Abstract

The pronounced skin tropism and pan-antifungal resistance of Candida auris pose a serious global health threat. A key question in C. auris biology is how clinical isolates acquire amphotericin B resistance. Here we demonstrate that a carbonic sensing pathway (CSP) contributes to amphotericin B resistance by modulating mitochondrial energy functions in clinical C. auris isolates. Integrated transcriptomics and proteomics identify the carbonic anhydrase Nce103 and its transcription factors Rca1 and Efg1 as important regulatory components of the CSP. The conversion of CO2 into bicarbonate sustains energy metabolism required for colonization and fitness on human skin and in nutrient-limited microenvironments. We also show that bacterial skin colonizers engage urease to release CO2 that sustains C. auris fitness and skin colonization. These findings highlight therapeutic options to re-sensitize C. auris to antifungal treatments, as well as to prevent skin colonization by blocking the CSP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Candida auris (Candidozyma auris) is an emerging human fungal pathogen causing disseminated infections of high mortality (30–72%) in individuals with underlying diseases or impaired immunity1,2,3. Since 2009, C. auris has spread to more than 50 countries, causing outbreaks in intensive care units and nursing homes4,5. Most importantly, C. auris is the first fungal pathogen showing untreatable pan-antifungal resistance traits to all clinically used antifungal entities, including azoles (up to 90%), amphotericin B (AMB, 30–60%), echinocandins (up to 8%) and flucytosine6,7,8. Hence, the high frequency of multidrug resistance (MDR)6,7 in clinical isolates poses a serious challenge to conventional therapy. Although echinocandins are first-line therapy9, their limited bioavailability in the urinary tract and central nervous system and acquired antifungal resistance traits often lead to therapeutic failure in relapsed invasive candidiasis1. In such cases, AMB has to be used as alternative treatment1,9. However, the increasing AMB resistance (AMBR) is another serious concern for C. auris infections.

It is worth noting that molecular mechanisms underlying the high rate of AMBR in C. auris remain largely enigmatic10,11. AMB causes membrane leakage through ergosterol sequestration, thereby leading to a fungicidal disruption of the electrochemical gradient. The rapid induction of oxidative stress is another potential mode of action12. Resistance to AMB is very rare in yeast species due to highly deleterious fitness costs13. Most AMBR C. auris clinical isolates do not exhibit substantially impaired fitness and, in some cases, even acquire enhanced growth12. Rare mutations in the ergosterol pathway10,14 gained during treatment promote AMBR. For instance, the ERG6YY98V* truncation confers resistance but also causes a high fitness loss14. Recently, an experimental evolution approach indicates that mutations in ERG6, ERG10, ERG11, NCP1 and HMG1 lead to acquired AMBR in C. auris10. However, the relevant mutations are exceedingly rare in clinical C. auris isolates, suggesting that elevated AMBR observed in most clinical cases may not primarily result from mutations in these genes but rather arise from synthetic genetic interaction with as yet unknown AMBR modifier genes.

In this Article, we used an advanced integrated proteo-transcriptomics approach comparing phenotypes of drug-resistant and sensitive clinical isolates to shed light on potential mechanisms contributing to elevated AMBR in C. auris. The validation and reverse genetics show a critical function of a carbon dioxide sensing pathway (CSP) in establishing both fungal fitness for skin colonization and antifungal resistance. We also demonstrate that hospital-acquired bacterial pathogens such as Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiella pneumoniae can enhance C. auris fitness by urease-mediated release of carbon dioxide that is used by the fungal CSP to sustain energy metabolism and growth.

Results

Proteomics reveals multidrug resistance mechanisms in C. auris

Transcriptomics of MDR strains versus drug-sensitive clinical isolates revealed numerous genes implicated in carboxylic acid metabolism, mitochondrial function, translation and membrane transports as critical hallmarks of antifungal resistance traits in C. auris15,16,17. However, major effectors or sensing mechanisms implicated in antifungal resistance escaped discovery15,16. Hence, we hypothesized that proteomics may identify key pathways involved in C. auris MDR traits from differentially abundant proteins (DAPs). We subjected cell-free extracts from resistant (R) (462/P/14-R1) and sensitive (S) (2431/P/16–S) C. auris strains15,17 (Fig. 1a,b) to shotgun proteomics. The data were then integrated with available RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets of strains with partially overlapping antifungal susceptibility profiles (R1, 1133/P/13R–R2 and S). As expected, several membrane transporter families were highly enriched in resistant C. auris strains (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b), including the Cdr1 multidrug efflux ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, the Mdr1 major facilitator and the putative phosphatidylinositol transfer protein Pdr16 (ref. 18), all of which cause clinical azole resistance16,19,20. In addition, the isolates R1 and R2, but not the S strain, carried the mutational hotspot S639F in the Fks1 glucan synthase (Extended Data Fig. 1c)15,21, thus explaining pronounced echinocandin resistance traits in R1 and R2. The overlay of proteo-transcriptomics datasets (Extended Data Fig. 1d–f) revealed numerous proteins, of which we chose several high-abundance factors for further validation, but at least ablation of PGA31.2, PHR1 and SMF12 did not change in minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for all four antifungal classes (Extended Data Fig. 2a).

a, Heat map showing MIC (µg ml−1) values for multidrug-resistant (R1, R2) and drug-sensitive (S) clinical strains following the CLSI method. 5FC, 5-fluorocytosine; FLC, fluconazole; VRC, voriconazole; ITC, itraconazole; KTC, ketoconazole; CAS, caspofungin. b, Proteomic workflow and data analysis. c, Heat map shows top transporters that are of high abundance in strain R1. FC, fold change. d, Volcano plot of proteomics data shows DAPs between R1 and S strains. Statistical analyses were performed using moderated two-sided t-statistics with the limma-trend method, followed by multiple test correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Differential expression analysis filters proteins with log2 fold change (log2FC) ± 0.58 and adjusted P < 0.05 indicated as dashed line. e, Gene Ontology term enrichment analysis for DAPs between R1 and S strains. The dot plot presents data from Gene Ontology enrichment analysis using clusterProfiler with P value calculated by hypergeometric distribution and Benjamini–Hochberg for multiple test correction. f, Scheme reveals a CSP controlling a link between metabolism and morphogenesis in fungal species. Panel b created with BioRender.com. Panel f adapted with permission from ref. 54, Springer Nature Limited.

NCE103 (B9J08_000363) encoding a carbonic anhydrase that converts CO2 into bicarbonate (HCO3−) was the most abundant protein in R1 relative to S (Fig. 1d). In addition, the transcription factor Rca1, a key regulator of NCE103, was also enriched in strain R1 (Fig. 1d). Gene Ontology term analysis revealed the enrichment of carboxylic acid metabolism and cell redox homeostasis in R1 (Fig. 1e), implicating a potential link between drug resistance and mitochondrial function, the main cellular location of carboxylic acid metabolism22. In other fungal species, bicarbonate plays critical roles in energy metabolism and morphogenesis, as it is acting through the cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase A (cAMP/PKA) signaling pathway that converges at the regulator Efg1 (refs. 23,24,25). Taking these together, we hypothesized that the Rca1–Nce103–Efg1 axis is vital to control antifungal susceptibility (Fig. 1f).

Rca1 and Efg1 controls AMB susceptibility across clinical isolates

Orthologues of the carbonic anhydrase basic leucine zipper (bZIP) regulator Rca1 and the helix–turn–helix / asexual–phases–specific (HTH-APSES)-type transcription factor Efg1 are only present in Candida spp. and Saccharomyces spp. genomes but not in Aspergillus fumigatus (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c). Thus, we first deleted RCA1 and EFG1 in different C. auris clinical isolates showing elevated MICs of ≥1 µg ml−1 for AMB (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Indeed, loss of RCA1 caused 2-fold and 4-fold reductions of the AMBMIC in a strain from clade III (AR384) and in different MDR strains from clade I, respectively. Deletion of EFG1 resulted in a 2-fold reduction of the MIC for AMB in both clade I and clade III strains. Surprisingly, efg1∆ and the rca1∆efg1∆ double mutant showed a 2-fold increase in MICs compared to the rca1∆ deletion (Fig. 2a). This may result from rewiring multiple downstream pathways influencing AMB tolerance or to the flocculation phenotype of efg1∆ often observed in clinical isolates (Extended Data Fig. 3b)26. Moreover, both rca1∆ and efg1∆ mutants showed slightly increased susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine, although not significant to caspofungin or voriconazole (Extended Data Fig. 3c). To further verify the role of the CSP, MIC experiments were repeated at high and low CO2 to simulate the varying CO2 levels on the skin and within deeper tissues, respectively. Remarkably, the rca1∆, efg1∆, and the sensitive strain S entirely restored AMBR in the presence of 5.5% CO2 (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3a) relative to the AMBS in ambient air (~0.04% CO2). Consequently, both Rca1 and Efg1 modulate AMB susceptibility through carbonic sensing. The simultaneous deletion of RCA1 and EFG1 showed their epistatic relationship.

