 cases and 371,549 controls)103, anorexia nervosa (AN; n = 16,992 cases and 55,525 controls)104, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; n = 2,688 cases and 7,037 controls)105 and Tourette syndrome (TS; n = 4,819 cases and 9,488 controls)106. This multiomic dataset comprised five major brain cell types: excitatory neuron (ExN; n = 6,294 cells), inhibitory neuron (InN; n = 12,570 cells), microglia (MG; n = 3,164 cells), astrocyte (AS; n = 2,122 cells) and radial glia (RG; n = 1,082 cells; Supplementary Table 19). scMORE-inferred 187 eRegulons; 71.66% contained ≥ 20 genes and were utilized for downstream analyses (Fig. 7b).

Of these, 58 eRegulons exhibited significant associations with one or more neuropsychiatric disorders across the five brain cell types (PTRS < 0.05, PGRS < 0.05 and PCTS < 0.05; Fig. 7c). Examples include 18 ExN-specific eRegulons (for example, NEUROD6, NEUROD2 and MEF2C) and 17 InN-specific eRegulons (for example, ZEB2, TSHZ2 and DLX1) (Supplementary Fig. 30), consistent with previous reports of ExN/InN specificity107,108. A total of 14 significant eRegulons (for example, GLI3, NFE2L2 and SOX3) were specific to non-neuronal cells (MG, AS and RG), recapitulating inherent cellular similarities among glial cells. Notably, HES5 was exclusive to RG, aligning with a previous study109. Overall, 77.59% of significant eRegulons were linked to at least three psychiatric disorders, with ExN-specific eRegulons exhibiting the most associations (Supplementary Fig. 30). In-depth network analysis revealed that cell type-resolved connectivity between key eRegulons and disorders (Fig. 7d and Supplementary Table 20), and seven significant eRegulons (HMGB2, RFX7, TCF7L2, MEIS2, EBF1, PAX6 and ZFHX3) with critical biological functions were shared by glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons (Fig. 7e and Supplementary Fig. 31).

As the eight psychiatric disorders are highly genetically correlated (Extended Data Fig. 10a), we tested whether these pleiotropic eRegulons include TFs or targets harboring GWS SNPs. In total, 26 TFs or targets harbored GWS loci for one or more disorders (Extended Data Fig. 10b). Of note, ten master regulators of shared eRegulons, including FOXP2, SOX5, EBF1 and MEF2C, contained GWS SNPs in large psychiatric GWASs (Extended Data Fig. 10c and Supplementary Table 21). For example, FOXP2 associated with ADHD (rs8180817, P = 6.0 ×10−21; rs1476535, P = 3.0×10−26), MDD (rs8180817, P = 2.0 × 10−11; rs2894699, P = 4.0 × 10−9) and SCZ (rs7783012, P = 1.0 × 10−9) (Fig. 7f). FOXP2 encodes a forkhead box TF essential for brain development and language regions; its eRegulon was enriched for forebrain development, regulation of developmental growth and cognition (Fig. 7g and Extended Data Fig. 10d).

We further leveraged S-MultiXcan51 to integrate GTEx eQTL data110 with GWAS summary statistics across the eight psychiatric disorders, identifying risk genes with genetically predicted expression changes. Multiple top GWAS genes within scMORE-significant eRegulons showed strong associations, including FOXP2 (P = 8.08 × 10−10 for ADHD), CCDC39 (P = 6.19 × 10−13 for SCZ), MDK (P = 5.05 × 10−14 for SCZ), BCL11A (P = 1.87 × 10−8 for SCZ), CLIC1 (P = 1.07 × 10−27 for SCZ), CAMKV (P = 1.8 × 10−8 for ADHD) and ANK3 (P = 3.75 × 10−9 for BIP). Six of these genes, FOXP2, MEF2C, NPAS3, TSHZ2, ZEB2 and DLX1, are also master regulators of disease-relevant eRegulons and exhibited robust predicted expression differences (Extended Data Fig. 10e and Supplementary Fig. 32). Collectively, these results demonstrate that scMORE captures key regulatory programs implicated in psychiatric disorders across organoid cellular contexts.

