Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) wave propagation plays a crucial role in intercellular communication. Elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ (Ca2+ transient) in a single cell is attributed to various Ca2+ channels present in the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum, whereas gap junctions contribute to propagation of Ca2+ waves between cells. However, we found that Ca2+ waves propagate without gap junctions during apoptotic cell extrusion (ACE). Mechanistically, we identified that a chain reaction of mechano-signal transduction from proximal to distal cells through the mechanosensitive Ca2+ channels (MCCs) mediates the Ca2+ wave propagation; an apoptotic cell shrinks accompanied by a Ca2+ transient, followed by pulling the edges of neighboring cells, which opens MCCs in neighboring cells, resulting in Ca2+ transients in these cells. Furthermore, Ca2+ wave propagation promotes Rac-Arp2/3 pathway-mediated polarized collective migration, generating approximately 1 kPa of force toward extruding cells. Our results uncovered a mechanochemical mechanism of Ca2+ wave propagation and its significant role in ACE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) wave propagation is observed during various phenomena including fertilization, embryogenesis, and wound healing, and is involved in cell–cell communications1,2. Several Ca2+ channels, including voltage-gated, transmitter-gated, and mechanosensitive Ca2+ channels (MCCs), on the plasma membrane promote Ca2+ entry from the extracellular environment3,4. Specifically, Transient receptor potential (TRP) and Piezo1 channels, which are involved in mechanosensory processes, evoke Ca2+ entry in response to membrane stretch5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) and ryanodine receptors control Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)3,4. Orai1, Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), and Transient receptor potential canonical 1 (TRPC1) mediate store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), which promotes Ca2+ influx from outside the cell in response to a reduction of Ca2+ within the ER11,12,13,14,15. Thus, these factors contribute to the elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ (Ca2+ transient) in a single cell. On the other hand, intercellular propagation of Ca2+ waves requires gap junctions16. Small compounds such as inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) pass through gap junctions, enabling wave propagation among cells3,5. In addition, extracellular messengers such as ATP, nitric oxide, and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), which are secreted through hemichannels composed of gap junction components, also contribute to wave propagation5,17,18,19.

In mucosal epithelial tissues such as the oropharynx, airways, intestines, and genitalia, the apical membrane of constituent cells comes into contact with aqueous environments containing bacteria, viruses, and chemical compounds. These tissues have a strong barrier function to maintain epithelial tissue integrity via well-developed cell adhesions. However, damaged and potentially dangerous cells appear even in these tissues; therefore, organisms require a system that extrudes these cells without disrupting their barrier function20,21,22. One such system is apoptotic cell extrusion (ACE), via which apoptotic cells are extruded toward the apical side6,23. Accumulating evidence showed that Piezo1 is required for ACE in the overcrowding epithelial tissues, acting as a mechanosensor and regulator of epithelial homeostasis by balancing cell extrusion with proliferation10,24,25,26. Recently, we found that Ca2+ waves are propagated from an apoptotic cell to surrounding cells during ACE, and the propagation is mediated by TRPC1, IP3R, and gap junction11,27. However, the molecular mechanism and biological significance of intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation through MCCs during ACE remain largely unknown.

In this study, we developed a system for observing ACE in a mucosal epithelial tissue, the enveloping layer of zebrafish embryos, and revealed how intercellular Ca²⁺ waves are propagated through MCCs and IP3Rs during ACE.

Results

Establishment of an in vivo imaging system for ACE

Using an in vitro cell culture system (the human breast cancer cell line MCF7), previous research reported that epithelial apoptosis is induced by femtosecond laser irradiation and apoptotic cells are apically extruded7. To investigate the mechanism underlying ACE with an in vivo system, we used a mucosal epithelial tissue in zebrafish embryos as a model for ACE by applying a method similar to that recently reported by Duszyc et al.7. When the nucleus of an epithelial cell was irradiated with a femtosecond laser, the irradiated cell became positive for annexin V-FITC (a sensitive probe for identifying apoptotic cells) and was extruded from the epithelial sheet within 15 min (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The apoptosis induction by laser irradiation was also verified by the immunostaining with anti-cleaved caspase 3 antibody (an apoptosis marker) and Propidium Iodide (PI) staining (a necrosis marker) (Supplementary Fig. 1b–e). These findings indicate that an in vivo imaging system for ACE was established.

Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE in vivo

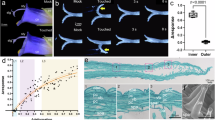

Recently, we demonstrated that Ca2+ waves propagate and facilitate extrusion of oncogenic cells, which is termed epithelial defense against cancer (EDAC), and ACE in vitro (Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells)27. We thus assumed that Ca2+ waves contribute to ACE in vivo. To explore this possibility, we investigated Ca2+ dynamics during ACE in zebrafish embryos expressing GCaMP7 (a Ca2+ sensor) and Lifeact-GFP8,9,28. Immediately after apoptosis induction, Ca2+ levels increased in apoptotic cells, and then a Ca2+ wave propagated from apoptotic cells to surrounding non-irradiated cells (Fig. 1a–d). The Ca2+ wave could propagate across approximately 2 – 5 cells (Fig. 1a, b). Quantitative analyses revealed that cytoplasmic Ca2+ elevated immediately after apoptosis induction within the apoptotic cells and sequentially from Row 1 to Row 5 of the surrounding cells with approximately 5 – 30 s time lags (Fig. 1c). Although Ca2+ elevations were maintained in apoptotic cells until the ACE completion, Ca2+ levels in the surrounding cells were returned to the basal levels faster than that of apoptotic cells (Fig. 1d). Following Ca2+ wave propagation, an actomyosin ring formed among the nearest surrounding non-irradiated cells, indicating that the Ca2+ wave propagated before this ring contracted (Fig. 1a), which is consistent with EDAC27.

a LUT color-coded images of GCaMP7 and Lifeact-GFP dynamics during cell extrusion induced by a 150 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser, applied through a 40×/0.8 NA objective lens (representative of 7 independent samples). Red asterisks indicate the laser focal point. Scale bar: 50 µm. b The fluorescence intensity of GCaMP7 was quantified in the extruding cell and multiple rows of surrounding cells. The Ca2+ levels in the extruding cell and first, second, third, fourth, and fifth rows of surrounding cells are indicated by the red, white, green, yellow, magenta, and gray lines, respectively, as shown in (a). The fluorescence signal at each instant is represented as ΔF, while F0 refers to the fluorescence intensity in the initial frame. ΔF/F0 was subsequently calculated. c Time lag from apoptosis induction to Ca2+ elevation in the apoptotic cells and multiple rows of surrounding cells. Apoptotic cell; n = 7 cells, Row 1; n = 31 cells, Row 2; n = 31 cells, Row 3; n = 30 cells, Row 4; n = 30 cells, Row 5; n = 29 cells from 7 embryos. d Duration of Ca2+ elevation in the apoptotic cells and multiple rows of surrounding cells. Apoptotic cell; n = 6 cells, Row 1; n = 18 cells, Row 2; n = 17 cells, Row 3; n = 17 cells, Row 4; n = 15 cells, Row 5; n = 11 cells from 6 embryos. c, d Data are presented as Mean class="thinsp" contenteditable="false"> ± standard deviation (SD). Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test followed by post hoc Steel-Dwass test, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and not significant (ns).

Intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE involves MCCs (Trpc1 and Piezo1) and IP3Rs

By performing pharmacological analyses and gene knockdown in in vitro cell cultures, we showed that IP3Rs, SOCE, gap junctions, and MCCs are involved in Ca2+ wave propagation during EDAC27. In addition, TRPM7, S1P, and ATP reportedly regulate Ca2+ wave propagation19,29,30,31,32. However, the molecular mechanism underlying Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE remains unknown. Therefore, we performed pharmacological analyses to identify the key regulators. Treatment with gadolinium (Gd3+; MCC inhibitor), GsMTx4 (MCC inhibitor), xestospondin C (XestoC; IP3R inhibitor), 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB; MCC, IP3R, and SOCE inhibitor), or BTP-2 (SOCE inhibitor) diminished Ca2+ wave propagation, but treatment with NS8593 (TRPM7 inhibitor), 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (αGA; gap junction inhibitor), Carbenoxolone (CBX; pannexin and connexin hemichannel inhibitor), JTE013 (S1P2 inhibitor), SKI-II (sphingosine kinase inhibitor), apyrase (ATPase), suramin (ATP-agonist), or αGA plus apyrase did not (Fig. 2a, b). Consistently, treatment with Yoda1 (Piezo1 activator) expanded the Ca2+ wave propagation (Fig. 2a, b). These results suggest that MCCs, IP3Rs, and SOCE, but not TRPM7, gap junctions, ATP, and S1P, regulate Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE.

a LUT color-coded images of GCaMP7 and Lifeact-GFP in embryos treated with DMSO (control), Gd3+, GsMTx4, NS8593, Yoda1, XestoC, 2-APB, BTP-2, αGA, CBX, JTE013, SKI-II, Apyrase, Suramin, and αGA + Apyrase; and WT (trpc1+/+), heterozygous (trpc1+/-), and homozygous (trpc1-/-) embryos injected with or without piezo1-MO, and iptr1a + iptr1b at 0 s (left panels) or 30 s (right panels) after irradiation with a 150 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser through a 40×/0.8 NA objective lens. White dotted lines and red asterisks indicate the Ca2+ wave propagation area and laser focal point, respectively. The effectiveness of apyrase or suramin treatment on Ca2+ wave propagation in zebrafish embryonic epithelia was shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Scale bar: 50 µm. b The propagation area of the Ca2+ wave. n = 16, 9, 13, 8, 8, 11, 10, 10, 13, 12, 8, 11, 9, 11, and 8 embryos. c Effects of trpc1 knockout and/or piezo1 knockdown on the expansion area of the Ca2+ wave. n = 12, 19, 6, 9, 17, and 6 embryos. d Effects of itpr1a + itpr1b knockdown on the expansion area of the Ca2+ wave. Control-MO: n = 5 and itpr1a-MO plus itpr1b-MO: n = 12 embryos. b – d Data are presented as Mean class="thinsp" contenteditable="false"> ± SD. b, c Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test followed by post hoc Steel-Dwass test, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and ns. d Unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test, ** p < 0.01.

