Abstract

Eosinophils are the predominant immune cells implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma, highlighting the need for strategies to mitigate their effects. While previous studies have implicated the importance of lysosomes in eosinophil function, the precise role of lysosomes in eosinophil activation during asthma remains insufficiently understood. In this study, we demonstrate that lysosomal acidity and cathepsin L activity in eosinophils are elevated in asthmatic patients and mouse models. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of cathepsin L in eosinophils attenuates allergic airway inflammation in vivo and suppresses eosinophil activation in vitro. Cathepsin L in eosinophils promotes type 2 immune responses by upregulating arginase 1 expression and interacting with it, thereby enhancing arginase 1 activity and altering arginine metabolism during eosinophil activation. This metabolic shift leads to increased production of ornithine, which exacerbates inflammatory processes. Furthermore, lysosomal acidity and cathepsin L activity correlate with disease severity in asthmatic patients. Our findings implicate that lysosomal acidity and cathepsin L facilitate eosinophil activation through arginine metabolism, thereby promoting allergic airway inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma is a prevalent chronic respiratory disease characterized by persistent airway inflammation and recurrent episodes of breathlessness, wheezing, chest tightness, and coughing1. In 2019, asthma affected an estimated 262.4 million people worldwide and caused 455,000 deaths2. Eosinophils, a type of white blood cell, play a critical role in the immune response. Eosinophilia in blood and tissues is a hallmark of allergic inflammation and asthma, closely associated with increased production of type 2 (T2) cytokines, such as interleukin (IL) 4, IL5, and IL133. Eosinophils originate in the bone marrow and, once recruited by chemoattractants into airway tissues, respond to local stimuli such as Immunoglobulin E (IgE) or cytokines released by other inflammatory cells. Upon activation, eosinophils release inflammatory mediators, thereby exacerbating asthma symptoms. Additionally, eosinophils can directly damage airway tissues by releasing enzymes and oxidative agents, further contributing to inflammation and worsening asthma pathophysiology4. Given their pivotal role in the pathogenesis of asthma, targeting eosinophils has emerged as a significant therapeutic approach. However, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying eosinophil activation during immune responses in asthma remains limited.

Lysosomes are membrane-bound organelles containing a diverse array of hydrolytic enzymes that degrade proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides. The lysosome’s outer membrane consists of a single phospholipid bilayer decorated with transmembrane proteins, most notably lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP) 1 and LAMP25,6. Another crucial protein present on the lysosomal membrane is vacuolar H+-ATPase (v-ATPase), which hydrolyzes adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to transport protons into lysosomes, thereby maintaining an acidic internal pH, typically ranging between 4.5 and 5.0. This acid environment is optimal for the activity of luminal hydrolases7. Transcriptomic data from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) indicate that RNA expression of LAMP1, LAMP2, LAMP3, and v-ATPases is enriched in granulocytes, particularly eosinophils. Moreover, LAMP1, LAMP2, and v-ATPases are present in eosinophil granules, and activation of eosinophils by IL5 results in the acidification of specific granules8,9,10. These findings suggest a crucial role for lysosomes in eosinophil activation. Lysosomes are essential organelles involved in degradation processes, immunity, and nutrient sensing11. Furthermore, lysosomes are implicated in the progression of various pulmonary diseases12,13. However, the function of lysosomes in eosinophil activation during asthma remains unclear.

Lysosomal function depends on the coordinated activity of various components, including lysosomal hydrolases, which operate optimally within the acidic environment of the endolysosomal compartment. In an appropriate acidic environment, proteases are cleaved into mature forms and exert their function. Among these hydrolases, cathepsins are particularly prominent, with diverse functions ranging from antimicrobial activity to antigen presentation. Specifically, cathepsin L (CTSL), a cysteine protease, plays pivotal roles in antigen presentation, extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, inflammatory diseases, and tumor progression14,15. Recent studies have highlighted the involvement of CTSL in the pathogenesis of pulmonary diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)16, pulmonary fibrosis17, and viral infections such as COVID-1918. Given the critical role of CTSL in maintaining immune homeostasis, targeting CTSL in specific cell types during allergic diseases may represent a promising therapeutic strategy.

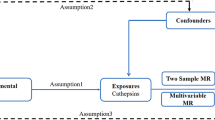

The present study aims to explore the role of lysosomes in eosinophil activation during asthma by examining lysosomal number, acidity, and cathepsins in activated eosinophils from mice and humans with asthma, as well as the airway inflammation in CTSL-impaired mice. We also provide evidence that CTSL in activated eosinophils is mechanistically linked to arginase 1 (ARG1) activity and arginine metabolism. These results underscore the critical importance of the CTSL-ARG1-arginine metabolism pathway in eosinophil activation during asthma.

Results

Lysosomal function is enhanced during eosinophil activation

We initially noticed that lysosome-associated membrane proteins and v-ATPases are highly expressed in eosinophils within the HPA database (Supplementary Fig. 1A–D), indicating potential specific functions of lysosomes in eosinophils. To explore this further, we conducted a transcriptomic analysis of activated eosinophils19, with a particular focus on lysosomal function. Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of Cd3δ-Il5 transgenic (Il5 Tg) mice (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B) and stimulated with IL33, an alarmin secreted by airway epithelial cells in response to allergen exposure. IL33 is known to mediate T2 inflammation and can activate eosinophils20,21. Compared to controls, we observed a decrease in primary lysosomes and an increase in secondary lysosomes in activated eosinophils (Fig. 1A). Primary lysosomes contain hydrolytic enzymes in an inactive form. Upon encountering substrates, these lysosomes fuse with other vesicles to form secondary lysosomes, wherein the enzymes become active and facilitate digestion. Thus, this transcriptomic analysis indicated potential abnormalities in lysosomal function during eosinophil activation.

A–H Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of Il5 Tg mice. A Gene Ontology (GO)-based gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of eosinophils treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h (Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic, 1000 permutations, two-sided; P values adjusted by FDR). B, C Acidity of lysosomes in eosinophils treated with IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 0, 2, 4, and 8 h (n = 3 biological replicates). Scale bars, 10 μm. D Protein expression of V-ATPase H, V-ATPase D, and Cathepsin L (CTSL) in eosinophils treated with IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 0, 2, 4, and 8 h. E CTSL enzyme activity in eosinophils treated with IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 0, 2, 4, and 8 h (n = 3 biological replicates). F, G Lysosomal acidity and CTSL enzyme activity in eosinophils treated with IL33 (20 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of 0.5 µM KM91104, 10 nM Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), 100 nM Concanamycin A (Con. A) for 8 h (n = 3 biological replicates). H Protein expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in eosinophils treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h, and subsequently incubated with or without EGF (100 ng/ml). I, J Lysosomal acidity and CTSL enzyme activity in eosinophils isolated from peripheral blood of patients with asthma and treated with or without IL33 (100 ng/ml) for 8 h (n = 3 biological replicates). K, L Lysosomal acidity and CTSL enzyme activity in eosinophils from lung tissues of C57BL/6 mice after house dust mite (HDM) (n = 6 biological replicates) or saline (n = 5 biological replicates) intratracheal instillation. M Representative immunofluorescence images of eosinophil peroxidase (EPX, green), CTSL (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in lung tissues from HDM or saline-treated mice. Scale bars, 10 μm and 5 μm. Data presented are representative of three independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were calculated using one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (B, E, F, and G) and two-sided unpaired Student’s t test (I–L).

