Abstract

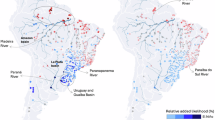

In April–May 2024, unprecedented floods in Rio Grande do Sul displaced around 600,000 people and caused more than 180 deaths. This study unpacks the role of anthropogenic climate change and the preceding El Niño conditions on the extreme rainfall using a probabilistic event attribution. This event was rare even in the 2024 climate, with a return period exceeding 100 years. With global warming of 1.2 °C, such an event has become approximately 2 (0.06–4200) times as likely, or equivalently 12% (−13 to +43%) more intense. The recent El Niño event also approximately doubled (0.7–37 times) the likelihood of such an event relative to a neutral year. In any disaster, the vulnerability and exposure context play a crucial role in turning the meteorological hazard into impacts, underscoring the need for equitable adaptation measures to break the cycle of risk and inequality in the context of a warming climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Between April 24th and May 4th, the southernmost state of Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul, experienced persistent and extraordinary precipitation, equivalent to three average months of rain in a two-week period, with an average accumulation of 420 mm. This record-breaking precipitation (Fig. 1) led to historically high river levels, putting 12 dams under pressure, and caused extensive flooding affecting 90% of the state’s municipalities. Flooding occurred across much of the state but was particularly intense in the capital Porto Alegre, where this was the wettest start to May for 63 years1. These floods constitute one of the most significant humanitarian disasters experienced in Brazil. In total, 2.3 million individuals were affected2, with 600,000 people displaced and more than 180 fatalities caused3,4. The violent floods caused losses, damages, and disruptions, impacting people from every demographic across Rio Grande do Sul’s approximately 11 million inhabitants, including higher-income communities5. However, differential exposure, vulnerability, and coping capacity rendered certain groups disproportionately impacted.

Top left: Map of accumulations over the wettest 4-day period. Rio Grande do Sul is highlighted in dark red. Top right: The daily precipitation averaged over Rio Grande do Sul in 2024 (red) and in all other years in the record (grey). The dark (light) red bars show the 4-day (10-day) window in which the precipitation was most intense. Middle: Anomalies of rolling 4-day accumulations of precipitation over Rio Grande do Sul in 2024 (red) versus the 1990-2020 climatology and against all other years from 1979 in the record (grey). Bottom: time series of maximum 4-day March-May precipitation over Rio Grande do Sul, and the relative December-February (DJF) Niño3.4 index (see Methods), with a value of 1.107 in DJF 2023/24.

The extreme precipitation observed across most of the state (Fig. 1) was driven by the persistent “South Atlantic high”, a region of high pressure over eastern Brazil and the South Atlantic (Fig. 2). This intensified the trade winds, facilitating the flow of easterly moisture from the tropical Atlantic Ocean to the central region of Brazil, followed by enhanced moisture transport from central Brazil towards Rio Grande do Sul through the South American Lower-Level Jet (SALLJ). The air masses travelled along a continental route, having originated from the central region of Brazil several days earlier (Fig. 3a). The persistent high-pressure system that developed over the south Atlantic Ocean acted as a blocking system of the westerly flow. This resulted in high precipitation amounts that accumulated over a period of several days and led to unprecedented floods over Rio Grande do Sul (Figs. 1, 3b).

The red box shows the region shown in Fig. 1, panel 1. High pressure in the South Atlantic facilitates the transport of moisture into central Brazil, then southeast via the South American low-level jet to Rio Grande do Sul. Data from ERA5: while this precipitation data is not used in the study, the dataset is used here to understand the large-scale event dynamics.

a (left) Ensemble of 5-day backward trajectories ending in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul (30.04°S, 51.21°W) and at approximately 850 hPa (1250 m above ground level) on the 2 May. The map shows the horizontal transport pathways of air parcels, the middle panel shows the corresponding air parcel elevation (in metres), and the lower panel shows rainfall (in mm per hour). Source: NOAA Hysplit83. b (right) Satellite-based precipitation estimates on 02/05/2024 over central South America and Rio Grande do Sul (black). Data: IMERG (see ‘Methods’ for details).

Precipitation trends and variability in Southern Brazil (comprising the states of Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul) are influenced by a combination of the seasonal patterns (largely affecting the timing of precipitation), interannual climate phenomena such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)6, decadal-scale variability and climate change. This region is characterised by a subtropical climate (transition between tropical and temperate climate) with a continuous supply of moisture from the Atlantic Ocean and the Amazon region7. Mesoscale convective systems are the most important rain-producing weather systems in this region mainly during spring/summer (from September to February), whereas cold fronts are responsible for precipitation during fall/winter (from March to August). For this reason, precipitation is distributed evenly throughout the year8, making it the second rainiest region in the country, next only to the Amazon rainforest in Northwestern Brazil9.

During late 2023 and early 2024, ENSO was in its strongly positive (El Niño) phase (Fig. 1). The subtropical South Atlantic high centre normally moves westward over central Brazil during fall/winter (eastward over the South Atlantic during spring/summer). However, during this event, the Pacific South America (PSA) wavetrain pattern related to El Niño amplified the high-pressure centre over central Brazil10, making it larger and more persistent there. Typical of El Niño episodes, this causes anomalous subsidence in the region and weakens the South Atlantic Convergence Zone, a convective band in the austral summer characterised by intense convergence of warm, moist air extending from the Amazon Basin to the subtropical South Atlantic11. At the same time, the winds associated with the anomalous high-pressure centre enhance the SALLJ, a climatological northwesterly flow east of the Andes that transports moisture from tropical latitudes to southeast South America12. Moreover, during this event, the tropical Atlantic was anomalously warm, feeding more moisture to the SALLJ.

It is noteworthy that, even though the PSA pattern is strongest during spring and summer, heavy precipitation and floods can occur during fall and winter when the frontal systems start to come from higher latitudes and become stuck over the region, blocked by the persistent high-pressure centre over central Brazil. Thus, the most impactful floods in southern Brazil associated with El Niño tend to occur during fall and earlier winter, such as the floods of the Itajai Açu River in July 198313. Indeed, another important contributing factor to the heavy rain in May 2024 was the proximity of the jet stream bringing more instabilities (frontal systems). These fronts were then blocked by the high-pressure centre over central Brazil, leading to an extended period of several days in which extreme precipitation accumulated over southern Brazil.

Even though this pattern is consistent with typical ENSO teleconnections and impacts, stronger El Niño phases in the past have not resulted in such intense precipitation events (Fig. 1), and several factors could have been intensified by increasing global mean surface temperature (GMST). For instance, it is expected that climate change will intensify this teleconnection pattern14. Consequently, the high-pressure centre over central Brazil is becoming larger and more persistent, pushing warmer air that holds more moisture further south. Of the five biggest floods ever recorded in Porto Alegre (the capital of Rio Grande do Sul), three occurred in the nine months up to May 2024, the largest having occurred in May 2024 itself, and the fourth and fifth in November and September 2023, respectively. The second largest occurred in 1941 and third largest in 1873.

Existing literature analysing trends in extreme precipitation, and formal attribution of some of the most significant extreme precipitation and flooding events in South and Southeastern Brazil, suggest an increasing trend in the intensity and frequency of extreme precipitation in various regions. Ávila et al.13 analysed precipitation trends and their link to flash floods and landslides in southeastern Brazil, revealing a significant increase in extreme precipitation from 1978 to 2014, especially over mountainous areas. These changes in precipitation patterns have already impacted streamflow in the region, with an increasing trend in floods between 1980 and 2015 over most of the river basins in southern Brazil15. Also, there have been temporal and spatial changes in the occurrence of extreme events of precipitation in Santa Catarina16, the state north of Rio Grande do Sul. Furthermore, for this specific event, an analogue-based analysis by ClimaMeter found that extreme precipitation events are up to 15% more intense in the period 2001–2023 compared to 1979–2000, studying an area over the eastern coast of Rio Grande do Sul (a box bounded by 48-53°W, 28-32°S), with an additional minor contribution from modes of variability including ENSO17.