a, Mutants in a CSP were subjected to MIC assays using the CLSI protocol (three biological replicates at indicated CO2 concentrations). The deletion mutants nce103∆ and rca1∆nce103∆ fail to grow in ambient air (~0.04% CO2). b, Protein levels of Rca1, Nce103 and Efg1 in strains R1 and S indicated by proteomics data (n = 3 biological replicates per group). Adjusted P values of DAPs from Limma analysis (Fig. 1d) are shown, and error bars indicate mean ± s.d. c, A synteny scheme shows conservation of carbonic anhydrase genes across fungal pathogens. d, Integrated heat map between proteomics and RNA-seq datasets reveal the upregulation of NCE103 in resistant strains. Cut-off: log2FC = ±0.58. e, CO2 enhances AMB tolerance in a subset of clinical C. auris strains (highlighted in bold pink). Spot dilution assays were performed using 5-fold serial dilutions of C. auris cells spotted onto YPD agar with or without AMB. f, Two-sided Pearson correlation between NCE103 mRNA expression (log2FC (NCE103/ACT1)) and AMB resistance among clinical C. auris isolates. AMB resistance indexes were semi-quantified using spot dilution assays on AMB plates. Two AMB concentrations (1 µg ml−1 and 2 µg ml−1) were used to capture a range of susceptibilities. Two biological replicates were performed, yielding consistent results. g, NCE103 mRNA levels in C. auris mutants under low (0.04%) and high (5.5%) CO2 conditions show that both Rca1 and Efg1 modulate NCE103 expression (n = 3 biological replicates per group). Approximately 200 c.f.u. of C. auris were plated onto YPD agar and incubated at 37 °C under either 5.5% CO2 or ambient air conditions for 2 days. Colonies were then collected for mRNA isolation. Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was applied with R1 used as control group. Each data point is shown, and error bars indicate mean ± s.d. Orthologues and gene order information were retrieved from the Candida Gene Order Browser (cgob.ucd.ie) and fungi.ensembl.org.

AMB susceptibility and CO2-sensing phenotypes were similar in strain S and rca1∆ mutants (Fig. 2a), suggesting genetic mutations in RCA1. Indeed, using IGV tool (version 2.16.2)27, we discovered a single non-synonymous nucleotide polymorphism RCA1, yielding a truncated Rca1Y110* variant lacking a the essential bZIP region. In addition, the Rca1Y110* variant was non-functional and unstable, as proteomics failed to detect any Rca1-derived peptides from strain S (Fig. 2b). Overall, the data indicated that existing loss-of-function mutation in RCA1 resensitized C. auris clinical isolates by affecting Nce103 expression.

Fungi sense CO2 by generating bicarbonate ions28,29,30 or directly through the type 2C-related protein phosphatase Ptc231, with a single orthologue B9J08_003504 in C. auris32. However, deletion of PTC2 in the R1 strain or in the rca1∆ mutant did not result in any changes of the AMBMIC, excluding a role for Ptc2 in AMB susceptibility (Fig. 2a). Therefore, Rca1 and Efg1 most likely engage carbonic anhydrase for responding to CO2-derived bicarbonate anions30, which is supported by data showing that mutants lacking RCA1 and EFG1 exhibited hypersensitivity to acetazolamide, a specific Nce103 inhibitor (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f).

The carbonic anhydrase Nce103 governs AMB susceptibility

The carbonic anhydrase gene NCE103 is conserved across many fungal species including C. auris (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 3e,f). Nce103 was highly expressed in strain R1 at both transcriptional and protein level (Fig. 2b,d). Despite multiple attempts, we failed to delete NCE103 even when supplying 5.5% CO2 for selection. However, the CRISPR–Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and CRISPR-associated protein 9) method33 allowed for constructing the nce103Δ deletion when supplementing with 10% CO2. As Nce103 appeared as an essential protein for fitness in ambient air, its lack caused severe fitness defects, but growth gradually resumed upon CO2 supplementation (Fig. 2a). The nce103∆ mutant exhibited the same AMBMIC values as the rca1∆ strain in 1.5% CO2. The rca1∆nce103∆ double mutant did not show exacerbated susceptibility, while supplementing with 5.5% CO2 fully restored AMBR in all strains (Fig. 2a). Therefore, Rca1 and Nce103 are epistatic and act in the same CSP.

Supplementing with 5.5% CO2 enhanced AMBR in several strains (Fig. 2e). Therefore, we reasoned that messenger RNA expression or gene dosage of NCE103 might affect AMBR traits. Indeed, a subset of clade I AMB-resistant strains exhibited high NCE103 expression (Fig. 2f), and the correlation between NCE103 mRNA levels and AMBR was modest but statistically significant (Pearson’s R2 = 0.19, P = 0.045). Similarly, ectopically overexpressing NCE103 (eNCE103) in multiple backgrounds fully restored AMBMIC to R1’s MIC, although mRNA levels of eNCE103 were higher than in the R1 strain (Extended Data Fig. 3g).

The RNA-seq data hinted a strong 6-fold and 9-fold NCE103 downregulation in rca1∆ and efg1∆ mutants, respectively (Fig. 2d). To answer how RCA1 and EFG1 regulate NCE103, we examined NCE103 mRNA levels in C. auris cultured under low and high CO2 conditions. Supplementing with 5.5% CO2 resulted in a modest reduction in NCE103 expression in the R1 strain (Fig. 2g). By contrast, deletion of RCA1 and/or EFG1 markedly repressed NCE103, showing a 4- to 9-fold decrease under both CO2 conditions. The proteomics data showed that Nce103 abundance under AMB stress was higher in strain S but failed to reach the levels in R1 (Extended Data Fig. 1f). These findings strongly support the notion that Rca1 and Efg1 regulate AMB susceptibility engaging the Nce103 carbonic anhydrase.

Deletion of NCE103 has marginal effects on lipidomes

The interference with ergosterol function is a primary mode of action for AMB. Hence, we analysed sterol lipid composition in mutants associated with the Rca1–Nce103–Efg1 axis (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). Overall, AMB treatment altered relative ergosterol proportions, including sterol precursors, compared to the untreated group. Although lanosterol proportions increased by AMB exposure, differences in sterol composition between R and S strains were insignificant, consistent with a recent report12. The slight increase in relative lanosterol levels following AMB treatment was insignificant compared to sensitive strains (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Thus, alterations in membrane sterol composition are not the primary cause of CSP-mediated AMB susceptibility.

Growing evidence suggests that inositol phosphorylceramides (IPC) contribute to AMB tolerance34. Therefore, we performed global lipidomics of the nce103∆ mutant and the reconstituted nce103∆NCE103 control, but we failed to see differences in lipid species between the reconstituted and mutant strains (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Likewise, sphingolipids such as IPC (Extended Data Fig. 4d) were unchanged. The fungal-specific IPC synthase inhibitor aureobasidin A (AbA) enhances the efficacy of AMB against Cryptococcus neoformans34. AbA similarly enhanced AMB activity in C. auris, but it showed no significant differences between WT and CSP mutants (Extended Data Fig. 4e). PCA analysis revealed that the nce103∆ samples were more dispersed with a slight separation from the WT strain following AMB treatment (Extended Data Fig. 4f), suggesting that dynamic lipid changes may still contribute to AMB susceptibility12,18.

The CSP may influence AMBR by supporting metabolism and mitochondrial functions

To further investigate the impact of CSP on AMB susceptibility, we conducted semiquantitative spotting assays on R and S strains using various stress inhibitors (Fig. 3a). Remarkably, deletion of RCA1, EFG1 and NCE103 resensitized the R1 strain to cell membrane and osmotic stressors, including sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sodium chloride (NaCl), oxidative stress from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and the mitochondrial complex III block through antimycin A (AA). By contrast, overexpression of NCE103 in the S strain reduced susceptibility to NaCl, H2O2, AA, the mutagen methyl methane sulfonate (MMS) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor rapamycin (Fig. 3a). The most striking effect was observed with AA (Extended Data Fig. 5a), correlating with the enhanced carboxylic acid metabolism upon RCA1 or EFG1 deletion (Fig. 3c).

a, Semiquantitative spotting assays with different stress agents. Serial 5-fold dilutions of fungal cell suspensions were spotted onto YPD agar containing chemical agents as indicated. Semiquantitative data were collected by comparing relative growth properties of tested strains. b, Potential mechanisms implicated in CSP-mediated AMB resistance deduced from data shown in a. c, Gene Ontology enrichment for differentially expressed genes in rca1∆ and efg1∆ mutants compared to WT. Data were filtered with cut-off log2FC of ±0.58. Common Gene Ontology terms of rca1∆ and efg1∆ were visualized. d, Spotting assays for CSP mutants on media containing 3 µg ml−1 AMB and 5 mM VitC. e, MIC assays for AMB alone and in combination with the mitochondrial inhibitor AA. The AA concentration ranged from 0 to 1 µg ml−1 (top to bottom) for each strain. Three biological replicates yielded similar results in a, d and e. Credit: icons in b, Bioicons.com under a Creative Commons license CC BY 3.0.

Impaired mitochondrial functions can also promote accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)12, thus explaining the increased H2O2 susceptibility of rca1∆ and efg1∆ deletion mutants. Increased intracellular ROS can also exacerbate membrane lipid and DNA damage12, which was strongly supported by the apparent hypersensitivity to SDS and MMS, respectively (Fig. 3a,b). Consequently, disruption of the CSP causes AMB hypersensitivity through mechanisms linked to mitochondrial function and ROS response. If this effect was primarily related to ROS, we hypothesized that antioxidants could reverse the AMBR phenotype. To test this, we performed serial dilution spotting assays using rca1∆, efg1∆ and nce103∆ mutants on media with or without AMB, vitamin C (VitC) or their combination (Fig. 3d). The supplementation with VitC enhanced AMB tolerance in all null mutants, as well as in the sensitive WT strain AR387 harbouring a fully functional CSP. Therefore, fluctuations in ROS levels can influence AMBR traits in C. auris. However, there were no significant changes of AMBMIC in mutants, although AR387 showed a 2-fold increase when supplementing with 250–1,000 µM VitC (Extended Data Fig. 6). Hence, ROS accumulation alone cannot fully explain AMB sensitivity resulting from a disabled CSP.

Because all deletion mutants in CSP were hypersusceptible to AA (Extended Data Fig. 5a), we hypothesized that supplementation with AA in the MIC assay should further reduce AMBMIC from 2- to 4-fold as observed in null mutant strains. If mitochondrial function operates downstream of the CSP, AA should cause less reduction to the AMBMIC in CSP null mutants than the WT. Hence, we subjected rca1∆, efg1∆ mutants and eNCE103 overexpression strains to checkerboard assays with AA and AMB. As expected, AA caused a 2-fold reduction of AMBMIC in WT strains from five clades and in eNCE103 overexpression strains, but not in null mutants (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5c). Therefore, CSP may promote AMBR by engaging mitochondrial functions.

Targeting mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 enhances AMB efficacy

Lansoprazole can synergize with AMB by inhibiting cytochrome bc1 in C. auris35, which is consistent with our data for AR387 and R1, yielding fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) values of 0.625 and 0.75, respectively. Given that CSP disruption may be linked to mitochondrial dysfunction via the AA target cytochrome bc1, we attempted to delete RIP1, the catalytic subunit of this complex. While we were unable to ablate RIP1 in R1 or its isogenic CSP mutants, we successfully obtained rip1∆ deletion mutants in the AR387 (B8441) background. The rip1∆ mutants had an approximately 2-fold reduction in AMBMIC (Fig. 4a,b). Owing to the AA toxicity for humans, we used the fungal-selective cytochrome bc1 inhibitor methyltetrazole analogue Inz-536 to assess its potential in enhancing AMB efficacy. Indeed, Inz-5 reduced AMBMIC in several Candida species as well as in C. neoformans. Checkerboard assays suggested that effects of combinatorial treatments ranged from indifferent to synergistic based on the calculated FICI values (Fig. 4c). Therefore, the Rip1 mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 component could be a promising target for potentiating AMB efficacy.

a, Deletion of RIP1 encoding the active subunit of the cytochrome bc1 complex increases AMB susceptibility. MIC assays were performed for C. auris in RPMI, YPD and YP–2% glycerol (YPG). b, The cytochrome bc1 inhibitor Inz-5 partially phenocopies the sensitivity of the rip1∆ mutant in a serial dilution spotting assay, in both the presence and absence of AMB. c, Inz-5 reduces the AMBMIC by about 2- to 4-fold across multiple fungal pathogens in checkerboard assays. Two to three biological replicates were performed in a–c.

The CSP is required for fungal fitness and colonization of nutrient-limited skin niches

The CSP influences not only AMBR but also fungal fitness. In minimal medium (MM), both mutants and the WT S strain showed severe growth defects, even when supplementing with 5.5% CO2 (Fig. 5a). Overexpression of NCE103 in strain S strongly promoted fungal growth in MM and yeast–peptone (YP). Glucose as a carbon source enabled all mutants to reach the stationary growth phase with maximal optical density at 600 nm (OD600nm) similar to the WT strain. Hence, glycolytic energy metabolism is linked to the Rca1–Nce103–Efg1 axis. Indeed, efg1∆ exhibited a severe fitness defect that was not fully rescued by supplementing with 5.5% CO2 in YP medium. Impacting energy metabolism may trigger compensatory mechanisms, as reflected by the upregulation of carbohydrate transport in both rca1∆ and efg1∆ mutants (Extended Data Fig. 7a).

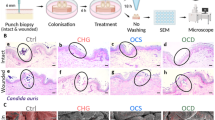

a, Growth curves were recorded at OD600nm for 72 h in MM, YP and YPD medium. b, Nce103 protein levels under different conditions. The NCE103 locus in the R1 strain was tagged with dTomato; fluorescence signals were quantified by flow cytometry. c, Growth properties of C. auris from five clades are promoted by low and high CO2 on MM. Tenfold serial dilutions of C. auris cell suspensions were spotted on MM agar and incubated at 37 °C for 5 days. d, Competitive fitness assays of mutants and the WT strain (R1) following intradermal infections after 3 days (n = 6 or 8 per group). The competitive index was determined using qPCR assays for gDNA isolated from a mixture of C. auris strains (left). For nce103∆ mutants, fitness was assessed by counting of colony-forming units after culturing in ambient air (control nce103∆ does not grow) and in 5.5% CO2. e, Fungal burden in murine biopsies after colonizing intact back skin for 14 days (n = 6 for R1, rca1∆ and efg1∆; n = 10 or 11 for other groups). f, Determination of the fungal burden in skin biopsies after 2 days of colonization on back skin (n = 5 or 6 per group). g, Fungal burden on human skin (9 biopsies from 3 human donors). Fungal suspensions of the WT strain (R1) and the mutants were applied on human skin biopsies. After 24 h, biopsies were washed in PBS, and combined colony-forming units were quantified from washing supernatants and skin tissues, with the total representing the sum of colony-forming units in both fractions. Statistical analyses were performed on average colony-forming units data from each donor. h,i, Representative images of SEM (h) and periodic acid–Schiff staining (i) of human skin topically infected with C. auris for 24 h. Scale bar, 10 µm in h and 100 µm in i. P values were obtained by two-tailed paired t-test in d, one-way ANOVA in e, two-way ANOVA in f, and one- or two-way ANOVA for wash/tissue or total colony-forming units, respectively, in g, followed by Bonferroni or Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. Box plots indicate the median and interquartile range, with whiskers representing minimum and maximum values using data pooled from at least two independent experiments in d–g. Each data point and exact P < 0.05 are shown in d–g. Panel g (right) created with BioRender.com. Credit: icons in d–g, Bioicons.com under a Creative Commons license CC BY 3.0. Panel g (left) adapted with permission from ref. 53, Springer Nature Limited.

Although rca1∆ regrew at later time points in YP–glucose (YPD) medium, growth was delayed during the first 8 h compared to R1 (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Thus, CSP is particularly important during early culture stages at low cell densities, when metabolism-derived CO2 is insufficient to support growth37. Indeed, initiating growth at low cell densities in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) medium resulted in a marked growth delay of rca1∆ and efg1∆ deletions (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Next, we epitope-tagged native NCE103 in the R1 strain with dTomato to quantify Nce103 levels in the growth phases. Nce103 was actively expressed during early stages of culture but downregulated during late exponential growth or when 5.5% CO2 was used as supplement (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that NCE103 is also critical for supporting initial growth when metabolism-derived CO2 is limited.

Maintaining fitness is pivotal for host skin colonization as well as for the dissemination of C. auris in hospital settings. To assess whether CSP can impact fitness and growth of C. auris from different clades, we tested clinical isolates in minimal media (Fig. 5c). In fact, CO2 supplementation enhanced growth of C. auris strains from five clades in nutrient-limiting conditions. Hence, the CSP may play key roles in maintaining fungal fitness when growing in or colonizing nutrient-limited environments.

C. auris requires the CSP for growth on human skin

C. auris is a skin-tropic colonizer, and its ability to persist and penetrate from the skin’s surface into deeper compartments is crucial for causing systemic infections38. Thus, we infected C57BL/6 mice with the WT (R1) strain and rca1∆, efg1∆ and nce103∆ mutants by intradermal injection. Competitive quantitative fitness assays revealed that the R1 strain exhibited pronounced increased fitness compared to the efg1∆ mutant, but there were no remarkable differences between R1 and the rca1∆ or nce103∆ mutants (Fig. 5d). Therefore, the CSP does not contribute to fitness when C. auris reaches deeper skin compartments as by intradermal infection.