Then, we analyzed the number, acidity, and hydrolases of lysosomes in eosinophils. We observed no change in LAMP1 and LAMP2 expression upon activation (Supplementary Fig. 2C–G), whereas lysosomal acidity was found to be increased (Fig. 1B, C). Given the role of v-ATPases in maintaining an acidic pH, we measured and confirmed elevated expression of intracellular v-ATPases in activated eosinophils (Fig. 1D). Further analysis revealed a significant increase in mature CTSL levels, while the level of other lysosomal enzymes remained relatively stable (Fig. 1D, E, and Supplementary Fig. 2G). Exposure of eosinophils to a T2 cytokine cocktail (IL4, IL33, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) yielded comparable results to those observed with IL33 alone (Supplementary Fig. 3A–E). Inhibition of v-ATPase activity resulted in decreased lysosomal acidity and reduced CTSL activity during eosinophil activation (Fig. 1F, G), indicating that both v-ATPases and the lysosomal acidity are crucial for promoting CTSL activity in activated eosinophils. To clarify, treatment with the inhibitors described herein and below, as well as the deletion of Ctsl, did not induce degranulation (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B), cell death (Supplementary Fig. 4C, D), or eosinophil ETosis (Supplementary Fig. 4E–G). We further investigated lysosomal function by assessing the degradation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Under basal conditions, EGFR is localized on the cell surface. Upon EGF treatment, EGFR undergoes internalization and subsequent degradation. Notably, IL33-treated eosinophils exhibited enhanced EGFR degradation (Fig. 1H). Similarly, IL33-activated eosinophils derived from human peripheral blood (Supplementary Fig. 5A, B) exhibited enhanced lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity, without changes in LAMP1 and LAMP2 levels (Fig. 1I, J, and Supplementary Fig. 2H, I).

Furthermore, we examined alterations of eosinophil lysosomes in house dust mite (HDM) -induced mouse models of asthma (Supplementary Fig. 6A). Following HDM exposure, the number of eosinophils in lung tissue was increased significantly (Supplementary Fig. 6B, C). Consistent with the in vitro observations, LAMP1 and LAMP2 levels remained unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 2J, K), while lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity were notably increased in eosinophils (Fig. 1K–M).

It is worth noting that eosinophils from Il5 Tg mice are chronically exposed to high concentrations of IL5, which can regulate Siglec-F expression22. Therefore, we compared these eosinophils with those sorted from wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Interestingly, the data indicated that the secretion of T2 cytokines (IL4 and IL13) was increased in naïve eosinophils treated with a mix of IL33 and IL5, whereas little to no T2 cytokines were detected when stimulated with IL33 or IL5 alone (Supplementary Fig. 7B, C). However, substantial amounts of T2 cytokines were secreted upon IL33 stimulation alone in eosinophils from Il5 Tg mice (Supplementary Fig. 7D, E). Additionally, no notable differences were found in the secretion of IL4 and IL13 between naïve and Il5 Tg mouse-derived eosinophils under baseline conditions or following IL5 stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 7F, G). These findings demonstrate that eosinophils are activated by IL33 and further significantly enhanced under IL5 primed conditions. Similarly, lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity were elevated in naïve eosinophils under combination stimulation with IL5 and IL33 (Supplementary Fig. 7H, I). Therefore, due to the difficulty in isolating naïve eosinophils and the challenges associated with supporting large-scale in vitro experiments, we opted to used IL33 to activate eosinophils from Il5 Tg mice in subsequent experiments.

Taken together, these findings confirm that lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity are elevated in activated eosinophils during allergic airway inflammation.

Elevated lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity promote eosinophil activation

To investigate the role of lysosomal function in eosinophil activation, we assessed the expression and secretion of T2 cytokines, as well as the expression of CD69 and intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in IL33-stimulated eosinophils. Inhibition of v-ATPases reduced lysosomal acidity and significantly lowered IL4, IL13, CD69 and ICAM-1 levels under inflammatory conditions (Fig. 2A–D, and Supplementary Fig. 8A, B). Both E64D, a broad-spectrum cysteine protease inhibitor, and SID26681509, a selective CTSL inhibitor, suppressed the expression and secretion of T2 cytokines, as well as the expression of CD69 and ICAM-1 in activated eosinophils (Fig. 2E–L). Ctsl-deficient eosinophils (Ctsl flox/flox crossed with eoCre mice) (Supplementary Fig. 9A–C) also exhibited similar reductions following IL33 stimulation (Fig. 2M–P, and Supplementary Fig. 8C, D). Correspondingly, inhibition of lysosomal acidity or CTSL activity in activated human eosinophils led to decreased production of T2 cytokines (Fig. 2Q–T). However, selective inhibition of CTSB, CTSK, or CTSZ showed no effect on eosinophil activation (Supplementary Fig. 8E–J).

A–L Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of Il5 Tg mice and treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants for IL4 and IL13, and flow cytometry analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) for CD69 and intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression on eosinophils incubated with or without 100 nM Con. A (A–D), 50 µM E64D (E–H), and 50 µM SID26681509 (I–L). M–P Eosinophils were differentiated from bone marrow of sex-matched control and Ctsl eoΔ mice and treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants for IL4 (M) and IL13 (N), and flow cytometry analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) for CD69 (O) and ICAM-1 (P) expression on eosinophils. Q–T Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of patients with asthma and treated with or without IL33 (100 ng/ml) for 8 h. ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants from eosinophils incubated with or without 100 nM Con. A (Q and R), 50 µM SID26681509 (S and T) for IL4 and IL13. Data presented are representative of three independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

T2 cytokines induce the activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT1), and STAT623. The phosphorylation of STAT6, NF-κB p65 and IκBα was augmented in activated eosinophils (no band was detected for p-STAT1). Treatment with a CTSL inhibitor reduced p-STAT6 levels, with no significant changes in the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 and IκBα (Supplementary Fig. 10A). Furthermore, inhibition of STAT6 phosphorylation effectively downregulated the secretion of T2 cytokines, as well as the expression of CD69 and ICAM-1 in activated eosinophils (Supplementary Fig. 10B–E).

Collectively, these findings suggest that enhanced lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity may promote eosinophil activation, potentially through the STAT6 signaling pathway.

CTSL facilitates eosinophil activation in allergic airway inflammation in vivo

To further investigate the role of eosinophil CTSL in asthmatic airway inflammation, we developed an HDM mouse model using eosinophil-specific Ctsl-deficient mice. Deletion of Ctsl in eosinophils led to a significant reduction in the total cell counts and eosinophil counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (Fig. 3A), as well as a decrease in the expression of T2 cytokines Il4, Il5, and Il13 in lung tissues (Fig. 3B). Histological examination using Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining revealed a marked reduction in the infiltration of inflammatory cells and mucus secretion around the airways (Fig. 3C–F). Reduced airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) was also observed (Fig. 3G). Furthermore, intraperitoneal injection of SID26681509 to inhibit the CTSL activity in vivo significantly alleviated HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation and AHR (Fig. 3H–N). Notably, the absence of Ctsl had no effect on eosinophil development both at baseline and upon allergen provocation in the bone marrow (Supplementary Fig. 11A). Furthermore, neither Ctsl deficiency nor SID26681509 treatment impaired the development of bone marrow-derived eosinophils (Supplementary Fig. 11B, C) Thus, CTSL aggravates allergic airway inflammation by promoting eosinophil activation.