Studies by the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE) corroborate these findings, highlighting that the climate has already changed in Brazil over recent decades, impacting the occurrence of climate extremes, such as maximum precipitation in 5 days (RX5day). Observations over the last six decades, collected by the National Institute of Meteorology (INMET), show a notable change in climate patterns. The results indicate an increase of between 10 and 30% in the southern region of Brazil18. This is consistent with the findings of the IPCC AR619, which show that increases in the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events over this region have been observed in the past. With additional increases in warming levels (model projections for a particular level of warming with respect to pre-industrial climate), these events are expected to become more frequent and more intense. These wetter conditions will likely lead to longer periods of flooding and enhanced river discharges20.

Based on CMIP6 climate models, Medeiros et al.21 found that Brazil is projected to experience an increasing tendency for severe and prolonged extreme precipitation, especially in the central north and the southern parts (Almazroui et al.22; IPCC19). Other studies based on CMIP5 climate models came to similar conclusions: southern Brazil is expected to have a wetter mean climate along with widespread increases in the intensity of wet days for the period 2050–2100 as compared to the present day in southern Brazil, as well as higher precipitation variability (see Fig. 3 in Alves et al.23; Cai et al.14).

Given the evidence of increasing trends in precipitation extremes in southern Brazil, further enhancing understanding of these hazards is of clear societal significance. Beyond considering trends, individual disasters provide learning opportunities for managing risks, especially in a constantly changing climate. The 2024 event was unprecedented in scale, both in terms of meteorology and impacts, for the region. Even more than other events, such record-breaking disasters show what is plausible and therefore provide critical case studies. To understand the changing risk of such events, this study aims to elucidate the respective roles of anthropogenic climate change and the preceding ENSO conditions in the likelihood and intensity of such a hazard, as well as placing it in the context of vulnerability and exposure factors that drive such disasters.

In the wake of the 2024 event, World Weather Attribution undertook a rapid study on the extreme precipitation and the vulnerability and exposure factors contributing to the disaster24. To capture the nature of the precipitation that resulted in extreme flooding across Rio Grande do Sul, this study analysed two event definitions: the March-May maximum 4- and 10-day accumulations, averaged over the state of Rio Grande do Sul (Fig. 1 and S3). Extreme precipitation occurring during the March-May season specifically was selected because, despite the relatively flat mean seasonal cycle of precipitation in the region, different mechanisms leading to precipitation extremes are prevalent at different times of year, including the influence of ENSO. There is also greater variability exhibited in extremes in the austral spring and early summer period from September to December (Fig. 1, S3). Two temporal definitions arose because the 4-day window captured the most severe single event in which record precipitation fell across several consecutive days, while the 10-day window (encompassing 26th April–5th May, inclusive) captured the succession of heavy precipitation events, including the very wet individual days on either side of the major 4-day peak (Fig. 1, S2). However, despite characterising different extremes, the results were not significantly different for the two event definitions, largely due to the extreme magnitude of the largest 4-day period dominating both event definition.

The rapid study analysed the influence of both the observed GMST rise of 1.2 °C since preindustrial times and the preceding El Niño (using the relative December–February (DJF) Niño3.4 index; see Methods) on the extreme precipitation event, as well as the relative influence of a further 0.8 °C of warming from 2024. This work primarily aims to introduce this analysis of ENSO alongside GMST, using a common probabilistic event attribution framework, into the scientific literature. It also builds on the original study in several ways, focusing on the 4-day event definition (henceforth rx4day). First, an additional gridded observational dataset is analysed, and the event itself is included is all datasets from the original study. Second, the sensitivity of the results to different statistical models is tested, including the choice of covariates, and the statistical distribution and its parametrisations. Third, the model-based analysis is extended to a global warming level of 2.6 °C above preindustrial levels (1.4 °C above 2024). This level aligns with the latest Emissions Gap Report25 from the United Nations Environment Programme, reflecting the likely temperature rise given currently implemented policies.

Results

Observational analysis

Five gridded observational (CPC, GPCC, CHIRPS, and BR-DWGD) and reanalysis-based (MSWEP) datasets (see ‘Methods’ for further details of all datasets) are used to determine the return period of the observed event in the current climate and the changing likelihood of such an event due to observed GMST warming of 1.2 °C and the preceding El Niño event. Time series of the March–May maxima of 4-day precipitation in each of these datasets are shown in Fig. 4. At the time of the initial rapid study, the event was observed only in CPC and MSWEP. The current study includes updated data for both CHIRPS and GPCC, including the event and adds the BR-DWGD dataset up to March 2024. However, this has not notably changed the estimated return periods of the event(s) or the overall conclusions of the study.

a CPC, b MSWEP, c CHIRPS, d GPCC, e BR-DWGD, f BR-DWGD (from 1979–onwards). The solid black line shows the fitted trend associated with increasing GMST and variability due to Niño3.4; the blue lines show the expected magnitude of 1-in-5-year and 1-in-50-year events under the same statistical model. The dotted green line shows a nonparametric Loess smoother fitted to the observations. The 2024 event is shown as a pink box.

The rapid study used a nonstationary generalised extreme value (GEV) distribution that scales with covariates of GMST and ENSO to model changes in the extreme index rx4day. In this study, the choice of model was tested using goodness of fit and sensitivity analyses, for different formulations of the relationship between extreme index and the covariates (Table 4), as well as different combinations of covariates and use of the Gumbel and Gaussian distributions rather than the GEV (Tables 4, 5 and 6). On balance, the GEV scaling with GMST and ENSO provided the best compromise between goodness of fit and model complexity across observations and models, and in capturing the extreme tail of the distribution in which the event lies (Figs. 5, 9 and 10). While other parametrisations were rejected and may give different quantitative results, the overall qualitative messages of the analysis are unlikely to be affected. For further understanding of the sensitivity of the analysis, results of the observation-based analysis using a model without ENSO (GMST-only), and annual rather than March-May maxima, are shown in the supplementary material (Tables S1 and S2). Results of the whole analysis using the Gaussian distribution are also shown in the supplementary material (Tables S3 and S4). None of these results change the overall messages of the study.

a CPC, b MSWEP, c CHIRPS, d GPCC, e BR-DWGD, f BR-DWGD (from 1979–onwards). Data points represent the full times series of Rx4day for each dataset, scaled to the current climate and a climate without anthropogenic warming. The observed event is shown by the highest red dot and the pink line labelled as the ‘observed event’ represents the 1 in 100-year event used in this analysis. The shaded areas represent the bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals on the curves, and the degree of overlap between the uncertainty bounds of each curve gives an indication of the uncertainty on the overall uncertainty on the influence of GMST, as quantified in Table 1.

Across all datasets, the 2024 event was unprecedented (Fig. 4) and thus found to be extremely rare in the current climate, with return periods of ~100–250 years and uncertainty ranges from ~20 years to infinity (Table 1). To ensure the statistical stability of the analysis given the relatively short data records (mostly ~1979–present), we analyse the 1 in 100-year event in this study. This choice does not affect the attributable changes in magnitude and will result in a slightly lower and better constrained probability ratio compared to a higher return period event. This return period is also typically considered a benchmark for risk analysis.

All datasets show increasing trends in the likelihood and intensity of 1 in 100-year precipitation events in the region because of both warming GMST and El Niño conditions (Fig. 5, Table 1). Though the best estimates show positive trends, the estimated trends in likelihood with GMST for all datasets have very wide uncertainty ranges, with all upper limits tending to infinity, and lower limits significantly below 1. In the case of CPC and CHIRPS, the uncertainty range is between 0 and infinity, thus giving no useful information at the 95% confidence level. The BR-DWGD dataset also has both best estimates and upper bounds at infinity, which suggests a very strong trend, but one which cannot be quantified. As a result, these three datasets are excluded from the final synthesis.