Discussion

In this study, we introduce a network-based polygenic enrichment method (scMORE) designed to uncover cell type-specific TF-regulatory gene programs associated with complex diseases. scMORE integrates scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data with GWAS summary statistics, outperforming previous state-of-the-art methods when benchmarked across extensive single-cell multiomic datasets. Unlike earlier gene-set scoring methods111, scMORE captures essential trait-relevant features of single-cell data and links genetic association signals to the cellular context, thereby revealing critical disease-associated eRegulons. Notably, scMORE not only identifies trait-relevant eRegulons specific in predefined cell types but also pinpoints cell subtype- and state-specific eRegulons associated with the trait of interest, allowing for a more fine-grained dissection of the regulatory mechanisms underlying complex diseases.

Phenotypes of complex biological systems arise from multiscale mechanisms112. Compared to bulk platforms, single-cell multiomics quantifies molecular traits within individual cells across regulatory layers, encompassing transcriptomes and chromatin accessibility17,18. Joint analysis of these multimodal single-cell measurements requires linking cis-regulatory elements to their target genes to elucidate how regulation shapes functional gene modules31,32,33. Genetic association signals (especially those dispersed across interactive networks or of modest effect) are also key to decoding the genetic architecture of complex diseases and traits22. By leveraging these network-based advantages, scMORE enables the recapitulation of well-established cell type-specific eRegulon-disease associations while also uncovering biologically plausible enrichments that have yet to be documented in existing literature. Single-cell data are highly sparse and noisy29,113. Cosine similarity, which measures the angular relationship between vectors, is robust to sequencing depth and other technical variations35,36,37,38,39. scMORE uses a modified cosine similarity approach to compute the CTS score of each eRegulon across cells, reducing sparsity relative to methods that rely solely on gene expression abundance.

Recently, pgBoost52 was introduced as an integrative framework that learns a nonlinear combination of SNP–gene linking features (including genomic distance) from single-cell multiomic data, trained on eQTL data, to improve variant-gene assignment. In contrast, scMORE is a polygenic enrichment framework that integrates single-cell multiomics with GWAS to prioritize phenotype-relevant, cell-type-specific regulatory programs, yielding mechanistic insight and nominating druggable hubs. Applied to 31 immune- and aging-related traits, scMORE’s significant eRegulons were further prioritized by overlap with top GWAS loci, TWAS and literature-driven evidence using OpenTargets and RISmed, highlighting core eRegulons with stronger biological relevance and therapeutic potential.

For PD, we prioritized four core aging-relevant eRegulons (ZFPM2, ZEB1, MEF2C and NFATC2). ZFPM2 harbors a common variant (rs12678719) linked to antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism and nigrostriatal deficits in PD114. Its targets (TMEM163,SYBU,RIMS1,SH3GL2and KCND3) are enriched for neuron differentiation, brain development and synapse organization. ZEB1 has been implicated in neuroinflammation via effects on immune cell morphology and signaling, with emerging roles in central nervous system disorders115 and Alzheimer’s disease116. MEF2C and NFATC2 eRegulons were specific in T cells and microglia and enriched in immune activation and inflammatory signaling. MEF2C is central to the MEF2C–PGC1α regulatory axis, a proposed therapeutic target in PD due to its role in neuronal metabolism and neuroprotection117. Notably, MEF2C is also a downstream effector of LRRK2, a major PD-associated gene. In rodent models, LRRK2 promotes microglial neurotoxicity by phosphorylating NFATC2, promoting nuclear translocation and triggering proinflammatory gene programs118, with elevated NFATC2 activity observed in PD brains118,119. Thus, the LRRK2–NFATC2 pathway represents a plausible immunomodulatory target for PD. Drug-gene interaction analyses further highlighted critical genes within these eRegulons targeted by multiple US Food and Drug Administration-approved antiparkinsonian drugs (for example, MAOB and ALDH1A1), suggesting immediate translational relevance. Moreover, we observed sex-dependent dysregulation of these aging-relevant eRegulons in PD neurons, potentially contributing to sex-specific disease manifestations. Collectively, these findings underscore the relevance of aging-regulatory programs in PD and provide hypothesis-generating insights that warrant future experimental validation.