Notably, Gd3+, GsMTx4, and 2-APB target various types of MCCs, but their common targets are TRPCs and Piezo7,33,34,35. Importantly, by performing gene knockdown experiments, we reported that TRPC1 and Piezo1, but not TRPC6, regulate Ca2+ wave propagation during EDAC27. Thus, we generated trpc1-knockout zebrafish using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and performed knockdown of piezo1 by morpholino (piezo1-MO) because piezo1-morpholino (piezo1-MO) phenocopies knockout of piezo1 in zebrafish10. Consistent with the results regarding EDAC in mammalian cell cultures, Ca2+ waves were impaired in heterozygous and homozygous trpc1 mutants (Fig. 2a, c), indicating that trpc1 plays a crucial role in regulating Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE and EDAC. In addition, piezo1-MO diminished Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE and the phenotypes observed in piezo1-morphants became severer in the heterozygous and homozygous trpc1 mutants (Fig. 2a, c), suggesting that Trpc1 and Piezo1 both contribute to the Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE. We also performed genetic manipulations for IPTRs and showed that double knockdown of iptr1a and iptr1b results in the inhibition of Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE in embryos co-injected with iptr1a-MO and iptr1b-MO (Fig. 2a, d). These results indicate that MCCs (Trpc1 and Piezo1) and IP3Rs (Itpr1a and Itpr1b), are involved in intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE.

Importance of Ca2+ wave propagation for ACE

We next tested the biological significance of Ca2+ waves for ACE. In controls, a laser-irradiated cell was stained with annexin V-FITC within 5 min and extruded from the epithelial sheet by 15 min, indicating that ACE was completed within 15 min in this experimental setting (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Movie 1). However, when MCCs were inhibited by GsMTx4 treatment or trpc1 knockout with piezo1-MO, laser-irradiated cells were stained with annexin V-FITC within 5 min but not extruded by 15 min; instead, they remained within the sheets even at 30 min after apoptosis induction (Fig. 3b–d and Supplementary Movies 2, 3). These results suggest that Ca2+ waves generated by MCCs are required for ACE progression.

a–c Representative images of ACE in (a) DMSO-treated embryos (Control), (b) GsMTx4-treated embryos, and (c) trpc1-/- embryos injected with piezo1-MO upon irradiation with a 15 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens. Apoptotic cells were identified by annexin V-FITC labeling. Red asterisks indicate the laser focal point. Dotted lines in x-z indicate the apical surface of epithelial cells. Scale bar: 20 µm. d Quantification of apical extrusion. Control: n = 12, GsMTx4: n = 11, and trpc1-/- plus piezo1-MO: n = 9 embryos. two-sided Chi-squared, * p < 0.05, and ns.

Mechanotransduction signaling via MCCs initiates intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation

Previous studies reported that gap junctions and extracellular ATP mediate intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation5,16,27, whereas inhibition of gap junction (αGA and CBX) and ATP (apyrase and suramin) could not inhibit Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE in this study (Fig. 2a, b). It is still possible that these inhibitors did not work in zebrafish embryonic epithelia. To eliminate the possibility, we tested their inhibitory effects on Ca2+ transient/wave in our experimental settings. Ca2+ transients and wave propagations stochastically occur in normal zebrafish epithelia. Gap junction and ATP are involved in the Ca2+ wave propagations and transients. Importantly, we found that αGA or CBX could inhibit Ca2+ wave propagations, and that apyrase or suramin could inhibit Ca2+ transients (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that these inhibitors are effective in our experimental settings. These results suggest the existence of a mechanism of gap junction-independent Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE. We therefore aimed to explore its detailed mechanism and its role in ACE.

MCCs and IP3Rs are major regulators of calcium-induced calcium release (CICR): MCCs promote Ca2+ influx in response to cell stretching and induce Ca2+ release from the ER through IP3Rs, resulting in a large elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration: [Ca2+]i (Ca2+ transient)15,36,37,38. Based on these findings, we speculated that a mechanical stimulus (i.e., cell stretching) activates MCCs, and then CICR via IP3Rs occurs during intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation. To test this hypothesis, we investigated several parameters including the correlation of deformation with Ca2+ elevation, deformation rate, and timing of cell deformation (Fig. 4). Spatiotemporal analysis revealed that deformation occurred all surrounding cells inside the Ca2+ wave (Rows 1–5) towards the apoptotic cell and the deformation rates gradually decreased from Row 1 to Row 5 (Fig. 4a, d). The cross-correlation analyses of cell deformation with the Ca2+ transient showed that the maximum positive correlation coefficients were observed with 3 s time lag following cell stretching in Row 1, meaning that cell stretching precedes Ca2+ elevation in the cells (Fig. 4b, c). Cell deformations at Row 1 occurred within 5 s after apoptotic induction, and cell stretches at Row 2 – 5 occurred with gradual delay (Fig. 4e), which is consistent with the delay of Ca2+ elevation (Fig. 1c).

a Schematic illustration of the deformation of surrounding cells inside (Rows 1–5) and outside the Ca2+ wave. Lt_0 and Lt_60 represent the length of surrounding cells at 0 s and 60 s after induction of apoptosis (before and after wave propagation, respectively). The graph (right panel) shows the deformation rates of the cells inside the waves. Row 1: n = 29 cells, Row 2: n = 35 cells, Row 3: n = 31 cells, Row 4: n = 26 cells, and Row 5: n = 20 cells from 7 embryos. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01, and ns. b Detailed observation of cell deformation and Ca²⁺ transient using GCaMP7-CAAX upon irradiation with a 15 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens. The horizontal axis represents time (total 50 s), and the vertical axis indicates positional information (apoptotic cell and a neighboring cell in Row 1). White dotted line indicates the cell–cell junction. Red arrowhead marks the onset of cell deformation (stretch). Cyan lines represent the Ca²⁺ transients in the apoptotic and Row1 cells. Still images for this kymograph were included in Supplementary Fig. 3a. c Temporal cross-correlation between the timing of cell deformation and Ca²⁺ transients. Black lines and cyan shaded area indicate the average temporal cross-correlation coefficients and mean ± s.e.m. Row 1: n = 27 cells; Row 2: n = 25 cells, from 15 embryos. d Cell deformation inside and outside the Ca2+ waves. Control, Inside: n = 104 cells, Outside: n = 20 cells from = 7 embryos. GsMTx4, Inside: n = 76, Outside: n = 95 from 12 embryos. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentiles) with the line indicating the median, and the whiskers show the minimum and maximum values. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01, and ns. e Time lag of cell deformation from laser irradiation. Control (DMSO), Row 1: n = 26 cells, Row 2: n = 33 cells, Row 3: n = 20 cells, Row 4: n = 13 cells, and Row 5: n = 17 cells from 7 embryos. GsMTx4: Row 1: n = 40 cells, Row 2: n = 19 cells, from 12 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test followed by post hoc Steel-Dwass test, ** p < 0.01 and ns.

We also compared the stretching of surrounding cells inside and outside the Ca2+ wave. Measurement of deformation of surrounding cells showed that surrounding cells inside the Ca2+ wave stretched toward the apoptotic cell and stretched more than surrounding cells outside the Ca2+ wave (Fig. 4c). Comparable deformations of surrounding cells inside and outside the Ca2+ wave were observed upon GsMTx4 (MCC inhibitor) treatment (Fig. 4c), but wave propagation was significantly reduced by Rows 1 or 2 (Figs. 2b and 4d). Taken together, our results show that stretch-dependent activation of MCCs is required for wave propagation from the irradiated cell to adjacent cells, and suggest that mechanotransduction signaling via MCCs contributes to the initiation of intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation.

To further investigate whether intercellular Ca2+ waves are propagated by cell deformation, we disrupted the mechanical balance among cells by performing laser nano-dissection, which induces local cell deformation without serious damage (Supplementary Fig. 3)39,40. Upon laser dissection, Ca2+ transients occurred in the irradiated cell, which contracted immediately (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). Then, the interface between the irradiated cell and an adjacent cell shifted toward the irradiated cell, and the adjacent cell stretched, leading to the Ca2+ transient in the adjacent cell (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). These results suggest that the contraction of irradiated cells triggers a stretch-dependent Ca2+ transient in adjacent cells.

We next verified whether the stretch-dependent Ca2+ transient occurs during ACE, and whether this is mediated by MMCs, but not gap junctions. Consistent with the above results (Fig. 4b, and Supplementary Fig. 3), just after apoptosis induction, Ca2+ transient and cell contraction occurred in the apoptotic cell. Depending on the contraction, the stretch of the adjacent cell (Row1) occurred, leading to Ca2+transient in the adjacent cell (Fig. 5). When gap junction communications were inhibited with CBX, cell stretching and intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation in the adjacent cell occurred normally (Fig. 5). However, when MCCs were inhibited with GsMTx4-treatment or trpc1 knockout with piezo1-MO, the Ca2+ transient in the irradiated cell and stretching of the adjacent cell occurred normally, but intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation in the adjacent cell was completely blocked (Fig. 5), confirming that intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation is initiated by stretch-dependent activation of MCCs, not by gap junctions.

a Temporal dynamics of Ca²⁺ transients at representative junctions. To induce cell deformation without triggering apoptosis, a femtosecond laser at 10 nJ/pulse was focused on the site marked with a red asterisk through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens. Control (DNSO, top panel), GsMTx4 (upper panel), CBX (lower panel), and trpc1-/- plus piezo1-MO (bottom panel). The right panels show kymographs of the white-boxed regions on the left. Scale bar: 20 µm. b The normalized GCaMP7 intensity of the apoptotic cell and adjacent surrounding cells, and displacement of the contact edge. Control (DMSO, top graph), GsMTx4 (upper graph), CBX (lower graph), and trpc1-/- plus piezo1-MO (bottom graph). Arrows indicate time points of laser irradiation. The shaded region represents the standard error of the mean. Control: n = 14 embryos, CBX: n = 8 embryos, GsMTx4: n = 8 embryos, and trpc1-/- plus piezo1-MO: n = 10 embryos.

Cell stretching and Ca2+ transient at each row occurred sequentially, starting from the nearest adjacent cells (Row 1) to Row 5 in turn (Figs. 1c, 4a, 4d). Adjacent cells (Row1) contracted after stretch dependent-Ca2+ transient in the laser nano-dissection experiments (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Based on these results, it is unlikely that the initial contraction of the apoptotic cell induces cell stretches on several rows and directly activates MCCs in all these cells. Instead, we reasoned that a chain reaction of Ca2+ transients, depending on the sequential deformation of adjacent cells, is a core mechanism for intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE. To test the possibility, we observed and measured cell deformations especially in Row 1 and Row 2 using higher magnification images (Fig. 6). When the femtosecond laser was irradiated to a cell at 0 s (i.e., apoptosis induction), the cell at Row 1 stretch 2 – 10% by around 10 s depending on the initial contraction of the apoptotic cell (Fig. 6a, d, e) and then contracted 5 – 25% by around 60 s (Fig. 6a, d, f), those are consistent with the laser nano-dissection experiments (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Following the contraction of the cell at Row 1, the cell at Row 2 stretched and then contracted similarly (Fig. 6a, e, f). Taken together, our results suggest that intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE occurs through stepwise deformation of the cell as a trigger wave mechanism41,42: First, the apoptotic cell contracted and the adjacent cell (Row 1) stretched toward the apoptotic cell. Second, in the adjacent cell, Ca2+ transients were induced by MCCs and then contracted. Third, depending on the stretch/contraction of the cell, the cell in Row 2 is stretched. Fourth, in the cell at Row 2, Ca2+ transients were induced by MCCs and then contracted. Fifth, repeat this in the outer rows.

a–c Relative changes in cell length in Row 1 (red line) and Row 2 (blue line) in embryos treated with DMSO (Control, (a), GsMTx4 (b), and XestoC (c). d Schematic illustration of how to measure the Lt_0, Lt_Elo_max, and Lt_Con_min, and equations to calculate Lt_Elo_max / Lt_0 and Lt_Con_min / Lt_Elo_max. Lt_0, Lt_Elo_max, and Lt_Con_min of each condition are indicated in (a–c). e, f Effect of the cell elongation rate (e) and the cell contraction rate (f) in embryos treated with Control (black), GsMTx4 (red), and XestoC (blue). Control; n = 19 cells from 7 embryos, GsMTx4; n = 19 cells from 7 embryos, XestoC; n = 21 cells from 7 embryos. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentiles) with the line indicating the median, and the whiskers show the minimum and maximum values. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and ns.

MCCs and IP3Rs have distinct roles in intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE

MCCs, including Trpc1 and Piezo1, initiate Ca2+ influx in response to cell stretching and activate CICR via IP3Rs5, and lead to cell contraction depending on F-actin rearrangement. To test the effects of MCCs and IP3Rs on cell stretch and contraction, cell length was measured in embryos treated with GsMTx4 or XestoC (Fig. 6). Inhibition of MCCs inhibited the stretch and contraction of the cell at Row 2, but not Row 1 (Fig. 6b, e, f). In the case of the IP3R inhibition, the stretch and contraction at Rows 1 and 2 did not occur (Fig. 6c, e, f), indicating that there are functional differences between MCCs and IP3Rs in Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE. To further evaluate such differences, Ca2+ transients were observed from the induction of apoptosis to the end of extrusion in control embryos and embryos treated with GsMTx4 or XestoC (Fig. 7a, b, and Supplementary Movies 4–6). Inhibition of MCCs or IP3Rs did not block Ca2+ transients in apoptotic cells, but reduced Ca2+ transients in Row 1 (Fig. 7c). In addition, Ca2+ transients were not sustained in XestoC-treated embryos; instead, Ca2+ elevation for short periods (30.7 ± 18.6 s) was frequently observed in surrounding cells. Additionally, several differences in Ca2+ wave propagation were identified in surrounding cells (Fig. 7d, e). In control embryos, Ca2+ transients in Rows 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 started at approximately 5.7, 9.4, 14.8, 23.0, and 30.4 s after apoptosis induction, respectively. However, Ca2+ transients in Row 1 started at 5.7 s in XestoC-treated embryos, but at 15.9 s in GsMTx4-treated embryos, indicating that Ca2+ wave propagation was delayed. These results suggest that MCCs, but not IP3Rs, are involved in the initiation of Ca2+ transients in Row 1. The delay of Ca2+ transients was more significant in Row 2, and Ca2+ waves were not propagated in Rows 3–5. These data suggest that MCCs and IP3Rs have distinct roles in intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE: MCCs activate Ca2+ influx in all surrounding cells in which Ca2+ waves are propagated, whereas IP3Rs promote Ca2+ influx to high levels (Ca2+ transient) through CICR, particularly in Row 2 and the more outer rows of surrounding cells.

a Schematic illustration of the experimental time course for analyzing Ca2+ wave propagation. b Kymographs displaying the effects of MCC or IP3R inhibition on Ca2+ wave propagation upon irradiation with a 150 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser through a 40×/0.8 NA objective lens. Green and red regions in the kymographs show Ca2+ elevations in surrounding and apoptotic cells, respectively. The position of surrounding cells utilized for analysis is presented on the horizontal axis, and time is displayed on the vertical axis. At t = 0 (white dotted lines), the laser was irradiated onto the cell (labeled as “apo”) to induce apoptosis. In the control (DMSO-treated embryo), the Ca2+ wave propagated from the apoptotic cell to Row 4 approximately 45 s after laser irradiation. In this sample, Ca2+ elevation continuously occurred in both the apoptotic cell and Row 1 throughout the time-lapse imaging. In GsMTx4, Ca2+ elevation was observed in the apoptotic cell and Row 1. In contrast, with XestoC, Ca2+ elevation was restricted to the apoptotic cell. c Quantification of the peak GCaMP7 intensity in Row 1 of surrounding cells during ACE. Control: n = 28 cells from 11 embryos, GsMTx4: n = 32 cells from 9 embryos, and XestoC: n = 50 cells from 9 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01. d, e Effects of inhibitors on the speed (d) and duration (e) of Ca2+ wave propagation, which were evaluated in the apoptotic cell and multiple rows of surrounding cells. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test followed by post hoc Steel-Dwass test, ** p < 0.01, and ns. d Control: n = 5 embryos, GsMTx4: n = 6 embryos, and XestoC: n = 7 embryos. e Control: n = 17 embryos, GsMTx4: n = 9 embryos, and XestoC: n = 9 embryos.