The reason for this wide uncertainty range can be probed further by investigating the statistical model. Figures 4 and 5 show the statistical model fit to each dataset, with GMST and ENSO as covariates. In Fig. 4, the dashed green line indicates a nonparametric loess trend fitted to each dataset. This highlights that in all datasets there is a weak decadal oscillation, which peaks in the mid-1990s, decreases until around 2010, and then increases again. One candidate to explain this is the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), a large-scale pattern of variability (representing a group of interacting processes) in surface temperatures of the North Pacific26. However, in observational and reanalysis data, incorporating the PDO alongside GMST (see Methods) resulted in a worse fit overall when compared against either GMST and ENSO, or GMST alone (Table 7).

Consequently, we were unable to identify a covariate that adequately captures this behaviour in the statistical model, but note that because of this unexplained variability, there is very high uncertainty about the relationship between GMST and historical extreme precipitation in this region. This is further confirmed by estimating the trends in the BR-DWGD time series across different time horizons—while the trend from 1960 onwards is statistically significant, the trend from 1979 onwards in the same dataset (matching most of the other datasets) has 95% uncertainty bounds from 0 to infinity. Therefore, while the full longer timescale dataset (1960–2024) cannot be integrated into the synthesis quantitatively, it adds an additional line of evidence in favour of increasing extremes on a qualitative level. Finally, Fig. 5 shows the return curves for each statistical model and the associated dataset. While the BR-DWGD, MSWEP and GPCC data are well represented by the respective curves, CPC and CHIRPS exhibit significant variation, with wide and overlapping uncertainty ranges between the present and preindustrial climates.

Despite the unexplained oscillation and wide uncertainty ranges, the consistency of the increase across datasets combined with physical reasoning suggests a likely increase in such extremes with warming. Similar analysis using climate models, as undertaken in the following section, is therefore required to further explore the quantification of this effect. Finally, the results on the influence of ENSO are much more confident than for GMST in the observational analysis. Compared to a neutral ENSO phase, the current (DJF) El Niño index value of 1.107 resulted in a clear and consistent increase across all datasets and for both events: by a factor of 3–6 in PR and 6–11% in intensity, with four of the five datasets providing statistically significant results (Table 1).

Attribution synthesis

To assess the attributable influence of anthropogenic climate change and the ENSO phase on the 1 in 100 year value of the rx4day index, we synthesise evidence from both observation-based products and climate models, using a peer-reviewed probabilistic attribution synthesis procedure27. Prior to this synthesis, climate models were evaluated for their ability to reproduce precipitation patterns and extremes in the region (see ‘Methods’ and Supplementary Material; Figs. S4–9, Table S5). This is contingent in part on the ability of the models to represent the underlying dynamics, such as the SALLJ and associated trends in rates of moisture transport28. Recent work shows that state of the art GCMs and RCMs are increasingly able to capture this phenomenon, either directly29 or indirectly through accurate representation of precipitation extremes30,31. Additionally, during the model evaluation step, the ability of models to capture the relevant phenomena is implicitly assessed by comparing the fitted statistical model parameters to those of the observation-based products (see ‘Methods’ and Supplementary Material; Table S5). Nonetheless, changes in such dynamics over time remain a source of deep uncertainty in the results presented here. This could be minimised by isolating the thermodynamic influence using a storyline approach32, or investigated further through changes in atmospheric winds and moisture transport29, though such analyses are beyond the scope of this study.

In the model evaluation step, no models or ensemble members were ranked as ‘good’ across all criteria (Table S5). We therefore use models that were ranked as ‘reasonable’ overall and reject those with any ‘bad’ aspects. Overall, this left 9 of 13 CORDEX models, all 11 CMIP6 models, 2 of 3 AM2 ensemble members and 7 of 10 FLOR ensemble members. Following the evaluation step, we use the same statistical model that accounts for GMST and ENSO for the models and observation-based products to evaluate their respective influences, estimating the parameters separately for each individual dataset Table 2. Combining the results from observational/reanalysis datasets and model ensembles using the synthesis procedure (see Methods) gives an overarching attribution statement. Figures 6–8 show the changes in probability and intensity for the observations (blue), models (red) and synthesis (magenta), for the GMST increase of 1.2 °C (Fig. 6), the preceding DJF El Niño (Fig. 7), and future GMST increase to 2.6 °C above preindustrial (Fig. 8).

The best estimate for each dataset is shown by the central black line, with the uncertainty range given by the width of the bar (see Methods and references therein for full details). In a, the ‘!’ next to some model names shows where the upper bound was infinite, and the x-axis for probability ratio is capped at 1020. In b, the number in brackets by each model shows the number of ensemble members included in the estimates of probability ratio and change in intensity.

The best estimate for each dataset is shown by the central black line, with the uncertainty range given by the width of the bar (see Methods and references therein for full details). In a, the ‘!’ next to some model names shows where the upper bound was infinite. In b, the number in brackets by each model shows the number of ensemble members included in the estimates of probability ratio and change in intensity.

The best estimate for each dataset is shown by the central black line, with the uncertainty range given by the width of the bar (see Methods and references therein for full details). In a, the ‘!’ next to some model names shows where the upper bound was infinite. In b, the number in brackets by each model shows the number of ensemble members included in the estimates of probability ratio and change in intensity.

While the uncertainties around the observations and some models are very large, the overall picture is consistent: all observational datasets and 17 of 22 (77%) models show increases in rx4day due to a 1.2 °C increase in GMST (Fig. 6). This level of model agreement exceeds the ‘likely’ threshold from Mastrandrea et al. (2011)33, commonly used by the IPCC. The increase with GMST is further reinforced by the longest observational dataset, BR-DWGD, which indicated a strong statistically significant trend when using data from 1960 onwards, which reduced the influence of interdecadal variability (Table 1). Similarly, for ENSO all observational datasets and all but one model (95%) show an increase in rx4day due to the 2023/24 El Niño (Fig. 7). When quantifying these effects, the synthesis results show that GMST warming of 1.2 °C resulted in an increase in likelihood by about a factor of 2.0 (~0.06 to 4200) and an intensity increase of 12% (~−12% to +43%), and the El Niño resulted in an increase in likelihood by about a factor of 2.4 (~0.7 to 37) and an intensity increase of 9% (0.3% to 20%) relative to a neutral phase (Table 3). Using a Gaussian distribution rather than a GEV gives a similar message, with very similar changes in intensity and probability ratios approximately a factor of 1.5–2.5 larger than for the GEV (Table S4).

The attributed anthropogenic influence is further corroborated by assessing the change in likelihood and intensity in a 1.4 °C warmer climate compared to the time of the observed event (2.6 °C above preindustrial). Again, there are relatively large uncertainties for individual models but an overall increasing likelihood, with probability ratio of around 1.7 (~0.5–30) and an intensity change of about 7% (~−6 to +19%) (Table 3; Fig. 8). While the model-based estimates are consistently much lower than observations to date, and slightly below physical expectations from the Clausius-Clapeyron relation, we are not confident in stating whether these estimates are likely conservative given the very wide observational uncertainty ranges.

Discussion

The unprecedented floods in Rio Grande do Sul in April–May 2024 affected over 90% of the municipalities in the state, or an area equivalent to the UK, displacing around 600,000 people and causing over 180 deaths. The overall risk of such a catastrophe depends on three key factors: hazard, exposure and vulnerability. This study explores the key drivers of the hazard. However, it is crucial to place these results in the context of vulnerability and exposure factors, to assess the changing likelihood of such impacts both now and in the future, with the latter depending on policy choices at a range of different scales.

First, while the state is often perceived as well-off, it still has significant pockets of poverty and marginalisation. Low income is strongly correlated with higher vulnerability to flood impacts34. Informal settlements, indigenous villages, and predominantly quilombola (descendants of enslaved Africans) communities have been severely impacted35,36,37. The lack of a significant extreme flood event until recently in Porto Alegre contributed to reduced investment and maintenance of its flood protection system38,39,40, with the system reportedly beginning to fail at 4.5 m of flooding despite its stated capacity to withstand water of 6 m41. This, in addition to the extreme nature of this event, contributed to the significant impacts of the flood and points to the need to objectively assess risk and strengthen flood infrastructure to be resilient to this and future, even more extreme, floods.