Moreover, we introduce scHOB, a web-accessible, interactive database that curates and analyzes single-cell multiomic data from human organoids. Unlike OrganoidDB120, which focuses mainly on bulk and single-cell transcriptomes, scHOB employs two unified pipelines to process and integrate both single-cell transcriptomic and chromatin accessibility data. This uniformed integration enables the effective reuse of human organoid datasets to investigate cellular diversification and the regulatory networks underlying key developmental transitions and disease-relevant features21,121. scHOB offers an easy-to-use interface to browse single-cell transcriptomic and chromatin accessibility profiles, and run comparisons with human primary tissues. This assists researchers in exploring molecular and cellular differences without computational expertise. With an effective data storage architecture, scHOB supports rapid query responses, facilitating experimental follow-up and validation. We provide several use cases to illustrate functionality and practical applications, underscoring scHOB’s potential to advance organoid research.

Limitations of the study

Several limitations warrant consideration. First, scMORE identifies disease-relevant eRegulons but does not establish causality; at best, it may highlight putative causal links, consistent with previous studies22,24,29,122. For each eRegulon, empirical P values are derived via MC permutation against 1,000 size-matched random eRegulons to generate null distributions for TRS, GRS and CTS; because the null is eRegulon-specific, these P values are intrinsically calibrated. Following permutation-based studies24,29,30, we used a conservative rule and deemed an eRegulon biologically relevant only when all three metrics satisfied empirical P < 0.05. Second, by default, scMORE maps SNPs to genes using a proximal distance window of 10 kb, analog to earlier studies22,53. Alternative SNP-to-gene approaches, such as Activity-By-Contact models and enhancer-gene linking strategies from Roadmap, can be substituted to fit specific aims32. Third, for compatibility with Seurat56 and Signac16, scMORE currently constructs TF-GRNs with Pando15, though other frameworks (for example, SCENIC+(ref. 20) and LINGER21) can be used for particular applications. Finally, the present scHOB release includes only scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq; future updates will incorporate additional layers (for example, DNA methylation: snmC-seq, sci-MET; epitopes: CITE-seq) and broaden metadata coverage. We welcome feedback via e-mail and plan to extend scHOB to drug-processed and CRISPR-perturbed organoid single-cell datasets to enable drug target discovery and assess perturbation effects on lineage development and differentiation.

Conclusion

In summary, scMORE shows promise in capturing essential disease-relevant eRegulons from single-cell multiomic data at the cell-type level. Through its network-based polygenic enrichment framework, scMORE enables discovery of critical eRegulons with biologically plausible links to complex traits and diseases. We also present scHOB, a comprehensive single-cell multiomic resource with versatile functionalities for organoid research community. Identifying reproducible, trait-relevant eRegulons in defined cellular contexts is a key step toward elucidating the regulatory mechanism of complex diseases and advancing precision medicine.

Methods

Ethical statement

This study complies with all relevant ethical regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki. Analyses were performed exclusively on publicly available single-cell multiomic datasets and GWAS summary statistics. No new human or animal participants were recruited and no identifiable private information was accessed. Ethics approval and written informed consent were obtained by the original studies.

scMORE methodology

In brief, scMORE (single cell MultiOmics Regulon Enrichment) employs a network-based polygenic enrichment framework to assess the association between TF-eRegulons and complex diseases or traits in a cell type-specific manner. scMORE includes four main steps. (1) Constructing a global TF-GRN from multimodal single-cell data by using a GLM model (via the stats R package)15. Alternatively, scMORE supports other inference methods, including GLMNET (via the glmnet package) and gradient boosting regression (via the XGBoost package). For peak-to-gene mapping, scMORE offers two strategies: Signac16 (default) and GREAT58. (2) Identifying cell type-specific eRegulons using a modified cosine similarity approach. (3) Linking GWAS SNPs to target genes using snp2peak() function. By default, the relevance of each peak to a trait is determined by its most significantly associated SNP. (4) Calculating a TRS for each eRegulon by combining its genetic association and cell type-specificity, followed by MC sampling to assess statistical significance. The overall computational workflow of scMORE is illustrated in Fig. 1. Detailed methods are described in the following steps.