A–G Ctsl eoΔ mice and their littermate controls were intratracheally instilled with 100 µg of HDM on days 0, 7, and 14 (Control-NS, n = 4 biological replicates; Control-HDM, n = 5 biological replicates; Ctsl eoΔ-NS, n = 4 biological replicates; Ctsl eoΔ-HDM, n = 6 biological replicates). H–N C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally instilled with 100 µg of HDM on days 0, 7, and 14. SID26681509 was administered via intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 10 mg/kg on days 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 (Control-NS, n = 5 biological replicates; Control-HDM, n = 5 biological replicates; SID26681509-NS, n = 4 biological replicates; SID26681509-HDM, n = 6 biological replicates). A, H The count of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid from mice. B, I The mRNA levels of Il4, Il5, and Il13 in lung tissues analyzed by RT-qPCR. C, J Representative Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stained lung tissue sections from mice. Scale bars, 200 µm. D, K Histological inflammatory scores from H&E images. E, L Representative periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained lung tissue sections from mice. Scale bars, 100 µm. F, M PAS scores. G, N Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in response to methacholine. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

CTSL enhances the enzymatic activity of ARG1 during eosinophil activation

To further elucidate the detailed mechanisms by which CTSL promotes eosinophil activation, we conducted a transcriptomic analysis. The data revealed significant changes in the expression of 855 genes in eosinophils following IL33 stimulation, with 389 genes upregulated and 466 downregulated. Additionally, 854 genes were altered after treatment with SID26681509, with 488 genes upregulated and 366 downregulated. Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analyses revealed that these differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were predominantly associated with immune and defense responses, signal transduction, and metabolic processes (Supplementary Fig. 12A, B). Venn diagram analysis identified 212 DEGs that were commonly regulated by IL33 stimulation and subsequently reversed or modulated upon CTSL inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 12C). Notably, arginine metabolic processes were significantly enriched in IL33-stimulated eosinophils, and this enrichment was attenuated by SID26681509 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 12D). Further focused analysis revealed that among genes involved in arginine metabolism, only three were highly expressed in eosinophils (Supplementary Table 1), with Arg1 being the only gene whose expression pattern mirrored the observed metabolic changes. Specifically, Arg1 mRNA levels were significantly upregulated following IL33 stimulation and markedly reduced upon CTSL inhibition (Fig. 4A). ARG1 is a critical enzyme in the arginine metabolism pathway, which is known to be associated with asthma inflammation24,25,26. In IL33-stimulated eosinophils, ARG1 expression was increased, while it was markedly decreased upon treatment with SID26681509 or deletion of Ctsl (Fig. 4B–E). Elevated ARG1 levels were also observed in activated eosinophils from human samples and HDM-induced mouse models (Fig. 4F–H).

A–C, J, M Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of Il5 Tg mice and treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. A The volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in eosinophils incubated with or without 50 µM SID26681509 through RNA sequencing analysis. RT-qPCR (B) and immunoblotting (C) in eosinophils (n = 3 biological replicates) incubated with or without 50 µM SID26681509 for arginase 1 (ARG1). D, E Eosinophils were differentiated from bone marrow of sex-matched control and Ctsl eoΔ mice and treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. RT-qPCR (D) and immunoblotting (E) in eosinophils for ARG1 (n = 3 biological replicates). F ARG1 expression in eosinophils isolated from peripheral blood of patients with asthma and treated with or without IL33 (100 ng/ml) for 8 h (n = 3 biological replicates). G ARG1 expression in eosinophils from lung tissues of mice after HDM (n = 6 biological replicates) or saline (n = 5 biological replicates) intratracheal instillation. H Representative immunofluorescence images of EPX (green), ARG1 (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in lung tissues. Scale bars, 10 μm. I Representative immunofluorescence images of CTSL (green), ARG1 (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in eosinophils treated with IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 0, 2, 4, and 8 h. Scale bars, 5 μm and 3 μm. J Spatial approximation of CTSL with ARG1 by proximity ligation assay (PLA). Red, proximity ligation-positive signals. Negative control without primary antibodies. Scale bars, 2 μm. HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-labeled ARG1 and HA-labeled CTSL for 48 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag (K) or anti-HA (L) and subjected to immunoblotting. M Arginase activity in eosinophils with or without 50 µM SID26681509 (n = 3 biological replicates). N Arginase activity in eosinophils differentiated from bone marrow of sex-matched control and Ctsl eoΔ mice and treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h (n = 3 biological replicates). Data presented are representative of three independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

ARG1 predominantly localizes in the cytoplasm and intracellular granules27. We observed partial distribution of ARG1 within the lysosomes of eosinophils (Supplementary Fig. 13A). Immunofluorescence co-localization studies showed an increased intracellular distribution and partial co-localization of CTSL and ARG1 following IL33 stimulation in eosinophils (Fig. 4I). Additionally, proximity ligation assays (PLA) suggested a potential interaction between CTSL and ARG1 (Fig. 4J). To further investigate this interaction, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments using plasmids encoding hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged CTSL and Flag-tagged ARG1, which were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. The results showed that anti-HA antibodies immunoprecipitated Flag-ARG1, and anti-Flag antibodies immunoprecipitated HA-CTSL (Fig. 4K, L).

Besides, we observed increased arginase activity in IL33-stimulated eosinophils, which was reduced following the inhibition and knockdown of CTSL (Fig. 4M, N). Collectively, our data suggest that in activated eosinophils, CTSL promotes ARG1 expression and interacts with it, leading to elevated ARG1 enzymatic activity.

ARG1 enhances eosinophil activation in allergic airway inflammation

To investigate the role of ARG1 in eosinophil activation, we applied ARG1 inhibitors, nor-NOHA and BEC, to eosinophils in vitro. We first confirmed that these inhibitors effectively suppressed ARG1 activity (Fig. 5A). Then, we found that inhibition of ARG1 activity significantly reduced the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, as well as the expression of CD69 and ICAM-1 in IL33-stimulated eosinophils in vitro (Fig. 5B–E). Additionally, intratracheal administration of nor-NOHA markedly alleviated HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation in vivo (Fig. 5F–K). And nor-NOHA had no influence on bone marrow-derived eosinophil differentiation and maturation (Supplementary Fig. 14A). These results suggest that ARG1 positively regulates eosinophil activation, thereby exacerbating allergic airway inflammation.