Furthermore, while environmental protection laws exist in Brazil to protect waterways from construction and limit land use changes, they are not consistently applied or enforced, leading to encroachment on flood-prone land and therefore increasing the exposure of people and infrastructure to flood risks42,43,44. Finally, forecasts and warnings of the floods were available nearly a week in advance45,46, but the warning may not have reached all of those at risk, may not have adequately communicated the potential severity of the impacts or informed people of what actions to take in response to the forecasts. It is imperative to continue to improve the communication of risk that leads to appropriate, life-saving action.

The precipitation hazard itself was unprecedented. The 4-day precipitation totals over Rio Grande do Sul were found to be extremely rare in the current climate, with a return period of 100–250 years. This study focused on a 1 in 100-year return period event, which is also typically considered a benchmark for risk analysis. First, ENSO was found to be important to explain the variability in the observed precipitation, consistent with previous research. Most previous heavy precipitation events in the area occurred during El Niño years and similarly the role of El Niño in this event was significant. In observations, compared to a neutral ENSO phase, the current (December-February) El Niño resulted in a consistent increase across all datasets, indicating its importance in the analysis. Second, to assess the role of human-induced climate change and ENSO we combine observation-based products and climate models that include the observed ENSO relationship and assess changes in the likelihood and intensity for the 4-day heavy precipitation over Rio Grande do Sul. Results suggest that the El Niño conditions at the time of occurrence drove an increase in likelihood by about a factor of 2.4 (0.7–37) and an intensity increase of 9% (0.3–20%) relative to a neutral phase.

Third, GMST has driven an increase in likelihood of a factor of 2 (0.06–4200) and intensity increase of ~12% (−13% to +43%). These findings are corroborated when looking at a climate of 2.6 °C of global warming since pre-industrial times, where we find a further increase in likelihood of a factor of ~1.7 (0.5–30) and an increase in intensity of about 7% (−6% to +19%) compared to the 1.2 °C world of 2024. Almost none of these synthesis results are significant at the 95% confidence level, and the probability ratios have wide uncertainty ranges. These uncertainty ranges result in part from an apparent recent decadal variability in many observational times series since ~1980. This variability does not appear in the period 1960–1980 in the only reliable daily gridded dataset available for such a period, but further investigation of this is hampered by the dearth of other such datasets. As a result, the quantification of the role of GMST remains challenging.

However, there are several lines of evidence that suggest that GMST amplified this precipitation event (as well as the El Niño conditions, by a similar amount), suggesting that strong qualitative messages may be drawn. These are as follows. First, the consistency of increasing trends (albeit with high uncertainties) across gridded observational datasets and models, and across statistical models. Second, the Clausius-Clapeyron relation gives a robust underlying physical basis to expect such results. Third, the strong increase in such extremes since the 1960s in one dataset suggests that more recent decadal variability, likely unrelated to the influence of GMST, increased uncertainties across shorter datasets. Fourth, other scientific literature studying similar extremes using other methods comes to a similar conclusion.

Taken together, the hazard analysis in the context of vulnerability and exposure indicates that Rio Grande do Sul is likely to face more frequent and severe flood-related impacts in the future, especially without serious investment in mitigation and adaptation responses. The floods revealed the unequal distribution of flood protection infrastructure, which perpetuates inequalities in urban environments. Unprotected regions, typically inhabited by lower-income populations, face higher risks of flooding and associated impacts. This disparity creates a poverty trap, where those in unprotected areas are more susceptible to flood-related disasters, leading to repeated losses and hindered economic progress. Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach to urban planning and flood management that prioritises equitable protection and development. Future investments in flood protection should integrate social, economic, and environmental considerations into urban planning to help create more inclusive and resilient cities.

Finally, given the unprecedented nature of the event, further work on the confluence of drivers may be informative. For instance, exploring if this event belongs to the same distribution as past extremes and was simply amplified by a combination of ENSO and GMST, or if other physical phenomena conspired to create a unique event that might be represented by a heavier-tailed or even separate extreme distribution47.

Methods

Event details

Porto Alegre is situated on the Guaíba River, where five rivers meet. In May 2024, it saw water levels rise over 5 m—exceeding the 3-m flood threshold48,49. While the flood protection system is designed to withstand flooding of up to 6 m, reports suggest that malfunctioning floodgate motors and gaps between doors and the wall led the floodwaters to begin to enter the city 1.5 m below its stated capacity41. In addition, a partial dam collapse of the “14 de Julho” hydroelectric plant on the Das Antas River, some 180 km northwest of Porto Alegre, is reported to have caused an approximately 2-m flood wave, exacerbating the flooding in inundated communities nearby50,51,52.

Due to the extensive flooding, five hydroelectric dams were shut down and power supplies had to be cut, leaving half a million people without electricity in and around Porto Alegre53,54. Only one of the city’s six water treatment plants remained operational, leaving around 650,000 people—approximately a third of the state’s population—without water53,54. About 3000 health care units were impacted, including 110 hospitals affected, 17 of which ceased operations entirely and 75 providing only partial services35. Relief efforts were severely hampered by extensive damage to infrastructure due to both flooding and landslides, with over 15,000 landslides triggered by the event55. 95 blockages were reported on highways throughout the state and Porto Alegre was almost completely cut off. The international airport did not reopen fully until the end of 202456.

The economic repercussions of the flooding are expected to be extensive; the state’s economy represents accounts for around 6.6% of Brazil’s GDP and preliminary estimates suggested a 0.3% decrease in national GDP as a result of the event57. Food production, which accounts for nearly 17% of the state’s GDP, has been particularly impacted, with the Brazilian bank Bradesco forecasting a 3.5% recession in Brazil’s agricultural sector in 2024 and potential price spikes, particularly on rice and dairy products, are a particular concern58. Overall damages from the event exceeded US$15 billion59.

Rio Grande do Sul is highly susceptible to flooding due to its low elevation (10 m above sea level) and vast river systems. Extensive changes in land use and land cover have worsened this risk. A MapBiomas survey shows that from 1985 to 2022, the state lost 22% of its native vegetation (3.6 million hectares), mainly to soybean farming42,60. In the Guaíba Basin, where flood risks are highest, this figure rises to 26% (1.3 million hectares). The destruction of forests, fields, and wetlands has diminished the land’s capacity to absorb precipitation, intensifying flood risk. Urban expansion and large-scale agriculture in the basin further exacerbate these hazards40. The state capital, Porto Alegre, has experienced significant floods in 1873, 1928, 1936, 1941, 1967, and 202340,43. To protect Porto Alegre from recurring flooding, the city constructed a flood protection system in 1974, whose most prominent feature is the Mauá Wall; a 2.6 m long and 3-m-high concrete levee. This extensive system, that spans 68 km in total, comprises walls, levees, 23 pumping stations, and 14 floodgates39,41,61.

In some regions, especially in the broad central strip of the valleys, plateau, hillside, and metropolitan areas, precipitation accumulations exceeded 300 mm in less than a week. For example, in the municipality of Bento Gonçalves, volumes reached 543.4 mm. From April 29–May 2, when heavy rain settled over Rio Grande do Sul, accumulations have ranged between 200 mm and 300 mm. In the capital, Porto Alegre, the volume reached 258.6 mm in just three days. This amount corresponds to more than 2 months’ worth of rain, compared to the 1990–2020 climatological values for April (114.4 mm) and May (112.8 mm).

The INMET stations that recorded the most rain between April 26th and 9 am May 2nd were Soledade (488.6 mm), Santa Maria (484.8 mm), and Canela (460 mm). The conventional meteorological station in Santa Maria set a 24-h precipitation record with 213.6 mm on May 1st. This was the highest precipitation recorded in the municipality in 112 years of observation, surpassing the previous record of 182.3 mm set on June 23rd, 1944. In just 3 days, the precipitation total in the city reached 470.7 mm, which corresponds to 3 months’ worth of rain according to the climatological 1990–2020 average.