Notation summary

To improve clarity, we summarized key notations used throughout this study. Let \(p\) denotes a peak region, \(u\) an SNP, i a gene, \(f\) a TF, \({r}_{k}\) an eRegulon, \({c}_{j}\) a single cell and \({C}_{m}\) a predefined cell type. For example, \({p}_{u}\) represents a peak \(p\) that contains SNP \(u\), and \({g}_{{i}_{u}}\) indicates a gene i containing SNP \(u\). The parameter \(\tau\) represents the fitted regulatory coefficient. We defined the following constants: \(G\) is the total number of genes and TFs across all inferred eRegulons, \(K\) indicates the total number of inferred eRegulons, \(N\) is the total number of cells and \(M\) indicates the total number of predefined cell types.

Gene and TF expression in a given cell \({c}_{j}\) are denoted as \({e}_{i,\,j}\) and \({e}_{f,j}\), respectively. \({\lambda }_{m}\) represents an ideal marker specifically expressed in cell type \({C}_{m}\). We further define the following scores: \(\mathrm{P{R}}_{u,p}\) indicates the relevance of peak \(p\) to a trait based on its most significantly associated SNP u, \({\mathrm{PS}}_{p,i}\) indicates the strength of correlation between peak \(p\) and gene i, \({\mathrm{GS}}_{i}\) indicates the gene-level association score for gene i, \({\mathrm{CTS}}_{i,m}\) indicates the CTS of gene i in cell type \({C}_{m}\), \({\mathrm{CTS}}_{k,m}\) indicates the cell type specificity of eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) in cell type \({C}_{m}\), \({\mathrm{GRS}}_{i,m}\) represents GRS for gene i in cell type \({C}_{m}\), \({\mathrm{GRS}}_{k,m}\) represents GRS for eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) in cell type \({C}_{m}\), \({\mathrm{TRS}}_{k,m}\) denotes TRS for each eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) in cell type \({C}_{m}\). Finally, scMORE includes two tunable penalty parameters, \(\theta\) and \(\omega\), which refine the contribution of genetic relevance and cell type specificity when computing TRS (Supplementary Notes).

Mapping SNPs to candidate regulatory regions

Previous studies15,123,124 have demonstrated that sequence conservation is a stronger indicator for regulatory function. Accordingly, scMORE by default leverages scATAC-seq peaks intersected with PhastCons conserved elements derived from the 30-mammal alignment125, while excluding exons (often conserved for coding rather than regulatory reasons). We also incorporate ENCODE candidate cis-regulatory elements (cCREs) that overlap peaks126. This default filter preferentially enriches for evolutionarily conserved, functionally relevant regulatory modules, and can be customized as needed for specific applications.

To assess each peak’s contribution to a trait, GWAS SNPs are assigned to their corresponding peaks using the snp2peak() function in scMORE, with a default window size of 1 kb (buffer = 500 bp). If an SNP maps to multiple peaks, we create independent SNP–region pairs, following previous work22,127. For a given region p with U SNPs assigned (\(u\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,U\,\}\)), the PR to the trait is determined by default based on the most significant SNP association, calculated as:\({\mathrm{PR}}_{u,p}=\mathop{\max }\limits_{\tilde{u}\in U}(-{\log }_{10}(P\_{\mathrm{value}}_{{p}_{\tilde{u}}}))\), where the notation \({p}_{u}\) is used to represent a peak p containing an SNP u. Alternatively, users may choose to use fine-mapped SNPs with high posterior probabilities to refine this linkage128 (Supplementary Notes).