A–E Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of Il5 Tg mice and treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. A Arginase activity in eosinophils with or without 20 µM nor-NOHA and 20 µM BEC (n = 3 biological replicates). B, C ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants from eosinophils incubated with or without 20 µM nor-NOHA and 20 µM BEC for IL4 (B) and IL13 (C). D, E Flow cytometry (n = 3 biological replicates) analysis for CD69 (D) and ICAM-1 (E) expression on eosinophils with or without 20 µM nor-NOHA and 20 µM BEC. F–K C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally instilled with 100 µg of HDM on days 0, 7, and 14. Saline or nor-NOHA was administered via intratracheal instillation at a dose of 4 mg/kg on days 14, 15, and 16 (Control-NS, n = 3 biological replicates; Control-HDM, n = 6 biological replicates; nor-NOHA-NS, n = 4 biological replicates; nor-NOHA-HDM, n = 6 biological replicates). F The count of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid from mice. G The mRNA levels of Il4, Il5, and Il13 in lung tissues analyzed by RT-qPCR. H Representative H&E stained lung tissue sections from mice. Scale bars, 200 µm. I Histological inflammatory scores from H&E images. J Representative PAS-stained lung tissue sections from mice. Scale bars, 100 µm. K PAS scores. Data presented are representative of three independent experiments shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

CTSL promotes eosinophil activation by enhancing arginine metabolism

To determine whether CTSL facilitates eosinophil activation through ARG1, we overexpressed ARG1 in eosinophils (Supplementary Fig. 15A). In IL33-stimulated eosinophils, ARG1 overexpression exacerbated cytokine secretion and reversed the anti-activation effects induced by CTSL inhibitor SID26681509 (Fig. 6A). Besides, treatment with recombinant ARG1 protein had similar effects on promoting eosinophil activation, which were blocked by the ARG1 inhibitor nor-NOHA (Fig. 6B). Recombinant ARG1 also reversed the protective effects observed in IL33-stimulated Cstl knockdown eosinophils (Fig. 6C, and Supplementary Fig. 15B). These data demonstrate that CTSL promotes eosinophil activation through an ARG1-dependent mechanism.

A, B, D–G Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of Il5 Tg mice and treated with or without IL33 (20 ng/ml) and 50 µM SID26681509 for 8 h. A ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants from eosinophils with or without ARG1 overexpression for IL4 and IL13. B ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants from eosinophils in the presence or absence of ARG1 protein (2 µg/ml) and 20 µM nor-NOHA for IL4 and IL13. C Eosinophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of control and Ctsl eoΔ Il5 Tg mice. ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants from eosinophils in the presence or absence of ARG1 protein. D, E Concentrations of arginine and ornithine in eosinophils (n = 5 biological replicates). F, G ELISA analysis (n = 3 biological replicates) of culture supernatants from eosinophils in the presence or absence of ornithine (5 mM). Data presented are representative of three independent experiments and shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Given the involvement of ARG1 in arginine metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 16A) and the enhanced arginine metabolic processes during eosinophil activation (Supplementary Fig. 12D), we further investigated changes in intracellular arginine and its metabolic products. Upon IL33 stimulation, eosinophils exhibited a marked decrease in intracellular arginine levels, accompanied by a significant increase in intracellular ornithine levels. (Fig. 6D, E). However, the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), as well as the levels of citrulline and nitric oxide (NO), remained unchanged (supplementary Fig. 16B–D). The downstream metabolites of ornithine, including proline, and polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine) also showed no significant changes (supplementary Fig. 16E–I). Consistent with the intracellular findings, plasma arginine levels were significantly lower in asthmatic patients compared to healthy controls (Supplementary Fig. 16J), whereas plasma ornithine levels were significantly elevated (Supplementary Fig. 16K). Nevertheless, citrulline levels showed no significant differences between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 16L).

Notably, treatment with SID26681509 restored intracellular ornithine levels in IL33-activated eosinophils to baseline (Fig. 6E). Supplementation with ornithine exacerbated cytokine secretion and reversed the protective effects of SID26681509 against eosinophil activation (Fig. 6F, G). Ornithine supplementation also partially reversed the effects of CTSL or ARG1 inhibitors on reducing STAT6 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 17A–C).

Collectively, these observations support that CTSL enhances arginine metabolism by increasing ARG1 activity, thereby promoting eosinophil activation.

Lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity correlate with asthma severity

Finally, to determine whether lysosomal function in eosinophils contributes to the severity of asthma, we examined LAMP1 and LAMP2 levels, lysosomal acidity, CTSL activity, and ARG1 levels in samples from two separate cohorts of asthmatic patients and healthy controls (Supplementary Table 2). Eosinophils were identified as SSC hi, Siglec-8+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 18A, B). The results revealed that eosinophils from asthmatic patients exhibited increased lysosomal acidity, CTSL activity, and ARG1 levels without alteration in LAMP1 and LAMP2 expression (Fig. 7A–E). Furthermore, we performed pulmonary function testing (Supplementary Table 2) on the patients and demonstrated that lysosomal acidity of eosinophils correlated inversely with forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) percent predicted and FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) (Fig. 7F, G). CTSL activity also showed an inverse correlation with FEV1 percent predicted and FEV1/FVC (Fig. 7H, I). Thus, eosinophil lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity may serve as indicators of asthma severity.

A–I Granulocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers (n = 13) and asthmatic patients (n = 23). Lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP) 1 (A) and LAMP2 (B) expression, lysosomes acidity (C), CTSL enzyme activity (D), and ARG1 expression (E) in eosinophils. Spearman correlations between lysosomal acidity and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) % pred (F), and FEV1/ forced vital capacity (FVC) (%) (G). Spearman correlations between CTSL enzyme activity and FEV1 % pred (H), and FEV1/FVC (%) (I). Data presented are shown as mean ± SEM (A–E). Statistical analyses were calculated using two-sided unpaired Student’s t test. Data are combined from two independent cohorts of asthmatic patients and healthy controls, with each individual sample representing a distinct biological replicate.

Discussion

Eosinophils are leukocytes characterized by their granule-containing structures, which have been identified as lysosome-like organelles8,9. The enrichment of lysosome-associated membrane proteins and v-ATPases in eosinophils underscores the potential significance of lysosomes in maintaining eosinophil function. Here, our study unveils that lysosomal acidity and CTSL play pivotal roles in eosinophil activation during allergic airway inflammation, and reveals that CTSL reshapes arginine metabolic homeostasis by enhancing ARG1 activity, thereby promoting eosinophil activation. Furthermore, lysosomal acidity and CTSL activity correlate with disease severity in individuals with asthma.

Lysosomal acidity is primarily maintained by proton pumps, particularly v-ATPases, which lower the internal pH by transporting protons into the lysosome7,28. Disruption of lysosomal acidity has been implicated in various inflammatory conditions. In mature dendritic cells (DCs), activation of the vacuolar proton pump enhances lysosomal acidification and promotes the formation of peptide-MHC class Ⅱ complexes29. Moreover, lysosomal acidification in DCs facilitates protease maturation and determines the cleavage and activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines30. In microglia, disruption of Transcription factor EB (TFEB)-v-ATPase signaling impairs lysosomal function and results in failure of microglial activation in tauopathy31. Similarly, our results indicate that lysosomal acidification promotes eosinophil activation by upregulating v-ATPases expression, thereby exacerbating airway inflammation in asthma.

Lysosomal acidification significantly impacts the activity of acidic hydrolases, including cathepsins, which are essential components and functional executors within lysosomes. Cathepsins regulate inflammatory processes and play a significant role in the immune response32,33,34. A recent study has shown that CTSB in macrophages mediates the activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome, contributing to systemic inflammation and severity of pancreatitis35. Elevated pulmonary concentrations and activity of CTSS can exacerbate acute respiratory distress syndrome36. Eosinophil-derived CTSL has also been shown to promote pulmonary matrix destruction and emphysema16. Notably, CTSL expression is downregulated in the airway epithelium of asthmatic patients37, and genome-wide association analyses reveal that increased ECP levels in asthmatic eosinophils are associated with decreased CTSL expression38. However, our observations challenge the role of CTSL in eosinophils among asthmatic patients, suggesting a need for further investigation into the function of CTSL in these cells. Through genetic knockout and selective inhibition of CTSL in eosinophils, we observed a pronounced suppression of eosinophil activation and attenuation of airway inflammation, underscoring the critical role of CTSL in regulating eosinophil activation in asthma.

Cathepsins are critical for various biological processes, including cell metabolism, protein degradation, and cleavage. Additionally, studies have shown that cathepsins modulate signaling pathways39. For instance, CTSB and CTSS can activate nuclear p65-NF-κB and NF-κB-dependent gene expression in LPS-challenged cells40. CTSS inhibition blocks the TLR2-mediated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway41. In our study, we demonstrate that CTSL promotes eosinophil activation by upregulating the enzymatic activity of ARG1. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the regulatory pathways through which CTSL modulates ARG1 expression. Traditionally, cathepsins have been recognized as proteolytic enzymes that primarily involved in protein degradation. However, recent research has revealed an alternative mechanism where CTSS interacts with and cleaves neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)-associated ARG1, thereby enhancing its enzymatic activity42. This suggests that cathepsins may possess diverse functional roles. Consistent with this, our findings indicate that CTSL enhances ARG1 activity by increasing its expression and interacting with it in lysosomes.

Increased ARG1 activity is linked to immune system dysfunction. Studies show that macrophages and neutrophils can inhibit T cell function by consuming arginine via ARG1, thereby regulating the immune response43,44. ARG1 activity within CD4+ T cells influences the kinetics of the T helper 1 (Th1) lifecycle and contributes to tissue pathology in influenza infection45. Moreover, ARG1 plays a key role in the polarization of macrophages and neutrophils46,47. Additionally, ARG1 has been implicated in the pathophysiology of asthma48. Elevated arginase activity contributes to decreased arginine levels, resulting in hyperreactive airways49,50. However, no studies have specifically examined the role of ARG1 in eosinophil activation during asthma. Our results show that ARG1 expression is upregulated in eosinophils from asthmatic patients or HDM-induced mice due to elevated CTSL activity, and that ARG1 contributes to eosinophil activation. Previous studies suggest that the expression of ARG1 is upregulated through IL4/IL13-STAT6 pathway and IL6/IL10/G-CSF-STAT3 pathway in macrophages51,52,53. These cytokines significantly affect the production of ARG1. Our study reveals that ARG1 can conversely enhance the expression and secretion of T2 cytokines in activated eosinophils. Inhibition of ARG1 markedly suppressed eosinophil activation in vivo and in vitro. Overexpression of ARG1 and recombinant protein intervention in eosinophils with CTSL knockout or inhibition further clarifies the regulatory role of CTSL on ARG1 in eosinophil activation.

Arginine metabolism plays a crucial role in modulating the inflammatory responses of various immune cells, including macrophages and T cells54,55. Notably, ARG1 is a key enzyme in the arginine metabolic pathway, converting arginine into ornithine and urea. In our study, IL33-activated eosinophils exhibited reduced intracellular arginine and increased ornithine levels, indicating enhanced ARG1 activity. Consistently, plasma from asthmatic patients showed decreased arginine and elevated ornithine levels compared to healthy controls. These parallel findings suggest that eosinophil ARG1 activity may contribute not only to local metabolic changes but also to systemic alterations in arginine metabolite levels. Moreover, the metabolite ornithine is believed to contribute to cell proliferation, collagen formation, and immune responses56. Specifically, ornithine has distinct roles in various inflammatory contexts. It enhances the production of anti-inflammatory factors in macrophages57. Elevated ornithine levels have been associated with the suppression of virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses58. Our findings further indicate that ornithine can promote eosinophil activation. Additionally, arginine can be converted into citrulline and NO via NOS. In our study, no changes in iNOS, citrulline, and NO levels were observed in activated eosinophils, suggesting that the regulation of arginine levels is primarily mediated by ARG1.

In conclusion, our findings elucidate a role of CTSL in promoting eosinophil activation by modulating arginine metabolism through elevated ARG1 activity. These insights highlight CTSL as a potential therapeutic target for managing asthmatic inflammation, warranting further exploration in clinical settings.

Methods

This study complies with all relevant animal procedures and ethical regulations. All human-related studies were approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Studies of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2022-1043). All animal experiments were strictly conducted following the protocols approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Studies at Zhejiang University, China.

Human study

Asthma diagnosis was conducted according to the Global Initiative on Asthma (GINA) guidelines1. We included asthmatic patients aged 18–70 years. Exclusion criteria included the presence of other respiratory diseases such as COPD, upper or lower respiratory tract infections, related symptoms, and lung cancer. A total of twenty-three asthmatic patients and thirteen healthy volunteers were recruited from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in the study. Participants received a small monetary stipend. The clinical characteristics of the participants are detailed in Supplementary Table 2. The information for gender was not statistically significant between disease and control groups.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ctsl flox/flox mice were generated by Cyagen (Jiangsu, China). Il5 Tg and Epx-Cre (eoCre) mice were gifts from the late Dr. J. J. Lee (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Mayo Clinic, USA). eoCre/Ctsl flox/flox mice were generated by crossing the Ctsl flox/flox mice with eoCre transgenic mice. Age- and sex-matched littermate animals (eoCre/Ctsl flox/flox and Ctsl flox/flox) were used in the experiments. All mice were on a C57BL/6 background and were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Laboratory Animal Center of Zhejiang University. The dark/light cycle was maintained at 12-h light/12-h dark. Ambient temperature was controlled at 20–25 °C, with relative humidity maintained at 30–70%. Mice were housed in individually ventilated cages, with no more than 5 mice in each cage, and could freely obtain food and water. The genotypes of the mice were confirmed by PCR analysis.

Animal models

C57BL/6 mice aged 8–10 weeks were used to establish asthma models, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6A. Intratracheal instillation of 100 µg of HDM extract dissolved in 50 µl of saline was administered to the mice on days 0 and 7. The mice were then challenged on day 14 using the same method. Control mice received saline alone59. Seventy-two hours after the final challenge, the mice were euthanized under anesthesia followed by cervical dislocation for further analysis. Both male and female mice were included in our study, and no sex-specific differences were observed in the results.

SID26681509 was administered via intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 10 mg/kg on days 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15. Nor-NOHA was delivered intratracheally at a dose of 4 mg/kg on days 14, 15, and 16. For control mice, the corresponding treatments were replaced with vehicle or saline.

Inflammatory cells in BAL fluid from the left lung were collected for inflammation evaluation. Cells were counted using a light microscope and identified by Wright-Giemsa staining according to the manufacturer’s instructions. H&E stained and PAS stained sections were assigned a score on an arbitrary scale of 0–4, as previously described, to evaluate the inflammatory situation59.

AHR was determined with airway resistance presented as the change from baseline measured following challenge with methacholine chloride60.

Isolation of human blood eosinophils

Peripheral blood granulocytes were isolated from participants’ blood samples using a Percoll density gradient centrifugation. The gradient consisted of three layers: 80%, 70%, and 60% (v/v) Percoll/synthetic medium mixtures, prepared in volumes of 4 ml, 3 ml, and 2 ml, respectively. Blood samples mixed with PBS (1:1 v/v, total volume of 4 ml) were placed onto the upper layer of the 60% Percoll. The tubes were centrifuged at 800 × g (acceleration 1, deceleration 0) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Granulocytes were collected from the 70%/80% interface. Eosinophils were then isolated by removing neutrophils through negative selection using biotin-conjugated antibodies against human CD11b, biotin-conjugated magnetic beads, and a magnetized MACS Column. The purity of the eosinophils was assessed by visual examination with Wright-Giemsa staining and gated as an SSC hi, Siglec-8+ cell population by flow cytometry analysis. Then eosinophils were cultured for further use in medium containing rhIL5 (50 ng/ml), an eosinophil survival factor.