Although the nce103∆ mutant failed to grow in ambient air (Extended Data Fig. 7c), it can still establish long-term colonization on intact mouse skin (Fig. 5e). However, nce103∆ is unable to efficiently colonize mouse in vivo and human skin ex vivo after 48 and 24 h, respectively, showing 10- to 100-fold lower burden compared to the WT strain (Fig. 5f,g). This confirmed the critical role of Nce103 for initial colonization of native skin tissues. After growing for 14 days on mouse skin, C. auris was mainly seen around or within hair follicle shafts39, where higher CO2 levels emerging from epithelial metabolism and bacterial skin microbiome components may further support fungal growth40. By contrast, rca1∆ and efg1∆ mutants exhibited a striking 10- to 100-fold decrease in colonization of both mouse and human skin compared to the WT control (Fig. 5e–g). Therefore, the CSP is crucial for the initial colonization of native human and mouse skin (Fig. 5h,i). Moreover, Efg1 is required for fitness, virulence and long-term persistence on mouse skin, as well as for subsequent infection, although independently of Nce103.

CO2 derived from bacterial metabolism can promote C. auris growth

As there were no significant differences observed in long-term persistence on mouse skin between the nce103∆ mutant and the WT, it suggests that CO2 produced in hair follicles may contribute to the mutant’s fitness. In addition, CO2 could also be generated through microbiota metabolism. Specifically, P. mirabilis and K. pneumoniae are highly enriched bacteria in C. auris-positive skin samples41. Both bacteria are positive for urease, an enzyme that catalyses the breakdown of urea in the microenvironment into ammonia and CO2 (Fig. 6a)42. Based on this, we hypothesized that bacterial urease activity supplies the fungal CSP, thereby supporting C. auris fitness on the skin microenvironment. Consistently, P. mirabilis and K. pneumoniae significantly enhanced the growth of CSP mutants in vitro (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 7d). However, this growth-promoting effect was lost when using urease-negative mutant ureC43 of P. mirabilis, similar to results observed with urease-negative Staphylococcus aureus or the no-bacteria control. These findings strongly indicate that urease-positive bacteria that co-colonize on skin facilitate C. auris growth by releasing CO2, the key substrate for the CSP.

a, A schematic illustration depicts how urease-positive bacteria supply CO2 to the CSP of C. auris. b, Hospital-acquired bacteria can promote growth of C. auris by releasing CO2 through the urease pathway. Experiments were performed on 12-well plates, where bacterial cell suspensions were spotted in the two middle columns and fungal cell suspensions in both outer columns. Each fungal strain was tested at three levels of 10-fold dilutions. The plates were covered, sealed in plastic bags and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Representative data from at least three independent experiments.

Discussion

One of the open unsolved questions in C. auris pathophysiology is why and how up to 60% of clinical isolates6,7 can acquire high AMBMIC values. Although previous efforts focused on genetic variations10,14, they cannot explain this phenomenon in the majority of AMBR isolates, especially as AMBR has been rarely seen in other Candida pathogens. Here, we took advantage of integrated proteomics and transcriptomics data from clinical strains to uncover a CSP that plays a crucial role in AMBR as well as pathogen fitness and skin colonization. We show that the CSP engages the Nce103 carbonic anhydrase under the control of the transcription factors Rca1 and Efg1. We demonstrate that the Rca1–Nce103–Efg1 axis not only controls AMB susceptibility but is also essential for fungal fitness and skin colonization. Although 2- to 4-fold reduction in AMBMIC seems a moderate effect, it is highly relevant for therapeutic outcomes44,45,46. We noticed that the CSP provides an intrinsic mechanism establishing a tolerogenic background to AMB in C. auris. However, higher concentration of CO2 in deeper skin tissue helps C. auris bypass the need for a CSP and may thus regain AMBR.

The downstream functions of the CSP link to mitochondrial functions, which in turn could regulate both fitness and AMB susceptibility. Indeed, acquired AMBR in clade II strains appearing after microevolution in vitro is associated with upregulation of the alternative oxidase Aox2. Deletion of AOX2 in AMBR-adapted strains reduced the MIC but had no significant effect on parental strains, implying that AOX2 may contribute to controlling AMB susceptibility by involving interactions with other as yet unknown genetic factors12. However, our data suggest that the lack of AOX2 in R1, rca1∆ or efg1∆ backgrounds does not change the AMBMIC (Extended Data Fig. 5b), although aox2∆ mutants show severe sensitivity to AA. Similarly, deletion of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase homologue SOD2 yielded MIC comparable to aox2∆ mutants. These findings suggest that the ROS response may have a minor role in AMBR in C. auris. Alternatively, the effects may result from a combination of ROS12, mitochondria-dependent stress response and other mechanisms. Indeed, targeting mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 by ablating RIP1 or by the lead compound Inz-5 enhances AMB efficacy across in species, identifying Rip1 as an antifungal target.

Although the precise mode of AMB action remains ill-posed even almost 70 years after approval, the consensus suggests the membrane lipid bilayer function as the primary AMB target. AMB binds or sequesters ergosterol-related lipids to exert its fungicidal activity46,47. Surprisingly though, our data reveal no significant differences in ergosterol levels or IPC-related lipids. Thus, we speculate that AMB–lipid interactions may cause dynamic changes in the relative lateral or transversal architecture of ergosterol and phospholipids in the plasma membrane without affecting overall lipid levels. For instance, ‘sterol-sponges’ may cause membrane instability and the breakdown of the electrochemical gradient47. Further, we hypothesize that the dynamic mosaic organization of lipid bilayers may be subject to control by CSP and/or mitochondrial function. Our lipidomic analysis supports this notion, as substantial fluctuations of lipid landscapes across biological replicates are evident in nce103Δ (Extended Data Fig. 4f). In addition, lack of RCA1 or EFG1 dysregulates multiple membrane transporters, many of which have been implicated in multidrug resistance phenomena (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). Fluorescein diacetate-based assays suggest increased membrane fluidity, confirming protein-independent changes in bilayer permeability17. Although we observe increased fluorescein diacetate uptake in some experiments (Extended Data Fig. 8c), these results are variable across independent replicates similar to what we observe for lipidomics data in nce103∆. Nonetheless, these observations strongly confirm a potential mechanistic link between AMBR and the dynamic membrane lipid homeostasis.

A model for fungal CSP wiring (Fig. 1f) suggests that Nce103 ultimately shunts HCO3− into mitochondrial energy metabolism to support fatty acid and amino acid biosynthesis. Furthermore, it regulates mitochondrial functions through the cAMP–PKA–Efg1 signalling24,48,49. Deletion of CYR1, RAS1 and CDC25 in strain AR387 increases AMB tolerance23,25 (Extended Data Fig. 3h), implying negative feedback regulation by downstream components within the CSP or a complex interplay with as yet unknown additional wiring in C. auris. Regarding C. auris fitness in the in vivo intradermal model and long-term colonization in vivo, Efg1 may involve additional independent mechanisms on top of the carbonic anhydrase Nce103. By sharp contrast, lack of RCA1 or EFG1 or NCE103 does not cause significant differences in fungal burden recovered from various organs after systemic infections, even when mice were treated with AMB (Extended Data Fig. 7e,f). Moreover, differences in MIC changes between rca1∆, efg1∆ and rca1∆efg1∆ mutants imply overlapping as well as independent mechanisms Rca1 and Efg1 engaging to regulate AMB susceptibility. This is a plausible scenario, as deletion of RCA1 or EFG1 dysregulates 35–50% of the putative transcription factors in the C. auris genome (Extended Data Fig. 7g), indicating additional roles. Although a CSP is well documented in other fungal species24,28,29,48,50, its unique role in promoting AMBR has not been demonstrated. For instance, deletion of Candida albicans RCA1 slightly increases susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine while enhancing resistance to echinocandins and azoles48. Similarly, overexpression of the carbonic anhydrase Can2 in C. neoformans leads to hypersensitivity to polyenes and azoles51.

The CSP plays a crucial role in fungal colonization and growth on skin niches, which is consistent with reports for other Candida species29. It is worth noting that the Rca1–Nce103–Efg1 axis enables C. auris growth in nutrient-limited environments such as human skin or abiotic surfaces of healthcare devices or medical equipment. Indeed, C. auris and related species can grow on solid MM medium, particularly under elevated CO2 levels (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 8d). This implies potential risks associated with carboxytherapy such as topical CO2-releasing gels or subcutaneous applications52 used in wound management. Although C. auris appears unable to breach intact epithelial barriers as present on skin, the pathogen is able to reach deeper skin compartments through microwounds, damaged skin or via hair follicle invaginations38,39.

In hair follicles, metabolism-derived CO2 levels from human cells or bacterial microbiota components may compensate for impaired CSP activity. For instance, the bacterial urease pathways may synergize with the CSP in controlling fungal fitness on skin tissues. We show that bacteria-derived CO2 can support C. auris growth in vitro. In clinical swab samples from skin, C. auris is often enriched with nosocomial transmission-associated urease-positive bacteria such as P. mirabilis42 and K. pneumoniae41. Nonetheless, it is critical to emphasize that Nce103 is essential for facilitating initial skin colonization, preceding (passive) skin penetration and subsequent systemic infections once reaching the vasculature (Extended Data Fig. 9)53,54. Our findings strongly support the notion about a possible skin microbiome contribution to facilitate or sustain fungal colonization41, as bacteria can promote C. auris growth through their urease-mediated CO2 release. This enzyme degrades urea, which is naturally present in sweat and commonly used in skincare products. While eccrine sweat glands are widely distributed in human skin, they are rare in fur-covered mammals such as mice55. Therefore, there is a need to establish suitable animal models and ex vivo human skin systems to investigate interkingdom interactions on the skin surface56.

Taking these together, we answer a major question in C. auris biology related to AMBR and fungal virulence. We identify a CSP under the control of a dedicated bZIP transcription factor Rca1, which regulates the carbonic anhydrase Nce103 effector enzyme. Interestingly, Efg1 may be serving as both regulator of and downstream effector for the CSP. We further demonstrate that abrogation of the CSP may impair mitochondrial function, which debilitates fitness and AMBR traits. Therefore, the C. auris CSP enables growth on human skin and potentially exploits carbon dioxide that is released in the skin microenvironment by microbiome components (Extended Data Fig. 9). Finally, our data suggest that targeting microbiome-derived CO2 production via bacterial urease inhibition may offer a strategy to limit C. auris skin colonization.

Methods

Ethics statement

Animal experiments adhered to ethical approval from the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna and the Federal Ministry of Science and Research, Vienna, Austria (BMBWF-66.009/0436-V/3b/2019). Adult wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Mus musculus) were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions, with controlled temperature (20–22 °C) and humidity (45–65%), in a 12 h light/dark cycle at the animal facility of the Max Perutz Labs Vienna. Mice breeding and maintenance was in accordance with ethical animal license protocols complying with the applicable Austrian law. Abdominal human skin samples were obtained from anonymous healthy adult female donors with approved consent following the Declaration of Helsinki and ethics committee approvals of the Medical University of Vienna (ECS 1969/2021). Donors were included based on availability, without random selection or specific covariate criteria such as age, sex or medical history. Given the small number and the use of samples solely for ex vivo colonization assays, potential selection bias is not expected to impact the study outcomes.

Fungal growth conditions, media formulations and dose–response assays

A list of fungal strains used in this study is provided in Supplementary Table 2. C. auris was routinely grown in YPD medium at 30 °C, with shaking at 200 r.p.m. For growth curve experiments, we used MM or YP with different carbon sources. All medium compositions are provided in Supplementary Table 3. All chemical reagent vendors and identifiers are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Growth curves were derived for different culture media formulations as described in Supplementary Table 3. Fungal cells from an overnight culture in YPD at 30 °C, with shaking at 200 r.p.m., were washed 3 times with distilled water (dH2O), followed by measurement of the OD600nm. Cell suspensions were adjusted to 0.2 OD600nm in dH2O. Aliquots of 100 µl of testing media (two times concentration) were dispensed into non-treated 96-well plates (Starlab). Subsequently, 100 µl of fungal suspensions was added to each well. Plates were incubated in static incubators at 37 °C with/without 5.5% CO2. The OD600nm was recorded every 2 h within 72 h by Victor Nivo plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Dose–response assays were done adhering to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standard M27-A3 (ref. 57) protocol in 96-well plates. Briefly, yeast cells from YPD agar plates 3–5 days old were inoculated overnight in liquid YPD medium. Fungal cultures were adjusted to OD600nm of 0.1 in distilled water. A 25 µl aliquot of fungal suspensions was diluted into 10 ml RPMI 1640 (Gibco) buffered with 35 g l−1 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (AppliChem), pH 7 (referred as RPMI). The 96-well plates containing 100 µl media with drug compounds were prepared by 2-fold serial dilutions. Then 100 µl of the fungal suspensions was aliquoted into each well. Negative controls lacked inoculum, whereas positive controls included inoculum without adding agents. Plates were incubated 24 h at proper conditions following experimental requirements. Optical density at OD600nm was recorded in Victor Nivo Microplate Reader. MIC was defined as the well showing at least 50% growth inhibition compared to the no-drug control for all drugs, except for AMB, where a 90% growth inhibition threshold was used. Checkerboard assays were performed similar to dose–response assays, using 2-fold serial dilutions of AMB on the y axis and AA, Inz-5 or AbA on the x axis. FICI values were calculated as reported before58.

Semiquantitative agar assays

Fungal cells were grown until the exponential growth phase in YPD liquid medium. Cells were counted by a CASY cell counter then adjusted to 2 × 107 cells per ml in PBS. A 5-fold serial dilution of fungal suspension was performed in a 96-well plate. Then 3 µl of each dilution was spotted onto YPD agar without/with stress agents targeting metabolism (8 µg ml−1 voriconazole, cerulenin, 0.5 µg ml−1 rapamycin), genotoxic stress (150 mM hydroxyurea, 0.06% MMS), cell wall (4 µg ml−1 caspofungin, 30 µg ml−1 calcofluor white, 0.02% Congo red, 64 µg ml−1 nikkomycin Z), cell membrane (1 M potassium chloride, 1 M NaCl, 0.1% SDS), mitochondrial functions and ROS inducers (15 mM H2O2, 5 µg ml−1 AA, 8 µg ml−1 Inz-5, 0.5–3 µg ml−1 AMB). Plates were incubated at designated conditions. Pictures were taken after 2 days. Semi-quantitative phenotypic traits were collected by comparing the growth fitness of different strains under specific stress conditions59,60.

Proteomics

Several colonies of C. auris growing on YPD agar were picked and re-grown overnight in RPMI. Fungal suspensions were transferred to 50 ml fresh RPMI to reach OD600nm of 0.1 in baffled flasks. After 5 h incubation at 30 °C with agitation of 200 r.p.m., AMB was added at a final concentration of 0.5 or 0 µg ml−1 for an additional 2 h. Yeast cells were pelleted and washed 3 times in cold PBS (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were resuspended in tubes containing 300 mg of glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 ml of Candida lysis buffer (1% sodium deoxycholate, 100 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM EDTA, 1 tablet per 50 ml complete protease inhibitor), followed by bead beating (FastPrep-MPI) (6 m s−1 for 45 s, done 3 times). The supernatant was collected by centrifuging through the small hole created at the bottom of the tube with a G26 needle tip. Protein was precipitated by 4 volume acetones, at −20 °C, overnight. Three biological replicates were performed for each experimental group. Protein pellets were subjected to proteomic analysis using a standard workflow (see details in Supplementary Information).

RNA isolation, quantitative PCR and RNA-seq

Fungal cultures were centrifuged, and cell pellets were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Dry cell pellets were then stored at −80 °C for later use. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIZOL method, followed by DNase I treatment using the same protocol described previously8,61 (see details in Supplementary Information).

RNA quality and purification was checked with Nanodrop and conventional PCR-based quantification of ACT1 mRNA. For quantitative PCR (qPCR), first-strand complementary DNA was synthesized from RNA with Reverse Transcription System Kit (Promega). Subsequently, 15 ng cDNA was utilized for qPCR amplification, using the 2x Luna Universal master mix (NEB). For competitive assays, genomic DNA was used directly for qPCR. The data were analysed using the cloud-based system provided by Bio-Rad accessible at BR.io.

For RNA-seq analysis, fungal cells grown overnight were diluted into 15 ml fresh YPD to reach OD600nm of 0.1 in baffled flasks. Flasks were then incubated at 37 °C until they attained OD600nm of 2.5. Fungal cells were collected by centrifugation, and RNA was isolated using TRIZOL method. At least three biological replicates were subjected to RNA-seq. The library and sequencing were performed at the commercial Novogene Sequencing Facility (UK). Briefly, mRNA was enriched by poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads followed by double-stranded cDNA library preparation. The quality-controlled RNA libraries were pooled and sequenced with 150 bp paired-end reads on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

RNA-seq bioinformatics data analysis used a workflow established previously15. Differential expression analysis was conducted using EdgeR v3.40.262. The false discovery rate was controlled by adjusting P values using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction. Gene Ontology term enrichment analysis (enrichGO) and gene set enrichment analysis were performed with clusterProfiler (version 4.0)63 using annotation data retrieved from fungiDB (www.fungidb.org).

Generation of C. auris mutants

C. auris deletion mutants were generated by gene replacement as described before using a gene-specific deletion cassette with a dominant marker constructed using the three-way stitching PCR method64. Briefly, approximately 500 bp upstream and downstream flanking regions of the target gene were amplified from gDNA of C. auris strains. The NAT1 or NeoR selection marker flanked by the TEP promoter and terminator was amplified from plasmid pTS5064 or pTO14933. DNA fragments were purified by GeneJET gel extraction kit (ThermoScientific), followed by a stitching PCR to obtain gene deletion cassettes for genomic targeting.

NCE103 null mutants were constructed using a CRISPR–Cas9 system kindly provided by the O’Meara lab33. The Cas9 amplicon was amplified from plasmid pTO13533. The DNA-repairing cassette was generated by fusion PCR to replace the NCE103 coding region by NeoR marker amplified from plasmid pTO14933. A DNA cassette containing guide RNA (gRNA)–trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) was designed with Benchling65. A mixture of three DNA amplicons were transformed into C. auris using the routine electroporation protocol64,66.

For overexpression of NCE103, we placed the NCE103 locus under the control of the ENO1 promoter from C. auris. The cassette containing urNEUT1-pENO1-NCE103-pTEP1-NAT1(or NeoR)-drNEUT1 was cloned into a long intergenic region (NEUT1) located between B9J08_000423 and B9J08_000424 on chromosome 1. For the conditional deletion of NCE103 and CYR1 in AR387, a plasmid pCB323 containing the tet-Off system67, assembled with the NAT1 marker optimized for C. auris, was used. The tet-Off system was flanked by approximately 500 bp of the left and right regions and directed into NCE103 locus assembled in plasmid pCT06. The native promoter of NCE103 was replaced with this tet-Off system, allowing for regulated gene expression under tetracycline supplementation.

For C-terminal NCE103-dTomato epitope tagging, plasmid pCT02 was constructed using 500 bp upstream and downstream flanking sequences of the native NCE103 locus. The dTomato gene was inserted at the C-terminus immediately before the stop codon of the NCE103 gene, followed by a NeoR selectable marker. All plasmids were assembled using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (NEB - M5520) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

PCR-amplified DNA cassettes were transformed into C. auris using the electroporation protocol as described before64,66. Several independent transformants were cultivated for 4 h in YPD/sorbitol (1:1) before being plated onto YPD agar containing 200 μg ml−1 nourseothricin or 1,200 μg ml−1 G418 plus 1,000 mg ml−1 molybdate68 and incubated at 30 °C for 3–4 days. Colony PCR with OneTaq 2X master mix (NEB - M0482) was used to control for loss of gene as well as correct genomic integration64. For nce103∆, outgrowth and antibiotic selection plates were incubated in 10% CO2. The outgrowth medium (YPD/sorbitol, 1:1) was degassed and preincubated overnight in 10% CO2 before use. All oligonucleotide primers and plasmids are listed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Lipidomic analysis

Fungal cells from exponential growth phase were cultured in 15 ml RPMI from OD600nm = 0.3 at 37 °C with shaking at 200 r.p.m. After 5 or 16 h, cells were treated with 1 µg ml−1 AMB for an additional 2 h. After treatment, cells were washed three times with sterile dH2O and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent analyses. Sterol lipids were extracted using a previously reported protocol and quantified by gas chromatography coupled to an Agilent 5977B quadrupole mass spectrometer (MS), with cholestane (Merck, C8003) as the internal standard69,70. Lipid extraction was performed using a routine chloroform-based extraction protocol71 and further analysed by liquid chromatography coupled with MS/MS. Data sets from shotgun and targeted analysis were combined to calculate molar percentages (mol%) of individual lipid species72,73,74 (see details in Supplementary Information).

Mice infection and colonization assays

WT C57BL/6 mice, aged 8 to 14 weeks at the start of experiments, were used. Female mice were used for skin experiments, while both sexes were used for systemic infections via the tail vein.

For intradermal infections, an equal cellular mixture of 5 × 106 WT and mutant cells in 15 µl PBS was injected into the shaved back skin after anaesthesia with ketamine–xylazine (100 mg ketamine per kg body weight and 4 mg xylazine per kg body weight). On day 3 after infection, mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation, and 8 mm skin biopsies from infected sites were collected. Skin biopsies were homogenized as described above, followed by plating on YPD agar containing ampicillin, tetracycline and chloramphenicol (YPD-CAT). Plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5.5% CO2 for 48 h. Fungal cells were collected from plates for gDNA extraction and qPCR to identify the ratio of mutants and WT in each sample using the primers for RCA1, EFG1 and NAT1. Fungal mixtures used for infection were plated to control the actual infection dose. Relative gDNA abundance of WT (primers for RCA1 or EFG1) and mutants (primers for NAT1) were calculated based on ACT1 as a control gene. The relative gDNA abundance was adjusted with abundance ratio of input samples before calculating competitive values as log2 (relative abundance values to WT).

For systemic infections, WT mice (21.5 g) were injected via the lateral tail vein with 2 × 106 fungal cells in 100 µl PBS75. On day 5 after infection, mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation, and colony-forming units (c.f.u.) in the spleen, kidney, liver and brain were quantified by plating. For AMB treatments, amphotericin B deoxycholate (Fungizone, Gibco) was administered by intraperitoneal injection of 5 mg per kg body weight on days 1 and 2 after infection.

For skin colonization assays, mice were anaesthetized with ketamine–xylazine followed by hair removal from back skin using an electric shaver to clear an area ~9 cm2. Four applications were conducted on the same area using suspensions containing 2 × 108 fungal cells (WT and mutant strains) in 100 µl PBS, applied every 2 days. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation on day 14, and fungal cells on the skin surface were collected by a cotton swab moistened with 80 µl PBS, then immediately plated on YPD-CAT agar. Skin at infection area was excised and dissociated in 500 µl of enzyme solution containing 1 mg ml−1 Collagenase Type II (Gibco), 1 mg ml−1 DNase I (Roche), incubated at 37 °C, 5.5% CO2. After 1.5 h, samples were homogenized with a homogenizer (IKA 3386000) for 30 s, followed by plating onto YPD-CAT agar plates to quantify colony-forming units. For short-term colonization, Candida cell suspensions were applied to the back skin once on day 0. Fungal burden was assessed on day 2 via cotton swab samples and whole biopsy digestion.

Native adult human skin samples were obtained within 1 to 2 h after plastic surgery procedures38. Initially, the skin underwent a cleansing process using PBS before being punctured with an 8 mm KAI Biopsy Punch tool (Heintel 29045435). Skin biopsies were then placed into a 12-well plate containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Fungal cells from exponential growth phase cultures were washed twice with PBS, and subsequently adjusted to 105 cells per ml using a CASY cell counter (Roche). Fungal cell suspensions (3 µl) were applied topically to the centre of the biopsies, with PBS serving as non-infected control and incubated at 30 °C under ambient air. After 24 h, biopsies were collected and washed in 1 ml of PBS by vortex-mixing for 10 s. Subsequently, biopsies were sectioned into four pieces and subjected to digestion with a 500 µl enzyme solution containing 1 mg ml−1 Collagenase Type II (Gibco) and 1 mg ml−1 DNase I (Roche) and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C, 5.5% CO2. Next, 500 µl PBS was added, and biopsies were homogenized with a mechanical tissue homogenizer (IKA 3386000) for 30 s. Washing suspension and homogenized biopsies were diluted and plated onto YPD-CAT agar for fungal burden assessment.

For all experiments, initial infection doses were adjusted using a CASY cell counter after 30 s of sonication and further verified by counting of colony-forming units. Cell density was also confirmed by recording OD600nm whenever efg1∆ was used in the experiments. Before infection, cell suspensions were vigorously vortex-mixed to minimize clumping and maintain planktonic cell suspensions that ensure uniform distribution.

Scanning electron microscopy and histological staining

The preparation of human skin biopsies for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed essentially as described previously76. In brief, biopsies were collected after 24 h and fixed in Karnovsky’s fixative (2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate puffer pH 7.4 from Morphisto) for at least 24 h. Samples were then washed two times in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4 °C (pH 7.3) for 2 min each, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95% and 100%) for 20 min each and immersed for 30 min in pure hexamethyldisilazane (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by air-drying. For SEM analyses, samples were sputter-coated with gold (Fisons Instruments Polaron Sputter Coater, SC7610) and examined with a scanning electron microscope (JSM 6310, Jeol) at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV.

Skin biopsies were collected 24 h after infection and fixed in 7.5% formaldehyde (SAV Liquid Production), before embedding in histology-grade paraffin (Sanova Pharma). Paraffin sections were subsequently immersed in xylene (ThermoFisher), followed by sequential treatments with 96% ethanol and 70% ethanol. Periodic acid–Schiff staining was performed in 5% periodic acid for 10 min, followed by a 20 min immersion in Schiff’s reagent (both from Merck). Counterstaining was carried out using haematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 min, followed by washing and treatment with 3% hydrochloric acid in ethanol. Finally, the sections were dehydrated, mounted with synthetic mounting medium (Eukitt, Sigma-Aldrich), and visualized under a bright-field microscope (Olympus AX70).

Bacterial-fungal co-culture assays

Bacteria from a Luria–Bertani agar plate were inoculated into 5 ml of Luria–Bertani liquid medium and incubated overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 200 r.p.m. The culture was then measured at OD600nm and diluted in PBS to an OD600nm of 0.5 for co-culture experiments. C. auris in the exponential phase was washed twice with dH2O and counted using a CASY cell counter. The fungal cells were adjusted to 2 × 107 cells per ml in dH2O and further serially diluted 10-fold for co-culture experiments.

In a 12-well plate, 2 ml of solid agar media was added per well for bacterial and fungal culture as shown in Extended Data Fig. 7d. For bacterial culture, Christensen urea agar (0.1% peptone, 0.1% glucose, 0.5% NaCl, 0.2% KH2PO4, 0.0012% phenol red, 2% urea, 1.5% agar, final pH 6.8 ± 0.2) was used and distributed to lines 2 and 3 of the plates. For Candida culture, YPD agar buffered to pH 5 with Na2HPO4 and citric acid was used. The same bacterial strain was spotted on lines 2 and 3, while different C. auris WT and mutant strains were spotted on lines 1 and 4, ensuring equal distances between fungal strains and bacterial cultures. The plates were sealed with plastic tape, placed in sealed plastic bags, and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism version 9.0 and rstatix R package version 0.7.2 (ref. 77). Unless otherwise specified, data represent means ± standard deviation from at least three biological replicates. For mouse experiments, 5–11 mice were used for each group. For human skin experiments, data were collected from three independent human donors. Significance was determined using t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni or Benjamini–Hochberg or Tukey’s or Dunnett’s post hoc tests for multiple comparisons. Cut-off P values indicating significance are given in figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The proteomics data were deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository78 with the dataset identifier PXD048342. RNA-seq data are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus database with the accession number GSE253332. Lipidomics datasets are provided in Supplementary Table 8. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for RNA-seq analysis workflow is available via Github at https://github.com/kakulab/CSP2024. The workflow for processing MaxQuant output tables is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5758974 (ref. 79).

References

Lionakis, M. S. & Chowdhary, A. Candida auris Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 1924–1935 (2024).

Ortiz-Roa, C. et al. Mortality caused by Candida auris bloodstream infections in comparison with other Candida species, a multicentre retrospective cohort. J. Fungi 9, 715 (2023).

Lone, S. A. & Ahmad, A. Candida auris—the growing menace to global health. Mycoses 62, 620–637 (2019).

Rossow, J. et al. Factors associated with Candida auris colonization and transmission in skilled nursing facilities with ventilator units, New York, 2016–2018. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, e753–e760 (2021).

Chowdhary, A., Sharma, C. & Meis, J. F. Candida auris: a rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLOS Pathog. 13, e1006290 (2017).

Lockhart, S. R. et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64, 134–140 (2017).

Lyman, M. et al. Worsening spread of Candida auris in the United States, 2019 to 2021. Ann. Intern. Med. 176, 489–495 (2023).

Trinh, P.-C., Duc-Minh, N.-L., Phuc-Loi, L., Narakorn, K. & Karl, K. Rapid in vitro evolution of flucytosine resistance in Candida auris. mSphere 0, e0097724 (2025).

Pappas, P. G. et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, e1–e50 (2016).

Carolus, H. et al. Acquired amphotericin B resistance leads to fitness trade-offs that can be mitigated by compensatory evolution in Candida auris. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 3304–3320 (2024).

Muñoz, J. F. et al. Genomic insights into multidrug-resistance, mating and virulence in Candida auris and related emerging species. Nat. Commun. 9, 5346 (2018).

Chauhan, A. et al. Multi-omics analysis of experimentally evolved Candida auris isolates reveals modulation of sterols, sphingolipids, and oxidative stress in acquired amphotericin B resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 124, 154–172 (2025).

Vincent, B. M., Lancaster, A. K., Scherz-Shouval, R., Whitesell, L. & Lindquist, S. Fitness trade-offs restrict the evolution of resistance to amphotericin B. PLOS Biol. 11, e1001692 (2013).

Rybak, J. M. et al. In vivo emergence of high-level resistance during treatment reveals the first identified mechanism of amphotericin B resistance in Candida auris. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 28, 838–843 (2022).

Jenull, S. et al. Transcriptomics and phenotyping define genetic signatures associated with echinocandin resistance in Candida auris. mBio 13, e00799-22 (2022).

Jenull, S. et al. Transcriptome signatures predict phenotypic variations of Candida auris. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, e662563 (2021).

Shivarathri, R. et al. Comparative transcriptomics reveal possible mechanisms of amphotericin B resistance in Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 66, e02276-21 (2022).

Trinh, P.-C., Tamires, B. & Karl, K. Gene dosage of PDR16 modulates azole susceptibility in Candida auris. Microbiol. Spectr. 0, e0265924 (2025).

Li, J., Coste, A. T., Bachmann, D., Sanglard, D. & Lamoth, F. Deciphering the Mrr1/Mdr1 pathway in azole resistance of Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 66, e0006722 (2022).

Kim, S. H. et al. Genetic analysis of Candida auris implicates Hsp90 in morphogenesis and azole tolerance and Cdr1 in azole resistance. mBio https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02529-18 (2019).

Chowdhary, A. et al. A multicentre study of antifungal susceptibility patterns among 350 Candida auris isolates (2009–17) in India: role of the ERG11 and FKS1 genes in azole and echinocandin resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 891–899 (2018).

Casal, M., Paiva, S., Queirós, O. & Soares-Silva, I. Transport of carboxylic acids in yeasts. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 974–994 (2008).

Kim, J.-S., Lee, K.-T., Lee Myung, H., Cheong, E. & Bahn, Y.-S. Adenylyl cyclase and protein kinase A play redundant and distinct roles in growth, differentiation, antifungal drug resistance, and pathogenicity of Candida auris. mBio https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02729-21 (2021).

Cottier, F. et al. The bZIP transcription factor Rca1p is a central regulator of a novel CO2 sensing pathway in yeast. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002485 (2012).

Ji-Seok, K., Kyung-Tae, L. & Yong-Sun, B. Deciphering the regulatory mechanisms of the cAMP/protein kinase A pathway and their roles in the pathogenicity of Candida auris. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0215223 (2023).

Du, H. et al. Candida auris: epidemiology, biology, antifungal resistance, and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008921 (2020).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

Avelar, G. M. et al. A CO2 sensing module modulates β-1,3-glucan exposure in Candida albicans. mBio 15, e0189823 (2024).

Bahn, Y.-S., Cox, G. M., Perfect, J. R. & Heitman, J. Carbonic anhydrase and CO2 sensing during Cryptococcus neoformans growth, differentiation, and virulence. Curr. Biol. 15, 2013–2020 (2005).

Chadwick, B. J. & Lin, X. Effects of CO2 in fungi. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 79, 102488 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. The intrinsically disordered region from PP2C phosphatases functions as a conserved CO2 sensor. Nat. Cell Biol. 24, 1029–1037 (2022).

Skrzypek, M. S. et al. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D592–D596 (2017).

Santana, D. J. & O’Meara, T. R. Forward and reverse genetic dissection of morphogenesis identifies filament-competent Candida auris strains. Nat. Commun. 12, 7197 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Brain glucose induces tolerance of Cryptococcus neoformans to amphotericin B during meningitis. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 346–358 (2024).

Salama, E. A. et al. Lansoprazole interferes with fungal respiration and acts synergistically with amphotericin B against multidrug-resistant Candida auris. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 13, 2322649 (2024).

Vincent, B. M. et al. A fungal-selective cytochrome bc1 inhibitor impairs virulence and prevents the evolution of drug resistance. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 978–991 (2016).

Hall, R. A. et al. CO2 acts as a signalling molecule in populations of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. PLOS Pathog. 6, e1001193 (2010).

Seiser, S. et al. Native human and mouse skin infection models to study Candida auris-host interactions. Microbes Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2023.105234 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Murine model of colonization with fungal pathogen Candida auris to explore skin tropism, host risk factors and therapeutic strategies. Cell Host Microbe 29, 210–221.e6 (2021).

Williams, R., Philpott, M. P. & Kealey, T. Metabolism of freshly isolated human hair follicles capable of hair elongation: a glutaminolytic, aerobic glycolytic tissue. J. Invest. Dermatol. 100, 834–840 (1993).

Proctor, D. M. et al. Integrated genomic, epidemiologic investigation of Candida auris skin colonization in a skilled nursing facility. Nat. Med. 27, 1401–1409 (2021).

Fitzgerald, M. J., Pearson, M. M. & Mobley, H. L. T. Proteus mirabilis UreR coordinates cellular functions required for urease activity. J. Bacteriol. 206, e0003124 (2024).

Jones, B. D., Lockatell, C. V., Johnson, D. E., Warren, J. W. & Mobley, H. L. Construction of a urease-negative mutant of Proteus mirabilis: analysis of virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 58, 1120–1123 (1990).

Beredaki, M.-I., Sanidopoulos, I., Pournaras, S. & Meletiadis, J. Defining optimal doses of liposomal amphotericin b against Candida auris: data from an in vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. J. Infect. Dis. 229, 599–607 (2024).

McClenny, N. B. et al. Change in colony morphology of Candida lusitaniae in association with development of amphotericin B resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1325–1328 (2002).

Andes, D., Stamsted, T. & Conklin, R. Pharmacodynamics of amphotericin B in a neutropenic-mouse disseminated-candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 922–926 (2001).

Anderson, T. M. et al. Amphotericin forms an extramembranous and fungicidal sterol sponge. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 400–406 (2014).

Patrick, V. et al. Identification and functional characterization of Rca1, a transcription factor involved in both antifungal susceptibility and host response in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 11, 916–931 (2012).

Tao, L. et al. Integration of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle with cAMP signaling and Sfl2 pathways in the regulation of CO2 sensing and hyphal development in Candida albicans. PLOS Genet. 13, e1006949 (2017).

Cottier, F. et al. Carbonic anhydrase regulation and CO2 sensing in the fungal pathogen Candida glabrata involves a novel Rca1p ortholog. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 1549–1554 (2013).

Kim, M. S. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the CO2 sensing pathway via differential expression of carbonic anhydrase in Cryptococcus neoformans. Genetics 185, 1207–1219 (2010).

Bagherani, N. et al. An overview of the role of carboxytherapy in dermatology. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 22, 2399–2407 (2023).

Byrd, A. L., Belkaid, Y. & Segre, J. A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 143–155 (2018).

Pasut, A., Lama, E., Van Craenenbroeck, A. H., Kroon, J. & Carmeliet, P. Endothelial cell metabolism in cardiovascular physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-025-01162-x (2025).

Cui, C.-Y. & Schlessinger, D. Eccrine sweat gland development and sweat secretion. Exp. Dermatol. 24, 644–650 (2015).

Nakashima, K. et al. Gap junction-mediated contraction of myoepithelial cells induces the peristaltic transport of sweat in human eccrine glands. Commun. Biol. 6, 1175 (2023).

Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard. M27-A3 (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2008).

Fatsis-Kavalopoulos, N., Sánchez-Hevia, D. L. & Andersson, D. I. Beyond the FIC index: the extended information from fractional inhibitory concentrations (FICs). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 79, 2394–2396 (2024).

Jung, K.-W. et al. Systematic functional profiling of transcription factor networks in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat. Commun. 6, 6757 (2015).

Phan-Canh, T. et al. White-Brown switching controls phenotypic plasticity and virulence of Candida auris. Cell Rep. 44, 115976 (2025).

Bitencourt, T. et al. Integrated multi-omics identifies pathways governing interspecies interaction between A. fumigatus and K. pneumoniae. Commun. Biol. 7, 1496 (2024).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Wu, T. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2, 100141 (2021).

Schwarzmüller, T. et al. Systematic phenotyping of a large-scale Candida glabrata deletion collection reveals novel antifungal tolerance genes. PLOS Pathog. 10, e1004211 (2014).

Nguyen, N., Quail, M. M. F. & Hernday, A. D. An efficient, rapid, and recyclable system for CRISPR-mediated genome editing in Candida albicans. mSphere https://doi.org/10.1128/mspheredirect.00149-17 (2017).

Istel, F., Schwarzmüller, T., Tscherner, M. & Kuchler, K. Genetic transformation of Candida glabrata by electroporation. Bio Protoc. 5, e1528 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Targeting epigenetic regulators to overcome drug resistance in the emerging human fungal pathogen Candida auris. Nat. Commun. 16, 4668 (2025).

Park, S. O., Frazer, C. & Bennett, R. J. An adjuvant-based approach enables the use of dominant HYG and KAN selectable markers in Candida albicans. mSphere 7, e0034722 (2022).

Kühbacher, A. et al. The cytochrome P450 reductase CprA is a rate-limiting factor for Cyp51A-mediated azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 67, e0091823 (2023).

Müller, C. et al. Sterol composition of clinically relevant mucorales and changes resulting from posaconazole treatment. Molecules 23, e23051218 (2018).

Bligh, E. G. & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 (1959).

Troppmair, N. et al. Accurate sphingolipid quantification reducing fragmentation bias by nonlinear models. Anal. Chem. 95, 15227–15235 (2023).

Peng, B. et al. LipidCreator workbench to probe the lipidomic landscape. Nat. Commun. 11, 2057 (2020).

Peng, B. et al. A comprehensive high-resolution targeted workflow for the deep profiling of sphingolipids. Anal. Chem. 89, 12480–12487 (2017).

Penninger, P. et al. HDAC1 fine-tunes Th17 polarization in vivo to restrain tissue damage in fungal infections. Cell Rep. 43, e114993 (2024).

Araujo, R., Cámara, N. & Ramos, M. A. Glochidium metamorphosis in the endangered freshwater mussel Margaritifera auricularia (Spengler, 1793): a histological and scanning electron microscopy study. J. Morphol. 254, 259–265 (2002).

Kassambara, A. rstatix: Pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. R package version 0.7. 0. CRAN: Contributed Packages (2021).

Perez-Riverol, Y. et al. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D543–D552 (2022).

Chen, W. & Madern, M. moritzmadern/Cassiopeia_LFQ: v.4.7.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5758974 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Petryshyn, S. Volkan and all other lab members for their technical support and experimental advice. Moreover, we thank N. Chauhan (Center for Discovery and Innovation) for providing clinical isolates; T. O’Meara (University of Michigan Medical School) for providing the plasmids pTO135, pTO149 and pTO136; C. Chen (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and S. Znaidi (Memorial University of Newfoundland) for providing plasmid pCB323; M. Bradley (Queen Mary University of London) for the gift of Cy5-conjugated AMB; A. Brakhage (Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology-Hans-Knöll-Institute) for providing Trichophyton benhamiae (WT and stuA mutants); C. Freystätter (Medical University of Vienna) for providing the skin samples. We thank C. Nobile (University of California, Merced) and A.E.-B. for serving as members on the PhD Thesis Committee of T.P.-C; P.-L. Luu (Thong Nhat Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City) for guiding in bioinformatics. We are grateful to human volunteers donating native skin tissues. K.K. was supported by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (ChromFunVir - P-32582-B08, Candidomics - P-33425, and in part by FWF-SFB70-08). A.E.-B. received funds from the Austrian Science Fund - FWF (P-31485-B30) and the LEO Foundation (LF-OC-23-001332). T.P.-C. was supported by a Student Fellowship, Ernst Mach Grant, a Bernd Rode Award 2024 from ASEAN – European Academic University Network (ASEA-UNINET) network and the ESCMID Research Grant 2023 from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; T.P.-C. was also supported in part by the LEO Foundation (LF-OC-23-001332). H.A., I.T. and T.P.-C. were supported by the FWF-funded PhD training program (TissueHome – FWF-DOC32-B28). N.K. was supported in part by the LEO Foundation (LF-OC-23-001332). A.C. is a fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Fungal Kingdom. N.N.T., C.C. and R.A. received support from the Faculty of Chemistry, University of Vienna - Mass Spectrometry Centre, with funding from the Vienna Doctoral School in Chemistry and DigiOmics4Austria: BMBWF ‘(Digitale) Forschungsinfrastrukturen’.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.P.-C. and K.K. conceived the project and designed experiments. K.K. provided PhD supervision and mentoring. K.K., A.E.-B. and T.P.-C. acquired funding. T.P.-C. conducted most experiments, data analysis and visualization. A.E.-B. coordinated ethics approval and human skin sample collection and contributed to data interpretation. S.S., D.C. and D.M. performed human skin infections and SEM. P.P., I.T., T.B. and H.A. contributed to mouse experiments. N.N.T., C.C. and R.A. performed lipidomics analysis. W.C. and M.H. performed proteomics analyses. A.K., G.I. and S.J. supported cloning experiments. N.K. performed computational docking. L.-M.Z., M.L. and C.M. performed sterol analysis and antifungal susceptibility testing. H.L.T.M. contributed to bacterial experiments. A.C. provided clinical strains. T.P.-C. and K.K. wrote the manuscript with important contributions from A.E.-B. and input from all other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks Iliyana Kaneva, Shankar Thangamani and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Proteomics reveals potential drug-resistant mechanisms.