Linking TF motif positions in candidate regulatory regions

Since TFs act via sequence-specific DNA binding, the availability of binding motifs is essential for including TFs in the regulatory network7,15,20. scMORE scans accessible chromatin for motif instances using the extended motif collection in Pando15 together with FindMotifs() function in Signac16. As an alternative option, the GREAT method58 can be used for linking peak-overlapping motif regions to nearby genes. This extended motif collection integrates binding motifs from multiple sources, including JASPAR129, which comprises both CORE and UNAVLIDATED collections, and the CIS-BP database130. For TFs lacking motifs in these sources, motifs were predicted by protein-sequence similarity within the same TF family, using family information and protein sequences from AnimalTFDB131. Where available, experimentally supported motifs were prioritized, followed by those inferred from other JASPAR motifs, and finally, motifs inferred solely from sequence similarity. In total, 1,372 TFs and their motifs were consolidated into a unified collection for downstream analyses.

Constructing TF-eRegulons using multimodal single-cell measurements

Single-cell data are sparse and noisy at the per-gene level, hindering GRN inference15,19. To mitigate this, scMORE uses a coarse-graining approach via pseudocell121. Closely related cells are clustered into ‘territories’ centered on randomly selected seed cells, determined by their ten nearest neighbors based on Euclidean distances in the top 20 principal components. If a cell falls into multiple territories, one is selected at random. For each territory, gene expression is aggregated by the arithmetic mean. For chromatin accessibility, binarized read counts are averaged to obtain accessibility probabilities. Peak counts are then transformed with latent semantic indexing (LSI) using RunTFIDF() and RunSVD() functions in Signac16, followed by high-resolution Louvain clustering on the top 20 LSI components. Accessibility probabilities are finally averaged at the cluster level, and each cell in a cluster is represented by the single shared vector.

To construct TF-GRNs, scMORE integrates paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data with a GLM framework as implemented in Pando15. Gene coordinates are retrieved from EnsDb.Hsapiens.v86 R package. Following previous work7,15,20, each gene’s cis-regulatory region is defined as the gene body plus 100 kb upstream of the transcription start site (TSS), which reduces noise from distal elements and prioritize proximal regulation. The log-normalized expression \({e}_{i}\) of gene i modeled as a function of all TF–binding-site pairs within its cis-regulatory window, can be written as:\({e}_{i}={\sum }_{f}{\tau }_{f\,}{e}_{f\,}{\alpha }_{f}+\varepsilon\), where \({e}_{f}\) is the log-normalized expression of TF \(f\), \({\alpha }_{f}\) is the accessibility probability of the peak overlapping its binding site, \(\tau\) is the fitted coefficient representing the regulatory effect and \(\varepsilon\) is the intercept. These fitted coefficients quantify the contribution of TF–peak pairs to the expression activity of target genes.

After model fitting, the resulting network is pruned to retain only TF–peak–target triplets that are significant by analysis of variance with multiple testing controlled by Benjamini–Hochberg (FDR < 0.05). The significance of the regulatory association between peak p and gene i is quantified as the PS, calculated as \({\mathrm{PS}}_{p,i}=-{\log }_{10}(P\_{\mathrm{value}}_{p,i})\). This score reflects the importance of the TF-binding peak in regulating the target’s expression. In scMORE, an eRegulon is defined as a set of target genes whose expression is significantly associated with the accessibility of TF’s binding sites within the 100-kb cis-regulatory window. To mitigate over-dispersion in smaller sets132, scMORE uses a default minimum of 20 genes per eRegulon.

Calculating genetic relevance scores of nodes in each eRegulon

After identifying TF-eRegulons, scMORE computes a GRS for each node, which include TF–peak and peak–gene associations. GRS measures the genetic contribution of each node to the trait of interest. Inspired by a previous study21, the GRS for each node is defined as follows:

where \({\mathrm{PR}}_{p,i}\) represents the relevance of the peak to the trait, \({\mathrm{PS}}_{p,i}\) denotes the strength of the correlation between the peak and the gene (as previously described) and \({\mathrm{GS}}_{i}\) corresponds to the gene-level genetic association, quantifying the degree of association between the gene and the trait.

To compute the trait-specific GS, scMORE supports gene-level association results derived from two alternative tools: MAGMA41 and FUMA133. By default, a 10-kb window centered on the TSS is used to assign GWAS SNPs to their associated genes. The GS for a gene \({g}_{i}\) is defined as: \({\mathrm{GS}}_{i}=-\,\log (P\_{\mathrm{value}}_{{g}_{i}})\). If an SNP maps to multiple genes, it is duplicated and treated as independent SNP–gene pairs.