A comparison between major precipitation and flooding events in 1941 and 2024 shows that while in 1941, it took 22 days for the water level in Guaíba Lake to reach 4.76 m above normal levels, in 2024 it took only 5 days for the Guaíba to exceed 5 m49 (Fig. S1), well above the flood level of 3 m necessary to flood the city48. Moreover, the 2024 event flooded not just Porto Alegre but parts of 90% of municipalities in the state, with all the excess water flowing eventually to Guaíba. In 1941, less rain fell, but combined with strong winds from the south was enough to cause disastrous flooding. Consequently, the 2024 floods are also more impactful. The 1941 event flooded 15,000 homes and left 70,000 people homeless. A third of the region’s commerce and industry were closed for around 40 days. The 2024 event affected the whole state and many more cities, more than 2.1 million individuals, with 600,000 people displaced and 76,000 citizens living in shelters just in the metropolitan area of Porto Alegre. The area was also still recovering from floods in September and November 2023 in which Guaíba reached 3.18 m and 3.46 m49.

Observational data

In this study, we use six observational and reanalysis datasets to visualise and analyse changing precipitation extremes:

-

1.

IMERG—This product uses NASA’s Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) algorithm for combining information from the GPM satellite constellation to estimate precipitation over the majority of the Earth’s surface. IMERG fuses precipitation estimates collected during the TRMM satellite’s operation (1998–2015) with recent precipitation estimates collected by the GPM mission (2014–present). IMERG is available from 1998 to present in near real-time with estimates of Earth’s precipitation updated every half-hour. Here, daily data are used with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°.

-

2.

CPC daily precipitation. This is the gridded product from NOAA PSL, Boulder, Colorado, USA known as the CPC Global Unified Daily Gridded data, and is available at 0.5° × 0.5° resolution, for the period 1979–present. Data are available from NOAA (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globalprecip.html).

-

3.

The Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation (MSWEP) v2.8 dataset (updated from ref. 62 is fully global, available at 3-hourly intervals and at 0.1° spatial resolution, available from 1979 to ~3 h from real-time. This product combines gauge-, satellite-, and reanalysis-based data.

-

4.

The precipitation product developed by the UC Santa Barbara Climate Hazards Group called “Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data” (CHIRPS)63. Daily data are available at 0.05° resolution. The product incorporates satellite imagery with in-situ station data.

-

5.

GPCC Full Data Daily Product Version 2022 of daily global land-surface precipitation totals based on precipitation data provided by national meteorological and hydrological services, regional and global data collections as well as WMO GTS-data64.

-

6.

Brazilian Daily Weather Gridded Data (BR-DWGD) is available for the entire land surface of Brazil at spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°, from 1961/01/01–2024/03/2065.

As a measure of anthropogenic climate change, we use the (low-pass filtered) global mean surface temperature (GMST), where GMST is taken from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Goddard Institute for Space Science (GISS) surface temperature analysis (GISTEMP)66,67.

As a measure of the El Niño—Southern Oscillation cycle (ENSO), we use the detrended relative Niño3.4 index. This is the Niño3.4 index (average SST over 5°S–5°N, 120°–170°W) minus the SST between 20°S and 20°N to adjust the index for climate change, as proposed in ref. 68, but without rescaling each calendar month.

Finally, as a measure of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), we use the index defined by Mantua et al.84. This is the leading principal component of monthly sea surface temperature anomalies, in the North Pacific Ocean, poleward of 20°N. The monthly mean global average SST anomalies are removed to separate this pattern of variability from global warming.

Model and experiment descriptions

We use a collection of model ensembles with very different framings69: two multi-model ensembles from climate modelling experiments—one a regional climate model ensemble and one a coupled global circulation model ensemble—and three single model ensembles related to the FLOR model, one of which is an atmosphere-ocean coupled model, with the others being Sea Surface temperature (SST) driven global circulation models.

-

Coordinated Regional Climate Downscaling Experiment CORDEX-CORE South America (11 models with 0.44° resolution (SAM-44) and 3 models at 0.22° resolution (SAM-22)) multi-model ensemble70,71, comprising 14 simulations resulting from pairings of Global Climate Models (GCMs) and Regional Climate Models (RCMs)). These simulations are composed of historical simulations up to 2005 and extended to the year 2100 using the RCP8.5 scenario.

-

CMIP6. This consists of simulations from 13 participating models with varying resolutions. For more details on CMIP6, please see ref. 72. For all simulations, the period 1850 to 2015 is based on historical simulations, while the SSP5-8.5 scenario is used for the remainder of the 21st century.

-

The FLOR73 and AM2.5C36074,75 climate models are developed at Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL). The FLOR model is an atmosphere-ocean coupled GCM with a resolution of 50 km for land and atmosphere and 1° for ocean and ice. Ten ensemble simulations from FLOR are analysed, which cover the period from 1860 to 2100 and include both the historical and RCP4.5 experiments driven by transient radiative forcings from CMIP576. AM2.5C360 is an atmospheric GCM based on the FLOR model75,77 with a horizontal resolution of 25 km. Three ensemble simulations of the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP) experiment (1871–2100) are analysed. Radiative forcings are using historical values over 1871–2014 and RCP4.5 values after that. Simulations are initialised from three different pre-industrial conditions but forced by the same SSTs from HadISST178 after groupwise adjustments74 over 1871–2020. SSTs between 2021 and 2100 are from the FLOR RCP4.5 experiment 10-ensemble mean values after bias correction.

Statistical methods

In this study, we analyse time series from Rio Grande do Sul of March–May maxima of 4-day accumulated precipitation where long records of observed data are available. Methods for observational and model analysis and for model evaluation and synthesis are used according to the World Weather Attribution (WWA) Protocol, described in ref. 69, with supporting details found in refs. 79,80.

The analysis steps include: (i) trend calculation from observations; (ii) model validation; (iii) multi-method multi-model attribution and (iv) synthesis of the attribution statement. We calculate the return periods, Probability Ratio (PR; the factor-change in the event’s probability) and change in intensity (∆I, the change in magnitude of the metric between the two reference states) of the event under study in order to compare the climate of now and the climate of the past, defined respectively by the GMST values of 2024 and of the preindustrial past (1850–1900, based on the Global Warming Index – https://www.globalwarmingindex.org/).

To statistically model changes in the likelihood and intensity of the event under study, we fit a nonstationary distribution with one or more covariates including GMST. In the rapid study, a generalised extreme value (GEV) distribution that scales with GMST and the El-Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) was used. The latter is represented by the relative Niño3.4 index, averaged over the December-February (DJF) period to capture the typical peak of the oscillation.

Here, the GEV, Gumbel and Gaussian distributions are fit to each observational time series, along with covariates of GMST only, and both GMST and the DJF Niño index. The statistical models are as follows:

The variable of interest, \(X\), may be assumed to follow a GEV distribution in which the location and scale parameters vary with both GMST and ENSO:

where \(X\) denotes the variable of interest, rainy-season maximum 4-day precipitation; \(T\) is the smoothed GMST; I is the detrended Niño3.4 index; \({\mu }_{0}\), \({\sigma }_{0}\) and \(\xi\) are the location, scale and shape parameters of the nonstationary distribution; and \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) are the trends due to GMST and ENSO, respectively. As a result, the location and scale of the distribution have a different value in each year, determined by both the GMST and Niño3.4 states. Maximum likelihood estimation is used to estimate the model parameters, with

Then, the Gumbel distribution is just this formulation with the shape parameter equal to zero, such that

This assumption simplifies the model by reducing the number of fit parameters but requires testing.

Similarly, the variable of interest, \(X\), may be assumed to follow a normal distribution in which the location and scale parameters vary with both GMST and ENSO:

where \(X\) denotes the variable of interest, rainy-season precipitation; \(T\) is the smoothed GMST; I is the detrended Niño3.4 index; μ0 and σ0 are the mean and variance parameters of the nonstationary distribution; and α, β are the trends due to GMST and ENSO, respectively. The location and scale parameters follow Eq. (2).

