Abstract

Cerebral malaria (CM) is a severe complication caused by Plasmodium falciparum infection, leading to persistent neurological impairments in survivors. To understand the complex mechanisms and investigate advanced diagnostic and treatment strategies targeting human CM, we utilize Plasmodium coatneyi-infected male rhesus macaques, a non-human primate model closely resembling P. falciparum infection in humans. Through differential gene expression analysis, our study demonstrates methylene blue’s efficacy in reversing the detrimental effects of infection on the brainstem. Furthermore, by comparing our brainstem dataset from P. coatneyi-infected Macaca mulatta with two additional transcriptomic datasets (P. coatneyi-infected M. mulatta blood and P. falciparum-infected human blood), we identify nine genes associated with CM severity. Most of these genes are expressed in neutrophils, indicating their potential as blood biomarkers for diagnosing P. falciparum-induced fatal CM. This research highlights the necessity for new CM treatments and reveals promising biomarkers that could improve diagnosis and prognosis in affected individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria imposes a significant burden in many emerging economies, with approximately 600,000 deaths annually1. Malaria is caused by Plasmodium spp., an intracellular protozoan transmitted to their intermediate human host by female Anopheles mosquito. While the vast proportion of Plasmodium spp. infections are asymptomatic2,3,4, some infections progress to uncomplicated malaria (UM) or severe malaria5. Patients with UM often experience periodic bouts of fever, chills, headache, profuse perspiration, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and anaemia6. The development of severe malaria, often due to the delayed or ineffectual treatment of UM, is a constellation of interconnected complications including but not limited to; hyperparasitemia, severe anaemia, acute kidney injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and cerebral malaria (CM)7,8. Clinically, severe malaria is a medical emergency, constituting an increased risk of death at clinical presentation relative to others in the community with malaria9. While regularly over-diagnosed in clinical practice, severe malaria remains a major cause of preventable childhood death in sub-Saharan Africa, with the most fatal syndrome being CM, characterized by unrousable coma9.

CM, caused by P. falciparum, develops through several key mechanisms, including the intravascular sequestration of infected red blood cells (RBCs) and impaired blood flow, which disrupts the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and increases its permeability10,11,12,13. This disruption triggers neuroinflammation, with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, leading to further brain damage and contributing to the severe neurological symptoms characteristic of the disease, often resulting in death in the absence of treatment14,15,16,17. Even with appropriate anti-malarial treatment (parenteral artesunate), mortality in African children still reaches 8.5%16 with up to 25% of pediatric survivors experiencing enduring neurologic sequelae18,19,20,21,22,23,24. These life-long post-CM neurocognitive disorders comprise impairment in cognitive functions, motor skills, visual coordination, seizures, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder25,26. Limited treatment options and the rise of artesunate resistance in Africa27, necessitates the development of new therapies targeting CM.

One therapeutic option showing promise against P. falciparum is methylene blue (MB)28,29,30,31. In addition to its effectiveness in blocking transmission and treating uncomplicated P. falciparum human malaria, a study conducted using a murine model revealed promising results in the rapid treatment of fatal experimental CM32. To confirm the therapeutic utility of MB against CM prior to human trials, we utilized Plasmodium coatneyi-infected rhesus macaques, a non-human primate model that closely resembles P. falciparum infection in humans. P. coatneyi was first discovered in Anopheles hackeri mosquitoes from Malaya and subsequently found in the blood of Macaca fascicularis in the Philippines33,34. P. coatneyi has then been used as a model for P. falciparum infection as they share the following features: (i) both species are tertian parasites, with morphological similarities during the intraerythrocytic stages33,34, (ii) infected RBCs possess knob-like structures, which play a role in their cytoadherence to endothelial cells35,36, (iii) late-stage intraerythrocytic parasites (trophozoites and schizonts) sequester in the brain microvasculature35,37,38,39, (iv) rosette formation is observed between infected and uninfected RBCs40,41, and (v) P. coatneyi-infected rhesus macaques develop CM comparable to clinical features in P. falciparum-infected humans, including severe complications (i.e., anemia, hypotension, coagulopathy and renal dysfunction) with neurological symptoms ranging from inactivity to total lethargy35,36,42,43,44.

In addition to the urgent need for new therapeutics targeting CM, there is also a need for sensitive, rapid, and practical methods to prognosticate CM and differentiate it from other causes of encephalopathy. Biomarkers have been sought for the early and accurate diagnosis of CM, as well as for prognosticating treatment outcome. These biomarkers can be categorized into predictive (risk of CM onset), diagnostic (identification of CM patients) and prognostic (risk of death/recovery/permanent complications) for fatal and non-fatal CM45. However, obvious ethical and practical issues associated with clinical studies on children with CM remain barriers to the identification of useful CM biomarkers.

In this study, we used P. coatneyi-infected rhesus macaque model with and without MB treatment to identify genes specific to the brainstem that were differentially regulated by the infection. MB treatment effectively reversed these infection-specific effects. Through comparison with published CM datasets, we further narrowed down our candidate list to 9 potential blood biomarkers that could be used to segregate non-fatal from fatal CM caused by P. falciparum. These biomarker candidates could serve not only for the rapid and accurate diagnosis of patients and inform their clinical management, but also for monitoring the effectiveness of new adjunctive therapies in CM.

Results

Methylene blue treatment regimen of P. coatneyi-infected macaques and whole-tissue RNA-seq

Eighteen rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were used in this study: (i) 4 uninfected macaques (Pcoat− MB−), (ii) 5 coatneyi-infected and untreated macaques (Pcoat+ MB−), (iii) 3 coatneyi-infected macaques treated with 6 mg/kg MB (Pcoat+ MB6mg/kg), (iv) 3 coatneyi-infected macaques treated with 10 mg/kg MB (Pcoat+ MB10mg/kg), and (v) 3 coatneyi-infected macaques treated with 17 mg/kg MB (Pcoat+ MB17mg/kg) (Fig. 1a). Up until Day 7, all groups underwent peak and trough cycles of parasitemia, most likely due to the sequestration of late-stage parasites (Fig. 1b). In our model, infected animals typically begin to develop clinical symptoms around Day 7 post-infection, although signs like decreased appetite and anorexia were often noted around Day 4 to 5 post-infection46. MB treatment was administered intravenously twice daily from Day 7 to Day 10 post-infection when CM develops (above 15% parasitemia) in this infection model, thus representing the clinical setting where patients usually seek treatment after developing symptoms46. From Day 7 onwards, the Pcoat+ MB− group had sustained parasitemia levels exceeding 106 parasites/mm3 RBCs. Tissues (brainstem, thalamus, cerebellum, heart, kidney, and liver) were harvested for RNA-seq after death or euthanasia on Day 8 for untreated group and Day 14 for MB-treated groups. For the Pcoat+ MB+ groups, macaques with treatment failure were euthanized immediately. Although the 6 mg/kg MB dose was initiated at a lower parasitemia level (17.97 ± 1.33%) and cleared parasites at a slower rate compared to higher MB doses, the treatment was successful for all three macaques in the group, with their clinical signs normalized by the time of euthanasia (Supplementary Data 1). In contrast, treatment was initiated at higher parasitemia levels in the Pcoat+ MB10mg/kg (36.17 ± 1.86%) and Pcoat+ MB17mg/kg (38.30 ± 2.01%) groups. Some macaques in these higher-dose groups did not manage to fully clear their parasites and displayed clinical signs at the point of euthanasia.

a Experimental groups: uninfected and untreated group (Pcoat− MB−), infected and untreated group (Pcoat+ MB−), infected and treated with different MB doses groups (Pcoat+ MB6mg/kg, Pcoat+ MB10mg/kg and Pcoat+ MB17mg/kg). Created in BioRender. Malleret, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/9np9vxb. b Parasitemia follow-up during P. coatneyi infection (2 weeks) with the MB treatment regimen between D7 and D11 post-infection, when treated groups are given two doses of MB daily intravenously. The experimental endpoint for the untreated group is indicated with a red arrow, while the euthanasia periods for treated groups are marked with arrowheads, each color code corresponding to the respective treatment group. Purple, 6 mg/kg MB; Green, 10 mg/kg MB; Blue, 17 mg/kg MB. Parasitemia levels are shown as mean ± SEM from biological replicates with n = 4 Pcoat− MB−, n = 5 Pcoat+ MB−, and n = 9 Pcoat+ MB+.

We then conducted comparative histopathological analysis of the Pcoat+ MB+ and Pcoat+ MB− groups (Supplementary Data 2). The result indicated that MB treatment effectively resolved parasite sequestration, CNS hemorrhage and edema, and cerebellum Purkinje cell degeneration. However, it did not resolve axonal or neuronal injury, renal damage, hepatic injury, cardia injury and vasculitis. These findings suggest that MB treatment alleviated the brain pathology associated with CM development.