Computing cell type specificity scores of nodes in each eRegulon

To identify TFs and targets specific to a cellular context, scMORE employs a cosine similarity approach to calculate the CTS for nodes within each eRegulon. Traditional approaches rely on statistical tests to identify differentially expressed genes between the cell type of interest and multiple other cell types56, which often prioritize broad group differences rather than true specificity134. Cosine similarity compares the orientation of n-dimensional vectors135, is independent of expression scale and robust to technical variation (for example, sequencing depth)38,135, and is widely used for cell–cell similarity36,37,39 and batch-effect assessment35.

In brief, the normalized gene expression matrix \(E\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{G\times N}\) is generated as input for getSpecificity() function in scMORE, where \(G\) is the number of genes and TFs in all inferred eRegulons and \(N\) is the number of cells. Let \(M\) indicates the number of cell types that are predefined by users. The expression of gene \({g}_{i}\) among all cells is denoted as \({{\boldsymbol{g}}}_{i}=[{e}_{1,i},{e}_{2,i},{e}_{3,i},\ldots ,{e}_{N,i}]\), where \({e}_{j,i}\) indicates the expression value of \({g}_{i}\) in a given cell \({c}_{j}\) (\(j\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,N\}\)). To calculate the specificity of genes for each cell type \({C}_{m}\), \(m\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,M\}\), we initially select an ideal marker gene \({\lambda }_{m}\) for \({C}_{m}\) that is denoted as \({{\boldsymbol{\lambda }}}_{m}=[{\lambda }_{1,m},{\lambda }_{2,m},{\lambda }_{3,m},\ldots ,{\lambda }_{N,m}]\), where \({\lambda }_{j,m}=1\) if \({c}_{j}\in {C}_{m}\) and \({\lambda }_{j,m}=0\) if \({c}_{j}\notin {C}_{m}\). The ideal marker \({\lambda }_{m}\) only expresses in the given cell type \({C}_{m}\) and does not show any expressions in other cell types \({C}_{t}\) (\(t\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,M\}\backslash \{m\}\)). The cosine similarity between \({g}_{i}\) and \({\lambda }_{{\rm{m}}}\) is calculated as follows:

Then, scMORE calculates the specificity score \(CT{S}_{i,m}\) of gene \({g}_{i}\) for a given cell type \({C}_{m}\) as:

where the left term \(\cos ({{\boldsymbol{g}}}_{i},{{\boldsymbol{\lambda }}}_{m})\) indicates the cosine similarity between gene \({g}_{i}\) and ideal marker \({\lambda }_{m}\) by assessing their expression pattern among all cells, and the right term weight as the penalty coefficient \(\sigma =\frac{\cos {({g}_{i},{\lambda }_{m})}^{2}}{\cos {({g}_{i},{\lambda }_{m})}^{2}+\omega \times {\sum }_{t=1,t\ne m}^{M}\cos {({g}_{i},{\lambda }_{m})}^{2}}\), and \(\omega\) (\(\omega > 0\)) indicates the penalty factor for expression in non-target cell type \({C}_{t}\)(\(t\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,M\}\backslash \{m\}\)). In such circumstance, the more cell types of non-target cells expressed \({g}_{i}\) or the larger set value of \(\omega\) will both result in smaller values of the penalty coefficient \(\sigma\) and smaller specificity score \(CT{S}_{i,m}\). The \(\omega\) acts as a regularization parameter that governs the contribution of off-target expression to the specificity score. Higher values emphasize stringency and penalize broad expression more strongly, and lower values reduce this penalty, potentially preserving genes that are important but not strictly cell-type specific. The default value of \(\omega\) is set to 1, and users can modify as specific purpose (Supplementary Notes).