Isolation of mouse blood eosinophils

Eosinophils were obtained and purified from the peripheral blood of Il5 Tg or Il5 Tg/eoCre/Ctsl flox/flox mice. Leucocytes were isolated by Percoll density gradient separation laid on a four-layer gradient of 80%, 60%, 55% and 50% Percoll. Cells containing eosinophils from the 60%/80% interface were harvested and washed twice in PBS. Eosinophils were subsequently isolated by removing the contaminating lymphocytes by negative selection with biotin-conjugated antibodies for CD45R (B220), CD4, CD8a, and Ter-119, biotin-conjugated magnetic beads and a magnetized MACS Column. The purity of the eosinophils was determined by visual examination of Wright-Giemsa staining and gated as an SSC hi, Siglec-F+ cell population by flow cytometry analysis. Then, eosinophils were cultured for further use in medium containing rmGM-CSF (10 ng/ml), an eosinophil survival factor.

Naïve eosinophils were obtained from the bone marrow of C57BL/6 mice. Bone marrow cells were collected by flushing the opened bones with PBS, using a 26-gauge needle. Erythrocytes were lysed for 3 min in 1 ml of lysis solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3 and 0.1 mM EDTA) followed by adding PBS. After centrifugation, the cells were washed once in the isolation medium and filtered through a sterile 40-μm nylon cell strainer. Cells were subsequently enriched with APC-conjugated antibodies for F4/80, APC-conjugated magnetic beads and a magnetized MACS Column. Then eosinophils were gated as an SSC hi, F4/80+, Siglec-F+ cell population and purified using a flow cytometer (Beckman moflo Astrios EQ).

Mouse bone marrow-derived eosinophils differentiation

Eosinophils were differentiated from the bone marrow of sex-matched 8 to 10-week-old mice. Bone marrow cells from control and eoCre/Ctsl flox/flox mice were collected as described above and cultured at a density of 106 cells/ml in base medium consisting of Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM), 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 × MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate, supplemented with 100 ng/ml rmSCF and 100 ng/ml rmFLT3-L from day 0 to day 4. On day 4, the medium was replaced with fresh base medium supplemented with 10 ng/ml rmIL5. On day 8, the cells were moved to new flasks to remove adherent contaminating cells. On day 12, the eosinophils were gated as an SSC hi, CD45+, F4/80+, Siglec-F+, CCR3+ cell population by flow cytometry analysis. Then mature eosinophils were cultured in medium with rmIL5 (2 ng/ml), an eosinophil survival factor.

Cell culture and treatment

Eosinophils were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin. HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) High-Glucose media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin. Where indicated, eosinophils were treated with rmIL33 (20 ng/ml), or rhIL33 (100 ng/ml), KM91104 (0.5 µM), Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1, 10 nM), concanamycin A (Con. A, 100 nM), E64D (50 µM), SID26681509 (50 µM), nor-NOHA (20 µM), and BEC (20 µM).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Eosinophils and lung homogenates were lysed using RNAiso Plus to extract total RNA. Reverse transcription was conducted using reagents from Takara Biotechnology. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was then performed to measure gene expression levels using the StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and TB Green Premix Ex Taq. All procedures were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer sequences were shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Immunoblotting

Protein was extracted from cells using RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Samples were subjected to electrophoresis on 6–15% polyacrylamide gels, followed by immunoblotting with relevant antibodies using standard methods. Signals were detected by chemiluminescence using the ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System or Odyssey DLx. Uncropped and unprocessed scans of the most relevant blots are provided in the Source Data file.

Flow cytometry

Lung tissues from mice were prepared into single-cell suspensions. Surface marker antibodies were added appropriately according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the samples were incubated for 30 min on ice, protected from light. Flow cytometry data were acquired using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Becton Dickinson). Mouse eosinophils were gated as an SSC hi, CD45+, F4/80+, Siglec-F+, CD11c− cell population after excluding debris, doublets, and autofluorescent cells.

For surface marker, cells were incubated with anti-CD63, anti-CD69 and anti-ICAM-1 for 30 min in ice. For intracellular LAMP1, LAMP2, and ARG1 detection, the surface staining was followed by cell fixation and permeabilization of the cell membrane using eBioscience Intracellular Fixation & Permeabilization Buffer Set. Cells were incubated with anti-LAMP1, anti-LAMP2, and anti-ARG1 for 30 min in ice, washed with PBS and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA).

ELISA

Cell samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C. The concentrations of IL4 and IL13 in cell culture supernatants were measured using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung sections were prepared and immunostained for EPX antibody (Mayo Clinic), CTSL antibody, and ARG1 antibody following standard methods. Images were captured using an Olympus IX83-FV3000 confocal inverted microscope. Eosinophils were fixed and stained with LAMP1 antibody, LAMP2 antibody, CTSL antibody, ARG1 and Histone H3 antibody at 4 °C overnight.

Degranulation

Eosinophil degranulation analysis was performed by measuring CD63 surface expression61. Cells were resuspended in 200 μl of medium at a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml and primed with 25 ng/ml rmGM-CSF for 20 min. In the final 5 min of GM-CSF priming, cytochalasin B (5 μM) was added to the cell suspension. Cells were then activated with rmC5a (10−7 M, 10−8 M, 10−9 M) for 15 min. Subsequently, CD63 surface expression was measured to assess eosinophil degranulation.

EGFR degradation

EGFR degradation was assessed by Western Blotting62. Briefly, eosinophils were treated with IL33 for 8 h and then cultured in serum-free 1640 for 2 h. After incubation with 100 ng/ml EGF in serum-free 1640 for 20 min on ice, the cells were cultured in EGF-free medium for 1 h. Finally, cells were harvested for analysis of EGFR expression by Western Blotting.

RNA-Seq analysis

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and checked using RNase-free agarose gel electrophoresis. The resulting cDNA library was sequenced using Illumina Novaseq6000 by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China).

Plasmid constructs and transfection

The coding sequences (CDS) of CTSL and ARG1 were obtained from Miaoling Corporation, China. The full-length gene sequence of wild-type human CTSL was synthesized and subcloned into a pCMV vector, with an HA tag (YPYDVPDYA) introduced at the C-terminal domain of CTSL. The human ARG1 was synthesized and subcloned into a pLV3 vector, incorporating an N-terminal 3 × Flag tag (DYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYKDDDDK) to generate an ARG1 fusion protein for enhanced protein expression.

Recombinant plasmids of CTSL and ARG1 were transfected into HEK293T cells using polyethylenimine (PEI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Eosinophils were transduced with lentiviral supernatants from the HEK293T cell line by centrifugal infection. Overexpression efficiencies were assessed by measuring protein levels by immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were collected and suspended in 500 μl lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. The suspension was incubated with gentle agitation on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. An aliquot of the supernatant (40 μl) was mixed with lysis buffer and loading buffer as the input sample. The remaining supernatant was immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag beads, or anti-HA beads. After overnight incubation, the beads were washed four times with PBST buffer (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20), then boiled with 70 μl loading buffer at 100 °C for 10 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

The PLA was conducted using the Duolink In Situ Red Starter Kit Mouse/Rabbit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Eosinophils were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. After blocking, the samples were incubated overnight with antibodies against CTSL and ARG1. The following day, the samples were incubated with MINUS and PLUS PLA probes corresponding to the primary antibodies, followed by ligation with circle-forming DNA oligonucleotides and rolling-circle amplification to generate the PLA signal. Finally, samples were mounted with DAPI-containing Fluoromount-G™ (SouthernBiotech). The slides were imaged using a confocal microscope (Olympus IX83-FV3000).

Liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

For eosinophil samples, five biological replicates were included in each group. Cells were thawed at 4 °C and mixed with 50 µl of isotope internal standards and 1 ml of cold methanol/acetonitrile/aqueous solution (2:2:1, v/v). The mixture was then homogenized by low-temperature sonication (30 min per cycle, repeated twice). Plasma samples were obtained from 9 healthy controls and 18 asthmatic patients. A 100 μl aliquot of thawed plasma was mixed with 50 μl of isotope internal standards and 400 μl of cold methanol/acetonitrile solution (1:1, v/v), followed by thorough vortex.

The mixture was then incubated at −20 °C for 1 h and centrifuged for 20 min (14,000 × g, 4 °C). The supernatant was dried in a vacuum centrifuge. Samples were re-dissolved in 100 μl acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v), thoroughly vortexed, and then centrifuged (14,000 × g, 4°C, 15 min). The supernatants were collected for LC-MS/MS analysis to assess the levels of amino acids such as arginine, ornithine, and others. LC-MS/MS was performed on an Agilent 1290 Infinity UHPLC coupled to a QTRAP 6500+ mass spectrometer (AB Sciex). Separation was achieved with a water/acetonitrile gradient containing 25 mM ammonium formate and 0.01% formic acid. MS was operated in positive ESI mode under multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). Raw data were converted to mzXML using ProteoWizard MSConvert and processed with XCMs for peak detection and alignment. Chromatographic peaks were quantified using MultiQuant, and metabolites were identified by comparison with authentic standards. The analysis was carried out at Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Co., Ltd.

Lysosomal pH assay

LysoSensor Green DND-189 was used to trace and detect lysosomal pH. Cells were stained with 2 μM LysoSensor Green DND-189 in medium (supplemented with FBS and penicillin-streptomycin) at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were analyzed using flow cytometry or immunofluorescence staining.

Analysis of CTSL activity

The CTSL activities of eosinophils were measured using a commercially available kit according to the manufacturer. For cultured eosinophils, cells were stained with Magic Red at a dilution of 1:1000 at 37 °C for 30 min, protected from light. For lung tissue samples, single-cell suspensions were prepared by removing red blood cells, followed by staining with Magic Red as described above. After washing with PBS, surface marker antibodies were added appropriately and the samples were incubated for 30 min on ice, protected from light. Flow cytometry was then performed for analysis.

Analysis of arginase activity

Arginase activity in eosinophils was measured using the Arginase Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit, following protocol’s instructions. Eosinophils were collected in saline, homogenized, and subsequently centrifuged. The supernatant was then assayed using reagents provided in the kit.

Analysis of polyamine

Polyamine levels of eosinophils were measured using a commercially available Total Polyamine Assay Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Eosinophils were collected in assay buffer provided with the kit. The cells were homogenized and centrifuged to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was then analyzed using reagents included in the kit.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess the relationships between variables. Differences between the two groups were assessed using the two-sided unpaired Student’s t test, while differences among multiple groups were evaluated using one-way or two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available within the article and its supplementary information. Key resources are shown in Supplementary Data 1. The RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession code GSE280872. The metabolomics data generated in this study have been deposited in the MetaboLights database under accession code MTBLS13001. All other data are available in the article and its Supplementary files or from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Reddel, H. K. et al. Global initiative for asthma strategy 2021: executive summary and rationale for key changes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 205, 17–35 (2022).

Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Rosenberg, H. F., Phipps, S. & Foster, P. S. Eosinophil trafficking in allergy and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119, 1303–1310 (2007).

Hammad, H. & Lambrecht, B. N. The basic immunology of asthma. Cell 184, 1469–1485 (2021).

Ballabio, A. & Bonifacino, J. S. Lysosomes as dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 101–118 (2020).

Gros, F. & Muller, S. The role of lysosomes in metabolic and autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19, 366–383 (2023).

Mindell, J. A. Lysosomal acidification mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 74, 69–86 (2012).

Persson, T. et al. Specific granules of human eosinophils have lysosomal characteristics: presence of lysosome-associated membrane proteins and acidification upon cellular activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291, 844–854 (2002).

Archer, G. T. & Hirsch, J. G. Isolation of granules from eosinophil leucocytes and study of their enzyme content. J. Exp. Med. 118, 277–286 (1963).

Kurashima, K. et al. The role of vacuolar H(+)-ATPase in the control of intragranular pH and exocytosis in eosinophils. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 75, 689–698 (1996).

Zhang, Z. et al. Role of lysosomes in physiological activities, diseases, and therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14, 79 (2021).

Lee, J. U. et al. Overexpression of V-ATPase B2 attenuates lung injury/fibrosis by stabilizing lysosomal membrane permeabilization and increasing collagen degradation. Exp. Mol. Med. 54, 662–672 (2022).

Weidner, J. et al. Expression, activity and localization of lysosomal sulfatases in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Sci. Rep. 9, 1991 (2019).

Reiser, J., Adair, B. & Reinheckel, T. Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 120, 3421–3431 (2010).

Sudhan, D. R. & Siemann, D. W. Cathepsin L targeting in cancer treatment. Pharm. Ther. 155, 105–116 (2015).

Xu, X. et al. Eosinophils promote pulmonary matrix destruction and emphysema via Cathepsin L. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 390 (2023).

Mouawad, J. E. et al. Reduced Cathepsin L expression and secretion into the extracellular milieu contribute to lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 62, 1306–1316 (2023).

Muus, C. et al. Single-cell meta-analysis of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes across tissues and demographics. Nat. Med. 27, 546–559 (2021).

Yue, M., Tao, S., Gaietto, K. & Chen, W. Omics approaches in asthma research: challenges and opportunities. Chin. Med. J. Pulm. Crit. Care Med. 2, 1–9 (2024).

Badi, Y. E. et al. IL1RAP expression and the enrichment of IL-33 activation signatures in severe neutrophilic asthma. Allergy 78, 156–167 (2023).

Ketelaar, M. E. et al. Phenotypic and functional translation of IL33 genetics in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 147, 144–157 (2021).

Dolitzky, A. et al. Mouse resident lung eosinophils are dependent on IL-5. Allergy 77, 2822–2825 (2022).

Pritam, P. et al. Eosinophil: a central player in modulating pathological complexity in asthma. Allergol. Immunopathol. 49, 191–207 (2021).

Salam, M. T., Islam, T., Gauderman, W. J. & Gilliland, F. D. Roles of arginase variants, atopy, and ozone in childhood asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123, 596–602 (2009).

Duan, Q. L. et al. Regulatory haplotypes in ARG1 are associated with altered bronchodilator response. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 183, 449–454 (2011).

Delgado-Dolset, M. I. et al. Understanding uncontrolled severe allergic asthma by integration of omic and clinical data. Allergy 77, 1772–1785 (2022).

Munder, M. et al. Arginase I is constitutively expressed in human granulocytes and participates in fungicidal activity. Blood 105, 2549–2556 (2005).

Ratto, E. et al. Direct control of lysosomal catabolic activity by mTORC1 through regulation of V-ATPase assembly. Nat. Commun. 13, 4848 (2022).

Trombetta, E. S., Ebersold, M., Garrett, W., Pypaert, M. & Mellman, I. Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science 299, 1400–1403 (2003).

Zhu, L. et al. SLC38A5 aggravates DC-mediated psoriasiform skin inflammation via potentiating lysosomal acidification. Cell Rep. 42, 112910 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. TFEB-vacuolar ATPase signaling regulates lysosomal function and microglial activation in tauopathy. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 48–62 (2024).

Olson, O. C. & Joyce, J. A. Cysteine cathepsin proteases: regulators of cancer progression and therapeutic response. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 712–729 (2015).

Cao, M., Luo, X., Wu, K. & He, X. Targeting lysosomes in human disease: from basic research to clinical applications. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 379 (2021).

Bonam, S. R., Wang, F. & Muller, S. Lysosomes as a therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 923–948 (2019).

Sendler, M. et al. Cathepsin B-mediated activation of trypsinogen in endocytosing macrophages increases severity of pancreatitis in mice. Gastroenterology 154, 704–718 e710 (2018).

McKelvey, M. C. et al. Cathepsin S contributes to lung inflammation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 205, 769–782 (2022).

Tsai, Y. H., Parker, J. S., Yang, I. V. & Kelada, S. N. P. Meta-analysis of airway epithelium gene expression in asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 51, 1701962 (2018).

Vernet, R. et al. Identification of novel genes influencing eosinophil-specific protein levels in asthma families. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 150, 1168–1177 (2022).

Liu, C. L. et al. Cysteine protease cathepsins in cardiovascular disease: from basic research to clinical trials. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 351–370 (2018).

de Mingo, Á et al. Cysteine cathepsins control hepatic NF-κB-dependent inflammation via sirtuin-1 regulation. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2464 (2016).

Wu, H. et al. Cathepsin S activity controls injury-related vascular repair in mice via the TLR2-mediated p38MAPK and PI3K-Akt/p-HDAC6 signaling pathway. Arterioscler. Thrombosis Vasc. Biol. 36, 1549–1557 (2016).

Canè, S. et al. Neutralization of NET-associated human ARG1 enhances cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabq6221 (2023).

Lv, Y. et al. Ginseng-derived nanoparticles reprogram macrophages to regulate arginase-1 release for ameliorating T cell exhaustion in tumor microenvironment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 42, 322 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Annexin A2/TLR2/MYD88 pathway induces arginase 1 expression in tumor-associated neutrophils. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e153643 (2022).

West, E. E. et al. Loss of CD4(+) T cell-intrinsic arginase 1 accelerates Th1 response kinetics and reduces lung pathology during influenza infection. Immunity 56, 2036–2053.e2012 (2023).

Gordon, S. & Taylor, P. R. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 953–964 (2005).

Giese, M. A., Hind, L. E. & Huttenlocher, A. Neutrophil plasticity in the tumor microenvironment. Blood 133, 2159–2167 (2019).

Zimmermann, N. & Rothenberg, M. E. The arginine-arginase balance in asthma and lung inflammation. Eur. J. Pharm. 533, 253–262 (2006).

Morris, C. R. et al. Decreased arginine bioavailability and increased serum arginase activity in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 170, 148–153 (2004).

Xu, W. et al. Increased mitochondrial arginine metabolism supports bioenergetics in asthma. J. Clin. Investig. 126, 2465–2481 (2016).

Rutschman, R. et al. Cutting edge: Stat6-dependent substrate depletion regulates nitric oxide production. J. Immunol. 166, 2173–2177 (2001).

El Kasmi, K. C. et al. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1399–1406 (2008).

Qualls, J. E. et al. Arginine usage in mycobacteria-infected macrophages depends on autocrine-paracrine cytokine signaling. Sci. Signal. 3, ra62 (2010).

Yurdagul, A. Jr. et al. Macrophage metabolism of apoptotic cell-derived arginine promotes continual efferocytosis and resolution of injury. Cell Metab. 31, 518–533.e510 (2020).

Geiger, R. et al. L-arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell 167, 829–842.e813 (2016).

Caldwell, R. W., Rodriguez, P. C., Toque, H. A., Narayanan, S. P. & Caldwell, R. B. Arginase: a multifaceted enzyme important in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 98, 641–665 (2018).

Wei, Z., Oh, J., Flavell, R. A. & Crawford, J. M. LACC1 bridges NOS2 and polyamine metabolism in inflammatory macrophages. Nature 609, 348–353 (2022).

Lercher, A. et al. Type I interferon signaling disrupts the hepatic urea cycle and alters systemic metabolism to suppress T cell function. Immunity 51, 1074–1087.e1079 (2019).

Han, Y. et al. Airway epithelial cGAS is critical for induction of experimental allergic airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 204, 1437–1447 (2020).

Li, W. et al. MTOR suppresses autophagy-mediated production of IL25 in allergic airway inflammation. Thorax 75, 1047–1057 (2020).

Germic, N. et al. ATG5 promotes eosinopoiesis but inhibits eosinophil effector functions. Blood 137, 2958–2969 (2021).

Liu, B. et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein inhibits autophagic degradation by impairing lysosomal maturation. Autophagy 10, 416–430 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the participating laboratories for their invaluable contributions to this work. We extend our gratitude to the physicians, nurses, and research assistants who helped provide and collect samples and recruit participants. We are incredibly grateful to our patients and their families for their consent to participate in this study. We thank the late J. J. Lee (Mayo Clinic) for Epx-Cre and Il-5 Tg mice and antibodies to EPX. We also thank Zhaoxiaonan Lin from the Core Facilities, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, for the technical support. This work is dedicated to the memory of our dear friend and supervisor, Huahao Shen, whose larger-than-life character was matched only by his scientific genius. We miss him dearly. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20265 (W.L.), 82370027 (Z.C.), 81930003 (H.S.), 82270023 (W.L.), 82200026 (Y.W. (Yinfang Wu)), the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2023C03067 (W.L.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L., Z.C., and Y.W. (Yinfang Wu) conceived the project and supervised the research. W.L., Z.C., and Y.H. designed the experiments. Y.H., N.L., and Y.Z. performed all functional assays, including the animal and cell experiments. Z.J., B.L., D.S., X.C., Q.W., M.Z., K.C., L.D., Z.L., J.L., S.G., W.H., and Y.W. (Yuejue Wang) participated in cell culture experiments and contributed to data acquisition and processing. All authors contributed to the data analysis. W.L., Z.C., F.Y., and S.Y. revised the manuscript written by Y.H. and Y.W. (Yinfang Wu). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Sergejs Berdnikovs, Pauline ESTEVES, Fiorentina Roviezzo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Y., Li, N., Zhao, Y. et al. Lysosomal acidity and cathepsin L activate eosinophils via ARG1-mediated arginine metabolism in allergic airway inflammation. Nat Commun 16, 10451 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65400-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65400-z