Ca2+ waves regulate polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation

We next focused on cell behaviors after intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation. During apical cell extrusion (i.e., EDAC and ACE), surrounding cells fill the vacant space. We recently demonstrated that during EDAC in vitro, the Ca2+ wave induces F-actin accumulation in the cytosol and perinuclear regions of surrounding cells, leading to orchestrated movements of surrounding cells toward extruding cells27. We therefore investigated whether Ca2+ regulates collective movements and actin rearrangement during ACE. By analyzing the movement of vertices of surrounding cells located inside or outside the Ca2+ wave (Fig. 8a–h)27, we found that vertices inside the Ca2+ wave moved further than those outside the Ca2+ wave (Fig. 8b, c). Furthermore, surrounding cells inside the Ca2+ wave preferentially moved toward the extruding cells, but those outside the Ca2+ wave did not exhibit such polarized movements (Fig. 8b, c, e, f, Supplementary Fig. 4a). These phenotypes are consistent with those of in vitro cultured cells27. In contrast, F-actin accumulation was not observed in the cytosol and perinuclear regions. Instead, it accumulated at lamellipodia in multiple rows of surrounding cells inside the Ca2+ wave, which exhibited front-to-rear polarity toward extruding cells (Fig. 8i, j). Their structures are similar to those of cryptic-lamellipodia (c-lamellipodia) required for collective migration of cohesive cell groups during wound healing43,44,45. Formation of c-lamellipodia is regulated by cell adhesion and F-actin rearrangements44,45,46,47. E-cadherin-based adherens junctions (AJs) promote the directional formation of c-lamellipodia from trailing cells toward leading cells, helping the collective migration of leading and trailing cells45. Rac1 regulates Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization at the AJs, leading to the formation of c-lamellipodia44,45,46,47. To investigate whether the F-actin-enriched lamellipodia that formed in multiple rows of surrounding cells are c-lamellipodia, we inhibited the Rac1-Arp2/3 pathway or the formation of AJs in our experimental settings. Overexpression of RacN17 (dominant-negative mutant) or treatment with CK666 (Arp2/3 inhibitor) significantly reduced the formation rate and size of lamellipodia in surrounding cells and inhibited the polarized movements and collective behaviors of surrounding cells (Fig. 8d, g, h, k, l – n). Because knockdown of E-cadherin reportedly inhibits the directional formation of c-lamellipodia and collective migration towards their destination44, we knocked down cadherin1 (zebrafish E-cadherin) by using the morpholinos, which can phenocopy cadherin1 mutants48. Consistent with the previous report45 cadherin1 knockdown promoted excessive formation of lamellipodia even before apoptosis induction (Supplementary Fig. 5a). After apoptosis induction, the directional formation of c-lamellipodia was inhibited, and the directionality of polarized movement induced by Ca2+ wave propagation was reduced (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results suggest that Ca2+ wave propagation promotes the formation of c-lamellipodia, which is regulated by the Rac1-Arp2/3 pathway and adherens junction. This eventually leads to the collective migration of surrounding cells inside the Ca2+ wave towards the apoptotic cell, facilitating ACE.

a Schematic illustration of the displacement of cell vertices during cell extrusion. Arrows denote vertex movement from start to end. The length of the arrow indicates the displacement of the vertex movement. b Fluorescence images of displacements of surrounding cells over 1 min during (upper) and after (lower) Ca2+ wave propagation upon irradiation with a 150 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser through a 40×/0.8 NA objective lens. The left images comprise merged images captured at 0 or 60 s (green) and 60 or 120 s (magenta) after laser irradiation, respectively. The central and right images represent magnified views of the regions inside (marked by the red window) and outside (marked by the blue window) the Ca2+ wave in the left images. Scale bar: 50 µm. c The velocity of vertex displacement of surrounding cells inside (red, n = 12 cells) and outside (blue, n = 11 cells) the Ca2+ wave. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01, and ns. d Effects of RacN17 overexpression and CK666 treatment on the velocity of polarized movements. ContRNA: n = 39 from 3 embryos, and RacN17: n = 51 cells from 5 embryos. Control (DMSO): n = 39 from 3 embryos, and CK666: n = 81 from 5 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01. e Schematic illustration of the direction and vertex movements of surrounding cells during ACE. The arrow angle (θ) between the end and start vertex and the centroid of the apoptotic cell indicates the direction of the vertex movement. f Quantification of the direction of vertex movement. Red and blue histograms show surrounding cells inside and outside the Ca2+ wave, respectively. n = 314 and 313 from 15 embryos. g, h Effects of RacN17 overexpression (g) and CK666 treatment (h) on the direction of polarized movements inside the Ca2+ wave. ContRNA: n = 60 cells from 4 embryos. RacN17: n = 102 cells from 6 embryos. Control: n = 183 cells 4 embryos. CK666: n = 112 cells from 6 embryos. i Schematic illustration evaluating the formation rate and length of c-lamellipodia. To estimate c-lamellipodia formation, the length of the basal protrusion (BP) and apical contact (AC) were calculated as BP/AC. j – l The distribution of F-actin in different apical-basal z-planes at 0 and 60 s after irradiation with a 15 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens upon Control (j) RacN17 overexpression (k) and CK666 treatment (l). The upper panels show projections of apical-basal z-planes with blue-to-red colors as indicated on the right. Red asterisks indicate the laser focal point. The lower panels show schematic illustrations of F-actin distributions, projected with the apical (top) and basal (bottom) z-planes. The white area indicates c-lamellipodia. Scale bar: 10 µm. m Effects of RacN17 overexpression or CK666 treatment on the formation rate of c-lamellipodia. ContRNA: n = 4 embryos, RacN17: n = 6 embryos, Control (DMSO): n = 4 embryos, CK666: n = 6 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test followed by post hoc Steel-Dwass test, ** p < 0.01. n Effects of RacN17 overexpression or CK666 treatment on the length of c-lamellipodia. ContRNA: n = 21 cells from 4 embryos, RacN17: n = 39 from 6 embryos, Control: n = 25 cells from 4 embryos, CK666: n = 33 cells from 6 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01. o The formation rate of c-lamellipodia in surrounding cells inside (red) and outside (blue) the Ca2+ wave. n = 9 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Unpaired two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, ** p < 0.01. p Length of c-lamellipodia in surrounding cells inside (red) and outside (blue) the Ca2+ wave. Inside: n = 116 and outside: n = 33 cells from 9 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Welch’s t-test., ** p < 0.01 and ns.

Previous studies have proposed that Ca2+ signaling leads to Rac activation49,50. Therefore, we hypothesized that the Ca2+ wave promotes c-lamellipodia formation mediated by the Rac1-Arp2/3 pathway. C-lamellipodia formed in surrounding cells both inside and outside the Ca2+ wave, but the size and frequency of c-lamellipodia were significantly higher inside the Ca2+ wave than outside of it (Fig. 8o, p). Furthermore, inhibition of the Rac1-Arp2/3 pathway did not affect Ca2+ wave propagation (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that the Ca2+ wave acts upstream of c-lamellipodia formation during ACE. Importantly, reduction of c-lamellipodia formation by RacN17 overexpression or CK666 treatment inhibited the polarized movements of surrounding cells (Fig. 8d, g, h). Thus, our results suggest that the Ca2+ wave induces the polarized movements of surrounding cells through the formation of c-lamellipodia during ACE.

We have demonstrated that ACE involves MMCs (TRPC1 and Piezo)- and IP3R-mediated Ca2+ waves, as well as Rac1-mediated c-lamellipodia formation. However, the signaling link between them remains unclear. To bridge this gap, we inhibited common downstream signaling pathways of TRPC1 and Piezo—namely, those mediated by CaMKII, Ca²⁺/DAG-dependent PKC isoforms, and PI3K/AKT—to investigate their potential involvement in Rac1-mediated c-lamellipodia formation during ACE. Treatment of Kn93 (CaMKII inhibitor), Go6976 (PKC inhibitor), or Ly294002 (PI3K inhibitor) did not alter the formation of c-lamellipodia and polarized movements of surrounding cells (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that these pathways are not involved in ACE.

Activation of MMCs induces the activation of phospholipase C (PLC)51,52. The Ca2+-induced activation of PLC leads to the production of its downstream molecule, IP3, which subsequently promotes the release of Ca2+ from the ER51,53,54. Moreover, PLC directly interacts with Rac1 to regulate cell migration and cytoskeletal reorganization55,56. Therefore, we hypothesized that PLC acts as a mediator linking Ca²⁺ waves to Rac1-mediated c-lamellipodia formation during ACE. To test this possibility, we inhibited PLC using U73122 (PLC inhibitor). While treatment with U73343 (an inactive analog of U73122) had no effect on c-lamellipodia formation or polarized movement during ACE, U73122 treatment significantly inhibited both (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that PLC, activated by Ca²⁺ waves, promotes Rac1 activation to regulate the polarized movement required for ACE.

Previous studies have reported that Piezo 1-mediated Ca2+ influx activates calpain signal57,58, and that extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) is involved in the regulation of collective cell migration and ACE59,60,61. Like with Ca2+ waves, ERK activation waves are propagated from proximal to distal cells and initiated by mechanical stimuli60. Thus, it is possible that such signaling also contributes to the regulation of ACE. To test the possibility, we inhibited these signals, whereas treatment with calpeptin (calpain inhibitor) or trametinib (MEK inhibitor) did not affect c-lamellipodia formation and the polarized movements during ACE (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that calpain and ERK signaling are not involved in ACE at least in our experimental settings.

IP3Rs are required for polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation

We next investigated the relationship between Ca2+ waves mediated by MCCs and IP3Rs, and polarized movements during ACE. As described above, when MCCs or IP3Rs were inhibited, the Ca2+ wave was propagated to Row 1 or 2 (Fig. 2). Consistent with the ranges of wave propagation, polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation in the cells outside the Ca2+ waves (i.e., Row 2 and more outer rows of surrounding cells in these conditions) were diminished in embryos treated with Gd3+ and GsMTx4 (Fig. 9). However, in Row 1, in which Ca2+ transients occurred normally (i.e., inside the Ca2+ waves), polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation were unaffected (Fig. 9b–d). These results suggest that Ca2+ transients act upstream of polarized movements through c-lamellipodia formation.

a A representative polarized movement of a surrounding cell following the irradiation with a 150 nJ/pulse femtosecond laser through a 40×/0.8 NA objective lens is marked by white windows. The left images are wide-view fields, while the right images display magnified views of the regions enclosed by white windows in the top images. Polarized movements are highlighted by pseudo-colors on the initial (green) and post-Ca2+ wave (magenta) images. Scale bar: 25 µm. The arrow indicates the direction of the apoptotic cell. b – d Effects of inhibitors on Ca2+ wave-mediated polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation. b The velocities of polarized movements of surrounding cells inside and outside the Ca2+ wave. Control (DMSO), inside: n = 58, and outside n = 42 from 8 embryos. Gd3+, inside: n = 41, and n = 39 from 5 embryos. GsMTx4, inside: n = 58, and outside: n = 58 from 9 embryos. XestoC, inside: n = 58, and outside: n = 58 from 7 embryos. 2-APB, inside: n = 58, and outside n = 114 from 7 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01, and ns. c The frequency of c-lamellipodia inside and outside the Ca2+ wave. Control, inside: n = 117, and outside n = 33 from 5 embryos. Gd3+, inside: n = 21, and n = 38 from 7 embryos. GsMTx4, inside: n = 68, and outside: n = 68 from 10 embryos. XestoC, inside: n = 31, and outside: n = 28 from 6 embryos. 2-APB, inside: n = 52, and outside n = 67 from 6 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.01, and ns. d The size of c-lamellipodia inside and outside the Ca2+ wave. Control, inside: n = 115, and outside n = 33 from 5 embryos. Gd3+, inside: n = 21, and n = 38 from 7 embryos. GsMTx4, inside: n = 68, and outside: n = 68 from 10 embryos. XestoC, inside: n = 31, and outside: n = 28 from 6 embryos. 2-APB, inside: n = 52, and outside n = 67 from 5 embryos. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test followed by post hoc Steel-Dwass test, ** p < 0.01, and ns.

Similar to the effects of MCC inhibition, treatment with XestoC inhibited polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation in the cells outside the Ca2+ waves (i.e., Row 2 and more outer rows of surrounding cells in these conditions). However, inconsistent with the effects of MCC inhibition, IP3R inhibition significantly suppressed polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation in Row 1 (i.e., inside the Ca2+ waves) (Fig. 9b–d). Combinatorial inhibition of both MCCs and IP3Rs with 2-APB resulted in propagation of Ca2+ waves in Row 1, but inhibited polarized movements and c-lamellipodia formation in Rows 1 – 5 (Fig. 9b–d). These results suggest that IP3Rs play a crucial role in polarized movements through c-lamellipodia formation in all surrounding cells in which Ca2+ waves are propagated.

Ca2+ wave is independent from actomyosin ring contraction

The progression of ACE has been largely associated with contractile force generated by formation of the actomyosin ring6,22,23,27. To investigate whether the propagation of Ca2+ wave is related to actomyosin ring contraction during ACE, we inhibited myosin II activity using Y27632 (a ROCK inhibitor) or Blebbistatin (a myosin II inhibitor) to prevent actomyosin contraction, as shown previously28. In embryos treated with Y27632 or Blebbistatin, Ca2+ waves propagated normally (Supplementary Fig. 8), suggesting that Ca2+ wave propagation is independent of actomyosin ring contraction. To confirm this possibility, we performed laser ablation of a single contact edge between extruding and surrounding cells at different times (Supplementary Fig. 9a)62. When the contact edge was cut during actomyosin ring contraction (approximately 120 s after laser irradiation), the distance between the vertices of the contact edge greatly increased (Supplementary Fig. 9b, c), indicating that actomyosin ring contraction generates contractile tension, as shown previously63. By contrast, when the contact edge was cut during Ca2+ wave propagation (approximately 20 s after laser irradiation), the distance between the vertices of the contact edge did not change (Supplementary Fig. 9c), indicating that contractile tension is not loaded on the edge during Ca2+ wave propagation. These results suggest that Ca2+ wave propagation occurs before and is independent of actomyosin ring contraction.

Ca2+ wave generates mechanical force during ACE

In studies on cultured epithelial monolayers, the surrounding cells have been observed to generate traction force towards the apoptotic cell through collective cell migration63,64,65. Consistent with these studies, we observed that Ca2+ wave propagation promotes the polarized movement towards the apoptotic cell, but no contractile force was exerted on the contact edges. Thus, we assumed that the polarized movements immediately generate pushing force inward on the contact edges. To test this possibility, we used the in vivo force measurement method that we had previously established and measured the force generated in this process28. First, the center of a cell was irradiated with a femtosecond laser to induce apoptosis (Fig. 10a, left panel). Next, when the surrounding cells had collectively moved towards the apoptotic cell (approximately 30 s after laser irradiation), the femtosecond laser was irradiated at the center of the apoptotic cell at a frequency of 1 Hz to exert the impulsive force on the edges (Fig. 10a, right panel). Quantitative analysis of the extruding dynamics revealed that the polarized movements were counter-balanced by the force loading (Fig. 10b, c). Thereafter, when the laser irradiation was stopped, the polarized movements restarted (Fig. 10b, c), indicating that the impulsive force loading transiently counter-balanced the pushing force caused by the polarized movements. To quantify the mechanical force generated by the polarized movements, we evaluated the distance from the laser focal point (R) at different laser pulse energies (L) (see also Materials and Methods)28. As the impulsive force increased with L, the positive correlation between R and L indicates that R increases with an increasing impulsive force. We then quantified the P calculated by Eq. [1, 2] and summarized each data point (Fig. 10d). Based on this data, the P of the Ca2+-mediated polarized movements was estimated to be 1.08 ± 0.17 kPa, which is comparable to the P threshold reported in our previous study28.

a Schematic illustrations of force measurement using a femtosecond laser. The left panel shows cell extrusion induced by irradiation of the cell center with a femtosecond laser (15 nJ/pulse). The right panel shows that after Ca2+ wave-mediated polarized movements are initiated (approximately 30 s after laser irradiation), a series of laser pulses (10 − 100 nJ/pulse through 100×/1.25 NA objective lens) are loaded every 1 s at the center of the extruding cell. b, c Force measurement during Ca2+ wave-mediated polarized movements. b Red and yellow asterisks indicate the focal point of the laser to induce the extruding cell and loading of impulsive forces, respectively (representative of 38 independent samples). The white dotted line at 77 s shows the size of the extruding cell at 39 s. c Plot of the area of the extruding cell over time. An extruding cell was induced by laser irradiation at 0 s and gradually became smaller. By loading impulsive force, the size of the extruding cell slightly increased. After stopping the loading force, the extruding cell became smaller over time. Scale bar, 10 μm. d Pulse energy L dependence of threshold distance R to counter-balance the polarized movements. n = 38. e Force measurement during Ca2+ wave-mediated polarized movements in embryos treated with DMSO (control, n = 34) GsMTx4 (n = 25), XestoC (n = 20), or 2-APB (n = 31), and in trpc1-/- embryos (n = 21). One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test, ** p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.01. f Schematic illustration of Ca2+ wave-mediated polarized movements during ACE proposed in this study. Cells surrounding the extruding apoptotic cell are deformed. This deformation triggers elevation of intracellular Ca2+ via TRPC1 and CICR, resulting in cell shrinkage. Cell shrinkage induces deformation of surrounding cells located in Row 2. The increase of intracellular Ca2+ triggers actin rearrangement in the cells, which leads to formation of c-lamellipodia. This chain reaction occurs in multiple rows of surrounding cells, leading to Ca2+ wave-mediated polarized movements.

Finally, we quantified the P in embryos treated with several inhibitors and in trpc1 homozygous mutants to determine which molecules contribute to force generation during the polarized movements. To investigate the relationship between the P and MCCs, we measured the force in embryos treated with GsMTx4 and in trpc1 homozygous mutants (Fig. 10e). Compared with controls, P during the Ca2+ wave was significantly reduced in these experimental settings, suggesting that MCCs contribute to force generation during ACE. Similar results were obtained when we inhibited IP3Rs using XestoC or 2-APB. These results indicate that Ca2+ wave propagation generates mechanical force for ACE.

Taking all the data together, we propose a mechano-signal transduction mechanism of intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation, which facilitates ACE in zebrafish (Fig. 10f). First, the apoptotic cell shrinks accompanied by Ca2+ transients. Second, the interface between the apoptotic cell and Row 1 shifts toward the apoptotic cell, inducing cell stretching in Row 1. Third, this stretching initiates Ca2+ influx through MCCs and activates IP3R-mediated CICR, resulting in Ca2+ transients in Row 1. Fourth, the Ca2+ transients enhance cell contractions in Row 1. Fifth, the movement pulls Row 2, leading to stretching of Row 2. Finally, the third, fourth, and fifth processes are repeated in Rows 2 – 5. Sixth, these cells inside the Ca2+ waves collectively migrate toward the apoptotic cell via the Rac1-Arp2/3-dependent c-lamellipodia formation, generating 1 kPa force to facilitate ACE.

Discussion

In this study, we elucidated a previously unidentified stepwise mechanical process of intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation (Fig. 10f). Furthermore, we demonstrated that intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation initiates ACE by generating 1 kPa force before actomyosin ring construction.

MCCs, such as TRPC1 and PIEZO1, are activated by membrane stretching10,24,34,35. IP3, which moves through gap junctions, activates IP3Rs, which contribute to CICR (release of Ca2+ from the ER)15,27,37,38. During EDAC in mammalian cell cultures, inhibition of TRPC1, PIEZO1, IP3Rs, and gap junctions prevents propagation of Ca2+ waves toward distal cells27. This suggests that TRPC1, PIEZO1, IP3Rs, and gap junctions are involved in intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during EDAC. S1P signaling, which induces Ca2+ waves, regulates both ACE and EDAC in mammalian cells in vitro10,19. However, our pharmacological and genetic experiments showed that inhibition of trpc1, piezo1, itpr1a, and itpr1b prevented intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation during ACE, but inhibition of gap junctions, S1P signaling, or extracellular ATP did not. These observations suggest that ACE is regulated by a previously unidentified mechanism of intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation. Based on our findings, we propose that a chain reaction of mechano-signal transduction from proximal to distal cells through MCCs and IP3Rs (Fig. 10f) is at the core of intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation. This chain reaction occurs in several rows of surrounding cells. Although we do not fully understand how propagation stops, our data provide a hint: the deformation and polarized movement of cells gradually became smaller from Row1 to Row5 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Conversely, the time lag of deformation and polarized movement gradually became longer from Row1 to Row5 (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 4b). These findings suggest that mechano-signal transduction gradually decreases within the Ca2+ wave due to the gradual loss of MCC activation. Thus, it is crucial to investigate the relationship between a gradual decrease of mechano-signal transduction and termination of propagation during ACE.

In general, epithelial cells adhere to neighboring cells via E-cadherin-based adherens junctions and are mechanically coupled through cortical tension generated by actin and myosin II. Due to these core mechanical properties of epithelial sheets, when the contact edge is severed by laser ablation, the tension is released, and the vertices at that edge rapidly move apart—a phenomenon known as the recoil response66,67 Therefore, if the mechanical coupling mechanism that we propose here is important for Ca²⁺ wave propagation, it should be influenced by these core mechanical properties. However, inhibition of myosin II did not affect Ca²⁺ wave propagation (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). At first glance, this result appears to contradict the expected role of core mechanical properties. However, additional experiments suggest that epithelial cells in zebrafish embryos have distinct mechanical characteristics compared to other epithelial cells. In control embryos, when the contact edge was cut, instead of exhibiting a recoil response, the vertices at that edge rapidly moved toward each other, resulting in junction shortening (Supplementary Fig. 9). This suggests that the mechanical balance between cells is maintained by compressive forces (i.e., pressure) rather than cortical tension.

Interestingly, this reverse movement was not affected by treatment with Y27632 or Blebbistatin. However, expression of a constitutively active form of RhoA (RhoV14), which activates myosin II, induced a recoil-like response following junction ablation. Furthermore, when RhoV14 expression was combined with Y27632 treatment, the recoil-like response was inhibited (Supplementary Fig. 9). These results indicate that recoil movement depends on myosin II activation and that myosin II activity is intrinsically low in epithelial cells of zebrafish embryos.

Given this, it is not contradictory that inhibition of myosin II with Y27632 or blebbistatin failed to impact cell dynamics associated with Ca2+ wave propagation. In this tissue, basal myosin II activity is already low, and such inhibitors do not substantially alter cortical mechanics. Furthermore, when we manipulated the mechanical properties by RhoV14 overexpression (to activate myosin II) or latrunculin A treatment (to depolymerize actin), Ca2+ wave propagation was limited in both cases (Supplementary Fig. 9). These results confirm that the distinct mechanical properties of zebrafish epithelial cells influence Ca2+ wave propagation and suggest that Ca2+ transients induce cell deformations that are independent of myosin II but likely depend on actin remodeling, as observed in the driving force generation for cell deformation during cytokinesis68,69. Building on these findings, we believe that elucidating the detailed underlying mechanisms will be an important focus for future studies.

Our experiments demonstrate that the deformation of the surrounding cells by the induction of apoptosis triggers polarized movements through Ca2+ transients. After the wave propagation, the actomyosin ring forms around the apoptotic cell, generating mechanical force for ACE. Our quantitative analysis reveals that the polarized movements and the c-lamellipodia formation occur within 2 min immediately after apoptosis induction. Continuously, the actomyosin ring forms at around 2 min immediately after apoptosis induction, enabling the rapid extrusion of apoptotic cells from the epithelial sheet (within 15 min). Therefore, these two mechanisms are thought to switch stepwise, causing an efficient and rapid ACE that preserves epithelial integrity and homeostasis.

Zebrafish trpc1 encodes a protein containing 796 aa and six transmembrane domains. A tetramer of Trpc1 forms the mechanosensitive Ca2+ channel. In the trpc1 knockout mutants generated in this study, 13 bp are deleted in exon 4 of the trpc1 gene and the mutated trpc1 encodes a truncated protein containing only 168 aa, which lacks almost all functional domains of Trpc1 (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Consequently, we think this mutant is a knockout. Although the Ca2+ wave failed to propagate in trpc1 heterozygous and homozygous zebrafish mutants, we do not observe any phenotypical differences between these two mutants. Based on the failure of the Ca2+ wave to propagate in heterozygous mutants, the mutation may have a dominant-negative effect on Ca2+ wave propagation. To test the possibility, we overexpressed the truncated Trpc1 mutant in MDCK cells and stimulated the cells with Maitotoxin (TRPC1 agonist). Maitotoxin could induce strong Ca2+ influx in both cells un-overexpressed and overexpressed the truncated Trpc1 mutant, and the influx levels were comparable, indicating that the truncated Trpc1 mutant does not have a dominant-negative effect (Supplementary Fig. 10).

In contrast, two lines of evidence suggest a different possibility. First, Ca2+ wave propagation was significantly inhibited in mammalian cultured cells following shRNA-based knockdown of TRPC1, although the knockdown efficiency was approximately 50%27. Second, we observed cardiac failure in trpc1 homozygous embryos, but not in heterozygous trpc1 embryos (manuscript in preparation). These findings suggest that reduction of the amount of Trpc1 protein in the mutants leads to a functional defect of mechanosensitive Ca2+ channels and that the amount of Trpc1 protein is critical for Ca2+ wave propagation during cell extrusion.

This in vivo study utilized a femtosecond laser for apoptosis induction, nano-dissection, and mechanical force measurement. Through these approaches, we elucidated the mechanical properties of apoptotic and surrounding cells and the mechanotransduction signaling mediated by MCCs during ACE. Beyond ACE, MCCs are involved in various physiological processes, such as epiboly, dorsal closure, and wound healing, across different tissues and species2,10,20,24,25,26,27. However, their mechanical properties remain largely unknown. Therefore, our system provides a valuable tool for analyzing the mechanical characteristics of cells and measuring the forces involved in these physiological phenomena.

By using femtosecond laser impulsive forces, we estimated that approximately 1 kPa of force is generated by Ca2+ wave-mediated polarized movements; this is lower than contractile tension (4 kPa) generated by actomyosin ring contraction during cell extrusion. This quantitative approach enabled us to evaluate mechanical forces in vivo and revealed that Ca2+ wave propagation produces measurable mechanical outputs sufficient to drive coordinated cell movements. Our in vivo force quantification method thus provides a valuable framework for assessing physiological forces during dynamic tissue processes.

We show that the Ca2+ waves activated by MCCs and IP3Rs induce polarized movements mediated by the Rac1-Arp2/3-dependent c-lamellipodia formation. Nevertheless, the detailed molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Interestingly, it has been reported that Ca2+ signaling regulates Rac activity through several guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs)47,48,70. For instance, Tiam1, a Rac-specific GEF (an activator of Rac), binds with Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) in a Ca2+-dependent manner and promotes lamellipodial protrusions71,72, and the Tiam1-Rac pathway is activated by mechanical stimuli such as stretching72. Ras-GRF Exchange Factors (p140-GRF1 and p135-GRF2) also activate Rac in a Ca2+-dependent manner73. Furthermore, several actin-binding proteins can bind to Ca2+ via the EF-hand domain74,75. EF-hand domain-containing 2/Swiprosin1 (EFhd2/Swip-1) acts as a key crosslinker of WAVE-Arp2/3-actin polymerization, promoting lamellipodia formation76. During epithelial wound healing in Drosophila embryos, wound-induced Ca2+ elevations promote the accumulation of EFhd2/Swip-1 at a wound edge, stabilizing lamellipodial protrusions77. Notably, EFhd2/Swip-1 accumulates lamellipodia in several rows of the surrounding cells distant from the wound edge. These observations are reminiscent of our observations in this study. Therefore, identifying specific GEFs and actin-binding proteins and investigating their contributions to ACE would be of great interest in future research.

In conclusion, our findings reveal a previously unidentified regulatory mechanism of intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation that facilitates ACE. Ca2+ wave propagation is commonly observed in collective cell migration during development, wound healing, and cell competition2,35,65. Our observations provide insight into how Ca2+ waves induced by MCCs and IP3Rs are implicated in physiological phenomena involving collective cell migration.

Methods

Zebrafish experiments

Wild-type (WT) zebrafish, Tg[krt4:Lifeact-GFP], and Tg[krt4:GCaMP7] lines were used in this study. All zebrafish experiments were performed with the approval of the Animal Studies Committee of the Nara Institute of Science and Technology.

A model for ACE

We used the epithelial sheet near the animal pole of zebrafish embryos at 6 hours post-fertilization (hpf) as a model for ACE. At later developmental stages (24–48 hpf), anisotropy emerges, leading to regional differences in epithelial curvature, such as those observed in the head, lateral, and dorsal areas. These differences alter the mechanical environment of individual cells, resulting in variability in their mechanical properties. As a consequence, ACE induction by laser ablation becomes highly inconsistent at these stages, making them unsuitable for our experimental approach.

In contrast, embryos at 6 hpf retain a spherical shape. At this stage, epithelial cells near the animal pole are subjected to isotropic mechanical forces, whereas those near the equator experience anisotropic forces along the animal–vegetal axis. Based on this differential balance of tension and pressure, we determined that epithelial cells near the animal pole are most suitable for reproducible ACE induction. Furthermore, the spherical geometry at 6 hpf confines these cells to a single optical plane, enabling confocal laser microscopy to clearly visualize both the radial propagation of Ca2+ waves and the accompanying cellular dynamics.

Induction of apoptosis

An inverted microscope (IX71; Olympus) equipped to deliver femtosecond laser pulses from a regeneratively amplified Ti:Sapphire laser (800 ± 5 nm, 100 fs, <1 mJ/pulse, 32 Hz; Solstice Ace, Spectra-Physics) through an objective lens was used. To induce apoptosis, a single pulse of a femtosecond laser was focused on the center of an epithelial cell near the animal pole of embryos at 6 hpf, using 150 nJ/pulse through a 40×/0.8 NA objective lens or 15 nJ/pulse through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens.

Evaluation of laser-induced apoptosis

Immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase 3: Zebrafish embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C with 4% paraformaldehyde (4% PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed with PBS, and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in blocking buffer (Maleic acid buffer containing 0.5% DMSO, 0.1% Triton100, and 2% sheep serum). Anti-cleaved caspase 3 antibody (#9661; Cell signaling) was used at 1:100 in the blocking buffer, and a secondary antibody (anti-rabbit-Alexa594, #8889; Cell signaling) was used at 1:2000 in the blocking buffer. Immunofluorescence images were obtained and analyzed with the LSM980 (Carl Zeiss).

PI staining: Embryos at 6 hpf were dechorionated and mounted in holes formed in 1% low-melting agarose gel on 35 mm glass-bottom dishes containing fish water supplemented with 5 µg/mL PI (Nacalai Tesque). To induce apoptosis, a femtosecond laser pulse (15 nJ/pulse) was focused on the center of the epithelial cell through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens. PI fluorescence was observed using a confocal microscope (FV300; Olympus) with Fluoview software at the stage when cell extrusion was occurring.

Evaluation of ACE using annexin V

Embryos at 6 hpf were dechorionated and mounted in holes formed in 1% low-melting agarose gel on 35 mm glass-bottom dishes containing fish water supplemented with annexin V-FITC (Nacalai Tesque). To induce apoptosis, a femtosecond laser pulse (15 nJ/pulse) was focused on the centre of the epithelial cell through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens. Laser-induced apoptotic cells were classified as “extruded from the sheet” if (i) laser-irradiated cells were stained with annexin V-FITC, and (ii) annexin V-positive cells rounded up and were extruded from the epithelial sheet. Laser-induced apoptotic cells were classified as “remaining within the sheet” if (i) annexin V-positive cells did not round up and maintained contact with surrounding cells, and (ii) annexin V-positive cells remained within the sheet for longer than 30 min (apoptotic cells were extruded within 15 min in the control condition).

mRNA synthesis and injection

pCS2 carrying Lifeact-GFP (a gift from Dr. Noriyuki Kinoshita), GCaMP7 (a gift from Dr. Junichi Nakai), GCaMP7-CAAX, RFP, RacN17, or RhoV14 was used as a template for mRNA synthesis. mRNAs were synthesized using the SP6 mMessage mMachine System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). mRNAs were injected into the yolk of embryos at the one-cell stage78. To observe both F-actin and Ca2+ dynamics, Lifeact-GFP mRNA (100 pg) and GCaMP7 mRNA (100 pg) were co-injected into WT embryos at the one-cell stage or GCaMP7 mRNA (100 pg) was injected into embryos at the one-cell stage obtained from the Tg[krt4:Lifeact-GFP] line. To analyze the contribution of Rac1 to polarized movements, Lifeact-GFP mRNA (100 pg) and RacN17 mRNA (15 pg) were injected into embryos at the one-cell stage obtained from the Tg[krt4:Lifeact-GFP] line.

Treatment with inhibitors and morpholino injection

Embryos were developed until 5 hpf, treated with 100 µM Gd3+ (439770; Sigma-Aldrich), 4 µM GsMTx4 (095-05831; FUJIFILM WAKO Pure Chemical Corporation), 50 µM NS8593 (HY-110105; FUJIFILM WAKO Pure Chemical Corporation), 30 µM Yoda1 (21904; Funakoshi), 4 µM XestoC (244-00721; FUJIFILM WAKO Pure Chemical Corporation), 50 μM 2-APB (D9754; Sigma-Aldrich), 20 µM BTP-2 (ab144413; Abcam), 100 µM CK666 (SML0006; Sigma-Aldrich), 50 µM αGA (G8503; Sigma-Aldrich), 100 µM CBX (18240; Funakoshi), 10 µM JTE013 (J4080; Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µM SKI-II (10009222; Funakoshi), 10 U/ml apyrase (A7646; Sigma-Aldrich), 100 µM suramin sodium (sc-200833; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 3 µM U73343 (17339; Cayman Chemical Company), 3 µM U73122 (70740; Cayman Chemical Company), 50 µM calpeptin (S7396; selleck chemicals), 1 µM Trametinib (16292; Cayman Chemical Company), 10 µM Go6976 (13310; Cayman Chemical Company), Kn93 (21472; Cayman Chemical Company), LY294002 (125-04863; FUJIFILM WAKO Pure Chemical Corporation), 10 μM Y27632 (08945-84; Nacalai Tesque), 50 μM Blebbistatin (856925-71-8; Sigma-Aldrich), or 3 µM Latrunculin A (10010630; Cayman Chemical Company), for 60 min and then used in the following experiments. Non-treated or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle)-treated embryos were used as negative controls. Because treatment with 10 µM Y-27632 or 50 µM blebbistatin inhibits ACE29, experiments in this study were performed under these conditions.

piezo1-MO (5’-GAGCGACACTTCCACTCACATTCC-3’), itpr1a-MO (5’-ACTAGACAATTTGTCCACCATGGCA-3’), itpr1b-MO (5’-CATCTTGTCCGACATTTTGCTCCAC-3’), cadherin1-MO (5’-AAGCATTTCTCACCTCTCTGTCCAG-3’) were obtained from Gene Tools and used in this study. For knockdown, morpholinos (2 – 4 ng) were injected into the yolk of embryos at the one-cell stage. piezo1-MO induces morphological and lethal defects10. cadherin1-MO causes defects and delays in epiboly46. Injection of itpr1a-MO and itpr1a-MO induces lethal defects79. Therefore, in this study, we used the same morpholinos for these genes and confirmed that they produced phenotypes similar to those reported in the previous studies.

Observation of F-actin and Ca2+ dynamics during cell extrusion in zebrafish

Embryos expressing Lifeact-GFP and GCaMP7 were developed until around 6 hpf, dechorionated, and mounted in the holes of a gel made with 1% low-melting point agarose (Nacalai Tesque) on 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (Matsunami). As described previously28, a single pulse of a femtosecond laser (Solstice Ace, Spectra-Physics) at either 15 nJ/pulse or 150 nJ/pulse was precisely focused through a 100×/1.25 NA or 40×/0.8 NA objective lens (Olympus) onto the centers of epithelial cells situated near the animal poles of embryos at 6 hpf. F-actin and Ca2+ dynamics were observed for 1–7 min at 1 – 15 s intervals. At each time point, Z-stack images of the embryos (8–17 planes at 1 or 2 μm intervals) were also obtained.

Ca2+ imaging in zebrafish

Ca2+ dynamics in GCaMP7-expressing embryos were observed for 10 min at 1 s intervals using LSM 710 or LSM 980 inverted confocal microscopes (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 40×/1.2 NA objective lens. The cameras, filter wheels, and shutters were controlled using Zen software (Carl Zeiss). The frequencies of stochastic Ca2+ transients and waves were quantified using ImageJ/Fiji (NIH) and defined as the number of events per minute.