To combine the two heterogeneous weights (CTS and GRS), we first align their distributions. For each gene \({g}_{i}\), we apply a log transform with a small offset to avoid undefined values: \({\log }_{10}({\mathrm{GRS}}_{i}+1\times {10}^{-6})\) and \({\log }_{10}({\mathrm{CTS}}_{i}+1\times {10}^{-6})\). To ensure that a few eRegulons with high GRS or CTS scores are adjusted to the same scale while minimizing the influence of potential extreme outliers, the 99th percentile of eRegulon scores is computed and used as the ceiling29. Subsequently, max-min scaling is applied using the max_min_scale() function in scMORE. This normalization harmonizes the two weights while preserving their within-weight ranking, enabling fair and reliable integration.

Inference of trait-relevant score

To evaluate the association between eRegulons and the trait of interest, scMORE calculates the TRS for each TF-eRegulon at the cell-type level. Following a previous study30, we define the TRS for a given eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) (\(k\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,K\}\)) in a cell type \({C}_{m}\) (\(m\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,M\}\)) by integrating both genetic relevance and CTS as follows:

Here, \(K\) represents the number of inferred eRegulons. The specificity score \({\mathrm{CTS}}_{k,m}\) of the eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) in the cell type \({C}_{m}\) is calculated by aggregating the specificity scores of the TF \(f\) and its target genes within the eRegulon for that specific cell type, as defined below:

In this equation, ||rk|| represents the number of nodes in eRegulon \(k\), \({\mathrm{CTS}}_{f,m}\) denotes the specificity score of the TF \(f\) in the cell type \({C}_{m}\), and \(\theta\) is a weight parameter that adjusts the relative contribution of target gene specificity within the eRegulon \({r}_{k}\). A value of \(\theta =1\) assigns equal importance to the specificity of the TF and its target genes, while \(0\le \theta \le 1\) reduces the relative weight of target gene specificity compared to TF within the same eRegulon. Similarly, the GRS \({\mathrm{GRS}}_{k,m}\) of an eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) (\(k\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,K\}\)) is defined as:

where \(\rm{GR{S}}_{f,m}\) represents the GRS of the TF \(f\) in the cell type \({C}_{m}\), and \(\theta\) functions as described above. Unless stated otherwise, scMORE applies a default value of \(\theta =0.5\) in its computations.

The term \(\mathrm{sd}({\mathrm{GRS}}_{k,m},{\mathrm{CTS}}_{k,m})=|{\mathrm{GRS}}_{k,m}-{\mathrm{CTS}}_{k,m}|/\sqrt{2}\) is used as a penalty to control the divergence between GWAS-derived relevance and CTS so that results are not driven by one data type alone (Supplementary Notes). Accordingly, scMORE prioritizes eRegulons with concordantly high genetic relevance and specificity.

Assessment of significant eRegulons

To evaluate the statistical significance of each eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) (\(k\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,K\,\}\)) within a given cell type \({C}_{m}\) (\(m\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,M\,\}\)), we implemented an MC permutation strategy22 using the getRandomScore() function in the scMORE package. For each eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) composed of \(||{r}_{k}||\) genes, we generated \({T}^{Ctrl}\) control eRegulons by randomly sampling one TF from a predefined TF pool and \(||{r}_{k}||-1\) genes from the background gene set, defined as all genes expressed in the corresponding cell type used in the trait association analysis. To avoid bias, genes from the original eRegulon were excluded from the sampling pool. Sampling was performed with replacement, ensuring robustnesss even with limited gene pools. This approach disrupts the biological structure of the original eRegulon by decoupling node identities and their associated weights from both GWAS and single-cell data. As a result, each control eRegulon \({r}_{z}\) (\(z\in \{1,2,3,\ldots ,{T}^{\,Ctrl}\},z\notin k\)) is size matched but compositionally distinct, serving as an appropriate null model.

Analogous to the calculation of \({\mathrm{TRS}}_{k,m}\), \({\mathrm{GRS}}_{k,m}\) and \({\mathrm{CTS}}_{k,m}\) for the actual eRegulon \({r}_{k}\), scMORE iteratively calculates these three scores for each control eRegulon \({r}_{z}\) within the cell type \({C}_{m}\). The empirical P values for \({\mathrm{TRS}}_{k,m}\), \({\mathrm{GRS}}_{k,m}\) and \({\mathrm{CTS}}_{k,m}\) for the actual eRegulon \({r}_{k}\) are calculated using the following formula: