Abstract

The Crayfish Optimization Algorithm (COA) is a recent powerful algorithm that is sometimes plagued by poor convergence speed and a tendency to rapidly converge to the local optimum. This study introduces a variation of the COA called Adaptive Dynamic COA with a Locally enhanced escape operator (AD-COA-L) to tackle these issues. Firstly, the algorithm utilizes the Bernoulli map initialization strategy to quickly establish a high-quality population that is evenly distributed. This helps the algorithm to promptly reach the proper search area. Additionally, in order to mitigate the likelihood of getting trapped in local optima and improve the quality of the obtained solution, an Adaptive Lens Opposition-Based Learning (ALOBL) mechanism is applied. Moreover, the local escape operator (LEO) is utilized to aggressively discourage the adoption of isolated solutions and encourage the sharing of information within the search area. Finally, a new inertia weight is suggested to improve the search capability of COA and prevent it from being stuck in local optima by enhancing the exploitation capability of COA. AD-COA-L is evaluated against eight advanced state-of-the-art variations and ten classical and recent metaheuristic algorithms on 29 benchmark functions from CEC2017 of varying dimensions (50 and 100). AD-COA-L demonstrates superior accuracy, balanced exploration-exploitation and convergence speed, compared to other algorithms across most benchmark functions. Furthermore, we evaluated the proficiency of AD-COA-L in tackling seven demanding real-world and restricted engineering optimization challenges. The experimental findings clearly illustrate the competitiveness and advantages of the proposed AD-COA-L algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI), optimization has become a crucial mathematical methodology to find an optimum solution among complex problems in all walks of life. Optimization has gained wide applications in fault diagnosis1, service composition2, the agriculture field3, path planning4, image segmentation5, intrusion detection6,7, feature selection8,9, and parameter identification of photovoltaic models10. Most of these optimization tasks involve high complexity due to large-scale dimensionality, non-linearity, and non-convexity, which are computationally challenging11. It is well known that single-objective optimization, dealing with the optimal solution for a single performance criterion, often faces complex landscapes. In contrast to multi-objective optimization, where a set of non-dominated solutions represented by a Pareto front is produced, the present study deals exclusively with single-objective optimization12. The challenge is increased due to the scale and complexity of the problem at hand.

Traditional methods for solving optimization problems include classical techniques such as linear programming13, Newton’s method14, and conjugate gradient methods15. While these methods might work quite well for small or relatively simple problems, they often tend to break down when real-world applications involving thousands of variables and a multitude of constraints are considered. These traditional methods are highly time-consuming and also tend to converge prematurely to local optima, especially in non-convex problem spaces16. Therefore, in more realistic high-dimensional optimization settings, these methods usually cannot produce a solution that would be satisfactory.

Therefore, in the last few decades, many researchers have been developing Metaheuristic Algorithms (MAs) in order to surmount the limitations of the classical methods, by allowing greater flexibility and robustness while handling complex optimization problems17. MAs represent a class of stochastic optimization techniques that do not use gradient information for the optimization process; hence, it is also suitable for solving nonlinear, nonconvex, high-dimensional problems. Unlike in the case of classical methods, these metaheuristics are superior to them because they can handle complex search spaces by effectively combining global and local search strategies that enable them to avoid local optima and reach near-optimal solutions with efficiency. Their ability to balance exploration and exploitation has made them highly popular in diverse optimization tasks18.

MAs are typically inspired by many natural phenomena, including physical principles biological behaviors, human habits, and more. Various categories of MAs are present in the literature. In19, the authors classify MAs into two main groups: evolutionary algorithms and swarm intelligence algorithms. Furthermore, in20, the authors classify MAs into three distinct categories: evolutionary algorithms, swarm intelligence algorithms, and physical algorithms. On the other hand, the authors in21 categorize MAs as either single- or population-based solutions. Generally, there is no widely agreed upon criterion for categorizing metaheuristic algorithms. Nevertheless, the classification criteria that are most frequently employed are derived from a wide range of sources of inspiration. This work categorizes MAs into five broad groups: physical, evolutionary, swarm-based, mathematical, and human-based22. Evolutionary algorithms primarily imitate biological strategies, such as reproduction, genetic diversity, and mutational adaptation. The search process begins with a random population and then iterates constantly to accomplish multi-generational evolution. This category includes, for instance, Genetic Algorithm (GA)23, Differential Evolution (DE)24, and Liver Cancer Algorithm (LCA)25. The second category refers to mathematical algorithms26, for instance, Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA)27, Gradient Based Optimizer (GBO)28, the Weighted Mean of Vectors (INFO)29, and the Sine-Cosine Algorithm (SCA)30. The third category of algorithms refers to physics-based algorithms which replicate the behavior of physical events and their governing principles, such as magnetic fields, gravity, and mass equilibrium. The examples of this category include Simulated Annealing (SA)31, Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA)32, Kepler Optimization Algorithm (KOA)33, Rime Optimization Algorithm (RIME)34, and. The fourth category pertains to human cooperation and behaviors within a society, referred to as human-based algorithms such as Teaching Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO)35, Human memory optimization algorithm (HMO)36, and Human evolutionary optimization algorithm (HEOA)37. The final category relates to swarm-based techniques, which are based on the collective behaviors of organisms in clusters, such as breeding, foraging, and hunting. This category includes a diverse range of algorithms such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)38, Slime Mould Optimizer (SMA)39, Crayfish optimization algorithm (COA)40, Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO)41, Spider Wasp Optimizer (SWO)42, and Dung Beetle Optimization (DBO)43.

Despite their successes, many issues appear regarding MAs. Among the most important ones, there is the trade-off between exploration and exploitation. Exploration is the process by which the algorithm explores new, unexplored regions of the solution space in order to find multiple possible solutions. On the other hand, the exploitation phase generally needs the intensification of known promising solutions in order to achieve an optimum. A good balance between these two processes basically poses the challenge for any MA to be successful44. Additionally, MAs generally suffer from slow convergence rates, loss of accuracy as the problem becomes highly complex, and the tendency to get stuck in local optima, especially in high-dimensional space45. Due to these challenges regarding MAs, much research effort has focused on improving existing MAs by adding new strategies and hybridizing strategies from multiple algorithms46. The improvements aim at increasing the convergence speed, enhancing the solution’s accuracy, and enhancing the algorithm’s capability of escaping from local optima.

The Crayfish Optimization Algorithm (COA) is an innovative MA developed by Jia in 2023, inspired by the survival strategies observed in crayfish populations. This algorithm draws inspiration from crayfish behaviors such as avoiding heat, competing for shelter, and searching for food. Previous investigations have emphasized that, when compared to several traditional MA, its shared advantages include a versatile structure, a reduced number of parameter settings, and high accuracy. However, COA unavoidably has certain limitations, which is why this paper advocates for an enhanced version of COA. The main limitations of COA include: (1) The COA approach demonstrates insufficient accuracy and slow convergence when dealing with high-dimensional and non-convex issues. 2) when faced with complicated engineering optimization difficulties, COA is susceptible to getting stuck in local optima due to a large number of non-linear constraints. 3) the No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem47 states that “no MA can be guaranteed to work for all optimization applications” which motivates employing suitable tactics to enhance the efficiency and potential success of COA in addressing practical engineering problems.

To address these limitations, an Adaptive Dynamic Crayfish Optimization Algorithm with the improved escape operator, namely AD-COA-L, is proposed. Four main strategies are embedded in this variant of COA to enhance the performance of this algorithm:

-

Bernoulli Map Initialization: This strategy is used in initialization so that a uniformly distributed population can be formed to enhance diversity from the initialization for the better exploration of the search space.

-

Adaptive Dynamic Inertia Weight: This strategy updates the inertia weight dynamically in the exploitation phase to reserve the superior solutions and build up the search capability of the algorithm during iterations.

-

Local Escape Operator (LEO): LEO strengthens local exploitation with a view to strengthening information exchange between search agents, balancing exploration and exploitation, and hence enhancing the quality of the solution.

-

Adaptive Lens Opposition-Based Learning: the ALOBL strategy moves the current best solution in the opposite direction, in later iterations, in order to avoid local optima and therefore increase the probability of global convergence.