For all statistical models described above, the distribution is assumed to scale exponentially with the covariates, with the dispersion (the ratio between the standard deviation and the mean) remaining constant over time. This formulation for the scale and location parameters (the ‘scale’ assumption) reflects the Clausius-Clapeyron relation, which implies that precipitation scales exponentially with temperature81,82, and so that precipitation will scale exponentially with the strength of the detrended Niño3.4 index. Other formulations are tested in Table 4, including the ‘shift’ assumption, in which the location parameter shifts linearly with GMST, and the combination of both assumptions, ‘shift & scale’. The shift formulation is as follows:

And the shift & scale formulation is given by:

Under all of these models, the effects of GMST and the detrended Niño3.4 index are assumed to be independent of one another, so that the change in intensity due to GMST is unaffected by the change in intensity due to the ENSO phase. We note that this may not be the case in the real world, as the intensity and frequency of El Niño events may have been influenced by climate change14; however, by using a detrended Niño3.4 index, we aim to minimise the correlation between the two factors, and so do not expect the qualitative findings of this study to be affected by this simplifying assumption.

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is used to determine the relative goodness of fit for different parametrisations, distributions and covariate combinations, while penalising more complex models to avoid overfitting. Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7 show the AIC scores for each time series with different distributions and covariates.

First, across almost all time series and distributions, fitting a statistical model using both GMST and this ENSO index as covariates gives an improved fit, according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), than GMST alone, which holds true whether or not the event is included in the fit (Table 5 and 6). The addition of the PDO also does not improve the fit compared to either GMST alone or GMST and ENSO (Table 7). The influence of the current (DJF) El Niño is therefore considered throughout this study.

Second, the various distributions perform differently depending on whether or not the event is included in the analysis, and for models and observations/reanalysis. When the event is included in the time series (Table 5), the Gaussian distribution performs the best, with GEV and Gumbel distributions similarly ranked overall. Inspecting the respective return level plots visually helps to highlight its performance across different regions of the distribution, which clearly shows that while the Gumbel distribution fits more of the data well, it performs very poorly at the tail of the distribution where the event lies (Fig. 9), while the Gaussian and GEV distributions capture this region more closely (Fig. 5 and 10). This is confirmed by repeating the same fit assessment but without the 2024 event. When the event is removed, the Gumbel distribution performs worst among the distributions by a substantial margin (Table 6) and is therefore not used in the analysis. Meanwhile, the Gaussian distribution performs best overall for observational and reanalysis datasets, but the GEV distribution performs better for the model data, and both are reasonably close (Table 6). As result, the analysis in the main body of the study uses the GEV, while the results of the Gaussian are shown in the supplementary material (Tables S3 and 4). This helps to test how sensitive the results (both qualitative and quantitative) are to the choice of statistical model.

a CPC, b MSWEP, c CHIRPS, d GPCC, e BR-DWGD, f BR-DWGD (from 1979–onwards), in the current climate and scaled to a climate without anthropogenic warming, modelled using a Gumbel distribution. The observed event is shown by the highest red dot and the purple line labelled as the ‘observed event’ represents the 1 in 100-year event used in this analysis.

a CPC, b MSWEP, c CHIRPS, d GPCC, e BR-DWGD, f BR-DWGD (from 1979–onwards), in the current climate and scaled to a climate without anthropogenic warming, modelled using a Gaussian distribution. The observed event is shown by the highest red dot and the purple line labelled as the ‘observed event’ represents the 1 in 100-year event used in this analysis.

The multi-method multi-model attribution step of the WWA protocol involves estimating, for each climate model, the effective return level of a 1-in-n-year event under the current climate state and estimating the expected change in likelihood and intensity of such an event after a specified change in the covariates. Because the smoothed GMST is generally monotonically increasing, the standard WWA approach is simply to take the model’s 2024 GMST as a covariate and to estimate the expected magnitude of an n-year event. However, the factual climate in this study is defined by the 2024 GMST and by the mean of the detrended DJF Niño3.4 index. During the attribution step, the detrended Niño3.4 index derived from the climate model is standardised so that the subset from 1990–2020 has mean 0 and variance 1; the ‘factual’ climate is then defined as having the model’s 2024 GMST and the 2024 observed value of the detrended Niño3.4 index, standardised in the same way. This removes any potential biases in the results due to differences between the amplitude of the modelled Niño3.4 index and that observed.

Multi-model attribution

In this section, we show the results of the model evaluation for the study region of Rio Grande do Sul and surrounding region of southeastern South America. The climate models are evaluated against the observations in their ability to capture:

-

1.

Seasonal cycles: we qualitatively compare the seasonal cycles based on model outputs against observationally-based cycles. We discard the models that exhibit multi-modality and/or ill-defined peaks in their seasonal cycles (see appendix Figs. S7–S9 for seasonal cycles).

-

2.

Spatial patterns: we qualitatively compare the spatial patterns based on model outputs against observationally-based patterns. Models that do not match the observations in terms of the large-scale precipitation patterns are excluded (see Appendix Figs. S4–S6 for spatial patterns).

-

3.

Parameters of the fitted GEV models (dispersion and shape parameters). We discard the model if the model and observation parameter ranges do not overlap.

-

4.

Correlation between March-May precipitation extremes and the detrended Niño3.4 index. We discard the model if the model and observation parameter ranges do not overlap.

The models are labelled as ‘good’, ‘reasonable’, or ‘bad’ based on their performances in terms of the four criteria discussed above. We evaluate 13 models from CORDEX and 11 models from CMIP6, as well as 3 runs of the AM2 model and 10 runs of the FLOR model.

All CMIP6 models, two out of three AM2 and seven out of ten FLOR models ensemble members, and all except for two CORDEX models pass the evaluation criteria as ‘reasonable’, with no models classified as ‘good’ (highlighted in yellow in Table S2). All models were found to be ‘good’ or ‘reasonable’ at reproducing the observed Niño3.4 correlations (not shown in Table S2).

The synthesis procedure used here has been peer-reviewed27 and works as follows. Before combining the different lines of evidence from observational and reanalysis datasets and climate models into a synthesised assessment, various sources of error are taken into consideration. First, a representation error is added (in quadrature) to the observations, to account for the difference between observations-based datasets that cannot be explained by natural variability. This is shown in these figures as white boxes around the light blue bars. The dark blue bar shows the average over the observation-based products. Next, a term to account for inter-model spread is added (in quadrature) to the natural variability of the models. This is shown in the figures as white boxes around the light red bars. The dark red bar shows the model average, consisting of a weighted mean using the (uncorrelated) uncertainties due to natural variability plus the term representing inter-model spread (i.e., the inverse square of the white bars). For the AM2 and FLOR ensembles, these individual ensemble members were first synthesised (using the same method) into a single result before being included in the wider synthesis.

For the final synthesis, results from observation-based products and models (Table 6) are combined into a single result in two ways. Firstly, we neglect common model uncertainties beyond the inter-model spread that is depicted by the model average and compute the weighted average of models (dark red bar) and observations (dark blue bar): this is indicated by the magenta bar. As, due to common model uncertainties, model uncertainty can be larger than the inter-model spread, secondly, we also show the more conservative estimate of an unweighted, direct average of observations (dark red bar) and models (dark blue bar) contributing 50% each, indicated by the white box around the magenta bar in the synthesis figures.

Data availability

The data used for this analysis and to produce all figures is available publicly at https://github.com/BenJClarke18/Brazil_floods_2024 and https://zenodo.org/records/17855714.

Code availability

The code used for this analysis and to produce all figures is available publicly at https://github.com/BenJClarke18/Brazil_floods_2024 and https://zenodo.org/records/17855714. General underlying code for conducting probabilistic event attribution analysis is also available at https://github.com/WorldWeatherAttribution/rwwa.

References

Porto Alegre experiences its rainiest start to May in 60 years, according to Climatempo. G1 https://g1.globo.com/rs/rio-grande-do-sul/noticia/2024/05/12/porto-alegre-tem-inicio-de-maio-mais-chuvoso-em-115-anos-diz-climatempo.ghtml (2024).

Brazil: Rio Grande do Sul Flood Emergency: Snapshot #4 As of 07 July 2024 - Brazil | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/brazil/brazil-rio-grande-do-sul-flood-emergency-snapshot-4-07-july-2024 (2024).

Trancoso, R., Flores, B. M. & Chapman, S. Deadlier natural disasters—a warning from Brazil’s 2024 floods. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 041001 (2025).

Maps. https://erccportal.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ECHO-Products/Maps#/maps/4868 (2024).

Velleda, L. Poor neighborhoods were the most affected by the flooding in the capital and metropolitan region. Sul 21 https://sul21.com.br/noticias/geral/2024/05/bairros-pobres-foram-os-mais-atingidos-pela-enchente-na-capital-e-regiao-metropolitana/ (2024).

Taschetto, A. S. et al. ENSO atmospheric teleconnections. In El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate 309–335, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119548164.ch14 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2020).

Teixeira, M. S. & Satyamurty, P. Dynamical and Synoptic characteristics of heavy rainfall episodes in Southern Brazil. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR3302.1 (2007).

Teixeira, M. da S. & Satyamurty, P. Trends in the frequency of intense precipitation events in Southern and Southeastern Brazil during 1960–2004. https://doi.org/10.1175/2011JCLI3511.1(2011).

Luiz-Silva, W. An overview of precipitation climatology in Brazil: space-time variability of frequency and intensity associated with atmospheric systems. Hydrol. Sci. J. 66, 289–308 (2021). Oscar-Júnior, Antonio Carlos, Cavalcanti, Iracema Fonseca Albuquerque & and Treistman, F.

Carvalho, L. M. V., Jones, C. & Liebmann, B. The South Atlantic Convergence Zone: intensity, form, persistence, and relationships with intraseasonal to interannual activity and extreme rainfall. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/clim/17/1/1520-0442_2004_017_0088_tsaczi_2.0.co_2.xml (2004).

Marengo, J. A., Soares, W. R., Saulo, C. & Nicolini, M. Climatology of the low-level Jet East of the Andes as derived from the NCEP–NCAR reanalyses: characteristics and temporal variability. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/clim/17/12/1520-0442_2004_017_2261_cotlje_2.0.co_2.xml (2004).

Fleischmann et al. The great 1983 floods in South American large rivers: a continental hydrological modelling approach. Hydrol. Sci. J. 65, 1358–1373 (2020).

Ávila, A., Justino, F., Wilson, A., Bromwich, D. & Amorim, M. Recent precipitation trends, flash floods and landslides in southern Brazil. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 114029 (2016).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño–Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Chagas, V. B., Chaffe, P. L., & Blöschl, G. Climate and land management accelerate the Brazilian water cycle. Nat. Commun. 13, 5136. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-022-32580-x (2022).

Fernandes, L. G. & Rodrigues, R. R. Changes in the patterns of extreme rainfall events in southern Brazil. Int. J. Climatol. 38, 1337–1352 (2018).

02 South Brazil Floods https://www.climameter.org/20240502-south-brazil-floods ClimaMeter—2024/05/.

Over the last three decades, the South has recorded an increase of up to 30% in average annual rainfall. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais. https://www.gov.br/inpe/pt-br/assuntos/ultimas-noticias/nas-ultimas-tres-decadas-sul-registra-aumento-de-ate-30-na-precipitacao-media-anual.

Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (2023).

Zaninelli, P. G., Menéndez, C. G., Falco, M., López-Franca, N. & Carril, A. F. Future hydroclimatological changes in South America based on an ensemble of regional climate models. Clim. Dyn. 52, 819–830 (2019).

Jeferson de Medeiros, F., Prestrelo de Oliveira, C. & Avila-Diaz, A. Evaluation of extreme precipitation climate indices and their projected changes for Brazil: from CMIP3 to CMIP6. Weather Clim. Extrem. 38, 100511 (2022).

Almazroui, M. et al. Assessment of CMIP6 performance and projected temperature and precipitation changes over South America. Earth Syst. Environ. 5, 155–183 (2021).

Alves, L. M., Chadwick, R., Moise, A., Brown, J. & Marengo, J. A. Assessment of rainfall variability and future change in Brazil across multiple timescales. Int. J. Climatol. 41, E1875–E1888 (2021).

Climate change, El Niño and infrastructure failures behind massive floods in southern Brazil – World Weather Attribution. World Weather Attribution https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-made-the-floods-in-southern-brazil-twice-as-likely/ (2024).

Environment, U. N. Emissions Gap Report 2024 | UNEP - UN Environment Programme. https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024 (2024).

Newman, M. et al. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation, Revisited. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0508.1 (2016).

Otto, F. E. L. et al. Formally combining different lines of evidence in extreme-event attribution. Adv. Stat. Climatol. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 10, 159–171 (2024).

Montini, T. L., Jones, C. & Carvalho, L. M. V. The South American low-level jet: a new climatology, variability, and changes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 124, 1200–1218 (2019).

Torres-Alavez, J. A. et al. Future projections in the climatology of global low-level jets from CORDEX-CORE simulations. Clim. Dyn. 57, 1551–1569 (2021).

Reboita, M. S. et al. Future projections of extreme precipitation climate indices over South America based on CORDEX-CORE multimodel ensemble. Atmosphere 13, 1463 (2022).

Blázquez, J. & Silvina, A. S. Multiscale precipitation variability and extremes over South America: analysis of future changes from a set of CORDEX regional climate model simulations. Clim. Dyn. 55, 2089–2106 (2020).

Shepherd, T. G. et al. Storylines: an alternative approach to representing uncertainty in physical aspects of climate change. Clim. Change 151, 555–571 (2018).

Mastrandrea, M. D. et al. The IPCC AR5 guidance note on consistent treatment of uncertainties: a common approach across the working groups. Clim. Change 108, 675 (2011).

Redator. Núcleo Porto Alegre analisa os impactos das enchentes na população pobre e negra do Rio Grande do Sul. Observatório das Metrópoles https://www.observatoriodasmetropoles.net.br/nucleo-porto-alegre-analisa-os-impactos-das-enchentes-na-populacao-pobre-e-negra-do-rio-grande-do-sul/ (2024).

Floods have affected 3000 health care units in Rio Grande do Sul-Brazil | ReliefWeb. ReliefWeb https://reliefweb.int/report/brazil/floods-have-affected-3000-health-care-units-rio-grande-do-sul (2024).

Rains in Rio Grande do Sul have affected 8000 indigenous people. Agência Brasil https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/en/geral/noticia/2024-05/rains-rio-grande-do-sul-have-affected-8000-indigenous-people (2024).

Dourado, M. Floods have already affected more than 80 indigenous communities in Rio Grande do Sul; find out how to help. | CIMI. https://cimi.org.br/2024/05/indigenascheiars/ (2024).

ABRHidro - ANAIS - Preliminary Application of the MGB-IPH Hydrological Model for the Analysis of the Extreme Flood Event of 1941 in the State of Rio Grande do Sul. https://anais.abrhidro.org.br/job.php?Job=3761 (2018).

Possa, T. M., Collischonn, W., Jardim, P. F. & Fan, F. M. Hydrological-hydrodynamic simulation and analysis of the possible influence of the wind in the extraordinary flood of 1941 in Porto Alegre. RBRH 27, e29 (2022).

Allasia, D. G., Tassi, R., Bemfica, D. & Goldenfum, J. A. Decreasing flood risk perception in Porto Alegre – Brazil and its influence on water resource management decisions. In Proceedings of IAHS. vol. 370 189–192 (Copernicus GmbH, 2015).

Brazil, D.-L. City Hall’s responsibility for the Porto Alegre catastrophe. De-Linking Brazil https://bmier.substack.com/p/city-halls-responsibility-for-the (2024).

Prizibisczki, C. Rio Grande do Sul has lost 22% of its vegetation cover in recent decades. ((o))eco https://oeco.org.br/reportagens/rio-grande-do-sul-perdeu-22-de-sua-cobertura-vegetal-nas-ultimas-decadas/ (2024).

Oliveira, E. Rain in Rio Grande do Sul: what do the muddy waters that sweep everything away signal? ((o))eco https://oeco.org.br/reportagens/chuvas-no-rio-grande-do-sul-o-que-as-aguas-barrentas-que-tudo-arrastam-sinalizam/ (2024).

Etchelar, C. B., Gruber, N. L. S. & Brenner, V. C. The impacts caused by drainage channels in wetlands of the Gravataí River. – Rio Grande do Sul - Brasil e na praia da Coronilha – Rocha – Uruguai. Seven Ed. https://sevenpublicacoes.com.br/index.php/editora/article/view/3626 (2023).

Temporais No RS: Civil Defense issues ‘express guidance’ for evacuation of at-risk areas in the Taquari Valley. G1 https://g1.globo.com/rs/rio-grande-do-sul/noticia/2024/05/01/temporais-no-rs-defesa-civil-vale-do-taquari.ghtml (2024).

Rio Grande do Sul has issued a warning for heavy rain, lightning, and the risk of flooding, according to Civil Defense. G1 https://g1.globo.com/rs/rio-grande-do-sul/noticia/2024/04/22/rs-tem-alerta-para-chuvas-fortes-descargas-eletricas-e-risco-de-alagamentos-diz-defesa-civil.ghtml (2024).

Sornette, D. & Ouillon, G. Dragon-kings: mechanisms, statistical methods and empirical evidence. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 205, 1–26 (2012).

Tragedy in Rio Grande do Sul: difference between flood, inundation, and flooding. Brasil Escola https://brasilescola.uol.com.br/noticias/tragedia-no-rs-entenda-a-diferenca-entre-enchente-inundacao-e-alagamento/3131313.html.

Floods in Rio Grande do Sul: what caused the 1941 flood in Porto Alegre—and why it is not an argument to deny climate change. BBC News Brasil https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/articles/cv27272zd79o (2024).

Diplomat, T. W. Historic floods in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. The Water Diplomat https://www.waterdiplomat.org/story/2024/05/historic-floods-brazilian-state-rio-grande-do-sul (2024).

Stocks, C. Dam of 14 de Julho power plant in Brazil partially collapses. International Water Power https://www.waterpowermagazine.com/news/dam-of-14-de-julho-power-plant-in-brazil-partially-collapses-fatalities-reported-11737530/ (2024).

Death toll from southern Brazil rainfall rises to 78 with many missing | Floods News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2024/5/6/death-toll-from-southern-brazil-rainfall-rises-with-many-still-missing.

‘Desperate’ rescues under way as Brazil floods kill 90, displace thousands | Floods News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/5/7/desperate-rescues-under-way-as-brazil-floods-kill-90-displace-thousands (2024).

Fato, B. de. Death toll from floods in Rio Grande do Sul rises to 90, affecting more than 1 million people. Peoples Dispatch https://peoplesdispatch.org/2024/05/07/death-toll-from-floods-in-rio-grande-do-sul-rises-to-90-affecting-more-than-1-million-people/ (2024).

Egas, H. M. et al. Comprehensive inventory and initial assessment of landslides triggered by autumn 2024 rainfall in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Landslides 22, 579–589 (2025).

Brazil, Porto Alegre–Salgado Filho International Airport reopened today. https://www.avionews.it/item/1260689-brazil-porto-alegre-salgado-filho-international-airport-reopened-today.html (2024).

Floods in Brazil’s Rio Grande do Sul state disrupt supply chain. S&P Global Market Intelligence https://www.spglobal.com/market-intelligence/en/news-insights/research/floods-in-brazils-rio-grande-do-sul-state-disrupt-supply-chain (2024).

Brazil: Unprecedented floods in Rio Grande do Sul threaten Brazil’s agricultural output (May 16, 2024) - Brazil | ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/brazil/brazil-unprecedented-floods-rio-grande-do-sul-threaten-brazils-agricultural-output-may-16-2024 (2024).

2024 Rio Grande do Sul Brazil Floods. Center for Disaster Philanthropy https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disasters/2024-rio-grande-do-sul-brazil-floods/ (2024).

MapBiomas Brasil. https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/en/2023/10/20/em-38-anos-o-brasil-perdeu-15-de-suas-florestas-naturais/.

Martinbiancho, G. K. et al. Preliminary application of the MGB-IPH hydrological model for the analysis of the extreme flood event in 1941 in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Beck, H. E. et al. MSWEP V2 Global 3-Hourly 0.1° Precipitation: Methodology and Quantitative Assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 473–500 (2019).

Funk, C. et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data 2, 150066 (2015).

Markus, Z. et al. GPCC Full Data Daily Version 2022 at 1.0°: Daily Land-Surface Precipitation from Rain-Gauges built on GTS-based and Historic Data: Globally Gridded Daily Totals. approx. 25 MB per gzip file Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC, http://gpcc.dwd.de/) at Deutscher Wetterdienst https://doi.org/10.5676/DWD_GPCC/FD_D_V2022_100 (2022).

Xavier, A. C., Scanlon, B. R., King, C. W. & Alves, A. I. New improved Brazilian daily weather gridded data (1961–2020). Int. J. Climatol. 42, 8390–8404 (2022).

Hansen, J., Ruedy, R., Sato, M. & Lo, K. Global surface temperature change. Rev. Geophys. 48 (2010).

Lenssen, N. J. L. et al. Improvements in the GISTEMP Uncertainty Model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 6307–6326 (2019).

van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Defining El Niño indices in a warming climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 044003 (2021).

Philip, S. et al. A protocol for probabilistic extreme event attribution analyses. Adv. Stat. Climatol. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 6, 177–203 (2020).

Giorgi, F., Coppola, E., Teichmann, C. & Jacob, D. Editorial for the CORDEX-CORE Experiment I Special Issue. Clim. Dyn. 57, 1265–1268 (2021).

Giorgi, F. Regional Dynamical Downscaling and the CORDEX Initiative. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 40, 467–490 (2015). & Jr, W. J. G.

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Vecchi, G. A. et al. On the seasonal forecasting of regional tropical cyclone activity. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00158.1 (2014).

Chan, D., Vecchi, G. A., Yang, W. & Huybers, P. Improved simulation of 19th- and 20th-century North Atlantic hurricane frequency after correcting historical sea surface temperatures. Sci. Adv. 7, (2021).

Yang, W., Hsieh, T.-L. & Vecchi, G. A. Hurricane annual cycle controlled by both seeds and genesis probability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 118, e2108397118 (2021).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An Overview of CMIP5 and the Experiment Design. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00094.1 (2012).

Delworth, T. L. et al. Simulated climate and climate change in the GFDL CM2.5 high-resolution coupled climate model. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00316.1 (2012).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108 (2003).

van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Pathways and pitfalls in extreme event attribution. Clim. Change 166, 13 (2021).

Ciavarella, A. et al. Prolonged Siberian heat of 2020 almost impossible without human influence. Clim. Change 166, 9 (2021).

Trenberth, K. E., Dai, A., Rasmussen, R. M. & Parsons, D. B. The changing character of precipitation. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-84-9-1205 (2003).

O’Gorman, P. A. & Schneider, T. The physical basis for increases in precipitation extremes in simulations of 21st-century climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 14773–14777 (2009).

Stein, A. F. et al. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 2059–2077 (2015).

Mantua, N. J., Hare, S. R., Zhang, Y., Wallace, J. M. & Francis, R. C. A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull Am. Meteor. Soc. 78, 1069–1079 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101003469.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.C., C.B., R.R., M.Z., L.A., and F.O. wrote the hazard sections of the manuscript. M.V., K.I., J.B., and M.M. collated the impacts and wrote/reviewed the vulnerability and exposure context. B.C. produced the figures, conducted data analysis and led all revisions. C.B and M.Z. provided data analysis support, and W.Y. provided additional model data. All authors, including R.H., I.P., G.V., J.K., S.P., and S.K., were involved in study conception and reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Clarke, B., Barnes, C., Rodrigues, R. et al. Climate change and El Niño behind extreme precipitation leading to major floods in southern Brazil in 2024. npj Nat. Hazards 3, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00162-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00162-8