Cross-correlation analyses

To investigate the correlation between cell deformation and Ca2+ transients, GCaMP7-CAAX was used. By fusing the CAAX motif to GCaMP, the calcium sensor is targeted to the plasma membrane, allowing simultaneous visualization of both cell shape and calcium levels using a single probe. Ca2+ dynamics and cell deformation in GCaMP7-CAAX-expressing embryos were observed using an IX71 inverted confocal microscope (Olympus). A single pulse of a femtosecond laser at 15 nJ/pulse was precisely focused on the center of the epithelial cell through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens. Time-lapse imaging was performed at 1-second intervals for 5 minutes. The cross-correlation coefficient between the time-series data of cell deformation and Ca2+ transients was calculated using the cross-correlation function in R Studio.

CRISPR-based knockout of trpc1 in zebrafish

Guide sequences of trpc1 single-guide RNA targeting zebrafish trpc1 were designed based on exon 4 using the CRISPRdirect web server. The synthesized cgRNA for trpc1 (5’-UCCAUGGUGGUGGAAUACUCguuuuagagcuaugcuguuuug-3’) and tracrRNA (5’-AAACAGCAUAGCAAGUUAAAAUAAGGCUAGUCCGUUAUCAACUUGAAAAAGUGGCACCGAGUCGGUGCU-3’), both of which act as the single-guide RNA, were obtained from Fasmac. The cgRNA (100 pg), tracrRNA (100 pg), and Cas9 protein (500 pg) (GE-005; Fasmac) were co-injected into zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage. By screening germline-transmitted lines, a line carrying the 13 bp deletion in exon 4 (Fig. S7) was obtained and the F2 generations were used in this study. Genotyping was performed by PCR using sets of site-specific primers for the WT (trpc1-WT-L, 5’-TACAGAAGATTCAGAACCCAGAGTATT-3’; and trpc1-WT-R, 5’-CAGATCCATTTGTTCTCCTTCTATGA-3’) and mutant (trpc1-13del-L, 5’-TACAGAAGATTCAGAACCCACCA-3’; and trpc1-WT-R) alleles.

Effect of truncated Trpc1 mutant on Ca2+ influx

Using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies), GCaMP6S-MDCK27 were co-transfected with pcDNA3-truncated trpc1 mutant (168 aa) and pcDNA3-TagRFP, which is used to observe the transfected cells in time-lapse imaging. GCaMP6S and TagRFP signals were observed at 5 s intervals for 650 cycles (about 55 min) using LSM980 (Carl Zeiss) inverted confocal microscopy equipped with a 20×/0.8 NA objective lens. At around 160–161 (13.3 min) cycles of the time-lapse imaging, Maitotoxin (131-19011; FUJIFILM WAKO Pure Chemical Corporation) was added to 50 pM at the final concentrations.

Laser nano-dissection experiments

The system for the laser irradiation is the same as described above. To avoid inducing apoptosis or critical damage, we reduced the laser power from 15 nJ/pulse to 5–10 nJ/pulse. A single pulse of a femtosecond laser (5–10 nJ/pulse) was irradiated through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens onto the center of an epithelial cell to observe its mechanical responses. Using timelapse imaging at 1 s intervals for 180 seconds, we monitored changes in cell size and GCaMP7 intensity in both the irradiated and adjacent cells. Data at each time point were measured by ImageJ software (NIH). For data analysis, we used a sample in which transient cell deformation was induced by laser nano-dissection and excluded data when cell extrusion was induced.

Quantification of recoil velocities during the Ca2+ wave and actomyosin ring contraction

The system for the laser irradiation is the same as described above. Apoptosis was induced by the irradiation of the femtosecond laser (15 nJ/pulse) through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens. For cutting a contact edge between the apoptotic cell and adjacent cell, a single pulse of a femtosecond laser (15 nJ/pulse) was subsequently focused onto the contact edge at the timing of Ca2+ wave propagation (approximately 20 s after apoptosis induction) or actomyosin ring contraction (approximately 120 s after apoptosis induction). To evaluate the recoil velocities, dynamic changes of the single contact edge were observed at 1 s intervals after laser cutting. The displacement of the edge distance at each time point was measured by ImageJ software (NIH). The recoil velocities (Dt – D0 / Δt) were evaluated from the initial edge distance (D0) and recoiled distance (Dt) at a time after laser cutting (Δt).

Quantification of mechanical force in zebrafish

The system for the laser irradiation and induction of apoptosis is the same as described above. Next, when polarized movements started toward the extruding cell (approximately 20 s after laser irradiation), impulsive forces generated by a series of femtosecond laser pulses (10–100 nJ/pulse, 40–50 times at 1 s intervals) through a 100×/1.25 NA objective lens were loaded at the center of the apoptotic cell. Dynamic changes of F-actin were observed for 5–7 min at 1 s intervals. The area of the extruding cell (μm2) at each time point was measured by ImageJ software (NIH). In addition, the counter-balanced radius R (μm) of the extruding cell was measured. Using the measurement results and Eqs. [1, 2], the force generated in this process was estimated as described in the Results.

Quantification of impulsive force by atomic force microscopy

When the femtosecond laser is focused in the vicinity of an atomic force microscope cantilever, the total force F0 generated at the laser focal point is estimated from the bending movement of the cantilever27. A tipless silicon AFM cantilever (thickness, 4.0 µm; length, 125 µm; width, 30 µm; force constant, 42 N/m; resonance frequency, 330 Hz in air) (TL-NCH-10; Nano World, Neuchatel, Switzerland) was magnetically attached to the AFM head (NanoWizard 4 BioScience; JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany), which was mounted on the stage. The cantilever was immersed in pure water, and a laser was focused 10 µm away from the cantilever tip. The bending motion of the cantilever induced by laser irradiation was directly detected and monitored using an oscilloscope (DP4104; Tektronix, Beaverton, OR). The magnitude of the cantilever deflection was estimated from the oscillation amplitude. Based on this estimation, the impulsive force generated at the laser focal point F0 is related to the incident laser pulse energy L by the following equation:

Assuming that F0 propagates spherically in the vicinity of the laser focal point, the impulsive force F0 generated at the laser focal point as a unit of pressure P is expressed by the following equation:

Statistical analysis

Graph generation and statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel or R software. Experimental data were tested for normality of distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Differences were analyzed with an unpaired Student’s t-test with Welch’s correction (two-tailed) or Mann-Whitney U-test for parametric or non-parametric comparison of two groups, respectively, one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey-Kramer test for parametric multiple comparisons, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test followed by post hoc Steel-Dwass test for non-parametric multiple comparisons, or chi-square test for frequency comparisons. The sample sizes and statistical tests are provided in the figure legends. When p < 0.05, we consider the difference to be statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Owing to the large file size, the raw image data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Researchers interested in accessing these data are encouraged to contact Takaaki Matsui (corresponding author) or Sohei Yamada. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gilland, E., Miller, A. L., Karplus, E., Baker, R. & Webb, S. E. Imaging of multicellular large-scale rhythmic calcium waves during zebrafish gastrulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 157–161 (1999).

Antunes, M., Pereira, T., Cordeiro, J. V., Almeida, L. & Jacinto, A. Coordinated waves of actomyosin flow and apical cell constriction immediately after wounding. J. Cell Biol. 202, 365–379 (2013).

Clapham, D. E. Calcium signaling. Cell 131, 1047–1058 (2007).

Leybaert, L. & Sanderson, M. J. Intercellular Ca(2+) waves: mechanisms and function. Physiol. Rev. 92, 1359–1392 (2012).

Matsui, T. Calcium wave propagation during cell extrusion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 76, 102083 (2022).

Kuipers, D. et al. Epithelial repair is a two-stage process driven first by dying cells and then by their neighbours. J. Cell Sci. 127, 1229–1241 (2014).

Duszyc, K. et al. Mechanotransduction activates RhoA in the neighbors of apoptotic epithelial cells to engage apical extrusion. Curr. Biol. 31, 1326–1336 (2021).

Ohkura, M. et al. Genetically encoded green fluorescent Ca2+ indicators with improved detectability for neuronal Ca2+ signals. PLoS One 7, e51286 (2012).

Riedl, J. et al. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat. Methods 5, 605–607 (2008).

Eisenhoffer, G. T. et al. Crowding induces live cell extrusion to maintain homeostatic cell numbers in epithelia. Nature 484, 546–549 (2012).

Maroto, R. et al. TRPC1 forms the stretch-activated cation channel in vertebrate cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 79–85 (2005).

Lewis, R. S. The molecular choreography of a store-operated calcium channel. Nature 446, 284–287 (2007).

Zhang, S. L. et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9357–9362 (2006).

Liou, J. et al. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 15, 1235–1241 (2005).

Ambudkar, I. S., de Souza, L. B. & Ong, H. L. TRPC1, Orai1, and STIM1 in SOCE: Friends in tight spaces. Cell Calcium 63, 33–39 (2017).

Evans, W. H. & Martin, P. E. Gap junctions: structure and function (Review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 19, 121–136 (2002).

Kato, Y., Omote, H. & Miyaji, T. Inhibitors of ATP release inhibit vesicular nucleotide transporter. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 36, 1688–1691 (2013).