From the 18 macaques, RNA-seq was successfully performed on 98 samples (6 tissue samples per animal), yielding a total of 1.49 billion reads with a median of 15.1 million reads per sample. The reads were aligned to the M. mulatta genome assembly, in which 81% and 57.8% of the reads aligned to the genome and known transcripts, respectively. The difference in the percentage of reads mapped to the genome assembly vs. known transcripts indicates that the reference set of transcripts is incomplete. The transcript abundances were then summarized into gene abundances; a total of 28,382 genes were quantified from 67,643 known transcripts.

Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis of gene expression in different tissues during P. coatneyi infection

We first measured pairwise inter-sample distances of the samples using Euclidean distance metric as a distance metric and generated a hierarchical cluster heatmap to visualize the expression of the 7403 most variable genes across all samples (Fig. 2a). The dendrogram showed that the brain tissues (brainstem, thalamus, and cerebellum) clustered together and had distinct gene expression from the heart, liver, and kidney samples. Within each tissue, the samples were loosely clustered by infection and treatment groups, indicating that gene expression was influenced primarily by tissue type, then secondarily by infection and treatment. A subsequent Jensen-Shannon divergence analysis confirmed the same pattern (Supplementary Fig. 1a). To determine whether the infection and treatment affected gene expression in the tissues, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) of the samples separately in each tissue. In the brain tissues, the gene expressions of the Pcoat+ MB− samples were distinct, whereas those of the Pcoat+ MB+ and Pcoat− MB− samples were indistinguishable from each other, and this is only apparent in the brainstem (Fig. 2b). The schematic diagram illustrated the similarities in the structure of thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum between macaque and human brains (Fig. 2c). Despite the macaque brain being 4.8 times smaller than the human brain, non-human primates and humans share numerous anatomical, perceptual, cognitive, and behavioral similarities, which make the macaque brain a suitable model to study human CM47,48,49,50. Apart from the brain tissues, we also examined heart, kidney and liver tissues. While no obvious differences in gene expression were observed in the heart and kidney (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c), the liver samples from Pcoat+ MB− group did not meet RNA sequencing quality control criteria and were therefore excluded from the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1d). As a result, our study could not conclude on the liver physiopathology in P. coatneyi-infected rhesus macaques.

a Heatmap display of the expression of 7403 most variable genes in all samples assayed by RNA-seq. The matrix of gene expression in TPM units was log1p transformed and scaled to z-score on the rows (genes). Hierarchical clustering of rows and columns was performed using complete linkage algorithm with Euclidean distance metric. b PCA of RNA-seq samples in brainstem, thalamus and cerebellum. c Schematic diagram comparing the macaque brain and human brain, indicating the brainstem (yellow), thalamus (red) and cerebellum (blue). Figure created in the Mind the Graph platform at www.mindthegraph.com, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/.

Methylene blue treatment resolves hemozoin sequestration and neural damage in the brain during P. coatneyi infection

To support our transcriptomic observations with histological evidence, we examined hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of brain tissues (Fig. 3). In Pcoat+ MB− group, there was extensive pathological involvement characterized by marked sequestration of hemozoin-laden erythrocytes across multiple brain regions. The cerebrum exhibited expanded Virchow-Robin spaces densely packed with hemozoin-containing erythrocytes (Fig. 3a), while the cerebellum showed degenerating Purkinje cells surrounded by abundant hemozoin pigment (Fig. 3c). The brainstem also displayed widespread vascular congestion with numerous hemozoin-laden erythrocytes and hemorrhage (Fig. 3e). In contrast, MB-treated animals demonstrated a notable absence or marked reduction of hemozoin deposition in these brain regions. Treated animals showed decreased hemorrhage and the presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the cerebrum (Fig. 3b), reduced Purkinje cell degeneration without hemozoin accumulation in the cerebellum (Fig. 3d), and minimal neuronal swelling with substantially diminished vascular pathology and hemozoin sequestration in the brainstem (Fig. 3f). These histological findings correlate with the reversal of infection-driven gene expression changes following MB treatment and underscore the drug’s therapeutic potential in alleviating cerebral malaria pathology.

a Brainstem (Pcoat+ MB−): Focally extensively, there is marked hemorrhage, within which erythrocytes contain hemozoin pigment. b Cerebrum (Pcoat+ MB−): Virchow-Robin space surrounding a cerebral vessel is markedly expanded by extravasated erythrocytes, with erythrocytes containing hemozoin pigment. c Cerebellum (Pcoat+ MB−): Pürkinje cells are angulated, retracted and condensed, surrounded by abundant edema, indicating varying degrees of degeneration. Diffusely, the cerebellar vasculature contains small accumulations of hemozoin. d Brainstem (Pcoat+ MB6mg/kg): Multifocally neurons display intracytoplasmic chromatin clumping and are bounded by gliosis and satellitosis. e Cerebrum (Pcoat+ MB6mg/kg): Neurons are multifocally angulated and hypereosinophilic, suggestive of degeneration and necrosis, with mild gliosis and satellitosis. f Cerebellum (Pcoat+ MB6mg/kg): Pürkinje cells are multifocally angulated and bounded by glial cells and mild to moderate amounts of edema, with foci of hemosiderin. g Brainstem (Pcoat+ MB10mg/kg): Multifocally neurons contain intracytoplasmic ceroid or lipofuscin and are bounded by minimal gliosis and satellitosis. h Cerebrum (Pcoat+ MB10mg/kg): Multifocally within the neuropil, there is mild gliosis and satellitosis, and perivascular spaces are expanded by edema. i Cerebellum (Pcoat+ MB10mg/kg): Pürkinje cells multifocally contain minimal intracytoplasmic ceroid or lipofuscin. j Brainstem (Pcoat+ MB17mg/kg): Multifocally neurons contain intracytoplasmic ceroid or lipofuscin and are bounded by minimal gliosis and satellitosis. k Cerebrum (Pcoat+ MB17mg/kg): Neurons are rarely angulated and hypereosinophilic, suggestive of degeneration and necrosis. Multifocally, mild gliosis and satellitosis are observed. l Cerebellum (Pcoat+ MB17mg/kg): Pürkinje cells are multifocally angulated and bounded by scattered glial cells and mild edema. Scale bar represented 100 µm. MB-treated photomicrographs are representative of pathology observed across the three animals in each dosage group. Pathology in Pcoat+ MB− is supported by extensive retrospective and prospective studies46,118. Created in BioRender. Malleret, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/00ghavt.

We also assessed pathology in the heart, kidney, and liver (Supplementary Fig. 2). In the heart and kidney of untreated animals, there was clear evidence of infected red blood cell sequestration, vascular congestion, and tissue damage (Supplementary Fig. 2a, c). MB-treated animals exhibited reduced severity of these features, although some cellular alterations such as cardiomyocyte karyomegaly and tubular hemoglobin casts persisted (Supplementary Fig. 2b, d). In the liver, abundant hemozoin accumulation was detected in untreated animals (Supplementary Fig. 2e), underscoring the role of hemozoin in driving liver pathophysiology. MB treatment led to a noticeable reduction in hemozoin deposits, although complete clearance was not achieved (Supplementary Fig. 2f). This suggests that, although MB alleviates liver damage and inflammation caused by P. coatneyi infection, residual effects may persist. Taken together, these results indicate that MB treatment mitigates systemic pathological damage, with the most pronounced therapeutic benefit observed in the brain, in agreement with our transcriptomic findings.

Methylene blue treatment reversed brainstem gene expressions that were modulated by P. coatneyi infection

To further interrogate the differences in brain gene expression due to infection and treatment, we identified DEGs in the brain tissues of the different experimental groups (Fig. 4a). By comparing the samples from Pcoat− MB− and Pcoat+ MB− groups, we identified specific genes modulated by the P. coatneyi infection. The most profound effect was observed in the brainstem (801 DEGs) (Supplementary Fig. 3a), compared to the cerebellum (493 DEGs) and thalamus (173 DEGs). To investigate whether the treatment with MB had any effects on brainstem gene expression, we first compared the different MB-treated groups in a pairwise manner. However, we managed to identify very few DEGs in the brainstem, with the comparison between Pcoat+ MB6mg/kg vs. Pcoat+ MB17mg/kg groups yielding only 16 DEGs (Supplementary Data 3). From this, we decided to pool the different MB-treated groups into a Pcoat+ MB+ group for downstream analyses. We then compared the Pcoat+ MB+ and Pcoat+ MB− samples and found that many genes were modulated by the treatment, most of these occurring in the brainstem (1709 DEGs) (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The top 50 genes modulated by MB treatment are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3c. Remarkably, the brainstem gene expressions of the Pcoat+ MB+ vs. Pcoat− MB− samples were similar, with only two DEGs identified, suggesting that MB treatment was able to reverse the effects of the infection on brainstem gene expression. Furthermore, out of the 801 genes modulated by the infection, 574 of them (72%) were also modulated by the MB treatment (Fig. 4b). A heatmap of the 574 genes modulated by both infection and treatment highlights that the genes that were differentially expressed during the infection returned to their basal levels (i.e., levels in uninfected samples) following treatment (Fig. 4c). Altogether, P. coatneyi infection affects the expression of many genes in brain tissues, especially the brainstem, but this reverses upon treatment with MB.

a Gene expression comparisons between the experimental groups in different brain tissues. DEGs were selected based on adjusted p < 0.05 (two-sided Wald test in DESeq2 for estimating the false discovery rate) and >2-fold change in expression. b Venn diagram showing overlap of 574 genes modulated by infection (Pcoat+ MB− vs, Pcoat− MB−) and MB treatment (Pcoat+ MB+ vs. Pcoat+ MB−) in the brainstem. c Heatmap representation of 574 DEGs that were modulated by infection and normalized by MB treatment in the brainstem. Created in BioRender. Malleret, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/lee54gw.

Brainstem genes that were modulated during infection and treatment are central to the neuroinflammation signaling pathway

To explore the biological relevance of the 574 brainstem genes modulated by infection and reversed by MB treatment, we analyzed those genes with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) and found that granulocyte adhesion and diapedesis, as well as IL-10 signaling were the two most significantly affected pathways, although their direction of regulation could not be predicted (Fig. 5a). Other top pathways included the complement system, acute phase response signaling, and macrophage phagocytosis; these pathways were upregulated during infection and were also reversed by MB treatment.

a Top 20 pathways enriched in the 574 DEGs with length of the bars indicating statistical significance (p-value) of enrichment (unadjusted p-value from a right-tailed Fisher’s exact test performed using IPA software) and color shade representing IPA prediction of up or down regulation of the pathway (z-score > 0 for upregulation, z-score <0 for down regulation, z-score = 0 for no change, z-score = NA if the direction of regulation cannot be predicted). b Pathways found to be overlapping and forming the most significant pathway cluster by IPA. c Representation of the neuroinflammation signaling pathway based on the list of 574 DEGs modulated by both infection and MB treatment in the brainstem. Data were analyzed with the use of QIAGEN IPA (QIAGEN Inc., https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/IPA)98.

Additionally, these enriched pathways share many common genes, and IPA clustering showed that 12 out of the top 20 pathways were closely interrelated (Fig. 5b). One cluster of these pathways involves pathways that play a role in acute phase response like IL-6, IL-10, TREM1, and Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Another pathway cluster involves leukocyte extravasation, particularly granulocytes and monocytes. Connecting these two pathway clusters is the neuroinflammation signaling pathway. The neuroinflammation pathway shares genes in common with both the acute phase response pathway and granulocyte/leukocyte extravasation pathway, suggesting that neuroinflammation involves an overlap of the two phenomena. Pivotal to the neuroinflammation pathway is NF-κB (a DEG), which directly interacts with many other genes, including a few other DEGs (Fig. 5c). Notably, three DEGs in this pathway (MMP9, TNF-α and IL-1β) have been implicated to play a role in BBB disruption, a hallmark of CM25. It is also worth mentioning that CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein), a transcription factor that promotes neuron survival51, was significantly downregulated during infection and reversed by MB treatment. Two other relevant DEGs are β-secretase and NOX, both of which have downstream effects causing neuron damage. Altogether, the neuroinflammation signaling pathway was significantly affected by the infection, but these changes are reversible by MB treatment. Many DEGs in this pathway contribute directly to BBB disruption and neuronal damage, potentially contributing to the development of CM. Our data do not exclude the possibility of a concomitant role of CD8+ T cells in neuroinflammation52,53.

Identification of cerebral malaria biomarkers common to P. coatneyi and P. falciparum infections

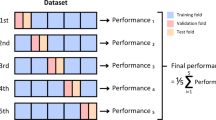

Our dataset revealed 574 DEGs in the macaque brainstem that were modulated during P. coatneyi infection and reversed by MB treatment. Among these, we were interested in identifying blood biomarkers useful for diagnosing human CM caused by P. falciparum. To achieve this, we compared our transcriptomics dataset with two other published datasets: (i) RNA-seq of blood from P. coatneyi-infected macaques54, and (ii) microarray analysis of blood from P. falciparum-infected humans (Fig. 6a)55. Comparisons with the Cordy et al. dataset enabled us to narrow down the DEGs in our brainstem dataset to those also differentially expressed in the blood of P. coatneyi-infected macaques. This is important to identify easily measurable blood biomarkers. Additionally, comparisons with the Thiam et al. dataset helped us identify biomarkers relevant to human CM (Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Summary of the comparative transcriptomic analysis between our data, Thiam et al. (2019) and Cordy et al. (2019). Figure created on Biorender.com. Created in BioRender. Malleret, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/8pe774a. b Venn diagram showing overlap of DEGs in the three different datasets. c Gene expression heatmap of the 9 candidate biomarkers across the different datasets. For the Thiam et al. (2019) dataset, children (child icon) and adult (no icon) patients were distinguished. Created in BioRender. Malleret, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/3ksn98f.

We identified 9 genes (MAG, IL1RN, LCN2, S100A8, CD177, S100A9, CHIT1, MMP9, and NFE2) as potential blood biomarkers for CM caused by P. falciparum and P. coatneyi infections. These 9 genes were found to be differentially expressed in all three transcriptomic datasets examined (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Data 4). Gene expression heatmaps of the 9 genes clearly show overexpression in Pcoat+ MB− macaques vs. Pcoat− MB− and Pcoat+ MB+ macaques (our dataset), in humans diagnosed with CM vs. mild malaria55, and in acutely-infected macaques vs. pre-parasitemia macaques (Fig. 6c)54. Although pediatric and adult CM patients develop different degrees of brain swelling and brainstem herniation was only described in children, we observed no differences in expression of the 9 genes in the two age groups of the Thiam et al. dataset. This suggests that these genes could be used as CM blood biomarkers for both adult and pediatric patients. Based on the expression levels of these 9 genes, we determined the Euclidian distances between the samples in each dataset and visualized them in a multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot. Samples from the same experimental group clustered together in the Thiam et al. and Cordy et al. datasets (Fig. 7a). In our dataset, the Pcoat+ MB+ samples grouped with the Pcoat− MB− samples, distinctly segregating from the Pcoat+ MB− samples (Fig. 7a). To assess the predictive capabilities of the biomarkers in predicting CM, we performed a discriminant analysis using the OPLS-DA method. The model’s predictive ability (estimated by Q2Y) was highest for the macaque datasets (brainstem and blood), and it performed well for the human blood dataset, with only a single mild malaria sample misclassified as CM (Fig. 7b top panels, Supplementary Fig. 5). Random permutation tests also showed that the model’s predictive ability was better than most randomly permutated models (total of 100 competing models trained on randomly permutated responses) (Fig. 7b bottom panels).

a Multidimensional scaling (MDS) visualization of Euclidean distances between samples based on log expression levels of the nine biomarker genes. b Performance of OPLS-DA models in discriminating between samples of different biological conditions based on the expression levels of the 9 selected biomarker genes. The performance metrics R2Y and Q2Y measure the proportion of biological label (Y) dispersion explained by the model on the training data (R2Y) and in 7-fold cross-validation (Q2Y). The biological labels were permuted 100 times to evaluate model overfitting and the metrics pR2Y and pQ2 represent the proportion of opls models trained on randomly permuted labels that have better predictive performance than the model trained on the actual labels based on R2Y and Q2Y metrics respectively. High values of R2Y and Q2Y are desirable indicating better representation of the biological conditions by the biomarker genes, whereas low values of pR2Y and pQ2Y are desirable indicating less overfitting.

We then classified our macaque brainstem samples using our 9 biomarkers and the public CM gene signature (BCL2L13, NFIX, S100P, S100A8, RETN, PGLYRP1, BIRC5, IL1R2, MCOLN1, MED25, FUCA1, LZTFL1, SLC25A38, RPA1, RPIA, ACVR1, ATP6V0E2, SPSB3, and PIGQ)56. The public CM gene signature distinguished samples with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.92 (95% CI 0.75–1.1), correctly classifying 92% of the macaque brainstem samples (Fig. 8a). In contrast, our nine biomarkers achieved a perfect classification, with an AUC of 1.00 (95% CI 1–1), correctly classifying 100% of the samples (Fig. 8b). When comparing the meta score distributions, the public CM gene signature showed a statistically significant separation between groups (p = 0.0044), whereas our biomarkers demonstrated even stronger discriminatory power, with a more significant difference (p = 0.00023). After evaluating our macaque brainstem samples, we next assessed the performance of our biomarkers in public human malaria datasets comprising healthy individuals, UM, severe malarial anemia (SMA), and CM. When applied to these datasets, our biomarkers generated the highest meta score for CM, effectively distinguishing it from all other conditions, with statistically significant differences observed across all groups: CM vs SMA (p = 2e-09), CM vs UM (p = 2.7e-07), and CM vs healthy controls (p = 2.4e-11) (Fig. 8c, Supplementary Fig. 6).

The MetaIntegrator R package99 was used to compute the meta-scores of the macaque brainstem RNA-seq samples (representing biological replicates n = 4 Pcoat− MB−, n = 5 Pcoat+ MB− and n = 9 Pcoat+ MB+) based on a public CM gene signature: BCL2L13, NFIX, S100P, S100A8, RETN, PGLYRP1, BIRC5, IL1R2, MCOLN1, MED25, FUCA1, LZTFL1, SLC25A38, RPA1, RPIA, ACVR1, ATP6V0E2, SPSB3, PIGQ56, and b the nine identified CM biomarkers. The meta-scores were displayed as violin plots grouping samples by infection/treatment (right panels). P-values comparing group means on the violin plots were computed using Wilcoxon rank sum test (two-sided). The meta-scores were used for classifying samples as associated with cases or controls and the detection threshold was varied to generate a receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curve (left panels). c The nine identified biomarkers were used with MetaIntegrator R package to analyze the public gene expression datasets where human subjects were infected with P. falciparum. Violin plot of the meta-scores of n = 16 UM, n = 26 SMA, n = 131 CM and n = 17 healthy controls derived from public microarray datasets GSE1124, GSE33811, GSE72058, GSE116306 and GSE117613, computed using the set of nine candidate biomarker genes. P-values comparing group means on the violin plots were computed using Wilcoxon rank sum test (two-sided test, unadjusted p-values comparing each condition against CM).

Given these promising results, we next sought to determine whether our biomarkers were specific to CM-associated encephalitis. Encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain, can occur in various contexts beyond CM, including viral encephalitis, autoimmune encephalitis, and bacterial infections57. To assess the specificity of our biomarkers for CM encephalitis, we therefore compared their performance using a dataset from West Nile Virus (WNV)-induced encephalitis (Supplementary Fig. 7). Violin plot analysis revealed a statistically significant difference between asymptomatic WNV infection and WNV encephalitis (p = 0.0059). However, the magnitude of this difference was relatively small compared to the striking separation observed between CM and other malaria groups (SMA, UM, and healthy controls). These results suggest that while some immune-related gene expression may overlap across encephalitic conditions, the expression pattern of our 9 biomarkers remains distinctively elevated in CM.

Taken together, using only this set of 9 genes, we were able to discriminate CM cases from non-CM cases, supporting the use of these genes as biomarkers for CM diagnosis. Furthermore, we were able to rank each biomarker candidate based on their importance in discriminating CM cases. Their rankings are (from highest to lowest overall score of all three datasets): S100A9, MAG, IL1RN, S100A8, CD177, LCN2, MMP9, NFE2 and CHIT1 (Supplementary Data 4). The higher-ranked genes are more promising candidates as blood biomarkers for CM identification and should be prioritized in future research.

Signature biomarker expression in immune subsets of cerebral malaria with neutrophils as primary contributors

To better understand the immune cell dynamics and gene expression profiles associated with CM, we performed immune cell profiling and analyzed the expression of 9 biomarkers in the immune cell subsets of the brainstem (Fig. 9a). CIBERSORT analysis of brainstem samples revealed the distribution of various immune cell types, providing insights into the immune landscape during CM. One of the most notable findings from this analysis was that activated mast cells showed a significantly higher abundance in the Pcoat+ MB− group compared to both Pcoat− MB− and Pcoat+ MB+ groups. Although no statistically significant differences were found, a trend toward higher abundance of several immune cell types, including macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, resting NK cells, plasma cells, and resting CD4 memory T cells, was observed in the Pcoat+ MB− group when compared to the other 2 groups. These trends suggest an increased immune activation in the brainstem in response to infection, particularly in the early stages of CM before the intervention with MB treatment.

a CIBERSORT analysis of brainstem samples. Bars and whiskers represent mean and standard error, respectively, of the % of total immune cells contributed by an immune cell subset. P-values comparing treatment groups were computed using Wilcoxon rank sum test (two-sided test, nominal unadjusted p-values). b Average expression of 9 signature genes in various immune cell subsets, data obtained from Human Protein Atlas.

In addition to immune cell profiling, we further explored the expression of the nine signature biomarkers across various immune cell subsets by utilizing data from the Human Protein Atlas (Fig. 9b). This approach allowed us to assess the expression patterns of these biomarkers in different immune cell types, providing a clearer picture of their potential roles in the immune response to CM. Our results revealed that, with the exception of MAG and NFE2, these biomarkers were predominantly expressed in neutrophils. This finding highlights the significant role of neutrophils in the immune response to CM, suggesting that these cells are not only key players in the immune surveillance of the brain but may also contribute directly to the pathogenesis of the disease. The strong expression of the signature biomarkers in neutrophils further underscores their potential as key contributors to the inflammatory processes that drive CM progression. Given their central role in immune responses and their abundance in the brainstem, neutrophils emerge as promising targets for future research into therapeutic interventions for CM.

Discussion

The diagnosis and treatment of CM pose significant challenges due to its rapid onset and high mortality rate6. Currently, CM diagnosis relies on clinical symptoms defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), often leading to delayed treatment9. To address this issue, we aimed to identify specific blood-based biomarkers for rapid CM prognosis and diagnosis.

In our study, we established a CM model using P. coatneyi-infected rhesus macaques and incorporated MB as a treatment. Splenectomized rhesus macaques were used to establish a reliable and reproducible model, as they enable consistent high parasitemia levels, allowing for the study of hyperparasitemia, multi-organ disease, and CM, which are less predictable in spleen-intact animals. Studies have shown that sequestration of infected RBCs occurs in P. coatneyi-infected rhesus macaques, with lesions present in multiple organs such as the brain, kidney, heart, and liver, which are consistent with findings observed in our study38,58. These observations further support the validity of our model for studying CM pathogenesis. When P. coatneyi-infected rhesus macaques were treated with MB during CM progression, the symptoms resolved, with the brain being the most affected region, as evidence by histopathological analysis.

However, the use of splenectomized animals introduces important immunological considerations. The spleen plays a critical role in the clearance of infected RBCs, regulation of immune cell trafficking, and orchestration of both innate and adaptive responses during malaria infection. Its absence may alter immune cell distributions, particularly monocytes and T cells59, which may impact inflammatory responses systemically and within tissues60. Therefore, while the splenectomized model offers a robust platform for studying CM pathology and therapeutic effects, comparisons with spleen-intact human infections should be interpreted with caution. Future studies incorporating spleen-intact models may help refine our understanding of immune-mediated mechanisms in CM and improve translational relevance.

We further investigated the effects of CM on different areas of the brain and identified specific genes that were regulated by infection and reversed by MB treatment. Our analysis focused on the brainstem, where transcriptomic changes in the Pcoat+ MB+ group were restored, with the DEG profile closely resembling that of Pcoat− MB− group. In contrast, histopathological examination of the brainstem showed only partial reversal of pathology across all treatment doses. This apparent discrepancy may arise from two factors: first, the limited spatial and static nature of histological analysis, which captures only a small tissue section; and second, the irreversible aspects of certain neuronal damage, such as necrosis, where structural integrity cannot be restored. By comparison, transcriptomic profiles provide a broader and more dynamic view, capturing functional compensation and neural plasticity. Thus, even in the presence of residual structural damage, molecular pathways that support recovery and homeostasis appear to be reactivated following treatment.

The brainstem is of particular importance in the context of CM as it controls essential body functions, and its involvement can lead to fatal outcomes, especially in pediatric patients25. Hence, the in-dept analysis of brain tissues focusing on the brainstem would enhance our understanding of pediatric CM61,62. To extend the relevance of our findings, we compared our brainstem dataset with two additional blood datasets, one from P. falciparum-infected humans and another from P. coatneyi-infected rhesus macaques. This comparative analysis led to the identification of 9 blood biomarkers associated with CM severity. Using this gene signature, we successfully classified CM cases from healthy controls, mild malaria, non-CM severe malaria and non-malarial encephalopathies, such as WNV encephalitis. These findings suggest that our biomarkers could serve as potential diagnostic markers for fatal CM caused by P. falciparum.

Notably, seven out of nine biomarkers are predominantly expressed by neutrophils, while NFE2 is highly expressed in neutrophils, but not predominantly – suggesting a potential involvement of neutrophils in CM. In Table 1, we summarized reported associations between the biomarker candidates, neutrophil function, and CM. Gene expression analysis of the top 50 genes modulated by MB treatment further revealed that many of these genes are highly expressed in neutrophils. Among these, we identified several genes, including LILRA3, LILRA5, CD177, CSF3R, CEBPB, FCAR, IL1RN, LCN2, MMP9, S100A8, S100A9, SECTM1, SOCS3, and SPI1, which are closely linked to neutrophil function. Additionally, Pcoat+ MB− samples exhibit a higher abundance of neutrophils in the brainstem compared to the Pcoat− MB− and Pcoat+ MB+ groups, although this difference is not statistically significant. Collectively, these findings raise the question of whether neutrophils may play a crucial role in CM pathogenesis.

Supporting this, neutrophil counts frequently increase in malaria patients, and their granules contain antimicrobial proteins that, although effective against pathogens, can also cause tissue damage when released systemically63,64. Elevated levels of neutrophil granule proteins, along with a neutrophil-associated blood transcriptomic signature, have been linked to severe malaria65,66. NETs have been found in the neurovasculature of fatal CM cases, colocalizing with infected RBCs, implicating them in vascular pathology67. Despite their harmful potential, neutrophils may also have protective roles. Studies in Gambian children have identified neutrophil proteins like cathepsin G and MMP9 correlate to malaria protection68. Evidence from studies on matrix-producing neutrophils also points to a potential protective role, where neutrophils contribute to the skin’s extracellular matrix during injury, reinforcing its mechanical properties and promoting barrier function69. This protective role could be inferred in the context of CM, where neutrophils may act to protect the BBB from disruption caused by the disease. Our findings support the hypothesis that neutrophil-associated biomarkers could be useful for CM detection. In addition to neutrophils, other factors such as proinflammatory cytokines and neuronal β-secretase were found to be involved in neuroinflammation and BBB disruption in CM52,70. The overall findings suggest that neuroinflammation and neutrophil-induced immunopathology contribute significantly to CM progression.

The identified blood biomarkers have potential diagnostic value, with CD17771,72,73, S100A874,75, S100A974,75, and LCN276 being particularly relevant due to their association with neutrophil activation and endothelial interactions. These biomarkers could be easily detected through antibody staining and flow cytometry analysis. Other biomarkers such as IL1RN, CHIT1, MAG, and NFE2 show promise but require further investigation. While our study primarily supports the diagnostic application of these biomarkers, further research is needed to explore their predictive and prognostic potential. Predictive biomarkers could help identify patients at risk of developing CM, allowing for timely treatment. Prognostic biomarkers, on the other hand, could help identify patients with differential treatment responses and inform post-CM neurological complication risks. It is worth noting that our study focused on adult rhesus macaques, and while CM severity and outcomes may differ between adults and children, our gene expression analysis across different age groups did not reveal significant variations in the identified biomarkers, suggesting their potential usefulness across all age groups.

Additionally, our findings also demonstrate the significant potential of MB as adjunct or alternative therapy for fatal CM. MB is a promising antimalarial with multiple mechanisms of action, including the inhibition of glutathione reductase and hemozoin formation, which complicate the development of resistance77,78,79,80,81. By targeting the complex catalytic cycle, MB generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), affecting both sexual gametocytes and asexual stages82,83,84,85,86. MB has shown efficacy across various malaria models and drug-resistant strains, particularly when combined with artemisinin, and is capable of crossing the BBB87,88. This is particularly relevant in the context of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum infections, which pose a growing threat in Africa, necessitating urgent alternative treatment options16,27,89. Furthermore, MB’s metabolite, azure B, may further enhance its anti-inflammatory effects, providing added therapeutic value for treating malaria complications90,91.

In our study, despite better peripheral parasite clearance in MB-treated animals, some showed clinical deterioration with overlapping CM symptoms, which may be related to delayed treatment initiation or other host factors. CM progresses rapidly, with the swift onset of severe neurological symptoms and hyperparasitemia, making early intervention critical. The animals in the higher dose groups were treated later in disease progression, when the therapeutic window had already narrowed. Despite close monitoring, the desired threshold for treatment initiation was sometimes missed due to the swift onset of parasitemia, making it difficult to synchronize treatment timing across groups. These findings suggest that earlier administration of MB, even at lower doses, may be more beneficial than delayed treatment at higher doses, emphasizing the importance of timing in therapeutic efficacy against CM. However, there is a need for caution and further research before considering MB as a therapeutic alternative to artemisinin-based therapies. While MB remains a promising compound, especially in the context of drug resistance, our results highlight both its potential and its limitations in this preclinical model.

In conclusion, our study elucidates the role of neutrophils and neuroinflammation in CM pathogenesis. We have identified blood biomarkers that show promise for CM diagnosis and highlight the potential of MB as a therapeutic option. However, further validation studies are necessary to confirm the diagnostic, predictive, and prognostic value of these biomarkers and to enhance their clinical utility.

Methods

Animals and parasites

In this study, nine splenectomized rhesus macaques (Indian origin), males aged 7 to 14 years old, were randomly assigned to each of the three dosage groups (three monkeys per group). A prior study of five untreated male rhesus macaques (aged 6 to 16 years old) served as infected untreated controls, and four spleen-intact male rhesus macaques (aged 8 to 9 years old) served as uninfected controls. Only male animals were used to maintain consistency with historical controls and reduce sex-related variability. P. coatneyi (Hackeri strain) infections were established in experimental monkeys by intravenous inoculation of 5 × 106 infected erythrocytes obtained from infected donor monkeys. Animal procedures were approved by the AFRIMS IACUC (#12-08) and conducted in strict accordance with Thai laws, including the Animals for Scientific Purposes Act, B.E. 2558 (A.D. 2015), the Animal Welfare Act, and all applicable U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, U.S. Department of Defense guidelines, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council 2011). The AFRIMS facility is fully accredited by AAALAC International.

P. coatneyi parasitemia follow-up

Animals were monitored continuously, and blood smears were performed thrice daily before Day 6 post-infection, then increased to eight times daily from Day 6 onwards until experimental endpoint. Blood smear samples were fixed in methanol and stained with Giemsa (Merck), then were examined under oil-immersion objective for parasite quantification and staging. Smears were considered negative if no parasites were found in 50 fields of thick smears (approximately per 1000 leukocytes). Parasites were counted per number of leukocytes (per 100–300 leukocytes) or erythrocytes (per 500–10,000 erythrocytes).

P. coatneyi-infected macaques’ symptoms, methylene blue treatment regimen and clinical monitoring

The P. coatneyi-infected macaques developed the different following symptoms: anorexia, lethargy, leukocytosis, vomiting, anemia, reticulocytosis, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, azotemia and hypochloremia. When parasitemia reached 15% (7 to 9 days post-infection), the treated groups were intravenously injected with 6 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or 17 mg/kg of MB twice daily for 4 days. Infected untreated animals were euthanized on Day 8 post-infection. MB-treated animals were euthanized upon treatment failure, or on the 5th or 6th day after treatment initiation in cases of treatment success. Treatment failure was predetermined as: (i) parasitemia decline of less than 75% with clinical deterioration 48 h after treatment initiation, (ii) parasitemia decline of less than 99% by Day 3 after treatment initiation, or (iii) moribund behavior, unstable respiratory status, or unstable blood pressure at the end of Day 3 after treatment initiation.

Tissue fixation, processing, and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining

All tissues collected for histopathology were collected within minutes of euthanasia, trimmed into small sections (approximately 2–5 cm), and fixed in 10% buffered formalin at a 1:10 tissue:formalin ratio. Formalin was refreshed after 24 h to prevent formalin pigment formation. Lesioned tissues were sampled at both the lesion center and margins, including adjacent normal tissue; unaffected tissue from the same organ was also collected for comparison. Fixed tissues were trimmed into 5 mm dice and processed using an automated tissue processor (SLEE medical, Mainz, Germany) as follows: dehydration (70% Isopropanol for 1 h, 95% Isopropanol for 1 h × 3 times, and 100% Isopropanol for 1 h × 3 times), clearing (Xylene substitute (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h × 3 times) and paraffin infiltration (molten paraffin for 30 min × 2 times).

Formalin fixed tissue samples were prepared for histopathological evaluation as H&E sections, following the method described by Prophet et al.92. Briefly, sections were cut at 4 μm using a semi-automated rotary microtome (RM2245, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). The tissue sections were mounted onto poly-L-lysine coated microscope slides and baked at 60 °C for 14–18 h. H&E staining was performed using standard protocols. Histological evaluation was performed by both a board-certified veterinary pathologist (EL) and by a board-certified medical pathologist (GT) using Olympus BX43F bright field microscopes (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Tissues were evaluated qualitatively for histopathologic changes in comparison with control animals and excluding any background lesions observed in the AFRIMS macaque colony through experience or described in the literature93. Representative sections of the cerebrum were included for histological evaluation; however, the thalamus is not distinctly visualized in these sections due to its deep anatomical location, which requires targeted dissection and specific orientation for optimal visualization in standard H&E preparations. Histopathological lesion was scored by consensus on a 0–5 scale: 0 = within normal limits, 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = marked, 5 = severe.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Brain, heart, kidney, and liver tissues were collected immediately post-mortem in multiple repeats of 1 mm2 squares and preserved in RNAlater (Sigma-Aldrich). Total RNA was isolated by homogenizing in TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and performing double extraction with guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform followed by a QIAGEN RNeasy Micro clean-up procedure. 500 ng of total RNA was subjected to Ribo-Zero (Illumina) ribosomal RNA depletion, after which Lexogen SENSE Total RNA-seq libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA samples with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) below 5.5 as analyzed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer were processed according to the protocol for FFPE samples. All samples were subjected to an indexed paired-end sequencing run of 2 × 151 cycles on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 system (25 samples/lane). RNAseq data have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE265864).

RNAseq pre-processing

The raw reads were aligned to the Refseq Macaca mulatta genome assembly (NCBI accession number: GCF_000772875.2_Mmul_8.0.1) using STAR aligner94. The reads were also quantified against transcript sequences obtained from the same Refseq assembly using Salmon95 in mapping-free (alignment-free) mode to quantify transcript abundance. Transcript abundances were then summarized into gene abundances using the tximport R/Bioconductor package96. Normalized gene abundances were expressed in transcript per million (TPM) after trimmed mean of M values (TMM) normalization.

Transcriptomic analysis

To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), raw gene abundances were analyzed with the DESeq2 R/Bioconductor package97. DEGs were selected based on adjusted p < 0.05 and > 2-fold change in expression. The various sets of DEGs from the multiple comparisons between experimental groups are listed in Supplementary Data 5. Heatmaps were generated to display the log transformed expression level of a gene across samples normalized to a Z-score. For any gene, log expression = log2(TPM + 1.0) (a pseudo-count of 1.0 is added to avoid negative values) and the Z-score is calculated as \({{{{\boldsymbol{Z}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}}=\left({{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}}-{{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}\right)/{{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}\), where \({{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}}\) is the log expression in sample i, and µ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of log expression across all samples displayed in the heatmap. QIAGEN Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was used to identify biological pathways enriched with the DEGs and to generate pathway networks98.

PCA was performed using the R package FactoMineR on the matrix of log expression (log2(TPM + 1.0)), with samples on the rows and genes on the columns. Each tissue was analyzed separately by PCA. Genes with interquartile range (IQR) > 0.001 were used. A set of 3615 DEGs between FFPE and non-FFPE samples and a set of 1524 DEGs between subjects were excluded to avoid the clustering of samples by the tissue processing method or by the individual in the PCA. The set of genes used for PCA was also used to analyze pairwise distances between samples measured by Jensen-Shannon divergence, and generate a hierarchical clustering of the samples. A matrix of normalized gene abundances in TPM was provided to the function JSD available in the R package, philentropy, to compute the Jensen-Shannon divergence. Additionally, a heatmap of the 7403 most variable genes across all samples was generated. The matrix of gene expression in TPM units was log1p transformed and scaled to z-scores on the rows (genes). Hierarchical clustering of rows and columns was performed using the complete linkage algorithm with the Euclidean distance metric.

Comparative transcriptomics

Gene expression profiling from our brainstem samples was compared with two other published transcriptomics datasets from the GEO database, GSE116306 and GSE103259. A summary of their samples can be found in Supplementary Data 654,55. The list of DEGs between cerebral malaria and mild malaria patients was obtained from Supplementary Table S1 of Thiam et al., 2019 who used a one-way ANOVA method to identify DEGs while adjusting for covariates, such as age, gender, and leukocyte counts. A total of 1060 differential probes corresponding to 853 genes were identified below FDR threshold of 10%. When a gene had multiple probes, the probe with a lower p-value was selected. Out of 853 DEGs, 829 gene symbols matching those in our dataset were finally selected to visualize normalized probe expression levels in a heatmap. For the dataset of Cordy et al., 2019, raw RNA-seq counts were analyzed with DESeq2 R/Bioconductor package to identify DEGs between time points T1 (pre-parasitemia) and T2 (acute infection) paired on the subjects. 2174 DEGs identified below FDR threshold of 5% were selected for comparison with our dataset. Normalized counts computed by DESeq2 were used in heatmap visualizations.

Venn diagram was used to compare our list of DEGs modulated by infection and normalized by MB treatment in the brainstem with the lists of DEGs in the abovementioned datasets. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) method implemented in the R/Bioconductor package, ropls, (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ropls.html) was used to test the ability of biomarker genes identified in this study to distinguish between samples by their biological condition, i.e., uninfected vs. infected, untreated vs. infected, treated in the present study, mild vs. severe malaria in Thiam et al., 2019 and pre-parasitemia (T1) vs. acute infection (T2) in Cordy et al., 2019. The matrix, X, of normalized gene abundances with samples on the rows and the biomarker genes on the columns was provided to the opls function of the ropls package with parameters predI = 2 (derive 2 PCA components) and permI = 100 (perform 100 random permutations of the class labels to evaluate predictive performance) to predict the biological condition (Y). The performance of an opls model was assessed by the metrics R2Y and Q2Y which are the proportion of Y dispersion explained by the model on the training data (R2Y) and in 7-fold cross-validation (Q2Y). A permutation test was used to evaluate model overfitting, and the metrics pR2Y and pQ2 were computed representing the proportion of opls models trained by randomly permuting the class labels that have better predictive performance than the model trained on the actual class labels based on R2Y and Q2Y metrics, respectively.

Gene signature-based classification of samples

The MetaIntegrator R package99 was used for evaluating gene biomarkers in the present RNA-seq dataset and public microarray and RNA-seq datasets. For comparisons between CM ad non-CM malaria cases, the following public databases were included: GSE1124, GSE33811, GSE72058, GSE116306, GSE117613, E-MTAB-6413, GSE5418, GSE119150, GSE52166, GSE34404, GSE7000, GSE156791, GSE181179, GSE50957, GSE94916, GSE15221, GSE64338, and PRJEB45911. For comparison between asymptomatic WNV infection and WNV-induce encephalitis, GSE46681 was used.

For each biomarker gene, a signature score was computed to evaluate whether the gene was differentially expressed between cases and controls across various studies included in the meta-analysis. An effect size of a gene was computed in each dataset as Hedges adjusted g based on its mean expression and pooled and weighted standard deviation in cases and controls. A summary effect was computed using a random effect model where the inter-dataset variation was modeled as a random effect estimated by the DerSimonian-Laird method. Given a set of biomarker genes, a meta-score was computed for every sample where positive or negative meta-scores would indicate association of a sample with cases or controls respectively based on the biomarker genes. The meta-score was computed as the geometric mean of the expression of biomarker genes (when only genes up-regulated in cases vs. controls were defined as biomarker) or the difference between geometric means of up and down regulated genes (when both up- and down-regulated genes in cases vs. controls were defined as biomarker) normalized to a z-score to center the samples around zero. The meta-scores of samples were displayed as violin plots by sample group. The meta-scores used for classifying samples as associated with cases or controls and receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves generated by varying the detection threshold.

CIBERSORT analysis

To analyze immune cell proportions in the brainstem samples, the matrix of gene expression in TPM units was analyzed with CIBERSORT R script (version 1.02)100 using the LM22 gene signature to deconvolute the proportions of 22 human immune cell types.

Inclusion and ethics statement

All collaborators who fulfilled the authorship criteria defined by Nature Communications have been appropriately included as authors, recognizing their vital contributions to both the study’s design and its implementation. Roles and responsibilities were clearly defined and agreed upon prior to the start of the project. The research did not involve activities that would be restricted or prohibited in the setting of the researchers, and does not result in stigmatization, incrimination, discrimination or other personal risk to participants. Ethical approval was secured from recognized ethics review board, ensuring that all procedures adhered to appropriate ethical standards. Local and regional research relevant to our study was taken into account in citations.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data underlying the findings of this study are available as supplementary files included in this publication. The RNAseq data have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE265864. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available in Supplementary Data 7. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding author, Benoît Malleret (benoit_malleret@nus.edu.sg).

References

World malaria report 2024: addressing inequity in the global malaria response. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024.

Greenwood, B. M. Asymptomatic malaria infections–do they matter? Parasitol. Today 3, 206–214 (1987).

Bousema, T., Okell, L., Felger, I. & Drakeley, C. Asymptomatic malaria infections: detectability, transmissibility and public health relevance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 833–840 (2014).

Ashley, E. A. & White, N. J. The duration of Plasmodium falciparum infections. Malar. J. 13, 500 (2014).

WHO Severe and complicated malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80, 1–50 (1986).

Ashley, E. A., Pyae Phyo, A. & Woodrow, C. J. Malaria. Lancet 391, 1608–1621 (2018).

Mousa, A. et al. The impact of delayed treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria on progression to severe malaria: a systematic review and a pooled multicentre individual-patient meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 17, e1003359 (2020).

WHO Severe malaria. Trop. Med. Int. Health 19, 1–131 (2014).

White, N. J. Severe malaria. Malar. J. 21, 284 (2022).

Avril, M., Benjamin, M., Dols, M. M. & Smith, J. D. Interplay of Plasmodium falciparum and thrombin in brain endothelial barrier disruption. Sci. Rep. 9, 13142 (2019).

White, N. J. et al. Pathophysiological and prognostic significance of cerebrospinal-fluid lactate in cerebral malaria. Lancet 1, 776–778 (1985).

Adams, Y. et al. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 variants induce cell swelling and disrupt the blood-brain barrier in cerebral malaria. J. Exp. Med. 218 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20201266

MacPherson, G. G., Warrell, M. J., White, N. J., Looareesuwan, S. & Warrell, D. A. Human cerebral malaria. A quantitative ultrastructural analysis of parasitized erythrocyte sequestration. Am. J. Pathol. 119, 385–401 (1985).

Idro, R., Jenkins, N. E. & Newton, C. R. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and neurological outcome of cerebral malaria. Lancet Neurol. 4, 827–840 (2005).

Mishra, S. K. & Newton, C. R. Diagnosis and management of the neurological complications of falciparum malaria. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 5, 189–198 (2009).

Dondorp, A. M. et al. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial. Lancet 376, 1647–1657 (2010).

Medana, I. M. et al. Cellular stress and injury responses in the brains of adult Vietnamese patients with fatal Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 27, 421–433 (2001).

Birbeck, G. L. et al. Blantyre Malaria Project Epilepsy Study (BMPES) of neurological outcomes in retinopathy-positive paediatric cerebral malaria survivors: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 9, 1173–1181 (2010).

Boivin, M. J. et al. Cognitive impairment after cerebral malaria in children: a prospective study. Pediatrics 119, e360–e366 (2007).

Carter, J. A. et al. Persistent neurocognitive impairments associated with severe falciparum malaria in Kenyan children. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 76, 476–481 (2005).

Carter, J. A. et al. Developmental impairments following severe falciparum malaria in children. Trop. Med. Int. Health 10, 3–10 (2005).

Idro, R., Carter, J. A., Fegan, G., Neville, B. G. & Newton, C. R. Risk factors for persisting neurological and cognitive impairments following cerebral malaria. Arch. Dis. Child 91, 142–148 (2006).

Kariuki, S. M., Abubakar, A., Newton, C. R. & Kihara, M. Impairment of executive function in Kenyan children exposed to severe falciparum malaria with neurological involvement. Malar. J. 13, 365 (2014).

Oluwayemi, I. O., Brown, B. J., Oyedeji, O. A. & Oluwayemi, M. A. Neurological sequelae in survivors of cerebral malaria. Pan Afr. Med J. 15, 88 (2013).

Idro, R., Marsh, K., John, C. C. & Newton, C. R. Cerebral malaria: mechanisms of brain injury and strategies for improved neurocognitive outcome. Pediatr. Res. 68, 267–274 (2010).

Schiess, N. et al. Pathophysiology and neurologic sequelae of cerebral malaria. Malar. J. 19, 266 (2020).

Balikagala, B. et al. Evidence of Artemisinin-resistant malaria in Africa. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1163–1171 (2021).

Dicko, A. et al. Efficacy and safety of primaquine and methylene blue for prevention of Plasmodium falciparum transmission in Mali: a phase 2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 627–639 (2018).

Fall, B. et al. Ex vivo activity of Proveblue, a methylene blue, against field isolates of Plasmodium falciparum in Dakar, Senegal from 2013-2015. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 50, 155–158 (2017).

Muller, O., Lu, G., Jahn, A. & Mockenhaupt, F. P. How worthwhile is methylene blue as a treatment of malaria? Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 17, 471–473 (2019).

Zoungrana, A. et al. Safety and efficacy of methylene blue combined with artesunate or amodiaquine for uncomplicated falciparum malaria: a randomized controlled trial from Burkina Faso. PLoS One 3, e1630 (2008).

Dormoi, J., Briolant, S., Desgrouas, C. & Pradines, B. Efficacy of proveblue (methylene blue) in an experimental cerebral malaria murine model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3412–3414 (2013).

Eyles, D. E., Dunn, F. L., Warren, M. & Guinn, E. Plasmodium coatneyi from the Philippines. J. Parasitol. 49, 1038 (1963).

Eyles, D. E. et al. Plasmodium coatneyi, a new species of primate malaria from Malaya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 11, 597–604 (1962).

Aikawa, M. et al. A primate model for human cerebral malaria: Plasmodium coatneyi-infected rhesus monkeys. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 46, 391–397 (1992).

Lombardini, E. D. et al. Ultrastructural characterization of host-parasite interactions of Plasmodium coatneyi in rhesus macaques. Parasitology 149, 161–170 (2022).

Desowitz, R. S., Miller, L. H., Buchanan, R. D. & Permpanich, B. The sites of deep vascular schizogony in Plasmodium coatneyi malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 63, 198–202 (1969).

Sein, K. K. et al. Sequestration pattern of parasitized erythrocytes in cerebrum, mid-brain, and cerebellum of Plasmodium coatneyi-infected rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Am. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 49, 513–519 (1993).

Smith, C. D., Brown, A. E., Nakazawa, S., Fujioka, H. & Aikawa, M. Multi-organ erythrocyte sequestration and ligand expression in rhesus monkeys infected with Plasmodium coatneyi malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 55, 379–383 (1996).

Tegoshi, T. et al. Ultrastructure of rosette formation by Plasmodium coatneyi-infected erythrocytes of rhesus. Parasitol. Res 79, 611–613 (1993).

Udomsangpetch, R., Brown, A. E., Smith, C. D. & Webster, H. K. Rosette formation by Plasmodium coatneyi-infected red blood cells. Am. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 44, 399–401 (1991).

Kawai, S., Aikawa, M., Kano, S. & Suzuki, M. A primate model for severe human malaria with cerebral involvement: Plasmodium coatneyi-infected Macaca fuscata. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 48, 630–636 (1993).

Moreno, A. et al. Plasmodium coatneyi in rhesus macaques replicates the multisystemic dysfunction of severe malaria in humans. Infect. Immun. 81, 1889–1904 (2013).

Raja, A. I. et al. A primate model of severe malarial anaemia: a comparative pathogenesis study. Sci. Rep. 9, 18965 (2019).

Lucchi, N. W. et al. Potential serological biomarkers of cerebral malaria. Dis. Markers 31, 327–335 (2011).

Lombardini, E. D., Gettayacamin, M., Turner, G. D. & Brown, A. E. A review of Plasmodium coatneyi-macaque models of severe malaria. Vet. Pathol. 52, 998–1011 (2015).

Braunsdorf, M. et al. Does the temporal cortex make us human? A review of structural and functional diversity of the primate temporal lobe. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 131, 400–410 (2021).

Izpisua Belmonte, J. C. et al. Brains, genes, and primates. Neuron 86, 617–631 (2015).

MacLeod, C. E., Zilles, K., Schleicher, A., Rilling, J. K. & Gibson, K. R. Expansion of the neocerebellum in Hominoidea. J. Hum. Evol. 44, 401–429 (2003).

Passingham, R. How good is the macaque monkey model of the human brain? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19, 6–11 (2009).

Mantamadiotis, T. et al. Disruption of CREB function in brain leads to neurodegeneration. Nat. Genet 31, 47–54 (2002).

Riggle, B. A. et al. CD8+ T cells target cerebrovasculature in children with cerebral malaria. J. Clin. Invest 130, 1128–1138 (2020).

Barrera, V. et al. Comparison of CD8(+) T Cell accumulation in the brain during human and murine cerebral malaria. Front Immunol. 10, 1747 (2019).

Cordy, R. J. et al. Distinct amino acid and lipid perturbations characterize acute versus chronic malaria. JCI Insight 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.125156

Thiam, A. et al. Gene expression profiling in blood from cerebral malaria patients and mild malaria patients living in Senegal. BMC Med Genom. 12, 148 (2019).

Silva, N. I., Souza, P. F. L., Silva, B. F., Fonseca, S. G. & Gardinassi, L. G. Host transcriptional meta-signatures reveal diagnostic biomarkers for Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 230, e474–e485 (2024).

Bloch, K. C., Glaser, C., Gaston, D. & Venkatesan, A. State of the art: acute encephalitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, e14–e33 (2023).

Lombardini, E. D. et al. A systematic analysis of ultrastructural lesions in the Plasmodium coatneyi splenectomized rhesus macaque model of severe malaria. Vet. Pathol. 59, 873–882 (2022).

Borgers, J. S. W. et al. High-dimensional analysis of postsplenectomy peripheral immune cell changes. Immunohorizons 4, 82–92 (2020).

Bronte, V. & Pittet, M. J. The spleen in local and systemic regulation of immunity. Immunity 39, 806–818 (2013).

Seydel, K. B. et al. Brain swelling and death in children with cerebral malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 1126–1137 (2015).

Taylor, T. E. & Molyneux, M. E. The pathogenesis of pediatric cerebral malaria: eye exams, autopsies, and neuroimaging. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1342, 44–52 (2015).

Aitken, E. H., Alemu, A. & Rogerson, S. J. Neutrophils and Malaria. Front Immunol. 9, 3005 (2018).

Amulic, B., Moxon, C. A. & Cunnington, A. J. A more granular view of neutrophils in malaria. Trends Parasitol. 36, 501–503 (2020).

Feintuch, C. M. et al. Activated neutrophils are associated with pediatric cerebral malaria vasculopathy in Malawian children. mBio 7, e01300–e01315 (2016).

Lee, H. J. et al. Integrated pathogen load and dual transcriptome analysis of systemic host-pathogen interactions in severe malaria. Sci. Transl. Med. 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aar3619

Knackstedt, S. L. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps drive inflammatory pathogenesis in malaria. Sci. Immunol. 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw0336

Georgiadou, A. et al. Modelling pathogen load dynamics to elucidate mechanistic determinants of host-Plasmodium falciparum interactions. Nat. Microbiol 4, 1592–1602 (2019).

Vicanolo, T. et al. Matrix-producing neutrophils populate and shield the skin. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08741-5 (2025).

Renia, L., Grau, G. E. & Wassmer, S. C. CD8+ T cells and human cerebral malaria: a shifting episteme. J. Clin. Invest 130, 1109–1111 (2020).

Bai, M. et al. CD177 modulates human neutrophil migration through activation-mediated integrin and chemoreceptor regulation. Blood 130, 2092–2100 (2017).

Sachs, U. J. et al. The neutrophil-specific antigen CD177 is a counter-receptor for platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31). J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23603–23612 (2007).

Stroncek, D. F. Neutrophil-specific antigen HNA-2a, NB1 glycoprotein, and CD177. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 14, 688–693 (2007).

Viemann, D. et al. Myeloid-related proteins 8 and 14 induce a specific inflammatory response in human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood 105, 2955–2962 (2005).

Wang, S. et al. S100A8/A9 in inflammation. Front Immunol. 9, 1298 (2018).

Mohammed, A. O. et al. Human neutrophil lipocalin: a specific marker for neutrophil activation in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Acta Trop. 87, 279–285 (2003).

Atamna, H. et al. Mode of antimalarial effect of methylene blue and some of its analogues on Plasmodium falciparum in culture and their inhibition of P. vinckei petteri and P. yoelii nigeriensis in vivo. Biochem Pharm. 51, 693–700 (1996).

Blank, O., Davioud-Charvet, E. & Elhabiri, M. Interactions of the antimalarial drug methylene blue with methemoglobin and heme targets in Plasmodium falciparum: a physico-biochemical study. Antioxid. Redox Signal 17, 544–554 (2012).

Buchholz, K. et al. Interactions of methylene blue with human disulfide reductases and their orthologues from Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 183–191 (2008).

Farber, P. M., Arscott, L. D., Williams, C. H. Jr., Becker, K. & Schirmer, R. H. Recombinant Plasmodium falciparum glutathione reductase is inhibited by the antimalarial dye methylene blue. FEBS Lett. 422, 311–314 (1998).

Sarma, G. N. et al. Glutathione reductase of the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum: crystal structure and inhibitor development. J. Mol. Biol. 328, 893–907 (2003).

Adjalley, S. H. et al. Quantitative assessment of Plasmodium falciparum sexual development reveals potent transmission-blocking activity by methylene blue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, E1214–E1223 (2011).

Bosson-Vanga, H. et al. Differential activity of methylene blue against erythrocytic and hepatic stages of Plasmodium. Malar. J. 17, 143 (2018).

Saison, N. et al. Rapid and specific action of methylene blue against Plasmodium transmission stages. Pharmaceutics 14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14122794

Vennerstrom, J. L., Makler, M. T., Angerhofer, C. K. & Williams, J. A. Antimalarial dyes revisited: xanthenes, azines, oxazines, and thiazines. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39, 2671–2677 (1995).

Wadi, I. et al. Methylene blue induced morphological deformations in Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes: implications for transmission-blocking. Malar. J. 17, 11 (2018).

Akoachere, M. et al. In vitro assessment of methylene blue on chloroquine-sensitive and -resistant Plasmodium falciparum strains reveals synergistic action with artemisinins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 4592–4597 (2005).

Coulibaly, B. et al. Efficacy and safety of triple combination therapy with artesunate-amodiaquine-methylene blue for falciparum malaria in children: a randomized controlled trial in Burkina Faso. J. Infect. Dis. 211, 689–697 (2015).

Henrici, R. C. et al. Artemisinin partial resistance in Ugandan children with complicated malaria. JAMA 333, 83–84 (2025).

Culo, F. et al. Anti-tumoral and anti-inflammatory effects of biological stains. Agents Actions 34, 424–428 (1991).

Schirmer, R. H., Adler, H., Pickhardt, M. & Mandelkow, E. “Lest we forget you–methylene blue…”. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 2325 e2327-2316 (2011).

Prophet, E. B., M. B., Arrington, J. B., Sobin, L. H. Laboratory Methods in Histopathology(American Registry of Pathology, 1992).

McInnes, E. F. & Mann, P. Background Lesions in Laboratory Animals: A Color Atlas (Saunders Ltd., 2011).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Soneson, C., Love, M. I. & Robinson, M. D. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res 4, 1521 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2.Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Kramer, A., Green, J., Pollard, J. Jr. & Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 30, 523–530 (2014).

Khatri, P. et al. A common rejection module (CRM) for acute rejection across multiple organs identifies novel therapeutics for organ transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 210, 2205–2221 (2013).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12, 453–457 (2015).

Bordmann, G. et al. MRP 8/14 as marker for Plasmodium falciparum-induced malaria episodes in individuals in a holoendemic area. Clin. Diagn. Lab Immunol. 4, 435–439 (1997).

Schluesener, H. J., Kremsner, P. G. & Meyermann, R. Widespread expression of MRP8 and MRP14 in human cerebral malaria by microglial cells. Acta Neuropathol. 96, 575–580 (1998).

Dorovini-Zis, K. et al. The neuropathology of fatal cerebral malaria in malawian children. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 2146–2158 (2011).

Medana, I. M. et al. Axonal injury in cerebral malaria. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 655–666 (2002).

Jakobsen, P. H. et al. Increased concentrations of interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and decreased concentrations of beta-2-glycoprotein I in Gambian children with cerebral malaria. Infect. Immun. 62, 4374–4379 (1994).

John, C. C., Park, G. S., Sam-Agudu, N., Opoka, R. O. & Boivin, M. J. Elevated serum levels of IL-1ra in children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria are associated with increased severity of disease. Cytokine 41, 204–208 (2008).