In this regard, convergence speed, solution accuracy, and robustness of AD-COA-L have been strictly tested on 29 benchmark functions selected from the IEEE CEC2017 dataset. Also, this work compares the performance of the AD-COA-L with that of several state-of-the-art MAs. Furthermore, AD-COA-L is applied to seven constrained real-world engineering design problems to validate its practical effectiveness. The primary contributions are outlined as follows:

-

An improved version of COA is proposed, AD-COA-L, which includes four major strategies to enhance the overall performance of COA including Bernoulli map initialization for diversity in the population, adaptive dynamic inertia weight for enhancing exploitation, local escape operator for improving local exploration, and ALOBL to prevent local optima.

-

The strength of AD-COA-L is verified using 29 CEC2017 test functions. The acquired results are compared with several state-of-the-art methodologies and high-performance modified variant algorithms.

-

The effectiveness of AD-COA-L in addressing intricate real-world optimization difficulties is confirmed by analysis of seven engineering design scenarios.

-

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Friedman ranking test provide evidence that AD-COA-L outperforms other competing algorithms in terms of solution correctness, convergence rate, and resilience.

The subsequent sections of this study are structured as follows: Sect. 2 provides a summarized overview for the recent literature works. Section 3 provides an in-depth explanation of the principles and mathematical models that form the foundation of COA. Section 4 introduces the development of a sophisticated crayfish optimization algorithm called AD-COA-L, which utilizes multiple strategies to optimize its performance. The evaluation of the optimization performance of AD-COA-L on the CEC2017 benchmark suites is conducted in Sect. 5. Section 6 demonstrates the efficacy of AD-COA-L in seven real-world applications by presenting several examples of limited engineering design. Section 7 summarizes the result and presents possible directions for future research.

Related work

Hu et al.48 introduced an enhanced hybrid AOA named CSOAOA to improve exploitation, avoid local optima, and increase convergence accuracy. CSOAOA incorporated point set initialization, optimal neighborhood learning, and crisscross optimization strategies. It was validated on 23 classical benchmark functions, CEC2019, and CEC2020 test suites, showing significant improvements in precision and convergence rate. Statistical tests confirmed that CSOAOA’s potential as a powerful algorithm for complex engineering optimization problems.

Shen et al.49 proposed MEWOA, a WOA variant using multi-population evolution to improve convergence speed and avoid local optima. MEWOA divided individuals into exploratory, exploitative, and modest sub-populations with different search strategies. It was tested on 30 benchmarks and real-world problems; MEWOA outperformed five WOA variants and seven metaheuristics in convergence speed, runtime, and solution accuracy, demonstrating its competitiveness. Qiao et al.50 proposed a hybrid AOA-HHO algorithm for Multilevel Thresholding Image Segmentation (MTIS) to improve threshold selection for object detection. Combining AOA’s exploration strengths with HHO’s exploitation abilities, AOA-HHO outperformed AOA, HHO, and other MAs. It used the image features as the fitness function, experiments on seven test images show superior segmentation accuracy, PSNR, SSIM, and execution time. Qiu et al.51 proposed an improved Gray Wolf Optimization (IGWO) algorithm to enhance the traditional GWO’s convergence speed, solution accuracy, and ability to escape local minima. IGWO used lens imaging reverse learning for initial population optimization, a nonlinear control parameter strategy, and tuning inspired by TSA and PSO. It was tested on 23 benchmarks, 15 CEC2014 problems, and 2 engineering problems; IGWO showed superior performance and balance in global optimization. Houssein et al.52 proposed mSTOA, an improved Sooty Tern Optimization Algorithm for feature selection (FS) to avoid sub-optimal convergence. mSTOA employed strategies for balancing exploration/exploitation, self-adaptive control parameters, and population reduction. It was validated on CEC2020 benchmarks and tested against various algorithms; mSTOA demonstrated superior performance in extracting optimal feature subsets, with statistical analyses confirming its effectiveness.

Wu et al.53 proposed a novel variant of the Ant Colony Optimization algorithm (MAACO) for mobile robot path planning to address slow convergence and inefficiency. MAACO introduced orientation guidance, an improved heuristic function, a new state transition rule, and uneven pheromone distribution. Experiments demonstrated MAACO’s superiority over 13 existing approaches in reducing path length, turn times, and convergence speed, proving its efficiency and practicality.

Nadimi-Shahraki et al.54 proposed an enhanced Whale Optimization Algorithm (E-WOA) using a pooling mechanism and three effective search strategies to address WOA’s low population diversity and poor search strategy. E-WOA outperformed existing WOA variants in solving global optimization problems. The binary version, BE-WOA, was validated on medical datasets, showing superior performance in feature selection, particularly for COVID-19 detection, compared to other high-performing algorithms.

Askr et al.55 proposed Binary Enhanced Golden Jackal Optimization (BEGJO) for feature selection (FS) to tackle high-dimensional datasets. BEGJO improved the original GJO by incorporating Copula Entropy for dimensionality reduction and four enhancement strategies to boost exploration and exploitation. It used the sigmoid transfer function where BEGJO outperformed other algorithms in classification accuracy, feature dimension, and ranks fourth in processing time, validated through statistical evaluations.

Ozkaya et al.56 proposed a novel Adaptive Fitness-Distance Balance based Artificial Rabbits Optimization (AFDB-ARO) algorithm to solve the complex Combined Heat and Power Economic Dispatch (CHPED) problem. AFDB-ARO enhanced exploration and balances exploitation, outperforming the base ARO in benchmark tests. It was applied to CHPED systems with various unit configurations, AFDB-ARO achieved optimal solutions in most cases, demonstrating superior performance and stability compared to ARO. Yıldız et al.57 proposed a novel hybrid optimizer, AOA-NM, combining Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA) and Nelder–Mead local search to improve solution quality and avoid local optima traps. AOA-NM’s performance was validated on CEC2020 benchmarks and ten constrained engineering design problems, showing superior results compared to other metaheuristics. Comparative analysis confirmed AOA-NM’s robustness in solving complex engineering and manufacturing problems. Deng et al.58 proposed an improved Whale Optimization Algorithm (IWOA) to address WOA’s slow convergence, low precision, and tendency to fall into local optima. IWOA used chaotic mapping for population initialization, integrates black widow algorithm pheromone and opposition-based learning for population modification, and employed adaptive coefficients and new update modes. It was tested on 23 benchmark functions; IWOA demonstrated superior convergence speed, stability, accuracy, and global performance compared to other optimization algorithms. Tan and Mohamad-Saleh59 proposed a hybrid Equilibrium Whale Optimization Algorithm (EWOA), combining bio-inspired WOA and Equilibrium Optimizer (EO). EWOA integrated WOA’s encircling and attacking mechanisms with EO’s weight balance strategy. It was tested on multiple benchmark sets; EWOA outperformed six state-of-the-art algorithms in terms of statistical mean performance, convergence rate, and robustness. EWOA achieved the best results on 46 out of 101 functions, demonstrating superior optimization efficiency. The Mahajan et al.60 proposed a hybrid method combining Aquila optimizer (AO) and AOA to enhance convergence and result quality. It was tested on various problems, including image processing and engineering design, AO-AOA demonstrated effectiveness in both high- and low-dimensional problems. The results showed efficient search results, particularly in high-dimensional problems, validating the approach. Qian et al.61 introduced a hybrid SSACO method that combines the foraging model of the salp swarm algorithm with the ant colony optimizer. The salp foraging behavior in SSACO effectively improved the original algorithm’s capacity to avoid local optima, resulting in a large increase in convergence accuracy. The application of SSACO to remote sensing image segmentation had yielded successful results. The evaluation of these results, based on peak signal-to-noise ratio, structural similarity index, and feature similarity index, had demonstrated that this method possessed distinct benefits over comparable segmentation methods.

Zhu et al.62 proposed the QHDBO algorithm, an enhanced Dung Beetle Optimization algorithm incorporating quantum computing and multi-strategy hybridization to address local optimum issues. QHDBO improved initial population distribution, balances global and local search, and used a t-distribution variation strategy. It was tested on 37 functions and engineering problems, QHDBO showed improved convergence speed, optimization accuracy, and robustness. Table 1 summarize the reviewed related and existing works to highlight the points of strength and weakness to motivate the need for the proposed work in this paper.

According to the analysis of related works in Table 1, although performances of various MAs have enhanced over many reviewed related works, a lot of their shortcomings remain unsolved. Most of the available methods suffer from an imbalance between the exploration-exploitation principle, though they have converged to an optimal solution on certain problem domains. Besides, they often result in a phenomenon called premature convergence, when the algorithm converges into local optima without proper exploration of the solution space. Also, several related works, though improved in enhancing the speed of convergence, depict poor performance on complex, high-dimensional problems including a large and non-convex search space.

Furthermore, most of the works done previously are mainly dependent on fine-tuning control parameters toward optimal results. This very dependence makes these algorithms less general, with increased computational costs especially when it deals with large-scale or real-world applications. Their effectiveness is immensely reduced in problems of higher dimensions due to limited explorative capabilities.

The proposed AD-COA-L will directly address these gaps through the incorporation of a number of adaptive mechanisms. With the Bernoulli map, initialization is guaranteed to result in greater diversity of population at the very beginning. Adaptive dynamic inertia weight maintains a balance between exploration and exploitation in the process to ensure that neither of these phases ever dominates, hence avoiding premature convergence. The local escape operator enhances local exploration and allows the algorithm to move away from local optima. In addition, the ALOBL mechanism strengthens the exploration power of the algorithm for high-dimensional spaces. These merits of enhancement indicate that the new algorithm, namely AD-COA-L, will have better convergence, ensure the solution quality, and be more effective for complex, high-dimensional optimization problems compared to the previously developed algorithms.

Crayfish optimization algorithm (COA)

In 2023, researchers introduced the COA40, which replicates crayfish behaviors: competitive behavior, summer resort behavior, and foraging behavior. These behaviors align with the exploitation and exploration phases of optimization, influenced by temperature. Higher temperatures lead crayfish to seek cave refuge for rest or competition, while suitable temperatures promote foraging during exploration. Temperature adjustments produce unpredictability in finding optimal solutions. The main stages of COA are follows:

-

Initialization: In COA, an optimization problem with dimensions is represented by each crayfish, which serves as a potential solution in the form of a \(\:1\times\:d\) vector. Each variable \(\:({X}_{1},\:{X}_{2},\:{X}_{3},\:…,\:{X}_{d})\) represents a particular point \(\:X\) within the search space, which is constrained by an upper boundary \(\:Ub\) and a lower boundary \(\:Lb\). During each iteration of the process, the most optimal solution is computed. The solutions are compared in a step-by-step manner, and the most favorable choice is found and retained as the ultimate optimal solution. The initial distribution of the COA population is established using Eq. (1):

where the optimization problem’s borders are represented by \(\:Ub\) and \(\:Lb\). The temperature is a crucial factor in multiple stages of the crayfish and is defined by Eq. (2). When the temperature exceeds 30 degrees, the crayfish relocates to a cooler area as its summer sanctuary. The crayfish exhibits its foraging activity when the temperature is suitable.

Therefore, the act of searching for food can be replicated by employing a Gaussian distribution, which is influenced by the temperature as described in Eq. (3):

where the temperature of the best crayfish is represented by \(\:\mu\:\), whereas the parameters \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:\sigma\:\) regulate the different temperatures of crayfish.

-

Summer resort phase: In the summer, when the temperature exceeds 30 °C, crayfish actively seek out cool and moist tunnels to avoid the harmful effects of the heat. The method for determining these caverns is defined in Eq. (4):

According to Eq. (4), the best position is denoted as \(\:{X}_{B}\), whereas the current position of the population is called \(\:{X}_{L}\). Conversely, if the random number is below 0.5, there is no rivalry among the crayfish. Instead, they promptly assume possession of the cave in the following manner:

where the position of the crayfish in the next iteration is represented as \(\:{X}_{new}\), the position of the current crayfish is represented as \(\:{X}_{i}\), and the maximum number of iterations is denoted as \(\:T\).

-

Competition phase: When the temperature exceeds 30 °C and the random variable rand is 0.5 or higher, it signifies that the crayfish are experiencing competition from other crayfish for the cave. The new position is calculated using Eq. (7):

N represents the total count of agents in the current population.

-

Foraging phase: when the temperature reaches or falls below 30 °C, crayfish are prompted to leave their caves in order to search for food. At elevated temperatures, crayfish emerge from their burrows and locate food by utilizing the optimal place they determined during their evaluation. The food’s position is determined using the following:

The consumption of crayfish is influenced by both their feeding rate and the size of the food they consume. If the food is overly large, the crayfish are unable to swallow it instantly; instead, they must first deconstruct it with their pincers. The size of the food is calculated using Eq. (10):

where \(\:{C}_{3}\) represents the maximum size of food, which is set at a specific value of 3. The variable \(\:{F}_{i}\) represents the fitness score of the crayfish with the index , while \(\:{F}_{food}\) represents the fitness score of the crayfish with the index and a specific food source.

Crayfish assess the magnitude of the meal by taking into account its maximal nutritional worth, \(\:Q\), in order to select their feeding approach. If the value of exceeds (\(\:{C}_{3}\) + 1)/2, it indicates that the food is too huge to be consumed directly. The formula for crushing food is as stated:

Then, the crayfish employ their second and third claws to alternately grip the food and move it into their mouth. The equation representing the alternative feeding behavior of crayfish is given by Eq. (12):

If the value of is less than or equal to (\(\:{C}_{3}\) + 1)/2, it indicates that the crayfish may consume the meal instantly because it is an adequate size. The equation representing the feeding behavior of crayfish is given by Eq. (13):

Finally, the greedy selection process is utilized to choose between the newly updated position and the present solution as follows:

The proposed AD-COA-L algorithm

This research presents a novel approach called AD-COA-L and utilizes it to address global optimization and engineering design challenges. Four main improvements guide the COA toward better solutions and obtain high quality fitness solutions. The details of these introduced strategies are explained in the following subsequent subsections.

Bernoulli map-based population initialization

The fundamental aspect of metaheuristic algorithms lies in the iterative process of evaluating potential solutions. Consequently, the beginning population plays a crucial role in determining the algorithm’s convergence and exploration. Furthermore, it is widely recognized that the initialization phase of the majority of MAs involves generating random values within a specific range, following a Gaussian distribution. This initialization process has a significant impact on the progress and optimization quality. On the other hand, Chaotic maps are employed to produce chaotic sequences, which are sequences of unpredictability generated by straightforward deterministic systems. Chaotic maps exhibit non-linearity, a strong sensitivity to beginning conditions, ergodicity, randomness, chaotic attractors, fractional maintenance, overall stability, local instability, and long-term unpredictability. Thus, in the realm of optimization, chaotic maps are frequently employed as substitutes for the pseudo-random number generator \(\:rand\) to produce chaotic numbers within the range of 0 to 1. Experimental evidence has shown that employing chaotic sequences for population initialization, selection, crossover, and mutation has a significant impact on the algorithm’s performance, typically resulting in superior convergence compared to utilizing random sequences9. The Bernoulli map is a common example of a chaotic system. The system is characterized as a segmented chaotic system, using the following formula:

where the parameter is a randomly chosen value between 0 and 0.5, typically with a value of 0.29 63. The notation \(\:{S}_{i,j}\) represents the \(\:{j}^{th}\) dimension of the \(\:{i}^{th}\) monochromatic wave.

In other words, the AD-COA-L introduces an initialization of the population based on the Bernoulli map with the aim of improving the exploration capability since the early stages of the optimization process. In the original COA, the population is initialized randomly within a fixed range and can result in some uneven or even suboptimal distribution of solutions. Such random initialization may imply the algorithm has only a limited capability of exploring the search space in depth, getting trapped into premature convergence to local optima.

In the random initialization, the highly sensitive initial condition-dependent chaotic sequence is now the Bernoulli map. The use of the Bernoulli map in the AD-COA-L guaranteed uniformity in the spread of population across the search space besides ensuring diversity. This strategy will enhance the quality of the population by generating a more diverse set of initial solutions, which enables the algorithm to explore more promising areas much earlier in the search process. This also helps to reduce the possibility of getting trapped into a local minimum, thereby helping to accelerate convergence toward the global optimum.

Dynamic inertia weight coefficient

In the basic COA algorithm, the inertia weight value remains constant at 1. Consequently, the algorithm is prone to getting stuck in local minima. To address this issue, it has been recommended in64 to set the inertia weight value to a variable \(\:w\) that is updated during iterations, leading to improved convergence. In this regard, the proposed AD-COA-L algorithm utilizes a variable value for the inertia weight coefficient, as described in Eq. 17:

The adaptive inertia weight function, denoted as , is periodic function with represents a varied value, with possible values ranging from 1 to 0 in increments of 0.1. The variable \(\:t\) represents the current iteration, while \(\:T\) represents the maximum number of iterations. The inertia weight is added to both the competition and foraging phases of COA to boost the convergence speed at later iterations and helps AD-COA-L to avoid falling the local optima. The updated competition and foraging phases of AD-COA-L are represented by Eqs. (18–20) instead of Eqs. (7), (12) and (13).

The dynamic inertia weight coefficient not only enhances the exploration and exploitation capabilities of AD-COA-L but also ensures an effective balance between the two throughout the optimization process. The inertia weight is set to higher values in the early iterations in order to give more emphasis on global exploration. This higher value of inertia weight inspires the solutions to traverse a larger area of the search space; thus, the algorithm does not get entrapped into the local optima at the beginning. Enabling solutions to travel larger distances, AD-COA-L increases the chances of finding new diversified regions, hence reinforcing its exploration power.

As iterations grow and the algorithm starts to converge toward potential promising regions, the inertia weight starts to decrease. As a result, the algorithm now moves its focus from a broad exploration toward the exploitation of the best solutions found so far. A smaller inertia weight makes the search more local, which can enable the algorithm to fine-tune and refine the solutions in these high-potential regions. This refined search process amplifies the algorithm’s capability for higher accuracy and attainment of optimal solutions.

Furthermore, the balance between exploration and exploitation depends on the value of the probability parameter \(\:p\) in the AD-COA-L algorithm. Higher values of \(\:p\) in early stages allow wider explorations because it enables the solutions to make larger movements across the search space, thus preventing it getting stuck in local optima. Conversely, during runtime, if the value of \(\:p\) is decreased, it guides the algorithm toward exploitation for more refined, local adjustments in the solutions for fine-tuning and optimization. This dynamic adjustment of \(\:p\), combined with the adaptive inertia weight, maintains appropriate exploration-exploitation trade-offs so that the algorithm is always effectively exploring new areas while continually exploiting the best-found solutions for better convergence without getting stuck prematurely.

The AD-COA-L algorithm operates to keep a good balance between exploration and exploitation by varying the inertia weight dynamically with iteration count. It starts giving importance to wide exploration in its early iterations to ensure that the algorithm has scanned the solution space well and, in later stages, gives more importance to exploitation in order to tune the best-found solutions. This is important in avoiding premature convergence and maintaining efficient convergence toward global optima. Dynamic adjustment can assure that AD-COA-L will adaptively switch between exploration and exploitation to obtain more robust optimization performance.

Adaptive lens reverse learning strategy

It is analyzed that the COA depends on the best solution \(\:{X}_{B}\) during the position update of different phases as mentioned in Eqs. (5), (7) and (12) where new candidate solution is created by directing the current individual towards the global optimal point \(\:{X}_{B}\). During the optimization process, the majority of individuals in the population have a tendency to gather around the perceived current best solution. Therefore, the COA is prone to early convergence. The primary research focus in improving COA is centered on enhancing its ability to overcome local optima. One widely used approach in the existing literature to strengthen the worldwide investigation of MAs is Opposition-Based Learning (OBL)65. The OBL algorithm is based on the concurrent calculation of objective values for the present individual and its inverse solution, in order to reveal a more advantageous optimal solution for the optimization objective. Nguyen et al.66 used the OBL mechanism into the Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) to circumvent the occurrence of local optima and enhance the optimization performance for achieving optimal solutions.

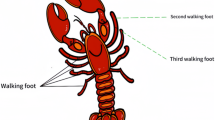

On the other hand, Lens opposition-based learning (LOBL) is a novel adaptation of OBL that replicates the process of convex lens imaging in optical principles. More precisely, if an item is positioned at a distance equal to twice the focal length of a convex lens, a true image that is both inverted and reduced in size will be formed on the opposite side of the lens. In Fig. 1, the point \(\:O\) represents the middle point of the search interval \(\:[lb,\:ub]\) in a two-dimensional space. The y-axis is visualized as a convex lens. The assumption is that when a person with a height of \(\:h\) is projected onto the x-axis in the image region, it is labeled as \(\:x\). This \(\:x\) point is located at a distance twice the focal distance away from the lens. Following the process of lens imaging, an actual image is formed with a height approximately equal to \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{h}\). The projection of this image on the x-axis is denoted as\(\:\:\stackrel{\sim}{x}\), indicated by the green point. By applying the fundamental principles of lens imaging, we can deduce the geometric equation as follows:

Let \(\:k=h/\stackrel{\sim}{h}\), then Eq. (21) is converted into:

When the value of k is equal to 1, Eq. (22) can be converted into the standard form of OBL in the following manner:

This implies that OBL is a specific example of LOBL, which not only possesses the benefits of OBL but also enhances solution variety and the probability of avoiding suboptimal solutions by adjusting the value of k. The extension of Eq. (23) to the D-dimensional space can be stated as follows:

The variable \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{x}}_{i,j}\) denotes the opposing solution of the i-th individual in the j-th dimension. \(\:l{b}_{j}\) and \(\:u{b}_{j}\) represent the upper and lower limits in the j-th dimension, respectively.

In the basic LOBL, the variable \(\:k\) is allocated a fixed value, which restricts its capacity to generate varied solutions during the iterations. The algorithm often prioritizes thorough exploration of the search space during the initial iterations in order to identify promising areas that contain optimal answers. Currently, increasing the value of \(\:k\) significantly can enhance the search breadth and population diversity. During the later stages, a reduced \(\:k\) value can be employed to improve the local search efficiency of the algorithm, resulting in a more accurate optimal solution. Thus, this paper suggests a nonlinear adaptive reduction mechanism for modifying the value of \(\:k\) resulting in adaptive variant of LOBL named Adaptive Lens Opposite-based Learning (ALBOL) in which the parameter \(\:k\) is defined in the following manner:

where \(\:t\) represents the current iteration and \(\:T\) represents the maximum number of iterations. Figure 2 illustrates the trajectory of the variable \(\:k\). After completing all algorithm operations, the proposed ALOBL mechanism is utilized to gradually modify the current optimal solution \(\:{X}_{B}\) dimension by dimension. This adjustment aims to bring the solution closer to the theoretical optimal solution and speed up the convergence process.

In other words, the strategy of ALOBL in AD-COA-L is applied only for the current best solution in the population, to avoid falling into the local optima strategically. The ALOBL generates an opposite solution to the current best solution by reflecting the best solution across the midpoint of the search space to create an alternative solution that explores another area of space that may lead to better optima. The application of ALOBL in this regard ensures that the algorithm does not disrupt the progress of the whole population, but indeed provides a critical exploration mechanism for the most promising candidate.

In addition, the ALOBL will be adaptive is the opposition strength, controlled by dynamically changing parameter \(\:k\). Because this value of the parameter is higher at early iterations, it maintains a higher diversity in the opposite solutions that enable broader exploration. Furthermore, \(\:k\) value fine-tunes the search to improve the exploitation around the best-found areas. When ALBOL applied to the best solution, AD-COA-L efficiently balances exploration and exploitation, leading to a better convergence behavior of this approach without the risk of premature stagnation in suboptimal regions. This strategy enhances the ability of the algorithm to pass through a complex search space and accelerates its convergence with maintained diversity in solutions.

Local escaping Operator (LEO)

The Local Escaping Operator (LEO) is an additional local search algorithm introduced in28. Its main purpose is to enhance the exploration capabilities of the Gradient-based Optimizer by facilitating the exploration of new regions, especially in complex real-world problems. This leads to an improvement in the overall quality of the solution. LEO updates the positions of solutions based on specific criteria, effectively preventing the optimization algorithm from being trapped in local optima and improving its convergence behavior. To generate alternative solutions with superior performance, LEO utilizes critical solutions, including the best position \(\:{X}_{B}\), two randomly generated solutions \(\:{X}_{r1}\) and \(\:{X}_{r2}\), two randomly chosen solutions \(\:X{1}_{i}\) and \(\:X{2}_{i}\), and a newly generated random solution \(\:{X}_{z}\). The following scheme provides a mathematical formula for determining the value of \(\:{X}_{LEO}\):

if rand < pr then

if rand < 0.5 then.

else.

end if.

end if (26)

The given equations have several parameters including \(\:f1\) which is a stochastic variable that can assume any value between − 1 and 1 inclusively, \(\:f2\) is a random variable that follows a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Furthermore, \(\:{\rho\:}_{1}\) indicates the probability and there are three additional random variables, specifically (\(\:{u}_{1}\), \(\:{u}_{2}\), and \(\:{u}_{3}\)) which are defined as follows:

where \(\:rand\) represents a randomly generated number that falls within the range of 0 to 1. On the other hand, the variable \(\:\mu\:\) represents a number that also falls within the range of 0 to 1. The provided equations can be simplified as shown in Eqs. (30–32):

The binary parameter, \(\:{Q}_{1}\), can only have a value of either 0 or 1. This value is determined by a condition: if \(\:{Q}_{1}\) is less than 0.5, then \(\:{Q}_{1}\) is set to 1. Alternatively, it is given a value of 0. In addition, to maintain a proper equilibrium between exploration and exploitation in search processes, the variable \(\:{\rho\:}_{1}\) is introduced which is defined by Eqs. (33–35):

where the values of \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\:\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\)are fixed at 0.2 and 1.2, respectively. The variable denotes the present iteration, while \(\:T\) signifies the maximum number of iterations. In order to maintain an equilibrium between exploration and exploitation, the parameter \(\:{\rho\:}_{1}\) automatically adapts itself according to the sine function \(\:\alpha\:\). The parameters \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\) influence the adaptation of the probability factor \(\:\rho\:1\) inside the strategy of LEO. These modulate the function \(\:\alpha\:\) of the sine that applies the perturburbation step to the solutions. The smaller value of \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\), in the initial iterations, promotes wider exploration. A higher value of \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\) during the ending iterations gives smaller, finer perturbations, shifting the focus toward exploitation. The adaptive mechanism provides an effective balance between exploration and exploitation, improves the convergence, and gives more accurate solutions using the AD-COA-L algorithm. It is proposed to calculate the solution, \(\:{X}_{z}\), in the prior scheme by following the indicated strategy in Eqs. (36) and (37):

where \(\:{X}_{rand}\) denotes a fresh generated solution, while \(\:{X}_{p}\) refers to a solution that has been chosen randomly from a population. Additionally, \(\:\mu\:\) represents a random number that falls within the range of values between 0 and 1. Equation (37) can be simplified in the following manner:

Here, the parameter \(\:{Q}_{2}\) is a binary variable that can only take the values of 0 or 1. Its value is decided by whether the variable \(\:\mu\:\) is smaller than 0.5 or not. The stochastic selection of parameter values \(\:{u}_{1}\), \(\:{u}_{2}\), and \(\:{u}_{3}\) enhances population variety and aids in avoiding local optimal solutions.

COA may struggle to achieve optimal performance as a result of insufficient information sharing among individuals. Relying solely on the dominant solution for guidance is a type of greedy search, which increases the likelihood of becoming trapped in local minima. To effectively discourage the deployment of isolated solutions and encourage the exchange of information in the search area, it is imperative for all participating parties to maintain communication via harnessing collective intelligence. In order to address this problem, the AD-COA-L algorithm utilizes the LEO operator at the end of each iteration to enhance the exploitation and search capabilities of COA. Additionally, the LEO strategy provides a controlled perturbations to the solutions’ positions by stochastic variables and probability factors. This leads to easily escaping local minima, encouraging the algorithm to explore parts of the search space not analyzed before. This could render LEO particularly effective during later iterations when the algorithm can refine the search with a maintained diversity in the population. Enriching its general convergence speed and solution accuracy to enable the algorithm to plunge even into global optima for highly complex optimization problems, AD-COA-L is applied with LEO at the end of every iteration.

Consequently, the new AD-COA-L allows the population to discard inefficient options and perform the local search process more efficiently. The main steps and operators of the proposed AD-COA-L is depicted in Algorithm 1 and Fig. 3.

Algorithm 1: AD-COA-L algorithm | |

|---|---|

Input: Maximum number of iterations \(\:T\), Population size \(\:N\). Output: Optimal solution \(\:{X}_{B}\), fitness value of optimal solution \(\:{f}_{B}\) | |

1. | Initialize the initial population \(\:X\) using Eq. (16) |

2. | Compute the fitness value \(\:f\left({X}_{i}\right)\) of each solution |

3. | Obtain the required solutions \(\:{X}_{B}\) and \(\:{X}_{L}\:\) |

4. | for\(\:t\le\:\text{T}\)do |

5. | Calculate the temperature \(\:temp\) using Eq. (2) |

6. | Calculate \(\:{C}_{2}\) using Eq. (6) |

7. | Calculate \(\:{X}_{S}\) using Eq. (4) |

8. | Apply ALOBL strategy to the best solution using Eq. (24) |

9. | \(\:\mathbf{f}\mathbf{o}\mathbf{r}\:i=1\:\text{t}\text{o}\:N\:\mathbf{d}\mathbf{o}\) |

10. | if\(\:temp\)\(\:>30\)then |

11. | if\(\:rand<0.5\)then |

12. | Update position of crayfish using Eq. (5) |

13. | Else |

14. | Update position of crayfish using Eq. (18) |

15. | end if |

16. | else |

17. | Define the food intake \(\:p\) and size \(\:Q\) using Eq. (3) and Eq. (10) |

18. | if\(\:p>2\)then |

19. | Update the position of crayfish using Eq. (19) |

20. | else |

21. | Update position of crayfish using Eq. (20) |

22. | end if |

23. | end if |

24. | end for |

25. | Check the boundary conditions |

26. | Apply greedy selection using Eq. (14) |

27. | \(\:\mathbf{f}\mathbf{o}\mathbf{r}\:i=1\:\text{t}\text{o}\:N\:\mathbf{d}\mathbf{o}\) |

28. | Apply LEO operator using Eqs. (26–38) |

29. | Check boundary limits |

30. | Apply greedy selection using Eq. (14) |

31. | end for |

32. | Update the current optimal solution \(\:{X}_{B}\) and its fitness value \(\:{f}_{B}\). |

33. | \(\:t=t+1\) |

34. | end for |

35. | Return\(\:{X}_{B}\) and its fitness value \(\:{f}_{B}\); |

Experimental results and analysis

This study evaluates the effectiveness of the AD-COA-L algorithm by comparing it against eleven conventional and recent algorithms, as well as eight state-of-the-art similar algorithms that are recognized for their exceptional performance. A total of 29 benchmark functions from CEC2017 67 were tested. The comparison includes six conventional algorithms: Particle Swarm Optimizer (PSO)38, Sine-Cosine Algorithm (SCA)30, Slime Mould Optimizer (SMA)39, Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA)27, Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA)68, and Harris Hawk Algorithm (HHO)41. Additionally, it incorporates five recent algorithms: White Shark Optimizer (WSO)69, Gradient Based Optimizer (GBO)28, Spider Wasp Optimizer (SWO)42, Weighted Mean of Vectors (INFO)29, and the original COA. The specifications for the comparison methods’ parameters can be found in Table 2. In order to achieve fairness, every algorithm is given a consistent maximum iteration limit of 1000 and an initial population size of 30. To minimize variability, every algorithm is run 30 times for each test function, and the standard deviation (STD) and average (AVG) of the results are recorded.

The trials are conducted on a system including an Intel(R) i7-10750 H CPU, 32 GB of RAM, and running Microsoft Windows 10. Furthermore, MATLAB (R2020a) functions as the programming environment for coding, ensuring dependability and computational power throughout experimentation. The rows in the Tables indicate the ranking of the average values. A rank of 1 signifies that the algorithm achieved the lowest average solution value out of 30 trials, indicating a higher search capability.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

Two main parameters affect the performance of AD-COA-L including the probability \(\:p\) and the LEO limit parameters βmin and βmax. Therefore, in this section an experiment is conducted to test the sensitivity analysis of these parameters. First, we perform the sensitivity analysis of the AD-COA-L algorithm with respect to the probability parameter \(\:p\), that controls the size of position updates in both competitive and foraging phases. To this end, we conducted experiments over 29 benchmark functions of CEC 2017 suite with nine different values of p within the interval [0.1, 0.9] with a step size of 0.1. Table 3 reports the STD and AVG of different variations of parameter \(\:p\). In all functions, the results include the computation of the average fitness AVG and STD over multiple runs and present the results for each value of \(\:p\). Further, performance across all functions has been ranked based on the Friedman rank test where lower ranks correspond to a better overall performance. The well marked variation of performance when the value of \(\:p\) changes are reported. For instance, for lower values of \(\:p\), such as 0.1 and 0.2, the algorithm tends to explore more widely, which indicates that with larger steps, while the exploration capability of the algorithm is wider in the search space, convergence towards the optimal solution is less precise.

Because \(\:p\) increases to 0.3 and 0.4, the drastic improvement of the algorithm’s performance is evident. In particular, when \(\:p\) = 0.4, the lowest AVG values for many benchmark functions compared to other variations are obtained by the algorithm, where the STD values of most benchmark functions depict steady convergence behavior. The fact that \(\:p\)=0.4 presents the best performance is further corroborated by the Friedman rank, reaching the minimum average rank there, which maintains an effective balance between exploration and exploitation. This lets the algorithm efficiently explore the search space and fine-tune solutions in later iterations.

Beyond \(\:p\) = 0.4, the performance of the algorithm starts to degrade slightly, which could also be seen from increased AVG and STD values when \(\:p\) = 0.5 and beyond. That is indicative of the fact that the higher values of \(\:p\) shift the algorithm to a more conservative strategy of search in favour of exploitation at the expense of global exploration. Thus, the algorithm is then prone to local optima, particularly on multimodal functions, which call for a broader search.

This sensitivity analysis introduces that the selection of probability parameter \(\:p\) significantly influences the performances of the AD-COA-L algorithm. In this work, the optimal value identified is \(\:p\)=0.4, since the optimal trade-off between exploration and exploitation occurs for the algorithm, with superior performance evident over most of the CEC2017 benchmark functions. Therefore, in applications of the AD-COA-L algorithm, the utilization of \(\:p\)=0.4 will be taken into consideration to ensure robustness in the performances of optimization.

Together with the sensitivity analysis of the probability parameter \(\:p\), an experiment also will be carried out that analyzes the impact of the parameters \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\)d \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\). This would give which governs the adaptation of the probability factor \(\:\rho\:1\) within LEO strategy. Six different combinations of \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\)re evaluated, described in detail in Table 4.

Additionally, Table 5 captures the STD and AVG values of different combinations for the parameters \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\). The sensitivity analysis has shown that the algorithm’s performance significantly depends on the choice of \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\). Among the six scenarios, the best performance of the algorithm is obtained for Scenario 3, since this scenario has minimum AVG and STD values for many of the CEC 2017 benchmark functions compared to other scenarios. It finds reflection in its Friedman rank of 1.87, thereby confirming that it has the best balance between exploration and exploitation, which has translated into better convergence behavior.

In contrast, the AVG and STD values were higher for Scenario 1 since the smaller range of \(\:\beta\:\) resulted in limited exploration. The Friedman rank achieved for this scenario is 4.62, indicating relatively poor performance. Similar behavior was obtained for Scenario 4 with a Friedman rank of 4.28, since the increase of βmin to 0.3 yielded poor exploration capabilities of the algorithm in the search space.

Scenario 2 and Scenario 5 provided a moderate performance, ranking Friedman at 3.43 and 3.15, respectively. While they turned out better than the results for Scenario 1, their balance between exploration and exploitation was still far from being as ideal as in Scenario 3. In Scenario 6, the wider range allowed the Friedman rank to become as low as 2.65 due to effective exploration and exploitation of \(\:\beta\:\), though less well-balanced compared to the Scenario 3 configuration.

The Friedman rank test categorizes Scenario 3 as the best among all parameter combinations tested. Therefore, the sensitivity analysis conducted within the study revealed that the choices of \(\:{\beta\:}_{min}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{max}\) are crucial for the performance delivered by AD-COA-L. The best performing variants were, in fact, obtained by the setting introduced in Scenario 3 with Friedman rank of 1.87 reached a good balance between exploration and exploitation, resulting in enhanced optimization performance of the benchmark functions.

CEC2017 results analysis

The CEC2017 benchmark suite consists of 29 benchmark test functions, each specifically tailored to fulfill certain objectives within its class. F1 and F3 are functions that have a single peak, making optimization straightforward. Functions F4 to F10 exhibit several modes with numerous peaks and valleys. Functions F11 to F20 are composite, incorporating a variety of landscapes, which adds complexity to the optimization problem. Functions F21 to F30 are composed of multiple sub-components, which collectively produce intricate optimization landscapes. The experimental validity of F2 has been compromised by uncontrollable factors, rendering it unsuitable for experimentation. Therefore, we refrained from doing tests on F2. The next part presents a comprehensive analysis of the test findings derived from the experiments conducted on these functions.

CEC2017 statistical performance

Tables 6 and 7 present the empirical results for the situations with sizes of 50 and 100. Tables 6 and 7 depict the mean, ranking, and standard deviation of objective function values for each algorithm. The AD-COA-L algorithm has demonstrated outstanding performance in locating the global optimum, particularly in experiments involving the single-peaked issue F1.

During the trials conducted in a 50-dimensional space, AD-COA-L initially demonstrates a minor advantage over INFO in terms of F1 performance. Nevertheless, it quickly exceeds the original state and progresses towards the optimal solution. Nevertheless, in the case of trials done in a 100-dimensional space, AD-COA-L continuously surpassed INFO in terms of performance on the F1 function, retaining a persistent advantage throughout. The INFO algorithm demonstrated the highest average value in problems with a dimension of 50 in the example of F3. Nevertheless, AD-COA-L exhibited superior performance compared to all other algorithms when applied to the tested functions in a 100-dimensional space. The expanded power of AD-COA-L to discover and converge towards the most optimal solutions for problems with a single highest point is proven, confirming its robust potential to both explore and exploit global optima.

AD-COA-L exhibits superior performance in the majority of functions for multimodal problems F4-F10 when compared to the other eleven comparison algorithms. When comparing the AD-COA-L algorithm to the INFO, PSO, and WSO algorithms, it becomes apparent that the AD-COA-L approach demonstrates a slower convergence and achieves inferior results in the 50-dimensional trials. However, it shows a comparatively lower level of performance on function F6. Within the function F7, the efficiency of the INFO and PSO methods surpasses that of AD-COA-L. Nevertheless, the disparity between AD-COA-L and these algorithms is minimal, indicating that AD-COA-L exhibits commendable performance in F7. However, AD-COA-L has lower performance than INFO on functions F5, F6, and F8. Nevertheless, AD-COA-L demonstrates exceptional performance in the remaining functions, proving its supremacy and resilience in effectively resolving complex challenges. AD-COA-L demonstrates excellent competence in effectively managing a diverse variety of mixed functions, ranging from F11 to F20. When tested in a 50-dimensional configuration, the performance of AD-COA-L is similar to that of INFO on F11, but slightly worse on F12, F14, and F18. However, the standard deviation of AD-COA-L at F18 exceeds that of INFO, suggesting that AD-COA-L demonstrates more stability in this function. AD-COA-L outperforms other algorithms in most functions when considering 100 dimensions, except for F12 and F13, which are effectively handled by INFO. Significantly, there is a slight discrepancy in the performance of AD-COA-L and INFO at F12 and F13, with AD-COA-L exhibiting superior stability compared to INFO at F12. The outstanding success of AD-COA-L can be credited to its wide array of solution search strategies, namely its immensely powerful global search capabilities, which is remarkably effective in addressing intricate problems.

AD-COA-L is capable of effectively resolving complex problems, namely those related to functions F21-F30. In a study involving 50 dimensions, the AD-COA-L algorithm has outstanding performance, outperforming all others except for F21, F27, and F30, which have higher rankings. AD-COA-L demonstrates superior performance compared to all other algorithms across all functions, with the exception of the INFO function in F26, F29, and F30, while testing with 100-dimensional data. The results clearly demonstrate that AD-COA-L is exceptional and highly versatile in efficiently addressing a wide range of challenges. It enables a thorough examination and enhancement of intricate search domains.

CEC2017 convergence analysis

Figures 4 and 5 depict the convergence rate and accuracy of the AD-COA-L, SWO, COA, SO, AOA, HHO, INFO, PSO, SMA, SCA, and GBO algorithms in comparison to CEC2017 for the dimensions D = 50 and D = 100. The data demonstrates that AD-COA-L has a higher rate of convergence, reduced variability, and greater stability when compared to the other algorithms. Hence, AD-COA-L possesses the capacity to quickly attain the most favorable answers, thereby improving problem-solving effectiveness and adaptability. AD-COA-L consistently exhibits improved convergence on the convergence curve in the majority of test cases. This suggests that its search capacity gradually improves with each repetition, allowing it to effectively locate the best solutions for optimization problems. When applied to unimodal functions F1 and F3, the AD-COA-L algorithm has a higher convergence rate compared to other techniques. While INFO may outperform AD-COA-L in the early iterations, AD-COA-L ultimately gets higher results due to its new Bernoulli approach for population initialization. AD-COA-L demonstrates a higher rate of convergence in comparison to all alternative approaches. Function F5 provides evidence that AD-COA-L consistently obtains the lowest fitness values before the 300th iteration, surpassing all other algorithms in performance. Therefore, it can be deduced that AD-COA-L demonstrates a swift convergence rate, most likely because of its innovative exploitation technique and improved exploration formula. This enhances the algorithm’s ability to both explore and exploit. Once again, when assessing the performance of function F7 at CEC2017 with a dimensionality of 50, AD-COA-L demonstrates superior performance compared to all other rivals. This is attributed to its faster convergence rate and the attainment of the lowest value. Nevertheless, when evaluating F7 with D = 100, PSO exhibits remarkable performance. However, the difference in convergence rate between AD-COA-L and PSO is negligible. Thus, we can infer that the performance of AD-COA-L is praiseworthy.

Comparison of AD-COA-L with advanced algorithms

This experiment is undertaken to further evaluate the performance of AD-COA-L in comparison to high-performing algorithms. Eight sophisticated and high-performing algorithms are employed to thoroughly assess the accuracy and effectiveness of AD-COA-L. The algorithms can be categorized into two groups. The first group consists of five advanced optimization algorithms: CSOAOA48, CJADE70, RLTLBO71, ASMA72, and TLABC73, and the second group constitute three winning algorithms in IEEE CEC, which are proven to perform excellently, namely, CMAES74, IMODE75, and AGSK76. These algorithms have been demonstrated to perform exceptionally well. The table labeled Table 8 contains the statistical standard deviation and mean of fitness values. These data were acquired from 30 independent runs using twenty-nine benchmark functions from CEC2017. The dimensionality of these functions is 50.

The analysis reveals that the AD-COA-L algorithm achieves the lowest average fitness value in 17 out of 29 functions, surpassing all other algorithms. The AD-COA-L algorithm has the greatest number of superior functions compared to all other algorithms. For instance, AD-COA-L demonstrates outstanding performance in unimodal functions F1 and F3, indicating superior values for both standard deviation and mean of fitness. The IMODE algorithm reports the optimal STD values in F4, while the AD-COA-L function guarantees the highest average fitness values.

However, the original COA approach does not demonstrate exceptional performance in any function. The suggested modifications in AD-COA-L enhance the balance between exploration and exploitation, resulting in the highest quality overall solution in terms of the ideal global optima. According to the findings in Table 8, the AD-COA-L algorithm shows great potential in the field of optimization. It outperforms algorithms that are very proficient in the field by being capable of solving global optimization tasks. The last row in Table 8; Fig. 6 represents the Friedman rank between the comparative algorithms where AD-COA-L is ranked the first with 2.71 while IMODE is the second with rank of 2.92 indicating the superior performance of AD-COA-L compared to a set of advanced and champion algorithms.

Statistical analysis of AD-COA-L

The Wilcoxon rank sum test77 can be employed as a nonparametric statistical test to assess if the comparative AD-COA-L approach is statistically distinct from the other methods. The objective was achieved by doing 30 individual runs for each of the competing algorithms, utilizing a standardized set of 29 test functions. The Wilcoxon rank sum test is performed at a significance level of 0.05 to assess the significant difference between the solution results of the six algorithms being studied and those of the AD-COA-L algorithm. The statistical test results are aggregated and presented in Tables 9 and 10. To confirm these findings, if the \(\:p\)-value is less than 0.05, we can reject the null hypothesis and conclude that there is a significant difference between the algorithms being studied. Alternatively, if the \(\:p\)-value is greater than 0.05, the search results obtained from the two methods are compared. Tables 9 and 10 clearly demonstrate that the AD-COA-L algorithm exhibits substantial disparities when compared to the other approaches. AD-COA-L exhibits significant superiority when compared to WOA, SWO, WSO, HHO, PSO, COA, INFO, AOA, SMA, SCA, and GBO. The statistical significance of the advantage of the AD-COA-L algorithm has been determined.

Computational analysis

Computational analysis of different algorithms is a crucial factor that needs to be studies to assess the overall performance of the novel proposed algorithms. The computational analysis includes two main folds which are the time complexity and space complexity. The time complexity studies the theoretical computational runtime of different algorithms according to the most significant operations while the space complexity denotes the memory space required by the main variables and vectors of algorithms. This section studies the compactional analysis of the proposed AD-COA-l compared to the original COA and other compared algorithms.

Time complexity

There are three key parameters that directly influence the time complexity of the original COA including population size (\(\:N\)), dimensionality (\(\:D\)), and the number of iterations (\(\:T\)). COA generates an initial population in the initialization stage, and the main computational cost occurs in the updating of positions in the stages of summer resort, competition, and foraging. This updating process is done for each solution in the population and this whole process is repeated for all iterations. So, for original COA time complexity can be represented as:

On the other hand, the general time complexity of the proposed AD-COA-L algorithm is similar to that of the original COA, with several enhancements added to it. Namely, Bernoulli Map-based Population Initialization, Adaptive Lens Opposite-Based Learning (ALOBL), and the Local Escaping Operator (LEO). In the Bernoulli map-based population initialization, the complexity remains \(\:O\left(ND\right)\), similar to the original initialization process. In the adaptive lens opposite-based learning (ALOBL), it applied only to the best solution, contributing \(\:O\left(TD\right)\) over the iterations. Furthermore, the local escaping operator (LEO) updates the positions of all solutions, contributing \(\:O\left(TND\right)\). The dynamic inertia weight coefficient does not add more complexity since it is part of the position update equation of the original COA. Therefore, the total time complexity of the AD-COA-L algorithm is bound by:

\(\:O\left(AD-COA-L\right)=\:O\left(ND\:+\:TND\right)=O\left(TND\right)\)It is apparent that from the time complexity of each the original COA and the improved AD-COA-L that there is no major difference between them in the time complexity consumed by the CPU, but the performance obtained by AD-COA-L is much better than COA as conducted in the experiments.

Space complexity

Regarding space complexity, the original COA and the proposed AD-COA-L have the same space complexity because both algorithms deal with a population of size \(\:N\) and a problem of dimensionality \(\:D\). The number of memory usage used at any instant of time during the run of the algorithm increases linearly with respect to the population size and the number of dimensions under optimization. Hence, the following ensures the space complexity for both algorithms:

Finally, Table 11 compare between the proposed AD-COA-L and its rivals regarding the time and space complexity obtained during different iterations. As shown by Table 11, the time complexity for all algorithms under comparison, including the proposed AD-COA-L algorithm, is \(\:O\left(TND\right)\). This means that, even with added strategies in AD-COA-L, such as Bernoulli map-based initialization, ALOBL, and LEO, the time complexity level is still within the same magnitude with other popular algorithms such as PSO, AOA, and WOA.

Additionally, in all algorithms, the space complexity is \(\:O\left(ND\right)\), which suggests that the proposed enhancements in AD-COA-L do not consume more of the memory resource than those used by the other compared algorithms and hence is competitive both in time and space efficiency.

This implies that the new AD-COA-L introduces some new strategies for the improvement of exploration and exploitation and retains the same computational complexity as other well-established algorithms. This underlines its efficiency since the improvement in optimization performance does not involve any increase in either time or space complexity. The AD-COA-L therefore provides a well-balanced compromise between performance and computational cost; hence, it should be considered seriously when trying to solve challenging global optimization problems.

Application of AD-COA-L to Engineering problems

This section assesses the practical performance of the proposed AD-COA-L by examining its efficacy in solving engineering optimization challenges. The problems encompass tension/compression string design, welded beam design, speed reducer design, tubular column design, piston lever design (PLD), and robot gripper. The research utilizes the static penalty method80 to address the limitations in the optimization problem:

where the parameter \(\:\zeta\:\left(z\right)\) represents the objective function, while \(\:{o}_{j}\) and \(\:{l}_{j}\) are two positive penalty constants. The functions \(\:{U}_{j}\left(z\right)\) and \(\:{T}_{i}\left(z\right)\) represent constraint conditions. The parameters \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) can take on values of either 1 or 2. The resolution of all engineering issues is achieved by employing the parameter configurations specified in Sect. 4.2. The population size, maximum iteration count, and number of independent runs are 50, 500, and 30, respectively.

Welded beam design

The welded beam structure is a pragmatic design problem frequently employed to assess different optimization techniques. The structure comprises of beam A and the welds that fasten it to member B, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The aim of this design is to determine the most efficient design factors that result in the lowest production costs81. The minimization method is constrained by limitations on shear stress (), bending stress in the beam (), buckling load on the bar (-), and the final deflection of the beam (). The optimization process includes four parameters: the length of the clamping bar (), the thickness of the weld (ℎ), the thickness of the bar (), and the height (). The model is presented in the following manner:

Consider

Objective function

Subject to

Where

Boundaries

When designing the welded beam, the AD-COA-L method was evaluated with other algorithms such as COA, GWO, HHO, RSA, GJO, jDE, WSO, WOA, PSO, and ASMA. Table 12 presents the minimum cost and the matching optimal variable values obtained by each approach. The welded beam design reached an ideal cost of 1.6702177263 using AD-COA-L.

Piston lever design (PLD)

The aim of PLD is to decrease the amount of oil while the piston lever moves from 0° to 45°82. The optimization outcomes are influenced by the relative distances \(\:H\), \(\:B\), \(\:D\), and \(\:V\) between the piston components. Figure 8 depicts the schematic representation of PLD, and the related mathematical model is defined as follows:

Consider

Objective function

Subject to

Where

Boundaries

Table 13 unequivocally shows that the cost of AD-COA-L is significantly lower than that of the comparative approaches. It is important to note that only PSO and SMA fail to accurately identify the optimal design method for PLD. This suggests that while most algorithms have adequate convergence accuracy, they lack the durability seen by AD-COA-L. The AD-COA-L algorithm attains an optimal fitness value of 8.411227.

Three-bar truss design

The objective of this task is to determine the construction with the lowest weight required for constructing a three-bar truss. This problem consists of two distinct parameters that need to be optimized while considering other restrictions. The mathematical model and the necessary constraint for the parameters are specified as shown:

Consider:

Minimize:

Subject to:

Where

The comparative outcomes for AD-COA-L and other relevant algorithms for the Three-bar truss problem are displayed in Table 14. Table 14 shows that AD-COA-L achieved the lowest weight when designing the Three-bar truss with optimized 1 and 2. Several other algorithms, such as GWO and HHO had favorable outcomes. However, AD-COA-L surpasses them in performance. The statistical metrics pertaining to this problem are displayed in Table 14. The AD-COA-L algorithm achieved favorable statistical outcomes when compared to all other algorithms.

Speed reducer design

The design illustrated in Fig. 9 presents a complex optimization problem with the objective of decreasing the weight of the speed reducer83. This design issue encompasses 7 variables and is subject to 11 constraints. The variables consist of the teeth module (), face width (), length of the first shaft between bearings (-1), number of teeth on the pinion (), diameter of the first shaft (-1), length of the second shaft between bearings (-2), and diameter of the second shaft (-2). The objective function for this model is specified as follows:

Consider

Objective function

Subject to

Boundaries

The Speed Reducer problem design involved evaluating the performance of AD-COA-L approach in comparison to various other algorithms, namely COA, GWO, HHO, RSA, GJO, jDE, WSO, WOA, PSO, and ASMA. Table 15 displays the lowest cost and the related ideal variable values achieved by each algorithm. AD-COA-L achieved an optimal cost of 2675.413081664 for the design of the Speed Reducer problem.

The tension–compression spring design problem

The goal of the tension/compression spring design is to minimize the spring’s weight while meeting three specific limitations, as shown in Fig. 1084. This optimization involves three key variables: the wire diameter \(\:d\left({x}_{1}\right)\), the mean coil diameter ( \(\:D\left({x}_{2}\right)\), and the number of active coils \(\:N\left({x}_{3}\right)\). These variables need to be optimized as follows:

Consider

Objective function

Subject to

Boundaries

AD-COA-L was evaluated alongside COA, GWO, HHO, RSA, GJO, jDE, WSO, WOA, PSO, and ASMA algorithms. Table 16 displays the lowest cost and the related optimal variable values attained by each approach. AD-COA-L earned the lowest spring weight of 0.01266352 in the tension/compression spring design task.

Tubular column design problem

The challenge of tubular column design is centered around the creation of columns that are uniform in shape and capable of withstanding compression stresses of magnitude \(\:P\), while simultaneously minimizing cost85. The design variables consist of the average diameter \(\:{t}_{1}\) of the column and the thickness \(\:{t}_{2}\) of the tube. The column is 250 cm long, has a modulus of elasticity of \(\:0.85\:\times\:\:{10}^{6}\)\(\:kgf/c{m}^{2}\), and a yield stress of 500 \(\:kgf/c{m}^{2}\). Figure 11 depicts a homogeneous tubular column structure together with its cross-section. The design model can be characterized as follows:

Consider

Objective function

Subject to

Boundaries

AD-COA-L has been utilized to resolve problems related to tubular column design. The least cost and corresponding variables produced from the AD-COA-L scheme are compared with those acquired from other algorithms, as shown in Table 17. The data shown in Table 17 demonstrates that the AD-COA-L solution attains the most economical cost. This demonstrates that AD-COA-L has the capability to offer superior quality and more consistent solutions for this challenge, hence highlighting the exceptional performance of AD-COA-L.

Robot gripper (RG)

RG stands for a complex optimization problem in the field of mechanical structural engineering that deals with restrictions. The primary goal is to reduce the discrepancy between the maximum and minimum forces exerted by a fixture11. The optimization outcomes are impacted by six variables: the dimensions of the chain rods, the angular orientation of the chain rods, the vertical and horizontal distances, the clamping pressure, and the placement of the actuator in the robotic gripper. This problem involves seven decision variables: the vertical distance between the first and third link nodes (-1), the lengths of three chain rods (-) for =1,2,3, the horizontal distance between the actuator’s end and the third link node (ℎ), the vertical distance between the first link node and the actuator’s end (-2), and the angle between the second and third chain rods (). The objective function for RG integrates two antagonistic optimization functions. In order to address the issue of prolonged computation times during the iterative process of identifying the optimal value. Figure 12 illustrates the schematic depiction of RG, whereas the actual mathematical model is described as follows:

Consider

Objective function

Subject to

Where

Boundaries

Table 18 unambiguously demonstrates that the optimal cost of AD-COA-L is significantly lower than that of the other comparison methods. It is crucial to note that only ASMA did not achieve low optimal values compared to the other algorithms. This suggests that while most algorithms may have enough convergence accuracy, they lack the durability seen by AD-COA-L. The AD-COA-L algorithm achieved an ideal fitness value of 2.525423.

Conclusion and future directions